Submitted:

25 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

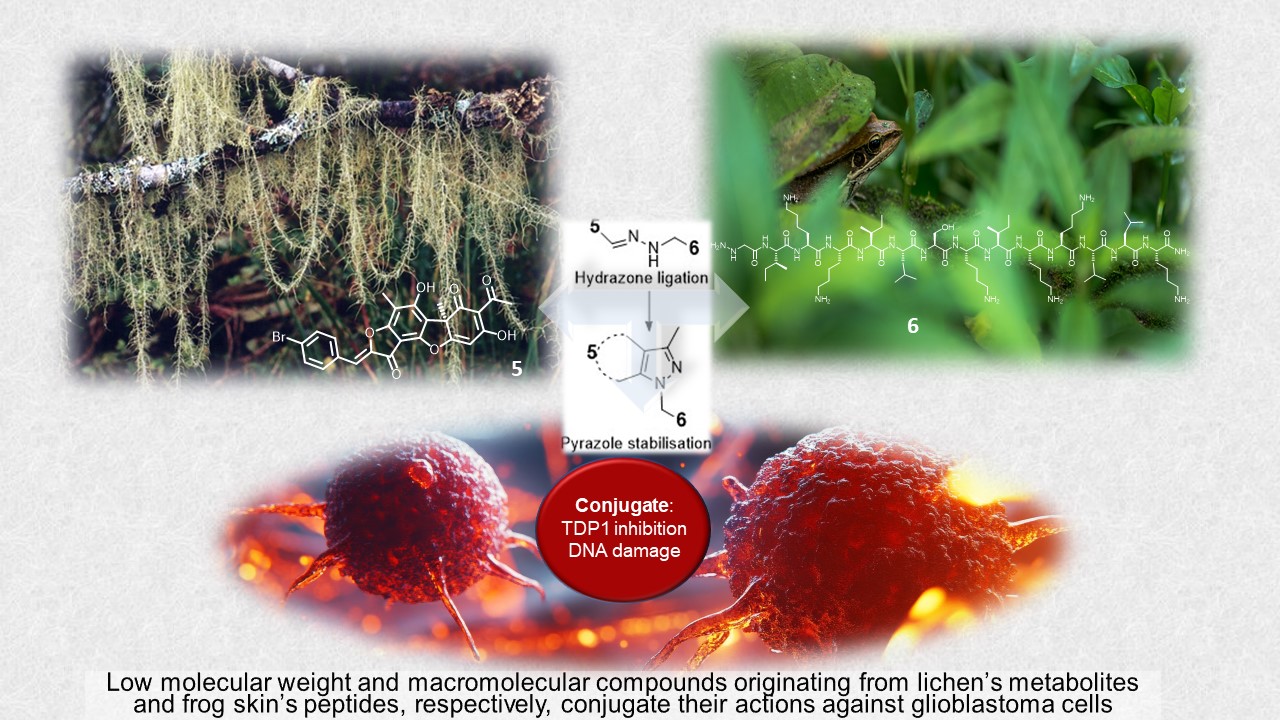

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

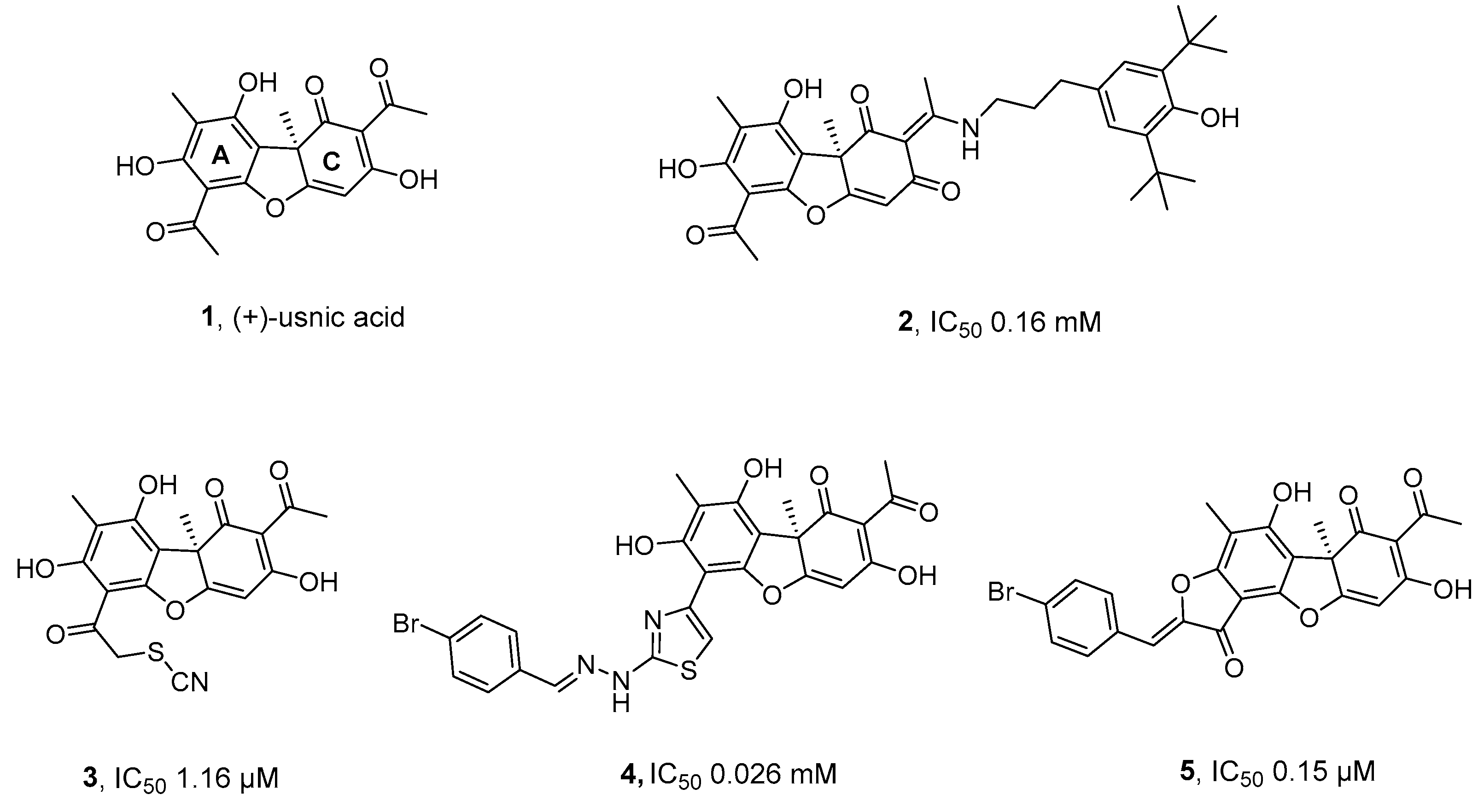

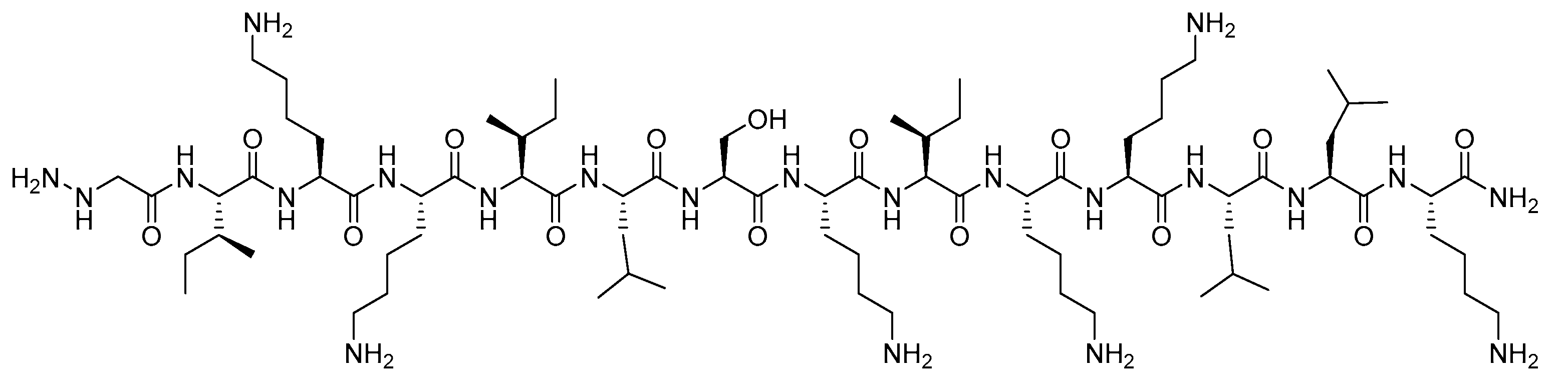

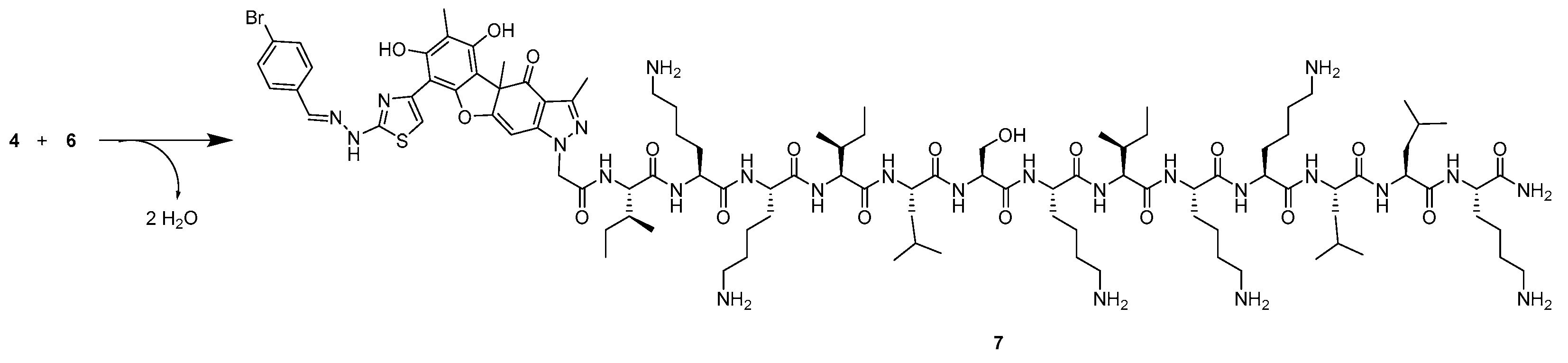

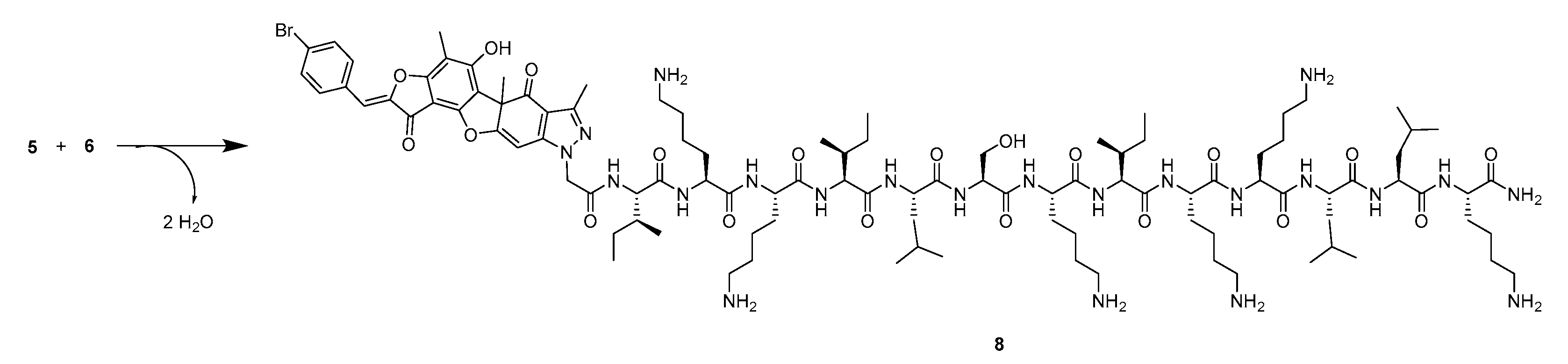

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. TDP1 Inhibition

2.3. Cytotoxicity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. Peptide Synthesis and Purification

4.2. Real-time Detection of TDP1 Activity

4.3. Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity Assay

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Health Topics: Cancer. https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer#tab=tab_1 12/07/2021.

- H Sung, J Ferlay, R L Siegel, M Laversanne, I Soerjomataram, A Jemal and F Bray, Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers and 185 countries, CA Cancer Clin, 2020, 71, 209-249. [CrossRef]

- K O Alfarouk, C-M Stock, S Taylor, M Walsh, A K Muddathir, D Verduzco, A H H Bashir, O Y Mohammed, G O Elhassan, S Harguindey, S J Reshkin, M E Ibrahim and C Rauch, Resistance to cancer chemotherapy: Failure in drug response from ADME to P-gp, Cancer Cell Int, 2015, 15, 71. [CrossRef]

- J-C Marine, S-J Dawson and M. A. Dawson, Non-genetic mechanisms of therapeutic resistance in cancer, Nat Rev Cancer, 2020, 20, 743-756. [CrossRef]

- M Chhabra in Translational Biotechnology: A Journey from laboratory to clinics, (Ed. Y Hasija), Academic Press, United States, 2021, pp. 137-164.

- H X Ngo and S Garneau-Tsodikova, What are the drugs of the future?, Med Chem Commun, 2018, 9, 757-758. [CrossRef]

- L Zhong, Y Li, L Xiong, W Wang, M Wu, T Yuan, W Yang, C Tian, Z Miao, T Wang and S Yang, Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives, Sig Transduct Target Ther, 2021, 6, 201. [CrossRef]

- K S Bhullar, N Orrego Lagarón, E M McGowan, I Parmar, A Jha, B P Hubbard and H P Vasantha Rupasinghe, Kinase-targeted cancer therapies: progress, challenges and future directions, Mol Cancer, 2018, 17, 48. [CrossRef]

- J W Park and J W Han, Targeting epigenetics for cancer therapy, Arch Pharm Res, 2019, 42, 159-170. [CrossRef]

- E Manasanch and R Orlowski, Proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy, Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2017, 14, 417-433. [CrossRef]

- M R Kelley and M L Fishel, DNA Repair Proteins as Molecular Targets for Cancer Therapeutics, Anticancer Agents Med Chem, 2008, 8, 4, 417-425. [CrossRef]

- J Murai, S N Huang, B B Das, T S Dexheimer, S Takeda and Y Pommier, Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 1 (TDP1) Repairs DNA Damage Induced by Topoisomerases I and II and Base Alkylation in Vertebrate Cells, J Biol Chem, 2012, 287, 16, 12848-12857. [CrossRef]

- N I Rechkunova, N A Lebedeva and O I Lavrik, Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 1 is a new player in repair of apurinic/apyrimidinic sites, Russ J Bioorg Chem, 2015, 41, 474-480. [CrossRef]

- G L Beretta, G Cossa, L Gatti, F Zunino and P Perego, Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 targeting for modulation of camptothecin-based treatment, Curr Med Chem, 2010, 17, 15, 1500-1508. [CrossRef]

- E J. Brettrager and R C.A.M. van Waardenburg, Targeting Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I to enhance toxicity of phosphodiester linked DNA-adducts, Cancer Drug Resist, 2019, 2, 4, 1153-1163. [CrossRef]

- T B. Smallwood, Lauren R. H. Krumpe, C D. Payne, V G. Klein, B R. O'Keefe, R J. Clark, C I. Schroeder and K. J. Rosengren, Picking the tyrosine-lock: chemical synthesis of the tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase I inhibitor recifin A and analogues, Chem Sci, 2024, 15, 13227-13233. [CrossRef]

- A L. Zakharenko, O A. Luzina, A A. Chepanova, N S. Dyrkheeva, N F. Salakhutdinov and O I. Lavrik, Natural products and their derivatives as inhibitors of the DNA repair enzyme Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 1, Int J Mol Sci, 2023, 24, 6. [CrossRef]

- A Bermingham, E Price, C Marchand, A Chergui, A Naumova, E L. Whitson, L R. H Krumpe, E I. Goncharova, J R. Evans, T C. McKee, C J. Henrich, Y Pommier and B R. O'Keefe, Identification of natural products that inhibit the catalytic function of human Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase (TDP1), SLAS Discov, 2017, 22, 9, 1093-1105. [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, O A. Luzina, A Zakharenko, D Sokolov, A Filimonov, N Dyrkheeva, A Chepanova, E Ilina, A Ilyina, K Klabenkova, B Chelobanov, D Stetsenko, A Zafar, C Eurtivong, J Reynisson, K P. Volcho, N F. Salakhutdinov and O Lavrik, Synthesis and evaluation of aryliden- and hetarylidenfuranone derivatives of usnic acid as highly potent Tdp1 inhibitors, Bioorg Med Chem, 2018, 26, 15, 4470-4480. [CrossRef]

- A S Filimonov, A A Chepanova, O A Luzina, A L Zakharenko, O D Zakharova, E S Ilina, N S Dyrkheeva, M S Kuprushkin, A V Kolotaev, D S Khachatryan, J Patel, I K H Leung, R Chand, D M Ayine-Tora, J Reynisson, K P Volcho, N F Salakhutdinov and O I Lavrik, New hydrazinothiazole derivatives of usnic acid as potent Tdp1 inhibitors, Molecules, 2019, 20, 24, 3711. [CrossRef]

- A Zakharenko, O Luzina, O Koval, D Nilov, I Gushchina, N Dyrkheeva, V Švedas, N Salakhutdinov and O Lavrik, Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 1 Inhibitors: Usnic acid enamines enhance the cytotoxic effect of camptothecin, J Nat Prod, 2016, 79, 206, 2961-2967. [CrossRef]

- A L Zakharenko, O A Luzina, D N Sokolov, O D Zakharova, M E Rakhmanova, A A Chepanova, N S Dyrkheeva, O I Lavrik and N F Salakhutdinov, Usnic acid derivatives are effective inhibitors of tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1, Russ J Bioorg Chem, 2017, 43, 84-90. [CrossRef]

- A L. Zakharenko, O A. Luzina, K P. Volcho, N F. Salakhutdinov, O I. Lavrik, D N. Sokolov, V I. Kaledin, V P. Nikolin, N A. Popova, J Patel, O D. Zakharova, A A. Chepanova, A Zafar, J Reynisson, E Leung and I K. H. Leung, Novel tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 inhibitors enhance the therapeutic impact of topoteсan on in vivo tumor models, Eur J Med Chem, 2019, 161, 581-593. [CrossRef]

- T E Kornienko, A A Chepanova, A L Zakharenko, A S Filimonov, O A Luzina, N S Dyrkheeva, V P Nikolin, N A Popova, N F Salakhutdinov and O I Lavrik, Enhancement of the antitumor and antimetastatic effect of Topotecan and normalization of blood counts in mice with lewis carcinoma by Tdp1 Inhibitors - New usnic acid derivatives, Int J Mol Sci, 2024, 25, 2. [CrossRef]

- K R Kampen, Membrane proteins: The key players of a cancer cell, J Membrane Biol, 2011, 242, 69-74. [CrossRef]

- D Wua, Y Gao, Y Qi, L Chen, Y Maa and Y Li, Peptide-based cancer therapy: Opportunity and challenge, Cancer Lett, 2014, 351, 1, 13-22. [CrossRef]

- A Reinhardt and I. Neundorf, Design and application of antimicrobial peptide conjugates, Int J Mol Sci, 2016, 17, 701. [CrossRef]

- D Gaspar, A S Veiga and M A R BCastanho, From antimicrobial to anticancer peptides: A review, Front Microbiol, 2013, 4, 294. [CrossRef]

- C Wang, S Dong, L Zhang, Y Zhao, L Huang, X Gong, H Wang and D Shang, Cell surface binding, uptaking and anticancer activity of L-K6, a lysine/leucine-rich peptide, on human breast cancer MCF-7 cells, Sci Rep, 2017, 7, 8293. [CrossRef]

- M Kalmouni, S Al-Hosani and M. Magzoub, Cancer-targeting peptides, Cell Mol Life Sci, 2019, 76, 2171-2183. [CrossRef]

- C Recio, F Maione, A J Iqbal, N Mascolo and V De Feo, The potential therapeutic application of peptides and peptidomimetics in cardiovascular disease, Front Pharmacol, 2017, 7, 526. [CrossRef]

- B M Cooper, J Legre, D H O' Donovan, M Ölwegård Halvarsson and D R Spring, Peptides as a platform for targeted therapeutics for cancer: peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs), Chem Soc Rev, 2021, 3, 50, 1480-1494. [CrossRef]

- W Li, F Separovic, N M O'Brien-Simpson and J D Wade, Chemically modified and conjugated antimicrobial peptides against superbugs, Chem Soc Rev, 2021, 50, 8, 4932-4973. [CrossRef]

- S Prasad Selvaraj and J-Y Chen, Conjugation of antimicrobial peptides to enhance therapeutic efficacy, Eur J Med Chem, 2023, 259, 115680. [CrossRef]

- S F. A. Rizvi, H Zhang and Q Fang, Engineering peptide drug therapeutics through chemical conjugation and implication in clinics, Med Res Rev, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D Bonnet, C Grandjean, P Rousselot-Pailley, P Joly, L Bourel-Bonnet, V Santraine, H Gras-Masse and O Melnyk, Solid-phase functionalization of peptides by an a-Hydrazinoacetyl group, J Org Chem, 2003, 68, 7033-7040. [CrossRef]

- L Guy, J Vidal and A Collet, Design and synthesis of hydrazinopeptides and their evaluation as human eukocyte elastase inhibitors, J Med Chem, 1998, 41, 4833-4843. [CrossRef]

- D N. Sokolov, O A. Luzina and N F. Salakhutdinov, Usnic acid: preparation, structure, properties and chemical transformations, Russ Chem Rev, 2012, 81, 8, 747-768. [CrossRef]

- Luzina, M P. Polovinka, N F. Salakhutdinov and G. A. Tolstikov, Chemical modification of usnic acid: III.* Reaction of (+)-usnic acid with substituted phenylhydrazines, Russ J Org Chem, 2009, 45, 1783-1789. [CrossRef]

- A Zakharenko, T Khomenko, S Zhukova, O Koval, O Zakharova, R Anarbaev, N Lebedeva, D Korchagina, N Komarova, V Vasiliev, J Reynisson, K Volcho, N Salakhutdinov and O Lavrik, Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 inhibitors with a benzopentathiepine moiety, Bioorg Med Chem, 2015, 9, 23, 2044-2052. [CrossRef]

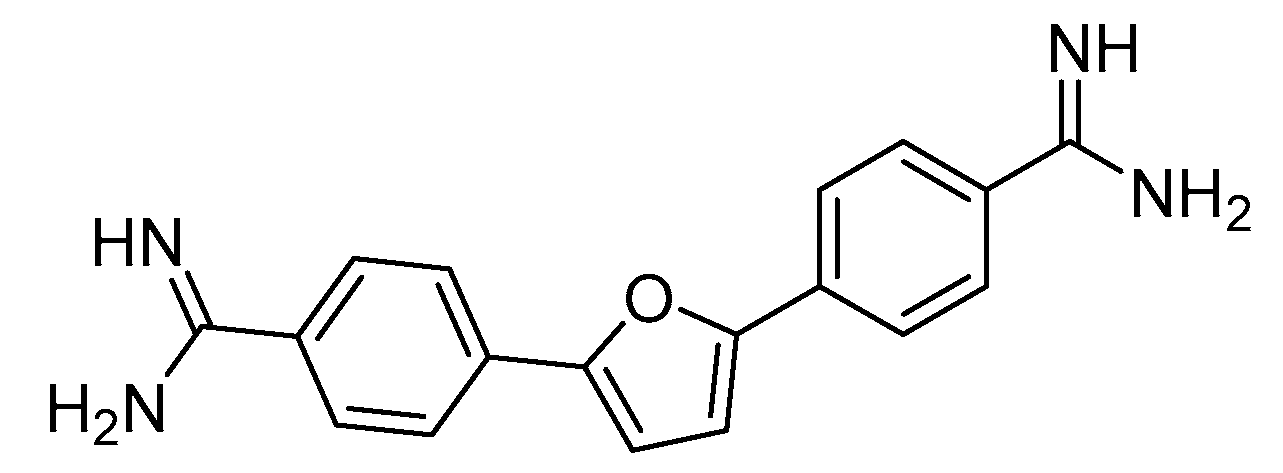

- S Antony, C Marchand, A G Stephen, L Thibaut, K K Agama, R J Fisher and Y. Pommier, Novel high-throughput electrochemiluminescent assay for identification of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase (Tdp1) inhibitors and characterization of furamidine (NSC 305831) as an inhibitor of Tdp1, Nucleic Acids Res, 2007, 13, 35, 4474-4484. [CrossRef]

- J L. Lau and M K. Dunn, Therapeutic peptides: Historical perspectives, current development trends and future directions, Bioorganic Med Chem Lett, 2018, 26, 2700-2707,.

- B M. Cooper, J Iegre, D H. O'Donovan, M O. Halvarsson and D R. Spring, Peptides as a platform for targeted therapeutics for cancer: peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs), Chem Soc Rev, 2021, 50, 1480-1494. [CrossRef]

- W Tang and M L. Becker, “Click” reactions: a versatile toolbox for the synthesis of peptide-conjugates, Chem Soc Rev, 2014, 43, 20, 7013-7039. [CrossRef]

- J B. Matson and S I. Stupp, Drug release from hydrazone-containing peptide amphiphiles, Chem Commun, 2011, 47, 7962-7964. [CrossRef]

- G J. Kelly, A Foltyn-Arfa Kia, F Hassan, S O'Grady, M P. Morgan, B S. Creaven, S McClean, J H. Harmey and M Devocelle, Polymeric prodrug combination to exploit the therapeutic potential of antimicrobial peptides against cancer cells, Org Biomol Chem, 2016, 14, 9278-9286. [CrossRef]

- A Dal Pozzo, M-H Ni, E Esposito, S Dallavalle, L Musso, A Bargiotti, C Pisano, L Vesci, F Bucci, M Castorina, R Foderà, G Giannini, C Aulicino and S Penco, Novel tumor-targeted RGD peptide–camptothecin conjugates: Synthesis and biological evaluation, Bioorg Med Chem, 2010, 18, 64-72. [CrossRef]

- R A. Firestone, D Willner, S J. Hofstead, H D. King, T Kaneko, G R. Braslawsky, R S. Greenfield, P A. Trail, S J. Lasch, A J. Henderson, A M. Casazza, I Hellström and K E. Hellström, Synthesis and antitumour activity of the immunoconjugate BR96-Dox, J Control Release, 1996, 39, 2-3, 251-259. [CrossRef]

- A Saghaeidehkordi, S Chen, S Yang and K Kaur, Evaluation of a keratin 1 targeting peptide-doxorubicin conjugate in a mouse model of triple-negative breast cancer, Pharmaceutics, 2021, 13, 5, 661-675. [CrossRef]

- M Alas, A Saghaeidehkordi and K Kaur, Peptide–drug conjugates with different linkers for cancer therapy, J Med Chem, 2021, 64, 1. [CrossRef]

- E Ziaei, A Saghaeidehkordi, C Dill, I Maslennikov, S Chen and K. Kaur, Targeting triple negative breast cancer cells with novel cytotoxic peptide-doxorubicin conjugates, Bioconjug Chem, 2019, 30, 12. [CrossRef]

- P Hoppenz, S Els-Heindl and A G Beck-Sickinger, Peptide-drug conjugates and their targets in advanced cancer therapies, Front Chem, 2020, 8, 571. [CrossRef]

- L De Rosa, R Di Stasi, A Romanelli and L D D’Andrea, Exploiting protein N-Terminus for site-specific bioconjugation, Molecules, 2021, 26, 12, 3521. [CrossRef]

- S-S Li, M Zhang, J-H Wang, F Yang, B Kang, J-J Xu and H-Y Chen, Monitoring the changes of pH in lysosomes during autophagy and apoptosis by plasmon enhanced raman imaging, Anal Chem, 2019, 91, 13, 8398–8405. [CrossRef]

- J R McCombs and S C Owen, Antibody Drug Conjugates: Design and selection of linker, payload and conjugation chemistry, AAPS J, 2015, 17, 2, 339-351. [CrossRef]

- B C. Atkinson and A R. Thomson, Structured cyclic peptide mimics by chemical ligation, Pept Sci, 2022, 114, 5. [CrossRef]

- M I. Meschaninova, N S. Entelis, E L. Chernolovskaya and A G. Venyaminova, A verstaile solid-phase approach to the synthesis of oligonucleotide conjugates with biodegradeable hydrazone linker, Molecules, 2021, 26, 8, 2119-2134. [CrossRef]

- M Mallig, D Hymel and F Liu, Further Exploration of Hydrazine-Mediated Bioconjugation Chemistries, Org Lett, 2020, 22, 16, 6677-6681. [CrossRef]

- P Liao and C He, Azole reagents enabled ligation of peptide acyl pyrazoles for chemical protein synthesis, Chem Sci, 2024, 15, 7965-7974. [CrossRef]

- H C. Kolb and K B. Sharpless, The growing impact of click chemistry on drug discovery, Drug Discov Today, 2003, 8, 24, 1128-1137. [CrossRef]

- N Dyrkheeva, R Anarbaev, N Lebedeva, M Kuprushkin, A Kuznetsova, N Kuznetsov, N Rechkunova and O Lavrik, Human Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 1 Possesses Transphosphooligonucleotidation Activity With Primary Alcohols, Front Cell Dev Biol, 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

| Compounds | IC50, nM |

|---|---|

| 4 | 26±11 |

| 5 | 150±30 |

| 6 | 1800+600 |

| 7 | 168+23 |

| 8 | 340+34 |

| 9 | 1200±300 |

| Cell Line | Cytotoxic dose1 (µM) | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI50 | 2.8±0.07 | 2.2±0.31 | 39±6.08 | 65±15.29 | 36±1.24 | |

| MCF-7 | GI80 | 4.7±0.21 | 3.9±0.87 | 81±16 | >100 | 72±2.4 |

| GI90 | 5.5±0.41 | 4.7±1.59 | >100 | >100 | >100 | |

| GI50 | 20.5±2.27 | >100 | >100 | 18±0.35 | 16.5±0.35 | |

| SNB19 | GI80 | 61±1.78 | >100 | >100 | 68±3.34 | 56±0.7 |

| GI90 | 83±1.87 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 85±2.32 | |

| GI50 | 10.1±0.67 | 21±2.6 | >100 | 42±3.02 | 38±1.22 | |

| T98G | GI80 | 51±1.08 | >100 | >100 | 82±1.78 | 80±2.86 |

| GI90 | 90±3.94 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | |

| Vero | GI50 | 4,1±1,66 | >100 | 64±13,71 | 33±3,53 | 18±3,18 |

| GI80 | 48±16,76 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | |

| GI90 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).