Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Higher levels of prenatal care barriers, particularly system-level and informational barriers, would be associated with poorer maternal health outcomes.

- Informational barriers would mediate the relationship between substance use and maternal health.

The Three Delays Model

Study Materials, Variables, and Operational Definitions

2. Methods and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Theory and Practice

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACME | Average Causal Mediation Effect |

| ADE | Average Direct Effect |

| ADPH | Alabama Department of Public Health |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

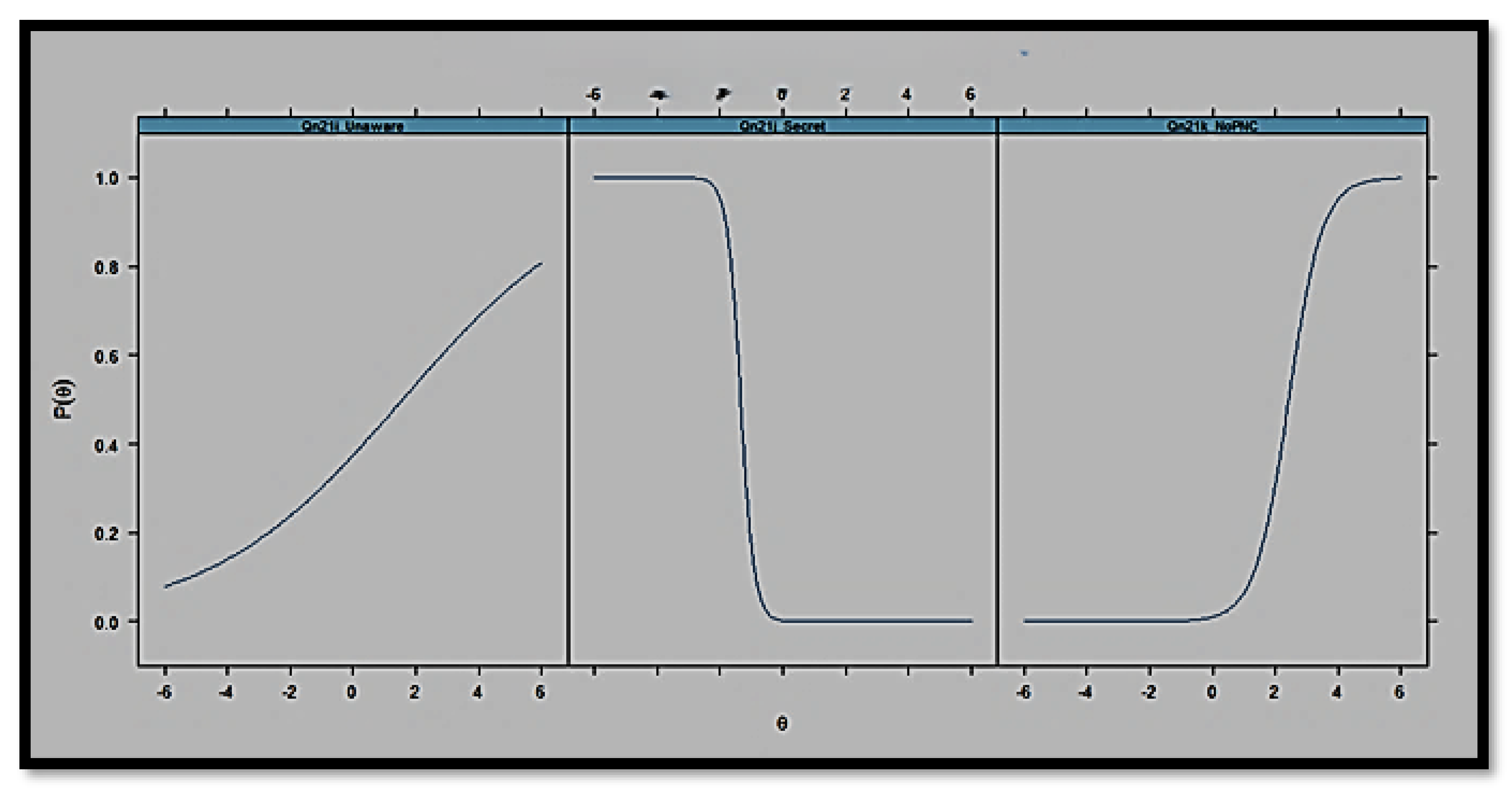

| IRT | Item Response Theory |

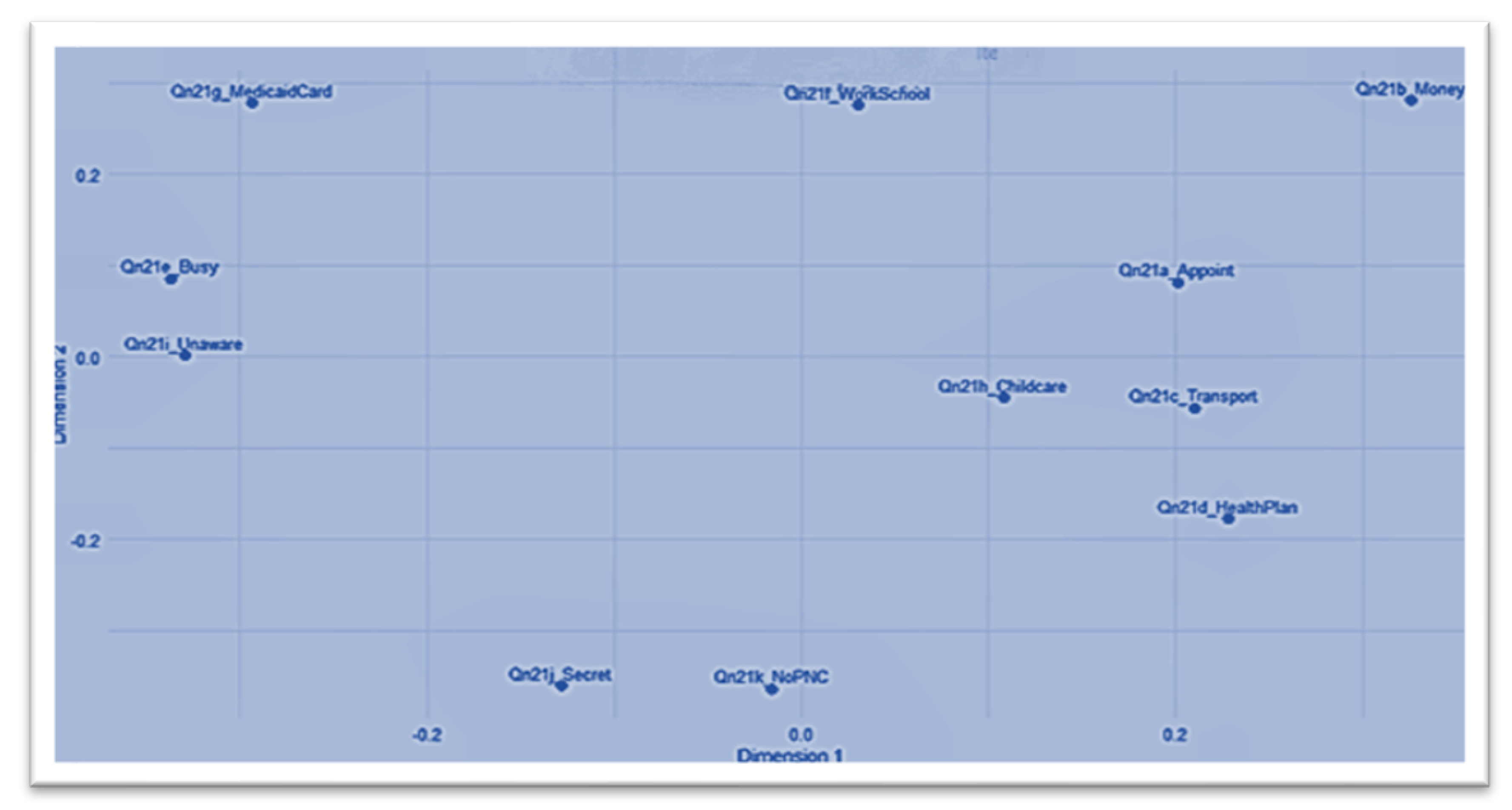

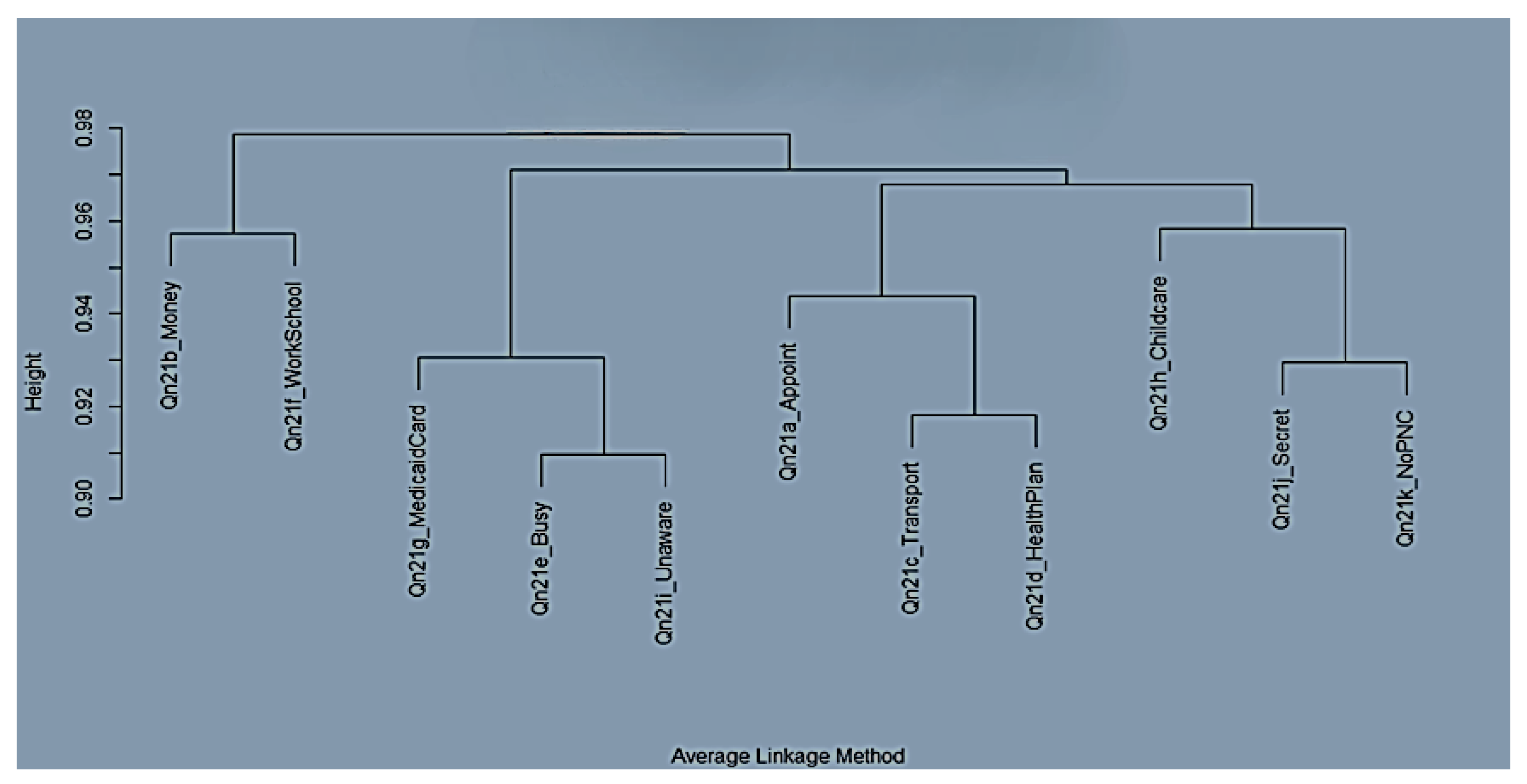

| MDS | Multidimensional Scaling |

| PNC | Prenatal Care |

| PRAMS | Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System |

| Qn21a | Alabama PRAMS Phase 8 Questionnaire #21a |

| Qn21b | Alabama PRAMS Phase 8 Questionnaire #21b |

| Qn21e | Alabama PRAMS Phase 8 Questionnaire #21e |

| Qn21f | Alabama PRAMS Phase 8 Questionnaire #21f |

| Qn21g | Alabama PRAMS Phase 8 Questionnaire #21g |

| Qn21i | Alabama PRAMS Phase 8 Questionnaire #21i |

| Qn21j | Alabama PRAMS Phase 8 Questionnaire #21j |

| Qn21k | Alabama PRAMS Phase 8 Questionnaire #21k |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SEM | Structural Equation Model |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

References

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Substance Use While Pregnant and Breastfeeding [Internet]. National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2020. Available from: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/substance-use-in-women/substance-use-while-pregnant-breastfeeding.

- CDC. Substance Use During Pregnancy [Internet]. Maternal Infant Health. 2024. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/pregnancy-substance-abuse/index.html.

- Brandon AR. Psychosocial Interventions for Substance Use During Pregnancy. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing 2014, 28, 169–77.

- Des Marais S. Cultural Differences in Substance Use [Internet]. Psych Central. 2022. Available from: https://psychcentral.com/addictions/cultural-context-and-influences-on-substance-abuse.

- Hirai AH, Ko JY, Owens PL, Stocks C, Patrick SW. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and Maternal Opioid-Related Diagnoses in the US, 2010-2017. JAMA 2021, 325, 146. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le C, Coombs S. Substance Use Disorder Hurts Moms & Babies [Internet]. National Partnership for Women & Families. 2021. Available from: https://nationalpartnership.org/report/substance-use-disorder-hurts-moms-and-babies/.

- Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Social Science & Medicine 1994, 38, 1091–110.

- Keating EM, Sakita F, Mmbaga BT, Amiri I, Getrude Nkini, Rent S, et al. Three delays model applied to pediatric injury care seeking in Northern Tanzania: A mixed methods study. PLOS Global Public Health. PLOS Global Public Health 2022, 2, e0000657–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elisa Garcia Gomez, Kitiezo Aggrey Igunza, Madewell ZJ, Akelo V, Onyango D, Shams El Arifeen, et al. Identifying delays in healthcare seeking and provision: The Three Delays-in-Healthcare and mortality among infants and children aged 1–59 months. PLOS global public health 2024, 4, e0002494–4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight HE, Self A, Kennedy SH. Why Are Women Dying When They Reach Hospital on Time? A Systematic Review of the “Third Delay.” Young RC, editor. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63846.

- Wilson CA, Finch E, Kerr C, Shakespeare J. Alcohol, smoking, and other substance use in the perinatal period. BMJ [Internet]. 2020 May 11;369:m1627. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1627.

- Pomar EG, Berryhill J, Bhattacharyya S. Evaluating maternal drug use disparities, risk factors and outcomes in Northeast Arkansas: a pre, during, and post-COVID-19 pandemic analysis. BMC Public Health 2025, 25.

- M. Pielage, Hanan El Marroun, Odendaal HJ, Willemsen SP, Manon, Eric A.P. Steegers, et al. Alcohol exposure before and during pregnancy is associated with reduced fetal growth: the Safe Passage Study. BMC Medicine 2023, 21.

- Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons; 2015.

- Jalali MS, Botticelli M, Hwang RC, Koh HK, McHugh RK. The opioid crisis: A contextual, social-ecological framework. Health Research Policy and Systems [Internet]. 2020 Aug 6;18(1):1–9. Available from: https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12961-020-00596-8.

- Save the Children. Applying the Three Delays Model: Improving access to care for newborns with danger signs [Internet]. 2013. Available from: https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/hnn-content/uploads/Applying-the-three-delays-model_Final.pdf.

- CDC. Polysubstance Use During Pregnancy [Internet]. Pregnancy. 2024. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/during/polysubstance-use.html.

- Office USGA. Maternal Health: HHS Should Improve Assessment of Efforts to Address Worsening Outcomes | U.S. GAO [Internet]. www.gao.gov. 2024. Available from: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-106271.

- Office on Women’s Health. Maternal Health | Office on Women’s Health [Internet]. OASH | Office on Women’s Health. 2022. Available from: https://womenshealth.gov/maternalhealth.

- World Health Organization. Maternal Health [Internet]. Who.int. World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health#tab=tab_1.

- Blanchin M, Guilleux A, Hardouin JB, Sébille V. Comparison of structural equation modelling, item response theory and Rasch measurement theory-based methods for response shift detection at item level: A simulation study. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 2019, 29, 096228021988457.

- Lu IRR, Thomas DR, Zumbo BD. Embedding IRT in Structural Equation Models: A Comparison With Regression Based on IRT Scores. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2005, 12, 263–77. [CrossRef]

- Phommachanh S, Essink DR, Wright PE, Broerse JEW, Mayxay M. Maternal health literacy on mother and child health care: A community cluster survey in two southern provinces in Laos. Fischer F, editor. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0244181.

- Zhao Y, Segalowitz N, Voloshyn A, Chamoux E, Ryder AG. Language barriers to healthcare for linguistic minorities: The case of second language-specific health communication anxiety. Health Communication 2019, 36, 1–13.

- Yadav R, Zaman K, Mishra A, Reddy MM, Shankar P, Yadav P, et al. Health Seeking Behaviour and Healthcare Utilization in a Rural Cohort of North India. Healthcare 2022, 10, 757. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey I, O’Brien M. Addressing Health Disparities Through Patient Education: The Development of Culturally-Tailored Health Education Materials at Puentes de Salud. Journal of Community Health Nursing 2011, 28, 181–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Operational Definition | Coding/Measurement | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Health Status | Refers to overall maternal health and operationalized as good vs. poor | The composite variable from Qn22 items is coded as 1 = good and 2 = poor | ADPH PRAMS Phase 8 data set (2016–2021) |

| Substance Use | This refers to pregnant women’s smoking behavior during pregnancy | The binary variable from Qn42_CigaretteCategory is coded as 0 = non-smoker and 1 = smoker | ADPH PRAMS Phase 8 data set (2016–2021) |

| Structural Barriers | This refers to the financial constraints and work/school conflicts experienced when accessing care | The composite score of Qn21b_Money and Qn21f_WorkSchool | ADPH PRAMS Phase 8 data set (2016–2021) |

| Informational Barriers | This refers to deficits in awareness or information regarding prenatal care | This is the IRT-derived latent trait (theta_info) from Qn21i_Unaware, Qn21j_Secret, and Qn21k_NoPNC | ADPH PRAMS Phase 8 data set (2016–2021) |

| System Barriers | This refers to barriers related to navigating the healthcare system | This is the composite score of Qn21a_Appoint and Qn21d_HealthPlan | ADPH PRAMS Phase 8 data set (2016–2021) |

| Age Group | This refers to the age category of the respondent | This is a categorical variable, grouped as 15–19, 20–24, and above | ADPH PRAMS Phase 8 data set (2016–2021) |

| Race/Ethnicity | This refers to the self-reported race and ethnicity of respondents | This is a categorical variable coded as 1 = Non-Hispanic White, 2 = Non-Hispanic Black, and 3 = Hispanic | ADPH PRAMS Phase 8 data set (2016–2021) |

| Qn79_Income Category | This refers to the household income level reported by respondents (Qn79 items) | This is a categorical variable, with income categories ranging from $0 to $16,000, $16,001 to $20,000, $20,001 to $24,000, $24,001 to $28,000, and above | ADPH PRAMS Phase 8 data set (2016–2021) |

| BMI Category | This refers to the body mass index (BMI) classification provided by the Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH) | This is a categorical variable, coded as 1 = Healthy Weight, 2 = Overweight, and 3 = Obesity | ADPH PRAMS Phase 8 data set (2016–2021) |

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Health Status | Good (1) Poor (2) |

287 246 |

53.8 46.2 |

| Substance Use | Non-smoker Smoker |

321 212 |

60.2 39.8 |

| Qn21a_Appoint | 0 1 |

304 229 |

57.0 43.0 |

| Qn21b_Money | 0 1 |

356 177 |

66.8 33.2 |

| Qn21c_Transport | 0 1 |

468 65 |

87.8 12.2 |

| Qn21d_HealthPlan | 0 1 |

403 130 |

75.6 24.4 |

| Qn21e_Busy | 0 1 |

441 92 |

82.7 17.3 |

| Qn21f_WorkSchool | 0 1 |

482 51 |

90.4 9.6 |

| Qn21g_MedicaidCard | 0 1 |

387 146 |

72.6 27.4 |

| Qn21h_Childcare | 0 1 |

500 33 |

93.8 6.2 |

| Qn21i_Unaware | 0 1 |

371 162 |

69.6 30.4 |

| Qn21j_Secret | 0 1 |

480 53 |

90.1 9.9 |

| Qn21k_NoPNC | 0 1 |

512 21 |

96.1 3.9 |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory |

$0 to $16,000 $16,001 to $20,000 $20,001 to $24,000 $24,001 to $28,000 $28,001 to $32,000 $32,001 to $40,000 $40,001 to $48,000 $48,001 to $57,000 $57,001 to $60,000 $60,001 to $73,000 $73,001 to $85,000 $85,001 or more |

123 65 37 25 37 28 21 28 15 25 24 105 |

23.1 12.2 6.9 4.7 6.9 5.3 3.9 5.3 2.8 4.7 4.5 19.7 |

| BMI_Category | Healthy Weight Obesity Weight Overweight Weight Underweight Weight |

226 180 117 10 |

42.4 33.8 22.0 1.9 |

| Age_Group | 15–19 20–24 25–29 30–34 35–39 40 or older |

35 136 163 130 60 9 |

6.6 25.5 30.6 24.4 11.3 1.7 |

| Race_Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White Non-Hispanic Black Hispanic Origin |

290 184 59 |

54.4 34.5 11.1 |

| Predictor | OR | Std. Error | z value | p | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.753 | 0.448 | -0.631 | 0.528 | [0.310, - 1.812] |

| Smoker_statussmoker | 0.698 | 0.192 | -1.870 | 0.061 | [0.478, - 1.015] |

| Structural_barriers_new | 1.077 | 0.329 | 0.225 | 0.821 | [0.564,- 2.056] |

| System_barriers_new | 1.766 | 0.286 | 1.986 | 0.046 | [1.009, - 3.108] |

| Theta_info | 2.422 | 0.186 | 4.745 | < .001 | [1.710, - 3.568] |

| Age_Group20-24 | 0.953 | 0.408 | -0.117 | 0.906 | [0.428, -2.144] |

| Age_Group25-29 | 1.090 | 0.400 | 0.215 | 0.829 | [0.498, - 2.409] |

| Age_Group30-34 | 1.017 | 0.412 | 0.041 | 0.967 | [0.453, - 2.302] |

| Age_Group35-39 | 0.772 | 0.462 | -0.560 | 0.575 | [0.311, - 1.918] |

| Age_Group40 or older | 1.767 | 0.793 | 0.718 | 0.473 | [0.374, -8.960] |

| Race_EthnicityNon-Hispanic Black | 1.278 | 0.200 | 1.225 | 0.220 | [0.863, -1.894] |

| Race_EthnicityHispanic Origin | 1.258 | 0.301 | 0.764 | 0.445 | [0.696, -2.274] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory16,001to20,000 | 0.692 | 0.329 | -1.118 | 0.263 | [0.361,- 1.315] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory20,001 to24,000 | 0.964 | 0.392 | -0.093 | 0.926 | [0.445, - 2.087] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory24,001to28,000 | 0.726 | 0.476 | -0.672 | 0.501 | [0.280, - 1.833] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory28,001to32,000 | 0.890 | 0.400 | -0.292 | 0.770 | [0.405, - 1.951] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory32,001to40,000 | 1.105 | 0.441 | 0.226 | 0.821 | [0.463, -2.640] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory40,001to48,000 | 1.201 | 0.505 | 0.362 | 0.717 | [0.442, - 3.266] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory48,001to57,000 | 0.830 | 0.439 | -0.425 | 0.671 | [0.347, -1.962] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory57,001to60,000 | 0.7287383 | 0.590 | -0.540 | 0.590 | [0.220, -2.289] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory60,001to73,000 | 1.040 | 0.458 | 0.082 | 0.935 | [0.419, - 2.560] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory73,001to85,000 | 0.874 | 0.470 | -0.287 | 0.774 | [0.343, -2.200] |

| Qn79_IncomeCategory$85,001 or more | 0.883 | 0.280 | -0.443 | 0.660 | [0.509, - 1.529] |

| BMI_CategoryObesity Weight | 1.071 | 0.213 | 0.324 | 0.746 | [0.706, - 1.627] |

| BMI_CategoryOverweight Weight | 1.074 | 0.242 | 0.295 | 0.768 | [0.668, -1.726] |

| BMI_CategoryUnderweight Weight | 0.786 | 0.690 | -0.350 | 0.728 | [0.187, - 3.020] |

| Effect | Estimate | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACME (Average) | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.05] | .006 *** |

| ADE (Average) | -0.08 | [-0.16, 0.00] | .056 |

| Total Effect | -0.05 | [-0.13, 0.04] | .232 |

| Prop. Mediated (Average) | -0.44 | [-4.62, 4.34] | .238 |

| Parameter | Estimate | Std. Error | z-value | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator Equation | |||||

| Smoker_status (a) | 0.143 | 0.058 | 2.453 | .014 | [0.029, 0.257] |

| Outcome Equation | |||||

| Theta_info (d) | 0.530 | 0.079 | 6.683 | < .001 | [0.375, 0.685] |

| Smoker_status (c′) | –0.199 | 0.111 | –1.797 | .072 | [–0.417, 0.019] |

| Defined Effects | |||||

| Indirect Effect (a*d) | 0.076 | 0.032 | 2.363 | .018 | [0.013, 0.139] |

| Total Effect | –0.123 | 0.112 | –1.106 | .269 | [–0.343, 0.097] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).