1. Introduction

Obesity and asthma are two of the most significant pediatric health problems worldwide, particularly in industrialized nations, and in recent decades their prevalence has increased dramatically. Since 2015, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has listed obesity as a major risk factor for asthma in children. The interrelationship between obesity and asthma derives from a complex interplay of biologic, physiologic, and environmental factors. The mechanisms leading to these disorders may start at a pediatric age and include changes in lung mechanics, comorbidities, dietary intake and low physical activity, alterations in insulin and/or glucose metabolism, and systemic inflammation. Among children who already have asthma, obesity is associated with worse disease severity, more frequent and severe exacerbations, poor symptom control, lower asthma-related quality of life, and a higher risk of requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation [

1].

2. Epidemiology

Several longitudinal epidemiological studies have reported that obesity is a risk factor for asthma later in life, as well as for worse asthma outcomes. Worldwide there are more than 40 million overweight or obese children below the age of 5. The prevalence of asthma in the European Union is 9.4% in children. According the last studies, allergic asthma was greatest in Northern and Western Europe, whereas the highest search volume for bronchial asthma occurred in Western and Eastern Europe [

2]. According to self-reported data from the European Health Interview Survey, 1 in 26 individuals in the Slovak Republic have asthma. The National Register of Asthma in Slovakia further reports that 31% of asthma patients experience moderate or severe persistent asthma, while 27% have seasonal asthma symptoms [

3]. In Italy, asthma is common among children, affecting approximately 10% of the pediatric population [

4]. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis suggests that early life exposure to certain environmental factors can influence an individual's health both during childhood and later in life, asthma may start in utero too. This can be strictly connected to high maternal BMI in pregnancy. As a general trend, asthma prevalence increased as children’s body mass index percentile increased.

3. Asthma Phenotypes

Patients with both obesity and asthma can be classified into two primary categories: asthma complicated by obesity and asthma resulting from obesity [

5]. The phenotype of asthma complicated by obesity includes all asthma phenotypes found in lean patients. A prominent phenotype is early-onset allergic asthma complicated by obesity. This type of asthma typically develops before the age of 12 and is characterized by elevated markers of allergic inflammation, including atopy, allergic symptoms, and high serum immunoglobulin E levels. Additionally, it involves eosinophilic infiltration of the airways and elevated exhaled nitric oxide levels, along with significant physiological changes, severe disease, poor asthma control. These patients are prone to gain weight more rapidly than those with later-onset disease. Obesity may complicate the situation in this group, with both male and female patients equally affected [

6]. Asthma consequent to obesity phenotype includes patients with later-onset disease (≥12 years old), who experience less allergic inflammation and are more likely to be female. Their asthma is typically characterized by less airflow obstruction and hyper-responsiveness, and it tends to be less severe compared to those with earlier-onset disease. Some patients show signs of neutrophilic airway inflammation, while others exhibit minimal cellular airway inflammation. Overall, they have better asthma control and lower symptom scores compared to patients with early-onset asthma. This late-onset phenotype has a Th2 low profile with predominant neutrophil infiltration as well as low IgE and low eosinophilic infiltration. The "obese asthma" phenotype is complex and multifactorial, marked by additional symptoms, worse control, more frequent and severe acute episodes, a reduced response to inhaled corticosteroids, and a lower quality of life compared to other asthma phenotypes [

7].

Table 1.

Obese asthma phenotypes [

8].

Table 1.

Obese asthma phenotypes [

8].

| Obese Asthma Phenotypes |

Early-Onset Asthma |

Late-Onset Asthma |

| Age at onset |

<12 years |

>12 years |

| Gender |

Female= Male |

Female > Male |

| Airway function (FEV1, FVC) |

Severe decrease in airway function |

Minimal airway obstruction |

| Nature |

Atopic |

Non-atopic |

Airway hyperreactivity

|

Severe airway

Hyperresponsiveness |

Less airway Hyperresponsiveness |

Symptom score

|

High symptom score |

Low symptom score |

| Airway inflammation |

Eosinophilic airway infiltration |

Neutrophilic infiltration |

| Th1-Th2 profile |

High Th2 biomarkers |

Low Th2 biomarkers |

4. Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Obesity could worsen asthma through several mechanisms. These include the impact of excess body fat on lung function, which can be influenced by mechanical pressure from truncal fat and/or inflammation. Additionally, factors such as altered nutrient intake (both macro and micronutrients), a sedentary lifestyle and associated obesogenic behaviors linked to obesity contribute to this worsening. The role of obesity in modulating the immune system, particularly through adipocytokines like leptin, has also been proposed as a key factor in the development of asthma in obese children. Asthma has also been linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome, all indicators of metabolic dysregulation that occur in some but not all obese children. Furthermore, genetic and epigenetic variations in molecules involved in metabolic regulation and associated inflammation have been identified as contributing factors in obesity-related asthma.

5. Changes in Lung Mechanics

Weight gain can significantly impact lung physiology, particularly by contributing to chest and abdominal adiposity, which can restrict lung expansion. One of the most notable effects of obesity on lung function is a decrease in functional residual capacity (FRC), with studies showing an inverse relationship between body mass index (BMI) and FRC. This reduction in FRC in obese individuals is mainly due to changes in the elastic properties of the chest wall. When lung volumes are low, the retractive forces of the lung tissue on the airways are diminished, which may reduce the load on the airway smooth muscle (ASM). This decreased load allows the ASM to shorten more easily when activated, either due to an increase in parasympathetic tone or in response to bronchoconstrictor agents. Additionally, low tidal volume (VT) can further decrease strain on the ASM [

1]. Obesity could be a risk factor for increased bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Both asthma and obesity contribute to impaired bronchodilation following deep inhalation, a mechanical airway dysfunction that, in asthmatic individuals, is linked to heightened airway inflammation. As lung volumes decrease, small airway caliber and flow reserves significantly diminish, which predisposes individuals to expiratory flow limitation (EFL). This results in dynamic gas trapping during increased ventilation, such as during exercise or bronchoconstriction episodes [

9]. In general, childhood obesity is associated with normal or elevated forced expiratory volume (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC), but a reduced FEV1/FVC ratio. Recently, it has been observed that childhood obesity is linked to airway dysanapsis, a mismatch between the growth of lung parenchyma and airway caliber. This condition is reflected in normal or even supranormal FEV1 (greater than or equal to 21.645, the fifth percentile, or the lower limit of normal) and FVC (>0.674 or the 75th percentile). However, the larger effect on FVC leads to a lower FEV1/FVC ratio (around 80%) [

10].

6. Immunology of Obesity-Related Asthma

Obesity is linked to ongoing low-level systemic inflammation, which can be viewed as a pro-inflammatory condition. Excess fat tissue plays a key role in the development of chronic, low-grade inflammation in individuals with obesity, leading to the release of cytokines. The number of macrophages in adipose tissue increases, and they release various inflammatory molecules such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), macrophage chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), and complement proteins. As a result, the circulating levels of these molecules are elevated in individuals with obesity [

11]. Additionally, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels are also found to be higher in obese patients. Obesity, as measured by BMI, has a significant correlation with hsCRP levels, while visceral fat is notably associated with IL-6 concentrations. There are various immune responses associated with obese asthma, including Type IVb, where T helper 2 cells play a central role, driven by cytokines such as interleukins 4, 5, 9, and 13. Type IVc, on the other hand, is marked by T helper 17 cells and Type 3 innate lymphoid cells that produce interleukin 17, which helps recruit neutrophils. Type V represents a dysregulated immune response, with heightened activation of T helper 1, 2, and 17 responses. Lastly, Type VI is associated with metabolic-induced immune dysregulation, commonly linked to obesity [

12]. Asthma associated with obesity is mainly driven by non-eosinophilic mechanisms, particularly in the case of late-onset asthma. [

13] Adipokines and other cytokines produced or induced by adipose tissue can also affect the lungs and airways. With increasing adiposity, there is a corresponding increase in leptin, that promotes oxidative and inflammatory response of alveolar macrophages derived from overweight, and a reduction in adiponectin, having protective effects [

14]. All of these data favor the hypothesis that adipokines play important roles in the inflammatory pathogenesis of asthma in obese individuals.

Obesity as a part of the metabolic syndrome that is significantly involved in increasing the risk of a serious course of COVID-19 too, due to hyperdynamic circulation, increased myocardial consumption of oxygen, which results in acute coronary events. A "cytokine storm" is also thought to lead to instability and rupture of atherosclerotic plaques with subsequent thrombosis. Adipocytes and adipocyte-like cells (for example, lung lipofibroblasts), may play an important role in the pathogenesis of the response to COVID-19 [

15].

Figure 1.

Adipose tissue and obesity-related inflammation [

16].

Figure 1.

Adipose tissue and obesity-related inflammation [

16].

7. Oxidative Stress

Both asthma and obesity are linked to elevated oxidative stress, which refers to an imbalance between the production of pro-oxidants and antioxidant defense mechanism in the body. This imbalance can trigger the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and disrupt enzyme activity, exacerbating inflammation. This inflammation can activate immune cells like neutrophils and eosinophils, which generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). The rise in systemic oxidative stress may also correlate with increased production of lipid peroxidation products, protein carbonyls in plasma, and elevated plasma levels of isoprostanes, particularly isoprostane-8. Additionally, there is an increase in oxidized glutathione in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and an increase in nitric oxide (NO) levels in exhaled air. In children with asthma, higher levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and lower levels of glutathione are found in exhaled breath condensate. Glutathione, an antioxidant, helps protect airway epithelial cells from free radicals, while MDA, a byproduct of ROS acting on membrane phospholipids, serves as a marker of oxidative stress. Asthma patients tend to have lower levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase activity, which are associated with reduced lung function. Another obese-asthma association is the change in nitric oxide (NO) metabolism. There is an inverse linear association between exhaled NO with increasing BMI in obese children [

14].

8. Gender

Gender is a significant modifier of the obesity-asthma relationship. Boys are more susceptible than girls and it has been shown that boys who became obese at the age of 9-11 years had a two-fold greater risk of allergic asthma. Multiple studies have shown that the gender differences observed in the relationship between obesity and asthma appear to be linked to hormonal factors during the prepubertal stage (ages 9-11), particularly those related to pro-inflammatory hormones like leptin, adiponectin, and estrogen.

Increased BMI during adolescence is thought to be associated with higher estrogen levels, which could be a mechanism to explain female obesity and later onset asthma [

16].

9. Associated Comorbidities

Obesity-related diseases may increase the risk of developing asthma. Many studies have revealed that gastroesophageal reflux disease may worsen asthma by direct effects on airway responsiveness or via aspiration-induced inflammation, leading to bronchoconstriction. It has been reported that obesity is a risk factor for sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Treating these disorders with nasal continuous positive airway pressure has a significant improvement in asthma outcomes and peak expiratory flow (PEF) rates [

13,

17].

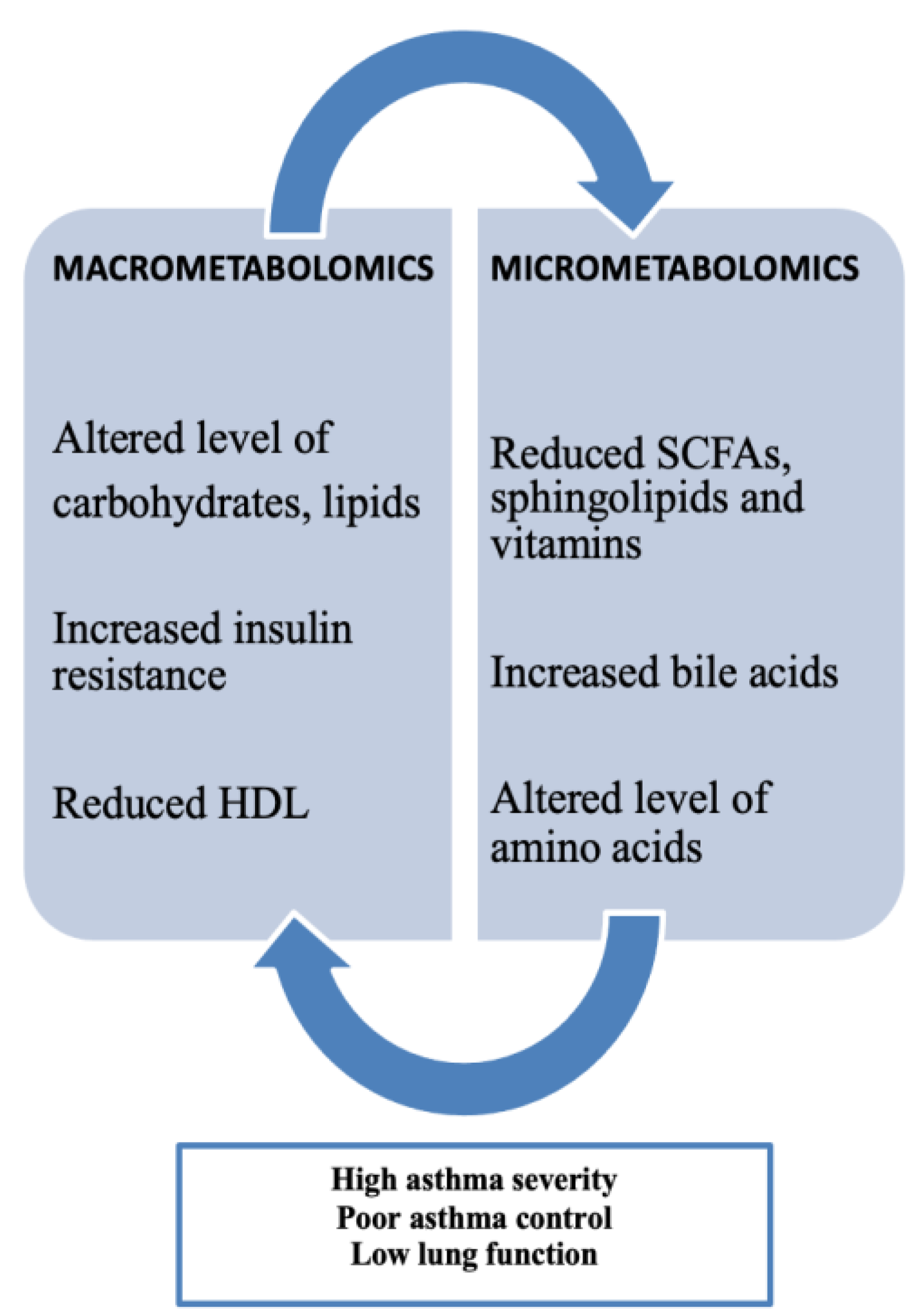

10. Macrometabolic and Micrometabolic Associations in Asthma

Obesity-related asthma involves metabolic patterns highlighting the important role of metabolomics, categorized by both macrometabolic and micrometabolic factors in asthma. Current research indicates that metabolic disturbances are commonly observed in individuals with the "obese asthma" phenotype and align with those seen in metabolic syndrome. Metabolic dysregulation, such as insulin resistance (IR) and altered glucose metabolism, has been consistently linked to both childhood and adult asthma. Children with asthma tend to have a higher prevalence of IR compared to those without asthma, with IR levels correlating to proinflammatory markers like leptin and IL-6, which are associated with increased airway obstruction and reduced lung volumes. There is also evidence suggesting an inverse relationship between IR and lung function, as higher IR levels are linked to a lower FEV1/FVC ratio. Children with asthma have a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia compared to non-asthmatic children, marked by lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL), total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels. Lower HDL levels are associated with a lower FEV1/FVC ratio, further indicating an inverse relationship between dyslipidemia and pulmonary function. Beyond lipoproteins, free fatty acids (FFAs) classified as small-chain, medium-chain, or long-chain based on their carbon chain lengths—play a role in the development of metabolic diseases like obesity, type II diabetes, and atherosclerosis, and have also been linked to respiratory diseases such as asthma [

13].

Figure 2.

Macrometabolites, micrometabolites and obesity-related asthma [

13].

Figure 2.

Macrometabolites, micrometabolites and obesity-related asthma [

13].

Various micrometabolomic biomarkers have been linked to asthma. Sphingolipids are involved in cellular functions through their interactions at the cell membrane. Reduced sphingolipid synthesis has been associated with an increased risk of asthma. A key sphingolipid in asthma research is Orosomucoid like 3 (ORMDL3), which codes for a transmembrane protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum that regulates serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) activity. Variations in the ORMLD3 gene have been linked to a heightened risk of asthma. Sphingolipids also help distinguish between non-allergic and allergic asthma in children, facilitating asthma endotyping. Studies have found that lower levels of sphingomyelins in infants at 6 months old are linked to a higher risk of developing asthma and wheezing by age 3. For children around 6 years old, reduced levels of certain phosphosphingolipids, such as sphinganine-1-phosphate, correlate with increased airway resistance. Amino acids also play a role in asthma development. The metabolism of L-citrulline is a significant biomarker in this context. In healthy individuals, the conversion of L-citrulline to L-arginine is sufficient, but asthma patients show decreased L-arginine production. L-arginine is essential for the production of nitric oxide (NO), a bronchodilator that helps prevent asthma progression. Disruptions in L-arginine metabolism can lead to nitric oxide deficiency and airway constriction, often due to increased arginase activity or the accumulation of inhibitors like asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA). Many studies showed how patients with severe asthma on treatment with a low or normal FeNO would have fewer exacerbations with L-arginine supplementation over a 3-month period compared with patients with high FeNO [

13].

11. Diet and Nutrients

The low levels of vitamins in obese patients, which can be attributed to processed foods and changes in their eating habits, have a direct impact on micronutrient levels, including vitamins. Obesity is often linked to reduced circulating levels of vitamin D, which can result from factors such as limited sunlight exposure, lack of physical activity, insufficient intake of vitamin D-rich foods, dilution due to increased body volume, and storage in fat tissue. Additionally, as preadipocytes and adipocytes have receptors and play a role in vitamin D metabolism, it appears that insufficient vitamin D levels may contribute to adipogenesis and the development of obesity [

18].Authors showed how in patients with bronchial asthma, the frequency of appearance of symptoms during the day >2 times a week was higher in the group with deficiency and insufficiency of vitamin D in the blood, compared to the group with sufficient values of vitamin D in the blood (40% vs. 0%). All cases with sufficient values of vitamin D have manifested daily symptoms less than twice a week [

19]. The data indicates that a loading dose of 50,000 IU of vitamin D, followed by a daily dose of 8,000 IU for 16 weeks, is both safe and effective in reaching serum 25(OH)D levels of at least 40 ng/mL in children with obesity-related asthma. Among those receiving this regimen, 78.6% reached the target level [

17,

20]. Vitamin D deficiency was linked to decreased lung function in obese children with asthma, potentially serving as an indicator of both reduced airway function and lower lung volumes, regardless of systemic inflammation. Carotenoid levels are also associated with obese asthma. Clinical studies showed that serum levels of total carotenoids were lowest in obese asthmatic adolescents. Furthermore, there was a direct positive association between total carotenoids and HDL, suggesting carotenoids could possibly be protective against metabolic dysregulation in pediatric obesity [

13].

12. Obesity-Related Asthma and Gut Microbiota

Obesogenic diets rich in high fat and low fibers modify gut microbiome, promoting obesity and development of allergic airway disease. The gut microbiota primarily acts as a biological barrier and plays a role in immune regulation. However, obesity can disrupt this balance, causing gut microbiota dysbiosis, reduced bacterial diversity, and an increase in Firmicutes while decreasing Bacteroidetes. These changes are key contributors to impaired gut barrier and immune function. Research has shown that an early reduction in gut microbial diversity can be a predictor of asthma development and may lead to allergies through an imbalance in Th2/Th1 immune responses. Obesity-related inflammation and gut dysbiosis can increase intestinal mucosal permeability, allowing lipopolysaccharides to enter the bloodstream. This triggers endotoxemia, where lipopolysaccharides bind to TLR4, activating the NF-kB pathway and leading to the production of cytokines like TNF-a and IL-6. These cytokines can affect the lungs, potentially exacerbating asthma. Additionally, obesity-induced gut dysbiosis can disrupt cholesterol metabolism and lower intestinal bile acid levels, weakening the inhibitory effect of NLRP3. NLRP3 activation promotes IL-1b secretion through M1 macrophages, which in turn triggers AHR, a key feature of asthma. Bacterial colonization has an important role in fermentation of dietary fiber and generation of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), low fibers diet may lead to changes in gut microbiome and SCFA levels, especially levels of SCFA propionate. Bacteroidetes bacteria, a major producer of SCFAs, are reduced in the gut in obesity and in the lungs of asthmatic patients [

18]. Furthermore, in obese children with pediatric fatty liver disease, research has demonstrated how gut microbiota and its metabolites influence the liver through the portal vein to regulate bile acid production as well as hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism. Disruptions in the gut-liver axis are crucial in the disease's development, including alterations in the intestinal microbiome and liver barrier dysfunction. Modifying the gut microbiome has shown promising results in treating various metabolic disorders in experimental models, with the use of probiotics leading to reductions in intrahepatic triacylglycerol levels and AST activity [

21]. Another influencing factor could be the effect of antibiotic on microbiome. Antibiotic exposure early in life has been associated with asthma, obesity and later life atopy, modifying the maturation of the immune system. Probiotic supplementation in early life reduces risk of atopy. An important point to discuss is the impact of lifestyle factors in both asthmatic and obese children. They can present with low levels of physical activity and generally sedentary behavior (e.g., watching television or playing video games), that may worse lung function and physical performance.

13. Prenatal Factors

Prenatal factors may contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma in childhood.

Prenatal diet and intrauterine exposure to pollutants and smoking can influence the development of the infant’s innate and adaptive immune systems. This can make the infant more vulnerable to early-life infections such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and human rhinovirus (HRV), which can increase the risk of recurrent wheezing and asthma in later childhood [

22].

14. Genetics and Genomics

Asthma and obesity share genetic factors. A group of genes increases the susceptibility to both asthma and obesity. Chromosome 5q contains genes ADRB2, beta2-adrenergic receptor gene, that influences sympathetic nervous system activity and regulates airway tone and resting metabolic rate. The Agr16 polymorphism of this receptor is linked to certain asthma phenotypes, including nocturnal asthma. The Gln27 polymorphism of the same receptor is highly associated with obesity and influences the bronchodilator response to beta2-agonists. Chromosome 5q contains also genes NR3C1, that codes for glucocorticoid receptor, and its polymorphism is significantly associated with bronchial asthma and obesity, influencing the accumulation of abdominal visceral fat. Several studies have shown a link between the 308-G/A polymorphism in the TNF-alpha gene and both asthma and obesity. The NcoI variant in the lymphotoxin-A gene (LTA, located at 6p21.3), which interacts with the TNF 308-G/A polymorphism, has been connected to various asthma-related traits, including atopic asthma. Meanwhile, the T60N polymorphism in the LTA gene has been associated with waist circumference and other metabolic syndrome characteristics. Chromosome 12q, which contains genes for inflammatory cytokines, also plays a role in both asthma and obesity. Several variants of the vitamin D receptor gene (VDR, located at 12q13), which regulate immune functions, can suppress Th2-mediated allergic airway diseases. For instance, in Italian children, lower serum vitamin D levels correlate with poorer lung function, increased exercise-induced hyperresponsiveness, and worse asthma control. Furthermore, a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified DENND1B as an asthma susceptibility gene in children, with evidence suggesting that certain variants of DENND1B may also be linked to BMI in children with asthma.

However, the association was overall not replicated in the independent data sets and the heterogeneous effect of

DENND1B points to complex associations with the studied diseases that deserve further study [

23].

15. Diagnosis

The diagnosis of asthma is primarily based on a comprehensive patient history that helps identify the pattern of symptoms (episodic or continuous), triggers (such as work, exercise, exposure to allergens, or smoke), and the timing of onset in relation to obesity and asthma. Spirometry is used to assess if there is baseline airflow limitation (obstruction), characterized by a reduced FEV1/FVC ratio, determine the reversibility of this obstruction, and rule out restrictive patterns as an alternative cause of dyspnea [

24]. Bronchoprovocation testing is another valuable diagnostic tool, particularly for patients with unusual asthma presentations or isolated symptoms like persistent cough. Peak expiratory flow (PEF) is more commonly used to monitor patients with a confirmed asthma diagnosis or evaluate the impact of specific occupational or environmental triggers, rather than being used for initial asthma diagnosis [

25]. Measuring nitric oxide in exhaled breath can also assist in diagnosing asthma. Elevated levels of exhaled nitric oxide (fractional exhaled nitric oxide [FENO] ≥40-50 parts per billion) can help confirm asthma. In children, a low FENO is associated with higher adiposity indicators (such as BMI, body fat percentage, and waist circumference), while a high FENO suggests poorly controlled asthma [

26]. While there are no specific blood tests for asthma, a complete blood count (CBC) with a differential white blood cell analysis can help detect eosinophilia or anemia, which might be relevant in certain cases. Allergy testing includes measuring the total serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels and testing for specific IgE antibodies against inhalant allergens, either through blood tests or skin testing.

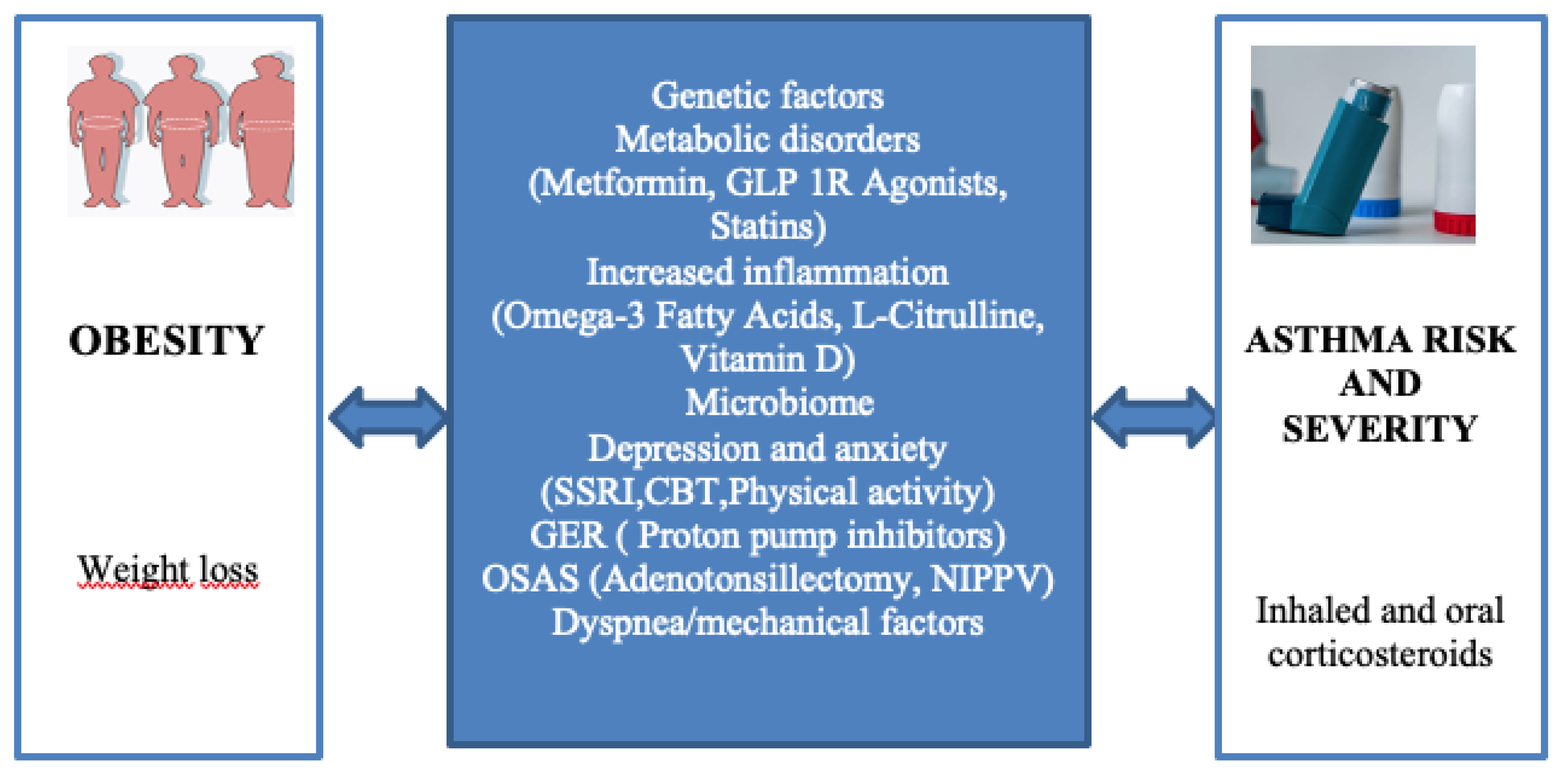

16. Management of Childhood Obese-Asthma

Managing obese children with asthma requires special attention and is more challenging than managing asthmatic children with a normal weight. Key differences may include reduced responsiveness to standard controller medications, varying thresholds for determining asthma phenotype to guide biologic therapy, the significance of comorbidities, and the importance of weight loss. Research has shown that weight reduction through intensive lifestyle changes, such as modifications in diet, physical activity, and behavior, can have a significant impact on children with both obesity and asthma. Involving the whole family in these changes is essential. Approaches like motivational interviewing, goal-setting encouragement, behavior monitoring, and positive reinforcement appear to be effective strategies, helping clinicians personalize interventions based on the patient’s behavioral and psychological needs. Generally, recommendations include a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, limiting sugary -sweetened drinks, regular breakfasts, allowing the child to have some control over their meals, avoiding overly restrictive feeding practices, and encouraging the involvement of the entire family in making lifestyle changes.

A high-fiber diet increases SCFA concentrations in the gut and circulation, thereby suppressing weight gain and allergic inflammation, which were dependent on gut microbiota metabolism. Studies have also shown a link between obesity and changes in fecal short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) profiles. Increasing SCFA levels could therefore be helpful for individuals with obesity-related asthma. Additionally, gut bacteria can ferment undigested or unabsorbed food to produce conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), including trans-10 and cis-12 CLA, which may help reduce overall body fat by targeting fat stores in areas such as visceral, inguinal, and brown/interscapular fat. This suggests that CLA supplementation might be more effective in preventing fat mass regain after weight loss than in promoting weight loss itself. Certain bacteria, like

Bifidobacterium,

Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, and

Bifidobacterium breve, can convert free linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid into various forms of CLA. As a result, CLA and related compounds present a promising new approach for weight management that could also alleviate symptoms of obesity-related asthma [

18]. Many studies showed that vitamin D supplementation in children with mild asthma, and achieving vitamin D levels of 30ng/ml may be a variable strategy for optimizing lung function and in a way for remodelling patients previously diagnosed with bronchial asthma [

19]. Some studies show the beneficial effect of statins in the context of asthma, lowering FFAs and subsequently decreasing airway hyperresponsiveness by modulation of ASM cells. Innovative research discovered anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of statins beyond their cholesterol lowering function, demonstrating that simvastatin attenuates eosinophilic airway inflammation via inhibition of HMG-CoA [

13]. Drug therapy for obesity, such as orlistat, liraglutide, and other options, may be suitable for patients who have not achieved weight loss through behavioral lifestyle changes alone and are experiencing serious obesity-related complication [

27]. Bariatric surgery is generally recommended for obese asthma patients who have a BMI of 35 kg/m² or higher and who have not been able to lose sufficient weight by other methods [

28].

Figure 3.

Select pathways involved in obesity-related asthma and potential interventions for the management of patients with asthma in the setting of obesity [

17].

Figure 3.

Select pathways involved in obesity-related asthma and potential interventions for the management of patients with asthma in the setting of obesity [

17].

17. Pharmacological Treatment of Obese-Asthma

Pharmacological treatment is the mainstay of management in most patients with asthma, though in obese patients, treatment of comorbidities and lifestyle interventions are likely particularly important. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) acknowledges the potential role of obesity in both the diagnosis and management of asthma. However, it's crucial to recognize that some respiratory symptoms commonly seen in obese individuals, such as shortness of breath during physical activity, might resemble asthma symptoms [

29]. As a result, in obese patients, asthma diagnosis should involve objective tests to assess variable airflow limitations that respond to bronchodilators.

Children with both obesity and asthma might show a reduced response to asthma medications, but inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and bronchodilators remain the primary treatment options. Both GINA and other national guidelines, including those in the US, suggest that clinicians should consider weight loss interventions for obese asthma patients [

30]. Patients with severe asthma who require high doses of inhaled glucocorticoids along with a second controller or continuous oral glucocorticoid treatment may benefit from monoclonal antibodies against IL-5 (mepolizumab and reslizumab), IL-5 receptor alpha (benralizumab), and IL-4 receptor alpha subunit (dupilumab) [

31]. Long-term systemic glucocorticoid use is generally avoided due to side effects like weight gain and metabolic dysfunction. For these patients, treatment options like omalizumab are considered, especially in those weighing over 150 kg [

31,

32]. The primary aim in asthma management is to optimize symptom control, reduce the risk of exacerbations, and minimize medication side effects, enabling patients to partecipate in work, school, recreation, and sports without restrictions. The four key components of asthma management are patient education, managing triggers, monitoring changes in symptoms or lung function, and pharmacological treatment.

18. Conclusion

Obesity is an important risk factor for asthma morbidity in children. More than simple co-existence exists between asthma and obesity. Bi-directional pathophysiology links are explored but causality is not clear. Possible underlying mechanisms may involve a common genetic factor, dietary and nutritional influences, changes in the gut microbiome, systemic inflammation, metabolic issues, and alterations in lung structure and function.

Systemic inflammation in obesity upregulating airway inflammation in asthma in combination with mechanical alterations of respiratory function play key role. Both obesity and asthma lead to decreased physical activity resulting in further deterioration of the conditions as a vicious circle. Patient susceptibility depends on the interaction with genetic, environmental, developmental, life style and clinical factors. Obese asthma phenotype conveys more severe disease and poorer response to treatment. Weight management through multidisciplinary intervention with effective asthma management is a key strategy including increasing physical activity and improving adherence to dietary guidelines. Currently, weight losing medications are allowed only in rare and very selected cases and bariatric surgery not recommended before 18 years of age. Further research and understanding of the obesity-asthma relationship is needed.

Early interventions for children with asthma and/or wheezing may be warranted to prevent a vicious cycle of worsening obesity and asthma that could contribute to the development of other metabolic diseases in later life.

Author Contributions

C.M. wrote the manuscript, and L.B. revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project no. 2019-1.3.1-KK-2019-00007 was implemented with the support provided from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary, financed under the 2019-1.3.1-KK funding scheme. This project has been supported by the National Research, Development, and Innovation Fund of Hungary, financed under the TKP2021-NKTA-36 funding scheme.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks goes to prof. László Barkai.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Forno, E. Pediatric obesity-related asthma. Pediatr Respir J. 2023,1(2), 67-73. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6497-9885.

- Wecker, H.;Tizek,L.;Ziehfreund, S. ; Kain,A.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Zimmermann, G.S.; Scala,E.; Elberling,J.; Doll,A.; Boffa, M.J.; Schmidt, L.; Sikora, M.; Torres,T.; Ballardini, N.; Chernyshov, P.V.; Buters, J.; Biedermann, T.; Zink, A. Impact of asthma in Europe: A comparison of web search data in 21 European countries. World Allergy Organ J.2023, 2;16(8). [CrossRef]

- Kristufek, P.; Letkovicova, H.; Pruzinec, P. Incidence of bronchial asthma in Slovakia – analysis of the first year of data collection. Lekársky Obzor. 2000, 49: 87-90. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/295178808_Incidence_of_bronchial_asthma_in_Slovakia_-_Analysis_of_the_first_year_of_data_collection.

- Tosca, M.A.;D’Avino, A.; Di Mauro, G.; Marseglia, G.L.;Miraglia Del Giudice, M.; Ciprandi, G.; SIAIP Delegates; FIMP Delegates. Intersocietal survey on real-world asthma management in Italian children. Ital J Pediatr 50. 2024,140. [CrossRef]

- Peters,U.;Dixon,A.E.;Forno,E. Obesity and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000,141:1169. [CrossRef]

- Holguin, F.; Cardet, J.C.;Chung, K.F., et al. Management of severe asthma: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J.2020, 55. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.E.; Poynter, M.E. Mechanisms of Asthma in Obesity. Pleiotropic Aspects of Obesity Produce Distinct Asthma Phenotypes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016, 54:601. [CrossRef]

- Di Genova,L.;Penta,L.;Biscarini,A.; Di Cara, G.;Esposito,S. Children with Obesity and Asthma: Which Are the Best Options for Their Management? Nutrients. 2018, 2;10(11):1634. [CrossRef]

- Oudjedi,A.; SAID AISSA, K. Associations between obesity, asthma and physical activity in children and adolescents. Apunts Sports Med. 2020, 55(205):39-48. [CrossRef]

- Forno, E.; Weiner, D.J.;Mullen, J.; et al. Obesity and Airway Dysanapsis in Children with and without Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017, 195(3):314-323. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.E., Holguin, F., Sood, A.,et al. American Thoracic Society Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Obesity and Lung Disease. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop report: obesity and asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc.2010, 7(5):325-35. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, F.C.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Moreira, A. Obesity and Asthma: Implementing a treatable trait care model. Clin Exp Allergy. 2024, 54 (11): 881-894. [CrossRef]

- Roshan, L.; Cechinel, L.R., Freishtat, R.; et al. Metabolic Contributions to Pathobiology of Asthma. Metabolites. 2023,13, 212. [CrossRef]

- Baffi, C.W.; Winnica, D.E.;Holguin, F.Asthma and obesity: mechanisms and clinical implications. Asthma res and pract . 2015, 1,1. [CrossRef]

- Kuchta, M. COVID-19 a vzájomné vzťahy s komorbiditami – obezita, metabolický syndróm. Ateroskleróza XXIV. 2024,1,2:1414-1418.https://www.upjs.sk/lekarska-fakulta/fakulta/casopisy-vydavane-lf/ateroskleroza/archiv.

- Chen, Y.C.; Dong, G.H.; Lin, K.C.;Lee, Y.L. Gender difference of childhood overweight and obesity in predicting the risk of incident asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14(3):222-31. [CrossRef]

- Averill, S.H.; Forno, E.Management of the pediatric patient with asthma and obesity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 132(2024)30−39. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, X.; Dong, B.; et al. Obesity-related asthma and its relationship with microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024,13:1303899. [CrossRef]

- Emir, B.; Lidvana, S.; Vlora, I., et al. Vitamin D deficiency in obese patients diagnosed with bronchial asthma. Authorea. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O'sullivan, B.; Ounpraseuth,, S.; James, L.; et al. Vitamin D Oral Replacement in Children With Obesity Related Asthma: VDORA1 Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther.2024,115(2):231-238. [CrossRef]

- Kuchta, M.;Ďurošková, Z. Od NAFLD (nealkoholová tuková choroba pečene) k MAFLD (s metabolickou dysreguláciou asociovaná tuková choroba pečene) až k PedFLD (pediatrická tuková choroba pečene). Ateroskleroza XXVII. 2023, 3,4, 1861-1866. https://www.upjs.sk/lekarska-fakulta/fakulta/casopisy-vydavane-lf/ateroskleroza/archiv/.

- Forno, E.; Celedón, J.C.The effect of obesity, weight gain, and weight loss on asthma inception and control. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2017,17(2):123-130. [CrossRef]

- Melén, E.R.; Granell, R.; Kogevinas, M.; et al..Genome-wide association study of body mass index in 23000 individuals with and without asthma. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2013,43: 463. [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Miller, M.; et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2021, 60(1):2101499. [CrossRef]

- Fanta, C.H.;Lange-Vaidya,N. Asthma in adolescents and adults: Evaluation and diagnosis.UpToDate. 2022, 1-49. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/asthma-in-adolescents-and-adults-evaluation-and-diagnosis.

- Han, Y.Y.; Forno, E.; Celedón, J.C. Adiposity, fractional exhaled nitric oxide, and asthma in U.S. children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014, 190:32. [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.E. Obesity and asthma in children: Current and future therapeutic options. Paediatr. Drugs.2014, 6:179–188. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.E.;Pratley, R.E.;Forgione, P.M.; et al. Effects of obesity and bariatric surgery on airway hyperresponsiveness, asthma control, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011, 128:508. [CrossRef]

- Neder, J.A.; O'Donnell, D.E. The severe asthma–obesity conundrum: Consequences for exertional dyspnoea and exercise tolerance in men and women. Respirology. 2022, 27( 12): 1002– 1005. [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Available online: www.ginasthma.org (Accessed on 20th January 2025).

- Gibson,P.G.; Reddel, H.; Mcdonald, V.M.; et al. Effectiveness and response predictors of omalizumab in a severe allergic asthma population with a high prevalence of comorbidities: the Australian Xolair Registry. Intern Med J. 2016, 46:1054. [CrossRef]

- Sposato, B.; Scalese, M.; Milanese, M.; et al. Factors reducing omalizumab response in severe asthma. Eur J Intern Med.2018, 52:78. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).