Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Affective Computing

1.2. Multi-Source Affective Computing

1.3. Rural Visual Landscape Quality Assessment

1.4. Summary of Relevant Research

2. Materials and Methods

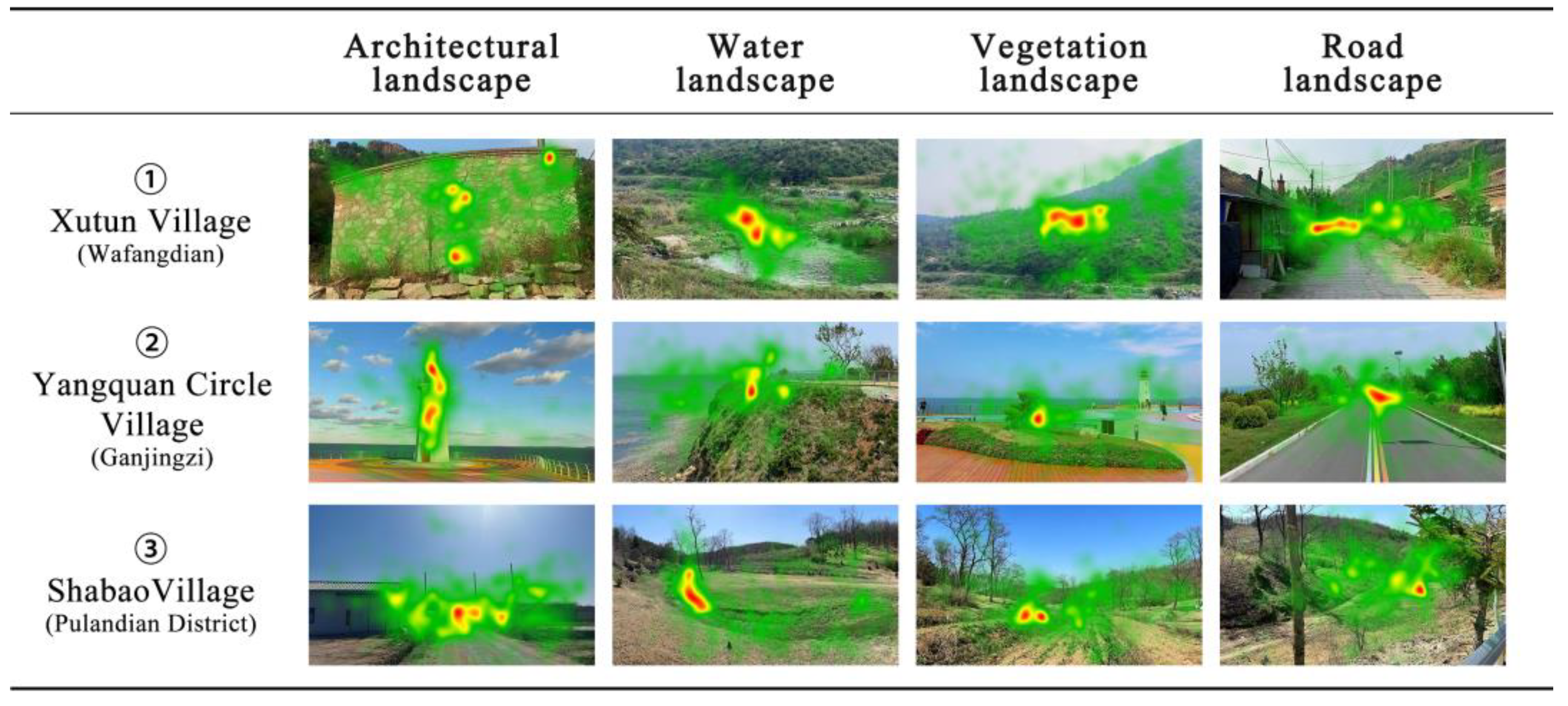

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Experimental Elements

2.2.1. Element Presentation

2.2.2. Experimental Subjects

2.2.3. Experimental Equipment and Questionnaire

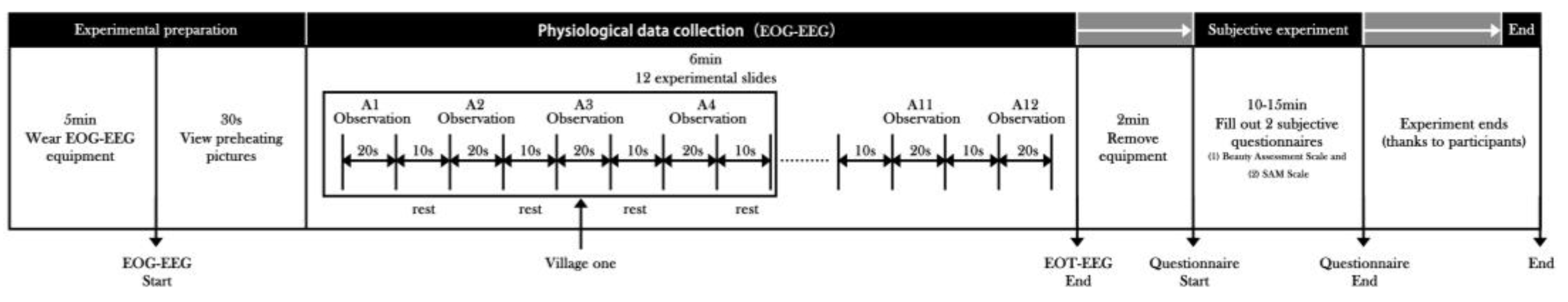

2.2.4. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Data Processing

2.3.1. Eye Movement Data Preprocessing

2.3.2. EEG Data Preprocessing

2.3.3. Pre-Processing of Scenic View Evaluation Data

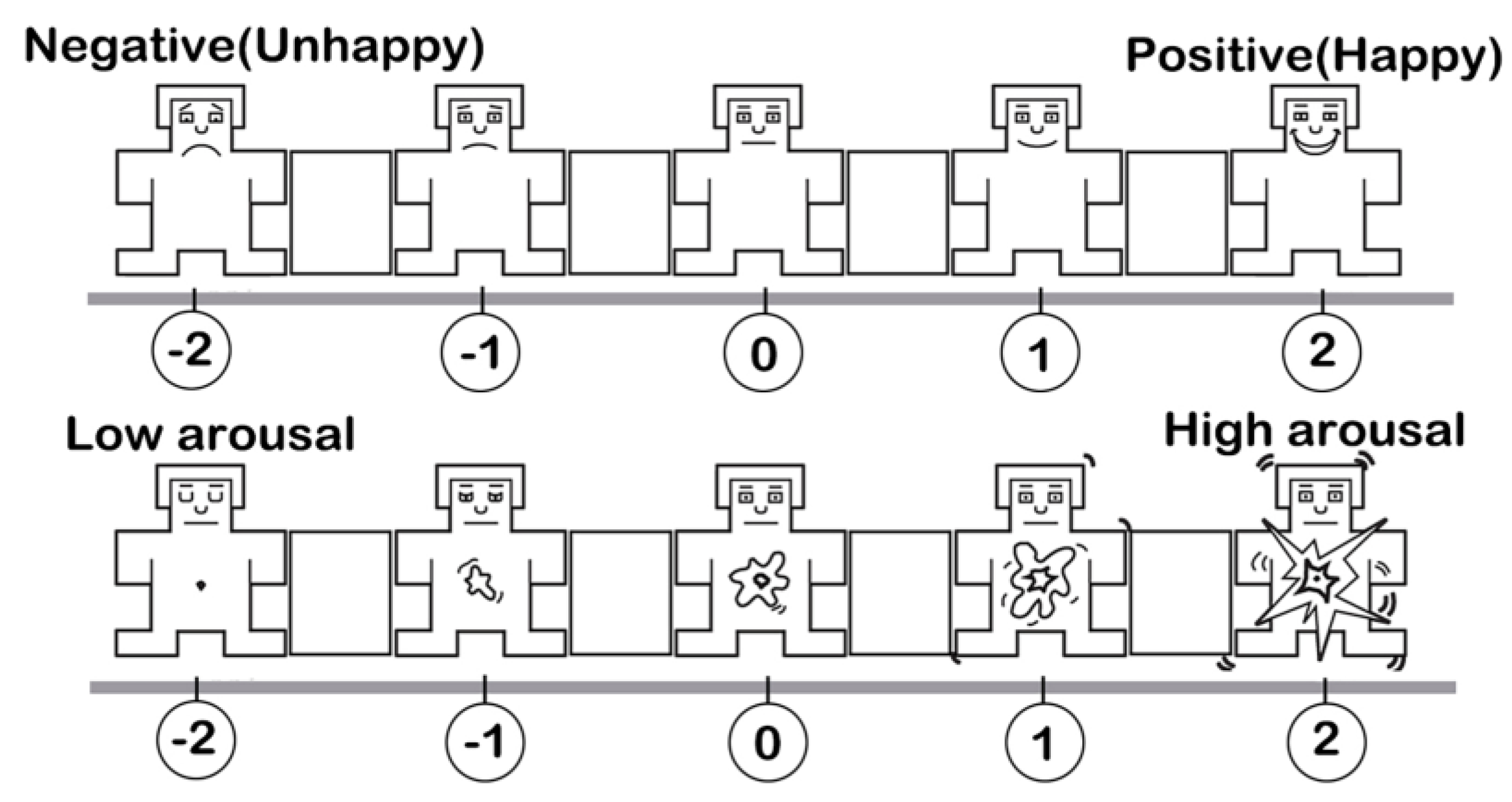

2.3.4. SAM Scale Data Preprocessing

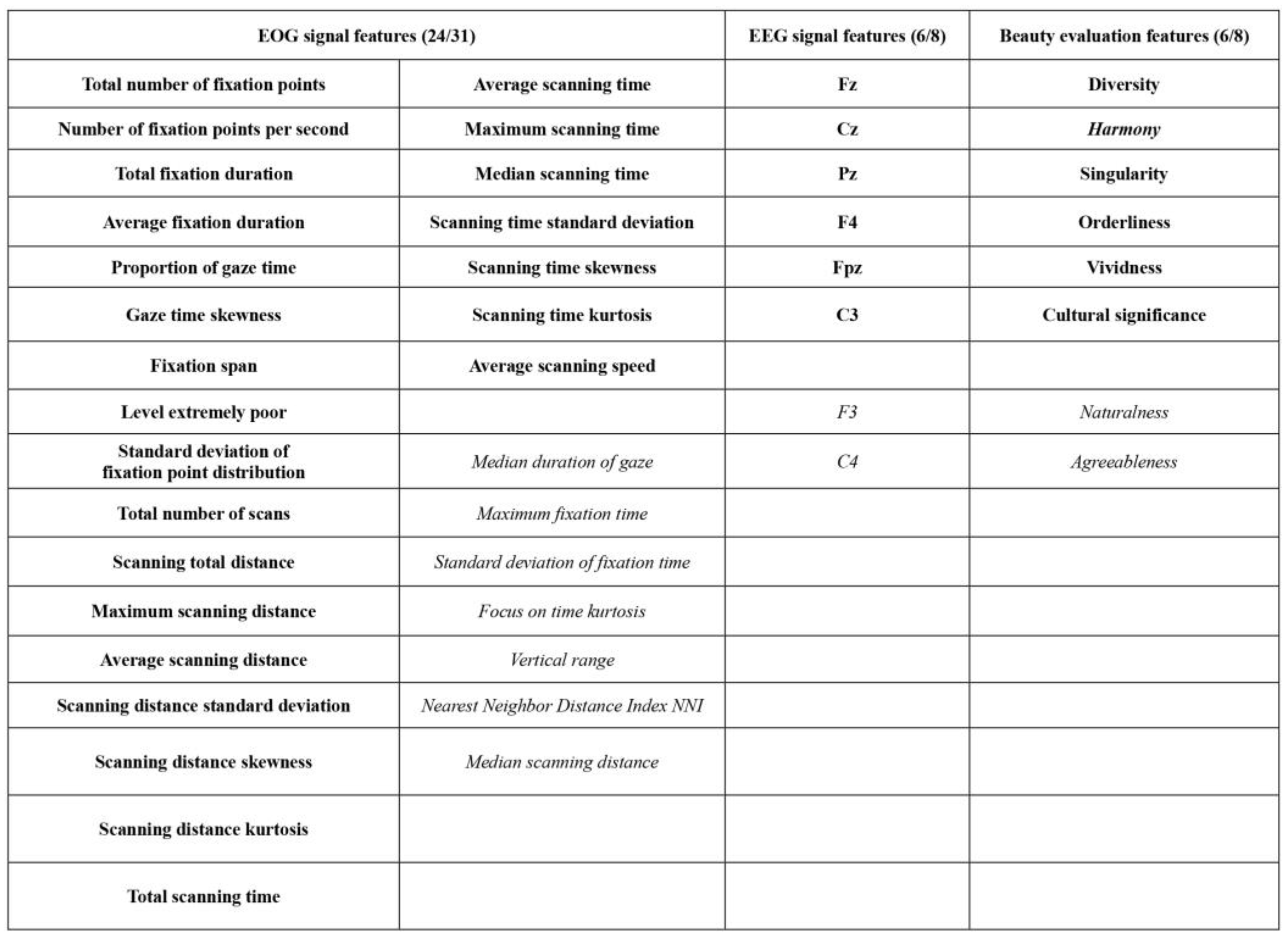

2.3.5. Feature Extraction and Reduction

2.4. Model Construction and Evaluation Methods

2.4.1. Build the Model

2.4.2. Evaluation Methods

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Feature Reduction on the Model

3.2. Model Classification Results and Performance Comparison

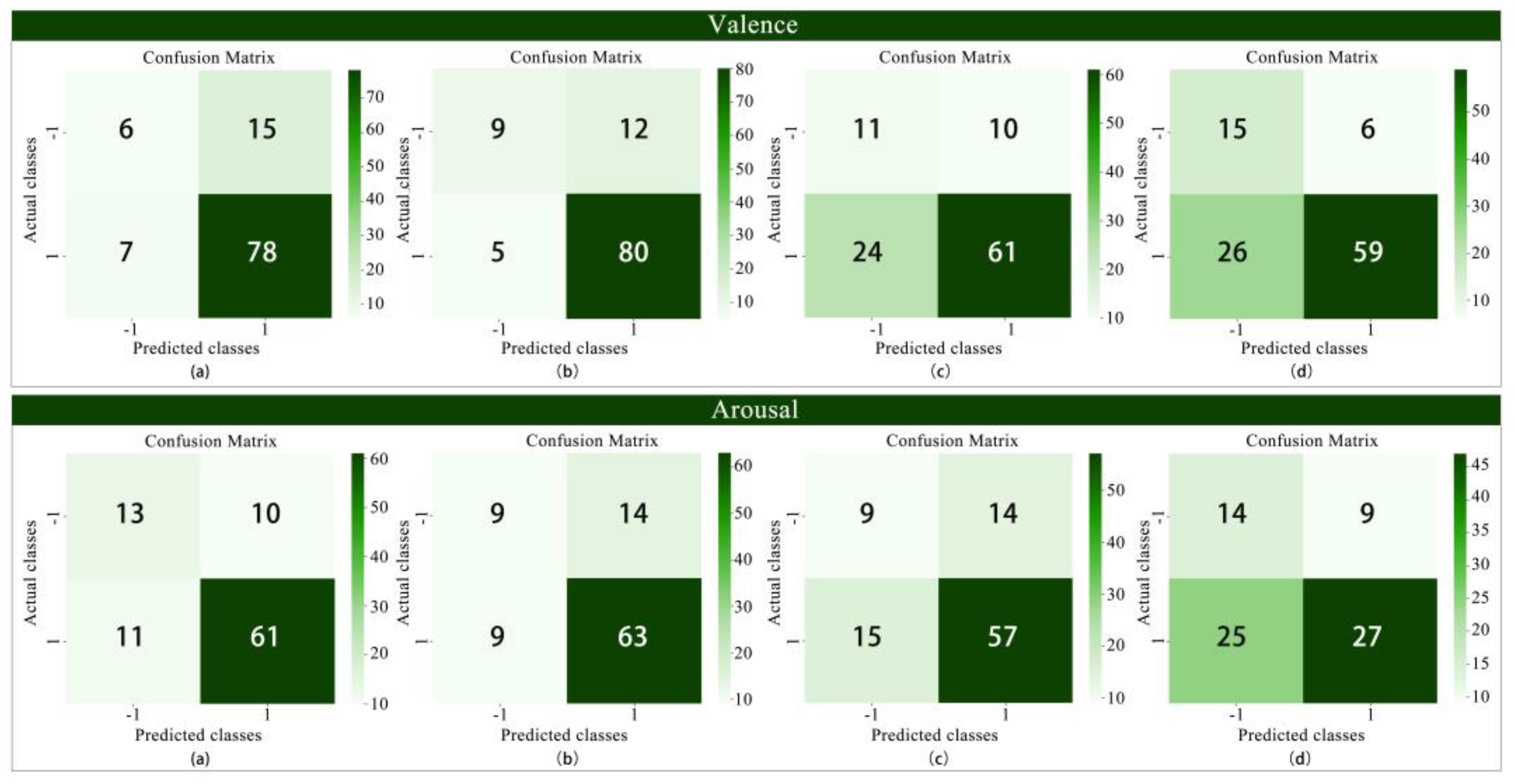

3.2.1. Binary Classification

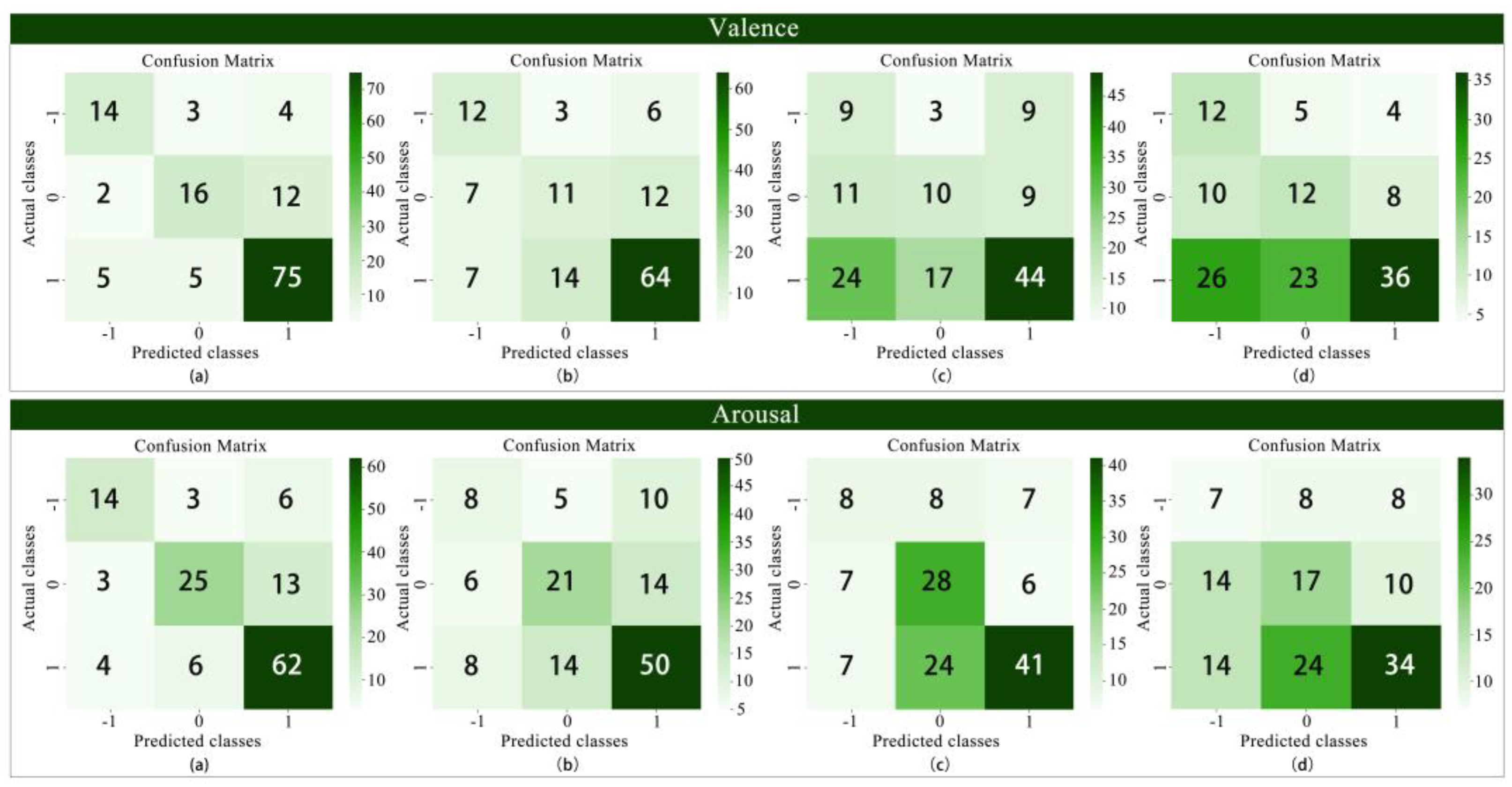

3.2.2. Ternary Classification

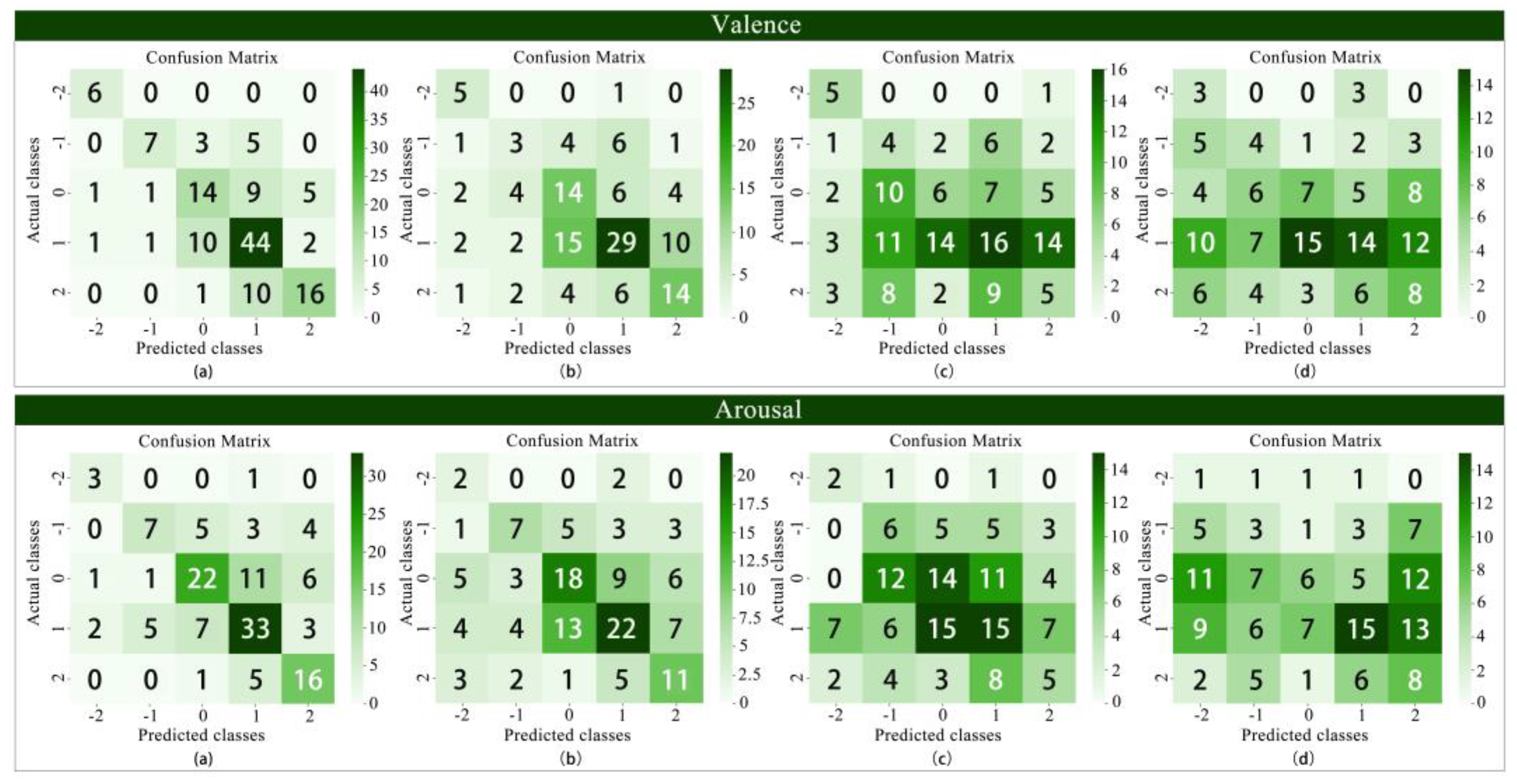

3.2.3. Five-Element Classification

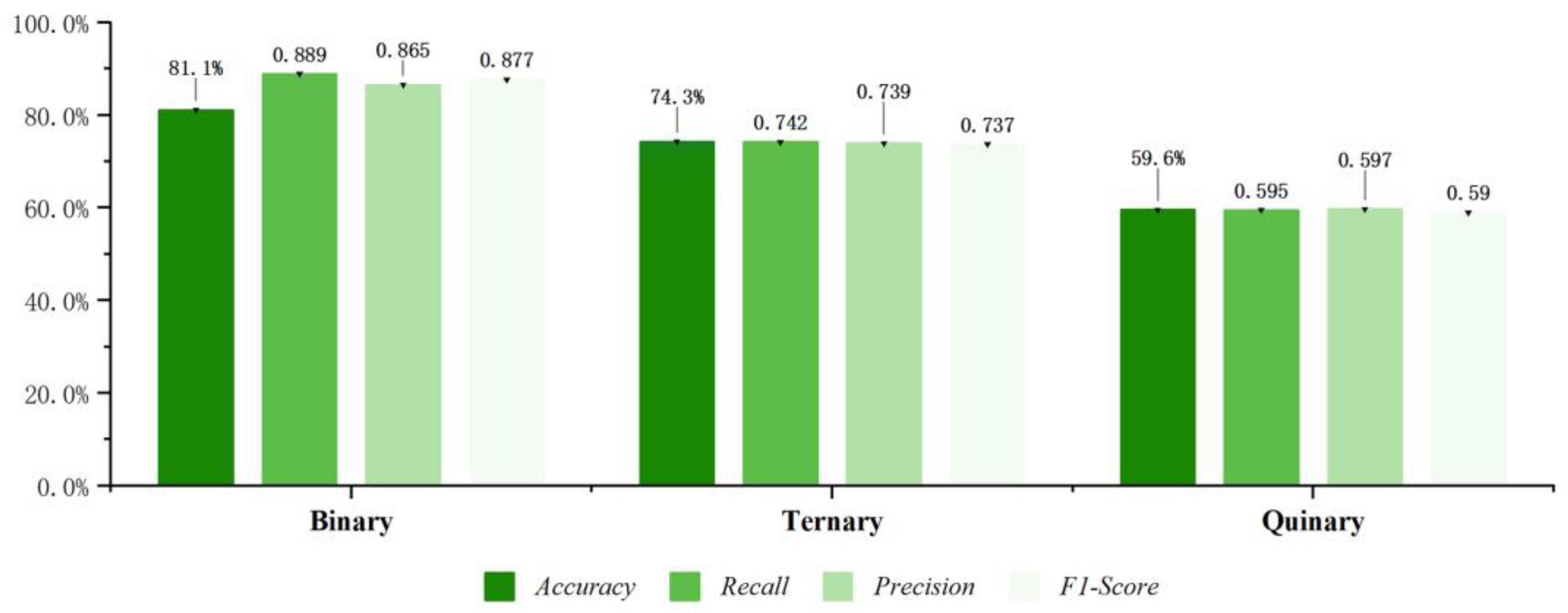

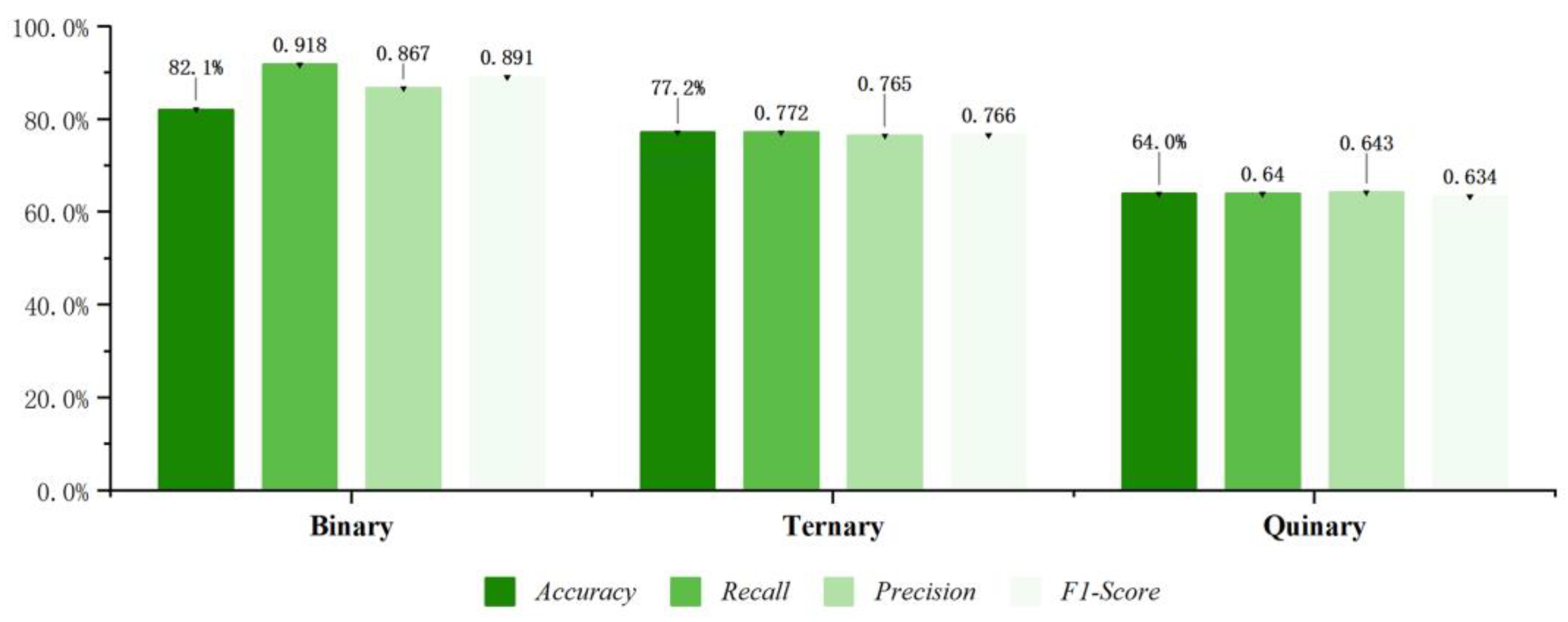

3.2.4. Comparison of Optimal Classification Performance of Models

3.3. Model Usage Process

4. Discussion

4.1. Collaborative Classification of Multimodal and Subjective Data

4.2. Classifier Generalization Verification

4.3. Enrich Sustainable Assessment Methods

4.4. Limitations and Challenges

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EOG | electrooculogram |

| EEG | electroencephalogram |

| SAM | Self-Assessment |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| RF | Random Forest |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| LR-GD | Logistic Regression-Gradient Descent |

References

- Kaplan, A.; Taskin, T.; Onenc, A. Assessing the Visual Quality of Rural and Urban-fringed Landscapes Surrounding Livestock Farms. Biosyst Eng 2006, 95, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zhao, W.; Pereira, P. Ecosystem Restoration along the “Pattern-Process-service-sustainability” Path for Achieving Land Degradation Neutrality. Landscape Urban Plan 2025, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; etc. Assessing, Mapping, and Quantifying Cultural Ecosystem Services at Community Level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33. [CrossRef]

- Sarma, P.; Barma, S. Review on Stimuli Presentation for Affect Analysis Based on EEG. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 51991–52009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, T.; Buot, A.; Grezes, J.; etc. Whose Emotion is It? Perspective Matters to Understand Brain-Body Interactions in Emotions. Neuroimage 2023, 268. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Tao, W.; etc. A Systematic Review on Affective Computing: Emotion Models, Databases, and Recent Advances. Inform Fusion 2022, abs/2203.06935. [CrossRef]

- Benssassi, E.M.; Ye, J. Investigating Multisensory Integration in Emotion Recognition Through Bio-Inspired Computational Models. Ieee T Affect Comput 2021, 14, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Er Ayata; Yaslan, Y.; Kamasak, M.E. Emotion Recognition from Multimodal Physiological Signals for Emotion Aware Healthcare Systems. J Med Biol Eng 2020, 40, 149–157. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, A.; Esposito, A.M.; Vogel, C. Needs and Challenges in Human Computer Interaction for Processing Social Emotional Information. Pattern Recogn Lett 2015, 66, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, N.; Shiv, B.; Bechara, A. The Role of Emotion in Decision Making. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2006, 15, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, R.W.; Vyzas, E.; Healey, J. Toward Machine Emotional Intelligence: Analysis of Affective Physiological State. Ieee T Pattern Anal 2001, 23, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, R.K.; Barry, R. Quick Computation of Spatial Autoregressive Estimators. Geogr Anal 1997, 29, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckenstein, K.S. Defining Affect in Relation to Cognition: A Response to Susan McLeod. The Journal of Advanced Composition 1991, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Noor, N.F.B.M.; Ayub, M.N.B.; etc. Affective Computing in Education: A Systematic Review and Future Research. Comput Educ 2019, 142. [CrossRef]

- Liberati, G.; Veit, R.; Kim, S.; etc. Development of a Binary Fmri-Bci for Alzheimer Patients: A Semantic Conditioning Paradigm Using Affective Unconditioned Stimuli. Ieee T Affect Comput 2013, 1, 838–842. [CrossRef]

- Pei, G.; Li, T. A Literature Review of EEG-Based Affective Computing in Marketing. Front Psychol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, J.A.; Picard, R.W. Detecting Stress During Real-World Driving Tasks Using Physiological Sensors. Ieee T Intell Transp 2005, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazs, J.A.; Velasquez, J.D. Opinion Mining and Information Fusion: A Survey. Inform Fusion 2016, 27, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.M.; Cáceres, M.N. Applying Data Mining for Sentiment Analysis in Music. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing Trends in Cyber-Physical Multi-Agent Systems the Paams Collection - 15Th International Conference, Paams 2017 2017, 198-205. [CrossRef]

- Ducange, P.; Fazzolari, M.; Petrocchi, M.; etc. An Effective Decision Support System for Social Media Listening Based on Cross-Source Sentiment Analysis Models. Eng Appl Artif Intel 2018, 78, 71–85. [CrossRef]

- Maria, E.; Matthias, L.; Sten, H. Emotion Recognition from Physiological Signal Analysis: A Review. Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science 2019, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessous, L.; Castellano, G.; Caridakis, G. Multimodal Emotion Recognition in Speech-Based Interaction Using Facial Expression, Body Gesture and Acoustic Analysis. J Multimodal User in 2009, 3, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Gelbukh, A. Aspect Extraction for Opinion Mining with a Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Knowl-Based Syst 2016, 108, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambria, E.; Das, D.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; etc. Affective Computing and Sentiment Analysis. Socio-Affective Computing. 2017, 5. [CrossRef]

- Cambria, E.; Speer, R.; Havasi, C.; etc. SenticNet: A Publicly Available Semantic Resource for Opinion Mining. Aaai Fall Symposium Commonsense Knowledge 2010.

- Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Bajpai, R.; etc. A Review of Affective Computing: from Unimodal Analysis to Multimodal Fusion. Inform Fusion. 2017, 37. [CrossRef]

- Munezero, M.; Montero, C.S.; Sutinen, E.; etc. Are They Different? Affect, Feeling, Emotion, Sentiment, and Opinion Detection in Text. Ieee T Affect Comput. 2014, 5, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, R.B.; Lee, T.C. II.3. Electrograms (ECG, EEG, EMG, EOG). Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 2010, 152, 90–108.

- Du, G.; Zeng, Y.; Su, K.; etc. A Novel Emotion-Aware Method Based on the Fusion of Textual Description of Speech, Body Movements, and Facial Expressions. Ieee T Instrum Meas 2022, 71, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, X.; Zheng, W.; etc. SEED-VII: A Multimodal Dataset of Six Basic Emotions with Continuous Labels for Emotion Recognition. Ieee T Affect Comput 2024, PP, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Alarcao, S.M.; Fonseca, M.J. Emotions Recognition Using EEG Signals: A Survey. Ieee T Affect Comput 2019, 10, 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lu, B. Investigating Critical Frequency Bands and Channels for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition with Deep Neural Networks. Ieee Transactions On Autonomous Mental Development 2015, 7, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Liu, W.; Lu, Y.; etc. EmotionMeter: A Multimodal Framework for Recognizing Human Emotions. Ieee T Cybernetics 2018, 49, 1110–1122. [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, M.; Lichtenauer, J.; Pun, T.; etc. A Multimodal Database for Affect Recognition and Implicit Tagging. Ieee T Affect Comput 2011, 3, 42–55. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Shoeibi, A.; Khodatars, M.; etc. Emotion Recognition in EEG Signals Using Deep Learning Methods: A Review. Comput Biol Med 2023, 165. [CrossRef]

- Doma, V.; Pirouz, M. A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Methods for Emotion Recognition Using EEG and Peripheral Physiological Signals. J Big Data-Ger 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yuizono, T.; Li, X. Affective Computing of Multi-Type Urban Public Spaces to Analyze Emotional Quality Using Ensemble Learning-Based Classification of Multi-Sensor Data. Plos One 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, G.K.; Tiwary, U.S. Multimodal fusion framework: A multiresolution approach for emotion classification and recognition from physiological signals. Neuroimage 2014, 102, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllopoulos, A.; Schuller, B.W.; Iymen, G.; etc. An Overview of Affective Speech Synthesis and Conversion in the Deep Learning Era. P Ieee 2023, 111. [CrossRef]

- Heredia, B.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Prusa, J.D.; etc. Integrating Multiple Data Sources to Enhance Sentiment Prediction. Ieee Conference Proceedings 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lv, Y.; Zhu, Q.; etc. Research of Food Safety Event Detection Based on Multiple Data Sources. 2015 International Conference On Cloud Computing and Big Data (Ccbd) 2015, 213-216. [CrossRef]

- Mauro, A.; Antonio, S. Agricultural Heritage Systems and Agrobiodiversity. Biodivers Conserv 2022, 31, 2231–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaza, M.; Canas-Ortega, J.F.; Canas-Madueno, J.A.; etc. Assessing the Visual Quality of Rural Landscapes. Landscape Urban Plan 2003, 69, 115–125. [CrossRef]

- Howley, P. Landscape Aesthetics: Assessing the General Publics’ Preferences Towards Rural Landscapes. Ecol Econ 2011, 72, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misthos, L.; Krassanakis, V.; Merlemis, N.; etc. Modeling the Visual Landscape: A Review on Approaches, Methods and Techniques. Sensors-Basel 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Swetnam, R.D.; Harrison-Curran, S.K.; Smith, G.R. Quantifying Visual Landscape Quality in Rural Wales: A GIS-enabled Method for Extensive Monitoring of a Valued Cultural Ecosystem Service. Ecosyst Serv 2016, 26, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, M.; Martinez-Grana, A.; Santos-Frances, F.; etc. Landscape Evaluation As a Complementary Tool in Environmental Assessment. Study Case in Urban Areas: Salamanca (Spain). Sustainability-Basel 2020, 12, 6395. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Sun, Y. Using a Public Preference Questionnaire and Eye Movement Heat Maps to Identify the Visual Quality of Rural Landscapes in Southwestern Guizhou, China. Land-Basel 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiong, X.; Chi, M. Zhang, X.; Xiong, X.; Chi, M.; etc. Research on Visual Quality Assessment and Landscape Elements Influence Mechanism of Rural Greenways. Ecol Indic 2024, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Peng, S. Using Analytic Hierarchy Process to Examine the Success Factors of Autonomous Landscape Development in Rural Communities. Sustainability-Basel 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloquell-Ballester, V.; Torres-Sibille, A.D.C.; Cloquell-Ballester, V.; etc. Human Alteration of the Rural Landscape: Variations in Visual Perception. Environ Impact Asses 2011, 32, 50–60. [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Zhong, Y.; Li, J.; etc. Visual Preference of Plant Features in Different Living Environments Using Eye Tracking and EEG. Plos One 2022, 17, e0279596. [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Yin, M.; Cao, L.; etc. Predicting Emotional Experiences Through Eye-Tracking: A Study of Tourists’ Responses to Traditional Village Landscapes. Sensors-Basel 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, M. Landscape Perception Identification and Classification Based on Electroencephalogram (EEG) Features. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, J.J.; Aspinall, P.A.; Mavros, P.; etc. Engaging the Brain: the Impact of Natural Versus Urban Scenes Using Novel EEG Methods in an Experimental Setting. Environmental Sciences 2013, 1, 93–104. [CrossRef]

- Velarde, M.D.; Fry, G.; Tveit, M. Health Effects of Viewing Landscapes – Landscape Types in Environmental Psychology. Urban for Urban Gree 2007, 6, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.C.; Meitner, M.M. REPRESENTATIONAL VALIDITY OF LANDSCAPE VISUALIZATIONS: THE EFFECTS OF GRAPHICAL REALISM ON PERCEIVED SCENIC BEAUTY OF FOREST VISTAS. J Environ Psychol 2001, 21, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergen, S.D.; Ulbricht, C.A.; Fridley, J.L.; etc. The validity of computer-generated graphic images of forest landscape. J Environ Psychol 1995, 15, 135–146. [CrossRef]

- L. Binyi; W. Yuncai. Theoretical Base and Evaluating Indicator System of Rural Landscape Assessment in China. CHINESE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE. 2002, 18, 76–79. [CrossRef]

- X. Hualin; L. Liming. Research advance and index system of rural landscape evaluation. CHINESE JOURNAL OF ECOLOGY. 2003, 22, 97–101.

- BRADLEY, M.M.; LANG, P.J. Measuring Emotion: the Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. J Behav Ther Exp Psy 1994, 25, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, A.T.; Ng, V.; Tay, L. A Review of Key Likert Scale Development Advances: 1995–2019. Front Psychol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shad, E.H.T.; Molinas, M.; Ytterdal, T. Impedance and Noise of Passive and Active Dry EEG Electrodes: A Review. Ieee Sens J 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Artificial Neural Network-Based Music Therapy for Depression. Comput Intel Neurosc 2022, 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Leung, S. Can Likert Scales Be Treated As Interval Scales?—A Simulation Study. J Soc Serv Res 2017, 43, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S. A Comparison of Psychometric Properties and Normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-Point Likert Scales. J Soc Serv Res 2011, 37, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, I.; Campbell, B.D.; Raikes, A.C.; etc. A Multimodal Exploration of Engineering Students’ Emotions and Electrodermal Activity in Design Activities. J Eng Educ 2018, 107, 414–441. [CrossRef]

- Siirtola, P.; Tamminen, S.; Chandra, G.; etc. Predicting Emotion with Biosignals: A Comparison of Classification and Regression Models for Estimating Valence and Arousal Level Using Wearable Sensors. Sensors-Basel 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Manzanares, M.C.; Perez, I.R.; Rodriguez, A.A.; etc. Analysis of the Learning Process Through Eye Tracking Technology and Feature Selection Techniques. Appl Sci-Basel 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Artoni, F.; Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. Applying Dimension Reduction to EEG Data by Principal Component Analysis Reduces the Quality of Its Subsequent Independent Component Decomposition. Neuroimage 2018, 175, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweke, H.F.; Teh, Y.W.; Mujtaba, G.; etc. Data Fusion and Multiple Classifier Systems for Human Activity Detection and Health Monitoring: Review and Open Research Directions. Inform Fusion 2018, 46, 147–170. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; etc. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique. J Artif Intell Res 2002, 16, 321–357. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; etc. Hyperparameter Optimization for Machine Learning Models Based on Bayesian Optimization. Journal of Electronic Science and Technology 2019, 17. [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bardenet, R.; Bengio, Y.; etc. Algorithms for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. Nips 2011, 2546–2554.

- Santos, M.S.; Soares, J.P.; Abreu, P.H.; etc. Cross-Validation for Imbalanced Datasets: Avoiding Overoptimistic and Overfitting Approaches [research Frontier]. Ieee Comput Intell M 2018, 13, 59–76. [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wen, L.; etc. Speech Emotion Recognition Based on SVM and ANN. International Journal of Machine Learning and Computing 2018, 8, 198–202. [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, W.P.; Novianty, A.; Setianingsih, C. Sentiment Analysis Using Multinomial Logistic Regression. 2017 International Conference On Control, Electronics, Renewable Energy and Communications (Iccrec) 2017. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.F.; Torresen, J. Smartphone Accelerometer Data Used for Detecting Human Emotions. 2016 3Rd International Conference On Systems and Informatics (Icsai) 2016. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K. Remarks on Emotion Recognition from Multi-Modal Bio-Potential Signals. 2004 Ieee International Conference On Industrial Technology, 2004 Ieee Icit ‘04 2004. [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, M.; Lichtenauer, J.; Pun, T.; etc. A Multimodal Database for Affect Recognition and Implicit Tagging. Ieee T Affect Comput 2011, 3, 42–55. [CrossRef]

- Kalimeri, K.; Saitis, C. Exploring Multimodal Biosignal Features for Stress Detection During Indoor Mobility. Proceedings of the 18Th Acm International Conference On Multimodal Interaction 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Morales, J.; Llinares, C.; Guixeres, J.; etc. Emotion Recognition in Immersive Virtual Reality: from Statistics to Affective Computing. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, P.; Tuerlinckx, F.; Russell, J.A.; etc. The Relation Between Valence and Arousal in Subjective Experience. Psychol Bull 2013, 139, 917–940. [CrossRef]

| variable | skewness | kurtosis | minimum value | maximum value | average value | standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naturalness | -0.752 | -0.306 | 1 | 5 | 3.80 | 1.156 |

| Diversity | -0.198 | -0.684 | 1 | 5 | 3.14 | 1.113 |

| Harmony | -0.244 | -0.761 | 1 | 5 | 3.32 | 1.135 |

| Singularity | 0.092 | -0.722 | 1 | 5 | 2.85 | 1.142 |

| Orderliness | -0.201 | -0.752 | 1 | 5 | 3.20 | 1.130 |

| Vividness | -0.202 | -0.487 | 1 | 5 | 3.24 | 1.064 |

| Culture | -0.185 | -0.636 | 1 | 5 | 3.09 | 1.104 |

| Agreeableness | -0.185 | -0.692 | 1 | 5 | 3.32 | 1.170 |

| Class | Classifier | 47 features | 36 features | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-Score | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-Score | |||

| Binary | XGBoost | 79.3% | 0.918 | 0.839 | 0.876 | 82.1% | 0.918 | 0.867 | 0.891 | |

| RF | 79.3% | 0.918 | 0.839 | 0.876 | 84.0% | 0.941 | 0.870 | 0.904 | ||

| Ternary | XGBoost | 65.4% | 0.654 | 0.654 | 0.630 | 77.2% | 0.772 | 0.765 | 0.766 | |

| RF | 62.5% | 0.625 | 0.606 | 0.611 | 64.0% | 0.640 | 0.646 | 0.642 | ||

| Class | Classifier | 47 features | 36 features | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-Score | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-Score | |||

| Binary | XGBoost | 77.9% | 0.847 | 0.859 | 0.853 | 81.1% | 0.889 | 0.865 | 0.877 | |

| RF | 75.8% | 0.875 | 0.818 | 0.846 | 76.8% | 0.875 | 0.829 | 0.851 | ||

| Ternary | XGBoost | 59.6% | 0.596 | 0.591 | 0.582 | 74.3% | 0.743 | 0.740 | 0.738 | |

| RF | 57.4% | 0.574 | 0.556 | 0.558 | 58.1% | 0.581 | 0.578 | 0.579 | ||

| Emotional category | Classifier | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valence | XGBoost | 82.1% | 0.918 | 0.867 | 0.891 |

| RF | 84.0% | 0.941 | 0.870 | 0.904 | |

| DT | 67.9% | 0.718 | 0.859 | 0.782 | |

| LR-GD | 69.8% | 0.694 | 0.908 | 0.787 | |

| Arousal | XGBoost | 81.1% | 0.889 | 0.865 | 0.877 |

| RF | 75.8% | 0.875 | 0.818 | 0.846 | |

| DT | 69.5% | 0.792 | 0.803 | 0.797 | |

| LR-GD | 64.2% | 0.653 | 0.839 | 0.734 |

| Emotional category | Classifier | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valence | XGBoost | 77.2% | 0.772 | 0.765 | 0.766 |

| RF | 64.0% | 0.640 | 0.646 | 0.642 | |

| DT | 46.3% | 0.463 | 0.549 | 0.490 | |

| LR-GD | 44.1% | 0.441 | 0.574 | 0.468 | |

| Arousal | XGBoost | 74.3% | 0.743 | 0.740 | 0.738 |

| RF | 58.1% | 0.581 | 0.578 | 0.579 | |

| DT | 56.6% | 0.566 | 0.604 | 0.572 | |

| LR-GD | 42.7% | 0.427 | 0.485 | 0.445 |

| Emotional category | Classifier | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valence | XGBoost | 64.0% | 0.640 | 0.643 | 0.634 |

| RF | 47.8% | 0.478 | 0.487 | 0.476 | |

| DT | 26.5% | 0.265 | 0.301 | 0.268 | |

| LR-GD | 26.5% | 0.265 | 0.335 | 0.278 | |

| Arousal | XGBoost | 59.6% | 0.596 | 0.598 | 0.590 |

| RF | 44.1% | 0.441 | 0.475 | 0.452 | |

| DT | 30.9% | 0.309 | 0.329 | 0.313 | |

| LR-GD | 24.3% | 0.243 | 0.349 | 0.265 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).