Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

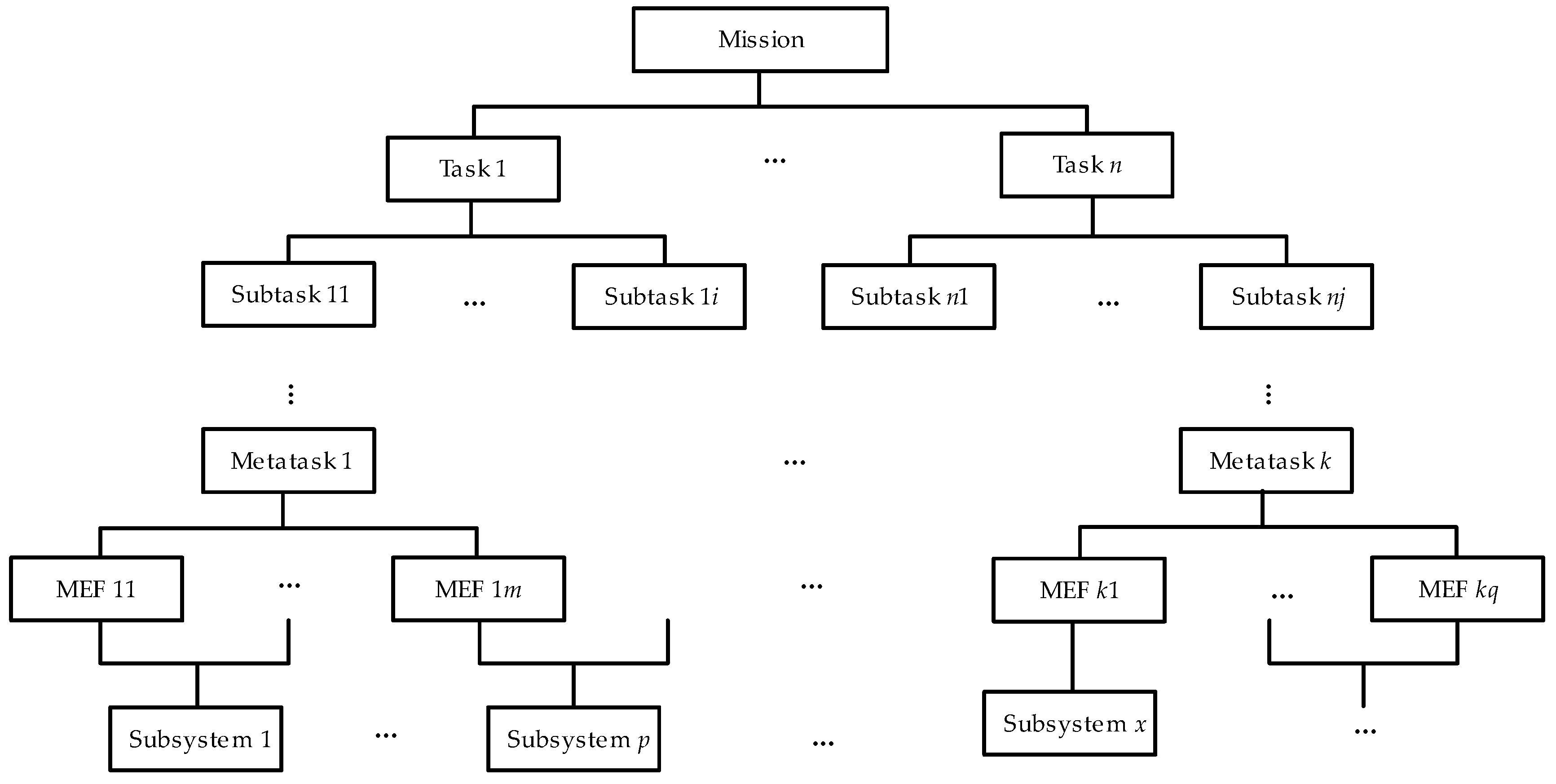

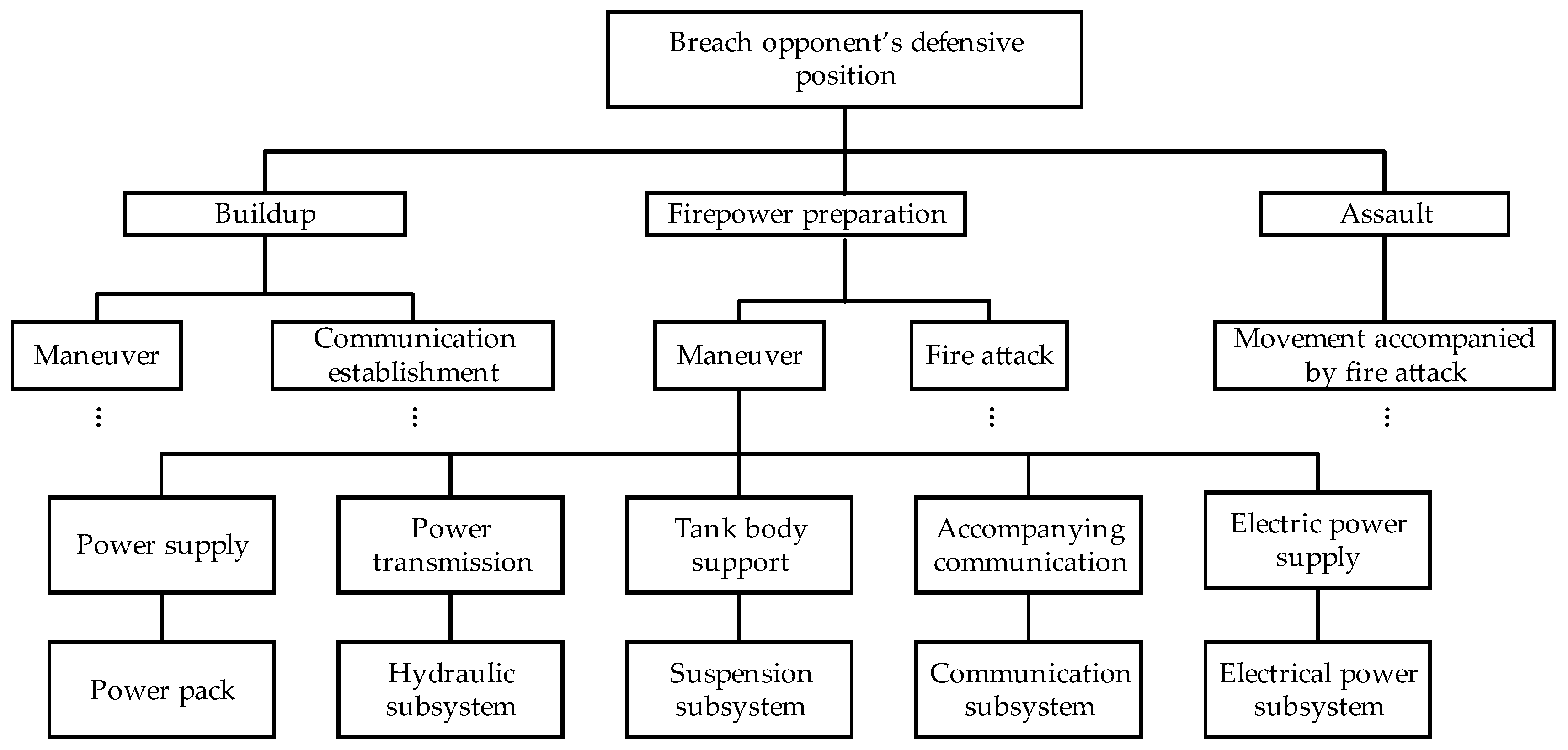

2. Hierarchical Decomposition of the SUT’s Mission

3. Similarity Factor Calculation

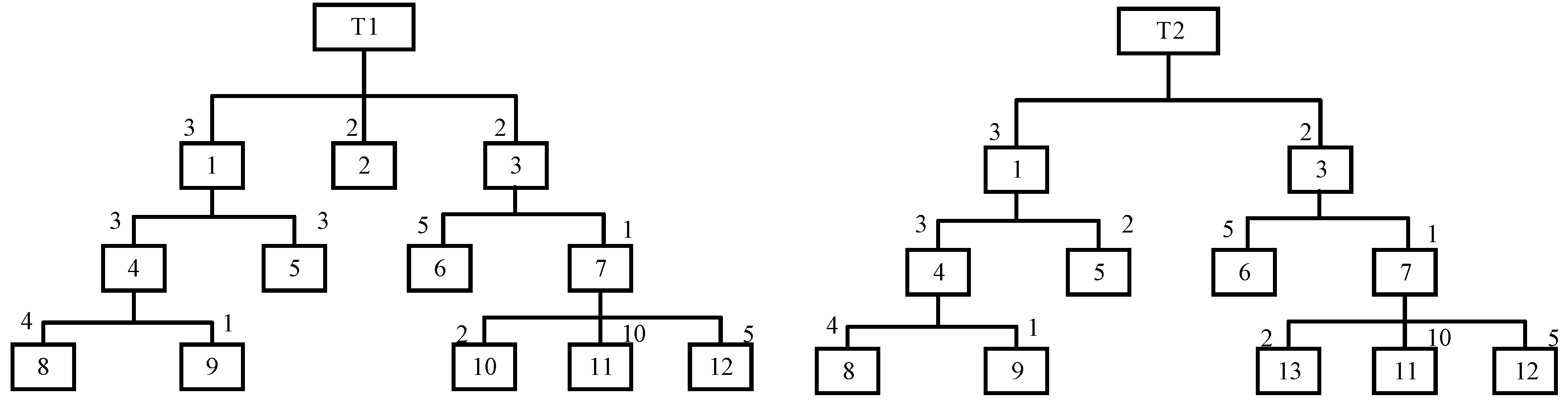

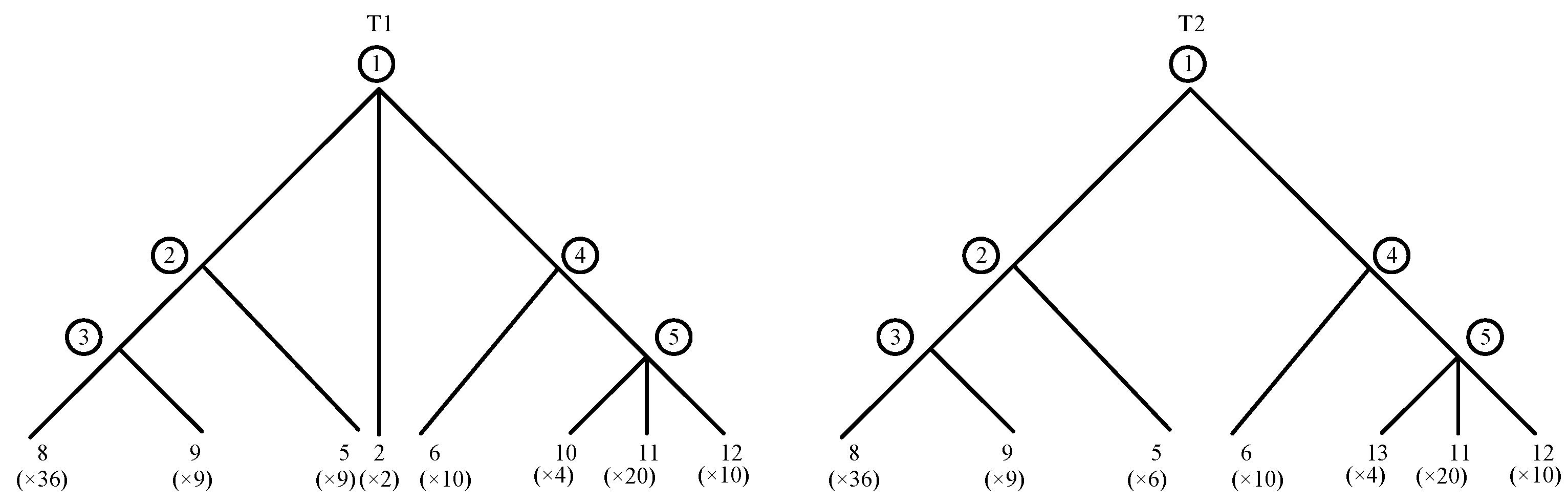

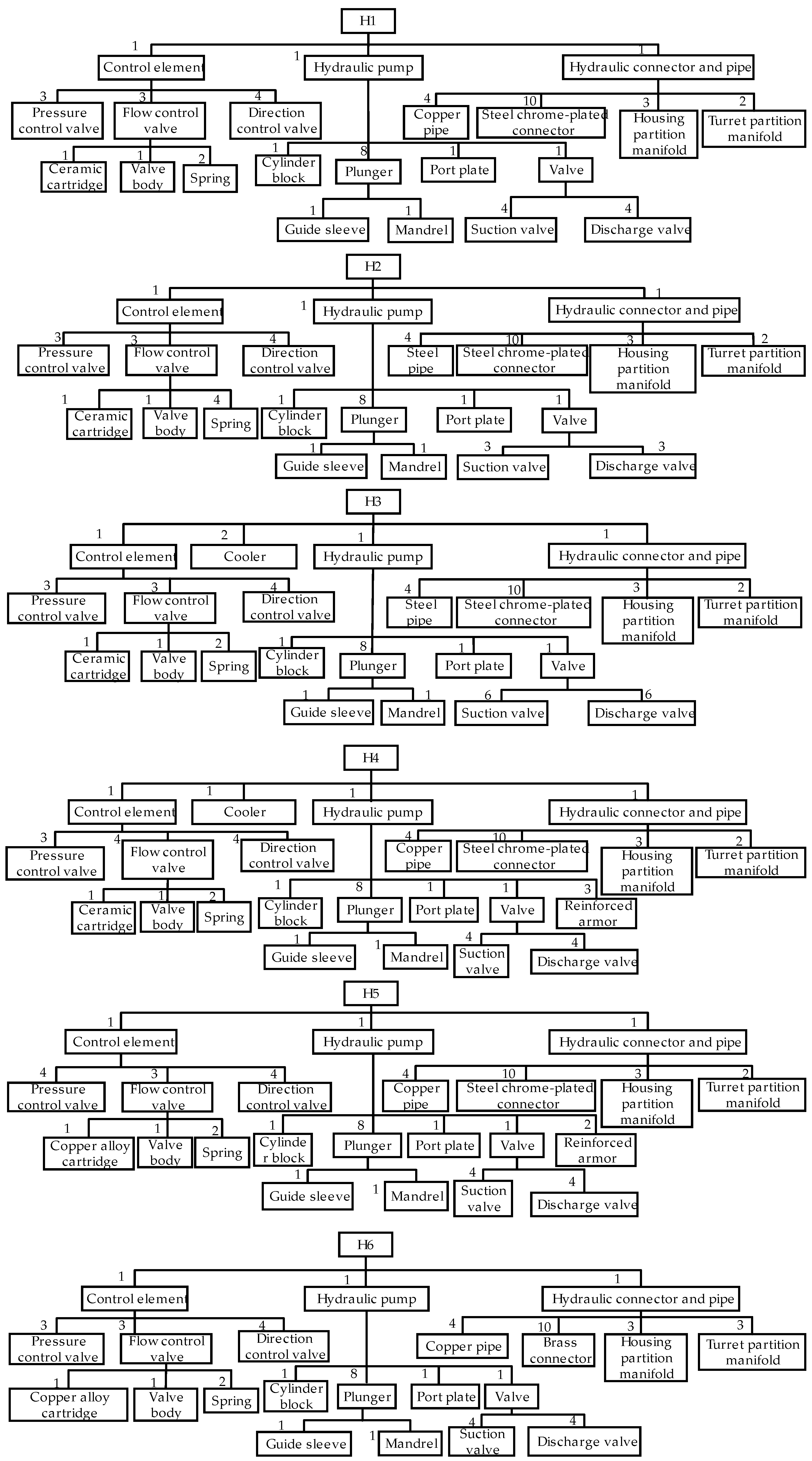

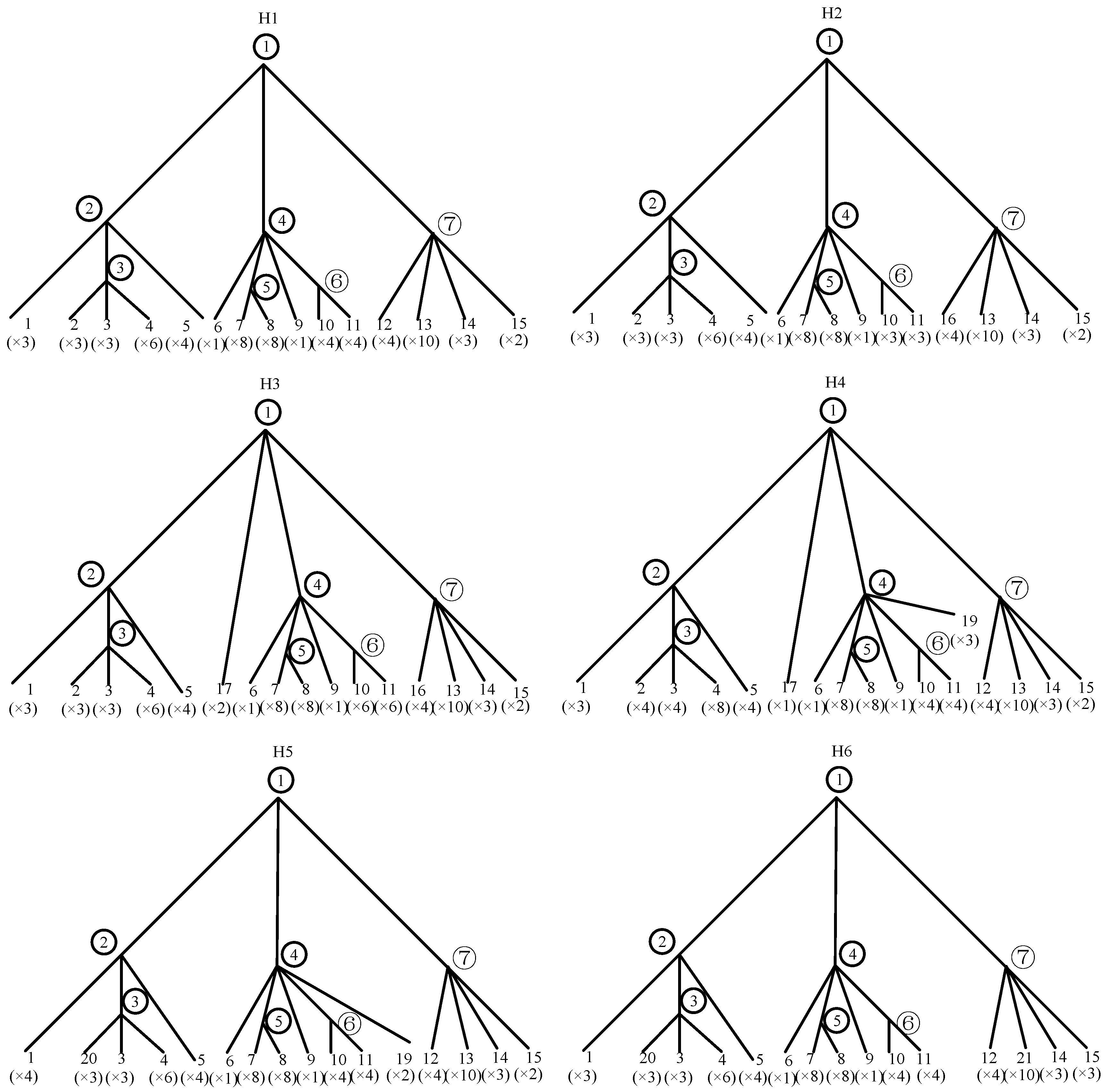

3.1. Establishment of PT Representation

3.2. Distance Calculation Principle

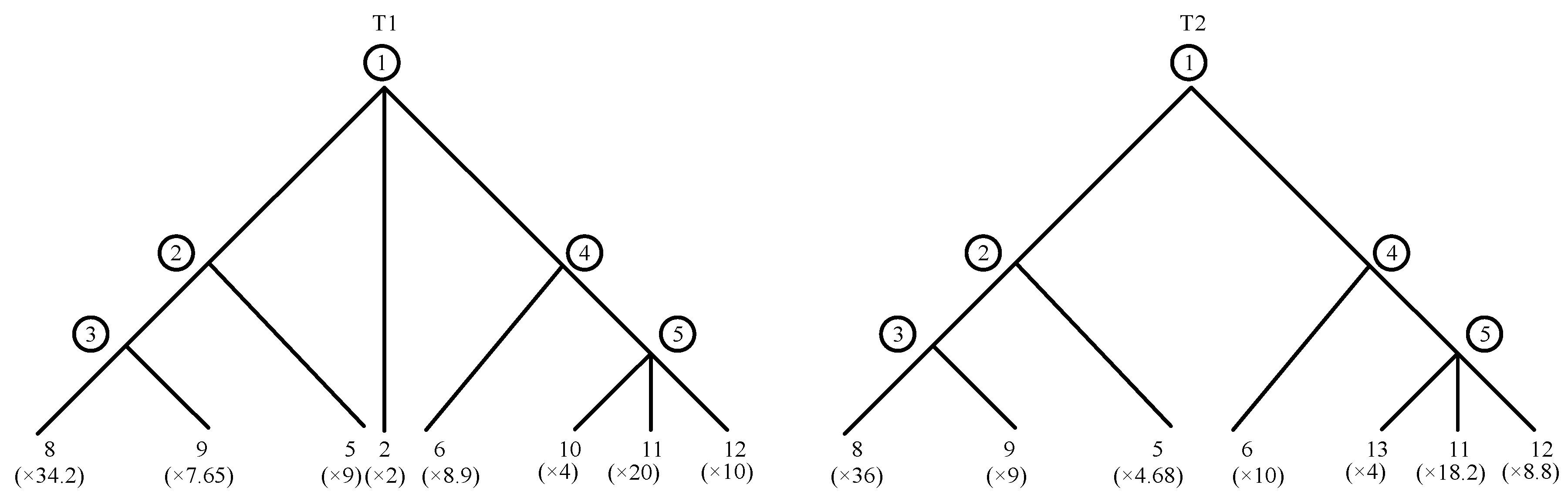

3.3. MIP Solution of Distance and Determination of Similarity Factor

3.3.1. Matrix Encoding Corresponding to PT

3.3.2. MIP Construction and Similarity Factor Calculation

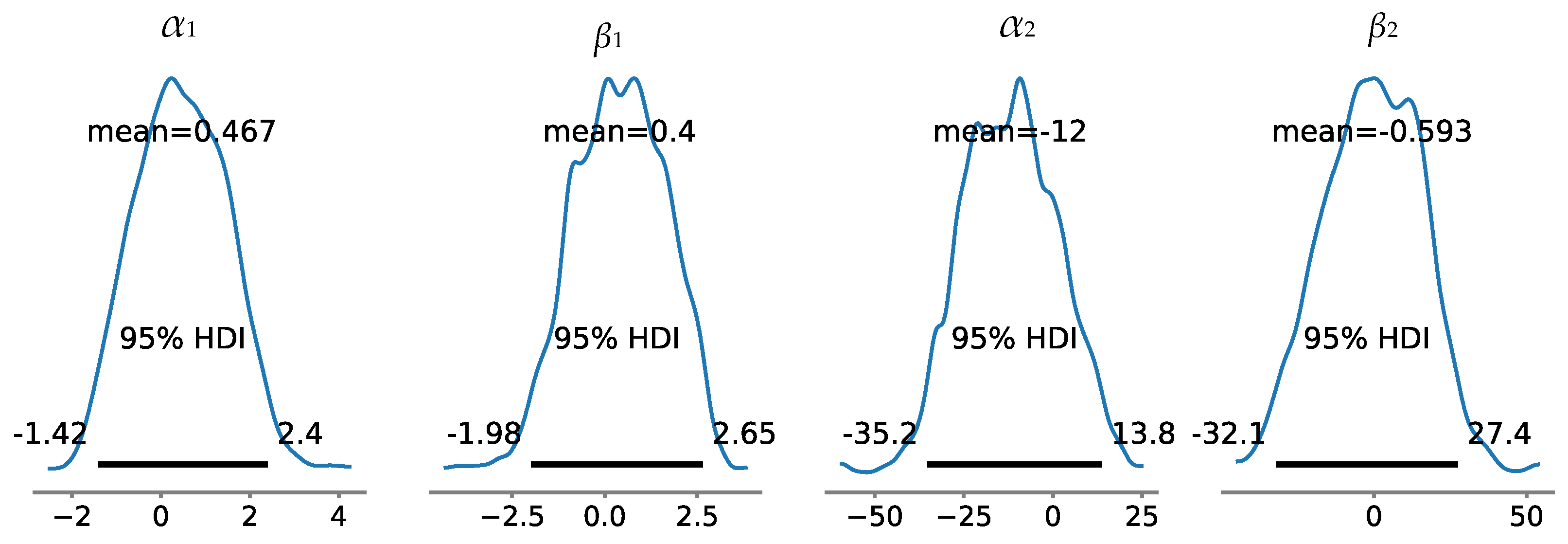

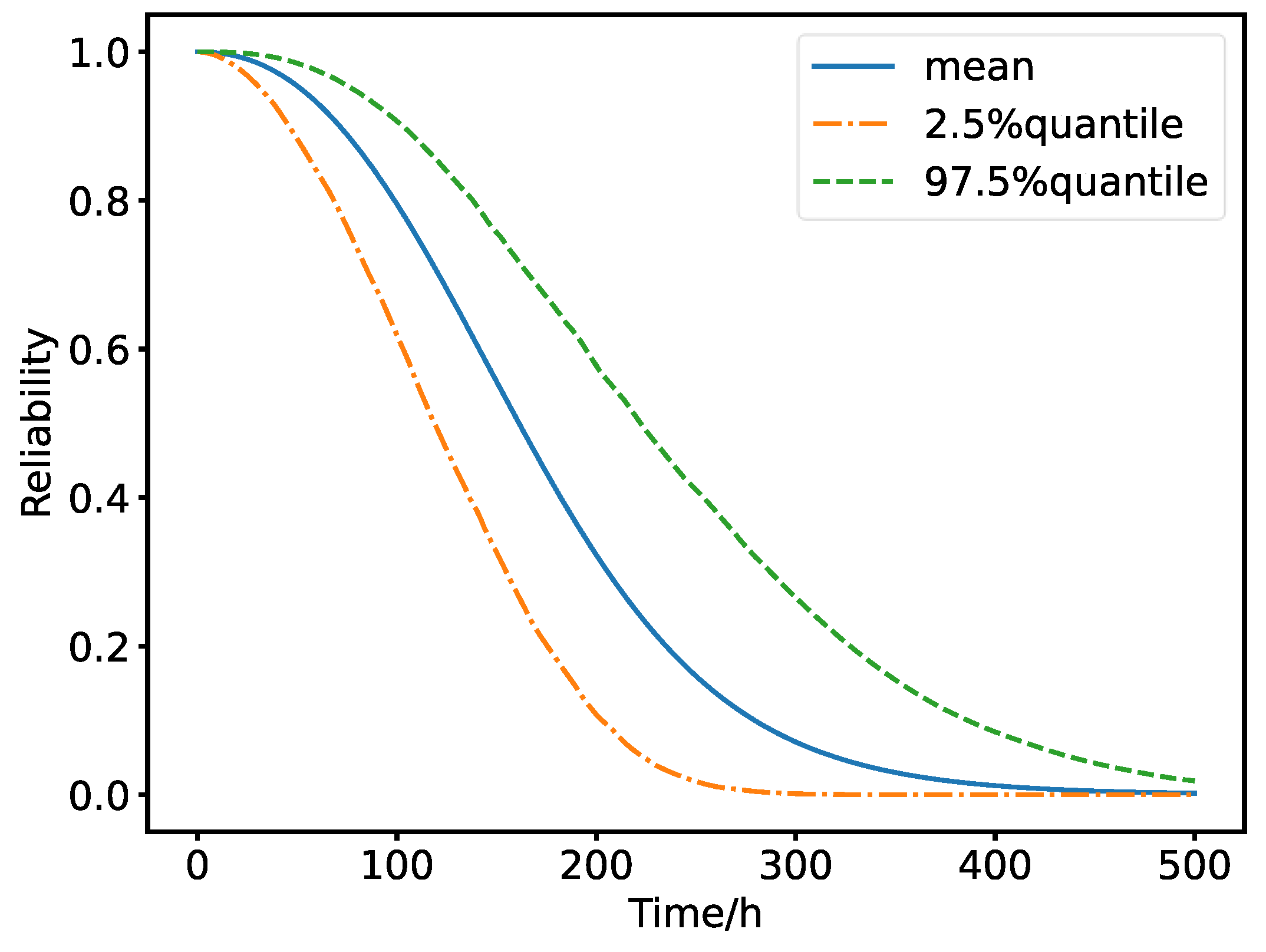

4. Reliability Assessment Model

5. Numerical Experiments

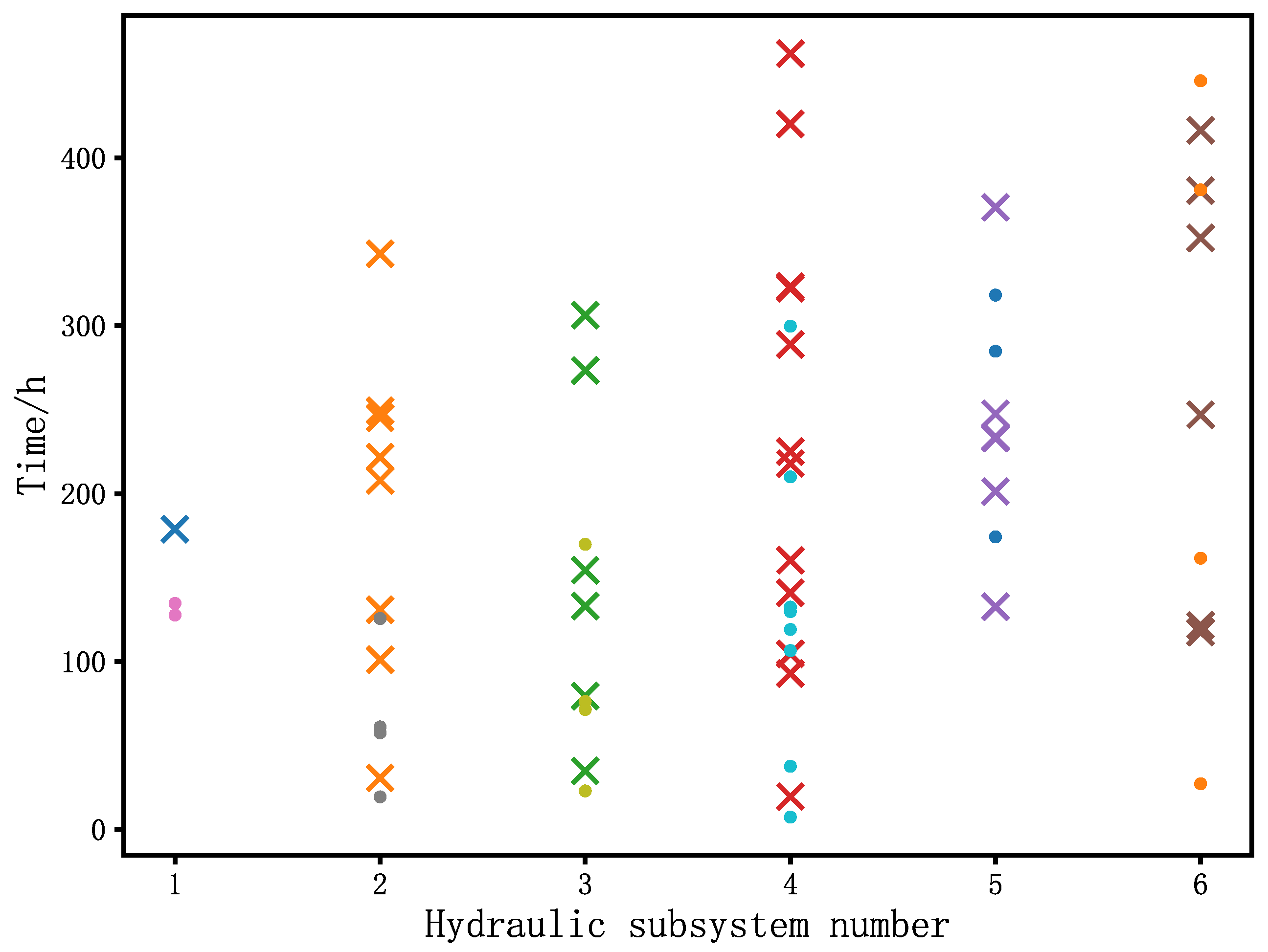

5.1. Application of the Proposed Method

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DEMENT A, HARTMAN R. Operational suitability evaluation of a tactical fighter system[C]//3rd Flight Testing Conference and Technical Display. 1996: 9753.

- Li J, Nie C, Wang L. Overview of weapon operational suitability test[C]//2016 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Engineering Applications. Atlantis Press, 2016: 423-428. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council, Division of Behavioral, Social Sciences, et al. Improved Operational Testing and Evaluation and Methods of Combining Test Information for the Stryker Family of Vehicles and Related Army Systems: Phase II Report[M]. National Academies Press, 2003.

- Lee B, Seo Y. A design of operational test & evaluation system for weapon systems thru process-based modeling[J]. Journal of the Korea Society for Simulation, 2014, 23(4): 211-218. [CrossRef]

- Ke X C. Reliability predictions of a canister cover based on similar product method [J]. Environment adaptability & reliability, 2022,40(04):35-37.

- Li L, Liu Z, Du X. Improvement of analytic hierarchy process based on grey correlation model and its engineering application[J]. ASCE-ASME Journal of Risk and Uncertainty in Engineering Systems, Part A: Civil Engineering, 2021, 7(2): 04021007. [CrossRef]

- Ahlgren P, Jarneving B, Rousseau R. Requirements for a cocitation similarity measure, with special reference to Pearson's correlation coefficient[J]. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 2003, 54(6): 550-560. [CrossRef]

- Xiang S, Nie F, Zhang C. Learning a Mahalanobis distance metric for data clustering and classification[J]. Pattern recognition, 2008, 41(12): 3600-3612. [CrossRef]

- Elmore K L, Richman M B. Euclidean distance as a similarity metric for principal component analysis[J]. Monthly weather review, 2001, 129(3): 540-549. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Dai W. Multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on included angle cosine and its application[C]//2008 International Conference on Information and Automation. IEEE, 2008: 1045-1049. [CrossRef]

- Rui H, D. Research on reliability growth AMSAA model of complex equipment based on grey information [D]. 2016, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

- Meeker W Q, Escoba L A. Reliability: The other dimension of quality[J]. Quality Technology & Quantitative Management, 2004, 1(1): 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Jin S, Chen J, Gu R. Study on similarity criterion of equivalent life model of wind turbine main shaft bearing [J]. Manufacture technology and machine, 2021(07): 146-152.

- Liu Y, Huang H Z, Ling D. Reliability prediction for evolutionary product in the conceptual design phase using neural network-based fuzzy synthetic assessment[J]. International Journal of Systems Science, 2013, 44(3): 545-555. [CrossRef]

- Fang S, Li L, Hu B, et al. Evidential link prediction by exploiting the applicability of similarity indexes to nodes[J]. Expert Systems with Applications, 2022, 210: 118397. [CrossRef]

- YANG Jun, SHEN Lijuan, HUANG Jin, et al. Bayes comprehensive assessment of reliability for eectronic products by using test information of similar products [J]. Acta aeronautica et astronautica sinica, 2008, 29(6): 1550-1553.

- Wen, Y. Study on the reliability analysis and assessment method of the aerospace pyrotechnic devices [D]. 2015, Beijing Institute of Technology.

- Jeong, Y. A study on the development of the OMS/MP based on the Fundamentals of Systems Engineering[J]. International Journal of Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering, 2018, 10(4): 468-476. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarpour B, Stracener J T. Mission reliability analysis of phased-mission systems-of-systems with data sharing capability[C]//2015 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS). IEEE, 2015: 1-6. [CrossRef]

- King J R, Nakornchai V. Machine-component group formation in group technology: review and extension [J]. The international journal of production research, 1982, 20(2): 117-133. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y J, Chen Y M, Chu H C, et al. Integrated clustering approach to developing technology for functional feature and engineering specification-based reference design retrieval[J]. Concurrent Engineering, 2005, 13(4): 257-276. [CrossRef]

- Karaulova T, Kostina M, Shevtshenko E. Reliability assessment of manufacturing processes[J]. International journal of industrial engineering and management, 2012, 3(3): 143. [CrossRef]

- Shih H M. Product structure (BOM)-based product similarity measures using orthogonal procrustes approach[J]. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 2011, 61(3): 608-628. [CrossRef]

- Orlicky J A, Plossl G W, Wight O W. Structuring the Bill of Material for MRP[J]. Operations management: critical perspectives on business and management, 2003: 58-81.

- Romanowski C J, Nagi R. On comparing bills of materials: a similarity/distance measure for unordered trees[J]. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics-Part A: Systems and Humans, 2005, 35(2): 249-260. [CrossRef]

- Kashkoush M, ElMaraghy H. Product family formation by matching Bill-of-Materials trees[J]. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology, 2016, 12: 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Xu X S, Wang C, Xiao Y. Similarity Judgment of Product Structure Based on Non-negative Matrix Factorization and Its Applications[J]. China Mechanical Engineering, 2016, 27(08): 1072-1077.

- Kapli P, Yang Z, Telford M J. Phylogenetic tree building in the genomic age[J]. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2020, 21(7): 428-444. [CrossRef]

- Pattengale N D, Gottlieb E J, Moret B M E. Efficiently computing the Robinson-Foulds metric[J]. Journal of computational biology, 2007, 14(6): 724-735. [CrossRef]

- Wolsey L A. Mixed integer programming[J]. Wiley Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Engineering, 2007: 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Parganiha K. Linear Programming With Python And Pulp[J]. International Journal of Industrial Engineering, 2018, 9(3): 01-08. [CrossRef]

- JIA Xiang, GUO Bo. Reliability evaluation for products by fusing expert knowledge and lifetime data [J]. Control and Decision, 2022, 37(10): 2600-2608.

- Hoffman M D, Gelman A. The No-U-Turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo[J]. J. Mach. Learn. Res., 2014, 15(1): 1593-1623.

- Turkkan N, Pham-Gia T. Computation of the highest posterior density interval in Bayesian analysis[J]. Journal of statistical computation and simulation, 1993, 44(3-4): 243-250. [CrossRef]

| Node in T1 | Most similar node in T2 | Component in T1 but not in T2 | Shared component with higher quantity in T1 | Level difference | Quantity difference | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2,10 | 5 | 1,3,2 | 2,4,3 | 4.83 |

| 2 | 2 | - | 5 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| 4 | 4 | 10 | - | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | - | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 13.83 | |||||

| Node in T2 | Most similar node in T1 | Component in T2 but not in T1 | Shared component with higher quantity in T2 | Level difference | Quantity difference | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 13 | - | 3 | 4 | 1.33 |

| 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| 3 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 0 |

| 4 | 4 | 13 | - | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 5 | 13 | - | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 7.33 | |||||

| Name | Assigned number | Name | Assigned number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure control valve | 1 | Copper pipe | 12 |

| Ceramic cartridge | 2 | Steel chrome-plated connector | 13 |

| Valve body | 3 | Housing partition manifold | 14 |

| Spring | 4 | Turret partition manifold | 15 |

| Direction control valve | 5 | Steel pipe | 16 |

| Cylinder block | 6 | Cooler | 17 |

| Guide sleeve | 7 | Copper pipe | 18 |

| Mandrel | 8 | Reinforced armor | 19 |

| Port plate | 9 | Copper alloy cartridge | 20 |

| Suction valve | 10 | Brass connector | 21 |

| Discharge valve | 11 |

| Subsystem | Parameter | Relative deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Existing method | Proposed method | ||

| SSUT | m | 0.054 | -0.029 |

| λ | 0.178 | -0.027 | |

| Subsystem 1 | m | 0.315 | -0.035 |

| λ | 0162 | -0.074 | |

| Subsystem 2 | m | 0.263 | -0.076 |

| λ | 0.236 | -0.037 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).