Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

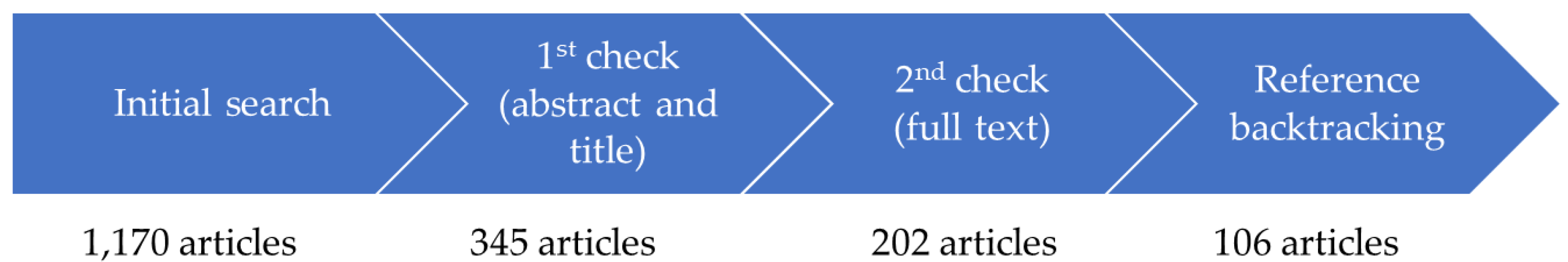

2. Method

3. SMEs and Ambidexterity

4. Ambidexterity and Open Innovation

5. Ambidexterity, Green Innovation, and Sustainability

| Country | Subject | N | Direction | Method | Summary | Dependent variable | Independent variable | Mediator | # |

| Portugal | SMEs | 336 | Cross-sectional | Structural equation modeling | Ambidexterity positively influences sustainability, which in turn positively influences new product success and green product innovation. | Green product innovation | Ambidexterity | Sustainability | [63] |

| China | Knowledge-intensive SMEs in Nanjing | 289 | Cross-sectional | Linear regression | Digital innovation mediates the relationship between ambidextrous learning and sustainable competitive ad-vantage. | Sustainable competitive advantage | Ambidextrous learning | Digital innovation | [64] |

| India | Manufacturing facilities with 100+ employees | 1,471 | Cross-sectional | Structural equation modeling | The exposure of manufacturing firms to exploitative/exploratory innovative capabilities induces sustainable behaviors with temporal and enduring focus. | Sustainable behavior | Stakeholder pressure | Ambidexterity | [15] |

6. Ambidexterity and Digitalization

6.1. Knowledge Absorption Under Cost Constraints

6.2. Responding to Radical Innovation

6.3. Risk Reduction

6.4. Empirical Research

7. Digitalization, Green Innovation, and Sustainability

8. Digitalization and Human Resources

8.1. Digitalization and Skilled Labor Force

8.2. Financial Constraints and Management Expertise

9. Green Innovation, Sustainability, and Open Innovation

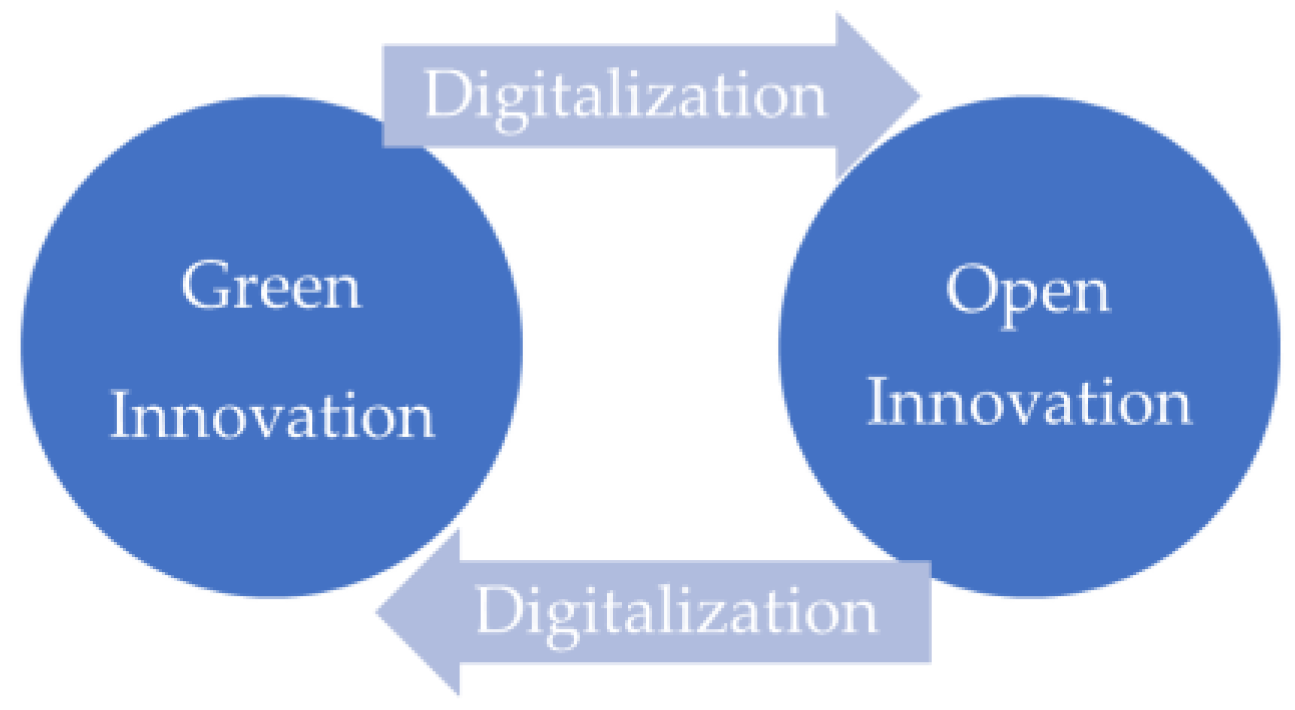

10. Combination Effects

10.1. Digitalization, Open Innovation, Green Innovation, and Performance

10.2. Digitalization, Ambidexterity, and Performance

10.3. Research Achievements and Challenges

11. Discussion

11.1. When Should Digitalization Be Adopted?

11.2. Theoretical Implications

11.3. Practical and Policy Implications

12. Limitations and Future Research Directions

13. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For example, in Japan, large and small enterprises form a keiretsu system, and SMEs have been required to engage in process innovation and incremental innovation to quickly and accurately supply products and parts with the specifications required by large enterprises within the existing supply chain [37]. In such an environment, exploitation by utilizing existing information networks has a greater impact on corporate performance than exploration, which requires new information networks. This keiretsu system is unique to Japan in that it involves cross-shareholding, which promotes trust building and mutual information sharing between companies, reduces transaction costs (e.g., monitoring costs), and acts as a deterrent to betrayal [38]. It is thought that sourcing information from outside the keiretsu and exploring through open innovation and digitalization was costly and not very profitable for SMEs. |

References

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L.; O’Reilly, C.A. The ambidextrous organization: managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boronat-Navarro, M.; Escribá-Esteve, A.; Navarro-Campos, J. Ambidexterity in micro and small firms: Can competitive intelligence compensate for size constraints? BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2024, 27, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.H.; Douglas, E.J. Resource reconfiguration by surviving SMEs in a disrupted industry. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2024, 62, 140–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Ha, S.; Kim, Y. Innovation ambidexterity, resource configuration and firm growth: is smallness a liability or an asset? Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 2183–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. How do Chinese SMEs enhance technological innovation capability? From the perspective of innovation ecosystem. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 1235–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Rienda, L.; Andreu, R. The international entrepreneurial intention of SMEs towards China: A network approach. J. Int. Entrep. 2025, printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Ko, W.W. The influence of marketing exploitation and exploration on business-to-business small and medium-sized enterprises’ pioneering orientation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 117, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, T.; Kraus, S.; Kallinger, F.L.; Bican, P.M.; Brem, A.; Kailer, N. Organizational ambidexterity and competitive advantage: The role of strategic agility in the exploration-exploitation paradox. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenke, K.; Zapkau, F.B.; Schwens, C. Too small to do it all? A meta-analysis on the relative relationships of exploration, exploitation, and ambidexterity with SME performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, M.; Krauss, G. The Baden-Württemberg production and innovation regime: past successes and new challenges. In Regional innovation systems (pp. 186–213). Routledge, 2024.

- Yli-Renko, H.; Denoo, L.; Janakiraman, R. A knowledge-based view of managing dependence on a key customer: Survival and growth outcomes for young firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 106045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corchuelo Martínez-Azúa, B.; Dias, A.; Sama-Berrocal, C. Exploring the importance of innovation ambidexterity on performance: insights from NCA and IPMA analysis. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2024, printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, S.K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Rathore, H.; Mangla, S.K. Stakeholder pressure for sustainability: Can ‘innovative capabilities’ explain the idiosyncratic response in the manufacturing firms? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 2635–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Buijs, P. Strategic ambidexterity in green product innovation: Obstacles and implications. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2022, 31, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Wu, J.; Wu, T.; Chang, P.C.; Mardani, A. The impact of digital leadership on hidden champions’ competitive advantage: A moderated mediation model of ambidextrous innovation and value co-creation. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 182, 114819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lu, H.; Du, M. Coordinated development of digital economy and ecological resilience in China: Spatial–temporal evolution and convergence. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Cui, A.P.; Samiee, S.; Zou, S. Exploration, exploitation, ambidexterity and the performance of international SMEs. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 1372–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reischl, A.; Weber, S.; Fischer, S.; Lang-Koetz, C. Contextual ambidexterity: Tackling the exploitation and exploration dilemma of innovation management in SMEs. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2022, 19, 2250006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiyevskyy, O.; Shirokova, G.; Ritala, P. Exploration and exploitation in crisis environment: Implications for level and variability of firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, S.; Maccario, G.; De Nisco, A. Green innovation: a multidomain systematic review. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europian Commission. SME Definition - user guide 2020. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa. ,: (accessed, 13 July 4292.

- Almeida, F. Causes of failure of open innovation practices in small-and medium-sized enterprises. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilav–Velic, A.; Jahic, H.; Krndzija, L. Firm resilience as a moderating force for SMEs’ innovation performance: Evidence from an emerging economy perspective. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2024, 16, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusek, M. Exploitation, exploration, or ambidextrousness—An analysis of the necessary conditions for the success of digital servitisation. Sustainability 2022, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumkale, İ. Organizational Ambidexterity. In: Organizational Mastery. Accounting, Finance, Sustainability, Governance & Fraud: Theory and Application. Springer, Singapore, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, L.; Lessanibahri, S.; Tedaldi, G.; Miragliotta, G. Companies’ adoption of Smart Technologies to achieve structural ambidexterity: an analysis with SEM. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, I.; Kalyar, M.N.; Shafique, M.; Kianto, A.; Beh, L.S. Demystifying the link between knowledge management capability and innovation ambidexterity: organizational structure as a moderator. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2022, 28, 1343–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.; Kanbach, D.K. Toward an integrated framework of corporate venturing for organizational ambidexterity as a dynamic capability. Manag. Rev. Q. 2022, 72, 1129–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammad, M.F.; Basu, S.; Munjal, S.; Clegg, J.; Shoham, O.B. Strategic agility, environmental uncertainties and international performance: The perspective of Indian firms. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennerts, S.; Schulze, A.; Tomczak, T. The asymmetric effects of exploitation and exploration on radical and incremental innovation performance: an uneven affair, Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, F.; Jia, F.; Chen, L. (2023). Building supply chain resilience through ambidexterity: an information processing perspective. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 26, 172-189. [CrossRef]

- Iborra, M.; Safón, V.; Dolz, C. What explains the resilience of SMEs? Ambidexterity capability and strategic consistency. Long Range Plan. 2020, 53, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small and Medium Enterprise Agency, Summary of the interim report of the Expert Review Committee on the State of Innovation in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, Expert Review Committee on the State of Innovation in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, Small and Medium Enterprise Agency, Tokyo, 2023, available at: https://www.chusho.meti.go.jp/koukai/kenkyukai/index.html (accessed ). 1 February.

- Okamoto, N. Financialisation in the context of cross-shareholding in Japan: The performative pursuit of better corporate governance. J. Manag. Gov. 2024, 28, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettiol, M.; Capestro, M.; Di Maria, E.; Micelli, S. Ambidextrous strategies in turbulent times: the experience of manufacturing SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2023, 53, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Peng, M.Y.P.; Shao, L.; Yen, H.Y.; Lin, K.H.; Anser, M.K. Ambidexterity in social capital, dynamic capability, and SMEs’ performance: quadratic effect of dynamic capability and moderating role of market orientation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 584969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. The era of open innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review 2003, 44, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Macher, G.; Veledar, O. Balancing exploration and exploitation through open innovation in the automotive domain – Focus on SMEs. In: Yilmaz, M., Clarke, P., Messnarz, R., Reiner, M. (eds) Systems, Software and Services Process Improvement. EuroSPI 2021. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1442. Springer, Cham, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Douglas, E. Small firm survival and growth strategies in a disrupted declining industry. J. Small Bus. Strategy. 2021, 31, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliasghar, O.; Sadeghi, A.; Rose, E.L. Process innovation in small-and medium-sized enterprises: The critical roles of external knowledge sourcing and absorptive capacity. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 1583–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddoud, M.Y.; Kock, N.; Onjewu, A.K.E.; Jafari-Sadeghi, V.; Jones, P. Technology, innovation and SMEs’ export intensity: Evidence from Morocco. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2023, 191, 122475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, B.; Menne, F.; Sabhan, H.; Suriani, S.; Abubakar, H.; Idris, M. Economic growth, increasing productivity of SMEs, and open innovation. J. Open Innov.: Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Crupi, A.; De Marco, C.E.; Di Minin, A. SMEs and open innovation: Challenges and costs of engagement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 122731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. The role of R&D and knowledge spillovers in innovation and productivity. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 123, 103391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M.; Caiazza, R. Start-ups, innovation and knowledge spillovers. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 1995–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumanti, A.A.; Rizana, A.F.; Septiningrum, L.; Reynaldo, R.; Isnaini, M.M.R. Innovation capability and open innovation for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) performance: Response in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Carvajal, O.; García-Pérez-de-Lema, D.; Castillo-Vergara, M. Impact of innovation strategy, absorptive capacity, and open innovation on SME performance: A Chilean case study. J. Open Innov.: Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phonthanukitithaworn, C.; Srisathan, W.A.; Ketkaew, C.; Naruetharadhol, P. Sustainable development towards openness SME innovation: taking advantage of intellectual capital, sustainable initiatives, and open innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nuaimi, F.M.S.; Singh, S.K.; Ahmad, S.Z. Open innovation in SMEs: a dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 484–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, S.; Vanhaverbeke, W. Knowledge risk management during implementation of open innovation. In: Durst, S., Henschel, T. (eds) Knowledge risk management. Management for professionals. Springer, Cham, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, M.; Garkisch, M.; Zeyen, A. Together we are strong? A systematic literature review on how SMEs use relation-based collaboration to operate in rural areas. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2023, 35, 515–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, L.; van Twuijver, M.; O’Shaughnessy, M. Rurality as context for innovative responses to social challenges–the role of rural social enterprises. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 99, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, P.; Stokes, P.; Tarba, S.Y.; Rodgers, P.; Dekel-Dachs, O.; Britzelmaier, B.; Moore, N. The ambidextrous interaction of RBV-KBV and regional social capital and their impact on SME management. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisathan, W.A.; Ketkaew, C.; Naruetharadhol, P. Assessing the effectiveness of open innovation implementation strategies in the promotion of ambidextrous innovation in Thai small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Dogbe, C. S.K.; Pomegbe, W.W.K.; Sarsah, S.A.; Otoo, C.O.A. Organizational learning ambidexterity and openness, as determinants of SMEs’ innovation performance. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 414–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. , Stefan, I., Yang, J. What Could Possibly Go Wrong? Reflections on Potential Challenges of Open Innovation. In: Rehn, A., Örtenblad, A. (eds) Debating innovation. Palgrave debates in business and management. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Latifi, M.A.; Nikou, S.; Bouwman, H. Business model innovation and firm performance: Exploring causal mechanisms in SMEs. Technovation 2021, 107, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, C.E.; Martelli, I.; Di Minin, A. European SMEs’ engagement in open innovation When the important thing is to win and not just to participate, what should innovation policy do? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 152, 119843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancela, B.L.; Coelho, A.; Duarte Neves, M.E. Greening the business: How ambidextrous companies succeed in green innovation through to sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3073–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Montera, R.; Cucari, N.; Polese, F. How an international ambidexterity strategy can address the paradox perspective on corporate sustainability: Evidence from Chinese emerging market multinationals. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2110–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ye, F.; Zhan, Y.; Kumar, A.; Schiavone, F.; Li, Y. Unraveling the performance puzzle of digitalization: Evidence from manufacturing firms. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Sun, L.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Qi, P. How do digitalization capabilities enable open innovation in manufacturing enterprises? A multiple case study based on resource integration perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 122019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xi, X.; Li, B.; Wang, T.; Yin, H. Research on radical innovation implementation through knowledge reuse based on knowledge flow: A case study on academic teams. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Matching external search strategies with radical and incremental innovation and the role of knowledge integration capability. Balt. J. Manag. 2021, 16, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Meadows, M.; Angwin, D.; Gomes, E.; Child, J. Strategic alliance research in the era of digital transformation: Perspectives on future research. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 589–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefner, N.; Wincent, J.; Parida, V.; Gassmann, O. Artificial intelligence and innovation management: A review, framework, and research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 162, 120392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgram, V.; Laarmann, F. Accelerating innovation with generative AI: AI-augmented digital prototyping and innovation methods. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2023, 51, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovuakporie, O.D.; Pillai, K.G.; Wang, C.; Wei, Y. Differential moderating effects of strategic and operational reconfiguration on the relationship between open innovation practices and innovation performance. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siregar, O.M.; Marpaung, N.; Nasution, M.D.T.P.; Harahap, R. A Literature Review on Incremental Innovations in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Bridging Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Avenues. In: Alareeni, B., Hamdan, A. (eds) Technology: Toward Business Sustainability. ICBT 2023. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 927. Springer, Cham, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Monge, E.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. The role of digitalization in business and management: a systematic literature review. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 449–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wael AL-khatib, A. Drivers of generative artificial intelligence to fostering exploitative and exploratory innovation: A TOE framework. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiao, Z. Examining the interaction effect of digitalization and highly educated employees on ambidextrous innovation in Chinese publicly listed SMEs: A knowledge-based view. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengel, F-M.; Kindermann, B.; Strese, S. The dual imperative of digital transformers – The relationship between a firm’s digital orientation and innovation ambidexterity. ECIS 2022 Research Papers, ,: Retrieved from: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2022_rp/95 (Accessed, 13 July 2022.

- Joensuu-Salo, S.; Viljamaa, A. The relationship between digital orientation, organizational ambidexterity, and growth strategies of rural SMEs in time of crisis. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2024, 25, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ürü, F.O.; Gözükara, E.; Ünsal, A.A. Organizational ambidexterity, digital transformation, and strategic agility for gaining competitive advantage in SMEs. Sosyal Mucit Academic Review 2024, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, P.M.; Ferreira, J.J.; Zhang, J.Z.; Liu, Y. Exploring the connections: ambidexterity, digital capabilities, resilience, and behavioral innovation. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, H.; Ram, R.; Hussainey, K.; Nandy, M.; Lodh, S. Exploration of small and medium entities’ actions on sustainability practices and their implications for a greener economy. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2023, 24, 655–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olekanma, O.; Rodrigo, L.S.; Adu, D.A.; Gahir, B. Small-and medium-sized enterprises’ carbon footprint reduction initiatives as a catalyst for green jobs: A systematic review and comprehensive business strategy agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 6911–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwandani, J.A.; Michaud, G. What are the drivers and barriers for green business practice adoption for SMEs? Environ. Syst. Decis. 2021, 41, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashar, A. Eco-efficient production for industrial small and medium-sized enterprises through energy optimisation: framework and evaluation. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 32, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy-Camacho, W.; Thornhill, I. Opportunities and limitations to environmental management system (EMS) implementation in UK small and medium enterprises (SMEs)–A systematic review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 121749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Could environmental regulation and R&D tax incentives affect green product innovation? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqmala, D.; Putra, F.I.F.S.; Eco Cuty. The eco-friendly marketing strategy model for MSME’s economic recovery movement post-covid 19. Calitatea 2023, 24, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kurdve, M.; Johansson, B.; Despeisse, M. Enabling the twin transitions: digital technologies support environmental sustainability through lean principles. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Subramanian, N.; Dora, M. Circular economy and digital capabilities of SMEs for providing value to customers: Combined resource-based view and ambidexterity perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Singh, S.; Gupta, H. Green entrepreneurship and digitalization enabling the circular economy through sustainable waste management-An exploratory study of emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, E. Digital Transformation in SMEs: Enablers, Interconnections, and a Framework for Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.L.; Pinto, S.S.; Costa, L.; Araújo, N. Evaluating digital transformation in small and medium enterprises using the Alkire-Foster method. Heliyon 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G.; Kim, K. Impacts of startup founders’ personal and business networks on fundraising success by mediating fundraising opportunities: Moderating role of firm age. J. Open Innov.: Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandukuri, V. Aligning talent and business: A key for sustainable HRM in SMEs. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 9, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, Z.; Khan, M.A.; Yang, Z.; Khan, A.; Haseeb, M.; Sarwar, A. An investigation of entrepreneurial SMEs’ network capability and social capital to accomplish innovativeness: A dynamic capability perspective. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211036089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmala, A.R.; Sukoco, B.M.; Ekowati, D.; Nadia, F.N.D.; Marjan, Y.; Hasanah, U. Strategies to overcome challenges and seize opportunities for born global SMEs: A systematic literature review. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241302869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Santa-Maria, T.; Kirchherr, J.; Pelzeter, C. Drivers and barriers for circular business model innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3814–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Gold, S.; Bocken, N.M. A review and typology of circular economy business model patterns. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Wankhede, V.A.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Nexus of circular economy and sustainable business performance in the era of digitalization. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2022, 71, 748–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratchandra, M.; Shrestha, A. Is Knowledge Ambidexterity the Answer to Economic Sustainability for SMEs? Lessons Learned from Digitalisation Efforts During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In: Adapa, S., McKeown, T., Lazaris, M., Jurado, T. (eds) Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, and Business Uncertainty. Palgrave Studies in Global Entrepreneurship. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore, 2023. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L. Senior management’s academic experience and corporate green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2021, 166, 120664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherringham, K.; Unhelkar, B. (2020). Knowledge Workers and Rapid Changes in Technology. In: Crafting and Shaping Knowledge Worker Services in the Information Economy. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Hock-Doepgen, M.; Clauss, T.; Kraus, S.; Cheng, C.F. Knowledge management capabilities and organizational risk-taking for business model innovation in SMEs. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivijärvi, H. Knowledge as a capability to make decisions: Experiences with a virtual support context. Knowl. Process Manag. 2024, 31, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastelli, I.; Dimas, P.; Stamopoulos, D.; Tsakanikas, A. Linking digital capacity to innovation performance: The mediating role of absorptive capacity. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 238–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Tang, Y.; Li, J. How digital transformation enhances corporate innovation performance: The mediating roles of big data capabilities and organizational agility. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, C.; Kraemer-Mbula, E.; Lorenz, E. The effects of digital transformation on innovation and productivity: Firm-level evidence of South African manufacturing micro and small enterprises. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 182, 121785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.H. How artificial intelligence technology affects productivity and employment: firm-level evidence from Taiwan. Research Policy 2022, 51, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergelova, A.; Manolova, T.; Simeonova-Ganeva, R.; Yordanova, D. Democratizing entrepreneurship? Digital technologies and the internationalization of female-led SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 14–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiari, S.; Breunig, R.; Magnani, L.; Zhang, J. Financial constraints and small and medium enterprises: A review. Econ. Rec. 2020, 96, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proeger, T.; Runst, P. Digitization and knowledge spillover effectiveness—Evidence from the “German Mittelstand”. J. Knowl. Econ. 2020, 11, 1509–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.; Kennedy, R.W.; Mashatan, A.; Rese, A.; Karavidas, D. High interest, low adoption. A mixed-method investigation into the factors influencing organisational adoption of blockchain technology. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garad, A.; Riyadh, H.A.; Al-Ansi, A.M.; Beshr, B.A.H. Unlocking financial innovation through strategic investments in information management: a systematic review. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Luo, S.; Miller, D.; Lin, H.C. Top management team means-ends diversity and competitive dynamics. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2025, 126, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, Y. The impact of suppliers’ CSR controversies on buyers’ market value: The moderating role of social capital. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2024, 30, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarango-Lalangui, P.; Castillo-Vergara, M.; Carrasco-Carvajal, O.; Durendez, A. Impact of environmental sustainability on open innovation in SMEs: An empirical study considering the moderating effect of gender. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumanti, A.A.; Rizaldi, A.S.; Amelia, M. Green Innovation toward Knowledge Sharing and Open Innovation in Indonesian SMIs. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM) (pp. 147–151). IEEE, 2024, December. [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Juárez, L.E.; Castillo-Vergara, M. Technological capabilities, open innovation, and eco-innovation: Dynamic capabilities to increase corporate performance of SMEs. J. Open Innov.: Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.; Shuqqo, H.; Qtaishat, L.; Asmar, H.; Salah, B. Sustainable competitive advantage driven by big data analytics and innovation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarik, M.S.; Naghavi, N.; Mubarik, M.; Kusi-Sarpong, S; , Khan, S. A.; Zaman, S.I.; Kazmi, S.H. Resilience and cleaner production in industry 4.0: role of supply chain mapping and visibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.M.; Buliga, O.; Voigt, K.I. The role of absorptive capacity and innovation strategy in the design of industry 4.0 business Models-A comparison between SMEs and large enterprises. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, S.; De Nisco, A. From Industry 4.0 adoption to innovation ambidexterity to firm performance: A MASEM analysis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.E. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 1988.

- Meier, A.; Eller, R.; Peters, M. Creating competitiveness in incumbent small-and medium-sized enterprises: A revised perspective on digital transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 186, 115028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishrif, A.; Khan, A. Technology adoption as survival strategy for small and medium enterprises during COVID-19. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Sánchez, D.T.; Talero-Sarmiento, L.H. Digital transformation in small and medium enterprises: a scientometric analysis. Digital Transformation Soci. 2024, 3, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Mikhaylov, A.; Chelaru, M.; Czakon, W. Adoption and performance outcome of digitalization in small and medium-sized enterprises. Rev Manag Sci 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokyo Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Survey on the Actual State of Energy Conservation and Decarbonization in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, /: Chamber of Commerce and Industry, 2024. available at: https, 1 February 2024.

- Ragazou, K.; Passas, I.; Garefalakis, A.; Dimou, I. Investigating the research trends on strategic ambidexterity, agility, and open innovation in SMEs: Perceptions from bibliometric analysis. J. Open Innov.: Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Subject | N | Direction | Method | Summary | Dependent variable | Independent variable | Effect size(ΔR2) | # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Medium-sized companies in the engineering industry | 150 | Cross-sectional | Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) | To survive and gain competitive advantage, companies must prioritize exploration over exploitation to create radically new knowledge, products, and services. | Competitive advantage | Exploration orientation | 0.350 | [9] |

| United Kingdom | Young B2B technology company | 180 | Longitudinal | Multinomial logistic regression model | Dependence on key customers has a significant negative impact on a company’s survival. | Corporate survival | Exploitation (dependence on a key customer) | 0.040 | [13] |

| Spain | Agribusiness SMEs | 150 | Cross-sectional | Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) | Innovation ambidexterity affects business performance, with exploratory innovation having a stronger impact on market and financial performance than exploitative innovation. | Financial/market performance | Exploration | 0.425 | [14] |

| Country | Subject | N | Direction | Method | Summary | Dependent variable | Independent variable | Mediator | # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | SMEs all industries | 1,474 | Cross-sectional | Hierarchical ordinary least square regression analysis. | Digital orientation facilitate innovation ambidexterity | Innovation ambidexterity | Digital orientation | n.a. | [77] |

| Finland | SMEs in rural areas of Southern Ostrobothnia | 204 | Cross-sectional | Ordinal regression analysis | Organizational ambidexterity mediates the relationship between digital orientation and growth strategies. | Growth strategies | Digital orientation | Organizational ambidexterity | [78] |

| Turkey | SMEs in Wholesale and Retail Trade Sector within the Boundaries of Istanbul Province | 366 | Cross-sectional | Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) | Digital transformation partially mediates the relationship between ambidexterity and competitive advantage in SMEs | Competitive Advantage | Organizational Ambidexterity | Digital Transformation | [79] |

| Multi Country | World Bank Business Survey (Tracking 21 countries) | 8,928 | Longitudinal | Partial least squares structural equation modeling | Organizational ambidexterity indirectly affects innovation through digital capabilities | Innovation | Organizational ambidexterity | Digital capabilities | [80] |

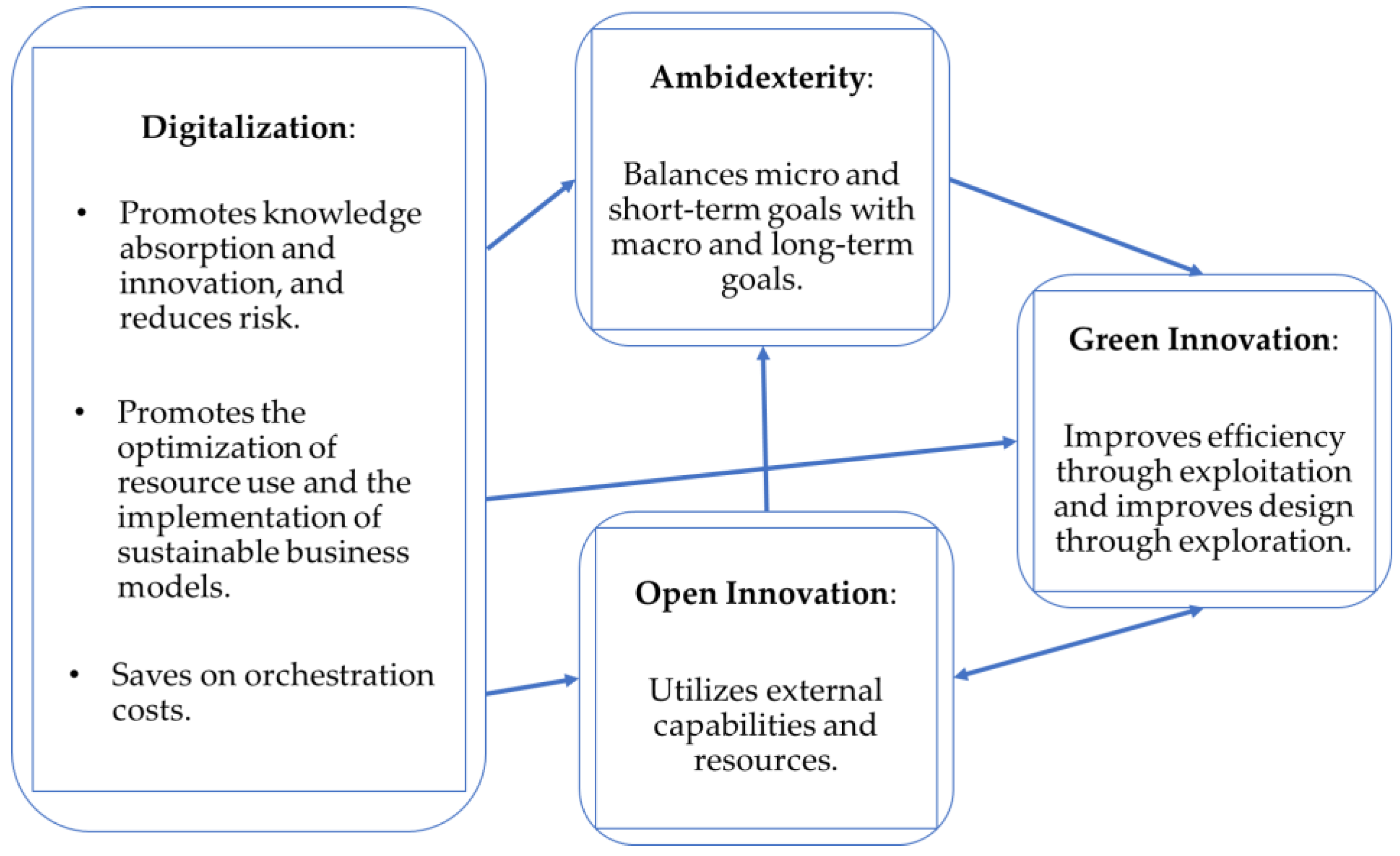

| Variable | What previous research has revealed so far | What future research should address |

| Digitalization | It enhances the competitive advantage of SMEs by combining with organizational ambidexterity to enable knowledge absorption under cost constraints, respond to radical innovation, and reduce risks. Furthermore, it contributes to open innovation, as well as green innovation and sustainability by facilitating orchestration cost savings and resource utilization optimization. | The main obstacles to digitalization among SMEs are a lack of financial and human resources, as well as a lack of understanding about the convenience of digitalization. It is necessary to consider how the government can provide specific support to overcome these obstacles. |

| Open Innovation | Leveraging external capabilities and resources compensates for shortfalls in internal assets and enables ambidexterity. | It is necessary to clarify strategies for reducing costs associated with orchestration, including digitalization. |

| Green Innovation | It is promoted by ambidexterity and has a mutually enhancing relationship with open innovation. | There is a need to understand the effects on performance when combined with digitalization, open innovation, and ambidexterity. |

| Ambidexterity | Although it has been primarily employed in relation to performance, recent research has shown its potential to be driven by digitalization and open innovation, thus stimulating green innovation. | A new framework is needed that positions ambidexterity not just as a micro- or short-term goal of the development of individual companies, but also as part of a strategy for achieving macro- or long-term goals for the sustainability of the planet. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).