Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Objective

3. Material

4. Method

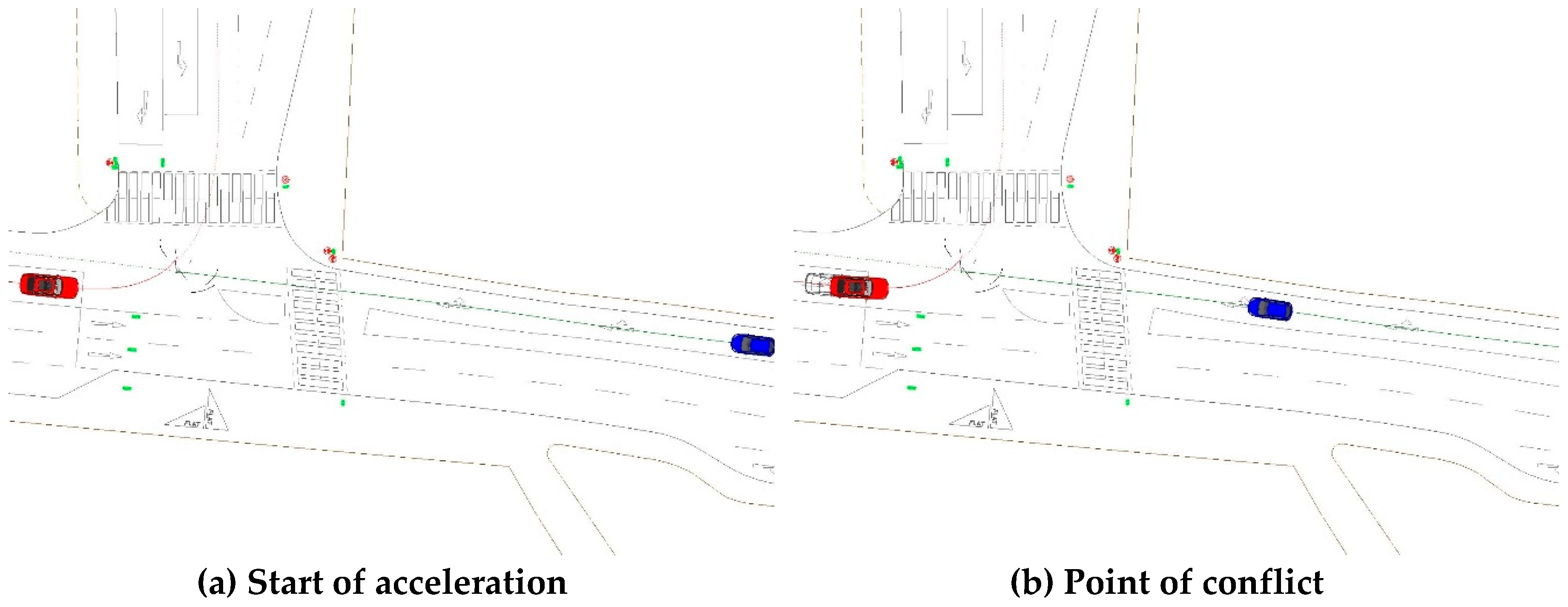

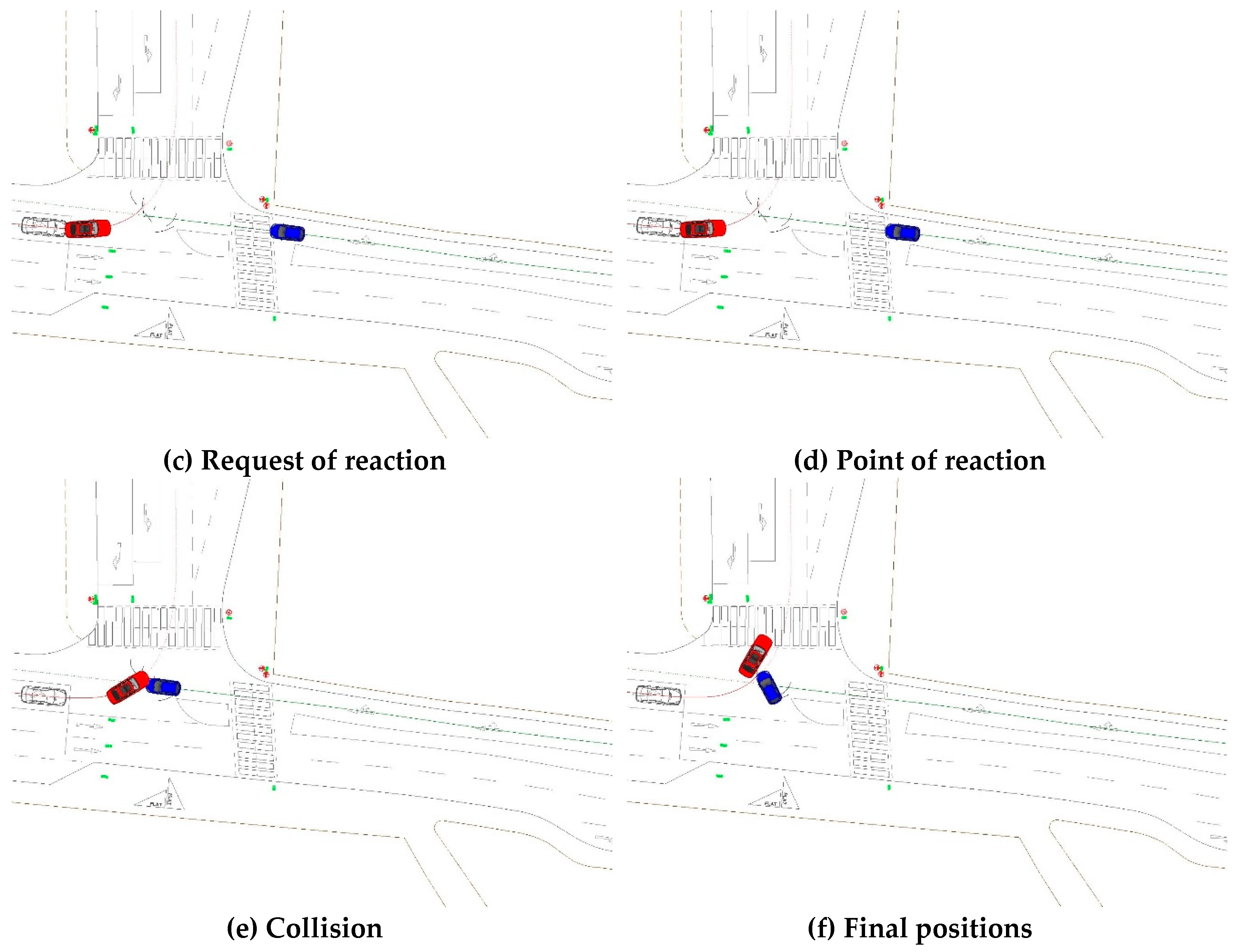

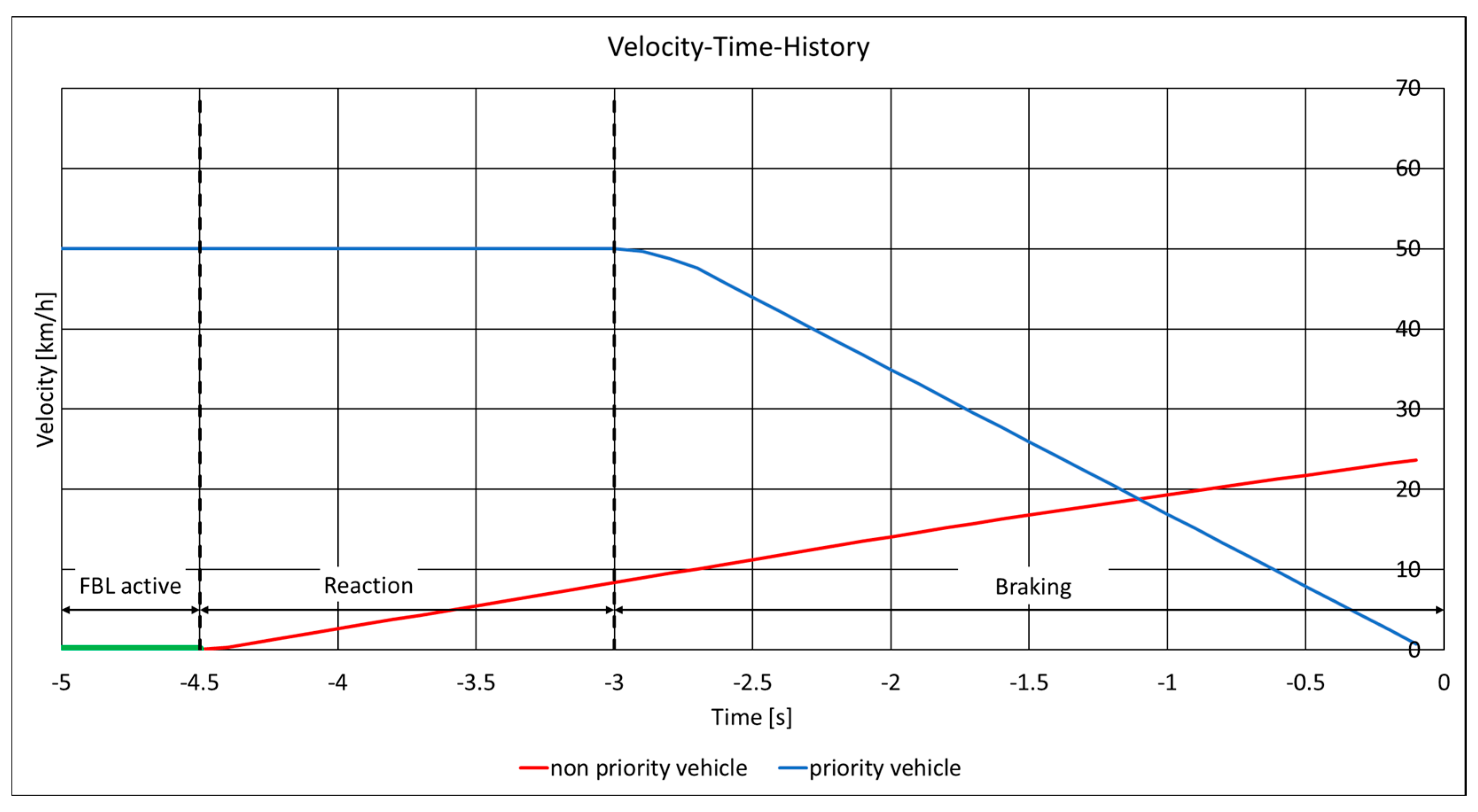

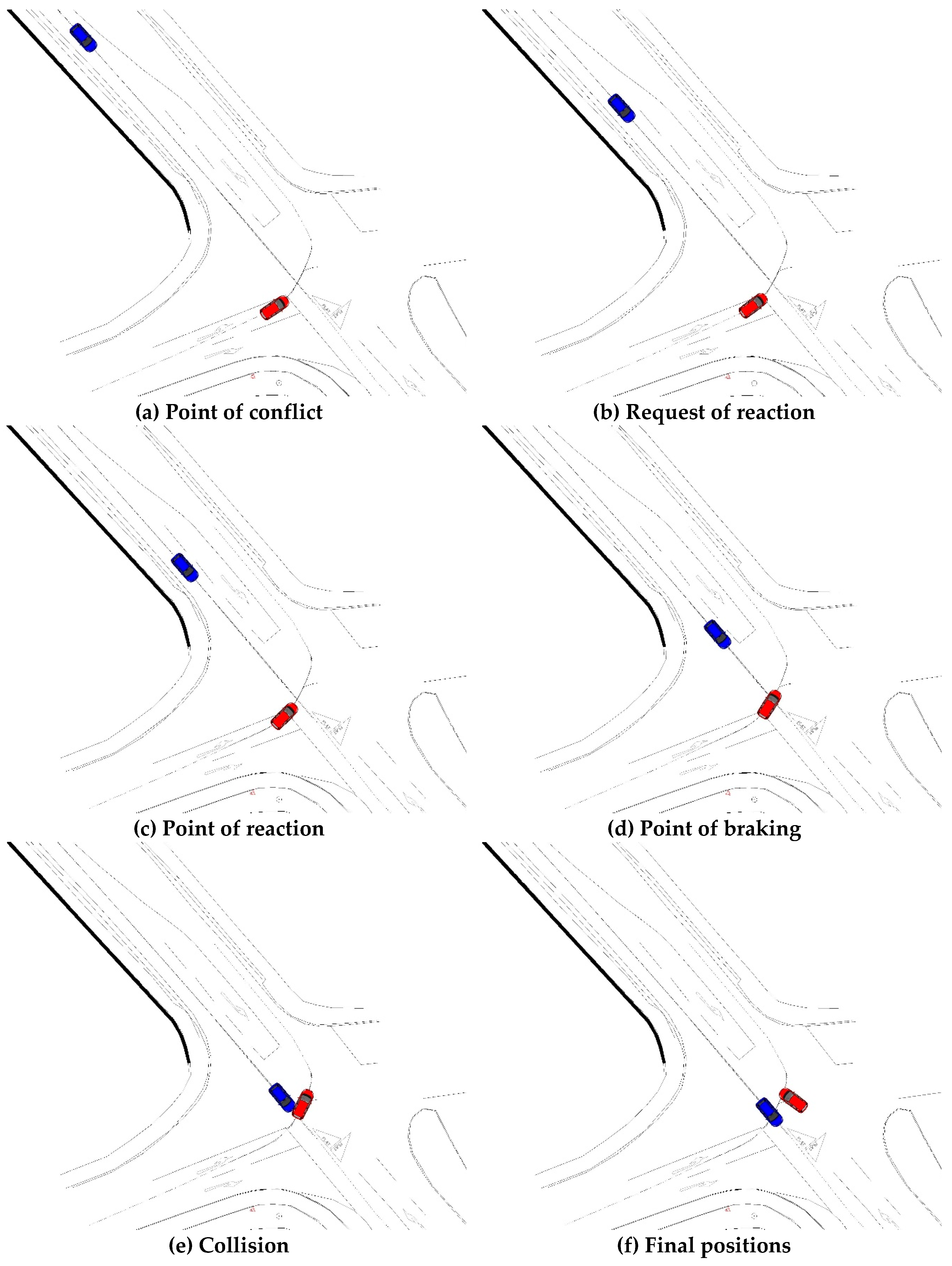

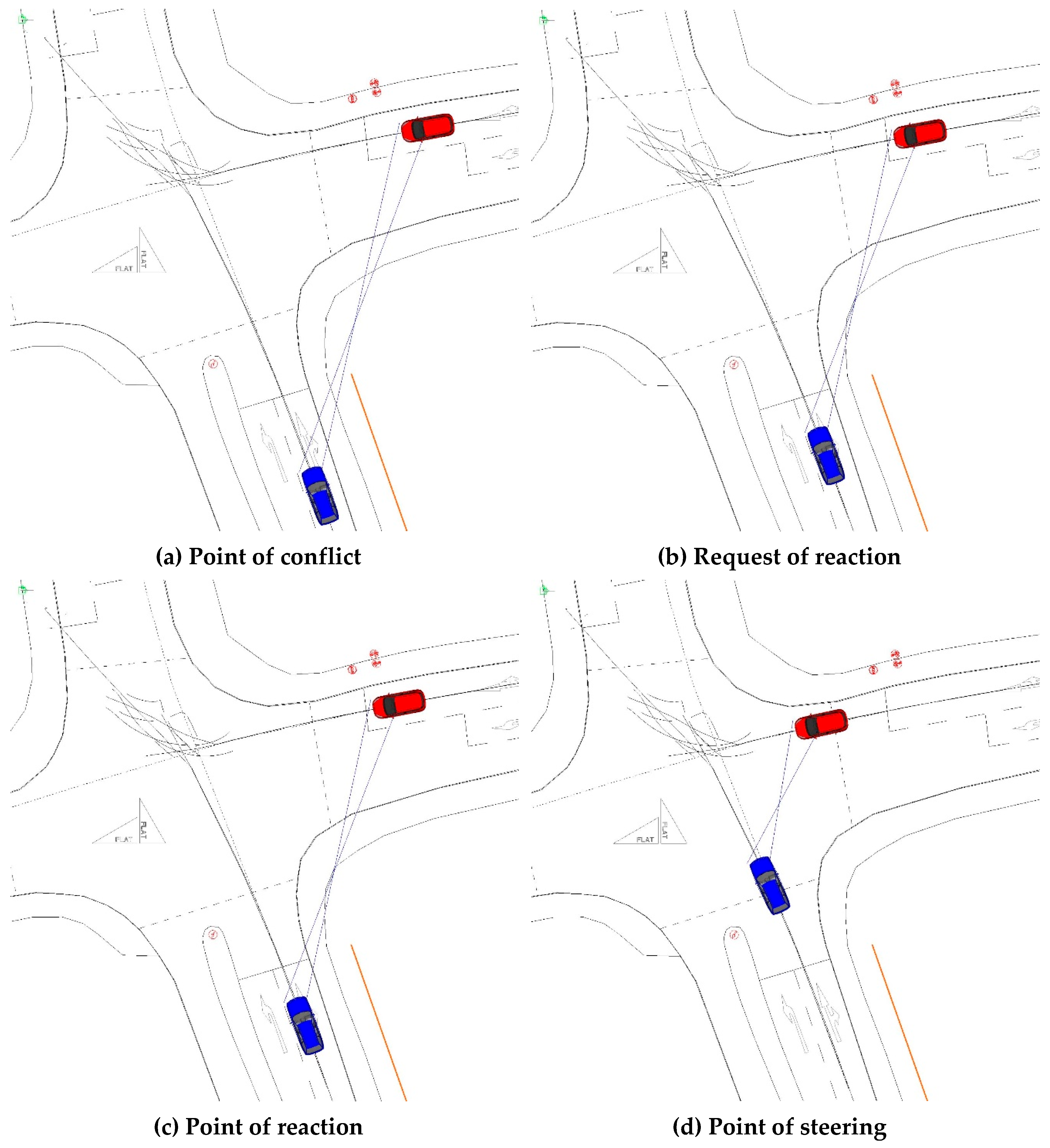

4.1. Reconstruction (“Baseline”)

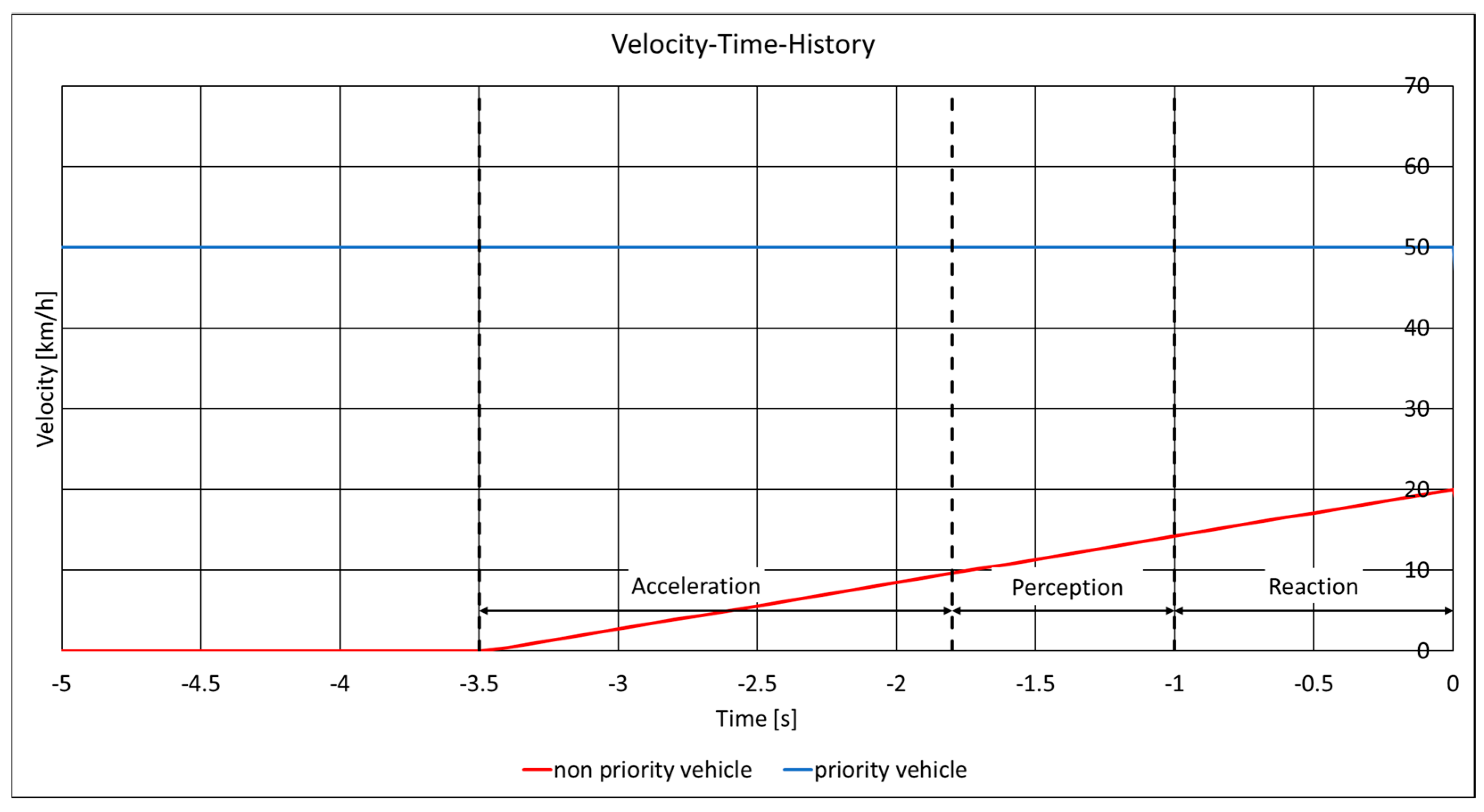

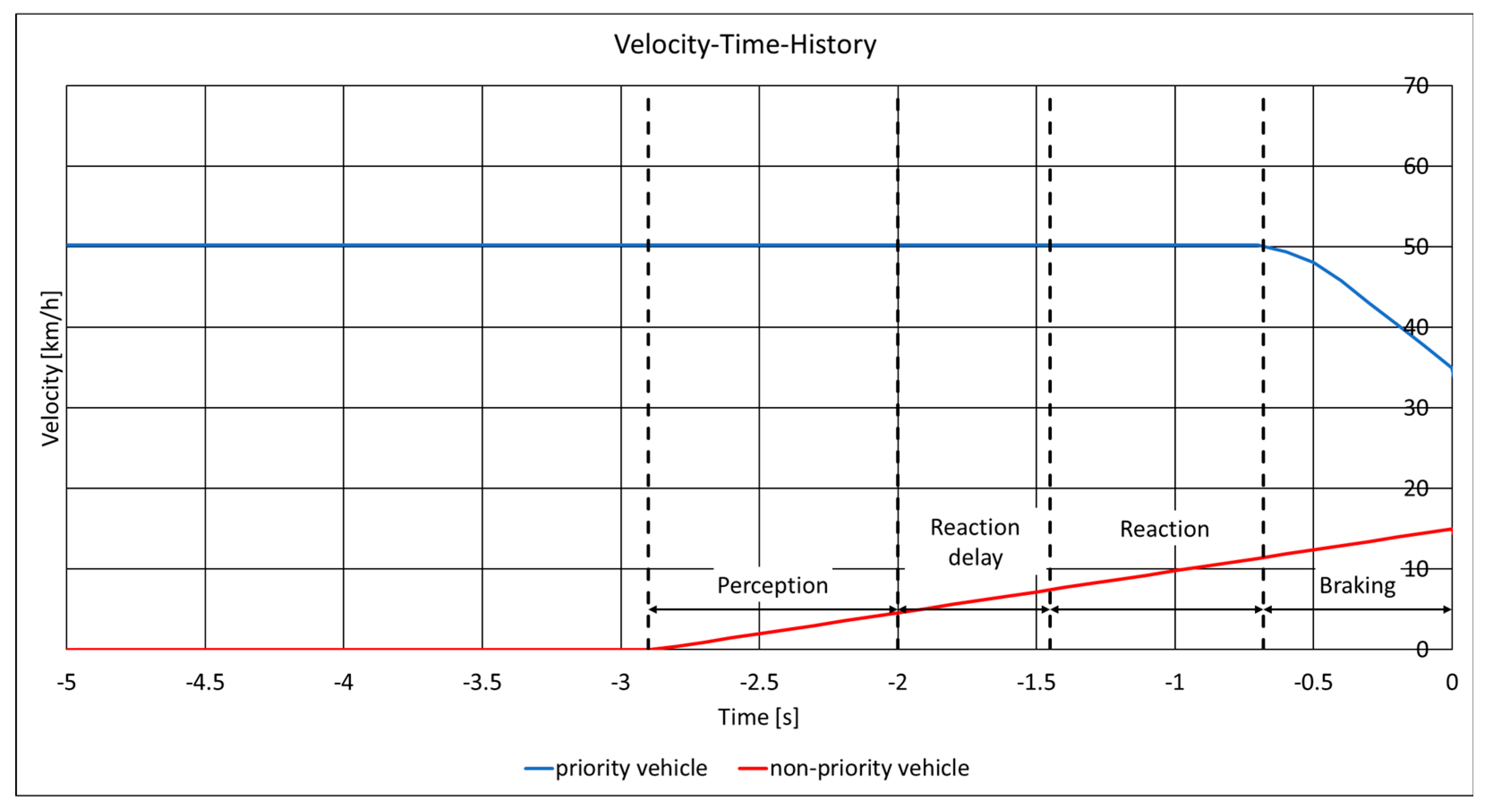

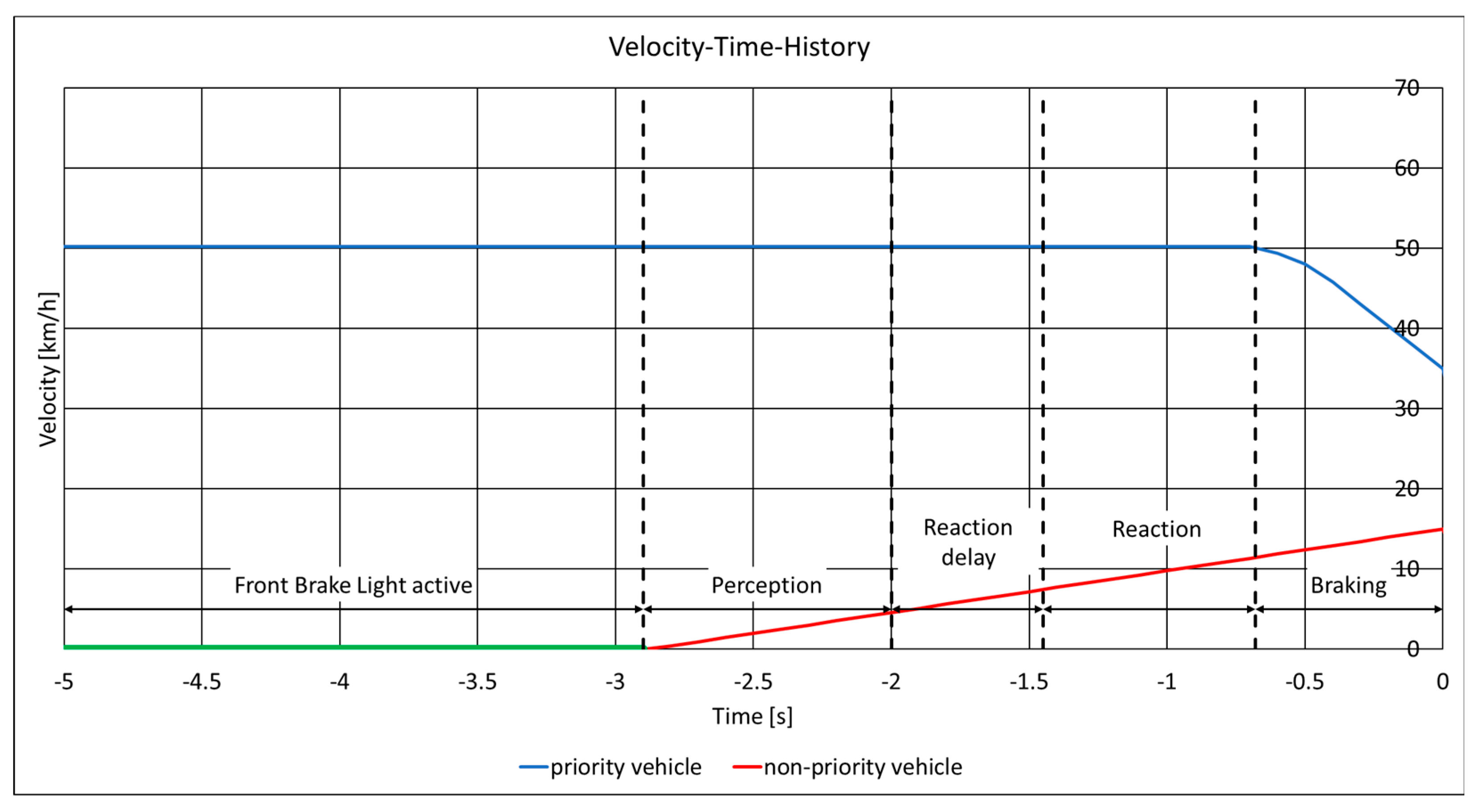

4.2. Counterfactual Simulation (“What-If”, “Treatment”)

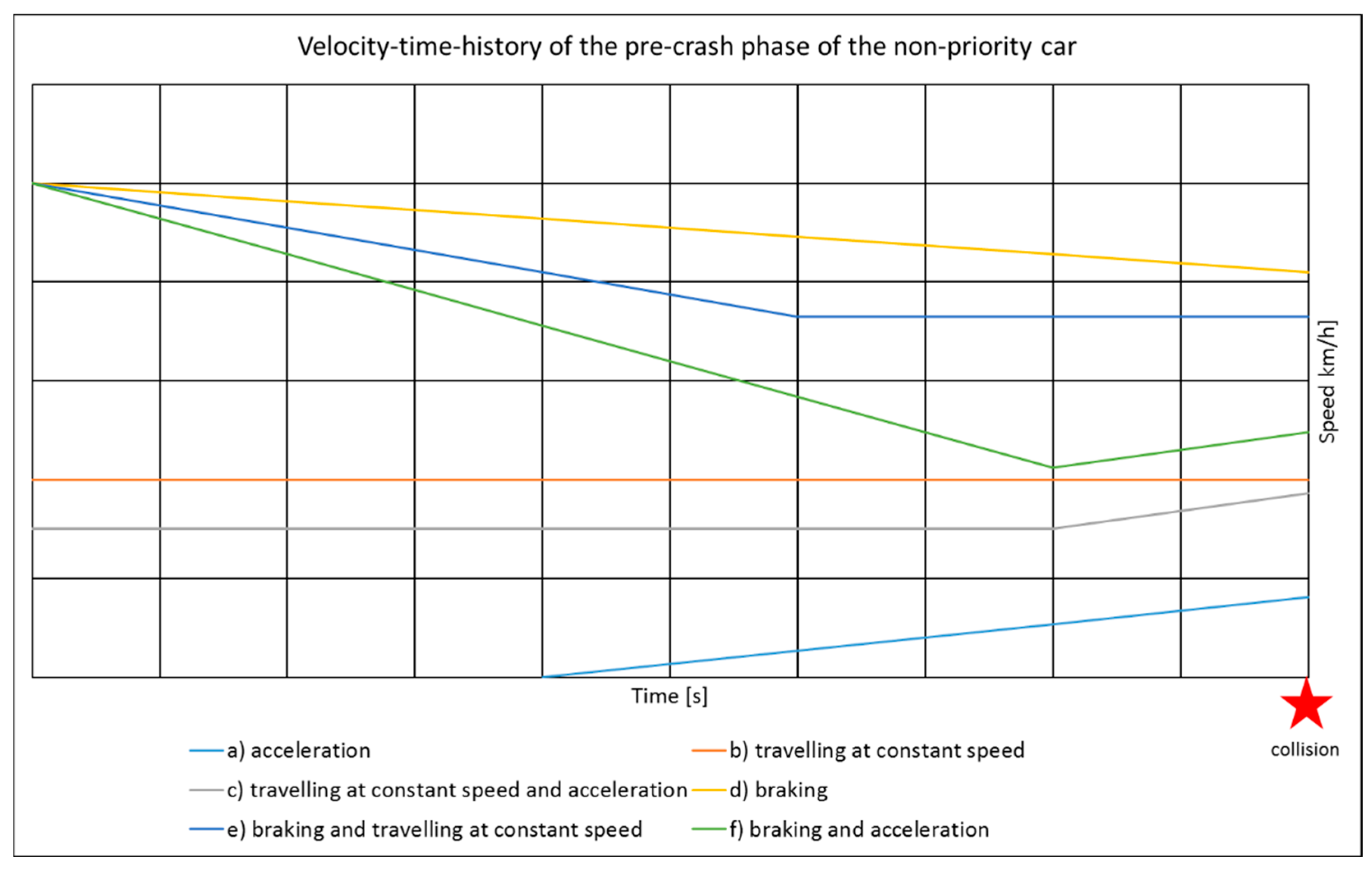

- Scenario a): The non-priority car is stationary and the brake pedal is depressed. The FBL is activated. As soon as the driver starts to move, the FBL is deactivated. The priority car is now requested to react.

- Scenario b): The non-priority car approaches the junction at a constant speed without braking. The FBL is deactivated. A reaction of the priority car is requested at the point where it is clear that the non-priority car is entering the priority car’s lane.

- Scenario c): The non-priority car approaches the junction at a constant speed and starts to accelerate. The FBL is deactivated. A reaction of the priority car is requested at the point where it is clear that the non-priority car is entering the priority car’s lane.

- Scenario d): The non-priority car approaches the junction and is braking but not stopping at the stop line. The FBL is activated all the time. A reaction of the priority car is requested at the point where it is clear that the non-priority car is entering the priority car’s lane.

- Scenario e): The non-priority car is braking first and then travelling at constant speed to the junction. The FBL is activated during the braking phase but is deactivated when driving at constant speed. A reaction of the priority car is requested at the point where it is clear that the non-priority car is entering the priority car’s lane.

- Scenario f): The non-priority car is braking first and then accelerating to the junction. The FBL is activated during the braking phase but is deactivated when driving at constant speed. A reaction of the priority car is requested at the point where it is clear that the non-priority car is entering the priority car’s lane.

4.3. Strategy

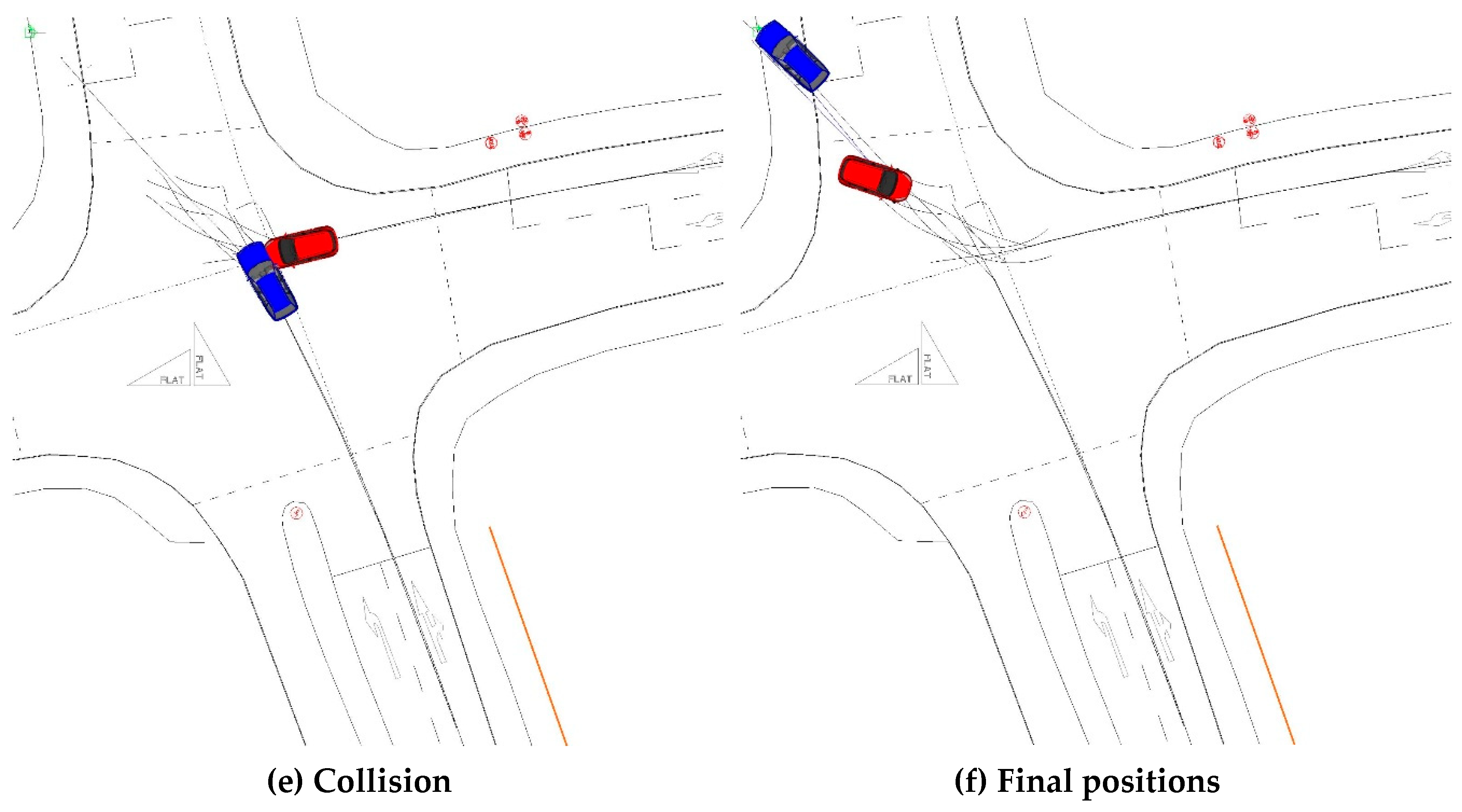

4.3.1. Reaction Braking Time

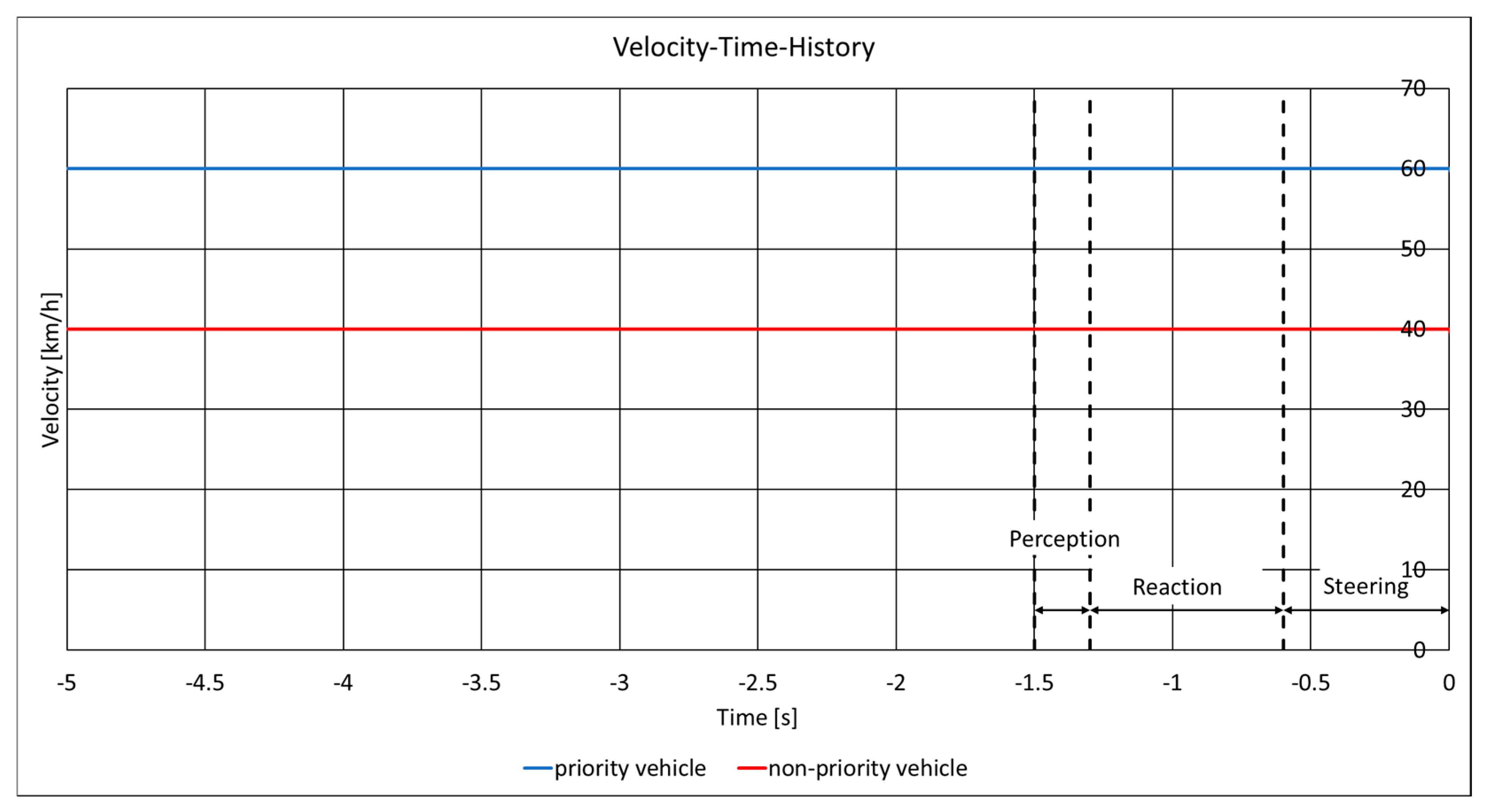

4.3.2. Visibility of the FBL

4.4. Safety Performance Assessment

5. Results

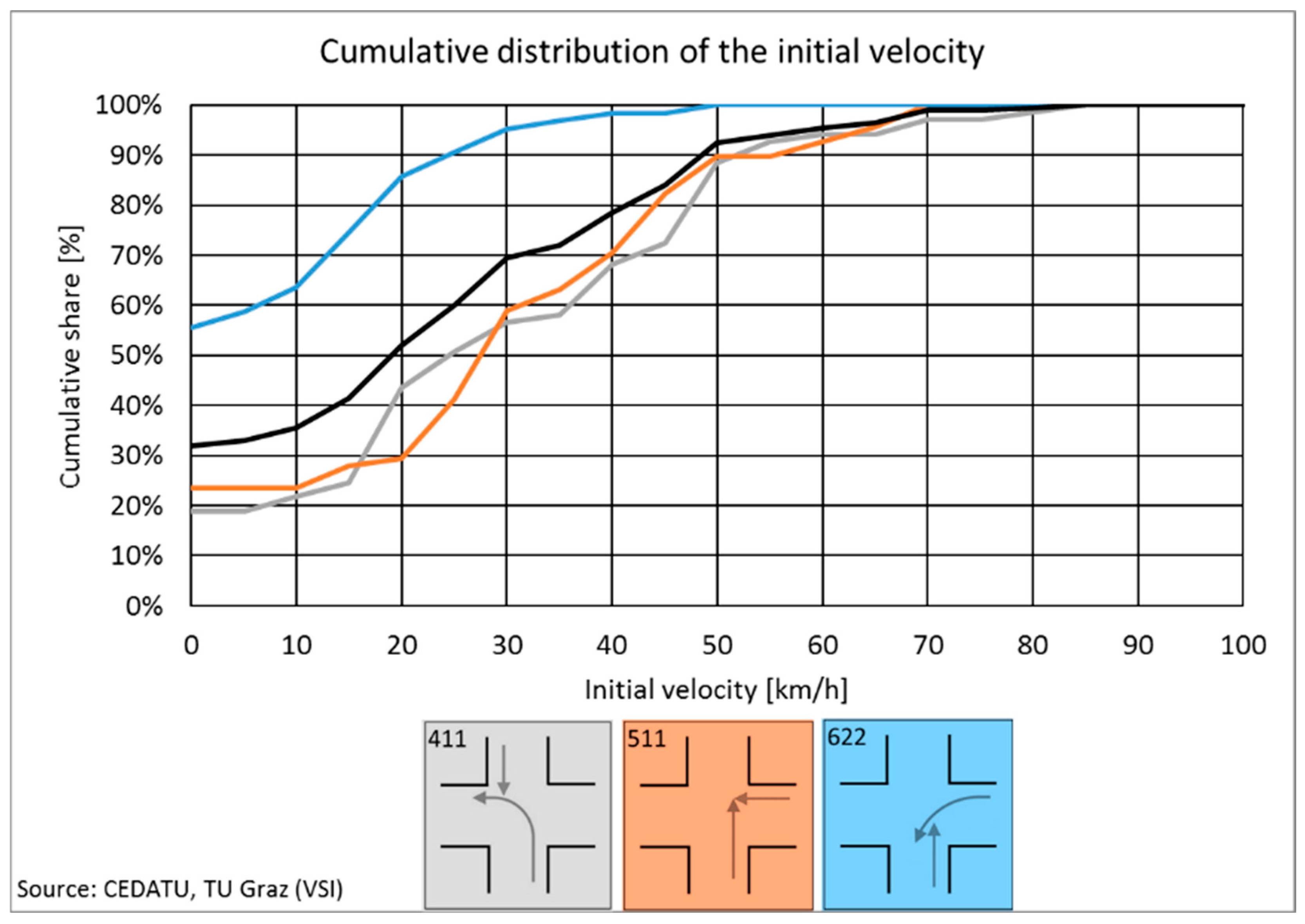

5.1. Pre-Collision Behaviour in the Baseline

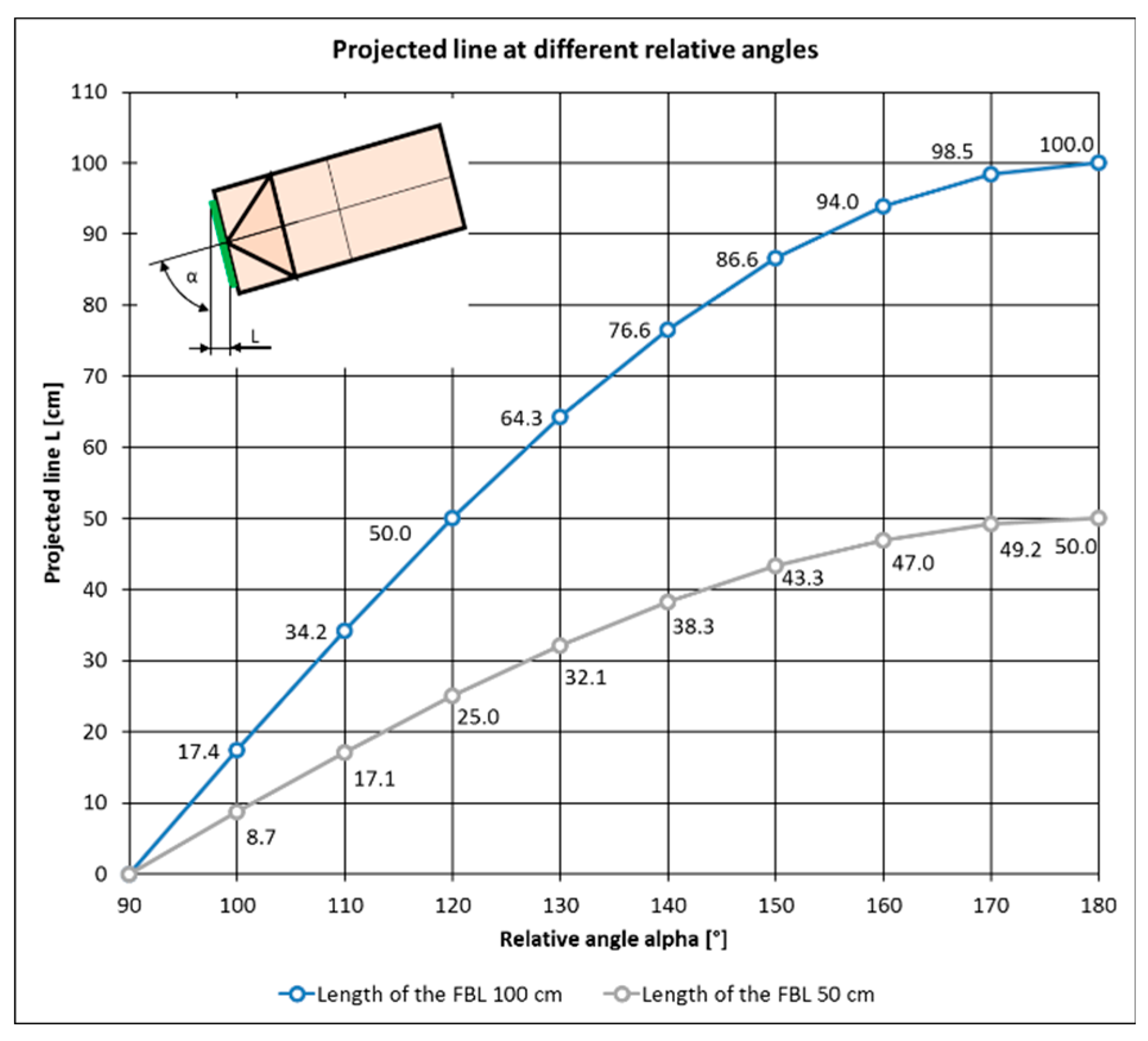

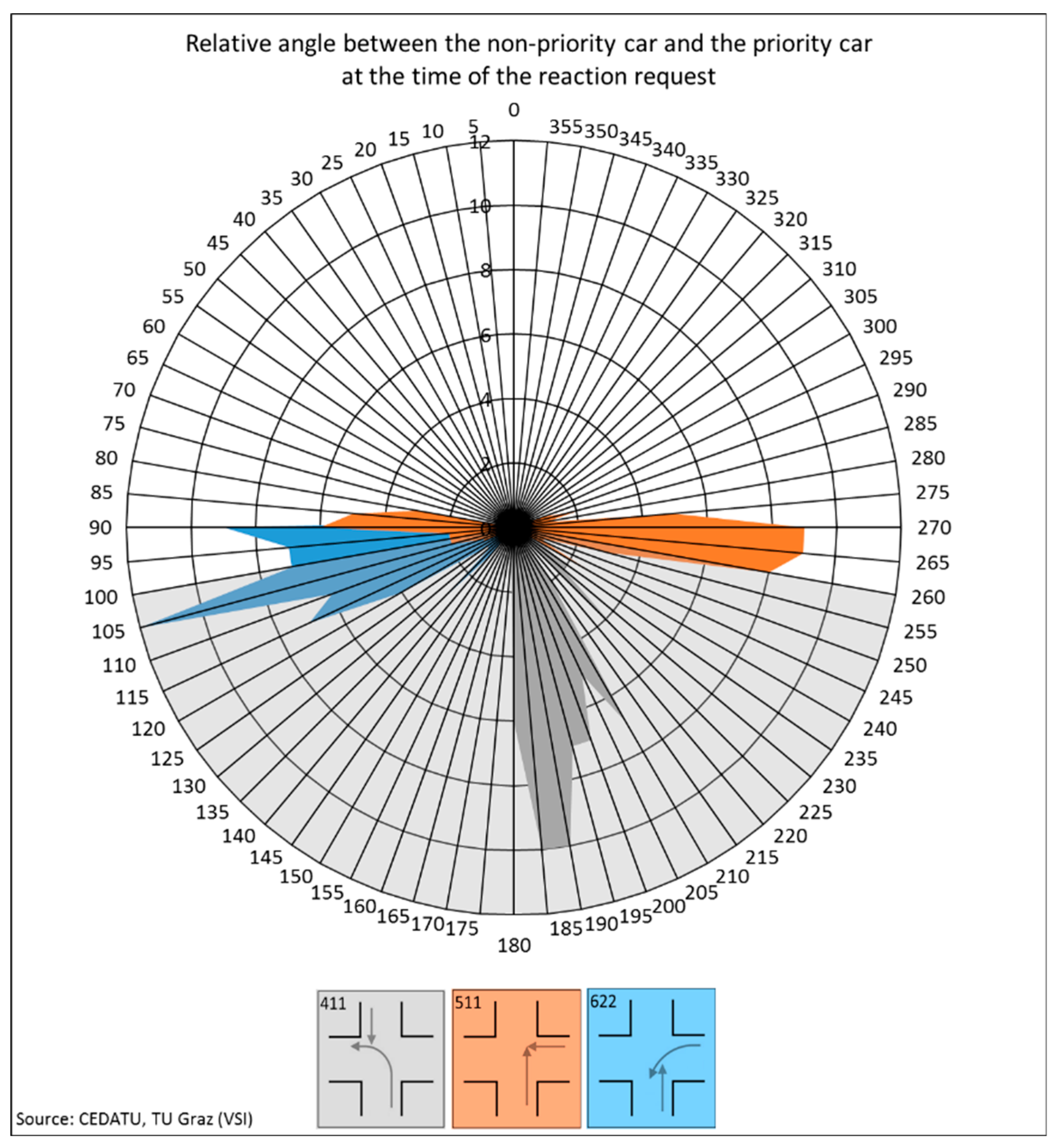

5.2. FBL Visibility

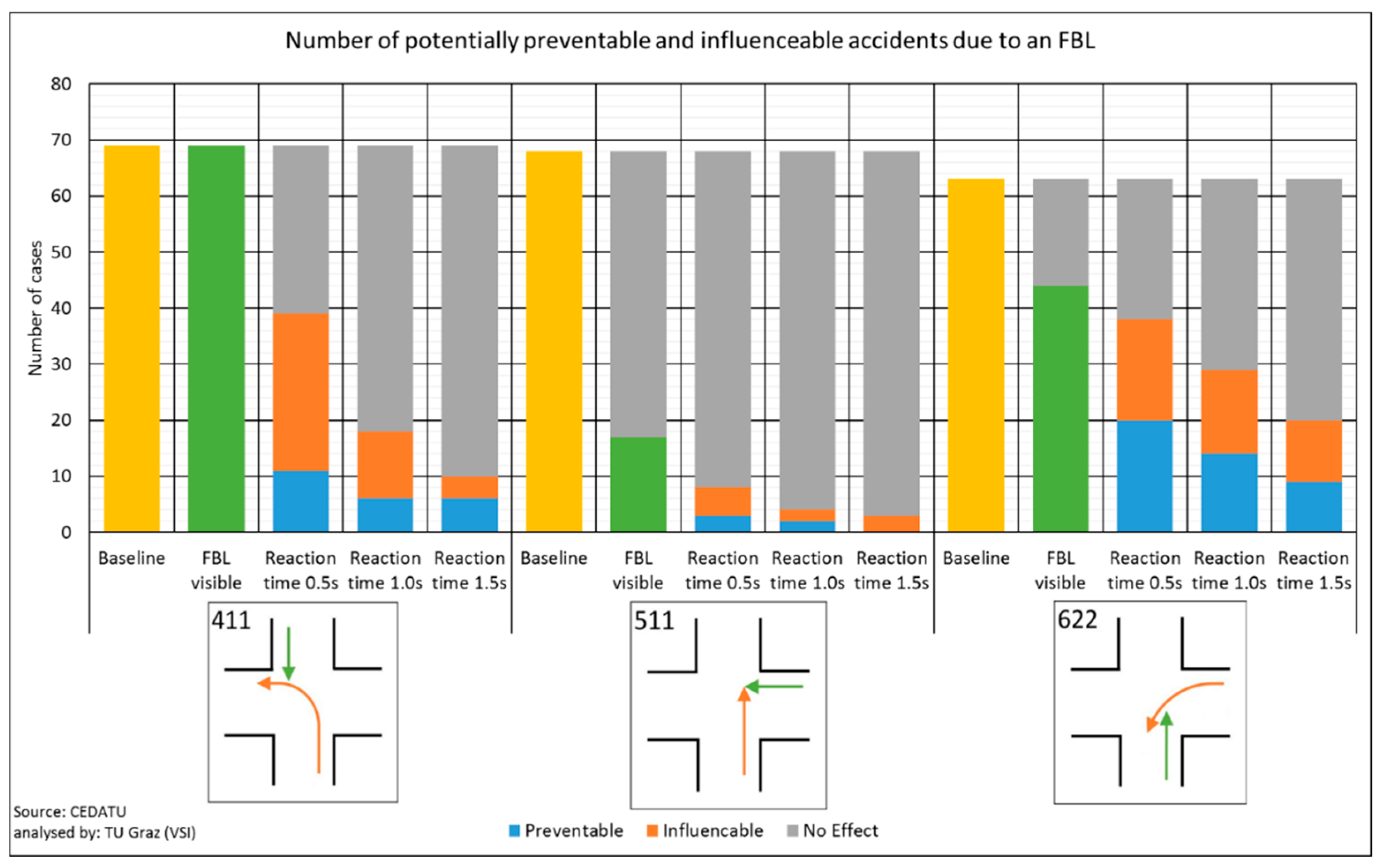

5.3. Avoidance and Mitigation

5.4. Collision Speed and Change of Velocity

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABS | Anti-lock Braking System |

| AEB | Emergency Braking Assist |

| CEDATU | Central Database for In-Depth Accident Study |

| FBL | Front Brake Light |

| FCW | Frontal Collision Warning |

| FOT | Field Operational Tests |

| LTAP/LD | Left Turn Across Path/Left Direction |

| LTAP/OD | Left Turn Across Path/Opposite Direction |

| NCAP | New Car Assessment Programme |

| NDS | Naturalistic Driving Study |

| SCP | Straight Crossing Path |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

Appendix A

| Accident type | Pictogram | Description |

| 311 RT/SDRE |

|

Collision with a vehicle which is turning right at a junction (Right Turn / Same Direction Rear End) |

| 312 RT/SDR |

|

Collision of a vehicle which is turning right with another vehicle which is passing by and moving straight at a junction (Left Turn / Same Direction Right) |

| 313 RT/RTSD |

|

Lateral collision between two vehicles turning right at the same time at a junction (Right Turn / Right Turn Same Direction) |

| 321 LT/SDRE |

|

Collision with a vehicle which is turning left at a junction (Left Turn / Same Direction Rear End) |

| 322 LT/SDL |

|

Collision of a vehicle which is turning left with another vehicle which is overtaking or passing by at a junction (Left Turn / Same Direction Left) |

| 323 LT/LTSD |

|

Lateral collision between two vehicles turning left at the same time at a junction (Left Turn / Left Turn Same Direction) |

| 331 UT/SDJ |

|

Collision at a junction between a vehicle making a u-turn from the right lane and a vehicle travelling straight ahead on the left lane (U-Turn/Same Direction Junction) |

| 332 UD/SD |

|

Collision at mid-block between a vehicle making a u-turn from the right lane and a vehicle travelling straight ahead on the left lane |

| 391 OTSD |

|

Other accidents when turning or making a u-turn, travelling in the same direction (Other Turn/Same Direction) |

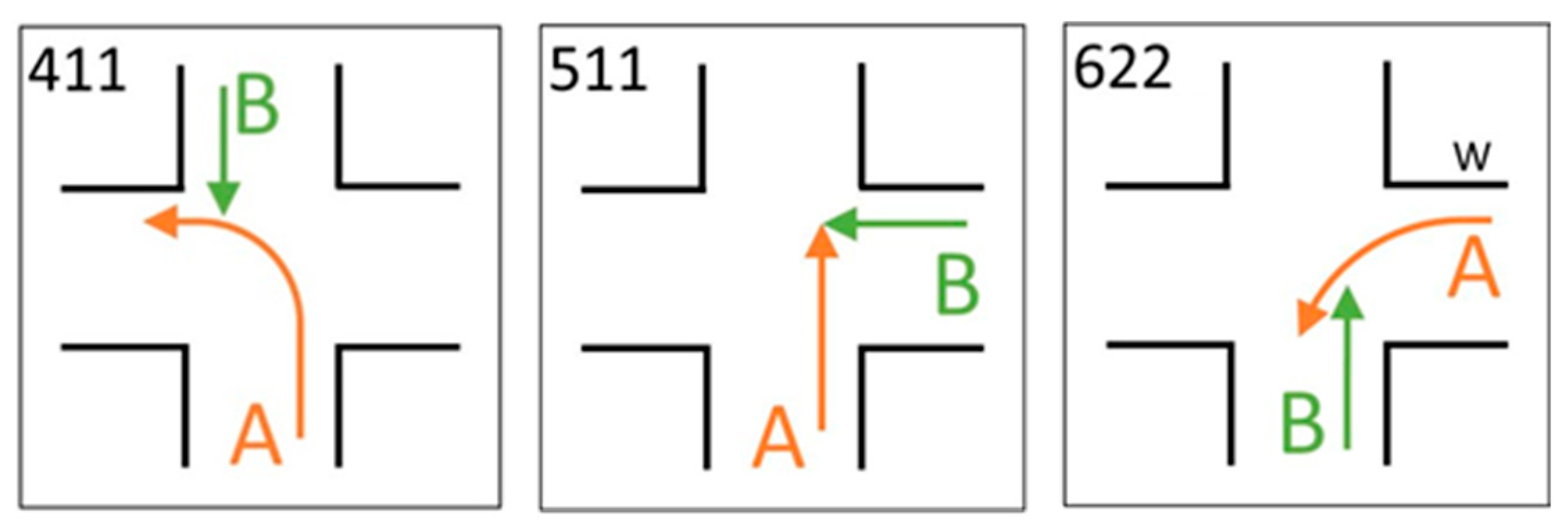

| 411 LTAP/OD |

|

Collision between a vehicle turning left and another vehicle coming from the opposite direction and travelling straight ahead (Left Turn Across Path/Opposite Direction) |

| 421 LT/LTOD |

|

Lateral collision between two vehicles turning left in opposite directions (Left Turn/Left Turn Opposite Direction) |

| 431 RT/LTOD |

|

Collision between a vehicle turning right and another vehicle turning left coming from the opposite direction (Right Turn / Left Turn Opposite Direction) |

| 451 RT/OD |

|

Collision between a vehicle turning right and another vehicle (bicycle, tram) travelling in the opposite direction on a special lane (e.g. cycle lane, tram, right of way) (Right Turn / Opposite Direction) |

| 461 UT/ODJ |

|

Collision between a vehicle making a U-turn and another vehicle travelling in the opposite direction at a junction (U-Turn / Opposite Direction Junction) |

| 462 UT/OD |

|

Collision between a vehicle making a U-turn and another vehicle travelling in the opposite direction at mid-block |

| 491 OT/OD |

|

other accidents when turning or making a U-turn, travelling in opposite direction (Other Turn / Opposite Direction) |

| 511 SCP |

|

Collision at a junction between two vehicles travelling at right angles to each other (Straight Crossing Path) |

| 591 SCPO |

|

Other collision at a junction between two vehicles travelling at right angles to each other (Straight Crossing Path Other) |

| 611 RT/LD |

|

Collision at a junction of a vehicle which is turning right and a vehicle coming from left and is crossing straight (Right Turn / Left Direction) |

| 612 LT/RD |

|

Collision at a junction of a vehicle which is turning left and a vehicle coming from right and is crossing straight (Left Turn / Right Direction) |

| 621 RT/RD |

|

Collision at a junction of a vehicle which is turning right and a vehicle coming from right and is crossing straight (Right Turn / Right Direction) |

| 622 LTAP/LD |

|

Collision at a junction of a vehicle which is turning left and a vehicle coming from left and is crossing straight (Left Turn Across Path / Left Direction) |

| 631 RT/RT |

|

Collision at a junction of a vehicle which is turning right and another vehicle coming from the left, also turning right (Right Turn / Right Direction) |

| 632 LT/LTRD |

|

Collision at a junction between a vehicle turning left and another vehicle coming from the left, also turning left (Left Turn / Left Turn Right Direction) |

| 633 RT/LTRD |

|

Collision at a junction of a vehicle which is turning right and another vehicle coming from the right and turning left (Right Turn / Left Turn Right Direction) |

| 691 OT |

|

Other turning accidents – collisions between vehicles turning either right or left (Other Turning / Left or Right) |

Appendix B

| Accident site | Minor injury | Severe injury | Fatal injury | Total |

| Urban | 10 351 | 1 789 | 56 | 12 196 |

| Rural | 24 758 | 1 596 | 16 | 26 370 |

| Total | 35 109 | 3 385 | 72 | 38 566 |

| Road condition | Minor injury | Severe injury | Fatal injury | Total |

| Dry | 26 727 | 2 631 | 56 | 29 414 |

| Adverse road (wet, snow/snow slush) | 8 382 | 754 | 16 | 9 152 |

| Total | 35 109 | 3 385 | 72 | 38 566 |

| Light condition | Minor injury | Severe injury | Fatal injury | Total |

| Daylight | 25 665 | 2 474 | 55 | 28 194 |

| Darkness, Twilight/Dawn | 4 920 | 547 | 15 | 5 482 |

| Artificial light | 4 524 | 364 | 2 | 4 890 |

| Total | 35 109 | 3 385 | 72 | 38 566 |

| Accident type | Minor injury | Severe injury | Fatal injury | Total |

| RT/SDRE | 907 | 15 | 922 | |

| RT/SDR | 294 | 21 | 315 | |

| RT/RTSD | 74 | 3 | 77 | |

| LT/SDRE | 1 249 | 69 | 1 318 | |

| LT/SDL | 1 174 | 117 | 5 | 1 296 |

| LT/LTSD | 77 | 1 | 78 | |

| UT/SDJ | 190 | 27 | 217 | |

| OTSD | 352 | 16 | 1 | 369 |

| LTAP/OD | 6 489 | 834 | 10 | 7 333 |

| LT/LTOD | 68 | 5 | 73 | |

| RT/LTOD | 109 | 6 | 115 | |

| UT/ODJ | 119 | 15 | 134 | |

| OT/OD | 234 | 18 | 252 | |

| SCP | 14 103 | 1 310 | 35 | 15 448 |

| SCPO | 206 | 20 | 226 | |

| RT/LD | 1 352 | 87 | 4 | 1 443 |

| LT/RD | 1 381 | 75 | 3 | 1 459 |

| RT/RD | 454 | 37 | 491 | |

| LTAP/LD | 5 263 | 649 | 14 | 5 926 |

| RT/RT | 56 | 4 | 60 | |

| LT/LTRD | 388 | 20 | 408 | |

| RT/LTRD | 254 | 15 | 269 | |

| OTLR | 316 | 21 | 337 | |

| All junction accidents | 35 109 | 3 385 | 72 | 38 566 |

| All other accidents | 54 546 | 4 565 | 404 | 59 515 |

| Total | 89 655 | 7 950 | 476 | 98 081 |

Appendix C

| Accident type | Injury severity | Safety performance | Reaction time 0.5s | Reaction time 1.0s | Reaction time 1.5s |

| LTAP/OD | Fatal | Baseline | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| FBL visible | 10 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Preventable | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Influenceable | 5 | 1 | 0 | ||

| No effect | 5 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Severe | Baseline | 19 | 19 | 19 | |

| FBL visible | 19 | 19 | 19 | ||

| Preventable | 4 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Influenceable | 5 | 3 | 0 | ||

| No effect | 10 | 13 | 16 | ||

| Minor | Baseline | 40 | 40 | 40 | |

| FBL visible | 40 | 40 | 40 | ||

| Preventable | 7 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Influenceable | 18 | 8 | 4 | ||

| No effect | 15 | 29 | 33 | ||

| Total | Baseline | 69 | 69 | 69 | |

| FBL visible | 69 | 69 | 69 | ||

| Preventable | 11 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Influenceable | 28 | 12 | 4 | ||

| No effect | 30 | 51 | 59 | ||

| SCP | Fatal | Baseline | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| FBL visible | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Preventable | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Influenceable | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| No effect | 11 | 11 | 11 | ||

| Severe | Baseline | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| FBL visible | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Preventable | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Influenceable | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| No effect | 17 | 19 | 20 | ||

| Minor | Baseline | 37 | 37 | 37 | |

| FBL visible | 9 | 9 | 9 | ||

| Preventable | 2 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Influenceable | 3 | 1 | 3 | ||

| No effect | 32 | 34 | 34 | ||

| Total | Baseline | 68 | 68 | 68 | |

| FBL visible | 17 | 17 | 17 | ||

| Preventable | 3 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Influenceable | 5 | 2 | 3 | ||

| No effect | 60 | 64 | 65 | ||

| LTAP/LD | Fatal | Baseline | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| FBL visible | 12 | 12 | 12 | ||

| Preventable | 4 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Influenceable | 7 | 3 | 4 | ||

| No effect | 2 | 7 | 9 | ||

| Severe | Baseline | 17 | 17 | 17 | |

| FBL visible | 9 | 9 | 9 | ||

| Preventable | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Influenceable | 5 | 3 | 1 | ||

| No effect | 9 | 11 | 13 | ||

| Minor | Baseline | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| FBL visible | 23 | 23 | 23 | ||

| Preventable | 13 | 8 | 6 | ||

| Influenceable | 6 | 9 | 6 | ||

| No effect | 14 | 16 | 21 | ||

| Total | Baseline | 63 | 63 | 63 | |

| FBL visible | 44 | 44 | 44 | ||

| Preventable | 20 | 14 | 9 | ||

| Influenceable | 18 | 15 | 11 | ||

| No effect | 25 | 34 | 43 | ||

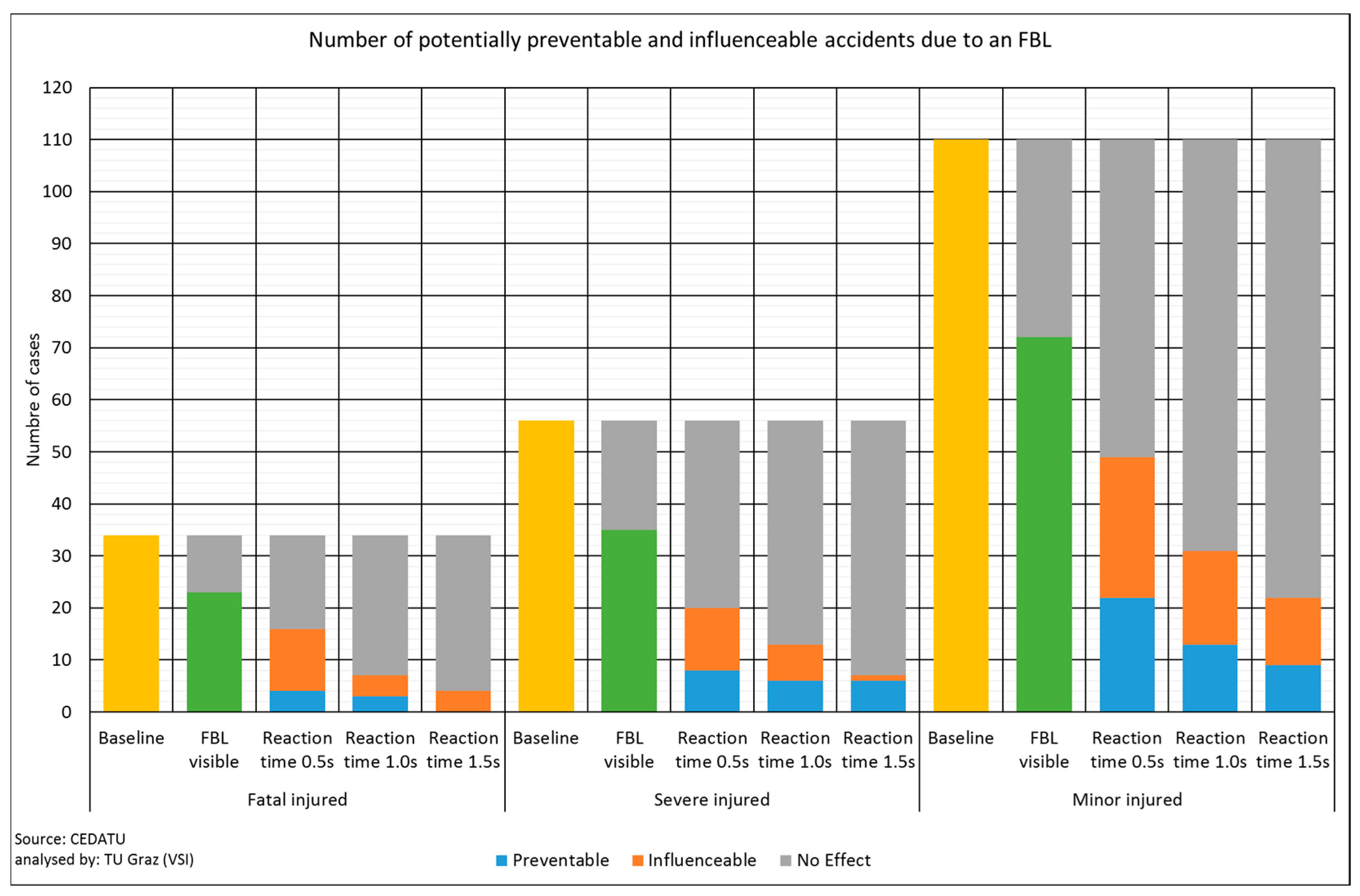

| Total | Fatal | Baseline | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| FBL visible | 23 | 23 | 23 | ||

| Preventable | 4 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Influenceable | 12 | 4 | 4 | ||

| No effect | 18 | 27 | 30 | ||

| Severe | Baseline | 56 | 56 | 56 | |

| FBL visible | 35 | 35 | 35 | ||

| Preventable | 8 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Influenceable | 12 | 7 | 1 | ||

| No effect | 36 | 43 | 49 | ||

| Minor | Baseline | 110 | 110 | 110 | |

| FBL visible | 72 | 72 | 72 | ||

| Preventable | 22 | 13 | 9 | ||

| Influenceable | 27 | 18 | 13 | ||

| No effect | 61 | 79 | 88 | ||

| Total | Baseline | 200 | 200 | 200 | |

| FBL visible | 130 | 130 | 130 | ||

| Preventable | 34 | 22 | 15 | ||

| Influenceable | 51 | 29 | 18 | ||

| No effect | 115 | 149 | 167 |

Appendix D

Appendix D.1. LTAP/OD Accidents

Appendix D.2. LTAP/LD Accidents

Appendix D.3. SCP Accidents

References

- K.M. Marshek, J.F. Cuderman, M.J. Johnson, Performance of Anti-Lock Braking System Equipped Passenger Vehicles - Part I: Braking as a Function of Brake Pedal Application Force, Warrendale, PA, 2002.

- S.-H. Chang, C.-Y. Lin, C.-C. Hsu, C.-P. Fung, J.-R. Hwang, The effect of a collision warning system on the driving performance of young drivers at intersections, Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 12 (2009) 371–380. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Scanlon, R. Sherony, H.C. Gabler, Preliminary potential crash prevention estimates for an Intersection Advanced Driver Assistance System in straight crossing path crashes, in: 2016 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), IEEE, 2016 - 2016, pp. 1135–1140. [CrossRef]

- J. Scanlon, R. Sherony, H. Gabler, Preliminary Effectiveness Estimates for Intersection Driver Assistance Systems in LTAP/OD Crashes, in: FAST-zero'17, 2017.

- J.M. Scanlon, R. Sherony, H.C. Gabler, Injury mitigation estimates for an intersection driver assistance system in straight crossing path crashes in the United States, Traffic Inj Prev 18 (2017) S9-S17. [CrossRef]

- M. Bareiss, J. Scanlon, R. Sherony, H.C. Gabler, Crash and injury prevention estimates for intersection driver assistance systems in left turn across path/opposite direction crashes in the United States, Traffic Inj Prev 20 (2019) S133-S138. [CrossRef]

- U. Sander, Opportunities and limitations for intersection collision intervention-A study of real world 'left turn across path' accidents, Accident Analysis & Prevention 99 (2017) 342–355. [CrossRef]

- U. Sander, N. Lubbe, Market penetration of intersection AEB: Characterizing avoided and residual straight crossing path accidents, Accident Analysis & Prevention 115 (2018) 178–188. [CrossRef]

- C. Zauner, E. Tomasch, W. Sinz, C. Ellersdorfer, H. Steffan, Assessment of the effectiveness of Intersection Assistance Systems at urban and rural accident sites, in: ESAR (Ed.), 6th International Conference on ESAR "Expert Symposium on Accident Research", 2014.

- J.B. Cicchino, Effectiveness of forward collision warning and autonomous emergency braking systems in reducing front-to-rear crash rates, Accident Analysis & Prevention 99 (2017) 142–152. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, S. Tak, J. Kim, H. Yeo, Identifying major accident scenarios in intersection and evaluation of collision warning system, in: I.I.T.S. Conference (Ed.), IEEE ITSC 2017: 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems Mielparque Yokohama in Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan, October 16-19, 2017, IEEE, Piscataway, NJ, 2017, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- R. Spicer, A. Vahabaghaie, G. Bahouth, L. Drees, R. Martinez von Bülow, P. Baur, Field effectiveness evaluation of advanced driver assistance systems, Traffic Inj Prev 19 (2018) S91-S95. [CrossRef]

- H. Liers, T. Ungar, Prediction of the expected accident scenario of future Level 2 and Level 3 cars on German motorways, in: International Research Council on the Biomechanics of Injury (Ed.), 2019 IRCOBI Conference Proceedings, IRCOBI, 2019.

- HLDI, Predicted availability of safety features on registered vehicles — a 2023 update, 40th ed., Arlington, VA, 2023.

- PARTS, Market Penetration of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS), 2024.

- R. Schram, Williams Aled, M. van Ratingen, Ryrber, EURO NCAP’S FIRST STEP TO ASSESS AUTONOMOUS EMERGENCY BRAKING (AEB) FOR VULNERABLE ROAD USERS, in: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) (Ed.), The 24th ESV Conference Proceedings, NHTSA, 2015.

- Euro NCAP, Assessment Protocol - Safety Assist Collision Avoidance, 2024.

- European Parliament And Council, Regulation (EU) 2019/2144 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on type-approval requirements for motor vehicles and their trailers, and systems, components and separate technical units intended for such vehicles, as regards their general safety and the protection of vehicle occupants and vulnerable road users: Regulation (EU) 2019/2144, 2019.

- J. Scholliers, M. Tarkiainen, A. Silla, M. Modijefsky, R. Janse, G. van den Born, Study on the feasibility, costs and benefits of retrofitting advanced driver assistance to improve road safety - Final report, Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- E. Tomasch, S. Smit, Naturalistic driving study on the impact of an aftermarket blind spot monitoring system on the driver’s behaviour of heavy goods vehicles and buses on reducing conflicts with pedestrians and cyclists, Accident Analysis & Prevention 192 (2023) 107242. [CrossRef]

- S.F. Douglass(U.S. Patent No. 1,519,980), 1924.

- O.S. Pirkey(U.S. Patent No. 1,553,959), 1925.

- B.B. Radclyffe, R.P. Fraser(Patent No. GB 493,510A), 1938.

- D.V. Post, R.G. Mortimer, Subjective evaluation of the front-mounted braking signal, University of Michigan, Highway Safety Research Institute, Ann Arbor, Mich., 1971.

- T. Petzoldt, K. Schleinitz, R. Banse, Laboruntersuchung zur potenziellen Sicherheitswirkung einer vorderen Bremsleuchte in Pkw, ZVS - Zeitschrift für Verkehrssicherheit (2017) 19–24.

- T. Petzoldt, K. Schleinitz, R. Banse, Potential safety effects of a frontal brake light for motor vehicles, IET Intelligent Trans Sys 12 (2018) 449–453. [CrossRef]

- D. Eisele, T. Petzoldt, Effects of a frontal brake light on pedestrians’ willingness to cross the street, Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 23 (2024) 100990. [CrossRef]

- L.-F. Bluhm, D. Eisele, W. Schubert, R. Banse, Effects of a frontal brake light on (automated) vehicles on children’s willingness to cross the road, Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 98 (2023) 269–279. [CrossRef]

- M. Monzel, K. Keidel, W. Schubert, R. Banse, Feldstudie zur Erprobung einer Vorderen Bremsleuchte am Flughafen Berlin-Tegel, Zeitschrift für Verkehrssicherheit 64 (2018).

- M. Poliak, J. Frnda, K. Čulík, B. Kirschbaum, Impact of Front Brake Lights from a Pedestrian Perspective, Vehicles 7 (2025) 25. [CrossRef]

- Psychological, safety and environmental impact of the Front Braking Light, AMS 29 (2024) 978–989.

- E. Tomasch, H. Steffan, M. Darok, Retrospective accident investigation using information from court, in: TRA (Ed.), Transport Research Arena 2008 (TRA), 2008.

- J. Bärgman, V. Lisovskaja, T. Victor, C. Flannagan, M. Dozza, How does glance behavior influence crash and injury risk? A ‘what-if’ counterfactual simulation using crashes and near-crashes from SHRP2, Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 35 (2015) 152–169. [CrossRef]

- K.-F. Wu, M.N. Ardiansyah, W.-J. Ye, An evaluation scheme for assessing the effectiveness of intersection movement assist (IMA) on improving traffic safety, Traffic Inj Prev 19 (2018) 179–183. [CrossRef]

- R. Shichrur, N.Z. Ratzon, A. Shoham, A. Borowsky, The Effects of an In-vehicle Collision Warning System on Older Drivers' On-road Head Movements at Intersections, Frontiers in psychology 12 (2021) 596278. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, L. Cao, D.B. Logan, Investigation into the effect of an intersection crash warning system on driving performance in a simulator, Traffic Inj Prev 12 (2011) 529–537. [CrossRef]

- T. Hermitte, C. Thomas, Y. Page, T. Perron, Real-world car accident reconstruction methods for crash avoidance system research, in: SAE (Ed.), SAE Technical Paper Series, SAE International 400 Commonwealth Drive, Warrendale, PA, United States, 2000.

- F. Orsini, G. Gecchele, R. Rossi, M. Gastaldi, A conflict-based approach for real-time road safety analysis: Comparative evaluation with crash-based models, Accident; analysis and prevention 161 (2021) 106382. [CrossRef]

- H. Steffan, PC-CRASH, A Simulation Program for Car Accidents, in: 26th International Symposium on Automotive Technology and Automation, 1993.

- W.E. Cliff, D.T. Montgomery, Validation of PC-Crash - A Momentum-Based Accident Reconstruction Program, in: SAE Technical Papers, 1996.

- A. Moser, H. Hoschopf, H. Steffan, G. Kasanicky, Validation of the PC-Crash Pedestrian Model, in: SAE (Ed.), SAE Technical Paper Series, SAE International 400 Commonwealth Drive, Warrendale, PA, United States, 2000.

- H. Steffan, A. Moser, The Collision and Trajectory Models of PC-CRASH, in: International Congress & Exposition, SAE International, 1996.

- N.A. Rose, N. Carter, An Analytical Review and Extension of Two Decades of Research Related to PC-Crash Simulation Software, in: SAE Technical Paper Series, SAE International400 Commonwealth Drive, Warrendale, PA, United States, 2018.

- H. Steffan, Accident reconstruction methods, Vehicle system dynamics 47 (2009) 1049–1073.

- H. Burg, A. Moser, Handbuch Verkehrsunfallrekonstruktion: Unfallaufnahme, Fahrdynamik, Simulation, 3rd ed., 2017.

- H. Johannsen, Unfallmechanik und Unfallrekonstruktion: Grundlagen der Unfallaufklärung, 3rd ed., Springer Vieweg, Wiesbaden, 2013.

- J. Wille, M. Zatloukal, rateEFFECT - Effectiveness evaluation of active safety systems, in: ESAR (Ed.), 5th International Conference on ESAR "Expert Symposium on Accident Research", 2012, pp. 1–41.

- A. Eichberger, R. Rohm, W. Hirschberg, E. Tomasch, H. Steffan, RCS-TUG Study: Benefit Potential Investigation of Traffic Safety Systems with Respect to Different Vehicle Categories, in: Proceedings of the 22th International Conference on the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles (ESV), 2011, pp. 1–13.

- J. Augenstein, E. Perdeck, J. Stratton, K. Digges, G. Bahouth, Characteristics of Crashes that Increase the Risk of Serious Injuries, Annual Proceedings / Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine 47 (2003) 561–576.

- M. Burckhardt, Reaktionszeiten bei Notbremsvorgängen, Verlag TÜV Rheinland, Köln, 1985.

- P.L. Olson, D.E. Cleveland, P.S. Fancher, L.W. Schneider, Parameters affecting stopping sight distance, Washington, D.C., 1984.

- H. Bäumler, Reaktionszeiten im Straßenverkehr, Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik (2007) 300–307.

- H. Bäumler, Reaktionszeiten im Straßenverkehr, Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik (2007) 334–340.

- H. Bäumler, Reaktionszeiten im Straßenverkehr, Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik (2008) 22–27.

- H. Bäumler, Reaktionszeiten im Straßenverkehr, Sachverständige (2009) 78–83.

- H. Derichs, Vergleich statistischer Auswerteverfahren der experimentell ermittelten Reaktionszeiten von PKW-Fahrern im Straßenverkehr. Diplomarbeit, Köln, 1998.

- Winninghoff, M., Schmedding, K., K.H. Schimmelpfennig, Die Reaktionszeitverlängerung bei Dunkelheit unter Alkohol- und Blendungseinflüssen- Ergebnisse aus Laborversuchen, Verkehrsunfall und Fahrzeugtechnik 39 (2001) 126–131.

- H. Zoeller, W. Hugemann, Zur Problematik der Bremsreaktionszeit im Strassenverkehr, 1999.

- M. Green, “How Long Does It Take to Stop?” - Methodological Analysis of Driver Perception-Brake Times, Transportation Human Factors 2 (2000) 195–216. [CrossRef]

- S. Kaufman, L. Buttenwieser, The State of Scooter Sharing in United States Cities. wagner.nyu.edu/files/faculty/publications/Rudin_ScooterShare_Aug2018_0.pdf.

- C. Hydén, The development of a method for traffic safety evaluation: The Swedish traffic conflicts technique. @Lund, Univ., Diss. 1987, Inst. of Technology Dep. of Traffic Planning and Engineering, Lund, 1987.

- European Commission, Annual statistical report on road safety in the EU, 2024, Brussels, 2024.

- European Commission, Facts and Figures Junctions, Brussels, 2024.

- Simon M., T. Hermitte, Y. Page, Intersection road accident causation: A European view, in: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) (Ed.), The 21st ESV Conference Proceedings, NHTSA, 2009.

- Statistik Austria, Unfalldatenmanagement (UDM). www.statistik.at.

| Minor injury | Severe injury | Fatal injury | Total | |||||

| Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Rural | |

| 411 (LTAP/OD) | 27 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 40 | 29 |

| 511 (SCP) | 35 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 47 | 21 |

| 622 (LTAP/LD) | 20 | 13 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 11 | 25 | 38 |

| Total | 82 | 28 | 24 | 32 | 6 | 28 | 112 | 88 |

| LTAP/OD | SCP | LTAP/LD | Total | |

| Braking | 30 | 12 | 12 | 54 |

| Acceleration | 15 | 18 | 35 | 68 |

| Constant speed | 24 | 38 | 16 | 78 |

| Total | 69 | 68 | 63 | 200 |

| Accident site | Safety performance | Reaction time 0.5s | Reaction time 1.0s | Reaction time 1.5s |

| Urban | Baseline | 112 | 112 | 112 |

| FBL visible | 67 | 67 | 67 | |

| Preventable | 28 | 20 | 12 | |

| Influenceable | 43 | 21 | 13 | |

| No effect | 41 | 71 | 87 | |

| Rural | Baseline | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| FBL visible | 63 | 63 | 63 | |

| Preventable | 23 | 15 | 10 | |

| Influenceable | 33 | 23 | 15 | |

| No effect | 32 | 50 | 63 |

| Accident site | Safety performance | Reaction time 0.5s | Reaction time 1.0s | Reaction time 1.5s |

| Dry road | Baseline | 148 | 148 | 148 |

| FBL visible | 97 | 97 | 97 | |

| Preventable | 41 | 29 | 19 | |

| Influenceable | 52 | 30 | 20 | |

| No effect | 55 | 89 | 109 | |

| Adverse road (wet, snow/snow slush) | Baseline | 52 | 52 | 52 |

| FBL visible | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Preventable | 10 | 6 | 3 | |

| Influenceable | 24 | 14 | 8 | |

| No effect | 18 | 32 | 41 |

| Accident site | Safety performance | Reaction time 0.5s | Reaction time 1.0s | Reaction time 1.5s |

| Daylight | Baseline | 143 | 143 | 143 |

| FBL visible | 94 | 94 | 94 | |

| Preventable | 35 | 26 | 15 | |

| Influenceable | 54 | 30 | 20 | |

| No effect | 54 | 87 | 108 | |

| Darkness, Twilight/Dawn | Baseline | 35 | 35 | 35 |

| FBL visible | 26 | 26 | 26 | |

| Preventable | 9 | 5 | 4 | |

| Influenceable | 15 | 9 | 5 | |

| No effect | 11 | 21 | 26 | |

| Artificial light | Baseline | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| FBL visible | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Preventable | 7 | 4 | 3 | |

| Influenceable | 7 | 5 | 3 | |

| No effect | 8 | 13 | 16 |

| Injury severity | Cases | Baseline | Reaction time 0.5s | Reaction time 1.0s | Reaction time 1.5s | |

| Minor | All | 110 | 44.8 (15.9) | 28.8 (23.4) | 36.3 (23.5) | 41.6 (22.2) |

| FBL visible | 72 | 46.4 (16.6) | 27.7 (24.3) | 36.3 (24.7) | 42.6 (23.5) | |

| Severe | All | 56 | 56.2 (24.3) | 36.9 (30.1) | 45.2 (31.3) | 49.2 (33.5) |

| FBL visible | 35 | 60.0 (25.9) | 41.3 (32.3) | 50.1 (32.8) | 54.1 (35.6) | |

| Fatal | All | 34 | 70.9 (20.5) | 51.2 (31.9) | 59.9 (32.0) | 69.6 (23.6) |

| FBL visible | 23 | 69.7 (21.0) | 54.3 (31.4) | 62.4 (33.3) | 72.4 (24.4) | |

| Injury severity | Cases | Car | Baseline | Reaction time 0.5s | Reaction time 1.0s | Reaction time 1.5s |

| Minor | 72 | priority | 20.2 (10.2) | 12.3 (12.2) | 15.6 (12.5) | 18.1 (12.8) |

| non-priority | 20.6 (10.4) | 12.5 (12.6) | 15.8 (13.1) | 18.1 (13.2) | ||

| Severe | 35 | priority | 29.7 (12.7) | 18.9 (16.4) | 22.5 (17.0) | 22.6 (16.6) |

| non-priority | 31.0 (15.0) | 20.5 (18.6) | 24.8 (19.6) | 24.8 (19.6) | ||

| Fatal | 23 | priority | 35.4 (14.6) | 26.8 (18.1) | 32.4 (20.9) | 37.3 (18.5) |

| non-priority | 44.4 (19.1) | 34.3 (23.2) | 40.3 (24.6) | 45.4 (20.4) | ||

| Total | 130 | priority | 25.5 (13.2) | 16.6 (15.4) | 20.4 (16.6) | 22.7 (16.5) |

| non-priority | 27.6 (16.2) | 18.5 (18.3) | 22.5 (19.6) | 24.7 (19.1) |

| Accident type | Injury severity | Safety performance | Reaction time 0.5s | Reaction time 1.0s | Reaction time 1.5s |

| LTAP/OD | Minor injury | Preventable | 95 | 41 | 41 |

| Influenceable | 244 | 109 | 55 | ||

| Severe injury | Preventable | 15 | 11 | 11 | |

| Influenceable | 19 | 11 | 0 | ||

| Fatal injury | Preventable | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Influenceable | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| SCP | Minor injury | Preventable | 64 | 64 | 0 |

| Influenceable | 96 | 32 | 96 | ||

| Severe injury | Preventable | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Influenceable | 11 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Fatal injury | Preventable | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Influenceable | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| LTAP/LD | Minor injury | Preventable | 173 | 107 | 80 |

| Influenceable | 80 | 120 | 80 | ||

| Severe injury | Preventable | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Influenceable | 16 | 10 | 4 | ||

| Fatal injury | Preventable | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Influenceable | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | Minor injury | Preventable | 332 | 212 | 121 |

| Influenceable | 420 | 261 | 231 | ||

| Severe injury | Preventable | 31 | 21 | 21 | |

| Influenceable | 46 | 27 | 4 | ||

| Fatal injury | Preventable | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Influenceable | 2 | 2 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).