1. Introduction

At the Orinoco region in Colombia, known as Eastern Plains, there are near 5’600.000 bovines [

1] that graze on

Urochloa spp. pastures, especially

U. brizantha,

U. decumbens, U. dictyoneura,

U. humidicola and

U. ruziziensis x

U. decumbens x

U. brizantha (“mulato” hybrid) [

2].

Urochloa spp. is a grass frequently used in tropical regions; however, some species have caused toxicosis in herbivores due to its content of steroidal saponins that can cause hepatic disfunction leading to photosensitization [

3]. Steroidal saponins are glycosides, in which the aglycone, called sapogenin, binds to one, two or three carbohydrates. The main saponins isolated from

Urochloa spp. are protodioscin and dioscin [

4,

5,

6], both of which can produce the aglycone diosgenin after hydrolysis in the rumen. Diosgenin in turn undergoes epimerization to epismilagenin, which once absorbed and taken to the liver, is conjugated with glucuronic acid by glucuronosyl transferases. The conjugated epismilagenin is translocated to the bile canaliculi where it binds to calcium forming glucuronate crystals that precipitate inside the bile canaliculi, causing obstruction and injury. Obstruction of the canaliculi causes an abnormal blood circulation of phylloerythrin, a photoactive chlorophyll metabolite that is capable of causal dermal lesions [

7,

8].

The photosensitization associated with

Urochloa spp. occurs only sporadically. Sapogenin content in plants varies [

9], and factors like age, relative humidity, temperature, and rainfall affect its content [

10]. However, the research work that has been conducted to investigate the relationship between environmental conditions and photosensitivity metabolites in

Urochloa spp. has focused on measuring protodioscin not diosgenin [

11,

12,

13]. On the other hand, in the Orinoco region of Colombia, it is not uncommon to see photosensitization in ruminants, which farmers usually attribute to the ingestion of plants different from grasses [

14]. Because diosgenin is the aglycone common to the two main steroidal saponins present in

Urochloa spp. (protodioscin and dioscin) it becomes relevant to obtain information about its content in this pasture.

The aim of the present study was to determine and quantitate diosgenin in the main species of Urochloa from the Colombian Orinoco region (U. brizantha, U. decumbens U. dictyoneura, U. humidicola and U. ruziziensis x U. decumbens x U. brizantha) and to investigate whether there are differences in content associated with the grass species and age, and with the place and time of sampling.

2. Results

Diosgenin content varied widely among the different Urochloa species, with the highest average content found in the hybrid (505 ± 422 µg/g, with values ranging from 15 to 1972 µg/g) followed by U. decumbens (361 ± 285 µg/g, 50 to 1207µg/g), U. brizantha (301 ± 181 µg/g, 68 to 735 µg/g), U. humidicola (187 ± 119 µg/g, not detectable -N.D. - to 732 µg/g) and U. dictyoneura (73 ±133 µg/g, N.D. to 521 µg/g). Only 8% of the samples analyzed had no detectable diosgenin levels which corresponded to U. humidicola (39%) and U. dictyoneura (61%); further, these two pastures showed the lowest sapogenin concentrations. From all pastures sampled (240), almost a quarter (27%) had diosgenin levels ranging from N.D. to 100 μg/g, while most of the pastures sampled (60%) had diosgenin levels between 100 and <800 μg/g. Only 5% of the grasses analyzed had levels >800 μg/g, 69% of them corresponding to the mulato hybrid and 31% to U. decumbens.

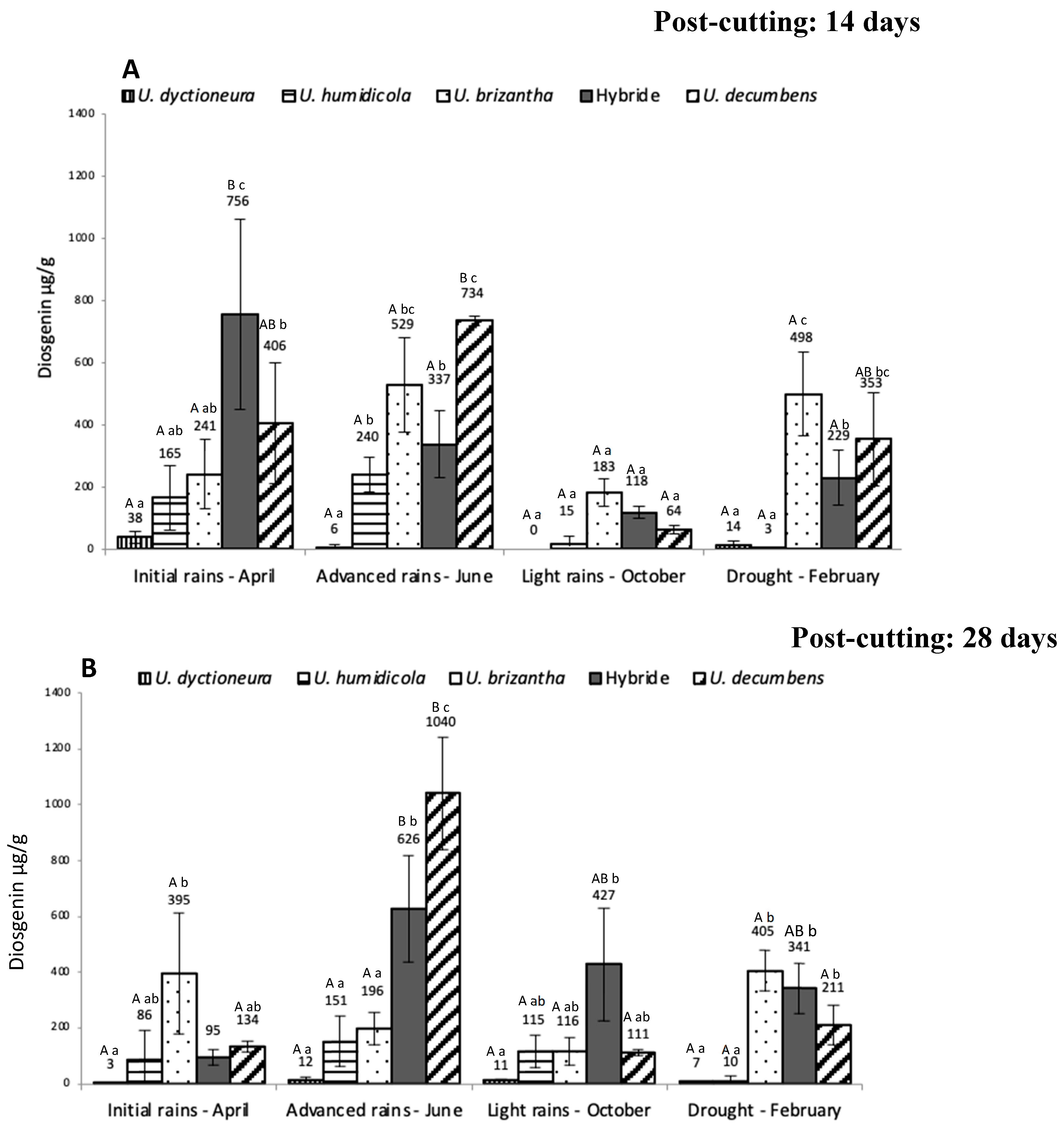

According to the factorial model applied to the data, there was an interaction between the

Urochloa species, the sampling time, and the post-cutting time (P<0.05), suggesting that diosgenin content is dependent of these three factors. The sapogenin concentration under these conditions are presented on

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 for “piedemonte” and the alluvial valley of the Ariari River, respectively.

Regarding to post-cutting time, it was discovered that for some periods and species, diosgenin levels were either lower (in “piedemonte” U. decumbens in April; in alluvial valley U. dictyoneura also in April; P<0.05) or higher (in “piedemonte” U. decumbens in June; in alluvial valley the same species in April; P<0.05) at 28 days post-cutting.

In “piedemonte” (

Figure 1) at 14 days post-cutting

U. dictyoneura and

U. humidicola had the lowest levels of diosgenin. Additionally, the hybrid and

U. decumbens had more diosgenin in the rainy season (April and June, respectively). Diosgenin levels at 28 days post cut showed a similar pattern:

U. dictyoneura and

U. humidicola had the lowest levels and

U. decumbens and the hybrid showed the highest concentration in the rainy season.

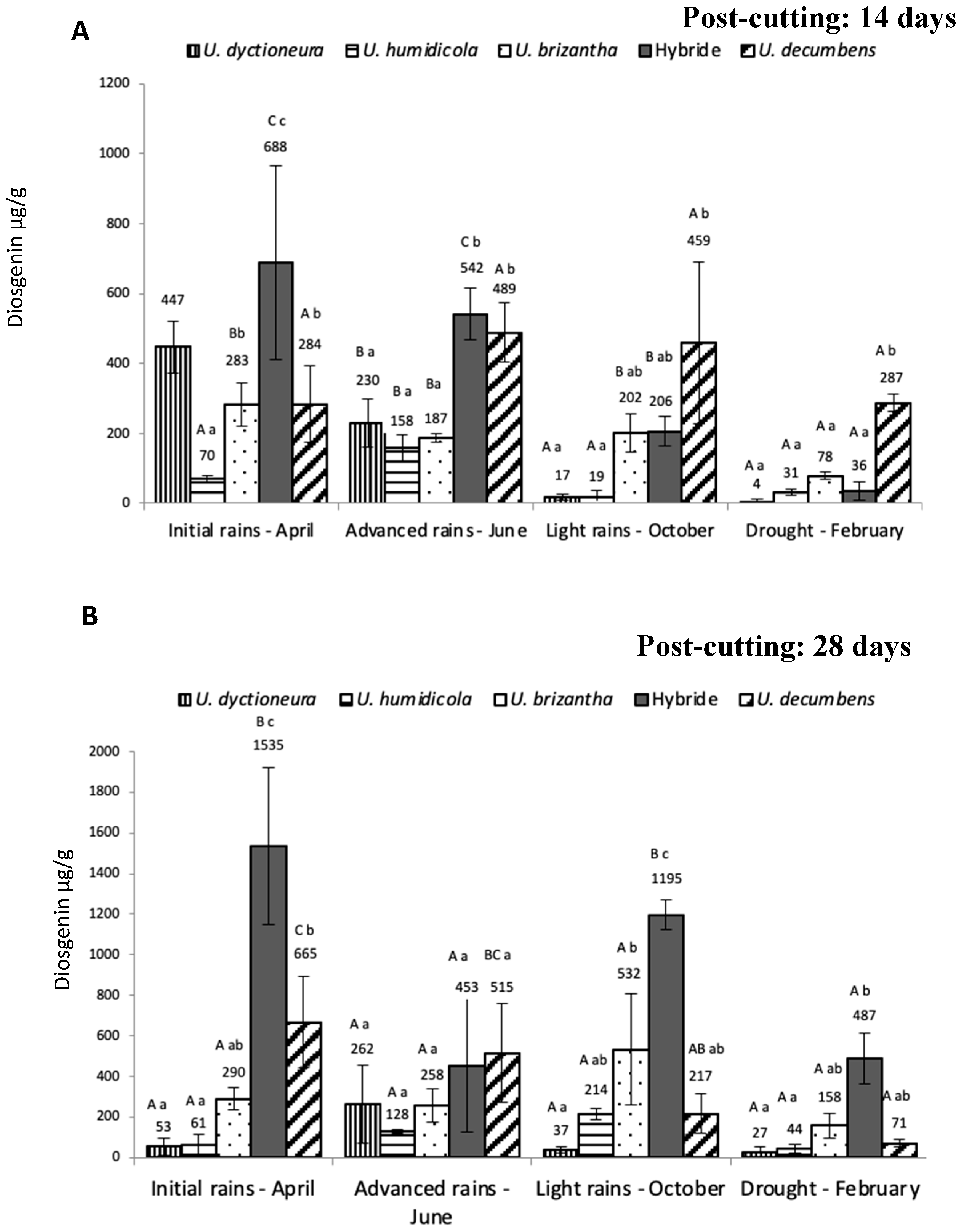

Figure 2 shoows the diosgenin content in

Urochloa spp. from the alluvial valley. At 14 days post cut

U. humidicola produced lesser amounts of diosgenin while

U. dictyoneura, in contrast with “piedemonte”, achieved higher concentrations on the rainy season. Except for

U. decumbens all pastures showed significantly higher diosgenin levels in periods with greater precipitation. Diosgenin levels in the alluvial valley at 28 days after regrowth showed a similar pattern:

U. humidicola had the lowest concentration, the hybrid (in April, October, and February) and

U. decumbens (in April) showed the highest diosgenin levels, and all pastures recorded the lowest diosgenin concentrations in the dry season.

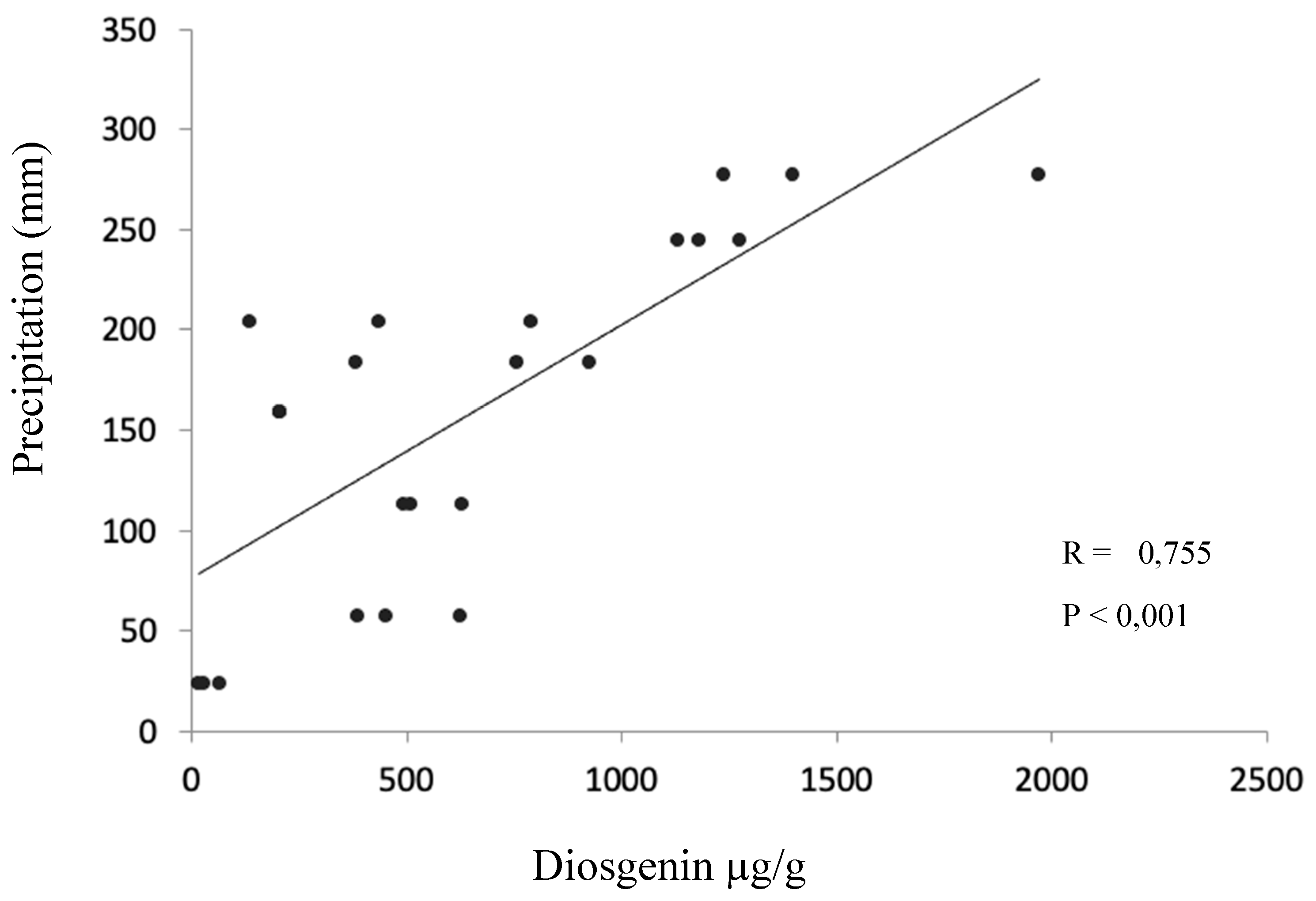

Only one significant Pearson correlation coefficient was found, which corresponded to the correlation between precipitation and diosgenin content for the hybrid from the alluvial valley (

Figure 3).

3. Discussion

The most commonly used biomarker of saponin content in forages ingested by ruminants has been protodioscin [

9,

15,

16]; however,

U. decumbens and

U. brizantha have been shown to contain other saponins in addition to protodioscin. Among other saponins reported in these grasses are dichotomine, saponin B, and dioscine and its C-25 epimerized form [

17,

18,

19,

20], all of which contain the sapogenin diosgenin. Diosgenin, therefore, is a better biomarker for steroidal saponin content in

Urochloa spp. compared to protodioscin.

In the present study, diosgenin content was particularly high at day 28 post-cutting for

U. decumbens and the hybrid from “piedemonte” in the rainy season; however, at 14 days, some species had higher levels (e.g.,

U. humidicola from alluvial valley in April).

In vitro cultures of

Trigonella foenum graecum reach the highest diosgenin levels at 21 to 38 days of age, decreasing then at 50 days [

21]. This early higher production is needed by younger plants as a defense mechanism against possible aggressors (microorganisms, insects, herbivores) [

21,

22]. Regrowth time of 14 and 28 days (sampling times in the present study) are part of early stages of grass growth [

23]; therefore, variations in diosgenin levels could correspond to the development of defenses against microorganisms and predators at early stages.

In the present study,

U. dictyoneura and

U. humidicola showed the lowest diosgenin concentrations.

U. humidicola has been associated with photosensitization in cattle but its protodioscin content is low [

19], suggesting that other metabolite(s) may be present in the grass [

10,

24]. Measurement of diosgenin content rather than protodioscin content would be a better biomarker of potential hepatotoxicity in

U. humidicola. The highest diosgenin concentration found in

U. humidicola was 732 μg/g in a 28-day-old pasture harvested in the alluvial valley in June. The minimum diosgenin toxic concentration is estimated at 800 μg/g [

25], a level close to the maximum value recorded in the present study for

U. humidicola. Therefore, it is possible that under certain conditions, this grass species may be causing toxicity in cattle in Colombia due to its diosgenin content.

Concerning the other species studied,

U. brizantha and

U. decumbens have been previously associated with toxicosis in ruminants; however, to the author’s knowledge, this is the first study reporting diosgenin presence in the hybrid (

U. ruziziensis x

U. decumbens x

U. brizantha). Interestingly, the hybrid can contain even higher diosgenin levels than

U. decumbens or

U. brizantha and the levels found are high enough to suggest that the hybrid could cause hepatic lesions and secondary photosensitization. In previous studies it was suggested that small ruminants can develop acute hepatic cholestasis from ingesting the hybrid grass; however, the diagnosis was only presumptive since no attempts to determine saponin or sapogenin contents were made [

26,

27].

Even though protodioscin and diosgenin are closely related plant metabolites, a previous study showed that protodioscin levels in

Urochloa spp. are higher in the dry season [

12]. This finding is in contrast with the results of the present study where the highest diosgenin levels were found in the rainy season. There is no known explanation for this finding, but one possibility is that under conditions of high humidity, plant saponins are hydrolyzed by enzymes from opportunistic microorganisms, giving rise to diosgenin. In fact, enzymatic hydrolysis has been used for the industrial production of sapogenin from saponins: saponins from

Dioscorea zingiberensis, has been treated with fungi (e.g.,

Trichoderma reesei, Penicillium dioscin or Aspergillus flavus) capable of producing enzymes that generate diosgenin [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Another possibility is that the activity of the enzyme that conjugates sapogenins with sugars in the plant (glucuronosyl tranferases) [

32,

33] decreases at low environmental temperatures, inducing greater levels of saponins in the rainy season.

In summary, Urochloa spp. contain numerous saponins, several of which contain diosgenin; therefore, diosgenin can be considered a better predictor of hepatic disease in herbivorous animals than protodioscin. Due to their diosgenin content it is recommended that to prevent potential intoxications in cattle in the Colombian Eastern Plains, the intake of grasses such as U. decumbens and the hybrid be avoided in the rainy season. Species with lower diosgenin content such as U. dictyoneura, U. humidicola and U. brizantha should be given to the animals during the rainy season.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Region of Study

Besides being the largest livestock producer in the region, the Department of Meta in the Eastern Colombian Plains, has introduced better pastures especially in the area called “piedemonte”, which is the are closest to the east side of Andean mountains and the alluvial valleys [

34]. Weather conditions in this area correspond to a rainfall greater than 3,000 mm/year with a rainy season from April to November and a dry season from December to March.

The sampling areas selected for the present study were two cattle ranches containing pastures of the main Urochloa species (U. brizantha, U. decumbens U. dictyoneura, U. humidicola and U. ruziziensis x U. decumbens x U. brizantha). Farms were located in the “piedemonte” (Villavicencio - latitude: 4,0° 3,0' N longitude: 73,0° 28,0' W) and in the alluvial valley of the Ariari River (San Martín de los Llanos, - latitude: 3,0° 3,7' longitude: 73,0° 44,0'). These farms had previously reported photosensitization cases in cattle.

4.2. Sampling

Urochloa spp. sampling was developed according to the rotation scheme of the region in which pastures are free from animals for approximately 28 days. During this resting period, grass samples were collected at 14

th and 28

th day from three different areas of 1 m

2 in each paddock. Pasture was cut at 2/3 distal mimicking what animals commonly do. Plants were taken from these points under four climatic conditions: early rains with a previous month of precipitation (sampled in April); progressive rains with four preceding months of rainfall (sampled in June); light rains with the minor fall, preceded by a short dry period (sampled in October) and drought without rains (sampled in February). The data corresponding to meteorological factors was obtained from weather stations belonging to the "Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales – IDEAM” [

12].

4.3. Determination and Quantitation of Diosgenin

The extraction and determination of diosgenin was done according to Taylor et al. (2000) [

35]. Once the material was dried and milled, 100 mg were mixed with 5 mL of 80% ethanol. The mix was place in an ultrasonic bath for 2 hours for extraction and then centrifuged at 700

g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was then transferred into a 10 mL glass tube and evaporated under vacuum at 43 °C. The dry residue that remained in the test tube was dissolved with vortex mixing in 2 mL of 70% 2-propanol containing 1 M sulfuric acid. Extracts were then hydrolyzed by heating the mixture at 100 °C for 2 h. After cooling, 3 mL of distilled and deionized water was added, and the solution was then extracted three times with 2 mL of methyl

tert-butyl ether (MBE) using vortex and collecting thef organic phase. The combined MBE extracts were washed twice with 1 mL of 1 M NaOH solution and once with 1 mL of water. To dry the extract, the MBE pool was transferred to an anhydrous MgSO

4 column made with glass pipettes. The dried MBE extract was then evaporated, and the residue dissolved in 1 mL of toluene for further analysis by GC-FID.

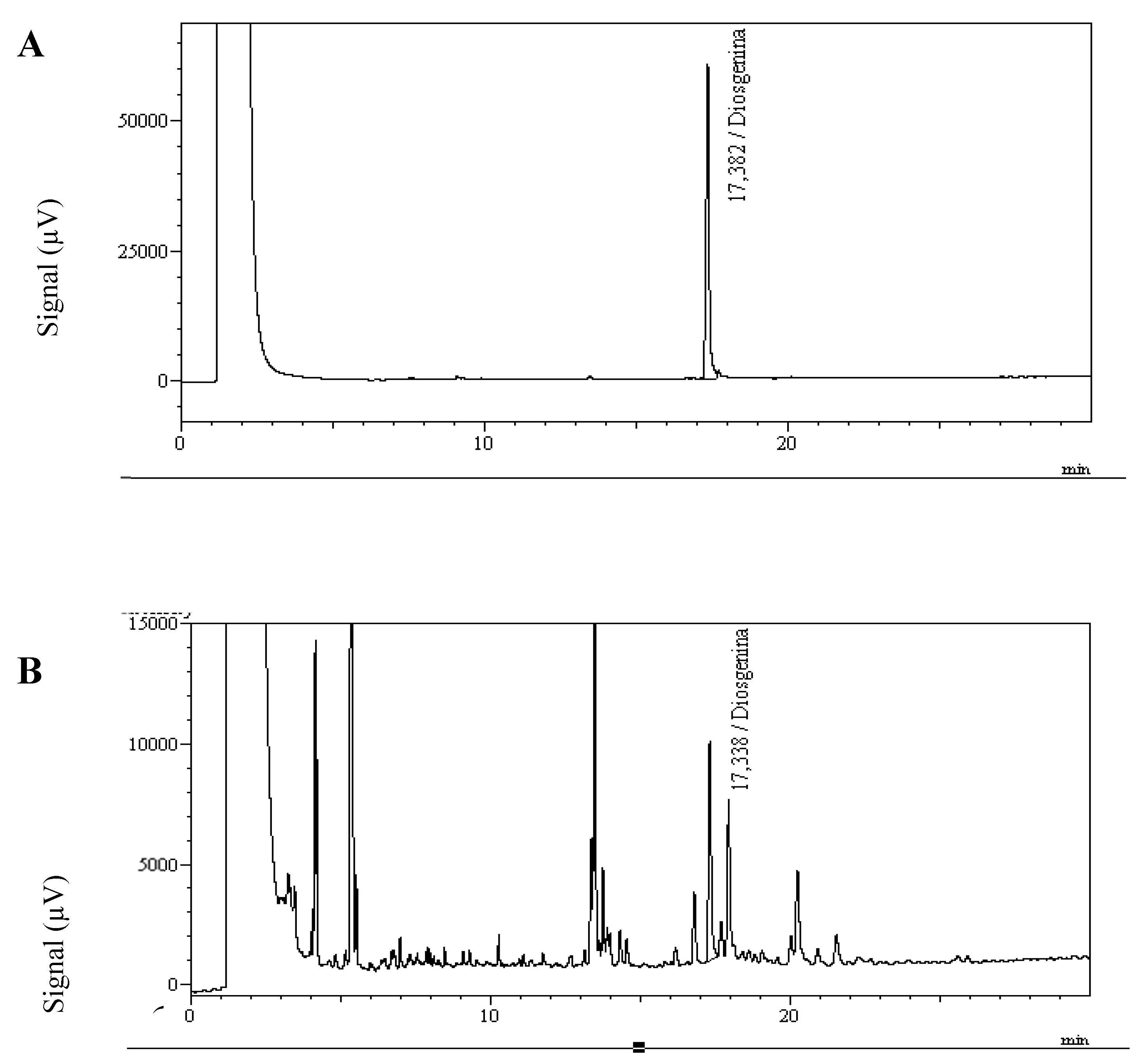

GC was performed with a Shimadzu GC-14A Gas Chromatograph (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID), and a HP-5 fused silica capillary column (Agilent Technologies 19091 S-433UI HP – 5MSUI; 0.25 micron; 30 m x 0.25 mm). The GC split/splitless injection port equipped with a silanized glass liner (HP part 5181-3316) was kept at 250 °C. Two µL of the toluene extracts were injected at an initial oven temperature of 200 °C. After 1 min, the temperature was raised at 10 °C/min to 270 °C and then at 1 °C /min to 290 °C. The carrier gas was helium with a 2 mL/min constant flow under electronic pressure control.

With these parameters the retention time of the diosgenin standard (~ 98% purity) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) was 17.3 minutes (

Figure 4). The method linearity was established with concentrations of 0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 500, 750 and 1000 μg/mL.

Linearity of the detector’s response was confirmed by an r

2 value for the lineal function of 0.996, and a CV (coefficient of variation) of the response factors of 8.5%. The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated at 0.2 μg/mL and the limit of quantitation (LOQ) at 0.6 μg/mL. These in-vial concentrations were equivalent to sample concentrations of 2 and 6 μg/g, respectively. LOD and LOQ values were obtained according to EPA 40 CRF Part 136, Appendix B [

36]. For the determination of the method accuracy the percent recovery was calculated by spiking free hay (from

Digitaria eriantha) at different diosgenin concentrations (10, 25, 50, 500 and 1000 μg/mL) in duplicate. Percent recovery was found to be 65.5% on average, and the results were corrected for recovery by multiplying by a factor of 1.53.

To confirm the identity of diosgenin, GC-MS analysis of samples and standards were conducted. The mass spectra were obtained on a Thermo Scientific TRACE series 1300 GC connected to an ISQ QD single quadrupole mass spectrometer detector equipped with an AL1310 autosampler (Thermo, Massachusetts, USA) in liquid injection mode. The chromatographic conditions used were the same as those for GC-FID. The MS conditions were full-scan mode (m/z 100–500); dwell time 0.2 sec, electron ionization (EI) mode; ionization energy, 70 eV; ion source temperature, 230 °C; interface temperature, 280 °C. Data evaluation was performed using Chromeleon® 7 Chromatography Data System version 7.2.2.6394 software with a NIST 2007 target library. The identity of diosgenin was confirmed by comparing the fragmentation pattern of the diosgenin in the sample extracts with that of the standard (m/z 282,139, 91, 69 and 5).

4.4. Statistical Analyses

The experimental model was a completely randomized 5 x 4 x 2 factorial arrangement to determine which factor (type of pasture, season, and time of re-growth) were most important in grass diosgenin concentration. The model corresponds to five

Urochloa species (

U. brizantha,

U. decumbens,

U. dictyoneura,

U. humidicola and the hybrid -

U. ruziziensis x

U. decumbens x

U. brizantha), four sampling times (initial rains, advanced rains, light rains and droughty) and two post-cutting times (14 and 28 days). Each farm results (one from “piedemonte” and the other from alluvial valley) were analyzed separately using this experimental design. The goal was oriented on finding potential changes between species at the same sampling time, between sampling times for the same species and between regrowth time for the same grass species and sampling time. According to the O'Brien test the model satisfied the supposition of homogeneity of variances [

37].

Additionally, for identifying the possible effect of the environmental factors on diosgenin content Pearson's correlations were estimated between the weather variables (temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and solar brightness) and diosgenin content. This analysis was applied for all data, as well as for each of the regions, post-cutting time and particular Urochloa species. The statistical analysis was done using SAS 9.2 software, accepting a significance of P<0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.L. and G.J.D.; methodology, M.C.L., formal analysis, M.C.L..; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.L.; writing—review and editing, G.J.D.; supervision, G.J.D..; resources, M.C.L. and G.J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by MINCIENCIAS (Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation) through grant No. 1101-452-21116,.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to CORPOICA - Villavicencio (Colombian Corporation for Agricultural Research) and EMBRIOVET for their support with the sampling of Urochloa spp.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ICA. Censos Pecuarios Nacional 2024; ICA: Bogotá, Colombia. Available online: https://www.ica.gov.co/areas/pecuaria/servicios/epidemiologia-veterinaria/censos-2016/censo-2018 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Lozano, M. C.; Doncel, B.; Moreno, C. A. Manual de plantas tóxicas para bovinos. Región Llanos Orientales de Colombia: Meta y Casanare; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, G. J. Plantas tóxicas de importancia en salud y producción animal en Colombia; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, C.; Driemeier, D.; Pires, V.; Colodel, E.; Daketa, A. Isolation of steroidal sapogenins implicated in experimentally induced cholangiopathy of sheep grazing Brachiaria decumbens in Brazil. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. 2000, 42, 142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, C.; Driemeier, D.; Pires, V.; Schenkel, E. Experimentally induced cholangiohepatopathy by dosing sheep with fractionated extracts from Brachiaria decumbens. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2001, 13, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brum, K.; Haraguchi, M.; Lemos, R.; Riet-Correa, F.; Fioravanti, M. Crystal-associated cholangiopathy in sheep grazing Brachiaria decumbens containing the saponin protodioscin. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2007, 27, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, C.; Wilkins, A.; Munday, S.; Holland, P.; Smith, B.; Lancaster, M. Identification of the calcium salt of epismilagenin β-D-glucuronide in the bile crystals of sheep affected by Panicum dichotomiflorum and Panicum schinzii toxicoses. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992, 40, 1606–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, C.; Wilkins, A.; Munday, S.; Flayoen, A.; Holland, P.; Smith, B. Identification of insoluble salts of the β-D-glucuronides of episarsasapogenin and epismilagenin in the bile of lambs with alveld and examination of Narthecium ossifragum, Tribulus terrestris, and Panicum miliaceum for sapogenins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1993, 41, 914–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysterud, I.; Flåøyen, A.; Loader, J. I.; Wilkins, A. L. Sapogenin levels in Narthecium ossifragum plants and Ovis aries lamb feces during two alveld outbreaks in Møre og Romsdal, Norway, 2001. Vet. Res. Commun. 2007, 31, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riet-Correa, B.; Castro, M. B.; De Lemos, R. A.; Riet-Correa, G.; Mustafa, V.; Riet-Correa, F.; Lemos, R. Brachiaria spp. poisoning of ruminants in Brazil. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2011, 31, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F. G.; Haraguchi, M.; Pfister, J. A.; Guimaraes, V. Y.; Diogo, D. F. Weather and plant age affect the levels of steroidal saponin and Pithomyces chartarum spores in Brachiaria grass, main forage source for ruminants. IJPPR. 2012, 2, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, M. C.; Martinez, N. M.; Diaz, G. J. Content of the Saponin Protodioscin in Brachiaria spp. from the Eastern Plains of Colombia. Toxins 2017, 9, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, M. C. M.; Ítavo, L. C. V.; Ítavo, C. C. B. F.; Dias, A. M.; Dos Santos Difante, G.; Buschinelli de Goes, R. H. T.; de Souza Leal, E.; Nonato, L. M.; Kozerski, N. D.; de Moraes, G. J.; Niwa, M. V. G.; Gurgel, A. L. C.; de Souza Arco, T. F. F. Natural Intoxication Caused by Protodioscin in Lambs Kept in Brachiaria Pastures. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, P.; Diaz, G. J.; Cárdenas, E.; Lozano, M. C. Ethnobotanical study of plants poisonous to cattle in Eastern Colombia. IJPPR. 2002, 2, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gracindo, C. V.; Louvandini, H.; Riet-Correa, F.; Barbosa-Ferreira, M.; Botelho De Castro, M. Performance of sheep grazing in pastures of Brachiaria decumbens, Brachiaria brizantha, Panicum maximum, and Andropogon gayanus with different protodioscin concentrations. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2014, 46, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, J. C. S.; Difante, G. D. S.; Rodrigues, J. G.; Pereira, M. G.; Fernandes, H. J.; Ítavo, C. C. B. F.; Longhini, V. Z.; Dias, A. M.; Ítavo, L. C. V. Mathematical Models for Predicting Protodioscin in Tropical Forage Grasses. Toxicon 2024, 240, 107628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, L.; Wilkins, A.; Miles, C.; Fagliari, J. Hepatogenous photosensitization of ruminants by Brachiaria decumbens and Panicum dichotomiflorum in the absence of sporidesmin: lithogenic saponins may be responsible. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. 1996, 38, 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, V. S.; Taketa, A. T. C.; Gosmann, G.; Schenkel, E. P. Saponins and sapogenins from Brachiaria decumbens Stapf. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2002, 13, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Mitchell, R.; Gardner, D.; Tokarnia, C.; Riet-Correa, F. Measurement of steroidal saponins in Panicum and Brachiaria grasses in the USA and Brazil. In Riet-Correa, F.; Pfister, J., Schild, A. L., Wierenga, T. (Eds.), Poisoning by Plants, Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011; pp. 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, D. R.; Nepomuceno, D. D.; Castro, R. N.; Braz, R. F.; Carvalho, M. G. Special Metabolites Isolated from Urochloa humidicola (Poaceae). An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2017, 89, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S. Signal grass (Brachiaria decumbens) toxicity in grazing ruminants. Agriculture 2015, 5, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Debnath, B.; Qasim, M.; Bamisile, B. S.; Islam, W.; Hameed, M. S.; Wang, L.; Qiu, D. Role of saponins in plant defense against specialist herbivores. Molecules 2019, 24, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciura, J.; Szeliga, M.; Tyrka, M. Optimization of in vitro culture conditions for accumulation of diosgenin by fenugreek. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2015, 3, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kono, I. S.; Faccin, T. C.; Amorim de Lemos, G. A.; Di Santis, G. W.; Bacha, F. B.; Guerreiro, Y. A.; de Oliveira Gaspar, A.; Lee, S. T.; de Castro Guizelini, C.; Leal, C. B.; Amaral de Lemos, R. A. Outbreaks of Brachiaria ruziziensis and Brachiaria brizantha Intoxications in Brazilian Experienced Cattle. Toxicon 2022, 219, 106931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G. Saponins in Sub-Tropical Grasses in WA; Government of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2014; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chong Dubé, D.; Figueredo, J. M.; Percedo, M. I.; Domínguez, P.; Martínez-García, Y.; Alfonso, P.; Marrero-Faz, E. Toxicosis por pasto Mulato (Brachiaria ruziziensis - Brachiaria brizantha) en cabras de la provincia Artemisa. Rev. Salud Anim. 2016, 38, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, R. E.; Gimeno, E. J.; Riet-Correa, F.; Uzal, F. A. Hepatic and Renal Lesions in Sheep Intoxicated with Urochloa Hybrid Mulato II in Argentina. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2024, 36, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dong, Y.; Chi, Y.; He, Q.; Wu, H.; Ren, Y. Eco-friendly microbial production of diosgenin from saponins in Dioscorea zingiberensis tubers in the presence of Aspergillus awamori. Steroids 2018, 136, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Yu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, B. Evaluation of different pretreatments on microbial transformation of saponins in Dioscorea zingiberensis for diosgenin production. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2014, 28, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Lei, C.; Lu, D.; Wang, Y. Direct biotransformation of dioscin into diosgenin in rhizome of Dioscorea zingiberensis by Penicillium dioscin. Indian J. Microbiol. 2015, 55, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Pan, L.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Mou, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, L.; Qin, B.; Hu, Z. The Isolation, Identification and Immobilization Method of Three Novel Enzymes with Diosgenin-Producing Activity Derived from an Aspergillus flavus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, H.; Tamura, K.; Muranaka, T. P450s and UGTs: Key players in the structural diversity of triterpenoid saponin. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 1436–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haralampidis, K.; Trojanowska, M.; Osbourn, A. E. Biosynthesis of triterpenoid saponins in plants. In Scheper, T. (Ed.), History and Trends in Bioprocessing and Biotransformation; Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, J. I.; Romero, M.; Rivero, S. T.; Duarte, O. A.; Gómez, P. J.; Vanegas, E.; Jaime, W. E.; Parra, J. L.; Pérez, R. A.; Cipagauta, M.; Gómez, J. E.; Velásquez, J. E.; García, J.; Gutiérrez, A.; Narváez, L. Atlas de los Sistemas de Producción Bovina. Módulo Orinoquía y Amazonía; CORPOICA: Bogotá, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, W. G.; Elder, J. L.; Chang, P. R.; Richards, K. W. Microdetermination of diosgenin from fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 5206–5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPA. 40 CFR Appendix B to Part 136—Definition and Procedure for the Determination of the Method Detection Limit-Revision 1.11. EPA Code of Federal Regulations; Government Printing Office: USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, R.; Martínez, N. N.; Martínez, M. V. Diseño de Experimentos en Ciencias Agropecuarias y Biológicas con SAS, SPSS, R Y STATISTIX; Fondo Nacional Universitario: Bogotá, Colombia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).