Introduction

Interim fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) play a significant role in maintaining stable oral conditions during final FDP construction through the following: prevention of tilting and super-eruption of reduced abutments or opposing and neighboring teeth, protection of reduced abutments from sensitivity and pulpal inflammation if exposed directly to oral environment, and allowing healthy soft tissue healing around the dental prosthesis. In addition, interim FDPs have an important functional and esthetic role by mimicking the final dental prosthesis form and dimensions. This way the prosthodontist can check esthetics and function before delivery of the final FDP [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

While the typical duration for a temporary FDP is one to two weeks, it can be used for an extended period (ranging from 6 months to up to 1 year) in certain situations, such as during a two-stage implant treatment protocol, adjusting the patient’s vertical dimension (raising the vertical dimension of occlusion), or restoring abutments with uncertain prognosis. In the last case, more affordable materials can be utilized for FDP fabrication during the abutment monitoring phase before the final prosthesis is constructed, or in emergency palliative care for medically compromised patients, such as cancer patients. In such instances, the term "long-term interim FDP" is applied [

6].

Interim FDPs are conventionally fabricated chairside using traditional techniques, such as powder-liquid systems and resin paste. However, with the advent of digital dentistry and the integration of technology into routine dental practice, additional fabrication methods have become available. This involves computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) which includes milling from prefabricated blanks and three-dimensional (3D) printing of light sensitive resins. These contemporary techniques have significantly enhanced the accuracy, stability, aesthetics, and fabrication speed of interim FDPs [

2,

7].

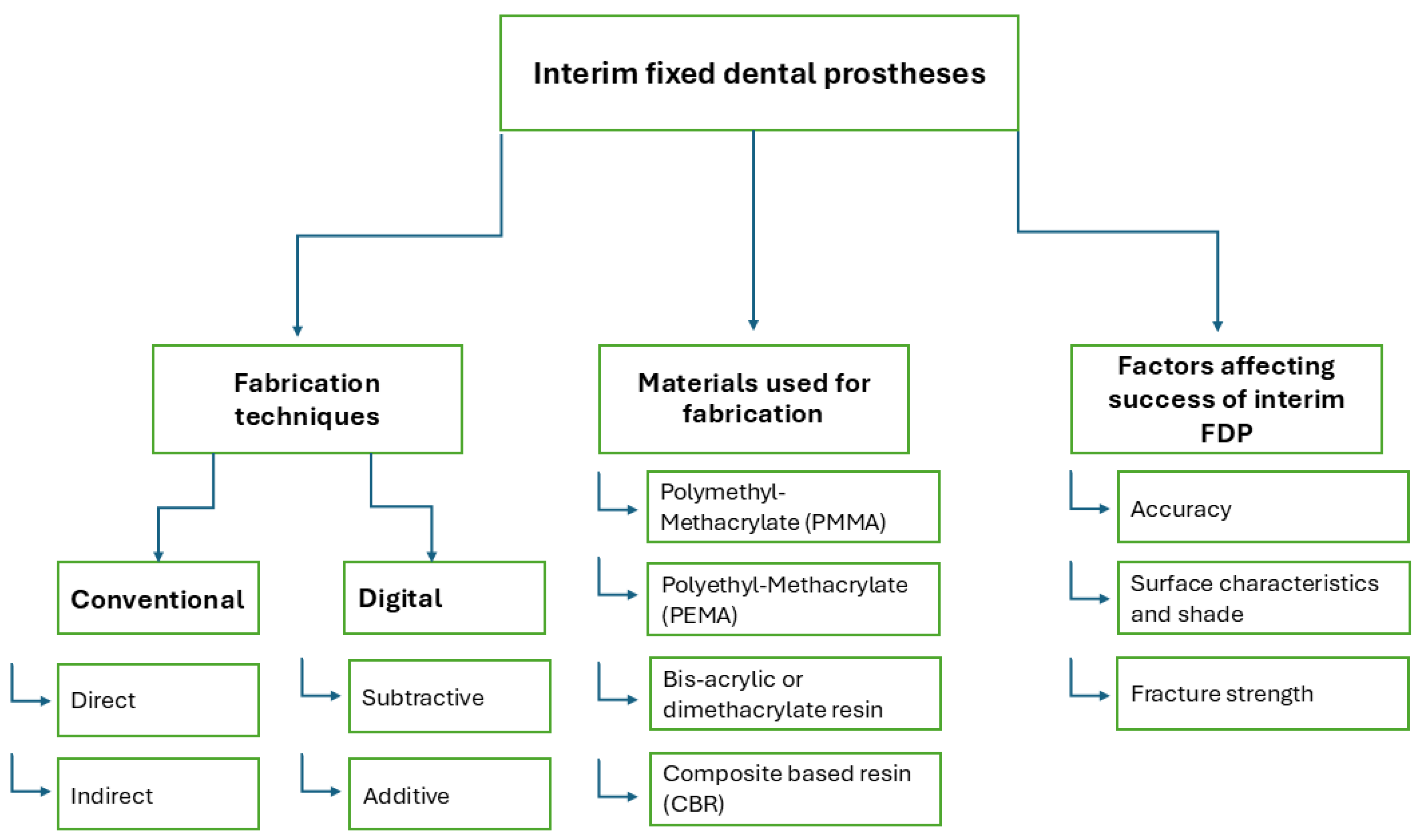

In this review article, we provided a comprehensive evidence-based overview of the current fabrication techniques and the various available materials for interim FDPs. The focus was on the advantages and disadvantages of each technique, with special emphasis on accuracy, aesthetics, and mechanical stability (

Figure 1).

1. Methods of Fabrication of Interim FDPs

The methods of fabrication of interim FDPs could be classified according to fabrication settings into direct chairside and indirect laboratory, and according to fabrication technique into conventional and digital methods. The digital method is further subclassified according to fabrication process into subtractive and additive techniques [

8].

1.1. Conventional Fabrication

1.1.1. Direct (Chair-Side)

In this technique, an index is created using polymeric impression material on the intact teeth prior to preparation. Self-curing acrylic resin (temporary crown and bridge material) is then mixed and placed into the mold, which is seated directly on the prepared abutments in the patient's mouth until the material hardens. Afterwards, the interim prosthesis is checked for defects, followed by finishing and polishing [

7]. In the case of a bridge, an index is made over the waxed-up primary cast. After abutment preparation, the temporary crown and bridge material is loaded into the index and seated over the prepared abutments intraorally [

9]. This technique is straightforward and time-efficient, as it is direct and eliminates the need for laboratory steps [

5]. However, its potential drawbacks include diminished mechanical properties, a rough surface finish, and an improper fit of the FDP, which may be exacerbated by inadequate mixing or the incorporation of air voids [

10].

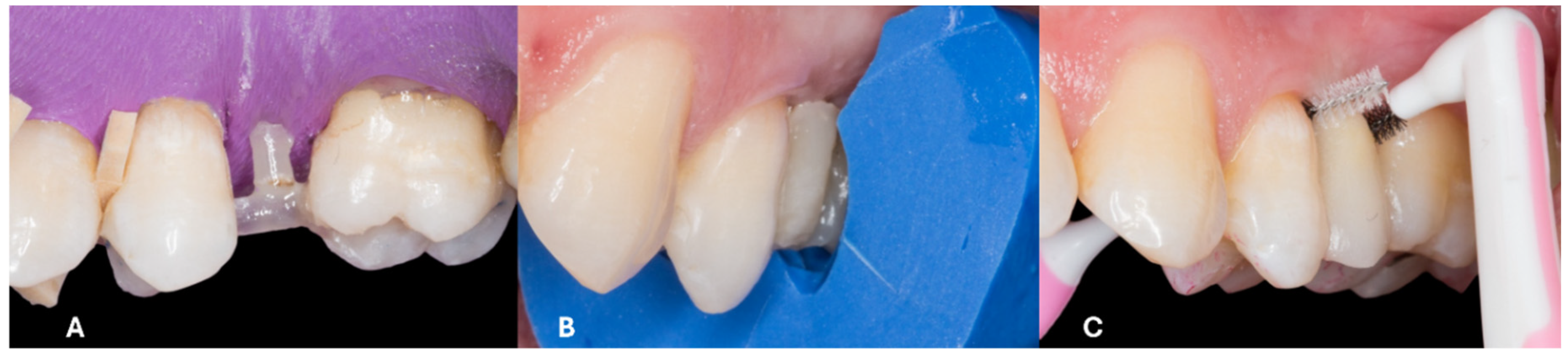

Another approach to direct bridge construction is the fiber-reinforced composite bridge. In this technique, the clinician utilizes fiberglass pins or bands. A fiber pin is positioned horizontally in the edentulous space, parallel to the occlusal or incisal plane. After adjusting the pin length, silane is applied to its surface, and the adjacent abutments undergo surface treatment with etching and bonding agents. The pin is then secured using flowable composite on the abutments, and a vertical reinforcing pin is placed perpendicular to the horizontal pin within the edentulous space. Composite is incrementally applied over the pins to form the pontic, or alternatively, packable composite is shaped into the pontic using a pre-formed index. The bridge is completed with finishing and polishing to refine the fiber-reinforced composite structure [

11,

12] (

Figure 2). When specific case selection criteria are met, this technique can serve as a permanent treatment option for restoring a single missing tooth, as reported by Martínez et al. [

11]. In the study a success rate of 95.2% over a 9-year follow-up period is documented, suggesting it is an effective alternative to a conventional bridge for restoring a non-load bearing tooth. In other cases, this method can function as a transitional phase during implant treatment [

11,

12].

1.1.2. Indirect (Laboratory) Fabrication

In the case of longer service period, a laboratory interim FDP is recommended over the direct one, since it has the advantage of enhanced surface finish, improved surface contours and contacts and reduced intraoral adjustments. Indirect laboratory procedures include fabricating an index and an interim FDP. A laboratory index can be prepared by using a vacuum-formed clear sheet pressed over the designated segment of the primary cast. Then, an auto-polymerizing resin is injected into the mold and placed on the master cast to construct the interim FDP [

13]. Meanwhile, the conventional direct interim FDP is applied immediately following tooth preparation and acts as a provisional solution until the laboratory-fabricated interim FDP is ready for long-term application.

In aesthetic cases, such as those involving veneers, an intraoral mockup is a crucial step prior to initiating tooth preparation. The mockup is created using temporary crown material, either through conventional methods or digital techniques. Conventional mockups are produced using indices crafted over manually waxed primary casts, prepared by an experienced technician. Meanwhile, digital mockups are milled or 3D-printed from digital wax-ups designed with 3D modeling software. Compared to conventional mockups, digitally fabricated mockups offer greater accuracy and closer alignment with the original design [

14].

1.2. Digital Fabrication

1.2.1. Subtractive Technique (Milling)

Computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technology, initially developed for the automotive and aerospace industries, has been successfully adapted for dental applications. A typical in-office dental CAD/CAM system includes an optical scanner, a desktop computer, and a milling unit. The digital workflow begins with an intraoral scanner capturing the prepared tooth, generating a digital impression that is displayed on the computer monitor for restoration design. Once the design of the restoration is finalized, it is transmitted to the milling unit, which fabricates the restoration [

15].

CAD/CAM technology has been implemented in the fabrication of interim FDPs due to its ability to produce restorations of superior quality, regarding physical, aesthetic, and mechanical properties, such as fracture strength, internal fit, and marginal adaptation [

2,

7]. Huettig et al. [

6] conducted a clinical trial and evaluated the longevity of milled fixed-fixed polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) bridges used as long-term temporary FDPs, reporting a success rate of 90.4 %, with 88.3 % of cases free from complications over 16 months. It was concluded that milled PMMA bridges could be a viable option for long-term temporary FDPs.

While CAD/CAM systems produce high-quality interim restorations, certain limitations can arise with the milling technology. Challenges may include restrictions in 3D designing software, difficulties with scanner cameras in accessing distal intraoral areas, image artifacts caused by uncontrolled moisture and saliva, and inaccuracies in milling machine production of fine restoration details [

2]. Additionally, the expertise of the CAD/CAM operator plays a significant role in determining the quality of the final restoration [

2,

16].

1.2.2. Additive Technique (3D Printing)

The 3D printing technique, an additive manufacturing process, begins with a digital file created using CAD modeling software, based again on intra-oral scans or scanned plaster casts. This data enables the production of thin cross-sectional layers, allowing for the creation of complex shapes unattainable with traditional methods. The process involves designing the part in compatible software, generating a file format for the printer, and constructing the product by layering thin sections sequentially. Most 3D printing methods use this layer-by-layer approach, interpreting the design as a series of two-dimensional layers [

17].

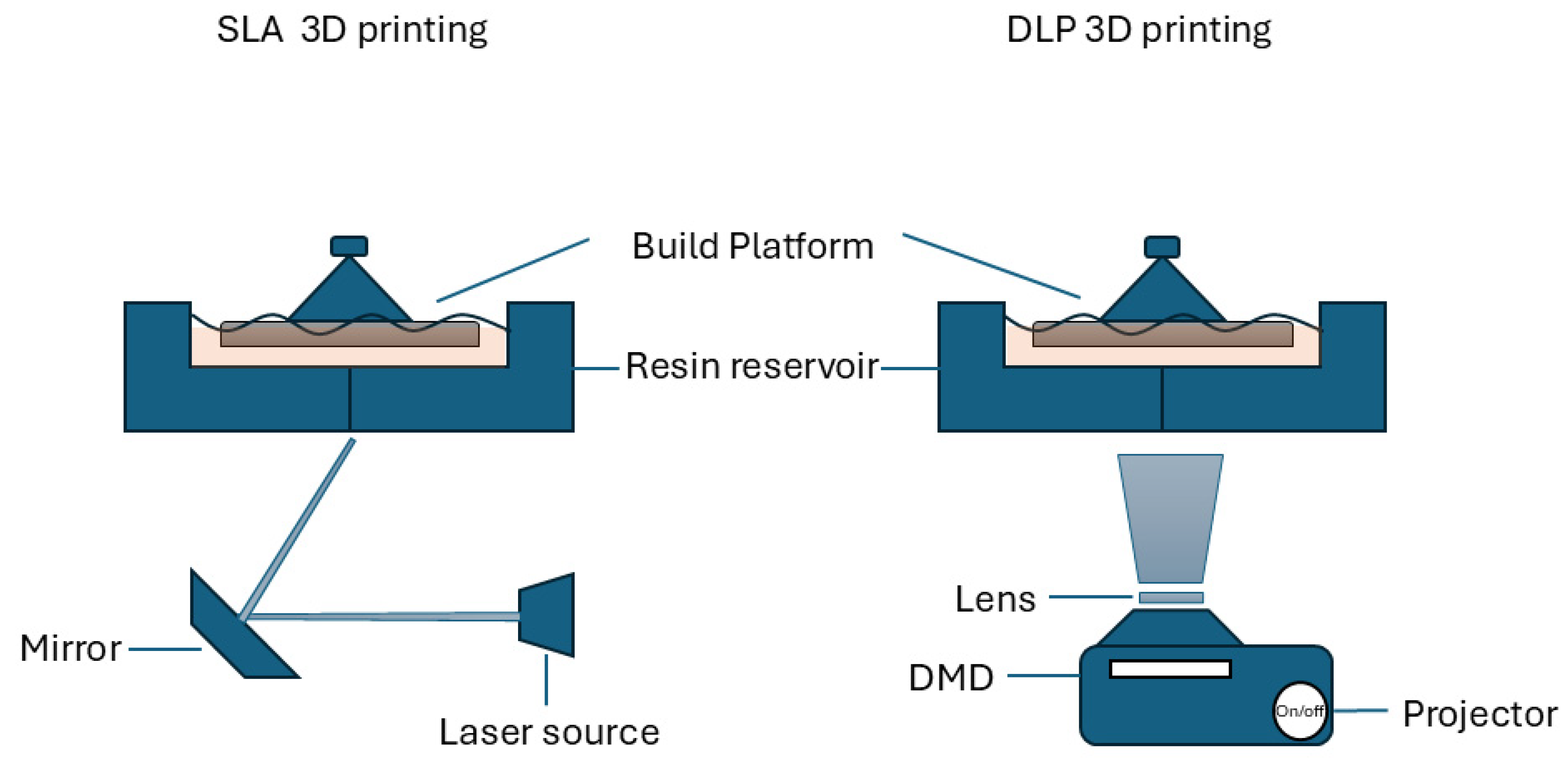

With the development of 3D printing production technology and its recent widespread use in dentistry, the direct comparison between milling and 3D printing in terms of reduced production time, raw material saving, and the ability to produce complex structures has tipped the balance in favor of 3D printing [

18,

19]. Photopolymerization 3D printing is the most widely used technique in dentistry due to its ability to fabricate highly detailed objects with excellent resolution, a fine surface finish, and reduced production time. Both, stereolithography (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP) utilize photopolymerization technology. SLA employs a laser to cure the resin layer by layer, while DLP uses a wider light reflector that solidifies the entire layer of resin on the platform at once (

Figure 3). DLP is faster than SLA. After each layer is polymerized, the platform moves downward to allow the next layer to be cured, continuing this process until the entire object is complete. In both systems, the operator can control the layer thickness [

19,

20,

21].

Several studies [

4,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] employed 3D printing technology in fabricating interim FDP, comparing the 3D printed restorations to traditionally produced restorations. Furthermore, Cuschieri et al. [

16] assessed patient satisfaction with conventional temporary restorations compared to digitally designed and fabricated restorations. Their findings revealed that digital restorations significantly improved satisfaction with the aesthetic outcome compared to the conventional restorations, while the designer's expertise impacted satisfaction with both aesthetic and functional outcomes.

2. Materials Available for Interim FDPs

The most common materials used for direct chairside and indirect interim restorations are: PMMA and Polyethyl Methacrylate (PEMA), Bis-acrylic or dimethacrylate resin and composite based resin (CBR) [

10,

18,

29]. Interim FDP composites are methacrylate-based materials composed of resin such as triethyleneglycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA), 2,2-bis(4-(2-methacryloxy ethoxy) phenyl) propane (Bis-EMA), bisphenol A glycidyl dimethacrylate (Bis-GMA), or urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) [

30]. With the evolution of digital dentistry, milling restorations out of polymerized blanks - industrially prepared under optimum conditions - or using 3D printing and creating an object layer by layer have influenced the overall properties of final restorations, even though same materials are being used [

18,

29]. Berghaus et al. [

30] investigated the leaching of residual unpolymerized monomers from interim restoration materials fabricated using milling, 3D printing, and the direct technique. Regarding the effect of fabrication techniques, the direct technique exhibited the highest percentage of residual monomer leaching, which negatively affects the biological, physical, and mechanical properties of the material. In contrast, both 3D printing and milling showed a higher degree of conversion, with no detectable free monomers observed in the case of milled restorations.

One of the major drawbacks of direct interim restoration fabrication is the polymerization shrinkage that can affect the accuracy and mechanical properties of an interim prosthesis. Modifications such as filler incorporation into direct interim materials have been made to enhance the mechanical properties. The most common fillers used were metal, glass fiber, polyethylene or carbon [

10]. Peñate et al. [

10] compared the marginal fit and fracture strength of glass fiber-reinforced and non-reinforced direct interim FDPs to milled PMMA bridges. In their study they found that glass fiber-reinforced bridges had the least marginal discrepancy, and that fiber reinforcement improved the mechanical properties and influenced the failure mode of the interim bridges.

3. Factors Affecting Success of Interim FDP

3.1. Accuracy of Interim FDP

The accuracy of dental restoration is defined by its internal fit, marginal adaptation, and occlusal accuracy, these play a pivotal role in its clinical performance [

31]. Several factors can influence the accuracy of FDPs, including the fabrication technique, span length, and impression methods utilized [

32]. While in numerous studies [

33,

34,

35,

36] the accuracy of permanent FDPs concerning these factors have been investigated, there is a notable lack of data on the accuracy of interim FDPs.

3.1.1. Marginal Adaptation

Marginal discrepancies in interim fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) can lead to sensitivity in the reduced abutment and periodontal inflammation around the prosthesis. Such discrepancies may also compromise subsequent steps in final FDP fabrication, including margin assessment during the try-in stage and final cementation [

37,

38]. Aldahian et al. [

25] and Alharbi et al. [

4] reported that 3D-printed full-coverage restorations exhibited smaller marginal gaps compared to those produced using milling or conventional methods.

3.1.2. Internal Fit

An inaccurately fitted interim FDP can lead to loss of retention and impaired function [

39,

40]. On several studies [

4,

22,

23,

25] it was concluded that 3D-printed single crowns exhibited superior internal fit and trueness compared to their milled counterparts. Shalaby et al. [

26] stated that even with varying span length bridges, 3D-printed interim FDPs demonstrated higher internal fit accuracy.

3.1.3. Occlusal Surface Accuracy

Giannetti et al. [

24] performed a direct comparison between milled and 3D printed interim crowns regarding trueness of occlusal surface compared to original CAD design. In the study it was found that 3D printed crowns had higher occlusal surface accuracy and required fewer intraoral occlusal adjustments.

3.2. Surface Characteristics and Shade

For cases requiring interim FDPs over extended durations, such as in rehabilitation or implant-supported prostheses, the aesthetic properties of interim materials are primarily influenced by factors like shade availability, color stability, surface finish, and micro-roughness [

25,

28,

41]. According to a recent study the current interim resin materials available for additive manufacturing technique failed to match their conventional composite and acrylic resin counterparts of the same shade regarding the three parameters of color. This makes shade selection and shade matching with adjacent natural teeth a challenging process for additive interim resins [

42,

43]. According to Ellakany et al. [

44], the color stability of interim FDPs is highest in milled interim resin materials, followed by those produced through SLA 3D printing, then DLP 3D printing, with conventional interim resins exhibiting the lowest color stability.

In a study by Yao et al. [

45] it was highlighted that there is impact of surface treatments on the color stability of digitally fabricated interim FDPs. The findings revealed that applying a nano-filled light polymerizing protective agent significantly reduces color change in milled restorations during service. For additively manufactured restorations, both surface polishing and protective coating application were found to effectively minimize color changes.

Surface roughness is another critical consideration. Interim FDPs fabricated using additive techniques exhibit the highest surface roughness, followed by those manufactured using the conventional direct technique, with subtractive technique producing the smoothest surfaces [

3,

25,

28]. Surface finish is further influenced by the filler content and particle size in the resin. Gantz et al. [

41] observed that only materials with nano-sized fillers achieve the smoothest surfaces both before and after polishing.

Along with micro-roughness, porosity and fungal adherence also play a significant role in the performance of interim FDPs regarding pink aesthetics and gingival health as plaque retention can further affect soft tissue health in patients with underlying periodontal conditions and bad oral hygiene. Ribeiro et al. [

46] found that milled restorations exhibit the lowest porosity and fungal adherence, followed by 3D-printed restorations, while conventional materials especially composite resin materials have the highest porosity and susceptibility to fungal adherence. Additionally, Radwan et al. [

47] concluded that 3D-printed interim restorations are unsuitable for extended use due to persistent issues with surface roughness and staining.

3.3. Fracture Strength

Limited data exists on the fracture resistance of interim fixed dental prostheses (FDPs), particularly long-span interim prostheses. Milled interim crowns demonstrate higher fracture resistance compared to 3D-printed crowns. Consequently, Alsarani et al. [

48] recommend avoiding the use of 3D-printed interim crowns with occlusal thicknesses under 1 mm. Efforts to improve the fracture resistance of 3D-printed restorations, such as incorporating micro-fillers like zirconia glass and glass silica, were unsuccessful. Instead, these fillers increased surface roughness, which compromised the aesthetics of the crowns, as noted by Alshamarani et al. [

49]. Studies comparing the fracture resistance of interim crowns fabricated manually, by milling, and through 3D printing consistently found that milled crowns outperformed 3D-printed crowns, with both surpassing manually fabricated crowns in fracture resistance [

8,

50]. However, Abdullah et al. [

51] highlighted that not all milled interim materials are superior to direct materials in terms of fracture resistance.

Three-unit interim FDPs produced using additive and subtractive techniques have also been evaluated. Abad-Coronel et al. [

52] reported that milled three-unit bridges exhibited higher fracture resistance. Contrarily, Falahchai et al. [

53] found that 3D-printed three-unit interim bridges achieved the highest fracture resistance values, which were statistically significant compared to those produced using direct and indirect techniques.

Conclusion

Each technique for fabricating interim FDPs has its own advantages and limitations, and all can be effectively utilized for FDP production. However, digital techniques provide superior quality compared to conventional methods, particularly for long-term use. Additive manufacturing has the potential to completely replace subtractive techniques for interim FDP fabrication in the future, owing to its numerous advantages. Nonetheless, further studies are necessary to evaluate the accuracy and fracture strength of 3D-printed interim FDPs with varying span lengths. Additionally, more research is needed to enhance the aesthetic appearance of 3D-printed interim FDPs.

Clinical Recommendations

- 1-

The conventional fabrication technique for interim FDPs is recommended for cases with short span lengths and when the prosthesis is intended for short-term use.

- 2-

Digital techniques are recommended for fabricating interim FDPs intended for long-term use.

- 3-

Milled interim FDPs are preferred in cases with high aesthetic demands, expected heavy occlusal forces, periodontal diseases, or poor oral hygiene.

- 4-

3D-printed interim FDPs are best suited for cases involving longer span lengths or full-arch rehabilitation due to their precise accuracy compared to milled long-span bridges.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Nour Abdelmohsen: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Data curation. Christoph Bourauel: Writing—review & editing. Tarek Elshazly: Writing—review & editing, Visualization, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This scientific work was supported by a fund from Forschungsgemeinschaft Dental e.V. (Project No. 02/2023).

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies on human or animal subjects.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used the ChatGPT AI tool to improve the readability of the English language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Peng, C.C.; Chung, K.H.; Yau, H.T.; Ramos, V. Assessment of the Internal Fit and Marginal Integrity of Interim Crowns Made by Different Manufacturing Methods.

- Sadighpour, L.; Geramipanah, F.; Falahchai, M.; Tadbiri, H. Marginal adaptation of three-unit interim restorations fabricated by the CAD-CAM systems and the direct method before and after thermocycling. J Clin Exp Dent. 2021, 13, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mârțu, I.; Murariu, A.; Baciu, E.R.; et al. An Interdisciplinary Study Regarding the Characteristics of Dental Resins Used for Temporary Bridges. Medicina (Lithuania). 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.; Alharbi, S.; Cuijpers, V.M.J.I.; Osman, R.B.; Wismeijer, D. Three-dimensional evaluation of marginal and internal fit of 3D-printed interim restorations fabricated on different finish line designs. J Prosthodont Res. 2018, 62, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emetwaly el shazly, M.; Abdelhamid, T.; Atta, M.O. Marginal Integrity of Temporary Bridges Constructed by CAD/CAM, Three Dimentional Printer and Conventional Method. Dental Science Updates. 2023, 4, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huettig, F.; Prutscher, A.; Goldammer, C.; Kreutzer, C.A.; Weber, H. First clinical experiences with CAD/CAM-fabricated PMMA-based fixed dental prostheses as long-term temporaries. Clin Oral Investig. 2016, 20, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.O.; Pollington, S.; Liu, Y. Comparison between direct chairside and digitally fabricated temporary crowns. Dent Mater J 2018, 37, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, O.A.; Mandour, M.H.; Gabal, Z.A. Fracture Resistance of Provisional Crowns Fabricated by Conventional, CAD/CAM, and 3D Printing Techniques. Al-Azhar Dental Journal for Girls. 2022, 9, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Twal, E.Q.H.; Chadwick, R.G. Fibre reinforcement of two temporary composite bridge materials - Effect upon flexural properties. J Dent. 2012, 40, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñate, L.; Basilio, J.; Roig, M.; Mercadé, M. Comparative Study of Interim Materials for Direct Fixed Dental Prostheses and Their Fabrication with CAD/CAM Technique.

- Martínez, M.F.E.; López, S.R.; Fontela, J.V.; García, S.O.; Quevedo, M.M. A new technique for direct fabrication of fiber-reinforced composite bridge: A long-term clinical observation. Dent J (Basel). 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabekmez, D.; Aktas, G. Single anterior tooth replacement with direct fiber-reinforced composite bridges: A report of three cases. Niger J Clin Pract. 2020, 23, 434–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Clark, S.R.; Tantbirojn, D.; Korioth, T.V.P.; Hill, A.E.; Versluis, A. Strength and Stiffness of Interim Materials and Interim Fixed Dental Prostheses When Tested at Different Loading Rates.

- Cattoni, F.; Teté, G.; Calloni, A.M.; Manazza, F.; Gastaldi, G.; Capparè, P. Milled versus moulded mock-ups based on the superimposition of 3D meshes from digital oral impressions: A comparative in vitro study in the aesthetic area. BMC Oral Health. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidowitz, G.; Kotick, P.G. The Use of CAD/CAM in Dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 2011, 55, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuschieri, L.A.; Casha, A.; No-Cortes, J.; Ferreira Lima, J.; Cortes, A.R.G. Patient Satisfaction with Anterior Interim CAD-CAM Rehabilitations Designed by CAD Technician versus Trained Dentist—A Clinical Preliminary Study. Applied Sciences (Switzerland). 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandyal, A.; Chaturvedi, I.; Wazir, I.; Raina, A.; Ul Haq, M.I. 3D printing – A review of processes, materials and applications in industry 4.0. Sustainable Operations and Computers, 2022; 3, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Sayed, M.E.; Shetty, M.; et al. Physical and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Provisional Crowns and Fixed Dental Prosthesis Resins Compared to CAD/CAM Milled and Conventional Provisional Resins: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Polymers (Basel). 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, N.; Wesemann, C.; Spies, B.C.; Beuer, F.; Bumann, A. Dimensional accuracy of extrusion- and photopolymerization-based 3D printers: In vitro study comparing printed casts. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2021, 125, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias Resende, C.C.; Quirino Barbosa, T.A.; Moura, G.F.; et al. Cost and effectiveness of 3-dimensionally printed model using three different printing layer parameters and two resins. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2023, 129, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, C.X.; Xu, X.; et al. A Review of 3D Printing in Dentistry: Technologies, Affecting Factors, and Applications. Scanning. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakinuma, H.; Izumita, K.; Yoda, N.; Egusa, H.; Sasaki, K. Comparison of the accuracy of resin-composite crowns fabricated by three-dimensional printing and milling methods. Dent Mater J. 2022, 41, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, K.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, K.B. Comparison of intaglio surface trueness of interim dental crowns fabricated with sla 3d printing, dlp 3d printing, and milling technologies. Healthcare (Switzerland). 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, L.; Apponi, R.; Mordini, L.; Presti, S.; Breschi, L.; Mintrone, F. The occlusal precision of milled versus printed provisional crowns. J Dent. 2022, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahian, N.; Khan, R.; Mustafa, M.; Vohra, F.; Alrahlah, A. Influence of Conventional, CAD-CAM, and 3D Printing Fabrication Techniques on the Marginal Integrity and Surface Roughness and Wear of Interim Crowns. Published online 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, M.; Wahba, M.; Mohamed, A. Assessment of the Effect of two Different Digital Fabrication Techniques on Marginal and Internal Fit of Interim Fixed Dental Prothesis. Future Dental Journal. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, A.; Reymus, M.; Hickel, R.; Kunzelmann, K.H. Three-body wear of 3D printed temporary materials. Dental Materials. 2019, 35, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, A.S.; Tulbah, H.I.; Binhasan, M.; et al. Surface properties of polymer resins fabricated with subtractive and additive manufacturing techniques. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaokutan, I.; Sayin, G.; Kara, O. In vitro study of fracture strength of provisional crown materials. Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics. 2015, 7, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghaus, E.; Klocke, T.; Maletz, R.; Petersen, S. Degree of conversion and residual monomer elution of 3D-printed, milled and self-cured resin-based composite materials for temporary dental crowns and bridges. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2023, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami-Lahiji, M.; Falahchai, M.; Habibi Arbastan, A.; Arbastan, H. Review Paper: Different Ways to Measure Marginal Fit and Internal Adaptation of Restorations in Dentistry Citation. Vol 12.; 2023.

- Bousnaki, M.; Chatziparaskeva, M.; Bakopoulou, A.; Pissiotis, A.; Koidis, P. Variables affecting the fit of zirconia fixed partial dentures: A systematic review. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2020, 123, 686–692.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, C.; Groesser, J.; Stadelmann, M.; Schweiger, J.; Erdelt, K.; Beuer, F. Full-arch prostheses from translucent zirconia: Accuracy of fit. Dental Materials. 2014, 30, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçin, E.T.; Barıs¸güncü, M.; Barıs¸güncü, B.; Aktas¸, G, Dds, A.; Aslan, Y. Effect of Manufacturing Techniques on the Marginal and Internal Fit of Cobalt-Chromium Implant-Supported Multiunit Frameworks.

- Kim, W.K.; Kim, S. Effect of Number of Pontics and Impression Technique on the Accuracy of Four-Unit Monolithic Zirconia Fixed Dental Prostheses.

- Kim, M.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Shim, J.S.; Kim, S. Effect of the number of splinted abutments on the accuracy of zirconia copings. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2018, 120, e1–e790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emetwaly el shazly, M.; Abdelhamid, T.; Atta, M.O. Marginal Integrity of Temporary Bridges Constructed by CAD/CAM, Three Dimentional Printer and Conventional Method. Dental Science Updates. 2023, 4, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, M.; Cesar, P.F.; Griggs, J.A.; Della Bona, Á. Adaptation of all-ceramic fixed partial dentures. Dental Materials. 2011, 27, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, K.; Lee, S.; Kang, S.H.; et al. A comparison study of marginal and internal fit assessment methods for fixed dental prostheses. J Clin Med. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, M.A.; Blunt, L.; Bills, P.; Tawfik, A.; Radawn, M. Micro-CT Analysis of Marginal and Internal Fit of Milled and Pressed Polyetheretherketone Single Crowns.

- Gantz, L.; Fauxpoint, G.; Arntz, Y.; Pelletier, H.; Etienne, O. In Vitro Comparison of the Surface Roughness of Polymethyl Methacrylate and Bis-Acrylic Resins for Interim Restorations before and after Polishing.

- Alikhasi, M.; Jafarian, Z. Additional Manufactured Interim Restorations: a Review on the Literature. Journal of Dentistry (Iran). 2022, 23, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- color dimensions of AM interim restorative material.

- Ellakany, P.; Fouda, S.M.; AlGhamdi, M.A.; Aly, N.M. Comparison of the color stability and surface roughness of 3-unit provisional fixed partial dentures fabricated by milling, conventional and different 3D printing fabrication techniques. J Dent. 2023, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- color stability of interim fdp.

- Ribeiro, A.K.C.; de Freitas, R.F.C.P.; de Carvalho, I.H.G.; et al. Flexural strength, surface roughness, micro-CT analysis, and microbiological adhesion of a 3D-printed temporary crown material. Clin Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2207–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, H.; Elnaggar, G.; deen IS El. Surface roughness and color stability of 3D printed temporary crown material in different oral media (In vitro study). International Journal of Applied Dental Sciences. 2021, 7, 327–334. [CrossRef]

- Alsarani, M.M. Influence of aging process and restoration thickness on the fracture resistance of provisional crowns: A comparative study. Saudi Dental Journal. 2023, 35, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, A.; Alhotan, A.; Owais, A.; Ellakwa, A. The Clinical Potential of 3D-Printed Crowns Reinforced with Zirconia and Glass Silica Microfillers. J Funct Biomater. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Sandmair, M.; Alevizakos, V. ; See C von. The fracture resistance of 3D-printed versus milled provisional crowns: An in vitro study. PLoS One, 2023; 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.O.; Tsitrou, E.A.; Pollington, S. Comparative in vitro evaluation of CAD/CAM vs conventional provisional crowns. Journal of Applied Oral Science. 2016, 24, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Coronel, C.; Carrera, E.; Córdova, N.M.; Fajardo, J.I.; Aliaga, P. Comparative analysis of fracture resistance between cad/cam materials for interim fixed prosthesis. Materials. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahchai, M.; Rahimabadi, S.; Khabazkar, G.; Babaee Hemmati, Y.; Neshandar Asli, H. Marginal and internal fit and fracture resistance of three-unit provisional restorations fabricated by additive, subtractive, and conventional methods. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2022, 8, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).