1. Introduction

The ability to survey the quality of physical exercise execution is crucial to achieve faster and consistent results from training. Exercising without expert guidance can result in incorrect exercise performance, thus increasing the risk of injuries. Also elite sports can benefit from a real-time classification system to condition the execution of exercises to follow pre-trained custom exercises. Since most athletes already have accessories on them and do not welcome having to add new ones, it is of great importance to have a small and low-cost system capable of classifying the quality of the exercises off-the-person on any environment.

Most of the existing movement classification systems rely on image acquisition, which is very sensitive to changes in scenery, lighting, and difficult to setup. The availability of compact autonomous low-power embedded systems with built-in sensors has enabled the creation of very compact smart sensors integrated into gym equipment, providing real-time feedback on exercise movements. Yet, there are systems around similar architecture but are used only to classify which is the most similar exercise performed, not its correctness.

This paper presents a novel system for automatically recognizing the correctness of movements in physical exercise using Machine Learning algorithms on a low-cost and low-power MCU with integrated movement sensors. The system is demonstrated while being coupled to a weight via magnetic attraction. Moreover, by having the system on the weight (dumbbell, barbell, or kettle-bell) and not on the wrist of the person, it is able to capture the contributions of the wrist movement, which systems on the person can not do.

The proposed system is capable of real-time sensor data acquisition, process the data using trained neural networks to classify the exercise execution quality, and wirelessly communicating this information with a host computer or mobile phone. It has been validated on the operational environment, which is equivalent to a TRL of 6.

To facilitate replication of the results and innovation upon this work, all sources, including the 3D case are made publicly available under an open-source MIT License.

Figure 1.

CNN model definition showing the included layers.

Figure 1.

CNN model definition showing the included layers.

2. Background and Related Work

HAR research is focused on developing systems to automatically recognize and categorize human actions based on sensor data, interpreting body movements to determine activities [

1]. It is used to analyze sports’ performance by tracking the athletes’ movements to anticipate any injury risks, and assessing training programs [

2].

ML has been used in the creation of models from data for classification on low-power devices [

3,

4], while TinyML refers to deploying ML models on resource-constrained devices, and TFLite is optimized for running ML models on limited-resource devices [

5].

CNN are commonly use for HAR systems, combining feature extraction and classification from raw time-series data. The architecture discussed in [

6] features parallel branches for temporal convolutions and max-pooling operations to create intermediate representations for classification. The results highlight the benefits of using max-pooling and varying learning rates during training.

A CNN processes data through convolution and pooling layers, where convolution layers extract features by applying filters and pooling layers reduce data dimensionality. [

6,

7] evaluate CNN with multichannel time-series data from body-worn sensors to achieve higher accuracy. The network have an input layer, convolutional layers, pooling layers, and fully connected layers, with the convolutional layer automatically extracting features and reducing input dimensions, pooling aims to preserve information while reducing complexity [

8] and a fully connected layer combines features to make predictions.

2.1. Accelerometer and Inertial Data

Accelerometers are key sensors for HAR, because they provide measurements on acceleration over 3 axis. They can be placed in various body locations, however the wrist generally offers the best recognition performance [

9]. Achieving effective HAR involves signal pre-processing, feature extraction, and classification. In skateboarding using IMU data [

10] achieved 97.8% accuracy in trick classification. [

11] developed a mobile system with an IMU, detecting golf putts with high accuracy, while [

12] explored jump frequency estimation in volleyball, but found the methodology ineffective. Still in volleyball [

13] used CNN to classify exercises, achieving over 90% accuracy. In skiing [

14] accurately classified exercise techniques using IMU and ML. [

15] predicted jumping errors with an IMU-CNN approach. [

16] showed IMU readings could detect changes in a runner’s state with over 85% accuracy. Outlined standard procedures for HAR systems, complemented by a public dataset and MATLAB framework was the focus of [

17]. Achieving 96.7% accuracy [

18] introduced a lightweight on-device learning algorithm.

2.2. Convolutional Neural Networks for Human Activity Recognition using Mobile and Wearable Sensors

A challenging and still open aspect when dealing with HAR is the identification of the correct set of features for the classifier. Many studies focus on the features extraction for HAR. In [

19], the approach was based on online activity recognition on movement sensor data obtained from real-world smart homes, with four methods used to extract features from the sequence of sensor events and exploring both fixed static window size and dynamic varying window size. The results demonstrated that dynamic window sizes got the best performance.

[

20] evaluated two different feature sets (time-frequency and time-domain) for HAR using data from 61 healthy subjects who performed seven daily activities - resting, upright standing, level walking, ascending and descending stairs, walking, uphill and downhill - while wearing an IMU-based device. The device captured nine signals, including acceleration, angular rate, and Earth-magnetic field data, with a sampling frequency of 80 Hz. Each signal was segmented using a 5s sliding window with a 3s overlap. The study demonstrated that time-frequency feature set consistently delivered higher accuracy.

CNN combine feature extraction and classification, improving HAR performance, as shown in [

6]. Health applications also explore HAR with wearable sensors, [

5] examined MCU for health applications, being power consumption a key challenge. [

21] focused on pedestrian safety using wearable systems for accurate movement prediction. [

22] proposed a memory compression technique for deploying DNN on resource-constrained MCU, maintaining accuracy. The effectiveness of CNN in HAR is highlighted in the studies [

23,

24], and [

7]. In [

25] was demonstrated a 1D CNN model’s superiority in feature extraction, and [

26] applied CNN for sequence classification. Proposing Iss2Image as method in [

27], converting sensor signals into images for CNN-based activity classification, outperforming existing methods. NN and CNN have also shown success in sports classifications, [

28] compared ML classifiers with NN for beach volleyball, while [

29] implemented a NN for gesture recognition. Review [

30] systematically evaluated NN for sport-specific movement recognition, with CNN achieving high accuracy over other methods.

2.3. Human Activity Recognition using Tiny Machine Learning

TinyML offers solutions for HAR on resource-limited devices, [

31] used transfer learning on MCU, achieving high accuracy and low memory usage. Battery life and size constraints are major challenges for HAR systems on small devices, requiring low-power, lightweight ML models, [

32] optimized models to improve inference performance on MCU and [

33] found that model compression could maintain accuracy while reducing size by up to 10 times.

All in all, there are various methods to detect human activity recognition but none have considered capturing movements off-the-person with great precision. Optical, or video, methods do not capture the precision a IMU achieves. Moreover, traditional wearable systems are on the person, being another item for the user to carry and very often collide with the exercise execution.

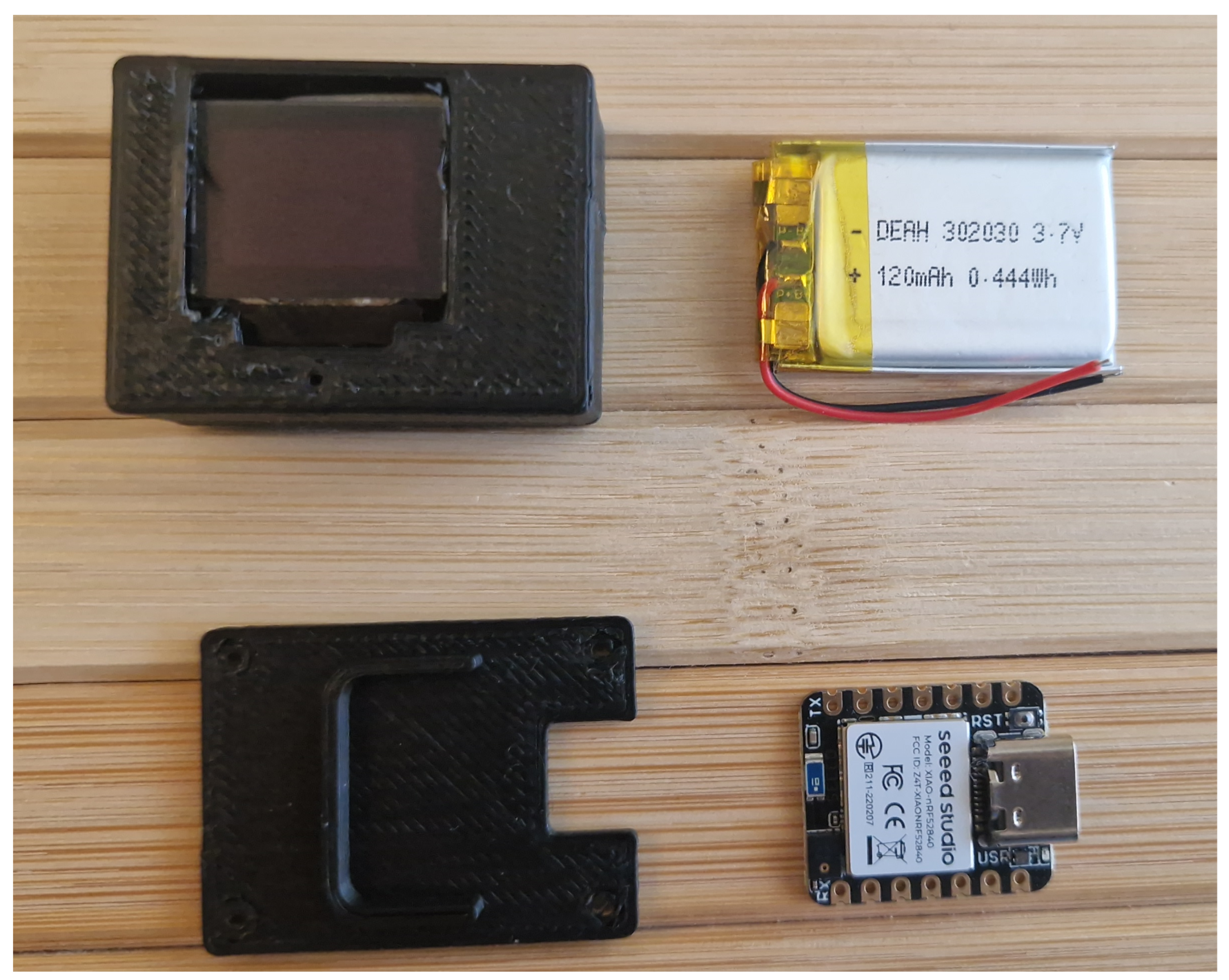

3. Target Platform

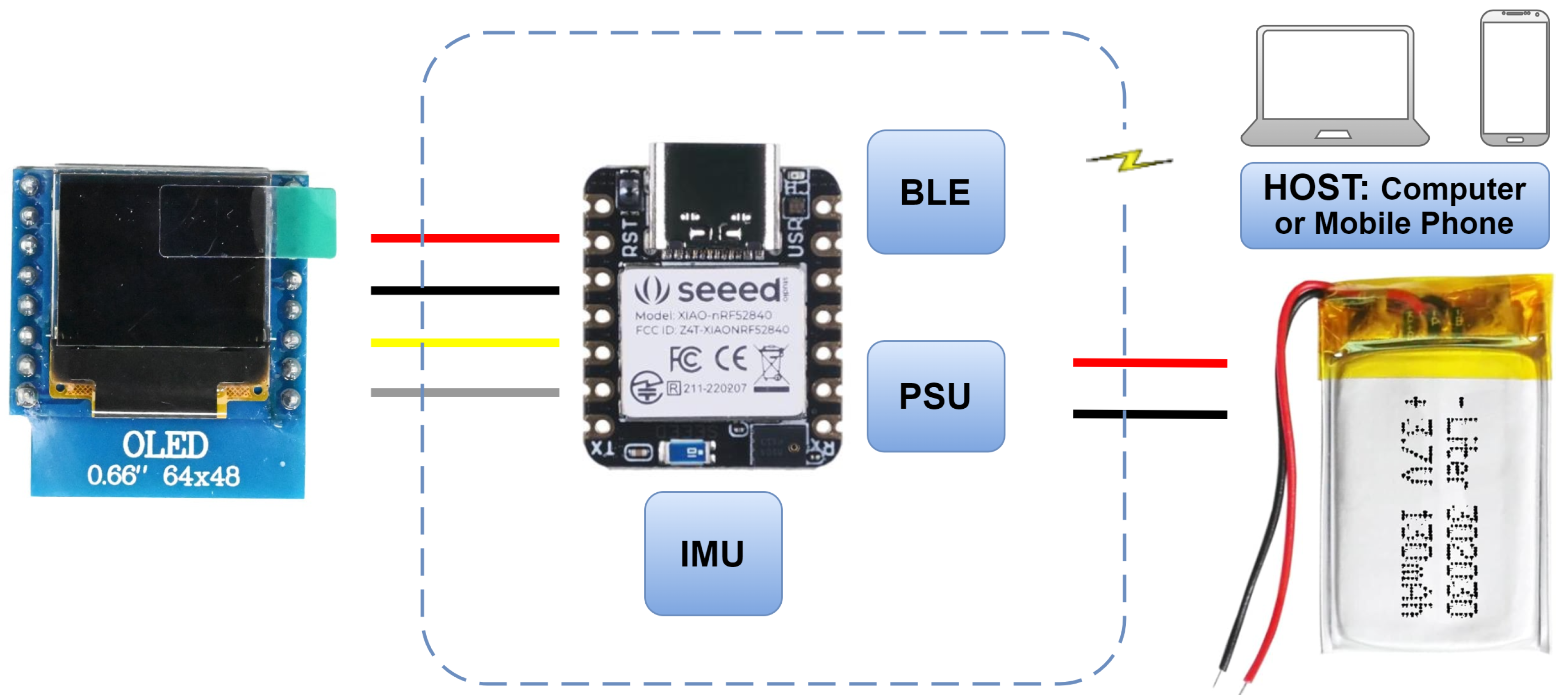

The architecture of the system was defined to ensure low-power consumption, autonomy, and compact design. Each component was selected to maintain a balance between performance, size and energy efficiency, given the limitations of running on a small LiPo battery and a small MCU. The BLE connectivity allows real-time data acquisition and sending the results to an external system, providing real-time feedback to the user. Moreover, the system architecture is designed with modularity in mind, see

Figure 2. As new features or sensors are added, the MCU can be reprogrammed to accommodate these changes, making the platform versatile for future upgrades.

The MCU chosen is the Seeed Studio XIAO nRF52840 Sense, which features a Nordic nRF52840 CPU, 1 MB flash and 256 KB RAM on chip memory. This compact MCU measures only 21x17.5mm and weighs just 4 grams. It also supports Bluetooth 5.0, to communicate with external devices. The embedded sensor LSM6DS3 IMU includes an accelerometer and a gyroscope.

For autonomous operation, a battery was incorporated into the system. A 302030 LiPo battery with a capacity of 120mAh and 3.7V voltage was chosen due to its small size, similar to the MCU. This battery connects directly to the power pins of the XIAO MCU.

Displaying the results of the real-time inference to the user is an important part of the system. A 0.66” OLED display with a resolution of 64x48 was selected. It is small, but fits the MCU size. The OLED display, like the battery, is powered directly by the Seeed Studio XIAO nRF52840 Sense. Additionally, a dedicated mobile application was developed to show the user the number of exercises performed and if they are correctly or incorrectly executed.

4. Methodology

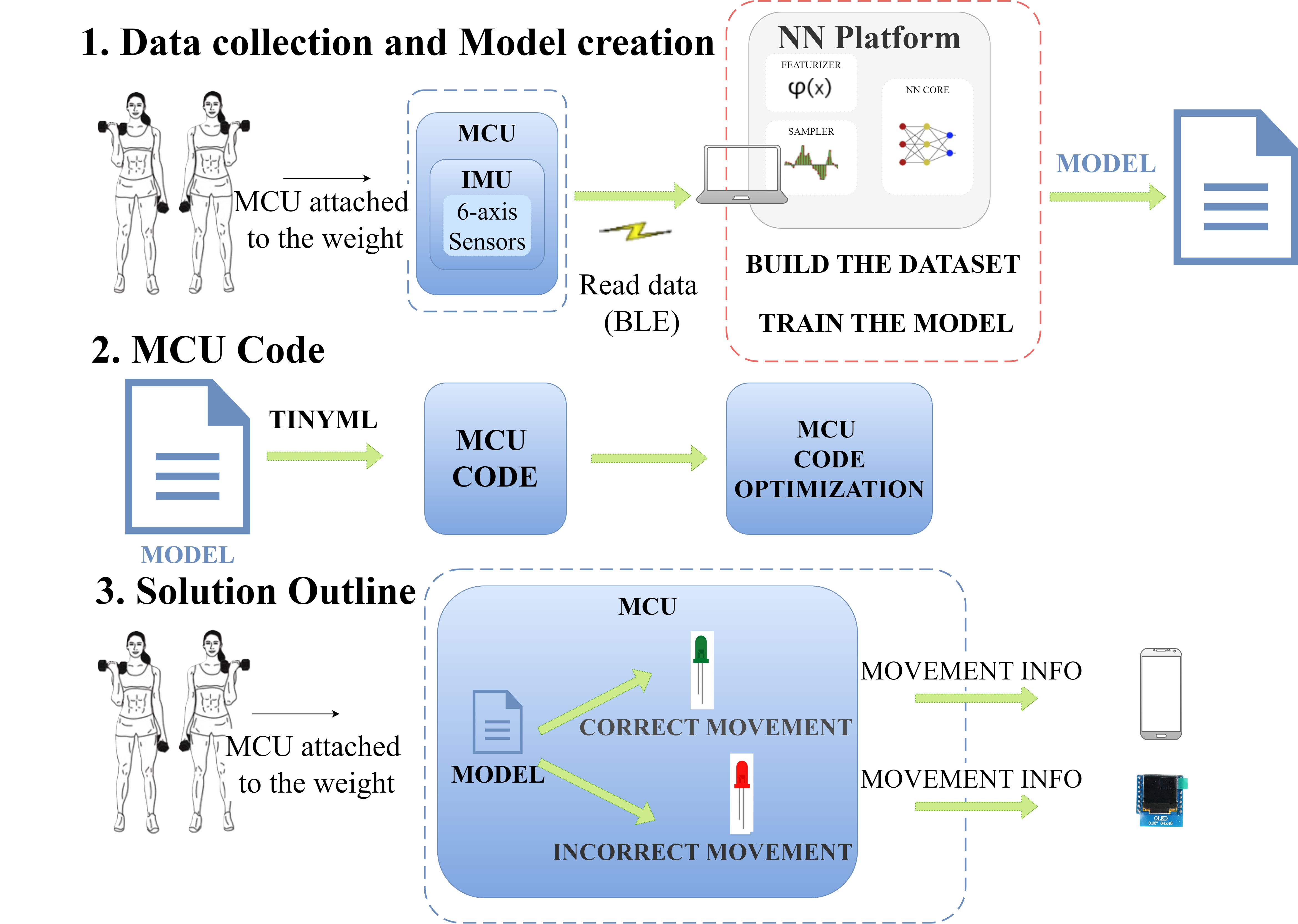

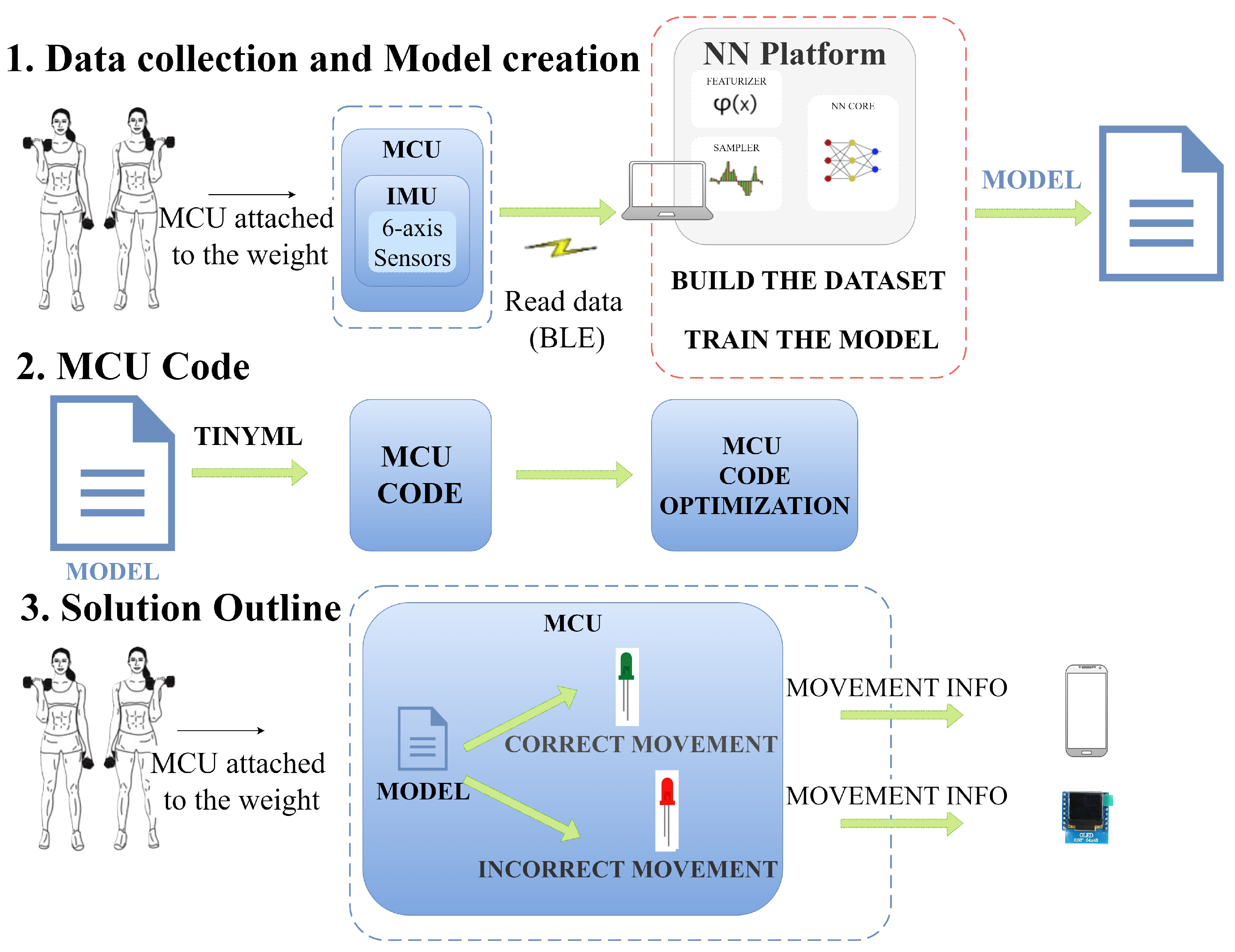

This work was organized in two parts. The first one concerns the collection of raw sensor data from supervised execution of the exercises to create the dataset to train and test the neural network. The second part details on the mapping of the neural network into the MCU software to classify the execution of the exercises in real-time.

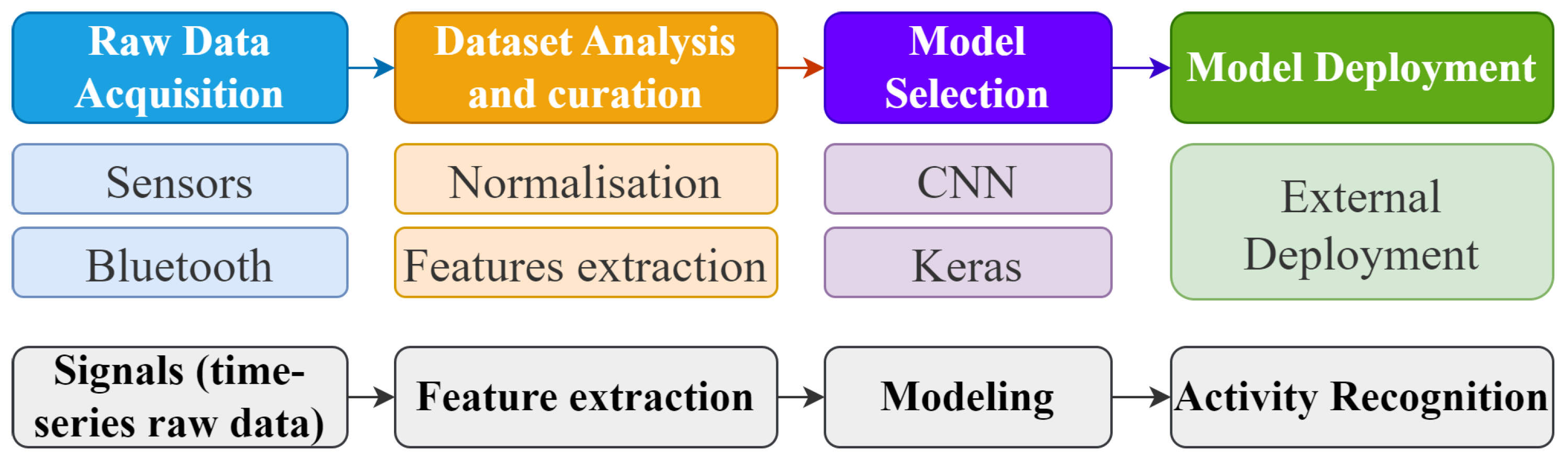

Both parts are done with the same proposed HAR system, which is illustrated in

Figure 3. There are 4 activities for training: raw data acquisition, data analysis and curation, model selection, and model deployment; and another 4 activities for the inference: signal acquisition, feature extraction, modeling, and activity recognition.

The system collects movement data through the IMU accelerometer and gyroscope. The MCU, equipped with a NN implementation, analyzes the movement data on-the-fly, categorizing movements as well or poorly executed. This information is displayed on an OLED display and a mobile app. The steps are illustrated in

Figure 4.

4.1. Raw Data Collection

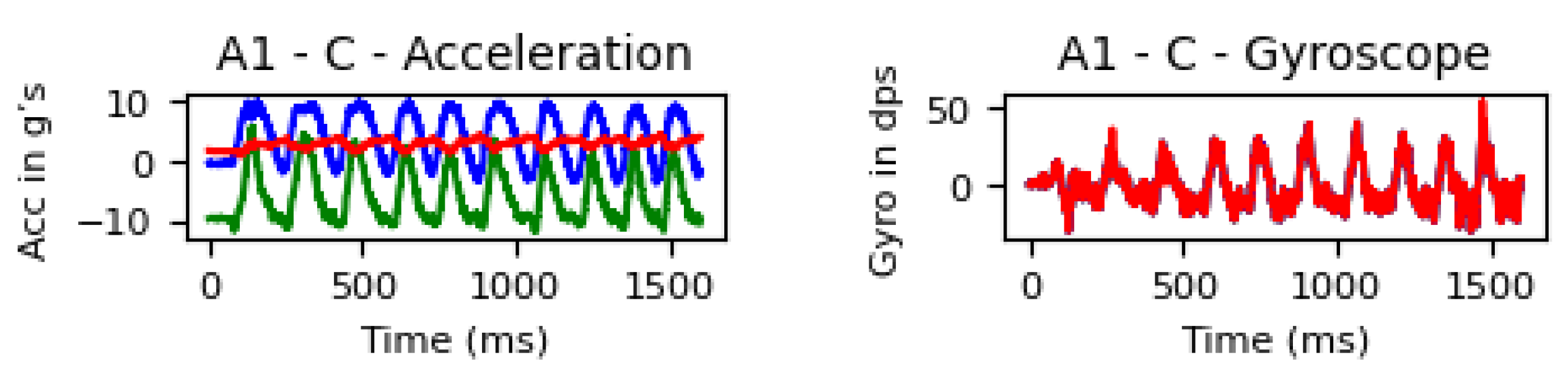

Research on the topic revealed that there were no dataset available that could encompass the targeted exercises. Thus, it was mandatory to create a specific dataset. The input dataset to train the neural network was acquired using 6-axis sensors: accelerometer (X,Y,Z) and gyroscope (X,Y,Z). The then transmitted data wirelessly to the host computer via BLE. Accelerometer recorded in g’s, where 1g is equivalent to the acceleration due to Earth’s gravity ( 9.81 m/s²) and gyroscope data recorded the angular speed in degrees per second, capturing the user’s movements. The X-axis indicates sideways or horizontal movement of the user, Y-axis indicates upward or downward movement and Z-axis indicates forward or backward movement of the user.

4.2. Dataset Construction, Preparation and Curation

The dataset was collected in a controlled environment at ISEL (Polytechnic of Lisbon), during a 4h session with a total of 8 below-average athletes (age range 19–57 years), with the expert supervision of a certified personal trainer. The dataset includes data from various gym exercises, in total 3 different exercises were performed correctly and incorrectly 10 times each by all the subjects: Shoulder Press, Bicep curl and Tricep extension. The system was attached to the weight using a magnet to capture the activities at a sampling frequency of 50 Hz using the built-in tri-axial accelerometers and tri-axial gyroscopes, see

Table 1.

Figure 5.

Signal acquired on the Bicep Curl exercise by the accelerometer (title Acceleration) and the gyroscope (title Gyroscope) from the 1 subjects (X values in blue, Y in green and Z in red).

Figure 5.

Signal acquired on the Bicep Curl exercise by the accelerometer (title Acceleration) and the gyroscope (title Gyroscope) from the 1 subjects (X values in blue, Y in green and Z in red).

Most activity classification methods use windowing techniques to divide the sensor signal into smaller time segments (windows). With the sliding window method, the signal is divided into windows of fixed length [

34]. According to [

35], mid-sized time windows (from 5 to 7 s long) perform best from a range of windows from 1 to 15 s for wrist-placed accelerometers. The results are slightly different for other accelerometer placements, but the trend of mid-size windows performing best still remains a truth according to this study. The features extraction step involves calculating attributes that are able to capture the patterns over a sliding window, the features were extracted directly from the accelerometer raw data. According to [

36], after testing multiple window sizes, they reach a conclusion that in order to maintain a good trade-off between classification performance and resource utilization a window of intermediate size (i.e., 3 s) has been proven to be the best, most of the times 3 seconds were used. The window size was made in an adaptive and empirical manner, to produce good segmentation for all the activities under consideration.

4.2.1. Dataset Analysis and Curation

The first step in data preprocessing is to understand the data that was collected. Just looking at the dataset can give an intuition of what things were needed to focus on. Applying NN training on noisy data would not give quality results as they would fail to identify patterns effectively. Data Processing is, therefore, to improve the overall data quality. Some of the examples are duplicates or missing values that may give an incorrect view of the overall statistics of data, or inconsistent data points that often tend to disturb the models overall learning, leading to false predictions. With this in mind the next step was to clean the data.

Data Cleaning was done as part of data preprocessing [

37] to clean the data by filling missing values, smoothing the noisy data, resolving the inconsistency, and removing outliers. Removing noisy data, involves removing a random error or variance in a measured variable, also removing the beginning and end of the collected samples, because those were times the participant was stopped. All this information was removed manually. For normalization the numerical attributes are scaled up or down to fit within a specified range. In this approach, the data was constrained to a particular set of values. The acceleration values were normalized to: -4 to +4 and gyroscope between: -2048 to +2047.

Table 2 summarizes the number os samples and its duration for each exercise.

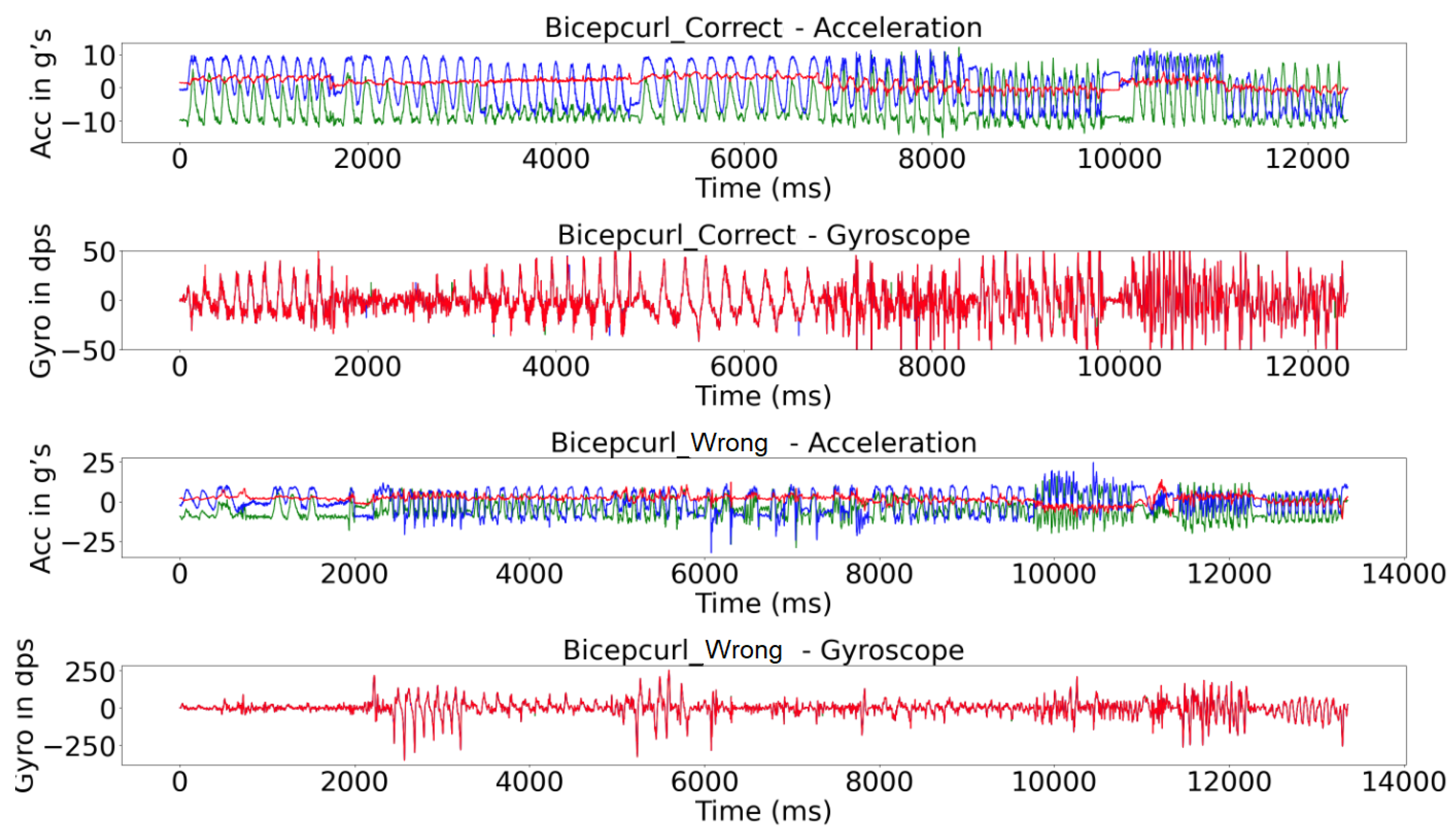

Figure 6.

Signal acquired for the six exercises by all 8 subjects using the accelerometer and the gyroscope during 10 repetitions (X values in blue, Y in green and Z in red. The bottom axis is represented in time (ms)).

Figure 6.

Signal acquired for the six exercises by all 8 subjects using the accelerometer and the gyroscope during 10 repetitions (X values in blue, Y in green and Z in red. The bottom axis is represented in time (ms)).

4.2.2. Feature Extraction

Features are the values that result from processing raw-data are feed into the neural networks. Meaningful features are extracted from the raw sensor data, such as statistical measures, frequency domain analysis, and others that may improve the model’s ability to distinguish between different activities.

4.3. Model Training

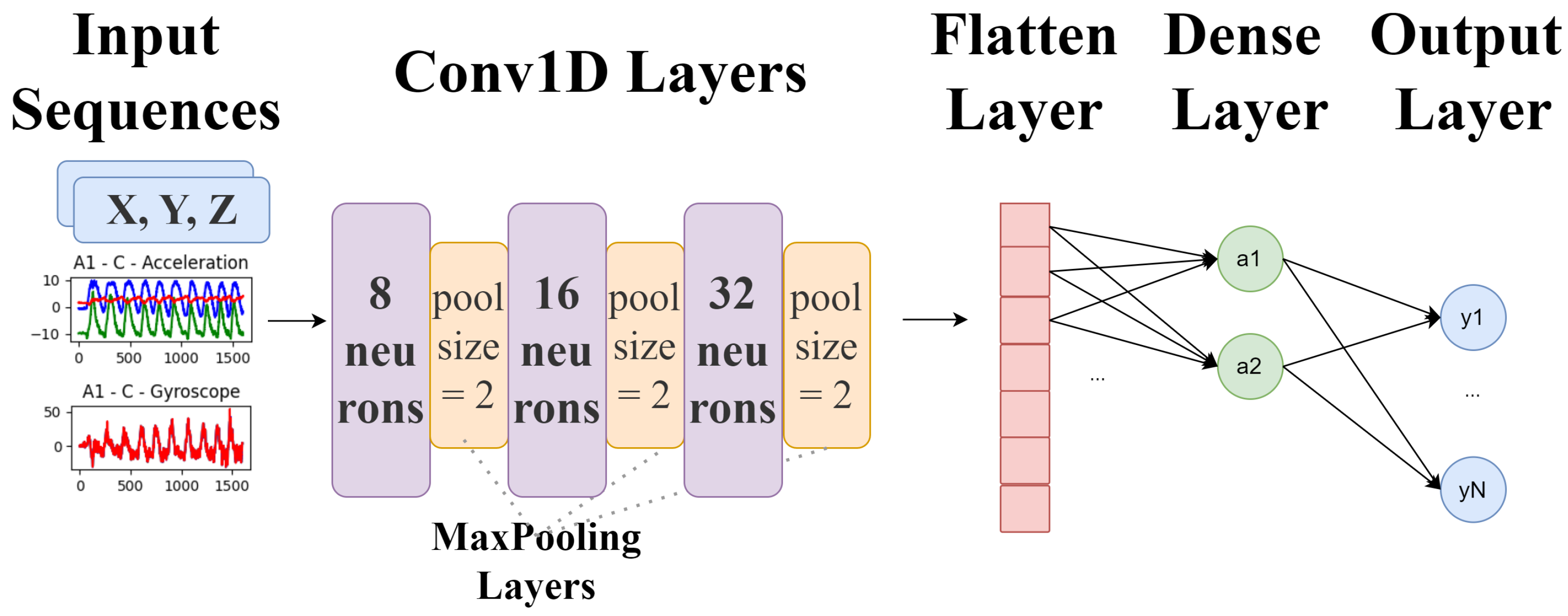

In this work it was used a three-layer stacked convolution and pooling for extracting features from the raw wearable sensor data. Keras NN [

38] is a library that simplifies the creation and training of NN. Keras is the high-level API of the TensorFlow platform. Edge Impulse is an online platform based in Keras NN and uses Tensor Flow Lite [

39], for the training implemented with TFLite used the same approach.

The performance was measured using the following metrics: precision, ratio of correctly predicted positive observations to the total predicted positives for a class; recall, ratio of correctly predicted positive observations to all observations in the actual class; F1 Score, harmonic mean of precision and accuracy, providing a single metric that balances both. All illustrated as equations below (from [

31]) (TP=true positive rate; TN=true negative rate; FP=false positive rate; FN=false negative rate):

4.3.1. Edge Impulse

Edge Impulse is an online development platform for ML on edge devices [

40]. It provides automation and low-code capabilities to make it easier to build datasets for edge devices and integrates with small portable MCU. The platform builds datasets, train models, and optimize libraries to run on any edge device. Also provides a range of NN architectures, including CNN, it makes use of the TensorFlow Lite for training, optimizing, and deploying deep learning models to embedded devices.

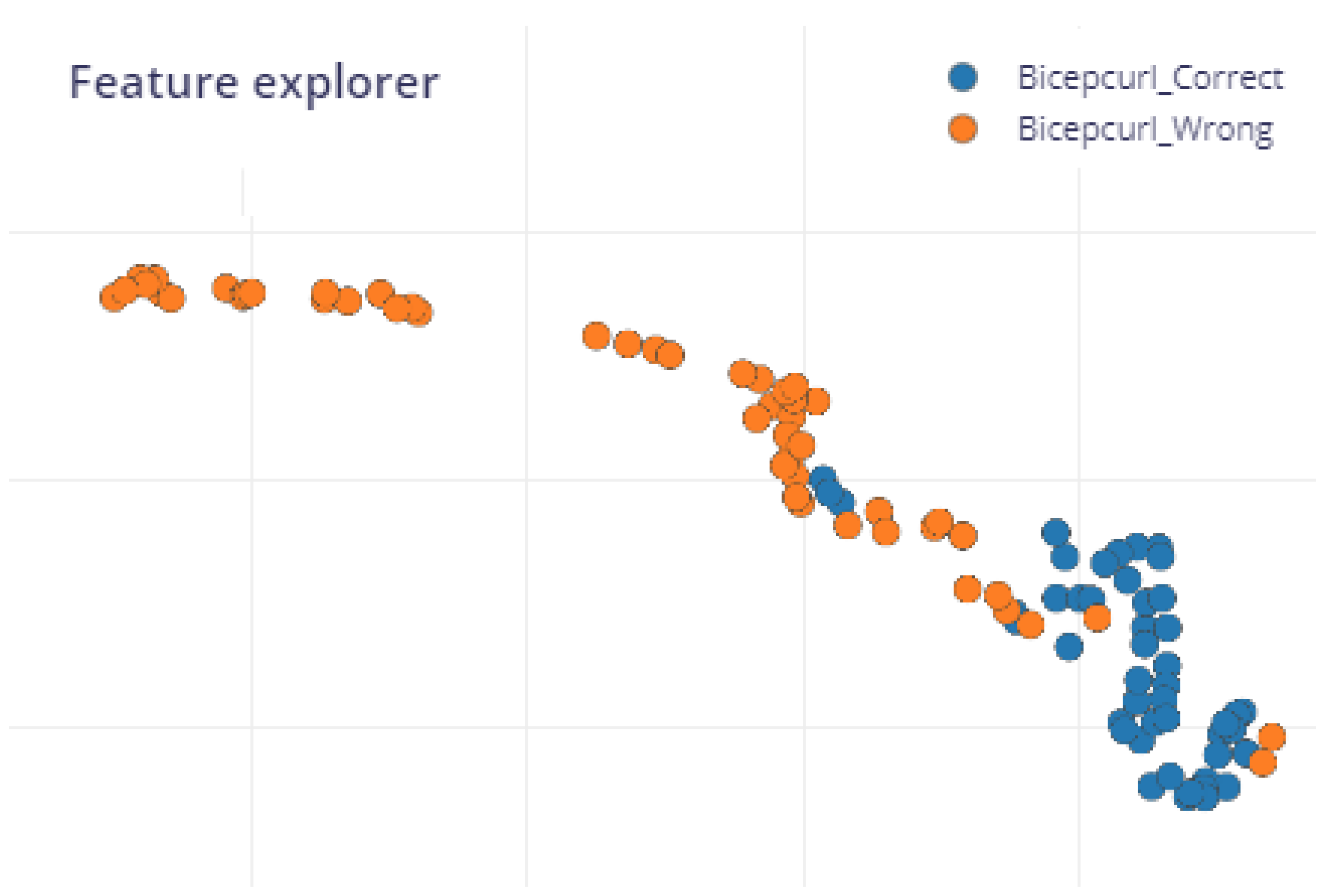

In

Figure 7, the data points for different classes (“Bicep_Correct” and “Bicep_Incorrect”) are in different colors, but there is overlap between wrong and the correct class, probably because the movement wrongly done was still very similar to the correct one. The built-in feature explorer was used to help analyzing the dataset, the feature extraction (processing) method, and how the machine learning model will classify new samples.

A Convolutional 1D network was used with the following CNN layers were: three 1D Conv and three Max polling, one Flatten, two Dense Layers. The exercise “Bicep Curl” got an accuracy of 95% , the “Shoulder Press” got an accuracy of 94.1%, and 72.2% for “Tricep Extension”.

Edge Impulse also provides information about the implementation on the MCU. The inference time is 261 ms, the peak RAM usage is 62.1 kB, and the flash Memory usage is 348 kB.

4.3.2. TensorFlow

The software platform used to build the system is based on python programming language combined with

Jupyter Notebooks and an open-source library for artificial NN called Keras [

38] running on top of TensorFlow. The sensor data was segmented using a 3s sliding window with no overlap. Below it is showed the windowing, for all 6 exercises and for a specific one (bicep curl).

Randomly split input and output pairs into sets of data: 60% for training, 20% for validation, and 20% for testing. To evaluate the accuracy of the model that was trained some data is split to compare its predictions to real data and check how well it match’s.

The training set is used to train the model.

The validation set is used to measure how well the model is performing during training.

The testing set is used to test the model after training.

The architecture of the CNN implemented using TensorFlow, consists of an input layer, three convolutional layers with ReLUs and max-pooling, two fully-connected layers and a soft-max output layer for classification. The kernels applied are small matrix used to filter input data in convolutional layers, while ReLU is an activation function that introduces non-linearity by outputting the input directly if it is positive, otherwise, it outputs zero.

The first hidden layer was a convolutional layer (Conv1D). In this layer, it was applied 8 filters, Kernel size 3, for filtering each signal. Subsequently, the filtered output of the first convolutional layer was transformed non-linearly using ReLUs. The output of the ReLUs was then compressed using temporal max-pooling. After the temporal max-pooling, it was applied a second convolutional layer. This layer took the transformed and pooled output of the first convolutional layer as input.

In the second convolutional layer, it was applied a 16 filter again to a 1D convolutional layer, kernels again with a length of 3 samples. The output of this layer was transformed and compressed by applying the ReLU non-linearity and overlapping temporal max-pooling into a third Conv1D layer. Following the two convolutional layers, fully-connected were added which took the non-linearly transformed and pooled output of the third convolutional layer as input. The fully-connected layers (Dense) consisted of 16 and then 4 units, being units the number of neurons or nodes, with the activation function set to ReLU.

The final output layer was designed to have as many neurons as gestures. For the output layer, the soft-max activation function was employed. Below it is also showed a result of the training and some training metrics:

Training MAE represents the average absolute difference between the predicted values and the actual values on the training data. The validation loss is the error measure on the validation data, while validation MAE is the average absolute error on the validation data. Epochs are how many times our entire training set will be run thought the network during training.

The decrease in loss (training loss) from 0.2635 to 2.6305e-05 and MAE from 0.5057 to 0.0013 across 600 epochs indicates that the model has minimized the prediction errors. While the final validation loss and validation MAE values (0.3042 and 0.357, respectively) suggest that the model generalizes reasonably well. Although there may be slight over-fitting as the validation metrics are higher than the training metrics. The training and validation metrics should show similar results, indicating that the model performs consistently on both seen (training) and unseen (validation) data. When the training metrics are better than the validation metrics, it suggests that the model has learned the specifics of the training data too well, including noise or details that do not generalize to new data, this is characteristic of over-fitting.

Table 3 illustrates the confusion matrix for bicep curl correct and incorrect gesture.

5. Proposed Embedded System for Real-Time Exercise HAR

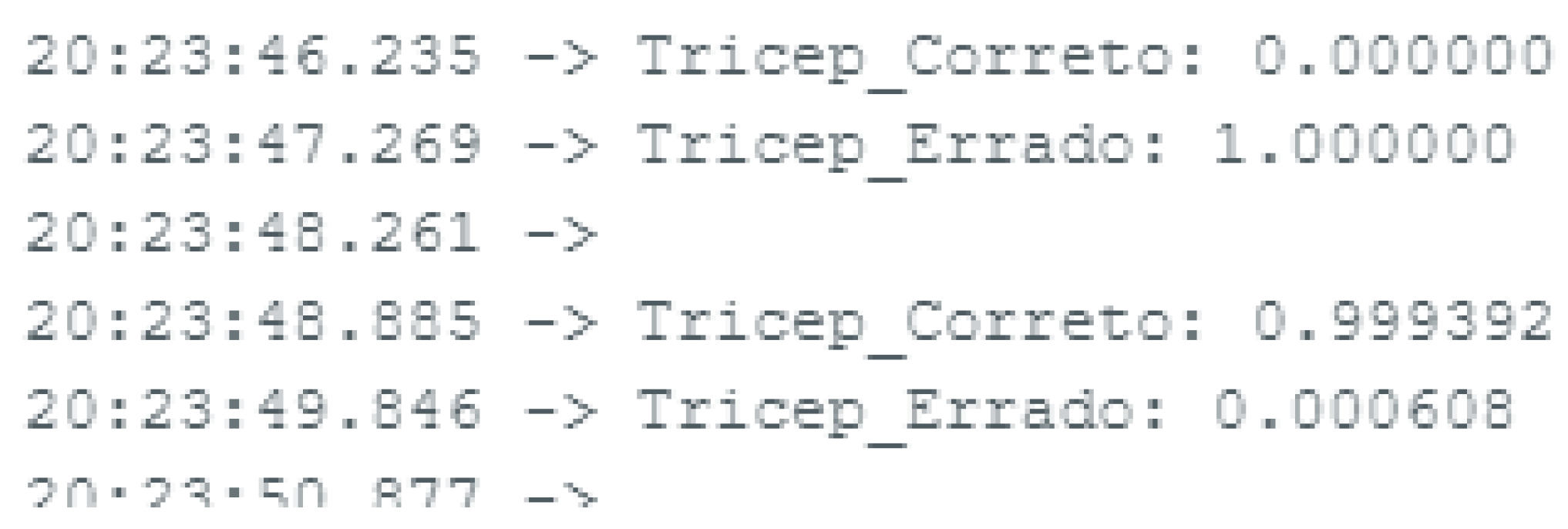

The implementation of a real-time embedded human activity recognition system used TensorFlow Lite in MCU platform to run inference on the generated model. The system uses TensorFlow Lite for MCU (TFLM) to run a pre-trained NN model that identifies if an exercise is well performed based on data from an IMU sensors.

The proposed system is built around a MCU integrated with an LSM6DS3 IMU sensor. The LSM6DS3 sensor captures movement data, including acceleration and gyroscope measurements across the X, Y, and Z axes, which are essential for recognizing different exercises. The work also uses TFLite, a lightweight version of TensorFlow designed specifically for running ML models on devices with limited computational resources.

An OLED display shows feedback about the exercise and if it is correctly done. To improve the user experience the number of exercises correctly or incorrectly done can be seen in the implemented mobile app in real time. The integration of the OLED display and mobile app improves the system interactivity and usability, making it easy for users to understand the system feedback immediately.

Once the data is collected, it is pre-processing to provide the features for the TensorFlow Lite model. This involves normalizing the raw acceleration and gyroscope data, ensuring that the data is suitable for the ML model to process. The preprocessed data is then input into the TensorFlow Lite model, which has been previously trained to recognize specific exercises. The model performs inference on the input data, using tensors, generating a set of probabilities that correspond to different predefined exercises. The exercise with the highest probability is identified as the recognized exercise. finally, the system displays the exercise correctness on the OLED screen and mobile app, providing immediate feedback to the user.

The main application runs continuously, reading data from the IMU sensor, pre-processes the required number of data samples, which are then input into the TensorFlow Lite model for inference. After the model processes the data, the recognized exercise is identified based on the highest output probability. The exercise is then displayed on the OLED screen, and in the Arduino Serial if connected to the PC.

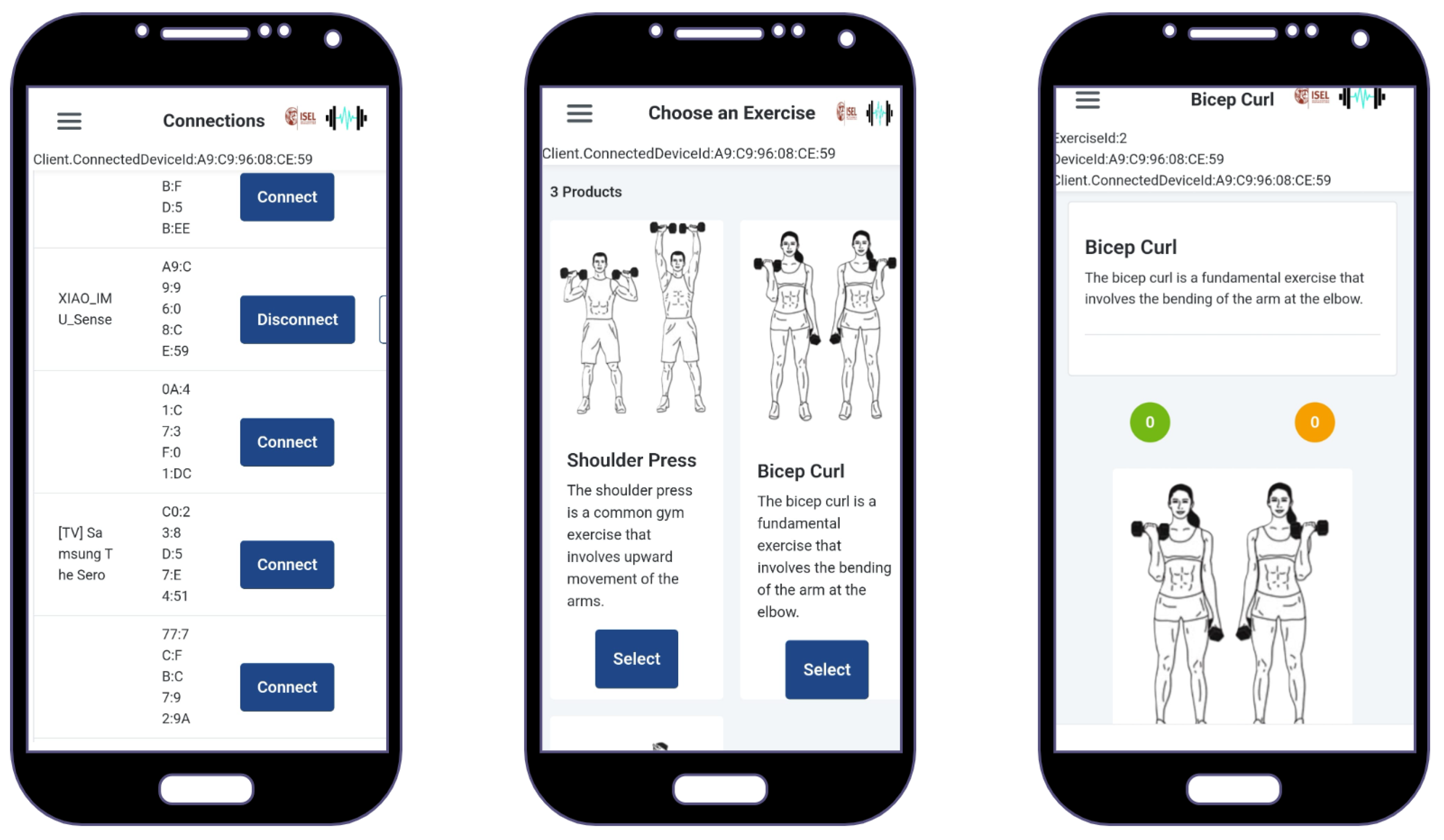

6. Android Mobile Application

A mobile application was developed to interface with the HAR system. The app provides users with a user-friendly way to monitor and track their exercises, displaying real-time feedback based on the data processed by the embedded system. For the app development it was used the OutSystems Low-Code Platform [

41]. Low-code is a visual software development approach that simplifies the creation of applications. The integration with the Embedded system was made using BLE. The Embed system advertises that is ready for connections. The BLE specification includes a mechanism known as notify that lets you know when data’s changed. On the Mobile app side the connection is made to the Embedded System and afterwards a Listener is defined that is waiting for notification from the system indicating that a movement was detected. It was defined a protocol of only 1 byte to reduce the payload of the communication: 0x00 - Connected; 0x01 - Correct movement detected; 0x02 - Indicating an incorrect movement.

For the the prove of concept 3 screens were designed and implemented, as in

Figure 8:

Connection screen - to connect/disconnect from the embedded system or do a test read.

Exercises screen - to choose the exercise that will be performed.

Exercise Detail screen - show the detailed of the chosen exercise and the counters: in green the number of correctly made exercises and orange the wrongly done.

7. Experimental Results

The model trained on Edge Impulse achieved a good overall performance, with accuracy ranging from 72% to 95%, depending on the exercise performed. In Edge Impulse the accuracy was between 70% up to 95% while in TFLite, the accuracy was around 60%.

The OLED display provides a user interface, that shows the recognized exercise immediately after its classification. The system’s performance can be further optimized by tuning the model, adjusting the sampling rate, or optimizing the TensorFlow Lite interpreter for specific hardware. Potential improvements include integrating more complex models, more exercises or additional sensors for richer data input.

8. 3D-Printable Case

To assemble a prototype to be added to gym weights and indicating the user if the exercise is correctly done, this way like already mentioned before the system could help prevent injuries from exercising without supervision. A box was built to make it a compact fully integrated systems, illustrated in

Figure 10, it is light (5 grams) and all the components from: MCU, OLED and battery are inside the box, making it completely portable.

Table 4.

Results obtained in the Edge Impulse platforms with the described CNN using the Raw Data.

Table 4.

Results obtained in the Edge Impulse platforms with the described CNN using the Raw Data.

| Exercise |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 Score |

Accuracy (%) |

Training time (s) |

| Bicep Curl |

0.80 |

0.80 |

0.80 |

80.0% |

181 |

| Shoulder Press |

0.95 |

0.94 |

0.94 |

94.1% |

181 |

| Tricep Extension |

0.73 |

0.72 |

0.72 |

72.2% |

180 |

Table 5.

Results obtained in the Python platform with the described CNN using the Raw Data.

Table 5.

Results obtained in the Python platform with the described CNN using the Raw Data.

| Exercise |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 Score |

Accuracy (%) |

Training time (s) |

| Bicep Curl |

0.76 |

0.65 |

0.64 |

65% |

336 |

| Shoulder Press |

0.60 |

0.63 |

0.60 |

59% |

350 |

| Tricep Extension |

0.60 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

60% |

317 |

The implemented embedded system for real-time movement recognition involves multiple components such as: MCU, an OLED display, a battery, illustrated in

Figure 10.

9. Conclusions and Future Work

The goal of this work was to develop an autonomous embedded system to give the gym user feedback about the correctness of the exercise in real-time. It also features a mobile application to register the classification outputs.

The final design of the proposed system is comprised of a low-power, low-cost, small volume, and lightweight embedded system based on the MCU Seeed Studio XIAO nRF52840 Sense, a rechargeable battery, and an OLED display. These components were selected to obtain the best trade-off between performance, energy efficiency, and volume.

Since no existing dataset was found that could be re-used to fulfill the objectives of this work, there was a need to create a dataset tailored to the exercises in this study, under the supervision of a certified personal trainer.

Sample datasets were necessary for testing specific components of the system and the MCU, but collecting live data enabled the training of the NN to specific exercises chosen to this work, including both correctly and incorrectly performed.

The classification algorithm implemented on the MCU uses NN techniques to train the model was created capable of categorizing movements based on their correctness and give that feedback in real-time. It was trained using different platforms and techniques, including Edge Impulse and a reduced TensorFlow, TFLite model, optimized specifically for the hardware’s limited computational power and memory.

Table 6.

Model size comparison.

Table 6.

Model size comparison.

| Memory (KB) |

Edge Impulse |

TFLite |

| |

Bicep Curl |

Shoulder Press |

Tricep Extension |

All |

Bicep Curl |

Shoulder Press |

Tricep Extension |

All |

| Model Size |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

256.8 |

256.7 |

256.4 |

256.8 |

| Quantized Model |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

73.5 |

73.4 |

73.2 |

73.6 |

| TFLite Model |

348.0 |

348.0 |

348.0 |

348.0 |

453.7 |

453.0 |

451.8 |

453.9 |

In comparison, Edge impulse provides better accuracy, but it is limited to the features supported on the platform. TensorFlow can implement any NN model, but it takes longer to achieve good classification results.

The results indicated an accuracy up to 94.1% in identifying exercises correctly or incorrectly performed . This validates the idea that real-time feedback can help on physical exercise safety.

All in all, in this paper it was demonstrated the applicability of the proposed system to prevent injuries from physical exercises. This work was limited to a small dataset of six exercises, so future research should explore a broader range of movements and incorporate larger datasets. Future work will also focus on the classification method to improving the system’s accuracy and support for more and different exercises.

Source files

The work developed is publicly available under MIT Open Source License on Hub repository, where all the implementation details and supplementary materials. The repository can be found in: (removed for blind review)

Funding

This research was funded by XXX grant number XXX.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in [github] at [DOI/URL].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shah, D. Human Activity Recognition (HAR): Fundamentals, Models, Datasets, 2023.

- Brownlee, J. Evaluate Machine Learning Algorithms for Human Activity Recognition. Machine Learning Mastery 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baheti, P. A Simple Guide to Data Preprocessing in Machine Learning. Website V7 Labs 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, W.; Daniel, S. TinyML - Machine Learning with TensorFlow Lite on Arduino and Ultra-Low-Power Microcontrollers; O’Reilly Media, 2019.

- Diab, M.S.; Rodriguez-Villegas, E. Embedded Machine Learning Using Microcontrollers in Wearable and Ambulatory Systems for Health and Care Applications: A Review. Sensors 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, F.M.; Grzeszick, R.; Fink, G.A.; Feldhorst, S.; ten Michael Hompel. Convolutional Neural Networks for Human Activity Recognition Using Body-Worn Sensors. Informatics, volume 5, issue 2 of the journal in 2018 2018.

- Nguyen, L.T.; Yu, B.; Mengshoel, O.J.; Jiang Zhu, P.W.; Zeng, J.Z.M. Convolutional Neural Networks for Human Activity Recognition using Mobile Sensors. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2014.

- Boureau, Y.L.; Ponce, J.; Fr, J.P.; Lecun, Y. A Theoretical Analysis of Feature Pooling in Visual Recognition, 2010.

- Price, B.A.; Gooch, D.; Bandara, A.K.; Bennasar, B.N.M. Significant Features for Human Activity Recognition Using Tri-Axial Accelerometers. MedCentral 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Groh, B.H.; Kautz, T.; Schuldhaus, D. IMU based Trick Classification in Skateboarding. Workshop on Large-Scale Sports Analytics as part of the 21st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, U.; Schmidt, M.; Hennig, M.; Dassler, F.A.; Jaitner, T.; Eskofier, B.M. An IMU-based Mobile System for Golf Putt Analysis. Sports Engineering 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarning, J.M.; Mok, K.M.; Hansen, B.H.; Bahr, R. Application of a tri-axial accelerometer to estimate jump frequency in volleyball. Sports Biomechanics 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautz, T.; Groh, B.H.; Hannink, J.; Jensen, U.; Strubberg, H.; Eskofier, B.M. Activity recognition in beach volleyball using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindal, O.M.H.; Seeberg, T.M.; Tjønnås, J.; Haugnes, P. ; Øyvind Sandbakk. Automatic Classification of SubTechniques in Classical Cross-Country Skiing Using a Machine Learning Algorithm on Micro-Sensor Data. Sensors, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, H.; Ohgi, Y.; Lee, J. Learning to Judge Like a Human: Convolutional Networks for Classification of Ski Jumping Errors. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers (ISWC) 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, C.; Reilly, M.O.; Farrel, A.V.; Clark, L.; Longo, V. Binary Classification of Running Fatigue using a Single Inertial Measurement Unit. Proceedings of the IEEE 14th International Conference on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks (BSN) 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bulling, A.; Blanke, U.; Schiele, B. A Tutorial on Human Activity Recognition Using Body-Worn Inertial Sensors. ACM Computing Surveys 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, M.; Saha, S.S. On-Sensor Online Learning and Classification Under 8 KB Memory. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yala, B.F.N. Feature extraction for human activity recognition on streaming data. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Balestra, G.; Rosati, M.K.S. Comparison of Different Sets of Features for Human Activity Recognition by Wearable Sensors. PubMed Central 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, S.; de Godoy, D.; Islam, B.; Islam, M.T.; Nirjon, S.; Kinget, P.R.; Jiang, X. Improving Pedestrian Safety in Cities using Intelligent Wearable Systems. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Jia, Z.; Shi, Y.; Hu, J. Lightweight Run-Time Working Memory Compression for Deployment of Deep Neural Networks on Resource-Constrained. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Shi, W.; Tian, J.; Qi, Z.; Li, B.; Hao, H.; Xu, B. Attention-based bidirectional long short-term memory networks for relation classification. 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2016) - Short Papers 2016, pp. 207–212. [CrossRef]

- Mutegeki, R.; Han, D.S. A CNN-LSTM Approach to Human Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR).; IEEE, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarova, M.; Tsokov, A.A.P.S. Accelerometer-based human activity recognition using 1D convolutional neural network. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee, J. 1D Convolutional Neural Network Models for Human Activity Recognition. Machine Learning Mastery 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, J.; Huynh-The, T.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.I.; Lee, S.; Hur, T. Iss2Image: A Novel Signal-Encoding Technique for CNN-Based Human Activity Recognition. Sensors 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Ben-David, S. Understanding Machine Learning: From Theory to Algorithms. Published 2014 by Cambridge University Press. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, T.A. Convolutional Neural Network for Hand Gesture Identification on FPGAs. Master’s thesis, Instituto Superior Técnico de Lisboa, 2022.

- Emily, C.; J, S.A.; Kevin, B.; Sam, R. Machine and deep learning for sport-specific movement recognition: a systematic review of model development and performance. Journal of Sports Sciences 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hayajneh, A.M.; Hafeez, M.; Zaidi, S.A.R.; McLernon, D. TinyML Empowered Transfer Learning on the Edge. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Banbury, C.; Zhou, C.; Fedorov, I.; Navarro, R.M.; Thakker, U.; Gope, D.; Reddi, V.J.; Mattina, M.; Whatmough, P.N. BAMBURY micronets neural network architectures for deploying tinyml applications on commodity microcontrollers. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. A TinyML Approach to Human Activity Recognition. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Preece, S.J.; Goulermas, J.Y.; Kenney, L.P.; Howard, D.; Meijer, K.; Crompton, R. Activity identification using body-mounted sensors - A review of classification techniques, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Twomey, N.; Diethe, T.; Fafoutis, X.; Elsts, A.; McConville, R.; Flach, P.; Craddock, I. A comprehensive study of activity recognition using accelerometers. Informatics 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzi, E.; Donati, M.; Freschi, V. Exploring Artificial Neural Networks Efficiency in Tiny Wearable Devices for Human Activity Recognition. Sensors 2022. [Google Scholar]

- K.R.Baskaran, M. K.R.Baskaran, M. Machine Learning Algorithms for Human Activity Recognition. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, Francois et al.. Keras. Available online: https://github.com/fchollet/keras (accessed on 12.03.2025).

- AI, G. Tensor flow lite - deploy machine learning models on mobile and edge devices. https://www.tensorflow.org/lite, 2012.

- Impulse, E. Edge Impulse website. Available online: https://docs.edgeimpulse.com/ (accessed on 12.03.2025).

- OutSystems. OutSystems website. Available online: https://www.outsystems.com/ (accessed on 12.03.2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).