1. Introduction

Designers and developers of digital tools strive to find common ground with the subsequent users of these technologies so they can create products that people can make use of and therefore find a market. Sometimes, however, this comes about not so much through innovation and careful planning, but as a side-effect, and in an ad-hoc manner [

1].

This is not always a problem, since ‘survival of the fittest ideas’ [

2] ensures that those digital tools that people find worthy of use will more likely be selected and thus propagate, with their design language becoming the basis for subsequent tools [

3]. However, other imperatives can create fitness functions [

4] that are not beneficial from a human usability perspective, resulting in digital tools that become accepted, but do not necessarily work well with the intended audience. Two examples are QWERTY keyboards and entertainment device remote controls. The first was developed to ensure mechanical typewriters did not stick (or possibly for other reasons such as Morse Code) [

5] and then became the standard even after these considerations no longer applied, whilst the second seems to have emerged from early ergonomic designs that may no longer match current usage patterns [

6]. Fitness functions that prioritize financial gain or design convenience over user fit may cause sub-optimal design decisions to be made. At best, this is annoying, but at worst, life-threatening [

7].

Right now, we are seeing a paradigm shift in how people relate to digital technologies. Innovations such as Spatial Computing and Mixed Reality glasses are changing our focus from a device screen held in the hand, to the world around us as perceived through special glasses, anchoring the digital user interface onto the physical realm. Further, generative AI Large Language Models (LLMs) are changing how we interact with and direct digital tools. We are familiar with having to ‘be the brains’ in charge of the devices around us, communicating through precise commands. Now we are becoming able to not only pass some of that control over to an ‘intelligent other’ but communicate our desires in somewhat loose natural language.

Nevertheless, the tools being created today with these technologies are not just evolving by themselves, they are directed and created by teams of people. We can see this in the large investments by the likes of Apple, Meta, and OpenAI [

8]. This capability is slowly diffusing to a larger audience of designers and developers as Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and Software Development Kits (SDKs) become available. Therefore, as creators with this expanded toolbox, it behooves us to take advantage of this paradigm shift and push for a fitness function that prioritizes use-worthiness to create adaptive, assistive technologies that enhance and understand human foibles and capabilities in the best way possible.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. First, we review some core concepts including Calm Technology and latent bias of design. We then discuss areas of cognitive science related to metaphor building and locus of mind, proposing an ‘Objects and Actors’ metaphor as a design language on which to anchor and direct thinking and decision-making in this potentially wonderful new world of technological innovation. Finally, we consider an implementation (’Reality2‘) that rethinks the way digital technologies interact with humans and each other based on semi-embodied autonomous digital agents (’Sentants’).

2. Extended and Extending Reality

When Virtual Reality (VR) was going through its first growth spurt in the ‘90s, we contemplated how this wonderous new tool would transform society [

9]. The terms Augmented or Mixed Reality on the other hand, weren’t used much; it was all just ‘VR’, but it was always assumed that the virtual and real worlds would interplay or ‘mix’ in the virtuality continuum [

10]. One of the first Mixed Reality systems as we know it today appeared in the early 2000’s [

11], and it was there that we learned how using physical objects as an interface to a digital realm was natural and highly intuitive. It is this overlap and interplay between the physical world and information layers, adapted contextually, that led to wearable computing and devices like Google Glass [

12].

With this digital overlay extending and enhancing the real world, we get the term ‘eXtended Reality’ or XR. Often, though, the terms Augmented, Mixed and Extended Reality are interchanged. Most importantly, people’s behaviours are location, time and context dependent, which in turn defines the information they require at that moment, in that place.

For example, during my commute, I may want to brush up on my language learning, read the latest news, check my social media or listen to music, perhaps. At the supermarket, I need to check my shopping list and then make a payment. At work, I need to remove distractions such as social media but have access to the repair manuals of the machinery I maintain. When on holiday with my family, I want to know how to get to the hotel, and what there is to do.

The way we manage this today is through general-purpose devices such as mobile phones, tablets and computers that we must first adapt or set up for that moment before we can use them. This may require establishing a connection, authenticating, starting a specific App and choosing a dataset or context. Doing this again and again as we go through our days wastes much time and effort, not to mention the issues with recalling authentication details, which Apps to use, or where data is stored.

This need to regularly pay attention to such detail spoils the illusion of ‘the Invisible Computer’ [

13]. Another technology that has become invisible, in that we are not often aware of it, is the electric motor. Imagine if each time we needed to use one, we had to connect wires, set the voltage and adjust the switches – it would be frustrating and waste time, however, this is how many computer applications today behave.

What if all that could be automated, with your devices bringing exactly the right App and data to you when required, pre-authenticated? This leads to the next topic: designing tools using the principles of Calm Technology.

3. Calm Technology

The other day, I wanted to transfer a document from my laptop to an e-reader for more convenient perusal. In the futuristic world of technology inspiration videos [

14], I’d be able to just drag it across with a flick of my hand. In reality, I had to try to connect both devices to a local Wi-Fi, get through authentication; and then find some App compatible with both that would allow the transfer. Often, in this situation, emailing it to oneself is the easiest option - which is hardly intuitive and far from a simple hand gesture.

Digital technologies today still require considerable understanding of the underlying processes to achieve just simple tasks. In other words, they are generally not ‘calm’ technologies that can communicate in human ways using natural affordances, nor are they (with some exceptions) particularly adaptive to changing circumstances.

Even without knowing the intricacies, the concept that technologies may be designed to be calming rather than the opposite resonates with many people. When asking students in a lecture to describe technologies that frustrate them, there is never any shortage of material.

The seminal work on calm technologies, originally published in 1995 by Mark Weiser and John Seely Brown [

15,

16] at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (Xerox PARC), provides a roadmap for would-be technology creators. At about the same time and place, the Desktop Metaphor was developed [

17], and whilst the latter has persisted to this day even in mobile devices and Virtual Reality interfaces, Calm Technology is still a relatively unknown concept, though related topics such as user-centered design are well explored. Interest in it, however, persists, and it may offer new insights into how we could design systems for today’s extended reality environments.

One core technique of calm technologies is to move less-important information from the center of attention to the periphery and bring it back only when required. This increases our knowledge and thus our ability to act without increasing information overload. The result of calm technology is that we are connected to the world around us - “located” - tuned into what is happening and what is going to happen. As ubiquitous multi-media technologies continued to develop in the decade after Calm Computing was proposed, they provided further opportunities for technology to fade into the background of our environments and easily switch between the center and the periphery of our attention [

18]. Indeed, some experiments addressed physically moving Web 2.0 social media events into the periphery using unobtrusive hardware devices [

19]. The more recent emergence of the Internet of Things (IoT) has further emphasized the potential of technologies that become an invisible part of the background [

20]. Ideally, every data object will be capable of displaying more information as needed, disappearing when not needed, and accepting user commands to help with the thinking processes [

21].

It follows, therefore, that technologies should not be designed with a one-size-fits-all mindset. Ideally, autonomous components of such systems should be able to adapt using self-learning, so they become less intrusive to the user and therefore more calming over time [

22].

4. Latent Bias of Design

Latent errors in the design process are those that remain concealed until a particular combination of circumstances exposes them [

23] and may emerge over time as a consequence of how systems adapt and are used. These are a significant challenge both for human designers and in AI systems [

24]. Drawing from these ideas we use the term ‘latent bias of design’ to describe how our usually unconscious human biases lead to decisions that will exclude a section of the population from using that tool. A classic example is the design of websites that require the user to have good vision and are unintelligible to screen readers.

This bias becomes part of the design language connecting designers and users, with the result that design decisions we make as creators of tools and technologies may have long-term consequences on events in the future. In extreme cases, latent biases cause tools to be created that have the potential to hurt people and threaten life. These will become dangerous if they are not designed to deal with emergency situations in a way that compensates for how human perception, cognition and decision-making under duress is negatively impacted and reduced; the so-called tunnel-vision effect [

7] driven by our fight-or-flight response to stressful events. In those situations, the partnership between human and machine, and the concepts embodied by calm technology become critical. To compensate, the tool could, for example, simplify the complexity of the decisions to be made by the human operator, reduce distractions such as alarms and flashing lights, and make use of perceptual cognition to reduce cognitive load. This requires not just careful design, but intelligent tools.

Therefore, when a designer takes into account latent bias and latent error of design, they are also designing for calm technologies by understanding the human and making technology that adapts to their needs and context. Even aside from these critical situations, there are benefits in creating digital tools according to calm technology guidelines in terms of ease-of-use and appeal to a larger section of the population.

5. Locus of Mind and Projection of Intelligence

One further concept is necessary before introducing the Objects and Actors Metaphor proposed in this article. Tools extend our physical, and sometimes cognitive abilities. Well-designed tools become almost part of us, even if that requires some training. A hammer, once we have learned to aim well, becomes an extension of the arm such that we don’t have to consciously think about how to use it.

With the recent growth of Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a tool to find information and inspiration, and even to solve complex problems, the possibility of offloading cognitive processes to a tool has become a reality. This accelerates a trend that computers and the Internet started with search engines as an extension of our minds and memories.

AI is different from search engines because many such tools pass the Turing Test [

25,

26] and thus the propensity for us to anthropomorphize them means we may ascribe actual intelligence to these digital assistants. This is not surprising as ‘doing mind’ for objects [

27] helps us understand and fit objects to our expectations, ascribing them capabilities that seem to fit their sometimes-complex natures, moving them from object status to intelligent entities.

This in itself is a form of metaphor use and a tendency we can capitalize on. What if we could create Extended Reality that is populated with digital entities that are as simple to interact with as picking up and throwing a ball, and as natural as holding a conversation with another human? In other words: Objects and Actors.

6. Metaphors in Digital Tools as a Design Language

With these ideas in mind, we need a framework on which to create our new design grammar. In language, we use metaphors as an aid in communication to promote mutual understanding. ‘This fire is as hot as the sun’, and ‘these gears operate as smooth as butter’ are a couple of examples. It is generally understood that metaphors are abstract. When I say “you’re on fire” meaning you are doing really well at something, we both understand that you are not, literally, on fire.

Similarly, when we make observations through our senses about the world around us and try to rationalize what we have observed, we need metaphors to give a sense of cause and effect that will enable us to make predictions about future interactions. In my mind, when driving, I understand that if I turn the steering wheel in the direction I want to go, the vehicle will subsequently move in that direction. I have a somewhat loose understanding of the mechanics that relate rotational movement of the steering wheel to the direction of the vehicle. Sometimes metaphors are difficult to articulate, but they exist, nonetheless.

In creating digital tools, finding appropriate real-world metaphors is one way to promote understanding, with the ‘Desktop’ metaphor from the PC era being a long-standing example [

17]. Further metaphors from digital environments include the cards and stacks metaphor of mobile devices, the timeline streams of social media, and the ‘superhighway’ and ‘cloud’ metaphors of the internet [

28]. As described above, we know from previous work that people find it easier to interact with physical objects in the real world than computer interfaces [

11]. Direct manipulation with the hands is something we have been practicing since babies. Likewise, it is much easier to ask someone to do something, trusting that they can interpret our vagueness using context, than to instruct a computer with step-by-step instructions. Thus, these modes of interaction, being more natural, would be more ‘calming’

In the domain of eXtended Reality, people will perceive the real world overlaid with digital content; where real objects, people and other sentient beings may be imbued with digital meaning; and purely digital artefacts can interact with the real world and may be perceived as sentient.

If working with digital tools could take advantage of these innate skills, this would be a huge step towards calming technologies, especially now that we are more mobile, and our digital tools go with us in the form of smartphones, smart watches, smart rings and other wearables, thus providing tools to overlay digital context.

Our idea is that the metaphor that would best suit this extended reality is where everything acts like, and is interacted with, in exactly the same way as we deal with the physical world. Real-world objects can be physically interacted with to activate digital content, digital characters can be spoken with just as we would to another human being and even completely digital objects can be perceived and interacted with in the same way (or as close as the technology allows) as physical objects. In that way, we take advantage of the already-familiar natural ways we interact with artefacts and people. This reduces the learning burden and provides a common language between the designer and end-user.

Further, with this metaphor and language, the tools we build should be able to adapt to context, foretelling what an individual requires even before they know it themselves. In the spirit of calm technology, these digital tools should therefore meld into us, supporting and adapting to our physical and cognitive requirements, resulting in intelligent (and calming) augmentation of our everyday extended reality.

7. Objects and Actors in Extended Reality

When we think about the world we live in, we can broadly classify things into inanimate and animate objects.

The former are those that have no impulse of their own, and therefore no agency; such as a rock, a piece of paper, or a pair of scissors. They may well have utility, even if that is just to ‘look nice’ or be a remembrance device such as an ornament, photograph or Grandma’s recipe for Christmas cake. Objects may have movement - rocks may fall, tides come in and out - but we ascribe these to external forces rather than the willful intent of the object itself [

27].

The latter are actors that have some agency and exhibit an independent will of their own. The cat, the dog, the duck-billed platypus are all examples of Actors that have their own imperatives and goals, and to which we ascribe some level of intelligence.

If the latest consumer electronics conference (CES2025) is anything to go by, affordable XR is just around the corner. With this in mind, we have to be aware that the opportunity for the exploitation of dormant and otherwise-managed anti-social behavior in an individual becomes more possible even than in today’s social-media fueled world due to the always available nature of XR. This could be even more dangerous for society than social media is today. Some artistic videos [

29] and [

30] explore these themes and provide perhaps a warning for where we might be headed.

For example, when we create things that are perceived as Actors but are, in fact, animated Objects, such as Non-Player-Characters (NPCs) in computer games. We can be fooled, at least within the bounds of the game, that these are indeed intelligent and self-willed entities, depending on how well the simulacrum is created. At some level, though, we know that they are not actually as ‘real’ as the dogs, cats, or people in our physical worlds and therefore we have no compunction in blasting them out of existence to reach our gaming goals.

Virtual Reality experiences, though, can be hugely influential on a person’s thinking and emotions; a characteristic that makes it effective for procedural, conceptual and cognitive training [

31,

32]. Thus, we can expect that eXtended Reality will also impact us beyond being merely entertaining. Indeed, Mixed Reality has long been used to improve the effectiveness of industrial training, with some headsets specializing in that high-end market (such as Varjo,

https://varjo.com/), and even those originally intended for a wider consumer base focusing ultimately on industrial training and visualization due to economic imperatives [

33,

34].

This underlines the imperative to choose the design language wisely by carefully defining the fitness function.

8. Spatial Context, Data Ownership and Privacy

We have argued so far that creating Calm eXtended Reality Tools (CXRT) is going to require knowledge about the time and place the tool is used, cross-referenced with information about the person or people using it and details about the environment in which it is being used. In other words; context, of which an important part is spatial intelligence and sensing. Indeed, Apple with the Vision Pro coined the term Spatial Computing, though this is restricted to room scale rather than the entire physical extent of users throughout their day.

To establish context, data must be collected, but the question is, where is it stored and who owns it? “If you are not paying for the product or service, then you are the product” [

35] should be a reminder that your data and metadata (data about your usage of your data) are valuable assets for generating revenue. A classic example is the Map service by a prominent Internet company. The utility is great, with such helpful functionality that navigating with printed paper maps is now a dying art, but what do they get out of helping you get to where you want to go? Your location, speed, search history, nearby Wi-Fi and Bluetooth information are examples of some of the data that is collected, which are in turn used to improve the service and tailor advertising and anonymized data for paying customers.

However, are you, the person generating this data, getting full value, and what control do you have over when, where, how and with whom that data is being shared? Can you be assured of privacy?

Governments legislate to improve matters for their citizens, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe [

36], which is important, since without these checks, most companies would have little compunction about gathering as much data as possible, whilst returning little value. Their loyalty is to their shareholders, not their users.

For many people, this is acceptable because the increase in contextual intelligence usage means more intuitive and adaptive tools. We understand that free products and services mean a dent in our privacy, but does it have to be that way? What if the control could be put back into the hands of the users, with a suite of tools to enable management and control of the data and metadata usage?

9. A Proposed Fitness Function

In the evolutionary epistemology of theories [

2], direction is maintained through evaluating progress according to some desired, long-term outcomes. In nature, this is called survival of the fittest, where fitness means ‘the ability to thrive in the current environment’. As environments change, the characteristics that promote survival may change.

Similarly, in the area of digital tools, we might posit that a suitable fitness function could promote tools which improve the ability of the people using them to thrive in the current environment. Further, their survival must contribute to the longevity of our societies, and the environment that we all require to maintain life, otherwise, there is no future.

Our thesis therefore is that for digital tools to be considered more ‘fit’ than their contemporaries, they need to become a seamless part of the person, adapting to their changing situations and needs whilst assisting them to achieve their desired outcomes (according to Calm Technology design principles), and maintaining privacy. As a by-product, such tools will likely also be more efficient and easier to use.

10. Reality2 - An Emergent System Using Digital Agents

The Internet is a complex network of computers that has the emergent properties of a library of knowledge and a toolbox of capabilities for people to use to solve a myriad of problems and perform a plethora of tasks.

If, at the outset, it had been intended to create what we see today from such an ad-hoc distributed system of computers, it would have been difficult to predict the capabilities to give each computer-node that would then lead to the desired emergent properties. Instead, HTML, CSS and Javascript, supported by many deeper-level capabilities were made available, and human inventiveness has resulted in the pandora’s box of incredible benefits and unforeseen consequences we have today.

With the thought that perhaps we are opening a new box that could release both blessings and evils on the world, we have created a suite of protocols and tools with the intention of creating the emergent property of more use-worthy, calming, digital tools – which we call ‘Reality2’ [

37].

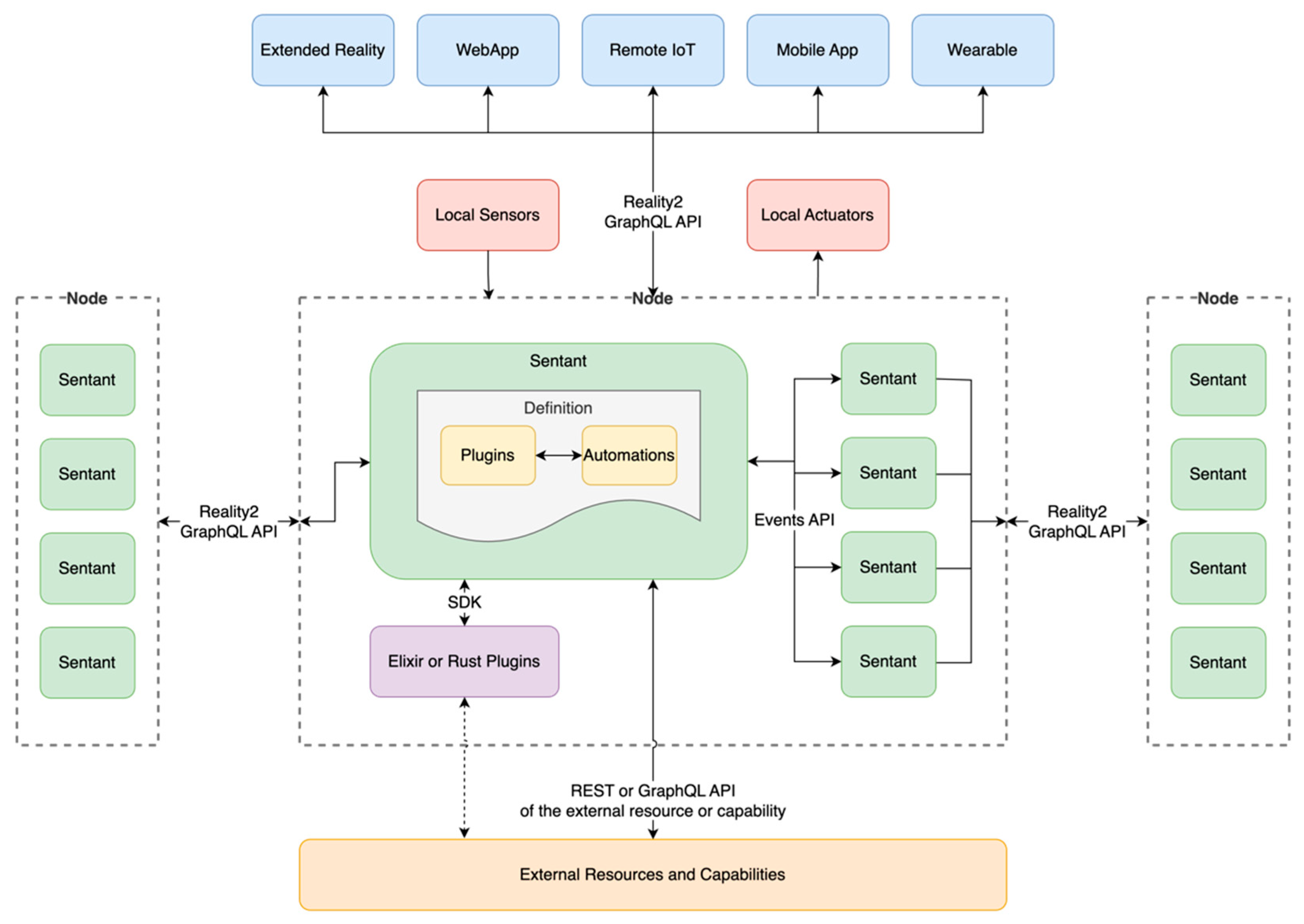

Reality2 runs on computers, which we call Nodes, such as might be found in wearable devices like wristbands, watches and XR glasses, as well as fixed devices such as Point of Sale (PoS) machines, Automatic Tellers (ATM), attached to routers in a WiFi network or as Virtual Machines in the cloud. The Reality2 tools and protocols extend from the OSI network layer 7 (Application) down to layer 3 (Network) to implement semi-embodied digital agents on transient wireless networks for eXtended Reality (XR).

For end-users, Reality2 provides intuitive, contextual interaction with XR Entities. These may be real-world objects imbued with digital content, or completely virtual entities that are perceived to exist in the real world. The entities are implemented as semi-embodied digital agents, called ‘Sentants’ (short for Sentient Agents). A single Node may host many Sentants which can sense the world through Sensors (for example, air temperature, motion detection, heart rate, or skin conductivity) and have an effect through Actuators (such as make a noise, activate a motor or turn on a switch). Sensors and Actuators are physically attached to the Node but used by the Sentants.

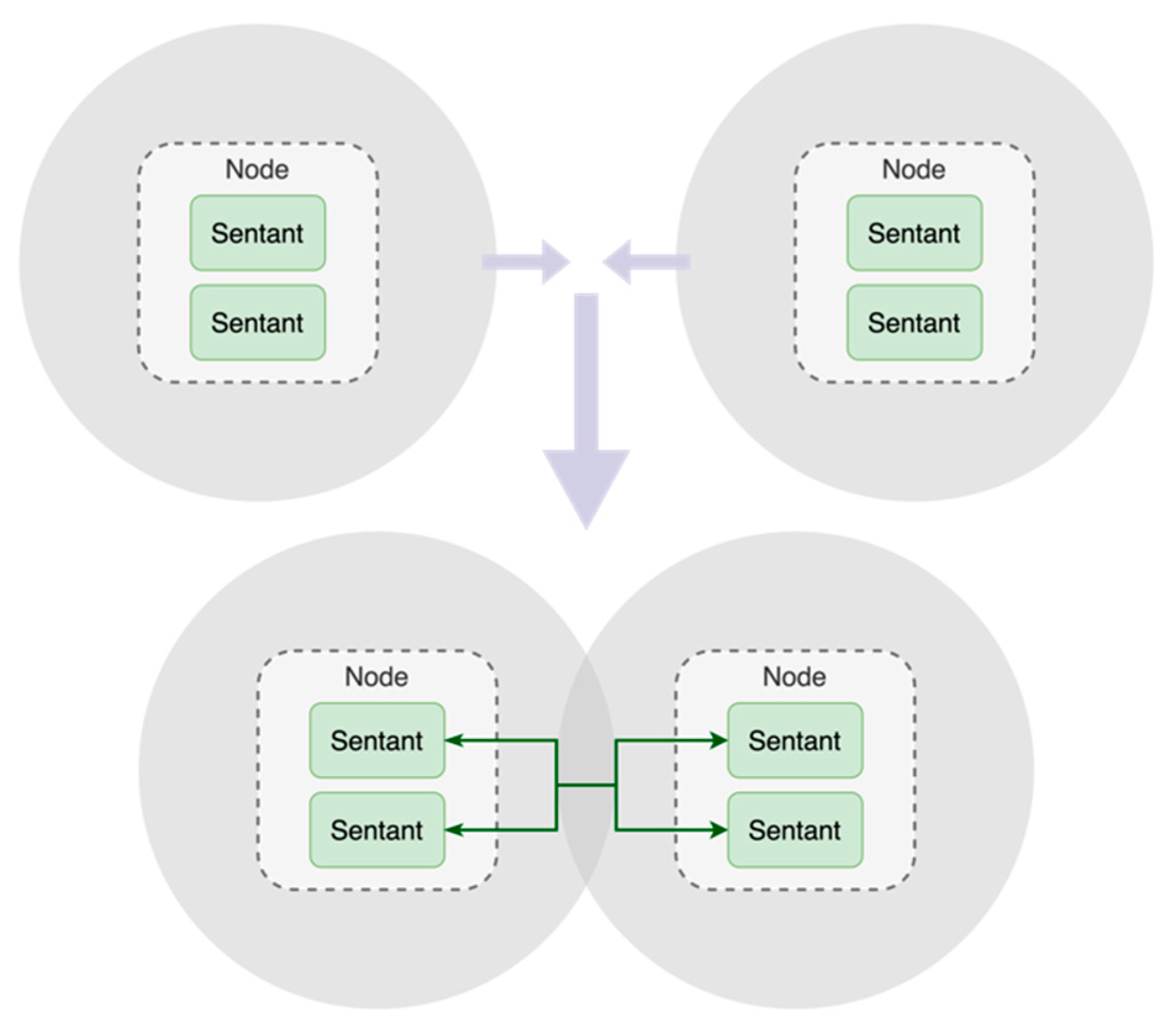

Nodes make use of proximity as a key determiner of context. This might be through the use of GPS, through overlapping WiFi or Bluetooth networks, by using beacons, or even triangulation in a WiFi or GSM network to base stations. We call the areas around a node ‘proximity fields’, and this ad-hoc way of networking, Transient Networks (

Figure 1).

Imagine, for example, a headband worn by a truck driver that has sensors to detect tiredness and wavering attention. When the driver enters the truck cab, the headband Node connects to the truck Node as their sensitivity fields overlap, and the Sentants in each converse and share relevant information. The Sentants in both are programmed to warn the driver before an accident actually occurs when the sensors detect a potentially dangerous situation. They could further be connected (via the plugin architecture) to a system that helps the driver to find a place to pull off the road safely to have a snooze before driving further and into the truck automated driving system to tweak settings to account for reduced capability.

With the Reality2 framework, one of the key goals is to use, protect and grow contextual intelligence, striving towards digital tools that are ever-more use-worthy, as per the fitness function proposed above. To guide the design language and provide a domain of usage, we propose three core precepts: 1) that people are mobile, taking their technologies with them; 2) that intelligence capability needs to be distributed; and 3) that information and data should be stored closest to the source (and thus the owner).

The ‘Objects and Actors’ metaphor implies that interaction with, and understanding of, Sentants should be like interacting with real-world objects in a physical manner (such as picking up and throwing a ball), and real-world actors (such as talking to another human being or scratching a dog behind the ears). Central to this is the idea that things happen (events) either from external forces such as user interactions, events from other nodes or sensors in the environment, or resulting from internal activities; and these events can trigger something to happen (actions).

Reality2 is open source and open protocol, with a reference implementation [

38] built in the Elixir Language using an Agentic AI architecture with the ability to extend functionality through plugins and programmability of each agent using Automations (a form of Finite State Machine). Sentants are Turing Complete which means that they ‘

can be used to compute any computable sequence’ [

39]. GraphQL is used for communications due to its discoverability and wide acceptance across programming languages. The Sentants are set up and programmed using scripts, and once activated are immutable and opaque to questing hackers, reacting only to pre-programmed events and proximity to external sources such as other Reality2 agents, sensors and people (

Figure 2).

11. Conclusions

In this paper, we explored the idea that a new Metaphor or design language based on how we interact with the real world should encourage the growth of more use-worthy eXtended Reality Tools. We further discussed that a fitness function to drive the growth of stronger ideas based around the guidelines embodied in Calm Technology will ultimately likewise result in improved use-worthiness. Finally, we brought these together into a possible solution using Agentic AI with a distributed Agent Platform called Reality2 as a platform for this new ‘Objects and Actors’ metaphor.

Digital Agents (or Sentants in the Reality2 parlance) that can sense the digital and physical environments around users allow granular control, contextual intelligence and natural interactivity that bring adaptive and assistive technologies into the domain of the user. This moves the locus of mind and the focus of attention from a screen to the augmented real and virtual entities perceived as being within the real world.

Similarly, by instructing Sentants, users can describe a desired outcome, set up a scenario, and then let them solve the problem using contextual (and local) intelligence with only occasional checking and input required. So, I could set up a Sentant to look for suitable accommodation and restaurants that activates when I enter a new city while on holiday, for example. We imagine a world populated by helpful Sentant ‘Bumblebees’, buzzing around you and interacting with other Bumblebees to help you achieve your goals and carry out your tasks.

The possibility of a distributed model of digital intelligence and agency means that we are less reliant on centralised systems, with all the problems that brings, and allows us to shift the balance of power in data ownership from the large tech companies to the people actually using the technology and generating the data (and metadata).

At this stage, Reality2 is still in early development, so we have yet to establish whether it will bring about improved use-worthiness and revolutionise eXtended Reality Tools as we hope. The challenge now is to build it into all sorts of Assistive Technologies and Tools and evaluate how well it compares against existing solutions, and for designers and developers to take to heart the methodologies of Calm Technology to build solutions that benefit from the Objects and Actors metaphor.

We are in a unique position to push back against the imposed fitness functions from above that prioritise economic gains above all else. The inflection point of a paradigm shift is the ideal time to influence the new direction, but if we tarry too long, we will lose that advantage. Our thesis is that if you are unsure of a direction, and need help making decisions, then looking to the work on Calm Technology and taking into account the Objects and Actors metaphor will provide the tools and guidance you need.

References

- D. Norman, The Design of Future Things, May 2009. Basic Books, 2009.

- B. Harms, M. Harms, and Harms William, “Evolutionary Epistemology,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2023., E. N. Zalta and U. Nodelman, Eds., 2023. Accessed: Mar. 05, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/epistemology-evolutionary/.

- H. Eftring, The Useworthiness of Robots for People with Physical Disabilities. Certec, Department of Design Sciences, Lund University, 1999.

- M. N. Negnevitsky, “Artificial Intelligence - A Guide to Intelligent Systems (Second Edition),” 2005. [Online]. Available: www.pearsoned.co.uk.

- J. Stamp, “Fact or Fiction? The Legend of the QWERTY Keyboard.,” Smithsonian Magazine, May 13, 2013. Accessed: Mar. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/fact-of-fiction-the-legend-of-the-qwerty-keyboard-49863249.

- S. Dowling, “The surprising origins of the TV remote.” Accessed: Mar. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180830-the-history-of-the-television-remote-contro.

- J. Reason, Human Error. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- E. Dedezade, “Apple Commits $500 Billion To AI Race As Some Rivals Slow Down.” Accessed: Mar. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/esatdedezade/2025/02/24/beyond-apples-500-billion-techs-diverging-ai-strategies/.

- H. Rheingold, Virtual Reality - The revolutionary Technology of Computer-Generated Worlds - and how it Promises to Transform Society. Summit Books, 1991. Accessed: Mar. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.co.nz/books?id=hHZQAAAAMAAJ.

-

P. Milgram and F. Kishino, “A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays,” IEICE Trans Inf Syst, vol. 77, pp. 1321–1329, 1994, [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:17783728.

- R. C. Davies, “Adapting Virtual Reality for the Participatory Design of Work Environments.,” Kluwer Academic Publishers., vol. 13, pp. 1–33, 2004.

- A. Klein, C. Carsten Sørensen, A. S. de Freitas, C. D. Pedron, and S. Elaluf-Calderwood, “Understanding controversies in digital platform innovation processes: The Google Glass case.,” Technol Forecast Soc Change, vol. 152, Mar. 2020.

- D. Norman, The Invisible Computer - Why Good Products Can Fail, the Personal Computer Is So Complex, and Information Appliances Are the Solution. Cambridge, MA, United States: MIT Press, 1998.

- Corning, “A day made of glass,” https://www.corning.com/worldwide/en/innovation/a-day-made-of-glass.html.

- M. Weiser and J. Seely Brown, “The coming age of Calm Technology,” in Beyond Calculation, the next fifty years of computing, P. J. Denning and R. M. Metcalfe, Eds., New York: Springer Verlag, 1997, ch. 6, pp. 75–86.

- M. Weiser and J. Seely Brown, Designing Calm Technology. Xerox PARC, 1995.

- M. Beard et al., “ The Xerox Star: A Retrospective ,” Computer , vol. 22, no. 09, pp. 11–26, 28–29, Sep. 1989. [CrossRef]

- A. Tugui, “Calm technologies in a multimedia world,” Ubiquity, vol. 2004, no. March, p. 1, Mar 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Hohl, “Calm Technologies 2.0: Visualising Social Data as an Experience in Physical Space,” Parssons journal for information mapping, no. 1(3), pp. 1–7, 2009.

- A. Case, Calm Technology: Principles and Patterns for Non-intrusive Design. O’Reilly Media, 2016.

- C. Ware, “Interacting with Visualizations,” Inf Vis, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:114932498.

- I. Alloui, D. Esale, and F. Vernier, “Wise Objects for Calm Technology,” in 10th International Conference on Software Engineering and Applications (ICSOFT-EA 2015), 2015, pp. 468–471.

- H. Thimbleby, “Avoiding Latent Design Conditions Using UI Discovery Tools,” Int J Hum Comput Interact, vol. 26, no. 2–3, pp. 120–131, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. DeCamp and C. Lindvall, “Latent bias and the implementation of artificial intelligence in medicine,” J Am Med Inform Assoc, vol. 27, no. 12, 2020.

- A. M. Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Oxford University Press on, 1950. [Online]. Available: http://www.jstor.orgStableURL:http://www.jstor. 2251.

- C. R. Jones and B. K. Bergen, “People cannot distinguish GPT-4 from a human in a Turing test,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.08007.

- E. Owens, “Nonbiologic Objects as Actors,” Symb Interact, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 567–584, 2007.

- S. Wyatt, “Metaphors in critical Internet and digital media studies,” New Media Soc, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 406–416, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Matsuda, “hyper-reality,” https://youtu.be/YJg02ivYzSs.

- 3DAR, “Uncanny Valley - Sci-Fi VFX Short Film,” https://youtu.be/FQgpw9pp-qQ.

- A. “Skip” Rizzo and R. Shilling, “Clinical Virtual Reality tools to advance the prevention, assessment, and treatment of PTSD,” Eur J Psychotraumatol, vol. 9, no. sup5, 2017.

- K. Gupta et al., “Healing Horizons: Adaptive VR for Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation,” in SIGGRAPH Asia 2023 XR, in SA ’23. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Paul, “Exclusive: Google, augmented reality startup Magic Leap strike partnership deal.” Accessed: Mar. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/technology/google-augmented-reality-startup-magic-leap-strike-partnership-deal-2024-05-30/.

- C. Paoli, “Microsoft confirms end of HoloLens Mixed Reality Hardware.” Accessed: Mar. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://rcpmag.com/Articles/2025/02/14/Microsoft-Confirms-End-of-HoloLens-Mixed-Reality-Hardware.aspx.

- T. O’Reilly, “Quote Origin: You’re Not the Customer; You’re the Product,” https://quoteinvestigator.com/2017/07/16/product/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- “Complete guide to GDPR Compliance,” https://gdpr.eu/.

- R. C. Davies, “Reality2 - The framework for the Objects and Actors Metaphor.” Accessed: Mar. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://reality2.ai.

- R. C. Davies, “Reality2 Node Core Elixir implementation.” Accessed: Mar. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/reality-two/reality2-node-core-elixir.

- A. M. Turing, “On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem,” Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, vol. s2-42, no. 1, pp. 230–265, 1936. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).