Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

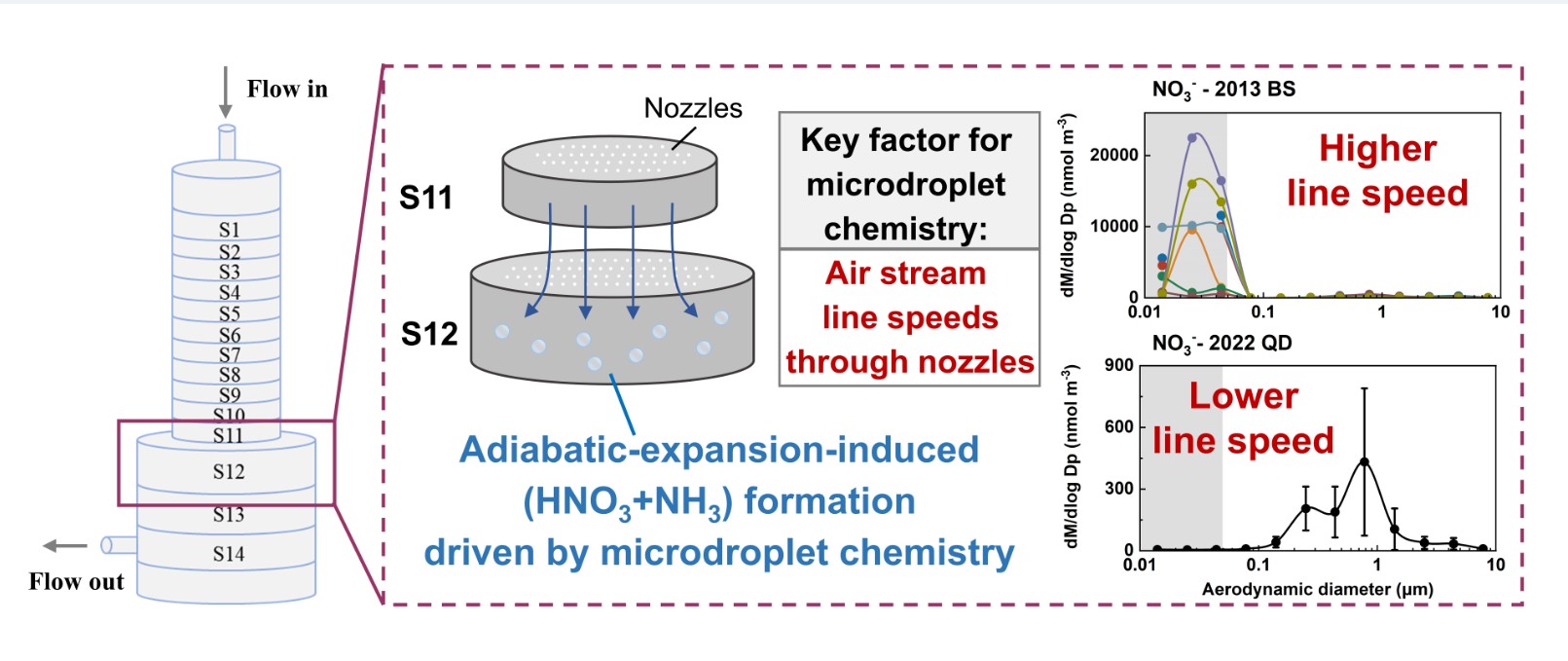

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Intruduction

2. Experimental

3. Materials and Methods

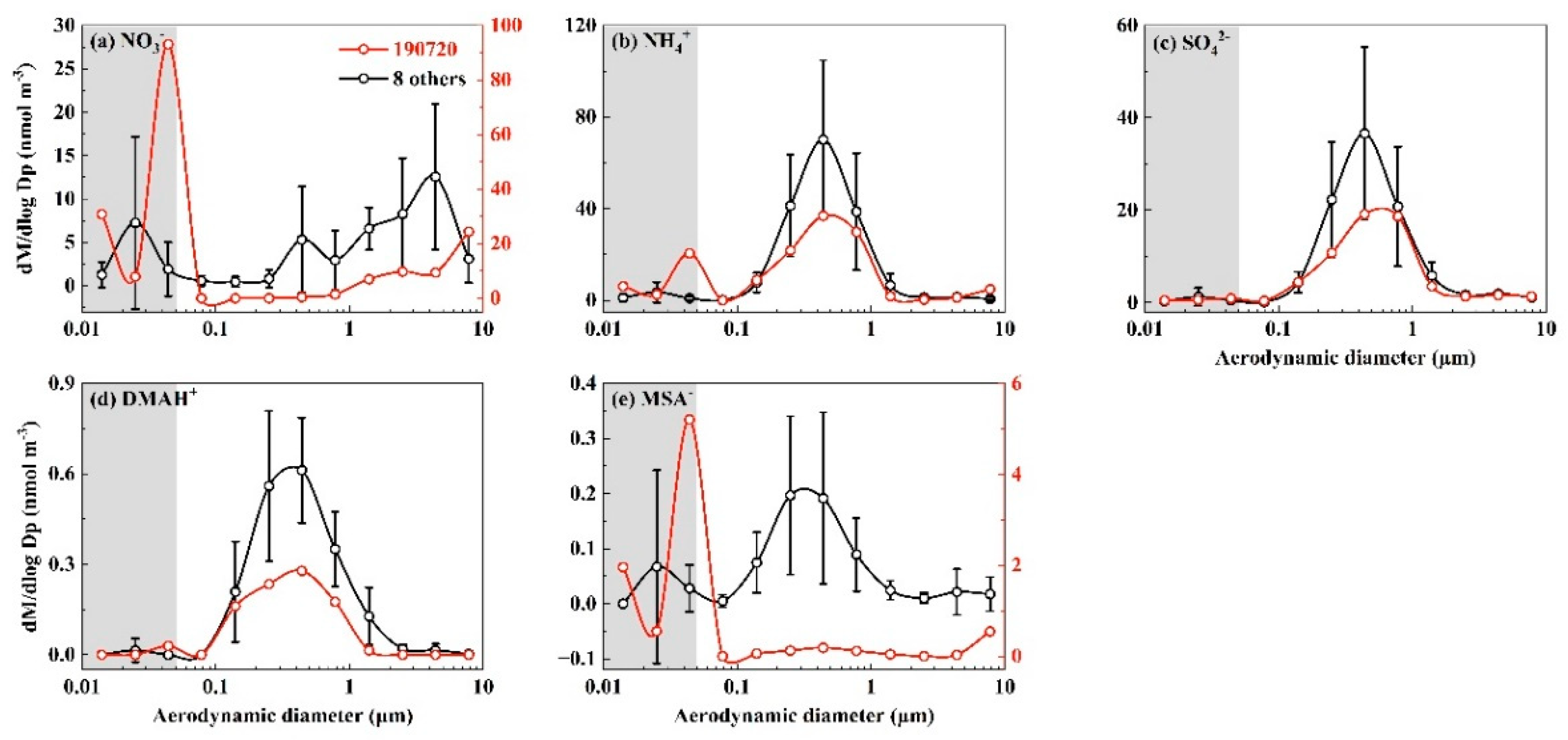

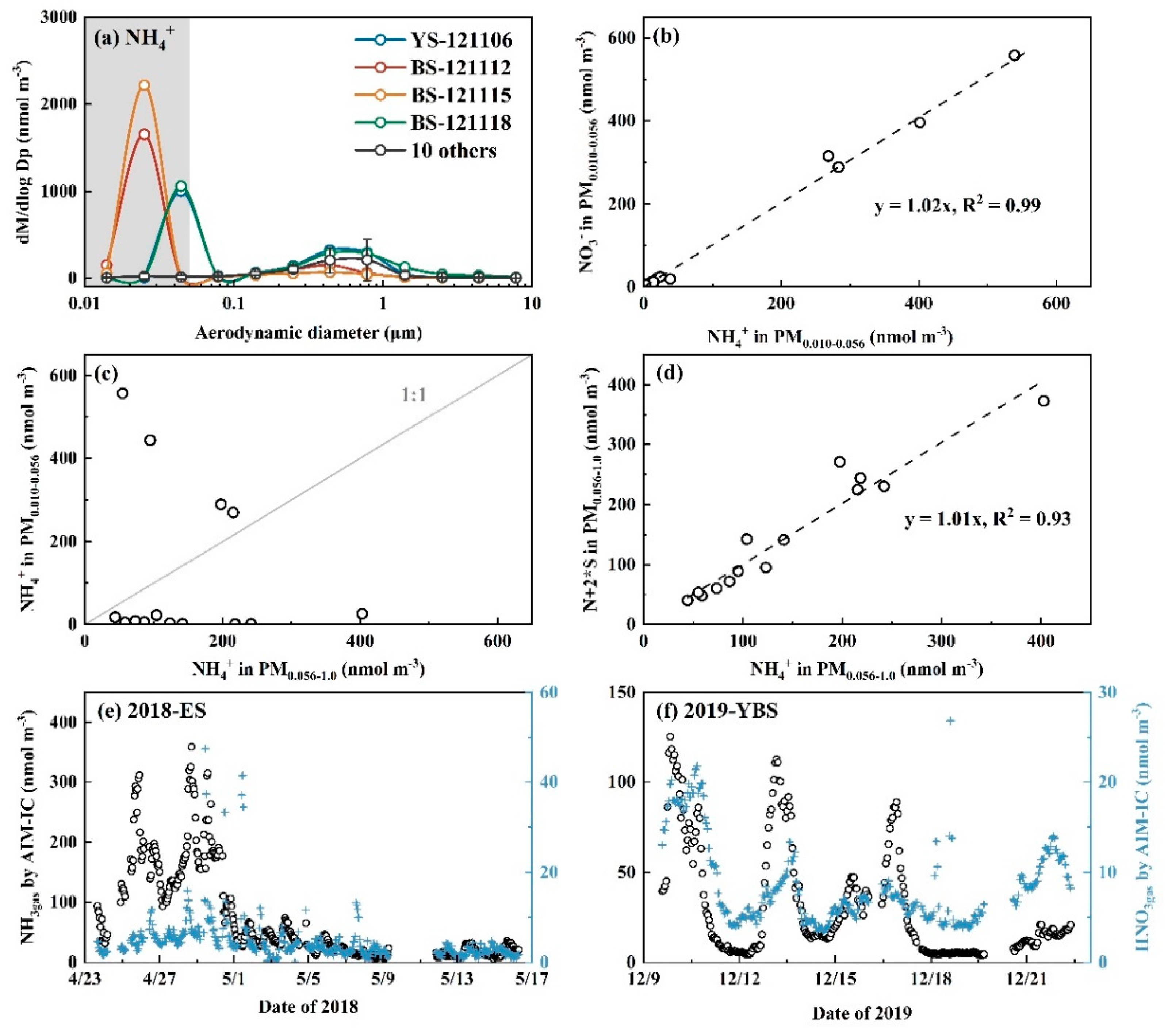

3.1. Perturbation Formation of Comparable NH4NO3 and Organic Nitrate in Campaigns 8 and 9

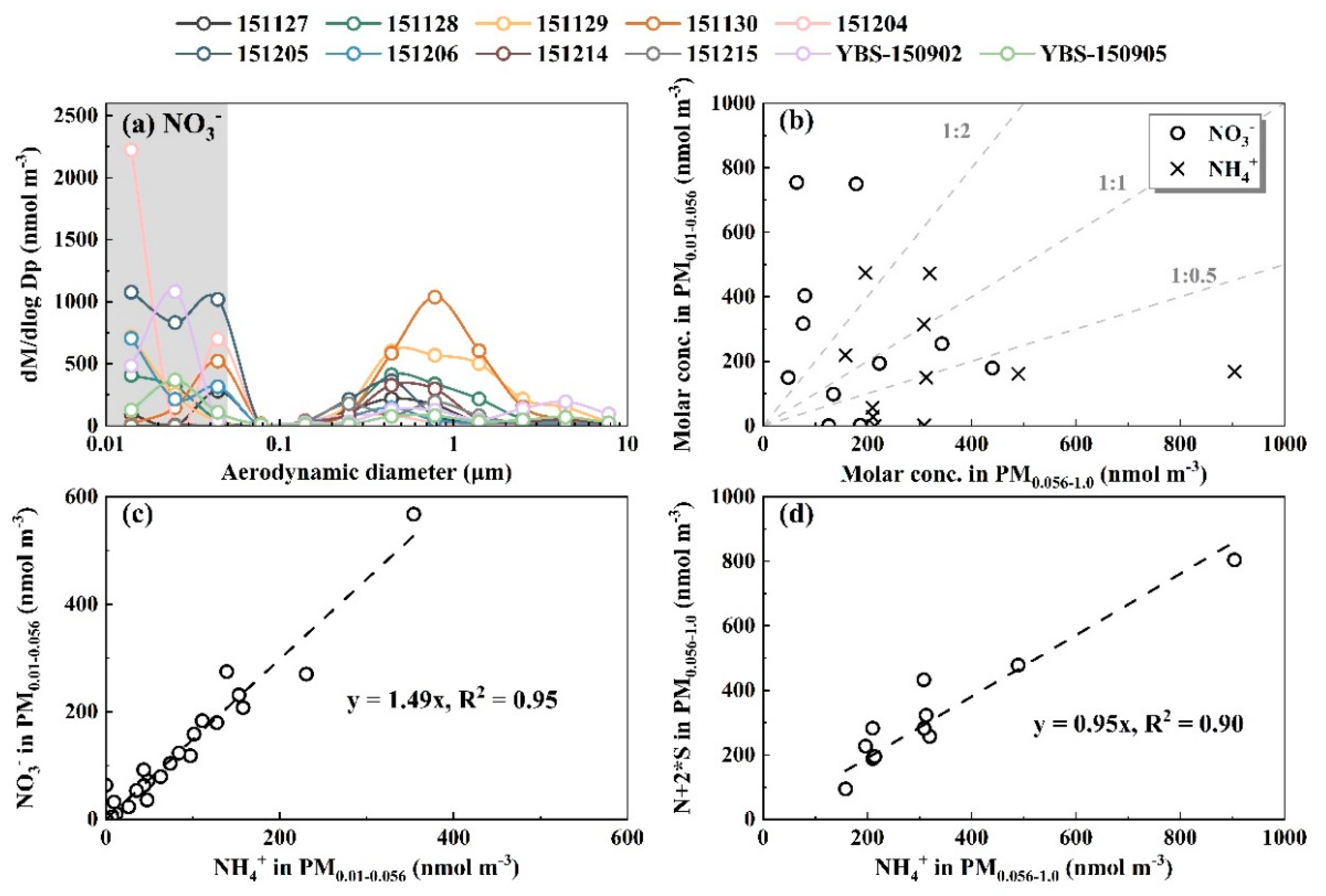

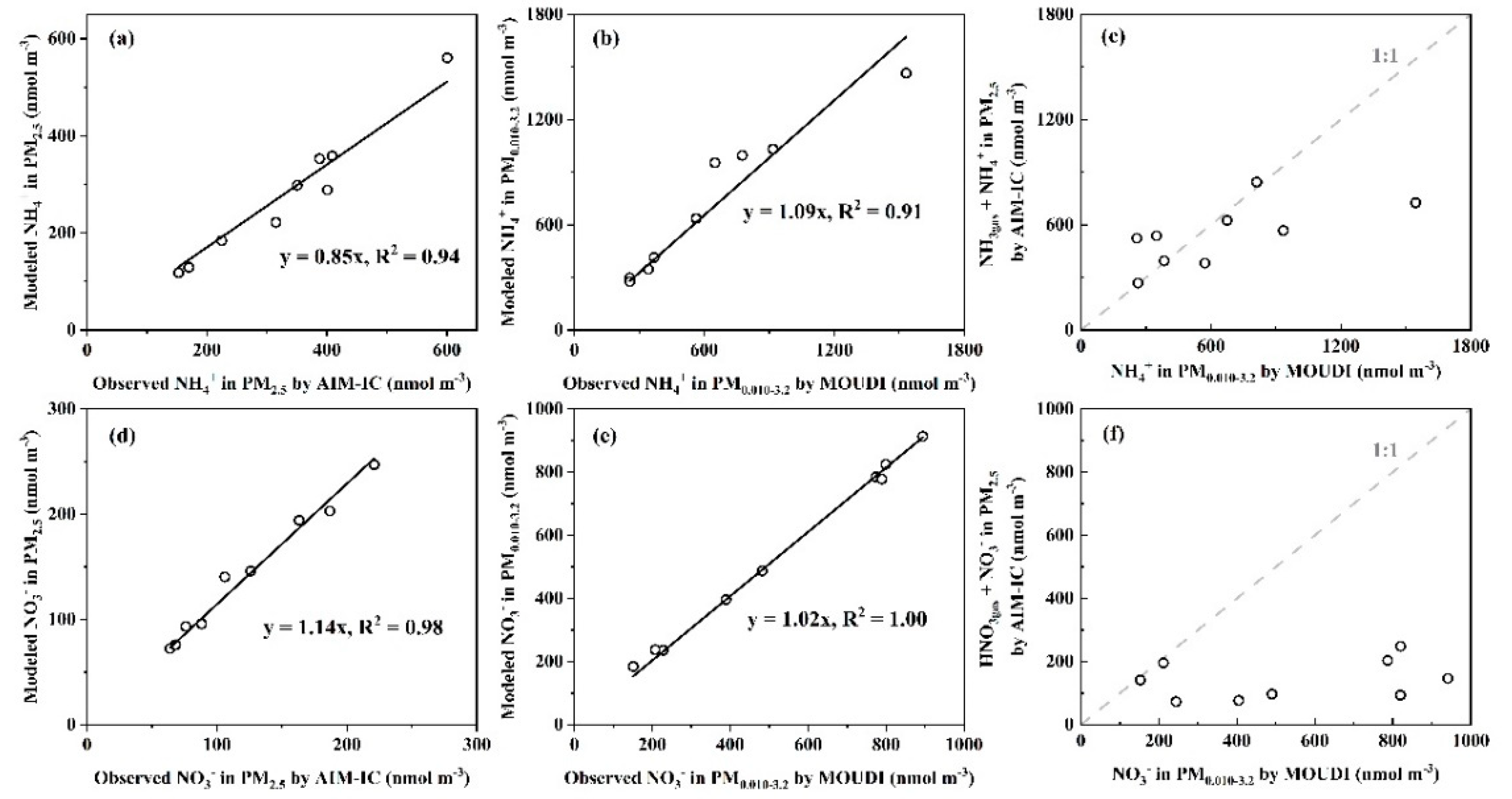

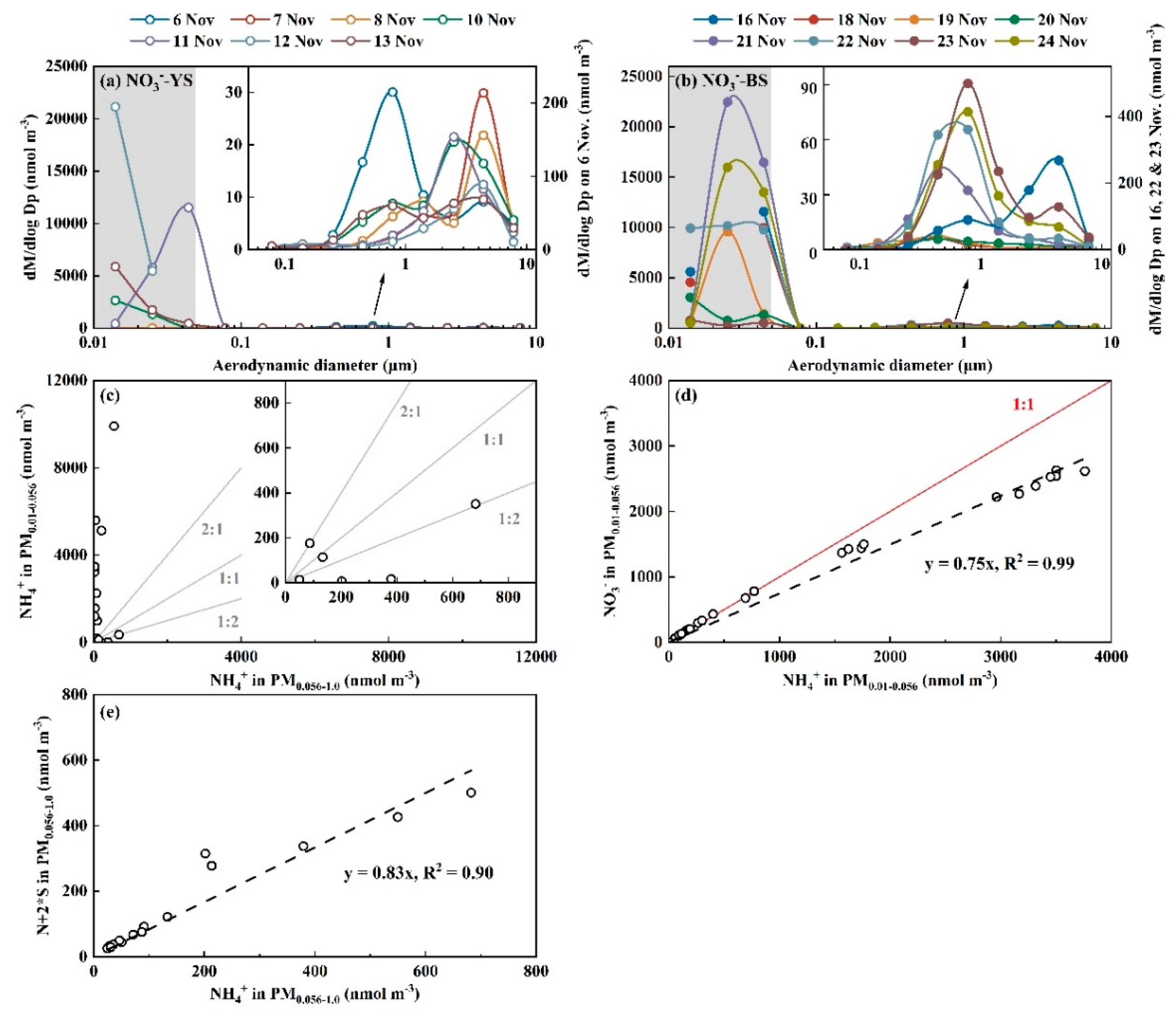

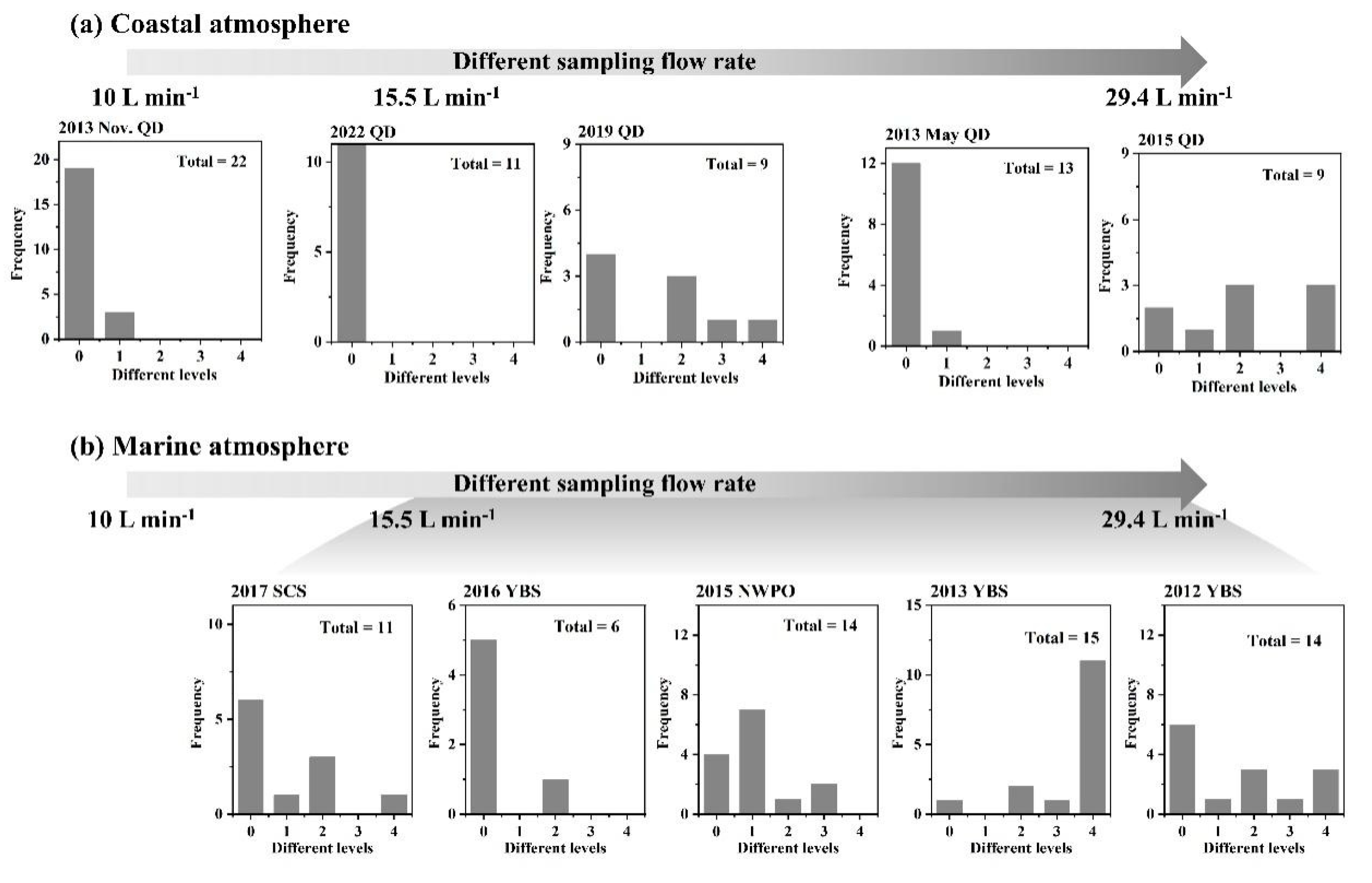

3.2. Whether Is Adiabatic Perturbation Alone Sufficient to Explain NO3- and NH4+ Detected on the Last Three Stages of Nano-MOUDI Sampling in Cold Coastal Atmospheres?

3.3. Adiabatic Perturbation Superimposed Ultrafast Formation of Huge Amounts of NH4NO3 and Organic Nitrate at the Last Three Stages of Nano-MOUDI Sampling in Marine Atmospheres

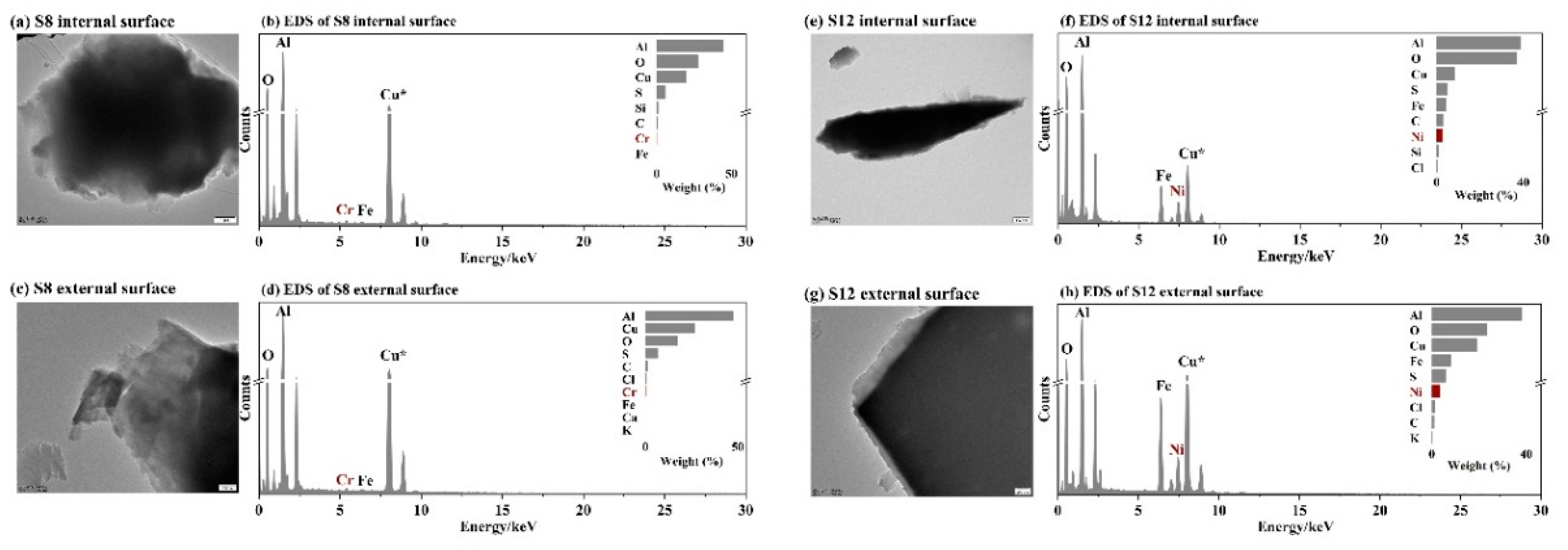

3.4. Key Factors in Determining Ultrafast Formation of (HNO3+NH3) and Organic Nitrate: Evidences and Uncertainties

4. Implication

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIM-IC | Ambient Ion Monitor – Ion Chromatograph |

| DMAH+ | particulate dimethylaminium |

| EDS | Energy Dispersive Spectrometer |

| ES | the East China Sea |

| E-AIM | Extended AIM Aerosol Thermodynamics Model |

| MSA- | particulate methanesulfonic acid |

| Nano MOUDI-II | Nano Micro-Orifice Uniform-Deposit Impactor, second generation |

| N + 2 * S | the sum of the molar concentration of nitrate and twice the molar concentration of sulfate |

| PM2.5 | particulate matter with the aerodynamic diameter below 2.5 μm collected by AIM-IC |

| PM0.010-0.056/PM0.010-3.2/PM0.056-1.0/PM0.056-3.2 | particulate matter with the aerodynamic diameter of 0.010-0.056/0.010-3.2/0.056-1.0/0.056-3.2 μm collected by Nano MOUDI-II |

| SCS | the South China Seat |

| S8/S12 | the 8th or 12th stage of Nano MOUDI-II |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscope |

| UTLS | upper troposphere and lower stratosphere |

| YBS | the Yellow Sea and the Bohai Sea |

References

- Behera, S.N.; Sharma, M.; Aneja, V.P.; Balasubramanian, R. Ammonia in the atmosphere: a review on emission sources, atmospheric chemistry and deposition on terrestrial bodies. Environ Sci Pollut R 2013, 20, 8092-8131.

- Peng, J.; Hu, M.; Shang, D.; Wu, Z.; Du, Z.; Tan, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, R. Explosive secondary aerosol formation during severe haze in the North China Plain. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55, 2189-2207.

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, 2016.

- Altieri, K.E.; Fawcett, S.E.; Hastings, M.G. Reactive nitrogen cycling in the atmosphere and ocean. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 2021, 49, 523-550.

- Lan, Z.; Lin, W.; Zhao, G. Sources, Variations, and effects on air quality of atmospheric ammonia. Curr Pollut Rep 2024, 10, 40-53.

- Nair, A.A.; Yu, F. Quantification of atmospheric ammonia concentrations: a review of its measurement and modeling. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1092.

- Froyd, K.D.; Murphy, D.M.; Sanford, T.J.; Thomson, D.S.; Wilson, J.C.; Pfister, L.; Lait, L. Aerosol composition of the tropical upper troposphere. Atmos Chem Phys 2009, 9, 4363-4385.

- Ge, C.; Zhu, C.; Francisco, J.S.; Zeng, X.C.; Wang, J. A molecular perspective for global modeling of upper atmospheric NH3 from freezing clouds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 6147-6152.

- Höpfner, M.; Volkamer, R.; Grabowski, U.; Grutter, M.; Orphal, J.; Stiller, G.; von Clarmann, T.; Wetzel, G. First detection of ammonia (NH3) in the Asian summer monsoon upper troposphere. Atmos Chem Phys 2016, 16, 14357-14369.

- Altieri, K.E.; Spence, K.A.M.; Smith, S. Air-sea ammonia fluxes calculated from high-resolution summertime observations across the Atlantic Southern Ocean. Geophys Res Lett 2021, 48, e2020GL091963.

- Bouwman, A.F.; Lee, D.S.; Asman, W.A.H.; Dentener, F.J.; Van Der Hoek, K.W.; Olivier, J.G.J. A global high-resolution emission inventory for ammonia. Global Biogeochem Cy 1997, 11, 561-587.

- Chen, D.; Yao, X.; Chan, C.K.; Tian, X.; Chu, Y.; Clegg, S.L.; Shen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Gao, H. Competitive uptake of dimethylamine and trimethylamine against ammonia on acidic particles in marine atmospheres. Environ Sci Technol 2022, 56, 5430-5439.

- Paulot, F.; Jacob, D.J.; Johnson, M.; Bell, T.G.; Baker, A.R.; Keene, W.C.; Lima, I.D.; Doney, S.C.; Stock, C.A. Global oceanic emission of ammonia: Constraints from seawater and atmospheric observations. Global Biogeochem Cy 2015, 29, 1165-1178.

- Song, X.; Basheer, C.; Zare, R.N. Making ammonia from nitrogen and water microdroplets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e1993761176.

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Liang, J.; Yue, L.; Li, T.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, N.; Tang, B.; Gong, F.; Guo, X.; Sun, X. Enhancing electrocatalytic NO reduction to NH3 by the CoS nanosheet with sulfur vacancies. Inorg Chem 2022, 61, 8096-8102.

- Liu, Q.; Xu, T.; Luo, Y.; Kong, Q.; Li, T.; Lu, S.; Alshehri, A.A.; Alzahrani, K.A.; Sun, X. Recent advances in strategies for highly selective electrocatalytic N2 reduction toward ambient NH3 synthesis. Curr Opin Electroche 2021, 29, 100766.

- Gao, Y.; Yao, X. An adiabatic-expansion-induced perturbation study on gas-aerosol partitioning in ambient air – dimethylamine and trimethylamine (1). Unpublished Results.

- Yu, P.; Hu, Q.; Li, K.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, H.; Yao, X. Characteristics of dimethylaminium and trimethylaminium in atmospheric particles ranging from supermicron to nanometer sizes over eutrophic marginal seas of China and oligotrophic open oceans. Sci Total Environ 2016, 572, 813-824.

- Xie, H.; Feng, L.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, H.; Gao, Y.; Yao, X. Concentration and size distribution of water-extracted dimethylaminium and trimethylaminium in atmospheric particles during nine campaigns - Implications for sources, phase states and formation pathways. Sci Total Environ 2018, 631-632, 130-141.

- Hu, Q.; Qu, K.; Gao, H.; Cui, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yao, X. Large increases in primary trimethylaminium and secondary dimethylaminium in atmospheric particles associated with cyclonic eddies in the northwest Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 12, 112-133, 146.

- Shen, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Chan, C.K.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, H.; Petäjä, T.; Yao, X. Sources and formation of nucleation mode particles in remote tropical marine atmospheres over the South China Sea and the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Sci Total Environ 2020, 735, 139302.

- Clegg, S.L.; Kleeman, M.J.; Griffin, R.J.; Seinfeld, J.H. Effects of uncertainties in the thermodynamic properties of aerosol components in an air quality model – Part 1: Treatment of inorganic electrolytes and organic compounds in the condensed phase. Atmos Chem Phys 2008, 8, 1057-1085.

- Kittelson, D.B. Engines and nanoparticles: a review. J Aerosol Sci 1998, 29, 575-588.

- Cass, G.R.; Hughes, L.A.; Bhave, P.; Kleeman, M.J.; Allen, J.O.; Salmon, L.G. The chemical composition of atmospheric ultrafine particles. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2000, 358, 2581-2592.

- Gaffney, J.S.; Marley, N.A. The impacts of peroxyacetyl nitrate in the atmosphere of megacities and large urban areas: a historical perspective. Acs Earth Space Chem 2021, 5, 1829-1841.

- Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Cai, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, W.; Li, J.; Gong, D.; Chen, D.; Zhai, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liao, T.; Wang, B. Complexities of peroxyacetyl nitrate photochemistry and its control strategies in contrasting environments in the Pearl River Delta region. Npj Clim Atmos Sci 2024, 7, 116.

- Heindel, J.P.; LaCour, R.A.; Head-Gordon, T. The role of charge in microdroplet redox chemistry. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 3670.

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, D.; Liang, C.; Zhang, X. Spontaneous reduction of transition metal ions by one electron in water microdroplets and the atmospheric implications. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145, 2800-2805.

- Qin, Y.; Wingen, L.M.; Finlayson-Pitts, B.J. Toward a molecular understanding of the surface composition of atmospherically relevant organic particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119, e2085833177.

- Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Ding, X.; Deng, W.; Lü, S.; Zhang, Y. Emission factor of ammonia (NH3) from on-road vehicles in China: tunnel tests in urban Guangzhou. Environ Res Lett 2014, 9, 64027.

- Lee, J.K.; Samanta, D.; Nam, H.G.; Zare, R.N. Micrometer-sized water droplets induce spontaneous reduction. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 10585-10589.

- Chen, D.; Shen, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Gao, H.; Yao, X. Mapping gaseous dimethylamine, trimethylamine, ammonia, and their particulate counterparts in marine atmospheres of China's marginal seas – Part 1: Differentiating marine emission from continental transport. Atmos Chem Phys 2021, 21, 16413-16425.

- Xiong, H.; Lee, J.K.; Zare, R.N.; Min, W. Strong electric field observed at the interface of aqueous microdroplets. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 7423-7428.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).