Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

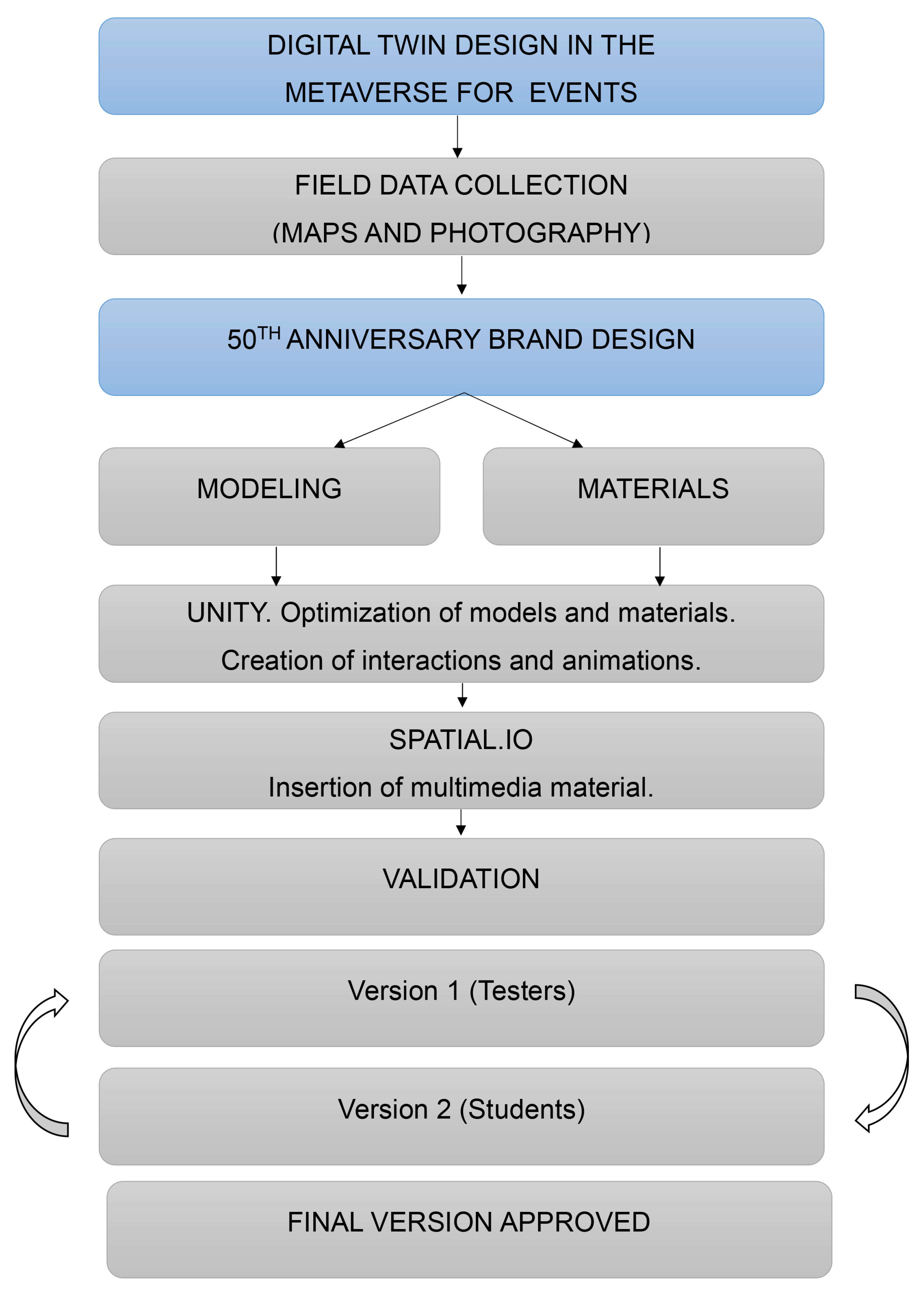

2.1. Methodology for Designing Digital Twins in the Metaverse for Events

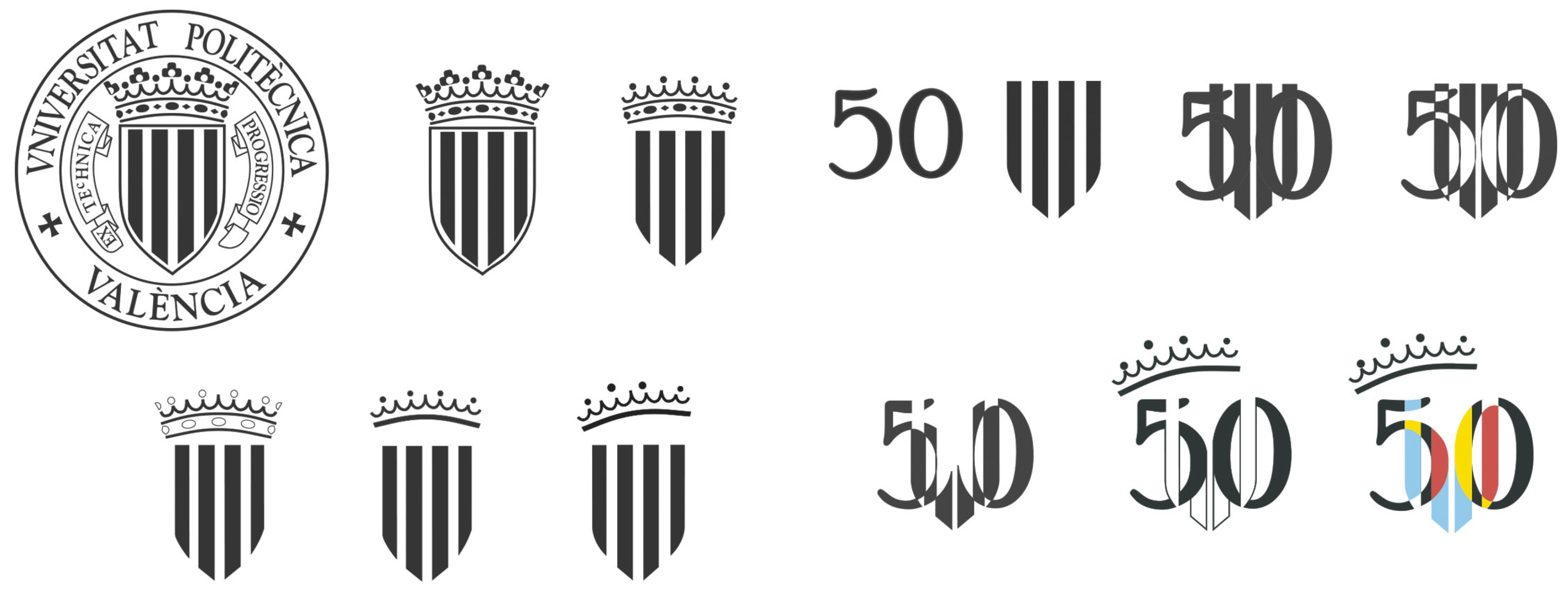

2.2. Study of the Event’s Graphic Design

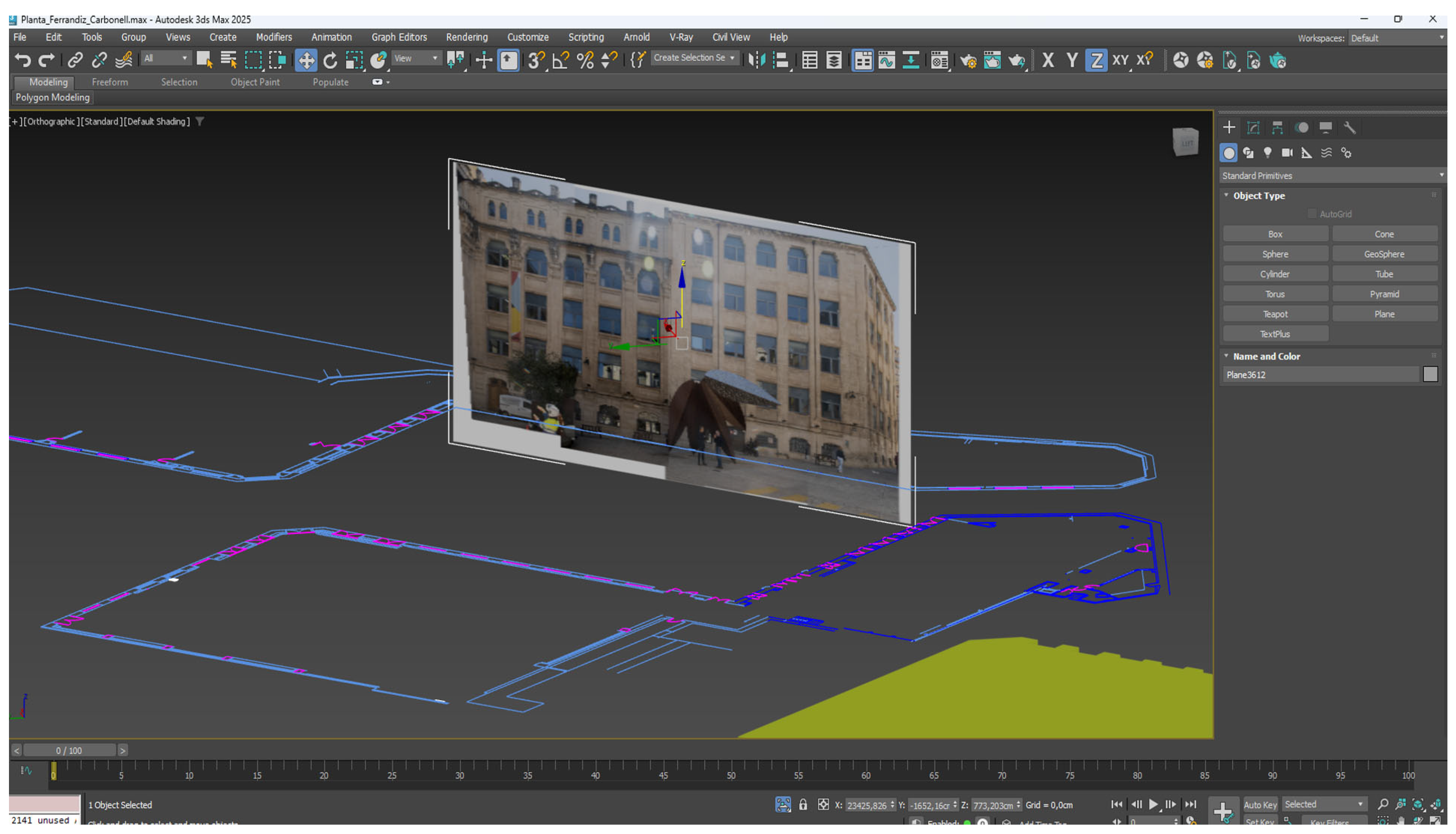

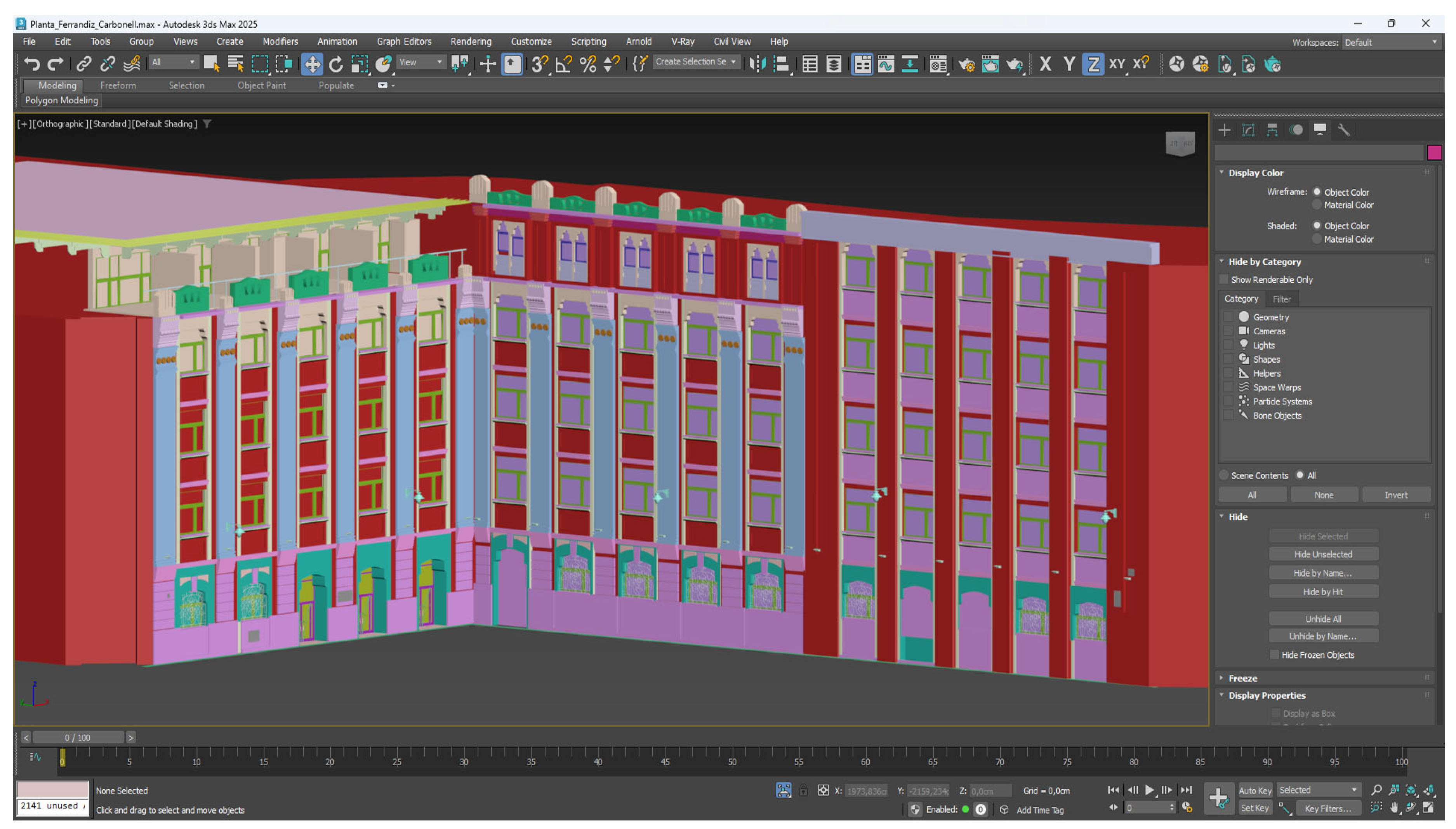

2.3. Modeling and Texturing of the Digital Twin

2.4. Optimization of Models and Materials with Unity. Creation of Interactions and Animations

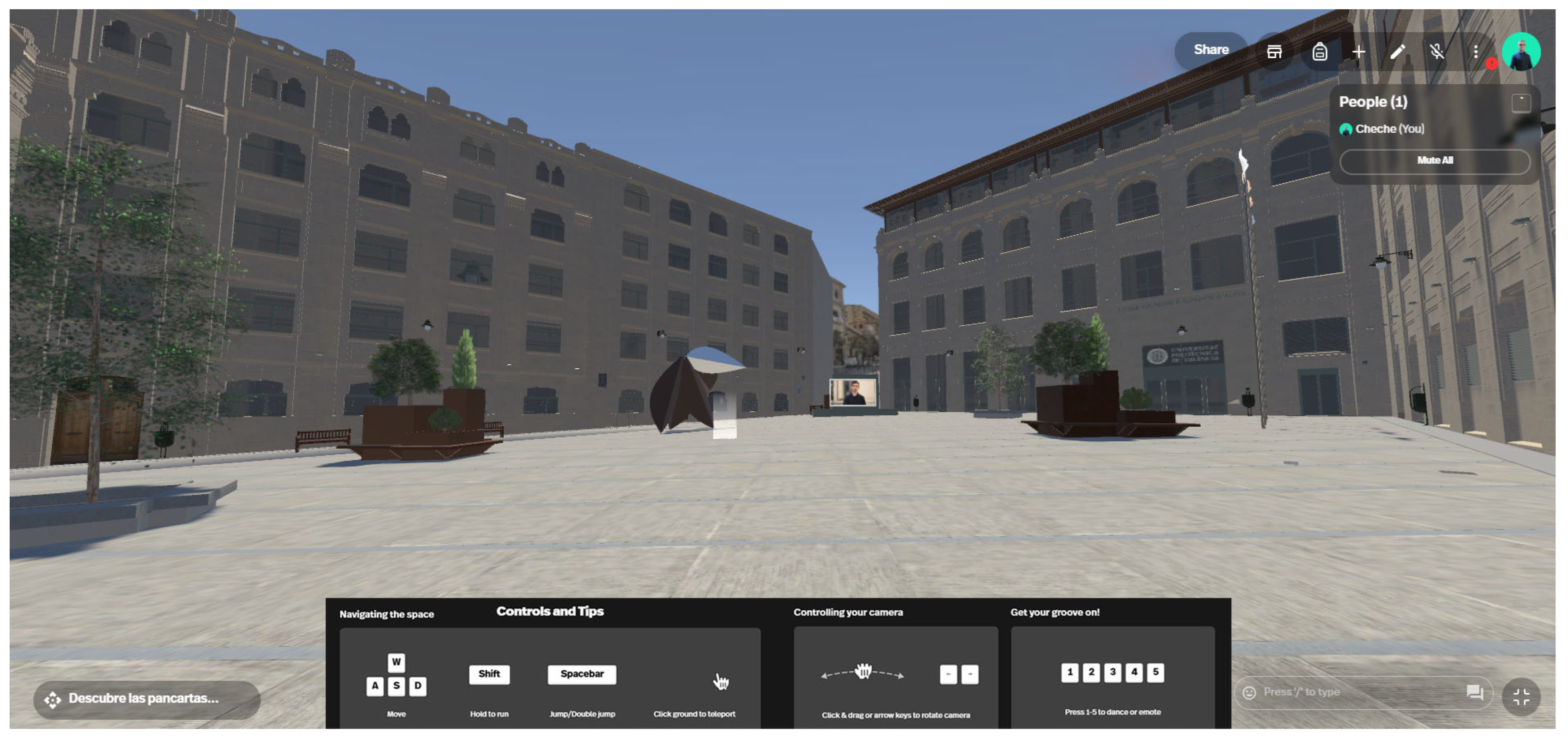

2.5. SPATIAL.IO. Insertion of Multimedia Material

2.6. Research Design

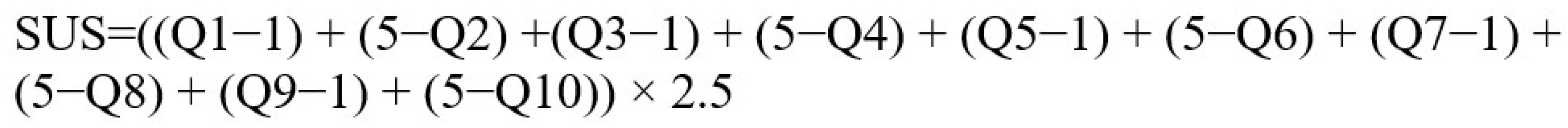

2.7. Data Analysis

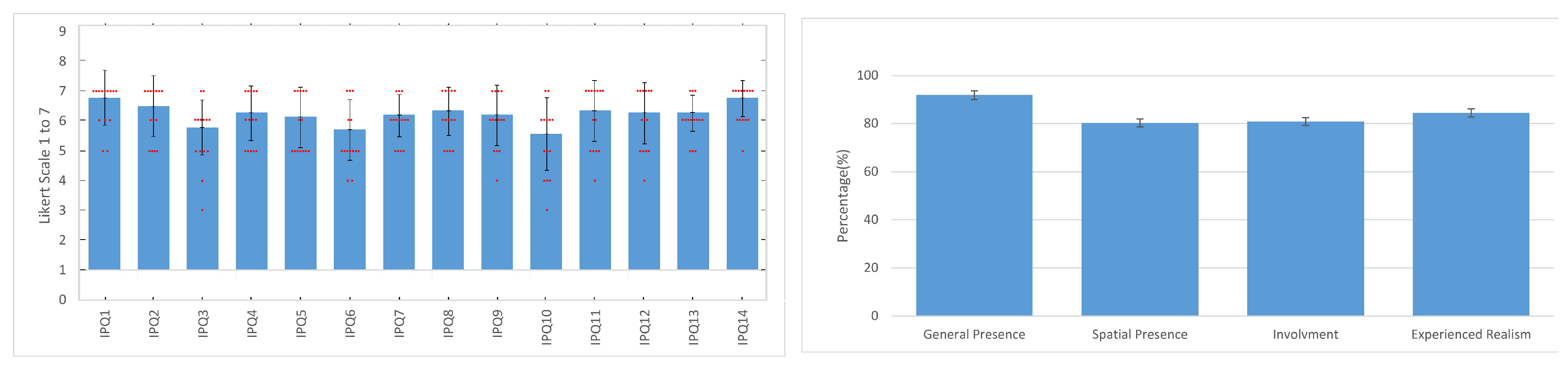

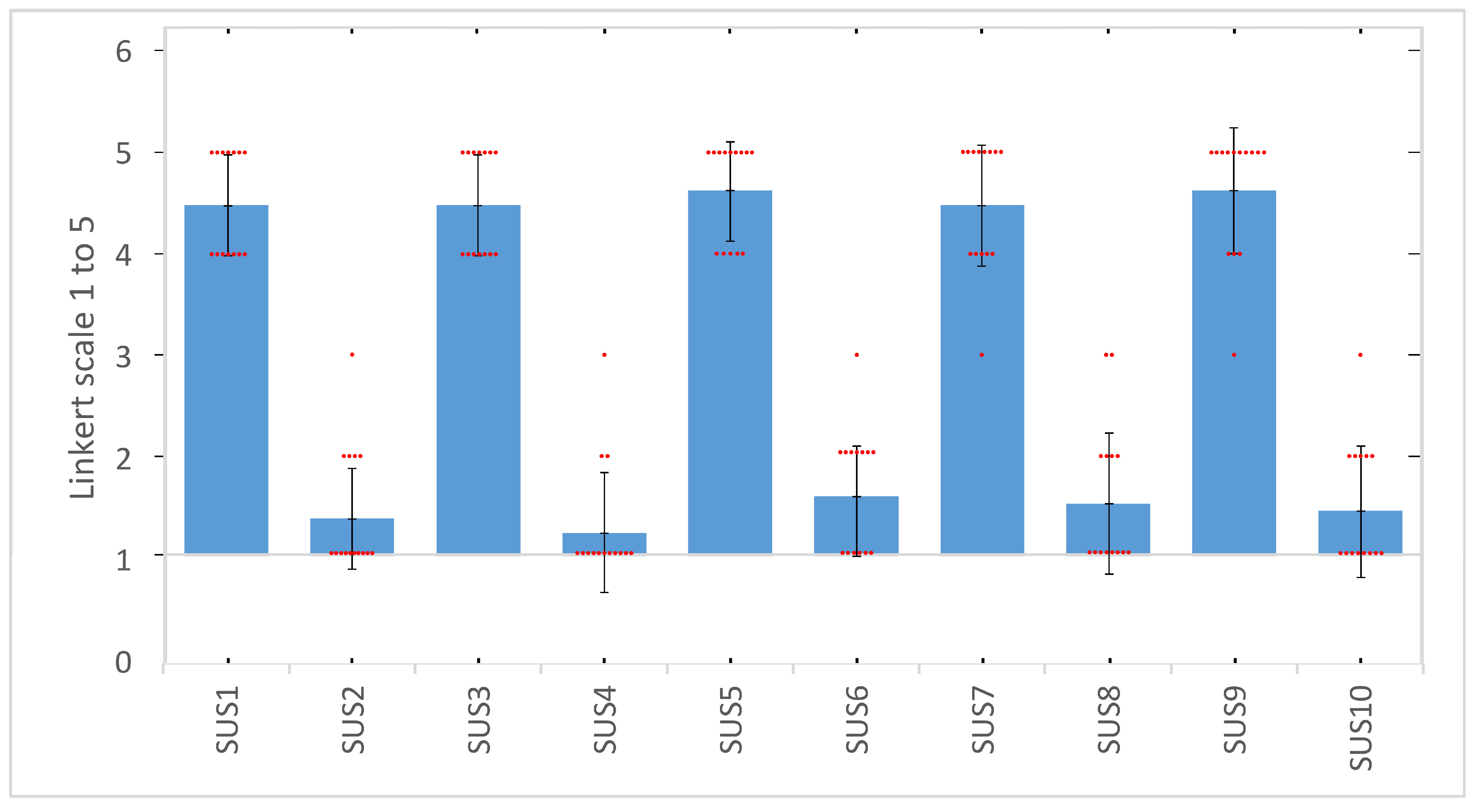

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DT | Digital Twins |

| MV | Metaverse |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| MR | Mixed Reality |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| IoT | Internet if Things |

| NFTs | Non-Fungible Tokens |

| VE | Virtual Environment |

References

- Dayoub, B.; Yang, P.; Omran, S.; Zhang, Q.; Dayoub, A. Digital Silk Roads: Leveraging the Metaverse for Cultural Tourism within the Belt and Road Initiative Framework. Electronics 2024, 13, 2306. [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Lin, M.S.; Leung, D. Metaverse as a driver for customer experience and value co-creation: implications for hospitality and tourism management and marketing. 621 International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2023, Vol. 35 No. 2, 701–716 . [CrossRef]

- Xuewei, W.; Xiaokun, Y. Current situation and development in applying metaverse virtual space in field of fashion[J].Journal of Textile Research, 2024, 45(04): 238-245.

- Wu, R.; Gao, L.; Lee, H.; Xu, J.; Pan, Y. A Study of the Key Factors Influencing Young Users’ Continued Use of the Digital Twin-Enhanced Metaverse Museum. Electronics 2024, 13, 2303. [CrossRef]

- Hashash,O;Chaccour,C;Saad,W;Sakaguchi,K;Yu,T; (2022). Towards a Decentralized Metaverse: Synchronized Orchestration of Digital Twins and Sub-Metaverses.

- S. K. Jagatheesaperumal et al., "Semantic-Aware Digital Twin for Metaverse: A Comprehensive Review," in IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 38-46, August 2023, .

- Aung,N;Dhelim,S;Ning, H. et al. Web3-enabled Metaverse: The Internet of Digital Twins in a Decentralised Metaverse. TechRxiv. January 02, 2024.

- Grieves, M., Hua, E.Y. (2024). Defining, Exploring, and Simulating the Digital Twin Metaverses. In: Grieves, M., Hua, E.Y. (eds) Digital Twins, Simulation, and the Metaverse. Simulation Foundations, Methods and Applications. Springer, Cham.

- Adnan,M; Ahmed,I;Iqbal,S;Rayyan Fazal,M;Siddiqi,S.J; Tariq, M. (2024) Exploring the convergence of Metaverse, Blockchain, Artificial Intelligence, and digital twin for pioneering the digitization in the envision smart grid 3.0, Computers and Electrical Engineering, Volume 120, Part B, 109709, ISSN 0045-7906, . [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.; Oliveira, A. Where Are We Now?—Exploring the Metaverse Representations to Find Digital Twins. Electronics 2024, 13, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Xing,H; Minyu,C; Yuezhong,T; Qian,A; Dongxia,Z; System Theory Study on Situation Awareness of Energy Internet of Things Based on Digital Twins and Metaverse (I): Concept, Challenge, and Framework[J]. Proceedings of the CSEE, 2024, 44(2): 547-560.

- Deng, B., Wong, I.A. and Lian, Q.L. (2024), "From metaverse experience to physical travel: the role of the digital twin in metaverse design", Tourism Review, Vol. 79 No. 5, pp. 1076-1087. [CrossRef]

- Kruachottiku,P.;Phanomchoeng,G.;Cooharojananone,N.;Kovitanggoon,K;Tea-makorn,P; "ChulaVerse: University Metaverse Service Application Using Open Innovation with Industry Partners," 2023 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, Singapore, 2023, pp. 0294-0299, .

- Shatilov,K;Alhilal,A;Braud,T; Lik-Hang Lee, Pengyuan Zhou, and Pan Hui. 2023. Players are not Ready 101: A Tutorial on Organising Mixed-mode Events in the Metaverse. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Metaverse Systems and Applications (MetaSys ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 14–20.

- Meliande,R.;Ribeiro,A.;Arouca,M.;Amorim,A.;Pestana,M.;Vieira, V.(2024). Meta-Education: A Case Study in Academic Events in the Metaverse. In Anais do XIX Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas Colaborativos, (pp. 28-41). Porto Alegre: SBC.

- Jeffrey,P.;Khatri,H.;Gauthier,C.;Coffey,B.;Garza,J.(2024) “Building a University Digital Twin.” 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Emerging Metaverse (ISEMV): 17-20.

- Sim, J.K.; Xu, K.W.; Jin, Y.; Lee, Z.Y.; Teo, Y.J.; Mohan, P.; Huang, L.; Xie, Y.; Li, S.; Liang, N.; et al. Designing an Educational Metaverse: A Case Study of NTUniverse. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2559. [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.K.; Xu, K.W.; Jin, Y.; Lee, Z.Y.; Teo, Y.J.; Mohan, P.; Huang, L.; Xie, Y.; Li, S.; Liang, N.; et al. Designing an Educational Metaverse: A Case Study of NTUniverse. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2559. [CrossRef]

- Shanthalakshmi Revathy, J.;J. Mangaiyarkkarasi.(2024) "Integration of Metaverse and Machine Learning in the Education Sector." Impact and Potential of Machine Learning in the Metaverse, edited by Shilpa Mehta, et al., IGI Global,pp. 74-99.

- Yun, S.-J.; Kwon, J.-W.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, W.-T. A Learner-Centric Explainable Educational Metaverse for Cyber–Physical Systems Engineering. Electronics 2024, 13, 3359.

- Sai,S.;Prasad, M.;Garg,A.;Chamola,V.;(2024) "Synergizing Digital Twins and Metaverse for Consumer Health: A Case Study Approach," in IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics, vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 2137-2144, Feb. 2024, .

- Tao,F.;Zhang,M.;Nee,A.Y.C.(2019) Digital Twin Driven Smart Manufacturing, Academic Press, Page iv,ISBN 9780128176306, .

- Adamenko,D.;Kunnen,S.;Pluhnau,R.;Loibl,A.;Nagarajah.,A; (2020) Review and comparison of the methods of designing the Digital Twin,Procedia CIRP, Volume 91, Pages 27-32, ISSN 2212-8271, . [CrossRef]

- Hosseini,S.;Abbasi,A.;Magalhaes,L.G.;Fonseca,J.C.;da Costa,N.M.C.;Moreira,A.H.J.;Borges,J. (2024) Immersive Interaction in Digital Factory: Metaverse in Manufacturing. Procedia Comput. Sci. 232, C (2024), 2310–2320. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kundu, P. (2022) Integrated cyber-physical systems and industrial metaverse for remote manufacturing. Manufacturing Letters. Vol 34. [CrossRef]

- Abdlkarim, D.;Di Luca, M.;Aves,P.(2024).A methodological framework to assess the accuracy of virtual reality hand-tracking systems: A case study with the Meta Quest 2.Behav Res 2024, Vol. 56 , 1052–1063.

- Tu,X.;Ala-Laurinaho,R.;Yang,C.;Autiosalo,J.;Tammi,K.(2024) Architecture for data-centric and semantic-enhanced industrial metaverse: Bridging physical factories and virtual landscape, Journal of Manufacturing Systems, Volume 74, 2024, Pages 965-979, ISSN 0278-6125, . [CrossRef]

- L. Ren et al., "Industrial Metaverse for Smart Manufacturing: Model, Architecture, and Applications," in IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 2683-2695, May 2024, .

- Patterson E.A.(2024) Engineering design and the impact of digital technology from computer-aided engineering to industrial metaverses: A perspective. The Journal of Strain Analysis for Engineering Design. 2024;59(4):303-305. [CrossRef]

- Kaigom,E.; 2024. Metarobotics for Industry and Society: Vision, Technologies, and Opportunities, IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, Vol, 20 , ISSN=1941-0050, .

- Fernández-Caramés, T.M.;Fraga-Lamas, P."Forging the Industrial Metaverse for Industry 5.0: Where Extended Reality, IoT, Opportunistic Edge Computing, and Digital Twins Meet," in IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 95778-95819, 2024, .

- Sai,S.;MPrasad,M.;Upadhyay,A,;Chamola,VHerencsar,V. "Confluence of Digital Twins and Metaverse for Consumer Electronics: Real World Case Studies," in IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics, vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 3194-3203, Feb. 2024, . [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Sharifi, A.; Bibri, S.E.; Jones, D.S.; Krogstie, J. The Metaverse as a Virtual Form of Smart Cities: Opportunities and Challenges for Environmental, Economic, and Social Sustainability in Urban Futures. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 771-801. [CrossRef]

- Zainab, H.e.;Bawanay,N. Z. "Digital Twin, Metaverse and Smart Cities in a Race to the Future," 2023 24th International Arab Conference on Information Technology (ACIT), Ajman, United Arab Emirates, 2023, pp. 1-8, .

- Gallist, N.; Hagler, J.Tourism in the Metaverse: Digital Twin of a City in the Alps. MUM ’23: Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia 2024, 568–570.

- Remolar, I.; Chover, M.;Quirós, R.;Gumbau, J.; Castelló, P.;Rebollo, C.;Ramos, J. F. Design of a Multiuser Virtual Trade Fair Using a Game Engine. Transactions on Computational Science 2011, Vol.12.

- Martín Ramallal,P.;Sabater-Wasaldúa,J.;Ruiz-Mondaza,M.(2022). Metaversos y mundos virtuales, una alternativa a la transferencia del conocimiento: El caso OFFF-2020. Fonseca, Journal of Communication, (24), 87–107.

- Valaskova,K.;Vochozka,M.;Lăzăroiu,G.(2022).“Immersive 3D Technologies, Spatial Computing and Visual Perception Algorithms, and Event Modeling and Forecasting Tools on Blockchain-based Metaverse Platforms,” Analysis and Metaphysics 21: 74–90.

- Zhu,H.(2022).A Metaverse Framework Based on Multi-scene Relations and Entity-relation-event Game. 2203.10424.

- Samarnggoon, K.; Grudpan, S.; Wongta, N.; Klaynak, K. Developing a Virtual World for an Open-House Event: A Metaverse Approach. Future Internet 2023, 15, 124. [CrossRef]

- Choi,M.;Choi,Y.;Nosrati,S.;Hailu,T. B.;Kim, S.(2023). Psychological dynamics in the metaverse: evaluating perceived values, attitude, and behavioral intention in metaverse events. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(7), 602–618. [CrossRef]

- Travassos,A.;Rosa,P.;Sales,F. Influencer Marketing Applications Within the Metaverse. Influencer Marketing in the Digital Ecosystem 2023 Vol. 82, 117–131.

- Bonales Daimiel,G.;Pradilla Barrero,N. Urban art in the metaverse.New creative spaces. Street Art and Urban Creativity 11, n.o 1 (2025): 137-50.

- Rafique,W.;Qadir,J.(2024). Internet of everything meets the metaverse: Bridging physical and virtual worlds with blockchain. Elsevier Science Publishers B. V.. Vol. 54.

- He, W;Li,X.;Xu,S.;Chen,Y.;Sio,C.;Kan,G.L.;Lee,L. (2024) MetaDragonBoat: Exploring Paddling Techniques of Virtual Dragon Boating in a Metaverse Campus. Association for Computing Machinery. Isbn 9798400706868.

- Barta,S.;Ibáñez-Sánchez,S.;Orús,C.;Flavián,C.(2024).” Avatar creation in the metaverse: A focus on event expectations”. Computers in Human Behavior. Vol 156. 108192.ISSN 0747-5632. [CrossRef]

- Ki,C.;Chong,S.;Aw,E.;Lam,M.; Wong, C. Metaverse consumer behavior: Investigating factors driving consumer participation in the transitory metaverse, avatar personalization, and digital fashion adoption. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2024, Vol. 82. 707 .

- Lau, J. X.;Ch’ng, C. B.;Bi, X.;Chan, J. H.(2024). Exploring attitudes of gen z towards metaverse in events industry. International Journal of Sustainable Competitiveness on Tourism, 3(01), 49–53. [CrossRef]

- Nesaif,B.M.R.B.(2024). The Influence of Virtual Events on Metaverse Commercial Real Estate Values: A Review. International Journal of Business Strategies, 9(1), 31–48.

- Lo,F.;Su,C.;Chen,C.(2024).Identifying Factor Associations Emerging from an Academic Metaverse Event for Scholars in a Postpandemic World: Social Presence and Technology Self-Efficacy in Gather.Town. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. Vol 27. ary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers.

- Flavián,C.;Ibáñez-Sánchez,S.;Orús,C.;Barta,S. (2024). “The dark side of the metaverse: The role of gamification in event virtualization”. International Journal of Information Management. Vol. 75. 102726, ISSN 0268-4012. [CrossRef]

- Singh,S., et al. "Role of Metaverse in Events Industry: An Empirical Approach." In New Technologies in Virtual and Hybrid Events, edited by Sharad Kumar Kulshreshtha and Craig Webster, 165-184. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2024.

- Mencarini,E.;Rapp,A.;Colley,A;Daiber,F.;Jones,M.D.;Kosmalla,F.;Lukosch,S.;Niess,J.;Niforatos,E.; Wozniak,P.W.;Zancanaro,M.;(2022). New Trends in HCI and Sports. Association for Computing Machinery.

- Chen,S.S.;Zhang,J.J.(2024). Market demand for metaverse-based sporting events: a mixed-methods approach. Sport Management Review, 28(1), 121–147. [CrossRef]

- Dolğun,O.C.;Gökören,V;Hakan,G.;Halime, D.;Argan, M.(2024) “Immersion In Metaverse Event Experience: A Grounded Theory”. Sportive 7, sy. 2 288-307.

- Kumari,V.;Bala,P.K.;Chakraborty,S. (2024). A text mining approach to explore factors influencing consumer intention to use metaverse platform services: Insights from online customer reviews. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. Vol 81. [CrossRef]

- Garcia,M;Quejado,C.K;Maranan,C.R.B.; Ualat,O;Adao;R. 2024. Valentine’s Day in the Metaverse: Examining School Event Celebrations in Virtual Worlds Using an Appreciative Inquiry Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Education and Multimedia Technology (ICEMT ’24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 22–29.

- Ramadan, Z. (2023) Marketing in the metaverse era: toward an integrative channel approach. Virtual Reality, Vol. 27, 1905–1918.

- Sahdev,S.L.et al. "An Analysis on the Future Usage of Metaverse in the Marketing Event Industry in India: An ISM Approach." In New Technologies in Virtual and Hybrid Events, edited by Sharad Kumar Kulshreshtha and Craig Webster, 147-164. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2024.

- Flores-Castañeda,R.O.;Olaya-Cotera,S.;Iparraguirre-Villanueva,O. (2024). Benefits of Metaverse Application in Education: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy (iJEP), 14(1), pp. 61–81. [CrossRef]

- Nleya,S.M.;Velempini,M. (2024) Industrial Metaverse: A Comprehensive Review, Environmental Impact, and Challenges. Appl. Sci., 14, 5736.

- Dhanda,M.;Rogers,B.A.; Hall,S.; Dekoninck,E.; Dhokia,V.; Reviewing human-robot collaboration in manufacturing:Opportunities and challenges in the context of industry 5.0,Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, Volume 93,2025,102937,ISSN 0736-5845, .

- Li, Z.;Jia, L. (2025). Bridging the Virtual and the Real: The Impact of Metaverse Sports Event Characteristics on Event Marketing Communication Effectiveness. Communication & Sport, 0(0).

- Kumar, A. "The Metaverse Touchdown Revolutionizing Sporting Events." Internationalization of Sport Events Through Branding Opportunities, edited by Jaskirat Singh Rai, et al., IGI Global, 2025, pp. 171-194.

- Singh,J.;Singh,R.;Singh,J.(2025) "The Sport Metaverse: A Deep Dive into the Transformation of Sports Events." In Internationalization of Sport Events Through Branding Opportunities, edited by Jaskirat Singh Rai, Maher N. Itani, and Amandeep Singh, 103-118. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Ingale,A.K., et al. "Technological Advances for Digital Twins in the Metaverse for Sustainable Healthcare: A Rapid Review." In Digital Twins for Sustainable Healthcare in the Metaverse, edited by Rajmohan R., et al., 77-106. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2025.

- Chaddad A.;Jiang Y.(2025) Integrating Technologies in the Metaverse for Enhanced Healthcare and Medical Education // IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies.Vol. 18. pp. 216-229.

- A. Nechesov, I. Dorokhov and J. Ruponen, "Virtual Cities: From Digital Twins to Autonomous AI Societies," in IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 13866-13903, 2025, .

- Pajani,M.;Safavi,A.;Shakibamanesh,A.;Adibhesami,M.A.;Sepehri,B. (2025). Augmented reality and digital placemaking: enhancing quality of life in urban public spaces. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 1–24.

- Sahraoui,Y.;Kerrache, C.A. (2025). Sensors and Metaverse-Digital Twin Integration: A Path for Sustainable Smarter Cities. In: Kerrache, C.A., Sahraoui, Y., Calafate, C.T., Vegni, A.M. (eds) Mobile Crowdsensing and Remote Sensing in Smart Cities. Internet of Things. Springer, Cham.

- Argota Sánchez-Vaquerizo, J. Urban Digital Twins and metaverses towards city multiplicities: uniting or dividing urban experiences?. Ethics Inf Technol 27, 4 (2025).

| Number | Question |

|---|---|

| IPQ1 | In the computer generated world I had a sense of “being there”. |

| IPQ2 | Somehow I felt that the virtual world surrounded me. |

| IPQ3 | I felt like I was just perceiving pictures. |

| IPQ4 | I did not feel present in the virtual space. |

| IPQ5 | I had a sense of acting in the virtual space, rather than operating something from outside. |

| IPQ6 | I felt present in the virtual space. |

| IPQ7 | How aware were you of the real world surrounding while navigating in the virtual world? (i.e., sounds, room temperature, other people, etc.)? |

| IPQ8 | I was not aware of my real environment. |

| IPQ9 | I still paid attention to the real environment. |

| IPQ10 | I was completely captivated by the virtual world. |

| IPQ11 | How real did the virtual environment seem to you? |

| IPQ12 | How much did your experience in the virtual environment seem consistent with your real world experience? |

| IPQ13 | How real did the virtual world seem to you? |

| IPQ14 | The virtual world seemed more realistic than the real world. |

| Number | Question |

|---|---|

| SUS1 | I think that I would like to use this system frequently. |

| SUS2 | I found the system unnecessarily complex. |

| SUS3 | I thought the system was easy to use. |

| SUS4 | I think that I would need the support of a technical person to be able to use this system. |

| SUS5 | I found the various functions in this system were well integrated. |

| SUS6 | I thought there was too much inconsistency in this system. |

| SUS7 | I would imagine that most people would learn to use this system very quickly. |

| SUS8 | I found the system very cumbersome to use. |

| SUS9 | I felt very confident using the system. |

| SUS10 | I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get going with this system. |

| Number | Type | Description of the question |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Qualitative | How has your navigation and interaction experience been? |

| 2 | Qualitative | Did you find easy to complete the missions? |

| 3 | Qualitative | Has the help from the guide and the ability to connect with other users been useful to you? |

| 4 | Qualitative | Were you able to complete the missions without external help? |

| 5 | Qualitative | What did you think of the application of the Digital Twin? |

| 6 | Quantitative | Did you find the experience useful? |

| 7 | Quantitative | Would you recommend the experience? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).