Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

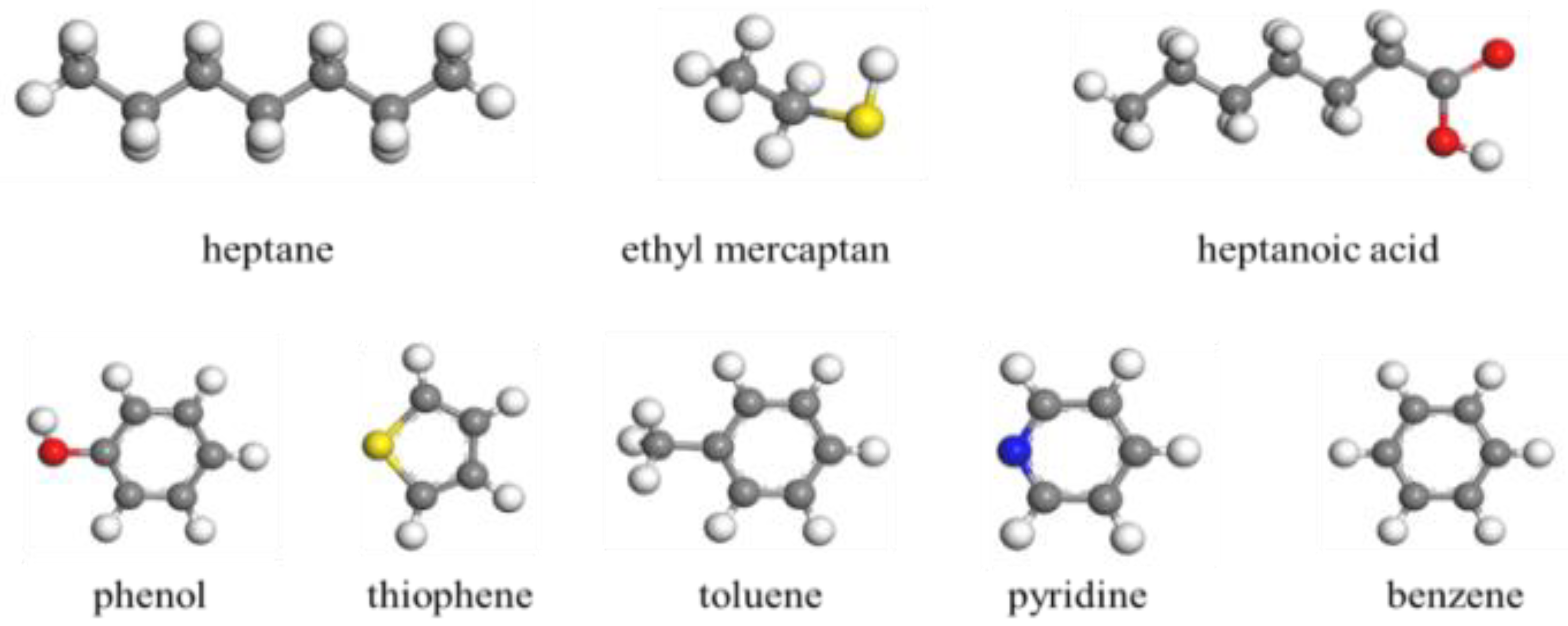

2. Simulation Details and Method

2.1. Force Field

2.2. Molecular Dynamic Simulation Programs

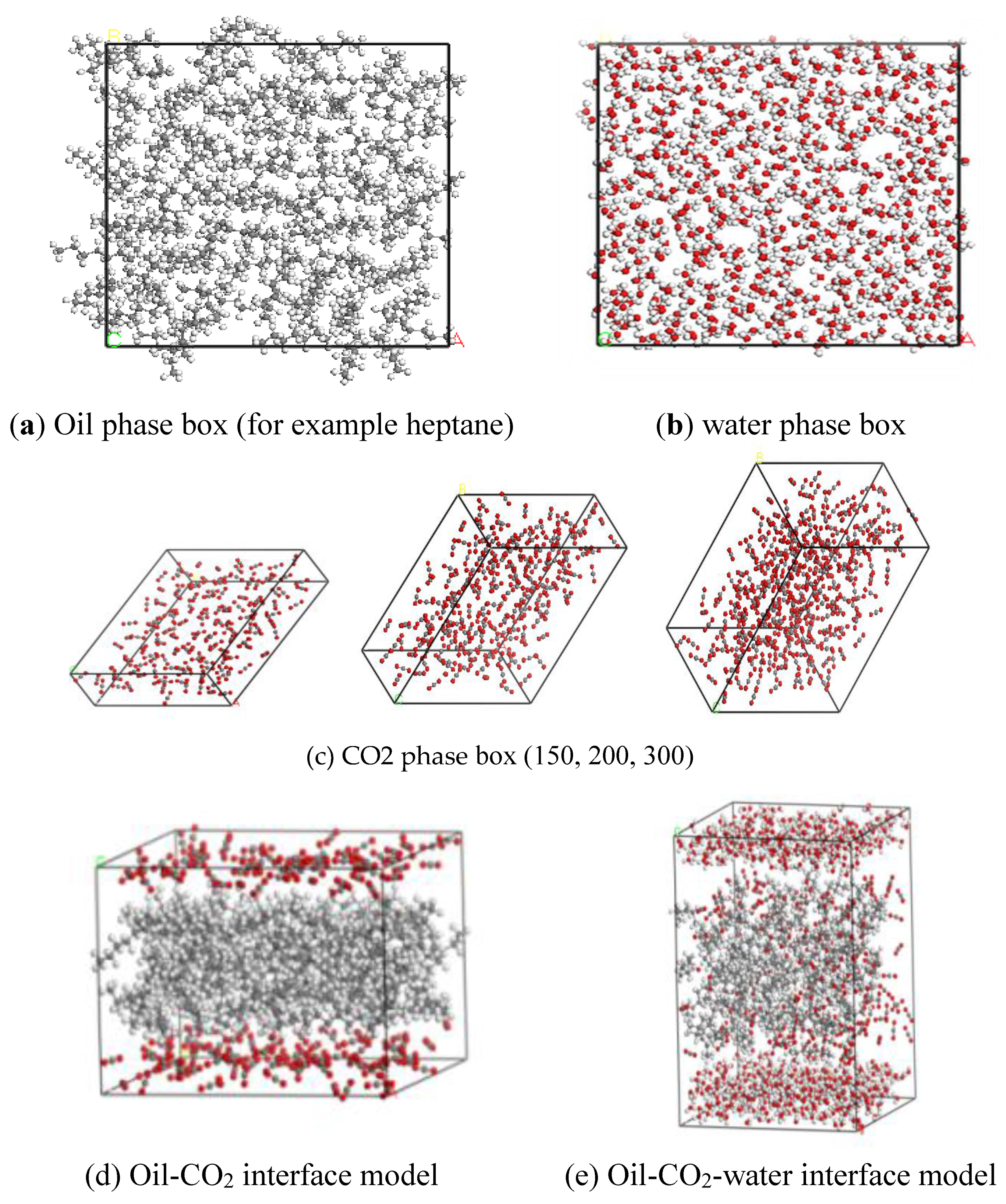

2.3. CO2-Water-Polar Molecule Interface Molecular Model

2.4. Simulation Details and Validation

2.4.1. Details

2.4.2. Validation

3. Findings and Evaluation

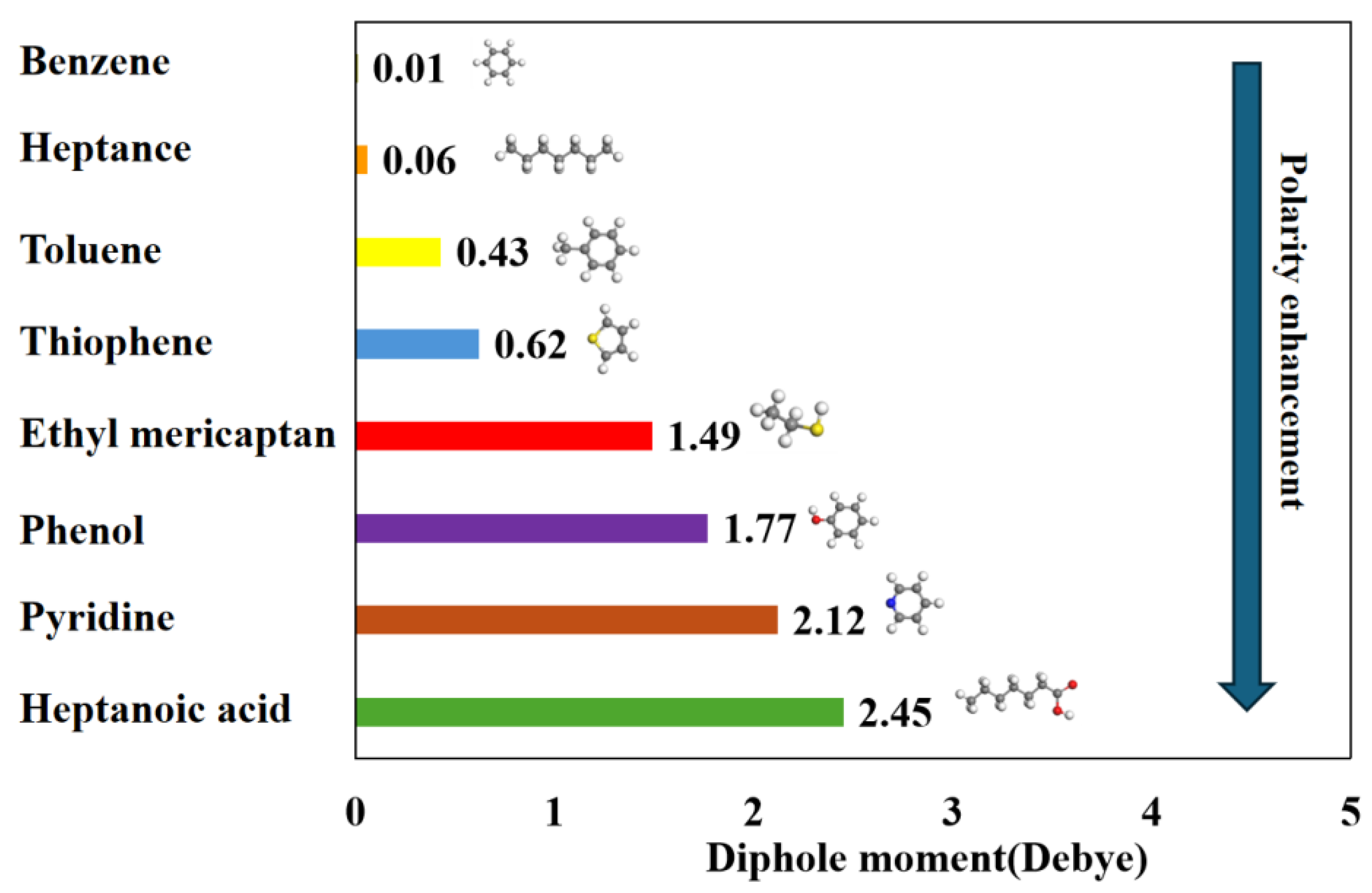

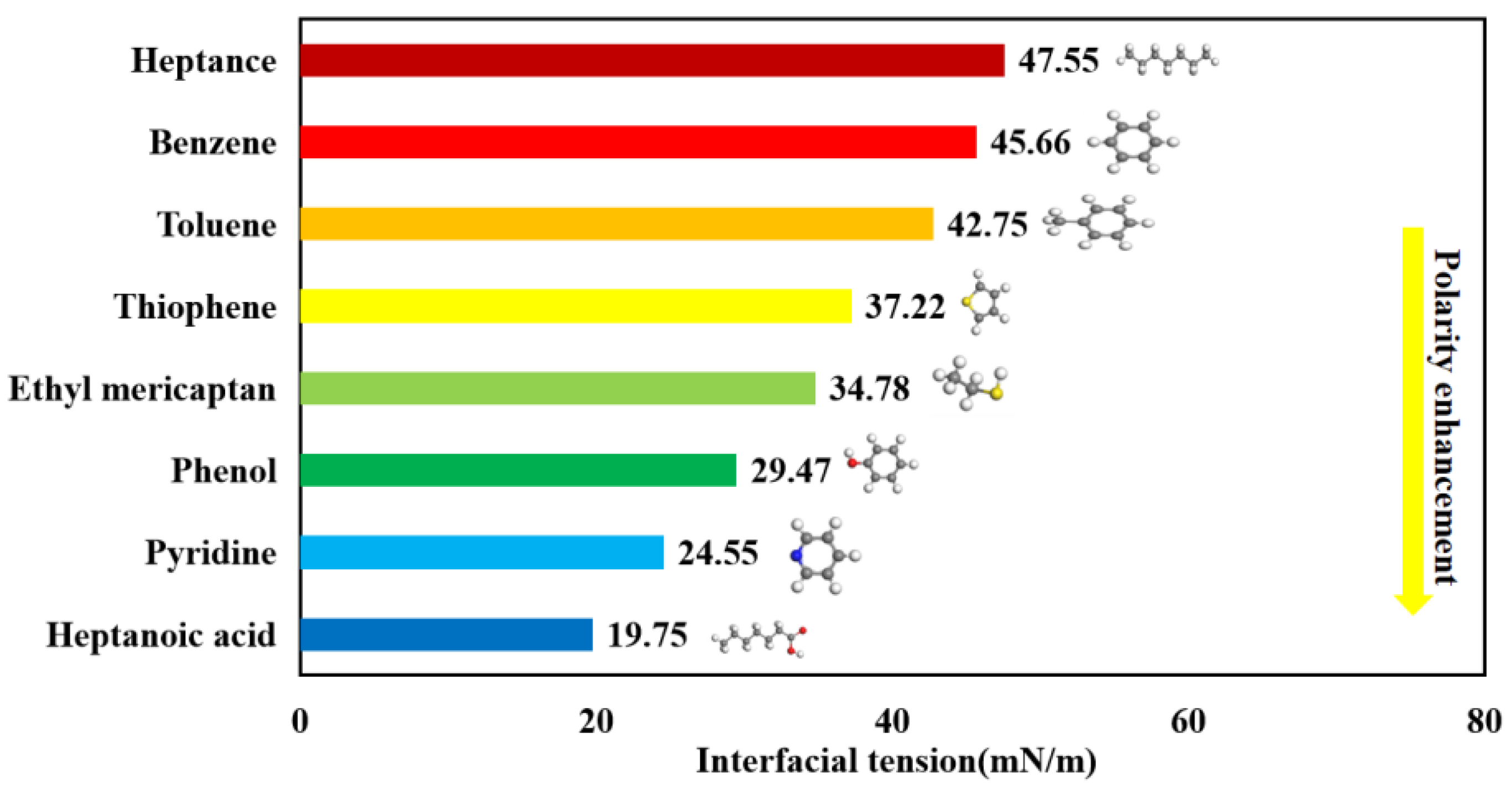

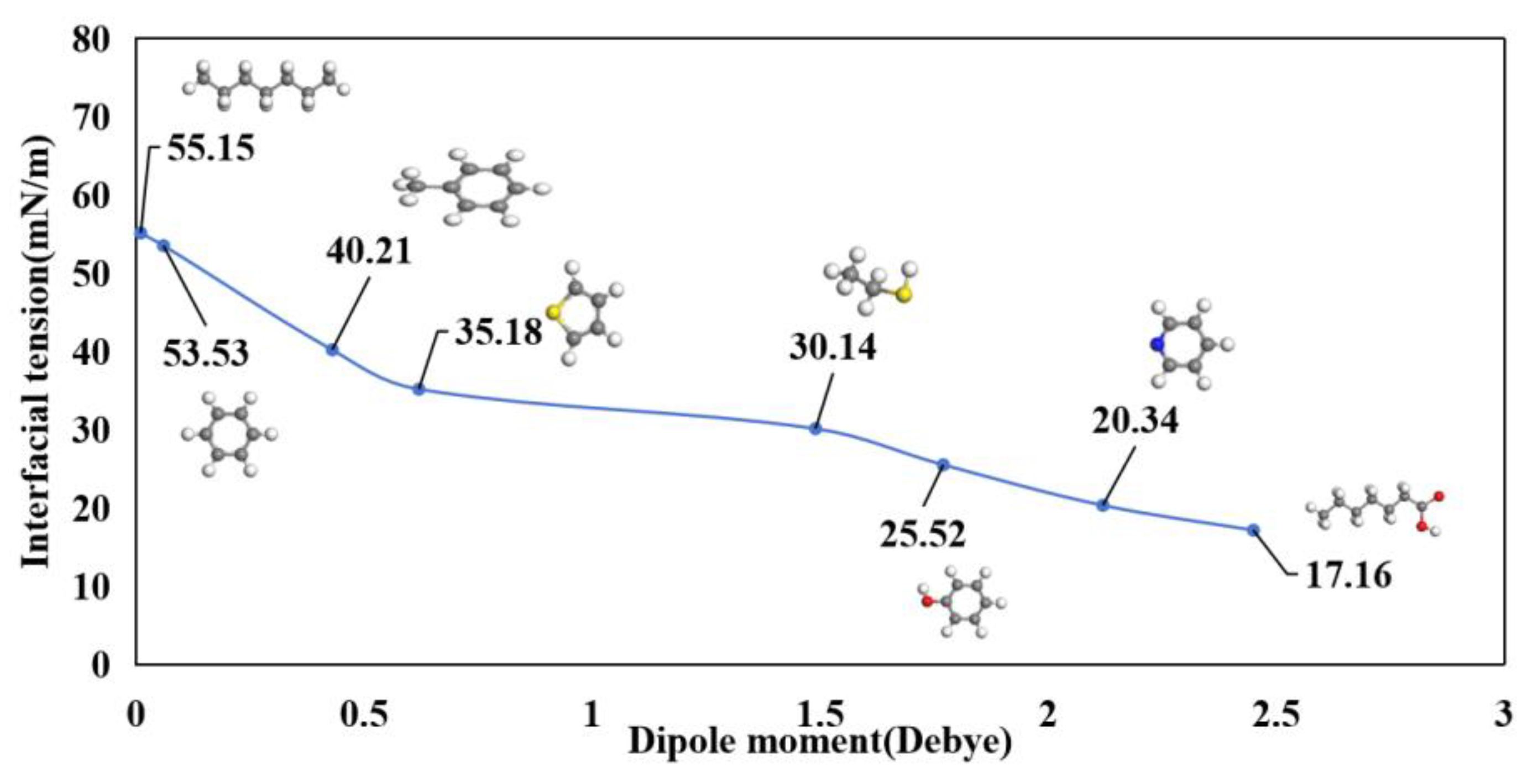

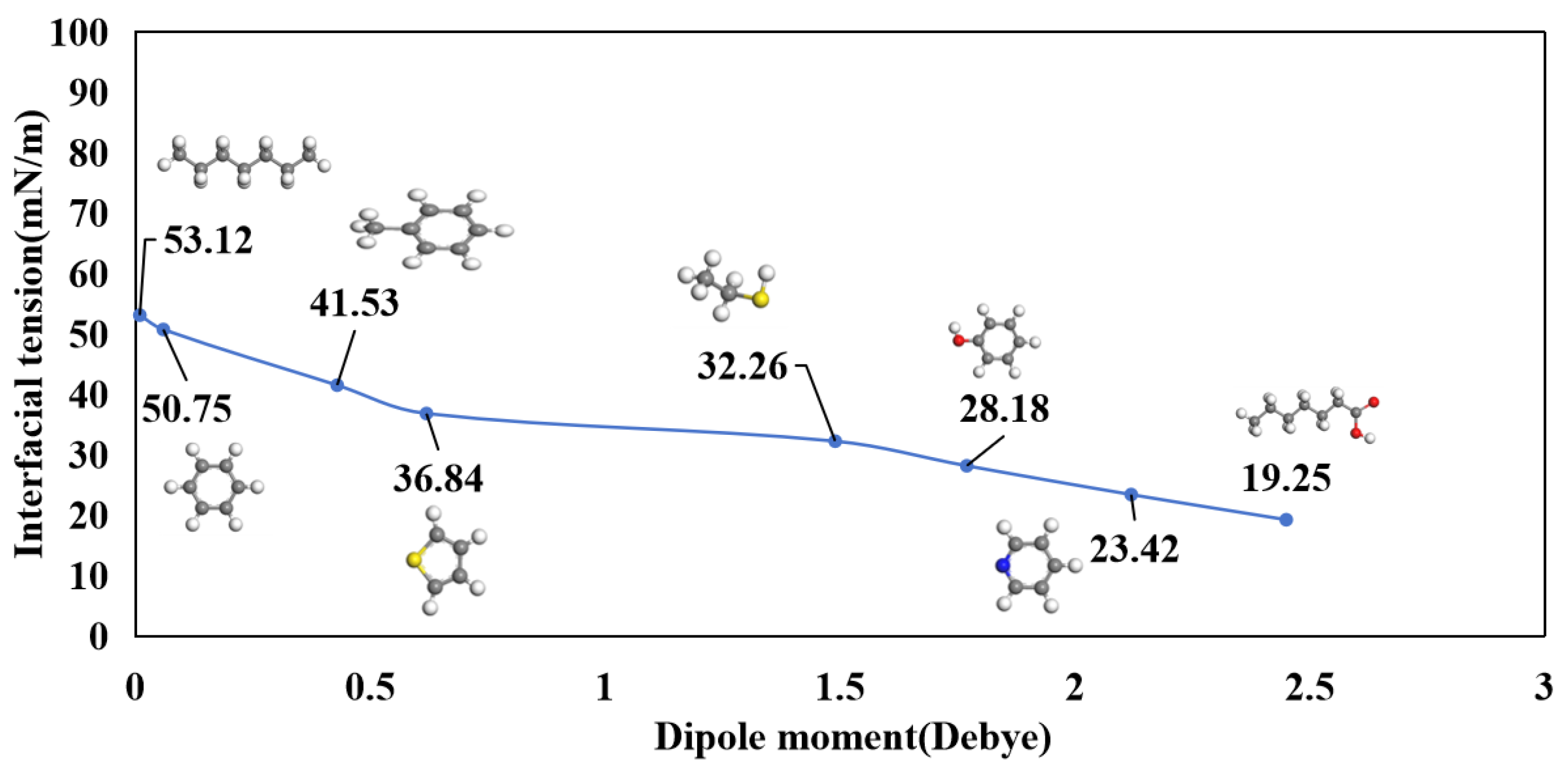

3.1. Molecular Polarity

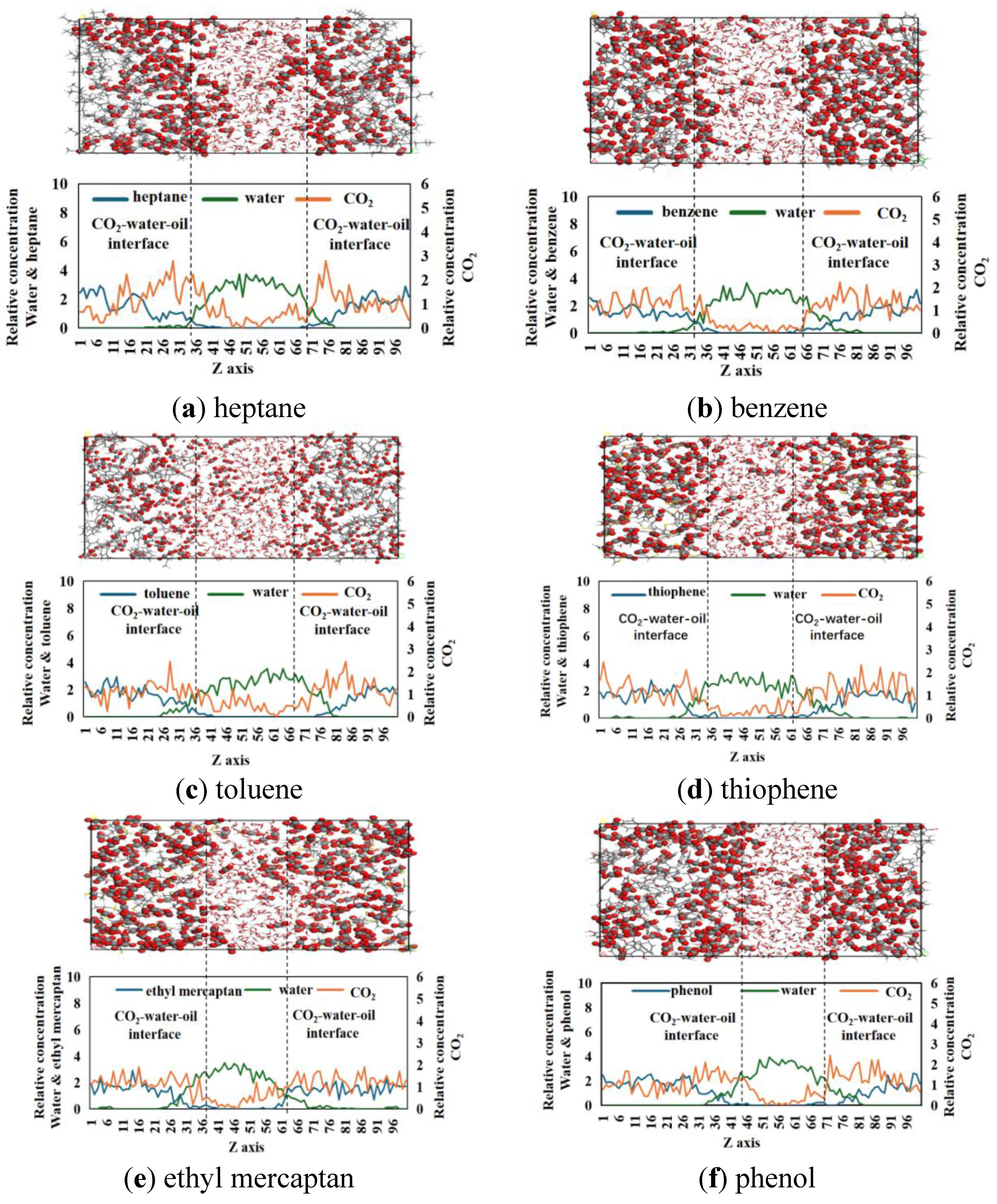

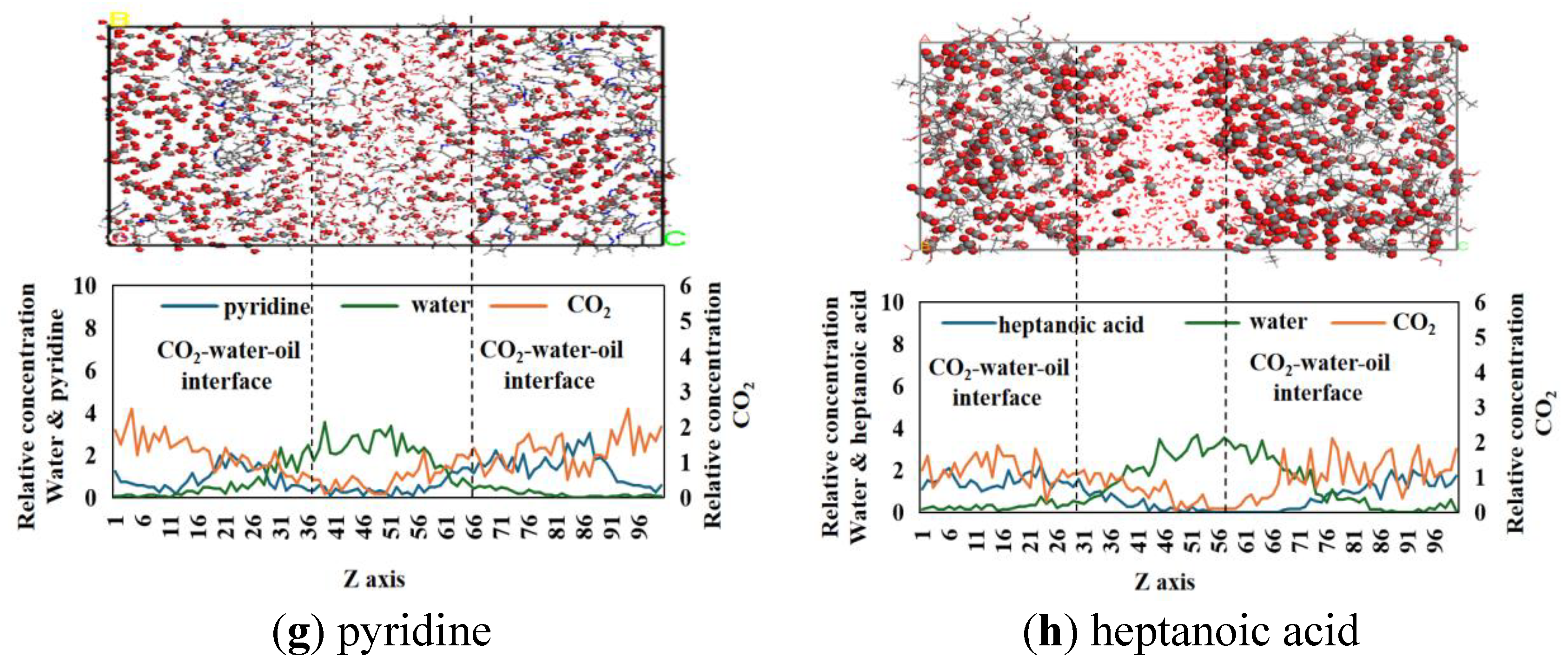

3.2. Relative Concentration and Molecular Configuration

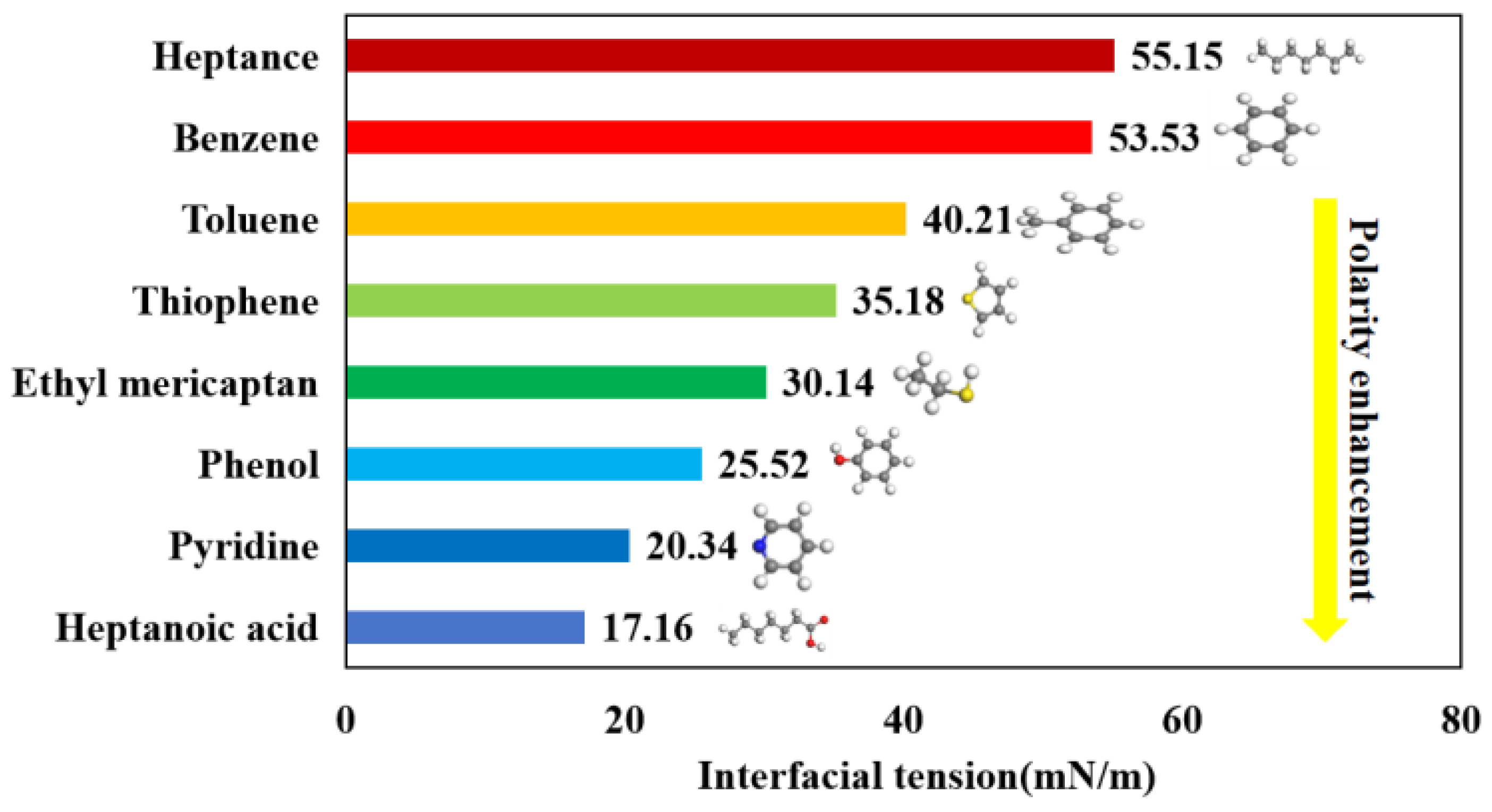

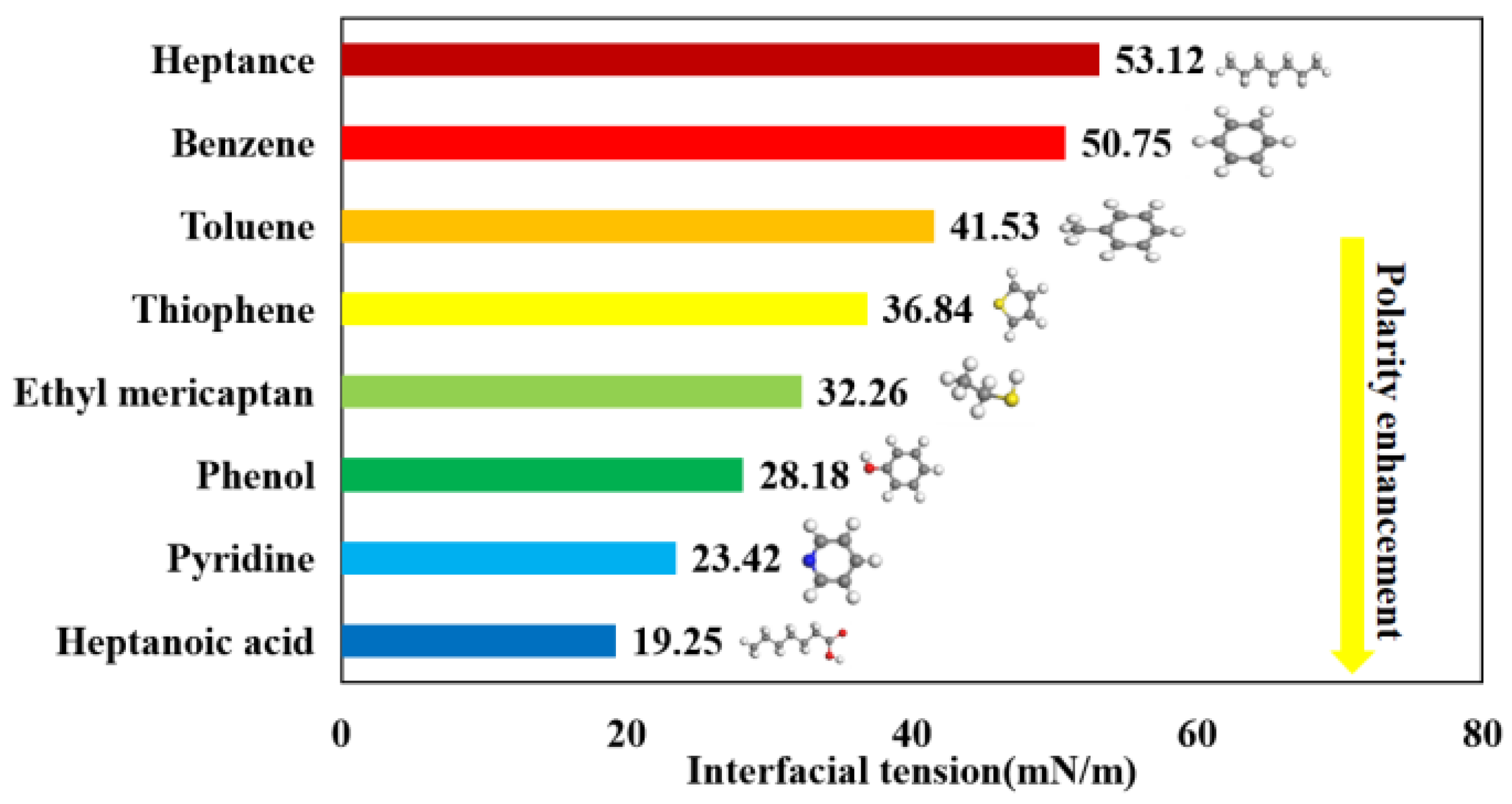

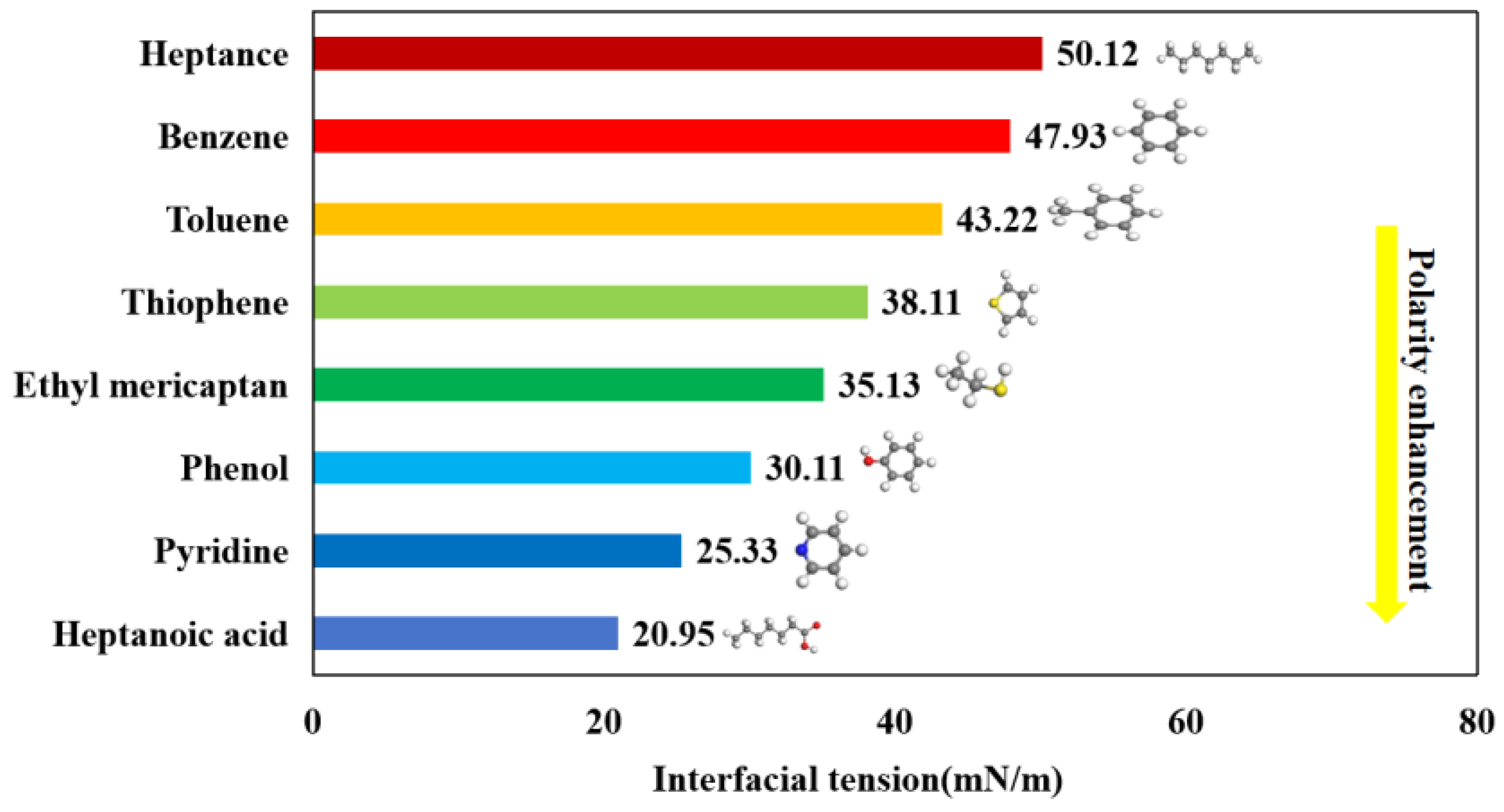

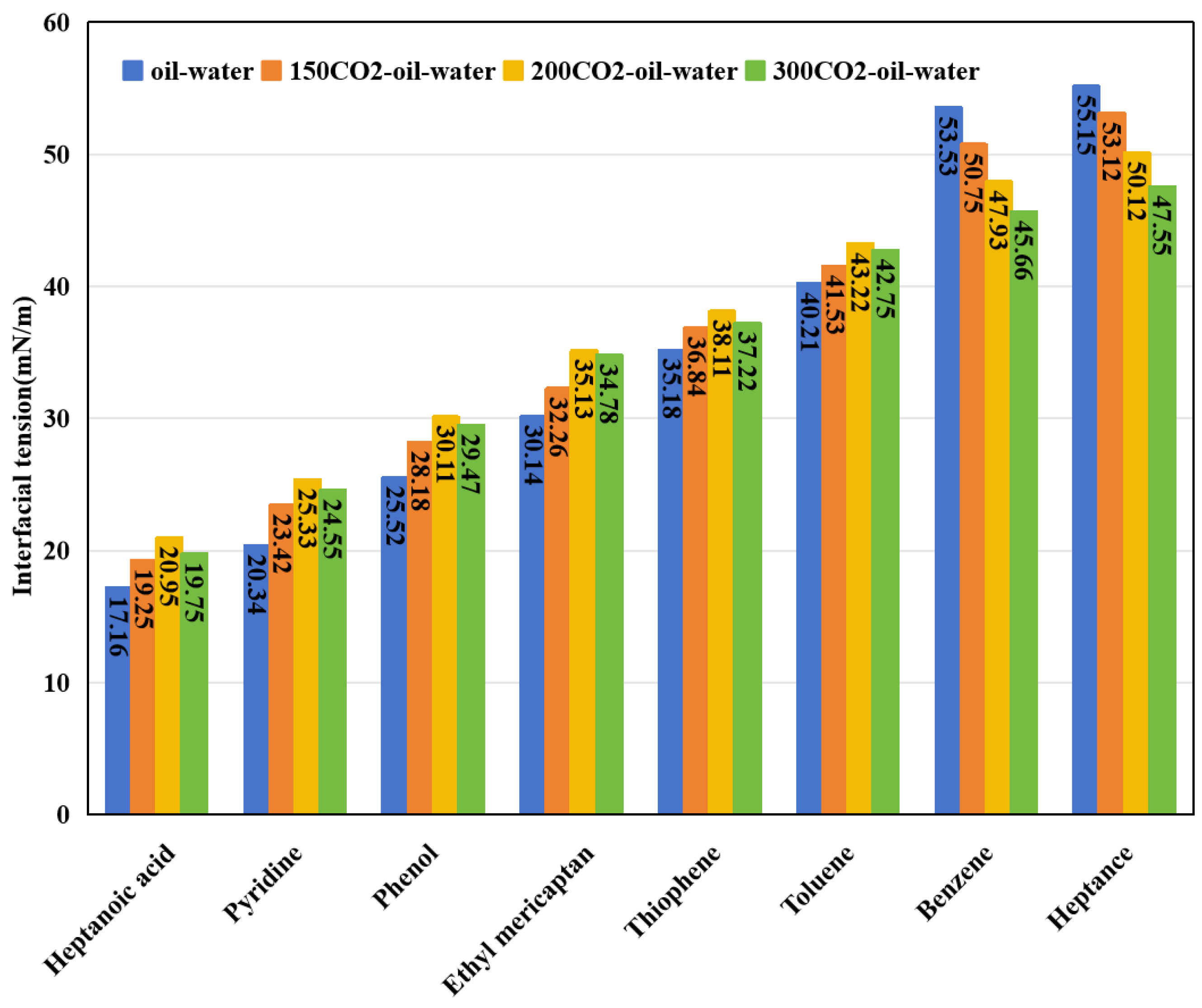

3.3. Interfacial Tension

3.4. Molecular Orientation at the Oil-Water Interface

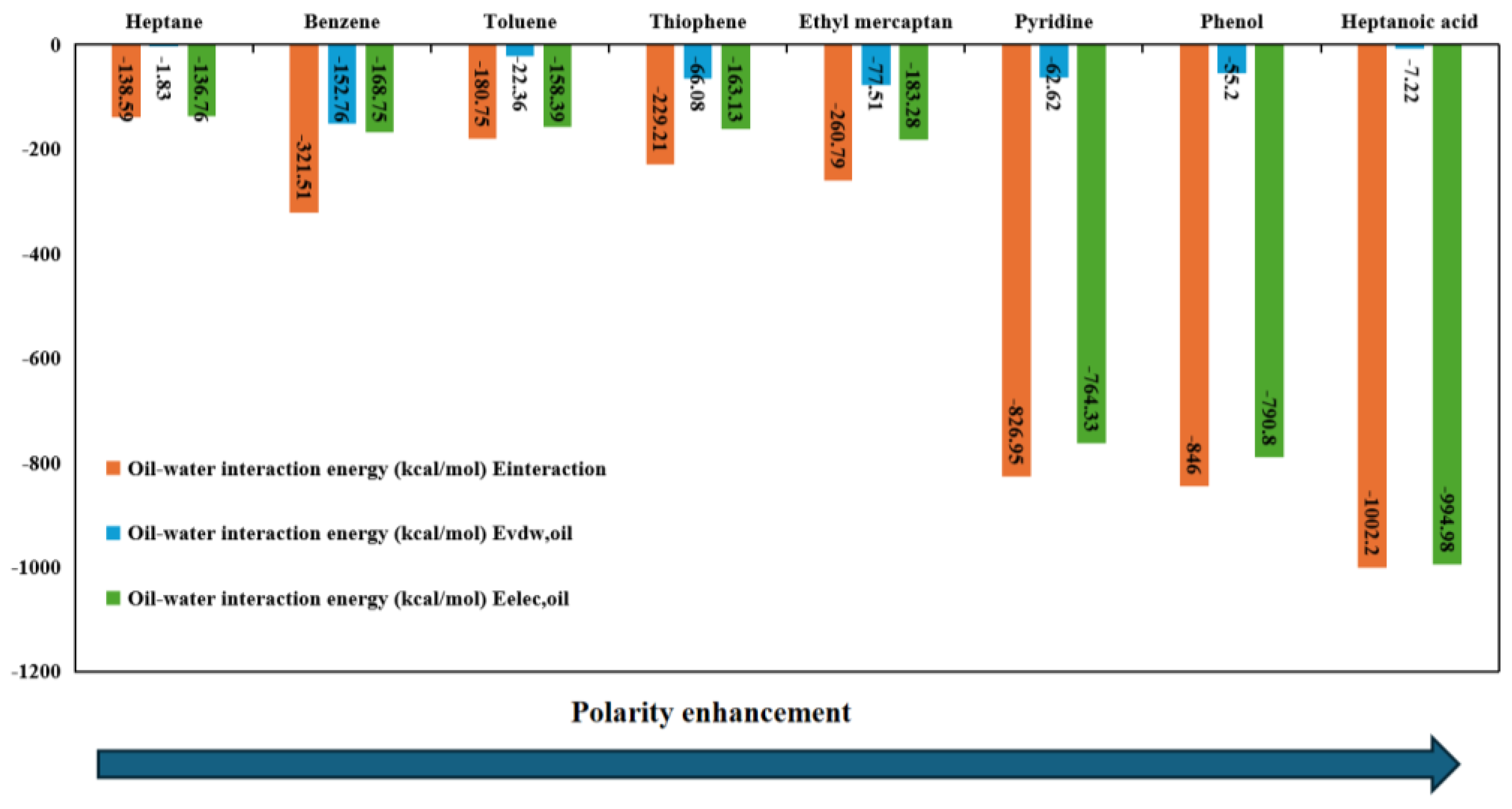

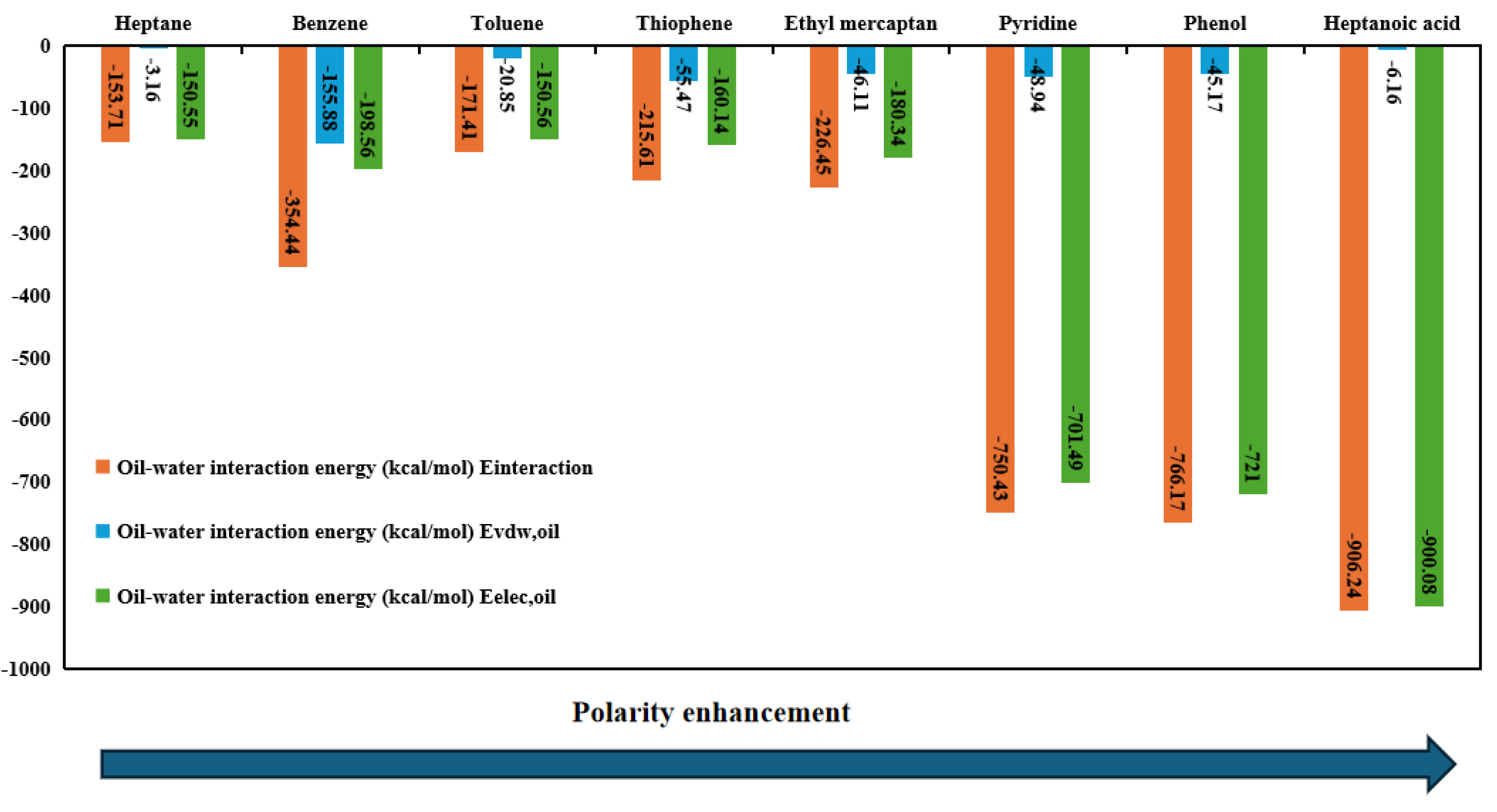

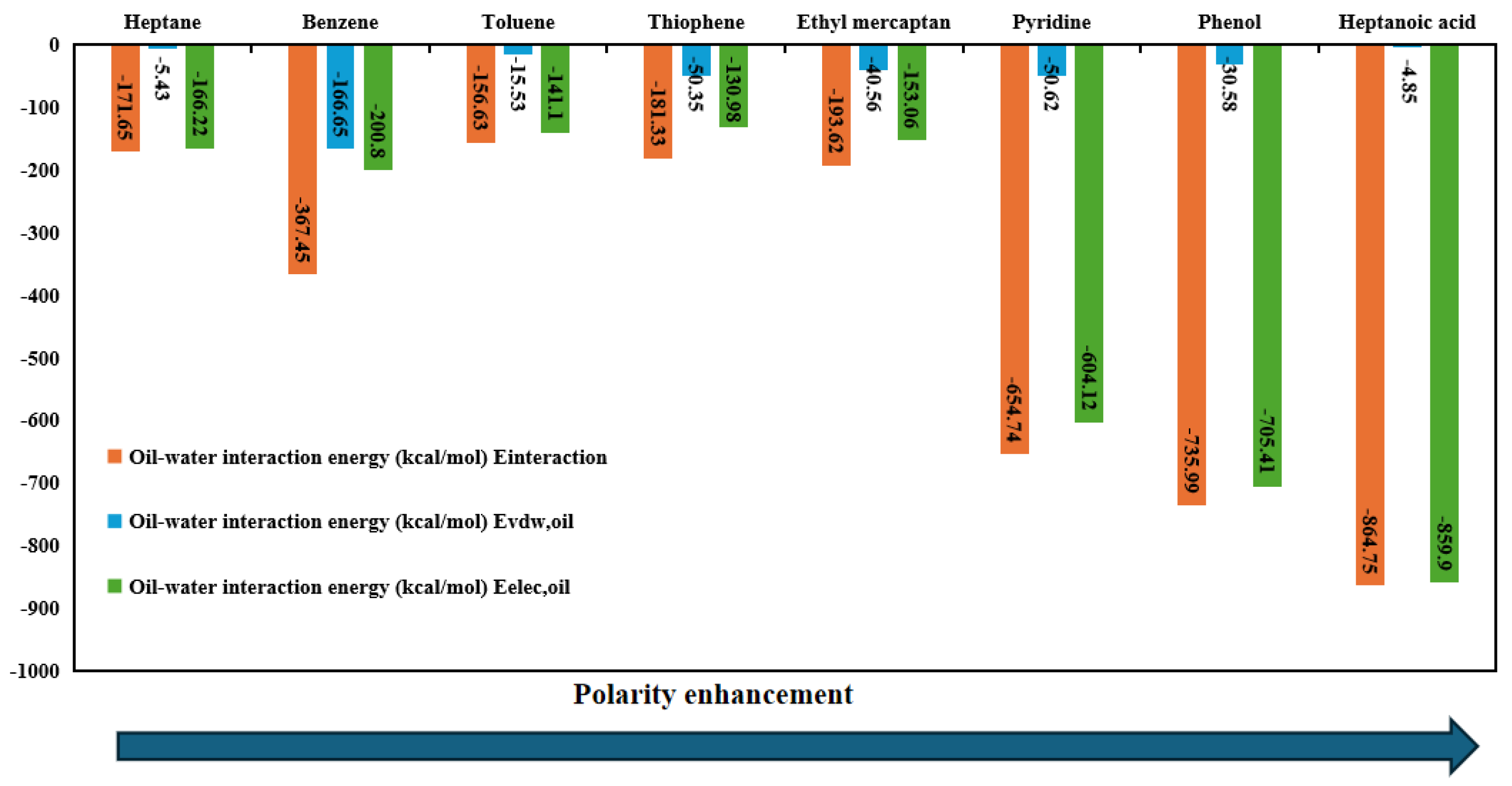

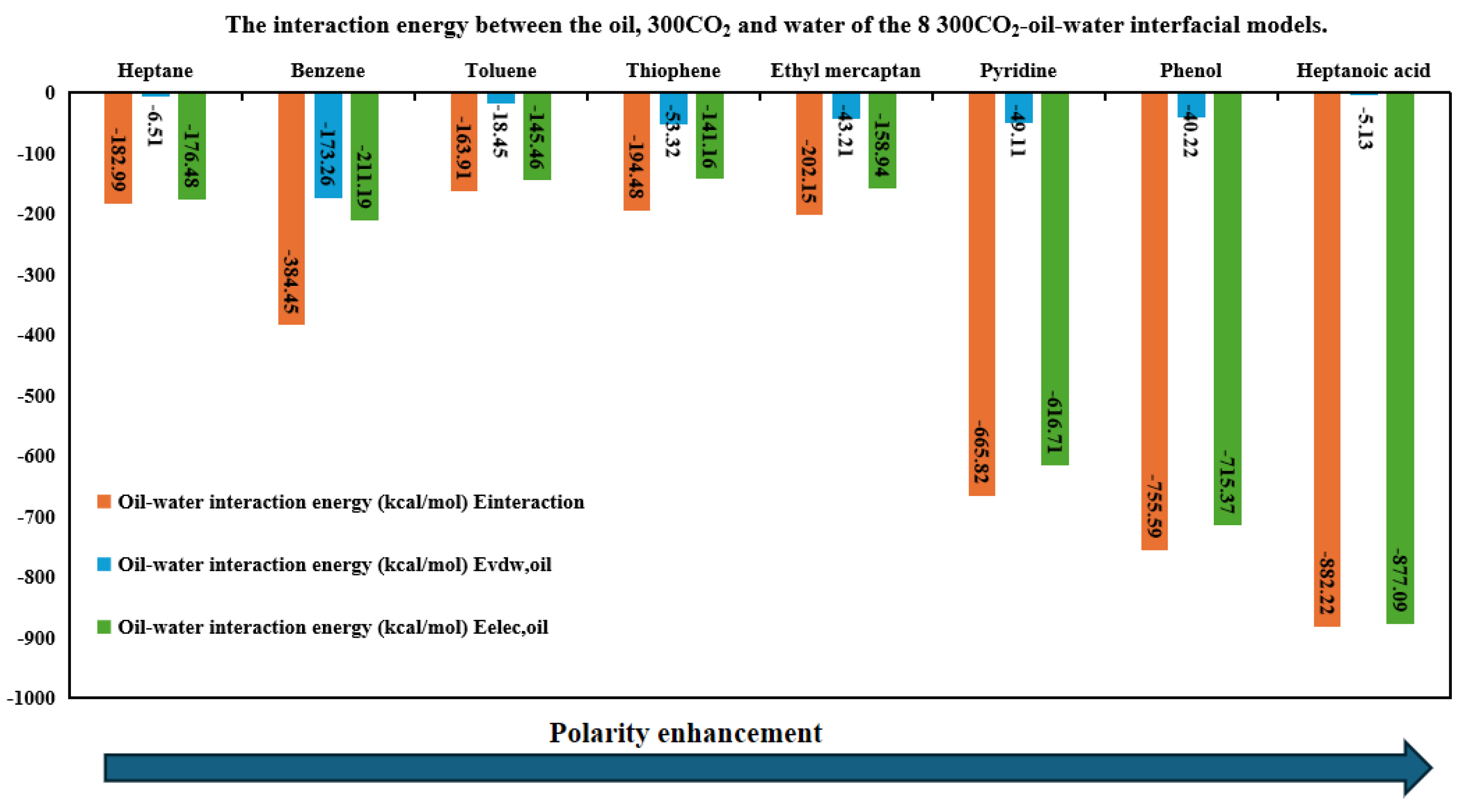

3.5. Interaction Energy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Case | Quantity and types of oil molecules | Water | CO2 | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonpolar molecules | Polar molecules | ||||||

| 1 | heptane | 80 | - | 0 | 600 | 0 | 680 |

| 2 | heptane | 80 | - | 0 | 600 | 150 | 830 |

| 3 | heptane | 80 | - | 0 | 600 | 200 | 880 |

| 4 | heptane | 80 | - | 0 | 600 | 300 | 980 |

| 5 | benzene | 100 | - | 0 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 6 | benzene | 100 | - | 0 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 7 | benzene | 100 | - | 0 | 600 | 200 | 900 |

| 8 | benzene | 100 | - | 0 | 600 | 300 | 1000 |

| 9 | - | 0 | Toluene | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 10 | - | 0 | Toluene | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 11 | - | 0 | Toluene | 100 | 600 | 200 | 900 |

| 12 | - | 0 | Toluene | 100 | 600 | 300 | 1000 |

| 13 | - | 0 | Thiophene | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 14 | - | 0 | Thiophene | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 15 | - | 0 | Thiophene | 100 | 600 | 200 | 900 |

| 16 | - | 0 | Thiophene | 100 | 600 | 300 | 1000 |

| 17 | - | 0 | heptanoic acid | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 18 | - | 0 | heptanoic acid | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 19 | - | 0 | heptanoic acid | 100 | 600 | 200 | 900 |

| 20 | - | 0 | heptanoic acid | 100 | 600 | 300 | 1000 |

| 21 | - | 0 | Pyridine | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 22 | - | 0 | Pyridine | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 23 | - | 0 | Pyridine | 100 | 600 | 200 | 900 |

| 24 | - | 0 | Pyridine | 100 | 600 | 300 | 1000 |

| 25 | - | 0 | Phenol | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 26 | - | 0 | Phenol | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 27 | - | 0 | Phenol | 100 | 600 | 200 | 900 |

| 28 | - | 0 | Phenol | 100 | 600 | 300 | 1000 |

| 29 | - | 0 | ethyl mercaptan | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 30 | - | 0 | ethyl mercaptan | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 31 | - | 0 | ethyl mercaptan | 100 | 600 | 200 | 900 |

| 32 | - | 0 | ethyl mercaptan | 100 | 600 | 300 | 1000 |

References

- Dahlia A. Al-Obaidi, Watheq J. Al-Mudhafar, Mohammed S. Al-Jawad. Experimental evaluation of Carbon Dioxide-Assisted Gravity Drainage process (CO2-AGD) to improve oil recovery in reservoirs with strong water drive. Fuel, Volume 324, Part A, 2022, 124409, ISSN 0016-2361. [CrossRef]

- Maryam Mohdsaeed H.I. Abdulla, Shaligram Pokharel. Analytical models for predicting oil recovery from immiscible CO2 injection: A literature review. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, Volume 219, 2022, 111131, ISSN 0920-4105. [CrossRef]

- Yongsheng Tan, Qi Li, Liang Xu, Abdul Ghaffar, Xiang Zhou, Pengchun Li. A critical review of carbon dioxide enhanced oil recovery in carbonate reservoirs. Fuel, Volume 328, 2022, 125256, ISSN 0016-2361. [CrossRef]

- Xiang Zhou, Qingwang Yuan, Xiaolong Peng, Fanhua Zeng, Liehui Zhang. A critical review of the CO2 huff ‘n’ puff process for enhanced heavy oil recovery, Fuel, Volume 215, 2018, Pages 813-824, ISSN 0016-2361. [CrossRef]

- Kun Guo, Hailong Li, Zhixin Yu. In-situ heavy and extra-heavy oil recovery: A review. Fuel, Volume 185, 2016, Pages 886-902, ISSN 0016-2361. [CrossRef]

- Randy Agra Pratama, Tayfun Babadagli. A review of the mechanics of heavy-oil recovery by steam injection with chemical additives. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, Volume 208, Part D, 2022, 109717, ISSN 0920-4105. [CrossRef]

- Yi Zhang, Lei Yuan, Shezhan Liu, Jingru Zhang, Mingjun Yang, Yongchen Song. Molecular dynamics simulation of bubble nucleation and growth during CO2 Huff-n-Puff process in a CO2-heavy oil system. Geoenergy Science and Engineering, Volume 227, 2023, 211852, ISSN 2949-8910. [CrossRef]

- Zihan Gu, Chao Zhang, Teng Lu, Haitao Wang, Zhaomin Li, Hongyuan Wang. Experimental analysis of the stimulation mechanism of CO2-assisted steam flooding in ultra-heavy oil reservoirs and its significance in carbon sequestration. Fuel, Volume 345, 2023, 128188, ISSN 0016-2361. [CrossRef]

- Di Zhu, Binfei Li, Lei Zheng, Wenshuo Lei, Boliang Li, Zhaomin Li. Effects of CO2 and surfactants on the interface characteristics and imbibition process in low-permeability heavy oil reservoirs. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, Volume 657, Part A, 2023, 130538, ISSN 0927-7757. [CrossRef]

- Xiang Zhou, Xiuluan Li, Dehuang Shen, Lanxiang Shi, Zhien Zhang, Xinge Sun, Qi Jiang. CO2 huff-n-puff process to enhance heavy oil recovery and CO2 storage: An integration study. Energy, Volume 239, Part B, 2022, 122003, ISSN 0360-5442. [CrossRef]

- Hao Chen, Bowen Li, et al. Empirical correlations for prediction of minimum miscible pressure and near-miscible pressure interval for oil and CO2 systems. Fuel, Volume 278, 2020, 118272, ISSN 0016-2361. [CrossRef]

- Timing Fang, Yingnan Zhang, Jie Liu, Bin Ding, Youguo Yan, Jun Zhang. Molecular insight into the miscible mechanism of CO2/C10 in bulk phase and nanoslits. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, Volume 141, 2019, Pages 643-650, ISSN 0017-9310. [CrossRef]

- Makimura Dai, Kunieda Makoto, Liang Yunfeng, Matsuoka Toshifumi, Takahashi Satoru, and Hiroshi Okabe. Application of Molecular Simulations to CO2-EOR: Phase-Equilibria and Interfacial Phenomena. Paper presented at the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, November 2011. [CrossRef]

- Seng, Lee Yeh, and Berna Hascakir. Role of Intermolecular Forces on Surfactant-Steam Performance into Heavy Oil Reservoirs. SPE J. 26 (2021): 2318–2323. [CrossRef]

- Qian-Hui Zhao, Shuai Ma, et al . Chung, Quan Shi. Molecular composition of naphthenic acids in a Chinese heavy crude oil and their impacts on oil viscosity. Petroleum Science, Volume 20, Issue 2, 2023, Pages 1225-1230, ISSN 1995-8226. [CrossRef]

- Chang-Yu Sun and Guang-Jin Chen. Measurement of Interfacial Tension for the CO2 Injected Crude Oil + Reservoir Water System. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 2005, 50 (3), 936-938. [CrossRef]

- Luo, C., Liu, H. Q., Wang, Z. C., Lyu, X. C., Zhang, Y. Q., & Zhou, S. (2024). A comprehensive study on the effect of rock corrosion and CO2 on oil-water interfacial tension during CO2 injection in heavy oil reservoirs. Petroleum Science and Technology, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Binfei Li, Lei Zheng, Aiqing Cao, Hao Bai, Chuanbao Zhang, Zhaomin Li. Effect of interaction between CO2 and crude oil on the evolution of interface characteristics. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, Volume 647, 2022, 129043, ISSN 0927-7757. [CrossRef]

- Bing Liu, Junqin Shi, et al. Reduction in interfacial tension of water–oil interface by supercritical CO2 in enhanced oil recovery processes studied with molecular dynamics simulation. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, Volume 111, 2016, Pages 171-178, ISSN 0896-8446. [CrossRef]

- Yilei Song, Zhaojie Song, Yufan Meng, Zhangxin Chen, Xiao Han, Dong Feng. Multi-phase behavior and pore-scale flow in medium-high maturity continental shale reservoirs with Oil, CO2, and water. Chemical Engineering Journal, Volume 484, 2024, 149679, ISSN 1385-8947. [CrossRef]

- Teng Lu, et al. Stability and enhanced oil recovery performance of CO2 in water emulsion: Experimental and molecular dynamic simulation study. Chemical Engineering Journal, Volume 464, 2023, 142636, ISSN 1385-8947. [CrossRef]

- Luan Yalin, et al. Oil displacement by supercritical CO2 in a water cut dead-end pore: Molecular dynamics simulation. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, Volume 188, 2020, 106899, ISSN 0920-4105. [CrossRef]

- Lu Wang, Yifan Zhang, Rui Zou, Run Zou, Liang Huang, Yisheng Liu, Zhan Meng, Zhilin Wang, Hao Lei. A systematic review of CO2 injection for enhanced oil recovery and carbon storage in shale reservoirs. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 48, Issue 95, 2023, Pages 37134-37165, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Tao Huang, Linsong Cheng, Renyi Cao, Xiaobiao Wang, Pin Jia, Chong Cao. Molecular simulation of the dynamic distribution of complex oil components in shale nanopores during CO2-EOR. Chemical Engineering Journal, Volume 479, 2024, 147743, ISSN 1385-8947. [CrossRef]

- Songqi Li, Yuetian Liu, Liang Xue, Dongdong Zhu. Theoretical insight into the effect of polar organic molecules on heptane-water interfacial properties using molecular dynamic simulation. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, Volume 212, 2022, 110259, ISSN 0920-4105. [CrossRef]

- Li Songqi, Yi Pan, Shuangchun Yang, Zhaoxuan Li. A molecular insight into the mechanism of organic molecule detachment by supercritical CO2 from a water invasion calcite surface: Effect of water film and molecular absorbability. Geoenergy Science and Engineering, Volume 231, Part A, 2023, 212290, ISSN 2949-8910. [CrossRef]

- Alqam, Mohammad H., Abu-Khamsin, Sidqi A., Alafnan, Saad F., Sultan, Abdullah S., Al-Majed, Abdulaziz, and Taha Okasha. The Impact of Carbonated Water on Wettability: Combined Experimental and Molecular Simulation Approach. SPE J. 27 (2022): 945–957. [CrossRef]

- Yafan Yang, Arun Kumar Narayanan Nair, Mohd Fuad Anwari Che Ruslan, and Shuyu Sun. Bulk and Interfacial Properties of the Decane Water System in the Presence of Methane, Carbon Dioxide, and Their Mixture. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2020, 124 (43), 9556-9569. [CrossRef]

- Tao Yu, Qi Li, et al. Characterization of the effects of wettability and pore pressure on the interfacial behavior of CO2 interacting with oil-water two-phase on pore walls. Geoenergy Science and Engineering, Volume 231, Part A, 2023, 212329, ISSN 2949-8910. [CrossRef]

- Chang Qiuhao, Huang Liangliang, and Xingru Wu. A Molecular Dynamics Study on Low-Pressure Carbon Dioxide in the Water/Oil Interface for Enhanced Oil Recovery. SPE J. 28 (2023): 643–652. [CrossRef]

- Saira, Ajoma, Emmanuel, and Furqan Le-Hussain. A Laboratory Investigation of the Effect of Ethanol-Treated Carbon Dioxide Injection on Oil Recovery and Carbon Dioxide Storage. SPE J. 26 (2021): 3119–3135. [CrossRef]

- Yueliang Liu, Zhenhua Rui, Tao Yang, Birol Dindoruk. Using propanol as an additive to CO2 for improving CO2 utilization and storage in oil reservoirs. Applied Energy, Volume 311, 2022, 118640, ISSN 0306-2619. [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I., Hefny, M., Abdel Maksoud, M.I.A. et al. Recent advances in carbon capture storage and utilization technologies: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 19, 797–849 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Zhao, et al., 2016. Compass II: extended coverage for polymer and drug-like molecule databases [J]. J. Mol. Model. [CrossRef]

- Songqi L, Yuetian L, et al. Theoretical insight into the effect of polar organic molecules on heptane-water interfacial properties using molecular dynamic simulation[J]. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 212, (2022). [CrossRef]

| Case | Quantity and types of oil molecules | Water | CO2 | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonpolar molecules | Polar molecules | ||||||

| 1 | heptane | 80 | - | 0 | 600 | 0 | 680 |

| 2 | heptane | 80 | - | 0 | 600 | 150 | 830 |

| 3 | benzene | 100 | - | 0 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 4 | benzene | 100 | - | 0 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 5 | - | 0 | Toluene | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 6 | - | 0 | Toluene | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 7 | - | 0 | Thiophene | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 8 | - | 0 | Thiophene | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 9 | - | 0 | heptanoic acid | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 10 | - | 0 | heptanoic acid | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 11 | - | 0 | Pyridine | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 12 | - | 0 | Pyridine | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 13 | - | 0 | Phenol | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 14 | - | 0 | Phenol | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| 15 | - | 0 | ethyl mercaptan | 100 | 600 | 0 | 700 |

| 16 | - | 0 | ethyl mercaptan | 100 | 600 | 150 | 850 |

| Model | Interfacial tension(mN/m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation | Experiment | Error | |

| hexane-water | 60.01 | 50.38 | 1% |

| heptane-water | 44.98 | 50.17 | -1% |

| decane-water | 60.05 | 51.10 | 2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).