1. Introduction

Lithium ion batteries (LIBs) are state of the art of power supply for numerous applications ranging from hand-held consumer electronics through electric vehicles to stationary energy storage systems. The batteries consist of two electrodes (negative and positive), and a separator which is wetted with an organic electrolyte. The electrodes contain the active material, conductive agent(s), and binder(s). All these components are solids, thus a processing solvent is needed to mix and coat them onto a current collector. For positive electrodes, the most-used solvent is

N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. NMP however is problematic for human health: NMP is classified as irritant to the skin, eye, and respiratory system. The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) classified NMP as toxic for reproduction [

7] in 2011. In 2018, the European Commission released a commission regulation [

8] which added NMP to regulation 1907/2006, which describes the registration, evaluation, authorization and restriction of chemicals, commonly known as REACH [

9]. A limit value of 14.4 mg/m³ for inhalation was defined as D

erived No-Effect Level (DNEL). The DNEL describes a concentration below which no effect to human health is to be expected. A study by Bader et al. from 2006 in a glue production facility using NMP revealed expositions higher than 14.4 mg/m³ [

10]. This raises the question if the usage of NMP during the coating of greater amounts of positive electrodes causes exceedance of the limit values. To answer this question, a method using thermal desorption (TD) coupled to gas chromatography – mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was developed. TD-GC-MS is a standard method for the quantification of air contamination, as described in DIN EN ISO 16000 and DIN EN ISO 16017 [

11,

12,

13]. The method described in the following was developed accordingly to these standards. Relevant deviations are mentioned where applicable. The applied technique is also often referred to as “Adsorption – Thermal Desorption – GC-MS” [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The working principle is based on the adsorption of contaminants in air on sorbent materials. Air samples are drawn through tubes made of metal or glass containing adsorbent materials like Tenax TA. Contaminants will adsorb at room temperature, be desorbed at elevated temperatures within the TD unit and transferred onto an analysis system like GC-MS. Tenax TA is a widely used material for the analysis of C7 to C26 hydrocarbons [

18]. The goal was to quantify NMP even at high concentrations up to 100 mg/m³. The challenge is the robustness / tolerance of the mass spectrometer towards high amounts of analyte. The obvious choice would be a reduction of the sampling volume since the total amount of analyte sampled onto the sampling tube is the product of analyte concentration in air and the sampled volume. However, the sampling volume cannot be reduced indefinitely. The smaller the sampling volume, the higher is the influence of short-period deviations and the worse is the limit of detection (LOD). However, the LOD is rather negligible in this case since the target is the determination of concentrations near DNEL. Therefore, analytical method and sampling strategy must be adapted to each other. A typical sampling volume of 1 L (at 100 mL/min for 10 min) was chosen as a target. Therefore, GC-MS must tolerate and quantify up to 100 µg of NMP on the sampling tube. Depending on the expected concentration, the sampling volume could easily be increased, but additional measures must be taken to ensure that no analyte has broken through the tube.

2. Experimental

2.1 Chemicals

NMP 99.5 % was supplied by VWR (Radnor, United States). Methanol (LiChrosolv gradient grade for liquid chromatography) was supplied by Supelco (St. Louis, USA). Helium 5.0 and Nitrogen 4.6 were supplied by Westfalengas (Münster, Germany).

2.2. TD-GC-MS

The GC-MS (QP-2010 Ultra, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was coupled to the thermal desorption system TD30R (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). For separation of analytes a Rxi 5ms column (30 m x 0.25 mm x 0.50 µm) by Restek (Bellefonte, United States) was chosen, due to its increased film thickness for higher analyte capacity. TD tubes filled with Tenax TA (60/80 mesh) were supplied by Supelco (St. Louis, United States). The GC oven program started at 100 °C held for 2 min and ramped up to 220 °C with a rate of 20 °C/min and held for 1 minute. Column flow (He 5.0) was controlled by linear velocity of 40 cm/s resulting in a column flow of 1.2 mL/min. A split ratio of 1:100 resulted in a total flow of 119.8 mL/min including 3 mL/min purge flow. The temperature of the ion source was set to 200 °C and the interface to 250 °C. Event time was set to 0.3 s. Detector voltage was set -0.2 kV relative to tuning to prevent detector saturation at higher amounts of NMP during measurements. A combination of scan and single ion monitoring was used for high sensitivity for NMP while retaining identification of possible side contaminants. Scan range was set to mass to charge ratios 40-300 while the fragment with m/z 99 (M+) was used for quantification while the fragments with m/z 98 and 44 (69.48 % and 56.44 % respectively) were used as qualifiers (tolerated deviation 30 %). NMP eluted at 4.4 min. Final parameters for thermal desorption were 230 °C desorption temperature for 7 min at 70 mL/min. Each sample was pre-purged for 1 min at 20 mL/min. Trap cold temperature was -10 °C while the trap desorption temperature was 250 °C for 5 min. Joint, valve and transfer line temperature were 230 °C.

2.3. Calibration

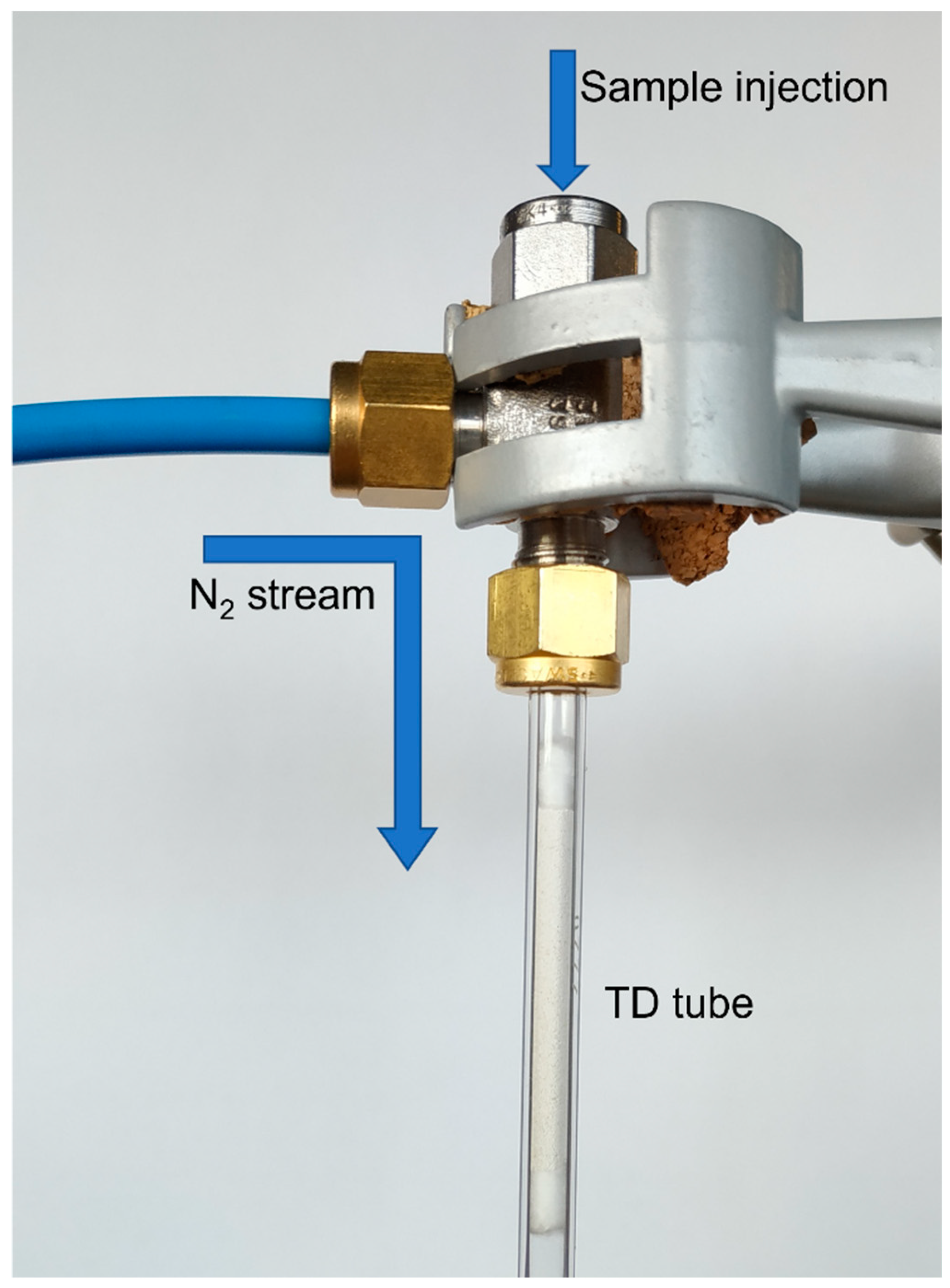

Standards of NMP were added to the TD tubes in a liquid solution of methanol. Methanol shows little retention on Tenax TA [

19]. For the addition of 10 µL standard solution, a T-piece was used (

Figure 1). Nitrogen with a flow of 50 mL/min (to support loading of standard solutions) was introduced from the side continuing for 5 min after injection. The TD tube was fixed on the bottom part of the T-piece while the top part was equipped with a septum. The solution was injected into the nitrogen flow directly onto the TD tube. After injection, the tube was purged for another 5 minutes. Laboratory air samples were taken with a GilAir Plus sampling pump by Sensidyne (St. Petersburg, United States) at a flow rate of 100 mL/min for 10 min. The sampling pump was calibrated with a 7000 GC flowmeter by Ellutia (Ely, United Kingdom).

3. Results & Discussion

For quantitative analysis it must be ensured, that the adsorption of NMP on Tenax TA is also quantitative, i.e.

, that there is no breakthrough. To determine the breakthrough volume, the DIN EN ISO 16017 suggests a gas stream containing the analyte passing through an adsorbent tube until the measured peak correlates to 5 % of the initial concentration before the tube [

13]. The setup for this method is not trivial to realize with a standard TD system, so the breakthrough and resulting safe sampling volume was determined according to US EPA method TO-17 [

20]. Therefore, two TD tubes were connected in series and sampling was performed in an atmosphere, that contained NMP. Several different volumes were sampled. If the intensity of NMP on the second tube in the sampling path (backup-tube) is greater than 5 % than on the first tube in the sampling path (challenge tube), breakthrough has happened. Breakthrough volume was checked up until 5 L of sampling volume, since this would result in a much larger safe sampling volume than the actual desired sampling volume of 1 L. The results are shown in

Table 1. The breakthrough volume is greater than 5 L and the safe sampling volume (⅔ of breakthrough volume) is therefore greater than 3.3 L.

The next step is the evaluation and optimization of the desorption parameters, i.e., temperature, flow, and duration. To confirm, that 230 °C is sufficient as desorption temperature (bp

NMP = 202 °C) the completeness of desorption was evaluated. Therefore, the tubes were loaded with 100 µg of NMP and desorbed at 230 °C. The tubes were then desorbed a second time at 230 °C, 250 °C and 280 °C. The data (

Table 2) shows, that there is always a small rest that cannot be desorbed in the first run. A desorption temperature of 230 °C was chosen nevertheless since the gain in desorption efficiency does not compensate for the increased deterioration of the sorbent material at higher temperatures.

Furthermore, the influences of desorption duration and desorption flow were evaluated in a similar way. This correlates to the term retention volume, i.e., the volume of He that is needed for a peak maximum. The tubes were loaded with 100 µg of NMP and then desorbed at 230 °C for either 5 minutes at a flow rate of 50 mL/min (resulting in a total of 250 mL He) or 7 minutes at a flow rate of 70 mL/min (490 mL of He). All tubes were then desorbed a second time at 70 mL/min for 7 minutes.

Table 3 shows, that the residual amount of NMP is reduced, if 70 mL/min for 7 min is chosen for the first desorption. Higher flow rates / durations were not tested since the desorption efficiency was sufficient. At these conditions, the residual amount of NMP is identical to the amount in the temperature evaluation. The desorption of NMP is rather dependent on higher flow rates / duration than on temperature (once reaching 230 °C).

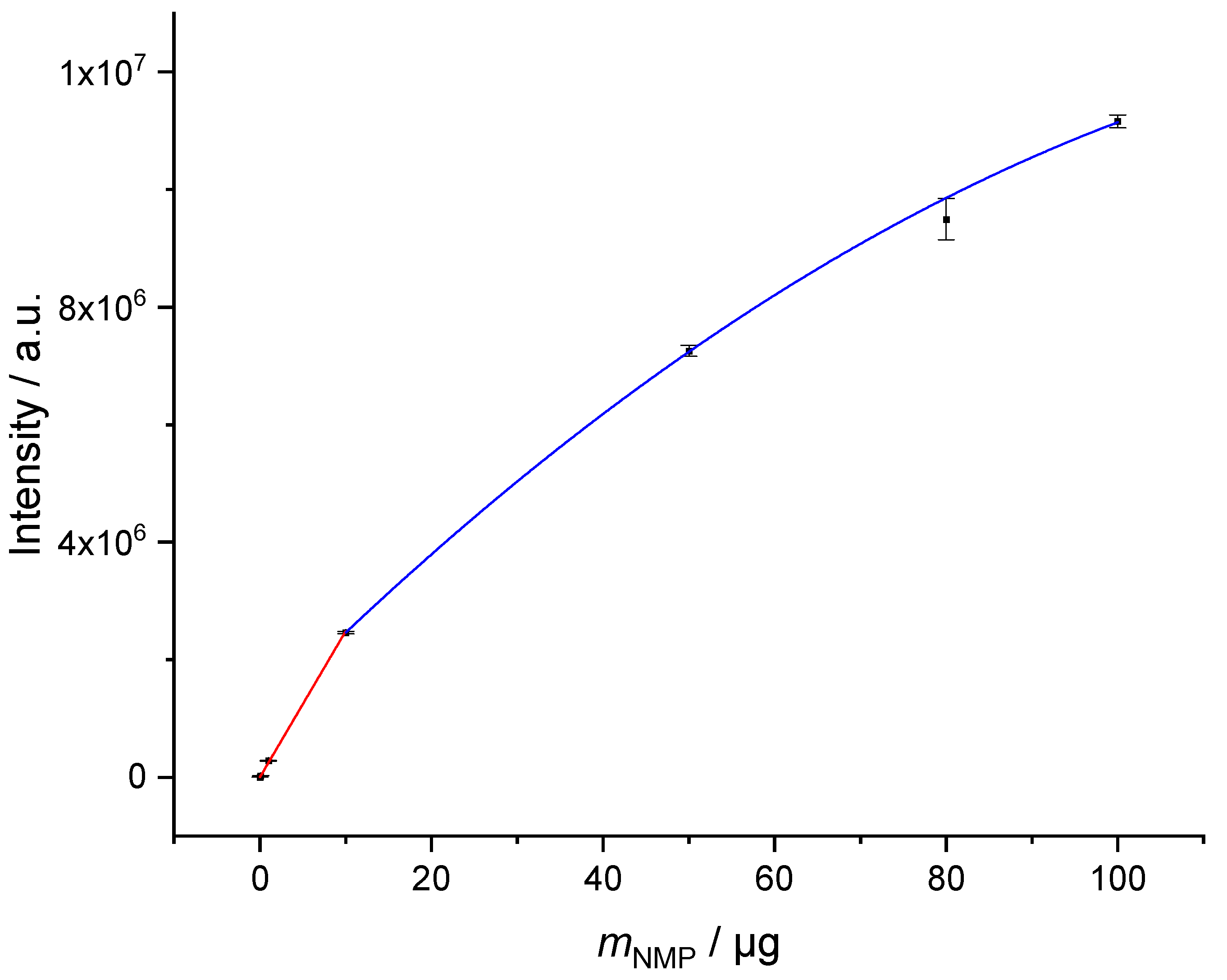

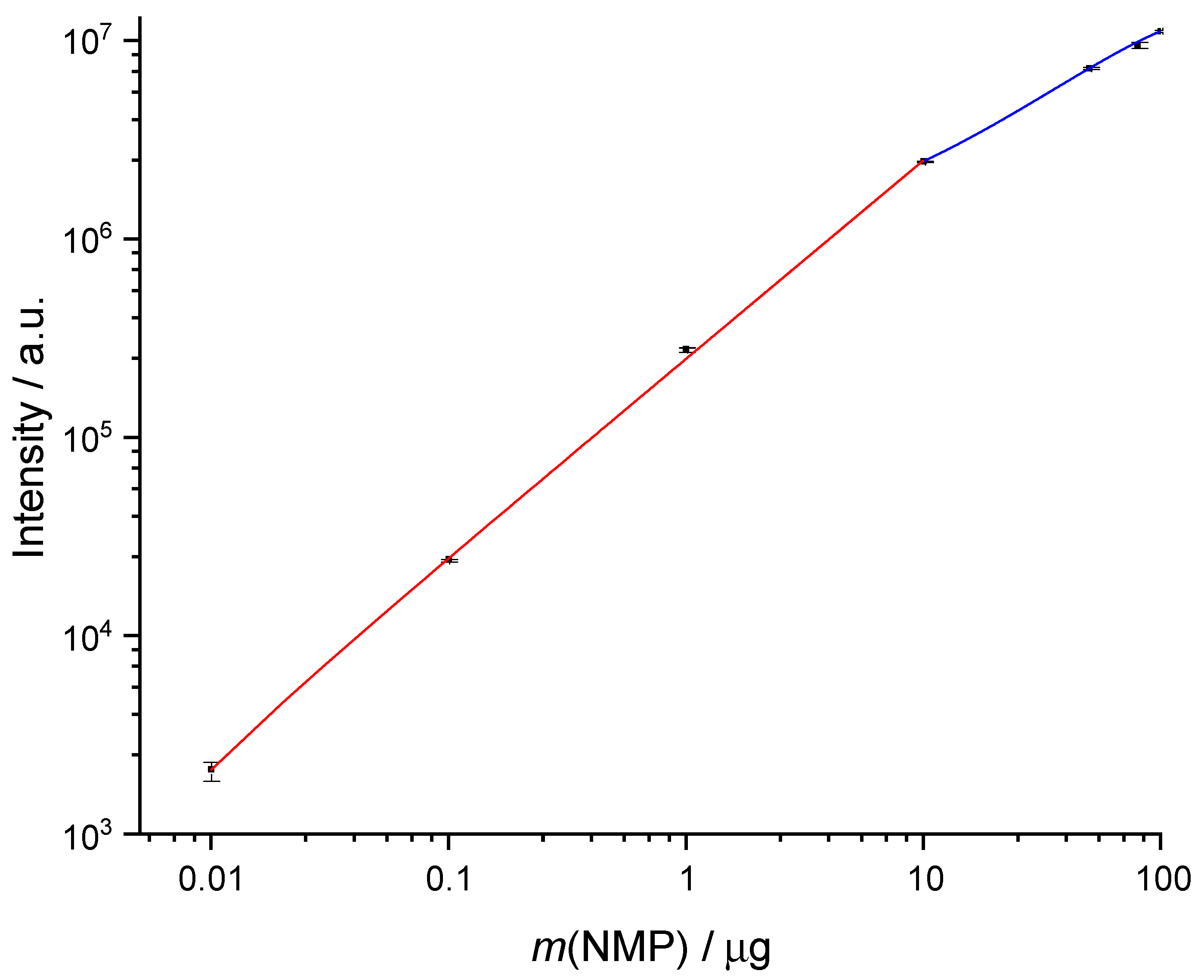

The linear range and working range of the method were determined by means of an 8-point calibration. The calibration ranged from 1 ng (on tube) to 100 µg (on tube). Each calibration point was measured three times.

No detector saturation was found up to 100 µg of NMP on tube due to the reduction of detector voltage of -0.2 kV.

Table 4 shows, that the relative standard deviation (RSD) is low between 100 ng and 100 µg with less than 4 %. At 10 ng the RSD is 11 %, and although the signal-to-noise ratio is much higher than 10 at this point, 10 ng was chosen as limit of quantification. Logarithmic plotting of the calibration shows the linear range quite well (

Figure 3) with R² = 0.99879. The linear range extends over 3 decades from 10 ng to 10 µg of NMP on the tube. Above 10 µg the signal response is no longer linear (easier to see in

Figure 2). However, the behavior can be represented quite well by a quadratic function with R² = 0.99987. This range should be avoided for quantification, but in cases where the sampling volume cannot be reduced further, it can be used as semi-quantitative determination of the concentration. It should be noted, that at a sampling volume of 1 L of air 14.4 µg marks the DNEL. Any higher signal in this intensity range means an exceedance of the threshold. Increasing the split ratio to 1:200 would allow quantification up to DNEL in the linear range of calibration. This might be a consideration when many measurements of atmospheres with contaminations near DNEL are planned and a further reduction of sampling volume is impossible.

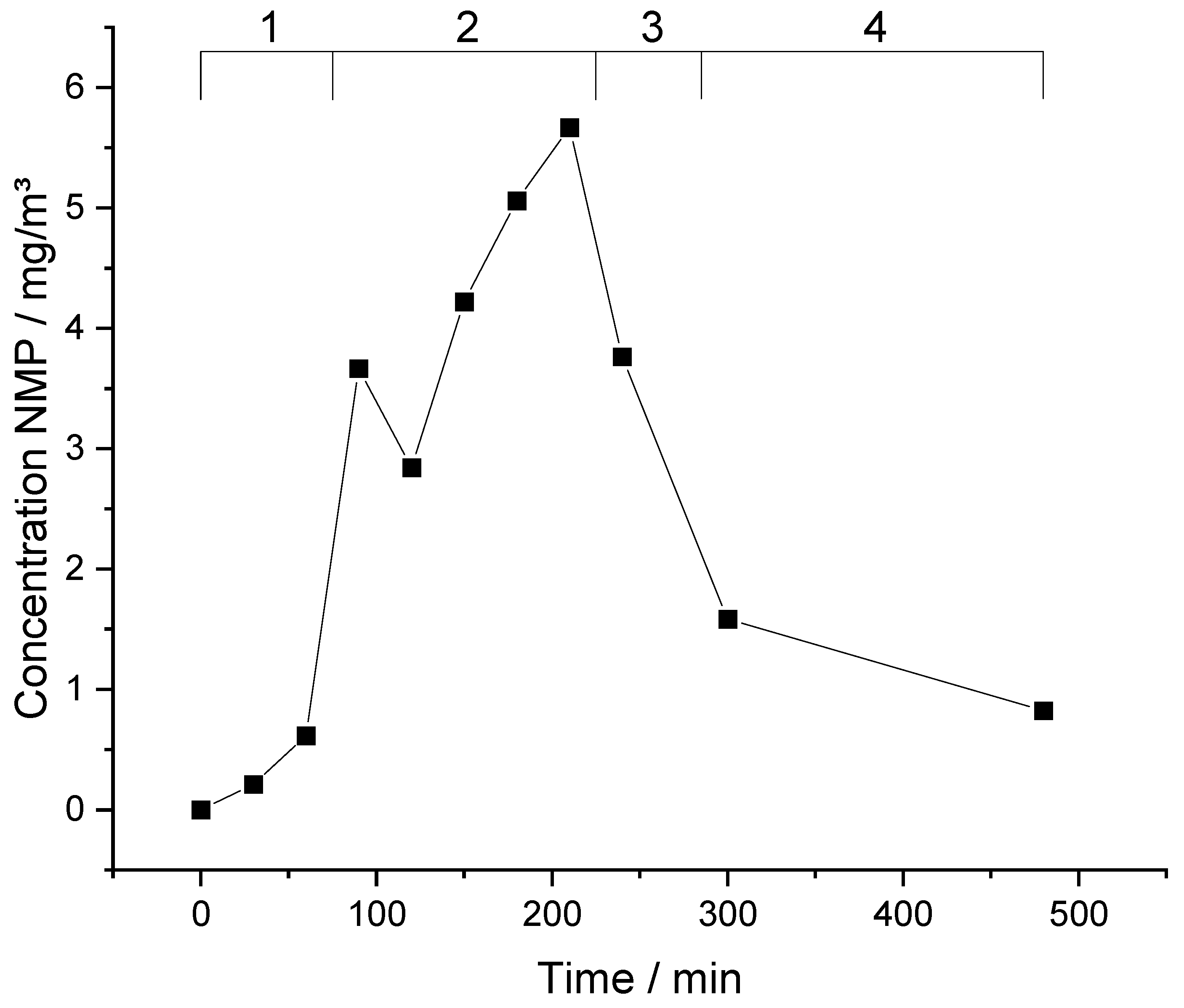

The developed method was used to evaluate the NMP contamination of laboratory air during semi-automated coating of lithium ion battery electrodes. The measurements were conducted in 90 cm distance to the coating line. This distance resembles the typical working distance. Measurements were taken before the coating and during the coating in 30 min intervals. Also, two data points were acquired after completion of the coating process to investigate the decrease of the NMP contamination after the work is finished.

The contamination of laboratory air with NMP is presented graphically in

Figure 4. First; the DNEL of 14.4 mg/m³ is never reached. The concentration is rising slowly during the first production step. The production rate of electrodes in this step is quite low and so the contamination of NMP rises slowly. Already 25 min after an increase of the production rate; the contamination rises drastically to about 3.6 mg/m³. A short break becomes noticeable in a drop in concentration shortly after beginning of regime 2 in

Figure 4. Afterwards; the concentration of NMP keeps rising constantly during the coating process. Regime 3 represents the cleaning phase after the actual coating process. After completion of the coating process the concentration of NMP is decreasing again. The graph also shows that it takes more than four hours after the completion of the coating to reach previous levels before the coating process. Even four hours after ending of all coating works there is a significant contamination measurable.

4. Conclusions

A method was developed, that is capable of quantifying NMP contaminations in laboratory air. The linear range extends from 10 ng up to 10 µg of NMP on the sampling tube (3 decades), which corresponds to 10 µg/m³ - 10 mg/m³ at 1 L sampling volume. The working range extends up 100 µg (4 decades) and therefore 100 mg/m³ at 1 L sampling volume. Desorption parameters were optimized to 230 °C and 70 mL/min for 7 minutes resulting in a desorption efficiency of 99.9 %. Breakthrough of NMP does not happen under at least 5 L of sampling volume. TD-GC-MS is a quick, sustainable, and reliable technique for the quantification of indoor air contaminations. The sampling process is fast and easy (10 min per sample). No solvents are necessary except for the calibration standards. This is beneficial for reproducibility since there are no possible losses during liquid extraction. This results in a very good reproducibility of about 4 %.

Application of the method confirmed, that NMP contamination of laboratory air during coating of lithium ion battery electrolytes in this case study falls under the threshold of 14.4 mg/m ³. During low production rate phases, the contamination also rises slowly. Higher production rates and pauses are noticeable in quick changes of the contamination degree. It takes several hours for the contamination to go down to levels that were present before the start of the coating. Other circumstances and coating conditions may lead to different results. Batch size, ventilation / hoods, ambient pressure and temperature may affect local concentrations of NMP in ambient air and therefore its concentration should be monitored regularly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Sung, S.H.; Kim, S.; Park, J.H.; Park, J.D.; Ahn, K.H. Role of PVDF in Rheology and Microstructure of NCM Cathode Slurries for Lithium-Ion Battery. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, W.; Nötzel, D. Rheological properties and stability of NMP based cathode slurries for lithium ion batteries. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 4591–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Dong, X.; Escobar, I.C.; Cheng, Y.-T. Lithium Ion Battery Electrodes Made Using Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO)—A Green Solvent. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 11046–11051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Nelson, P.A.; Gallagher, K.G.; Dees, D.W. Energy impact of cathode drying and solvent recovery during lithium-ion battery manufacturing. J. Power Sources 2016, 322, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Current and future lithium-ion battery manufacturing. iScience 2021, 24, 102332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dühnen, S.; Betz, J.; Kolek, M.; Schmuch, R.; Winter, M.; Placke, T. Toward Green Battery Cells: Perspective on Materials and Technologies. Small Methods 2020, 4, 2000039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukka Malm. Candidate List of substances of very high concern for Authorisation. https://echa.europa.eu/candidate-list-table/-/dislist/details/0b0236e1807da281. (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) 2018/588 of 18 April 2018 amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidone. In Official Journal of the European Union, 2018.

- REGULATION (EC) No 1907/2006 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), establishing a European Chemicals Agency, amending Directive 1999/45/EC and repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 793/93 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 as well as Council Directive 76/769/EEC and Commission Directives 91/155/EEC, 93/67/EEC, 93/105/EC and 2000/21/EC, 2006.

- Bader, M.; Rosenberger, W.; Rebe, T.; Keener, S.A.; Brock, T.H.; Hemmerling, H.-J.; Wrbitzky, R. Ambient monitoring and biomonitoring of workers exposed to N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone in an industrial facility. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2006, 79, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DIN EN ISO 16000-1:2006-06, Indoor air - Part 1: General aspects of sampling strategy (ISO 16000-1:2004); German version EN ISO 16000-1:2006; Beuth Verlag GmbH, Berlin.

- DIN EN ISO 16000-5:2007-05, Indoor air - Part 5: Sampling strategy for volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (ISO 16000-5:2007); German version EN ISO 16000-5:2007; Beuth Verlag GmbH, Berlin.

- DIN EN ISO 16017-1:2001-10, Indoor, ambient and workplace air - Sampling and analysis of volatile organic compounds by sorbent tube/thermal desorption/capillary gas chromatography - Part 1: Pumped sampling (ISO 16017-1:2000); German version EN ISO 16017-1:2000; Beuth Verlag GmbH, Berlin.

- Wu, C.-H.; Feng, C.-T.; Lo, Y.-S.; Lin, T.-Y.; Lo, J.-G. Determination of volatile organic compounds in workplace air by multisorbent adsorption/thermal desorption-GC/MS. Chemosphere 2004, 56, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clément, M.; Arzel, S.; Le Bot, B.; Seux, R.; Millet, M. Adsorption/thermal desorption-GC/MS for the analysis of pesticides in the atmosphere. Chemosphere 2000, 40, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankow, J.F.; Luo, W.; Isabelle, L.M.; Bender, D.A.; Baker, R.J. Determination of a Wide Range of Volatile Organic Compounds in Ambient Air Using Multisorbent Adsorption/Thermal Desorption and Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1998, 70, 5213–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.C.; Vainer, L.; Martin, J.W.; Williams, D.T. Determination of organic contaminants in residential indoor air using an adsorption-thermal desorption technique. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1990, 40, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettmer, K.; Engewald, W. Adsorbent materials commonly used in air analysis for adsorptive enrichment and thermal desorption of volatile organic compounds. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2002, 373, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, I.; Fieber, M. Retention characteristics of volatile compounds on tenax TA. J. High Resol. Chromatogr. 1988, 11, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Compendium Method TO-17:Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds in Ambient Air Using Active Sampling Onto Sorbent Tubes, 1999. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-11/documents/to-17r.pdf. (accessed on 28 February 2022).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).