Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Variable | Analysis | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Root mean square | F | p | η² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | Group | 27.85 | 1 | 27.850 | 9.800 | 0.004 | 0.125 |

| Residuals | 96.62 | 34 | 2.842 | ||||

| Depth 1mm | Group | 0.36 | 1 | 0.362 | 0.071 | 0.791 | 0.002 |

| Residuals | 172.50 | 34 | 5.073 | ||||

| Depth 3mm | Group | 0.47 | 1 | 0.468 | 0.107 | 0.745 | 0.003 |

| Residuals | 148.11 | 34 | 4.356 | ||||

| Depth 5mm | Group | 3.42 | 1 | 3.422 | 0.663 | 0.421 | 0.016 |

| Residuals | 175.46 | 34 | 5.161 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdulkarim, H. H. , Zeng, R., Pazdernik, V. K., & Davis, J. M. (2021). Effect of Bone Graft on the Correlation between Clinical Bone Quality and CBCT-determined Bone Density: A Pilot Study. Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, 22(7), 756–762. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N. , Gopalakrishna, V., Shetty, A., Nagraj, V., Imran, M., & Kumar, P. (2019). Efficacy of PRF vs PRF + biodegradable collagen plug in post-extraction preservation of socket. Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, 20(11), 1323–1328. [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A. A. , Murriky, A., & Shafik, S. (2017). Influence of platelet rich fibrin on post-extraction socket healing: A clinical and radiographic study. Saudi Dental Journal, 29(4), 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Anwandter, A. , Bohmann, S., Nally, M., Castro, A. B., Quirynen, M., & Pinto, N. (2016). Dimensional changes of the post extraction alveolar ridge, preserved with Leukocyte- and Platelet Rich Fibrin: A clinical pilot study. Journal of Dentistry, 52, 23–29. [CrossRef]

- Canellas, J. V. dos S., da Costa, R. C., Breves, R. C., de Oliveira, G. P., Figueredo, C. M. da S., Fischer, R. G., Thole, A. A., Medeiros, P. J. D. A., & Ritto, F. G. (2020a). Tomographic and histomorphometric evaluation of socket healing after tooth extraction using leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin: A randomized, single-blind, controlled clinical trial. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery, 48(1), 24–32. [CrossRef]

- Simon BI, Von Hagen S, Deasy MJ, Faldu M, Resnansky D. Changes in Alveolar Bone Height and Width Following Ridge Augmentation Using Bone Graft and Membranes. Journal of Periodontology. 2000 Nov 1;71(11):1774–91.

- Castaño-Granada, M. C. , Arismendi-Echavarria, J. A., Pérez-Cano, M. I., Gómez-Yali, A. J., & Sanchez-Gómez, S. (2023). Comparative tomographic and histological investigation of two biomaterials for preservation of the alveolar ridge. Uniciencia, 37(1). [CrossRef]

- Castro, A. B. , Van Dessel, J., Temmerman, A., Jacobs, R., & Quirynen, M. (2021). Effect of different platelet-rich fibrin matrices for ridge preservation in multiple tooth extractions: A split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 48(7), 984–995. [CrossRef]

- Choukroun, J. , & Ghanaati, S. (2018). Reduction of relative centrifugation force within injectable platelet-rich-fibrin (PRF) concentrates advances patients’ own inflammatory cells, platelets and growth factors: the first introduction to the low speed centrifugation concept. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, 44(1), 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. , Rajendran, Y., Paydar, S., Ho, S., Cox, D., Ryder, M., Dollard, J., & Kao, R. T. (2018). Advanced platelet-rich fibrin and freeze-dried bone allograft for ridge preservation: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Periodontology, 89(4), 379–387. [CrossRef]

- Dimofte, A.-M. , Agop Forna, D., Costan, V.-V., & Popescu, E. (n.d.). THE VALUE OF PLATELET RICH FIBRIN IN BONE REGENERATION FOLLOWING TOOTH EXTRACTION. In Romanian Journal of Oral Rehabilitation (Vol. 9, Issue 3).

- Dutta, S. , Passi, D., Singh, P., Sharma, S., Singh, M., & Srivastava, D. (2016). A randomized comparative prospective study of platelet-rich plasma, platelet-rich fibrin, and hydroxyapatite as a graft material for mandibular third molar extraction socket healing. National Journal of Maxillofacial Surgery, 7(1), 45. [CrossRef]

- Eelen, G., De Zeeuw, P., Treps, L., Harjes, U., Wong, B. W., & Carmeliet, P. (2018). ENDOTHELIAL CELL METABOLISM. Endothelial Cell Metabolism. Physiol Rev, 98, 3–58. [CrossRef]

- Fickl, S., Zuhr, O., Wachtel, H., Stappert, C. F. J., Stein, J. M., & Hürzeler, M. B. (2008). Dimensional changes of the alveolar ridge contour after different socket preservation techniques. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 35(10), 906–913. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N. , & Agarwal, S. (2021). Advanced–PRF: Clinical evaluation in impacted mandibular third molar sockets. Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 122(1), 43–49. [CrossRef]

- Gürbüzer, B. , Pikdöken, L., Tunali, M., Urhan, M., Küçükodaci, Z., & Ercan, F. (2010). Scintigraphic Evaluation of Osteoblastic Activity in Extraction Sockets Treated With Platelet-Rich Fibrin. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 68(5), 980–989. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán Castillo, G. F. , Paltas Miranda, M. E., Benenaula Bojorque, J. A., Núñez Barragán, K. I., & Simbaña García, D. V. (2017). Gingival and bone tissue healing in lower third molar surgeries. Comparative study between use of platelet rich fibrin versus physiological healing. Revista Odontológica Mexicana, 21(2), e112–e118. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, F. , Gaydarov, N., Badoud, I., Vazquez, L., Bernard, J. P., & Ammann, P. (2013). Clinical and histological evaluation of postextraction platelet-rich fibrin socket filling: A prospective randomized controlled study. Implant Dentistry, 22(3), 295–303. [CrossRef]

- He, L. , Lin, Y., Hu, X., Zhang, Y., & Wu, H. (2009). A comparative study of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on the effect of proliferation and differentiation of rat osteoblasts in vitro. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology, 108(5), 707–713. [CrossRef]

- Hoaglin, D. R. , & Lines, G. K. (2013). Prevention of localized osteitis in mandibular third-molar sites using platelet-rich fibrin. In International Journal of Dentistry (Vol. 2013). [CrossRef]

- Kapse, S. , Surana, S., Satish, M., Hussain, S. E., Vyas, S., & Thakur, D. (2019). Autologous platelet-rich fibrin: can it secure a better healing? Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology, 127(1), 8–18. [CrossRef]

- Kattimani, V. S. , Lingamaneni, K. P., Kreedapathi, G. E., & Kattappagari, K. K. (2019). Socket preservation using eggshell-derived nanohydroxyapatite with platelet-rich fibrin as a barrier membrane: A new technique. Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, 45(6), 332–342. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-G. (2014). Can Dental Cone Beam Computed Tomography Assess Bone Mineral Density? Journal of Bone Metabolism, 21(2), 117. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y. R. , Mohanty, S., Verma, M., Kaur, R. R., Bhatia, P., Kumar, V. R., & Chaudhary, Z. (2016). Platelet-rich fibrin: The benefits. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 54(1), 57–61. [CrossRef]

- Mazor, Z. , Horowitz, R., Prasad, H., & Kotsakis, G. (2019). Healing Dynamics Following Alveolar Ridge Preservation with Autologous Tooth Structure. The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry, 39(5), 697–702. [CrossRef]

- Nemtoi, A. , Sirghe, A., Nemtoi, A., & Haba, D. (2018). The Effect of a Plasma With Platelet-rich Fibrin in Bone Regeneration and on Rate of Orthodontic Tooth Movement in Adolescents. In REV.CHIM.(Bucharest)♦ (Vol. 69, Issue 12). 372. Available online: http://www.revistadechimie.ro3727.

- Niedzielska, I. , Ciapiński, D., Bak, M., & Niedzielski, D. (2022). The Assessment of the Usefulness of Platelet-Rich Fibrin in the Healing Process Bone Resorption. Coatings, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- of Oral, P. , & Radiology, M. (2017). In vitro Evaluation of the Relationship between Gray Scales in Digital Intraoral Radiographs and Hounsfield Units in CT Scans. In J Biomed Phys Eng (Vol. 7, Issue 3). www.jbpe.

- Peck, M. T. , Marnewick, J., & Stephen, L. (2011). Alveolar Ridge Preservation Using Leukocyte and Platelet-Rich Fibrin: A Report of a Case. Case Reports in Dentistry, 2011, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Pohl, S. , Binderman, I., & Tomac, J. (2020a). Maintenance of alveolar ridge dimensions utilizing an extracted tooth dentin particulate autograft and platelet-rich fibrin: A retrospective radiographic cone-beam computed tomography study. Materials, 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, J. , Vangansewinkel, T., Gervois, P., Merckx, G., Hilkens, P., Quirynen, M., Lambrichts, I., & Bronckaers, A. (2018). Angiogenic Properties of ‘Leukocyte- and Platelet-Rich Fibrin.’ Scientific Reports, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Revathy, Ns. , Kannan, R., Karthik, R., Kumar, M. S., Munshi, M. I., & Vijay, R. (2018). Comparative study on alveolar bone healing in postextraction socket versus healing aided with autologous platelet-rich fibrin following surgical removal of bilateral mandibular impacted third molar tooth: A radiographic evaluation. National Journal of Maxillofacial Surgery, 9(2), 140. [CrossRef]

- Shiezadeh, F. , Taher, M., Shooshtari, Z., Arab, H. R., & Shafieian, R. (2023). Using Platelet-Rich Fibrin in Combination With Allograft Bone Particles Can Induce Bone Formation in Maxillary Sinus Augmentation. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 81(7), 904–912. [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, B. , Das, P., Rana, M. M., Qureshi, A. Q., Vaidya, K. C., & Raziuddin, S. J. A. (2018c). Wound healing and bone regeneration in postextraction sockets with and without platelet-rich fibrin. Annals of Maxillofacial Surgery, 8(1), 28–34. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, F. J. , Nasirzade, J., Kargarpoor, Z., Stähli, A., & Gruber, R. (2020). Effect of platelet-rich fibrin on cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, inflammation, and osteoclastogenesis: a systematic review of in vitro studies. In Clinical Oral Investigations (Vol. 24, Issue 2, pp. 569–584). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Suttapreyasri, S. , & Leepong, N. (2013). Influence of platelet-rich fibrin on alveolar ridge preservation. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 24(4), 1088–1094. [CrossRef]

- Temmerman, A. , Vandessel, J., Castro, A., Jacobs, R., Teughels, W., Pinto, N., & Quirynen, M. (2016). The use of leucocyte and platelet-rich fibrin in socket management and ridge preservation: a split-mouth, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 43(11), 990–999. [CrossRef]

- Ucer, C. , & Khan, R. S. (2023). Extraction Socket Augmentation with Autologous Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF): The Rationale for Socket Augmentation. In Dentistry Journal (Vol. 11, Issue 8). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y. , Xu, B., Yang, J., & Wu, M. (2024). Effects of platelet-rich fibrin on post-extraction wound healing and wound pain: A meta-analysis. International Wound Journal, 21(2). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Ruan, Z., Shen, M., Tan, L., Huang, W., Wang, L., & Huang, Y. (2018). Clinical effect of platelet-rich fibrin on the preservation of the alveolar ridge following tooth extraction. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 15(3), 2277–2286. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Time | Group | N | M | DE | CV | Averages | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dif | IC (95%) | |||||||||

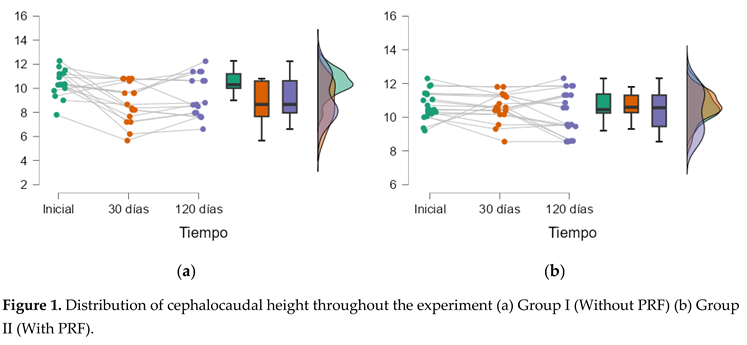

| Height | Initial | Group I | 17 | 10,45 | 1,10 | 0,11 | -0.28 | ICI= -0.324 ICS= 0.382 | -0.853 | 0.399 |

| Group II | 19 | 10,72 | 0,84 | 0,08 | ||||||

| 30 days | Group I | 17 | 8,82 | 1,68 | 0,19 | -1.79 | ICI= -2.674 ICS= -0.901 |

-4.099 | < .001 | |

| Group II | 19 | 10,61 | 0,85 | 0,08 | ||||||

| 120 days | Group I | 17 | 9,31 | 1,73 | 0,19 | -0.99 | ICI= -2.015ICS= 0.040 | -1.953 | 0.059 | |

| Group II | 19 | 10,30 | 1,29 | 0,13 | ||||||

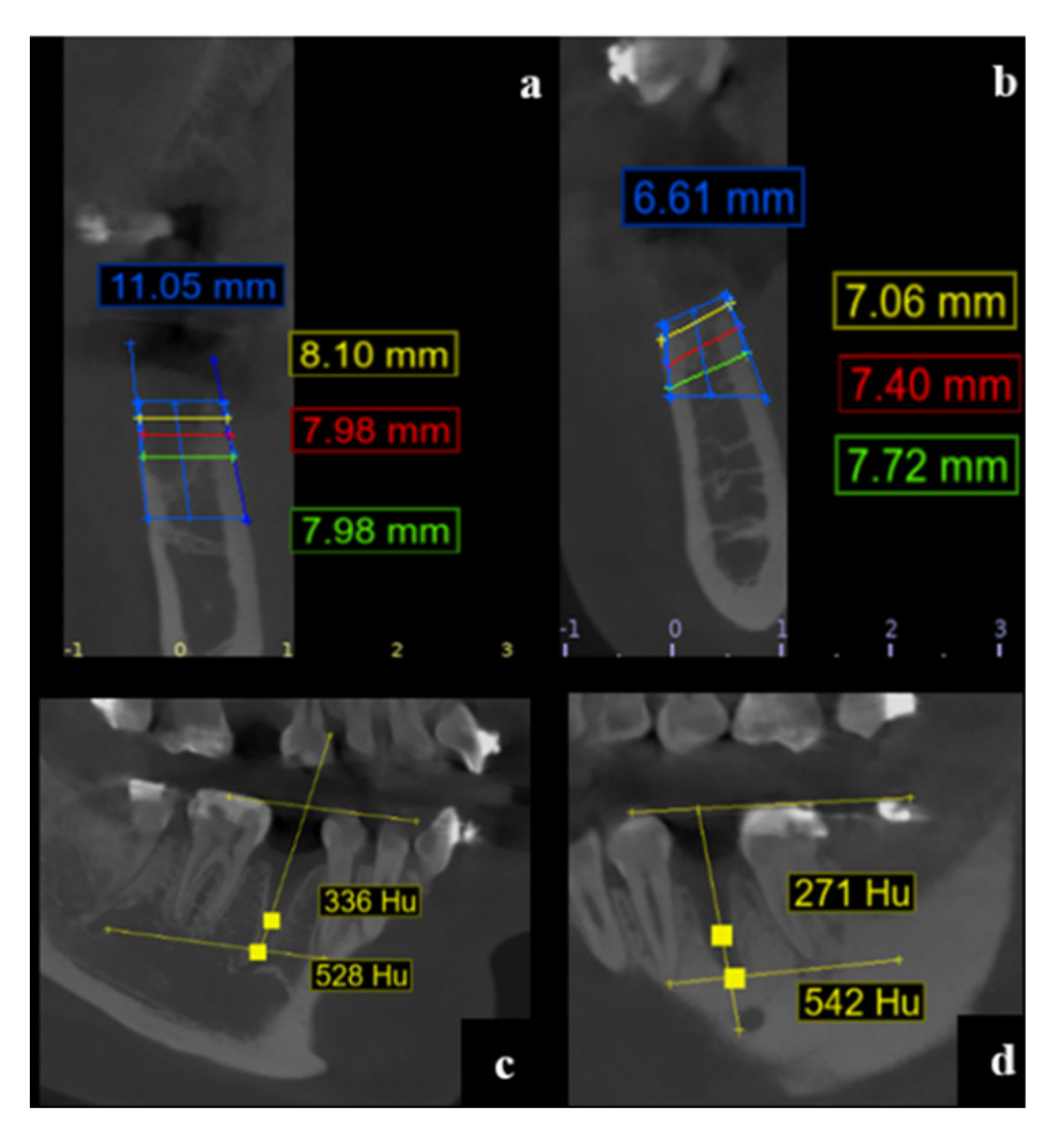

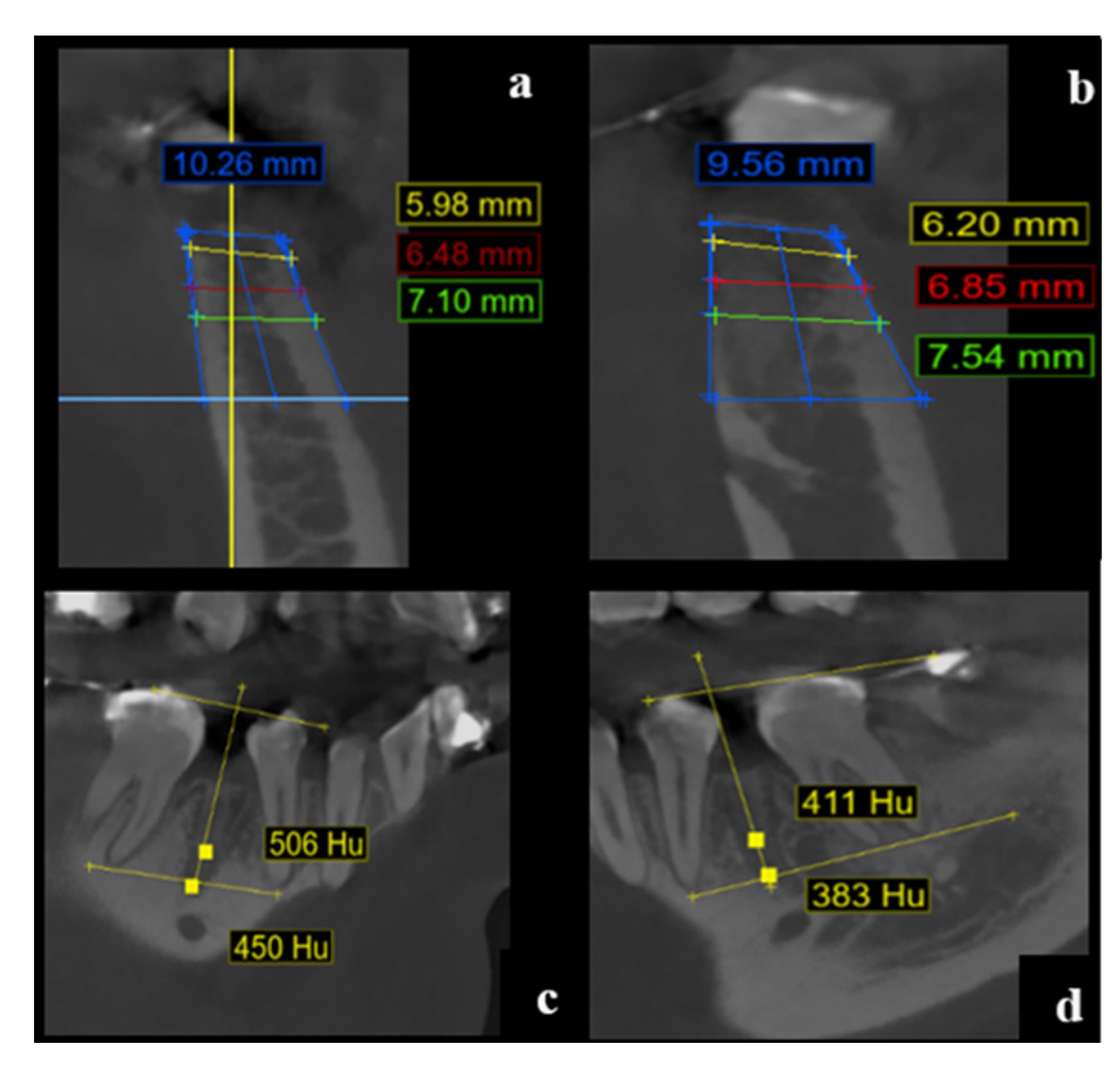

| Depth 1mm | 30 days | Group I | 17 | 8,40 | 1,84 | 0,22 | -0.63 | ICI= -1.705 ICS= 0.453 | -1.179 | 0.247 |

| Group II | 19 | 9,02 | 1,33 | 0,15 | ||||||

| 120 days | Group I | 17 | 8,40 | 1,92 | 0,23 | 0.34 | ICI= -0.912 ICS= 1.596 | 0.554 | 0.583 | |

| Group II | 19 | 8,06 | 1,78 | 0,22 | ||||||

| Depth 3mm | 30 days | Group I | 17 | 8,76 | 1,69 | 0,19 | -0.62 | ICI= -1.626 ICS= 0.385 | -1.254 | 0.218 |

| Group II | 19 | 9,38 | 1,27 | 0,14 | ||||||

| 120 days | Group I | 17 | 9,39 | 1,69 | 0,18 | 0.94 | ICI= -0.195 ICS= 2.082 | 1.684 | 0.101 | |

| Group II | 19 | 8,45 | 1,67 | 0,20 | ||||||

| Depth 5mm | 30 days | Group I | 17 | 9,19 | 1,78 | 0,19 | -0.07 | ICI= -1.174 ICS= 1.029 |

-0.133 | 0.895 |

| Group II | 19 | 9,26 | 1,47 | 0,16 | ||||||

| 120 days | Group I | 17 | 9,99 | 1,93 | 0,19 | 0.95 | ICI= -0.266 ICS= 2.157 | 1.586 | 0.122 | |

| Group II | 19 | 9,04 | 1,65 | 0,18 | ||||||

| Variable | Analysis | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Root mean square | F | p | η² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | Time | 16.45 | 2 | 8.224 | 7.840 | < .001 | 0.074 |

| Time ✻ Group | 10.26 | 2 | 5.132 | 4.892 | 0.010 | 0.046 | |

| Residuals | 71.33 | 68 | 1.049 | ||||

| Depth 1mm | Time | 4.21 | 1 | 4.212 | 4.840 | 0.035 | 0.020 |

| Time ✻ Group | 4.20 | 1 | 4.202 | 4.828 | 0.035 | 0.020 | |

| Residuals | 29.59 | 34 | 0.870 | ||||

| Depth 3mm | Time | 0.41 | 1 | 0.412 | 0.627 | 0.434 | 0.002 |

| Time ✻ Group | 10.98 | 1 | 10.977 | 16.693 | < .001 | 0.060 | |

| Residuals | 22.36 | 34 | 0.658 | ||||

| Depth 5mm | Time | 1.52 | 1 | 1.520 | 2.284 | 0.140 | 0.007 |

| Time ✻ Group | 4.65 | 1 | 4.648 | 6.985 | 0.012 | 0.022 | |

| Residuals | 22.63 | 34 | 0.665 |

| Group | Variable | Measurement 1 | Measurement 2 | Difroot mean square | W | z | p | IC root mean square differences (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | Height | Start | 30 days | -1,626 | 13.65 | 2.840 | 0.005 | ICI= 0.550 ICS=2.610 |

| 30 days | 120 days | 0,491 | 4.30 | -1.586 | 0.118 | ICI= -1.100 ICS= 0.090 |

||

| Depth | 30 days (1 mm) |

120 days (1 mm) |

0,000 | 6.80 | -0.402 | 0.705 | ICI= -0.755 ICS=0.755 | |

| 30 days (3 mm) |

120 days (3 mm) |

-0,630 | 2.70 | -2.343 | 0.020 | ICI= -1.280ICS=-0.090 | ||

| 30 days (5 mm) |

120 days (5 mm) |

0,800 | 2.10 | -2.627 | 0.009 | ICI= -1.355ICS=-0.465 | ||

| Group II | Height | Start | 30 days | -0,115 | 15.40 | 2.374 | 0.019 | ICI=0.055 ICS= 0.435 |

| 30 days | 120 days | -0,310 | 9.20 | 0.734 | 0.477 | ICI= -0.300 ICS=0.970 | ||

| Depth | 30 days (1 mm) |

120 days (1 mm) |

-0,968 | 16.20 | 2.696 | 0.007 | ICI=0.190 ICS=1.560 | |

| 30 days (3 mm) |

120 days (3 mm) |

-0,933 | 16.70 | 2.897 | 0.004 | ICI=0.340 ICS=1.420 | ||

| 30 days (5 mm) |

120 days (5 mm) |

-0,218 | 9.90 | 0.161 | 0.888 | ICI= -0.480 ICS=0.900 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).