1. Introduction

Prostaglandins (PGs) are widely distributed in the central nervous system (CNS) and play diverse physiological functions. [

1]. PGs regulate not only inflammation, but also appetite, sleep-awake, and emotion [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) catalyzes phospholipids containing arachidonic acid, as a precursor for PG synthesis [

7,

8]. Recently, we reported that cPLA2-knockdown (KD) in the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1) neuron of mice fed a regular chew diet (RCD) leads to decreased insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle [

9]. This finding suggests that cPLA2 enhances systemic insulin sensitivity by activation of dmVMH glucose-excited (GE) neurons. Additionally, another study demonstrated that inhibition of PG synthesis by cyclooxygenase-1/2 (COX-1/2) inhibitors impairs the counter-regulatory response by suppressing glucagon sensitivity [

10]. In cPLA2-KD mice, cFos expression is specifically suppressed in the dorsomedial VMH (dmVMH). In contrast, in wild-type mice, intraperitoneal (i.p.) glucose administration increases cFos expression in the VMH and the arcuate nucleus (ARC) [

9]. These studies suggest that ARC neurons are regulated by PG, and thus, it is required to evaluate the function of PG-regulated neuronal activity in the hypothalamus on energy homeostasis.

The regulation of the CNS in the termination of feeding after a meal is complex and involves multiple mechanisms. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in the hypothalamus mediates the anorexigenic and thermogenic effects of leptin, suppressing food intake and increasing sympathetic outflow to brown adipose tissue [

11]. ERK in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), activated by the gut-derived satiety signal cholecystokinin (CCK), also plays a crucial role in suppressing food intake [

12]. The melanocortin receptor (MC4R) agonist MTII also increases p-ERK in the NTS, suppressing food intake [

13]. Cyclic AMP (cAMP)- response element binding protein (CREB) is a transcription factor that is regulated by ERK. In the NTS, cAMP-ERK-CREB cascade may serve as a molecular integrator for converging satiety signals from the gut and adiposity signals from the hypothalamus [

14]. CREB targets COX-2 expression, which is crucial for prostaglandin (PG) synthesis [

15]. However, the relationship between insulin-induced ERK signaling and PG synthesis, particularly in regulating hyperphagia, remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate the role of hypothalamic PG in the development of hyperphagia. We found that cPLA2-KD in the hypothalamus of RCD-fed wild-type mice resulted in a significant increase in food intake, leading to a body weight gain of approximately 5 g within three weeks. Our findings suggest that cPLA2 in the hypothalamus is necessary for terminating feeding by regulating hypothalamic neuronal activity in response to insulin-ERK signaling.

2. Results

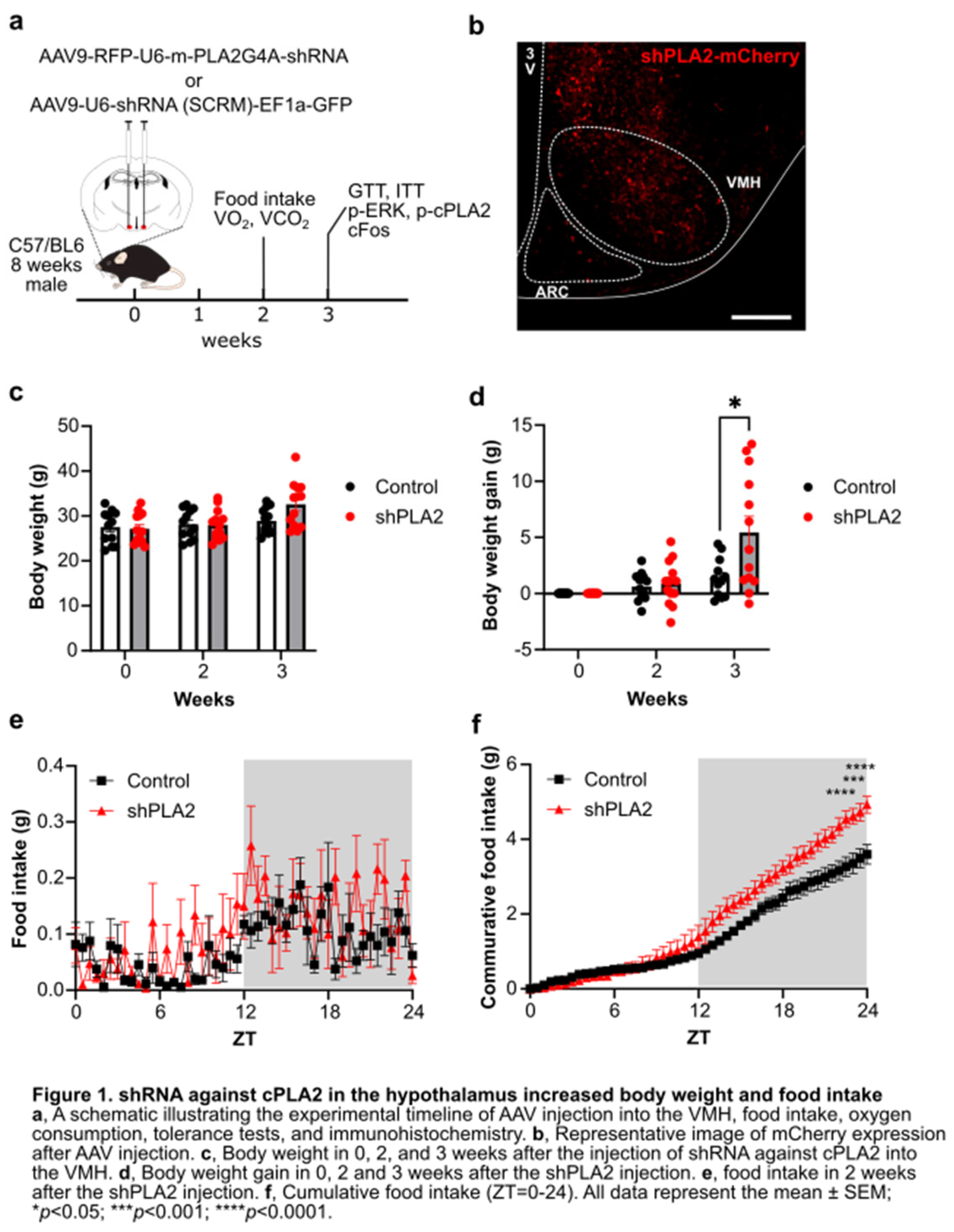

To knock-down PLA2g4a gene expression, we injected AAV9-RFP-U6-m-PLA2G4A-shRNA or AAV9-U6-shRNA (SCRM)-EF1a-GFP bilaterally in the VMH of C57BL mice (

Figure 1a). mCherry or GFP derived from viral vectors were found in both the VMH and ARC, suggesting that AAV successfully infected the hypothalamus (Figure b). Body weight of shPLA2 mice was comparable to that of shSCRM mice at two weeks after AAV injection, but it tended to increase at three weeks post-AAV injection (

Figure 1c). Importantly, when we calculate weight gain, shPLA2 mice increased weight gain compared to shSCRM mice at three weeks (

Figure 1d). Furthermore, food intake was significantly higher in shPLA2 mice at two weeks post-AAV injection (

Figure 1e-g).

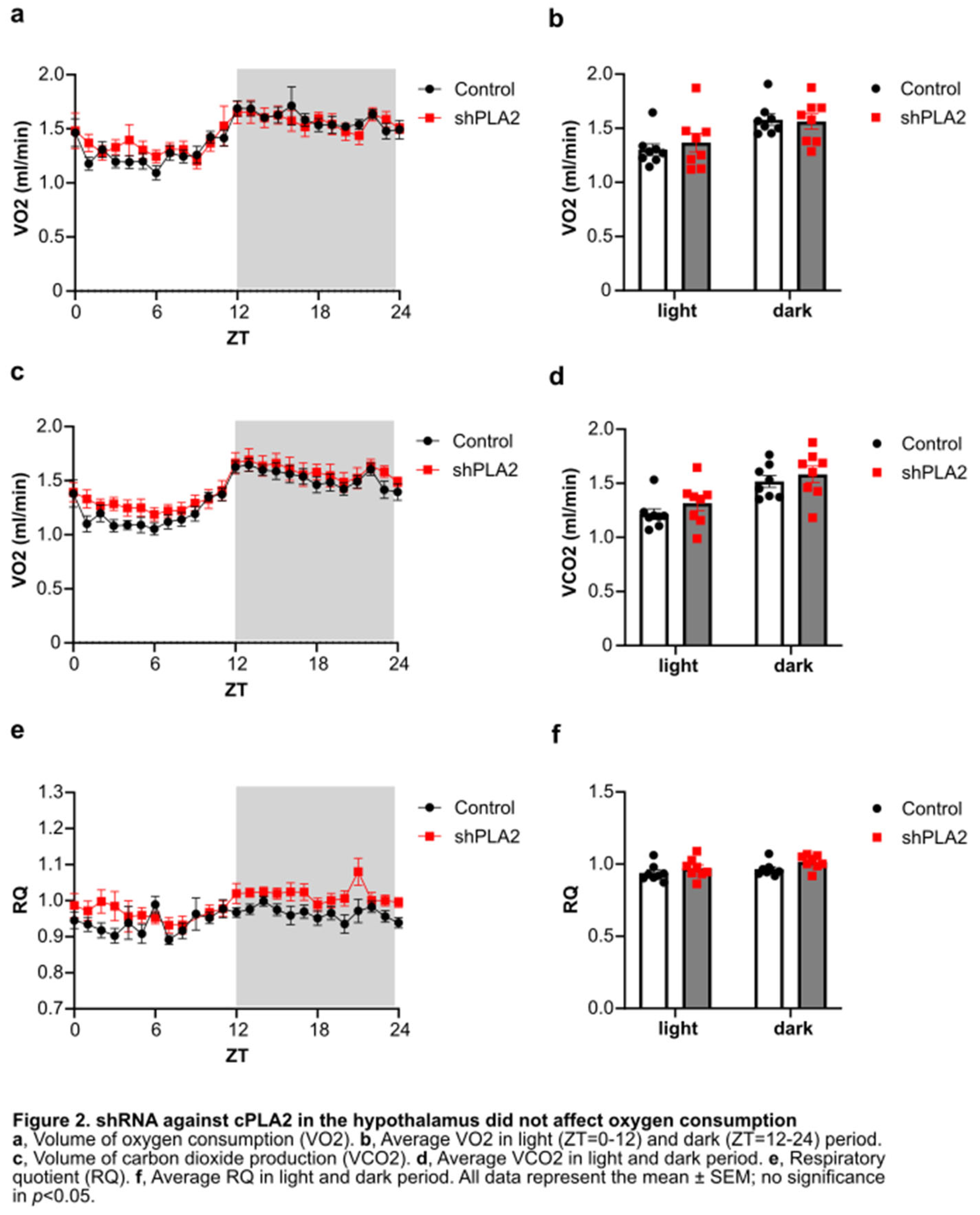

We next examined oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and the respiratory quotient (RQ) using an in vivo calorimetry system. However, these parameters did not differ between the shPLA2 and control groups (

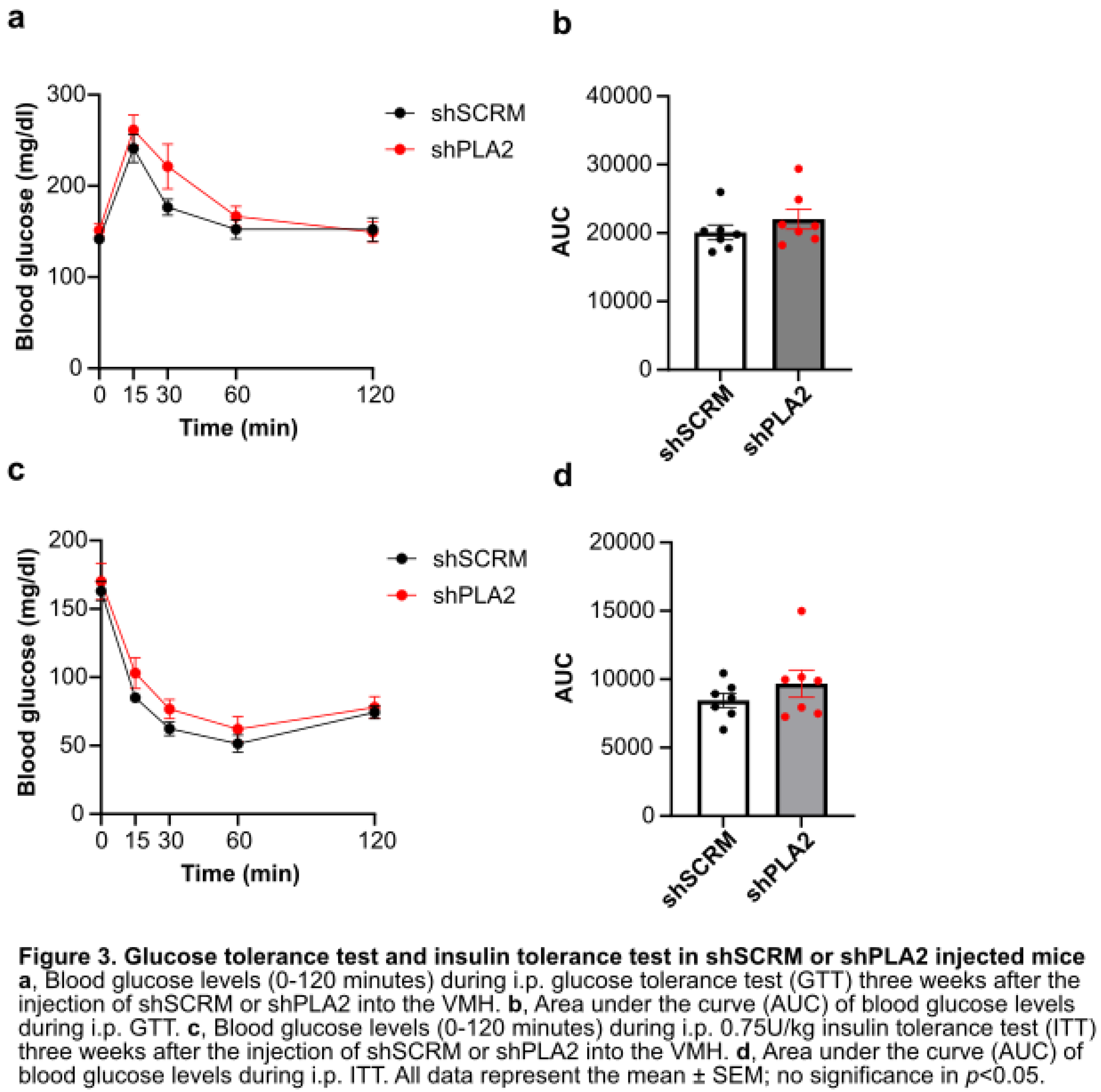

Figure 2a-f). In addition, hypothalamic shPLA2 did not affect glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity at three weeks post-AAV injection (

Figure 3a, b).

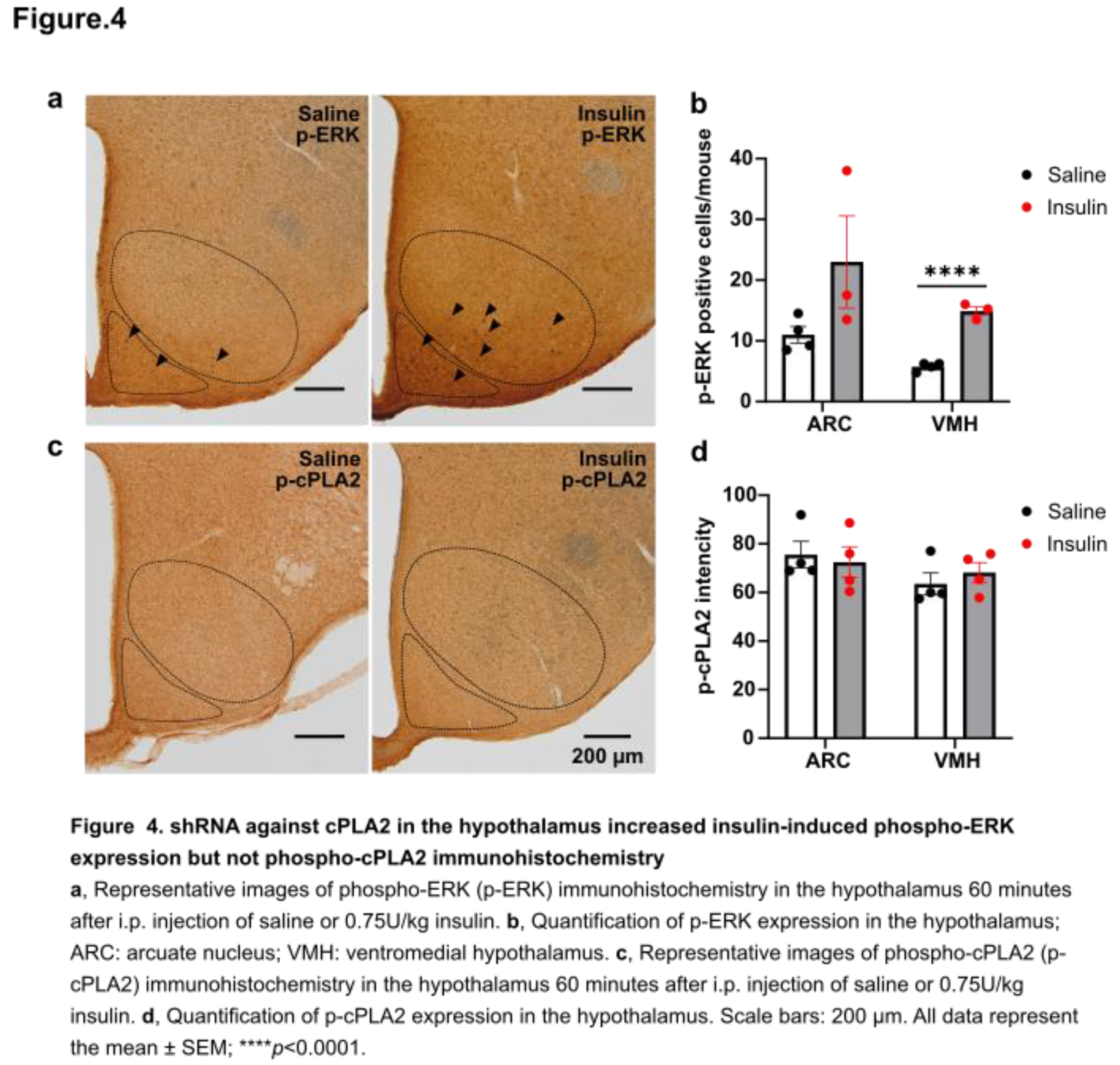

To evaluate the effect of insulin on the neuronal activation modulated by ERK signaling, we performed immunohistochemical staining for phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK (p-ERK1/2) in the hypothalamus following insulin injection (

Figure 4a). Sixty minutes after insulin i.p. administration, p-Erk expression in the VMH was significantly higher than in the saline-treated control group (

Figure 4b). In contrast, while p-Erk expression in the ARC showed a trend toward an increase, the difference was not statistically significant (

Figure 4c). Given that insulin administration enhances PG production in the hypothalamus in our recent finding [

10], we also performed immunohistochemical staining for phosphorylated cPLA2 (p-cPLA2) in the hypothalamus of these mice (

Figure 4d). Although the mean intensity of p-cPLA2 staining tended to increase after insulin injection in the VMH and ARC, no significant differences were observed between groups (

Figure 4e, f).

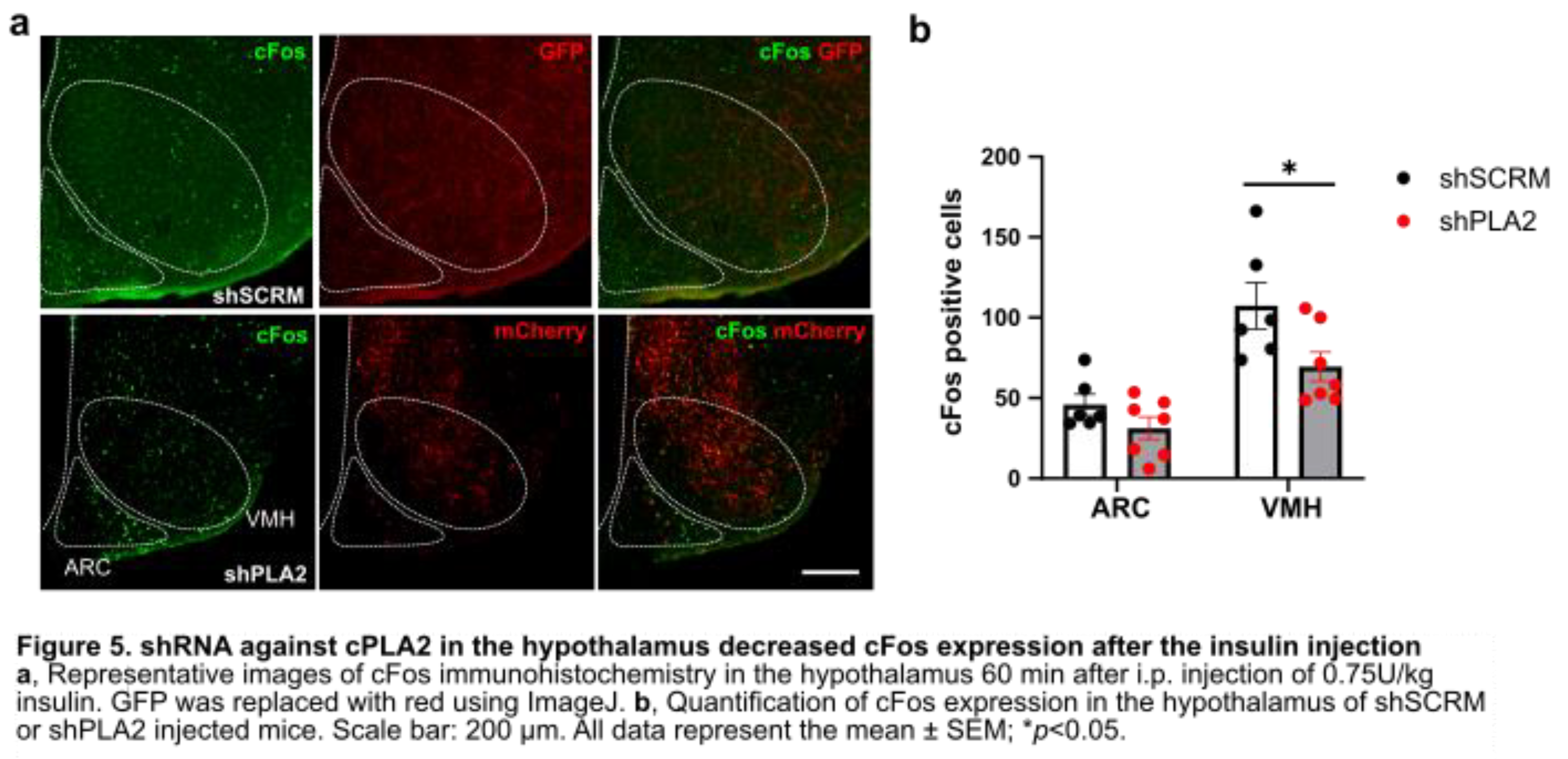

We also analyzed the effect of cPLA2-KD on the insulin-induced cFos expression in the hypothalamic nuclei. cFos immunohistochemical staining was performed in the hypothalamus 60 minutes after insulin administration in both shPLA2 and shSCRM groups (

Figure 5a). cFos expression was significantly reduced in the VMH of shPLA2 mice (

Figure 5b). cFos expression in the ARC tended to decrease in shPLA2 mice, but it was not significant (

Figure 5b).

3. Discussion

In the present study, the suppression of hypothalamic prostaglandin production by shRNA targeting cPLA2 resulted in short-term weight gain, accompanied by increased food intake. During this period, indirect calorimetry showed no differences in VO2 or VCO2, indicating that basal metabolism remained unchanged following hypothalamic shPLA2 injection. Additionally, RQ was unaffected, suggesting no alteration in metabolic substrate utilization. However, food intake becomes significantly higher in the shPLA2-injected group compared to controls two weeks after injection, suggesting that the neuronal activity regulating appetite may have changed.

In the VMH, i.p. insulin injection enhanced ERK phosphorylation but did not affect cPLA2 phosphorylation. Insulin has direct and indirect effects on the regulation of food intake. Insulin suppresses appetite directly via neuronal pathways [

16]. Postprandial hyperinsulinemia also affects cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) insulin levels [

12]. In rats, glucose infusion and refeeding resulted in elevated CSF insulin [

12,

17]. These findings suggest that peripheral insulin can reach the CNS and regulate food intake and body weight. Insulin treatment increases ERK1/2 expression in hypothalamic cells in vitro [

18]. Short-term fasting also increases p-ERK1/2 levels in the hypothalamus, partially mediated by centrally produced insulin [

19]. Enhanced ERK1/2 activity, achieved through deletion of its phosphatases DUSP6/8, leads to resistance to diet-induced obesity, improved glucose tolerance, and reduced serum triglycerides and lipid content in the liver and visceral adipose tissues [

20]. In hypothalamic neurons, ERK1/2 mediates glucose-regulated POMC gene expression, influencing metabolic homeostasis [

21]. These studies indicate that ERK activation by diet, blood glucose, and insulin is involved in both the improvement and worsening of metabolic-related diseases. Future research will need to examine hypothalamic p-ERK-positive neuron types to elucidate their relationship with feeding suppression.

According to previous reports, CREB regulates COX-2 activity [

15,

22]. A previous study has shown that SF1 neuron-specific deletion of CRTC1, a co-activator of CREB, leads to hyperphagia in mice fed a high-fat diet [

23]. The authors recently reported that inhibition of the PG production pathway using the COX inhibitor ibuprofen suppressed insulin-induced cFos expression in the vlVMH [

10]. In the present study, shPLA2 in the hypothalamus also reduced cFos-positive cells in the VMH after i.p. insulin injection. This result suggests that decreased arachidonic acid, a product of the ERK-CREB-COX pathway, may have suppressed PG-regulated neuronal activity in the hypothalamus. In this study, insulin injection did not change phosphorylation of cPLA2 in the hypothalamus. Thus, insulin may affect PG production via COX, but not cPLA2 activity. VMH neurons projecting to ARC-POMC neurons are essential for suppressing food intake [

24]. In line with this, cFos in the ARC tended to decrease in shPLA2 mice, suggesting that POMC activity was decreased. Therefore, our findings suggest that cPLA2-regulated PG synthesis in the VMH is essential for feeding termination via POMC neurons, as its knockdown resulted in increased food intake and body weight gain.

PGs play a crucial role in metabolic control and appetite regulation. cPLA2 is crucial in generating arachidonic acid from phospholipids for PG synthesis [

25]. In the CNS, PGs have diverse effects on food intake. Centrally administered PGE2 suppresses food intake via the EP4 receptor, whereas PGD2 increases food intake through the DP1 receptor, which is coupled to the Y1 receptor of neuropeptide Y [

6]. Our previous study also highlighted that cPLA2-mediated hypothalamic phospholipid metabolism is critical for controlling systemic glucose metabolism under a regular chow diet [

9].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the critical role of SF1 neurons in the VMH in regulating feeding behavior. The deletion of leptin receptors in VMH-SF1 neurons leads to diet-induced obesity [

26]. The loss of insulin receptors in SF1 neurons suppresses weight gain under a high-fat diet by inhibiting phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling, which is involved in insulin secretion [

27]. Furthermore, the deletion of PI3 phosphatase in SF1 neurons induces excessive PI3K activation in the VMH, leading to hyperphagia and weight gain even under a regular-chow [

27]. Additionally, chemogenetic inhibition of SF1 neurons using DREADDs enhances appetite and increases food intake [

28]. These studies collectively suggest that hyperphagia and subsequent weight gain result from changes in the activity of VMH SF1 neurons, which are regulated by humoral factors involved in postprandial feeding suppression.

In this study, we demonstrated that hypothalamic cPLA2-KD induces obesity in a short period through increased food intake. During this process, cPLA2-KD suppressed the release of arachidonic acid, a substrate for PG production regulated by the ERK-CREB-COX pathway during postprandial hyperinsulinemia. Since obesity in this study resulted solely from increased food intake without peripheral metabolic changes, it is possible that feeding suppression, mediated by the activation of ARC-POMC neurons and regulated by PGs, was impaired. Although further studies are needed, this study advances knowledge in the regulation of systemic metabolism mediated by the PG synthesis pathway. This finding provides a novel therapeutic target for obesity treatment.

4. Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6N male mice (Japan SLC, Shizuoka, Japan) were housed at room temperature with a 12-hour light and 12-hour dark cycle. The mice had free access to water and a regular chow diet (CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Experiments were conducted in the Experimental Animal Facility at Kumamoto University. Mice cages were changed once a week, and mouse care was performed according to the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee at Kumamoto University.

Cannula Implantation and Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Injection

C57BL male mice were anesthetized with a combination of anesthetics (0.3 mg/kg medetomidine, 4.0 mg/kg midazolam, and 5.0 mg/kg butorphanol). The mice were placed on the stereotaxic instrument (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). A hole in the skull was opened with a dental drill. A stainless-steel cannula (Plastics One, P1 Technologies, VA, USA) was inserted into the VMH using the following coordinates: an anterior-posterior (AP) direction; −1.5 (1.5 mm posterior to the bregma), lateral (L): ±0.4 (0.4 mm lateral to the bregma), dorsal-ventral (DV): −5.7 (5.7 mm below the bregma on the surface of the skull). For intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection, the coordinates are as follows: AP: -0.3, L: 1.0, DV: −2.0. Cannulae were secured on the skulls with cyanoacrylic glue, and the exposed skulls were covered with dental cement. For AAV injection, the mice were injected in both sides of the VMH with a maximum of 0.3 µL AAV9-RFP-U6-m-PLA2G4A-shRNA (1.0x1012 GC/mL, shAAV-268768, Vector Biolabs, PA, USA) or AAV9-U6-shRNA (scrumble, SCRM)-EF1a-GFP (1.0x1012 GC/mL, SL100894, Signagen Laboratories, MD, USA) using the following coordinates: AP: − 1.5, L: ± 0.5, DV: − 5.7. Open wounds were sutured after the viral injection. The mice were allowed to recover for 5–7 days before the experiments began.

Body Weight Gain, Food Intake, and Oxygen Consumption

To evaluate the effects of hypothalamic cPLA2-KD on body weight and food intake, we compared food intake between the control and shPLA2 groups two weeks after AAV administration. Mice were placed in food intake measurement cages (cFDM-300AS, Melquest, Toyama, Japan) and habituated for 24 h, followed by food intake measurement from ZT 0 to 24. Indirect calorimetry data from mice injected with shPLA2 or shSCRM were measured using an indirect calorimetry system (MK-5000RQ/MS, Muromachi Kikai, Fukuoka, Japan). Mice were acclimated to the measurement chambers for one day prior to data collection.

p-ERK and p-cPLA2 Immunohistochemistry

C57BL/6 male mice received an i.p. injection of saline or insulin (0.75 U/kg). The mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with heparinized saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde transcardially 60 minutes after the i.p. injection. Brain sections (50 µm each) containing both VMH and ARC were collected. The floating sections were incubated in 1% H2O2 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) for 15 min at room temperature (RT) to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity. After rising with PB, the sections were incubated with rabbit-anti-pErk antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4370S, MA) or rabbit-anti-pCpla2 antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #2831S, MA) in blocking solution (0.1 M PB containing 4% normal horse serum, 0.1% glycine, and 0.2% Triton X-100) overweekend at room temperature. After rinsing with PB, the sections were incubated in a secondary antibody (1:500, Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, Vector lab, BA-1000, CA) for two hours at room temperature. After rinsing with PB, sections were incubated with ABC solution (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit, Peroxidase, Vector Laboratories, CA) for 2 hours at room temperature. The sections were rinsed with PB and incubated with DAB solution (DAB tablet, Wako, Japan) for 20 min at room temperature. The stained sections were rinsed with PB and mounted using Mount-Quick (Daido Sangyo, Japan). Cells were automatically counted using the ImageJ software plugin (Analyze Particles).

cFos Immunohistochemistry

C57BL/6 male mice received a shPLA2 or shSCRM injection 4 weeks before the i.p. injection of insulin (0.75 U/kg). The mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with heparinized saline transcardially 60 minutes after insulin injection. Brain sections (50 µm each) containing both VMH and ARC were collected. After rising with PB, the sections were incubated with rabbit-anti-cFos antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #2250S, MA) in blocking solution (0.1 M PB containing 4% normal horse serum, 0.1% glycine, and 0.2% Triton X-100) overnight at room temperature. After rinsing with PB, the sections were incubated in a secondary antibody (1:500, Alexa 488 secondary antibody, Invitrogen, A11008, MA) or (1:500, Alexa 594 secondary antibody, Cell Signaling Technology, 8889S, MA) for two hours at room temperature. The stained sections were washed three times with PB and then mounted on glass slides using DAPI Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Cells were automatically counted using ImageJ.

Statistical Analysis

For repeated-measures analysis, a two-way ANOVA was used to analyze values over different time points, followed by the Sidak multiple comparisons test. For the statistical analysis of multiple independent groups, one-way ANOVA was followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. When only two groups were analyzed, statistical significance was determined by the unpaired Student’s t-test (two-tailed p-value). Prism 10 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for these statistical analyses. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are shown as mean ± SEM.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that cPLA2-KD in the VMH induces obesity solely through increased food intake. cPLA2-KD suppressed the production of eicosanoids from membrane phospholipids and inhibited the synthesis of PGs during postprandial hyperinsulinemia, which may be essential for regulating neuronal activity in the VMH. Inhibition of VMH neurons resulted in hyperphagia, possibly via POMC neurons in the ARC.

Author Contributions

T.A. and C.T. conceived this study, designed the experiments, and supervised the entire study. T.A., T.I., Y.A., Z.N., C.L., J.H., and N.S. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. T.A. and C.T. wrote the manuscript. T.I. and Y.A. assisted in preparing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 21H02352, 21K18275T, 23H00512); Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED-RPIME, Grant Number JP21gm6510009h0001, JP22gm6510009h9901, 23gm6510009h9903, 24gm6510009h9904); the Takeda Science Foundation; the Uehara Memorial Foundation; Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders; Suzuken Memorial Foundation; Akiyama Life Science Foundation; Narishige Neuroscience Research Foundation; and Daiichi Sankyo Foundation of Life Science.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| cPLA2 |

cytosolic phospholipase A2 |

| SCRM |

scrumble |

| VMH |

ventromedial hypothalamus |

| PGs |

Prostaglandins |

| CNS |

central nervous system |

| KD |

knockdown |

| COX |

cyclooxygenase |

| dm |

dorsomedial |

| ARC |

arcuate nucleus |

| ERK |

extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| NTS |

nucleus tractus solitarius |

| CCK |

cholecystokinin |

| |

|

| |

|

References

- Narumiya S, Furuyashiki T. Fever, inflammation, pain and beyond: prostanoid receptor research during these 25 years. The FASEB Journal. 2011 Mar;25(3):813–8. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1096/fj.11-0302ufm. [CrossRef]

- Pecchi E, Dallaporta M, Thirion S, Salvat C, Berenbaum F, Jean A, et al. Involvement of central microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 in IL-1-induced anorexia. Physiol Genomics. 2006;25:485–92. Available from: www.physiolgenomics.org. [CrossRef]

- Hayaishi O. Molecular mechanisms of sleep–wake regulation: a role of prostaglandin D2. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000 Feb 29;355(1394):275–80. Available from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2000.0564. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka Y, Furuyashiki T, Yamada K, Nagai T, Bito H, Tanaka Y, et al. Prostaglandin E receptor EP1 controls impulsive behavior under stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005 Nov 24;102(44):16066–71. Available from: https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0504908102. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka K, Furuyashiki T, Kitaoka S, Senzai Y, Imoto Y, Segi-Nishida E, et al. Prostaglandin E 2-mediated attenuation of mesocortical dopaminergic pathway is critical for susceptibility to repeated social defeat stress in mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012 Mar 21;32(12):4319–29. [CrossRef]

- Ohinata K, Yoshikawa M. Central prostaglandins in food intake regulation. Nutrition. 2008 Sep;24(9):798–801. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0899900708002773. [CrossRef]

- Sapirstein A, Bonventre J V. Specific physiological roles of cytosolic phospholipase A2 as defined by gene knockouts. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2000 Oct;1488(1–2):139–48. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1388198100001165. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, AI. Prostaglandin E2 as a mediator of fever: synthesis and catabolism. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2004;9(1–3):1977. Available from: https://imrpress.com/journal/FBL/9/3/10.2741/1383. [CrossRef]

- Lee ML, Matsunaga H, Sugiura Y, Hayasaka T, Yamamoto I, Ishimoto T, et al. Prostaglandin in the ventromedial hypothalamus regulates peripheral glucose metabolism. Nat Commun. 2021 Dec 1;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Abe T, Xu S, Sugiura Y, Arima Y, Hayasaka T, Lee ML, et al. Hypothalamic prostaglandins facilitate recovery from hypoglycemia but exacerbate recurrent hypoglycemia in mice. 2024. bioRxiv. Available from: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2024.06.24.600540. [CrossRef]

- Rahmouni K, Sigmund CD, Haynes WG, Mark AL. Hypothalamic ERK Mediates the Anorectic and Thermogenic Sympathetic Effects of Leptin. Diabetes. 2009 Mar 1;58(3):536–42. Available from: https://diabetesjournals.org/diabetes/article/58/3/536/13507/Hypothalamic-ERK-Mediates-the-Anorectic-and. [CrossRef]

- Sutton GM, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 Signaling Pathway in Solitary Nucleus Mediates Cholecystokinin-Induced Suppression of Food Intake in Rats. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004 Nov 10;24(45):10240–7. Available from: https://www.jneurosci.org/lookup/doi/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2764-04.2004. [CrossRef]

- Sutton GM, Duos B, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. Melanocortinergic Modulation of Cholecystokinin-Induced Suppression of Feeding through Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Signaling in Rat Solitary Nucleus. Endocrinology. 2005 Sep 1;146(9):3739–47. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/endo/article/146/9/3739/2500039. [CrossRef]

- Berthoud HR, Sutton GM, Townsend RL, Patterson LM, Zheng H. Brainstem mechanisms integrating gut-derived satiety signals and descending forebrain information in the control of meal size. Physiol Behav. 2006 Nov 30;89(4):517–24. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0031938406003714. [CrossRef]

- Sun H, Xu B, Inoue H, Chen QM. p38 MAPK mediates COX-2 gene expression by corticosterone in cardiomyocytes. Cell Signal. 2008 Nov;20(11):1952–9. [CrossRef]

- Biddinger SB, Kahn CR. FROM MICE TO MEN: Insights into the Insulin Resistance Syndromes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006 Jan 1;68(1):123–58. Available from: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.124723. [CrossRef]

- Steffens AB, Scheurink AJ, Porte D, Woods SC. Penetration of peripheral glucose and insulin into cerebrospinal fluid in rats. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 1988 Aug 1;255(2):R200–4. Available from: https://www.physiology.org/doi/10.1152/ajpregu.1988.255.2.R200. [CrossRef]

- Fick LJ, Cai F, Belsham DD. Hypothalamic Preproghrelin Gene Expression Is Repressed by Insulin via Both PI3-K/Akt and ERK1/2 MAPK Pathways in Immortalized, Hypothalamic Neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;89(3):267–75. Available from: https://karger.com/NEN/article/doi/10.1159/000167698. [CrossRef]

- Dakic T, Jevdjovic T, Djordjevic J, Vujovic P. Short-term fasting differentially regulates PI3K/AkT/mTOR and ERK signalling in the rat hypothalamus. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020 Dec 1;192:111358. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0047637420301548. [CrossRef]

- Liu R, Peters M, Urban N, Knowlton J, Napierala T, Gabrysiak J. Mice lacking DUSP6/8 have enhanced ERK1/2 activity and resistance to diet-induced obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020 Nov 26;533(1):17–22. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zhou Y, Chen C, Yu F, Wang Y, Gu J, et al. ERK1/2 mediates glucose-regulated POMC gene expression in hypothalamic neurons. J Mol Endocrinol. 2015 Apr 26;54(2):125–35. Available from: https://jme.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/jme/54/2/125.xml. [CrossRef]

- Fujimori K, Yano M, Miyake H, Kimura H. Termination mechanism of CREB-dependent activation of COX-2 expression in early phase of adipogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014 Mar 25;384(1–2):12–22. [CrossRef]

- Matsumura S, Ishikawa F, Sasaki T, Terkelsen MK, Ravnskjaer K, Jinno T, et al. Loss of CREB Coactivator CRTC1 in SF1 Cells Leads to Hyperphagia and Obesity by High-fat Diet But Not Normal Chow Diet. Endocrinology. 2021 Sep 1;162(9). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/endo/article/doi/10.1210/endocr/bqab076/6224280. [CrossRef]

- Sternson SM, Shepherd GMG, Friedman JM. Topographic mapping of VMH → arcuate nucleus microcircuits and their reorganization by fasting. Nat Neurosci. 2005 Oct 18;8(10):1356–63. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nn1550. [CrossRef]

- Leslie, CC. Properties and Regulation of Cytosolic Phospholipase A2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997 Jul;272(27):16709–12. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0021925818392780. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon H, Zigman JM, Ye C, Lee CE, McGovern RA, Tang V, et al. Leptin Directly Activates SF1 Neurons in the VMH, and This Action by Leptin Is Required for Normal Body-Weight Homeostasis. Neuron. 2006 Jan 19;49(2):191–203. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0896627305011347. [CrossRef]

- Klöckener T, Hess S, Belgardt BF, Paeger L, Verhagen LAW, Husch A, et al. High-fat feeding promotes obesity via insulin receptor/PI3K-dependent inhibition of SF-1 VMH neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2011 Jul 5;14(7):911–8. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nn.2847. [CrossRef]

- Viskaitis P, Irvine EE, Smith MA, Choudhury AI, Alvarez-Curto E, Glegola JA, et al. Modulation of SF1 Neuron Activity Coordinately Regulates Both Feeding Behavior and Associated Emotional States. Cell Rep. 2017 Dec 19;21(12):3559–72. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2211124717317564. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).