Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

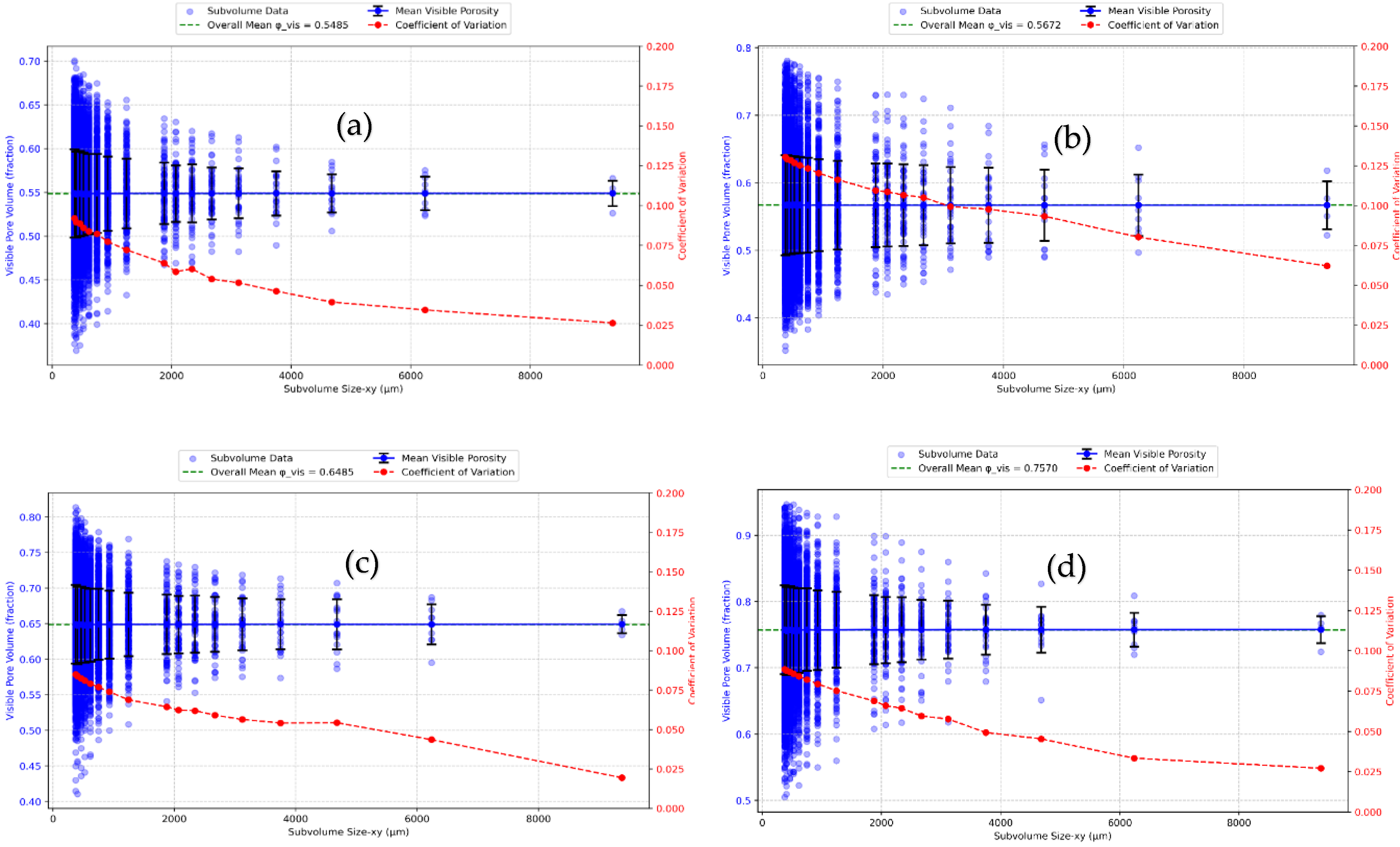

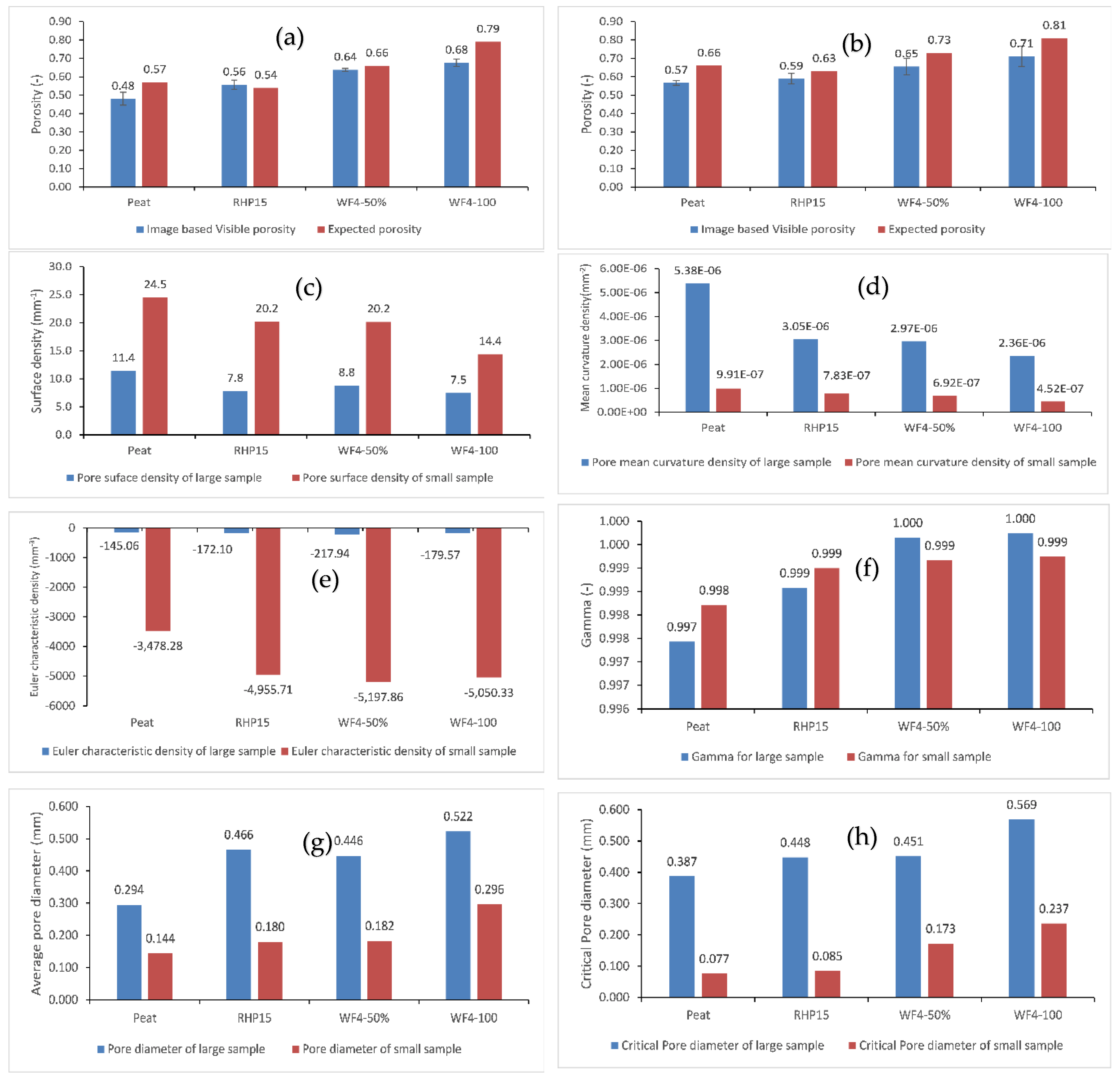

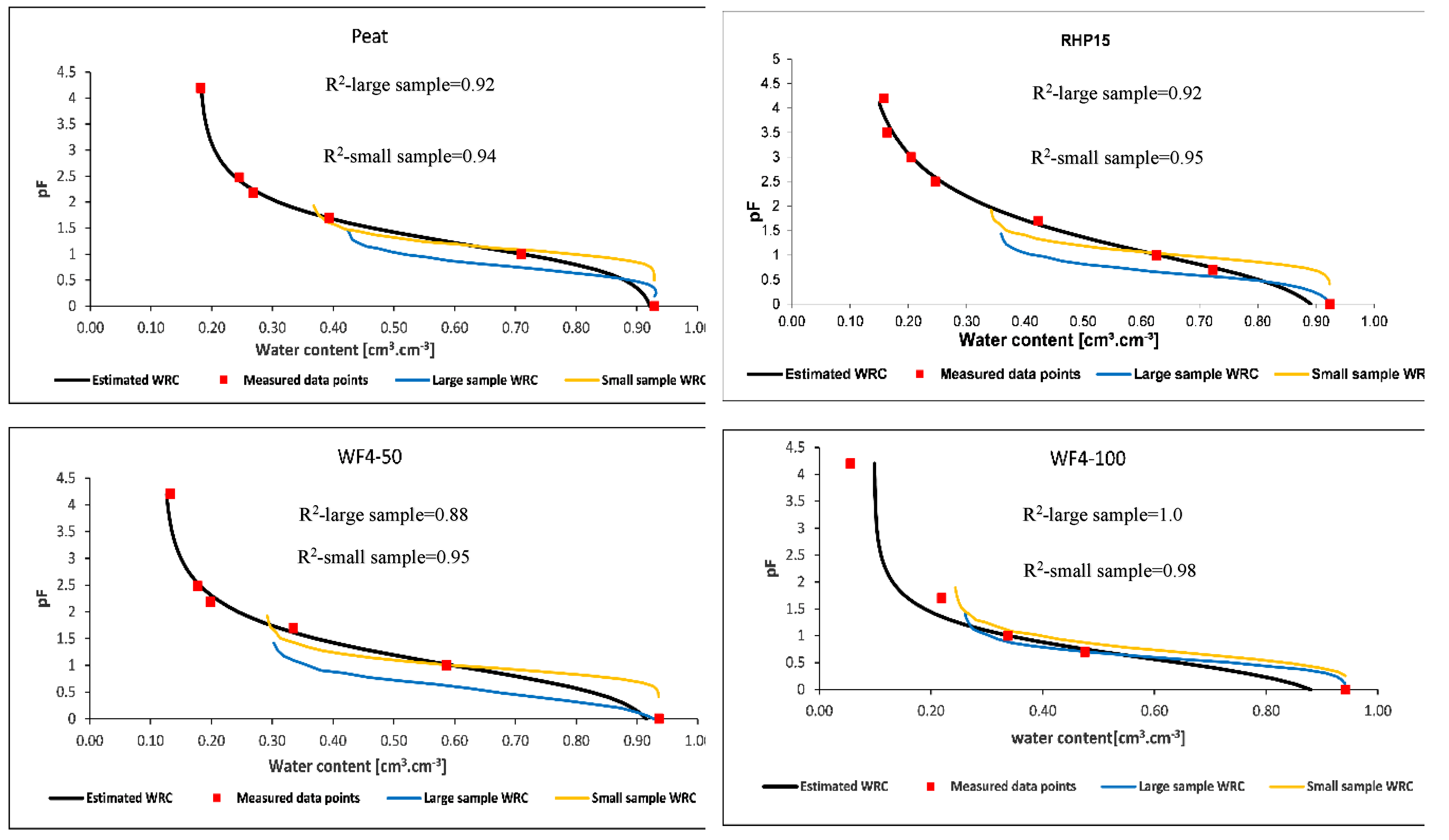

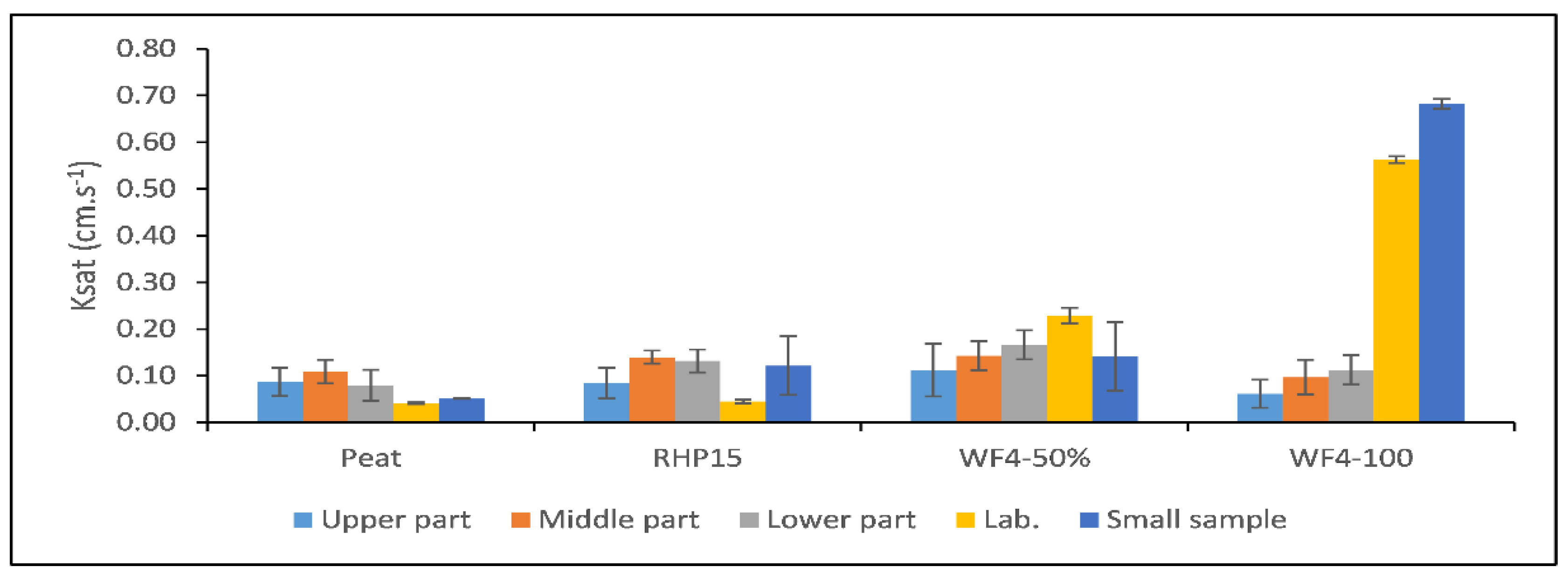

This study investigated the representative elementary volume (REV) for visible porosity in horticultural growing media (peat, commercial mixture, treated wood fibre/peat, pure wood fibre) using x-ray micro-computed tomography (µCT) with 2D and 3D image division, pore morphology, water retention curve (WRC), and saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ksat) via pore network modelling (PNM). Two sample sizes (10 x 10 cm, 3 x 3 cm, height x diameter) with resolutions of 46 and 15 µm were analysed. REV was assessed using deterministic (dREV) and statistical (sREV) criteria, evaluating porosity and coefficient of variation across subvolumes. Results showed 3D division of large samples achieved REV only for pure wood fibre (8000–10000 µm), while 2D division met both criteria for all media. For small samples, 3D division achieved REV only for wood fibre/peat mixture, but 2D division succeeded for all media above 3,000 µm. Pore analyses indicated pure wood fibre had the largest, most connected pores, enhancing drainage, while peat showed complex, retentive structures. WRCs aligned well with lab data (R2 > 0.88). PNM Ksat estimates from small images were more accurate, with discrepancies (21–172%) due to segmentation artefacts. Future studies should incorporate permeability or tortuosity and explore multiscale imaging for improved hydrophysical predictions. This study also highlights advantages unique to X-ray µCT compared to standard laboratory methods, e.g. direct three-dimensional quantification of pore structure parameters and an image-based determination of the REV.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Laboratory Experiment

2.1.1. The Studied Growing Media

2.1.2. Water Retention Curve

2.2. Image Experiment

2.2.1. Sample Packing for Scanning

2.2.2. X-Ray Microcomputed Tomography Scanning

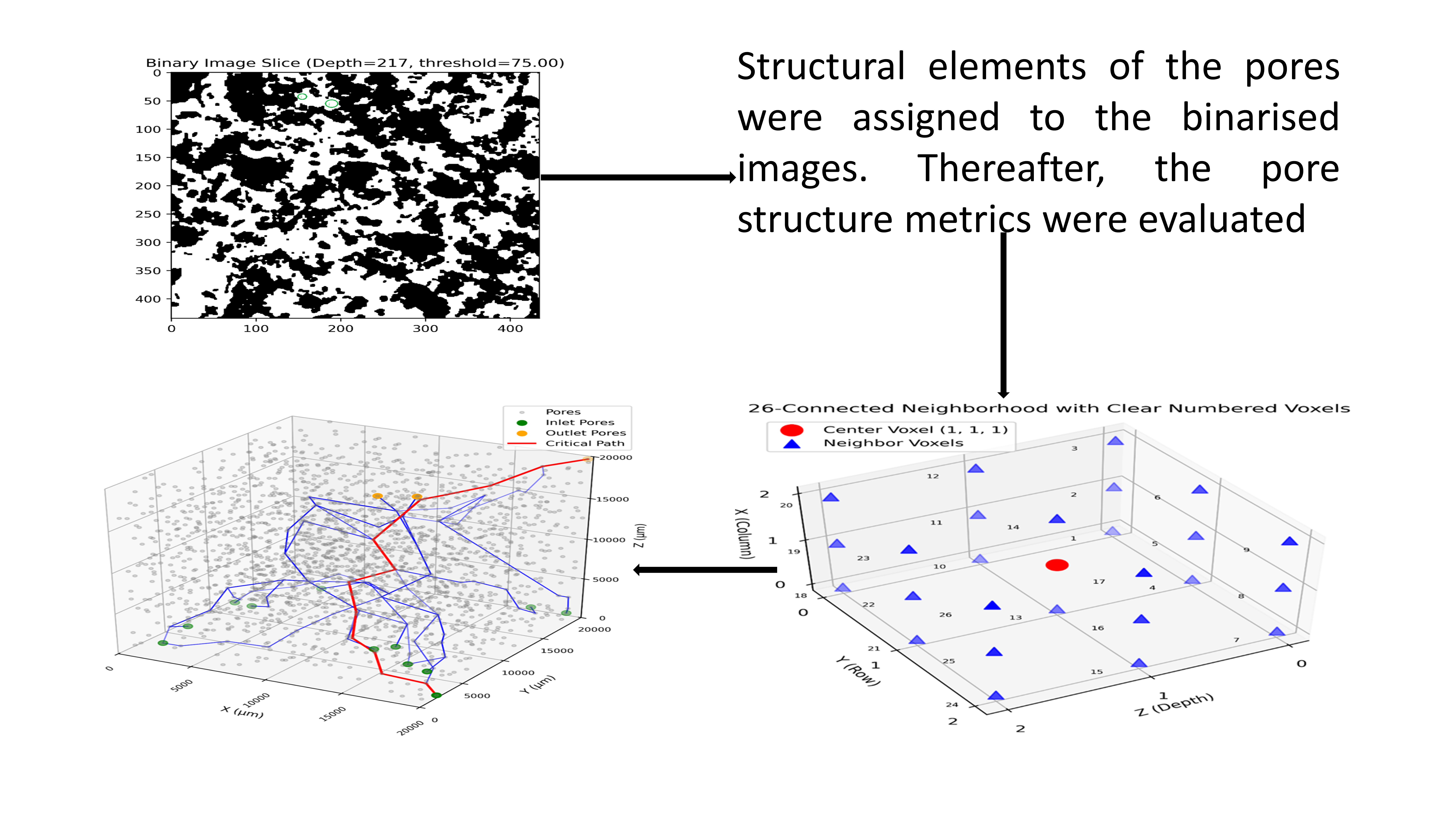

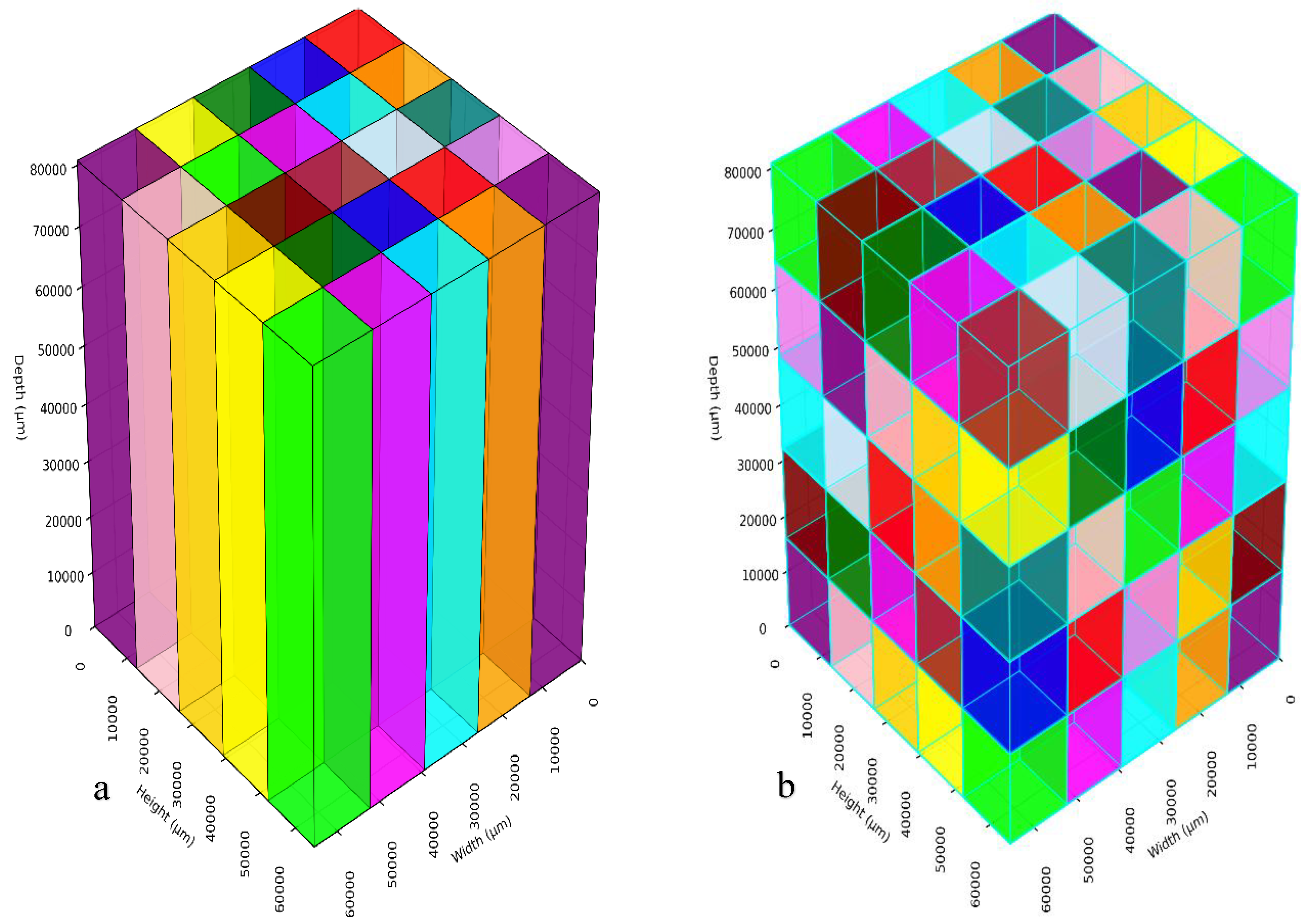

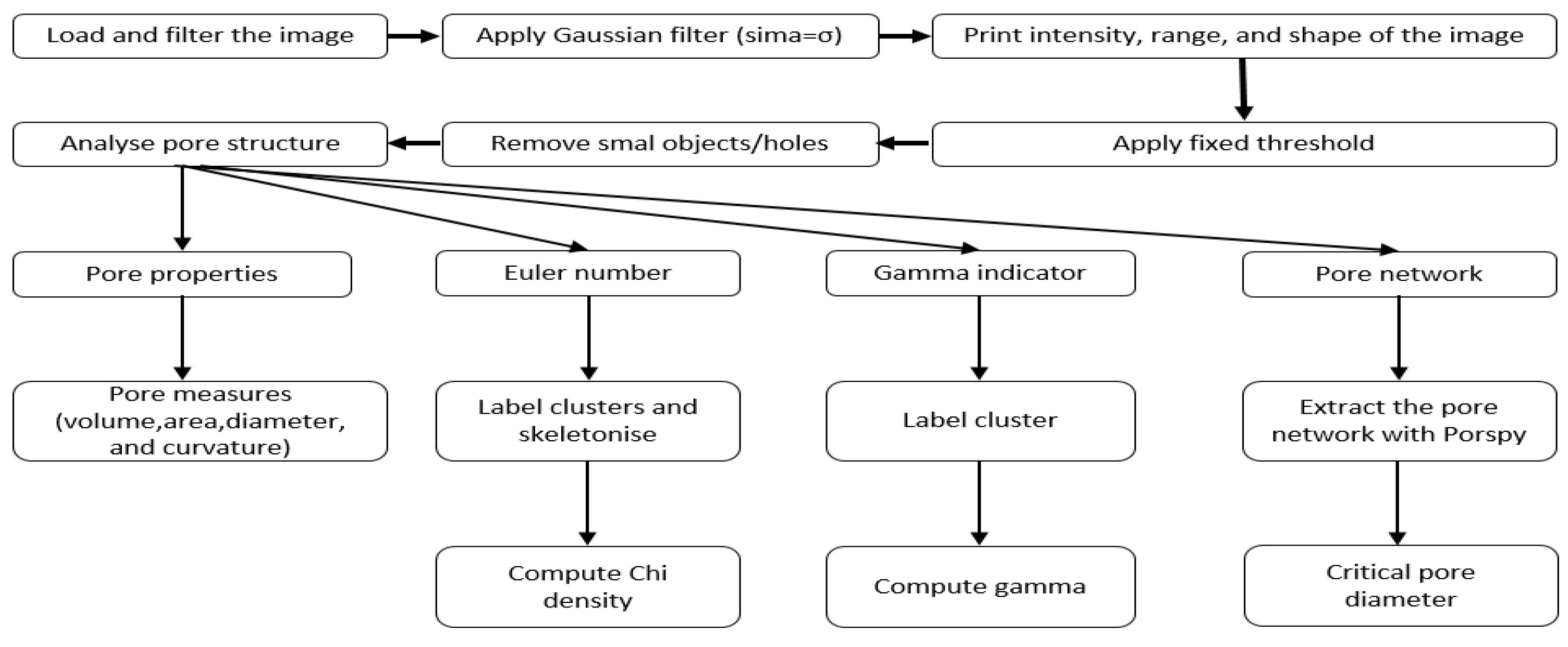

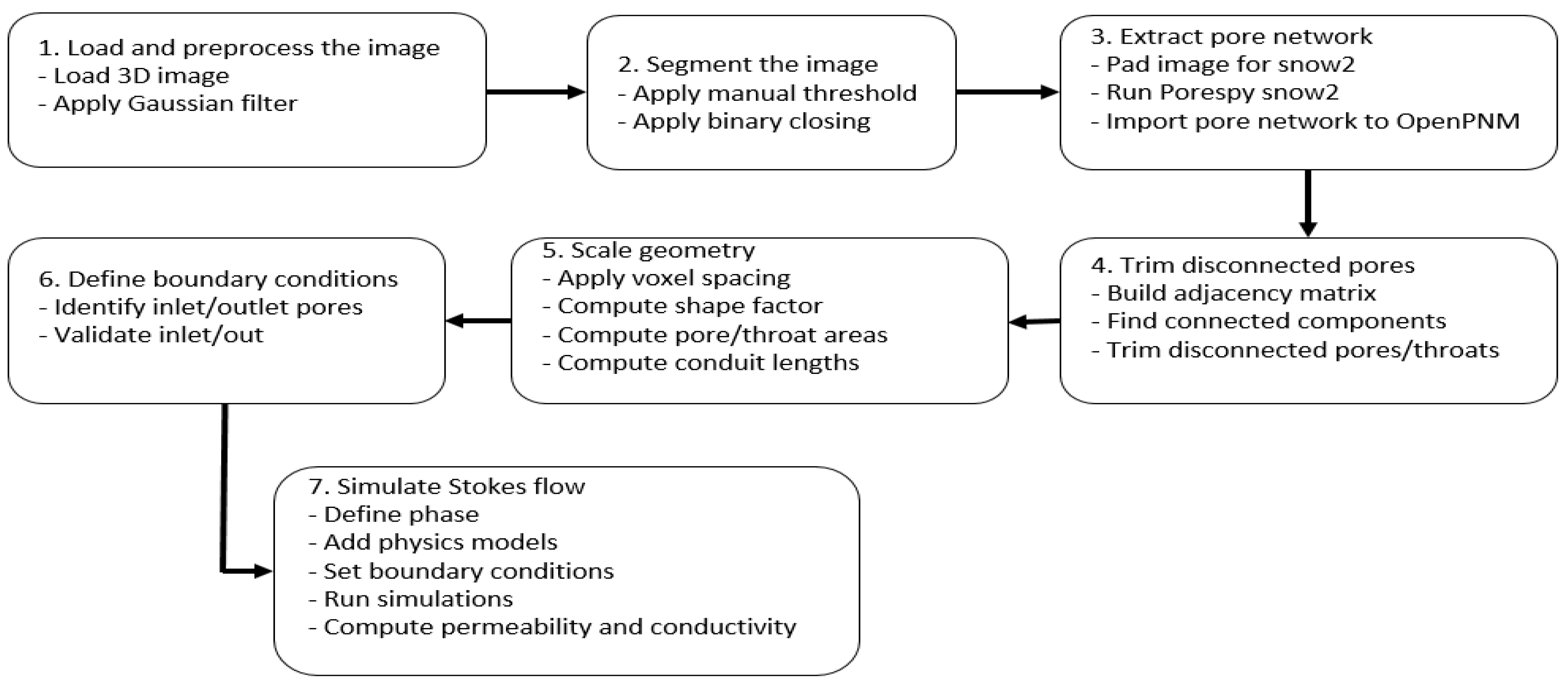

2.2.3. Image Processing and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

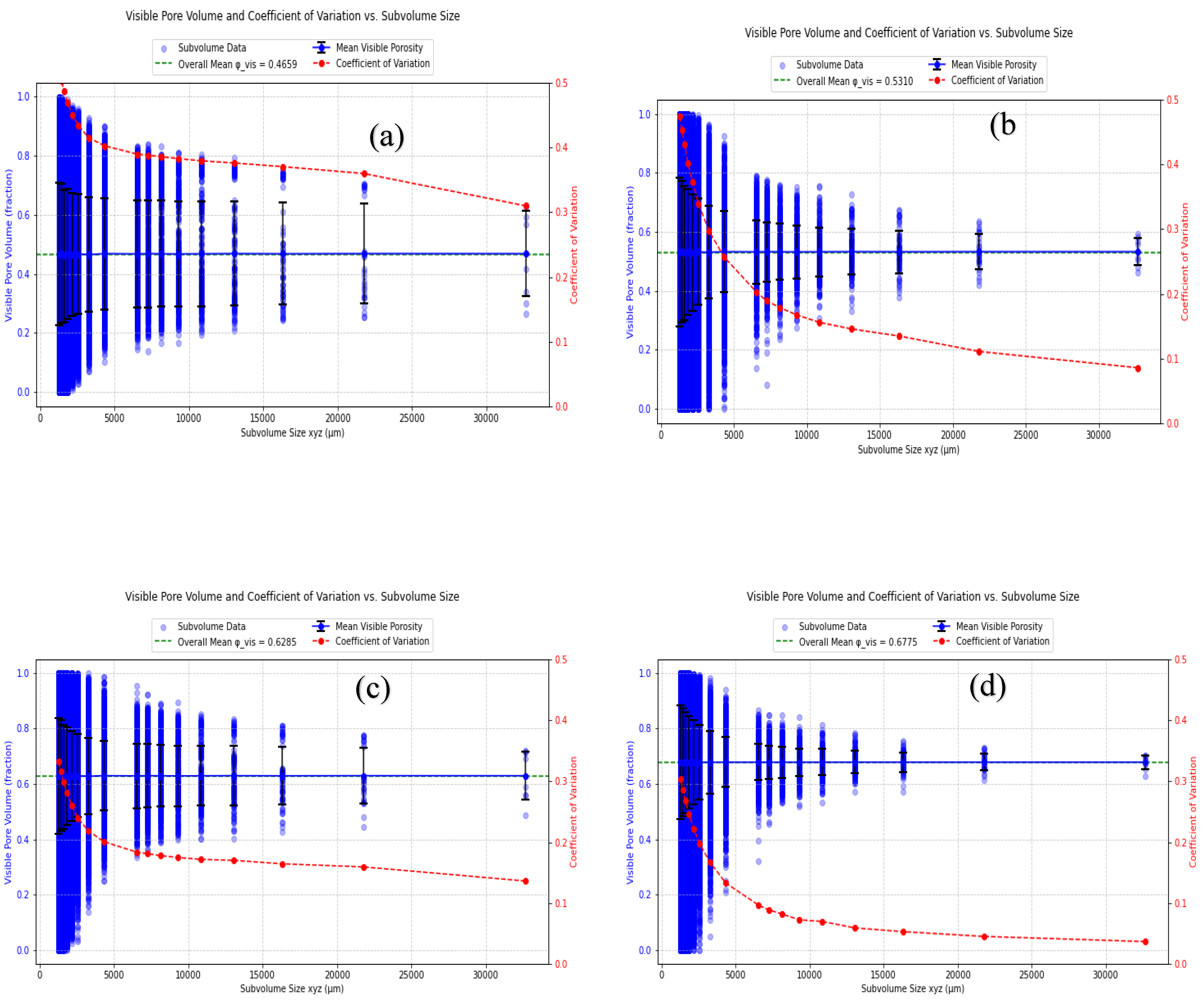

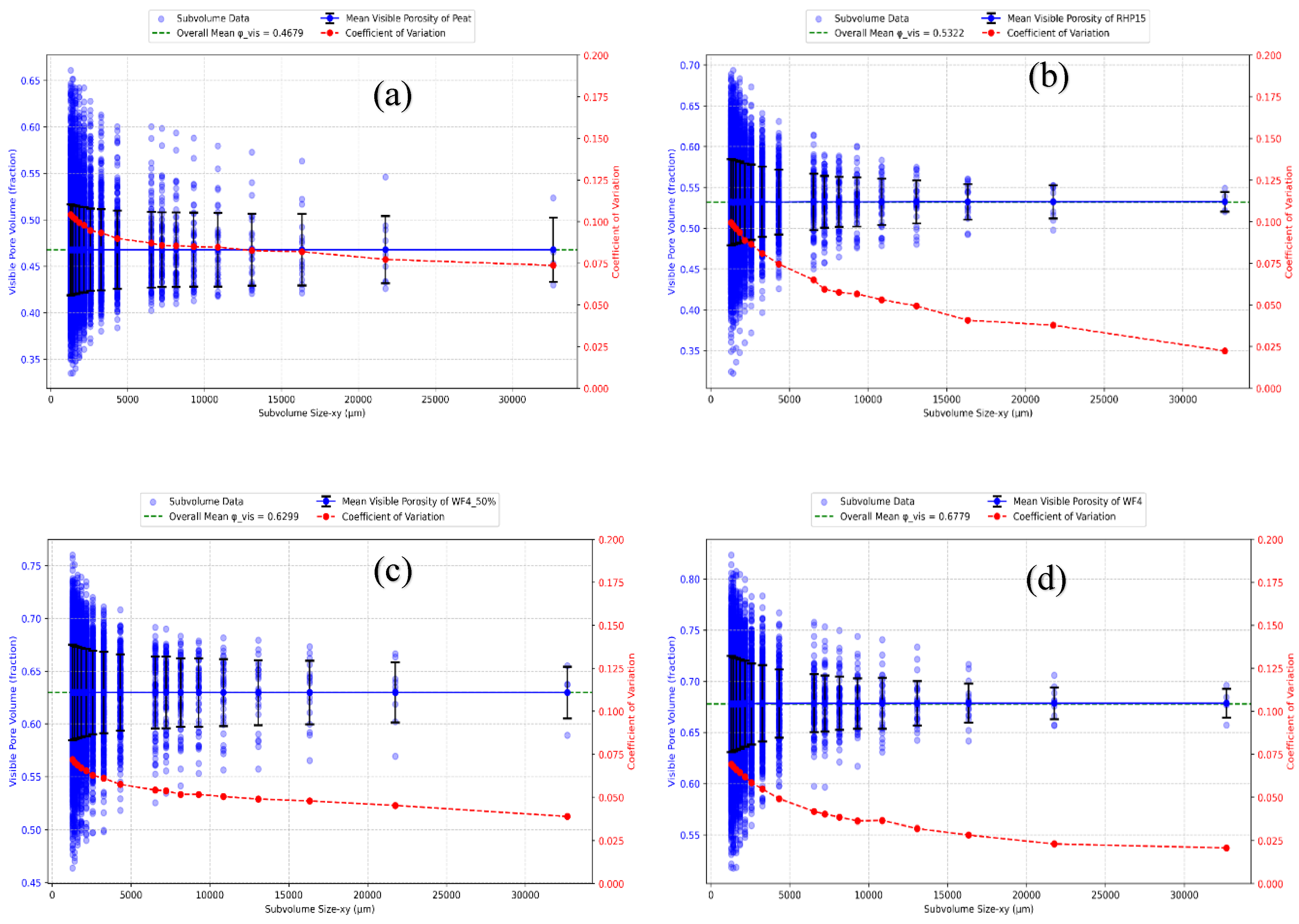

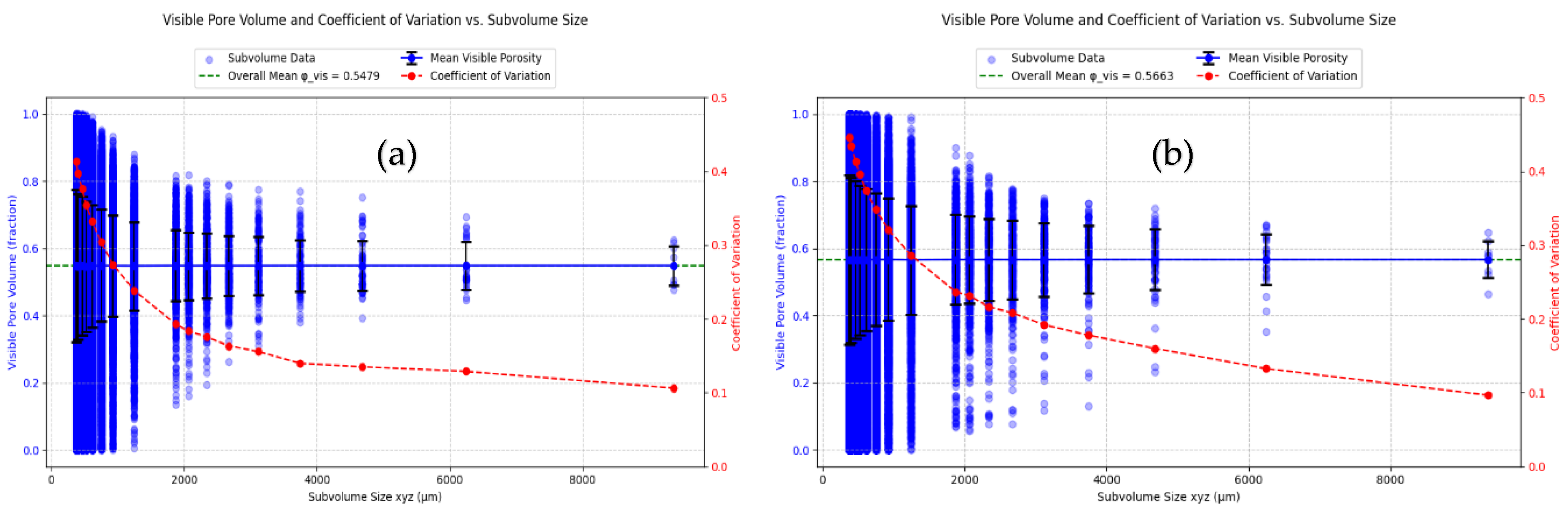

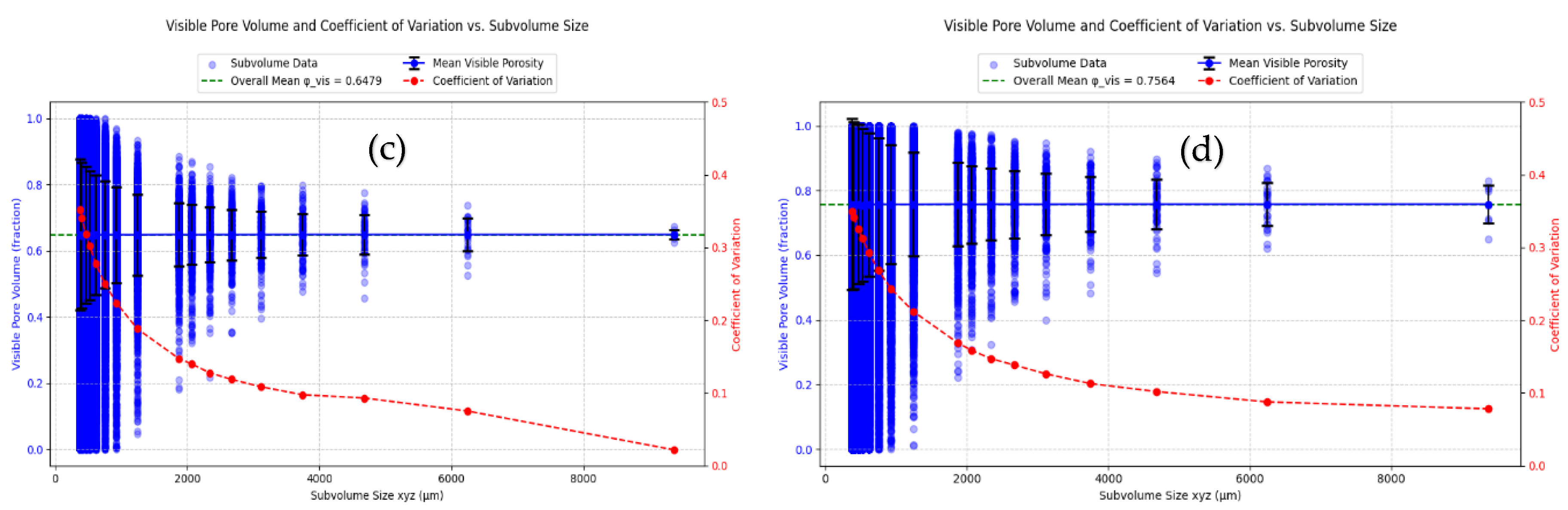

3.1. Analysis of REV

3.2. Pore Structure Measures

3.3. Water Retention Curve

3.4. Estimation of Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Helliwell, J.R.; Sturrock, C.J.; Grayling, K.M.; Tracy, S.R.; Flavel, R.J.; Young, I.M.; Whalley, W.R.; Mooney, S.J. Applications of X -ray computed tomography for examining biophysical interactions and structural development in soil systems: a review. European J Soil Science 2013, 64, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhu, M.; Lu, S. Characterizing soil pore structure using nitrogen adsorption, mercury intrusion porosimetry, and synchrotron-radiation-based X-ray computed microtomography techniques. J Soils Sediments 2015, 15, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, H.-J.; Weller, U.; Schlüter, S. Quantification of soil structure based on Minkowski functions. Computers & Geosciences 2010, 36, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soracco, C.G.; Villarreal, R.; Melani, E.M.; Oderiz, J.A.; Salazar, M.P.; Otero, M.F.; Irizar, A.B.; Lozano, L.A. Hydraulic conductivity and pore connectivity. Effects of conventional and no-till systems determined using a simple laboratory device. Geoderma 2019, 337, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamindu Deepagoda, T.; Chen Lopez, J.C.; Møldrup, P.; Jonge, L.W. de; Tuller, M. Integral parameters for characterizing water, energy, and aeration properties of soilless plant growth media. Journal of Hydrology 2013, 502, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Katuwal, S.; Young, I.; McLeod, M.; Moldrup, P.; Jonge, L.W. de; Clothier, B. Characterising and linking X-ray CT derived macroporosity parameters to infiltration in soils with contrasting structures. Geoderma 2018, 313, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Nie, L.; Xu, Y.; Ji, X.; Liu, B. Characterization of Micro-Scale Pore Structure and Permeability Simulation of Peat Soil Based on 2D/3D X-ray Computed Tomography Images. Eurasian Soil Sc. 2022, 55, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN 19683. Methods of Soil Investigations for agricultural engineering – Physical laboratory tests- part9 : Determination of the saturated hydraulic water conductivity in the cylindrical core-cutter; 1998.

- DIN EN 13041. Soil Improvers and Growing Media-Determination of Physical Properties-Dry Bulk Density, Air Volume, Water Volume, Shrinkage Value and Total Pore Space; 2011.

- DIN EN ISO 11274. Soil quality – Determination of the water-retention characteristic – Laboratory methods. 1127.

- Muhammed, H.H.; Schumm, L.; Anlauf, R.; Reineke, T.; Daum, D. Validity of a Centrifuge-Based Method for Determining the Water Retention Curve of Growing Media. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, J.S.; Owen, J.S.; Stewart, R.D.; Heitman, J.L.; Caron, J. Modeling water fluxes through containerized soilless substrates using HYDRUS. Vadose Zone Journal 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anlauf, R.; Rehrmann, P.; Schacht, H. Simulation of water uptake and redistribution in growing media during ebb-and-flow irrigation. Journal of Horticulture and Forestry 2012, 4, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anlauf, R.; Muhammed, H.H.; Reineke, T.; Daum, D. Water retention properties of wood fiber based growing media and their impact on irrigation strategy. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, H.H.; Anlauf, R.; Daum, D. Estimation of Hydraulic Properties of Growing Media from Numerical Inversion of Mini Disk Infiltrometer Data. Hydrology 2025, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuka, K.; Illerhaus, B.; Fox, C.A.; Joschko, M. X-ray computed microtomography for the study of the soil–root relationship in grassland soils. Vadose Zone Journal 2013, 12, vzj2013–01.0014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuka, K.; Joschko, M. Grassland management intensity determines root development, soil structure, and their interrelationship: Results of a regional study of Leptosols in the Swabian Alps. Grassland Research 2024, 3, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomin, D.S.; Yudina, A.V.; Romanenko, K.A.; Abrosimov, K.N.; Karsanina, M.V.; Gerke, K.M. Soil pore structure dynamics under steady-state wetting-drying cycle. Geoderma 2023, 432, 116401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, A.N.; Otten, W.; Falconer, R.; Monga, O.; Baveye, P.C.; Hapca, S.M. Quantification of the pore size distribution of soils: Assessment of existing software using tomographic and synthetic 3D images. Geoderma 2017, 299, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; Hohenbrink, T.L.; Iden, S.C.; Durner, W. A simple model to predict hydraulic conductivity in medium to dry soil from the water retention curve. Water Resources Research 2021, 57, e2020WR029211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, L.F.; Auler, A.C.; Roque, W.L.; Mooney, S.J. X-ray microtomography analysis of soil pore structure dynamics under wetting and drying cycles. Geoderma 2020, 362, 114103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijfkogel, L.S.; Ghanbarian, B.; Hu, Q.; Liu, H.-H. Clarifying pore diameter, pore width, and their relationship through pressure measurements: A critical study. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2019, 107, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. Comparison of soil tortuosity calculated by different methods. Geoderma 2021, 402, 115358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkholm, L.J.; Heck, R.J.; Deen, B. Soil pore characteristics assessed from X-ray micro-CT derived images and correlations to soil friability. Geoderma 2012, 181-182, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Jia, Y.; Li, T.; Gao, L.; Gan, M. Morphology and multifractal characteristics of soil pores and their functional implication. CATENA 2021, 196, 104822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, I.G.; Losada, J.C.; Heck, R.J.; Tarquis, A.M. Multifractal analysis of 3D images of tillage soil. Geoderma 2018, 311, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; She, D.; Sanz, E.; Martín-Sotoca, J.J.; Tarquis, A.M.; Gao, L. Multifractal analysis on CT soil images: Fluctuation analysis versus mass distribution. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2023, 176, 114080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mady, A.Y.; Shein, E.V.; Abrosimov, K.N.; Skvortsova, E. X-ray computed tomography: Validation of the effect of pore size and its connectivity on saturated hydraulic conductivity. Soil & Environment 2021, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildenschild, D.; Sheppard, A.P. X-ray imaging and analysis techniques for quantifying pore-scale structure and processes in subsurface porous medium systems. Advances in Water Resources 2013, 51, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, U.; Albrecht, L.; Schlüter, S.; Vogel, H.-J. An open Soil Structure Library based on X-ray CT data. Soil 2022, 8, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnin, T.G.; Ivonin, D.A.; Abrosimov, K.N.; Grachev, E.A.; Sorokina, N.V. Analysis of Tomographic Images of the Soil Pore Space Structure by Integral Geometry Methods. Eurasian Soil Sc. 2021, 54, 1400–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhne, J.M.; Schlüter, S.; Vogel, H.-J. Predicting Solute Transport in Structured Soil Using Pore Network Models. Vadose Zone Journal 2011, 10, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.R.; Daly, K.R.; Sturrock, C.J.; Crout, N.M.J.; Mooney, S.J.; Roose, T. Three-dimensional quantification of soil hydraulic properties using X-ray Computed Tomography and image-based modeling. Water Resources Research 2015, 51, 1006–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.T.; McClure, J.E.; Robins, V.; Liu, Z.; Arns, C.H.; Schlüter, S.; Berg, S. Porous media characterization using Minkowski functionals: Theories, applications and future directions. Transport in Porous Media 2019, 130, 305–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestel, J.; Larsbo, M.; Jarvis, N. Scale and REV analyses for porosity and pore connectivity measures in undisturbed soil. Geoderma 2020, 366, 114206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.A.R.; Pires, L.F.; Cássaro, F. am; Roque, W.L.; Heck, R.J.; Rosa, J.A.; Wolf, F.G. X-ray microtomography analysis of representative elementary volume (REV) of soil morphological and geometrical properties. Soil and Tillage Research 2018, 182, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspareto, J.V.; Oliveira, J.A.T. de; Andrade, E.; Pires, L.F. Representative Elementary Volume as a Function of Land Uses and Soil Processes Based on 3D Pore System Analysis. Agriculture 2023, 13, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestel, J.; Larsbo, M.; Jarvis, N. Scale and REV analyses for porosity and pore connectivity measures in undisturbed soil. Geoderma 2020, 366, 114206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, M.; Hyväluoma, J.; Heikkinen, J.; Keskinen, R.; Kaseva, J.; Koestel, J.; Rasa, K. Quantifying Physical Properties of Three Sphagnum -Based Growing Media as Affected by Drying–Wetting Cycles. Vadose Zone Journal 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, W.L.; Elliot, T.; Price, J.S.; Rezanezhad, F.; Heck, R. Measuring physical and hydraulic properties of peat from X-ray tomography. Geoderma 2009, 153, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDLUFA, 1991. VDLUFA (Association of German Agricultural Analytic and Research Institutes) (1991) Methods Book I "Soil Analysis" (1st-6th supplement delivery), 4th edn. VDLUFA-Verlag, Darmstadt.

- DIN EN 13039. Soil Improvers and growing media – Determination of organic content and ash. German Version.; 2009.

- Kemper, W.D.; Rosenau, R.C. Aggregate stability and size distribution. Methods of soil analysis: Part 1 Physical and mineralogical methods 1986, 5, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Genuchten, M.T. A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1980, 44, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.A.R.; Pires, L.F.; Cássaro, F. am; Roque, W.L.; Heck, R.J.; Rosa, J.A.; Wolf, F.G. X-ray microtomography analysis of representative elementary volume (REV) of soil morphological and geometrical properties. Soil and Tillage Research 2018, 182, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspareto, J.V.; Oliveira, J.A.T. de; Andrade, E.; Pires, L.F. Representative Elementary Volume as a Function of Land Uses and Soil Processes Based on 3D Pore System Analysis. Agriculture 2023, 13, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettridge, N.; Binley, A. Characterization of peat structure using X-ray computed tomography and its control on the ebullition of biogenic gas bubbles. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2011, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San José Martínez, F.; Martín, L.; García-Gutiérrez, C. Minkowski functionals of connected soil porosity as indicators of soil tillage and depth. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2018, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Computing in science & engineering 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Walt, S.; Schönberger, J.L.; Nunez-Iglesias, J.; Boulogne, F.; Warner, J.D.; Yager, N.; Gouillart, E.; Yu, T. scikit-image: image processing in Python. PeerJ 2014, 2, e453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoph Gohlke. cgohlke/tifffile: v2025.6.11; 2025.

- Mafi, M.; Martin, H.; Cabrerizo, M.; Andrian, J.; Barreto, A.; Adjouadi, M. A comprehensive survey on impulse and Gaussian denoising filters for digital images. Signal Processing 2019, 157, 236–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza-Robinson, M.S.; Estabrook, B.D.; Fouhey, D.F. Representative elementary volume estimation for porosity, moisture saturation, and air-water interfacial areas in unsaturated porous media: Data quality implications. Water Resources Research 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, K.; Ringrose, P.S. Identifying the representative elementary volume for permeability in heterolithic deposits using numerical rock models. Mathematical geosciences 2008, 40, 753–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Hu, B.X. A new criterion for determining the representative elementary volume of translucent porous media and inner contaminant. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions 2020, 2020, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.A.R.; Pires, L.F.; Belmont Pereira, A. Computed tomography to estimate the representative elementary area for soil porosity measurements. The Scientific World Journal 2012, 2012, 526380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, R.; Chen, S.; Soll, W.E. Pore scale study of flow in porous media: Scale dependency, REV, and statistical REV. Geophysical Research Letters 2000, 27, 1195–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osher, S.; Sethian, J.A. Fronts propagating with curvature-dependent speed: Algorithms based on Hamilton-Jacobi formulations. Journal of computational physics 1988, 79, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethian, J.A. Level set methods and fast marching methods; Cambridge Cambridge UP, 1999.

- Pabst, W.; Gregorová, E. Characterization of particles and particle systems. Available online: https://old.vscht.cz/sil/keramika/Characterization_of_particles/CPPS%20_English%20version_.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Renard, P.; Allard, D. Connectivity metrics for subsurface flow and transport. Advances in Water Resources 2013, 51, 168–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestel, J.; Schlueter, S. Quantification of the structure evolution in a garden soil over the course of two years. Geoderma 2019, 338, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, N.; Yokoyama, T. Permeability of porous media: Role of the critical pore size. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2017, 122, 6955–6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D. Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics. Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam, 2004., 2005, 56 (5). 56.

- Gostick, J.T.; Khan, Z.A.; Tranter, T.G.; Kok, M.; Agnaou, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Jervis, R. PoreSpy: A python toolkit for quantitative analysis of porous media images. Journal of Open Source Software 2019, 4, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouix, S. , Siddiqi, K. Divergence-based medial surfaces 2000. [CrossRef]

- Gostick, J.; Aghighi, M.; Hinebaugh, J.; Tranter, T.; Hoeh, M.A.; Day, H.; Spellacy, B.; Sharqawy, M.H.; Bazylak, A.; Burns, A. OpenPNM: a pore network modeling package. Computing in science & engineering 2016, 18, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzek, T.W.; Silin, D.B. Shape factor and hydraulic conductance in noncircular capillaries: I. One-phase creeping flow. Journal of colloid and interface science 2001, 236, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valvatne, P.H.; Blunt, M.J. Predictive pore-scale modeling of two-phase flow in mixed wet media. Water Resources Research 2004, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira Cassaro, F.A.; Posadas Durand, A.N.; Gimenez, D.; Pedro Vaz, C.M. Pore-Size Distributions of Soils Derived using a Geometrical Approach and Multiple Resolution MicroCT Images. Soil Science Soc of Amer J 2017, 81, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, E.; Plougonven, E.; Gigot, N.; Léonard, A.; Roisin, C.; Brostaux, Y.; Degré, A. Coupling X-ray microtomography and macroscopic soil measurements: a method to enhance near-saturation functions? Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2014, 18, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Magaña, B.; Quintanilla-Domínguez, J.; Ruelas, R.; am Tarquis; Gómez-Barba, L. ; Andina, D. Identification of pore spaces in 3D CT soil images using PFCM partitional clustering. Geoderma 2014, 217, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildenschild, D.; Sheppard, A.P. X-ray imaging and analysis techniques for quantifying pore-scale structure and processes in subsurface porous medium systems. Advances in Water Resources 2013, 51, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, A.N.; Schmidt, S.; am Tarquis; Otten, W. ; Baveye, P.C.; Hapca, S.M. Effect of scanning and image reconstruction settings in X-ray computed microtomography on quality and segmentation of 3D soil images. Geoderma 2013, 207, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smet, S.; Plougonven, E.; Leonard, A.; Degré, A.; Beckers, E. X-ray µCT: how soil pore space description can be altered by image processing. Vadose Zone Journal 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezanezhad, F.; Price, J.S.; Craig, J.R. The effects of dual porosity on transport and retardation in peat: A laboratory experiment. Canadian Journal of Soil Science 2012, 92, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodanović, M.; Lindquist, W.B.; Seright, R.S. 3D image-based characterization of fluid displacement in a Berea core. Advances in Water Resources 2007, 30, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, D.; Smets, B.F.; Wraith, J.M.; Dechesne, A.; Friedman, S.P. Physical constraints affecting bacterial habitats and activity in unsaturated porous media–a review. Advances in Water Resources 2007, 30, 1505–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, M.; Jia, X.; Lair, G.J.; Faraj, P.H.; Blaud, A. Analysing the impact of compaction of soil aggregates using X-ray microtomography and water flow simulations. Soil and Tillage Research 2015, 150, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumasu, J.; Jarvis, N.; Koestel, J.; Larsbo, M. Links between soil pore structure, water flow and solute transport in the topsoil of an arable field: Does soil organic carbon matter? Geoderma 2024, 449, 117001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, R.; Song, X.; Ju, X. Soil pore structure mediates the effects of soil oxygen on the dynamics of greenhouse gases during wetting–drying phases. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 895, 165192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, E.; Moldrup, P.; Schjønning, P.; Jonge, L.W. de. Water retention, gas transport, and pore network complexity during short-term regeneration of soil structure. Soil Science Soc of Amer J 2013, 77, 1965–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peth, S.; Horn, R.; Beckmann, F.; Donath, T.; Fischer, J.; Smucker, A.J. Three-dimensional quantification of intra-aggregate pore-space features using synchrotron-radiation-based microtomography. Soil Science Soc of Amer J 2008, 72, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Qi, S.; Liu, F. Soil water retention and pore characteristics of intact loess buried at different depths. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, M.J.; Bijeljic, B.; Dong, H.; Gharbi, O.; Iglauer, S.; Mostaghimi, P.; Paluszny, A.; Pentland, C. Pore-scale imaging and modelling. Advances in Water Resources 2013, 51, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baveye, P.C.; Laba, M.; Otten, W.; Bouckaert, L.; Sterpaio, P.D.; Goswami, R.R.; Grinev, D.; Houston, A.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J. Observer-dependent variability of the thresholding step in the quantitative analysis of soil images and X-ray microtomography data. Geoderma 2010, 157, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, A.N.; Otten, W.; Falconer, R.; Monga, O.; Baveye, P.C.; Hapca, S.M. Quantification of the pore size distribution of soils: Assessment of existing software using tomographic and synthetic 3D images. Geoderma 2017, 299, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gackiewicz, B.; Lamorski, K.; Sławiński, C.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Chang, L.-C. An intercomparison of the pore network to the Navier–Stokes modeling approach applied for saturated conductivity estimation from X-ray CT images. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Baychev, T.G.; Jivkov, A.P. Review of pore network modelling of porous media: Experimental characterisations, network constructions and applications to reactive transport. Journal of contaminant hydrology 2016, 192, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, A.; Chandel, A.; Shankar, V. Modelling hydraulic conductivity of porous media using machine learning techniques. Journal of Hydroinformatics 2025, 27, 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, S.; Shojaei, M.J.; Lane, N.; Rashid, B.; Lakshtanov, D.; Ning, Y.; Zapata, Y.; Bijeljic, B.; Blunt, M.J. A framework for multiphase pore-scale modeling based on micro-CT imaging. Transport in Porous Media 2025, 152, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Cui, M.; Lei, Y. Comparative analysis on pore-scale permeability prediction on micro-CT images of rock using numerical and empirical approaches. Energy Science & Engineering 2019, 7, 2842–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callow, B.; Falcon-Suarez, I.; Marin-Moreno, H.; Bull, J.M.; Ahmed, S. Optimal X-ray micro-CT image based methods for porosity and permeability quantification in heterogeneous sandstones. Geophysical Journal International 2020, 223, 1210–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substrate | pH | EC | Organic matter | Particle density | MWD* | Pore#break# volume |

Bulk density | Ksat ** |

| - | [dS.m-1] | [%mas] | [g.cm-3] | [mm] | [cm3.cm-3] | [g.cm-3] | [cm.s-1] | |

| Peat | 3.2 | 0.05 | 96.40 | 1.57 | 1.18 | 0.935 | 0.101 | 0.0406 |

| RHP15 | 5.9 | 0.29 | 65.09 | 1.81 | 4.93 | 0.924 | 0.137 | 0.0447 |

| WF4-50 | 3.9 | 0.13 | 98.03 | 1.66 | 1.19 | 0.925 | 0.104 | 0.2286 |

| WF4-100 | 4.3 | 0.16 | 99.40 | 1.55 | 1.30 | 0.942 | 0.091 | 0.5624 |

| Samples | Peat | RHP15 | WF4-50 | WF4-100 |

| Large sample | 75 | 55 | 80 | 85 |

| Small sample | 85 | 53 | 95 | 110 |

| Criteria | Peat | RHP15 | WF4-50 | WF4-100 |

| Large samples 3D division in µm | ||||

| sREV (CV<0.1) | - | 30000 | - | => 8000 |

| dREV | 9000 - 13000 | 9000 - 13000 | 10000 - 16000 | 8000 – 10000 |

| Both criteria fulfilled | no | no | no | yes |

| REV | - | - | - | 10000 |

| Large samples 2D division in µm | ||||

| sRev (CV<0.1) | => 2000 | => 2000 | => 2000 | => 2000 |

| dREV | 13000 – 21000 | 13000 – 21000 | 13000 – 21000 | 13000 – 21000 |

| Both criteria fulfilled | yes | yes | yes | Yes |

| REV | 21000 | 21000 | 21000 | 21000 |

| Small samples 3D division in µm | ||||

| sRev (CV<0.1) | - | 9000 | 4000 | 4000 |

| dREV | 4000 – 9000 | 3000 – 4000 | 3000 – 6000 | 2000 – 3000 |

| Both criteria fulfilled | no | no | yes | no |

| REV | - | - | 4000 | - |

| Small samples 2D division in µm | ||||

| sRev (CV<0.1) | => 500 | => 3000 | => 500 | => 500 |

| dREV | 3000 – 6000 | 3000 – 6000 | 3000 – 6000 | 3000 – 6000 |

| Both criteria fulfilled | yes | yes | yes | Yes |

| REV | 6000 | 6000 | 6000 | 6000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).