Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

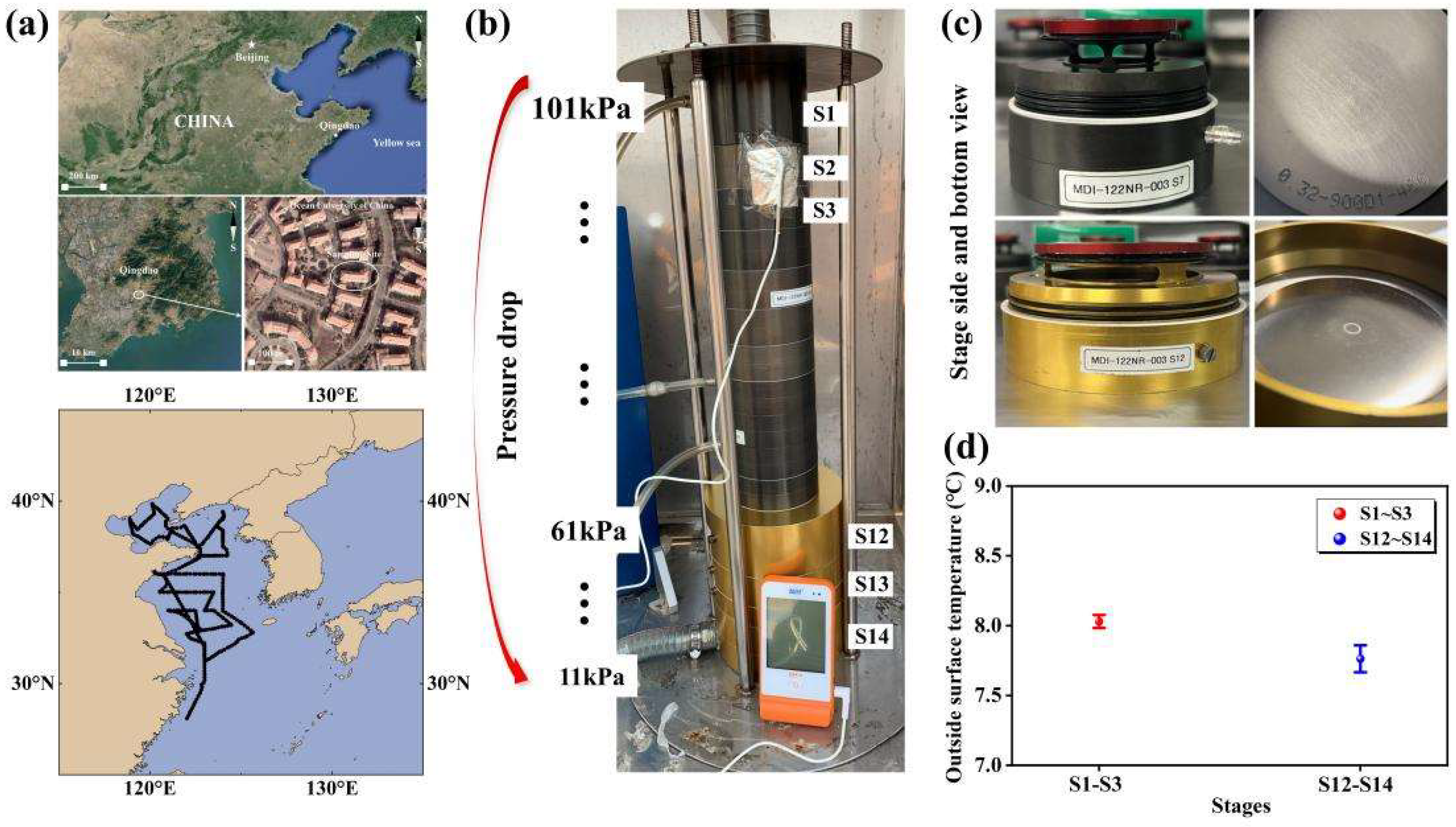

2.1. Sampling and Chemical Analysis

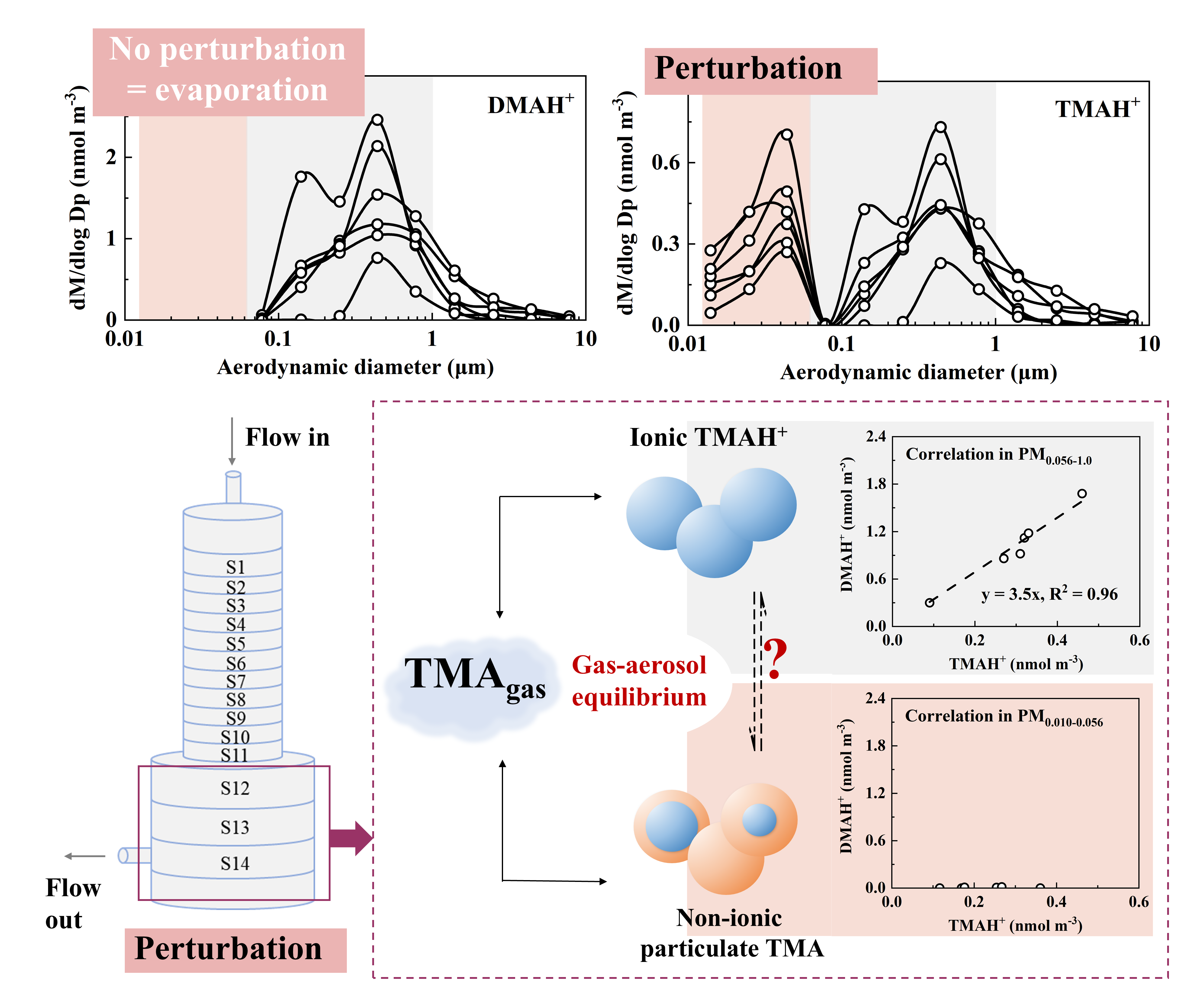

2.2. Hypothesis for Perturbation Scenarios

3. Results and Discussion

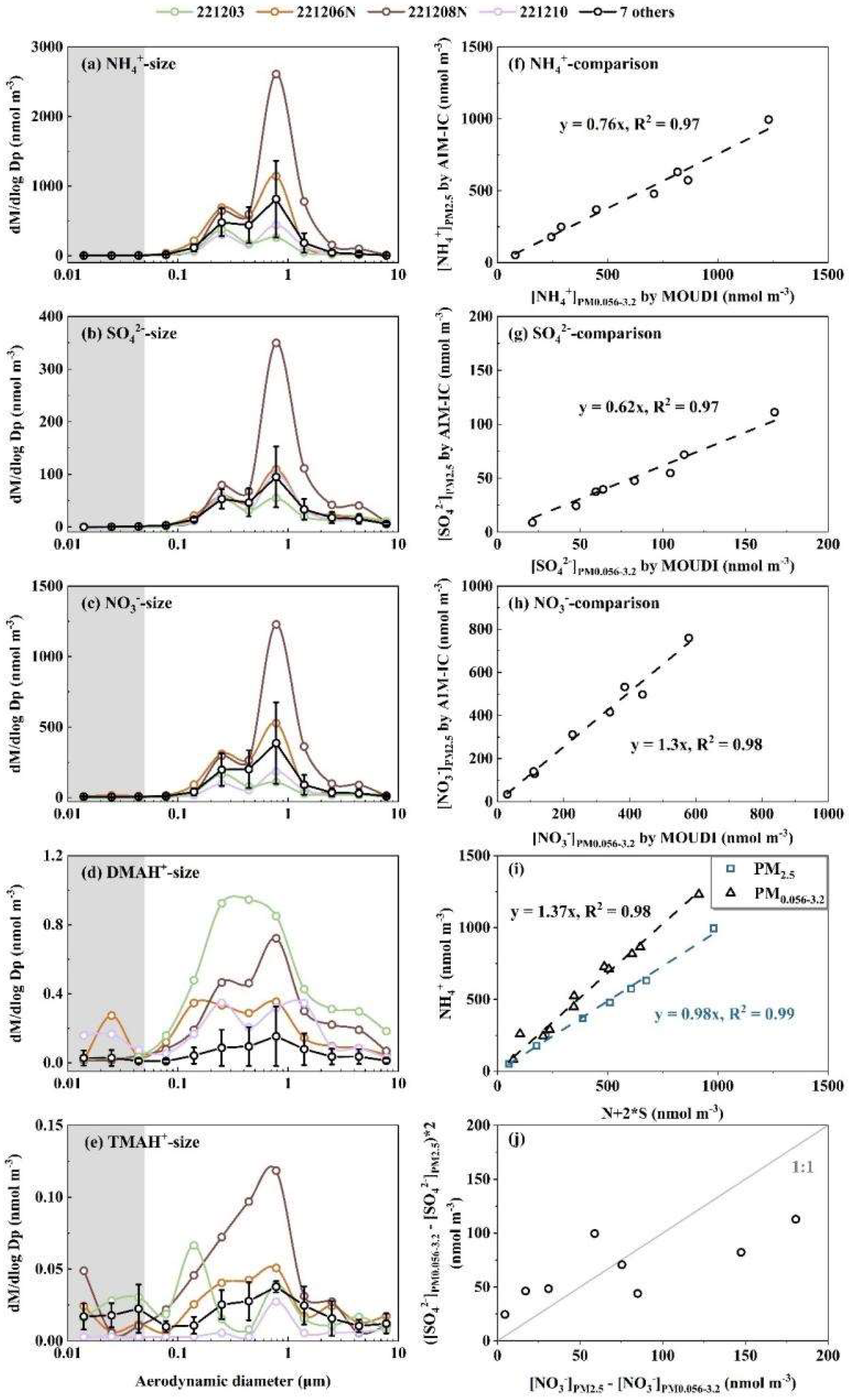

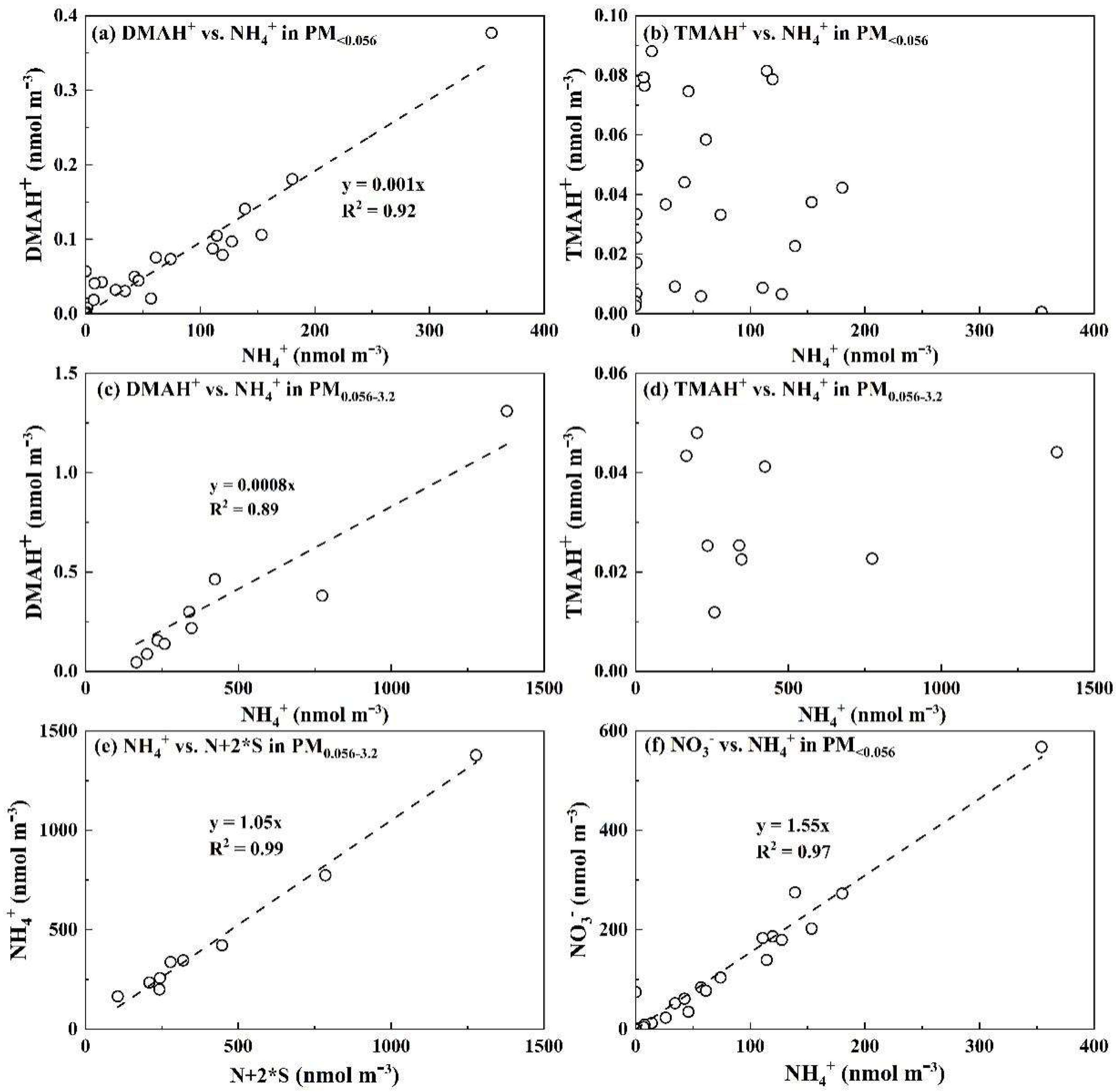

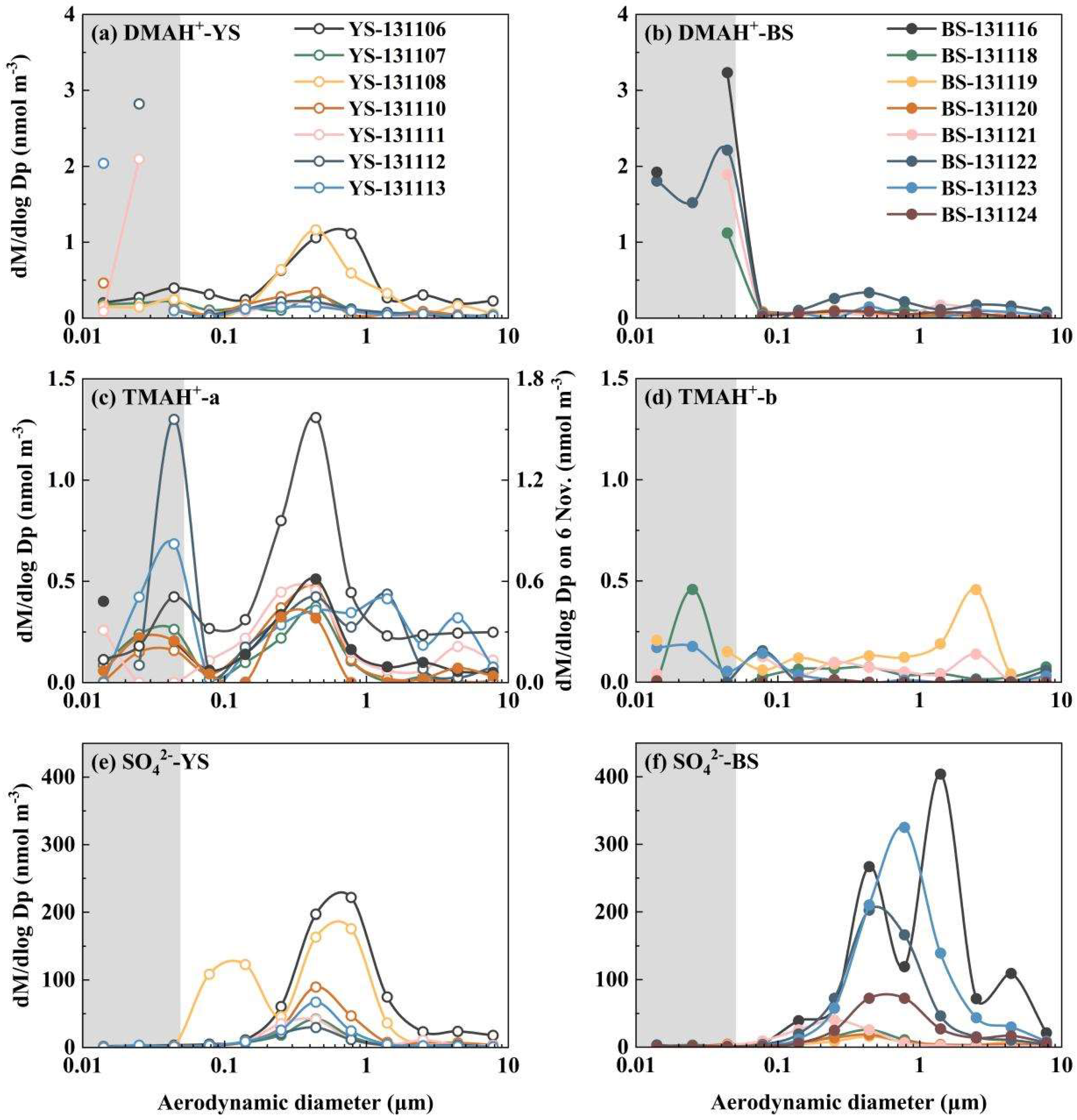

3.1. Molar Concentration Size Distributions of Particulate Ions and Inter-Comparison Between Nano-MOUDI and AIM-IC Measurements in the Coastal Atmosphere - Campaign 4

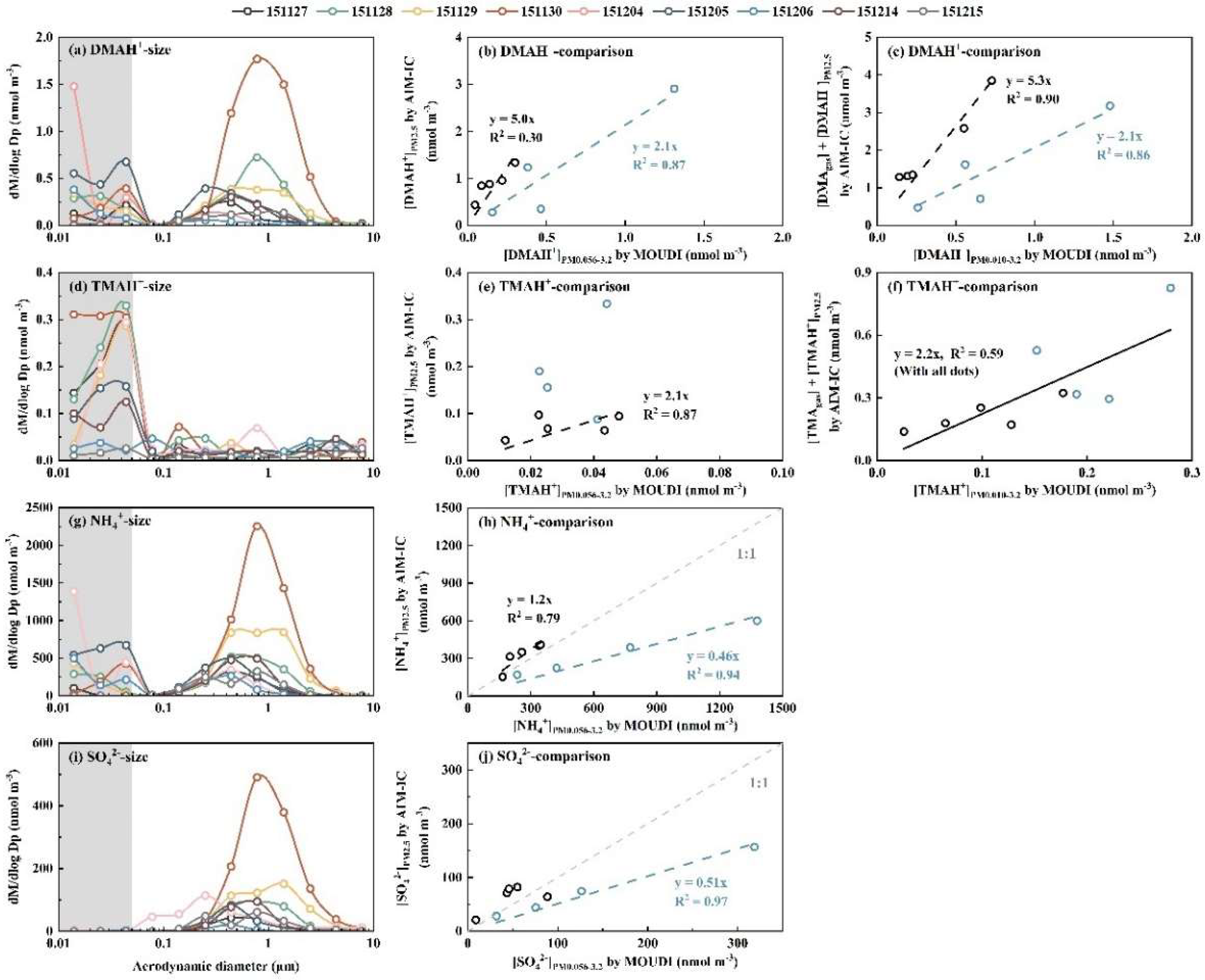

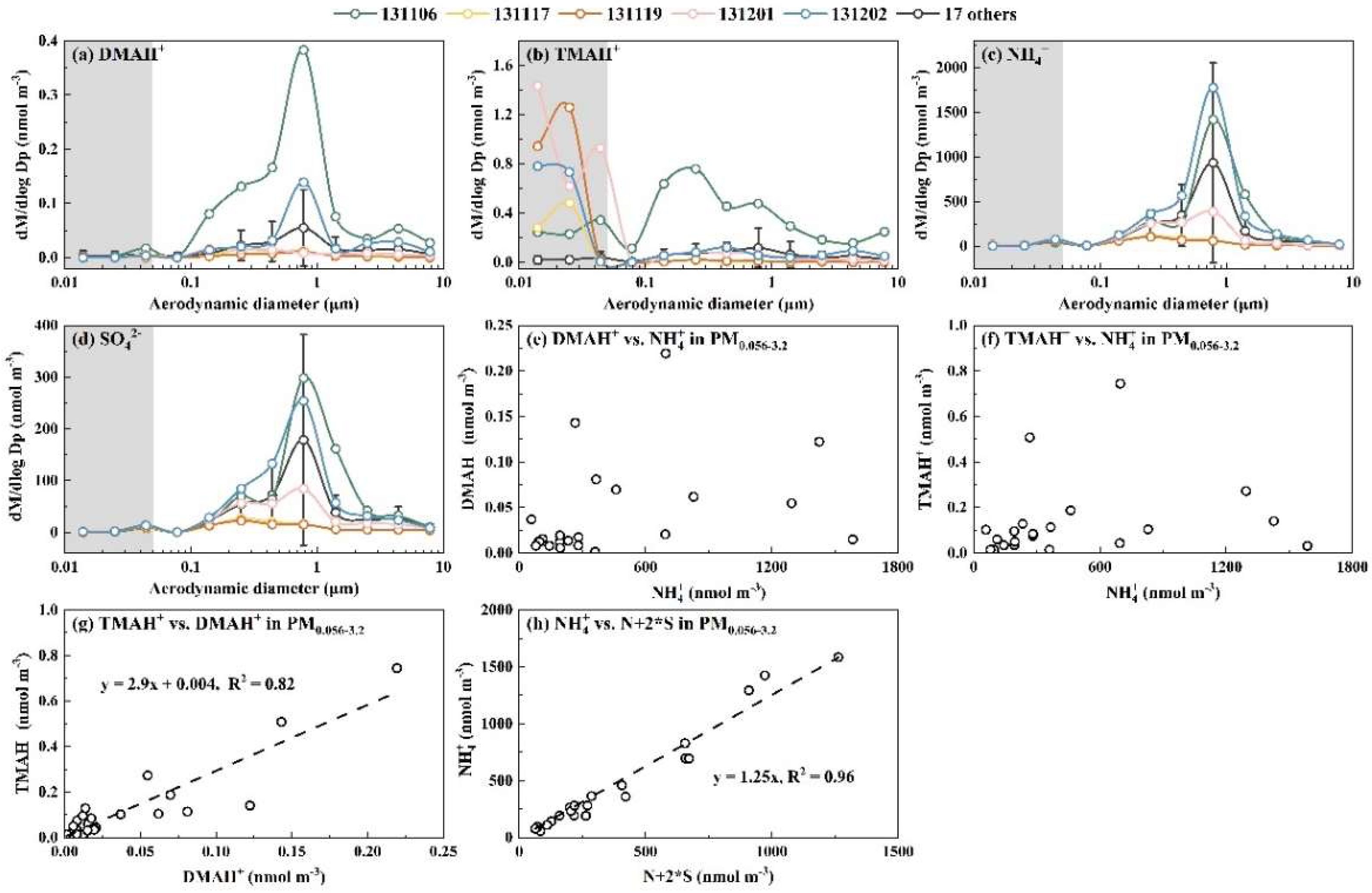

3.2. Molar Concentration Size Distributions of Particulate Ions and Comparison Between Nano-MOUDI-II and AIM-IC Measurements in the Coastal Atmosphere - Campaign 3

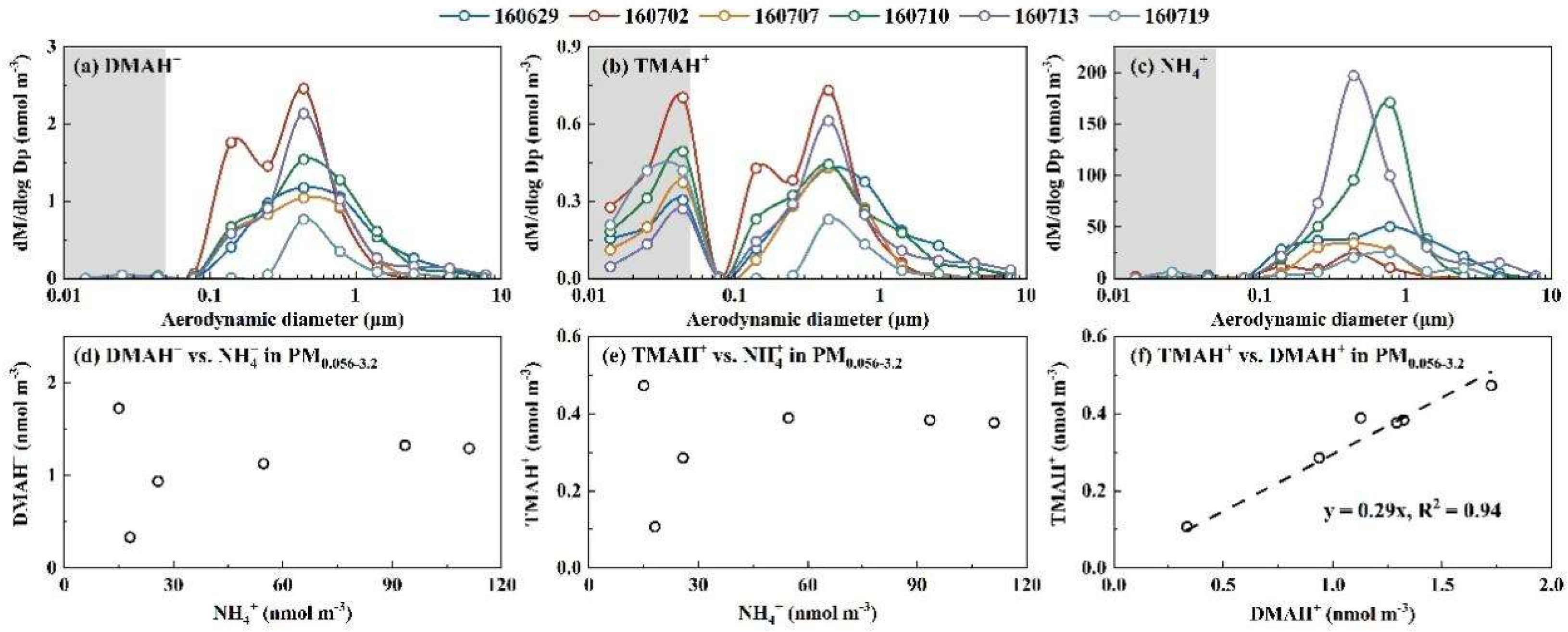

3.3. Molar Concentration Size Distributions of DMAH+ and TMAH+ During Comparative Campaigns

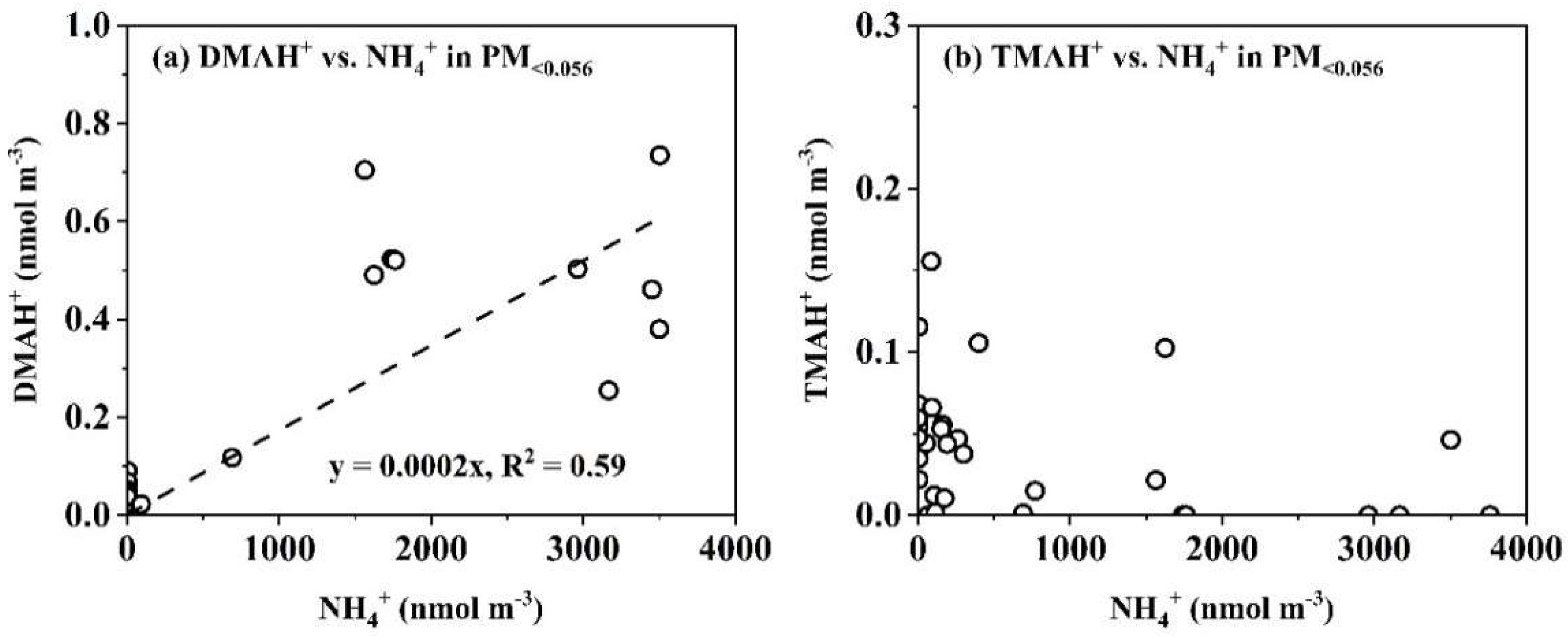

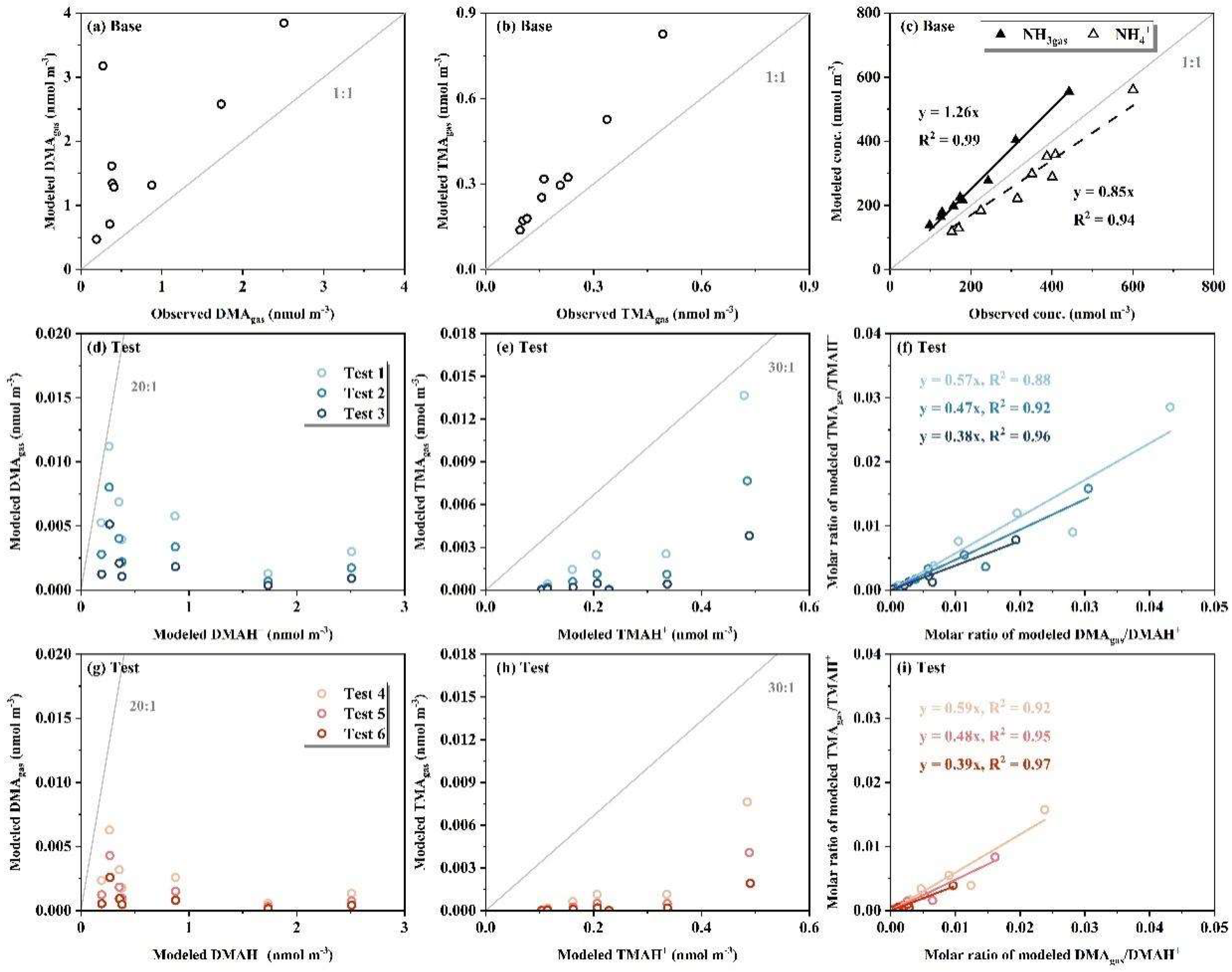

3.4. Repeatable Occurrence of E-DMAbelow0.056 and E-TMAbelow0.056 in Marine and Coastal Atmospheres

3.5. Cause Analysis for the More Frequent Observation of E-TMAbelow0.056 than E-DMAbelow0.056

3.6. Statistic Comparison of E-TMAbelow0.056 and E-DMAbelow0.056 Among Different Campaigns

4. Conclusion and Future Studies

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIM-IC | Ambient Ion Monitor – Ion Chromatograph |

| BS | the Bohai Sea |

| CCN | Cloud Condensation Nuclei |

| DMAgas/DMAH+ | gaseous/particulate dimethylamine |

| E-DMAbelow0.056/ E-TMAbelow0.056/ E-NH4+below0.056/ E-NO3-below0.056 | Elevated DMAH+/TMAH+/NH4+/NO3- concentrations in the size ranges below 0.056 μm compared to the size range of 0.056-0.10 μm |

| MMAD | Molar Median Aerodynamic Diameter |

| Nano MOUDI-II | Nano Micro-Orifice Uniform-Deposit Impactor, second generation |

| PM2.5 | Particulate matter with the aerodynamic diameter below 2.5 μm collected by AIM-IC |

| PM0.056-3.2/PM0.018-3.2/PM0.010-3.2/PM0.010-0.056/PM0.056-1.0 | Particulate matter with the aerodynamic diameter of 0.056-3.2/0.018-3.2/0.010-3.2/0.010-0.056/0.056-1.0 μm collected by Nano MOUDI-II |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| T | Temperature |

| TMAgas/TMAH+ | gaseous/particulate trimethylamine |

| YS | the Yellow Sea |

References

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric chemistry and physics: from air pollution to climate change, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, 2016; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.; Chakraborty, B.; Kumar, R.; Min, L. Recent advancement in organic aerosol understanding: a review of their sources, formation, and health impacts. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2023, 234, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahilang, M.; Deb, M.K.; Pervez, S. Biogenic secondary organic aerosols: a review on formation mechanism, analytical challenges and environmental impacts. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 127771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Hu, M.; Shang, D.; Wu, Z.; Du, Z.; Tan, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, R. Explosive secondary aerosol formation during severe haze in the North China Plain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2189–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Meng, H.; Yao, X.; Peng, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Feng, L.; Liu, X.; Gao, H. Does ambient secondary conversion or the prolonged fast conversion in combustion plumes cause severe PM₂.₅ air pollution in China? Atmosphere 2022, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.H. Introduction to perturbation methods, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, 2013; pp. 1–420. [Google Scholar]

- Dusek, U.; Frank, G.P.; Hildebrandt, L.; Curtius, J.; Schneider, J.; Walter, S.; Chand, D.; Drewnick, F.; Hings, S.; Jung, D.; Borrmann, S.; Andreae, M.O. Size matters more than chemistry for cloud-nucleating ability of aerosol particles. Science 2006, 312, 1375–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerminen, V.M.; Paramonov, M.; Anttila, T.; Riipinen, I.; Fountoukis, C.; Korhonen, H.; Asmi, E.; Laakso, L.; Lihavainen, H.; Swietlicki, E.; Svenningsson, B.; Asmi, A.; Pandis, S.N.; Kulmala, M.; Petäjä, T. Cloud condensation nuclei production associated with atmospheric nucleation: a synthesis based on existing literature and new results. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 12037–12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerminen, V.; Chen, X.; Vakkari, V.; Petäjä, T.; Kulmala, M.; Bianchi, F. Atmospheric new particle formation and growth: review of field observations. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.D.; Chuang, P.Y.; Feingold, G.; Jiang, H. Can aerosol decrease cloud lifetime? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.C.; Crippa, P.; Matsui, H.; Leung, L.R.; Zhao, C.; Thota, A.; Pryor, S.C. New particle formation leads to cloud dimming. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohy, C.H.; Petters, M.D.; Snider, J.R.; Stevens, B.; Tahnk, W.; Wetzel, M.; Russell, L.; Burnet, F. Evaluation of the aerosol indirect effect in marine stratocumulus clouds: droplet number, size, liquid water path, and radiative impact. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2005, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Shen, Y.; Yu, X.Y.; Gao, Y.; Gao, H.; Chu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, X. Investigating the contribution of grown new particles to cloud condensation nuclei with largely varying preexisting particles – Part 1: observational data analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 15325–15350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Luo, G.; Nair, A.A.; Schwab, J.J.; Sherman, J.P.; Zhang, Y. Wintertime new particle formation and its contribution to cloud condensation nuclei in the Northeastern United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 2591–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Hu, M.; Peng, J.; Wu, Z.; Zamora, M.L.; Shang, D.; Du, Z.; Zheng, J.; Fang, X.; Tang, R.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, L.; Shuai, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, J.; Gong, X.; Wang, C.; Molina, M.J.; Zhang, R. Remarkable nucleation and growth of ultrafine particles from vehicular exhaust. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 3427–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Feng, L.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, H.; Gao, Y.; Yao, X. Concentration and size distribution of water-extracted dimethylaminium and trimethylaminium in atmospheric particles during nine campaigns – implications for sources, phase states and formation pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Hu, Q.; Li, K.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, H.; Yao, X. Characteristics of dimethylaminium and trimethylaminium in atmospheric particles ranging from supermicron to nanometer sizes over eutrophic marginal seas of China and oligotrophic open oceans. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berndt, T.; Møller, K.H.; Herrmann, H.; Kjaergaard, H.G. Trimethylamine outruns terpenes and aromatics in atmospheric autoxidation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 4454–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.P.; Chan, C.K. Role of the aerosol phase state in ammonia/amines exchange reactions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5755–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yao, X.; Chan, C.K.; Tian, X.; Chu, Y.; Clegg, S.L.; Shen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Gao, H. Competitive uptake of dimethylamine and trimethylamine against ammonia on acidic particles in marine atmospheres. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 5430–5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Haan, D.O.; Hawkins, L.N.; Welsh, H.G.; Pednekar, R.; Casar, J.R.; Pennington, E.A.; de Loera, A.; Jimenez, N.G.; Symons, M.A.; Zauscher, M.; Pajunoja, A.; Caponi, L.; Cazaunau, M.; Formenti, P.; Gratien, A.; Pangui, E.; Doussin, J. Brown carbon production in ammonium- or amine-containing aerosol particles by reactive uptake of methylglyoxal and photolytic cloud cycling. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, 7458–7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, D.O.; Tapavicza, E.; Riva, M.; Cui, T.; Surratt, J.D.; Smith, A.C.; Jordan, M.; Nilakantan, S.; Almodovar, M.; Stewart, T.N.; de Loera, A.; De Haan, A.C.; Cazaunau, M.; Gratien, A.; Pangui, E.; Doussin, J. Nitrogen-containing, light-absorbing oligomers produced in aerosol particles exposed to methylglyoxal, photolysis, and cloud cycling. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52, 4061–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Bi, X.; Zhang, G.; Lian, X.; Fu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lin, Q.; Jiang, F.; Wang, X.; Peng, P.; Sheng, G. Gas-to-particle partitioning of atmospheric amines observed at a mountain site in southern China. Atmos Environ 2018, 195, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero-Ortiz, W.; Hu, M.; Du, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, S.; Lin, Y.; Gomez-Hermandez, M.; Peng, J.; Li, Y.; Secrest, J.; Zamora, M.L.; Wang, Y.; An, T.; Zhang, R. Formation and optical properties of brown carbon from small α-dicarbonyls and amines. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, K.H.; Berndt, T.; Kjaergaard, H.G. Atmospheric autoxidation of amines. Environ Sci Technol 2020, 54, 11087–11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, A.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Yu, F.; Du, L.; Ge, M.; Zhang, X. The critical role of dimethylamine in the rapid formation of iodic acid particles in marine areas. Npj Clim Atmos Sci 2022, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.J.; Clark, C.H.; Tang, X.; Cocker, D.R.; Purvis-Roberts, K.L.; Silva, P.J. Proposed chemical mechanisms leading to secondary organic aerosol in the reactions of aliphatic amines with hydroxyl and nitrate radicals. Atmos Environ 2014, 96, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Wang, L.; Lal, V.; Khalizov, A.F.; Zhang, R. Heterogeneous reactions of alkylamines with ammonium sulfate and ammonium bisulfate. Environ Sci Technol 2011, 45, 4748–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Elm, J.; Xie, H.; Chen, J.; Niu, J.; Vehkamäki, H. Structural effects of amines in enhancing methanesulfonic acid-driven new particle formation. Environ Sci Technol 2020, 54, 13498–13508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Chen, J.; Li, G.; An, T. A new advance in the pollution profile, transformation process, and contribution to aerosol formation and aging of atmospheric amines. Environmental Science: Atmospheres 2023, 3, 444–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.N.; Barsanti, K.C.; Friedli, H.R.; Ehn, M.; Kulmala, M.; Collins, D.R.; Scheckman, J.H.; Williams, B.J.; McMurry, P.H. Observations of aminium salts in atmospheric nanoparticles and possible climatic implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 6634–6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Lin, P.; Tan, T.; Li, M.; Xu, N.; Zheng, J.; Du, Z.; Qin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lu, S.; Song, Y.; Wu, Z.; Guo, S.; Zeng, L.; Huang, X.; He, L. Enhancement in particulate organic nitrogen and light absorption of humic-like substances over Tibetan Plateau due to long-range transported biomass burning emissions. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53, 14222–14232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Garmash, O.; Bianchi, F.; Zheng, J.; Yan, C.; Kontkanen, J.; Junninen, H.; Mazon, S.B.; Ehn, M.; Paasonen, P.; Sipilä, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Xiao, S.; Chen, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, D.; Fu, Q.; Geng, F.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Qiao, L.; Yang, X.; Chen, J.; Kerminen, V.; Petäjä, T.; Worsnop, D.R.; Kulmala, M.; Wang, L. Atmospheric new particle formation from sulfuric acid and amines in a Chinese megacity. Science 2018, 361, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhong, J.; Shi, Q.; Gao, L.; Ji, Y.; Li, G.; An, T.; Francisco, J.S. Mechanism for rapid conversion of amines to ammonium salts at the air–particle interface. J Am Chem Soc 2021, 143, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, R.; Yin, R.; Yan, C.; Yang, D.; Deng, C.; Dada, L.; Kangasluoma, J.; Kontkanen, J.; Halonen, R.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Paasonen, P.; Petäjä, T.; Kerminen, V.; Liu, Y.; Bianchi, F.; Zheng, J.; Wang, L.; Hao, J.; Smith, J.N.; Donahue, N.M.; Kulmala, M.; Worsnop, D.R.; Jiang, J. The missing base molecules in atmospheric acid–base nucleation. National Science Reviewnational Science Review 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Yan, C.; Cai, R.; Li, X.; Shen, J.; Lu, Y.; Schobesberger, S.; Fu, Y.; Deng, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Xie, H.; Bianchi, F.; Worsnop, D.R.; Kulmala, M.; Jiang, J. Acid–base clusters during atmospheric new particle formation in urban Beijing. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55, 10994–11005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Wexler, A.S.; Clegg, S.L. Atmospheric amines – Part I. A review. Atmos Environ 2011, 45, 524–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Wexler, A.S.; Clegg, S.L. Atmospheric amines – Part II. Thermodynamic properties and gas/particle partitioning. Atmos Environ 2011, 45, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankow, J.F. Phase considerations in the gas/particle partitioning of organic amines in the atmosphere. Atmos Environ 2015, 122, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Shen, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Gao, H.; Yao, X. Mapping gaseous dimethylamine, trimethylamine, ammonia, and their particulate counterparts in marine atmospheres of China's marginal seas – Part 1: Differentiating marine emission from continental transport. Atmos Chem Phys 2021, 21, 16413–16425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu Q, Qu K, Gao H, Cui Z, Gao Y, Yao X. Large increases in primary trimethylaminium and secondary dimethylaminium in atmospheric particles associated with cyclonic eddies in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 112–133, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng X, Hu Q, Zhang L, Qi J, Shi J, Xie H, Gao H, Yao X. Identification of major sources of atmospheric NH₃ in an urban environment in Northern China during wintertime. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6839–6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg SL, Kleeman MJ, Griffin RJ, Seinfeld JH. Effects of uncertainties in the thermodynamic properties of aerosol components in an air quality model – Part 1: Treatment of inorganic electrolytes and organic compounds in the condensed phase. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2008, 8, 1057–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, DG. An Introduction to Atmospheric Physics. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2010.

- Du W, Wang X, Yang F, Bai K, Wu C, Liu S, Wang F, Lv S, Chen Y, Wang J, Liu W, Wang L, Chen X, Wang G. Particulate amines in the background atmosphere of the Yangtze River Delta, China: Concentration, size distribution, and sources. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 38, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Bi X, Zhang G, Peng L, Lian X, Lu H, Fu Y, Wang X, Peng P, Sheng G. Concentration, size distribution and dry deposition of amines in atmospheric particles of urban Guangzhou, China. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 171, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandenBoer TC, Petroff A, Markovic MZ, Murphy JG. Size distribution of alkyl amines in continental particulate matter and their online detection in the gas and particle phase. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 4319–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov JM, Wexler AS. Where do particulate toxins reside? An improved paradigm for the structure and dynamics of the urban mid-Atlantic aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 2547–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai J, Lai W, Chiang H. Characteristics of particulate constituents and gas precursors during the episode and non-episode periods. J. Air Waste Manage. 2013, 63, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittelson, DB. Engines and nanoparticles: a review. J. Aerosol Sci. 1998, 29, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao X, Fang M, Chan CK, Ho KF, Lee S. Characterization of dicarboxylic acids in PM₂.₅ in Hong Kong. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao XH, Fang M, Chan CK. Experimental study of the sampling artifact of chloride depletion from collected sea salt aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao Y, Murphy JG. Evidence for the importance of semivolatile organic ammonium salts in ambient particulate matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehn M, Thornton JA, Kleist E, Sipilä M, Junninen H, Pullinen I, Springer M, Rubach F, Tillmann R, Lee B, Lopez-Hilfiker F, Andres S, Acir I, Rissanen M, Jokinen T, Schobesberger S, Kangasluoma J, Kontkanen J, Nieminen T, Kurtén T, Nielsen LB, Jørgensen S, Kjaergaard HG, Canagaratna M, Maso MD, Berndt T, Petäjä T, Wahner A, Kerminen V, Kulmala M, Worsnop DR, Wildt J, Mentel TF. A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol. Nature 2014, 506, 476–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan CK, Yao X. Air pollution in mega cities in China. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang L, Tsai J, Chang K, Lin JJ. Water-soluble inorganic ions in airborne particulates from the nano to coarse mode: a case study of aerosol episodes in southern region of Taiwan. Environ. Geochem. Hlth 2008, 30, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei X, Zhu Y, Gao Y, Gao H, Yao X. Statistical analysis and environmental impact of pre-existing particle growth events in a Northern Chinese coastal megacity: A 725-day study in 2010–2018. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 933, 173227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Shen Y, Li K, Meng H, Sun Y, Yao X, Gao H, Xue L, Wang W. Investigation of particle number concentrations and new particle formation with largely reduced air pollutant emissions at a coastal semi-urban site in Northern China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2021, 126, e2021JD035419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Campaigns | Levels | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level-0 | Level-1 | Level-2 | Level-3 | Level-4 | |||

| DMAH+ | Campaign 1 | 12/13* | 1/13 | - | - | - | |

| Campaign 2 | 20/22 | 1/22 | - | 1/22 | - | ||

| Campaign 3 | 3/9 | - | 3/9 | 1/9 | 2/9 | ||

| Campaign 4 | 9/11 | 2/11 | - | - | - | ||

| Campaign 5 | Phase 1# | 6/7 | - | 1/7 | - | - | |

| Phase 2 | - | 1/7 | 5/7 | 1/7 | - | ||

| Campaign 6 | Phase 1& | - | 2/7 | 2/7 | - | 3/7 | |

| Phase 2 | 4/8 | 1/8 | - | - | 3/8 | ||

| Campaign 7 | 6/6 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Total | 60/90 | 8/90 | 11/90 | 3/90 | 8/90 | ||

| TMAH+ | Campaign 1 | 4/13 | 5/13 | 3/13 | 1/13 | - | |

| Campaign 2 | 11/22 | 4/22 | 1/22 | 2/22 | 4/22 | ||

| Campaign 3 | - | - | 2/9 | 1/9 | 6/9 | ||

| Campaign 4 | 2/11 | 2/11 | 7/11 | - | - | ||

| Campaign 5 | Phase 1 | - | 4/7 | 3/7 | - | - | |

| Phase 2 | 3/7 | - | 1/7 | 3/7 | - | ||

| Campaign 6 | Phase 1 | 1/7 | 3/7 | 3/7 | - | - | |

| Phase 2 | 2/8 | 1/8 | 3/8 | 2/8 | - | ||

| Campaign 7 | - | 1/6 | 4/6 | - | 1/6 | ||

| Total | 23/90 | 20/90 | 27/90 | 9/90 | 11/90 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).