1. Introduction

How does the brain seamlessly integrate external feedback and internal action planning to learn subjective feeling of controlling one’s own actions and their effects on the external world, i.e., Sense of Agency (SoA), in uncertain environments? The process of SoA learning often involves balancing uncertainity in external feedback—such as sensory feedback or instructional cues—with uncertainty in internal action simulation to refine beliefs for future action planning. It is a fundamental aspect of volition and self-awareness, crucial for autonomy and well-being. Disruptions of SoA are implicated in various neuropsychiatric conditions (e.g. delusions of control in schizophrenia, sense of involuntariness in functional movement disorders). In everyday life, SoA underpins activities from driving a car to using a smartphone, where the brain must correctly attribute outcomes to one’s own actions even in complex human-technology interactions [1]. In Human–Machine Interfaces (HMI) – such as brain-computer interfaces, prosthetic limbs, or assistive automation – preserving and enhancing SoA is vital so that users feel “I did that” rather than “the system did that.” Achieving this requires sophisticated integration of neuroscience theory and design, ensuring that HMIs align with the brain’s predictive processes [2]. This review provides an overview of computation models as they relate to brain–behavior analysis of HMIs for learning SoA. I first outline the principles of predictive coding, Bayesian brain theories, and active inference. I then discuss how these frameworks explain SoA mechanisms, and survey their application in HMI design – from seminal theoretical works to recent advances–focusing on peer-reviewed studies and simulations.

2. Computational Models and Mechanisms

Predictive coding is a leading theoretical model of brain function in neuroscience, proposing that the brain is essentially a prediction machine. Rather than passively registering stimuli, the brain actively generates predictions of sensory inputs at multiple hierarchical levels and uses incoming data to update or correct these predictions [3]. In this view, perception and action result from minimizing prediction errors – the differences between expected sensory signals and actual input. Hierarchical generative models allow higher brain regions to predict activity in lower sensory areas, while only unexpected residuals (prediction errors) propagate upward. This framework has deep roots in the Helmholtzian idea of the brain as inferring causes of sensations [4], updated in modern form as the free-energy principle [5]. Free energy in this context quantifies surprise or prediction error; by minimizing it, the brain approximates optimal Bayesian inference about the world [3,6]. Predictive coding thus aligns with the notion of the “Bayesian brain,” which holds that neural computations implement Bayesian probability updating under uncertainty [7]. Indeed, predictive coding can be seen as an algorithmic motif that the brain uses to perform Bayesian inference, though it may serve other computational goals as well. Under this paradigm, perception becomes a constructive process: the brain’s best hypothesis (or internal forward model) about the causes of sensory inputs is compared against reality, and only unexpected deviations drive learning or new perception [3]. This accounts for many contextual effects in neural processing, such as reduced neural responses for expected stimuli and enhanced responses for surprising events (e.g. the mismatch negativity ERP when an oddball stimulus violates expectations).

Neurophysiologically, predictive coding finds support in both sensory and motor domains. In sensory cortex, ubiquitous top-down feedback connections likely carry predictions about expected features, while bottom-up connections carry error signals [3]. For example, primary visual neurons can respond to illusory contours or missing stimuli that higher-level context predicts should be there [7]. In motor control, a similar architecture is evident: descending signals from motor cortex resemble the feedback (modulatory) projections in sensory hierarchies rather than classic feedforward commands [8]. This led to the active inference reinterpretation of motor commands – that the brain issues motor instructions by sending predicted proprioceptive signals to the muscles, and reflex arcs then fulfill these predictions. In other words, instead of commanding a muscle directly, the brain predicts the sensory state (e.g. limb position) it wants, and the body responds to minimize the error. This perspective casts even basic reflexes as mechanisms to cancel out prediction errors, unifying perception and action under one predictive control scheme [8]. Such neural implementations make predictive coding a powerful model for understanding brain–behavior relationships. It explains phenomena like sensory attenuation: when we produce a movement, the brain’s prediction of the expected sensory consequences (via an internal forward model) attenuates the actual sensation [9]. For instance, self-generated touch or sounds feel less intense than external ones, because the brain anticipated them. If the actual feedback deviates from prediction (e.g. a delay or perturbation is introduced), the prediction error triggers surprise and a change in perception – the basis for why one cannot tickle oneself effectively. This mechanism, present in healthy brains, is disrupted in schizophrenia—where impaired predictive attenuation leads to hallucinations and passivity—and in Functional Motor Disorder (FMD), where excessive suppression of sensory consequences diminishes the sense of agency, making movements feel involuntary [10].

2. Mechanisms of Sense of Agency

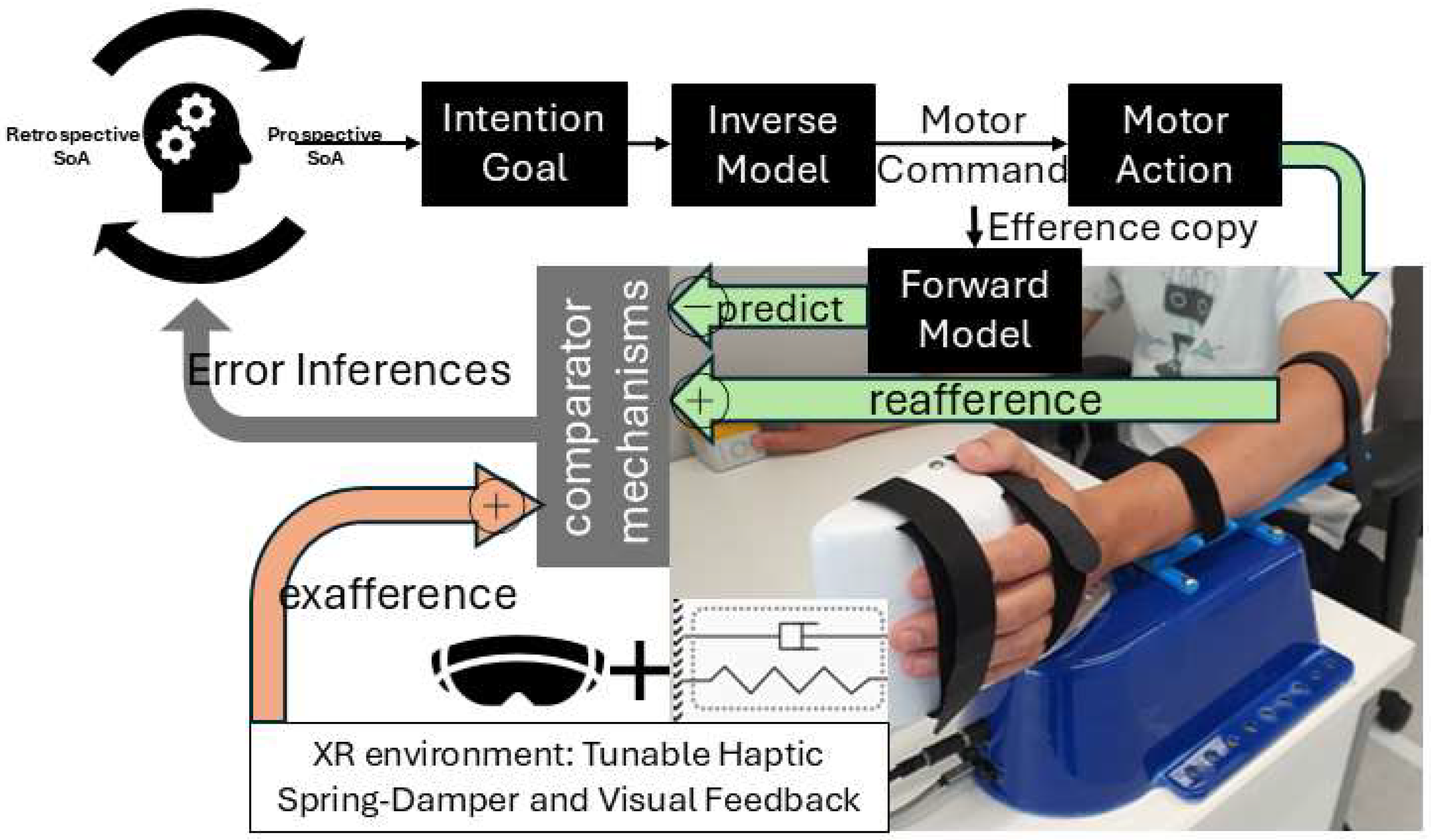

The sense of agency (SoA) arises when our brain attributes an action and its outcome to our own intent. Classic theories in cognitive neuroscience have long postulated that SoA critically depends on predictive mechanisms. The influential comparator model (see

Figure 1) suggests that when we plan (inverse model) a voluntary action, an efference copy of the motor command is used by a forward model to predict the expected sensory consequences [1]. This predicted outcome (e.g. the sight, sound, or feel of the action’s effect) is then compared to the actual sensory feedback. If the actual outcome matches the prediction, the brain registers that “I caused this,” reinforcing SoA. If there is a mismatch – for instance, the outcome is delayed, deviated, or differs in an unexpected way – a discrepancy signal arises, and SoA is reduced or even abolished. Empirical evidence for this comparator mechanism comes from studies showing that altering feedback can modulate agency. For example, introducing temporal or spatial offsets between a person’s movement and its visual/auditory effect reduces the person’s feeling of control over that effect. Similarly, as noted, people cannot tickle themselves because the somatosensory consequences of a self-generated movement are predicted and hence attenuated; if that prediction is disrupted (e.g. by introducing an unexpected delay or using a robot arm to self-stimulate with altered feedback, i.e., with exafference [11]), the self-produced touch can feel more ticklish and less self-caused. These observations align perfectly with predictive coding: SoA is strongest when prediction error is minimal (expected and actual align), and it diminishes as prediction error increases. Consistent with this, predictability of outcomes has been shown to directly shape the agency. One view holds that agency is mostly inferred retrospectively – after action – based on how well the outcome matches the motor system’s predictions. That is, the brain “decides” one was the agent if the sensory evidence fits the forecast of one’s own action effects i.e. from the comparator mechanisms. However, more recent research indicates prospective cues also play a role: the fluency or ease of selecting and initiating an action can influence SoA even before outcomes are known. In other words, when an action feels effortful or unusually constrained, people report lower agency, independent of the eventual outcome. Neuroimaging studies support this by linking feelings of agency to activity in premotor and parietal regions during action selection, not just outcome comparison, emphasizing the role of prospective cues [12,13] that can be delivered with exafference for rehabilitation [14,15]. Here, predictive coding provides a computational design framework in which the brain’s top-down expectations and bottom-up inputs interact constantly to guide perception and action [7].

3. Predictive Coding Framework

Predictive coding is closely tied to broader Bayesian brain theories, which posit that the brain encodes probabilistic beliefs and optimally combines prior expectations with sensory evidence [16]. In uncertain environments, behaving effectively requires weighing what we already expect against what our senses are telling us – essentially performing Bayesian inference [6,17]. Ample behavioral evidence supports this: humans combine cues (visual, proprioceptive, etc.) in a statistically optimal (Bayes-like) manner in tasks ranging from depth perception to motor adaptation. Under linear and gaussian assumptions, classic results show that neural integration can approach Bayes-optimal weighting of information (as in the Kalman filter model of sensorimotor integration [18]) [17]. Bayesian predictive coding merges these ideas by suggesting the brain’s generative model encodes a probability distribution and prediction errors correspond to updating of posterior beliefs. In fact, predictive coding has been described as a particular implementation of Bayesian inference – one way the brain might achieve approximate Bayes-optimality through hierarchical error minimization [7]. Bayesian inference can be implemented without predictive coding, but combining them through continual prediction-error minimization creates a simpler and more efficient approach following Occam's Razor [19,20].

The brain’s ability to infer causes (like intentions behind others’ actions or the structure of a task) can be seen as building an internal Bayesian model and continuously refining it as new data arrives. Active inference extends these concepts further by incorporating action into the predictive loop. It arises from the free-energy principle, which broadly states that organisms behave in ways to minimize the long-term surprise (or free energy) of their sensory states [21]. In active inference theory, perception and action are two sides of the same coin: perception optimizes internal predictions to fit sensory input, while action changes the external input to better fit the internal predictions [8]. In other words, if a mismatch exists between what the brain predicts and what it senses, it can either update its belief (perceptual inference) or act to make reality more like the prediction (active inference). This dual strategy means the brain’s control of the body is fundamentally model driven. As noted by Friston et al., higher-level cortical areas send descending proprioceptive predictions (desired limb positions) instead of explicit motor commands, and the motor plant reacts reflexively to reduce the resulting error [8]. This aligns with the Equilibrium Point Hypothesis (EPH), introduced by Anatol Feldman [22], that posits the central nervous system controls movements by setting desired equilibrium positions (desired limb positions) for muscles, allowing the inherent properties of muscles and reflexes to drive the limb toward these positions without specifying exact trajectories. This suggests that movement disorders (e.g., Functional Motor Disorder, Parkinson’s) may arise from disrupted predictive tuning of equilibrium points, leading to abnormal motor execution [23–25]. Here, active inference extends EPH by adding a predictive dimension, allowing the nervous system to update equilibrium points dynamically. Through this lens, classical notions of reward or utility maximization are reformulated as inference: actions are chosen based on prior beliefs about achieving preferred outcomes, rather than directly maximizing reward [21]. For example, active inference models associate SoA with a prior belief that “I am in control of my actions,” which is only violated when prediction errors become too large. This formalism can even recapitulate constructs from economics and decision theory – e.g. expected utility emerges as a special case of free-energy minimization when the brain’s confidence (precision) in its action-outcome model is tuned optimally. The effectiveness of this adjustment depends on the brain's estimation of precision, akin to the Kalman gain in control theory, which determines the weight assigned to new sensory information versus prior beliefs [26]. However, this precision estimation is not always optimal [9]. In conditions like Functional Neurological Disorder (FND), the brain instead of updating beliefs in response to sensory feedback may attempt to force ‘reality’ to conform to their predictions [9]. This maladaptive strategy reinforces learned helplessness in FND, where repeated failures to control outcomes strengthen internal models subserving lack of SoA. In summary, active inference provides a unifying framework: it not only accounts for perception as hierarchical Bayesian inference (akin to predictive coding) but also embeds the selection of actions into the same inferential process in health and disease [21]. This has practical implications for HMI design and robotics [11,14]. By harnessing the brain's natural mechanisms of predicting sensory consequences and correcting errors, these HMI systems can facilitate human interactions while also serving as rehabilitation tool by modifying sensory feedback to drive operant conditioning and adaptive learning [27]. Human interactions involve two key metacognitive components of agency: awareness ("brain as observer"), recognizing strengths, weaknesses, and effective strategies; and regulation ("brain as controller"), taking action based on these insights [9].

4. Kalman-Bucy Filter and Linear-Quadratic-Gaussian Optimal Control

Kalman filters, widely applied in both engineering and neuroscience, offer a mathematically simple yet powerful framework for modeling dynamic sensorimotor integration. The Kalman filter operates in discrete time, updating state estimates at specific intervals, while the Kalman-Bucy filter works in continuous time, providing real-time updates via differential equations [26]. Discrete-time Kalman filters are commonly used in neuroscience because neural data is sampled in small time steps, making them intuitive for modeling brain-behavior dynamics. They help explain how the brain combines noisy sensory inputs with prior beliefs and internal simulations to optimize perception and learning [18]. These mechanisms are crucial not only for skill acquisition but also for clinical interventions, making Kalman filters valuable tools for understanding learning in complex, uncertain environments [17]. Despite their usefulness in modeling brain processes related to perception and action [7], Kalman filters have notable limitations, particularly their reliance on assumptions such as linearity (system's dynamics and observation models are linear), Gaussian noise (both process noise and observation noise), and stationarity (state transition matrix, observation matrix, noise covariances) [28].

Consider the scenario in

Figure 1 where "Hoop Hustle" is an XR therapeutic game designed for upper arm rehabilitation [29]. Participants use their affected arm to shoot virtual balls through hoops positioned at varying locations. Real-time visual feedback helps adjust movement accuracy and speed. Successful attempts provide immediate visual and auditory rewards. Game difficulty (e.g., hoop size and height) is adjustable to individual capabilities emphasizing positional biofeedback. The participants must move the open palm handle to bring a ball (y) displayed in XR to a specified target (r) within a predetermined time (N). Achieving this goal provides a reward (e.g., visual/auditory feedback). The task objective can be formally described as minimizing a quadratic cost function that captures both reward-based positional accuracy and energy expenditure:

Here, y(N) is the ball position at final time N; r is the target location; Q is a matrix defining the positional error cost at the final time (t = N); u(t) denotes motor commands at time t; L represents the cost associated with motor commands. The relative magnitude of Q and L indicates the trade-off between error cost and effort – this may subserve comorbid fatigue in FND [30]. Here, the effort can be modulated using virtual spring-damper as shown in

Figure 1 to modulate the trade-off between error cost and effort.

To successfully complete the task, participants require an internal model i.e. predictive relationship between motor commands and their sensory outcomes (e.g., proprioceptive and visual states). Since this is a novel task for the participants so this must be learned [31] where we represent the state-space model dynamics linearly as follows,

State prediction:

Sensory feedback prediction:

Where

is the predicted state (e.g., body and ball) at time t given actual sensory feedback up to that time;

,

, and

are learned (adapted over time through experience) matrices defining how states evolve without input (e.g., physics of arm dynamics) (

is state transition matrix), how motor commands (e.g., muscle activations) affect the states (

is the control matrix), and how internal states map to sensory feedback (e.g., vision, proprioception) translating into their prediction,

(

is the observation matrix); where

is the predicted state at time t+1 given predicted state,

, and motor command,

, at time t. The controllability matrix

and the observability matrix

where n is the number of state variables. The state estimate update (correction) at time t+1 given new sensory feedback at t+1,

, will be

. Mixing gain matrix,

, determining how much the state estimate should be corrected based on prediction errors (balances between prediction and measurement), which may not be optimal (Kalman gain) in FND [9].

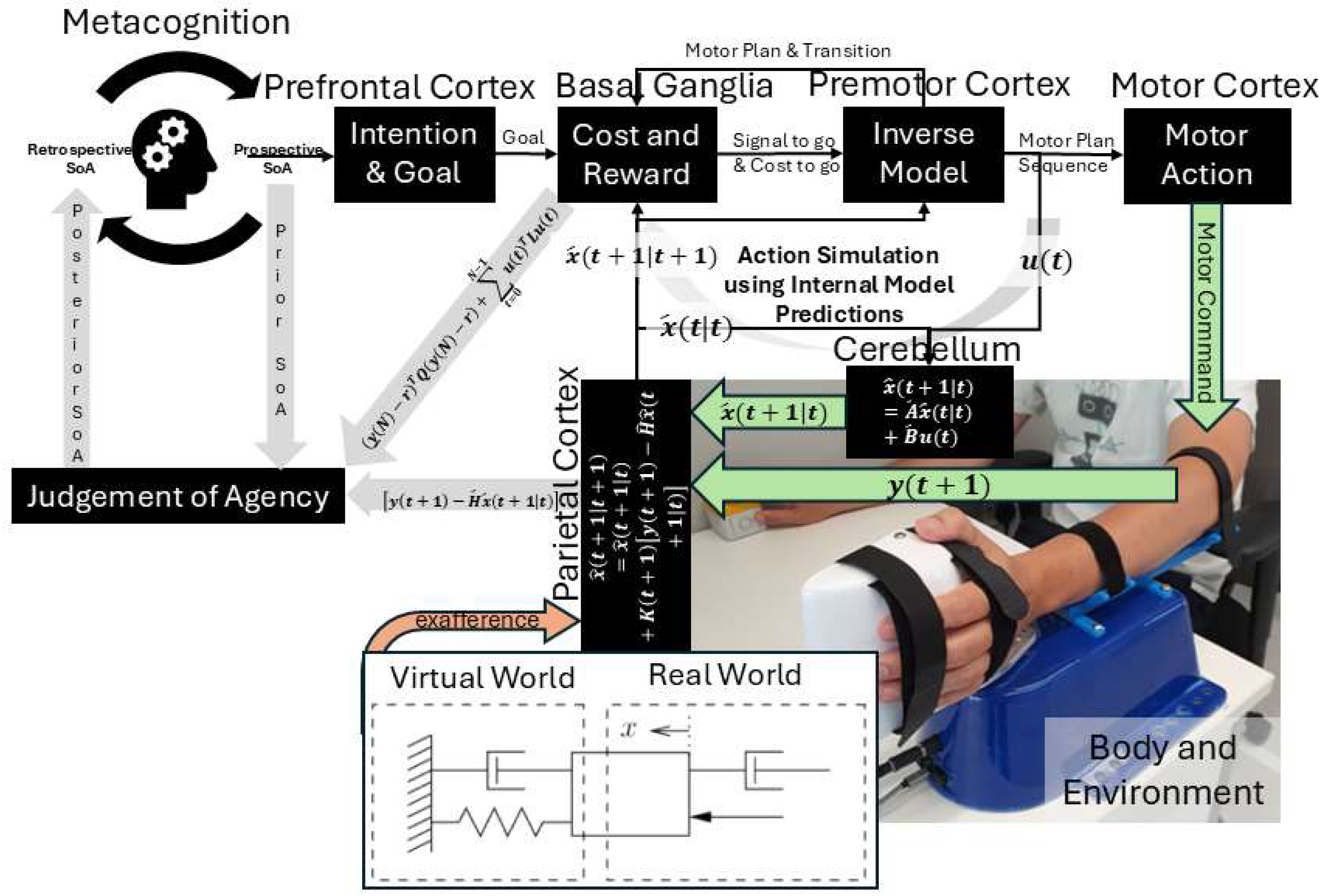

Figure 2 expands on

Figure 1, highlighting the parallel roles of feedforward simulation and delayed reafferent feedback in motor control.

Figure 1 outlines the flow of motor control and agency, starting with the Prefrontal Cortex, which sets intentions and supports metacognitive evaluation of agency before and after action. The Basal Ganglia evaluates a combination of cost and reward by minimizing an objective function of the form, (

), using internal inverse models (formulated by Premotor Cortex), selecting the optimal motor plan that minimizes this cost till final time (t = N). Once the best motor plan is selected, it delivers a "Go" signal to initiate the corresponding motor plan sequence till final time (t = N). The Supplementary Motor Area (SMA) complex receives the optimal motor command selected by upstream evaluative systems (e.g., Basal Ganglia). This command is issued to the Primary Motor Cortex (M1) for execution and is simultaneously broadcast as an efference copy to internal forward models (Cerebellum) [14]. This efference copy serves as an input to a predictive model—often formalized as part of a Kalman filter state estimator—which generates an internal prediction of the movement’s sensory consequences. These predictions are then compared against actual sensory feedback to compute a prediction error, which is used to update the current belief, i.e., update (Parietal Cortex) about the system’s state (e.g., body and environment). I further postulate that the prediction error serves as a key computational signal in the Judgement of Agency. This prediction error reflects the mismatch between predicted and actual sensory feedback and is integrated with additional contextual variables such as final cost and reward (Basal Ganglia) associated with the action, and the prior belief about agency held before the action – together, these signals shape a posterior SoA. Interaction with the Body and Environment—including exafference via a virtual spring-damper system (HRX-1 robot [32])—enables perturbations using exafference to probe goal directed movement and provide operant conditioning (by modulating effort, L) in dysfunctions like those seen in FND [15]. Given these estimates, the control problem (subserved by the Basal Ganglia↔Premotor cortex loop) reduces to finding the motor commands (u(t)) that minimize the expected future costs ("cost-to-go" (Riccati) equation)[31],

, where G(t) is the feedback gain at time t, computed recursively backward via a dynamic programming algorithm that solves the underlying Linear-Quadratic-Gaussian (LQG) optimal control problem [33] (optimality assumed in healthy individuals [34]), i.e.,

The feedback gains (G(t)) encodes how beliefs about states map into motor commands, effectively defining the optimal control policy based on backward recursion (Riccati equation). Here, movement elements are consolidated (e.g., motor chunking [35]) with state estimation computed forward in time and optimal control computed backward to guide action. In FND, the control policy may not be optimal [9] inhibiting the action.

In practice, motor commands

introduce noise,

, that can be modeled as zero-mean Gaussian noise whose variance is proportional to the magnitude of the control signal itself,

, where

is an independent standard Gaussian random variable. Thus, the full stochastic dynamics of the internal model are,

Where εₓ and

denote additive Gaussian noise in state evolution and sensory observations, respectively, with covariance matrices X and Y. During XR game play, sensory measurements y(t) is continuously integrated with model predictions

to update beliefs about the state.

In control theory, two key properties—controllability and observability—determine whether a system can be effectively regulated and monitored. A system is controllable if it can be driven from any initial state to a desired one through control inputs (evaluated via the controllability matrix). It is observable if its internal states can be reconstructed from external outputs (determined through the observability matrix). These dual properties are foundational in designing adaptive and stable systems, such as in robotics [28]. Extending this framework, I propose that judgment of agency depends on the perceived controllability and observability of one’s body and environment, learned through a metacognitive Ladder of Causation. When observability is reduced (e.g., due to societal opacity), or controllability is undermined (e.g., by coercion), one’s sense of agency can deteriorate. Mental simulation can serve as a representational tool for understanding both the self and others [36] through a metacognitive Ladder of Causation. As illustrated in

Figure 2, mental imagery can engage action simulation via the Forward Model, which can be shaped by external suggestions (exafference) [37]. Hypnotic suggestion (considered exafference), often defined as a process that enhances the realism of imagined scenarios, can shape perceptions of body ownership, agency, and size [38]. Hypnotic suggestions are typically preceded by hypnotic induction techniques, such as focused breathing and heightened bodily awareness [38]. In this state of “focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness, characterized by an enhanced response to suggestion” [39], reafference is minimized and suggestions are trusted as sole sensory input (exafference),

, shaping state expectations

. Then, mental imagery, as a form of enactment imagination [40], relies on sensory visualization and shares neural mechanisms with perception. Mental imagery functions as an internal simulation system, using forward models to predict the outcomes of potential actions and guide belief updating [9]. This process supports adaptive learning and problem-solving by enabling the brain to simulate future scenarios without physical movement. In the context of insight meditation, however, there is no external sensory feedback (reafference); instead, the mind primarily engages with internal noise (

) [9]. Through consistent meditation practice, the variance of this internal noise (

) is reduced, enhancing the state expectations

[9].

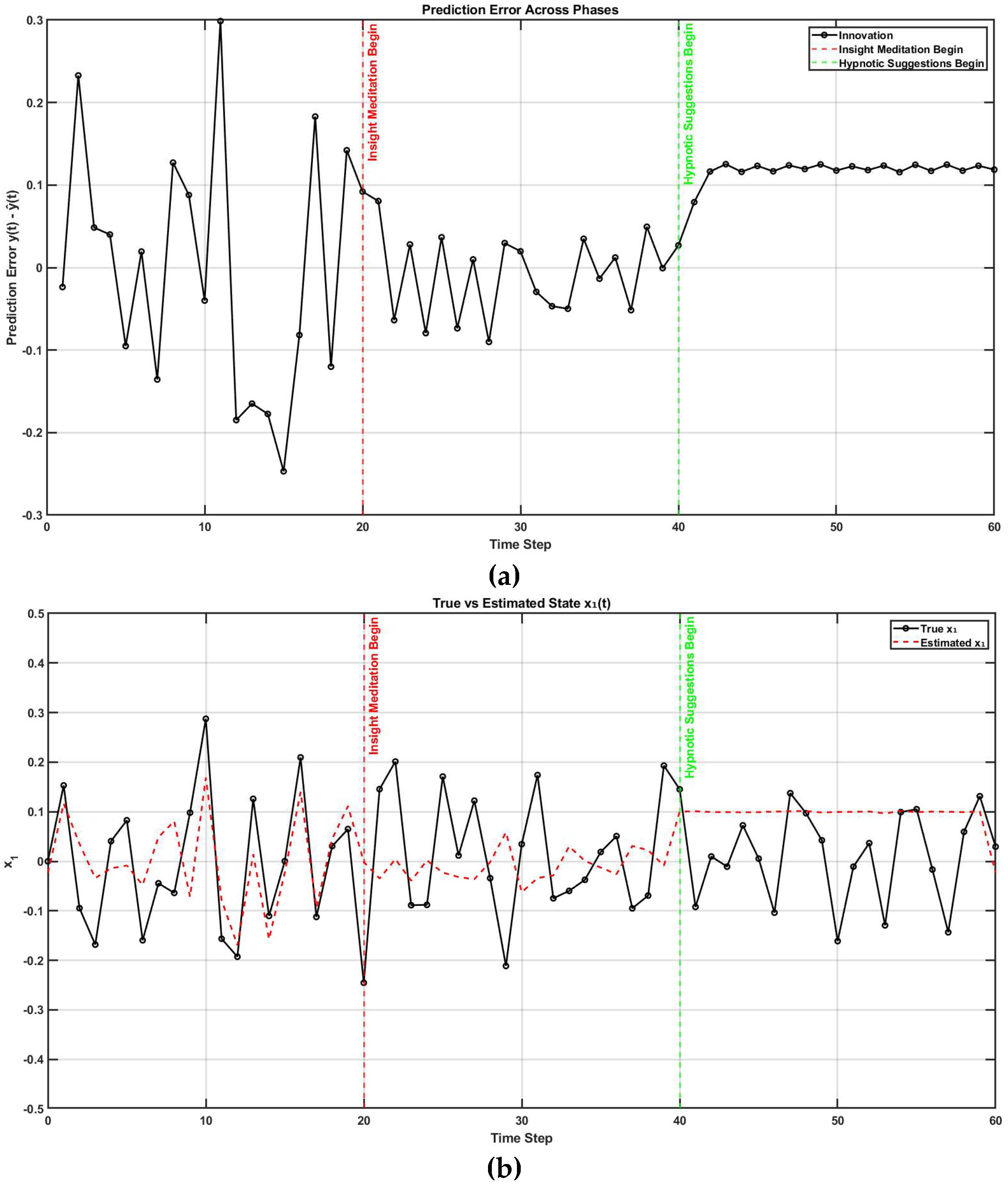

Figure 3 shows MATLAB (Mathworks Inc. USA) simulation of a three-phase cognitive control process using LQG framework to model how full attention on all sensory inputs, internal simulation without sensory input (in Insight Meditation [9]), and hypnotic suggestions without sensory input affect state estimation and motor behavior (code, figure3.m in

Supplementary Materials). It simulates a 10 Hz oscillatory system (physiological oscillations ~10Hz) under feedback control, with state estimates updated via a Kalman filter. In Phase 1 (t = 1–20), the system has access to all sensory inputs (reafference) and uses a Kalman filter for internal state estimate — representing a condition with full attention to sensory inputs. In Phase 2 (t = 21–40), sensory input (reafference) is no longer available, but the system continues to simulate internal dynamics with minimal external noise, representing internal simulation in Insight Meditation [9] where belief updating is mostly driven by prior expectations. In Phase 3 (t = 41–60), the system incorporates external suggestions (bias term for exafference as sensory input), simulating how hypnotic suggestions can shape future expectations in the absence of real-world sensory input. Throughout, the code tracks prediction error and applies LQR-based control using the estimated state. These results are visualized through two complementary figures: a prediction error plot (

Figure 3a) and a comparison of true versus estimated position over time (

Figure 3b). Together, these plots illustrate how hypnotic suggestions dynamically modulate belief updating and motor control. Specifically, the persistence of steady-state prediction error under suggestions reflects a biased setpoint, which—according to the Equilibrium Point Hypothesis—can drive limb movement even in the absence of conscious motor intent. In line with these simulation results, I propose the integration of virtual reality (VR)–based hypnotic suggestion within a platform technology for eXtended Reality biofeedback training under operant conditioning (using suggestions) for functional limb weakness [41]. In this framework, brain imaging—particularly beta synchronization observed in the SMA during post-movement stages in individuals with FND—can provide a biomarker of sensorimotor integration (efferent copy,

–

Figure 2) [42]. Prior research has demonstrated that the hypnotic state modulates sensorimotor beta rhythms during both real movement and motor imagery [43]. Hypnotic suggestion has been shown to alter motor cortex excitability [44] and modulate corticospinal output during motor imagery [45], highlighting its potential as a tool for reshaping dysfunctional motor representations [46]. These findings open new avenues for applying cognitive neuroscience principles [47] to XR therapeutic interventions in FND.

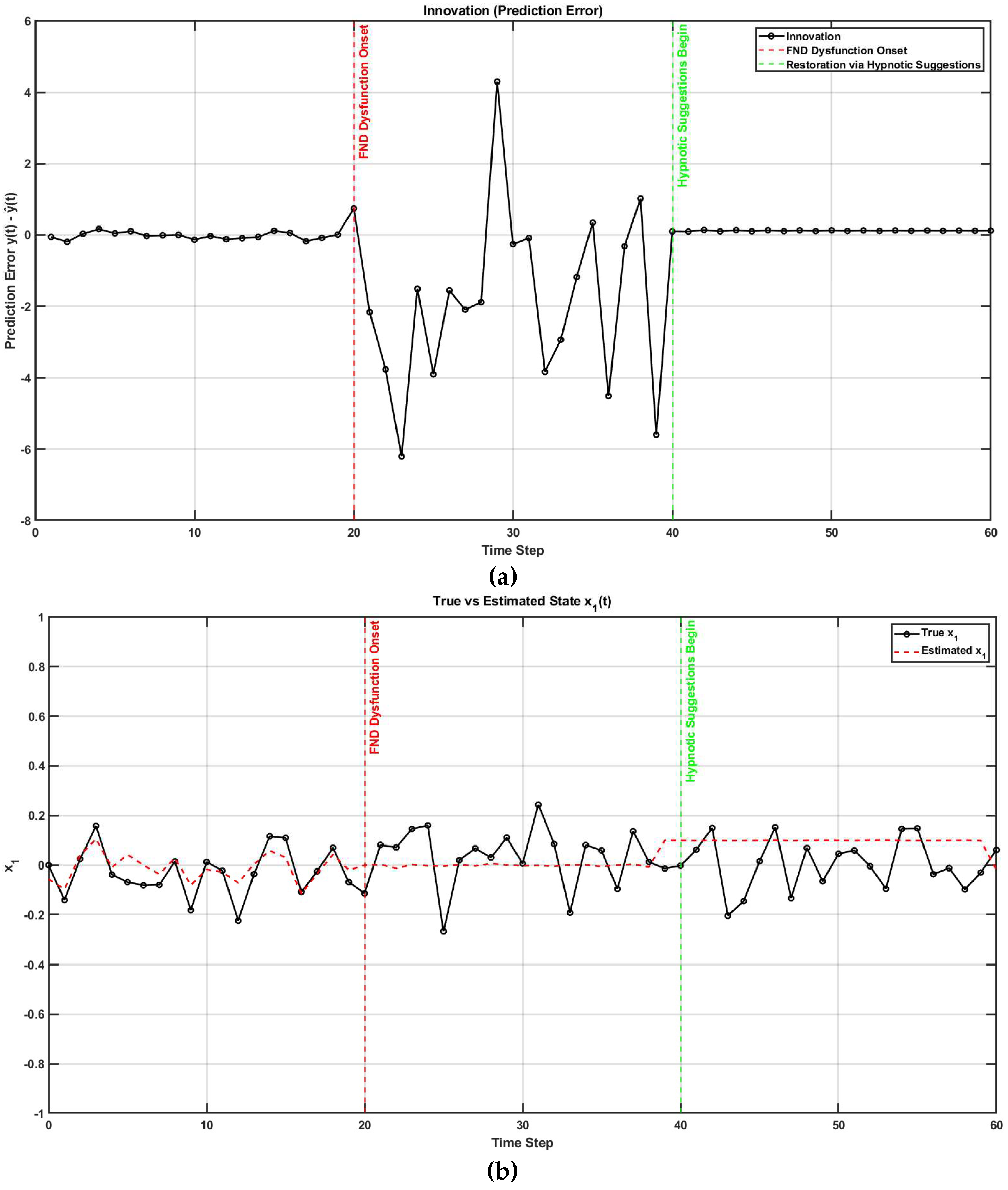

Figure 4 shows MATLAB (Mathworks Inc. USA) simulation how altered sensory integration in FND affects motor control [10,48] and how hypnotic suggestions may restore normal function (code, figure4.m in

Supplementary Materials). Initially, the Kalman gain is optimal, allowing accurate integration of sensory feedback and internal predictions. At t = 20, the Kalman gain becomes suboptimal, simulating FND-like dysfunction where the brain underweights sensory input (i.e., overconfidence in prior beliefs) [49]. This leads to growing prediction errors and poor state estimation. At t = 40, hypnotic suggestions are introduced by restoring sensory precision (focused attention with hypnotic induction), which increases Kalman gain and improves belief updating [9]. The observed reduction in prediction error (

Figure 4a) and the convergence between estimated and true states (

Figure 4b) demonstrate how hypnotic suggestions can recalibrate the balance between sensory evidence and internal models, effectively correcting the disrupted inference seen in FND. Reduction in prediction error facilitates a posterior sense of agency with hypnotically suggested movements that feel involuntary so effortless.

Kalman Filter and LQG aligns with active inference, a framework in which the brain predicts sensory outcomes of movements and minimizes discrepancies between expected and actual sensations by adjusting motor commands (inverse model) and/or updating predictions (forward model). Here, I propose that this framework needs to incorporate the Ladder of Causation [50], a framework introduced by Judea Pearl, which consists of three levels:

Association – Recognizing correlations between variables without inferring causality i.e. associative learning using comparator model (prediction error=∥expected outcome−observed outcome∥) [51].

Intervention – Understanding the effort and impact of deliberate actions on outcomes, moving beyond passive observation i.e. active inference (active minimization of variational free energy) [52].

Counterfactuals – Engaging in retrospective revaluation [9], leading to causal reasoning i.e. causal inference (counterfactual regret minimization) [53].

Integrating causal reasoning using retrospective revaluation within the framework of Kalman Filter and LQG enhances motor control through action execution and adapt via predictive and counterfactual learning, thereby implementing realistic judgment of agency [54]. Activation in the right prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum was observed during retrospective revaluation [55], providing support for such learning. Based on the conceptual model presented in

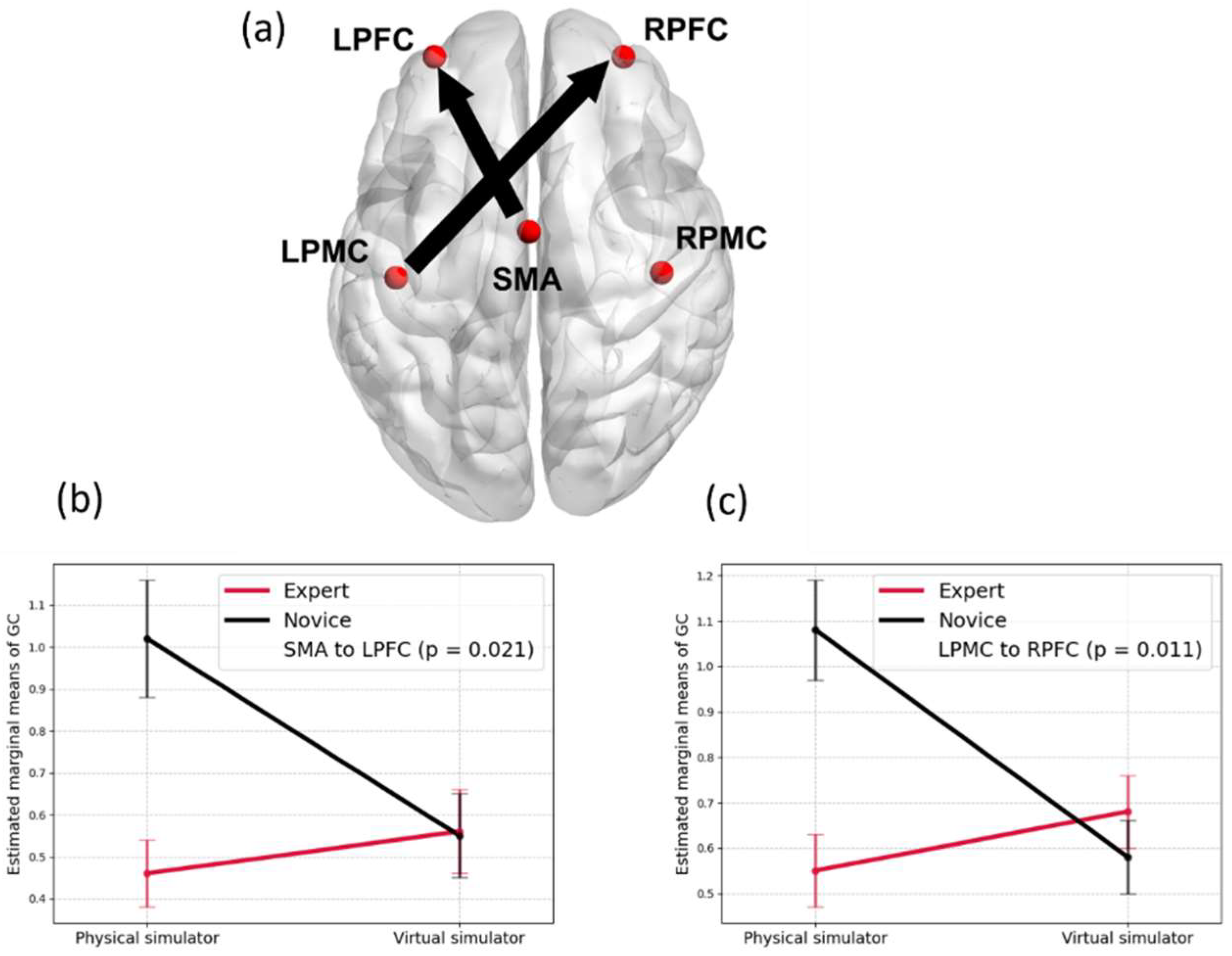

Figure 2, it is proposed that skill learning with simulator technology involves the judgment of agency, which is supported by the interaction between expertise (experience level) and simulator (contextual realism) on directed brain connectivity [56]. Specifically,

Figure 5 illustrates how the judgment of agency (evaluation of SoA by novices and experts – see

Figure 2) is influenced by the interaction between expertise and simulator type during skill learning. In this context of laparoscopic surgical skill acquisition [56], the virtual simulator is novel for both groups, while the physical simulator is only novel to novices. The analysis reveals significant differences in directed brain connectivity between groups, specifically from the Supplementary Motor Area (SMA) to the Left Prefrontal Cortex (LPFC), and from the Left Sensorimotor Cortex (LPMC) to the Right Prefrontal Cortex (RPFC)—regions implicated in motor planning and retrospective evaluation of actions.

In the context of the Free Energy Principle [52], the brain updates its internal model to minimize free energy, effectively reducing prediction errors. Within a causal inference framework, the brain retrospectively revaluates interventions—through action execution and action simulation—to discern for causal associative learning [55]. Counterfactual Regret Minimization (CFR) is a computational method used to approximate Nash equilibria in extensive-form games [53]. CFR is guaranteed to converge to a Nash equilibrium in two-player, zero-sum games with perfect recall, where players remember past decisions. When noise is introduced—reflecting real-world uncertainty—players may not settle into a fixed strategy but instead exhibit patterns consistent with a stochastic equilibrium, where strategies are stable on average. This approach offers a more realistic understanding of human decision-making and supports causal associative learning models [57].

5. "Brain as controller" vis-à-vis "Brain as observer" in Skill Learning

In this section, I examine self-generated, task-initiated brain activations as described by Brechet et al. [58], mapping them onto the steps of the Kalman Filter and Linear-Quadratic-Gaussian (LQG) Optimal Control framework introduced in

Section 4. This analysis is conducted using functional brain dynamics identified through a combined functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and electroencephalogram (EEG) microstate analysis from prior work [59].

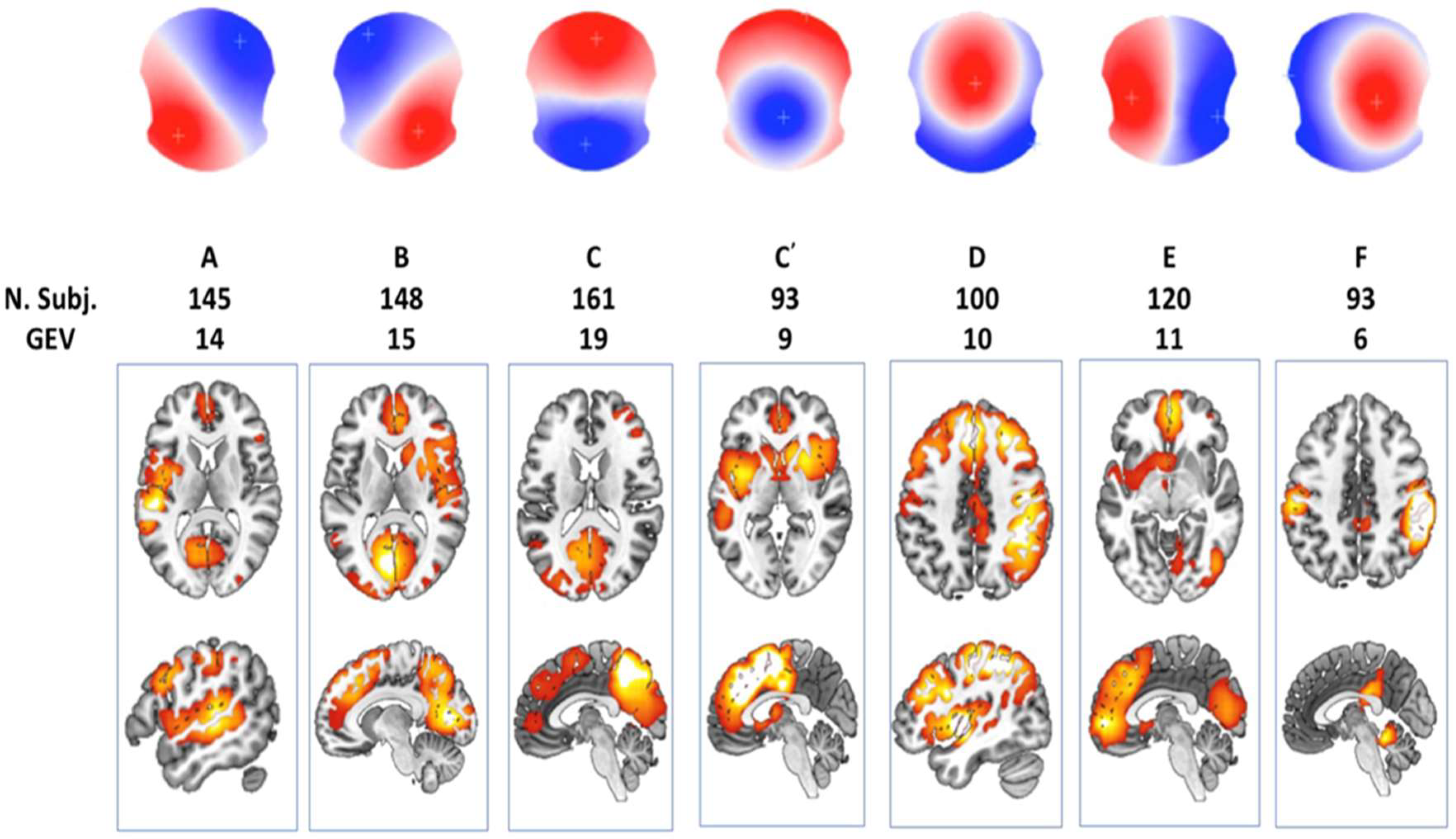

Figure 6, adapted from a review by Michel and Koenig [60], illustrates canonical EEG microstates, each representing distinct brain activation patterns associated with unique and shared cortical regions. The classic four-state scheme (labeled A, B, C, and D) is presented, along with additional variants C′, E, and F. Microstates A and B represent diagonal opposites in spatial distribution (e.g., left-anterior to right-posterior for A, and the reverse for B). Microstates C and D exhibit strong anterior-posterior contrasts with inverted polarities—Pattern C shows red frontal and blue occipital regions, while Pattern D shows the opposite. Variant C′ features a central polarity surrounded by an oppositely charged ring, whereas E and F introduce lateral (left-right) and fronto-central asymmetries in datasets that exceed the four-class model. These spatial patterns help characterize which lobes (frontal vs. occipital) and hemispheres (left vs. right) exhibit primary positivity or negativity. Notably, the data—collected from 164 participants using a 256-channel EEG system—demonstrate that not all individuals express every microstate, particularly for patterns C and D, suggesting inter-individual variability. This is further highlighted by the division of Microstate C into subtypes, reinforcing the non-uniformity of brain activation patterns.

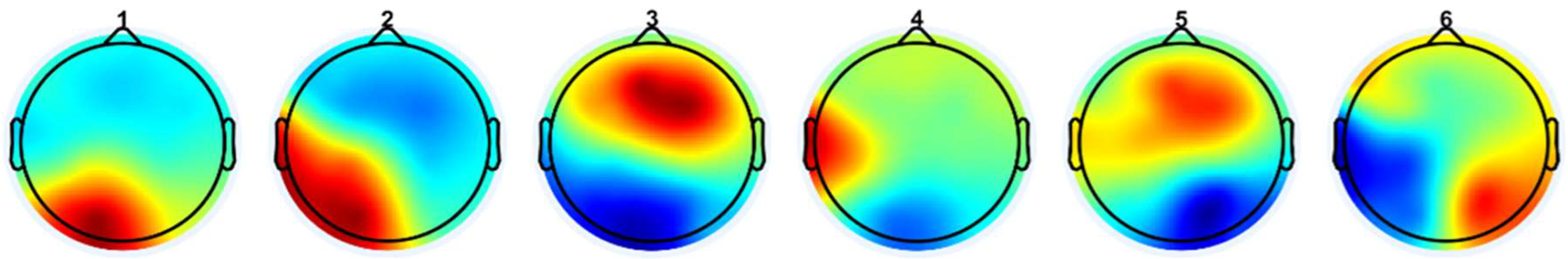

Figure 7 presents EEG-fNIRS microstate patterns from our own study [59]. Pattern 1 reveals inferior/posterior positivity and superior negativity. Pattern 2 exhibits a diagonal gradient with lower-right positivity and upper-left negativity. Pattern 3 emphasizes fronto-central positivity and posterior/inferior negativity. Pattern 4 features a left-right asymmetry, with a red hotspot over the left-central area and blue-green activity on the right. Pattern 5 reflects frontal or fronto-superior positivity versus posterior negativity. Pattern 6 displays a bilateral dipole, with left and right hemispheres showing opposing polarities depending on the color scale. A qualitative comparison between these patterns and those from the review paper [60] suggests partial overlaps, though not exact one-to-one correspondences. Specifically, our MS patterns 1 and 3 show anterior-posterior polarity distributions, resembling review MS patterns C or D, depending on sign. MS pattern 2 corresponds to the diagonal structure of patterns A or B. MS patterns 4, 5, and 6 demonstrate lateral asymmetries, analogous to review patterns E and F [59].

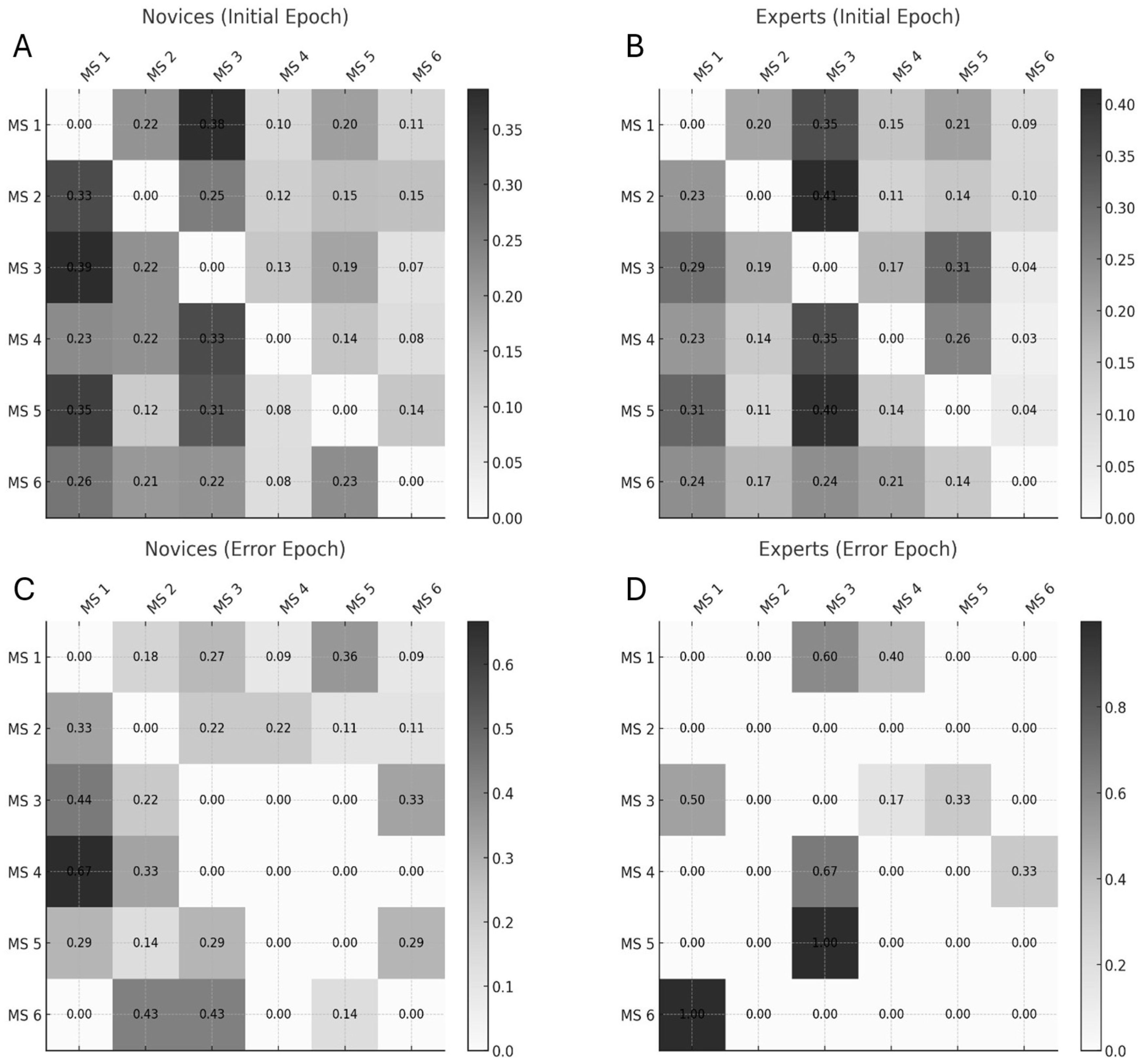

Interestingly, the review paper [60] also distinguishes MS pattern C′ as a separate subtype, further segmenting the classic C pattern beyond the six-state models used in Walia et al. [59] and Brechet et al. [58] – this suggests a finer classification granularity. When comparing EEG microstates across studies, several methodological factors must be considered. Polarity inversion is common due to the arbitrary nature of EEG map signs—e.g., a red-top/blue-bottom pattern is functionally equivalent to a blue-top/red-bottom one. Differences in referencing schemes (such as common-average vs. average-mastoid) can also shift or tilt topographies. Moreover, the number of microstates modeled (e.g., 6 vs. 7) can impact classification outcomes, where additions like C′ reflect finer subtyping within established categories. To objectively evaluate the similarity between the review’s microstates (A–F) and our own (1–6), we compute Pearson correlation coefficients and mean squared errors (MSE) between their spatial distributions, using normalized pixel values. This quantitative comparison provides an empirical basis for mapping and aligning microstates across studies. Transition probabilities between EEG microstate classes (see

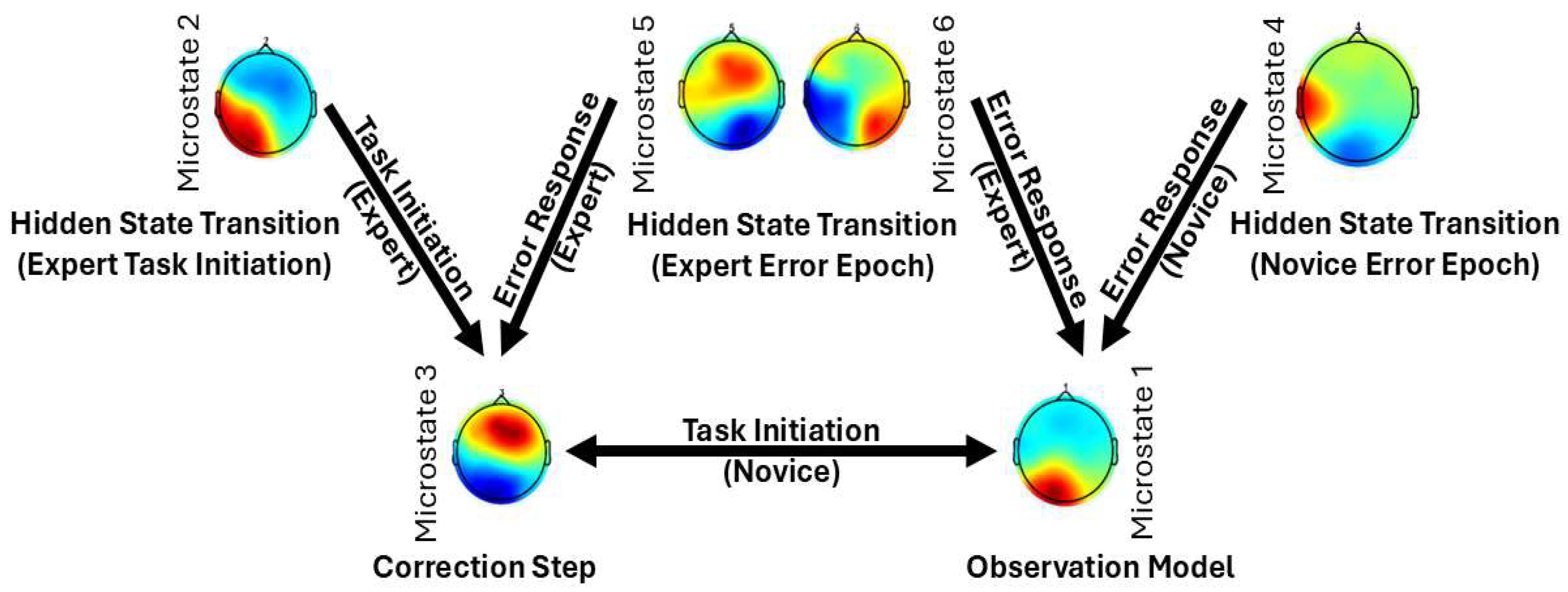

Figure 8) revealed distinct patterns differentiating experts from novices in their brain responses to task errors, as reported in Walia et al. [59]. These neural responses were mapped onto steps of the proposed Kalman filter model, wherein predicted internal states are adjusted based on sensory prediction errors—a process central to motor control and error correction.

A key mechanism underlying expert performance is implicit mental imagery, which refers to the unconscious activation of sensorimotor brain regions during motor tasks. Unlike explicit mental imagery, where individuals intentionally visualize movement, implicit imagery occurs automatically—often during motor planning or real-time error correction—and is especially prominent in expert performers [61,62]. In the study by Walia et al. [59], the expert group consisted of nine attending surgeons and residents with over one year of experience in laparoscopic surgery, while the novice group included thirteen medical students with no prior exposure to laparoscopic procedures. This contrast allowed for the examination of expertise-related neural signatures during task performance and error monitoring. Further extending this investigation, a separate study [62] involved a cohort of surgical trainees and professionals performing an explicit mental imagery task. In this task, participants—comprising Junior residents (PGY 1–3, n=10), Senior residents (PGY 4–5, n=10), and Attending surgeons (n=10)—were asked to dictate a simulated operative note, simulating the cognitive demands of intraoperative decision-making. During the surgical epoch of this dictation task, brain activity was recorded using fNIRS, focusing on prefrontal, sensorimotor, and occipital regions. These data were used to analyze underlying brain states, offering insight into how different levels of surgical expertise manifest in distinct neural activation patterns during cognitively demanding tasks.

Figure 9 presents the similarity scores between the EEG microstates identified in Walia et al. [59] and those from Brechet et al. [58]. Similarity was quantified using Pearson correlation coefficients and Mean Squared Error (MSE) values. Higher Pearson coefficients and lower MSE values indicate stronger alignment between corresponding microstate topographies. The comparative analysis revealed several notable correspondences. In cases of one-to-many mappings, selection was guided by neurophysiological correlates described in both Walia et al. [59] and Brechet et al. [58].

Microstate 1 from Walia et al. aligns with a combination of Microstates A and C from Brechet et al., all showing an anterior-posterior gradient, albeit with slight differences in polarity and intensity.

Microstate 2 corresponds to a mix of Microstates A and B, characterized by lateralized brain activity.

Microstate 3 maps onto both Microstates A and D, sharing central dominance, though Microstate D exhibits a narrower spatial distribution.

Microstate 4 closely aligns with Microstate E, with both showing balanced anterior-posterior symmetry; Microstate E, however, displays a slight frontal skew.

Microstates 5 and 6 correspond to a combination of Microstates E and F, both reflecting left-right asymmetries.

The functional relevance of these microstates has been extensively characterized by Tarailis et al. [63], who linked each to distinct neural networks and cognitive functions.

Microstate A is associated with left-lateralized activity in the superior temporal gyrus, medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), and occipital cortex (OC), reflecting sensory integration.

Microstate B involves strong activation in the OC and lateral/medial parietal regions, including the precuneus and retrosplenial cortex, supporting visual scene reconstruction during episodic memory recall.

Microstate C shows bilateral activation in the lateral parietal cortex (supramarginal and angular gyri), aligning with the default mode network (DMN), linked to self-referential processing and episodic memory.

Microstate D activates bilateral inferior frontal gyri, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), and superior parietal lobules/intraparietal sulci. It primarily reflects the frontoparietal network (FPN), supporting cognitive control and attentional reorientation. Notably, the dACC also overlaps with hubs of the cingulo-opercular network (CON) and the salience network (SN), which are involved in dynamic switching between the DMN and FPN [64].

Microstate E is characterized by strong right MPFC activity, associated with automatic and intuitive decision-making.

Microstate F shows bilateral MPFC activation, aligning with the anterior DMN.

These functional mappings help explain the neurophysiological underpinnings of the similarities and subtle differences observed between the microstate patterns in Walia et al. [59] and Brechet et al. [58]. They also support the idea that microstate configurations reflect stable, functionally relevant brain states tied to expertise and cognitive demand.

Figure 10 presents Kalman Filter and LQG Optimal Control framework interpretation of microstate transitions observed in expert and novice participants during the Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) task. This framework helps to conceptualize how the brain updates internal models in response to sensory feedback and prediction errors.

Microstate Transitions During the Error Epoch

In the Error Epoch, novices primarily transition from Microstate 4 (corresponding to Microstate E) to Microstate 1 (a combination of Microstates A and C). This transition likely reflects a shift from automatic/intuitive processing (Microstate E) to an Observation Model involving sensory integration (Microstate A) and the default mode network (DMN) (Microstate C). Such patterns suggest a novice-level response to task errors, wherein conscious observation and sensory recalibration dominate. In contrast, experts show a more refined transition pattern. They begin in Microstate 6, which integrates features of Microstates E and F—reflecting both intuitive decision-making (right medial prefrontal cortex, MPFC; Microstate E) and deliberate cognitive control (left MPFC; Microstate F). This bilateral MPFC activity suggests experts' ability to balance automatic and controlled processes, effectively regulating error-related arousal before transitioning to Microstate 1, the Observation Model.

Another notable transition in experts occurs from Microstate 5 (aligned with Microstate E) to Microstate 3 (a combination of Microstates A and D). Here, Microstate D represents the frontoparietal network (FPN), critical for the Correction Step [65] in Kalman Filter and LQG Optimal Control framework. Within Microstate 3, sensory integration (Microstate A) and motor planning areas such as the dorsomedial frontal cortex (DMFC)—including the supplementary motor area (SMA)—are thought to interact with the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) from Microstate D. This interaction enables the transformation of error signals into corrective motor plans. Importantly, the dACC serves as a communication hub across multiple networks: the cingulo-opercular network (CON) and the salience network (SN) [66], both of which are implicated in goal-directed behavior and prediction error signaling [67]. This makes Microstate D—involving dACC, inferior frontal gyrus, and parietal regions—ideally suited for Bayesian belief updating in response to surprising or unexpected events [68].

In the context of FLS learning, it is proposed that the CON uses inputs from the SN to detect salient events and then recruits the FPN to guide adaptive responses [69]. Therefore, in the Error Epoch, Microstates 5 and 6 (experts) and Microstate 4 (novices) are likely involved in Hidden State Transitions, enabling dynamic updating of internal models.

Microstate Dynamics During Task Initiation

During the initiation phase of the FLS task, novices exhibit frequent transitions between Microstates 1 and 3, reflecting an interplay between the DMN ("Brain as Observer") and the CON-FPN ("Brain as Controller"). This pattern aligns with the cognitive stage of skill learning [56,70], characterized by high cognitive load and conscious performance monitoring. Experts, however, predominantly transition to Microstate 3, with strong transitions from Microstates 2 and 5. Here, Microstate 2 (a hybrid of Microstates A and B) involves sensory integration (A) and episodic memory recall via the precuneus/retrosplenial cortex (B). This suggests a more autonomous, experience-driven form of Hidden State Transition, where implicit mental imagery supports the expert's control mechanisms—characteristic of an autonomous stage.

Internal Simulation Model and Task Observation

In our Internal Simulation Model for enactment imagination, we propose that mental imagery facilitates the Correction Step by enabling individuals to simulate corrective actions internally for reevaluation (subserved by SMA, LPFC, LPMC, RPFC – see

Figure 5). Here, the Observation Model reflects brain activity during first-person observation, and varies with experience [70]. Our study [70] investigated how brain activation during a cognitive surgical task—simulated operative dictation (an internal simulation task)—varies with surgical experience. Using fNIRS, we measured brain activity across prefrontal, sensorimotor, and occipital regions in junior residents, senior residents, and attending surgeons. Results showed that senior residents exhibited significantly greater activation in the left prefrontal, premotor, and parietal cortices compared to both juniors and attendings. These findings suggest that cognitive task-related brain activation patterns differ by experience level and highlight the potential of functional neuroimaging as an objective tool for assessing cognitive surgical expertise.

In this section, I applied the Kalman Filter and LQG Optimal Control framework to understand how brain activation during a cognitive-motor task varies with surgical experience, focusing on transitions between EEG microstates. During FLS task initiation, novices showed high transition variability—especially between Microstates 1 (DMN/"Brain as Observer") and 3 (FPN/SN/"Brain as Controller")—reflecting exploratory strategies typical of early learning. In contrast, experts demonstrated more efficient and focused transitions, primarily into Microstate 3 from Microstates 2 and 5, enabling controlled action through prediction error-based processing [58,59,71]. During the error correction phase, experts used targeted transitions (e.g., Microstate 5 to 3; Microstate 6 to 1), supporting internal model updates and agency evaluation [72], while novices relied on more variable transitions, reflecting less efficient adaptation. The Observation Model was supported by DMN-linked microstates (A, C), involved in self-monitoring and memory retrieval [73,74], while the Correction Step engaged the FPN, SN, and CON via Microstates D and 3, facilitating adaptive control and behavior modification [69,75,76]. Enactment imagination further distinguished skill levels [62], with experts showing localized SMA activation—critical for motor intentionality and integration across DMN, FPN, and sensorimotor systems [72,74,76,77]. Disruptions in these dynamics are observed in FMD, where abnormal beta synchronization, heightened self-focus, and impaired SN–FPN switching impair motor control [78–80].

6. Discussion

Mu and beta-gamma rhythms—linked to the "Brain as Observer" and "Brain as Controller," respectively—dynamically modulate corticospinal excitability during movement [81–84]. Their disruption in FMD may be addressed through mental imagery and external suggestions (operant conditioning) [11,85]. The cerebellum, through its connections with the MPFC and thalamocortical circuits, supports Hidden State Transitions and Correction Steps [86]. Hypnosis has been shown to influence these processes by modulating agency and prediction through cerebellar and SMA pathways [87–91], offering potential for therapeutic intervention in disorders of agency and motor control. Altered states of consciousness, such as those induced by meditation and hypnosis, modulate brain dynamics at both EEG microstates and systems levels, e.g., Brechet et al. [92] demonstrating that intense meditation training significantly reshapes EEG microstates. Two novel microstate topographies emerged post-meditation, accounting for nearly 50% of variance in EEG data. These patterns localized to brain areas involved in self-related multisensory experience, including the insula, supramarginal gyrus, and superior frontal gyrus. Notably, meditation disrupted the dominance of Microstate C—a component of the proposed Observation Model—suggesting a departure from the typically stable microstate architecture found in prior studies [93]. These findings support the hypothesis that meditation enhances self-observation, aligning with increased self-awareness reported during hypnotic states [60]. Katayama et al. [93] investigated EEG microstate changes across stages of hypnosis—resting, light, deep hypnosis, and recovery. They found that during deep hypnosis, Microstates A and C increased in duration and time coverage, while Microstates B and D decreased. This transition reflected a shift in cognitive dominance from executive control (Brain as Controller) toward self-reflective observation (Brain as Observer). Recovery stages showed intermediate characteristics, highlighting a dynamic trajectory through altered states. Importantly, Katayama’s results suggest that deep hypnosis may enhance insight by amplifying "Brain as Observer" activity while dampening "Brain as Controller" functions. Comparisons across states showed deep hypnosis shared traits with schizophrenia (e.g., impaired executive control), while light hypnosis overlapped with meditation in promoting relaxation and awareness. This observation aligns with findings by Xu et al. [94], who explored self-projection and future thinking. Participants reported higher vividness and self-projection when imagining their Future Self compared to Present Self. A functional dissociation emerged within the Default Mode Network (DMN): the anterior DMN (aDMN) was more active during Present Self reflection (Brain as Observer), while the posterior DMN (pDMN) was more active during Future Self imagery (Brain as Controller). These subsystems may be selectively modulated through internal simulation and suggestion-based techniques, particularly in therapeutic contexts like self-hypnosis [9]. Within this broader context, the Kalman Filter and LQG Optimal Control framework offers a powerful model to explain how the brain learns, corrects errors, and adapts motor skills. In my proposed model, microstate analysis and enactment imagination are used alongside multimodal brain imaging to distinguish between novice and expert skill acquisition. Novices display variable, exploratory neural pathways, while experts show streamlined, efficient transitions across the Frontoparietal Network (FPN), DMN, and Salience Network (SN). Here, the SMA plays a central integrative role, transforming internal motor intentions into precise executions, informed by external feedback. For example, a steady decline in the strength of directed functional connectivity from the lateral prefrontal cortex to the SMA over the course of a 15-day training period was found [70]. During the initial "Cognitive stage" (Days 1–5), connectivity was high, reflecting strong top-down control from the LPFC as participants engage in conscious, effortful learning. As training progresses into the "Associative stage" (Days 6–15), this connectivity gradually decreases, indicating reduced reliance on executive control and increased motor automation. By the retention phase, the LPFC→SMA influence remains low, suggesting that the skill has become internalized and more efficiently executed. This shift reflects the brain’s transition from effortful to automatic processing, a hallmark of sensorimotor learning. However, in FMD, this process breaks down—disrupted agency and impaired SMA signaling interfere with adaptive motor control [42]. The review of Kalman Filter and LQG Optimal Control framework revealed how internal simulations, and external suggestions can be harnessed to recalibrate these pathways and restore voluntary control.

While Kalman Filter and LQG Optimal Control framework remain central to understanding agency in this review, several models offered complementary insights, e.g., Forward and Comparator Models explain agency through motor command prediction and sensory feedback comparison [95]. The Comparator Model posits that agency arises when predicted outcomes match actual feedback [96]. Then, Free Energy Principle [5] extended predictive coding by proposing the brain minimizes surprise (free energy) to maintain equilibrium. The sense of agency arises from successful prediction-action alignment. Embodied Cognition and Enactivism models [97–99] argue that agency emerges through real-time interaction with the environment—not internal models alone, i.e., agency is enacted, not inferred. Dynamical Systems Theory model describes behavior as the emergent product of a self-organizing, multicomponent system evolving over time [100] which has been applied to understand human behavior, suggesting that agency arises from the self-organization of neural dynamics [101]. Ecological psychology [102], grounded in the work of James and Eleanor Gibson, offers a non-representational, action-oriented framework for perception and cognition—emphasizing the direct perception of affordances in the environment through dynamic agent-environment interactions.

Across neuroimaging studies, regions like the SMA, parietal cortex (IPL/TPJ), cerebellum, and prefrontal cortex (PFC) emerge as central hubs for generating, monitoring, and attributing agency. Structural connectivity between SMA/pre-SMA and parietal cortex via the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), particularly its branches (SLF I and SLF II), further supports such integrated brain functions [103], motor intentionality [104], and sense of agency [105,106]. Our studies [56,107,108] suggested that neuroimaging-guided transcranial electrical stimulation (tES) could enhance skill learning by targeting specific brain network interactions. For instance, stimulation of AG-MFG (angular gyrus–middle frontal gyrus) connections, linked via the dorsal SLF II, may enhance the sense of agency. Similarly, targeting the SMG-IFG (supramarginal gyrus–inferior frontal gyrus) via SLF III may support perception in complex tasks. In experts, the preSMA–LPFC coupling, supported by the extended frontal aslant tract (exFAT), may underlie sequence learning and executive control in familiar tasks. Overall, tES may boost predictive internal modeling and efference signaling, aiding motor learning and rehabilitation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org,

Figure 3 Matlab simulation code: figure3.m.

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s2,

Figure 4 Matlab simulation code: figure4.m.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition: Anirban Dutta. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding to Anirban Dutta from EPSRC Rehabtech+ (https://www.rehabtechnologies.net/).

Data Availability Statement

The MATLAB code used for the simulations in this paper is provided in the supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the co-design team—Katerina Hatjipanagioti, Matthew Newsham, Lewis Leyland, Lindsey Rickson, Alastair Buchanan, Ildar Farkhatdinov, Jacqueline Twamley, and Abhijit Das—for their invaluable contributions to the development of the XR rehabilitation platform technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SoA |

Sense of Agency |

| HMI |

Human–Machine Interface |

| XR |

eXtended Reality |

| VR |

Virtual Reality |

| FND |

Functional Neurological Disorder |

| EPH |

Equilibrium Point Hypothesis |

| fMRI |

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ERP |

Event-Related Potential |

| DTI |

Diffusion Tensor Imaging |

| SMA |

Supplementary Motor Area |

| M1 |

Primary Motor Cortex |

| PFC |

Prefrontal Cortex |

| IPL |

Inferior Parietal Lobule |

| TPJ |

Temporoparietal Junction |

| DMN |

Default Mode Network |

| FPN |

Frontoparietal Network |

| CON |

Cingulo-Opercular Network |

| SN |

Salience Network |

| aDMN |

Anterior Default Mode Network |

| pDMN |

Posterior Default Mode Network |

| LQG |

Linear-Quadratic-Gaussian |

| DT |

Dynamical Systems Theory |

| tES |

Transcranial Electrical Stimulation |

| AG |

Angular Gyrus |

| MFG |

Middle Frontal Gyrus |

| SMG |

Supramarginal Gyrus |

| IFG |

Inferior Frontal Gyrus |

| LPFC |

Left Prefrontal Cortex |

| RPFC |

Right Prefrontal Cortex |

| LPMC |

Left Premotor Cortex |

| exFAT |

Extended Frontal Aslant Tract |

| fNIRS |

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| MS |

Microstate |

| PPIE |

Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement |

| CFR |

Counterfactual Regret Minimization |

| GLM |

General Linear Model |

| GEV |

Global Explained Variance |

| HRX-1 |

Haptic Rehabilitation eXtended robot 1 (HumanRobotix London) |

| BOLD |

Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (implied in neuroimaging context) |

| A, B, C, D, E, F, C′ |

EEG Microstate Classes |

References

- Caspar, E.A.; De Beir, A.; Lauwers, G.; Cleeremans, A.; Vanderborght, B. How Using Brain-Machine Interfaces Influences the Human Sense of Agency. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0245191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelio, P.; Haggard, P.; Hornbaek, K.; Georgiou, O.; Bergström, J.; Subramanian, S.; Obrist, M. The Sense of Agency in Emerging Technologies for Human–Computer Integration: A Review. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. Prediction, Perception and Agency. Int J Psychophysiol 2012, 83, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxenham, A.J. Helmholtz. J Clin Invest 2011, 121, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. The Free-Energy Principle: A Unified Brain Theory? Nat Rev Neurosci 2010, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T. Evaluating the Bayesian Causal Inference Model of Intentional Binding through Computational Modeling. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitchison, L.; Lengyel, M. With or without You: Predictive Coding and Bayesian Inference in the Brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2017, 46, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.A.; Shipp, S.; Friston, K.J. Predictions Not Commands: Active Inference in the Motor System. Brain Struct Funct 2013, 218, 611–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A. Bayesian Predictive Coding Hypothesis: Brain as Observer’s Key Role in Insight. Medical Hypotheses 2025, 195, 111546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.J.; Adams, R.A.; Brown, H.; Pareés, I.; Friston, K.J. A Bayesian Account of “Hysteria. ” Brain 2012, 135, 3495–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Das, A. A Platform Technology for VR Biofeedback Training under Operant Conditioning for Functional Lower Limb Weakness 2024.

- Voss, M.; Chambon, V.; Wenke, D.; Kühn, S.; Haggard, P. In and out of Control: Brain Mechanisms Linking Fluency of Action Selection to Self-Agency in Patients with Schizophrenia. Brain 2017, 140, 2226–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidarus, N.; Chambon, V.; Haggard, P. Priming of Actions Increases Sense of Control over Unexpected Outcomes. Conscious Cogn 2013, 22, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A. ‘Hyperbinding’ in Functional Movement Disorders: Role of Supplementary Motor Area Efferent Signalling. Brain Communications 2025, 7, fcae464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Hatjipanagioti, K.; Newsham, M.; Leyland, L.; Rickson, L.; Buchanan, A.; Farkhatdinov, I.; Twamley, J.; Das, A. Co-Production of a Platform Neurotechnology for XR Biofeedback Training for Functional Upper Limb Weakness (Preprint) 2024.

- Körding, K.P.; Wolpert, D.M. Bayesian Decision Theory in Sensorimotor Control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2006, 10, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körding, K. Decision Theory: What “Should” the Nervous System Do? Science 2007, 318, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körding, K.P.; Wolpert, D.M. Bayesian Integration in Sensorimotor Learning. Nature 2004, 427, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genewein, T.; Braun, D.A. Occam’s Razor in Sensorimotor Learning. Proc Biol Sci 2014, 281, 20132952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, T.; Lombrozo, T.; Nichols, S. Bayesian Occam’s Razor Is a Razor of the People. Cogn Sci 2018, 42, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; Schwartenbeck, P.; FitzGerald, T.; Moutoussis, M.; Behrens, T.; Dolan, R.J. The Anatomy of Choice: Active Inference and Agency. Front Hum Neurosci 2013, 7, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.G. Origin and Advances of the Equilibrium-Point Hypothesis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2009, 629, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latash, M.L. Evolution of Motor Control: From Reflexes and Motor Programs to the Equilibrium-Point Hypothesis. J Hum Kinet 2008, 19, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, N.; Crago, P.E. Equilibrium-Point Hypothesis, Minimum Effort Control Strategy and the Triphasic Muscle Activation Pattern. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1992, 15, 769–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latash, M.L.; Gutman, S.R. Abnormal Motor Patterns in the Framework of the Equilibrium-Point Hypothesis: A Cause for Dystonic Movements? Biol Cybern 1994, 71, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltieri, M.; Buckley, C. On Kalman-Bucy Filters, Linear Quadratic Control and Active Inference. arXiv: Neurons and Cognition 2020.

- Kumar, D.; Sinha, N.; Dutta, A.; Lahiri, U. Virtual Reality-Based Balance Training System Augmented with Operant Conditioning Paradigm. BioMedical Engineering OnLine 2019, 18, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. On the General Theory of Control Systems. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 1960, 1, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Co-Design and Usability Evaluation of an Extended Reality Biofeedback Platform for Functional Upper Limb Weakness. Available online: https://preprints.jmir.org/preprint/68580 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Gilmour, G.S.; Nielsen, G.; Teodoro, T.; Yogarajah, M.; Coebergh, J.A.; Dilley, M.D.; Martino, D.; Edwards, M.J. Management of Functional Neurological Disorder. Journal of Neurology 2020, 267, 2164–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Lahiri, U.; Das, A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Guiraud, D. Post-Stroke Balance Rehabilitation under Multi-Level Electrotherapy: A Conceptual Review. Front Neurosci 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Hatjipanagioti, K.; Newsham, M.; Leyland, L.; Rickson, L.; Buchanan, A.; Farkhatdinov, I.; Twamley, J.; Das, A. Co-Design and Usability Evaluation of an Extended Reality Biofeedback Platform for Functional Upper Limb Weakness. JMIR XR and Spatial Computing (JMXR) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athans, M. The Role and Use of the Stochastic Linear-Quadratic-Gaussian Problem in Control System Design. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1971, 16, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, E.; Li, W. A Generalized Iterative LQG Method for Locally-Optimal Feedback Control of Constrained Nonlinear Stochastic Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2005, American Control Conference, 2005.; June 2005; pp. 300–306 vol. 1.

- Maceira-Elvira, P.; Timmermann, J.E.; Popa, T.; Schmid, A.-C.; Krakauer, J.W.; Morishita, T.; Wessel, M.J.; Hummel, F.C. Dissecting Motor Skill Acquisition: Spatial Coordinates Take Precedence. Science Advances 2022, 8, eabo3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Grèzes, J. The Power of Simulation: Imagining One’s Own and Other’s Behavior. Brain Res 2006, 1079, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, D.A.; Halligan, P.W. Hypnotic Suggestion: Opportunities for Cognitive Neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apelian, C.; De Vignemont, F.; Terhune, D.B. Comparative Effects of Hypnotic Suggestion and Imagery Instruction on Bodily Awareness. Consciousness and Cognition 2023, 108, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, G.R.; Barabasz, A.F.; Council, J.R.; Spiegel, D. Advancing Research and Practice: The Revised APA Division 30 Definition of Hypnosis. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2015, 63, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankozi, C. Imagination, Ecologized and Enacted: Driven by the Historicity of Affordance Competition. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platform Technology for VR Biofeedback Training under Operant Conditioning for Functional Limb Weakness: A Proposal for Co-Production of At-Home Solution (REACT2HOME). Available online: https://preprints.jmir.org/preprint/70620 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Dutta, A. ‘Hyperbinding’ in Functional Movement Disorders: Role of Supplementary Motor Area Efferent Signalling. Brain Communications 2025, 7, fcae464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimbert, S.; Zaepffel, M.; Riff, P.; Adam, P.; Bougrain, L. Hypnotic State Modulates Sensorimotor Beta Rhythms During Real Movement and Motor Imagery. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takarada, Y.; Nozaki, D. Hypnotic Suggestion Alters the State of the Motor Cortex. Neurosci Res 2014, 85, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, P.; Modenese, M.; Benedetti, S.; Emadi Andani, M.; Fiorio, M. Hypnosis-Induced Modulation of Corticospinal Excitability during Motor Imagery. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 16882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, R.; Raseta, M.; Natarajan, I.; Roffe, C. The Use of Hypnotherapy as Treatment for Functional Stroke: A Case Series from a Single Center in the UK. Int J Stroke 2022, 17, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, D.A.; Halligan, P.W. Hypnotic Suggestion: Opportunities for Cognitive Neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareés, I.; Brown, H.; Nuruki, A.; Adams, R.A.; Davare, M.; Bhatia, K.P.; Friston, K.; Edwards, M.J. Loss of Sensory Attenuation in Patients with Functional (Psychogenic) Movement Disorders. Brain 2014, 137, 2916–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espay, A.J.; Aybek, S.; Carson, A.; Edwards, M.J.; Goldstein, L.H.; Hallett, M.; LaFaver, K.; LaFrance, W.C.; Lang, A.E.; Nicholson, T.; et al. Current Concepts in Diagnosis and Treatment of Functional Neurological Disorders. JAMA Neurol 2018, 75, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. Causal Inference. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Workshop on Causality: Objectives and Assessment at NIPS 2008.

- Frith, C. Explaining Delusions of Control: The Comparator Model 20 Years On. Conscious Cogn 2012, 21, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, T.; Pezzulo, G.; Friston, K.J. Active Inference: The Free Energy Principle in Mind, Brain, and Behavior; The MIT Press, 2022; ISBN 978-0-262-36997-8.

- Zinkevich, M.; Johanson, M.; Bowling, M.; Piccione, C. Regret Minimization in Games with Incomplete Information. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, December 3, 2007; pp. 1729–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Synofzik, M.; Vosgerau, G.; Newen, A. Beyond the Comparator Model: A Multifactorial Two-Step Account of Agency. Consciousness and Cognition 2008, 17, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, P.R.; Aitken, M.R.F.; Dickinson, A.; Shanks, D.R.; Honey, G.D.; Honey, R.A.E.; Robbins, T.W.; Bullmore, E.T.; Fletcher, P.C. Prediction Error during Retrospective Revaluation of Causal Associations in Humans: fMRI Evidence in Favor of an Associative Model of Learning. Neuron 2004, 44, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, A.; Makled, B.; Norfleet, J.; Schwaitzberg, S.D.; Intes, X.; De, S.; Dutta, A. Directed Information Flow during Laparoscopic Surgical Skill Acquisition Dissociated Skill Level and Medical Simulation Technology. npj Sci. Learn. 2022, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.A.; Roth, A.E. The Nash Equilibrium: A Perspective. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 3999–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bréchet, L.; Brunet, D.; Birot, G.; Gruetter, R.; Michel, C.M.; Jorge, J. Capturing the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Self-Generated, Task-Initiated Thoughts with EEG and fMRI. Neuroimage 2019, 194, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, P.; Fu, Y.; Norfleet, J.; Schwaitzberg, S.D.; Intes, X.; De, S.; Cavuoto, L.; Dutta, A. Error-Related Brain State Analysis Using Electroencephalography in Conjunction with Functional near-Infrared Spectroscopy during a Complex Surgical Motor Task. Brain Inform 2022, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, C.M.; Koenig, T. EEG Microstates as a Tool for Studying the Temporal Dynamics of Whole-Brain Neuronal Networks: A Review. NeuroImage 2018, 180, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bek, J.; O’Farrell, R.; Cooney, S.M. Experience in Sports and Music Influences Motor Imagery: Insights from Implicit and Explicit Measures. Acta Psychologica 2025, 252, 104650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Huillier, J.C.; Jones, C.B.; Fu, Y.; Myneni, A.A.; De, S.; Cavuoto, L.; Dutta, A.; Stefanski, M.; Cooper, C.A.; Schwaitzberg, S.D. On the Journey to Measure Cognitive Expertise: What Can Functional Imaging Tell Us? Surgery 2025, 181, 109145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarailis, P.; Koenig, T.; Michel, C.M.; Griškova-Bulanova, I. The Functional Aspects of Resting EEG Microstates: A Systematic Review. Brain Topogr 2024, 37, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulden, N.; Khusnulina, A.; Davis, N.J.; Bracewell, R.M.; Bokde, A.L.; McNulty, J.P.; Mullins, P.G. The Salience Network Is Responsible for Switching between the Default Mode Network and the Central Executive Network: Replication from DCM. Neuroimage 2014, 99, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.S.; Braver, T.S.; Barch, D.M.; Botvinick, M.M.; Noll, D.; Cohen, J.D. Anterior Cingulate Cortex, Error Detection, and the Online Monitoring of Performance. Science 1998, 280, 747–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaghiani, S.; D’Esposito, M. Functional Characterization of the Cingulo-Opercular Network in the Maintenance of Tonic Alertness. Cereb Cortex 2015, 25, 2763–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clairis, N.; Lopez-Persem, A. Debates on the Dorsomedial Prefrontal/Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex: Insights for Future Research. Brain 2023, 146, 4826–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visalli, A.; Capizzi, M.; Ambrosini, E.; Kopp, B.; Vallesi, A. Electroencephalographic Correlates of Temporal Bayesian Belief Updating and Surprise. NeuroImage 2021, 231, 117867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.L.; Nee, D.E. Cingulo-Opercular Subnetworks Motivate Frontoparietal Subnetworks during Distinct Cognitive Control Demands. J Neurosci 2023, 43, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, A.; Rahul, R.; Dutta, A.; Cavuoto, L.; Kruger, U.; Burke, H.; Hackett, M.; Norfleet, J.; Schwaitzberg, S.; De, S. Dynamic Directed Functional Connectivity as a Neural Biomarker for Objective Motor Skill Assessment 2025.

- Möhring, L.; Gläscher, J. Prediction Errors Drive Dynamic Changes in Neural Patterns That Guide Behavior. Cell Reports 2023, 42, 112931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghier, M.L. The Angular Gyrus. Neuroscientist 2013, 19, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggard, P. Sense of Agency in the Human Brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalighinejad, N.; Haggard, P. Modulating Human Sense of Agency with Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation. Cortex 2015, 69, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clairis, N.; Barakat, A.; Brochard, J.; Xin, L.; Sandi, C. A Neurometabolic Mechanism Involving dmPFC/dACC Lactate in Physical Effort-Based Decision-Making. Mol Psychiatry 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; Brass, M.; Haggard, P. Feeling in Control: Neural Correlates of Experience of Agency. Cortex 2013, 49, 1935–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Waugh, R.; Wu, T.; Panyakaew, P.; Mente, K.; Urbano, D.; Hallett, M.; Horovitz, S.G. Role of Supplementary Motor Area in Cervical Dystonia and Sensory Tricks. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 21206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastötter, B.; Weissbach, A.; Takacs, A.; Moyé, J.; Verrel, J.; Chwolka, F.; Friedrich, J.; Paulus, T.; Zittel, S.; Bäumer, T.; et al. Increased Beta Synchronization Underlies Perception-Action Hyperbinding in Functional Movement Disorders. Brain Communications 2024, 6, fcae301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, M. Functional Neurologic Disorder, La Lésion Dynamique. Neurology 2024, 103, e210051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, T.; Meppelink, A.M.; Little, S.; Grant, R.; Nielsen, G.; Macerollo, A.; Pareés, I.; Edwards, M.J. Abnormal Beta Power Is a Hallmark of Explicit Movement Control in Functional Movement Disorders. Neurology 2018, 90, e247–e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.J.; Miner, L.A.; Vaughan, T.M.; Wolpaw, J.R. Mu and Beta Rhythm Topographies during Motor Imagery and Actual Movements. Brain Topogr 2000, 12, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wischnewski, M.; Haigh, Z.J.; Shirinpour, S.; Alekseichuk, I.; Opitz, A. The Phase of Sensorimotor Mu and Beta Oscillations Has the Opposite Effect on Corticospinal Excitability. Brain Stimulation 2022, 15, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zito, G.A.; de Sousa Ribeiro, R.; Kamal, E.; Ledergerber, D.; Imbach, L.; Polania, R. Self-Modulation of the Sense of Agency via Neurofeedback Enhances Sensory-Guided Behavioral Control. Cerebral Cortex 2023, 33, 11447–11455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, A.K.; Fries, P. Beta-Band Oscillations--Signalling the Status Quo? Curr Opin Neurobiol 2010, 20, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, J.S.; Li, C.R. A Cerebellar Thalamic Cortical Circuit for Error-Related Cognitive Control. Neuroimage 2011, 54, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.-J.; Oakley, D.A.; Frith, C.D. Delusions of Alien Control in the Normal Brain. Neuropsychologia 2003, 41, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Frith, C.D.; Wolpert, D.M. The Cerebellum Is Involved in Predicting the Sensory Consequences of Action. Neuroreport 2001, 12, 1879–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsikadze, G.; Rezaee, Z.; Chang, D.-I.; Gerwig, M.; Herlitze, S.; Dutta, A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Timmann, D. Effects of Cerebellar Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Cerebellar-Brain Inhibition in Humans: A Systematic Evaluation. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation 2019, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Z.; Dutta, A. A Computational Pipeline to Optimize Lobule-Specific Electric Field Distribution during Cerebellar Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, V.; Barnier, A.J.; Woody, E.Z. Developing the Sense of Agency Rating Scale (SOARS): An Empirical Measure of Agency Disruption in Hypnosis. Conscious Cogn 2013, 22, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bréchet, L.; Ziegler, D.A.; Simon, A.J.; Brunet, D.; Gazzaley, A.; Michel, C.M. Reconfiguration of Electroencephalography Microstate Networks after Breath-Focused, Digital Meditation Training. Brain Connect 2021, 11, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, R.; Bharath, R.D.; Upadhyay, N.; Mangalore, S.; Chennu, S.; Rao, S.L. Temporal Dynamics of the Default Mode Network Characterize Meditation-Induced Alterations in Consciousness. Front Hum Neurosci 2016, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, H.; Gianotti, L.R.R.; Isotani, T.; Faber, P.L.; Sasada, K.; Kinoshita, T.; Lehmann, D. Classes of Multichannel EEG Microstates in Light and Deep Hypnotic Conditions. Brain Topogr 2007, 20, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Yuan, H.; Lei, X. Activation and Connectivity within the Default Mode Network Contribute Independently to Future-Oriented Thought. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 21001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.M.; Kawato, M. Multiple Paired Forward and Inverse Models for Motor Control. Neural Netw 1998, 11, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, C.D.; Blakemore, S.J.; Wolpert, D.M. Abnormalities in the Awareness and Control of Action. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2000, 355, 1771–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. Six Views of Embodied Cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2002, 9, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F.J.; Rosch, E.; Thompson, E. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience; The MIT Press, 1991; ISBN 978-0-262-28547-6.

- O’Regan, J.K.; Noë, A. A Sensorimotor Account of Vision and Visual Consciousness. Behav Brain Sci 2001, 24, 939–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Dynamic Systems Approach to the Development of Cognition and Action Available online:. Available online: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262200950/a-dynamic-systems-approach-to-the-development-of-cognition-and-action/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Kelso, J.A.S.; Schöner, G. Self-Organization of Coordinative Movement Patterns. Human Movement Science 1988, 7, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, L.; Heras-Escribano, M.; Travieso, D. The History and Philosophy of Ecological Psychology. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]