1. Introduction

The high complexity of atmospheric composition is due to the simultaneous factors such as the mixture of particles which interact in different manner over the time and the space. Aerosol particles are either emitted directly to the atmosphere by anthropogenic and natural sources (primary pollutants) or they are formed in the atmosphere by condensation of low-volatility compounds (secondary pollutants) [

1]. Aerosols radiative, chemical and physical aerosol properties are strongly related to a combination of natural emissions, modification of the natural emissions by human activities, such as land-use change, and anthropogenic emissions from biofuel combustion and industrial processes. Nevertheless, large uncertainties still exist both for many aerosol sources, in terms of emitted fluxes and new particles formation from global to local scale and for their quantitative effect on the meteorology. Atmospheric particles can modify cloud microphysical properties such as droplet number and size and water/ice phase, and thus altering the intensity and spatial distribution of precipitations events [

2]. These effects are associated with modifications in the boundary layer meteorology from local to global scale [

3,

4] , which are certainly relevant both in air quality modeling and in the prediction of future temperatures and precipitation (meteorology). Although the sustained research efforts done, the mechanisms by which the aerosols particles affect the clouds and the substantial rainfall remain still unclear. Nevertheless, this challenging topic (i.e. the impact of aerosols cycling and formation on meteorology and vice versa) relies on robust and consolidated results from literature ([

2,

5,

6,

7,

8]). It is well known that physical and chemical properties of atmospheric particles may influence the meteorology through direct, semi-direct, and indirect effects [

9,

10]. Direct aerosol effect refers to aerosols scattering and absorption of solar radiation. These effects on radiation result in changes in temperature, wind speed, relative humidity, and atmospheric stability, which are named semi-direct effects [

11]. While, the effects of aerosols through clouds are classified as indirect effects [

12], which in turn are sub-classified into the formation of cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) or ice nuclei (IN) [

2].

In this context, we can state that at least the impact of columnar aerosol loading for estimating radiative transport throughout the atmosphere is clear [

13], while there is more uncertainty in quantifying the effects of atmospheric particles on cloudiness and precipitation. An adequate numerical representation of these effects is crucial, this is the major motivation to recommend the migration from offline to online integrating modeling systems. They can guarantee a consistent treatment of processes and allow two-way interactions of physical and chemical components, particularly for air quality (AQ) and numerical weather prediction (NWP) communities [

4]. For cloud properties, having online aerosols is most probably an advantage, while for precipitation the benefits are not yet clear. It is also unclear whether the advantages demonstrated for short-term episodes with extreme aerosol loading are still present in more common situations relevant for daily weather prediction. Idealized model sensitivity studies on isolated clouds show a clear aerosol effect, while in more realistic simulations the atmospheric feedback is more complex, including chains of interactions with many other processes and with compensating effects.

As pointed out by the results achieved by the international initiative on Air Quality Modeling Evaluation (AQMEII [

14]), the indirect effects seem to be very sensitive to the sophistication of the chosen parameterizations and to the details of the implementation. For instance, employing essentially the same theoretical approaches for CCN sometimes very different results are achieved [

14]. In fact, dust particles, which cover approximately 50% of the global load of the natural airborne particles [

15], play a key role in the rainfall formation as they provide a surface for condensation. Previous studies on the aerosols effects on the rainfalls have reported contradicting results, with some indicating that dust enhance rainfall while others report a suppressing effect. Thus, dust can both increase and decrease rainfall by affecting air mass circulation at local scale [

16]. In general, feedback effects seem to have a crucial impact in the vicinity of large emission sources, such as Saharan desert. Western Europe and Mediterranean basin, where intense mesoscale vortices [

17] are often associated with heavy mineral dust transport from Sahara Desert [

18] might be considered like a natural laboratory in which investigate such processes. Remy et al,. [

13] highlighted how important accurate forecasts of the timing of the storm are, since depending on the local time of the dust lifting episodes, the interactions between aerosol and boundary layer meteorology are of a very different nature. Menut et al., [

19] - in their sensitivity experiments carried out to evaluate the impact of the aerosols on the meteorology in southern west Africa - stated that the most important effect of aerosol cloud interactions is found by halving the emissions of mineral dust which results in a decrease of the 2 m temperature by 0.5 K and of the boundary layer height by 25 meters on a monthly average over the Saharan region. The presence of dust aerosols also increases (decreases) the shortwave (longwave) radiation at the surface by 25 W m

−2. Parajuli et al., [

20] pointed out that although the domain-average rainfall change caused by dust appeared small, the effect can be large at different locations and times. Besides, the same authors, by investigating in quantitative manner the direct and indirect dust effect over a ten-years period, found that dust enhanced rainfall for extreme rainfall events but suppress rainfall for normal rainfall events [

20]. Flaounas et al., [

21] in their recent paper argue about the key rule of mineral dust particles mobilization from northern Africa under cyclonic circulation conditions; they point out the current lack of acknowledge about the net effect - ascribable to the huge load of mineral dust particles – on (i) the radiation balance of the atmosphere, and (ii) cloud and precipitation processes during the triggering and the development of severe episodes.

The purpose of this paper is to address the role of Saharan dust in affecting the regional weather system in the Mediterranean basin. The investigation of VAIA thunderstorm episode (29th October 2018) is reported with the aim to shed light on this topic by carrying out three different experiments with two state of the art fully coupled models, namely WRF-CHIMERE and WRF-Chem: (i) the control run, (ii) removing the mineral dust, (iii) replacing the parametrization for cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) and ice-nucleating particle (INP) formation (DeMott et al., 2010 and DeMott et al., 2015).

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Description of Numerical Modeling

Numerical simulations of severe Mediterranean Saharan dust storm were carried out by using two fully coupled models used for this study: WRF-CHIMERE v2020r3 and WRF-Chem v4.2.1 [

22]. The simulations focused on the day of October 29 of 2018, when an intense Saharan dust outbreak occurred over the Mediterranean basin.

Figure 1 depicts the integration domains considered for this study designed for WRF-Chem (left panel) and WRF-CHIMERE (right panel).

2.2. CHIMERE Model Fully Coupled with WRF

In this work, we have used the version 2020r3 of the WRF-CHIMERE model. WRF-CHIMERE is an online access meteorology-chemistry coupled model which allows the simulation of aerosol direct and indirect effects [

23,

24,

25]. In this modeling tool, the mesoscale meteorological model WRF V3.7.1 is coupled with the CHIMERE chemical and transport model [

25,

26] exchanging the meteorological and aerosol fields via the external coupling software OASIS3-MCT [

27] with sub hourly frequency chosen by the user. The models run on the same horizontal grid, but vertical grids are different. WRF feeds CHIMERE with 28 meteorological fields. The direct effect is simulated by using the aerosol optical depth, aerosol single scattering albedo, and asymmetry parameter calculated starting from aerosol mass distribution size predicted by CHIMERE. These optical properties are diagnosed with Mie theory under an external mixing assumption and are used in WRF to force the Rapid Radiative Transfer Model for GCMs (RRTMG) scheme [

28] in both visible and infrared bands. Further details are provided in [

23]. Aerosol indirect effects are simulated as described by Tuccella et al. (2019) [

24] via the aerosol-aware cloud microphysics scheme developed by Thompson and Eidhammer (2014) [

29]. This scheme considers the aerosol activation as cloud droplet and ice nucleation starting from an aerosol climatology assumed to be log-normally distributed. In WRF-CHIMERE, this approach has been replaced with the aerosol fields predicted by CHIMERE. Aerosol size distribution and bulk hygroscopicity diagnosed from aerosol mass calculated by CHIMERE following a sectional approach [

25,

26] are used in WRF to calculate the aerosol activation rate as cloud droplet according to Abdul-Razzak (2002) [

30], with a maximum supersaturation determined from a Gaussian spectrum of updraft velocity according to Ghan et al. (1997) [

31]. Following Thompson and Eidhammer (2014) [

29], aerosol activation occurs in the cloud when the number of activated aerosols is larger than the existing droplet mixing ratio. Heterogeneous and homogeneous ice nucleation are parameterized following Thompson and Eidhammer (2014) [

29], but the climatology of ice nucleating particles and deliquesced aerosol are replaced with the fields predicted by CHIMERE. In WRF-CHIMERE, dust particles with diameter larger than 0.5 µm are considered as ice nuclei for heterogeneous ice nucleation. The number of dust particles which nucleate as ice particles is determined with the parameterization of De Mott et al. (2015) [

32]. Homogeneous nucleation of deliquesced aerosols is parameterized according to Koop et al. (2000) [

33]. In WRF-CHIMERE a mixture of sea salt, inorganic and secondary organic aerosols with diameter larger than 0.1 µm is considered as deliquesced aerosols suit-able for ice homogeneous nucleation.

The horizontal domain designed for WRF–CHIMERE runs is composed of a parent domain which covers Europe with horizontal resolution of 15 km, and the nested one which covers the Italian peninsula with horizontal grid spacing of 3 km, reported in

Figure 1 (right panel). The simulation started on October 27, 2018 (00:00 UTC) and ended on October 31, 2018 (00:00 UTC). WRF vertical grid is composed of 33 levels extending up to 50 hPa, CHIMERE is set with 28 vertical meshes up to 150 hPa. The exchange frequency between the models is 5 minutes. The parameterizations adopted for WRF-CHIMERE are the same used in Tuccella et al. (2019) [

24]. This setup has been successfully implemented in different previous works (e.g., [

8,

19]). As described above, the Thompson and Eidhammer (2014) [

29] and RRTMG [

28] schemes are adopted for cloud microphysics and radiation. Planetary boundary layer is parameterized with the YSU scheme [

34], Noah is used as land surface model [

35], and convective parameterization adopted is the scheme of Grell and Freitas (2014) [

36]. No cumulus parameterization is used in the inner domain. The gas-phase chemical model adopted in CHIMERE is the MELCHIOR2 scheme [

37], photolytic rates are calculated with the Fast-JX model according to Wild et al. (2000) [

38]. Aerosol evolution is parameterized with a sectional approach ([

25,

26,

39]). The aerosol species predicted by CHIMERE are sulfate (SO4), nitrate (NO3), ammonium (NH4), black carbon (BC), primary unspeciated aerosol, primary organic matter (POM), secondary organic aerosols (SOA), aerosol water, mineral dust and sea salt. Anthropogenic emissions are from EMEP inventory, biogenic emissions are calculated with the model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature (MEGAN) [

40], soil dust emission flux is parameterized according to the description provided in Menut et al. (2015) [

41], and sea salt emissions follow Monahan (1986) [

42].

2.3. WRF-Chem Fully Coupled Online Model

WRF-Chem model version 4.2.1 has been utilized in a numerical domain covering the upper Sahara Desert and the central Mediterranean.

Figure 1 (left panel) reports the WRF-Chem integration domain with 600×600 points and a horizontal grid spacing of 5 km. As the WRF-CHIMERE runs, the simulation started on October 27 and ended on October 31, 2018 (00:00 UTC). Boundary and initial conditions are at 1-degree resolution and provided from NCAR/NCEP Final Analysis from Global Forecast System (FNL from GFS). Basically, the meteorological model WRF used the same physical set of parameterizations. Based on the WRF setup recommended by Rizza et al. (2020) [

43], the following parameterizations are utilized: the Mellor–Yamada–Janjic Scheme (MYJ) parameterization is used to describe the planetary boundary layer (bl_pbl_physics = 2), and surface layer (sf_sfclay_physics = 2) Eta similarity scheme. The Noah-MP Land Surface Model (sf_surface_physics = 4) is chosen to represent the land surface processes [

44]. The Four-dimensional data assimilation (FDDA) schemes based on the Analysis Nudging (grid_fdda = 1) as described by Stauffer and Seaman (1994) [

45] is utilized to account for the meteorological large-scale forcing on the Mediterranean basin [

43]. The radiative schemes are parameterized using the Rapid Radiative Transfer Model [

28] for both short-wave (ra_sw_physics = 4) and long-wave (ra_lw_physics = 4) and coupled with the Goddard Chemistry Aerosol Radiation and Transport (GOCART) model [

46] by the variable “aer rad feedback” defined in the namelist.input chem-section. The coupling strategy between the aerosol field forecast from the GOCART model (chem_opt = 300) and the microphysics parameterization is implemented here following a recent methodology formulated by Su and Fung (2018) [

47]. In this context, the updated Thompson microphysics scheme (mp_physics = 28), that is a bulk two-moment aerosol-aware microphysics scheme that considers the mixing ratios and number concentrations for the following five water species: cloud water, cloud ice, snow, rain, and a mixed hail-graupel class [

29], is coupled with the GOCART aerosol model enabling WRF-Chem to online simulate the effect of dust aerosol in the ice nucleation processes during simulations [

47]. In particular, the updated Thompson–Eidhammer scheme in its default version incorporates the activation of aerosols serving as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) and ice nuclei (IN), and therefore it explicitly predicts the number concentrations of CCN (NWFA - Number Water Friendly Aerosols) and IN (NIFA - Number Ice Friendly Aerosols), as well as the number concentrations of cloud droplets and ice crystals. In the coupling proposed here, the bulk number concentration of ice-friendly aerosol from the GOCART aerosol model is passed into the DeMott et al. (2015) [

32] ice nucleation scheme for the calculation of the number concentration of ice nucleating particles.

Where P(i, j, k) is the ice crystal number per unit produced by the ice nucleation induced by ice-friendly aerosols, with α = 0, β = 1.25, γ = 0.46, δ = -11.6, and cf = 3. GNIFA (Gocart Number Ice Friendly Aerosol) represents an additional coupling variable that should be defined in the registry.chem WRF configuration file and defined in the code as the ratio between the concentration and the total mass of dust aerosols:

In eq. 2 n = 1,5 is the index of the five aerosol bins defined in the GOCART scheme, described below. The final coupling step consists in passing out the tendency of aerosol number concentration for wet removal calculation that represents the tendency term for bulk aerosol number concentration. The WRF-Chem setup related to the aerosols concerns the hybrid bulk/sectional GOCART model. This may be utilized by putting the namelist variable chem_opt = 300. It consists of seven bulk aerosol species – organic carbon (OC1, OC2), black carbon (BC1, BC2), other GOCART primary species (PM2.5, PM10), and sulfate (only secondary aerosol species). The current version of the AFWA dust emission scheme (dust_opt = 3) implemented in WRF-Chem [

48] considers five dust size bins ranging between 200 nm and 20 µm. A detailed description of the AFWA dust emission scheme is already provided by the recent works of LeGrand et al. (2019) [

48], Ukhov et al. (2020) [

49], and Rizza et al. (2021) [

50]. It is important to point out that in this kind of parameterization, the dust emission is controlled by the saltation of larger particles (0 - 100 µm) that are activated by wind shear at the surface. This leads to the emission and entrainment in the air of smaller particles (0 - 10 µm) by saltation bombardment, the resulting vertical bulk dust flux is calculated as:

with

Where G is the total streamwise horizontal saltation flux [

48], β is the sandblasting mass efficiency calculated considering only the soil clay fraction and is the exponential tuning constant for erodibility. Once the total bulk emission (Fbulk) is established, size-resolved dust emission fluxes (g cm² s⁻¹) are obtained according to the five dust size bins distribution described above.

3. Observations

3.1. Modis Dataset

The MODerate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS; Salomonson et al., 1989) instrument has flown on board the Aqua spacecraft since May 2002. It has 36 wavelength bands covering the visible and the infrared spectrum and high spatial resolution. Aqua, whose data are used here, overpasses the Equator at 13:30 LST. The characterization of aerosols is the core of the MODIS mission [

51] and the Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) is still the most important aerosol physical parameter derived from space. Two different approaches are currently used to retrieve the AOD from MODIS data. These are indicated as “Dark Target” [

51] and “Deep Blue” [

52]. The algorithm at the basis of the DT approach is further differentiated when applied over ocean [

53] or land [

3]. On the other side, the DB approach was developed to be applied over bright surfaces (deserts, snow, sun glint) to complement the DT retrievals. The most recent collection (C006) of MODIS AOD data provides a single AOD product combining both the DT and the DB AOD retrievals (here we use the MODIS daily product MYD08 D3 v6;

https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/dataprod/mod08.php).

3.2. GMP

The Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Microwave Imager (GMI) instrument is a multi-channel, conical-scanning, microwave radiometer consisting of thirteen microwave channels ranging in frequency from 10 GHz to 183 GHz. The GPM Microwave Imager (GMI) with its 885 Km swath provides a broad view of cyclones and other storm systems. The data from GMI is used as a reference standard for an international network of partner precipitation-measuring satellites known as the GPM Constellation. The data from the GPM Core Observatory and these partner satellites are unified into a single global precipitation dataset called IMERG (Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for the Global Precipitation Measurement), which is updated every three hours (

https://gpm.nasa.gov/missions/GPM).

3.3. VIIRS

The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite VIIRS is onboard the joint NASA/NOAA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) and NOAA-20 satellites collecting visible and infrared imagery. VIIRS extends observational data collected by analogous sensors like MODIS and NOAA’s Advanced Very High-Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR). VIIRS specialized algorithms are designed to warrant continuity between MODIS and VIIRS data products to facilitate long-term climate data records.

3.4. SEVIRI

SEVIRI is a scanning radiometer that provides image data in four Visible and Near-InfraRed (VNIR) channels (0.4 – 1.6 µm) and eight InfraRed (IR) channels (3.9 – 13.4 µm). The principal feature of this sensor is its continuous imaging of the Earth in 12 spectral channels with a baseline recurrence sequence of 15 min. The imaging sampling distance is 3 km at the sub-satellite point for standard channels, and down to 1 km for the High Resolution Visible (HRV) channels.

3.5. GRISO

GRISO (Spatial Interpolation Generator from Rainfall Observations) is a software tool designed to perform spatial interpolation of rainfall data collected from weather stations or similar observational networks. By utilizing various interpolation techniques (e.g., kriging, inverse distance weighting, or spline methods), GRISO generates continuous spatial rainfall distribution maps from discrete data points. It is commonly used in hydrology, meteorology, and environmental management to analyze rainfall patterns, assess water resource availability, and support decision-making in flood forecasting and agricultural planning.

4. Synoptic Description by Modeling and Satellite Data

As reported in the recent literature between 26 and 30 October 2018, a Mediterranean extreme event took place in its western sector. The authors pointed out the presence of an Atmospheric River developed within a typical autumn synoptic circulation, generally associated with heavy rain conditions over the western Mediterranean Sea basin. In particular, such a Mediterranean storm—called “Vaia”—was characterized by explosive cyclogenesis, storm surge, and extremely intense wind gusts on the western Mediterranean basin and the Northern Sahara Desert. As depicted in

Figure 2, taken by Davolio et al., 2020, an atmospheric river was detected.

It was about 3000 km long and confined in the lower troposphere, below 3000 m all along its path and it reached its maximum intensity over the Mediterranean area. Associated with such synoptic circulation, on 29th October 2018, a huge Saharan dust intrusion over the Italian peninsula was observed from the MODIS sensor onboard Aqua Spacecraft, which passed over Sardinia at 12:40 UTC on October 29 and over Albania at 11:40 UTC on October 30.

Figure 3.

(a) AOD at 550 nm from Modis Aqua for October 29; (b) AOD at 550 nm from Modis Aqua for October 30.

Figure 3.

(a) AOD at 550 nm from Modis Aqua for October 29; (b) AOD at 550 nm from Modis Aqua for October 30.

5. Modeling Results

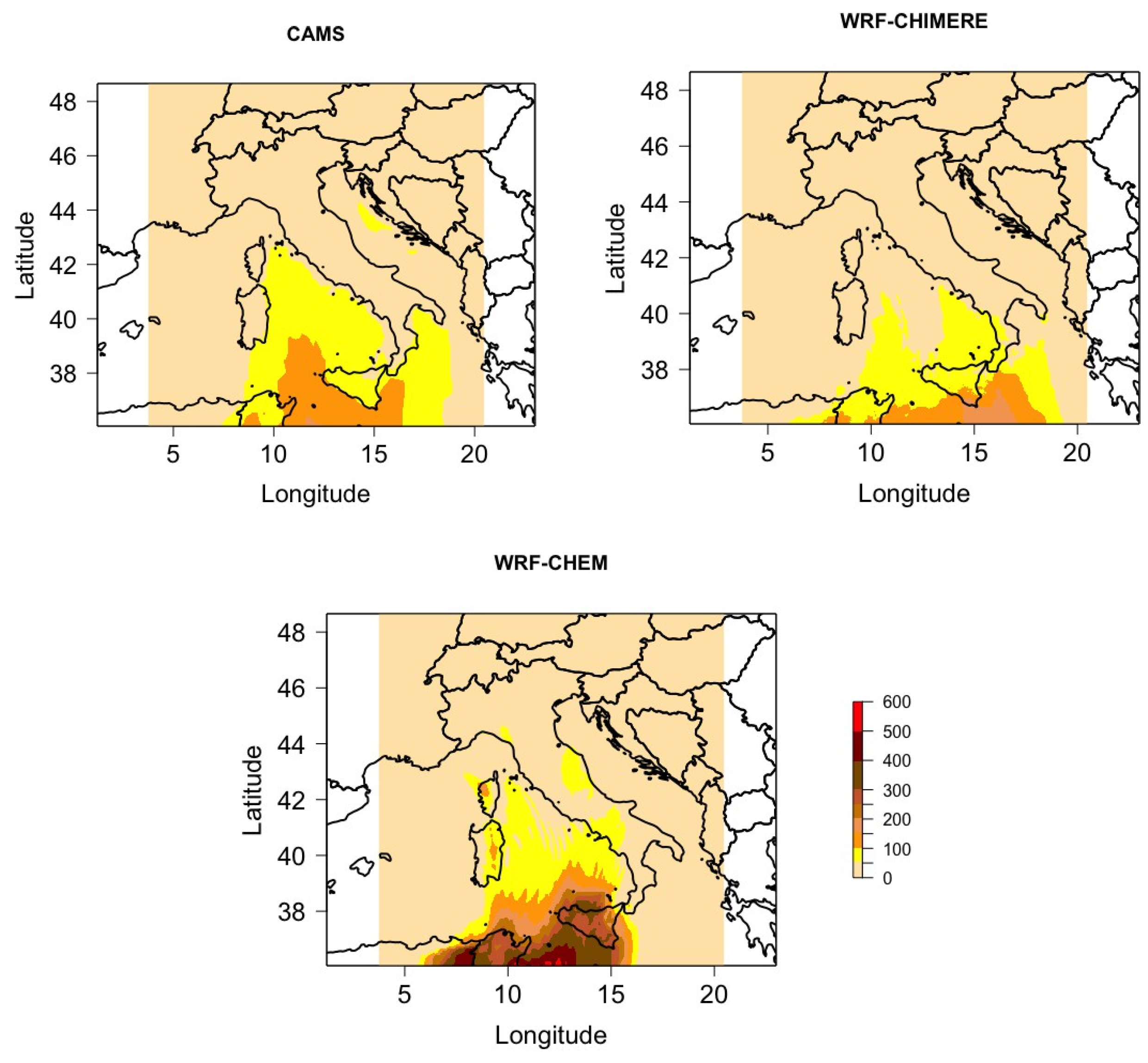

Numerical simulations of the event that occurred on 29th October 2018 were performed with WRF/CHIMERE and WRF/Chem models. Firstly, the outputs are first compared with Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) reanalysis, which are considered as a benchmark, since the validated reanalysis are data-assimilated fields of air pollutant concentrations based on observation data rigorously validated according to the air quality reporting principles set in EU Decision 2011/850/EU on reciprocal exchange of information and reporting on ambient air quality. The comparison of PM10 concentrations at ground level is depicted in

Figure 4.

Basically, the spatial patterns and timing of high PM10 levels are well reproduced by our simulations, even if WRF-CHEM largely overestimates the concentrations calculated at ground level. It is worth noticing that the comparison is done remapping CAMS (i.e., 10 km) and WRF/Chem (i.e., 5 km) over the highest resolution grid of WRF-CHIMERE (i.e., 3 km). The discrepancies found with the considered benchmark might be due to (i) different starting integration domains and/or (ii) different dust emission schemes, which are basically a threshold process that critically depends on the estimation of the 10-m wind speed. Nevertheless, non-redundant model settings are likely useful to quantify the uncertainties associated with each numerical estimation. Secondly, simulated 24-hours accumulated precipitation for October 29, 2018, was compared with gridded observations elaborated using the Random Generator of Spatial Interpolation from uncertain Observations (GRISO). We performed such comparison including the different WRF-CHIMERE runs we did as report in

Table 1.

Figure 5.

Comparison of accumulated daily precipitation for October 29, 2018, over Italian peninsula between observations (upper panel) and the WRF-CHIMERE and WRF-CHEM simulations performed by using different settings: WRF-CHIMERE off-line, on-line, on-line no dust, and WRF/Chem on line (as reported in figure labels).

Figure 5.

Comparison of accumulated daily precipitation for October 29, 2018, over Italian peninsula between observations (upper panel) and the WRF-CHIMERE and WRF-CHEM simulations performed by using different settings: WRF-CHIMERE off-line, on-line, on-line no dust, and WRF/Chem on line (as reported in figure labels).

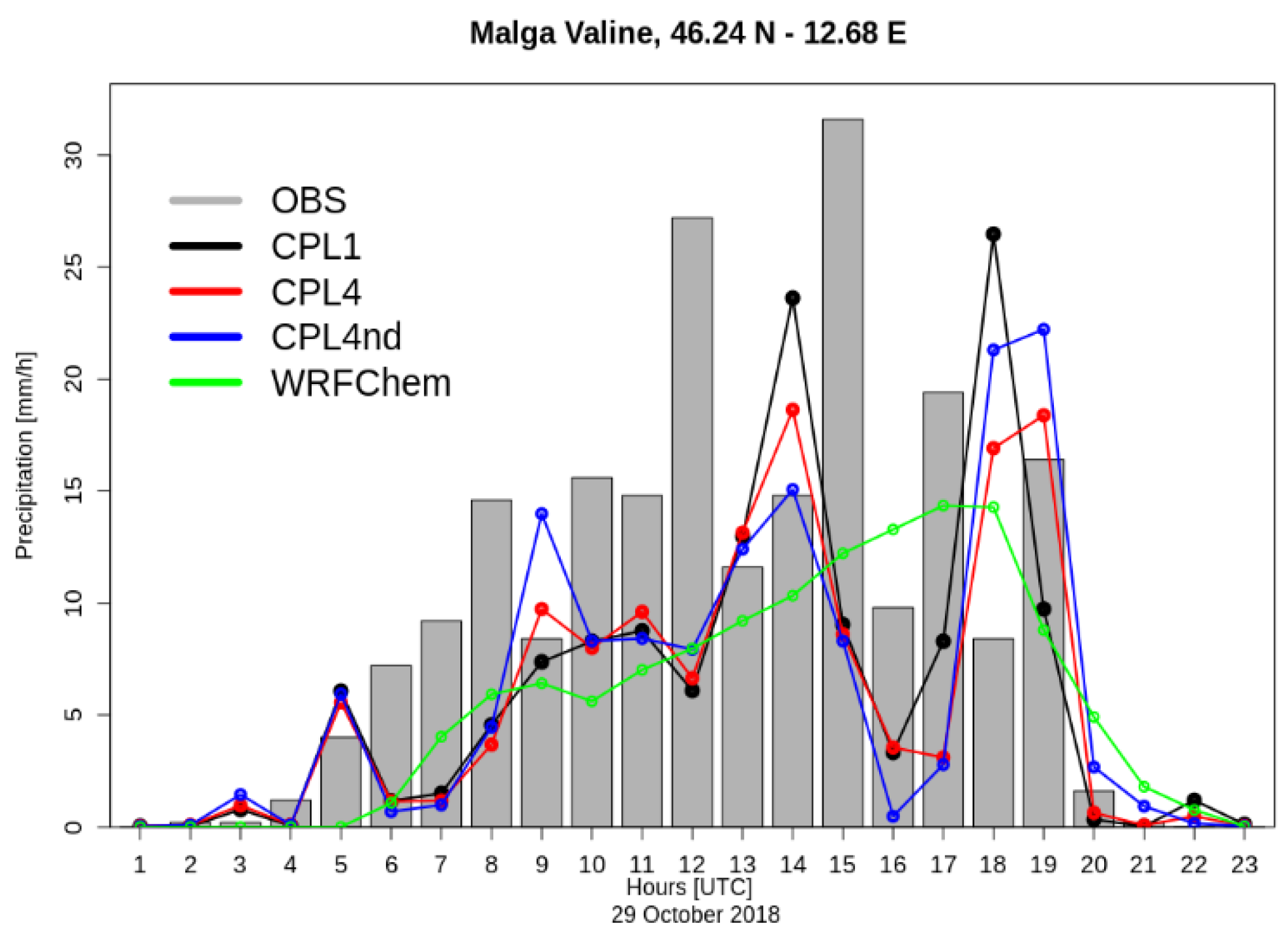

The comparison between observations and numerical results shows that the main characteristics of the storm are well simulated by both models, even if WRF-CHEM underestimates the accumulated rain over the Apuane Alps, which can be considered as the first orographic barrier of AR. On the other hand, WRF-CHIMERE overestimates the precipitation in the western part of the Po basin, where the observation clearly shows a sharp decrease compared with both alpine areas of Liguria on the south side and Lombardy and Piedmont regions on the north side. Besides, we analyzed the accumulated hourly precipitation at Malga Valine (

Figure 6), which has been chosen as representative of the pre-alpine region, where extreme accumulated precipitation was recorded.

At this specific location, the timing seems captured by models: the start of precipitation after a few hours’ interval without precipitation in the night between October 28th and 29th is well reproduced. Nevertheless, both models fail in simulating the extremely high values observed between 12 UTC and 15 UTC. In addition, WRF-CHIMERE overestimates the precipitation at the ending of the event, between 17 UTC and 21 UTC. WRF-CHEM better reproduces the daily behavior precipitation, while WRF-CHIMERE calculates a short precipitation break in the afternoon, which is not observed by the weather station. Overall, the day we considered, the models underestimate the 24-h accumulated rain. The weather station of Malga Valine measured 216 mm day

−1, while the models calculated 140 mm day

−1 by WRF-CHIMERE in offline mode, 130 mm day

−1 in online mode, and 138 mm day

−1 in online mode without dust. WRF/Chem predicts 128 mm day

−1 for 29 October. The models underestimation ranges between 35% and 40%. By focusing on the WRF-CHIMERE runs compared with measurements, we did not find linearity in terms of hourly bias among the different sensitivities. The authors argue about the role of aerosols in the precipitation process, which is still unclear, due to the complexity of indirect effects calculation in online models. In

Section 5.1, we report a few preliminary results which aim to shed light on these interesting aspects.

5.1. WRF-CHIMERE Sensitivity Tests

In order to determine the effects of dust in a model we consider as baseline simulation the on-line WRF-CHIMERE run performed by including all aerosols (dust, sea salt, sulphate, organic, and black carbon). This baseline simulation well reproduces the real-world scenario for October 29 of 2018. The results of this run were compared with no-dust simulation (in

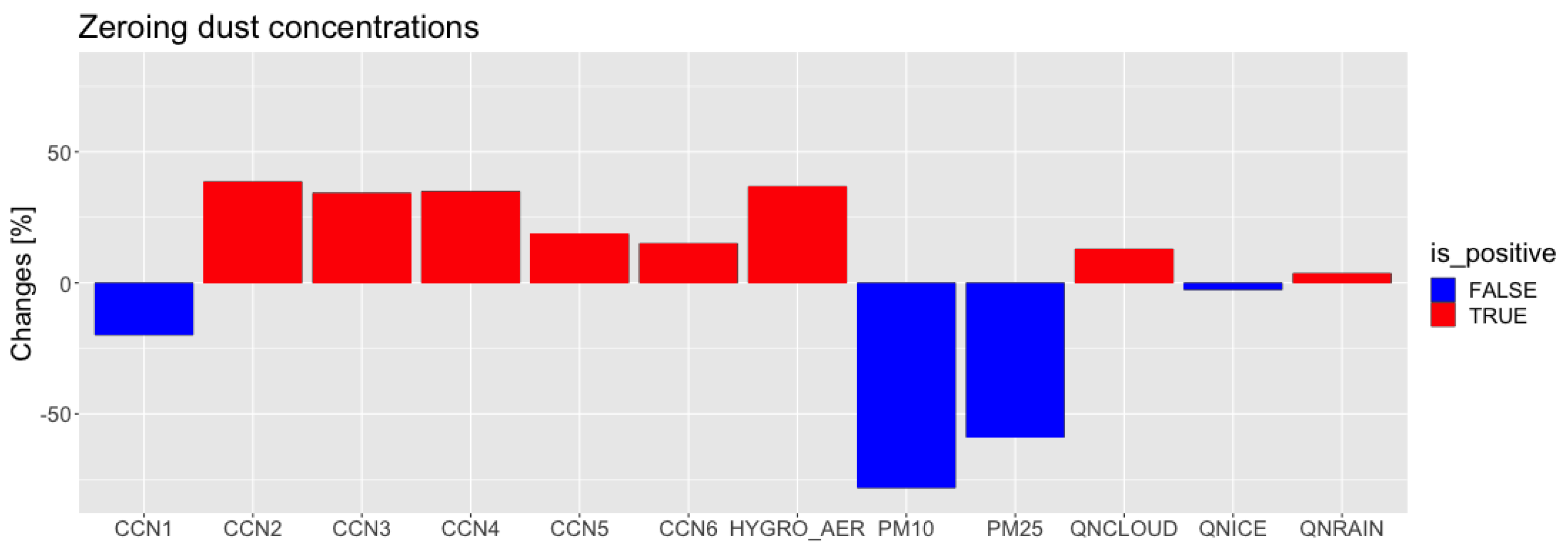

Section 5 named CLP4nd) in which we assigned zero values to dust concentrations. Both of the aforementioned simulations include aerosol-radiation, aerosol-cloud, and microphysical interaction, therefore they represent the total effect of the aerosols, direct and indirect. Thus, we analyze the differences we found for a few key parameters, such as Cloud Condensation Nuclei for different supersaturation thresholds (0.02%, 0.04%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.5% and 1%) and the aerosol hygroscopicity, liquid droplets and ice nuclei number.

Figure 7 reports the percentage variation resulted by zeroing dust concentrations in WRF-CHIMERE on-line runs.

As expected, zeroing dust concentrations a significant PM10 and PM2.5 decrease (i.e., 78% and 59%, respectively) was found as average mass concentration overall 3D integration domain. Acting the aerosols as CCN we can expect that lower PM concentrations in the atmosphere would result in lower number of CCN. Surprisingly, except for CCN activated for lower supersaturation percentage of 0.02%, the CCN volume concentration increase in the no-dust run. The authors argue about the changes of the aerosols hygroscopicity, which increases of about 40% by removing dust particles from the atmosphere. In CHIMERE model mean hygroscopicity parameter calculation is based on the volumetric average of hygroscopicity of the single model species, and dust is treated as hydrophobic specie (i.e., dust hygroscopicity is 0.03, the highest hygroscopicity of sea salt is 1.16, the lowest hygroscopicity of black carbon is 10−6).

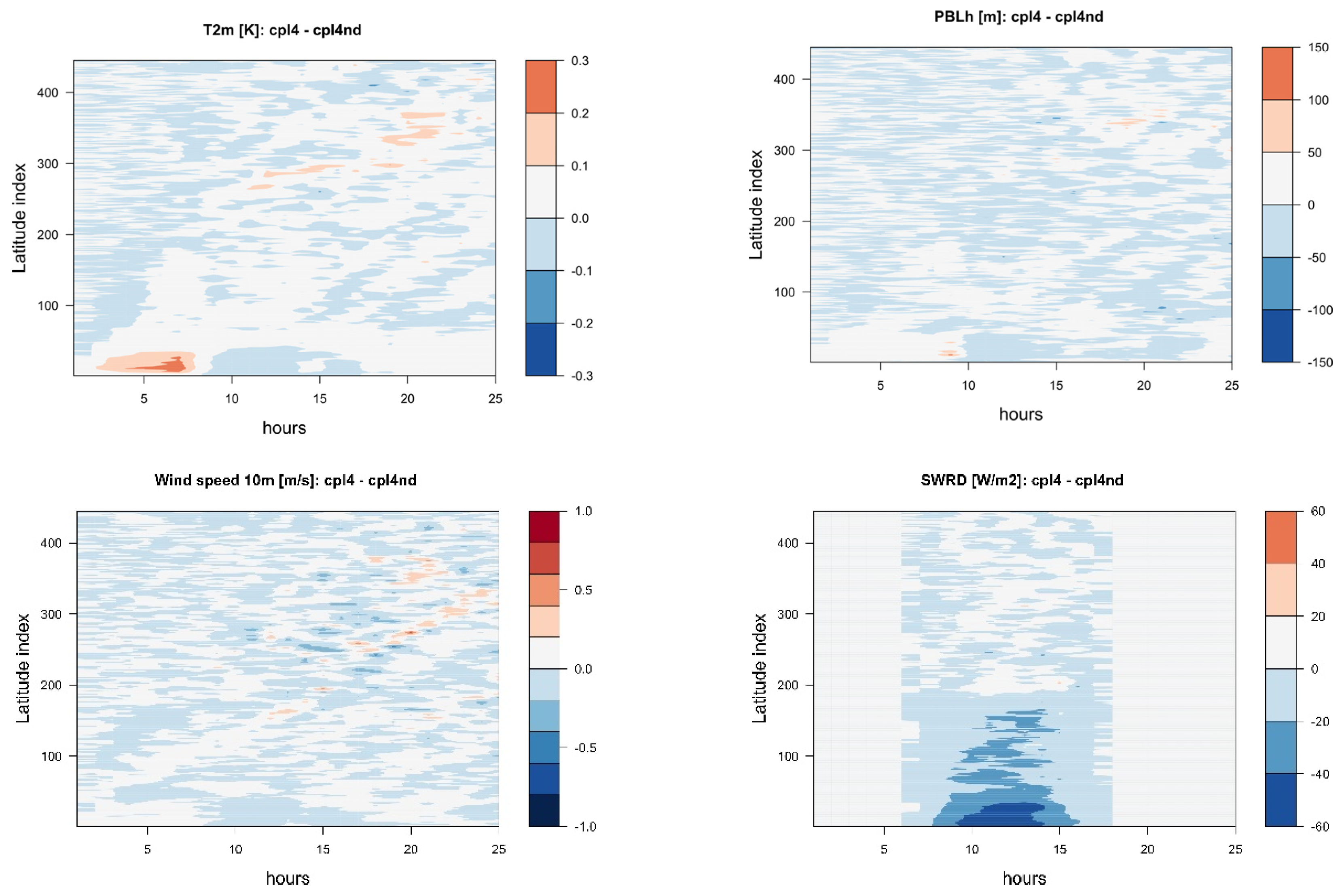

Basically, the effects of aerosols or dust particles on rainfall are governed by multiple microphysical, dynamic and radiative interactions, which can suppress, enhance, or cause no net effect on rainfall depending on the topography and - more in general - on the case study. In addition, the differences on radiation by the scattering and albedo effects of the dust particles themselves were found and as consequence significant variation on surface temperature, planetary boundary layer (PBL) height, wind speed and shortwave radiation.

Figure 8 reports the Hovmöller diagrams for the mentioned parameters.

Figure 8 pointed out the net effect of mineral dust on spatial distribution of the above-mentioned variables: the dust load presence results in shifting of spatial patterns of T2m and wind speed, as well as of vertical motions associated with the calculation of PBL; the shortwave radiation reaching the surface is - as expected, due to higher atmosphere transparency - higher in no-dust conditions throughout the latitude of entire integration domain.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the influence of desert dust on the spatial and temporal variations of precipitation, based on multi-model simulations. The application of both fully coupled and off-line configurations, through WRF-CHIMERE and WRF-Chem, allowed for an examination of the role of dust in cloud microphysics, specifically in the formation and removal of ice nuclei (IN) and cloud condensation nuclei (CCN). The findings reveal that while both models effectively simulate the spatial patterns and timing of high PM10 levels associated with desert dust transport, discrepancies exist, particularly with WRF-Chem overestimating ground-level concentrations. These differences likely arise from variations in integration domains and dust emission schemes, highlighting the necessity of carefully tuning model settings to mitigate uncertainties in numerical estimations.

A key outcome of this study is the evaluation of accumulated precipitation during the VAIA storm (October 29, 2018). While both WRF-CHIMERE and WRF-Chem capture essential storm characteristics, they exhibit significant biases in specific regions, underestimating total accumulated rainfall by approximately 35-40% compared to observations. This underestimation points out the inherent complexity of accurately modeling precipitation events, especially in regions characterized by complex orography.

The sensitivity analyses conducted with WRF-CHIMERE, where dust concentrations were removed, demonstrated expected reductions in PM10 and PM2.5 levels but also revealed an unexpected increase in CCN volume concentrations under certain conditions. This finding suggests that local variations in aerosol concentrations can induce significant changes in precipitation and temperature. However, these effects did not translate into notable total changes in precipitation when averaged over the entire integration domain, implying a potentially weak overall relationship between dust transport and precipitation. This warrants further investigation to delineate the precise mechanisms driving aerosol-cloud-precipitation interactions, as the microphysical and radiative effects of aerosols remain highly context-dependent.

The results of this study underpin the complexity of aerosol-precipitation interactions, which involve multiple competing processes that may lead to different outcomes based on regional and meteorological contexts. The interplay between aerosols and precipitation is not a straightforward cause-effect relationship but rather a dynamic process influenced by a variety of factors including cloud dynamics, thermodynamics, and atmospheric circulation patterns. Consequently, this experiment highlights the necessity for continued improvements in aerosol modeling within coupled meteorological frameworks.

Future research should focus on refining dust emission schemes, enhancing cloud microphysics parameterizations, and conducting additional case studies to improve predictive capabilities of numerical weather models. In particular, further investigation into the thresholds at which aerosols significantly impact/trigger precipitation processes could contribute to a more nuanced understanding of these interactions.

Author Contributions

The initial concept and paper structure were developed by TCL and UR. TCL and MM executed all model simulations required for the study. UR processed the satellite dataset, enabling model comparisons for the region of interest. TCL analyzed and compared model predictions with observational datasets. PT provided essential technical support for the numerical simulations on the HPC infrastructure and authored the WRF-CHIMERE model description. All authors contributed to the writing and review of the manuscript. TCL prepared the final version of the paper for submission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lin Su of Sun Yat-Sen University (SYSU) School of Atmospheric Sciences, Guangzhou (China) for sharing the modification of the WRF-Chem model.

Conflicts of Interest

None

References

- Myhre, G.; Myhre, C.; Samset, B.; Storelvmo, T. Aerosols and their relation to global climate and climate sensitivity. Nature Education Knowledge 2013, 4, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Andreae, M.; Rosenfeld, D. Aerosol–cloud–precipitation interactions. Part 1. The nature and sources of cloud-active aerosols. Earth-Science Rev. 2008, 89, 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, H.; Horowitz, L.W.; Schwarzkopf, M.D.; Ming, Y.; Golaz, J.; Naik, V.; Ramaswamy, V. The roles of aerosol direct and indirect effects in past and future climate change. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 4521–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklanov, A.; Brunner, D.; Carmichael, G.; Flemming, J.; Freitas, S.; Gauss, M.; Hov, Ø.; Mathur, R.; Schlu, K.H.; Seigneur, C.; et al. , Key issues for seamless integrated chemistry–meteorology modeling. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2017, 98, 2285–2292. [Google Scholar]

- Raes, F.; Van Dingenen, R.; Vignati, E.; Wilson, J.; Putaud, J.-P.; Seinfeld, J.H.; Adams, P. Formation and cycling of aerosols in the global troposphere. Atmospheric Environ. 2000, 34, 4215–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.Z. Global direct radiative forcing due to multicomponent anthropogenic and natural aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2001, 106, 1551–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.; Andreae, M.O.; Asmi, A.; Chin, M.; de Leeuw, G.; Donovan, D.P.; Kahn, R.; Kinne, S.; Kivekäs, N.; Kulmala, M.; et al. Global observations of aerosol-cloud-precipitation-climate interactions. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 750–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroubaix, A.; Menut, L.; Flamant, C.; Knippertz, P.; Fink, A.H.; Batenburg, A.; Brito, J.; Denjean, C.; Dione, C.; Dupuy, R.; et al. Sensitivity of low-level clouds and precipitation to anthropogenic aerosol emission in southern West Africa: a DACCIWA case study. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2022, 22, 3251–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkel, R.; Werhahn, J.; Hansen, A.B.; McKeen, S.; Peckham, S.; Grell, G.; Suppan, P. Effect of aerosol-radiation feedback on regional air quality – A case study with WRF/Chem. Atmospheric Environ. 2012, 53, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, Z.; Steiner, A.; Zakey, A.S.; Shalaby, A.; Wahab, M.M.A. ; University of Michigan; Cairo University An exploration of the aerosol indirect effects in East Asia using a regional climate model. Atmos. 2020, 33, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Easter, R.C.; Ghan, S.J.; Zaveri, R.; Rasch, P.; Shi, X.; Lamarque, J.-F.; Gettelman, A.; Morrison, H.; Vitt, F.; et al. Toward a minimal representation of aerosols in climate models: description and evaluation in the Community Atmosphere Model CAM5. Geosci. Model Dev. 2012, 5, 709–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twomey, S. Aerosols, clouds and radiation, Atmospheric Environment. Part A. General Topics 1991, 25, 2435–2442. [Google Scholar]

- Rémy, S.; Benedetti, A.; Bozzo, A.; Haiden, T.; Jones, L.; Razinger, M.; Flemming, J.; Engelen, R.J.; Peuch, V.H.; Thepaut, J.N. Feedbacks of dust and boundary layer meteorology during a dust storm in the eastern Mediterranean. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2015, 15, 12909–12933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmarini, S.; Hogrefe, C.; Brunner, D.; Makar, P.; Baklanov, A. Special issue section evaluating coupled models (aqmeii p2) preface (2015).

- Zender, C.S.; Miller, R.; Tegen, I. Quantifying mineral dust mass budgets: Terminology, constraints, and current estimates, Eos. Transactions American Geophysical Union 2004, 85, 509–512. D. Koch, G. A. Schmidt, L. D. Miller, D. T. Shindell, A. Voulgarakis, N. Unger, Distinguishing aerosol impacts on climate over the past century. Journal of Climate 2011, 24, 2693–2713. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, M.Z.; Kaufman, Y.J. Wind reduction by aerosol particles. Geophysical Research Letters 2006, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Miglietta, M.M. Mediterranean Tropical-Like Cyclones (Medicanes). Atmosphere 2019, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, G. Changing nature of Saharan dust deposition in the Carpathian Basin (Central Europe): 40 years of identified North African dust events (1979–2018). Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menut, L.; Tuccella, P.; Flamant, C.; Deroubaix, A.; Gaetani, M. The role of aerosol–radiation–cloud interactions in linking anthropogenic pollution over southern west Africa and dust emission over the Sahara. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2019, 19, 14657–14676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, S.P.; Stenchikov, G.L.; Ukhov, A.; Mostamandi, S.; Kucera, P.A.; Axisa, D.; Jr. , W.I.G.; Zhu, Y. Effect of dust on rainfall over the Red Sea coast based on WRF-Chem model simulations. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2022, 22, 8659–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaounas, E.; Davolio, S.; Raveh-Rubin, S.; Pantillon, F.; Miglietta, M.M.; Gaertner, M.A.; Hatzaki, M.; Homar, V.; Khodayar, S.; Korres, G.; et al. , Mediterranean cyclones: Current knowledge and open questions on dynamics, prediction, climatology and impacts. Weather and Climate Dynamics 2022, 3, 173–208. [Google Scholar]

- Fast, Jerome D., et al. "Evolution of ozone, particulates, and aerosol direct radiative forcing in the vicinity of Houston using a fully coupled meteorology-chemistry-aerosol model." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 111.D21 (2006).

- Briant, R.; Tuccella, P.; Deroubaix, A.; Khvorostyanov, D.; Menut, L.; Mailler, S.; Turquety, S. , Aerosol–radiation interaction modelling using online coupling between the wrf 3. 7.1 meteorological model and the chimere 2016 chemistry-transport model, through the oasis3-mct coupler. Geoscientific Model Development 2017, 10, 927–944. [Google Scholar]

- Tuccella, P.; Menut, L.; Briant, R.; Deroubaix, A.; Khvorostyanov, D.; Mailler, S.; Siour, G.; Turquety, S. Implementation of Aerosol-Cloud Interaction within WRF-CHIMERE Online Coupled Model: Evaluation and Investigation of the Indirect Radiative Effect from Anthropogenic Emission Reduction on the Benelux Union. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menut, L.; Bessagnet, B.; Briant, R.; Cholakian, A.; Couvidat, F.; Mailler, S.; Pennel, R.; Siour, G.; Tuccella, P.; Turquety, S.; et al. , The chimere v2020r1 online chemistry-transport model. Geoscientific Model Development 2021, 14, 6781–6811. [Google Scholar]

- Mailler, S.; Menut, L.; Khvorostyanov, D.; Valari, M.; Couvidat, F.; Siour, G.; Turquety, S.; Briant, R.; Tuccella, P.; Bessagnet, B.; et al. CHIMERE-2017: from urban to hemispheric chemistry-transport modeling. Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 10, 2397–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.; Valcke, S.; Coquart, L. Development and performance of a new version of the OASIS coupler, OASIS3-MCT_3.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 10, 3297–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, M.J.; Delamere, J.S.; Mlawer, E.J.; Shephard, M.W.; Clough, S.A.; Collins, W.D. Radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases: Calculations with the AER radiative transfer models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D13103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Eidhammer, T. A Study of Aerosol Impacts on Clouds and Precipitation Development in a Large Winter Cyclone. J. Atmospheric Sci. 2014, 71, 3636–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Razzak, H.; Ghan, S.J. , A parameterization of aerosol activation sectional representation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2002, 107, AAC–1. [Google Scholar]

- Ghan, S.J.; Leung, L.R.; Easter, R.C.; Abdul-Razzak, H. , Prediction of cloud droplet number in a general circulation model. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 1997, 102, 21777–21794. [Google Scholar]

- DeMott, P.J.; Prenni, A.J.; McMeeking, G.R.; Sullivan, R.C.; Petters, M.D.; Tobo, Y.; Niemand, M.; Möhler, O.; Snider, J.R.; Wang, Z.; et al. Integrating laboratory and field data to quantify the immersion freezing ice nucleation activity of mineral dust particles. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2015, 15, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, T.; Luo, B.; Tsias, A.; Peter, T. Water activity as the determinant for homogeneous ice nucleation in aqueous solutions. Nature 2000, 406, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-Y.; Noh, Y.; Dudhia, J. A New Vertical Diffusion Package with an Explicit Treatment of Entrainment Processes. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2006, 134, 2318–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Dudhia, J. Coupling an advanced land surface–hydrology model with the penn state–ncar mm5 modeling system. part: Model implementation and sensitivity. Monthly weather review 2001, 129, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grell, G.A.; Freitas, S.R. A scale and aerosol aware stochastic convective parameterization for weather and air quality modeling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 5233–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derognat, C.; Beekmann, M.; Baeumle, M.; Martin, D.; Schmidt, H. Effect of biogenic volatile organic compound emissions on tropospheric chemistry during the Atmospheric Pollution Over the Paris Area (ESQUIF) campaign in the Ile-de-France region. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, O.; Zhu, X.; Prather, M.J. Fast-J: Accurate Simulation of In- and Below-Cloud Photolysis in Tropospheric Chemical Models. J. Atmospheric Chem. 2000, 37, 245–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessagnet, B.; Hodzic, A.; Vautard, R.; Beekmann, M.; Cheinet, S.; Honoré, C.; Liousse, C.; Rouil, L. Aerosol modeling with CHIMERE—preliminary evaluation at the continental scale. Atmospheric Environ. 2004, 38, 2803–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, A.; Karl, T.; Harley, P.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Palmer, P.I.; Geron, C. Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using MEGAN (Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006, 6, 3181–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menut, L.; Mailler, S.; Siour, G.; Bessagnet, B.; Turquety, S.; Rea, G.; Briant, R.; Mallet, M.; Sciare, J.; Formenti, P.; et al. Ozone and aerosol tropospheric concentrations variability analyzed using the ADRIMED measurements and the WRF and CHIMERE models. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2015, 15, 6159–6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, E.C. In the role of air-sea exchange in geochemical cycling, chapter The ocean as a source of atmospheric particles. 1986, 129–163.

- Rizza, U.; Brega, E.; Caccamo, M.T.; Castorina, G.; Morichetti, M.; Munaò, G.; Passerini, G.; Magazù, S. Analysis of the ETNA 2015 Eruption Using WRF–Chem Model and Satellite Observations. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.-Y.; Yang, Z.-L.; Mitchell, K.E.; Chen, F.; Ek, M.B.; Barlage, M.; Kumar, A.; Manning, K.; Niyogi, D.; Rosero, E.; et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 1. Model description and evaluation with local-scale measurements. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, D.R.; Seaman, N.L. Multiscale four-dimensional data assimilation. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 1994, 33, 416–434. [Google Scholar]

- Ginoux, P.; Chin, M.; Tegen, I.; Prospero, J.M.; Holben, B.; Dubovik, O.; Lin, S.-J. Sources and distributions of dust aerosols simulated with the GOCART model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2001, 106, 20255–20273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Fung, J.C.H. Investigating the role of dust in ice nucleation within clouds and further effects on the regional weather system over East Asia – Part 1: model development and validation. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2018, 18, 8707–8725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeGrand, S.L.; Polashenski, C.; Letcher, T.W.; Creighton, G.A.; Peckham, S.E.; Cetola, J.D. , The afwa dust emission scheme for the gocart aerosol model in wrf-chem v3.8.1, Geoscientific Model Development 12 (1) (2019) 131–166.

- Ukhov, A.; Ahmadov, R.; Grell, G.; Stenchikov, G. , Improving dust simulations in wrf-chem v4.1.3 coupled with the gocart aerosol module, Geoscientific Model Development 14 (1) (2021) 473–493.

- Rizza, U.; Kandler, K.; Eknayan, M.; Passerini, G.; Mancinelli, E.; Virgili, S.; Morichetti, M.; Nolle, M.; Eleftheriadis, K.; Vasilatou, V.; et al. , Investigation of an intense dust outbreak in the mediterranean using xmed-dry network, multiplatform observations, and numerical modeling, Applied Sciences 11 (4) (2021) 1566.

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Wald, A.E.; Remer, L.A.; Gao, B.-C.; Li, R.-R.; Flynn, L. , The modis 2.1-/spl mu/m channel-correlation with visible reflectance for use in remote sensing of aerosol, IEEE transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 35 (5) (1997) 1286–1298.

- Hsu, N.; Jeong, M.-J.; Bettenhausen, C.; Sayer, A.; Hansell, R.; Seftor, C.; Huang, J.; Tsay, S.-C. , Enhanced deep blue aerosol retrieval algorithm: The second generation, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 118 (16) (2013) 9296–9315.

- Remer, L.A.; Tanr, D.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Levy, R.; Mattoo, S. , Algorithm for remote sensing of tropospheric aerosol from modis: Collection 005, National Aeronautics and Space Administration 1490 (2006).

- Giovannini, L.; Davolio, S.; Zaramella, M.; Zardi, D.; Borga, M. , Multi-model convection-resolving simulations of the october 2018 vaia storm over northeastern italy, Atmospheric Research 253 (2021) 105455.

- Davolio, S.; Della Fera, S.; Laviola, S.; Miglietta, M.; Levizzani, V. , Heavy precipitation over italy from the mediterranean storm “vaia” in october 2018: Assessing the role of an atmospheric river, Monthly Weather Review 148 (9) (2020) 3571–3588.

- Pignone, F.; Rebora, N.; Silvestro, F.; Castelli, F. , Griso (generatore random di interpolazioni spaziali da osservazioni incerte)-piogge, Rep 272 (2010) (2010) 353.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).