1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of digital entertainment, video game addiction among young individuals has become a growing public health concern [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Excessive gaming has been associated with various physical and psychological issues, including disrupted sleep patterns, reduced physical activity, and cognitive impairments. In response to this issue, several studies have attempted to establish objective metrics for quantifying gaming addiction. Previous research has proposed various physiological and psychological assessment tools, including surveys, neuroimaging, and autonomic nervous system (ANS) analysis using heart rate variability (HRV) [

14,

15]. While these studies provide valuable insights into the characteristics of gaming addiction, they primarily focus on evaluating the severity of addiction rather than differentiating addicted individuals from non-addicted ones [

15].

A key challenge in this research area is the development of a reliable classification method that can distinguish individuals with gaming addiction from healthy controls based on physiological signals. However, an important limitation of existing methods is their inability to differentiate between gaming time and resting time based solely on physiological data. This distinction is crucial, as the physiological effects of gaming may vary depending on the context, and an accurate classification model should focus on differentiating individuals rather than just identifying gaming sessions.

To address this gap, this study investigates the feasibility of machine learning-based classification of electrocardiogram (ECG) signals to distinguish between individuals with gaming addiction and healthy controls. We extracted RR interval time series and HRV indices from ECG signals and applied multiple machine learning classifiers. By evaluating model performance, we aimed to identify the most effective classification approach. Unlike previous studies that focused on detecting gaming sessions, this research introduces a novel perspective by classifying individuals based on their physiological responses rather than merely identifying gaming time. Through this approach, we contribute to the development of an objective, data-driven method for detecting gaming addiction, which could aid in early diagnosis and intervention. By leveraging machine learning techniques, this study offers a new framework for analyzing physiological signals and understanding the autonomic nervous system's response to gaming addiction. Furthermore, this study hypothesizes that gamers will show different HRV patterns compared to non-gamers, even in the same sitting position, because the biological response of excitement during gaming is associated with changes in autonomic nervous system activity. By analyzing short-term and long-term fluctuations in HRV indices, we aim to capture subtle autonomic dysfunction that may be predictive of whether or not someone is playing a game. Previous studies have selected subjects who have been diagnosed with game addiction, but the cardiac autonomic response during game play in people before they become addicted is unknown. By incorporating machine learning techniques, we aim to develop a predictive model that can be generalized to individual characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study recruited 13 healthy participants (mean age: 31.9 ± 12 years old, 1 female) with no known underlying medical conditions. Participants were divided into two groups: the gaming group (n = 6) and the seated rest control group (n = 7). The gaming group consisted of individuals who regularly played video games, whereas the control group included participants who did not engage in gaming during the experiment. All participants provided written informed consent before the experiment, following ethical guidelines approved by the Fukuyama University Ethics Committee (No.2024-H-52, Approved 10/11/2024). The study strictly adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for human research. Participants were informed of the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequences.

2.2. Experimental Protocol

The ECG recordings were conducted in a seated posture to ensure consistency in physiological measurements. The total measurement duration varied between 40 minutes and 120 minutes per participant, depending on individual engagement and tolerance levels. The experiment was conducted under two distinct conditions:

Gameplay Condition: Participants in the gaming group played an interactive video game. The choice of the game was unrestricted, allowing players to engage with a game of their preference to maintain natural gaming behavior.

Seated Rest Condition: The control group remained seated in a relaxed state without engaging in any external stimuli, such as reading, watching videos, or using smartphones.

Both conditions were conducted in a quiet environment with controlled room temperature (24 ± 2℃) to minimize external influences on heart rate variability (HRV). The seated posture was chosen to avoid additional physiological variations caused by movement or changes in body position. To ensure the reliability of physiological measurements and the validity of group comparisons, strict exclusion criteria were applied. Participants with any history of cardiovascular disease, autonomic dysfunction, or neurological disorders were excluded, as these conditions could significantly influence heart rate variability (HRV) and confound the results. Additionally, individuals currently taking medications that affect autonomic function, such as beta-blockers or antidepressants, were not included in the study. Given that this research focuses on physiological differences between individuals with and without gaming addiction, only healthy participants without pre-existing medical conditions were recruited. Furthermore, individuals with irregular sleep patterns, excessive caffeine or alcohol consumption prior to the experiment, or high levels of daily physical activity were excluded to minimize confounding factors. These strict criteria ensured that the observed physiological differences were attributable to gaming addiction rather than other underlying health conditions.

2.3. ECG Data Collection and HRV Analysis

ECG signals were continuously recorded using the Checkme Pro device (San-ei Medisys, Japan). The Checkme Pro was selected for its compact design, high-quality signal acquisition, and ease of use in controlled experiments. The ECG signal was measured using a NASA-guided lead placement, which records the potential difference between the upper and lower sternum. This placement was chosen because it effectively minimizes electromyographic (EMG) noise while providing excellent P-wave visibility, enhancing the accuracy of RR interval detection. The ECG signals were sampled at a frequency of 250 Hz, ensuring high temporal resolution for HRV analysis. The Checkme Pro device was connected to a PC via a USB cable, and the recorded ECG data were transferred to a computer using Checkme Viewer software (San-ei Medisys, Japan,

https://www.checkme.jp/pcviewer/). The exported ECG data were saved in CSV format for further processing and analysis.

From the raw ECG signals, RR interval time series were extracted and resampled at 2 Hz to standardize the data for HRV analysis. The study focused on key heart rate variability (HRV) indices, which were computed using fast Fourier transform (FFT) to extract frequency-domain features. Power spectrum analysis methods include Lomb-Scargle period analysis and AR model (Yule-Walker equation and Akaike's Information Criterion). Lomb-Scargle period analysis can be applied to irregularly sampled data and is suitable for HRV analysis obtained from wearable devices. AR model has high frequency resolution and can be applied to small data sets, making it suitable for long-term HRV analysis and autonomic nervous balance evaluation. In this study, we selected the fast Fourier transform method, which is easy to apply to short-term data because the sampling time interval is constant.

Mean RR interval (ms): The average duration between consecutive R-peaks, representing overall heart rate trends.

SDRR (ms): The standard deviation of RR intervals, reflecting overall HRV magnitude.

VLF (very low-frequency power (ln,ms2), 0.003–0.04 Hz): Associated with long-term autonomic regulation and possibly thermoregulatory mechanisms.

LF (low-frequency power (ln,ms2), 0.04–0.15 Hz): Represents a combination of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity.

HF (high-frequency power (ln,ms2), 0.15–0.40 Hz): Primarily reflects parasympathetic (vagal) activity and respiratory influences.

LF/HF ratio: An indicator of sympathovagal balance, with higher values suggesting increased sympathetic dominance.

HF peak frequency (Hz): The dominant frequency within the HF band, associated with respiratory modulation of heart rate.

HRV indices were calculated for both 5-minute and 10-minute segments of ECG data to analyze short-term autonomic fluctuations.

2.4. Machine Learning Classification

To classify participants based on their physiological responses, six machine learning models were applied to the HRV feature set:

Logistic Regression (LGR): A linear classification model used for binary classification, providing probability estimates.

Random Forest (RF): An ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees and averages predictions.

XGBoost (XGB): A gradient boosting algorithm optimized for structured data and classification tasks.

One-Class SVM (OCS): A support vector machine-based method for detecting outliers or separating a single class from others.

Isolation Forest (ILF): An unsupervised learning algorithm designed for anomaly detection based on tree structures.

Local Outlier Factor (LOF): A density-based anomaly detection algorithm that compares local densities of data points.

To ensure robust model performance, hyper parameter tuning was conducted for LGR, RF, and XGB using a grid search method, optimizing for classification accuracy. For OCS, ILF, and LOF, default parameters were used due to their inherent sensitivity to data structure.

2.5. Dataset Preparation and Model Evaluation

To balance the dataset, equal numbers of 5-minute and 10-minute data segments were extracted from both the gaming and control groups (

Table 1.).

The dataset was then divided using k-fold cross-validation (k = 3, 4, 5) to assess classification performance across multiple splits. This method ensured robust evaluation while minimizing overfitting. The following performance metrics were used for evaluation:

Precision: Measures the proportion of correctly identified gaming participants out of all samples predicted as gaming. A higher precision indicates fewer false positives.

Recall: Measures the sensitivity of the model in correctly identifying gaming participants, reflecting the ability to detect actual gaming cases.

F-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing false positives and false negatives. It provides a single measure of a model’s effectiveness.

PR-AUC (Precision-Recall Area Under the Curve): Evaluates model performance, particularly for imbalanced datasets, by analyzing the trade-off between precision and recall across different thresholds.

To mitigate potential bias, classification models were trained and tested using independent data splits for each fold. This approach ensured that no overlapping data was used in both training and testing phases within the same fold, maintaining the integrity of the model evaluation process.

3. Results

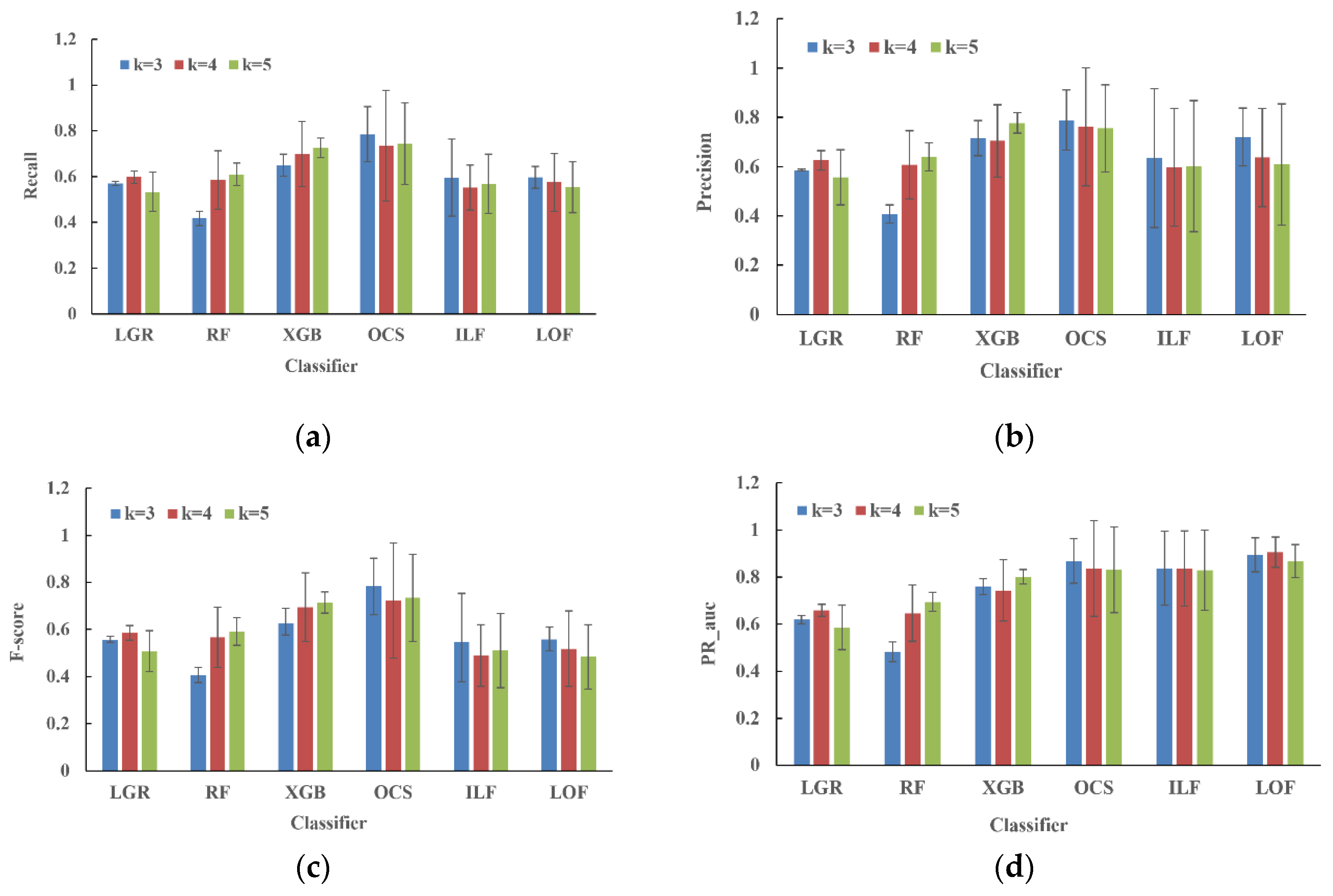

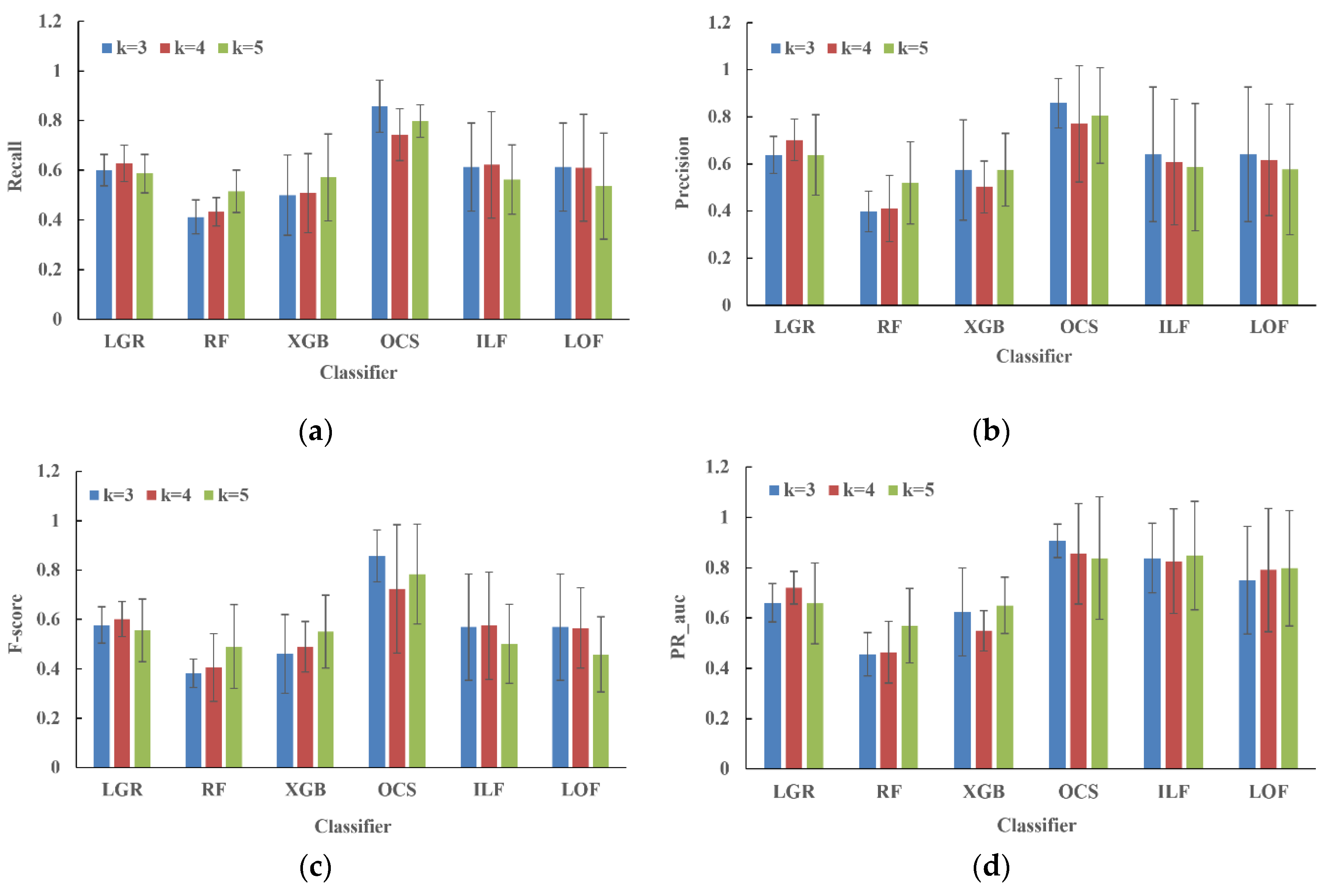

To evaluate the performance of different classification models in distinguishing between gaming and resting states, we analyzed the results for both 5-minute and 10-minute data segments. For the 5-minute data segments, the results were Recall: 0.785 ± 0.121, Precision: 0.788 ± 0.122, F-score: 0.783 ± 0.119, PR-AUC: 0.868 ± 0.095. For the 10-minute data segments, the results were Recall: 0.858 ± 0.105, Precision: 0.858 ± 0.105, F-score: 0.858 ± 0.105, PR-AUC: 0.906 ± 0.066. Among all classifiers tested, One-Class SVM (OCS) with k=3 consistently achieved the highest performance in both conditions (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.). These values indicate that the model was able to effectively identify gaming participants while maintaining a balance between precision and recall.

Table 2.

HRV index of the gaming group.

Table 2.

HRV index of the gaming group.

| Participants |

MRR

[ms]

|

SDRR [ms] |

VLF [ln,ms2] |

LF [ln,ms2] |

HF [ln,ms2] |

LF/HF

[ratio]

|

HF freq

[Hz]

|

| G1 |

803 |

91 |

8.30 |

6.89 |

5.02 |

6.44 |

0.228 |

| G2 |

724 |

78 |

7.94 |

7.19 |

5.58 |

5.01 |

0.233 |

| G3 |

722 |

90 |

8.01 |

7.42 |

6.20 |

3.38 |

0.243 |

| G4 |

637 |

33 |

5.61 |

5.71 |

4.33 |

3.97 |

0.246 |

| G5 |

511 |

44 |

6.35 |

6.23 |

4.71 |

4.56 |

0.228 |

| G6 |

776 |

74 |

7.30 |

7.14 |

6.18 |

2.61 |

0.234 |

| Mean±S.D. |

696±98 |

69±22 |

7.25±0.97 |

6.76±0.60 |

5.34±0.71 |

4.33±1.22 |

0.235±0.007 |

Table 3.

HRV index of the seated rest control group.

Table 3.

HRV index of the seated rest control group.

| Participants |

MRR

[ms]

|

SDRR [ms] |

VLF [ln,ms2] |

LF [ln,ms2] |

HF [ln,ms2] |

LF/HF

[ratio]

|

HF freq [Hz] |

| R1 |

571 |

21 |

5.16 |

4.90 |

3.42 |

4.38 |

0.296 |

| R2 |

694 |

57 |

6.85 |

7.10 |

6.28 |

2.27 |

0.215 |

| R3 |

769 |

47 |

6.84 |

6.79 |

5.72 |

2.92 |

0.219 |

| R4 |

1055 |

113 |

8.44 |

7.38 |

6.16 |

3.40 |

0.247 |

| R5 |

575 |

28 |

5.66 |

4.75 |

3.47 |

3.59 |

0.253 |

| R6 |

706 |

45 |

6.71 |

5.88 |

5.68 |

1.23 |

0.268 |

| R7 |

775 |

38 |

6.19 |

5.74 |

5.14 |

1.82 |

0.234 |

| Mean±S.D. |

735±151 |

50±28 |

6.55±0.937 |

6.08±0.970 |

5.12±1.12 |

2.08±1.02 |

0.247±0.026 |

4. Discussion

The PR-AUC score further suggests strong discrimination ability, even in potentially imbalanced data scenarios. The improvement in performance for 10-minute segments suggests that longer ECG recordings provide a more stable representation of heart rate variability (HRV) features, leading to enhanced classification accuracy. The PR-AUC score of 0.906 confirms the robustness of the OCS model in distinguishing between gaming and resting states.

In recent years, machine learning (ML) approaches applied to heart rate variability (HRV) analysis have been widely utilized for various health-related applications, such as detecting cardiovascular diseases, assessing fatigue, and monitoring stress levels [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. However, research focusing on HRV-based classification of gaming behavior remains relatively scarce. Given the increasing prevalence of excessive gaming and its associated health risks, the present study holds significance in demonstrating the feasibility of using HRV-based ML models to distinguish gaming activity from resting states. Our findings suggest that specific autonomic nervous system responses may be leveraged as biomarkers for identifying gaming behavior, providing a novel contribution to this field.

One of the strengths of this study is that the experimental setup was limited to a seated posture, ensuring that participants exhibited minimal physical movement. This likely contributed to the relatively high classification accuracy, as postural consistency reduces motion artifacts and physiological noise that can otherwise complicate HRV analysis. Moreover, previous studies have extensively explored the identification of seated postures using body acceleration data, indicating that when posture is restricted to sitting, machine learning-based classification of gaming versus non-gaming states is feasible [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. However, this study’s approach may not generalize to gaming activities that involve significant body movement, such as virtual reality (VR) gaming or physically interactive games like those requiring motion controllers. In such cases, HRV-based classification may become less reliable due to additional physiological variations induced by movement, highlighting a key limitation of this research.

Despite these limitations, our study remains relevant given the growing concern over gaming and smartphone addiction, which are increasingly recognized as modern-day public health issues. Excessive gaming has been linked to poor mental health, disrupted sleep patterns, and diminished cognitive function, making it essential to develop objective methods for identifying and monitoring gaming behavior. Although this study does not directly address addiction classification, it establishes a foundation for using physiological data to differentiate gaming behavior, which could be expanded upon in future research. Integrating HRV analysis with additional physiological and behavioral indicators—such as eye-tracking, galvanic skin response, or EEG data—could enhance classification accuracy and provide deeper insights into the autonomic changes associated with excessive gaming. In conclusion, this study demonstrates the potential of HRV-based machine learning classification in distinguishing gaming states, contributing to the relatively unexplored field of gaming behavior analysis. While the study is limited to seated posture and controlled conditions, it provides a stepping stone for future research into real-world applications, where continuous physiological monitoring could be utilized for gaming addiction detection and intervention strategies.

Finally, we discuss the future directions of this study. In this study, we demonstrated that machine learning can be used to classify ECG signals and distinguish gameplay individuals to some extent. However, several aspects need to be further investigated to improve the accuracy and applicability of this approach. First, the expansion of the dataset and the diversity of participants. A larger and more diverse participant pool should be incorporated to improve the generalizability of the classification model. Factors such as age, gender, gaming history, and psychological state should be considered to improve classification performance. Second, feature engineering and advanced machine learning models. In this study, we focused primarily on HRV-based classification. However, future research should investigate the analysis of ECG waveforms using pattern matching techniques and additional physiological markers such as heart rate acceleration patterns and nonlinear HRV metrics. In addition, deep learning approaches such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) can be used to extract complex temporal features from ECG signals. And integration of real-time monitoring and wearable devices will also be necessary. To enhance practical applications, the integration of the ECG-based classification model into wearable devices would allow for real-time monitoring of physiological responses during gaming. This would facilitate early intervention strategies and personalized feedback systems for individuals at risk for gaming addiction. Finally, comparison with other physiological and behavioral indices is necessary. Future studies should investigate the integration of not only ECG-based classification but also other physiological signals, such as electrodermal activity (EDA) and body surface temperature, and behavioral indices, such as eye tracking and bioacceleration. Multimodal data fusion is predicted to improve classification accuracy and provide deeper insights into gaming addiction. Longitudinal studies are also needed to evaluate the long-term effects of gaming addiction on autonomic function. The development of intervention strategies, such as biofeedback-based training and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), could be an important application of this research. By addressing these directions, future studies can further refine the ECG-based classification model, increase its applicability in the real world, and contribute to the development of effective intervention strategies for game play time estimation.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the feasibility of using HRV analysis combined with machine learning to classify gaming and resting states. One-Class SVM (OCS) with k=3 provided the best performance both 5-minute and 10-minute data segments. The seated posture condition allowed for easier classification due to reduced movement, though the method may face challenges with gaming activities that involve significant body motion. Despite these limitations, the study highlights the potential of HRV-based approaches for detecting gaming behavior, contributing to the development of monitoring tools for excessive gaming, which is increasingly recognized as a modern health concern.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Y. and T.U; methodology, T.U.; software, Y.Y.; validation, E.Y. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, E.Y. and Y.Y; investigation, E.Y. and T.U; resources, T.U. and H.E; data curation, Y.E., Y.Y and T.U; writing—original draft preparation, E.Y.; writing—review and editing, E.Y.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, E.Y.; project administration, E.Y. and T.U; funding acquisition, E.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Fukuyama University (No.2024-H-52, Approved 2024/10/11).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the analysis of this study will be made available for research purposes with the consent of the authors, but will only be made available to research institutions. A portion of the data used in this study is available for research purposes. Interested researchers can request access by contacting the corresponding author. For inquiries regarding the data or collaboration opportunities, please reach out yoshida.icsdf “at” mie-u.ac.jp.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who volunteered for this study. Their cooperation and willingness to contribute to this research were invaluable to the success of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mori, A.; Iwadate, M.; Minakawa, N.T.; Kawashima, S. Game play decreases prefrontal cortex activity and causes damage in game addiction. Nihon Rinsho 2015, 73, 1567–1573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Limone, P.; Ragni, B.; Toto, G.A. The epidemiology and effects of video game addiction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 2023, 241, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menéndez-García, A.; Jiménez-Arroyo, A.; Rodrigo-Yanguas, M.; Marin-Vila, M.; Sánchez-Sánchez, F.; Roman-Riechmann, E.; Blasco-Fontecilla, H. Internet, video game and mobile phone addiction in children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD: A case-control study. Adicciones 2022, 34, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S.Q.; Cheng, J.L.; Li, Y.Y.; Yang, X.Q.; Zheng, J.W.; Chang, X.W.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, L.; Sun, Y.; Bao, Y.P.; Shi, J. Global prevalence of digital addiction in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 92, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, D.N. Clinical considerations in internet and video game addiction treatment. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 31, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, C.L.; Morrell, H.E.R.; Molle, J.E. Video game addiction, ADHD symptomatology, and video game reinforcement. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2019, 45, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, D.N. Treatment considerations in internet and video game addiction: A qualitative discussion. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 27, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, D.A.; Choo, H.; Liau, A.; Sim, T.; Li, D.; Fung, D.; Khoo, A. Pathological video game use among youths: A two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e319–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Xiao, X.Y.; Huang, W.J.; Wang, F.; Shen, X.Q.; Jia, F.J.; Hou, C.L. Video game addiction in psychiatric adolescent population: A hospital-based study on the role of individualism from South China. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylona, I.; Deres, E.S.; Dere, G.S.; Tsinopoulos, I.; Glynatsis, M. The Impact of Internet and Video Gaming Addiction on Adolescent Vision: A Review of the Literature. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H. The cognitive psychology of Internet gaming disorder. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, M.W.; Dorstyn, D.; Delfabbro, P.H.; King, D.L. Global prevalence of gaming disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2021, 55, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, M.R.; Serra, N.; Guillari, A.; Simeone, S.; Sarracino, F.; Continisio, G.I.; Rea, T. An investigation into video game addiction in pre-adolescents and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Medicina 2020, 56, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, A.M. Computer and video game addiction—a comparison between game users and non-game users. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2010, 36, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, D.J.; Im, S.K.; Kim, M.S. Identification of Video Game Addiction Using Heart-Rate Variability Parameters. Sensors (Basel) 2021, 21, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odenstedt Hergès H, Vithal R, El-Merhi A, Naredi S, Staron M, Block L. Machine learning analysis of heart rate variability to detect delayed cerebral ischemia in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurol Scand. [CrossRef]

- Ambale-Venkatesh B, Yang X, Wu CO, Liu K, Hundley WG, McClelland R, Gomes AS, Folsom AR, Shea S, Guallar E, Bluemke DA, Lima JAC. Cardiovascular Event Prediction by Machine Learning: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 1: 13;121(9), 1092. [CrossRef]

- Guo CY, Wu MY, Cheng HM. The Comprehensive Machine Learning Analytics for Heart Failure. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 6 May 4943. [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Cao F, Wang L, Liu W, Gao M, Zhang L, Hong F, Lin M. Machine learning model and nomogram to predict the risk of heart failure hospitalization in peritoneal dialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2324. [CrossRef]

- Accardo A, Silveri G, Merlo M, Restivo L, Ajčević M, Sinagra G. Detection of subjects with ischemic heart disease by using machine learning technique based on heart rate total variability parameters. Physiol Meas. [CrossRef]

- Agliari E, Barra A, Barra OA, Fachechi A, Franceschi Vento L, Moretti L. Detecting cardiac pathologies via machine learning on heart-rate variability time series and related markers. Sci Rep. 8: 1;10(1), 8845. [CrossRef]

- Nemati S, Holder A, Razmi F, Stanley MD, Clifford GD, Buchman TG. An Interpretable Machine Learning Model for Accurate Prediction of Sepsis in the ICU. Crit Care Med. [CrossRef]

- Chiew CJ, Liu N, Tagami T, Wong TH, Koh ZX, Ong MEH. Heart rate variability based machine learning models for risk prediction of suspected sepsis patients in the emergency department. Medicine (Baltimore). 1419. [CrossRef]

- Geng D, An Q, Fu Z, Wang C, An H. Identification of major depression patients using machine learning models based on heart rate variability during sleep stages for pre-hospital screening. Comput Biol Med. 1070. [CrossRef]

- Matuz A, van der Linden D, Darnai G, Csathó Á. Generalisable machine learning models trained on heart rate variability data to predict mental fatigue. Sci Rep. 2: 21;12(1), 2002. [CrossRef]

- Ni Z, Sun F, Li Y. Heart Rate Variability-Based Subjective Physical Fatigue Assessment. Sensors (Basel). 3: 21;22(9), 3199. [CrossRef]

- Lee KFA, Gan WS, Christopoulos G. Biomarker-Informed Machine Learning Model of Cognitive Fatigue from a Heart Rate Response Perspective. Sensors (Basel). 3: 2;21(11), 3843. [CrossRef]

- Fan J, Mei J, Yang Y, Lu J, Wang Q, Yang X, Chen G, Wang R, Han Y, Sheng R, Wang W, Ding F. Sleep-phasic heart rate variability predicts stress severity: Building a machine learning-based stress prediction model. Stress Health. 3386. [CrossRef]

- Cao R, Rahmani AM, Lindsay KL. Prenatal stress assessment using heart rate variability and salivary cortisol: A machine learning-based approach. PLoS One. e: 9;17(9), 0274; eCollection 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bahameish M, Stockman T, Requena Carrión J. Strategies for Reliable Stress Recognition: A Machine Learning Approach Using Heart Rate Variability Features. Sensors (Basel). 18 May 3210. [CrossRef]

- Tsai CY, Majumdar A, Wang Y, Hsu WH, Kang JH, Lee KY, Tseng CH, Kuan YC, Lee HC, Wu CJ, Houghton R, Cheong HI, Manole I, Lin YT, Li LJ, Liu WT. Machine learning model for aberrant driving behaviour prediction using heart rate variability: a pilot study involving highway bus drivers. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 1429. [CrossRef]

- Pop GN, Christodorescu R, Velimirovici DE, Sosdean R, Corbu M, Bodea O, Valcovici M, Dragan S. Assessment of the Impact of Alcohol Consumption Patterns on Heart Rate Variability by Machine Learning in Healthy Young Adults. Medicina (Kaunas). 9: 11;57(9). [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tse, M.M.Y.; Chung, J.W.Y.; Yau, S.Y.; Wong, T.K.S. Effects of Posture on Heart Rate Variability in Non-Frail and Prefrail Individuals: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallman, D.M.; Sato, T.; Kristiansen, J.; Gupta, N.; Skotte, J.; Holtermann, A. Prolonged Sitting is Associated with Attenuated Heart Rate Variability during Sleep in Blue-Collar Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14811–14827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, K.C.; Kwon, M.K.; Kim, D.W. Effects of Posture and Acute Sleep Deprivation on Heart Rate Variability. Yonsei Med. J. 2011, 52, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Das, A.K.; Halder, S. Statistical Heart Rate Variability Analysis for Healthy Person: Influence of Gender and Body Posture. J. Electrocardiol. 2023, 79, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuangchai, W.; Pothisiri, W. Postural Changes on Heart Rate Variability among Older Population: A Preliminary Study. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2021, 2021, 6611479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).