Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Definition of Windbreaks and Their Importance in Climate Change Era

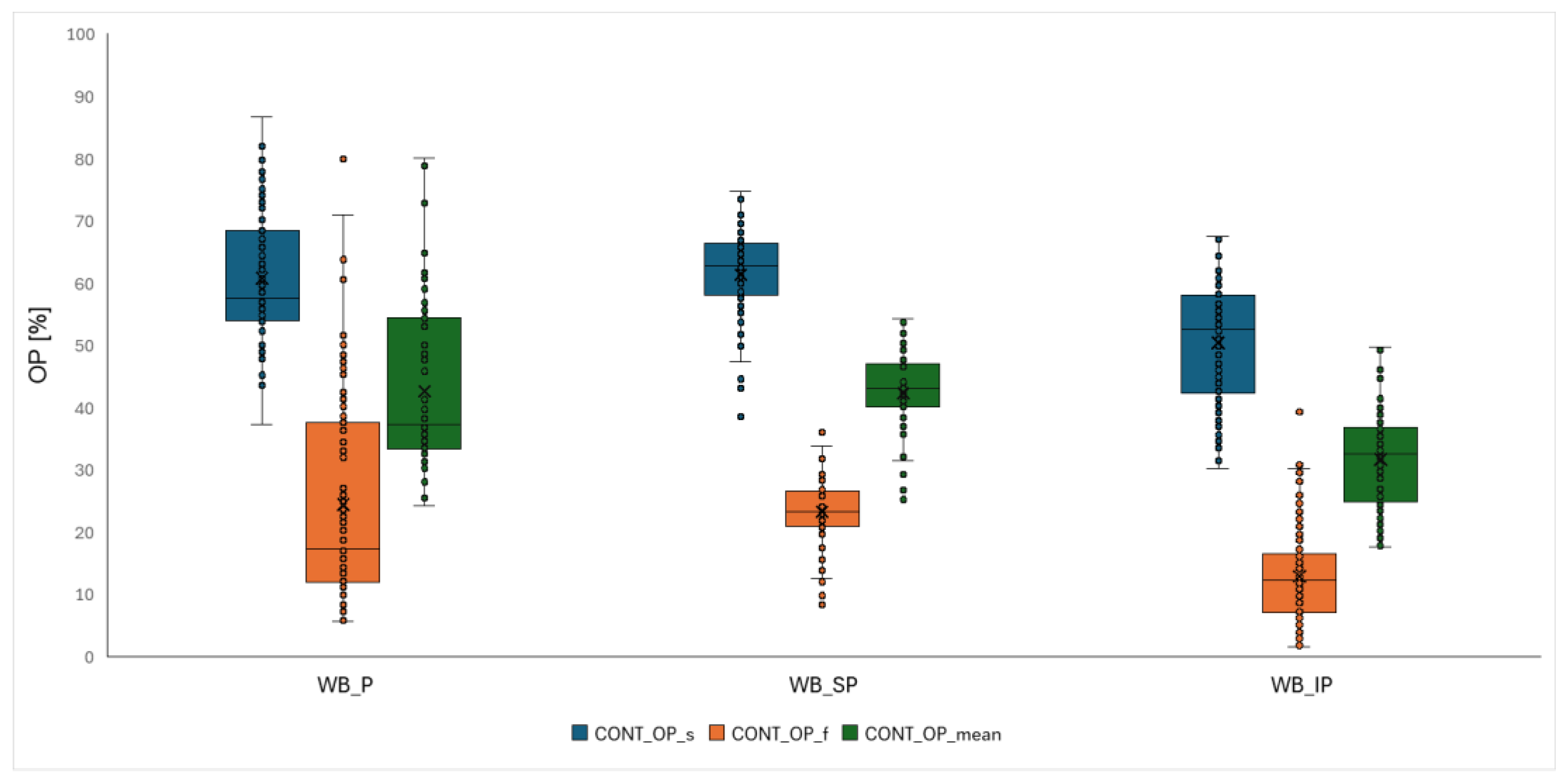

Windbreak Structure and Optical Porosity

Methodological Advances in Windbreak Assessment

Research Gaps and Aim of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

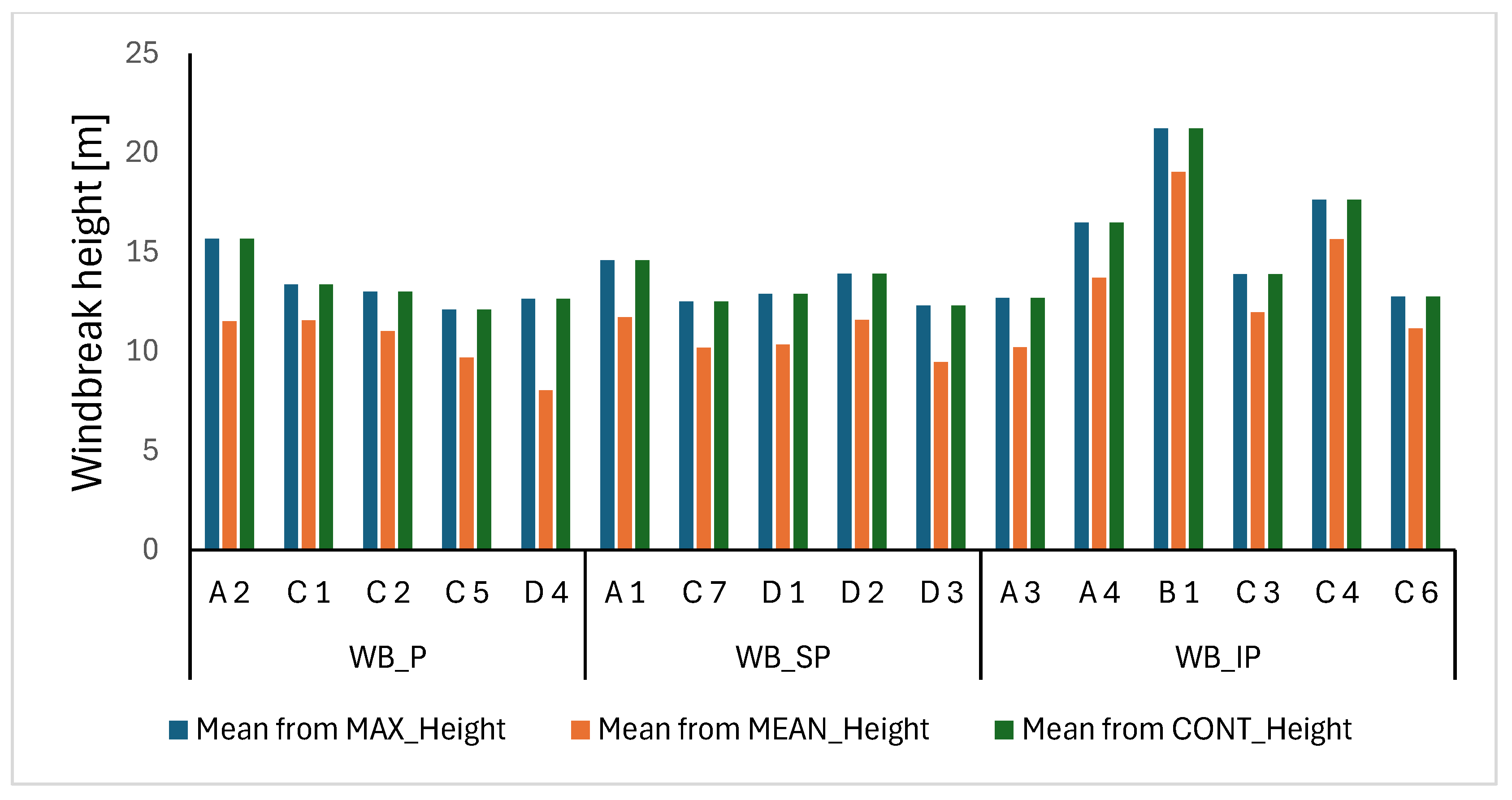

Model windbreaks

- Location A (GPS: 48.8135347N, 16.7514300E): A1 to A4

- Location B (GPS: 48.8322958N, 16.5939950E): B1

- Location C (GPS: 48.7647197N, 16.1589622E): C1 to C7

- Location D (GPS: 48.8500761N, 16.1760425E): D1 to D4

Evaluation of OP from Digital Images

3. Results and discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tyndall, J. & Colletti, J. Mitigating swine odor with strategically designed shelterbelt. systems: a review, Agroforest Syst. 2007, 69:45-65. [CrossRef]

- Brandle, J.R., Hodges, L., Tyndall, J. & Sudmeyer, R.A. Windbreak practices. In: Garrett, H.E. (ed.). North American Agroforestry, an integrated science and practice. 2009, pp. 75-104. 2nd edition. Madison: American Society of Agronomy.

- Follet, R., Mooney, S., Morgan, J., Paustian, K., Allen, L.H., Archibelgue, S., Baker, J.M., Del Grosso, S.J., Derner, J., Dijkstra, F.; Franzlubbers, A.J.; Jansen, H., Kurkalova, L.A., McCarl., Ogle, S., Parton, W.J., Rice, C.W., Roberston, G.P., Schoenenberger, M., West, T.O. & Williams, J. Carbon sequestration and green-house gas fluxes in agriculture: Challenges and opportunities. 2011, First edition. Ames, Iowa, USA: Council for Agricultural Science and Technology- CAST-. 106 p.

- Schoeneberger, M.M. Agroforestry: working trees for sequestering carbon on agricultural lands. Agroforest Syst. 2009, 75:27-37. [CrossRef]

- Possú, W.B., Brandle, J.R., & Ordóñez, H.R. Carbon storage potential of windbreaks in the United States. Revista de Ciencias Agrícolas. 2019, 36(E), 108-123.

- Chendev, Y.G., Novykh, L.L., Sauer, T.J., Petin, A.N., Zazdravnykh, E.A., & Burras, C.L. Evolution of Soil Carbon Storage and Morphometric Properties of Afforested Soils in the U.S. Great Plains. Soil Carbon 2014, 475-482.

- Hernández-Morcillo, M., Burgess, P., Mirck, J., Pantera, A., Plieninger, T. Scanning agroforestry-based solutions for climate change mitigation and adaptation in Europe. Environmental Science and Policy. 2018, 80: 44–52.

- Abbas, F. , Hammad, H. M., Fahad, S. et al. Agroforestry: a sustainable environmental practice for carbon sequestration under the climate change scenarios - a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017, 24, 11177–11191. [Google Scholar]

- Campi, P., Palumbo, A.D., Mastrorilli, M. Effects of tree windbreak on microclimate and wheat productivity in a Mediterranean environment. European Journal of Agronomy. 2009, 30: 220–227.

- Kanzler, M., Böhm, C., Mirck, J., Schmitt, D., Veste, M. Microclimate effects on evapotranspiration and winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) yield within a temperate agroforestry system. Agroforestry Systems. 2019, 93: 1821–1841.

- Veste, M., Littmann, T., Kunnecke, A., du Toit, B., Seifert, T. Windbreaks as part of climate-smart landscapes reduce evapotranspiration in vineyards, Western Cape Province, South Africa. Plant Soil Environ. 2020, 66: 119–127.

- Středa, T.; Středová, H.; Rožnovský, J. Orchards microclimatic specifics. In Bioclimate: Source and Limit of Social Development, Topolčianky, Slovakia; Slovak University of Agriculture: Nitra, Slovakia, 2011; pp. 132–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock, J.W. Aerodynamic studies of shelterbelts in New Zealand-1: low to medium height shelterbelts in Mid-Canterbury. New Zealand J Sci. 1969, 12: 754–776.

- Zhang, H., Brandle, J.R., Meyer, G.E. and Hodges, L. The relationship between open windspeed and windspeed reduction in shelter. Agrofor Syst. 1995, 32: 297–311.

- Yang XG, Yu, Y. Estimating soil salinity under various moisture conditions: an experimental study. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2017, 55:2525–2533.

- Bitog JP et al. Numerical simulation study of a tree windbreak. Biosyst Eng. 2012, 111:40–48.

- Jiang, F., Zhou, X., Fu, M., Zhu, J., Lin, H. Shelterbelt porosity model and its application. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 1994, 5, pp. 251-255.

- Nosek, S. , Kellnerova, R. , Jurcakova, K., Janour, Z., Chaloupecka, H., Jakubcova, M. Effect of shelter porosity on downwind flow characteristics. EPJ Web of Conferences. 2016, 114, p 02084. [Google Scholar]

- Streda, T. , Malenova, P. ; Pokladnikova, H.; Roznovsky, J. The efficiency of windbreak on the basis of wind field and optical porosity measurement. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis. 2008, 56, pp. 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler, A.E. , Gordon, A. M. & Gillespie, T.J. Optical porosity and windspeed reduction by coniferous windbreaks in Southern Ontario. Agroforest Syst. 1992, 17, 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Stredova, H.; Podhrazska, J.; Litschmann, T.; Streda, T. Roznovsky. J. Aerodynamic parameters of windbreak based on its optical porosity. Contrib. Geophys. Geod. 2012, 42, pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lukasová, V. , Vido, J. , Škvareninová, J., Bičárová, S., Hlavatá, H., Borsányi, P., Škvarenina, J. Autumn phenological response of European beech to summer drought and heat. Water. 2020, 12, 2610. [Google Scholar]

- Mrekaj, I., Lukasová, V., Rozkošný, J., Onderka, M. Significant phenological response of forest tree species to climate change in the Western Carpathians. Central European Forestry Journal. 2024, 70: 107-121. [CrossRef]

- Středová, H. , Fukalová, P. , Chuchma, F., Středa, T. A Complex Method for Estimation of Multiple Abiotic Hazards in Forest Ecosystems. Water. 2020, 12, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacek, Z. , Řeháček, D. , Cukor, J. et al. Windbreak Efficiency in Agricultural Landscape of the Central Europe: Multiple Approaches to Wind Erosion Control. Environmental Management. 2018, 62, 942–954. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. , Li, F. , Fan, W. et al. Evaluating the efficiency of wind protection by windbreaks based on remote sensing and geographic information systems. Agroforest Syst. 2021, 95, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.M., Pedziwiatr, K., & Bogawski, P. Hidden gaps under the canopy: LiDAR-based detection and quantification of porosity in tree belts. Ecological Indicators. 2022, 142.

- Clarivate. Citation report: "optical porosity" (Topic) AND "windbreak" (Topic) Web of Science. , 2025. Available from: https://www.webofscience.

- Podhrázská, J., Novotný, I., Rožnovský J., Hradil, M., Toman, F.; Dufková, J., Macků. J., Krejčí, J., Pokladníková, H., Středa, T. Optimizing the functions of windbreakers in agricultural landscape. 2008, Prague: Research Institute for Soil and Water Conservation. 39 p. ISBN 978-80-904027-1-3.

- Podhrázská, J. , Kučera, J. , Doubrava, D., Doležal, P. Functions of Windbreaks in the Landscape Ecological Network and Methods of Their Evaluation. Forests, 2021, 12, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Kučera, J., Fukalová, P., Středová, H., Blecha, M., Jakubíček, R., Chmelík, J., Podhrázská, J., Středa, T. Evaluation of the spatial structure of windbreaks from digital photography. Journal of Ecological Engineering. 2024, 25(10), 381- 391. ISSN 2299-8993.

- Středová, H., Podhrazská, J., Chuchma, F., Středa, T., Kučera, J., Fukalová, P., Blecha, M. The Road Map to Classify the Potential Risk of Wind Erosion. Isprs International Journal of Geo-Information. 2021, 10(4), 269. [CrossRef]

- Středa, T. , Malenová, P. , Pokladniková, H., Rožnovský, J. The efficiency of windbreak on the basis of wind field and optical porosity measurement. 2008. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis. 2008, 56, pp. 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, F. , Wu, J. , Wang, A. et al. A semiempirical model for horizontal distribution of surface wind speed leeward windbreaks. Agroforest Syst. 2020, 94, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thuyet, D. , Van Do, T. , Sato, T. et al. Effects of species and shelterbelt structure on wind speed reduction in shelter. Agroforest Syst. 2014, 88, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WB | Wood species | Shrub species | Age cat.1 | Age avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A 1 | Populus × canadensis Moench, Fraxinus excelsior L., Quercus robur L. | Caragana arborescens Lam. | 5 | 60 |

| A 2 | Populus × canadensis Moench, Juglans nigra L. | Caragana arborescens Lam. | 5 | 60 |

| A 3 | Quercus robur L., Tilia cordata Mill., Juglans nigra L. | Euonymus europaeus L., Chamaecytisus spp. | 4 | 60 |

| A 4 | Juglans nigra L., Populus × canadensis Moench, Ulmus minor Mill. | Chamaecytisus spp. | 4 | 60 |

| B 1 | Juglans nigra L., Populus × canadensis Moench | Sambucus nigra L. | 4 | 50 |

| C 1 | Acer platanoides L., Fraxinus excelsior L. | Caragana arborescens Lam. | 4 | 50 |

| C 2 | Acer platanoides L., Fraxinus excelsior L., Acer negundo L. | Caragana arborescens Lam. | 4 | 55 |

| C 3 | Fraxinus excelsior L., Acer negundo L., Ulmus minor Mill. | Caragana arborescens Lam. | 4 | 50 |

| C 4 | Acer platanoides L., Fraxinus excelsior L., Acer negundo L. | 4 | 55 | |

| C 5 | Acer platanoides L., Acer negundo L., Fraxinus excelsior L. | Caragana arborescens Lam. | 4 | 50 |

| C 6 | Acer platanoides L., Tilia cordata Mill. | 4 | 45 | |

| C 7 | Populus × canadensis Moench, Juglans nigra L., Acer negundo L. | Caragana arborescens Lam. | 4 | 45 |

| D 1 | Juglans nigra L., Quercus robur L. | Rosa canina L., Euonymus europaeus L. | 4 | 55 |

| D 2 | Fraxinus excelsior L., Acer platanoides L., Quercus robur L. | Rosa canina L., Euonymus europaeus L. | 4 | 55 |

| D 3 | Quercus robur L., Juglans nigra L., Acer platanoides L. | Euonymus europaeus L., Ligustrum vulgare L. | 4 | 55 |

| D 4 | Quercus robur L., Ulmus minor Mill., Acer negundo L. | Ligustrum vulgare L., Euonymus europaeus L. | 5 | 55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).