1. Introduction

In the last decades, the widespread adoption of Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) electrical, electronic, and electromechanical (EEE) components has revolutionized the development of space technologies. This shift, driven by the pursuit of cost-effective and rapid advancements, raises critical questions about the reliability of these components under harsh space conditions. In this context, Silicon Photomultipliers (SiPMs) have emerged as highly attractive detectors for various space applications due to their high photon detection efficiency (PDE), low power consumption, compact size, and immunity to magnetic fields [

1,

2]. These characteristics enable efficient operation in low-light conditions and integration into lightweight space instruments, making SiPMs ideal for missions requiring precise particle detection [

3,

4]. SiPMs have recently been employed in a wide range of space-based applications, including the detection of transient gamma-ray emissions [

5], the measurement of high-energy cosmic rays [

6,

7,

8,

9], and the coincidence detection of gamma-ray bursts associated with gravitational wave events [

10]. Beyond space applications, SiPMs are also widely utilized in terrestrial domains, such as optical communication systems [

11], and quantum optics experiments [

12,

13].

However, the space environment poses significant challenges for EEE, including SiPMs, particularly due to exposure to ionizing radiation, primarily from trapped electrons and protons. Such radiation can induce defects in the silicon lattice, leading to increased dark current and dark count rate, while typically preserving other intrinsic properties like gain, PDE, or breakdown voltage [

14,

15,

16]. This degradation can impair the detector’s ability to resolve single-photon events, thereby affecting overall performance during extended missions. From 2020 to 2024, we conducted an in-orbit experiment to evaluate the long-term performance of SiPMs in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), using the LabOSat-01 (LS-01) [

17] payload onboard the ÑuSat-7 satellite (COSPAR-ID: 2020-003B). Throughout the 1460-day mission, the four SiPMs exhibited a progressive increase in dark current—up to a factor of 500—consistent with the radiation-induced degradation reported in previous ground-based studies [

18,

19,

20]. Towards the end of the mission, as the satellite’s altitude decreased, a gradual increase in internal temperature was observed. This coincided with a slight reduction in dark current, suggesting a possible temperature-driven annealing effect. These findings confirm the expected degradation behavior and also point to the potential of thermal recovery mechanisms under space conditions.

To mitigate accumulated radiation-induced damage, thermal annealing [

21] is a viable recovery technique. This process facilitates the recombination of defects within the crystal lattice, thereby reducing dark current and partially restoring the SiPM’s performance. Studies have demonstrated that annealing efficacy is temperature-dependent, with higher temperatures accelerating recovery [

22]. However, even at relatively low temperatures, some degree of passive recovery has been observed, which is particularly relevant for space applications where thermal control may be limited [

19,

23]. Gu et al. [

24] demonstrated significant performance restoration using in-situ current annealing, where localized heating was achieved by forward biasing the device during irradiation. While effective, this method applies high current directly to the SiPM, potentially introducing additional stress or degradation. Additionally, recent studies have investigated the thermal behavior of irradiated SiPMs, highlighting the role of self-heating due to increased dark current as a potential factor influencing their performance in orbit [

25]. These findings reinforce the importance of understanding and controlling thermal effects in space-based SiPM applications, both for performance stability and for enabling recovery strategies such as annealing.

This work presents an experimental study on the irradiation of SiPMs under controlled conditions, analyzing the impact of proton-induced damage on sensor performance. A thermal annealing-based recovery method is explored to evaluate its effectiveness in restoring key electrical parameters. For this purpose, we studied different heater geometries, fabricated directly on a printed circuit board (PCB). This procedure makes integration into lightweight payloads feasible. The power consumption and the energy required to recover the sensor were studied. The findings aim to inform strategies for the reliable use of SiPMs in space environments, supporting their integration into future scientific and commercial space missions.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment was conducted at the EDRA (

Ensayos de Daño por Radiación y Ambiente) [

26] facility of the TANDAR heavy-ion accelerator, located at

Centro Atómico Constituyentes (CNEA) in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The TANDAR accelerator is a vertical electrostatic tandem system capable of operating with both protons and heavy ions. This facility is specifically designed to attenuate ion flux, enabling the controlled simulation of LEO radiation conditions for space-related experiments.

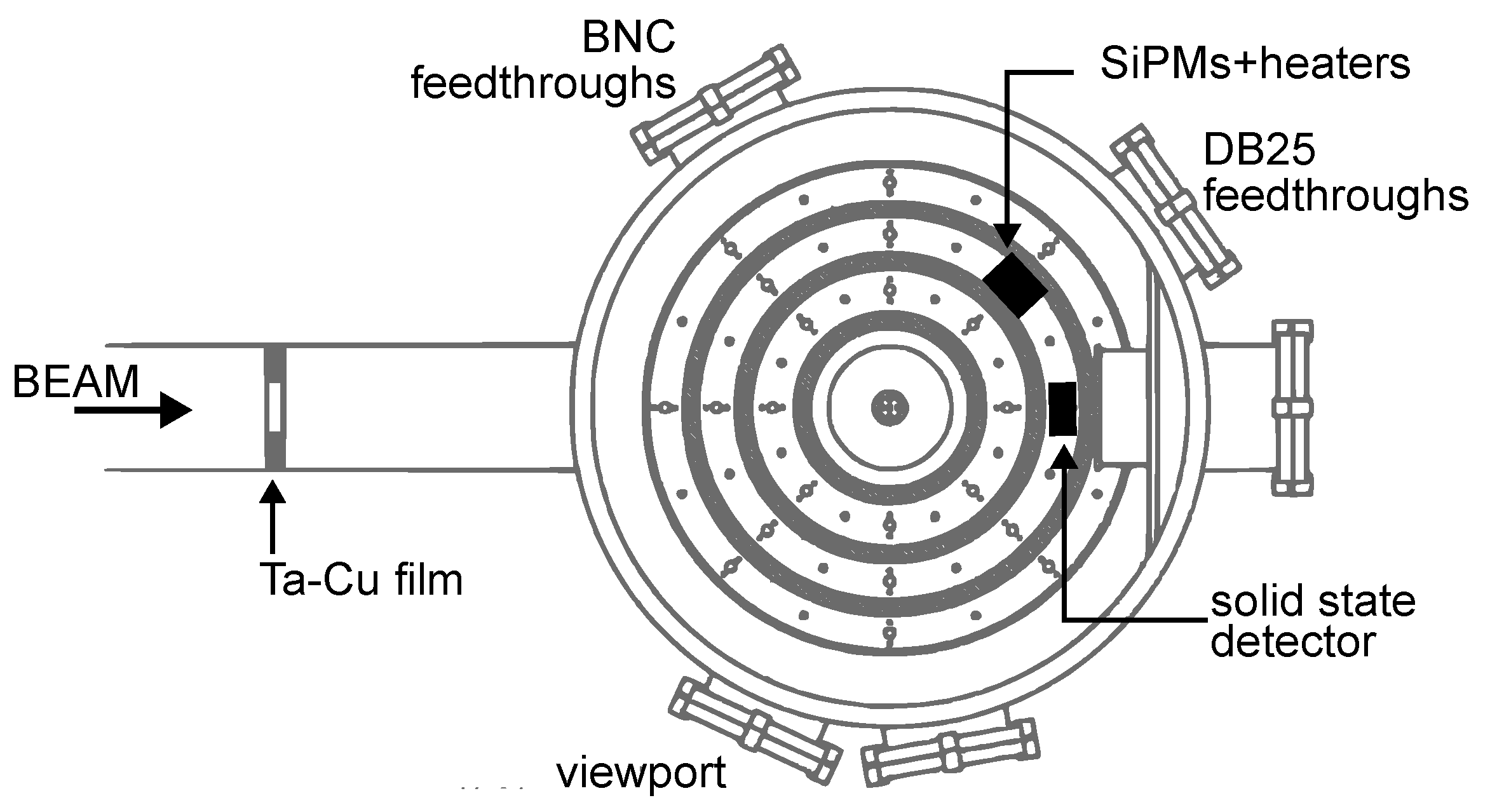

Within the EDRA irradiation line

Figure 1, a 72 µm-thick Tantalum-Copper (Ta-Cu) foil was placed at 6 meters to the target to attenuate the proton flux. This foil contains 100 perforations, each with an average diameter of 31 µm, enabling a flux reduction of up to 1900 times. With this configuration, and by setting the accelerator to its lowest operational current, a proton flux as (4.9 ± 0.2)×10

5 s

−1cm

−2 was achieved inside the vacuum chamber.

The vacuum chamber is equipped with a set of remotely controlled concentric rings, each featuring a patterned aperture system that allows for the precise positioning of different structures as beam targets. These rings can be adjusted from the accelerator control room, enabling the selection of various shielding configurations or the replacement of samples under the proton beam. The chamber operates at a vacuum pressure of 10−5 bar, ensuring controlled irradiation conditions.

2.1. Heater Design

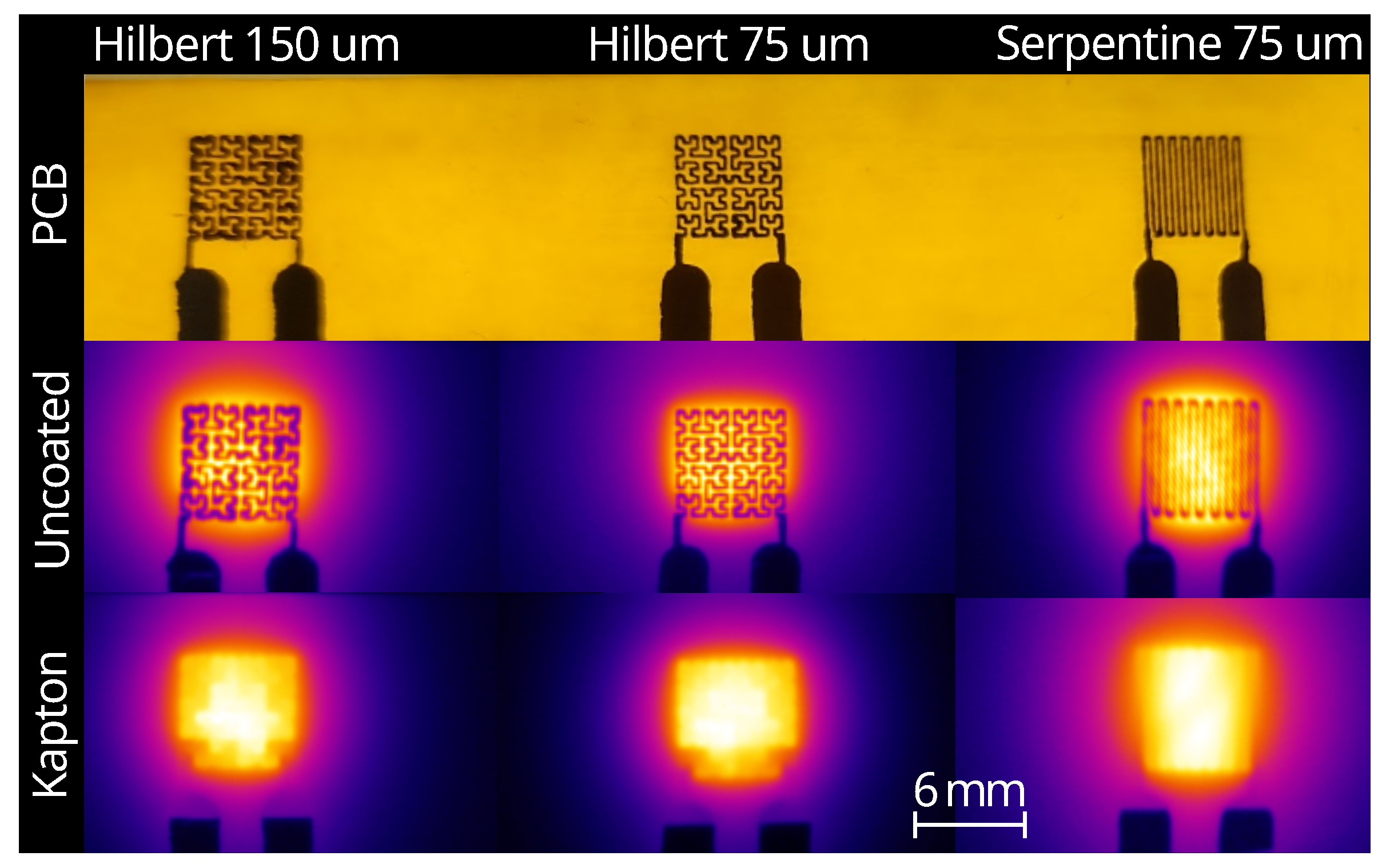

To enable controlled thermal annealing during proton irradiation, three distinct heater prototypes were designed and integrated into PCBs. The three heater prototypes were fabricated on separate PCBs, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Prior to irradiation, a comprehensive characterization of each design was conducted, following these evaluation criteria: power consumption, minimum current, and heat uniformity.

The evaluated heater designs are based on two distinct geometries: a serpentine pattern[

27] and a Hilbert curves [

28,

29]. The serpentine heater and one of the Hilbert designs were manufactured with a wire width of 75 µm, while an additional Hilbert variant was designed with a wider pitch of 150 µm.

A qualitative assessment of the heat distribution uniformity was conducted using thermographic imaging (

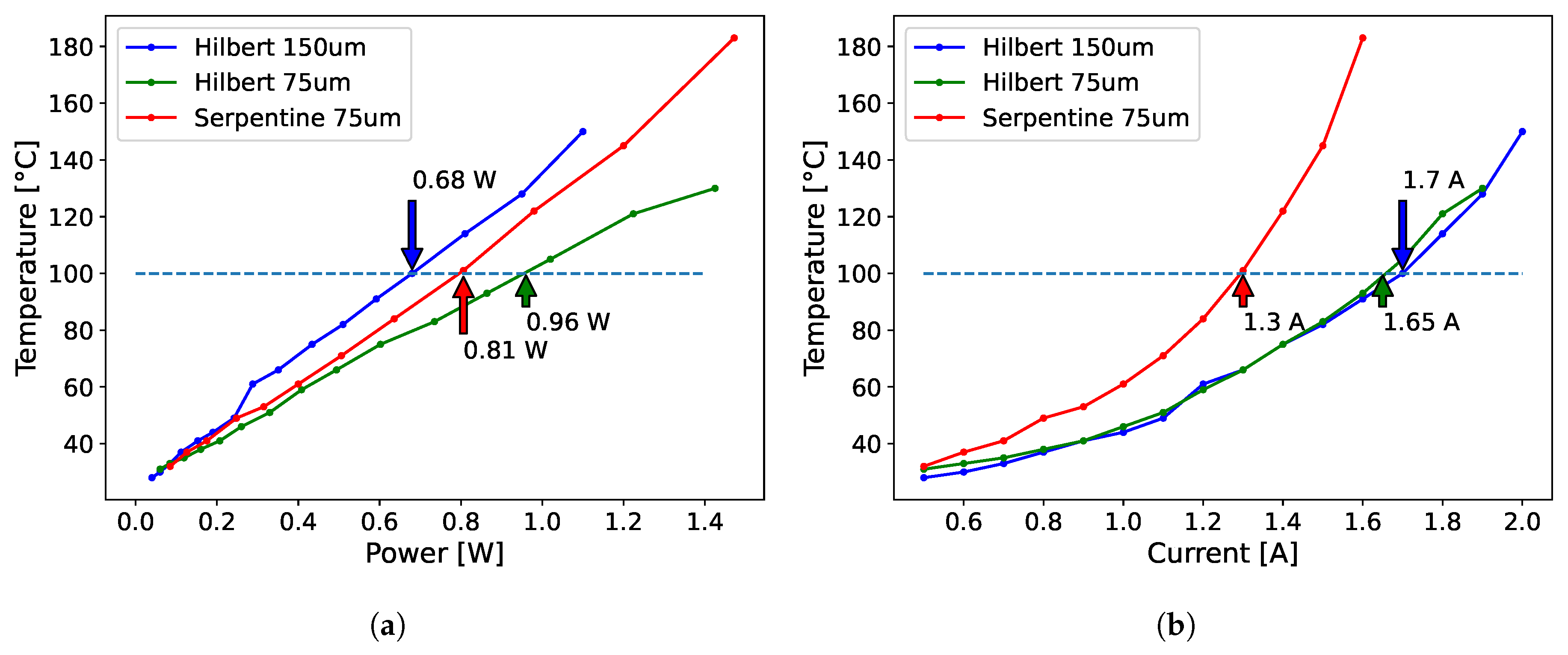

Figure 2). After applying a Kapton tape layer, improved thermal uniformity was observed in the serpentine structure, as the pad corners in the Hilbert curve design exhibited uneven heat distribution. The power consumption of each heater depends on the track resistance, which can be adjusted by modifying the trace width and length. The complete power and current consumption profiles as a function of temperature are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 3, respectively. These profiles illustrate the measured electrical requirements to reach the target temperature of 100 °C for each heater design.

Based on these observations, the serpentine geometry with a 75 µm wire width was selected for subsequent irradiation experiments. This configuration exhibited the most uniform thermal distribution in thermographic analysis and demonstrated the lowest current consumption among the prototypes, making it the most suitable choice for power-constrained space applications.

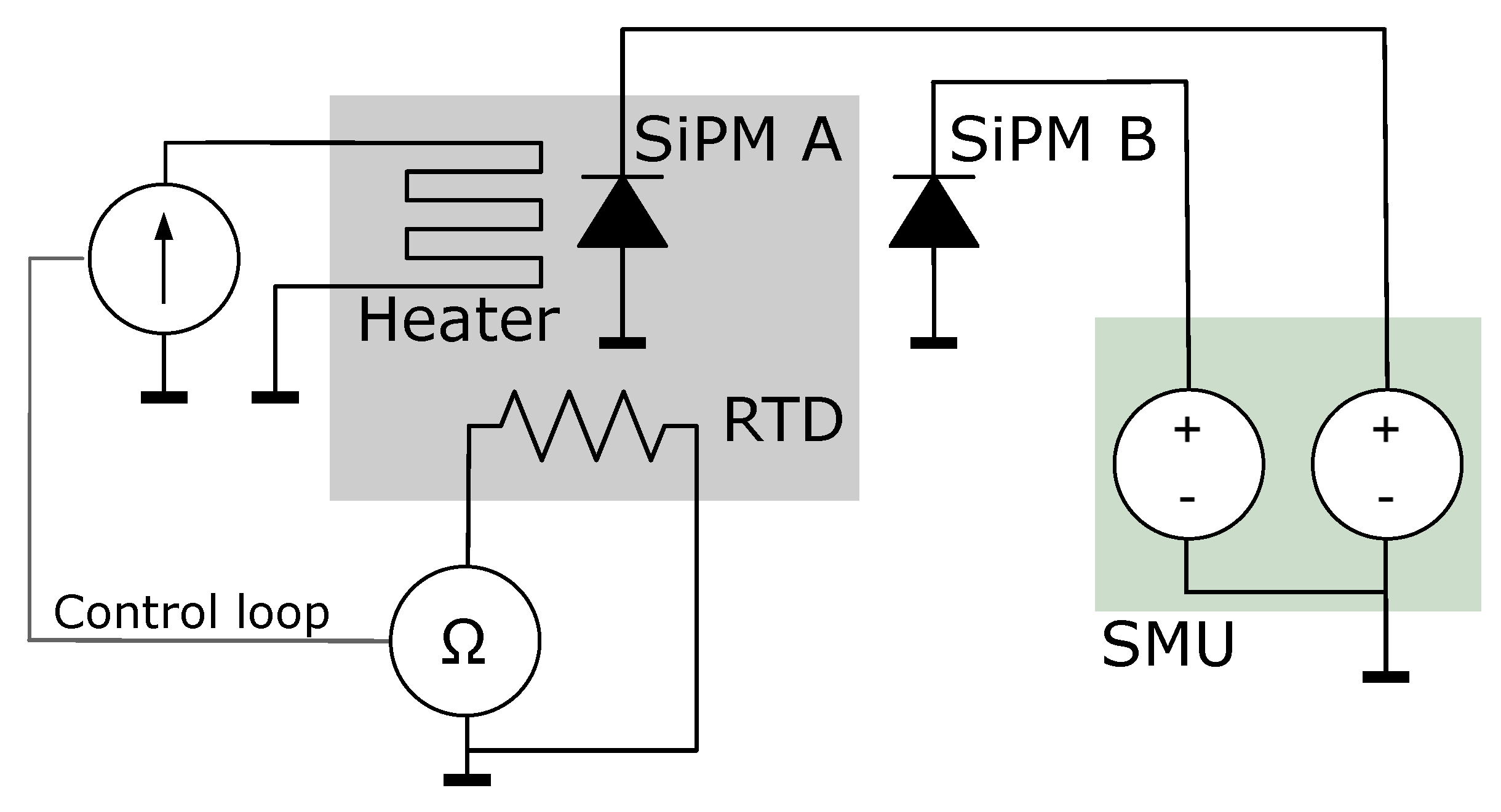

2.2. Set Up

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed thermal recovery technique, an experiment was designed in which two MICROFC-60035 SiPMs were irradiated together under controlled conditions. The area of the SiPM is 6x6 mm2 and its microcell width is 35 µm. The first sample (SiPM A) was coupled with the serpentine heater and underwent thermal annealing between irradiation cycles. The second sample (SiPM B) served as a control and was irradiated without any recovery process.

For this experiment, 9 MeV protons were selected based on TRIM (Transport of Ions in Matter) [

30] Monte Carlo simulations. This analysis showed that the proposed energy is sufficient to allow the protons to penetrate the SiPM structure and stop within the bulk silicon, depositing energy along their path. A total of eight irradiation cycles were performed, reaching an accumulated fluence of (1.89 ± 0.01)×10

8 cm

−2. The irradiation conditions were defined to replicate a representative radiation environment for LEO missions. According to in-orbit measurements from the LS-01 payload onboard ÑuSat-7, the accumulated 1 MeV neutron equivalent fluence received by the SiPMs and associated electronics was approximately

n/cm

2 over a 4-year mission duration [

18,

19].

For 9 MeV protons, the damage equivalence factor (

) in silicon is approximately 5 [

31,

32,

33], meaning that one 9 MeV proton induces roughly five times the displacement damage of a 1 MeV neutron. Based on this, the total proton fluence applied in our experiment,

p/cm

2, corresponds to a neutron-equivalent fluence of

n/cm

2. Using the average daily fluence reported in orbit (

n/cm

2/day [

19]), this is equivalent to approximately 278 days in LEO.

The TRIM simulation considered a multi-layer structure, consisting of: (i) a 72 µm Tantalum-Copper (Ta-Cu) sheet with respective thicknesses of 70 µm and 2 µm, designed to attenuate the incident proton flux; (ii) a silicon oxide layer, which forms the protective coating of the sensor; and (iii) the active detection region, primarily composed of silicon.

Both SiPMs were biased at 30 V using a Keithley 2612B two-channel Source-Measure Unit (SMU), which continuously monitored their dark current throughout the experiment. The SiPM A was integrated in the copper side of the heater, isolated with Kapton tape. Thermal grease was applied between the heater and the SiPM in order to improve the thermal conductivity.

Its temperature was measured using a Resistance Temperature Detector (RTD) and incorporated into the feedback control loop to maintain the heater at the target temperature of 100 °C. The experimental setup is shown in

Figure 4. The annealing temperature was selected to maximize thermal agitation while remaining within the manufacturer’s recommended thermal limits. Although the device was under reverse bias during annealing, the chosen setpoint of 100 °C avoids exceeding critical temperature ratings. Previous studies with Hamamatsu SiPMs reported improved dark current recovery at higher temperatures, such as 120 °C [

22], though such conditions surpass the specified limits for the devices used in this work. The heating duration was set to 5 minutes for the first six irradiation cycles and extended to 10 minutes in the seventh cycle. During each thermal annealing cycle, SiPM A remained reverse biased, with its current limited to 5 mA to prevent potential damage due to excessive current flow. Before initiating each new irradiation interval, the system was allowed to cool down until the SiPM temperature stabilized within the range of 27 °C to 30 °C.

2.3. Definitions

To quantify the effectiveness of thermal annealing, we define two metrics: the degradation factor and the recovery factor. The degradation (

D) represents the relative increase in dark current due to irradiation and is given by

where

and

are the dark currents measured before and after each irradiation interval, respectively. The recovery factor (

R) quantifies the dark current reduction due to annealing and is defined as

where

is the dark current measured after the annealing cycle.

3. Results

In this section, the main experimental results are presented, focusing on the effects of proton irradiation and thermal annealing on the performance of the SiPMs. The analysis includes the evolution of dark current, the influence of temperature, and variations in the breakdown voltage. Comparisons are made between the annealed and non-annealed samples, highlighting the impact of thermal recovery processes on radiation-induced degradation.

3.1. Dark Current

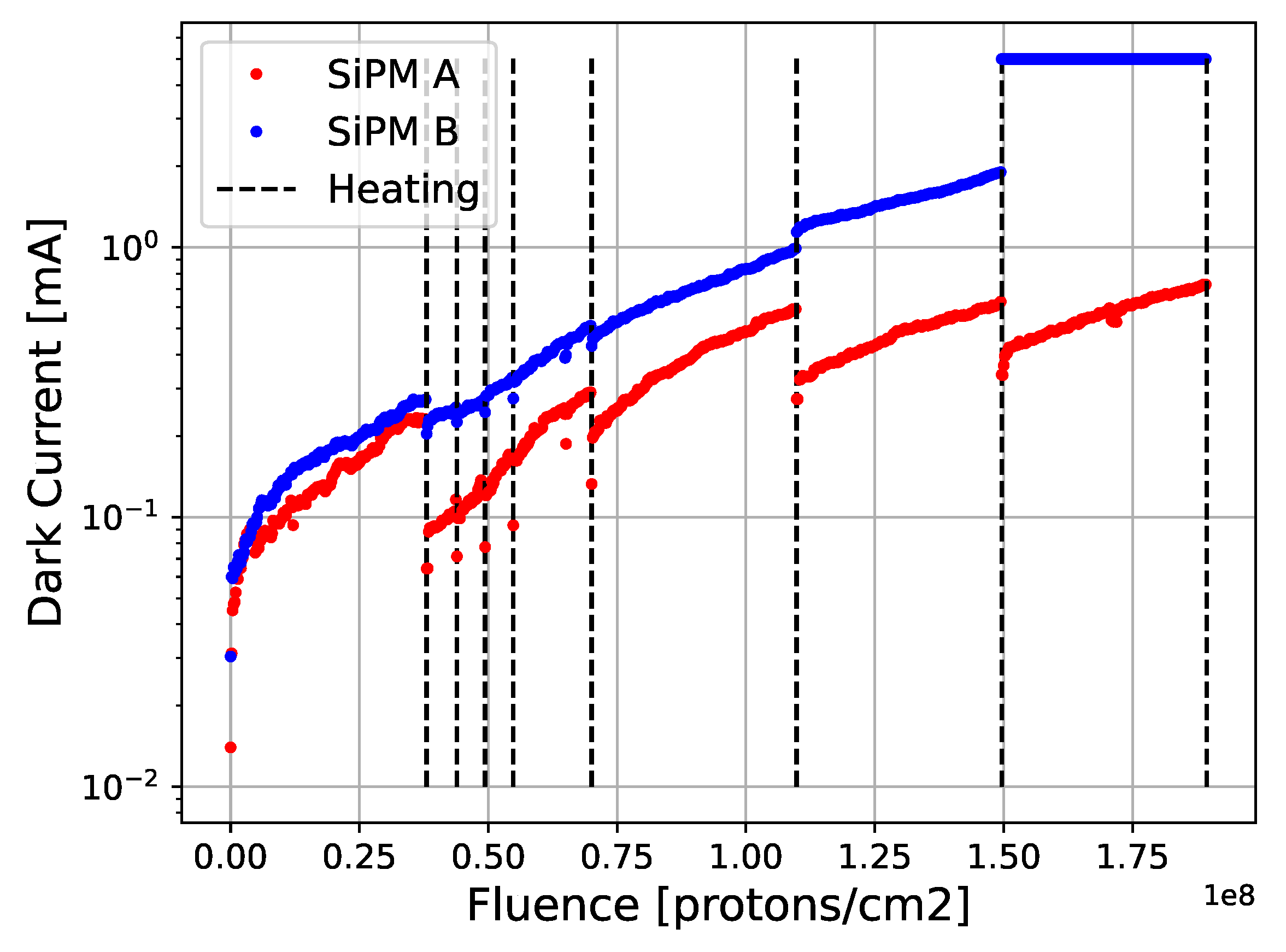

Performing real-time measurements and thermal annealing in situ inside the irradiation chamber enables the continuous tracking of the SiPM damage.

Figure 5 illustrates the irradiation process, with highlighted regions indicating the moments when thermal annealing was applied to SiPM A. A progressive reduction in dark current is observed in SiPM A following each thermal cycle, suggesting a partial recovery effect induced by temperature. The results obtained for the degradation (Equation (

1)) and recovery (Equation (

2)) metrics are summarized in

Table 1.

However, it is important to consider potential factors that may have influenced the behavior of SiPM B. For instance, thermal coupling between the two sensors could have resulted in partial heat transfer during the annealing cycles of SiPM A. This effect led to a temperature increase of less than 10 °C in SiPM B, which may have contributed to a slight recovery of its dark current.

A recovery efficiency of at least 39 % was achieved, regardless of the accumulated fluence, demonstrating the effectiveness of the thermal annealing process across multiple irradiation levels. The most significant radiation-induced degradation occurred during the first irradiation cycle, suggesting that applying the thermal annealing process at lower fluence intervals may enhance the overall recovery rate. The control sensor (SiPM B) exhibited a continuous increase in dark current, eventually reaching saturation. However, after being reset and subjected to a temperature increase, the sensor regained functionality, stabilizing at a dark current of 0.6 mA at 30 °C.

3.2. Current and Temperature

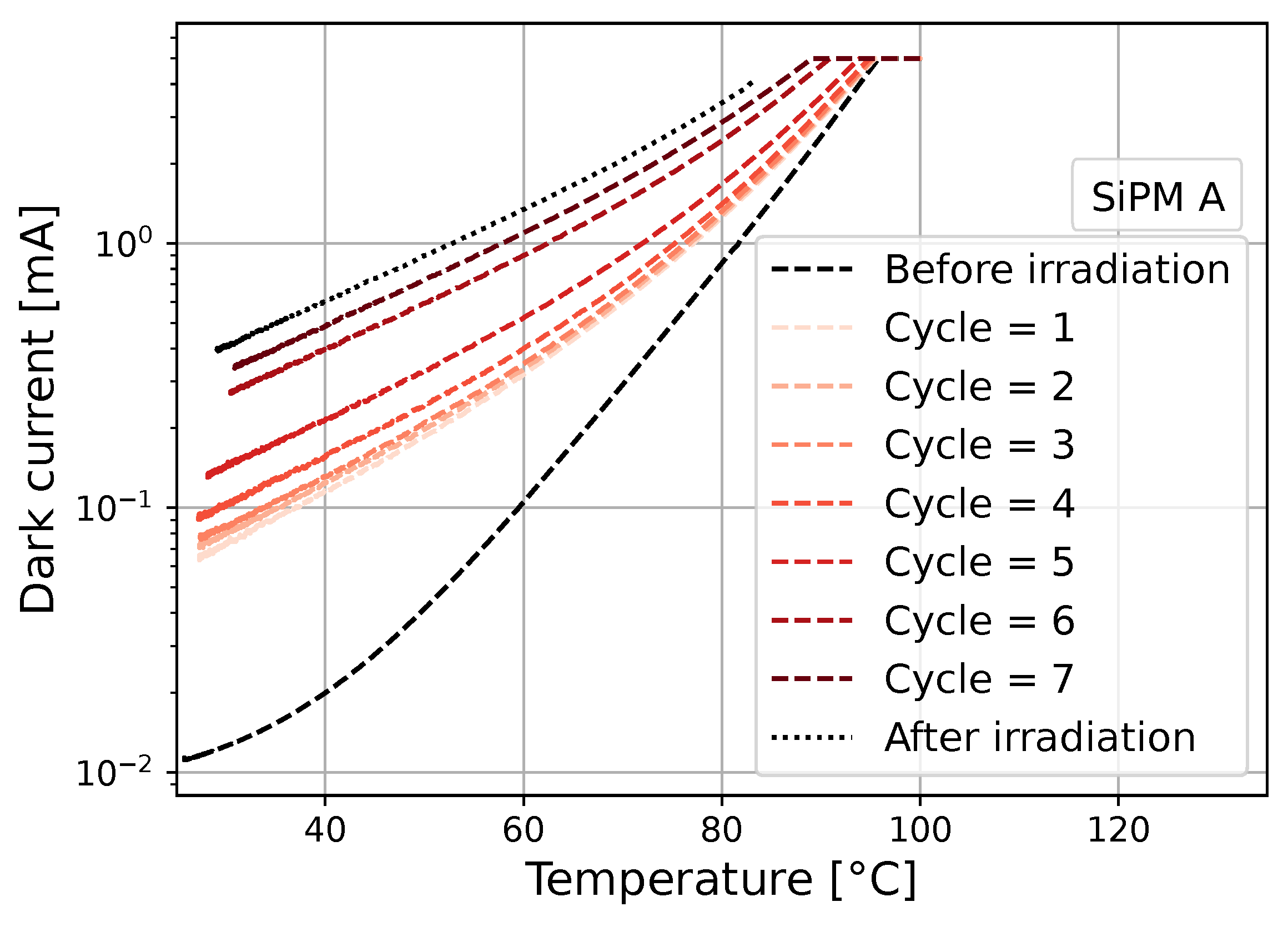

The behavior of SiPM A following each thermal annealing cycle was analyzed.

Figure 6 presents the dark current measurements for SiPM A at different temperatures, including values before irradiation, after each irradiation cycle, and one month post-irradiation. The fundamental operating behavior of the sensor remains unaffected by radiation exposure. While dark current increases due to radiation-induced degradation, the sensor continues responding as expected, exhibiting the characteristic increase in dark current with rising temperature. This indicates that the underlying physical mechanisms governing the sensor’s response remain intact, with radiation damage introducing only an offset in the baseline current rather than altering its intrinsic functionality.

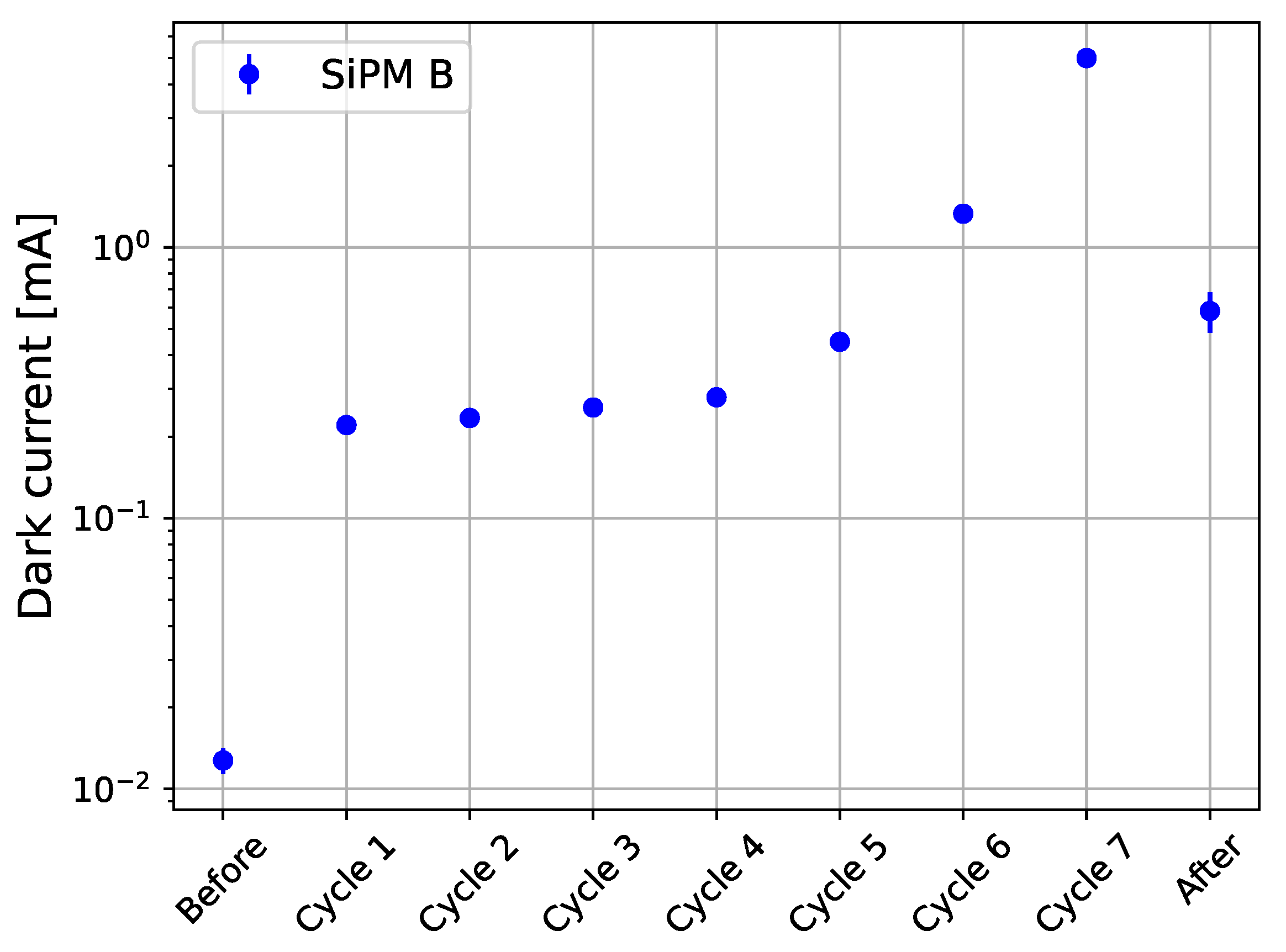

For the control sample (SiPM B), which did not undergo thermal annealing, the radiation-induced degradation is shown in

Figure 7. This device experienced a progressive increase in dark current, eventually reaching the compliance limit of 5 mA. After one month at room temperature, a partial recovery was observed.

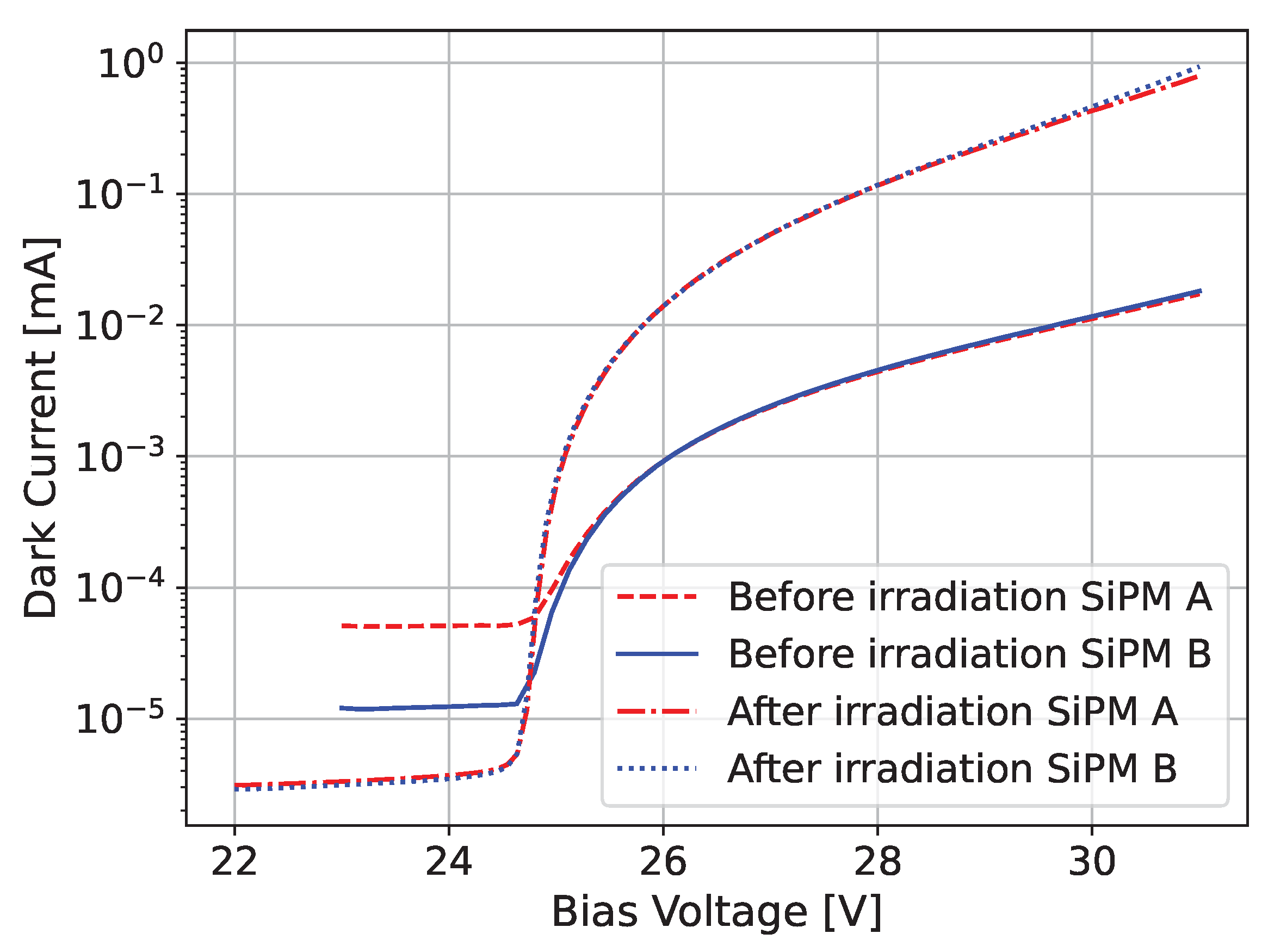

3.3. Breakdown Voltage

The breakdown voltage (V

B) was analyzed before and after irradiation to assess potential radiation-induced changes. This parameter was estimated by measuring the dark current as a function of bias voltage at room temperature (25–26 °C). The results are presented in

Figure 8. No significant differences were observed in V

B between pre- and post-irradiation conditions. Prior to irradiation, the breakdown voltage was measured as (24.63 ± 0.16) V for SiPM A and (24.47 ± 0.16) V for SiPM B. After irradiation, both sensors exhibited a breakdown voltage of (24.64 ± 0.09) V, indicating that irradiation did not significantly alter this parameter. The V

B was determined using the second derivative method applied to the dark current curve, following the approach described in [

34]. The post-irradiation measurement was performed one month after the experiment, during which both devices remained at room temperature.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of proton irradiation on SiPMs and explored thermal annealing as a potential recovery technique for space application. Two SiPMs were irradiated under controlled conditions, with one undergoing thermal cycling at 100 °C between irradiation intervals, while the other served as a control sample without any recovery process. The experiment was designed to simulate radiation damage in LEO and assess the feasibility of in-flight recovery strategies using a PCB-integrated heater.

For satellite applications, minimizing current consumption is critical due to strict power generation constraints and limited heat dissipation capabilities. Based on thermographic analysis and electrical measurements, the 75 µm-width serpentine geometry was selected for its superior heat distribution and lowest current requirement among the tested heater designs.

The results demonstrate that thermal annealing can significantly mitigate radiation-induced degradation. A dark current recovery of over 39 % was achieved with just 5 minutes of thermal cycling at 100 °C, highlighting the effectiveness of low-temperature annealing in restoring sensor performance. This is particularly promising for small satellite missions, as it suggests that in-orbit recovery of degraded SiPMs can be achieved with minimal energy and hardware complexity.

Importantly, despite the cumulative radiation damage, the temperature dependence of the SiPM’s dark current remained consistent with pre-irradiation behavior. As shown in

Figure 6, the thermal response maintains a similar trend across cycles, suggesting that the dominant generation mechanisms remain unaffected. This indicates that the sensor remains predictable and calibratable, a critical factor for ensuring long-term performance and reliability in thermally variable space environments.

Additionally, no significant variations were observed in the breakdown voltage before and after irradiation and thermal cycling, reinforcing that the core operating characteristics of the SiPMs were not compromised. These findings confirm that thermal annealing is a viable, low-complexity mitigation strategy to extend the operational lifetime of SiPM-based detectors in LEO.

In contrast to the in-situ current annealing approach proposed by Gu et al. [

24], our method decouples the heating mechanism from the sensor itself. By using an external PCB-integrated heater, we enable controlled thermal recovery without electrically stressing the SiPM, reducing the risk of damage. This design is more robust and better suited for small satellite platforms, where power budgets and device protection are key considerations. Recent findings on self-heating in irradiated SiPMs [

25] further emphasize the importance of controlled thermal management in orbit.

Future work will focus on optimizing the annealing profile, including temperature and duration, and validating this recovery approach across different SiPM architectures and radiation conditions. The insights gained in this study contribute to the development of resilient photodetection systems for next-generation space missions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.; methodology, A.L., L.F., and M.L.I.; software, M.M.; validation, A.L., L.F., and G.A.S.; formal analysis, A.L. and G.A.S.; investigation, A.L., L.F., L.G., G.A.S., and F.G.; resources, G.A.S. and F.G.; data curation, A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L. and G.A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.L., G.A.S., L.F., L.G., and F.G.; visualization, A.L.; supervision, G.A.S. and F.G.; project administration, G.A.S.; funding acquisition, F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANPCyT, PICT-2019-2019-02993 “LabOSat: desarrollo de un Instrumento detector de fotones individuales para aplicaciones espaciales” and UNSAM-ECyT FP-001.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the CNEA Solar Energy Department, and in particular Dr. Martin Alurralde for their assistance during irradiation at the TANDAR accelerator.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Acerbi, F.; Gundacker, S. Understanding and simulating SiPMs. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2019, 926, 16–35, Silicon Photomultipliers: Technology, Characterisation and Applications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, K.; Coupland, D.; Beckman, D.; Mesick, K. Proton irradiation damage and annealing effects in ON Semiconductor J-series silicon photomultipliers. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2020, 969, 163957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundacker, S.; Heering, A. The silicon photomultiplier: fundamentals and applications of a modern solid-state photon detector. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2020, 65, 17TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, A.; Garcia, D. A very brief review of recent SiPM developments. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of Science in International Conference on New Photo-detectors (PhotoDet2015), Mosca, Russia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Gao, H.; Wen, J.; Zeng, M.; Pan, X.; Xu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, H.; Jiang, Y.; et al. In-orbit radiation damage characterization of SiPMs in the GRID-02 CubeSat detector. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2022, 1044, 167510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmistrov, L. A Silicon-Photo-Multiplier-Based Camera for the Terzina Telescope on Board the Neutrinos and Seismic Electromagnetic Signals Space Mission. Instruments 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencardino, R.; Altaura, F.; Bidoli, V.; Bongiorno, L.; Casolino, M.; De Pascale, M.; Ricci, M.; Picozza, P.; Aisa, D.; Alvino, A.; et al. Response of the LAZIO-SiRad detector to low energy electrons. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th International Cosmic Ray Conference. August 3-10, 2005, Pune, India. Edited by B. Sripathi Acharya, Sunil Gupta, P. Jagadeesan, Atul Jain, S. Karthikeyan, Samuel Morris, and Suresh Tonwar. Mumbai: Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, 2005. Volume 2, p. 449, 2005, Vol. 2, p. 449.

- Chung, C.; Backes, T.; Dittmar, C.; Karpinski, W.; Kirn, T.; Louis, D.; Schwering, G.; Wlochal, M.; Schael, S. The Development of SiPM-Based Fast Time-of-Flight Detector for the AMS-100 Experiment in Space. Instruments 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisconti, F. Use of Silicon Photomultipliers in the Detectors of the JEM-EUSO Program. Instruments 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Xiong, S.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; An, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Peng, W.; Wang, H.; et al. Energy response of GECAM gamma-ray detector based on LaBr3:Ce and SiPM array. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2019, 921, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Ling, L.; Deng, Y.; Han, C.; Yu, L.; Cao, G.; Wang, Y. A novel visible light communication system based on a SiPM receiver. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Telecommunications and Communication Engineering: ICTCE 2020, 4-6 December, Singapore.

- Chesi, G.; Malinverno, L.; Allevi, A.; Santoro, R.; Caccia, M.; Martemiyanov, A.; Bondani, M. Optimizing Silicon photomultipliers for Quantum Optics. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, L.; Izraelevitch, F.; Luszczak, A.; Huber, T.; Haungs, A.; Golmar, F. Silicon photomultipliers for detection of photon bunching signatures. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2024, 1065, 169542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garutti, E.; Musienko, Y. Radiation damage of SiPMs. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2019, 926, 69–84, Silicon Photomultipliers: Technology, Characterisation and Applications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrisi, C.; Ruzzarin, M.S.; Acerbi, F.; Bissaldi, E.; Di Venere, L.; Gargano, F.; Giordano, F.; Gola, A.; Loporchio, S.; Merzi, S.; et al. Radiation Damage on SiPM for High Energy Physics Experiments in space missions. In Proceedings of the EPJ Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, 2025, Vol. 319. 12008.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, J.; Guo, D.; Dong, Y.; Gao, M.; Fan, R.; Tan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Collaboration, H.P.; et al. Radiation characterization of SiPMs for HERD PSD. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2025, 1070, 170035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanca, G.A.; Barella, M.; Gomez Marlasca, F.; Alvarez, N.; Levy, P.; Golmar, F. LabOSat-01: A Payload for In-Orbit Device Characterization. IEEE Embedded Systems Letters 2024, 16, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, L.; Sanca, G.A.; Izraelevitch, F.; Golmar, F. Dark Current Degradation in SiPMs Along Full Orbits in LEO. In Proceedings of the 2024 Argentine Conference on Electronics (CAE); 2024; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, L.; Izraelevitch, F.; Barella, M.; Gomez Marlasca, F.; Sanca, G.; Golmar, F. Characterization of SiPM performance in a small satellite in low earth orbit using LabOSat-01. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2024, 1067, 169711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, L.; Barella, M.; Gomez Marlasca, F.; Sambuco Salomone, L.; Carbonetto, S.; Cassani, M.V.; Redín, E.; García-Inza, M.; Sanca, G.; Golmar, F. Total ionizing dose measurements in small satellites in LEO using LabOSat-01. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2024, 1064, 169344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montillo, F.; Balk, P. High-Temperature Annealing of Oxidized Silicon Surfaces. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 1971, 118, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, T. Silicon photomultipliers radiation damage and recovery via high temperature annealing. Journal of Instrumentation 2018, 13, P10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirade, N.; Takahashi, H.; Uchida, N.; Ohno, M.; Torigoe, K.; Fukazawa, Y.; Mizuno, T.; Matake, H.; Hirose, K.; Hisadomi, S.; et al. Annealing of proton radiation damages in Si-PM at room temperature. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2021, 986, 164673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, D.; An, Z.; Gong, K.; Li, X.; Wen, X.; Xiong, S.; et al. Achieving significant performance recovery of SiPMs’ irradiation damage with in-situ current annealing. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2023, 1053, 168381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schade, L.; Oberlack, U.; Podiachev, S.; Schäfer, D.; Schiffer, S.; Zimmermann, S. Determination of Self-Heating in Silicon Photomultipliers. Sensors 2024, 24, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, M.; Garcia, J.; Dato, A.; Yaccuzzi, E.; Prario, I.; Filevich, A.; Barrera, M.; Alurralde, M. E.D.R.A. , the Argentine facility to simulate radiation damage in space. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2019, 154, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Du, X.; Li, Y.; Tai, H.; Su, Y. Optimization of temperature uniformity of a serpentine thin film heater by a two-dimensional approach. Microsystem Technologies 2019, 25, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVay, J.; Engheta, N.; Hoorfar, A. High impedance metamaterial surfaces using Hilbert-curve inclusions. IEEE Microwave and Wireless Components Letters 2004, 14, 130–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnati, K.S.C.; Nagireddy, S.R.; Mishra, R.B.; Hussain, A.M. Design of Micro-heaters Inspired by Space Filling Fractal Curves. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP); 2019; pp. 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.F.; Ziegler, M.; Biersack, J. SRIM – The stopping and range of ions in matter (2010). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2010, 268, 1818–1823, 19th International Conference on Ion Beam Analysis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.P.; Petersen, E.L. Comparison of Neutron, Proton and Gamma Ray Effects in Semiconductor Devices. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 1987, 34, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, G.P.; Burke, E.A.; Dale, C.J.; Wolicki, E.A.; Marshall, P.W.; Gehlhausen, M.A. Correlation of Particle-Induced Displacement Damage in Silicon. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 1987, 34, 1134–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, G.P.; Burke, E.A.; Shapiro, P.; Messenger, S.R.; Walters, R.J. Damage correlations in semiconductors exposed to gamma, electron and proton radiations. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 1993, 40, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, F.; Hegyesi, G.; Kalinka, G.; Molnár, J. A model based DC analysis of SiPM breakdown voltages. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2017, 849, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Irradiation chamber at the EDRA facility. The proton beam enters the chamber after passing through a 72 µm-thick Tantalum-Copper (Ta-Cu) attenuator, designed to regulate energy deposition and flux intensity. Electrical connections are introduced into the chamber via a DB25 feedthrough port. A remotely controlled concentric ring system at the chamber base allows for precise target positioning, enabling the selection between a solid-state detector and the SiPM-heater assembly for irradiation experiments under controlled conditions.

Figure 1.

Irradiation chamber at the EDRA facility. The proton beam enters the chamber after passing through a 72 µm-thick Tantalum-Copper (Ta-Cu) attenuator, designed to regulate energy deposition and flux intensity. Electrical connections are introduced into the chamber via a DB25 feedthrough port. A remotely controlled concentric ring system at the chamber base allows for precise target positioning, enabling the selection between a solid-state detector and the SiPM-heater assembly for irradiation experiments under controlled conditions.

Figure 2.

Heater geometries evaluated for SiPM thermal treatment. Each column represents a different heating track design: from left to right, a Hilbert curve with 150 µm trace width, a Hilbert curve with 75 µm trace width, and a serpentine pattern with 75 µm trace width. The top row shows the respective track layouts, the middle row presents thermographic images of the heaters in operation, and the bottom row displays thermographic images with the heaters covered by Kapton tape, illustrating heat distribution under insulation conditions.

Figure 2.

Heater geometries evaluated for SiPM thermal treatment. Each column represents a different heating track design: from left to right, a Hilbert curve with 150 µm trace width, a Hilbert curve with 75 µm trace width, and a serpentine pattern with 75 µm trace width. The top row shows the respective track layouts, the middle row presents thermographic images of the heaters in operation, and the bottom row displays thermographic images with the heaters covered by Kapton tape, illustrating heat distribution under insulation conditions.

Figure 3.

Power consumption (a) and current consumption (b) of the proposed heater geometries as a function of temperature. Among the evaluated designs, the serpentine heater exhibits the lowest current consumption to reach 100 °C, while the 150 µm Hilbert geometry shows the lowest power consumption at the same target temperature.

Figure 3.

Power consumption (a) and current consumption (b) of the proposed heater geometries as a function of temperature. Among the evaluated designs, the serpentine heater exhibits the lowest current consumption to reach 100 °C, while the 150 µm Hilbert geometry shows the lowest power consumption at the same target temperature.

Figure 4.

Schematic of the experimental setup. Two SiPMs were simultaneously irradiated inside the chamber. One SiPM was equipped with a heater integrated into the pads to facilitate the annealing process after each cycle. The SiPM’s temperature was monitored by measuring the resistance of an attached Resistance Temperature Detector (RTD). A current source, managed by a PID controller, powered the heater to stabilize the temperature at 100 °C during annealing. Both SiPMs were biased using a Source Measure Unit (SMU), which also recorded the resulting currents.

Figure 4.

Schematic of the experimental setup. Two SiPMs were simultaneously irradiated inside the chamber. One SiPM was equipped with a heater integrated into the pads to facilitate the annealing process after each cycle. The SiPM’s temperature was monitored by measuring the resistance of an attached Resistance Temperature Detector (RTD). A current source, managed by a PID controller, powered the heater to stabilize the temperature at 100 °C during annealing. Both SiPMs were biased using a Source Measure Unit (SMU), which also recorded the resulting currents.

Figure 5.

Accumulated fluence during the irradiation process for SiPM A and SiPM B. The vertical dotted lines indicate the thermal cycling periods applied to SiPM A, while SiPM B remained as a control without thermal treatment. A progressive reduction in dark current is observed in SiPM A following each thermal annealing cycle, suggesting a partial recovery effect induced by temperature.

Figure 5.

Accumulated fluence during the irradiation process for SiPM A and SiPM B. The vertical dotted lines indicate the thermal cycling periods applied to SiPM A, while SiPM B remained as a control without thermal treatment. A progressive reduction in dark current is observed in SiPM A following each thermal annealing cycle, suggesting a partial recovery effect induced by temperature.

Figure 6.

Dark current as a function of temperature measured at three stages: prior to irradiation, after each irradiation cycle, and one month post-irradiation. The current was limited to 5 mA.

Figure 6.

Dark current as a function of temperature measured at three stages: prior to irradiation, after each irradiation cycle, and one month post-irradiation. The current was limited to 5 mA.

Figure 7.

Dark current before irradiation, after irradiation cycles and after one month post-irradiation for SiPM B. The current was limited to 5 mA.

Figure 7.

Dark current before irradiation, after irradiation cycles and after one month post-irradiation for SiPM B. The current was limited to 5 mA.

Figure 8.

Dark current for differents bias voltages. Before the irradiation and after one month of the irradiation. This curve shows the breakdown voltage of the sensor.

Figure 8.

Dark current for differents bias voltages. Before the irradiation and after one month of the irradiation. This curve shows the breakdown voltage of the sensor.

Table 1.

SiPM A degradation and recovery results for each irradiation and annealing intervals.

Table 1.

SiPM A degradation and recovery results for each irradiation and annealing intervals.

| Irradiation interval |

D [%] |

R [%] |

| 1 |

1539 |

72 |

| 2 |

81 |

39 |

| 3 |

84 |

41 |

| 4 |

123 |

46 |

| 5 |

214 |

55 |

| 6 |

342 |

53 |

| 7 |

129 |

46 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).