1. Introduction

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a cost-effective therapy for treating kidney failure, offering advantages over in-center hemodialysis in terms of patient autonomy, reduced costs, and improved outcomes.[

1,

2] Well-functioning medical devices (MDs), such as PD catheters and transfer sets, are crucial for successful PD therapy. These devices enable adequate dialysis, and their proper function is associated with fewer complications, greater patient independence, and better clinical outcomes.

However, complications related to MDs can lead to significant adverse events, including the interruption or discontinuation of PD therapy, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and the need for invasive procedures. Examples of such complications include catheter flow obstruction (also referred to as dysfunction or loss of patency), exit-site leaks, and abdominal pain, which are common PD catheter insertion-related issues.

Current surveillance of MD performance and complications relies largely on passive reporting, which is limited by its voluntary nature and the lack of comprehensive exposure data.[

3] To address these limitations, there has been growing interest in using claims and electronic health record (EHR) data to evaluate MDs’ safety and effectiveness. In 2015, the North American Chapter of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis established the North American PD Catheter Registry, a web-based platform to monitor patients undergoing laparoscopic PD catheter insertion.[

4] This type of implant registry provides valuable information that enhances patient safety.[

5,

6] However, maintaining large registries can be challenging when complication rates are low and long-term follow-up is required.

An alternative approach for active surveillance is to use a common data model (CDM). A CDM is a logical and semantic data framework that standardizes multiple data sources into a common format, enabling more consistent data analysis.[

7] To date, no studies have reported on CDM-based active surveillance of MDs adverse events.

This study was conducted as a preliminary investigation into the feasibility of using CDM-based active surveillance to detect PD-related complications and MD data. The goal was to evaluate whether CDM can effectively identify various PD complications and provide valuable insights into MDs performance.

2. Materials and Methods

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (SCHBC; IRB No. SCHBC 2021-05-002). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.[

8]

2.1. Medical Records According to the Clinical Course of PD Patients

A retrospective chart review was conducted on patients who underwent PD catheter insertion between January 2001 and March 2021. The review evaluated medical records, including PD-related procedures, MD usage, and complication diagnoses. Various procedures related to the overall course of PD were listed, and the corresponding electronic data interchange (EDI) codes were identified for each procedure. Among the PD-related MDs used at SCHBC, usage records for adapters, Tenckhoff catheters, and transfer sets were reviewed. The follow-up period was calculated from the insertion date of the initial catheter to the removal date or June 30, 2021, whichever came first. The occurrence of the following seven PD-related complications was reviewed: peritonitis, exit-site infection (ESI), tunnel infection (TI), outflow failure, peri-catheter leak, cuff shaving, abdominal herniation, and catheter cuff extrusion.

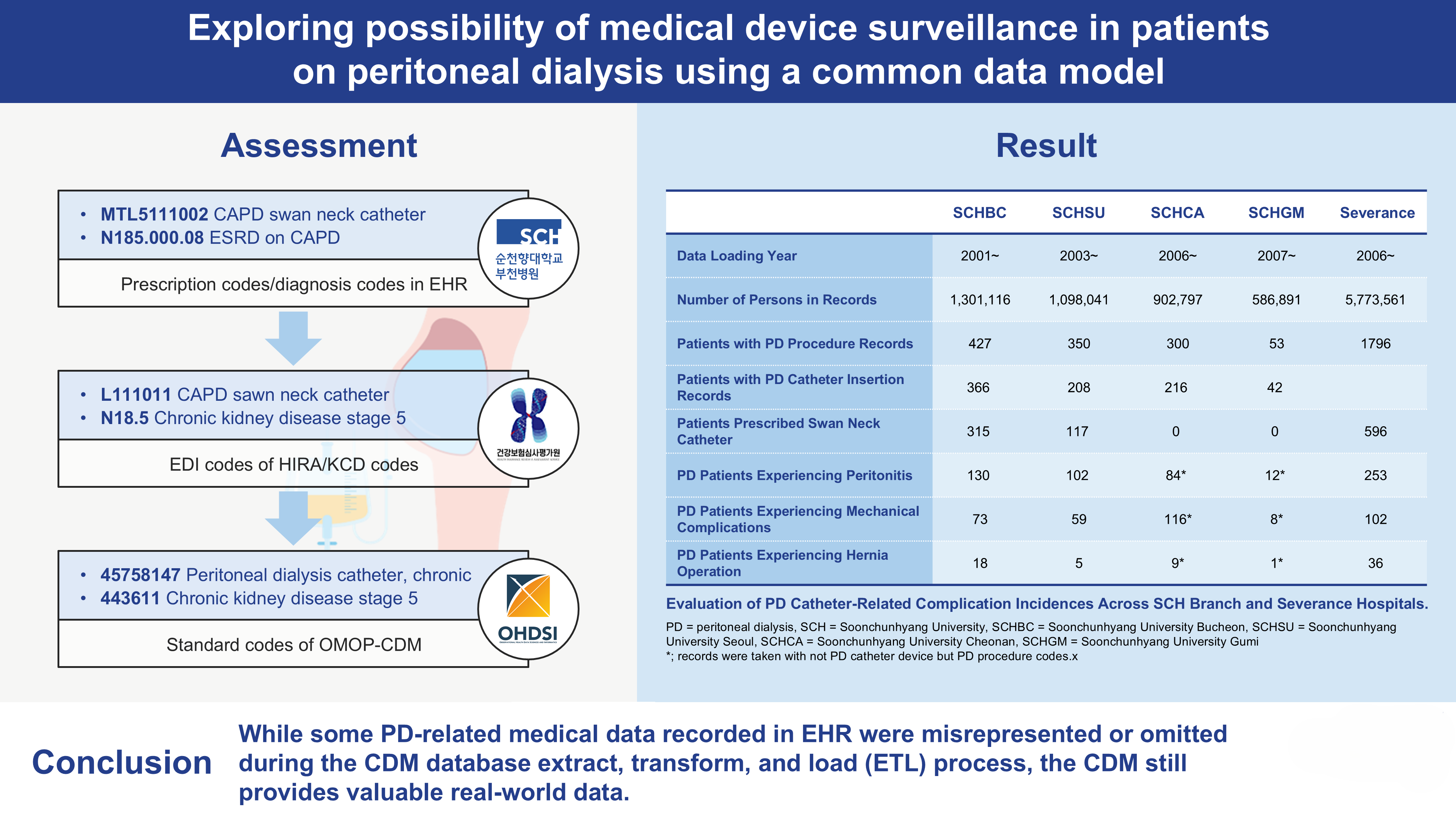

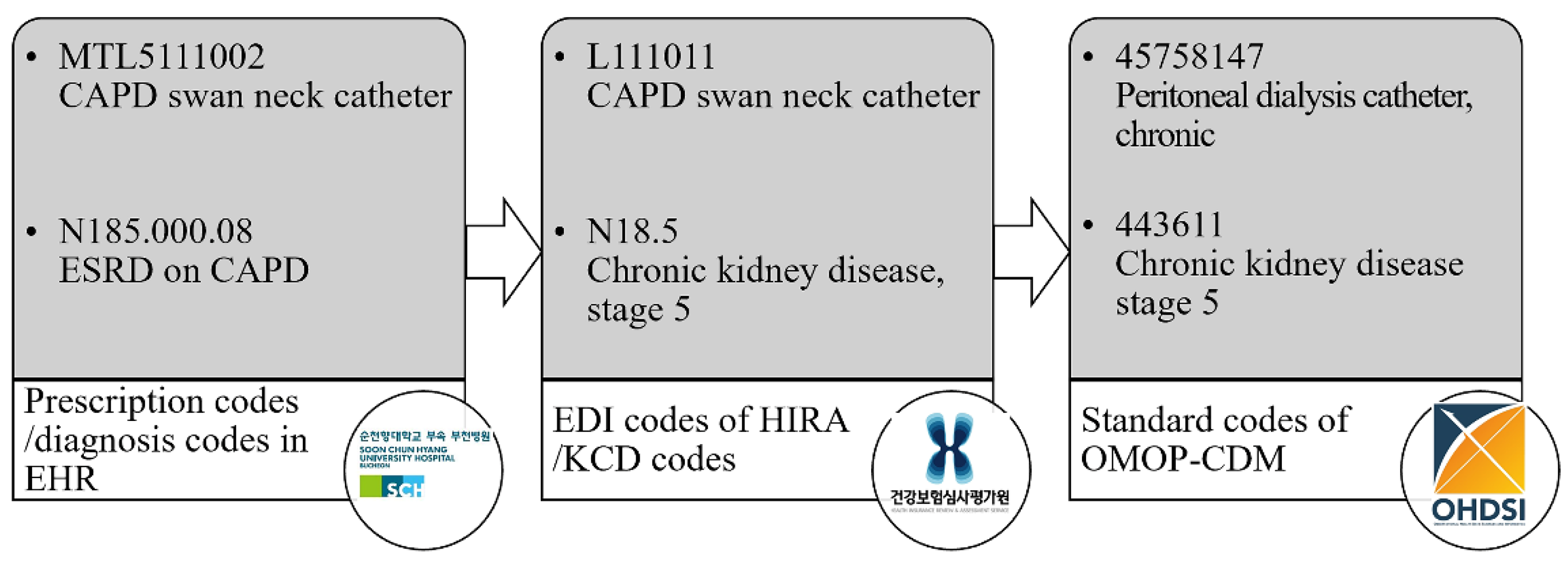

2.2. CDM Mapping Status of Medical Records

After reviewing the medical records, diagnostic, procedure, and treatment material codes were evaluated for their mapping to the CDM. SCHBC’s diagnostic coding is based on the Korean Standard Classification of Disease (KCD). However, lower-level codes may be registered at a more detailed level than the minimum classification unit of the KCD due to requests from medical staff who prefer more precise diagnostic descriptions. The procedure and treatment material codes were institution-specific codes corresponding to the EDI codes used by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA). These data were converted to the source name ‘cdmpv531_0920_bucheon’ using the Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics open-source software and the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP)-CDM version 5.3 database (

Figure 1). The mapping status of each code in the CDM was provided at ’

https://feedernet.com/conceptid’. The Central Vocabulary Service, Athena (

http://athena.ohdsi.org), was used to search for the most appropriate CDM code for each medical record.

2.3. Evaluation of the Adequacy of SCH Branches and Severance Databases for Monitoring PD Catheter-Related Adverse Events Leading to Peritonitis

Soonchunhyang (SCH) University operates four hospitals located in Seoul (SCHSU), SCHBC, Cheonan (SCHCA), and Gumi (SCHGM). These hospitals share the same EHR system and data through the OMOP-CDM.

To evaluate whether the CDM databases of SCH branches can be effectively utilized to monitor the incidence of PD catheter-related adverse events, we conducted an analysis of PD catheter-related information and peritonitis occurrences recorded in these databases. This involved a comparative analysis in which data from SCHBC was compared with that of the other branches — SCHSU, SCHCA, and SCHGM — to assess PD catheter utilization and the recorded instances of peritonitis among patients with PD procedure records.

For external validation, we evaluated the query for complications using the database from another hospital, Severance.

3. Results

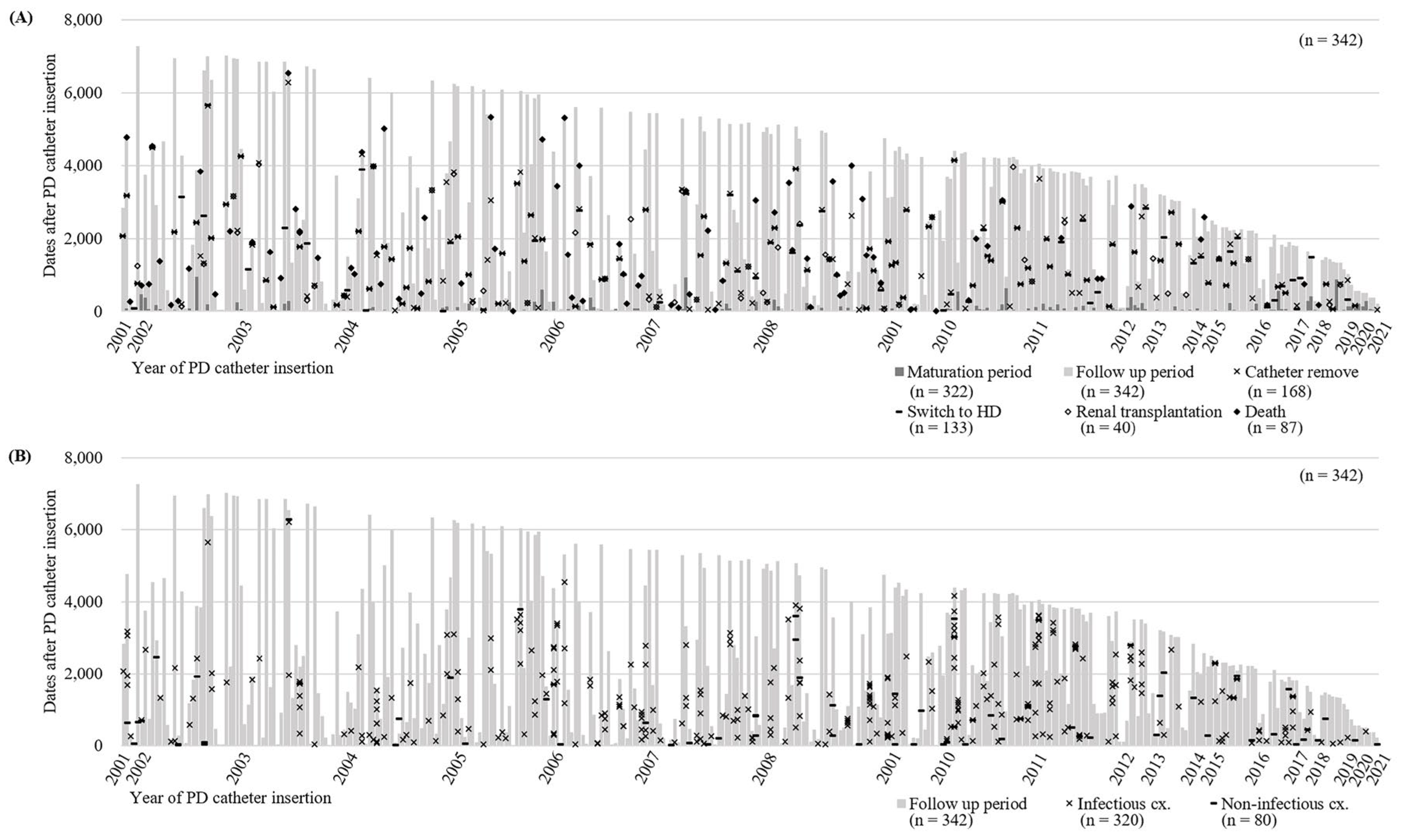

3.1. Clinical Course of PD

A total of 342 patients who underwent PD catheter insertion at SCHBC were reviewed. Among them, 21 patients did not initiate PD, while 321 patients proceeded with externalization of the PD catheter and began PD after a mean of 74.6 days. During the follow-up period of 1,378.0 ± 95.1 days, 168 patients had their catheters removed (

Figure 2A). A total of 133 patients transitioned to hemodialysis, and 40 patients underwent kidney transplantation. Among these patients, 87 passed away (

Figure 2A). Of the 342 patients, 195 experienced complications more than once, with 320 cases of infectious complications and 80 cases of non-infectious complications reported (

Figure 2B). Infectious complications, including 257 cases of peritonitis, 55 ESI, and 8 tunnel site infections, were recorded in 162 patients. Eighty non-infectious complications occurred in 65 patients. Cuff shaving, herniorrhaphy, and leak management were the most frequently performed interventions.

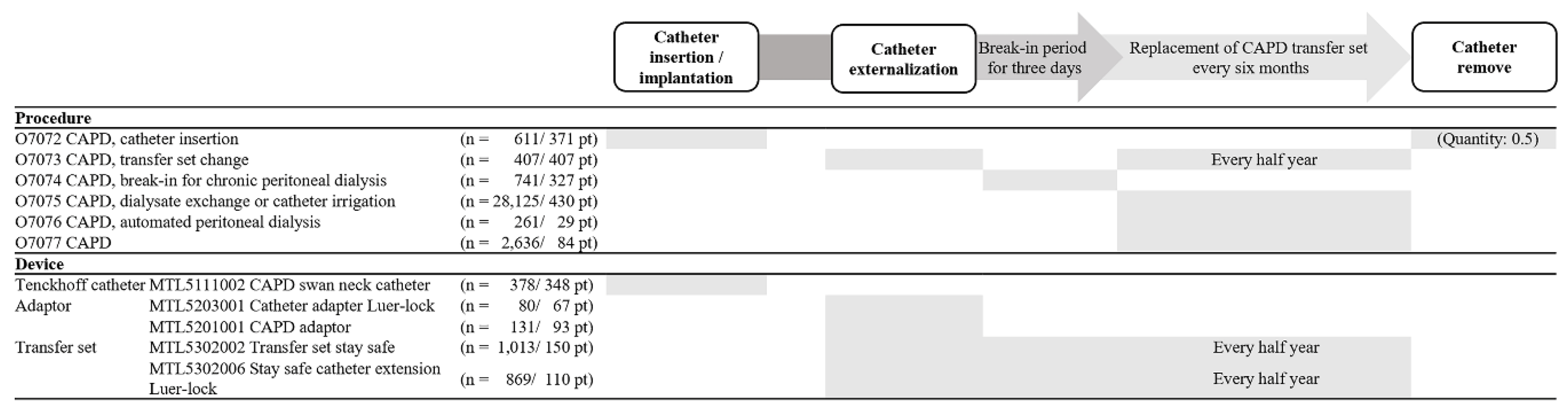

3.2. PD-Related Codes Recorded in EHR

Among the 11 procedures related to the overall course of PD, only 6 EDI codes were extracted (

Figure 3 and

Supplementary Table 1, only online). Additionally, only 5 codes were identified among the 12 nationwide therapeutic materials for PD-related MDs. A total of 8 diagnostic codes related to PD complications were recorded at SCHBC.

Figure 3 illustrates the clinical progress of PD and the records of PD-related procedures and MD EDI codes. Although catheter insertion and removal are distinct medical procedures, the O7072 code was used for both because no separate EDI code exists for catheter removal. Consequently, catheter removal was recorded under the O7072 code with a claim quantity of 0.5 to account for the difference in procedure complexity. While transfer set changes were performed every 6 months or when complications occurred, the same code (O7073) was used for both routine and complication-driven changes. The code for transfer sets (MTL5302002 or MTL5302006) was entered along with the procedure code (O7073) every 6 months, while the code for the adapter (MTL5203001 or MTL5201001) was only recorded during the initial replacement of the CAPD transfer set. The code O7075, which is no longer used, was the most frequently entered code until June 2017, with 28,125 entries in 430 patients. Codes O7076 and O7077 have been in use since July 2017.

3.3. Comparison of First Complication Events in SCHBC by Chart Review and CDM (Table 1)

Infectious complications, including 132 cases of peritonitis, 41 cases of ESI, and 8 cases of TI, were detected in the chart review. However, only 127 cases of peritonitis were detected by the CDM. Mechanical complications such as granulation, cuff shaving, leaks, repositioning, malfunction, appendectomy, pleural-peritoneal shunts, tears, and pancreatitis were not detected by the CDM. The reported deaths also differed between the chart review and CDM.

3.4. Comparative Analysis of PD Catheter-Related Complications Across SCH Branch Hospitals and Severance Hospital

The number of patients with PD procedure records was highest at SCHBC, with 427 individuals, followed by SCHSU and SCHCA, with 350 and 300 individuals, respectively. SCHGM had the fewest, with 53 individuals. SCHBC also recorded the highest number of PD catheter insertion cases, with 366 instances representing 85.7% of patients with PD procedure records. SCHBC also documented 315 cases of swan neck catheter prescriptions, accounting for 73.8% of its PD procedure population. In contrast, SCHSU recorded 117 cases, representing 33.4% of its PD procedure group. SCHCA and SCHGM reported no cases of swan neck catheter prescriptions. Therefore, complication occurrence data were based on PD procedures rather than catheter prescriptions in SCHCA and SCHGM.

The incidence of peritonitis, mechanical complications, and hernias following PD procedures was documented and compared. SCHBC had the highest number of peritonitis cases, with 130, representing a 30.4% incidence rate. SCHSU and SCHCA reported 102 and 84 cases, with incidence rates of 29.1% and 28.0%, respectively. SCHGM had the lowest rate, with 12 cases and a 22.6% incidence rate among its PD procedure population.

These queries were further evaluated using data from Severance Hospital. Unlike at SCH University Hospital branches, specific PD catheter insertion codes were not identified. However, codes for associated complications, both infectious and noninfectious, were available (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

Real-world data such as electronic medical records (EMR) and claims data are widely used in observational studies. However, many EMR datasets are inconsistent across hospitals and can be difficult to access, making large-scale research challenging. One proposed solution to this issue is the OMOP-CDM, which has been adopted by many hospitals for standardization.[

9,

10,

11,

12]

Research using CDM has the advantage of allowing access to large datasets with minimal effort and cost. Additionally, CDM provides anonymized data by removing personally identifiable information, ensuring privacy protection.

Some researchers have demonstrated that analyzing EMR data using standardized methods is cost-effective and supports proactive surveillance by physicians. This study builds upon previous research, showing that even when standardized through the CDM, EMR data can be utilized for active surveillance of MD adverse events.[

13,

14] While this study demonstrated the feasibility of using CDM for the active surveillance of specific limited MDs, such as PD catheters, several limitations remain.

First, there are limitations related to patient symptoms and diagnoses. When physicians enter diagnostic information into EMR systems, they are often required to select from diagnostic terms provided by the hospital. Although these terms are believed to be standardized because they are used in reimbursement claims in the Korean healthcare system, many hospitals still use custom, subdivided codes rather than the KCD or International Classification of Diseases (ICD). This discrepancy in both database structures and codes complicates data analysis via EMR and requires additional mapping during the extract, transform, and load (ETL) process, as the information may not conform to KCD or ICD standards.

Moreover, diagnoses are often not entered during care, and diagnostic input can vary between medical personnel, even in identical situations. For instance, in the case of peritonitis (

Supplementary Table 1, only online), several diagnostic codes from KCD-7, such as [K65.0] Acute peritonitis, [K65.8] Other peritonitis, [K65.9] Peritonitis unspecified, [K91.8] Other postprocedural disorders of the digestive system, NEC, and [T85.7] Infection and inflammatory reaction due to other internal prosthetic devices, implants, and grafts, may be used. This situation becomes more complex when hospitals add additional subdivisions to these diagnoses, making standardization difficult and hindering the ability to conduct accurate data analysis.

Additionally, while the CDM’s CONDITION_OCCURRENCE table can include both KCD/ICD diagnoses and clinical findings, the transformation of these findings is limited (

Supplementary Table 2, only online). It is recommended to input precise diagnoses rather than symptoms when entering diagnostic codes. Therefore, when diagnosis codes are ETL-ed, analyzing patient symptoms becomes challenging. Extracting symptoms from EMR charts is further complicated by variations in the formatting of entries by individual recorders, with formats varying over time and by situation, even within the same practitioner. While advances in large language models may assist with text mining from EMR data, extracting vast amounts of data from multiple hospitals requires further research.

The second limitation lies in the surveillance of MDs through EDI codes. The Korean reimbursement code system (EDI) is not comprehensive for all procedures.[

14] For instance, while there is an EDI code for PD catheter insertion, no code exists for its removal (

Figure 3 and

Supplementary Table 1, only online). At our institution, we have made a makeshift solution by recording insertion as a quantity of 1 and removal as 0.5 in the EHR. However, without an EDI code, accurate records may not be kept across hospitals. Similarly, procedures related to PD catheter irrigation and cuff shaving also lack EDI codes. For large-scale surveillance to be feasible in the future, the related procedures need to be clearly defined and included in reimbursement codes through collaboration between medical societies and government agencies.

This study used EDI codes for PD catheter surveillance, as the CDM does not yet support unique device identification (UDI) conversion. However, since EDI codes are primarily designed for reimbursement purposes, many MDs are grouped under a single EDI code, which limits their use in MD surveillance.[

15,

16,

17] A potential improvement would be to include UDIs in the CDM, allowing for more precise comparisons between MDs. Starting with CDM version 5, the device_exposure table was added, enabling the ETL process for UDIs in the unique_device_id column. In version 5.3, the allowable size of this field was increased from varchar(50) to varchar(255), allowing for more detailed entries, and from version 5.4, the production_id column was added to support UDI-DI and UDI-PI entries. While research using UDI for MD surveillance has yet to be reported (

Supplementary Figure 1, only online), completing the ETL process for UDI-device identifier (UDI-DI) and UDI-production identifier (UDI-PI) would enable more accurate post-market surveillance of MDs. Although UDI-DI, limited to 25 characters, would pose no issue under version 5.4, UDI-PI, which typically involves product barcodes, could exceed the 255-character limit if too much information is included. Further research will be necessary to address these issues, including the input range for UDI-PI and the addition of extra columns.

Finally, Korea has limitations regarding ETL and CDM operations due to the government’s outsourcing of these tasks to specific companies. At Soonchunhyang University, for instance, ETL was implemented through a government project with FeederNet (

Supplementary Table 1, only online). While this has enabled many hospitals to adopt CDM, there are limitations as the transformation is led by government initiatives rather than by hospitals or researchers. Mapping tables for each hospital are not publicly available, and the accuracy of mapping may vary depending on the level of interest of each researcher. Furthermore, as government projects drive the conversion, there are limitations in updating mappings or conducting additional ETL without further funding. For example, a separate project was needed to perform additional conversions of EDI codes at our institution. It would be ideal if more clinicians were interested in CDM and participated in the ETL process, allowing for more accurate and comprehensive ETL, including UDI entries. Collaboration between hospitals and companies or independent CDM construction at the hospital level could enable continuous updates and improvements.

Despite these numerous limitations, this study is significant in demonstrating the feasibility of MD surveillance using CDM. It is hoped that this study will serve as a foundation for establishing an environment where, through UDI-DI and UDI-PI conversion in CDM versions beyond 5.4, post-market surveillance can be performed based on detailed device information, such as lot numbers and expiration dates, rather than relying solely on EDI and procedure-based surveillance.

5. Conclusions

This study is significant in demonstrating the feasibility of medical device surveillance using CDM. Future discussions regarding UDI-DI, UDI-PI, and standardized diagnostic inputs would likely contribute to more precise post-market surveillance in real-world settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.K.L. and J.K.K. Methodology: S.M.K., S.C., S.J.C., and Y.K.L. Investigation: S.C., C.W.L., and S.J.C. Formal analysis: S.M.K., S.C., and S.J.C. Writing – original draft preparation: S.M.K, S.C., and S.J.C. Writing – review and editing: S.M.K., S.C., Y.K.L., C.W.L., B.C.Y., M.Y.P., J.K.K., S.C.Y., S.J.S., and S.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Soonchunhyang University Research Fund and by 2020 research grant funded by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Republic of Korea (grant number, 21173-MFDS-245).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (SCHBC; IRB No. SCHBC 2021-05-002, date of approval: 06 May 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived from the IRB due to the retrospective design.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PD |

Peritoneal dialysis |

| MD |

Medical device |

| CDM |

Common data model |

| EHR |

Electronic health records |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| STROBE |

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| EDI |

Electronic data interchange |

| HIRA |

Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service |

| KCD |

Korean Standard Classification of Disease |

| CAPD |

Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis |

| ESRD |

End-stage renal disease |

| OMOP |

Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership |

| OHDSI |

Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics |

| SCH |

Soonchunhyang |

| SCHBC |

Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital |

| SCHSU |

Soonchunhyang University Seoul |

| SCHCA |

Soonchunhyang University Cheonan |

| SCHGM |

Soonchunhyang University Gumi |

| HD |

Hemodialysis |

| EMR |

Electronic medical records |

| ICD |

International Classification of Diseases |

| ESI |

Exit-site infection |

| TI |

Tunnel infection |

| ETL |

Extract, transform, and load |

| UDI |

Unique device identification |

| UDI-DI |

UDI-device identifier |

| UDI-PI |

UDI-production identifier |

References

- Borzych-Duzalka, D.; Aki, T.F.; Azocar, M.; White, C.; Harvey, E.; Mir, S.; Adragna, M.; Serdaroglu, E.; Sinha, R.; Samaille, C.; et al. Peritoneal dialysis access revision in children: causes, interventions, and outcomes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree, J.H.; Shrestha, B.M.; Chow, K.M.; Figueiredo, A.E.; Povlsen, J.V.; Wilkie, M.; Abdel-Aal, A.; Cullis, B.; Goh, B.L.; Briggs, V.R.; et al. Creating and maintaining optimal peritoneal dialysis access in the adult patient: 2019 update. Perit. Dial. Int. 2019, 39, 414–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.J.; Nam, K.C.; Choi, S.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, Y.K.; Kwon, B.S. The establishment of the Korean medical device safety information monitoring center: Reviewing ten years of experience. Health Policy 2021, 125, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, M.J.; Perl, J.; McQuillan, R.; Blake, P.G.; Jain, A.K.; McCormick, B.; Yang, R.; Pirkle, J.L., Jr.; Fissell, R.B.; Golper, T.A.; et al. Quantifying the risk of insertion-related peritoneal dialysis catheter complications following laparoscopic placement: Results from the North American PD Catheter Registry. Perit. Dial. Int. 2020, 40, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paxton, E.W.; Inacio, M.C.; Kiley, M.L. The Kaiser Permanente implant registries: effect on patient safety, quality improvement, cost effectiveness, and research opportunities. Perm J 2012, 16, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnic, F.S.; Majithia, A.; Marinac-Dabic, D.; Robbins, S.; Ssemaganda, H.; Hewitt, K.; Ponirakis, A.; Loyo-Berrios, N.; Moussa, I.; Drozda, J.; et al. Registry-based prospective, active surveillance of medical-device safety. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FitzHenry, F.; Resnic, F.S.; Robbins, S.L.; Denton, J.; Nookala, L.; Meeker, D.; Ohno-Machado, L.; Matheny, M.E. Creating a common data model for comparative effectiveness with the observational medical outcomes partnership. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2015, 6, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberson, A.; Rinner, C.; Schöberl, A.; Gall, W. Feasibility of mapping Austrian health claims data to the OMOP common data model. J. Med. Syst. 2019, 43, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, N.; Zhang, N.; Wu, H.; Lu, S.; Yu, Y.; Hou, L.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, G. Preliminary exploration of survival analysis using the OHDSI common data model: a case study of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamer, A.; Depas, N.; Doutreligne, M.; Parrot, A.; Verloop, D.; Defebvre, M.M.; Ficheur, G.; Chazard, E.; Beuscart, J.B. Transforming French electronic health records into the observational medical outcome partnership’s common data model: a feasibility study. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2020, 11, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- You, S.C.; Lee, S.; Choi, B.; Park, R.W. Establishment of an international evidence sharing network through common data model for cardiovascular research. Korean Circ J 2022, 52, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, J.K.; Nam, K.C.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.K. Preliminary feasibility assessment of CDM-based active surveillance using current status of medical device data in medical records and OMOP-CDM. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, J.K.; Yoon, C.; Nam, K.C.; Kwon, B.S.; Lee, Y.K. Which health impacts of medical device adverse event should be reported immediately in Korea? J Patient Saf 2022, 18, e591–e595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, E.J.; Park, H.A.; Sohn, S.K.; Lee, H.B.; Choi, H.K.; Ha, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, T.W.; Youm, W. Mapping Korean EDI medical procedure code to SNOMED CT. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 264, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Korea Health Information Service. Healthcare information standard. Available online: https://hins.or.kr/ (accessed on November 1 2024).

- You, S.C.; Lee, S.; Cho, S.Y.; Park, H.; Jung, S.; Cho, J.; Yoon, D.; Park, R.W. Conversion of national health insurance service-national sample cohort (NHIS-NSC) database into observational medical outcomes partnership-common data model (OMOP-CDM). Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 245, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).