Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Antimicrobial Peptides, Their Assemblies and Biomedical Applications

2. Structure-Function for AMPs and Peptide Mimetics Against Pathogens and Cancer

3. Peptides and Their Assemblies for Treating Cancers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levin, A.; Hakala, T.A.; Schnaider, L.; Bernardes, G.J.L.; Gazit, E.; Knowles, T.P.J. Biomimetic Peptide Self-Assembly for Functional Materials. Nat Rev Chem 2020, 4, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonson, A.W.; Aronson, M.R.; Medina, S.H. Supramolecular Peptide Assemblies as Antimicrobial Scaffolds. Molecules 2020, 25, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juković, M.; Ratkaj, I.; Kalafatovic, D.; Bradshaw, N.J. Amyloids, Amorphous Aggregates and Assemblies of Peptides – Assessing Aggregation. Biophysical Chemistry 2024, 308, 107202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Kariuki, M.; Hall, S.C.L.; Hill, S.K.; Rho, J.Y.; Perrier, S. Molecular Self-Assembly and Supramolecular Chemistry of Cyclic Peptides. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 13936–13995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liao, M.; Gong, H.; Zhang, L.; Cox, H.; Waigh, T.A.; Lu, J.R. Recent Advances in Short Peptide Self-Assembly: From Rational Design to Novel Applications. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 2020, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, K.; Xing, R.; Yan, X. Peptide Self-Assembly: Thermodynamics and Kinetics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5589–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevi, A.S.; Sastry, G.N. Cooperativity in Noncovalent Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2775–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A.; Mondal, J.H.; Das, D. Peptide Hydrogels. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Pochan, D.J. Rheological Properties of Peptide-Based Hydrogels for Biomedical and Other Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, C.; Castellucci, N. Peptides and Peptidomimetics That Behave as Low Molecular Weight Gelators. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; He, Y.; Mao, H.; Gu, Z. Bioactive Hydrogels Based on Polysaccharides and Peptides for Soft Tissue Wound Management. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 7148–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Camacho, J.C.; Ghobril, C.; Anez-Bustillos, L.; Grinstaff, M.W.; Rodríguez, E.K.; Nazarian, A. The Efficacy of a Lysine-Based Dendritic Hydrogel Does Not Differ from Those of Commercially Available Tissue Sealants and Adhesives: An Ex Vivo Study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Mei, X.; He, Y.; Mao, H.; Tang, W.; Liu, R.; Yang, J.; Luo, K.; Gu, Z.; Zhou, L. Fast and High Strength Soft Tissue Bioadhesives Based on a Peptide Dendrimer with Antimicrobial Properties and Hemostatic Ability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 4241–4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, B.; Wu, F. Hydrogel-Based Growth Factor Delivery Platforms: Strategies and Recent Advances. Advanced Materials 2023, 2210707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, K.F.; Rodriguez, A.L.; Parish, C.L.; Williams, R.J.; Nisbet, D.R. Temporally Controlled Release of Multiple Growth Factors from a Self-Assembling Peptide Hydrogel. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 385102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Yan, X.; Su, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Solvent-Induced Structural Transition of Self-Assembled Dipeptide: From Organogels to Microcrystals. Chemistry A European J 2010, 16, 3176–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernheimer, A.W.; Rudy, B. Interactions between Membranes and Cytolytic Peptides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Biomembranes 1986, 864, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Antimicrobial Peptides and Their Assemblies. Future Pharmacology 2023, 3, 763–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portlock, S.H.; Clague, M.J.; Cherry, R.J. Leakage of Internal Markers from Erythrocytes and Lipid Vesicles Induced by Melittin, Gramicidin S and Alamethicin: A Comparative Study. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1990, 1030, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsu, T.; Kuroko, M.; Morikawa, T.; Sanchika, K.; Fujita, Y.; Yamamura, H.; Uda, M. Mechanism of Membrane Damage Induced by the Amphipathic Peptides Gramicidin S and Melittin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1989, 983, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladokhin, A.S.; Selsted, M.E.; White, S.H. Sizing Membrane Pores in Lipid Vesicles by Leakage of Co-Encapsulated Markers: Pore Formation by Melittin. Biophysical Journal 1997, 72, 1762–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, K.; Wu, F. Turning Toxicants into Safe Therapeutic Drugs: Cytolytic Peptide−Photosensitizer Assemblies for Optimized In Vivo Delivery of Melittin. Adv Healthcare Materials 2018, 7, 1800380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

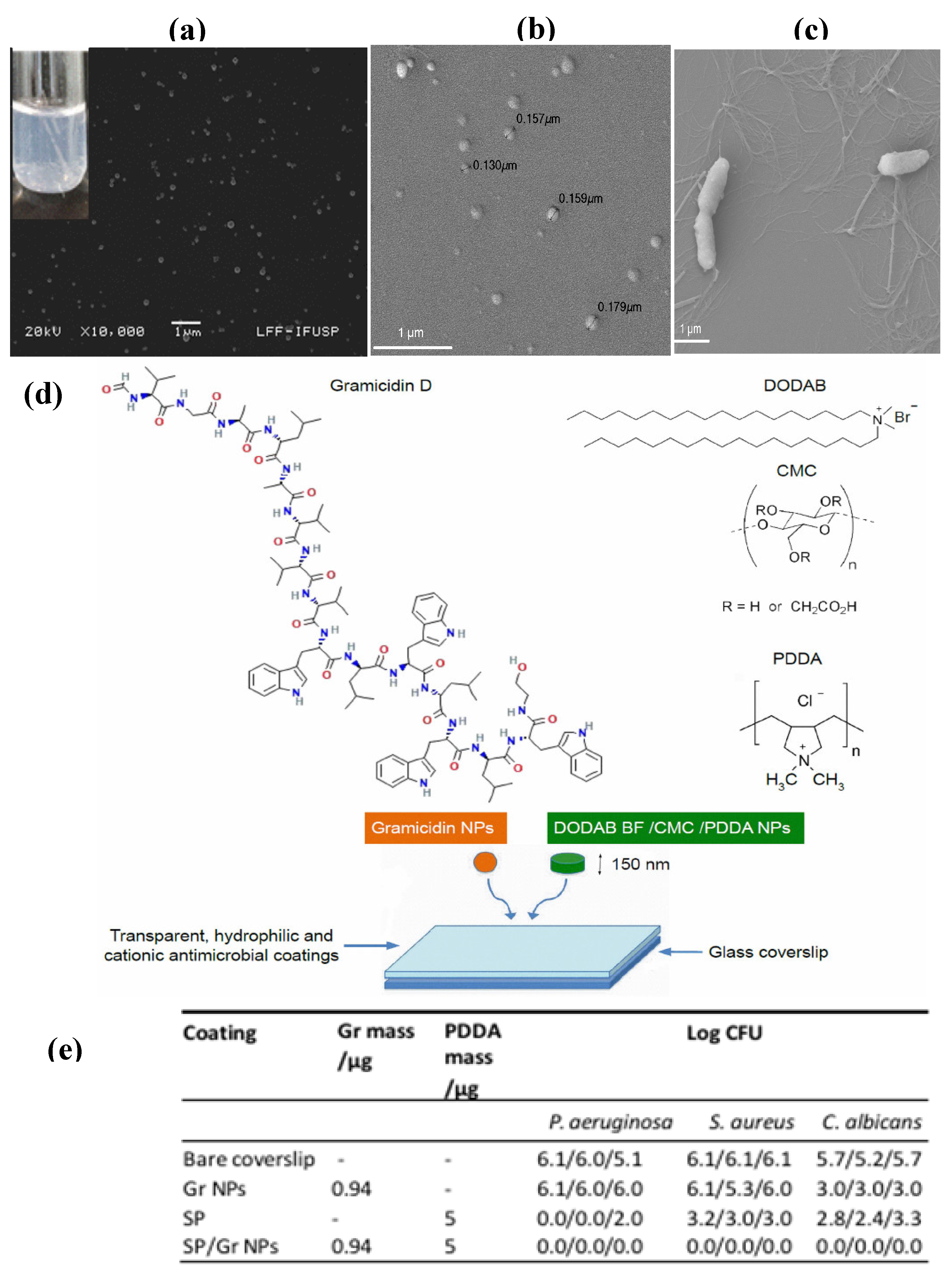

- Pérez-Betancourt, Y.; Zaia, R.; Evangelista, M.F.; Ribeiro, R.T.; Roncoleta, B.M.; Mathiazzi, B.I.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Characterization and Differential Cytotoxicity of Gramicidin Nanoparticles Combined with Cationic Polymer or Lipid Bilayer. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

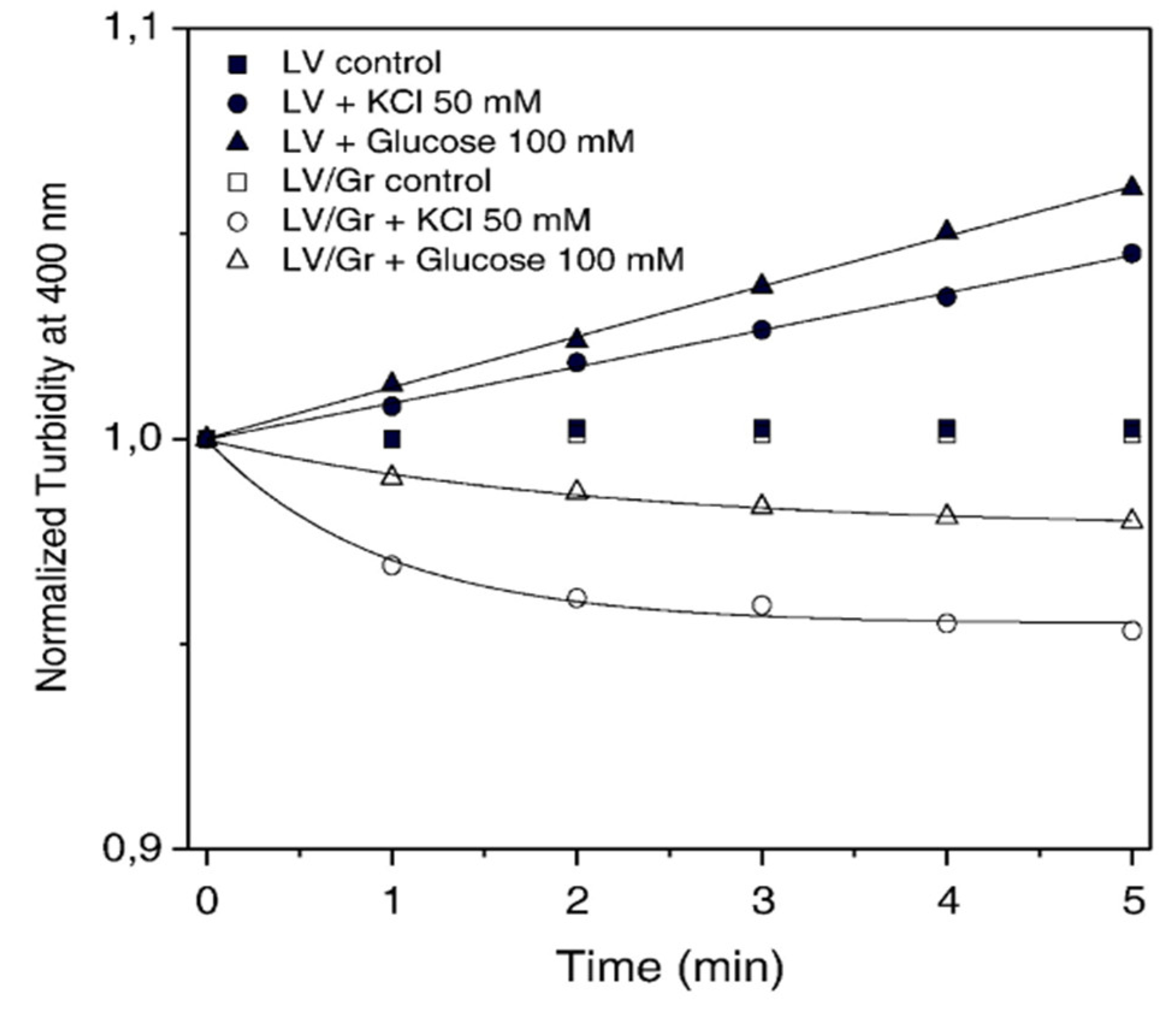

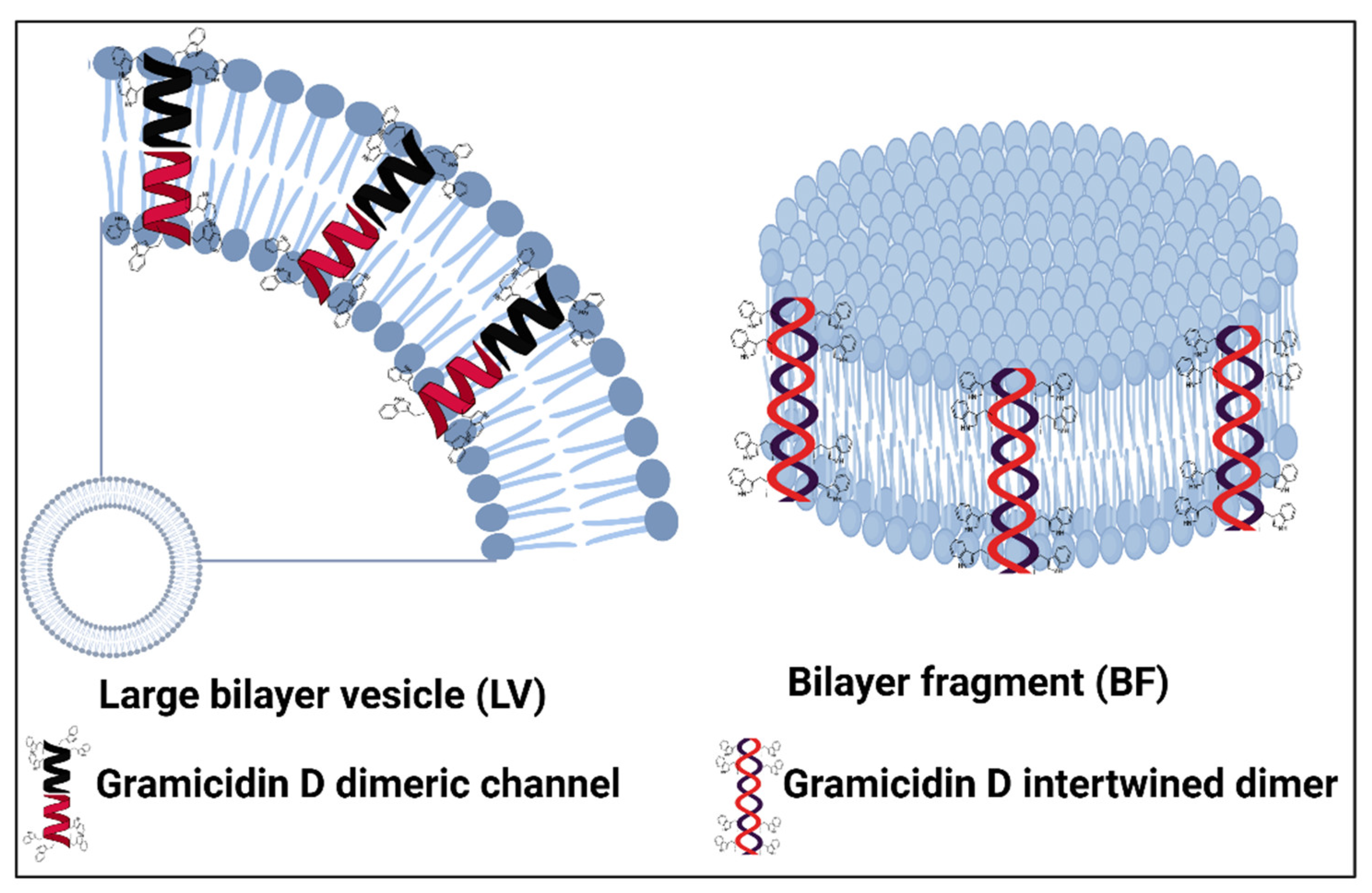

- Carvalho, C.A.; Olivares-Ortega, C.; Soto-Arriaza, M.A.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Interaction of Gramicidin with DPPC/DODAB Bilayer Fragments. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1818, 3064–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

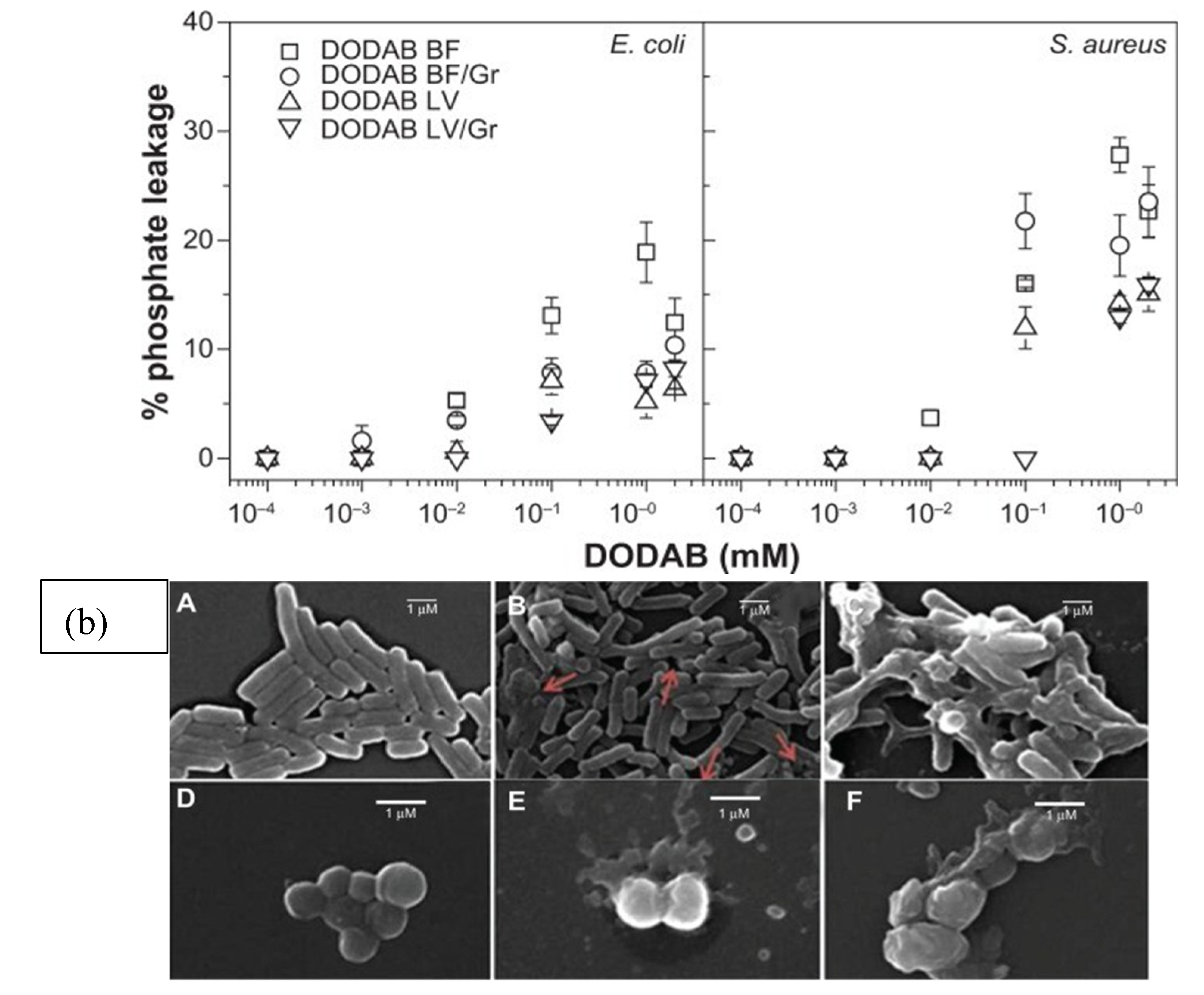

- Ragioto, D.A.; Carrasco, L.D.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Novel Gramicidin Formulations in Cationic Lipid as Broad-Spectrum Microbicidal Agents. Int J Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 3183–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M.; Midmore, B.R. Synthetic Bilayer Adsorption onto Polystyrene Microspheres. Langmuir 1992, 8, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, G.R.S.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Cationic Biomimetic Particles of Polystyrene/Cationic Bilayer/Gramicidin for Optimal Bactericidal Activity. Nanomaterials 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincopan, N.; Espíndola, N.; Vaz, A.; Carmonaribeiro, A. Cationic Supported Lipid Bilayers for Antigen Presentation. International journal of pharmaceutics 2007, 340, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.M.S.; Mamizuka, E.M.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Cationic Vesicles as Bactericides. Langmuir 1997, 13, 5583–5587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.B.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Cationic Lipids and Surfactants as Antifungal Agents: Mode of Action. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006, 58, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, L.D.; Mamizuka, E.M.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Antimicrobial Particles from Cationic Lipid and Polyelectrolytes. Langmuir 2010, 26, 12300–12306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, L.D.; Palombo, R.R.; Petri, D.F.S.; Bruns, M.; Pereira, E.M.A.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Structure–Activity Relationship for Quaternary Ammonium Compounds Hybridized with Poly(Methyl Methacrylate). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 1933–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Melo Carrasco, L.D.; Sampaio, J.L.M.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Supramolecular Cationic Assemblies against Multidrug-Resistant Microorganisms: Activity and Mechanism of Action. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 6337–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, L.D. de M.; Bertolucci, R.J.; Ribeiro, R.T.; Sampaio, J.L.M.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Cationic Nanostructures against Foodborne Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Lipid Bilayer Fragments and Disks in Drug Delivery. Curr Med Chem 2006, 13, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Bilayer-Forming Synthetic Lipids: Drugs or Carriers? Current Medicinal Chemistry 2003, 10, 2425–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, L.M.; Petri, D.F.S.; de Melo Carrasco, L.D.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. The Antimicrobial Activity of Free and Immobilized Poly (Diallyldimethylammonium) Chloride in Nanoparticles of Poly (Methylmethacrylate). Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2015, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, C.N.; Sanches, L.M.; Mathiazzi, B.I.; Ribeiro, R.T.; Petri, D.F.S.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Antimicrobial Coatings from Hybrid Nanoparticles of Biocompatible and Antimicrobial Polymers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaia, R.; Quinto, G.M.; Camargo, L.C.S.; Ribeiro, R.T.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Transient Coatings from Nanoparticles Achieving Broad-Spectrum and High Antimicrobial Performance. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, L.C.D.S.; Bazan, B.R.; Ribeiro, R.T.; Quinto, G.M.; Muniz, A.C.B.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Antimicrobial Coatings from Gramicidin D Nanoparticles and Polymers. RSC Pharm. 2024. 10.1039.D4PM00124A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, C.N.C.; Soto, M.A.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Characterization of DODAB/DPPC Vesicles. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 2008, 152, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona Ribeiro, A.M.; Chaimovich, H. Preparation and Characterization of Large Dioctadecyldimethylammonium Chloride Liposomes and Comparison with Small Sonicated Vesicles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1983, 733, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Ahmad Khan, M.S.; Singh Cameotra, S.; Safar Al-Thubiani, A. Biosurfactants: Potential Applications as Immunomodulator Drugs. Immunology Letters 2020, 223, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceresa, C.; Fracchia, L.; Sansotera, A.C.; De Rienzo, M.A.D.; Banat, I.M. Harnessing the Potential of Biosurfactants for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pueyo, M.T.; Mutafci, B.A.; Soto-Arriaza, M.A.; Di Mascio, P.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. The Self-Assembly of a Cyclic Lipopeptides Mixture Secreted by a B. Megaterium Strain and Its Implications on Activity against a Sensitive Bacillus Species. PLoS One 2014, 9, e97261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pueyo, M.T.; Bloch, C.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M.; di Mascio, P. Lipopeptides Produced by a Soil Bacillus Megaterium Strain. Microb Ecol 2009, 57, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banat, I.M.; Franzetti, A.; Gandolfi, I.; Bestetti, G.; Martinotti, M.G.; Fracchia, L.; Smyth, T.J.; Marchant, R. Microbial Biosurfactants Production, Applications and Future Potential. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 87, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; De Bruijn, I.; Nybroe, O.; Ongena, M. Natural Functions of Lipopeptides from Bacillus and Pseudomonas: More than Surfactants and Antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2010, 34, 1037–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubetič, A.; Gradišar, H.; Jerala, R. Advances in Design of Protein Folds and Assemblies. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2017, 40, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

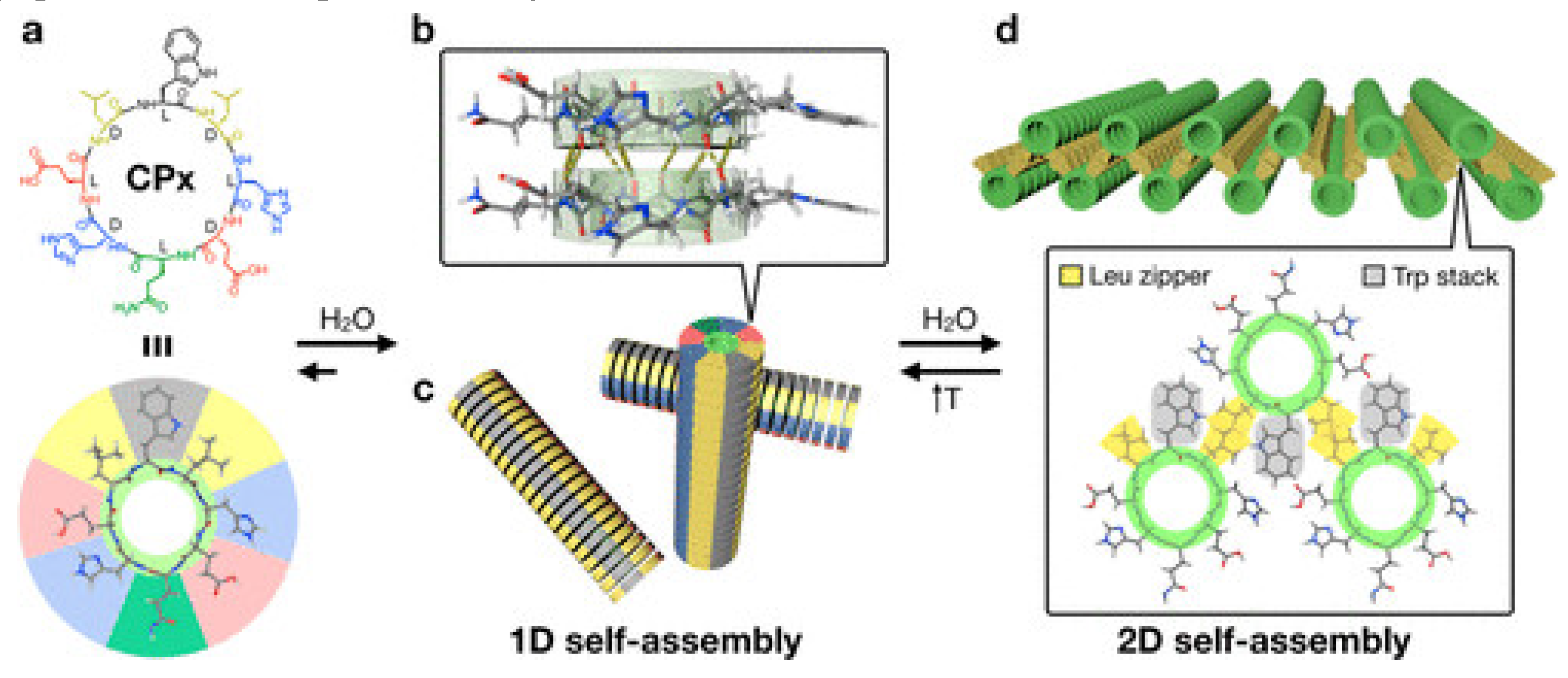

- Insua, I.; Montenegro, J. 1D to 2D Self Assembly of Cyclic Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.M.; Shi, J.; Ceccarelli, A.; Kim, Y.-H.; Park, A.; Ganz, T. Inhibition of Neutrophil Elastase Prevents Cathelicidin Activation and Impairs Clearance of Bacteria from Wounds. Blood 2001, 97, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groisman, E.A.; Parra-Lopez, C.; Salcedo, M.; Lipps, C.J.; Heffron, F. Resistance to Host Antimicrobial Peptides Is Necessary for Salmonella Virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89, 11939–11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, D.; Bandholtz, L.; Nilsson, J.; Wigzell, H.; Christensson, B.; Agerberth, B.; Gudmundsson, G.H. Downregulation of Bactericidal Peptides in Enteric Infections: A Novel Immune Escape Mechanism with Bacterial DNA as a Potential Regulator. Nat Med 2001, 7, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bals, R.; Weiner, D.J.; Meegalla, R.L.; Wilson, J.M. Transfer of a Cathelicidin Peptide Antibiotic Gene Restores Bacterial Killing in a Cystic Fibrosis Xenograft Model. J. Clin. Invest. 1999, 103, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowdish, D.M.E.; Davidson, D.J.; Lau, Y.E.; Lee, K.; Scott, M.G.; Hancock, R.E.W. Impact of LL-37 on Anti-Infective Immunity. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2004, 77, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilchie, A.L.; Wuerth, K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Immune Modulation by Multifaceted Cationic Host Defense (Antimicrobial) Peptides. Nat Chem Biol 2013, 9, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M.; De Melo Carrasco, L.D. Novel Formulations for Antimicrobial Peptides. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2014, 15, 18040–18083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Self-Assembled Antimicrobial Nanomaterials. IJERPH 2018, 15, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

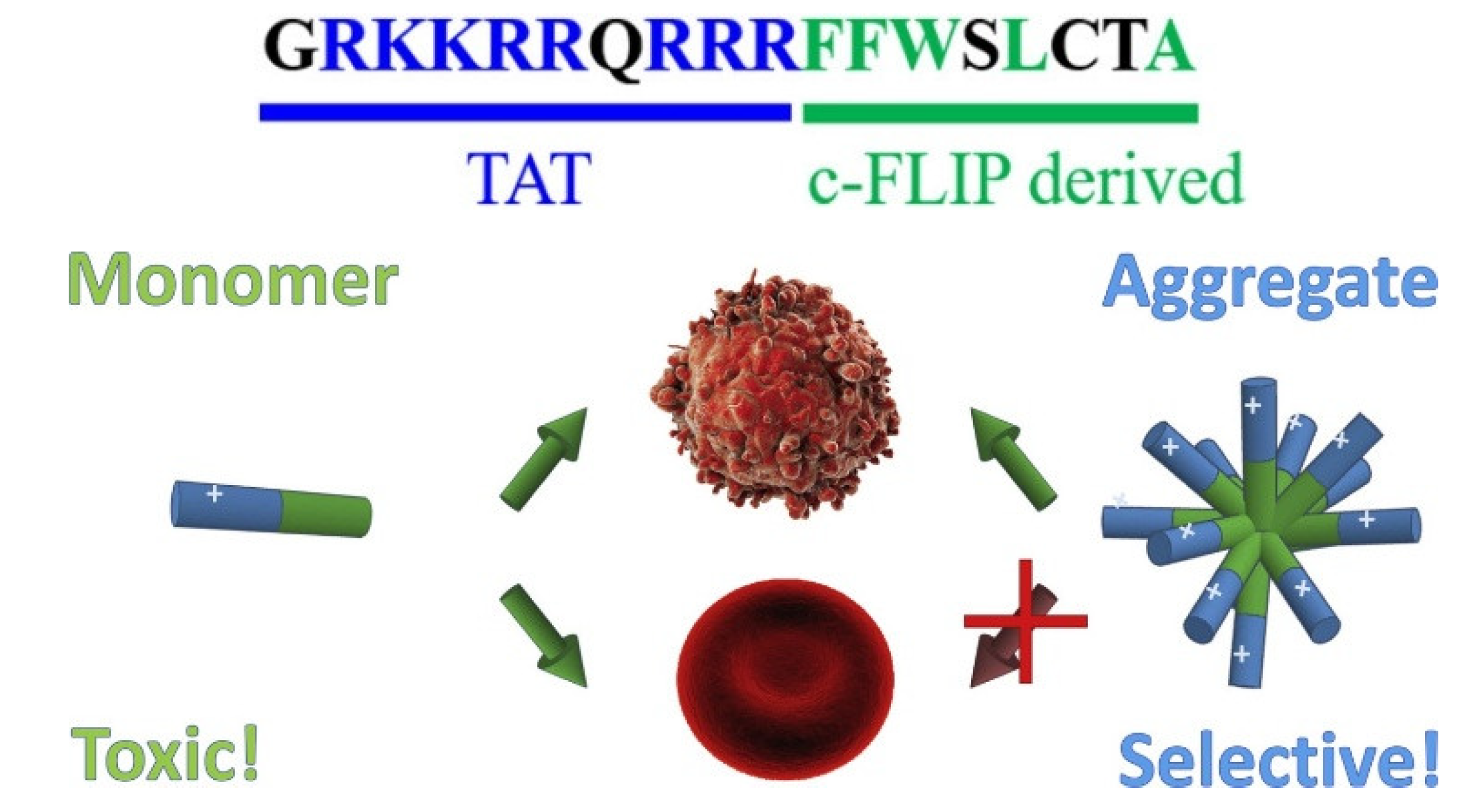

- Pennarun, B.; Gaidos, G.; Bucur, O.; Tinari, A.; Rupasinghe, C.; Jin, T.; Dewar, R.; Song, K.; Santos, M.T.; Malorni, W.; et al. killerFLIP: A Novel Lytic Peptide Specifically Inducing Cancer Cell Death. Cell Death Dis 2013, 4, e894–e894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, Z.; Bortolotti, A.; Luca, V.; Perilli, G.; Mangoni, M.L.; Khosravi-Far, R.; Bobone, S.; Stella, L. Aggregation Determines the Selectivity of Membrane-Active Anticancer and Antimicrobial Peptides: The Case of killerFLIP. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2020, 1862, 183107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, M.F.; Anton, N.; Wallyn, J.; Omran, Z.; Vandamme, T.F. An Overview of Active and Passive Targeting Strategies to Improve the Nanocarriers Efficiency to Tumour Sites. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2019, 71, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

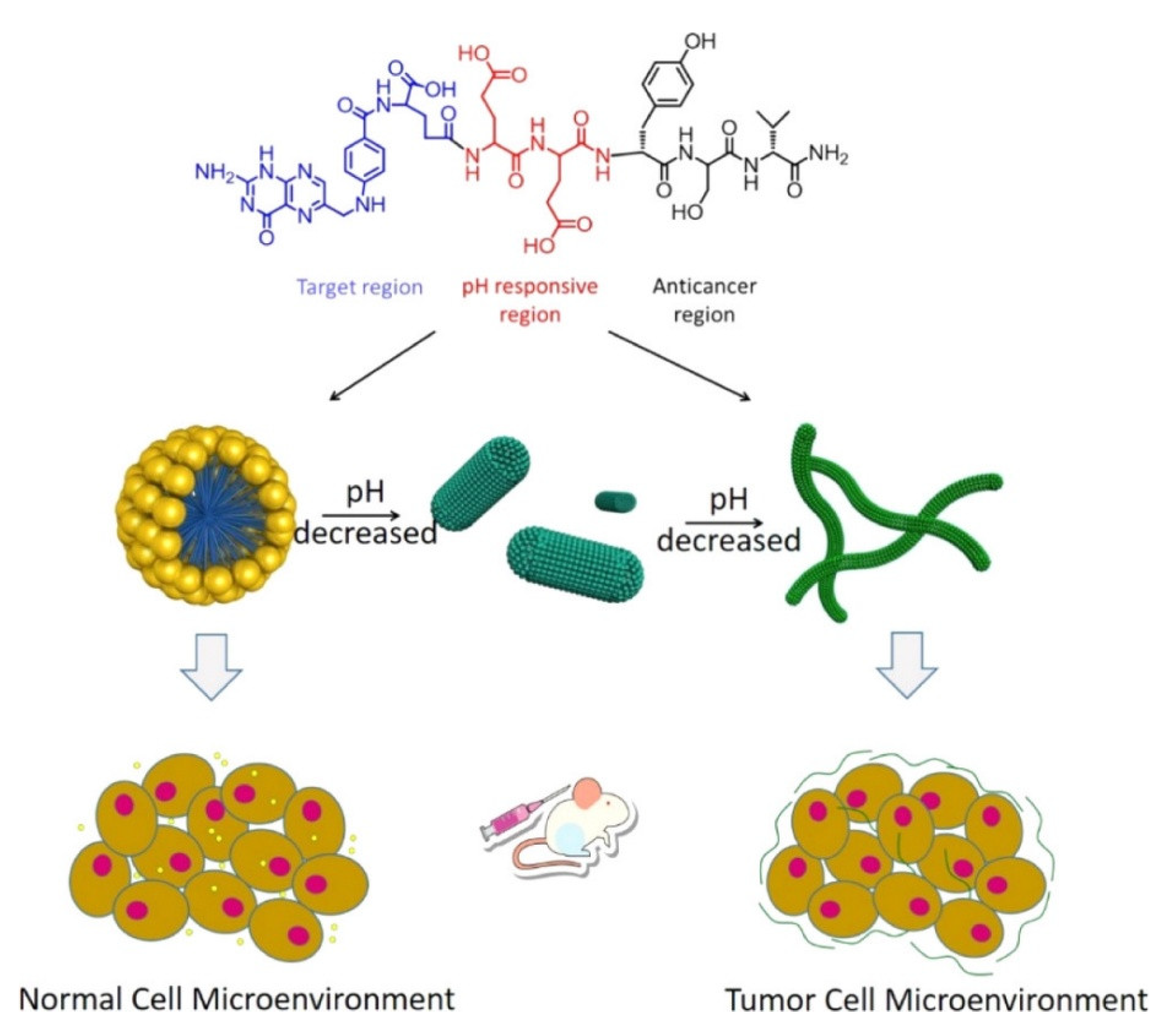

- Wang, D.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Cao, M.; Wei, G.; Wang, J. pH-Responsive Self-Assemblies from the Designed Folic Acid-Modified Peptide Drug for Dual-Targeting Delivery. Langmuir 2021, 37, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

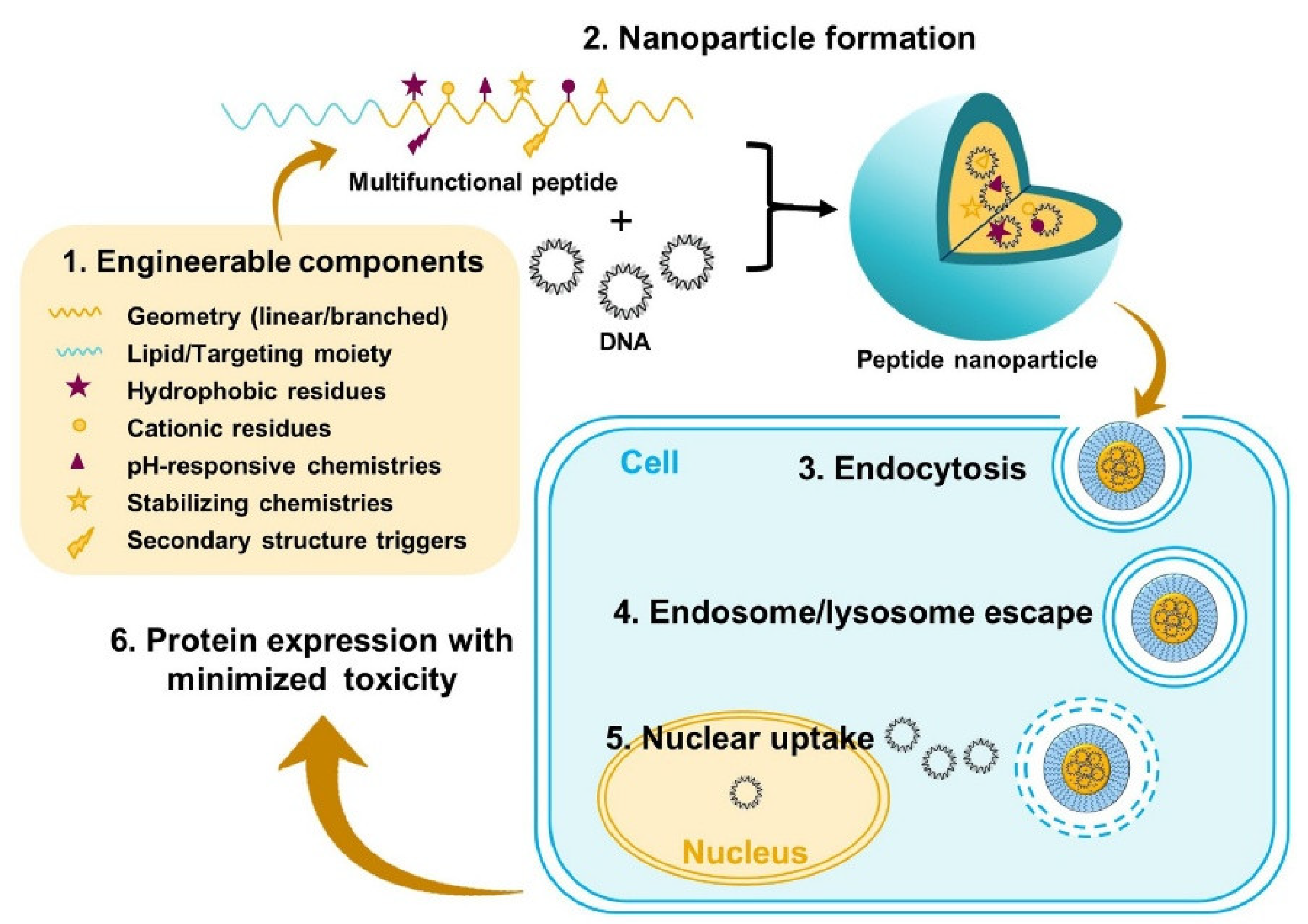

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Cao, M. Application of Peptides in Construction of Nonviral Vectors for Gene Delivery. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urello, M.; Hsu, W.-H.; Christie, R.J. Peptides as a Material Platform for Gene Delivery: Emerging Concepts and Converging Technologies. Acta Biomaterialia 2020, 117, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, A.; Kumar, V.B.; Tiwari, O.S.; Rencus-Lazar, S.; Chen, Y.; Ozguney, B.; Gazit, E.; Tamamis, P. Co-Assembly of Cancer Drugs with Cyclo-HH Peptides: Insights from Simulations and Experiments. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 2309–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryyma, A.; Matinkhoo, K.; Bu, Y.J.; Merkens, H.; Zhang, Z.; Bénard, F.; Perrin, D.M. Synthesis and Preliminary Evaluation of Octreotate Conjugates of Bioactive Synthetic Amatoxins for Targeting Somatostatin Receptor (Sstr2) Expressing Cells. RSC Chem. Biol. 2022, 3, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hwang, D.; Choi, M.; Lee, S.; Kang, S.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Chung, J.; Jon, S. Antibody-Assisted Delivery of a Peptide–Drug Conjugate for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2019, 16, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, M.; Yin, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Cheng, Y. Peptide-Drug Conjugates: A New Paradigm for Targeted Cancer Therapy. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2024, 265, 116119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mező, G.; Gomena, J.; Ranđelović, I.; Dókus, E.; Kiss, K.; Pethő, L.; Schuster, S.; Vári, B.; Vári-Mező, D.; Lajkó, E.; et al. Oxime-Linked Peptide–Daunomycin Conjugates as Good Tools for Selection of Suitable Homing Devices in Targeted Tumor Therapy: An Overview. IJMS 2024, 25, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. The Development of Peptide-Drug Conjugates (PDCs) Strategies for Paclitaxel. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery 2022, 19, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Pei, P.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Luo, S.; Chen, L. A Single-chain Variable Fragment-anticancer Lytic Peptide (scFv-ACLP) Fusion Protein for Targeted Cancer Treatment. Chem Biol Drug Des 2023, 101, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeule, M.; Currie, J.; Bertrand, Y.; Ché, C.; Nguyen, T.; Régina, A.; Gabathuler, R.; Castaigne, J.; Béliveau, R. Involvement of the Low-density Lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein in the Transcytosis of the Brain Delivery Vector Angiopep. Journal of Neurochemistry 2008, 106, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demeule, M.; Régina, A.; Ché, C.; Poirier, J.; Nguyen, T.; Gabathuler, R.; Castaigne, J.-P.; Béliveau, R. Identification and Design of Peptides as a New Drug Delivery System for the Brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2008, 324, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pethő, L.; Oláh-Szabó, R.; Mező, G. Influence of the Drug Position on Bioactivity in Angiopep-2—Daunomycin Conjugates. IJMS 2023, 24, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, I.; Kocik-Krol, J.; Skalniak, L.; Musielak, B.; Wisniewska, A.; Ciesiołkiewicz, A.; Berlicki, Ł.; Plewka, J.; Grudnik, P.; Stec, M.; et al. Structural and Biological Characterization of pAC65, a Macrocyclic Peptide That Blocks PD-L1 with Equivalent Potency to the FDA-Approved Antibodies. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Y.-B.; Jiang, T. Design of Cell-Specific Targeting Peptides for Cancer Therapy. Targets 2024, 2, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Epps, H.L. René Dubos: Unearthing Antibiotics. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2006, 203, 259–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, D.A.; Chattopadhyay, A. The Gramicidin Ion Channel: A Model Membrane Protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007, 1768, 2011–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeppe, R.E.; Anderson, O.S. Engineering the Gramicidin Channel. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure 1996, 25, 231–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greathouse, D.V.; Koeppe, R.E.; Providence, L.L.; Shobana, S.; Andersen, O.S. [28] Design and Characterization of Gramicidin Channels. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 1999; Vol. 294, pp. 525–550 ISBN 978-0-12-182195-1.

- Brownd, M.; McKay, M.J.; Greathouse, D.V.; Andersen, O.S.; Koeppe, R.E. Gramicidin Subunits That Cross Membranes and Form Ion Channels. Biophysical Journal 2018, 114, 454a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinem, C.; Janshoff, A.; Ulrich, W.P.; Sieber, M.; Galla, H.J. Impedance Analysis of Supported Lipid Bilayer Membranes: A Scrutiny of Different Preparation Techniques. Biochim Biophys Acta 1996, 1279, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, E.K.; Weichbrodt, C.; Steinem, C. Impedance Analysis of Gramicidin D in Pore-Suspending Membranes. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B.W.; Hladky, S.B.; Haydon, D.A. Ion Movements in Gramicidin Pores. An Example of Single-File Transport. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1980, 602, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Chattopadhyay, A. Motionally Restricted Tryptophan Environments at the Peptide-Lipid Interface of Gramicidin Channels. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 5089–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M. Chapter 1 - Immunoadjuvants for Cancer Immunotherapy. In Nanomedicine in Cancer Immunotherapy; Kesharwani, P., Ed.; Academic Press, 2024; pp. 1–36 ISBN 978-0-443-18770-4.

- Abdelhamid, H.N.; Khan, M.S.; Wu, H.-F. Graphene Oxide as a Nanocarrier for Gramicidin (GOGD) for High Antibacterial Performance. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 50035–50046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambucci, M.; Gentili, P.L.; Sassi, P.; Latterini, L. A Multi-Spectroscopic Approach to Investigate the Interactions between Gramicidin A and Silver Nanoparticles. Soft Matter 2019, 15, 6571–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.W.; Zhou, Z.; Breaker, R.R. Gramicidin D Enhances the Antibacterial Activity of Fluoride. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2014, 24, 2969–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.M.; Rajasekaran, A.K. Gramicidin A: A New Mission for an Old Antibiotic. J Kidney Cancer VHL 2015, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, D.; Arachchige, M.C.M.; Lu, A.; Reshetnyak, Y.K.; Andreev, O.A. pH Dependent Transfer of Nano-Pores into Membrane of Cancer Cells to Induce Apoptosis. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.M.; Owens, T.A.; Barwe, S.P.; Rajasekaran, A.K. Gramicidin A Induces Metabolic Dysfunction and Energy Depletion Leading to Cell Death in Renal Cell Carcinoma Cells. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2013, 12, 2296–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoyang, W.-W.; Xiao, Q.; Ye, Z.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, D.-W.; Li, J.; Xiao, L.; Li, Z.-T.; Hou, J.-L. Gramicidin A-Based Unimolecular Channel: Cancer Cell-Targeting Behavior and Ion Transport-Induced Apoptosis. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 1097–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadnes, B.; Rekdal, Ø.; Uhlin-Hansen, L. The Anticancer Activity of Lytic Peptides Is Inhibited by Heparan Sulfate on the Surface of the Tumor Cells. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raileanu, M.; Popescu, A.; Bacalum, M. Antimicrobial Peptides as New Combination Agents in Cancer Therapeutics: A Promising Protocol against HT-29 Tumoral Spheroids. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 6964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.-W.; Itoh, H.; Dan, S.; Inoue, M. Gramicidin A Accumulates in Mitochondria, Reduces ATP Levels, Induces Mitophagy, and Inhibits Cancer Cell Growth. Chem Sci 2022, 13, 7482–7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yu, K.; Cao, X.; Su, F.; Xu, H.; Peng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Qian, F.; et al. Gramicidin Inhibits Human Gastric Cancer Cell Proliferation, Cell Cycle and Induced Apoptosis. Biol Res 2019, 52, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altin-Celik, P.; Eken, A.; Derya-Andeden, M.; Eciroglu, H.; Uzen, R.; Donmez-Altuntas, H. Iturin A and Gramicidin A Inhibit Proliferation, Trigger Apoptosis, and Regulate Inflammation in Breast Cancer Cells. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2024, 100, 106121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubin, R.; Uljanovs, R.; Strumfa, I. Cancer Stem Cells in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 7030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-Q.; Geng, J.; Sheng, W.-J.; Liu, X.-J.; Jiang, M.; Zhen, Y.-S. The Ionophore Antibiotic Gramicidin A Inhibits Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells Associated with CD47 Down-Regulation. Cancer Cell Int 2019, 19, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maham, S.; Awan, S.N.; Adnan, F.; Kakar, S.J.; Mian, A.; Khan, D. PB1837: ANTIBIOTICS; A POSSIBLE ALTERNATE TREATMENT OPTION FOR MYELOID LEUKEMIA. Hemasphere 2023, 7, e1313111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Courvalin, P.; Dantas, G.; Davies, J.; Eisenstein, B.; Huovinen, P.; Jacoby, G.A.; Kishony, R.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Kutter, E.; et al. Tackling Antibiotic Resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011, 9, 894–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlapuu, M.; Håkansson, J.; Ringstad, L.; Björn, C. Antimicrobial Peptides: An Emerging Category of Therapeutic Agents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, W.; Mao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, K. Study on Antimicrobial Activity of Sturgeon Skin Mucus Polypeptides (Rational Design, Self-Assembly and Application). Food Chemistry: X 2024, 21, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namivandi-Zangeneh, R.; Kwan, R.J.; Nguyen, T.-K.; Yeow, J.; Byrne, F.L.; Oehlers, S.H.; Wong, E.H.H.; Boyer, C. The Effects of Polymer Topology and Chain Length on the Antimicrobial Activity and Hemocompatibility of Amphiphilic Ternary Copolymers. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M.; de Melo Carrasco, L.D. Cationic Antimicrobial Polymers and Their Assemblies. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 9906–9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, A.; Sangwan, P.; Qu, Y.; Peltier, R.; Sanchez-Cano, C.; Moat, J.; Dowson, C.G.; Williams, E.G.L.; Locock, K.E.S.; Hartlieb, M.; et al. Sequence Control as a Powerful Tool for Improving the Selectivity of Antimicrobial Polymers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 40117–40126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroque, S.; Reifarth, M.; Sperling, M.; Kersting, S.; Klöpzig, S.; Budach, P.; Storsberg, J.; Hartlieb, M. Impact of Multivalence and Self-Assembly in the Design of Polymeric Antimicrobial Peptide Mimics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 30052–30065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoshin, A.S.; Kudryakova, I.V.; Borovikova, A.O.; Suzina, N.E.; Toropygin, I.Yu.; Shishkova, N.A.; Vasilyeva, N.V. Lytic Potential of Lysobacter Capsici VKM B-2533T: Bacteriolytic Enzymes and Outer Membrane Vesicles. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 9944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, A.; Castelletto, V.; De Sousa, A.; Karatzas, K.-A.; Wilkinson, C.; Khunti, N.; Seitsonen, J.; Hamley, I.W. Self-Assembly and Antimicrobial Activity of Lipopeptides Containing Lysine-Rich Tripeptides. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhong, J.-H.; Chi, Y.-H.; Li, W.-C.; Lin, T.-H.; Huang, K.-Y.; Lee, T.-Y. dbAMP: An Integrated Resource for Exploring Antimicrobial Peptides with Functional Activities and Physicochemical Properties on Transcriptome and Proteome Data. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, D285–D297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.; Guo, H.; Zingl, F.G.; Zhang, S.; Toska, J.; Xu, B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, P.; Waldor, M.K.; Zhao, W.; et al. Synthetic Peptides That Form Nanostructured Micelles Have Potent Antibiotic and Antibiofilm Activity against Polymicrobial Infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120, e2219679120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, G.R.; Lehár, J.; Keith, C.T. Multi-Target Therapeutics: When the Whole Is Greater than the Sum of the Parts. Drug Discovery Today 2007, 12, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, T.-C. Theoretical Basis, Experimental Design, and Computerized Simulation of Synergism and Antagonism in Drug Combination Studies. Pharmacol Rev 2006, 58, 621–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zharkova, M.S.; Orlov, D.S.; Golubeva, O.Yu.; Chakchir, O.B.; Eliseev, I.E.; Grinchuk, T.M.; Shamova, O.V. Application of Antimicrobial Peptides of the Innate Immune System in Combination With Conventional Antibiotics—A Novel Way to Combat Antibiotic Resistance? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudoroiu, E.-E.; Dinu-Pîrvu, C.-E.; Albu Kaya, M.G.; Popa, L.; Anuța, V.; Prisada, R.M.; Ghica, M.V. An Overview of Cellulose Derivatives-Based Dressings for Wound-Healing Management. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondaveeti, S.; Damato, T.C.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M.; Sierakowski, M.R.; Petri, D.F.S. Sustainable Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose/Xyloglucan/Gentamicin Films with Antimicrobial Properties. Carbohydr Polym 2017, 165, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondaveeti, S.; Bueno, P.V. de A.; Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M.; Esposito, F.; Lincopan, N.; Sierakowski, M.R.; Petri, D.F.S. Microbicidal Gentamicin-Alginate Hydrogels. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 186, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, Z. Tailoring the Swelling-Shrinkable Behavior of Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Advanced Science 2023, 10, 2303326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valour, F.; Bouaziz, A.; Karsenty, J.; Ader, F.; Lustig, S.; Laurent, F.; Chidiac, C.; Ferry, T. Determinants of Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus Aureusnative Bone and Joint Infection Treatment Failure: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiter, N.; Walter, G.; Bösebeck, H.; Vogt, S.; Büchner, H.; Hirschberger, W.; Hoffmann, R. Clinical Use and Safety of a Novel Gentamicin-Releasing Resorbable Bone Graft Substitute in the Treatment of Osteomyelitis/Osteitis. Bone & Joint Research 2014, 3, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Jiang, D.; Yan, L.; Wu, J. In Vitro and in Vivo Drug Release and Antibacterial Properties of the Novel Vancomycin-Loaded Bone-like Hydroxyapatite/Poly Amino Acid Scaffold. IJN 2017, Volume 12, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Starr, C.G.; Troendle, E.; Wiedman, G.; Wimley, W.C.; Ulmschneider, J.P.; Ulmschneider, M.B. Simulation-Guided Rational de Novo Design of a Small Pore-Forming Antimicrobial Peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4839–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Ouyang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ba, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, P.; Yang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Novel β-Hairpin Antimicrobial Peptide Containing the β-Turn Sequence of -NG- and the Tryptophan Zippers Facilitate Self-Assembly into Nanofibers, Exhibiting Excellent Antimicrobial Performance. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 6365–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, P.; Carter, J.; Li, Z.; Waigh, T.A.; Lu, J.R.; Xu, H. Surfactant-like Peptides: From Molecular Design to Controllable Self-Assembly with Applications. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2020, 421, 213418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsopoulos, S.; Kaiser, L.; Eriksson, H.M.; Zhang, S. Designer Peptidesurfactants Stabilize Diverse Functional Membrane Proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Dong, S.; Zheng, J.; Li, D.; Li, F.; Luo, Z. Expression, Stabilization and Purification of Membrane Proteins via Diverse Protein Synthesis Systems and Detergents Involving Cell-Free Associated with Self-Assembly Peptide Surfactants. Biotechnology Advances 2014, 32, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd-o, J.; Roy, A.; Siddiqui, Z.; Jafari, R.; Coppola, F.; Ramasamy, S.; Kolloli, A.; Kumar, D.; Kaundal, S.; Zhao, B.; et al. Antiviral Fibrils of Self-Assembled Peptides with Tunable Compositions. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyerstedt, S.; Casaro, E.B.; Rangel, É.B. COVID-19: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) Expression and Tissue Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2021, 40, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, M.K.; Park, J.; Yoon, H.Y.; Lee, S.; Um, W.; Kim, J.-H.; Kang, S.-W.; Seo, J.-W.; Hyun, S.-W.; Park, J.H.; et al. Carrier-Free Nanoparticles of Cathepsin B-Cleavable Peptide-Conjugated Doxorubicin Prodrug for Cancer Targeting Therapy. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 294, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Cao, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, P.; Xu, K.; Tang, B. Targeting Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization to Induce and Image Apoptosis in Cancer Cells by Multifunctional Au–ZnO Hybrid Nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

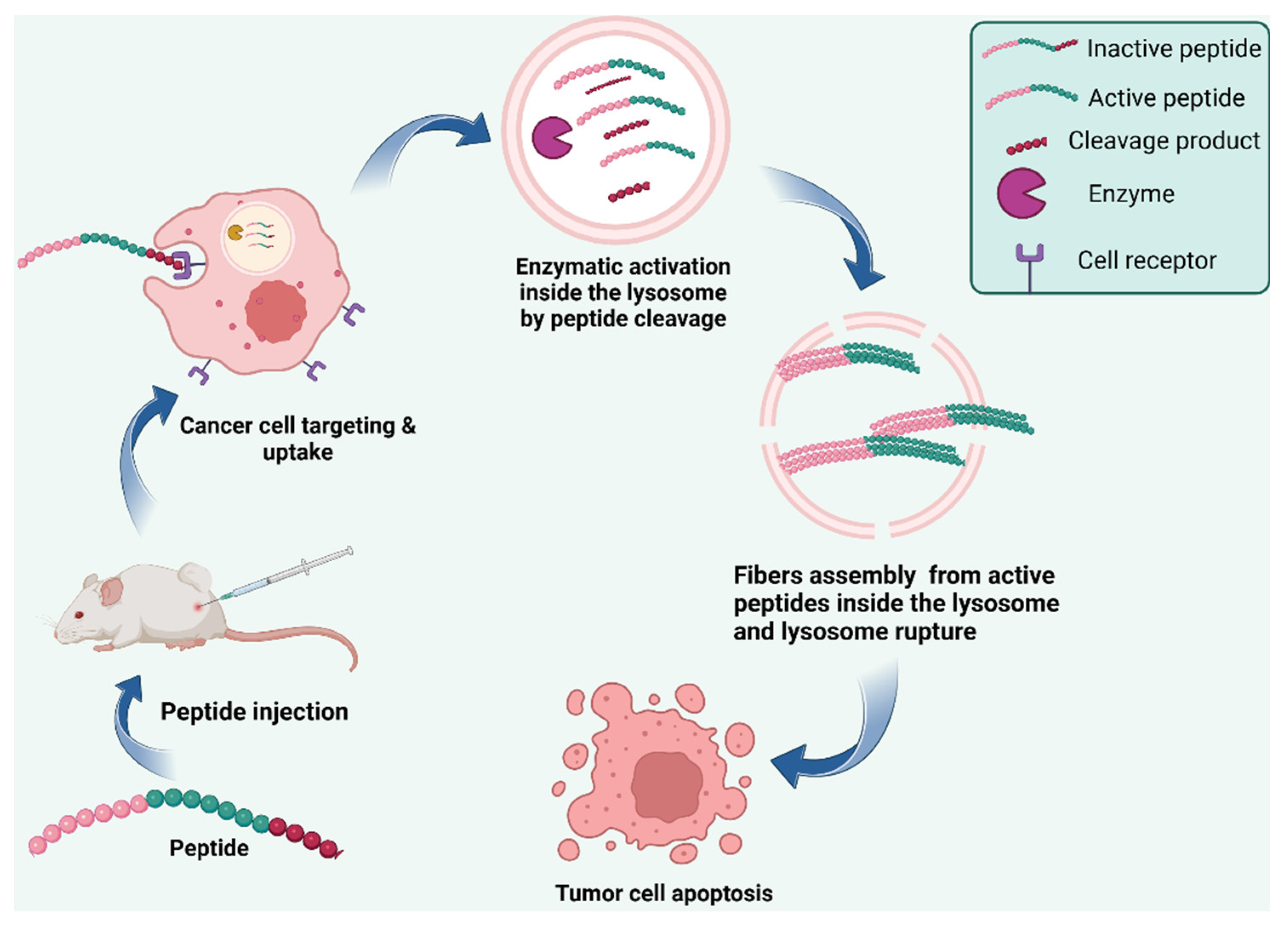

- Jana, B.; Jin, S.; Go, E.M.; Cho, Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Kwak, S.K.; Ryu, J.-H. Intra-Lysosomal Peptide Assembly for the High Selectivity Index against Cancer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 18414–18431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, N.; Gupta, P.; Pramanik, B.; Ahmed, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Ukil, A.; Das, D. Hydrogelation of a Naphthalene Diimide Appended Peptide Amphiphile and Its Application in Cell Imaging and Intracellular pH Sensing. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 3630–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesk, J.; Donahue, D.; Ross, J.; Sheehan, C.; Bennett, Z.; Armknecht, K.; Kudary, C.; Hopf, J.; Ploplis, V.A.; Castellino, F.J.; et al. Antimicrobial Peptide-Conjugated Phage-Mimicking Nanoparticles Exhibit Potent Bactericidal Action against Streptococcus Pyogenes in Murine Wound Infection Models. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 1145–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koul, A.; Arnoult, E.; Lounis, N.; Guillemont, J.; Andries, K. The Challenge of New Drug Discovery for Tuberculosis. Nature 2011, 469, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, D.J.; Gwynn, M.N.; Holmes, D.J.; Pompliano, D.L. Drugs for Bad Bugs: Confronting the Challenges of Antibacterial Discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007, 6, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batt, S.M.; Burke, C.E.; Moorey, A.R.; Besra, G.S. Antibiotics and Resistance: The Two-Sided Coin of the Mycobacterial Cell Wall. Cell Surf 2020, 6, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loessner, M.J. Bacteriophage Endolysins — Current State of Research and Applications. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2005, 8, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Caballero, S.; Chmielowska, C.; Quiles-Puchalt, N.; Brady, A.; Del Sol, F.G.; Mancheño-Bonillo, J.; Felipe-Ruíz, A.; Meijer, W.J.J.; Penadés, J.R.; Marina, A. Antagonistic Interactions between Phage and Host Factors Control Arbitrium Lysis–Lysogeny Decision. Nat Microbiol 2024, 9, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, G.; Jain, V. An Intramolecular Cross-Talk in D29 Mycobacteriophage Endolysin Governs the Lytic Cycle and Phage-Host Population Dynamics. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadh9812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Jia, H.; Duan, Q.; Wu, F. Nanomedicines for Combating Multidrug Resistance of Cancer. WIREs Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2021, 13, e1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.M.; Sforça, M.L.; Amino, R.; Juliano, M.A.; Oyama, S.; Juliano, L.; Pertinhez, T.A.; Spisni, A.; Schenkman, S. Lytic Activity and Structural Differences of Amphipathic Peptides Derived from Trialysin , Biochemistry 2006, 45, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.-Y.; Dong, D.-R.; Fan, G.; Dai, M.-Y.; Liu, M. A Cyclic Peptide-Based PROTAC Induces Intracellular Degradation of Palmitoyltransferase and Potently Decreases PD-L1 Expression in Human Cervical Cancer Cells. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1237964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberwal, G.; Nagaraj, R. Cell-Lytic and Antibacterial Peptides That Act by Perturbing the Barrier Function of Membranes: Facets of Their Conformational Features, Structure-Function Correlations and Membrane-Perturbing Abilities. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Biomembranes 1994, 1197, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

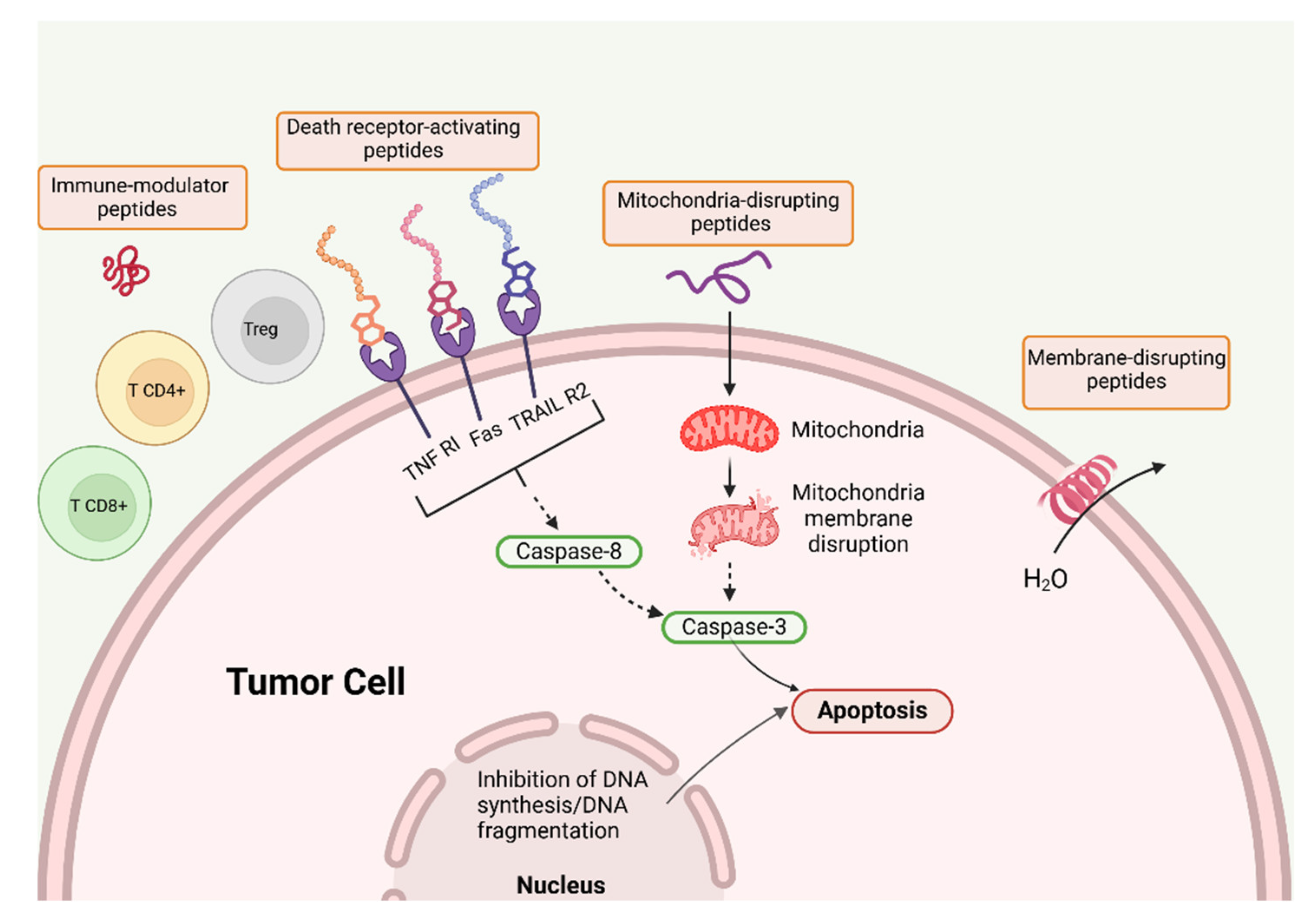

- Leuschner, C.; Hansel, W. Membrane Disrupting Lytic Peptides for Cancer Treatments. CPD 2004, 10, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechinger, B. Structure and Function of Membrane-Lytic Peptides. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2004, 23, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shen, W.; Liu, W.; Yang, Z.; Yin, D.; Xiao, C. From Oncolytic Peptides to Oncolytic Polymers: A New Paradigm for Oncotherapy. Bioactive Materials 2024, 31, 206–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira-da-Silva, B.; Castanho, M.A.R.B. The Structure and Matrix Dynamics of Bacterial Biofilms as Revealed by Antimicrobial Peptides’ Diffusion. Journal of Peptide Science 2023, 29, e3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, W.; Enright, F.; Leuschner, C. Destruction of Breast Cancers and Their Metastases by Lytic Peptide Conjugates in Vitro and in Vivo. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2007, 260–262, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulla, M.G.; Gelain, F. Structure–Activity Relationships of Antibacterial Peptides. Microbial Biotechnology 2023, 16, 757–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Dutta, D. Action of Antimicrobial Peptides against Bacterial Biofilms. Materials (Basel) 2018, 11, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, J.T.C.D.; Toledo Borges, A.B.; Roque-Borda, C.A.; Pavan, F.R. Antimicrobial Peptides as an Alternative for the Eradication of Bacterial Biofilms of Multi-Drug Resistant Bacteria. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raucher, D.; Ryu, J.S. Cell-Penetrating Peptides: Strategies for Anticancer Treatment. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2015, 21, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankel, A.D.; Pabo, C.O. Cellular Uptake of the Tat Protein from Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Cell 1988, 55, 1189–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami Fath, M.; Babakhaniyan, K.; Zokaei, M.; Yaghoubian, A.; Akbari, S.; Khorsandi, M.; Soofi, A.; Nabi-Afjadi, M.; Zalpoor, H.; Jalalifar, F.; et al. Anti-Cancer Peptide-Based Therapeutic Strategies in Solid Tumors. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2022, 27, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, N.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Pan, X. The Recent Advance of Cell-Penetrating and Tumor-Targeting Peptides as Drug Delivery Systems Based on Tumor Microenvironment. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2023, 20, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.H.; Meneguetti, B.T.; Costa, B.O.; Buccini, D.F.; Oshiro, K.G.N.; Preza, S.L.E.; Carvalho, C.M.E.; Migliolo, L.; Franco, O.L. Non-Lytic Antibacterial Peptides That Translocate Through Bacterial Membranes to Act on Intracellular Targets. IJMS 2019, 20, 4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K R, G.; Balenahalli Narasingappa, R.; Vishnu Vyas, G. Unveiling Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Peptide: Actions beyond the Membranes Disruption. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-Q.; Sun, C.; Xu, N.; Liu, W. The Current Landscape of the Antimicrobial Peptide Melittin and Its Therapeutic Potential. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1326033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.S.; Lee, C.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.J.; Heo, K. Gramicidin, a Bactericidal Antibiotic, Is an Antiproliferative Agent for Ovarian Cancer Cells. Medicina 2023, 59, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havas, L.J. Effect of Bee Venom on Colchicine-Induced Tumours. Nature 1950, 166, 567–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufson, R.A.; Laskin, J.D.; Fisher, P.B.; Weinstein, I.B. Melittin Shares Certain Cellular Effects with Phorbol Ester Tumour Promoters. Nature 1979, 280, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchebafi, A.; Tamanaee, F.; Ehteram, H.; Ahmad, E.; Nikzad, H.; Haddad Kashani, H. The Dual Interaction of Antimicrobial Peptides on Bacteria and Cancer Cells; Mechanism of Action and Therapeutic Strategies of Nanostructures. Microb Cell Fact 2022, 21, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajski, G.; Garaj-Vrhovac, V. Melittin: A Lytic Peptide with Anticancer Properties. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2013, 36, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczepanski, C.; Tenstad, O.; Baumann, A.; Martinez, A.; Myklebust, R.; Bjerkvig, R.; Prestegarden, L. Identification of a Novel Lytic Peptide for the Treatment of Solid Tumours. Genes Cancer 2014, 5, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papo, N.; Shai, Y. Host Defense Peptides as New Weapons in Cancer Treatment. CMLS, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Gueydan, C.; Han, J. Plasma Membrane Changes during Programmed Cell Deaths. Cell Res 2018, 28, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, S.; Liu, L.; Lu, L.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Z. Melittin-Lipid Nanoparticles Target to Lymph Nodes and Elicit a Systemic Anti-Tumor Immune Response. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.J.; Kia, A.F.-A.; Hassan, F.; O’Grady, S.; Morgan, M.P.; Creaven, B.S.; McClean, S.; Harmey, J.H.; Devocelle, M. Polymeric Prodrug Combination to Exploit the Therapeutic Potential of Antimicrobial Peptides against Cancer Cells. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 9278–9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S.; Szwej, E.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; O’Connor, A.; Byrne, A.T.; Devocelle, M.; O’Donovan, N.; Gallagher, W.M.; Babu, R.; Kenny, S.T.; et al. The Anti-Cancer Activity of a Cationic Anti-Microbial Peptide Derived from Monomers of Polyhydroxyalkanoate. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2710–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imura, Y.; Nishida, M.; Matsuzaki, K. Action Mechanism of PEGylated Magainin 2 Analogue Peptide. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2007, 1768, 2578–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lu, D.; Jiang, Y.; Jin, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Nagle, D.G.; et al. Stapled Wasp Venom-Derived Oncolytic Peptides with Side Chains Induce Rapid Membrane Lysis and Prolonged Immune Responses in Melanoma. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 5802–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Liu, Y.; Eskandari, A.; Ghimire, J.; Lin, L.C.; Fang, Z.; Wimley, W.C.; Ulmschneider, J.P.; Suntharalingam, K.; Hu, C.J.; et al. Integrated Design of a Membrane-Lytic Peptide-Based Intravenous Nanotherapeutic Suppresses Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Advanced Science 2022, 9, 2105506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dancey, J.E.; Chen, H.X. Strategies for Optimizing Combinations of Molecularly Targeted Anticancer Agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006, 5, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslouches, B.; Di, Y.P. Antimicrobial Peptides with Selective Antitumor Mechanisms: Prospect for Anticancer Applications. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 46635–46651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, C.; Wen, Z.; Chen, Z. Biomimetic Nanocarriers Loaded with Temozolomide by Cloaking Brain-Targeting Peptides for Targeting Drug Delivery System to Promote Anticancer Effects in Glioblastoma Cells. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, C.; Enright, F.M.; Gawronska, B.; Hansel, W. Membrane Disrupting Lytic Peptide Conjugates Destroy Hormone Dependent and Independent Breast Cancer Cells in Vitro and in Vivo. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2003, 78, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papo, N.; Shahar, M.; Eisenbach, L.; Shai, Y. A Novel Lytic Peptide Composed of Dl-Amino Acids Selectively Kills Cancer Cells in Culture and in Mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 21018–21023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Hao, J.; Kharidia, R.; Meng, X.G.; Liang, J.F. Improved Stability and Selectivity of Lytic Peptides through Self-Assembly. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2007, 361, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Chau, Y. Antitumor Activity of a Membrane Lytic Peptide Cyclized with a Linker Sensitive to Membrane Type 1-Matrix Metalloproteinase. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2008, 7, 2933–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papo, N.; Shai, Y. New Lytic Peptides Based on the d, l -Amphipathic Helix Motif Preferentially Kill Tumor Cells Compared to Normal Cells. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 9346–9354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.M.; Haratipour, P.; Lingeman, R.G.; Perry, J.J.P.; Gu, L.; Hickey, R.J.; Malkas, L.H. Novel Peptide Therapeutic Approaches for Cancer Treatment. Cells 2021, 10, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Jia, X. Research Progress Evaluating the Function and Mechanism of Anti-Tumor Peptides. CMAR 2020, Volume 12, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conibear, A.C.; Schmid, A.; Kamalov, M.; Becker, C.F.W.; Bello, C. Recent Advances in Peptide-Based Approaches for Cancer Treatment. CMC 2020, 27, 1174–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spicer, J.; Marabelle, A.; Baurain, J.-F.; Jebsen, N.L.; Jøssang, D.E.; Awada, A.; Kristeleit, R.; Loirat, D.; Lazaridis, G.; Jungels, C.; et al. Safety, Antitumor Activity, and T-Cell Responses in a Dose-Ranging Phase I Trial of the Oncolytic Peptide LTX-315 in Patients with Solid Tumors. Clinical Cancer Research 2021, 27, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.D.; Cabral, H.; Stylianopoulos, T.; Jain, R.K. Improving Cancer Immunotherapy Using Nanomedicines: Progress, Opportunities and Challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020, 17, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylösmäki, E.; Cerullo, V. Design and Application of Oncolytic Viruses for Cancer Immunotherapy. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2020, 65, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-T.; Sun, Z.-J. Turning Cold Tumors into Hot Tumors by Improving T-Cell Infiltration. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5365–5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, S.; Russo, S.; Martins, B.; Lopes, A.; Vandermeulen, G.; Fluhler, V.; De Giorgi, C.; Fusciello, M.; Pesonen, S.; Ylösmäki, E.; et al. Peptides-Coated Oncolytic Vaccines for Cancer Personalized Medicine. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 826164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rencinai, A.; Tollapi, E.; Marianantoni, G.; Brunetti, J.; Henriquez, T.; Pini, A.; Bracci, L.; Falciani, C. Branched Oncolytic Peptides Target HSPGs, Inhibit Metastasis, and Trigger the Release of Molecular Determinants of Immunogenic Cell Death in Pancreatic Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1429163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chi, J.; Yan, Y.; Luo, R.; Feng, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xian, D.; Li, X.; Quan, G.; Liu, D.; et al. Membrane-Disruptive Peptides/Peptidomimetics-Based Therapeutics: Promising Systems to Combat Bacteria and Cancer in the Drug-Resistant Era. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2021, 11, 2609–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornesello, A.L.; Borrelli, A.; Buonaguro, L.; Buonaguro, F.M.; Tornesello, M.L. Antimicrobial Peptides as Anticancer Agents: Functional Properties and Biological Activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.L.; da Cunha, N.B.; Costa, F.F. Antimicrobial Peptides, Nanotechnology, and Natural Metabolites as Novel Approaches for Cancer Treatment. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2018, 183, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AMP | Assembly | Biomedical application | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly (lysine) | Dendrimers-based hydrogel | Trauma and intraoperative bleeding | [12] |

| G3KP | OCMC/G3KP hydrogel | Hemostasis, adhesiveness, wound healing, bactericidal effect | [13] |

| DIKVAV | Self-assembled hydrogel | Growth factor delivery | [15] |

| Melittin | Melittin /Chlorin e6 /hyaluronic acid nanoparticles (60 nm in size) | Selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells | [22] |

| Gramicidin D | Self-assembled nanoparticles in water dispersion (150 nm in size) | Microbicidal effect against S. aureus and C. albicans | [23] |

| Gramicidin D and cationic polymer PDDA | Coatings from nanoparticles (self-assembled NPs of Gr D and self-assembled NPs of bilayer fragments/carboxymethylcellulose/PDDA) | Broad spectrum, high performance, synergistic activity against bacteria and fungus | [39] |

| Cyclic lipopeptides from Bacillus megaterium | Aggregates (80-800nm) | Microbicidal/ lytic action against Bacillus cereus | [45,46] |

| Killer FLIP peptide GRKKRRQRRRFFWSLCTA |

Self-assembled aggregates | Selective lysis of cancer cells | [59,60] |

| Folic acid (FA)-modified peptide FA-EEYSV-NH | Fibers | Specific toxicity against cancer cells | [62] |

| Cyclo-HH/anticancer drugs/Zn2+/NO3− | Assemblies | Drug delivery to the brain | [65] |

| Angiopep-2/daunomycin | Conjugates | Drug delivery to the brain | [74] |

| Macrocyclic peptide pAC65 | Immunotherapy against cancer | [75] | |

| Fusogenic peptide pHLIP® /Gr A | pHLIP®/ GrA in liposomes | Acidic pH transfer of Gr A to cancer cells | [89] |

| galactose−Gr A | Galactose conjugated to Gr A N terminus | Targeting galactose−Gr A to asialoglycoprotein in cancer cells | [91] |

| Gr A /doxorubicin | Combination | Synergism against colorectal cancer cells (HT-29) | [92] |

| Gr A / iturin A | Combination | Apoptosis of breast cancer cells | [95] |

| Gr A | Inhibition of pancreatic cancer stem cells proliferation | [97] | |

| Gr A | Alone or in combination with anticancer drugs | Inhibition of the proliferation of acute promyelocytic and chronic myeloid leukemia cell lines in absence of hemolytic effects; downregulation of leukemia oncogenes | [98] |

| AMP | Formulation | Anti-infective or antitumoral uses | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gramicidin D and cationic polymer PDDA | Coatings from gramicidin D nanoparticles and PDDA polymer | Broad spectrum, high performance, synergistic activity against bacteria and fungus | [40] |

| Palmitoylated lipopeptides with 2 lysine residues C16-YKK or C16-WKK | Micelles | Activity against bacteria | [110] |

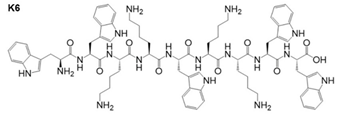

Peptide K6 and similar derivatives |

Micelles | Antibiofilm activity against bacteria | [112] |

| Membrane-active AMPs (e.g., protegrin 1, hBD-3) and antibiotics with intracellular targets (e.g., gentamicin, rifampicin) | Combinations AMPs and antibiotics | Synergy in antibacterial action | [115] |

| Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose/ xyloglucan/ gentamicin | Cross-linked transparent films | Wound healing monitoring/ Antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli | [117] |

| Vancomycin-loaded bone-like hydroxyapatite/poly amino acid | Scaffold | Bone tissue engineering preventing infection | [122] |

| Peptide conjugated to short peptides capable of self-assembling into functionalized β-fibrils | Peptide aggregates at the host receptor for virus binding | Antiviral therapeutics | [128] |

| Intra-lysosomal peptide assembly after cathepsin cleavage of amphiphile peptide NDI-Lyso-RGD | Peptide fibrils inside lysosomes | Cancer cell death due to lysosomal bursting in absence of apoptosis | [132] |

| Cyclic peptide PROTAC |

Degradation of palmitoylacyltransferase | Down regulation of PD-L1 expression in human cervical cancer cells. Enhancement of anti-tumor immunity | [143] |

| Oncolytic peptides BOP7 and BOP9 in pancreatic cancer | Release of damage-associated molecular patterns DAMPS, mediators of ICD | Killing of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro. ICD in vivo | [190] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).