1. Introduction

The application of enzymes in industrial settings, particularly in the textile sector, allows for the development of sustainable processing and methods to enhance the quality of the final product. The use of energy and raw materials, along with heightened awareness of environmental issues associated with the use and disposal of chemicals in landfills, water, or air emissions during chemical processing, are the main reasons for the employment of enzymes in the finishing of textile fabrics, among other applications [

1]. Today, the application of enzymes in industry is mainly limited by cost-effectiveness and therefore, the development of sustainable and affordable methodologies for enzyme production are of the utmost interest.

Enzyme production is currently performed by fermentation mostly in submerged type. Solid-state fermentation (SSF) is an ecofriendly fermentation process since it requires near absence of free water in a solid substrate mixture, containing enough moisture to support microbial life. When performing SSF with filamentous fungi in particular, its hyphae state allows for colonization of the spaces between substrate particles to reach and obtain the available nutrients, as it happens in their natural environment, therefore promoting productivity [

2]. This is especially true for filamentous fungi such as

Aspergillus niger, which naturally secrete a wide range of enzymes as part of their natural metabolism to obtain the nutrients needed from the substrate that supports its growth. Because of this, the cultivation of filamentous fungi has been widely explored and implemented for production of enzymes [

3]. The reduced power consumption and amount of water needed for fermentation, along with the use of agrifood by-products as substrates for microbial growth, makes SSF with filamentous fungi a sustainable method for enzyme production.

The United Nations estimates the global population to grow to 9.3 billion in 2050 [

4], which will, consequently, intensify the demand for food, water and energy. Additionally, the higher need for these resources will intensify environmental pollution and the generation of agro-industrial by-products. These residues are usually disposed of, or, in some cases, used as low-value animal feed, which is the case for brewer’s spent grain (BSG).

BSG represents the most abundant by-product of the beer-brewing process, with an annual production of 8.5 million tons in its dry form [

5]. Due to its low commercial value, the industry and scientific community have been exploring its potential to new applications. Since it largely consists of barley grain husks, its composition contains mainly hemicellulose, cellulose, lignin and protein, making it a great support for microorganism cultivation. Previous studies have shown that SSF with

A. niger CECT 2088 is a suitable biotechnological process to produce lignocellulolytic enzymes, with BSG being the agro-industrial by-product that generated the highest production of lignocellulolytic enzymes, mainly xylanase [

6].

Although BSG is considered a valuable fermentation substrate on its own, the application of pretreatments can further improve the extraction of valuable compounds from BSG. Conventional chemical-based extraction methods are usually implemented to aid in the disruption of cell membranes and contents, improving their bio-accessibility. However, “greener” approaches have recently been explored to reduce the impact on the environment, increase safety, feasibility and cost effectiveness after scale-up [

7]. One of the alternatives to chemical extractions is the application of electric field technologies that can promote rapid heating due to the controllable ohmic heating (OH) effect. OH and autoclaving are two methods that can be implemented as substrate pretreatment to aid in nutrients solubilization before fermentation. OH involves passing an alternate electric current through a semi-conductive matrix generating heat internally, while autoclaving uses high-pressure steam to achieve sterilization. According to Joule's law, the degree of heating is proportional to the matrix's intrinsic electrical resistance. Therefore, this quick transformation of electric energy into thermal energy offers a benefit that could hasten membrane disruption and solute solubilization from cell membranes, as well as promote fast and uniform volumetric heating [

8]. Electric field technologies and the consequent application of OH have previously been highlighted as valuable tools for extraction due to their ability to induce electro-permeabilization of the cell membrane by altering transmembrane potential. This may result in electro permeabilization or other kinds of permeabilization effects and release of intracellular compounds [

9,

10], thus affecting microbial metabolism and fermentation outcomes [

11]. Although autoclaving remains the most common pretreatment method used in fermentation processes to enhance the breakdown of biomass and induce sterilization, it is here postulated that OH could serve as an alternative to autoclaving due to its ability to reach and maintain high temperatures throughout the substrate and consequently deconstruct the substrate structures.

In the present study, Aspergillus niger was grown in solid-state BSG to assess the production of industrially valuable enzymes, namely endo-1,4-β-glucanase, amylase, β-glucosidase, xylanase, pectinase and protease. Additionally, the impact of substrate pretreatment by OH and autoclaving were compared. The crude extract obtained from the SSFs was used to obtain a highly active, concentrated enzymatic cocktail.

Therefore, the production of industrially important enzymes from filamentous fungus Aspergillus niger utilizing pretreated BSG as a substrate allows for a low-cost, eco-friendly solution for textile processing, among other applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism

Aspergillus niger CECT 2088 was obtained from the Coleción Española de Cultivos Tipo (CECT Valencia, Spain) and stored at −80 °C in an aqueous solution of 1% (w/v) peptone and 30 % (v/v) glycerol. The fungal strain was revived in potato dextrose agar medium (potato extract 4 g/L, dextrose 20 g/L, agar 15 g/L) for 7 days at 25 °C.

2.2. Raw Materials

Brewer’s spent grain (BSG) was supplied by LETRA craft brewery (Vila Verde, Portugal). The material was dried (< 10 % moisture) and ground to 10 mm particle size [

6] using a Retsch SM 300 cutting mill (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany). Dried BSG was stored in hermetic bags at room temperature.

2.3. Substrate Pretreatment and Inoculation

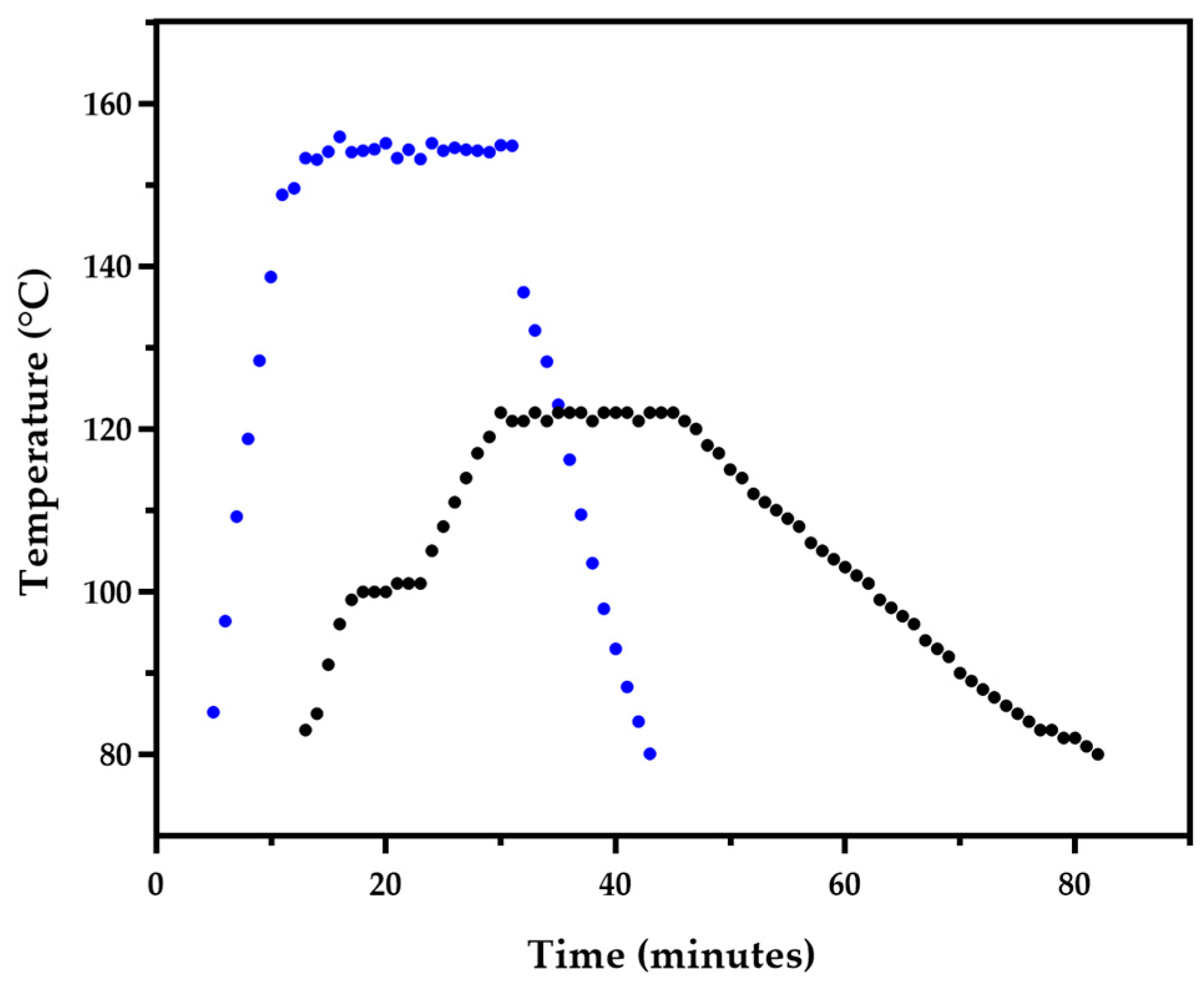

Brewer’s spent grain (BSG) was pretreated by autoclaving or OH after adjusting the initial moisture to 75 % (w/w) with a solution of 0.03 % w/w sodium chloride in distilled water. The salt was added to increase water electrical conductivity to a value of 1 mS/cm. For these experiments, approximately 10 g (dry weight) of substrate were used. The pretreatment performed by autoclaving (Panasonic labo autoclave MLS-3020U-PE) was carried out at 121 °C for 15 minutes inside 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. OH was performed in a cylindrical polytetrafluoroethylene reactor with two stainless steel electrodes defining a total volume of 45 mL. Treatment conditions were set to a frequency of 20 kHz under a constant electric field of 11 V/cm which allowed to conduct thermal treatments at 145 °C for 20 minutes (

Figure 1). These conditions guaranteed the necessary sterilization conditions but also allowed for the study of the advantage of using ultra-high temperature (> 140 °C) to promote electro and thermal disruption of the material to enhance its functionalization for further steps. BSG subjected to OH was transferred to a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask in sterile conditions and followed inoculation. The temperature was monitored for both pretreatments. The treated substrates were inoculated with 5 evenly distributed mycelium agar disks (1 cm diameter) of

Aspergillus niger CECT 2088, previously grown in potato dextrose agar plates.

All SSFs were incubated at 27 °C for 7 days in the dark.

2.4. Extraction

For soluble compound monitoring, an extraction was performed by adding water to the fermented substrate at the previously optimized proportion of 1 g dry solid to 10 ml water, followed by agitation (150 rpm) and centrifugation (822 g) at 4 °C. The supernatant was filtered by vacuum with a 2.5 μm pore size filter. All the extracted samples were kept frozen at -20 °C and thawed at the time of use.

2.5. Enzymatic Assays

The activity of endo-1,4-

β-glucanase was measured using carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) as substrate as follows: 250 μL of 2 % (w/v) carboxymethylcellulose in citrate buffer 0.05 M, pH 5, was incubated with the same volume of the extracted sample at 50 °C for 30 minutes. Released glucose, the only reducing sugar liberated from the CMC hydrolysis, was quantified by the dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method [

12]. After the addition of 500 μL of DNS reagent, the mixture was placed in a water bath at 100 °C for 5 minutes, followed by the addition of 1 mL of distilled water before reading the absorbance at 540 nm. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme needed to release 1 μmol/min of glucose under the conditions of the assay.

The procedure to determine xylanase activity was similar to the one described for endo-1,4-β-glucanase activity but using xylan 1 % (w/v) as a substrate. Released xylose, the only reducing sugar released from xylan hydrolysis, was also quantified by the DNS method (as described for endo-1,4-β-glucanase activity). One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol/min of xylose under the assay conditions.

Amylase activity was quantified using starch as a substrate. Briefly, 250 μL of 2 % (w/v) starch substrate in sodium acetate buffer 0.05 M, pH 4.8, was incubated with 250 μL of the extracted sample at 40 °C for 30 minutes. The DNS method was used to quantify the released maltose (as described for endo-1,4-β-glucanase activity). One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol/min of maltose under the assay conditions.

Pectinase activity was quantified using 1 % (w/v) pectin as a substrate, applying the same protocol as the one described for amylase. The DNS method was used to quantify the released D-galacturonic acid (as described for endo-1,4-β-glucanase activity). One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol/min of maltose under the assay conditions.

The activity of β-glucosidase was determined by incubating 100 μL of the substrate, 4 mM 4-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside, in 0.05 M citrate buffer, pH 5, with 100 μL of the extracted sample at 50 °C for 15 minutes. To stop the reaction, 0.6 mL of sodium carbonate 1 M was added, following the addition of 1.7 mL distilled water. The mixture’s absorbance was then at 400 nm. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme needed to release 1 μmol/min of p-nitrophenol under the assay conditions.

Protease activity was determined by using azocasein as a substrate. 500 μL of 0.5 % (w/W) azocasein in sodium acetate buffer 0.05 M, pH 4.8, was incubated with 500 μL of the extracted sample at 37 °C for 40 minutes in the dark. The reaction was then stopped by adding 1 mL of 10 % trichloroacetic acid and centrifuged 0.6

g for 15 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to glass tubes and 1 mL 5 M potassium hydroxide and 1 mL water were added. The mixture’s absorbance was then at 428 nm. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that causes an increase of 0.01 absorbance comparatively to the blank (supernatant was replaced by sodium acetate buffer 0.05 M) per minute under assay conditions [

13].

All absorbance readings were performed on a 96-well plate using the ThermoScientific MultiSkan Sky plate reader. Each enzymatic activity was expressed in units per gram of dry by-product (U/g).

2.6. Analytical Methods

Reducing sugars in the extracts were quantified by the DNS method mixing 100 μL of extract with 100 μL of DNS and placing the mixture in a water bath at 100 °C for 5 minutes, followed by the addition of 1 mL of ultra-pure water before reading the absorbance at 540 nm.

Soluble protein quantification was performed using the Bradford method [

14]. Briefly, 5 μL of sample were mixed with 200 μL of Coomassie Blue reagent, mixed thoroughly and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. For less protein-rich samples, 150 μL of sample were mixed with 150 μL of Coomassie Blue reagent instead. The final solutions were shaken for 30 seconds, the absorbance read at 595 nm and converted to concentration using Bovine Serum Albumin as standard.

Total phenolic concentration was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method (Commission Regulation (EEC) No. 2676/90). For this, 10 μL of sample were mixed with 200 μL of sodium carbonate 15 % (w/v) solution, 50 μL of Folin reagent and 740 μL of ultra-pure water and incubated at 50 °C for 10 minutes. Absorbance of the final incubated mixture was performed at 700 nm and converted to concentration of caffeic acid.

Antioxidant activity was quantified by a 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay as described by Dulf [

15] and adapted by Estevão-Rodrigues et al. [

16], and expressed in mg of Trolox equivalents per gram of dry substrate by absorbance reading at 517 nm.

All absorbance readings were performed on a 96-well plate using the ThermoScientific MultiSkan Sky plate reader.

The substrate used in this study has been previously characterized regarding its ashes, protein, total lipids, Klason lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose by Guimarães et al. (

Table 1) [

6].

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Substrates were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) before and after pretreatment using the Hitachi FlexSEM1000. Additional details regarding image capture are described in the respective figures. No coating was applied in any of the observed samples.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Three replicates were performed for analyses before fermentation and two replicates for enzyme activity assessments after fermentation. Results were analyzed by t-test (two-sample assuming unequal variance) or by one-way ANOVA, applying the Tukey multiple-comparisons test (p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. BSG Pretretatment

BSG was pretreated by OH or autoclaving according with conditions that led to different temperature profiles exposure (

Figure 1). OH conditions allow for not only the necessary sterilization conditions but also for the use of ultra-high temperature (> 140 °C) to promote electro and thermal disruption of BSG.

Moreover, OH allowed to reach a stable ultra-high temperature very fast reaching 120 °C after 8 minutes, from ambient temperature, and 140 °C after 10 minutes, while autoclaving took 29 min to attain 121 °C. Also, the rate of cooling down of OH is higher than the autoclave. Thus, OH represents an overall faster method for substrate pretreatment than the standard autoclaving, therefore, using OH as pretreatment at industrial settings may represent significant productivity improvement and power consumption savings.

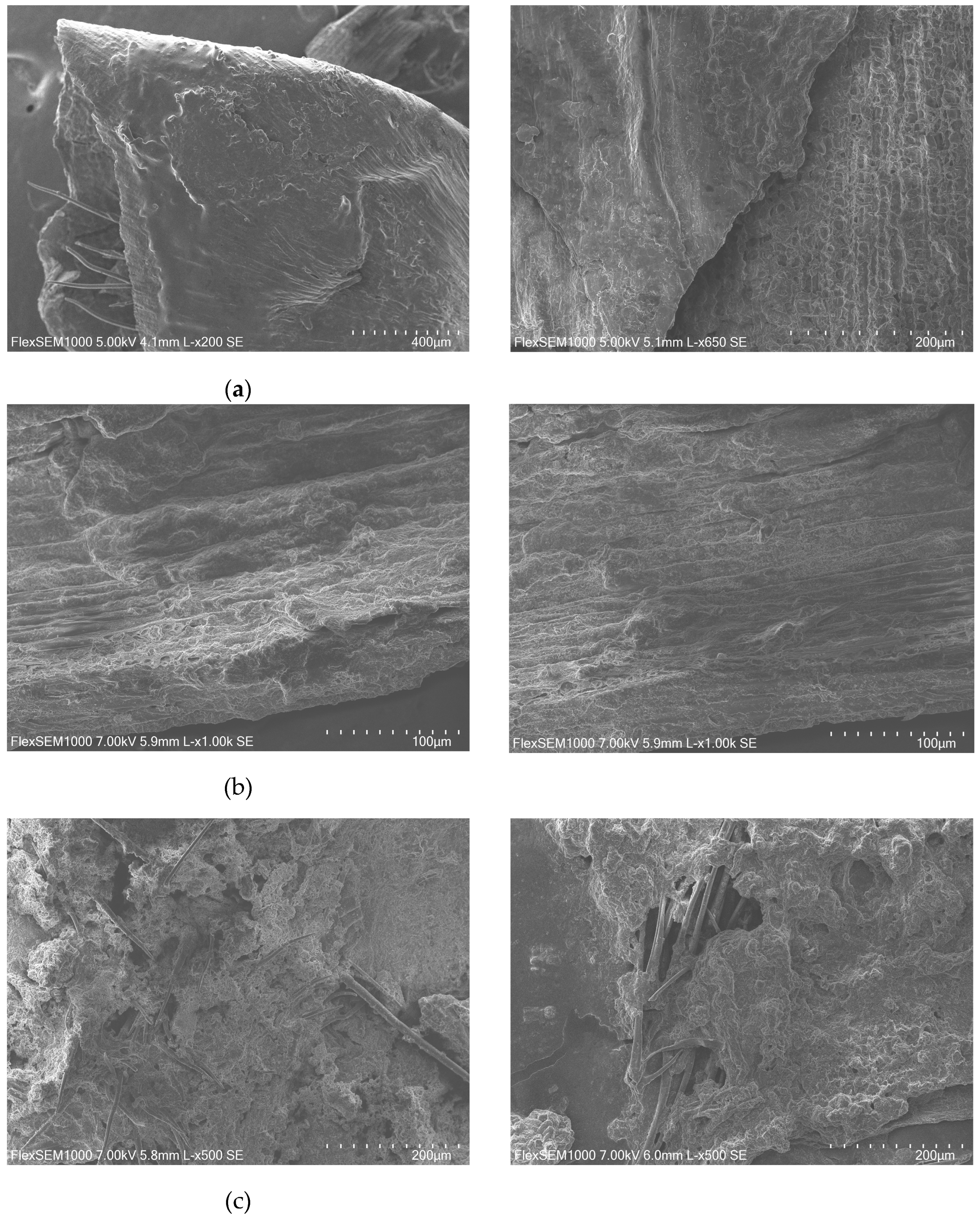

The substrate was observed with SEM in its three different states: original (no treatment) (

Figure 2a), after autoclaving (

Figure 2b), and after the application of OH (

Figure 2c). In its original form, the vegetal tissues that constitute BSG form very organized, stable structures. After autoclaving, these structures seem to keep their integrity, showing visibly uniform texture. However, after the application of electric current in the previously mentioned conditions, the vegetal structures appear more disintegrated and show more exposed fibers.

These observations go accordingly to the previously mentioned studies that conclude that the application of electric fields can cause disruption of the cells that form the matrix or tissue. This disintegration of cellular structure, along with the heat generated internally, causes visible changes in the overall structure of BSG. Therefore, this sustains the hypothesis that OH could lead to a more effective release of valuable-added compounds present in BSG that could consequently improve growth and metabolism of Aspergillus niger.

3.2. Substrate Characterization Before and After Fermentation

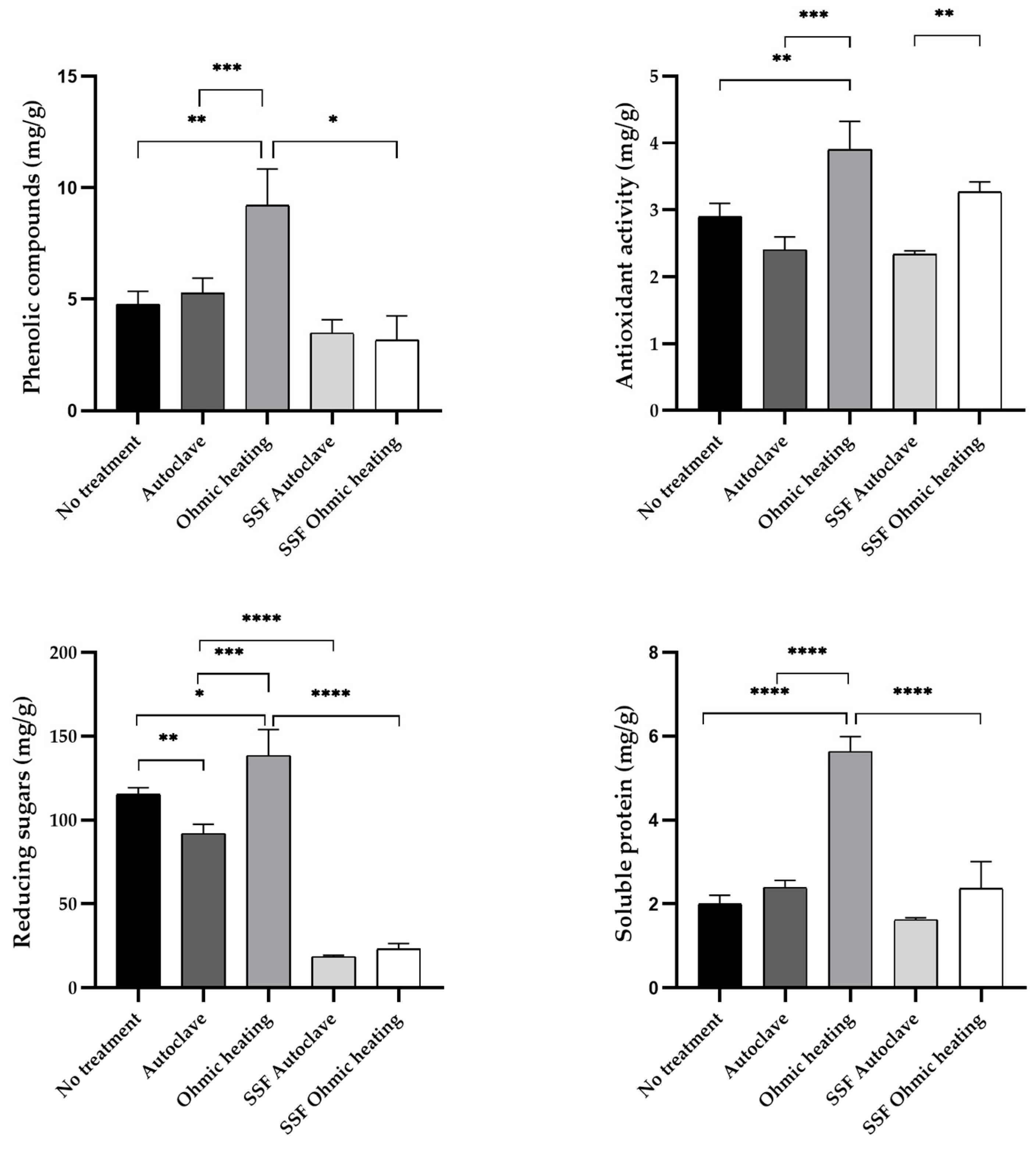

Phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, reducing sugars and soluble protein were quantified before and after pretreatment. Additionally, the same analyses were conducted after SSF with both pretreatments (

Figure 3). SSF efficiency can be affected by the chemical composition of solid substrates which can influence microbial growth and enzyme activity. For instance, high cellulose and hemicellulose concentrations may induce the production of lignocellulolytic enzymes, while the protein content can promote the synthesis of proteolytic enzymes [

17].

Before fermentation, pretreatment of BSG by OH significantly increased phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, reducing sugars and soluble protein concentration in the aqueous extracts, compared to the extracts obtained in BSG without any treatment (

Figure 3). In contrast, autoclaving the substrate did not cause a significant increase in any of the monitored parameters. OH increased the concentration of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity by 42.7 % and 38.5 % respectively, compared to autoclaving. Regarding the liberation of reducing sugars, there is a slight decrease in autoclaved substrates, while OH increased their concentration, resulting in a difference of 33.6 % between the two pretreatments. The increase in soluble protein content by OH is the most accentuated, resulting in more than double the concentration in the OH treated BSG compared to the untreated substrate.

Overall, by comparing OH and autoclaving pretreatments, OH increased the release of soluble compounds in all cases, with significant differences to autoclaving for all analyses. Thus, the application of electric current and consequent induction of OH significantly improves the release of phenolic compounds, reducing sugars and soluble protein and seems to be a better alternative to autoclaving for the release of these molecules.

After fermentation, for autoclaved substrates, there are no significant differences in either phenolic compound concentration, antioxidant activity or soluble protein concentration (

Figure 3). However, contrary to autoclaving, pretreating the substrate by OH leads to significant decrease of soluble proteins and phenolic compounds, suggesting that the increased release of proteins and phenolics from BGS increased their bioavailability and could therefore benefit the growth of the fungus. In these conditions, these compounds could be taken up and metabolized by

A. niger overtime or even liberated from the solid by the action of the enzymes secreted of

A. niger [

16,

17,

18]. For both pretreatments, a significant decrease in reducing sugar concentration is observed after fermentation, indicating that the fungus could use the sugars solubilized by both pretreatment methods.

Additionally, it seems that OH has improved the consumption of soluble proteins and phenolic compounds during fermentation. These results go accordingly with the previous observations by SEM (

Figure 2), where the application of OH caused visible changes and apparent modification of the structure of BSG, contrarily to autoclaving. This modification supports the hypothesis that OH causes the deconstruction of the matrix, inducing the solubilization of intracellular compounds. These aspects are especially relevant since differences in solubilization, and increased bioavailability of these molecules could interfere with microbial growth and consequent enzymatic production from

A. niger.

Crude extracts rich in phenolics have a wide range of industrial applications such as in cosmetics, health [

18] and, particularly, in the food industry, since they improve the quality and nutritional value of food [

19]. In plant tissues such as BSG, phenolic compounds occur in free, esterified and insoluble-bounded forms [

20], which have low bioavailability. Therefore, there is a need to select suitable processes to increase the bioavailability of phenolics by facilitating their release [

21]. As previously mentioned, pretreatment of the substrate by OH led to an increase in the release of these compounds, compared to the standard autoclaving (

Figure 3). This reflects the potential application of OH not only for enhanced enzymatic production through SSF, but also as a tool for obtaining phenolic rich extracts for other industrial applications.

It is currently unclear how phenolic compounds affect growth and metabolism of microorganisms, and, in return, how different microorganisms affect total phenolic concentration during fermentation. In a study conducted by Ma et al. [

22] in fermentation of tea leaves by

A. niger, it was hypothesized that

Aspergillus plays an important role in the production of enzymes which catalyze hydrolysis, oxidization, conversion, and biodegradation of phenolic compounds, causing variations in phenolic compounds present in the substrate. Additionally, the total phenolic concentration seems to increase or decrease depending on the microorganism strains [

23]. In contrast to our results, Dulf et al. demonstrated that the total phenolic concentration increased by > 21 % for SSF with

A. niger ATCC-6275 [

24]. This further supports the hypothesis that different strains of

A. niger could vary the outcome of phenolic compound degradation. Additional studies need to be conducted to infer on the impact of different strains and substrate profiles in phenolic degradation and fermentation outcomes.

Regarding protein concentration, although complex nitrogen sources are usually used for enzymatic production, the requirement for a specific nitrogen supplement differs from organism to organism. Generally, fungi produce more proteolytic enzymes on more complex proteinaceous nitrogen sources than on low molecular weight or inorganic nitrogen sources [

25]. Thus, the implementation of substrate pretreatment by OH could further enhance protein bioavailability in agricultural by-products, making them more suitable in industrial settings such as in enzyme production without need for further supplementation.

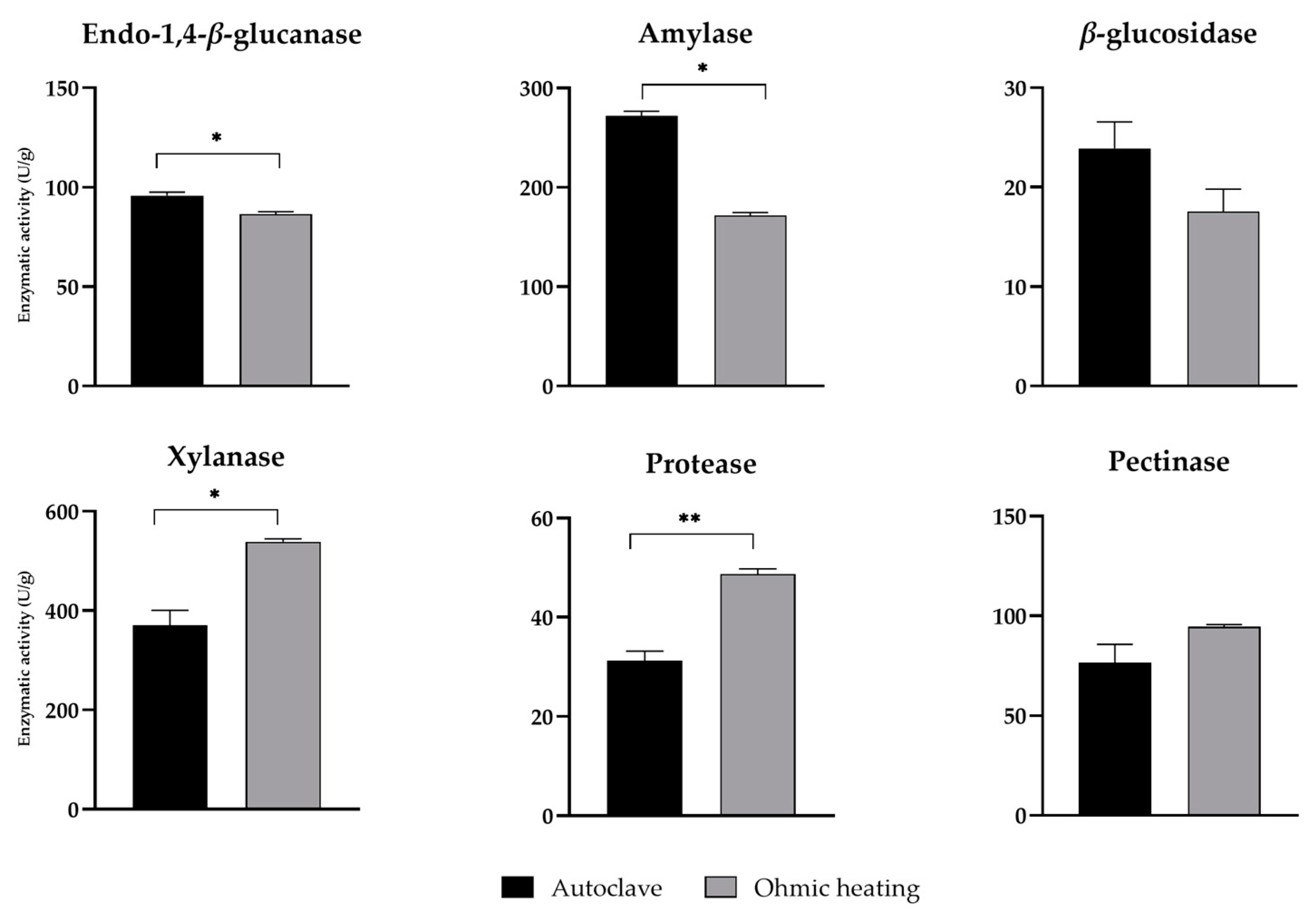

3.3. Enzymatic Activity After Fermentation

After SSF with pretreated BSG, the enzymatic activity of different types of lignocellulolytic enzymes (namely endo-1,4-

β-glucanase,

β-glucosidase and xylanase), amylase, protease and pectinase present in the aqueous extracts have been quantified (

Figure 4). Although the results show a slight but significant decrease in endo-1,4-

β-glucanase and amylase activity, no significant differences were found in

β-glucosidase and pectinase activities. Otherwise, a significant increase of 31 % and 37 % in xylanase and protease activities, respectively, was obtained in extracts of BSG treated by OH compared to autoclaved and fermented BSG. Xylanase was the enzyme with the highest values of activity, reaching around 540 U/g in SSF of OH treated BSG. This increase in xylanase production may be related to the increase in hemicellulose exposure to the fungus in BSG treated by OH as shown by the structural changes of the solid matrix (

Figure 2). The application of OH also enhanced protease activity, resulting in the highest value of 49 U/g. Additionally, increased bioavailability of proteins, phenolic compounds and reducing sugars induced by OH (

Figure 3), contributed to fungal growth and metabolism and consequent to enzyme secretion.

Proteases are one of the largest groups of industrial enzymes, accounting for 60 % of total global enzyme sales [

26,

27]. This group of enzymes have been applied in several industries, from detergents to leather processing, pharmacology, among others [

28]. Alongside proteases, xylanases have great potential for industrial applications, such as in textile, pulp and paper industry, food processing and lignocellulosic biomass saccharification, among others [

28].

Previous studies using BSG as substrate for the growth of

A. niger [

6] concluded that a peak in xylanase activity was found after 7 days of SSF, followed by a significantly decrease between the 10 and 14 days of fermentation. Contrarily, endo-1,4-

β-glucanase,

β-glucosidase, and amylase activities increased over time, indicating that time is an important factor for selection of enzyme production. Leite et al. used olive pomace as substrate [

29] and observed that the maximal endo-1,4-

β-glucanase activity (35 U/g) was obtained after 11 days of SSF. Similarly, and Liguori et al. [

30] verified that cellulases production by

A. niger LPB-334 from BSG reached its peak at 10 days. Therefore, regarding the herein results, it is possible that endo-1,4-

β-glucanase,

β-glucosidase, and amylase activities could be enhanced further by increasing fermentation time.

Due to the wide range of sectors in which enzymes are used, the market for these enzymes has grown significantly in recent years. With lignocellulolytic enzymes contributing to more than 20 % of total revenue, the industrial enzyme market is projected to reach US

$ 8.7 billion in 2026 [

31]. The market for enzymes is anticipated to rise further due to rising demand from sectors like paper, leather, textiles, and biodiesel [

32]. Given the rising market projections and demand, and the need to employ more sustainable approaches to enzyme production, the use of inexpensive substrates and minimization of water and energy consumption while simultaneously achieving high yields is imperative.

Therefore, the use of BSG is a sustainable and economic substrate for production of enzymes. For the case of xylanase and protease activity, this is further improved by the application of electrical fields as pretreatment. The ability to produce enzymes of high commercial interest such as xylanases and proteases using low-cost, eco-friendly substrates (such as BSG) and methods (SSF, for instance) is extremely important to meet the societal demands in an environmentally endangered planet. Further enhancing this enzymatic production with “greener” alternatives to the commonly used chemical approaches such as OH becomes a viable strategy for working around emerging issues.

4. Conclusions

While previous studies have already highlighted the potential of BSG for lignocellulosic enzyme production through SSF, this study demonstrated the potential of using OH as a tool for further improving substrate composition and consequently, enzymatic production. In contrast to conventional autoclaving, OH increased the deconstruction of the matrix’s structures, enhanced release and microbial up-take of substrate components. This is further reflected in enzymes production, where xylanase and protease were the most improved by OH pretreatment.

Our findings suggest that OH is an energy efficient and environmentally friendly strategy to enhance the production of enzymes of significant industrial interest, as it can reduce water consumption. Additionally, this method allows for potential valorization of agro-industrial by-products and thus leads to the reduction of their environmental impacts, contributing to a circular economy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B. and R.P.; formal analysis, B.F.S., L.M., R.P., I.B.; investigation, B.F.S., L.M., R.P., L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.F.S.; writing—review and editing, B.F.S., L.M., I.B., R.P.; funding acquisition, A.M.F., R.P., I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the integrated project be@t – Textile Bioeconomy (TC-C12-i01, Sustainable Bioeconomy No. 02/C12- i01.01/2022), promoted by the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), Next Generation EU, for the period 2021 – 2026.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from integrated project be@t – Textile Bioeconomy (TC-C12-i01, Sustainable Bioeconomy No. 02/C12- i01.01/2022), promoted by the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), Next Generation EU, for the period 2021 – 2026.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SSF |

Solid-state fermentation |

| BSG |

Brewer’s spent grain |

| OH |

Ohmic heating |

| CECT |

Coleción Española de Cultivos Tipo |

| CMC |

Carboxymethylcellulose |

| HPLC |

High-performance liquid chromatography |

| DNS |

Dinitrosalicylic acid |

| DPPH |

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Abd El Aty, A.A.; Saleh, S.A.; Eid, B.M.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Mostafa, F.A. Thermodynamics characterization and potential textile applications of Trichoderma longibrachiatum KT693225 xylanase. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 129–137. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, C. Solid-State Fermentation Systems—An Overview. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2005, 25, 1–30.

- Intasit, R.; Cheirsilp, B.; Suyotha, W.; Boonsawang, P. Synergistic production of highly active enzymatic cocktails from lignocellulosic palm wastes by sequential solid state-submerged fermentation and co-cultivation of different filamentous fungi. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 173. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. The Outlook for Population Growth. Science (1979) 2011, 333, 569–573.

- Mussatto, S.I.; Dragone, G.; Roberto, I.C. Brewers’ Spent Grain: Generation, Characteristics and Potential Applications. J Cereal Sci 2006, 43, 1–14.

- Guimarães, A.; Mota, A.C.; Pereira, A.S.; Fernandes, A.M.; Lopes, M.; Belo, I. Rice Husk, Brewer’s Spent Grain, and Vine Shoot Trimmings as Raw Materials for Sustainable Enzyme Production. Materials 2024, 17, 935. [CrossRef]

- Picot-Allain, C.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Ak, G.; Zengin, G. Conventional versus green extraction techniques — a comparative perspective. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 40, 144–156. [CrossRef]

- Gavahian, M.; Sastry, S.; Farhoosh, R.; Farahnaky, A. Chapter Six - Ohmic Heating as a Promising Technique for Extraction of Herbal Essential Oils: Understanding Mechanisms, Recent Findings, and Associated Challenges. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Toldrá, F.; Academic Press, 2020; Volume 91, pp. 227–273.

- Maciel, F.; Machado, L.; Silva, J.; Pereira, R.N.; Vicente, A. Effect of ohmic heating on the extraction of biocompounds from aqueous and ethanolic suspensions of Pavlova gyrans. Food Bioprod. Process. 2024, 148, 43–51. [CrossRef]

- Marques, F.; Pereira, F.; Machado, L.; Martins, J.T.; Pereira, R.N.; Costa, M.M.; Genisheva, Z.; Pereira, H.; Vicente, A.A.; Teixeira, J.A.; et al. Comparison of Different Pretreatment Processes Envisaging the Potential Use of Food Waste as Microalgae Substrate. Foods 2024, 13, 1018. [CrossRef]

- Machado, L.; Geada, P.; Teixeira, J.A.; Pereira, R.N. Improving the accessibility of phytonutrients in Chlorella vulgaris through ohmic heating. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 97. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, S.M.; Lopes, M.; Belo, I. Exploring the use of hexadecane by Yarrowia lipolytica: Effect of dissolved oxygen and medium supplementation. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 380, 29–37. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72, 248–254.

- Dulf, F.V.; Vodnar, D.C.; Dulf, E.-H.; Toşa, M.I. Total Phenolic Contents, Antioxidant Activities, and Lipid Fractions from Berry Pomaces Obtained by Solid-State Fermentation of Two Sambucus Species with Aspergillus Niger. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 3489–3500.

- Estevão-Rodrigues, T.; Fernandes, H.; Moutinho, S.; Filipe, D.; Fontinha, F.; Magalhães, R.; Couto, A.; Ferreira, M.; Gamboa, M.; Castro, C.; et al. Effect of solid-state fermentation of Brewer's spent grain on digestibility and digestive function of european seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) juveniles. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2024, 315. [CrossRef]

- Leite, P.; Sousa, D.; Fernandes, H.; Ferreira, M.; Costa, A.R.; Filipe, D.; Gonçalves, M.; Peres, H.; Belo, I.; Salgado, J.M. Recent advances in production of lignocellulolytic enzymes by solid-state fermentation of agro-industrial wastes. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 27. [CrossRef]

- Edo, G.I.; Nwachukwu, S.C.; Ali, A.B.M.; Yousif, E.; Jikah, A.N.; Zainulabdeen, K.; Ekokotu, H.A.; Isoje, E.F.; Igbuku, U.A.; Opiti, R.A.; et al. A Review on the Composition, Extraction and Applications of Phenolic Compounds. Ecological Frontiers 2025, 45, 7–23.

- Wojdylo, A.; Oszmianski, J.; Czemerys, R. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 940–949. [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, G. Regulation of phenolic release in corn seeds (Zea mays L.) for improving their antioxidant activity by mix-culture fermentation with Monascus anka, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Bacillus subtilis. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 325, 334–340. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, W.; Zhang, P.; Ying, D.; Adhikari, B.; Fang, Z. Fermentation transforms the phenolic profiles and bioactivities of plant-based foods. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 49, 107763. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ling, T.-J.; Su, X.-Q.; Jiang, B.; Nian, B.; Chen, L.-J.; Liu, M.-L.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Wang, D.-P.; Mu, Y.-Y.; et al. Integrated proteomics and metabolomics analysis of tea leaves fermented by Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus tamarii and Aspergillus fumigatus. Food Chem. 2021, 334, 127560. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, W.; Zhang, P.; Ying, D.; Adhikari, B.; Fang, Z. Fermentation transforms the phenolic profiles and bioactivities of plant-based foods. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 49, 107763. [CrossRef]

- Dulf, F.V.; Vodnar, D.C.; Socaciu, C. Effects of solid-state fermentation with two filamentous fungi on the total phenolic contents, flavonoids, antioxidant activities and lipid fractions of plum fruit (Prunus domestica L.) by-products. Food Chem. 2016, 209, 27–36. [CrossRef]

- Kučera, M. The production of toxic protease by the entomopathogenous fungus Metarhizium anisopliae in submerged culture. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1981, 38, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yi, L.; Marek, P.; Iverson, B.L. Commercial proteases: Present and future. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 1155–1163. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.M.; Kumar, R.; Panwar, S.; Kumar, A. Microbial alkaline proteases: Optimization of production parameters and their properties. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2017, 15, 115–126. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Wu, Q.; Hua, L. 3.01 - Industrial Enzymes. In Comprehensive Biotechnology, 3rd ed.; Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Pergamon: Oxford, 2019; pp. 1–13.

- Leite, P.; Salgado, J.M.; Venâncio, A.; Domínguez, J.M.; Belo, I. Ultrasounds pretreatment of olive pomace to improve xylanase and cellulase production by solid-state fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 214, 737–746. [CrossRef]

- Liguori, R.; Pennacchio, A.; Vandenberghe, L.P.d.S.; De Chiaro, A.; Birolo, L.; Soccol, C.R.; Faraco, V. Screening of Fungal Strains for Cellulolytic and Xylanolytic Activities Production and Evaluation of Brewers’ Spent Grain as Substrate for Enzyme Production by Selected Fungi. Energies 2021, 14, 4443. [CrossRef]

- Global Enzymes Market in Industrial Applications Available online: https://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/biotechnology/global-markets-for-enzymes-in-industrial-applications.html (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Saldarriaga-Hernández, S.; Velasco-Ayala, C.; Flores, P.L.-I.; Rostro-Alanis, M.d.J.; Parra-Saldivar, R.; Iqbal, H.M.; Carrillo-Nieves, D. Biotransformation of lignocellulosic biomass into industrially relevant products with the aid of fungi-derived lignocellulolytic enzymes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1099–1116. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).