Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

28 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

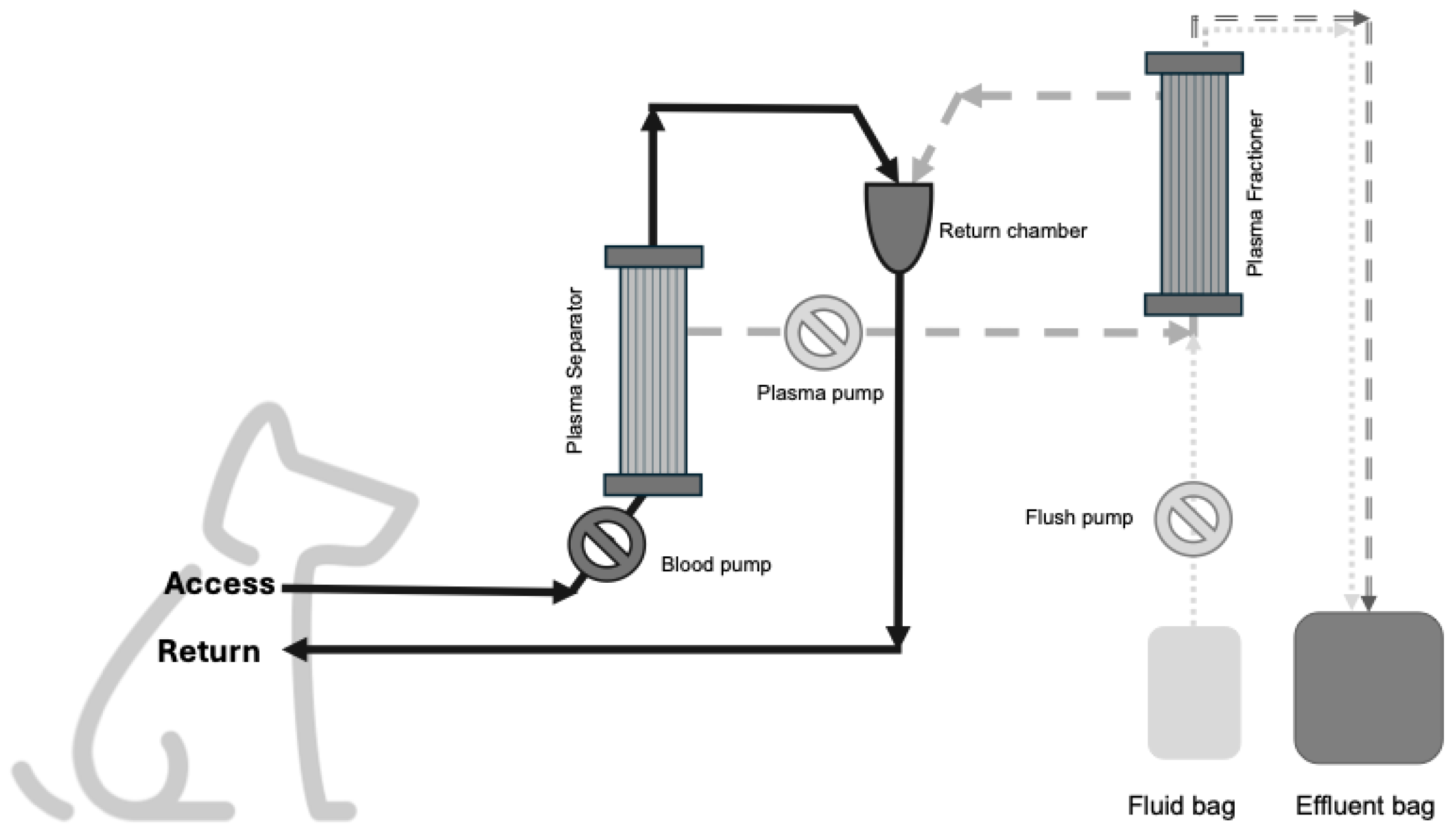

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ex-Vivo Study

2.2. Clinical Cases

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

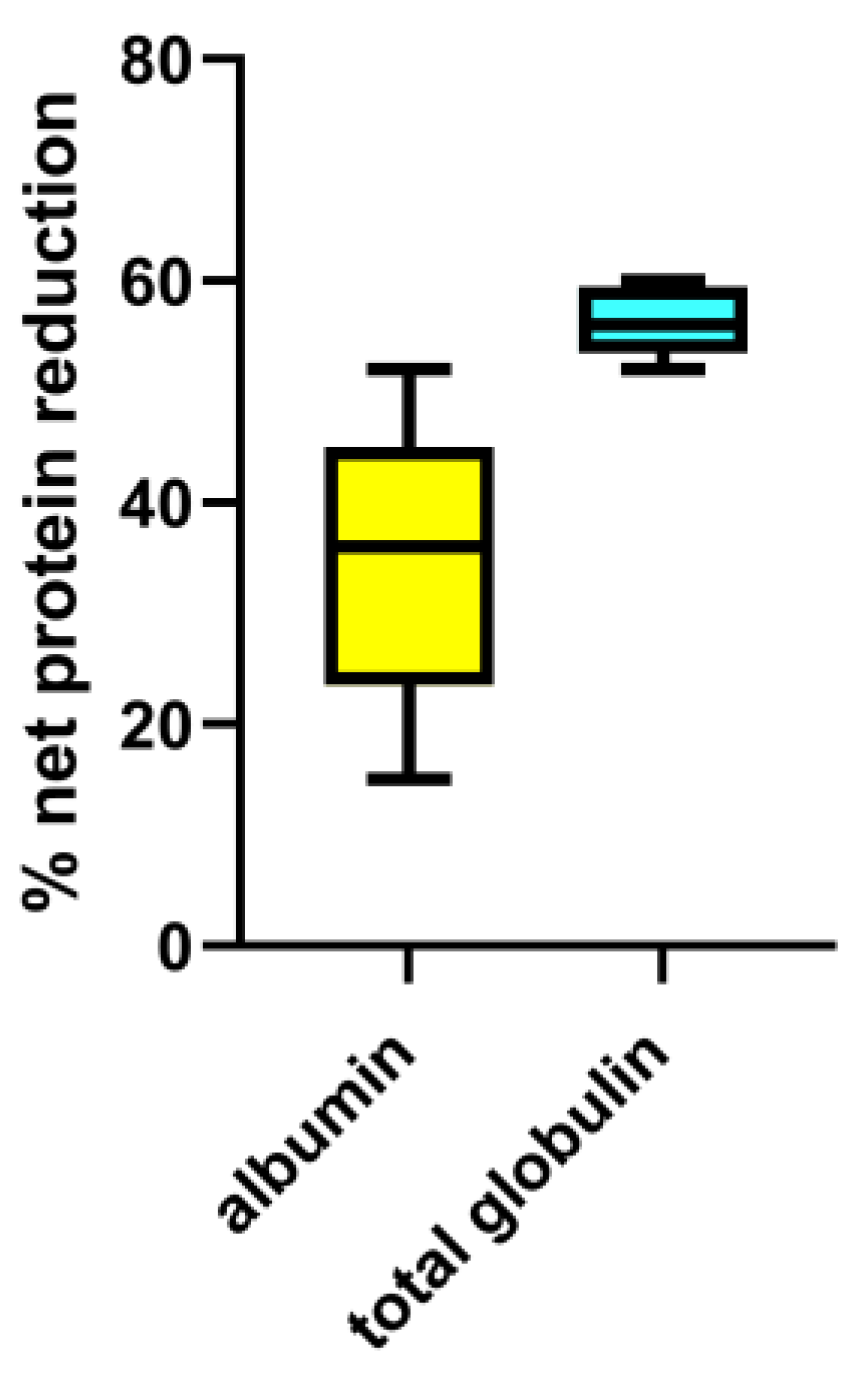

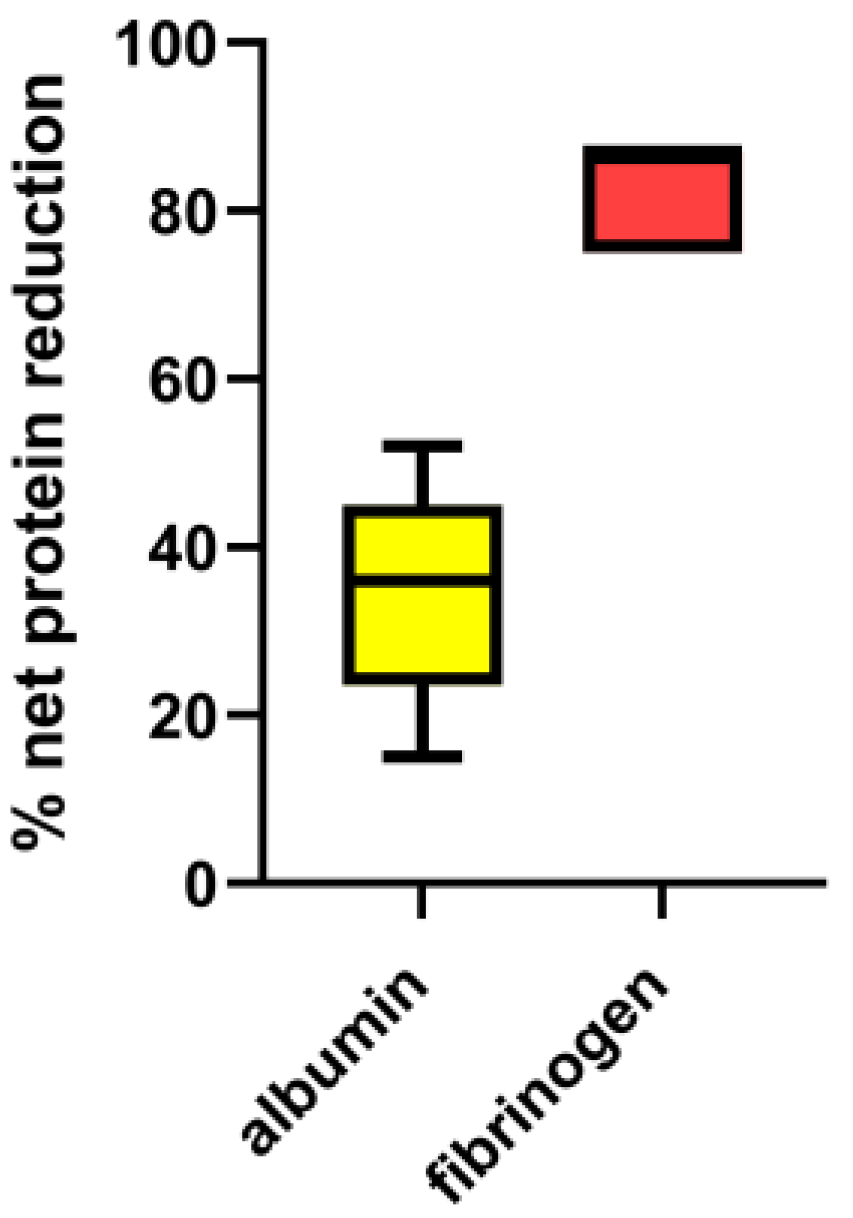

3.1. Ex-Vivo Study

3.2. In-Vivo Clinical Treatments

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DFPP | Double filtration plasmapheresis |

| PV | Plasma volumes |

References

- Perondi, F.; Brovida, C.; Ceccherini, G.; Guidi, G.; Lippi, I. Double filtration plasmapheresis in the treatment of hyperprotinemia in dogs affected by Leishmania infantum. J Vet Sci. 2018, 19, 472-476. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yeh, J.;Le, C.; Chiu, H. Clearance of Fibrinogen and von Willebrand Factor in Serial Double-Filtration Plasmapheresis. J Clin Apher. 2003, 18, 67-70. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, R.; Namazuda, K.; Hirata, N. Double filtration plasmapheresis: Review of current clinical applications. Ther Apher Dial. 2021, 25, 145-151. [CrossRef]

- Scholkmann, F.; Tsenkova, R. Changes in Water Properties in Human Tissue after Double Filtration Plasmapheresis—A Case Study. Molecules 2022, 27:3947. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Takov, K.; Straube, R. et al. Precision medicine approach for cardiometabolic risk factors in therapeutic apheresis. Horm Metab Res. 2022, 54, 238-249. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.S.; Huang, T.; Lin, Y.C. et al. The effects of double-filtration plasmapheresis on coagulation profiles and the risk of bleeding. J Formos Med Assoc. 2024, 123, 899-903. [CrossRef]

- Jagdish, K.; Jacob, S.; Varughese, S. et al. Effect of Double Filtration Plasmapheresis on Various Plasma Components and Patient Safety: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Indian J Nephrol. 2017, 27, 377-383. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, A. et al. Proteomic analysis of the rest filtered protein after double filtration plasmapheresis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2018, 11, 9715-9721.

- Daga Ruiz, D.; Fonseca San Miguel, F.; Gonzàles de Molina, F.J. et al. Plasmapheresis and other extracorporeal filtration techniques in critical patients. Med Intensiva 2017, 41, 174-187.

- Kolesnyk, M.O., Lapchyns’ka, I.; Dudar, O.; Velychko, M.B. The effect of therapeutic plasmapheresis on the hemostatic system of patients with chronic glomerulonephritis and the nephrotic syndrome. Lik Sprava 1993, 2, 79-81.

- Marlu, R.; Bennani, H.N.; Seyve, L. et al. Comparison of three modalities of plasmapheresis on coagulation: Centrifugal, single-membrane filtration, and double-filtration plasmapheresis. J Clin Apher 2021, 36, 408-419. [CrossRef]

- Noiri, E.; Hanafusa, N. The concise manual of apheresis therapy. Springer, Japan, 2014; pp. 141- 152.

| PV processed | Total proteins (g/l) | Albumin (g/l) | Total globulins (g/l) | γ-globulins (g/l) | Fibrinogen (g/l) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RB | EF | RB | EF | RB | EF | RB | EF | RB | EF | |

| Baseline | 38 | n.a. | 23.2 | n.a. | 14.5 | n.a. | 1.9 | n.a. | 1.3 | n.a. |

| 1.5 PV | 16 | 79 | 11.2 | 38.6 | 5.2 | 40.3 | 0.7 | 6.2 | < 0.4 | 1.1 |

| 2 PV | 11 | 61 | 7.5 | 33.3 | 3.8 | 27.6 | 0.5 | 4.3 | < 0.4 | 1.5 |

| 3 PV | 9 | 44 | 5.6 | 25.2 | 3.1 | 18.4 | 0.5 | 3.0 | <0.4 | 1.0 |

| PV processed | α1-globulin (g/l) | α2-globulin (g/l) | β1-globulin (g/l) | β2-globulin (g/l) | γ-globulin (g/l) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RB | EF | RB | EF | RB | EF | RB | EF | RB | EF | |

| Baseline | 1.7 | n.a. | 4.4 | n.a. | 2.8 | n.a. | 3.7 | n.a. | 1.9 | n.a. |

| 1.5 PV | 0.9 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 15.8 | 1.0 | 7.0 | 1.3 | 8.8 | 0.7 | 6.2 |

| 2 PV | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 10.1 | 1.0 | 4.7 | 0.8 | 6.1 | 0.5 | 4.3 |

| 3 PV | 0.4 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 6.1 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 4.4 | 0.5 | 3.0 |

| PV processed | Total protein | Net protein loss (%) | Total albumin | Net albumin loss (%) | Total globulin | Net total globulin loss (%) | γ-globulin | Net γ-globulin loss (%) | Fibrinogen | Net fibrinogen loss (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RB | EF | RB | EB | RB | EB | RB | EB | RB | EF | ||||||

| Baseline | 63.9 | n.a. | n.a. | 39 | n.a. | n.a. | 24.4 | n.a. | n.a. | 3.2 | n.a. | n.a. | 2.2 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 1.5 PV | n.a. | 20 | 32 | n.a. | 9.7 | 25 | n.a. | 10 | 41 | n.a. | 1.6 | 50 | n.a. | 1.1 | 14 |

| 2 PV | n.a. | 25 | 40 | n.a. | 13.7 | 35 | n.a. | 11.3 | 47 | n.a. | 1.8 | 57 | n.a. | 1.5 | 28 |

| 3 PV | n.a. | 27 | 42 | n.a. | 15.5 | 40 | n.a. | 11.3 | 47 | n.a. | 1.8 | 57 | n.a. | 1.0 | 28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).