1. Introduction

The orbit is a relatively rigid bone construct with limited adaptability to changes in orbital cavity pressure and, therefore, a high risk of orbital compartment syndrome (OCS) with subsequent optic nerve ischemia. OCS was first described in 1950 by Gordan and McCrae [

1]. Swelling or bleeding behind the eyeball (bulbus oculi) may result in impaired vision, proptosis, diplopia, and ocular motility. Visual loss, specifically blindness (amaurosis), is a severe complication of OCS resulting from persistent ischemia of the optic nerve [

2].

Retrobulbar hemorrhage (RBH) secondary to orbito-facial trauma is a relatively rare but severe pattern that may lead to an orbital compartment syndrome. The risk of RBH in facial trauma with or without bone fractures is less than 1%[

3]. Iatrogenic ophthalmic surgery and non-ophthalmic procedures (such as sinus surgery and craniofacial surgery) are well reported as a cause of RBH [

4]. There is a wide range of non-surgical or traumatic OCS etiology, including thyroid eye disease, nonspecific orbital inflammatory conditions, and orbital tumors, all of which can lead to retrobulbar hemorrhage and an increase in orbital pressure [

5]

Detection of orbital compartment syndrome and retrobulbar hemorrhage with the following orbital decompression surgery (ODS) is time critical, hence an ophthalmic emergency, as irreversible conditions affect vision, diplopia, and ocular motility, and may lead to permanent blindness within hours. The distinction between OCS and RBH is relevant, as urgent ODS can be necessary under certain circumstances, and decisions may be based solely on clinical signs. Bleeding of RBH can be intraconal and extraconal, which affects the clinical outcomes of the chosen surgical approach [

6]. Orbital compartment syndrome and retrobulbar hemorrhage are considered a clinical diagnosis, often based on clinical examination and the patient’s history upon presentation. Clinical signs of RBH include impaired visual acuity, ocular immobility, diplopia, hard eyeball, pain, proptosis, and a lost light reflex.

Several authors recommend orbital decompression surgery within 2 hours in case of retrobulbar hemorrhage, along with the results from Hayreh et al. (1980) animal studies of irreversible damage of the optic nerve due to ischemia after 105 minutes [

7]. Irreversible optic ischemia may occur within the first hour, while permanent visual loss is expected within a range of 1.5-2 hours upon the occurrence of OCS symptoms. The earlier treatment begins, the better the patient’s visual recovery is expected to be [

8].

Although preoperative radiological imaging (CT, MRI of the head and/or orbit) is beneficial, treatment should not be delayed solely to obtain radiological imaging to preserve the patient’s eyesight, according to Edmunds et al. (2019). The need for radiological imaging often depends on the severity of visual impairment. It may be redundant not to delay treatment, as an OCS diagnosis can be based on clinical signs and symptoms. In case of required further decompression surgery after initial ODS, additional imaging can be helpful to identify vascular malformations, debris, or anatomical status quo.

Due to its time-critical nature, the initial assessment for orbital compartment syndrome typically occurs upon the patient's arrival in the emergency department (ED) by an ED physician, often without specialized training in ophthalmology [

9] A complete and standardized examination by an ophthalmologist might not be possible at the time of the patient's presentation in the emergency department due to the time-critical aspect of OCS.

Clinical examination by an ED physician may be limited to generally subjective observations of bulbar proptosis, a hardened orbital bulb, a history of pain, vision impairment, pupillary deficit, or diplopia. To make it even more complicated, the assessment of ocular motility or pupils can be misleading in cases of unconscious patients, alcohol and drug intoxication, or traumatic mydriasis [

10].

Orbital decompression surgery aims to reduce the pressure on and reestablish perfusion of the optic nerve. ODS consists of several techniques often combined depending on the etiology of OCS and the severity of visual impairment. The surgical management protocol for orbital decompression is not standardized and varies [

11].

As an effective method of orbital decompression surgery, lateral canthotomy (LC) and inferior cantholysis (IC) are established. LC/IC can even be performed under local anesthesia, underlining the time-critical aspect of ODS in preserving visual function. Further standard ODS procedures include techniques performed under general anesthesia, such as lateral wall decompression, orbital floor decompression, endonasal medial wall decompression (involving partial removal of the lamina papyracea), and orbital fat decompression. Often, surgical decompression techniques are combined depending on the etiology of OCS.

This retrospective study aimed to analyze the visual function outcome after orbital decompression surgery. This study evaluates surgical outcomes to optimise clinical decision-making in case of an orbital compartment syndrome.

2. Materials and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 28 patients undergoing orbital decompression surgery due to orbital cellulitis syndrome (OCS) and retrobulbar hemorrhage at the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Medical School OWL, Bielefeld University, Campus Klinikum Bielefeld Mitte, Germany, from May 2016 to October 2024.

Key data collected included etiology, the time between symptom occurrence and surgery, surgical techniques, preoperative symptoms, and postoperative outcomes after OCS. Postoperative outcomes, including ocular motility (improvement or persistence of motility impairment), visual acuity (changes in pre- and postoperative visual acuity), and diplopia (presence or absence of double vision after surgery), were evaluated.

2.1. Subjects

Study group: 28 patients treated for orbital compartment syndrome and retrobulbar hemorrhage underwent orbital decompression surgery as a first-line treatment at our department.

2.2. Symptoms

The diagnosis of orbital compartment syndrome is based on a clinical examination of the orbit, including impaired visual acuity, ocular immobility, diplopia, a hard eyeball, pain, and proptosis, as well as, if available, CT imaging. OCS symptoms can range from non-present to various symptoms. We defined orbital compartment syndrome as the presence of vision impairment, diplopia, or ocular motility impairment due to orbital pathologic conditions, such as trauma, inflammatory conditions, or orbital tumors, as classified by retrobulbar hemorrhage based on CT imaging. The presence of bleeding, edema, bone displacement, or tumors in the orbit was evaluated in the axial and coronal planes. The elapsed time between the first symptoms of OCS/RBH and surgical treatment, as well as the postinterventional functional outcome regarding visual impairment, was documented.

The severity of visual impairment was classified according to the recommendations of the WHO Consultation on “Development of Standards for Characterization of Vision Loss and Visual Functioning.”

Table 1.

WHO visual impairment categories ICD-10 Version [

12].

Table 1.

WHO visual impairment categories ICD-10 Version [

12].

| Category |

Presenting distance visual acuity |

| |

Worse than: |

Equal to or better than: |

| 0 Mild or no visual impairment |

|

6/18

3/10 (0.3)

20/70 |

| 1 Moderate visual impairment |

6/18

3/10 (0.3) 20/70 |

6/60

1/10 (0.1)

20/200 |

| 2 Severe visual impairment |

6/60

1/10 (0.1)

20/200 |

3/60

1/20 (0.05)

20/400 |

| 3 Blindness |

3/60

1/20 (0.05)

20/400 |

1/60*

1/50 (0.02)

5/300 (20/1200) |

| 4 Blindness |

1/60*

1/50 (0.02)

5/300 (20/1200) |

Light perception |

| 5 Blindness |

No light perception |

| 6 |

Undetermined or unspecified |

| |

* or counts fingers (CF) at 1 meter |

2.3. Surgery

All 28 patients received first-line treatment with orbital decompression surgery under general anesthesia. Orbital decompression surgery aims to reduce pressure on the optic nerve and restore blood flow to the optic nerve and retina, thereby improving visual function. Orbital decompression surgery involves several techniques, often combined depending on the etiology of orbital compartment syndrome (OCS). ODS techniques included lateral decompression (lateral canthotomy), orbital floor decompression, endonasal medial wall decompression (removal of the lamina papyracea), and broad slitting of the periorbital barrier with orbital fat protrusion.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed first. Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and proportions. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the primary endpoints of postoperative improvement in ocular motility, diplopia, and visual acuity, while accounting for potential risk factors, including age, sex, and time to surgery. The effect measures for all analyses were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and p-values (p) as appropriate. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the statistical software SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. Results

Specialisations of first contact upon occurrence of symptoms were in 61% of the ophthalmology department, in 21% of the Ear, Nose and Throat department (ENT), and 18% of the other specialisation departments (internal medicine, trauma surgery, oncology).

3.1. Patient Characteristics

The average age range of patients was 53.18 years (SD: 20.25). A total of 17 patients (61%) were male, whilst 11 were female (39%).

Evaluation of OCS etiology indicated trauma (centro-lateral midface injury due to a downfall or strike) in 19 out of 28 cases (68%). In 4 cases (14%), iatrogenic etiology (ophthalmic surgery, sinus surgery) was identified. Tumor occurred in 3 cases (11%), while inflammatory conditions were found in only 2 cases (7%).

In 13 cases (46%), the left eye was affected, whilst in 15 cases (54%), the right eye was affected.

The preoperative best corrected visual acuity was 0.2 (SD: 0.3) on average. Thirteen patients (46%) were preoperatively measured with a visual acuity of 0.05 or less, categorized as „blindness“ according to the WHO visual impairment categories. 96% (27 cases) showed preoperative ocular motility impairment. Diplopia was preoperatively present in 46% (13 cases).

3.2. Surgery

A total of 28 patients treated for orbital compartment syndrome underwent orbital decompression surgery as a first-line treatment. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia in all cases.

Orbital decompression surgery was performed with a median of 8.40 hours (Q1: 4.8; Q3: 24.0) upon occurrence of symptoms. Eighty-two percent (23 patients) received surgical treatment within 1-24 hours after the occurrence of symptoms. 18% (5 patients) received therapy after 24 hours.

The time between the occurrence of symptoms and surgery, in hours, showed several outliers regarding etiology. Inflammatory etiology (n = 2, median [Q1; Q3]: 180.0 [24.0; 336.0]) and tumor etiology (n = 3, 48.0 [24.0; 168.0]) revealed high observed times to surgery.

Trauma etiology (n = 19, 7.2 [4.8; 12.0]) and iatrogenic etiology (n = 4, 3.9 [2.7; 6.0]) showed considerably lower times until decompression surgery than tumor and inflammation etiology.

Medial wall decompression was the most performed decompression technique in 26 out of 28 cases (93%), followed by lateral decompression (LC/IC) in 23 out of 28 cases (82%). Orbital floor wall decompression was performed in only 4 cases (14%). Surgery techniques were often combined depending on etiology, degree of orbital compartment syndrome, and surgeon experience.

The median time to surgery for LC/IC treatment as emergency therapy was 25.5 hours (3.0; 48.0) upon the occurrence of symptoms. In 1 case, LC/IC was performed after 3.0 hours (iatrogenic etiology) and after 48.0 hours (tumor etiology).

Out of 13 cases with preoperative blindness, 1 case (8%) received LC/IC treatment as emergency therapy. Out of 6 cases with severe visual impairment, 1 case (17%) received LC/IC treatment as emergency therapy.

Orbital decompression surgery techniques were combined mostly as 2-wall decompression in 68% (19/28 cases). Trauma etiology represented the majority of 2-wall decompression in 74% (14 cases). With iatrogenic (16%, 3 cases) and tumor etiology (20%, 2 cases), 2-wall decompression was performed on rarer conditions.

A 3-wall decompression was performed in 11% (3 cases). Two out of 3 cases (67%) with 3-wall decompression were traumatic, while 1 case (33%) was of iatrogenic origin.

A single 1-wall decompression was carried out in 21% of the cases (6 cases). The etiology was traumatic in 3 out of 6 cases (50%). One-wall decompression was performed infrequently in cases of inflammatory etiology (33%, 2 cases) and tumor etiology (17%, 1 case).

3.3. Analysis of Preoperative Visual Function

3.3.1. Preoperative Ocular Motility

Ninety-six percent (27 patients) showed preoperative ocular motility impairment in the affected eye. In 4 out of 4 cases (100%), iatrogenic etiology was associated with ocular motility impairment. Inflammatory etiology was related to ocular motility impairment in all 2 cases (100%). All three tumor (100%) cases suffered from ocular motility impairment. Impaired ocular motility was present in 18 out of 19 (95%) trauma cases.

Only one patient (4%) was unaffected by ocular motility impairment. In this case, trauma was the etiology.

3.3.2. Preoperative Diplopia

Diplopia was preoperatively present in 46% (13 cases). 54% of cases were preoperatively not affected by diplopia.

One out of three tumor patients (33%) was affected by diplopia. All patients with inflammatory etiology (100%, 2 out of 2) had diplopia. One out of four patients (25%) with iatrogenic etiology had diplopia preoperatively. 47% of trauma patients (9 out of 19) suffered from diplopia.

Out of 15 cases not affected by diplopia trauma patients (67%) represented the main etiology group. Iatrogenic (20%) and tumor (13%) etiology were less affected by diplopia.

3.3.3. Preoperative Visual Acuity (VA)

The average preoperative measured VA of the affected eye was 0.2 (SD: 0,3). VA was categorized according to WHO visual impairment categories.

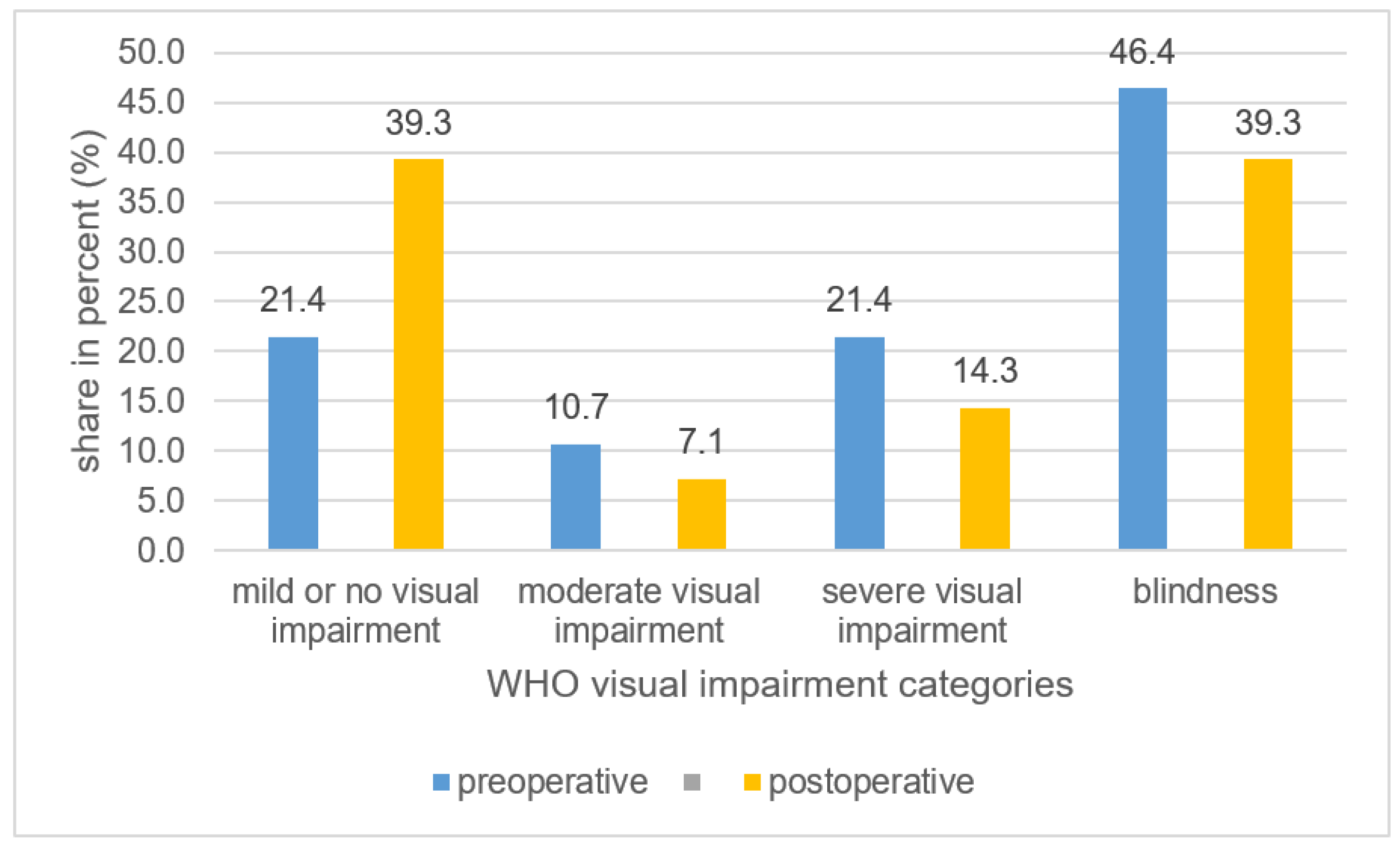

A total number of 13 patients (46,4%) were preoperatively measured with a VA of 0.05 or less categorised as „blind“. 6 cases (21,4%) presented with a „severe visual impairment“. Preoperative VA was classified as „mild or no visual impairment“ in 6 cases (21,4%). Three cases (10,7%) had „moderate visual impairment“

Tumor etiology (n=3) showed the lowest mean preoperative VA of 0,0067 (SD 0,011). All three patients (100%) were already categorized as „blind“ preoperatively.

Patients with inflammation etiology (n=2) indicated the highest preoperative VA with a mean of 1,0 (SD: 0). The VA of both patients (100%) were classified as „mild or no visual impairment“ according to WHO visual impairment categories.

Patients with iatrogenic etiology (n=4) indicated a mean preoperative VA of 0,28 (SD 0,48). 2 patients (50%) with iatrogenic etiology were classified as „blind“. Severe visual impairment was present in 1 case (25%) with iatrogenic etiology. Classification of „Mild or no visual impairment“ was also observed in 1 case (25%) with iatrogenic etiology.

Trauma patients (n=19) had a mean preoperative VA of 0,17 (SD 0,23). Eight patients (42%) were already preoperatively categorized as „blind. “ Five patients (26%) with trauma etiology suffered from „severe visual impairment “ „Moderate“ and „mild or no visual impairment“ were equally represented with three trauma etiology patients (16%) in each group.

4. Analysis of Postoperative Visual Function

4.1. Postoperative Ocular Motility

Preoperative ocular motility impairment was present in 96% of patients. After ODS, ocular motility impairment was recorded postoperatively in 32 % (n=9).

Inflammatory etiology was associated with improvement of ocular motility after ODS in 100% of cases (n=2), iatrogenic etiology in 75% (n=4) and trauma etiology in 68% (n=19). Tumor etiology (n=3) did not benefit from ODS as ocular motility impairment was postoperative persistent in 100% of cases.

Results from logistic regression analysis revealed a clinically relevant decreased chance for improvement in ocular motility for females compared to males (OR [95% confidence interval]: 0.28 [0.04; 2.02]). There was no evidence for an association between improvement in ocular motility and age or time to surgery (see

Table 1).

4.2. Postoperative Diplopia

Preoperative diplopia was present in 46% of patients. Diplopia improved by 62% after ODS, and diplopia was postoperative persistent in 18% (n=5). After ODS, Diplopia improved in 100% of inflammatory etiology cases (n=2).

26% (n=5) of trauma etiology cases did improve after ODS, whilst 21% (n=4) did have persistent diplopia after ODS. Trauma etiology cases were in 53% (n=10) of cases unaffected by diplopia preoperatively.

Iatrogenic etiology improved by 25% (n=1), whilst 75 % (n=4) of iatrogenic etiology was unaffected by diplopia pre- and postoperative.

Tumor etiology cases (n=3) was less likely to be associated with improvement of diplopia after ODS. 67% (n=2) were unaffected by diplopia pre-and postoperative 1 case (33%), but this did not improve after ODS.

Logistic regression analysis indicates that the chance for diplopia improvement is lower for females compared to men (OR: 0.23 [0.02; 2.68]) while adjusting for age and time to surgery (see

Table 1).

4.3. Postoperative Visual Acuity (VA)

After orbital decompression surgery, postoperative visual improvement of the affected eye was measured in 36% (10 cases).

Out of these 10 cases, 90% (9 cases) were of trauma etiology, and 10 % (1 case) were of iatrogenic etiology. No visual improvement was reported in 64 % (18 cases).

Visual acuity of Trauma patients did improve after surgery in 47% of the cases (9 cases).

Iatrogenic etiology cases showed the 2nd highest mean postoperative visual improvement (+ 0,092) after surgery. Iatrogenic etiology patients did improve after surgery in 25 % of cases (n=4).

Tumor etiology cases did not show visual improvement (+/- 0) after surgery. All three patients (100%) were already categorized as „blind“ preoperatively and showed the lowest mean visual improvement of 0,0067.

Both inflammatory etiology cases (n=2) did not show visual improvement (+/- 0). Notably, patients with inflammation etiology had the highest preoperative VA with a mean of 1,0 (SD: 0).

No visual improvement was recorded out of the category „mild or no visual impairment“ (6 cases).

Preoperatively, a total number of 13 patients (46%) were measured with a VA of 0.05 or less and categorized as „blind“. The number of patients within VA category „blindness“ dropped after OCS from 46% to 39% (see

Figure 1). In 4 out of 13 (31%) preoperatively as blind categorised cases, VA improved after ODS, whilst 9 cases (69%) remained blind.

Postoperative analysis of the VA category „severe visual impairment“ indicated a drop from 21% to 14%. The category „mild or no visual impairment“ improved the most by increasing the category rate from 21% to 39%. The „moderate visual impairment“ category shrunk from 11% to 7% (see

Figure 1).

The findings from the logistic regression indicate that females, again, had a lower chance for improvement compared to males (OR: 0.30 [0.04; 2.43]). Furthermore, the chance for improvement decreased with increasing time to surgery (OR: 0.94 [0.85; 1.04]) (see

Table 1).

5. Discussion

Retrobulbar hemorrhage (RBH) is a rare but severe pathology, depending on its degree, possibly leading to an orbital compartment syndrome with a consecutive risk of persistent blindness. Edmunds et al. (2019) consider RBH secondary to trauma as the main reason for orbital compartment syndrome. There is a wide range of surgical, non-surgical, or trauma-related OCS etiology, all of which can lead to retrobulbar hemorrhage and an increase in orbital pressure,

In our study, 28 patients treated for orbital compartment syndrome and retrobulbar hemorrhage underwent orbital decompression surgery as a first-line treatment. Evaluation of our study group etiologies identified trauma as the main etiology.

These findings are consistent with the literature. Christie et al. (2018) identified facial trauma etiology and surgery as the main precipitating factors for RBH. Yuen et al. (2003) cite inflammation etiology in up to 6% accountable for orbital disorders [

13]. RBH due to tumor etiology is less common, and only a few case reports are documented. Maurer et al. (2013) found OCS mostly in male patients in 68% of cases, consistent with our study results of 61% in the male population.

The diagnosis of orbital compartment syndrome and retrobulbar hemorrhage with acute visual impairment is considered a primarily clinical diagnosis based on clinical examination underlining the time-critical aspect as an ophthalmic emergency.

Several authors recommend orbital decompression surgery within 2 hours in case of retrobulbar hemorrhage, along with the results from Hayreh et al. (1980) animal studies of irreversible damage of the optic nerve due to ischemia after 105 minutes [

14,

15,

16].

Comparing time to surgery with literature shows a wide range of time delays before surgical intervention. Soare et al. (2015) reviewed clinical cases series of orbital decompression surgery. 48% of listed papers labeled the time to surgery without specifying the exact time data. To some extent case reports with even 1 case were published [

17,

18].

Time to surgery varied from less than 1 hour to 360 hours upon the occurrence of symptoms, consistent with results from our study data; in our study, orbital decompression surgery was performed within a range of 2,4 to 336 hours. Most (82%) received surgical treatment within 24 hours of symptoms, consistent with data published by Christie et al. (2018).

Our study data indicated several outliers regarding the time between the occurrence of symptoms and surgery. Trauma etiology (median 7.2 hours) and iatrogenic etiology (median 3.9 hours) showed considerably lower times until decompression surgery than tumor (median 48.0 hours) and inflammation etiology (median 180.0 hours).

Therefore, the late occurrence of symptoms and delayed patient presentation in our department in the case of tumor and inflammation etiology explains the higher time needed for surgery data. Patients with relatively slower symptomatic progression and moderate impact on vision impairment develop rather subacute ODS symptoms [

19]. In the case of inflammatory etiology, 100% of our patients presented with a normal VA preoperatively.

According to Yuen et al. (2003), in the case of inflammation etiology, symptoms mainly develop acutely (hours to days) but also occur subacute over weeks or even over months, explaining a considerably higher time to surgery data. Muscente et al. (2024) indicate as treatment options of inflammatory orbital compartment syndrome clinical observation, NSAID, and steroid therapy, which explains a delayed surgical intervention in refractory cases as an acute ophthalmological surgical emergency was initially not the case in inflammatory patients of our study group [

20].

Although surgical intervention after the occurrence of symptoms in patients with inflammatory and tumor etiology was relatively late, McCallum et al. (2019) consider orbital decompression surgery as still worthy in case of delayed presentation [

21].

Preoperative blindness is a predictor of persistent blindness despite surgical decompression. Fuller et al. (1990) postulate the amount of damage to the optic nerve or macula at the time of injury is the most important prognostic factor. The surgical outcome is, therefore, usually determined by the patient’s visual acuity [

22].

Preoperatively, 46% of our study patients were categorized as „blind“ or suffered in 26% from „severe visual impairment“ according to WHO visual impairment categories. These findings are consistent with Maurer et al. (2013), who linked blindness to a retrobulbar hemorrhage in 48% of the patients.

The risk of permanent loss of visual acuity in case of an impaired visual function due to retrobulbar hemorrhage ranges from 48% - to 52%, according to the literature; this is consistent with our retrospective data. The number of patients within VA category „blindness“ dropped after orbital decompression surgery OCS from 46% to 39%.

Orbital decompression surgery techniques were combined mostly as 2-wall decompression in 68%. A single 1-wall decompression was carried out in 21% of cases, whilst a 3-wall decompression was performed in only 11 %. Medial wall decompression was the most performed in 93% of cases, followed by lateral wall decompression (82%) and orbital floor wall decompression (14%).

It is noteworthy that visual acuity recovery after orbital decompression surgery is not always immediate, according to McCallum et al. (2019). Our study had a relatively short follow-up period; therefore, it is reasonable that a long-term follow-up might show better visual acuity results.

Preoperative ocular motility impairment was present in 96%. After orbital decompression surgery, ocular motility impairment was recorded in only 32%.

These positive results can be interpreted as effective pressure relief to the orbit after ODS. In case of persistent ocular motility impairment after ODS post-surgery, muscular adhesions, secondary scarring, or irreversible muscle fibrosis are possible reasons for non-responders. A short follow-up is noteworthy as bulbus motility was directly examined postoperatively within 24 hours. A long-term follow-up may show better postoperative ocular motility results.

Preoperative diplopia was present in 46%, whilst after OCS, diplopia was persistent in only 18%. Equally to ocular motility outcome these positive results can be interpreted as effective pressure relief to the orbit after ODS. In case of persistent post-surgery diplopia, possible reasons for non-responders are muscular adhesions, secondary scarring, or irreversible muscle fibrosis. A short follow-up is noteworthy as patients were postoperatively examined for diplopia within 24 hours. A long-term follow-up may show better postoperative ocular motility results.

Time management of acute retrobulbar hemorrhage diagnosis and treatment must be identified as an essential factor of OCS treatment outcome. From the patients’ first presentation in the emergency department to the correct identification of OCS/RBH, several critical aspects might affect the timing of surgical intervention.

According to Edmunds et al. (2019), 96% of non-ophthalmic emergency department (ED) physicians know the consequences of permanent vision loss due to delayed treatment in the case of orbital compartment syndrome. Although 83 % correctly diagnosed RBH in a clinical case survey, only 37% of ED physicians would -theoretically- perform LC/IC as a first-line treatment due to a lack of training or concerns regarding injuring the patient’s eye.

Compared to our real-life study results, we even identify a considerably higher reluctance towards performing emergency LC/IC - even amongst physicians in ophthalmology and ENT. A fast and precise assessment and therapy of OCS/RBH can be challenging, especially in times of crowded emergency departments and limited access to specialized personnel.

Improvement in surgical training independent from physicians' specialties is crucial to overcome the reluctance to perform emergency LC/IC upon patient's first presentation to prevent time delay of OCS/RBH treatment in the future.

Due to its time-critical aspect, a CT should not be made before LC/IC in case of suspected RBH. The potential risks of performing immediate LC/IC are manageable and, therefore, should outweigh the high risk of permanent vision loss in case of delayed surgical intervention [

23].

Lastly, our study had limitations regarding several cases underlining the rare aspect of OCS and retrobulbar hemorrhage etiology. Notably, most published literature reports a relatively small number of cases due to the rare occurrence of OCS and retrobulbar hemorrhage etiology.

Although we did not find significant results regarding the timing of surgery and postoperative outcome regarding diplopia, ocular motility impairment, and visual improvement, the consequences of a delayed surgical orbital compartment syndrome treatment are assumed to be severe. Preoperative blindness is a predictor of persistent blindness despite surgical decompression.

The most important prognostic factor is the amount of damage to the optic nerve at the time of injury. The surgical outcome is, therefore, usually determined by the patient’s visual acuity. Our study group had a relatively high number of patients severely affected by RBH, reflected by the high rate of patients preoperatively categorized as „blind“ or with „severe visual impairment“ and a relatively high time to surgery, underlining the time-critical aspect of OCS/RBH treatment.

6. Conclusions

Retrobulbar hemorrhage can cause acute visual impairment due to orbital compartment syndrome. Orbital decompression surgery is a valuable time-critical tool in the first-line treatment of acute visual function loss. Our data showed considerable postoperative improvement rates regarding visual acuity, diplopia, and ocular motility. Our data underlines the need to optimize the time management of acute retrobulbar hemorrhage treatment due to its critical time aspect and immense effect on vision recovery. There is a need to improve the surgical training of (emergency department) physicians, regardless of specialty, to perform LC/IC as emergency therapy.

Author Contributions

KA: writing, data collection, statistics, final approval. PC: data collection, idea, final approval. SLU: data collection, final approval. RC,: data collection final approval. HA: statistics, final approval. AM: data collection final approval. TI: writing, design, data collection, final approval, accountable for all aspects. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Statement of Ethics

The study is in line with the human studies guidelines and ethically follows the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The study was reviewed and positively evaluated by the Ethical Commission of the Ärztekammer Westfalen-Lippe, University of Münster and University of Bielefeld (2025-033-f-S).

References

- Gordon S, Macrea H. Monocular blindness as a complication of the treatment of malar fracture. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946). 1950;6(3):228–32.

- Hargaden M, Goldberg SH, Cunningham D, Breton ME, Griffith JW, Lang CM. Optic neuropathy following simulation of orbital hemorrhage in the nonhuman primate. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;12(4):264–272. [CrossRef]

- Hislop WS, Dutton GN, Douglas PS. Treatment of retrobulbar haemorrhage in accident and emergency departments. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996 Aug;34(4):289-92. PMID: 8866062. [CrossRef]

- Dunya IM1, Salman SD, Shore JW. Ophthalmic complications of endoscopic ethmoid surgery and their management. - PubMed -NCBI. Am J Otolaryngol. 1996;17(5):322–331. [CrossRef]

- Bliss A, Craft A, Haber J, Inger H, Mousset M, Chiang T, Elmaraghy C. Visual outcomes following orbital decompression for orbital infections. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2024 Jan;176:111824. . Epub 2023 Dec 16. PMID: 38134589. [CrossRef]

- Perry M. Acute proptosis in trauma: retrobulbar hemorrhage or orbital compartment syndrome--does it really matter? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 Sep;66(9):1913-20. PMID: 18718400. [CrossRef]

- Hayreh SS, Weingeist TA. Experimental occlusion of the central artery of the retina. IV: retinal tolerance time to acute ischaemia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980;64(11):818–825. [CrossRef]

- Sun, M. T., Chan, W. O., & Selva, D. (2014). Traumatic orbital compartment syndrome: importance of the lateral canthomy and cantholysis. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 26(3), 274-278. [CrossRef]

- Edmunds MR, Haridas AS, Morris DS, Jamalapuram K. Management of acute retrobulbar haemorrhage: a survey of non-ophthalmic emergency department physicians. Emerg Med J. 2019;36(4):245–247. [CrossRef]

- Meyer S, Gibb T, Jurkovich GJ. Evaluation and significance of the pupillary light reflex in trauma patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1993 Jun;22(6):1052-7. PMID: 8503525. [CrossRef]

- Soare S, Foletti JM, Gallucci A, Collet C, Guyot L, Chossegros C. Update on orbital decompression as emergency treatment of traumatic blindness. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015 Sep;43(7):1000-3. Epub 2015 May 29. PMID: 26116304. [CrossRef]

-

https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en.

- Yuen SJA, Rubin PAD. Idiopathic Orbital Inflammation: Distribution, Clinical Features, and Treatment Outcome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(4):491–499. [CrossRef]

- Colletti G, Valassina D, Rabbiosi D, Pedrazzoli M, Felisati G, Rossetti L, et al: Trau- matic and iatrogenic retrobulbar hemorrhage: an 8 patient series. J Oral Max- illofac Surg 70(8): 464ee468e, 2012.

- Sun MT, Chan WO, Selva D: Traumatic orbital compartment syndrome: importance of the lateral canthomy and cantholysis. Emerg Med Australas 26(3): 274e278, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ballard SR, Enzenauer RW, O'Donnell T: Emergency lateral canthotomy and cantholysis: a simple procedure to preserve vision from sight threatening orbital haemorrhage. J Spec Oper Med 9: 26e32, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Vassallo S, Hartstein M, Howard D, Stetz J: Traumatic retrobulbar hemorrhage: emergent decompression by lateral canthotomy and cantholysis. J Emerg Med 22(3): 251e256, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Larsen M, Wiesland ES: Acute orbital compartment syndrome after lateral blow-out fracture effectively relieved by lateral cantholysis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 77(2): 232e233, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Turgut B, Karanfil FC, Turgut FA. Orbital Compartment Syndrome. Beyoglu Eye J. 2019 Feb 12;4(1):1-4. PMID: 35187423; PMCID: PMC8842040. [CrossRef]

- Muscente, J. (2024). Orbital Compartment Syndrome. In: Khasnabish, I., Chikwinya, T., Muscente, J. (eds) Complex Cases in Clinical Ophthalmology Practice. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- McCallum E, Keren S, Lapira M, Norris JH. Orbital Compartment Syndrome: An Update With Review Of The Literature. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019 Nov 7;13:2189-2194. PMID: 31806931; PMCID: PMC6844234. [CrossRef]

- Fuller DG, Hutton WL. Prediction of postoperative vision in eyes with severe trauma. Retina. 1990;10 Suppl 1:S20-34. PMID: 2191380. [CrossRef]

- Papadiochos I, Petsinis V, Sarivalasis SE, Strantzias P, Bourazani M, Goutzanis L, Tampouris A. Acute orbital compartment syndrome due to traumatic hemorrhage: 4-year case series and relevant literature review with emphasis on its management. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023 Mar;27(1):101-116. Epub 2022 Jan 27. Erratum in: Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024 Dec;28(4):1663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-024-01282-7. PMID: 35083570. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).