1. Introduction

Advancing anticancer therapies is a significant challenge due to the intricate nature of tumor biology and the persistent issue of drug resistance [

1]. While conventional small-molecule drugs have been highly effective in cancer treatment, their long-term use can be limited by toxicity, off-target effects, and the emergence of multidrug resistance (MDR). MDR arises through various mechanisms, including enhanced drug efflux, metabolic adaptation, and alterations in drug targets, ultimately reducing therapeutic efficacy [

2]. This issue is especially critical in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), an aggressive malignancy with one of the highest cancer-related mortality rates. Its poor prognosis stems from multiple factors, including the rapid emergence of drug resistance, which significantly limits treatment effectiveness [

3]. These challenges have led to growing interest in alternative strategies, such as natural product-based compounds, which may complement existing treatments by targeting resistance pathways while offering potentially improved safety profiles [

4].

Plant-derived bioactive compounds, particularly polyphenols, hold promise in oncology due to their antioxidative effects, regulation of signaling pathways, and potential to enhance chemosensitivity [

5]. Antioxidants play a crucial role in mitigating oxidative stress, a factor implicated in cancer progression and resistance to therapy [

6]. Their ability to modulate the tumor microenvironment, influence immune responses, and synergize with conventional treatments could make them valuable in cancer management. Several plant-derived compounds have already demonstrated clinical success, underscoring the importance of further exploration in this area. For instance, paclitaxel, a taxane originally extracted from

Taxus brevifolia, is widely used to treat various malignancies, including breast, ovarian, and lung cancers [

7]. Similarly, vinblastine and vincristine, alkaloids derived from

Catharanthus roseus, are essential components of chemotherapy regimens for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors [

8]. Additionally, camptothecin, isolated from

Camptotheca acuminata, has led to the development of topoisomerase inhibitors such as irinotecan and topotecan, which are used in colorectal, ovarian, and small-cell lung cancers [

9]. These examples highlight the immense potential of plant-derived compounds in oncology and reinforce the need to investigate novel bioactive molecules with improved efficacy and safety profiles.

Beyond these well-established plant-derived chemotherapeutics, other natural compounds continue to attract attention for their potential anticancer properties. One such example is Curcumin—a polyphenol extracted from

Curcuma longa—has demonstrated a broad spectrum of biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects [

10]. However, its clinical application has been hindered by challenges such as poor bioavailability and rapid metabolism, limiting its therapeutic potential [

11].

One approach to addressing these limitations is the use of cyclodextrin (CD) encapsulation, which has been shown to enhance the solubility, metabolic stability, and bioavailability of polyphenolic compounds, including curcumin [

12]. Cyclodextrins, cyclic oligosaccharides derived from starch degradation, act as encapsulation agents that can improve the chemical and physical properties of bioactive molecules by forming inclusion complexes [

13]. Studies have demonstrated that β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) and its derivatives, such as hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) and randomly methylated-β-cyclodextrin (RM-β-CD), enhance the aqueous solubility of curcumin and improve the bioavailability [

14]. In short, this represents a promising avenue for optimizing curcumin and its derivatives, potentially paving the way for their clinical application as therapeutic agents.

ABC transporters play a crucial role in cancer resistance by actively exporting drugs from cells, reducing intracellular concentrations, and promoting chemoresistance [

15]. These membrane transporters are involved in various mechanisms of drug resistance, affecting the efficacy of many chemotherapeutic agents, including cisplatin, taxanes, and anthracyclines [

16]. One notable member of this family is ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3), also known as multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 (MRP3). ABCC3 plays a key role in drug disposition and has been implicated in cancer cell survival and proliferation, particularly in pancreatic cancer [

17]. Indeed, in addition to its role in drug resistance, we and others have found that ABC transporters actively contribute to cancer progression by extruding bioactive molecules that can influence the tumor microenvironment [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Their role in modulating drug response and promoting cancer progression makes them a relevant target for potential therapeutic interventions. Strategies to counteract ABC transporter-mediated resistance include the development of small-molecule inhibitors, combination therapies to enhance drug retention, and natural compound-based approaches that modulate transporter activity [

22]. Targeting these mechanisms could improve chemotherapy efficacy and help overcome treatment resistance in cancers such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, where drug efflux plays a significant role in therapeutic failure. Notably, ABCC3 inhibitors have the potential to not only enhance drug retention but also impede tumor progression by blocking the extrusion of bioactive molecules that contribute to the tumor microenvironment and cancer cell survival [

21].

In this study, we performed a ligand-based virtual screening approach on the diverse and proprietary Eurofins-VillaPharma library containing both synthetic and plant-derived compounds. Given that ABCC3 is a challenging target for structure-based modeling due to its nature as a membrane-bound transporter and the limited availability of high-resolution 3D structures, we opted for a ligand-based strategy. By leveraging known ABCC3 ligands, we aimed to identify structurally diverse yet functionally relevant inhibitors. Among the four selected hits, dimethoxycurcumin, a methylated curcumin derivative, emerged as a promising candidate. Although our screening was not specifically tailored to identify plant-derived compounds, this finding highlights the power of unbiased virtual screening approaches in discovering promising therapeutic agents. Subsequent in vitro validation, including IC50 determination and cancer cell-line assays, supported its promising inhibitory effect on ABCC3 and its potential to prevent colony formation. The interaction between natural compounds and ABC transporters remains a promising avenue for enhancing treatment efficacy while reducing toxicity. By investigating functional antioxidants and their role in modulating drug resistance, this study expands the understanding of alternative therapeutic strategies in oncology. Further exploration of these mechanisms may contribute to the development of novel interventions for overcoming chemoresistance in cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vitrual Screening Using Consensus Fingerprint Similarity

The diverse and proprietary Eurofins-VillaPharma library was processed to generate three types of molecular fingerprints: Avalon [

23], Circular (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint with a diameter of 6, ECFP6) [

24], and PubChem Substructure fingerprints [

25], using the PyFingerprint package [

26]. This package leverages the RDKit [

27] for Avalon fingerprint generation, and the Chemistry Development Kit (CDK) [

28] for PubChem and Circular (ECFP6) fingerprints.

Initially, a custom script was developed to compare the query structure against the library. This script converted the input query on-the-fly into Avalon, PubChem, and Circular (ECFP6) fingerprints and subsequently compared them to the corresponding fingerprints in the Eurofins-VillaPharma library using the Euclidean distance metric. To ensure comparability across fingerprints, the distances were normalized using z-score normalization, where each value was scaled based on the mean and standard deviation of its distribution, resulting in a standardized score for each fingerprint type.

The final consensus score for each compound was obtained by averaging these normalized scores across all three fingerprint types. Compounds were then ranked based on their consensus scores, with higher-ranking compounds selected for further evaluation. This consensus approach attempts to reduce fingerprint-specific biases and provide a more robust prediction of potential hits, while also increasing the chemical diversity among the top-ranked compounds.

To facilitate reproducibility and improve usability, this initial screening script was further developed into ConFiLiS (Consensus Fingerprints for Ligand-based Screening) [

29], an open-source tool that refines the original methodology with improved preprocessing and performance, while maintaining the core principles of the original approach. The tool, along with detailed documentation and usage instructions, is publicly available on GitHub:

https://github.com/Jnelen/ConFiLiS.

2.2. Hit Comparison Against BindingDB

To assess the structural novelty of the identified hits, all known ABCC3-active compounds were retrieved from BindingDB [

30] and converted into Morgan fingerprints (radius 2, 2048 bits) using RDKit. The Morgan fingerprinting method, which is based on extended-connectivity circular fingerprints (ECFP), was chosen for its ability to effectively capture molecular substructures and functional groups that contribute to biological activity, making it particularly suitable for structural similarity analysis in drug discovery.

To quantify structural similarity, we computed Tanimoto similarity coefficients between each hit and all known ABCC3-active compounds present in the BindingDB dataset. The Tanimoto coefficient, a widely used metric in cheminformatics, measures the degree of overlap between two molecular fingerprint representations, yielding a numerical value between 0 (no similarity) and 1 (identical structures). This allowed us to identify, for each hit, the most structurally similar known ABCC3-associated compound in BindingDB. This step was critical to determine whether the identified hits represented novel chemical scaffolds or bore close resemblance to previously reported inhibitors. Following this computational similarity analysis, we conducted a manual review process to compare the similarity to the closest known ABCC3-associated compounds identified for each hit. This manual curation step was essential for prioritizing hits with novel chemical scaffolds, thereby minimizing the risk of rediscovering previously known inhibitors while maximizing the potential for identifying structurally distinct ABCC3-targeting compounds.

2.3. Viability Assays

HPAF-II, BxPC3, and CFPAC cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells per well and allowed to adhere for 24 hours under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). Cells were then treated with the indicated compounds at varying concentrations for an additional 72 hours to assess dose-dependent effects on viability.

Following the treatment period, cell viability was evaluated by measuring the metabolic activity of live cells. The cells were first fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to preserve morphology and prevent detachment. They were then stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 15 minutes to label adherent cells. Excess dye was removed by gently washing the wells with deionized water, and plates were left to air-dry completely.

To quantify cell viability, the bound crystal violet dye was solubilized using 0.1M sodium citrate, and absorbance was measured at 590 nm using a microplate reader (EnSpire, PerkinElmer). The optical density (OD) values obtained reflected the relative number of viable, adherent cells, providing a quantitative measure of treatment efficacy. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility, and background absorbance was subtracted using wells containing only the staining solution. Graphics and IC₅₀ calculations were carried out using GraphPad Prism v10.0.

2.4. Clonogenic Assays

BxPC3 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 500 cells per well and incubated in complete medium at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 12 days to allow colony formation. The medium was refreshed every three days to maintain optimal growth conditions.

For treatment experiments, the medium was supplemented with the indicated concentrations of DMSO or test compounds, ensuring continuous drug exposure throughout the incubation period. After 12 days, colony formation was assessed by first fixing the cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature to preserve cellular structure and prevent detachment. The colonies were then stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution for 30 minutes to enhance visualization. Excess dye was removed by gently rinsing the wells multiple times with deionized water, and the plates were air-dried.

Colony formation was visualized using a bright-field microscope, and images were captured for documentation. Colonies were manually counted to quantify clonogenic potential. Alternatively, to achieve higher sensitivity and automated quantification, fixed colonies were stained with HCS CellMask™ Deep Red (cat. no. H32721, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, cat. no. D1306, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Fluorescent images were acquired and analyzed using the IN-Cell Analyzer 2200 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to provide a more precise and reproducible assessment of colony formation.

All experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure statistical reliability, and appropriate controls were included to account for background staining and autofluorescence.

3. Results

3.1. Virtual Screening Using Consensus Fingerprint Similarity

To identify potential ABCC3 inhibitors, we employed a consensus fingerprint-based virtual screening approach using known ABCC3-active compounds from BindingDB as a reference. Compound BDBM50302828, with a reported IC50 of 1.1 µM, was chosen as the starting structure. At the time of selection, it was the most potent small-molecule drug for ABCC3 listed in BindingDB, making it the most suitable candidate.

To maximize chemical diversity and ensure broad structural coverage, we generated three types of molecular fingerprints—Avalon, Circular (ECFP6), and PubChem substructure fingerprints—for both the query compound and the screening library. These fingerprints were then used to calculate Euclidean distances between the reference compound and each library entry. To standardize the results across different fingerprint types, we applied z-score normalization, which adjusts the distances based on the mean and standard deviation of each fingerprint distribution.

A consensus score was derived by averaging the normalized distances across all three fingerprint types, ensuring that hits were not disproportionately influenced by any single fingerprinting method. This approach prioritizes compounds that exhibit a consistent degree of similarity across multiple fingerprinting techniques, thus improving the likelihood of identifying true ABCC3 inhibitors rather than false positives arising from fingerprint-specific artifacts.

For the final selection, we applied a consensus score cutoff of -2.5, meaning that only compounds with the highest relative structural resemblance to the reference compound across all fingerprint types were considered for further evaluation. This threshold was chosen to balance hit diversity with structural relevance, enabling us to focus on compounds with a meaningful likelihood of inhibiting ABCC3 while minimizing excessive structural redundancy. The selected hits were subsequently subjected to further computational and experimental validation to assess their potential as novel ABCC3 inhibitors.

Table 1 summarizes the Euclidean distances for each fingerprint type, along with their normalized counterparts (Dist and Norm respectively). The consensus score was computed as the average of these normalized distances and served as the basis for the final ranking of compounds. Only compounds with a consensus score below -2.5 were considered for further testing.

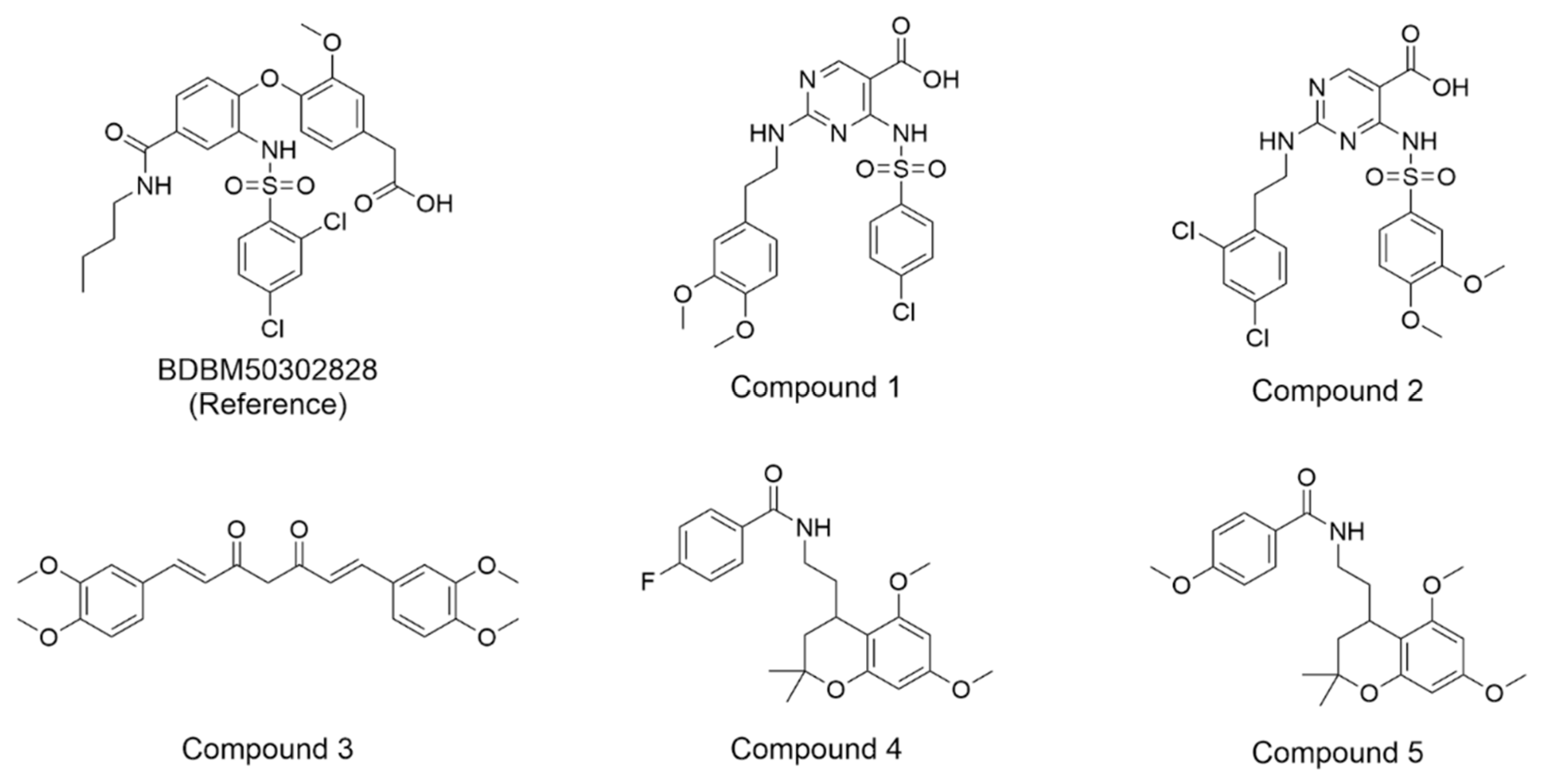

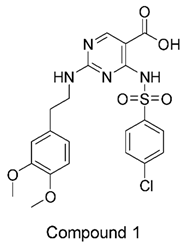

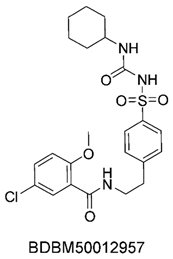

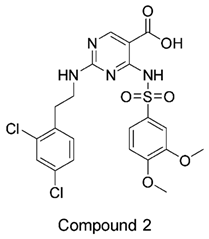

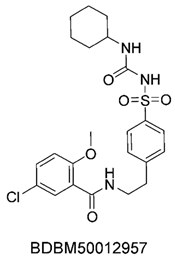

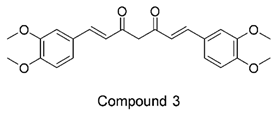

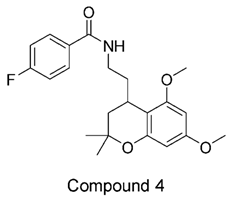

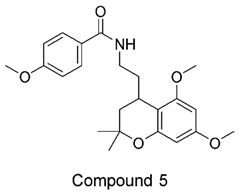

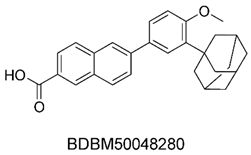

The compound structures, along with the BDBM50302828 reference compound, are shown in

Figure 1. It is noteworthy that these five compounds represent three distinct scaffolds. Compounds 1 and 2 share structural features, including a sulfonamide moiety, which is also present in the reference compound. Additionally, Compounds 4 and 5 feature a 5,7-dimethoxy-2,2-dimethylchromane based scaffold linked to a benzamide moiety.

This structural diversity suggests that different scaffolds capture distinct features from the query structure, potentially interacting with ABCC3 through varied binding modes. Notably, Compound 3 exhibits a high degree of structural similarity to Curcumin, differing only by the methylation of both hydroxyl groups into methoxy groups.

In short, our screening approach resulted in a set of structurally diverse hits, underscoring the potential of consensus fingerprint similarity techniques in virtual screening workflows. The observed chemical diversity among the top-ranked hits highlights the utility of integrating multiple fingerprint types to mitigate model-specific biases and expand the structural search space.

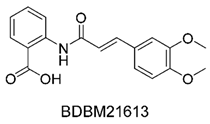

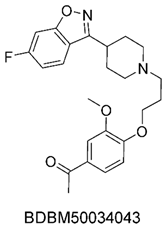

3.2. BindingDB Similarity Analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the structural characteristics of the identified hits, we compared them to known ABCC3-active compounds from BindingDB. This analysis aimed to uncover the structural relationships between the predicted hits and previously reported ABCC3 inhibitors. In total, 1849 ABCC3-related entries were retrieved and used as a reference set. Each hit was compared to this reference set by calculating Tanimoto similarity scores using Morgan (ECFP4) fingerprints, and the closest known compound was identified for each hit.

The results of this similarity analysis are compiled into

Table 2, which lists each predicted hit, its closest known ABCC3 compound, and the corresponding Tanimoto similarity score calculated using the Morgan (ECFP4) fingerprint. A subsequent manual assessment was performed to evaluate the distinctiveness of each hit, ensuring that structurally novel candidates were prioritized for further testing while minimizing the likelihood of rediscovering known inhibitors.

None of our predicted hits exactly matched any known ABCC3 inhibitors deposited in BindingDB. However, among all compounds in BindingDB, Compounds 1 and 2 were structurally closest to the original query compound, BDBM50302828, with Tanimoto similarity scores of 0.3810 and 0.3222, respectively. This structural similarity is likely due to the presence of a common sulfonamide moiety. Compound 3, also known as dimethoxycurcumin, exhibited the highest similarity to any of the known ABCC3-active compounds, with a Tanimoto similarity of 0.5556. Although this similarity is relatively high, the structure was deemed sufficiently distinct to warrant testing, given the presence of amide and benzoic acid moieties in the bindingDB compound, which are not found in the predicted hit compound. Furthermore, the natural product-like characteristics of this compound made it an interesting candidate for further exploration. Finally, Compounds 4 and 5 were found to be the most distinct from any of the known compounds, with Tanimoto similarities of 0.2637 and 0.2703, respectively. Interestingly, despite their high structural similarity—differing only by the presence of either a fluoro or methoxy group on the para position of the terminal benzene ring—their closest known compounds were different.

3.3. Determine Activity Using Cellular Assays

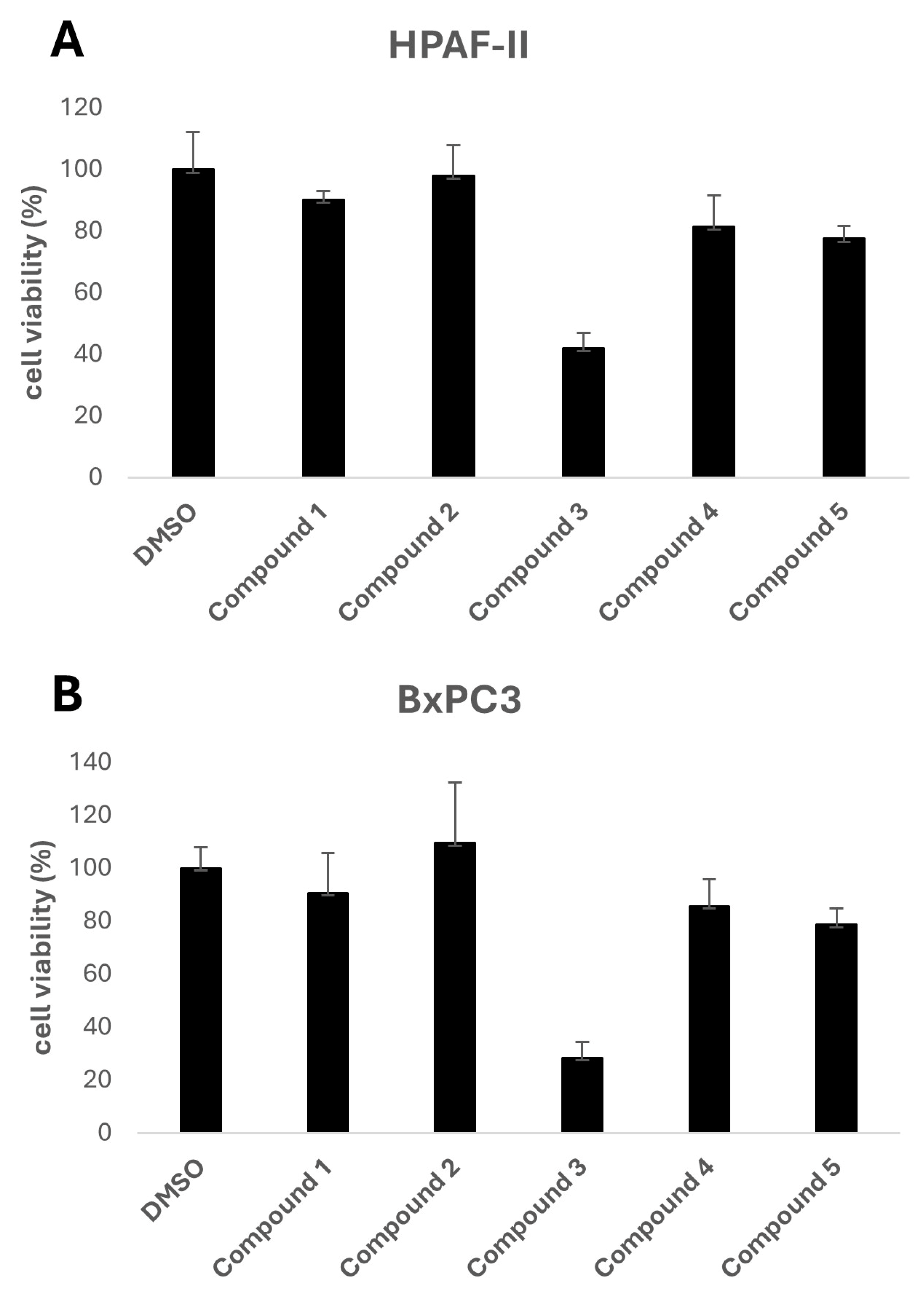

The biological activity of the five selected compounds was evaluated using a panel of human pancreatic cancer cell lines, including HPAF-II, BxPC3, and CFPAC. Initial screening was performed to assess their impact on cell growth by treating the cells with a fixed concentration of 10 μM for HPAF-II and BxPC3, as shown in

Figure 2. Among the tested compounds, Compound 3, a methylated derivative of curcumin, exhibited the highest activity.

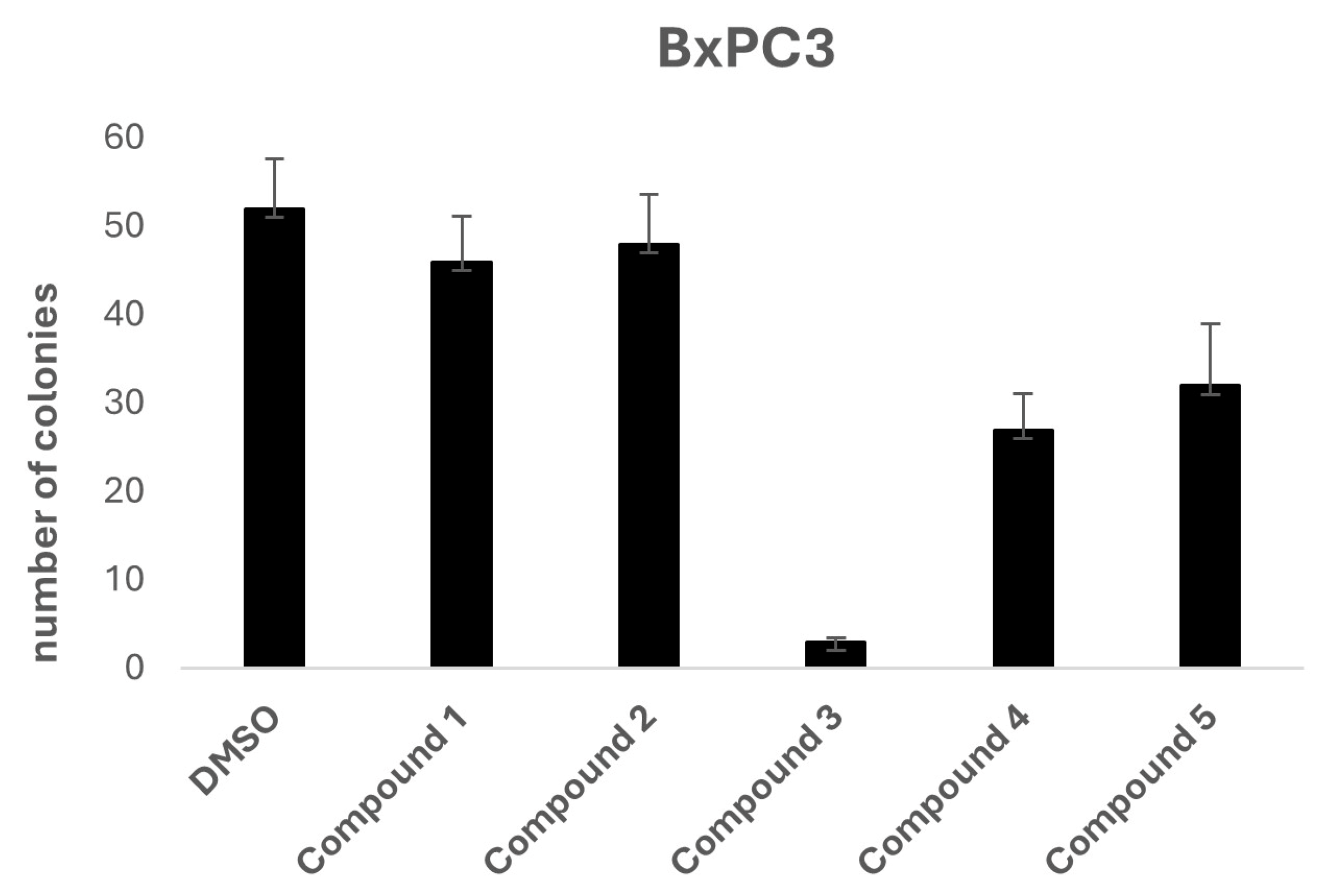

To further investigate the potential anti-tumorigenic properties of the selected compounds, a two-dimensional colony formation assay was conducted using the BxPC3 cell line. At a concentration of 10 μM, Compound 3 again stood out as the most effective candidate, completely inhibiting colony formation, indicating its potential for disrupting cancer cell proliferation.

Figure 3.

Effects of 10 μM Compound 3 onon BxPC3 cell colony formation. Data is presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Effects of 10 μM Compound 3 onon BxPC3 cell colony formation. Data is presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

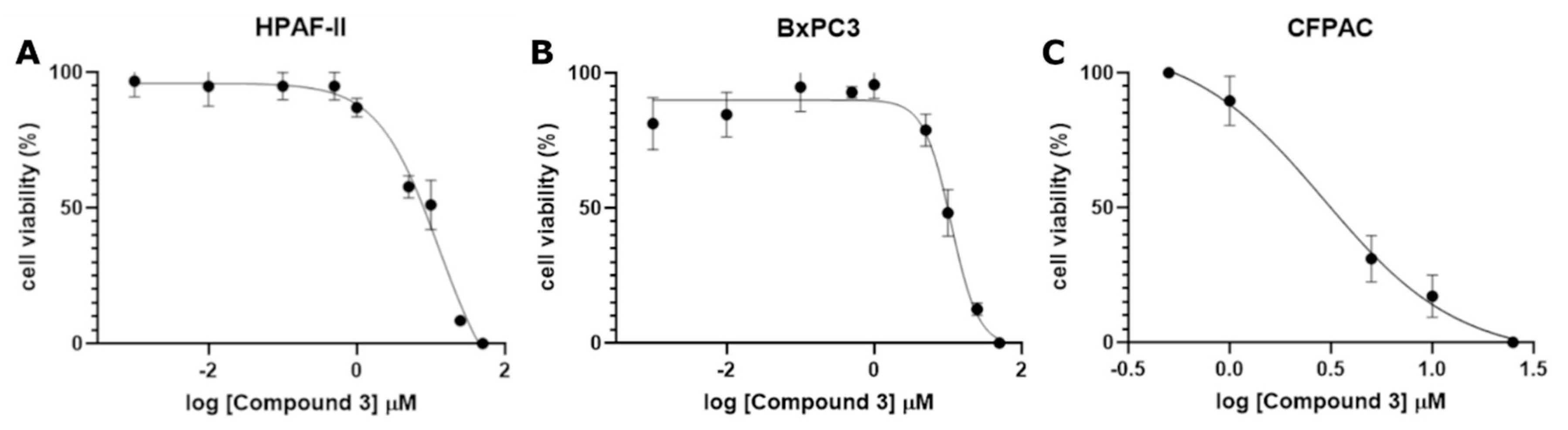

To further characterize its potency, Compound 3 was tested across a range of concentrations (1 nM to 50 μM) to determine the IC50 value using a crystal violet viability assay for three different cancer cell lines: HPAF-II, BxPC3, and CFPAC. Compound 3 demonstrated the strongest growth inhibition, yielding IC50 values of 11.03 μM, 12.90 μM, and 2.91 μM for HPAF-II, BxPC3, and CFPAC, respectively.

Figure 4.

Dose-Response curve of Compound 3 for IC50 determination in A) HPAF-II (0.001–50 µM), B) BxPC3 (0.001–50 µM), and C) CFPAC (0.1–25 µM) cell lines. Data is presented as the mean ± SD of the three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Dose-Response curve of Compound 3 for IC50 determination in A) HPAF-II (0.001–50 µM), B) BxPC3 (0.001–50 µM), and C) CFPAC (0.1–25 µM) cell lines. Data is presented as the mean ± SD of the three independent experiments.

4. Discussion

Multidrug resistance (MDR) remains a central obstacle in effective chemotherapy, particularly in aggressive solid tumors such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Central to this resistance mechanism are ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, with ABCC3 (MRP3) emerging as a critical mediator of chemotherapeutic drug efflux and tumor progression. Identifying novel and potent modulators of ABCC3 is therefore crucial in advancing therapeutic strategies to overcome resistance and improve patient outcomes.

In this study, we leveraged ConFiLiS, a robust virtual screening tool employing consensus fingerprint similarity scoring, to identify structurally diverse inhibitors of ABCC3 from the Eurofins-VillaPharma compound library. By integrating multiple molecular fingerprint types—Avalon, ECFP6, and PubChem substructure—our approach mitigated fingerprint-specific biases, enabling the discovery of structurally varied hits with potential pharmacological activity. The resulting compounds are grouped into three distinct chemotypes: sulfonamide-containing molecules (Compounds 1 and 2), dimethoxy-2,2-dimethylchromane based scaffolds linked to a benzamide moiety (Compounds 4 and 5), and a methylated curcumin derivative, dimethoxycurcumin (Compound 3).

Our structural similarity analysis against known ABCC3 ligands in BindingDB reinforced the novelty of our predicted compounds. Dimethoxycurcumin demonstrated a relatively high structural similarity to a known ABCC3-active compound (Tanimoto coefficient 0.5556), yet retained distinct pharmacophoric differences, particularly the absence of amide and benzoic acid functionalities, which made it still interesting to investigate further. The observed structural differences, despite sharing common molecular features with known inhibitors, underscore the chemical novelty achievable through unbiased ligand-based screening, emphasizing subtle yet potentially impactful modifications that could affect biological activity or potency.

In vitro evaluation confirmed the biological relevance of dimethoxycurcumin, which demonstrated potent activity across multiple PDAC cell lines. At a concentration of 10 µM, it substantially reduced cell viability and completely inhibited colony formation—key indicators of anti-proliferative efficacy and the ability to impair long-term clonogenic potential. The compound’s IC₅₀ values ranged from 2.91 to 12.90 µM, depending on the cell line, highlighting consistent anti-tumor activity in a physiologically relevant concentration range. Although these IC₅₀ values are higher in absolute terms (~1 order of magnitude) than that of the original query compound, BDBM50302828—reported to inhibit ABCC3 with an IC₅₀ of 1.1 µM in a membrane vesicle-based assay—it is important to consider the distinct nature of the experimental models. BDBM50302828 was evaluated in a cell-free biochemical system designed to isolate transporter function [

31], whereas dimethoxycurcumin’s activity was assessed using whole-cell viability assays. These assays inherently integrate additional layers of biological complexity, including compound uptake, intracellular metabolism, off-target interactions, and potential synergistic mechanisms. As such, direct numerical comparison of IC₅₀ values between these systems may be misleading; instead, the results should be interpreted qualitatively, with an emphasis on the translational relevance of whole-cell phenotypic responses.

Beyond its role as a transporter inhibitor, dimethoxycurcumin’s antioxidant properties may act synergistically to enhance its anticancer activity. Oxidative stress is a well-established driver of cancer progression and chemoresistance, with high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) influencing tumor cell survival, metastasis, and drug sensitivity [

32]. By simultaneously inhibiting ABCC3-mediated drug resistance and mitigating oxidative stress, dimethoxycurcumin may exert a dual mechanism of action, increasing its therapeutic potential.

Furthermore, our discovery of dimethoxycurcumin extends the promising therapeutic potential of curcumin derivatives. Although the broad anticancer and antioxidant effects of curcumin have been extensively studied [

33], specific targeting of ABCC3 has remained largely unexplored. Previous work has reported curcumin’s effects on ABCC1 (MRP1) [

34] and ABCC5 (MRP5) [

35], attributing transporter inhibition largely to its polyphenolic core structure. Our study now introduces ABCC3 as an additional, therapeutically relevant target for optimized curcumin analogs, highlighting the potential improvement of structural modifications, such as methylation, in enhancing transporter specificity and anticancer efficacy.

An acknowledged limitation in the clinical development of curcumin has been its unfavorable pharmacokinetics, characterized by poor solubility, limited bioavailability, and rapid systemic clearance [

36]. However, recent advances in delivery technologies—including nanoparticle encapsulation, liposomes, and cyclodextrin complexation—present promising strategies to overcome these limitations [

37]. Applying similar formulation strategies to dimethoxycurcumin may significantly boost its bioavailability and clinical viability, facilitating translation from preclinical findings into practical therapeutic applications.

Moving forward, several promising avenues warrant further exploration. Firstly, elucidating the precise molecular interactions between dimethoxycurcumin and ABCC3 via experimental biochemical studies could provide invaluable insights into its mechanism of transporter inhibition. Secondly, assessing the compound’s specificity towards ABCC3 relative to other ABC transporters would better define its potential therapeutic window and minimize off-target effects. Finally, in vivo efficacy studies, particularly in relevant animal models of PDAC, combined with existing chemotherapeutics, could provide critical preclinical validation. Optimizing pharmacokinetics through strategic formulation approaches—such as those previously explored for curcumin analogs—could further enhance dimethoxycurcumin’s in vivo stability, improving its therapeutic potential.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the pressing challenge of drug resistance in aggressive cancers such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) by using a ligand-based virtual screening approach that combines multiple molecular fingerprint types. This consensus method led to the identification of dimethoxycurcumin, a methylated curcumin derivative, as a potential ABCC3 inhibitor. In vitro validation confirmed its ability to reduce cancer cell viability and inhibit colony formation, highlighting both its biological activity and the effectiveness of our screening strategy. These findings support the therapeutic relevance of targeting ABC transporters with natural product derivatives and underscore the value of integrating computational and experimental tools in anticancer drug discovery. This work contributes to the growing interest in functional antioxidants as adjuvants in cancer therapy and offers a foundation for the development of more effective treatments against multidrug-resistant tumors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.N. and H.P.-S.; methodology, J.N.; software, J.N.; validation, J.N. and V.N.; formal analysis, J.N. and V.N.; investigation, J.N. and V.N.; resources, J.M.V.-S., M.F. and H.P.-S.; data curation, J.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.N.; writing—review and editing, V.N., J.M.V.-S., M.F. and H.P.-S.; visualization, J.N. and V.N.; supervision, J.M.V.-S., M.F. and H.P.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

J. N. is funded by Cátedra Villapharma-UCAM. Powered@NLHPC: This research was partially supported by the supercomputing infrastructure of the NLHPC (CCSS210001). Supercomputing resources in this work have been supported by the Plataforma Andaluza de Bioinformática of the University of Málaga.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. However, data derived from or related to the Eurofins-VillaPharma compound library are proprietary and cannot be shared due to confidentiality agreements.

Conflicts of Interest

M.F. is a member of LIPOVEXA S.r.l., a spin-off company focused on developing innovative treatments for diabetes, obesity and liver health. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABCC3 |

ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 3 |

| (HP/RM-β-)CD |

(Hydroxypropyl/randomly methylated-β)-Cyclodextrin |

| CDK |

Chemistry Development kit |

| ConFiLiS |

Consensus Fingerprints for Ligand-based Screening |

| DAPI |

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| Dist |

Euclidean distance |

| ECFP(4/6) |

Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (with a diameter of 4/6) |

| MDR |

Multidrug resistance |

| MRP3 |

Multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 |

| Norm |

Normalized Euclidean distance |

| OD |

Optical density |

| PDAC |

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

References

- Hussain, S.; Singh, A.; Nazir, S.U.; Tulsyan, S.; Khan, A.; Kumar, R.; Bashir, N.; Tanwar, P.; Mehrotra, R. Cancer Drug Resistance: A Fleet to Conquer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 14213–14225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukowski, K.; Kciuk, M.; Kontek, R. Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamska, A.; Elaskalani, O.; Emmanouilidi, A.; Kim, M.; Abdol Razak, N.B.; Metharom, P.; Falasca, M. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Chemoresistance in Pancreatic Cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2018, 68, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, K.; Pathak, M.P.; Saikia, R.; Gogoi, U.; Sahariah, J.J.; Zothantluanga, J.H.; Samanta, A.; Das, A. Cancer Chemotherapy via Natural Bioactive Compounds. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2022, 19, e310322202888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazafa, A.; Rehman, K.-U.-; Jahan, N.; Jabeen, Z. The Role of Polyphenol (Flavonoids) Compounds in the Treatment of Cancer Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 72, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slika, H.; Mansour, H.; Wehbe, N.; Nasser, S.A.; Iratni, R.; Nasrallah, G.; Shaito, A.; Ghaddar, T.; Kobeissy, F.; Eid, A.H. Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids in Cancer: ROS-Mediated Mechanisms. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, B.A. How Taxol/Paclitaxel Kills Cancer Cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 2677–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.R.; Márquez, A.; Gumá, J.; Llanos, M.; Herrero, J.; Nieves, M.A. de las; Miramón, J.; Alba, E. Treatment of Stage I and II Hodgkin’s Lymphoma with ABVD Chemotherapy: Results after 7 Years of a Prospective Study. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 1798–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaiwa, N.; Maarouf, N.R.; Darwish, M.H.; Alhamad, D.W.M.; Sebastian, A.; Hamad, M.; Omar, H.A.; Orive, G.; Al-Tel, T.H. Camptothecin’s Journey from Discovery to WHO Essential Medicine: Fifty Years of Promise. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 223, 113639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaadam, B.; Şanlier, N. Curcumin, an Active Component of Turmeric (Curcuma longa), and Its Effects on Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotha, R.R.; Luthria, D.L. Curcumin: Biological, Pharmaceutical, Nutraceutical, and Analytical Aspects. Mol. Basel Switz. 2019, 24, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, E.; Grootveld, M.; Soares, G.; Henriques, M. Cyclodextrins as Encapsulation Agents for Plant Bioactive Compounds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, P.; Bhatia, M. Pharmaceutical Applications of Cyclodextrins and Their Derivatives. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2020, 98, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, N.M.; Sultana, A.; Terao, K.; Nakata, D.; Jo, A.; Urano, A.; Ishida, Y.; Gorantla, R.N.; Pandit, V.; Devi, K.; et al. Comparison and Correlation of in Vitro, in Vivo and in Silico Evaluations of Alpha, Beta and Gamma Cyclodextrin Complexes of Curcumin. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2014, 78, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robey, R.W.; Pluchino, K.M.; Hall, M.D.; Fojo, A.T.; Bates, S.E.; Gottesman, M.M. Revisiting the Role of ABC Transporters in Multidrug-Resistant Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajid, A.; Rahman, H.; Ambudkar, S.V. Advances in the Structure, Mechanism and Targeting of Chemoresistance-Linked ABC Transporters. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Ferro, R.; Lattanzio, R.; Capone, E.; Domenichini, A.; Damiani, V.; Chiorino, G.; Akkaya, B.G.; Linton, K.J.; De Laurenzi, V.; et al. ABCC3 Is a Novel Target for the Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2019, 73, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.I.; Williams, R.T.; Henderson, M.J.; Norris, M.D.; Haber, M. ABC Transporters as Mediators of Drug Resistance and Contributors to Cancer Cell Biology. Drug Resist. Updat. Rev. Comment. Antimicrob. Anticancer Chemother. 2016, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falasca, M.; Linton, K.J. Investigational ABC Transporter Inhibitors. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2012, 21, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanouilidi, A.; Casari, I.; Gokcen Akkaya, B.; Maffucci, T.; Furic, L.; Guffanti, F.; Broggini, M.; Chen, X.; Maxuitenko, Y.Y.; Keeton, A.B.; et al. Inhibition of the Lysophosphatidylinositol Transporter ABCC1 Reduces Prostate Cancer Cell Growth and Sensitizes to Chemotherapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Domenichini, A.; Capone, E.; Damiani, V.; Akkaya, B.G.; Linton, K.J.; Di Sebastiano, P.; Chen, X.; Keeton, A.B.; Ramirez-Alcantara, V.; et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of ABCC3 Slows Tumour Progression in Animal Models of Pancreatic Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan-Carlos, P.-D.M.; Perla-Lidia, P.-P.; Stephanie-Talia, M.-M.; Mónica-Griselda, A.-M.; Luz-María, T.-E. ABC Transporter Superfamily. An Updated Overview, Relevance in Cancer Multidrug Resistance and Perspectives with Personalized Medicine. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 1883–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedeck, P.; Rohde, B.; Bartels, C. QSAR − How Good Is It in Practice? Comparison of Descriptor Sets on an Unbiased Cross Section of Corporate Data Sets. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006, 46, 1924–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, D.; Hahn, M. Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PubChem Substructure Fingerprint v1.3.

- Ji, H.; Deng, H.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Z. Predicting a Molecular Fingerprint from an Electron Ionization Mass Spectrum with Deep Neural Networks. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 8649–8653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics. Https://Www.Rdkit.Org.

- Willighagen, E.L.; Mayfield, J.W.; Alvarsson, J.; Berg, A.; Carlsson, L.; Jeliazkova, N.; Kuhn, S.; Pluskal, T.; Rojas-Chertó, M.; Spjuth, O.; et al. The Chemistry Development Kit (CDK) v2.0: Atom Typing, Depiction, Molecular Formulas, and Substructure Searching. J. Cheminformatics 2017, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelen, J. Jnelen/ConFiLiS 2025.

- Liu, T.; Hwang, L.; Burley, S.K.; Nitsche, C.I.; Southan, C.; Walters, W.P.; Gilson, M.K. BindingDB in 2024: A FAIR Knowledgebase of Protein-Small Molecule Binding Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1633–D1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.E.; van Staden, C.J.; Chen, Y.; Kalyanaraman, N.; Kalanzi, J.; Dunn, R.T., II; Afshari, C.A.; Hamadeh, H.K. A Multifactorial Approach to Hepatobiliary Transporter Assessment Enables Improved Therapeutic Compound Development. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 136, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, G.-Y.; and Storz, P. Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer. Free Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Tommonaro, G. Curcumin and Cancer. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chearwae, W.; Wu, C.-P.; Chu, H.-Y.; Lee, T.R.; Ambudkar, S.V.; Limtrakul, P. Curcuminoids Purified from Turmeric Powder Modulate the Function of Human Multidrug Resistance Protein 1 (ABCC1). Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2006, 57, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Revalde, J.L.; Reid, G.; Paxton, J.W. Modulatory Effects of Curcumin on Multi-Drug Resistance-Associated Protein 5 in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011, 68, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of Curcumin: Problems and Promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayathri, K.; Bhaskaran, M.; Selvam, C.; Thilagavathi, R. Nano Formulation Approaches for Curcumin Delivery- a Review. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 82, 104326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).