Introduction

Organophosphate poisoning (OPP) remains a major global public health issue, particularly in agricultural regions [

1]. Organophosphate chemicals exert their toxic effects by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme essential for breaking down acetylcholine [

2]. This inhibition leads to excessive accumulation of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft, resulting in prolonged stimulation of the cholinergic system and triggering acute cholinergic toxicity. Acute cholinergic toxicity presents with three distinct categories of symptoms: muscarinic effects (excessive salivation, tearing, frequent urination, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and vomiting), nicotinic effects (muscle fasciculations, weakness, and respiratory distress), and central nervous system symptoms (ranging from confusion and agitation to seizures and loss of consciousness) [

3].

The severity of clinical manifestations depends on the dose of exposure and individual susceptibility [

4]. Early identification and appropriate management of organophosphate toxicity are crucial for reducing complications and mortality [

5]. Diagnosis of acute cholinergic syndrome in organophosphate poisoning is based on clinical history, symptoms like salivation, bradycardia, and muscle fasciculations, and confirmation through low serum cholinesterase levels [

1].

Treatment includes rapid decontamination, atropine to counteract muscarinic effects, and pralidoxime (2-PAM) to restore acetylcholinesterase function. Mechanical ventilation may be required for respiratory failure, while benzodiazepines help manage seizures or agitation. Continuous monitoring of vitals and cholinesterase levels is essential for guiding treatment [

4]. This case report discusses the clinical presentation, diagnostic techniques, and treatment strategies for a patient suffering from acute cholinergic toxicity due to organophosphate poisoning. It underscores the importance of prompt medical intervention and highlights the critical role of healthcare professionals in recognizing and managing this life-threatening condition.

Case Presentation

A 45-year-old male plumber was admitted to the emergency department four hours after ingesting an unknown amount of 50% emulsifiable diazinon concentrate. He presented with excessive sweating, salivation, and tearing. The patient had attempted suicide following a quarrel with his father over land inheritance. Before ingesting the poison, he told his father, “You are selfish and cruel. I wish you the best life on earth, and you will get your price in heaven. You will never see me again today. If you can, don’t come to my burnt place. Upon arrival at the hospital, the patient underwent immediate decontamination, including the removal of contaminated clothing and thorough skin washing. His airway, breathing, and circulation were stabilized, with respiratory support and secretion management to prevent further deterioration. Intravenous atropine (0.02 mg/kg/hr) was administered promptly in the emergency department. Four hours later, due to worsening symptoms, he was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for continued monitoring and treatment.

The patient had no known history of chronic illnesses, prior poisonings, or underlying medical conditions. He denied any drug allergies or previous hospitalizations related to toxic exposures. He lived in an urban area with a crowded and poorly ventilated home. His family history was unremarkable, with no reported genetic disorders or prior pesticide-related incidents. He was a non-smoker, did not consume alcohol, and had no history of substance abuse. Upon ICU admission, the patient was in severe distress. His vital signs indicated hypotension (95/67 mmHg), tachycardia (109 beats/min), and tachypnea (25 breaths/min), with a normal body temperature of 37.1°C. Neurological examination revealed fluctuating consciousness, muscle tremors, increased muscle tone, and spasms in the upper limbs. His pupils were constricted (miosis). Respiratory examination showed wheezing, increased work of breathing, and decreased breath sounds, indicating respiratory compromise. Cardiovascular examination revealed tachycardia but no murmurs. Gastrointestinal examination noted hyperactive bowel sounds and excessive secretions. Skin examination confirmed profuse sweating. His Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 10/15 (E3M4V3), reflecting moderate loss of consciousness.

Laboratory results showed elevated liver enzymes, with an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 71 U/L and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 94 U/L, while alkaline phosphatase remained normal. Mild leukocytosis was present (white blood cell count: 16.9 × 10³/mm³), but kidney function was normal. Arterial blood gas analysis indicated respiratory acidosis with a pH of 7.06, low bicarbonate (20.1 mmol/L), elevated partial pressure of carbon dioxide (9.8 kPa), and a partial pressure of oxygen of 14.1 kPa. Serum electrolytes revealed hypokalemia (2.54 mmol/L), and serum cholinesterase activity was markedly reduced (2,370 U/L). Biochemical tests showed elevated blood glucose (15 mmol/L), creatine kinase (10.76 µkat/L), and lactate levels (3.4 mmol/L). Urinalysis was positive for diazinon metabolites. A chest X-ray showed no signs of pulmonary edema or lung abnormalities. A brain CT scan ruled out intracranial causes for the altered mental status. Electroencephalography (EEG) displayed abnormal slow delta waves, primarily in the frontal and frontotemporal regions. A diagnosis of acute organophosphate poisoning leading to a cholinergic crisis was confirmed based on clinical symptoms, exposure history, laboratory findings, and significantly reduced serum cholinesterase levels. The patient was also found to be moderately dehydrated, which was managed with intravenous normal saline (20 mL/kg) over the first four hours.

Treatment included intravenous atropine to counteract muscarinic effects and pralidoxime to reactivate acetylcholinesterase and alleviate nicotinic symptoms. A continuous infusion of pralidoxime was initiated at 30 mg/kg for the first 12 hours, followed by a maintenance infusion of 10 mg/kg for another 12 hours. Atropine infusion was started at 0.02 mg/kg/hr for the first four hours and continued at the same rate for an additional four hours. Over the next three days, atropine was administered at a reduced dose for eight hours per day before being tapered off. The patient received a total of 1,770 mg of pralidoxime over the first 12 hours, along with 9.44 mg of atropine in the first eight hours and 84.96 mg over the next three days. Atropine was gradually reduced as symptoms such as bradycardia, hypersecretion, and bronchospasm improved.

Over the next 48 hours, the patient showed steady improvement, with a reduction in cholinergic symptoms and stabilization of vital signs. By the fourth day in the ICU, he was able to breathe independently, and his level of consciousness improved. He was discharged on day seven with guidelines for ongoing monitoring of potential delayed neurotoxic effects, a known complication of severe organophosphate poisoning. A monthly follow-up was scheduled to assess recovery and screen for long-term complications such as delayed neuropathy or cognitive impairments.

Discussion

Organophosphate compounds are widely used as pesticides and insecticides [

6]. Acute cholinergic syndrome following organophosphate poisoning is characterized by a range of symptoms resulting from the overstimulation of cholinergic receptors due to the accumulation of acetylcholine [

7]. This syndrome can be categorized based on the predominant type of receptors affected. Muscarinic symptoms arise from the stimulation of muscarinic receptors and include excessive salivation (sialorrhea), increased tear production (lacrimation), frequent urination (urinary incontinence), increased gastrointestinal motility leading to diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps. Other muscarinic symptoms include miosis (constricted pupils), bradycardia (slow heart rate), and bronchoconstriction, which can cause difficulty breathing due to airway constriction [

8].

Nicotinic symptoms result from the stimulation of nicotinic receptors at the neuromuscular junction [

9]. These include muscle twitching (fasciculations), progressive muscle weakness, especially of the respiratory muscles, elevated blood pressure (hypertension) due to sympathetic activation, and increased heart rate (tachycardia), which may sometimes occur as a compensatory mechanism. Central nervous system symptoms may also occur in organophosphate poisoning, leading to altered mental status (confusion), seizures (convulsions) due to central nervous system overstimulation, and, in severe cases, coma (reduced level of consciousness) [

10]. The clinical manifestations in the new case report align with findings in existing literature, which consistently describe muscarinic symptoms (such as salivation, lacrimation, urination, diarrhea, gastrointestinal distress, bradycardia, and bronchoconstriction) and nicotinic symptoms (including muscle weakness, hypertension, and tachycardia) [

4]. However, in this case report, central nervous system involvement—such as anxiety, confusion, and seizures—was not observed, despite being documented in previous studies.

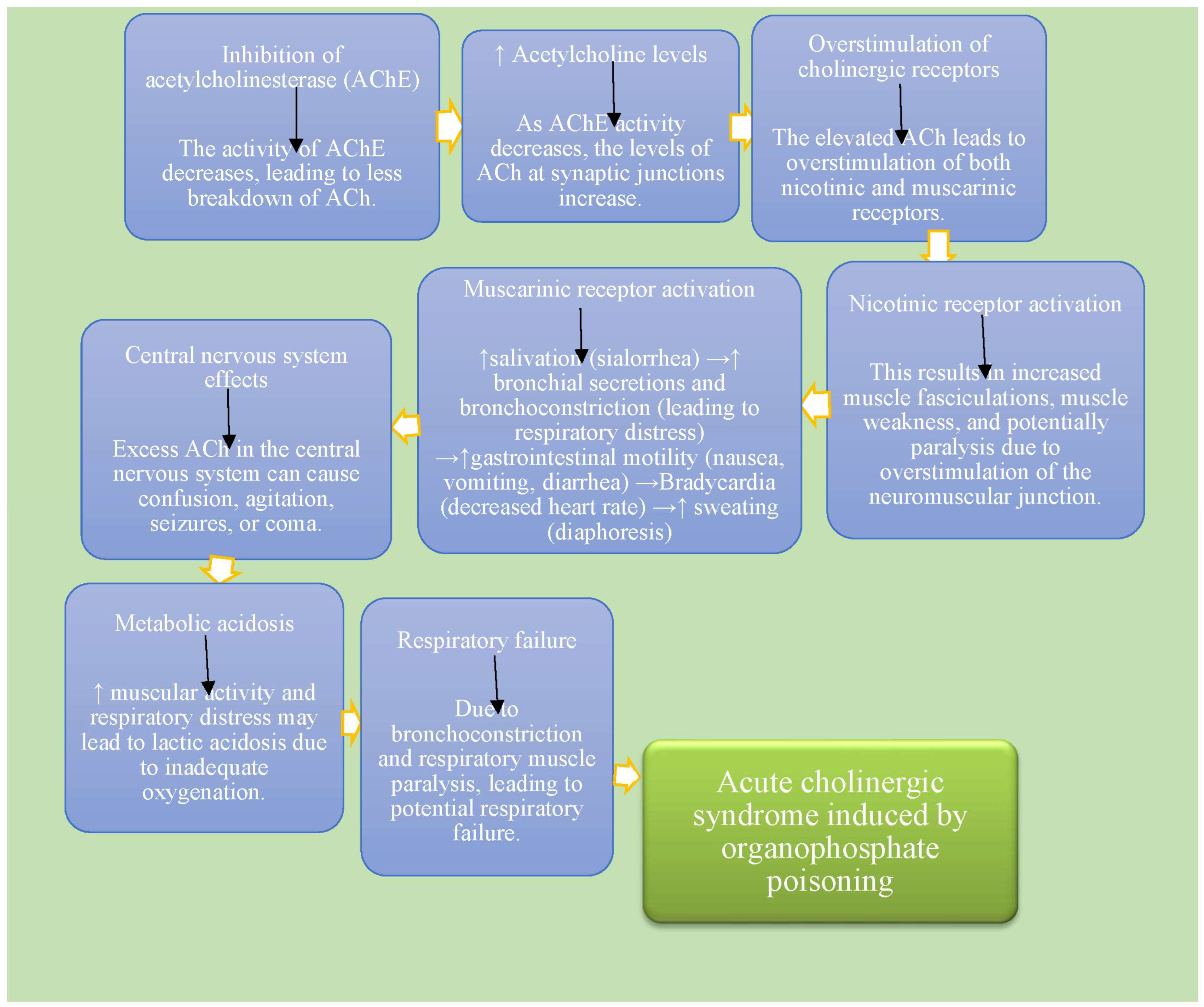

Signs and symptoms of organophosphate poisoning typically manifest as respiratory distress due to bronchoconstriction and respiratory muscle paralysis, hypersalivation and sweating from increased secretory activity, miosis (constricted pupils) due to parasympathetic activation, and cyanosis resulting from respiratory failure or severe hypoxia. The pathophysiology of organophosphate poisoning is characterized by the irreversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), leading to the accumulation of acetylcholine (ACh) at synapses [

11]. This buildup causes continuous stimulation of both muscarinic and nicotinic receptors, disrupting neuromuscular transmission and resulting in muscle paralysis and respiratory failure. The ensuing cholinergic crisis reflects the overstimulation of the autonomic and central nervous systems [

12] (

Figure 1). The findings in the recent case report align with established literature, confirming the irreversible inhibition of AChE by organophosphates and the consequent increase in ACh levels.

The diagnosis of organophosphate poisoning is primarily clinical, supported by a history of exposure to pesticides or insecticides, the assessment of characteristic signs and symptoms, and laboratory tests that measure plasma or red blood cell AChE activity, which is typically decreased in cases of poisoning [

13]. Toxicological screening may also be performed to confirm the presence of organophosphates, aiding in a definitive diagnosis. The diagnostic approach in the new case report mirrors recommendations from existing literature, which emphasizes a combination of clinical assessment and laboratory testing [

14]. Management of organophosphate poisoning includes several critical steps. Decontamination involves removing contaminated clothing and washing the skin to prevent further absorption. Supportive care is essential, including ensuring airway protection and providing supplemental oxygen as needed. Antidote administration is crucial, with atropine given to counteract muscarinic effects and pralidoxime (2-PAM) administered to reactivate AChE if treatment is initiated early enough [

15]. Monitoring of respiratory function, cardiac status, and neurologic function is vital throughout the management process. The management strategies outlined in the new case report, including decontamination, supportive care, and the use of atropine and pralidoxime, are consistent with recommendations in the literature.

The prognosis of organophosphate poisoning depends on several factors, including the severity of exposure, the timeliness of treatment, and the presence of complications. High-dose exposures typically lead to worse outcomes, while early recognition and prompt management significantly improve prognosis [

16]. The prognosis discussed in the new case report is in line with existing literature, which highlights the influence of exposure severity and treatment timeliness on outcomes. In this case report, the patient recovered from the condition promptly without any cardiac or neurological complications.

The existing case report of organophosphate poisoning typically presents with cholinergic symptoms like miosis, bradycardia, muscle twitching, and respiratory distress. Diagnosis is confirmed through clinical signs, cholinesterase level testing, and a history of exposure. Treatment usually involves atropine to counteract muscarinic effects, pralidoxime to regenerate acetylcholinesterase, and supportive care. Outcomes can vary, with recovery in many cases, but there is potential for respiratory failure or neurological sequelae. In comparison, the new case report may highlight similar clinical manifestations but could offer refined diagnostic methods or alternative treatments. Treatment protocols may be updated, and outcomes could provide insights into recovery timelines or complications not typically observed in earlier cases (

Table 1).

Strengths and Limitations

This case highlights the classic pathophysiology of organophosphate poisoning, reinforcing the role of acetylcholinesterase inhibition and cholinergic overstimulation in acute toxicity. It emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis and treatment with atropine and pralidoxime, which are critical for reducing morbidity and mortality. As a single-case report, findings may not be generalizable to all patients with organophosphate poisoning. The long-term effects and recovery patterns are not extensively discussed. Additionally, variability in individual responses to treatment and potential confounding factors (such as co-ingestions) are not addressed.

Conclusions

Organophosphate poisoning remains a life-threatening medical emergency requiring rapid diagnosis, antidote administration, and respiratory support. Early intervention significantly improves survival, but prolonged monitoring is essential due to the risk of delayed complications. This particular case highlights the presentation and management of acute cholinergic syndrome resulting from organophosphate exposure, reinforcing the necessity for immediate medical response and the possibility of complete recovery through appropriate treatment. Healthcare providers must recognize early cholinergic symptoms and initiate prompt atropine and pralidoxime therapy to prevent respiratory failure and other severe complications. Continuous monitoring is crucial for detecting delayed neuromuscular dysfunction and optimizing patient outcomes.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval

Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from a patient for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

Further detail about the report can be made available by request.

References

- Fu H, Tan P, Wang R, et al. Advances in organophosphorus pesticides pollution: Current status and challenges in ecotoxicological, sustainable agriculture, and degradation strategies. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2022 Feb 15; 424:127494. [CrossRef]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Figueiredo TH, de Araujo Furtado M, et al. Mechanisms of organophosphate toxicity and the role of acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Toxics. 2023 Oct 18;11(10):866. [CrossRef]

- Arany S, Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Caprio TV, et al. Anticholinergic medication: Related dry mouth and effects on the salivary glands. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology. 2021 Dec 1;132(6):662-70. [CrossRef]

- Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. What is a host? Attributes of individual susceptibility. Infection and immunity. 2018 Feb;86(2):10-128. [CrossRef]

- Alozi M, Rawas-Qalaji M. Treating organophosphates poisoning: management challenges and potential solutions. Critical reviews in toxicology. 2020 Oct 20;50(9):764-79. [CrossRef]

- Sidhu GK, Singh S, Kumar V, et al. Toxicity, monitoring and biodegradation of organophosphate pesticides: a review. Critical reviews in environmental science and technology. 2019 Jul 3;49(13):1135-87. [CrossRef]

- Pulkrabkova L, Svobodova B, Konecny J, et al. Neurotoxicity evoked by organophosphates and available countermeasures. Archives of toxicology. 2023 Jan;97(1):39-72. [CrossRef]

- Pappano, AJ. Cholinoceptor-activating & cholinesterase-inhibiting drugs. Basic & clinical pharmacology. McGraw Hill Professional, New York, NY. 2018:107-23.

- Shayani K, Mina B, Walczyszyn M, et al. Noninvasive Mechanical Ventilation After Chemical Disasters. InNoninvasive Mechanical Ventilation in High-Risk Infections, Mass Casualty and Pandemics 2023 Jul 5 (pp. 25-38). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo TH, Apland JP, Braga MF, et al. Acute and long-term consequences of exposure to organophosphate nerve agents in humans. Epilepsia. 2018 Oct; 59:92-9. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan A, Jindal T. Toxicology of organophosphate poisoning. Springer International Publishing; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ganie SY, Javaid D, Hajam YA, et al. Mechanisms and treatment strategies of organophosphate pesticide induced neurotoxicity in humans: A critical appraisal. Toxicology. 2022 Apr 30; 472:153181. [CrossRef]

- Xu B, Zeng W, Chen F, et al. Clinical characteristics and early prediction of mortality risk in patients with acute organophosphate poisoning-induced shock. Frontiers in medicine. 2023 Jan 11; 9:990934. [CrossRef]

- Kumaran A, Vashishth R, Singh S, et al. Biosensors for detection of organophosphate pesticides: Current technologies and future directives. Microchemical Journal. 2022 Jul 1; 178:107420. [CrossRef]

- Rawas-Qalaji M, Thu HE, Hussain Z. Potential alternative treatments and routes of administrations: nerve agents poisoning. InSensing of Deadly Toxic Chemical Warfare Agents, Nerve Agent Simulants, and their Toxicological Aspects 2023 Jan 1 (pp. 539-568). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Pappano, AJ. Cholinoceptor-activating & cholinesterase-inhibiting drugs. Basic & clinical pharmacology. McGraw Hill Professional, New York, NY. 2018:107-23.

- Petreski T, Kit B, Strnad M, et al. Cholinergic syndrome: a case report of acute organophosphate and carbamate poisoning. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. 2020 Jun 29;71(2):163. [CrossRef]

- Bereda, G. Poisoning by organophosphate pesticides: a case report. Cureus. 2022 Oct 2;14(10). [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai MD, Singh DL, Chalise BS, et al. A case report and overview of organophosphate poisoning. Katmandu University Medical Journal. 2006;4(1):13.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).