Introduction

Schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease (NTD) is the second most serious parasitic disease in Nigeria after malaria, causing significant morbidity and mortality in the world [

1]. It is most widely spread across the world's tropical regions, mainly Sub-Saharan Africa and also in the Caribbean, South America, the Middle East, and some countries in West Asia [

2]. Globally, about 779 million people are reported to be at risk of schistosomiasis, with 207 million infected with the disease [

3]. Africa alone accounts for more than 85% of all infections and Nigeria has the greatest number of persons infected with or at risk of schistosomiasis (29 million people are infected out of which 16 million are children and around 101 million people are at risk) [

4]. Urinary Schistosomiasis caused by

S. haematobium is endemic in Nigeria with substantial transmission in most states of the federation [

5].

Furthermore, for effective control of the disease, accurate, precise, reliable, sensitive, and specific diagnostic methods are required for the accurate detection of

Schistosoma spp [

6]. This is important because decisions on treatment approach to adopt, assessment of morbidity, preventive chemotherapy, and other control actions depend on accurate estimation of the disease burden and intensity [

7], but there are limitations to some of the diagnostic techniques [

8]. Microscopy, although rigorous and time consuming is a cheap and easy procedure and the gold standard for schistosomiasis diagnosis [

8]. It has been used widely in epidemiological studies to assess schistosomiasis burden in many endemic settings but its inadequate sensitivity and dependence on the timing of sample collection especially with low-intensity infections often leads to sub-optimal results [

9]. Anti-body assays on the other hand are sensitive but are unable to differentiate history of exposure from active infection and are not easy to carry out under field conditions while antigen-based assays have been found applicable under field conditions but are less sensitive for

S. haematobium infections [

9]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based techniques because of their high sensitivity and specificity have been effectively used to detect many parasitic DNA including

S. haematobium [

9,

10,

11]. Advancements in DNA isolation procedures and PCR technology especially real-time PCR makes DNA amplification a credible alternative to urine microscopy [

11]. This study therefore assessed the prevalence of

S. haematobium in Otamokun, Nigeria using PCR assay to detect DNA of

S. haematobium after urine microscopy was carried out.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A community-based cross-sectional design was conducted between July and September 2023 in Otamokun, Ogo-Oluwa local government area (LGA) to detect S. haematobium eggs and DNA in the urine samples of school-age children (SAC).

Study Setting and Study Population

Ogo-Oluwa local government area (LGA), Oyo State in South-west Nigeria was purposively chosen for the study because it was one of the four LGAs reported to have a moderate prevalence of schistosomiasis in Oyo State during the last epidemiological mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis in Nigeria [

12]. The LGA currently has ten political wards: Ajaawa I, Ajaawa II, Ayede, Ayetoro, Idewure, Lagbedu, Iwo-Ate, Odo-oba, Opete and Otamokun. Otamokun was purposively chosen for the study because of its high schistosomiasis endemicity [

13]. Otamokun is located in the rural area of Ogo-Oluwa with geographical coordinates 7° 57' 0" North, 4° 11' 0" East [

14]. Agriculture is the major economic activity of the community inhabitants – cattle and goat farming, and food crops farming. The entire area is well drained by seasonal rivers including rivers Amuro, Igbo, and Owo and their tributaries. The Amuro River is the largest of all and it flows around the community. The rivers are used mainly for agricultural purposes including irrigation during the dry season, cattle grazing, and watering. Children also engage in recreational activities such as swimming, bathing, fishing, fetching water especially during the dry season. Otamokun has wet and dry seasons and most rains fall from March to October annually.

The last mass drug administration of praziquantel for schistosomiasis in this community was three years before the data collection. Cases were reported to the Ogo-Oluwa LGA primary health care coordinator and the Oyo State NTD coordinator and drugs were provided for the infected children according to the national guidelines for reporting and treating NTDs. School-age children aged 5- 17 years old who had stayed in the community for more than six months and had not taken any Schistosoma treatment in the six months before the study were surveyed.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

The formula n = Z

2p (1-p)/e

2 yielded an estimated total sample size of 165, where n represents the sample size, Z = 1.96 is the standard normal variate at 5% type 1 error, p = 9.5% is the expected proportion in the population based on previous study [

12] and e = 0.05 represents the absolute error or precision [

15]. A multi-stage sampling method was used to select the children. In the first stage, Ogo-Oluwa LGA, one of the four LGAs with moderate schistosomiasis endemicity in Oyo state was purposively chosen. At stage two, Otamokun ward with a high level of schistosomiasis endemicity was chosen. In the third stage, households with eligible respondents in the study community were mapped. In the fourth stage, using the list of eligible households as sampling frame, households were selected using systematic sampling and every 4

th household was selected. In the fifth stage, one child was selected per household to make up the sample size.

Data Collection Instruments and Data Collection

Relevant socio-demographic characteristics were collected from each child using a pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire. Each child produced mid-stream urine in a labeled 30ml clean dry screw cap container between 10:00-2:00 pm, the period when schistosome eggs secretion is known to be at the peak in infected individuals. Urine samples were transported in cold boxes to the laboratory at Our Lady of Apostle Catholic Hospital, Oluyoro Oke Offa, Ibadan, Nigeria. All samples positive for S. haematobium after urine microscopy were stored in a refrigerator and used for molecular assay. Written Informed consent was obtained from parents/ guardians and verbal assent was obtained from the children.

Data Management and Analysis

Microscopy: All 165 urine samples were subjected to urine microscopy. 10ml of each urine sample was centrifuged at 3000-4000 x g for about 10 minutes and the sediments were examined for S. haematobium eggs under 10x and 40x objective lenses and classified as light (1-9eggs/ 10ml sample), and moderate infections (≥10<50 eggs/10ml sample).

DNA Extraction: DNA was extracted using the modified Dellaporta procedure and the Qiagen QIAmp mini-kit (

Cat. No. / ID: 56304; Qiagen Sciences, MD). To 5ml of each urine sample, 5ml of DNA Extraction Buffer (DEB) containing proteinase K (0.05mg/ml). 20% Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate (SDS) was added and the mixture was incubated in a water bath at 65°C for 30 minutes. Tubes were allowed to cool to room temperature after which 1000µl of 7.5M Potassium Acetate was added and the solution was mixed briefly. The mixture was centrifuged at 13000rpm for 10 minutes, after which the supernatant was transferred into new, fresh autoclaved tubes. 2/3 volumes of cold Isopropanol / Isopropyl alcohol was added to the supernatant; tubes were inverted 3-5 times gently and incubated at -20°C for 1 hour after which the solution was centrifuged at 13000rpm for 10 minutes and the supernatant was discarded. 3ml of 70% ethanol was added and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 13000rpm. The supernatant was carefully discarded with the DNA pellet intact. Traces of ethanol were removed and the DNA pellets were dried at 37°C for 10-15 minutes. DNA pellets were resuspended in 100µl of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer, DNA was aliquot, and stored at -20°C for further lab analysis [

16]. The purity and concentration of the DNA was quantified using 1% Agarose Gel electrophoresis.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

A PCR targeting the Schistosoma-specific COX-1 gene sequences of

S. haematobium was done for the identification of specific

Schistosoma spp. The PCR mix was made up of 12.5µL of Taq 2X Master Mix from New England Biolabs (M0270); 1µL each of 10µM of Cytochrome Oxidase 1 gene forward (5′-TTT TTT GGT CAT CCT GAG GTG TAT-3′) and reverse primer (5′-TGA TAA TCA ATG ACC CTG CAA TAA-3′); 2µL of DNA template and then made up with 8.5µL Nuclease free water. The cycling parameters consisted of an Initial denaturation at 94

○C for 5 mins, followed by 36 cycles of denaturation at 94

○C for 30 secs, annealing at 58

○C for 30 secs, and elongation at 72

○C for 45 secs. Followed by a final elongation step at 72

○C for 7 minutes and hold temperature at 10

○C forever. The primer used has been reported to be specific for

S. haematobium to minimize the risk of undesired amplification [

9].

DNA Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

The amplified fragments were sequenced using a Genetic Analyzer 3130xl sequencer from Applied Biosystems using the manufacturer’s manual while the sequencing kit used was Big Dye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit. The amplified sequences were purified using Ethanol/EDTA/Sodium acetate precipitation. Sanger sequencing was used. Bio Edit software and Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis 11 (MEGA 11) were used for all genetic analysis. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method [

16]. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. Reference sequences were selected from the NCBI database based on the published sequences. All molecular work was done in the Bioinformatics Lab, Mokola, Ibadan, Nigeria. All the sequences from the study area have been deposited in the NCBI database (

Table 1).

Statistical analysis was carried out using version 20 of the Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS) software

Results

The mean age of the SAC surveyed was 9.81 ±2.93 years out of which 87 (52.7%) were males and two-fifths 66 (40%) were in the 9-12 age bracket. Urine Microscopy showed an overall prevalence of 7.3% (12 of 165) for S. haematobium egg in the study population with more males 7 (4.2%) than females 5 (3.0%) affected. The majority 11 (91.7%), of the infected SAC, had light infection (<10 eggs/ 10ml urine sample) and one SAC who was a male had a moderate infection. Half of the affected children were between 13 and 16 years old.

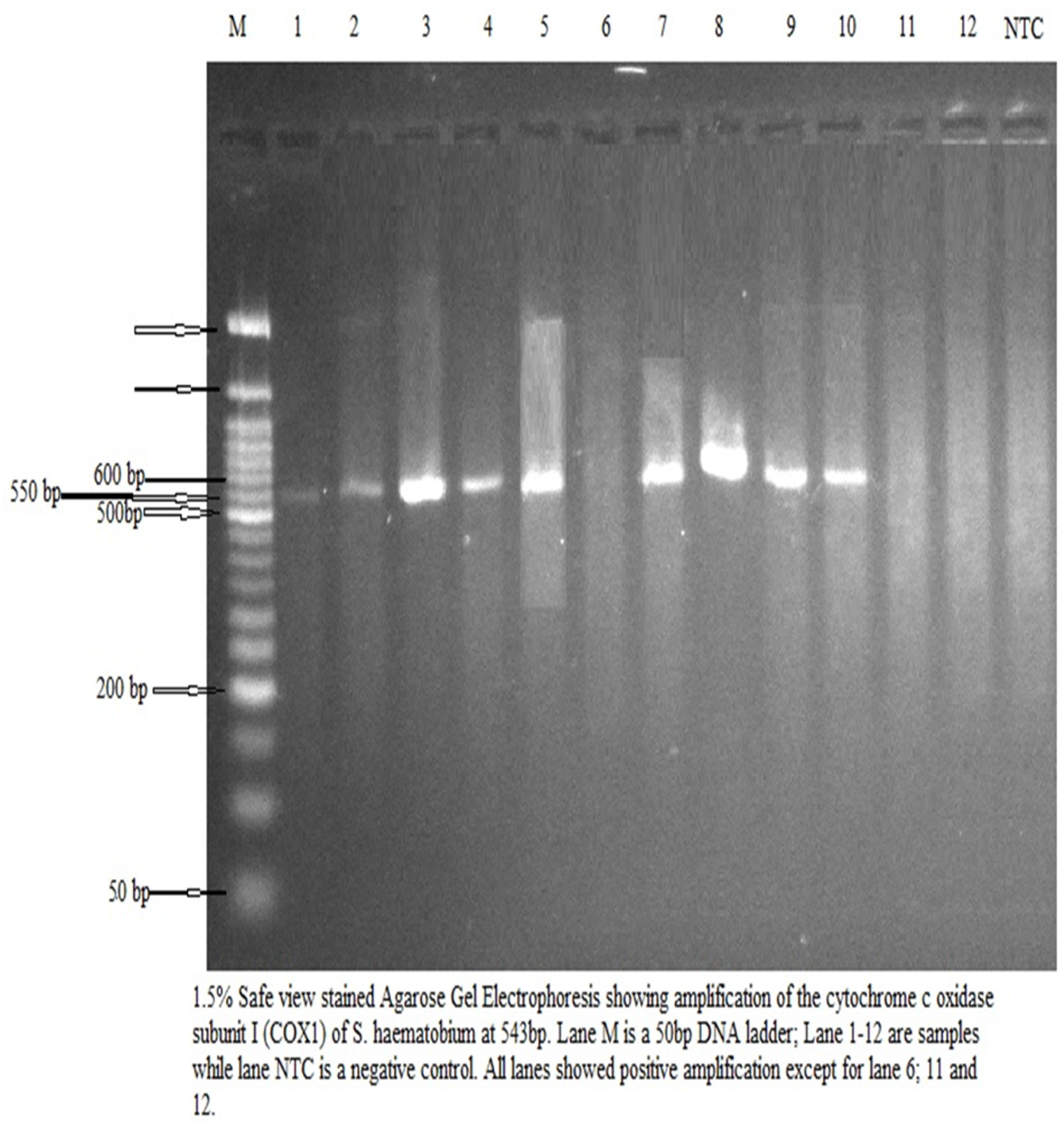

After urine microscopy, all 12 samples containing

S. haematobium eggs were assayed for

S. haematobium DNA. There was amplification in 9 of the 12 urine samples, and six of the sequences aligned with

S. haematobium in the NCBI database (

Figure 1). The three other amplified samples did not match any known organism in the NCBI database

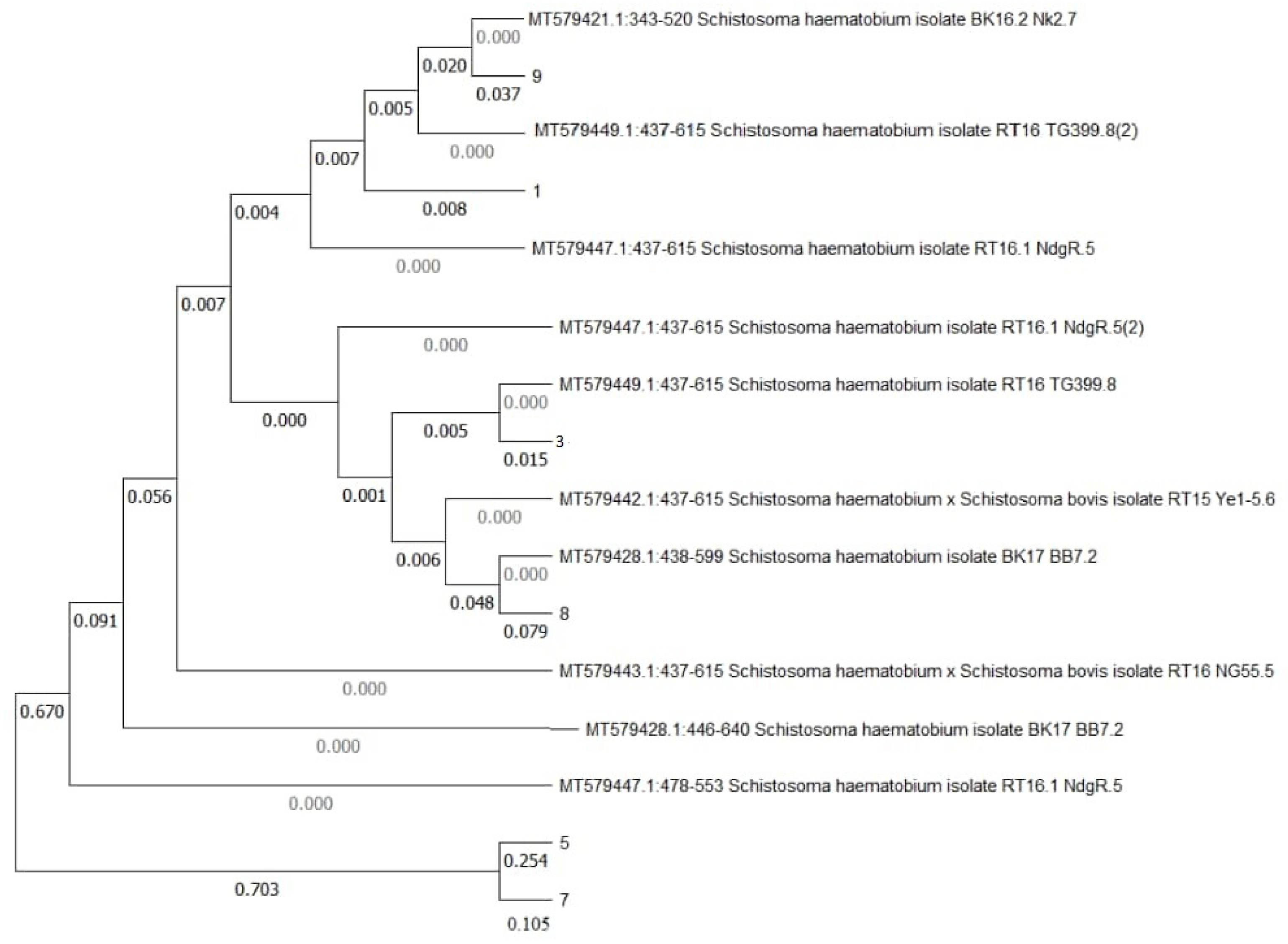

Phylogenetic Tree

The phylogenetic relationship between the isolates from the study area showed that the isolates from the study community are related to the aligned sequences from NCBI database (

Figure 2).

Isolates 5 and 7 are closely related to each other and also related to SH haplotype H4 cytochrome oxidase (MT579447.1:478-599); MT579428.1:446-640 and S. haematobium and S. bovis hybrid (MT579443.1:437-615). Isolate 8 is closely related to SH isolate (MT579428.1:438-599) and S. haematobium and S. bovis hybrid (MT579442.1:437-615). Isolate 3 is closely related to SH isolates (MT579449.1:437-615), (MT579447.1:437-615) and S. haematobium and S. bovis hybrid (MT579442.1:437-615). Isolate 1 is related to both MT579449.1:437-615 and isolate 9. Isolate 9 is also related to SH isolates (MT579421.1:343-520) and MT579449.1:437-615. All related isolates are from Northern Senegal. The branch length for the tree is 1.6711.

Discussion

This study used the mitochondrial gene (COX1) to construct a phylogenetic tree that provided insight into the molecular epidemiology of the

S. haematobium parasite from the study area. Even though the PCR assay method has been reported to be effective in detecting

S. haematobium DNA in some previous studies [

9,

10,

11], the results showed that six isolates belonged to

S. haematobium species, forming clusters with the

S. haematobium reference sequence from the NCBI database and different from other haematobium species reported in previous studies. The isolates were closely related to Schistosoma strains isolated from Northern Senegal. A similar study in Kebbi State, Nigeria, reported sequences phylogenetically closer to sequences from Kenya

[18].

Furthermore, this current study found three isolates related to hybrid species

(S. haematobium and S. bovis) in the Genebank. This suggests the possibility of hybridization of the

S. haematobium in the area at the time of study. This is similar to findings from a study in Zambia and Mali where hybrids of

S. haematobium and

S. bovis were also reported [

19,

20]. Hybridization raises the possibility of zoonotic parasite strain transmission [

21] and mostly occurs as animals and humans share the same water sources leading to an interaction between the Schistosoma species in animals and humans [

22]. Hybridization can both influence disease transmission and also alter the phenotypes of parasites in both human and animal hosts [

19]. Hybrids can affect the epidemiology and control measures for Schistosomiasis in relation to the zoonotic potential, virulence and resistance to treatment [

21]. The hybrid species found among the urine samples examined may be associated with the practice of taking cattle to the rivers for grazing and watering, as observed in the community during the data collection. The risk of cross-contamination increases when water resources are shared by humans and cattle because the water bodies contain suitable snail hosts [

23]. Although

S. haematobium infects humans, and

S. bovis infects cattle, both schistosome species use the freshwater snail of the genus Bulinus as intermediate hosts. Therefore, it is important to understand this specific snail host so that interventions can be targeted to disrupt the parasite’s life cycle [

24].

The disparity obtained between the urine microscopy and the PCR results where 9 out of the 12 DNA sequences amplified, and six were related to

S. haematobium on the NCBI database, may be due to several reasons, including: Long storage or handling conditions of the urine samples. This result is similar to a study from Spain where long-term frozen urine samples were reported not to be a good source for DNA extraction for use as a template in PCR detection of

schistosoma spp regardless of the DNA extraction method. Therefore, fresh human samples must be used for PCR assay to be effective [

17]. Another reason could be low DNA concentration, since most of the children surveyed had light infection, the number of eggs seen may be too low to yield detectable amounts of DNA [

6].

Moreover, the amplified DNA sequences that were unidentified on the NCBI database could be as a result of genetic diversity, the DNA amplified may have originated from strains of the

S. haematobium that have not been sequenced yet or submitted to the NCBI database [

25]. Besides, there may also have been cross-reactivity with related species especially because some of the isolates from the study area were related to hybrid species of

S. haematobium and

S. bovis. Cross-amplification could lead to sequences that do not align perfectly with known

S. haematobium sequences in the database [

26].

In conclusion, S. haematobium is still prevalent among school-age children in Otamokun, Oyo State, Nigeria. It is important to use fresh human urine samples for PCR assay to ensure maximum DNA yield. The Schistosoma isolated was phylogenetically identified as S. haematobium and found to be phylogenetically related to S. haematobium isolates from Northern Senegal. The relatedness of some of the isolates from the study area to hybrid species in the gene bank suggests a possible hybridization between cattle and humans in the population studied, especially because cattle rearers were observed taking cattle for grazing and watering at the riverside at the time of visit. There is a need to educate the community on the association between Schistosomiasis and contaminating the environment and water bodies with human waste, and especially the risk associated with rearing cattle around river bodies used by humans.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Taiwo Jaiyeola, Folahanmi Akinsolu and Adesola Musa; Data curation, Taiwo Jaiyeola and Tubosun Olowolafe; Formal analysis, Adesola Musa and Victoria Iwu; Methodology, Tubosun Olowolafe, and Victoria Iwu; Resources, Taiwo Jaiyeola and Victoria Iwu; Supervision, Folahanmi Akinsolu, Adesola Musa and Tubosun Olowolafe; Validation, Folahanmi Akinsolu; Writing – original draft, Taiwo Jaiyeola; Writing – review & editing, Folahanmi Akinsolu, Adesola Musa and Victoria Iwu.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

This study wishes to appreciate Prof. Oluwabukola Tosin-Adebayo for her input in reviewing the research methods.

Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Ethical Approval

The study was carried out within a larger epidemiological study estimating the prevalence and factors associated with Schistosomiasis in Oyo state, Nigeria approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Oyo State Ministry of Health with the approval number AD 13/479/44519B

References

- WHO. Schistosomiasis 2022. Accessed from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis on Jan 9, 2022.

- M.L. Nelwan. Schistosomiasis: Life Cycle, Diagnosis, and Control. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2019 Jun 22; 91:5-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oyeyemi. Schistosomiasis Control in Nigeria: Moving Round the Circle? Annals of Global Health. 86(1): 74, 2020, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Tropical Diseases – profile for mass treatment of NTDs, 2017 Neglected Tropical Diseases – profile for mass treatment of NTDs, 2017.

- Morenikeji, I.E. Eleng. Renal related disorders in concomitant Schistosoma haematobium Plasmodium falciparum infection among children in a rural community of Nigeria. B.A 9: 2016, 136–142. [CrossRef]

- B.A. Abd Elraheem, A.S Bayoumy, M.S El-Faramawy. et al. Schistosoma haematobium DNA and eggs in urine of patients from Sohag, Egypt. JoBAZ 82, 51 (2021). [CrossRef]

- H. Feldmeier, G. Poggensee, 1993. Diagnostic techniques in schistosomiasis control: a review. Acta Tropica 52: 205–220.

- Y.A. Aryeetey, S. Essien-Baidoo, I.A. Larbi, K. Ahmed, A.S. Amoah, B.B. Obeng, L. Van Lieshout M. Yazdanbakhsh, D.A Boakye, J.J. Verweij. Molecular diagnosis of Schistosoma infections in urine samples of school children in Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013 Jun;88 (6):1028-31. . Epub 2013 Mar 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- R.J. Ten Hove, J.J. Verweij, K. Vereecken, K. Polman, L. Dieye , L. van Lieshout, 2008. Multiplex real-time PCR for the detection and quantification of Schistosoma mansoni and S. haematobium infection in stool samples collected in northern Senegal. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 102: 179–185.

- J.J Verweij, E.A. Brienen, J Ziem, L. Yelifari, A.M Polderman, L. van Lieshout, 2007a. Simultaneous detection and quantification of Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus, and Oesophagostomum bifurcum in fecal samples using multiplex real-time PCR. Am J Trop Med Hyg 77: 685–690.

- M.J. Espy, J.R. Uhl, L.M. Sloan, S.P. Buckwalter, M.F. Jones, E.A. Vetter EA, J.D.C. Yao, N.L. Wengenack, J.E. Rosenblatt, F.R. Cockerill, T.F. Smith, 2006. Real-time PCR in clinical microbiology: applications for routine laboratory testing. Clinical Microbiology 19: 165–256.

- F. Nduka, O.J. Nebe, N. Njepuome, D. Dakul, I.A. Anagbogu, E. Ngege, S.M. Jacob and I.A Nwoye, U. Nwankwo, R. Urude, S.M. Aliyu, A. Garba, W. Adamani, C. Nwosu, A. Clark, A. Mayberry, K. Mansiu, N. Benjamin & I, Sunday and G. Amuga. Epidemiological mapping of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis for intervention strategies in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology. 40. 2019, 218. [CrossRef]

- Oyo State disaggregation table data for epidemiological mapping of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis 2014 (retrieved from the Archive of the Oyo State Ministry of Health on April 2022.

- Otamakun Map — Satellite Images of Otamakunoriginal name: Otamakun http://www.maplandia.com/nigeria/oyo/ogo-oluw/otamakun/ retrieved 26th July, 2022.

- T.M. Jaiyeola, E.E. Udoh, & A. Adebambo, A. (2022). Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice towards Lymphatic Filariasis among Inhabitants of an Endemic Town in Oyo State, Nigeria. Journal of Epidemiological Society of Nigeria, 5(1), 23–35. [CrossRef]

- S.L Dellaporta, J Wood, & J.B Hicks. A Plant DNA Mini Preparation: Version II. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter, 1983, Volume 1, Issue 4, 2014 Pp 19-21.

- P. Ferna´ndez-Soto, V. Velasco Tirado, C. Carranza Rodrı´guez, J.L. Pe´rez-Arellano, A. Muro. Long-Term Frozen Storage of Urine Samples: A Trouble to Get PCR Results in Schistosoma spp. DNA Detection 2013 PLoS ONE 8(4): e61703. [CrossRef]

- S. Umar, S.H. Shinkafi, S.A. Hudu, V. Neela, K. Sures, S.A. Nordin & O Malina. Prevalence and molecular characterisation of Schistosoma haematobium among primary school children in Kebbi State, Nigeria. Ann Parasitol.; 63(2): 2017, 133-139.

- R. Tembo, W. Muleya, Y. J Kainga, K.S. Nalubamba, M. Zulu, F. Mwaba, S.A Saad, M. Kamwela, A.N Mukubesa, N. Monde, S.A. Kallu, N. Mbewe, A.M. Phiri. Prevalence and Molecular Identification of Schistosoma haematobium among Children in Lusaka and Siavonga Districts, Zambia. Trop Med Infect Dis. Sep 10;7(9): 2022, 239.

- Privat, B. Jérôme, S. Bakary. et al. Genetic profiles of Schistosoma haematobium parasites from Malian transmission hotspot areas. Parasites Vectors 16, 263 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y.N. Tian-Bi, B. Webster, C.K. Konan, F. Allan, N.R Diakité, M. Ouattara, D. Salia, A. Koné, A.K Kakou, M. Rabone., et al. Molecular characterization and distribution of Schistosoma cercariae collected from naturally infected bulinid snails in northern and central Côte d’Ivoire. Parasites Vectors. 12: 2019, 117.

- T. Huyse, B.L Webster, S. Geldof, J.R. Stothard, O.T. Diaw, K. Polman, D. Rollinson. Bidirectional introgressive hybridization between cattle and human schistosome species. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 5.

- Abe, E.M., Guan, W., Guo, YH. et al. Differentiating snail intermediate hosts of Schistosoma spp. using molecular approaches: fundamental to successful integrated control mechanism in Africa. Infect Dis Poverty 7, 29 (2018). [CrossRef]

- CDC, 2024 DPDx Laboratory Identification of Parasites of Public Health Importance- Schistosomiasis National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria. Retrieved on March 10, 2025 from https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/schistosomiasis/index.html.

- Oey, H., Zakrzewski, M., Gravermann, K., Young, N. D., Korhonen, P. K., Gobert, G. N., & Krause, L. (2019). Whole-genome sequence of the bovine blood fluke Schistosoma bovis supports interspecific hybridization with S. haematobium. PLoS pathogens, 15(1), e1007513.

- Bakuza, J. S., Gillespie, R., Nkwengulila, G., Adam, A., Kilbride, E., & Mable, B. K. (2017). Assessing S. mansoni prevalence in Biomphalaria snails in the Gombe ecosystem of western Tanzania: the importance of DNA sequence data for clarifying species identification. Parasites & vectors, 10, 1-11.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).