Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

27 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

6.1. Introduction

6.1.1. Background

6.1.2. Aims and Objectives

- i.

- Introduce a robust optimisation algorithm that is capable of producing pile designs with the lowest embodied carbon for different soil conditions and pile capacities.

- ii.

- Deploy the optimisation algorithm to discover the optimal design of six different pile types; concrete solid, concrete hollow, steel pipe, steel universal column section (UC), timber rounded and timber square in a range of common soil types.

- iii.

- Compare the characteristics of optimal tension piles to optimal compression piles, in order to provide generalised design guidance.

- iv.

- Apply the optimisation algorithm to an existing case study to assess the potential carbon saving for a built structure for future endeavours.

6.1.3. Analysis Setup

- a)

- Optimising the embodied carbon of tension piles in undrained clay soil: Concrete, steel, and timber piles with capacities up to 3 MN are designed in undrained clay conditions. The optimal design parameters for each material type are determined and compared.

- b)

- Optimising the embodied carbon of tension piles in loose sand: Concrete, steel, and timber piles are designed for capacities up to 3 MN in loose sand conditions, and the optimal design parameters are compared.

- c)

- Comparative analysis: A broad discussion is provided to compare the optimal design options for both compression and tension piles in different soil types.

- d)

- Case study: A real-world case study of an existing tension pile design is presented in detail. The parameters from the built piles are fed into the optimisation algorithm to generate an alternative optimal pile design.

6.2. Methodology

6.2.1. Pile Capacities and Soil Types

- -

- Structural capacity: the pile resistance as a structural element subjected to pure tensile stresses is within a safe limit.

- -

- Geotechnical capacity: the factored pile’s frictional resistance is less than the applied tensile load.

6.2.1.1. Structural capacity

- and = steel cross-sectional area and timber cross-sectional area

- = characteristic compressive strength of timber and steel.

- = partial factor for timber compressive strength = 1.3 (British Standards Institute, 2002)

- = partial factor for steel compressive strength = 1.3 (British Standards Institute, 2002)

- n = reduction factor for timber class 3, submerged in water = 0.8 (British Standards Institute, 2004)

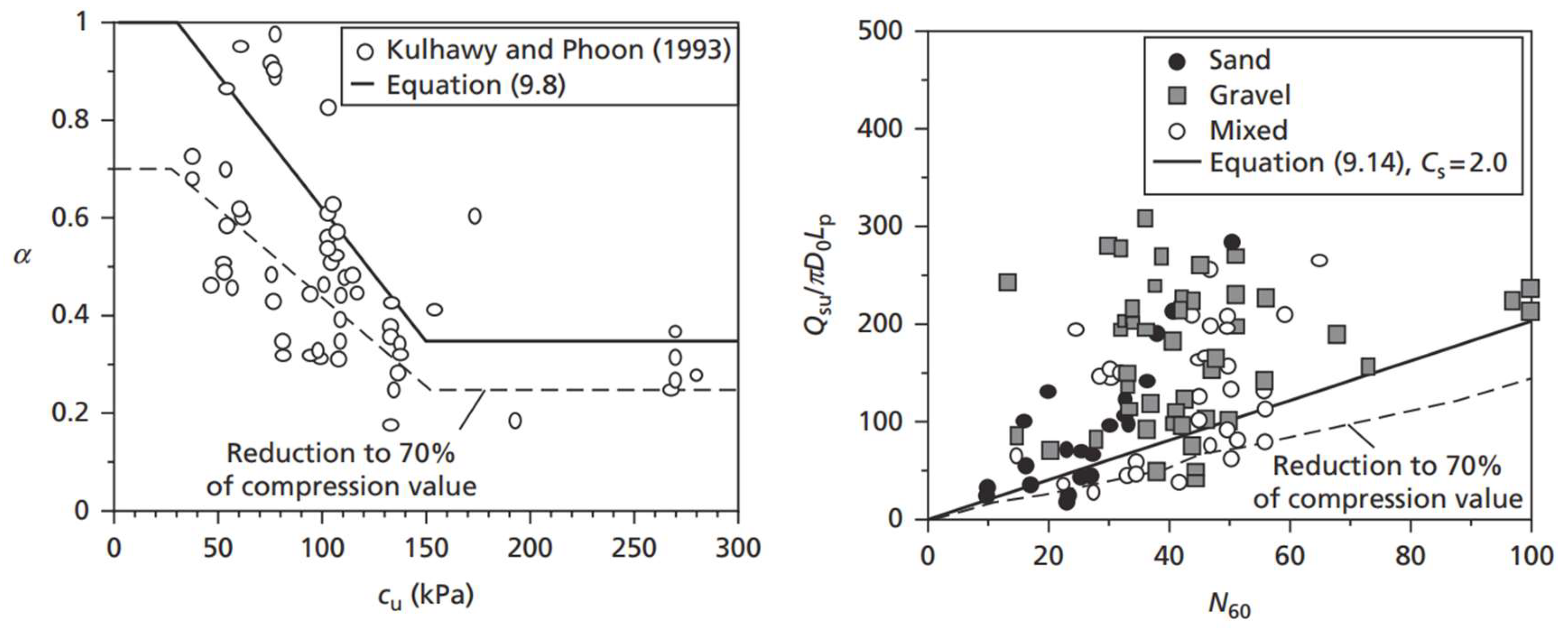

6.2.1.2. Geotechnical Capacity

- -

- , and = pile’s length, diameter and radius.

- -

- , G and E = Poisson’s ratio, shear modulus of elasticity and Young’s modulus of elasticity.

- -

- and = soil effective stress and concrete-soil friction angle.

- -

- = soil-pile friction coefficients.

6.2.1.3. Tested Soil Types

6.2.2. Embodied Carbon Model

6.2.2.1. LCA Approach

- -

- TEC = total embodied carbon (kgCO2e)

- -

- = mass of the construction material (kg)

- -

- = embodied carbon factor for a given material (kgCO2e/kg) as shown in Table 2.

6.2.2.2. Embodied Carbon Factors

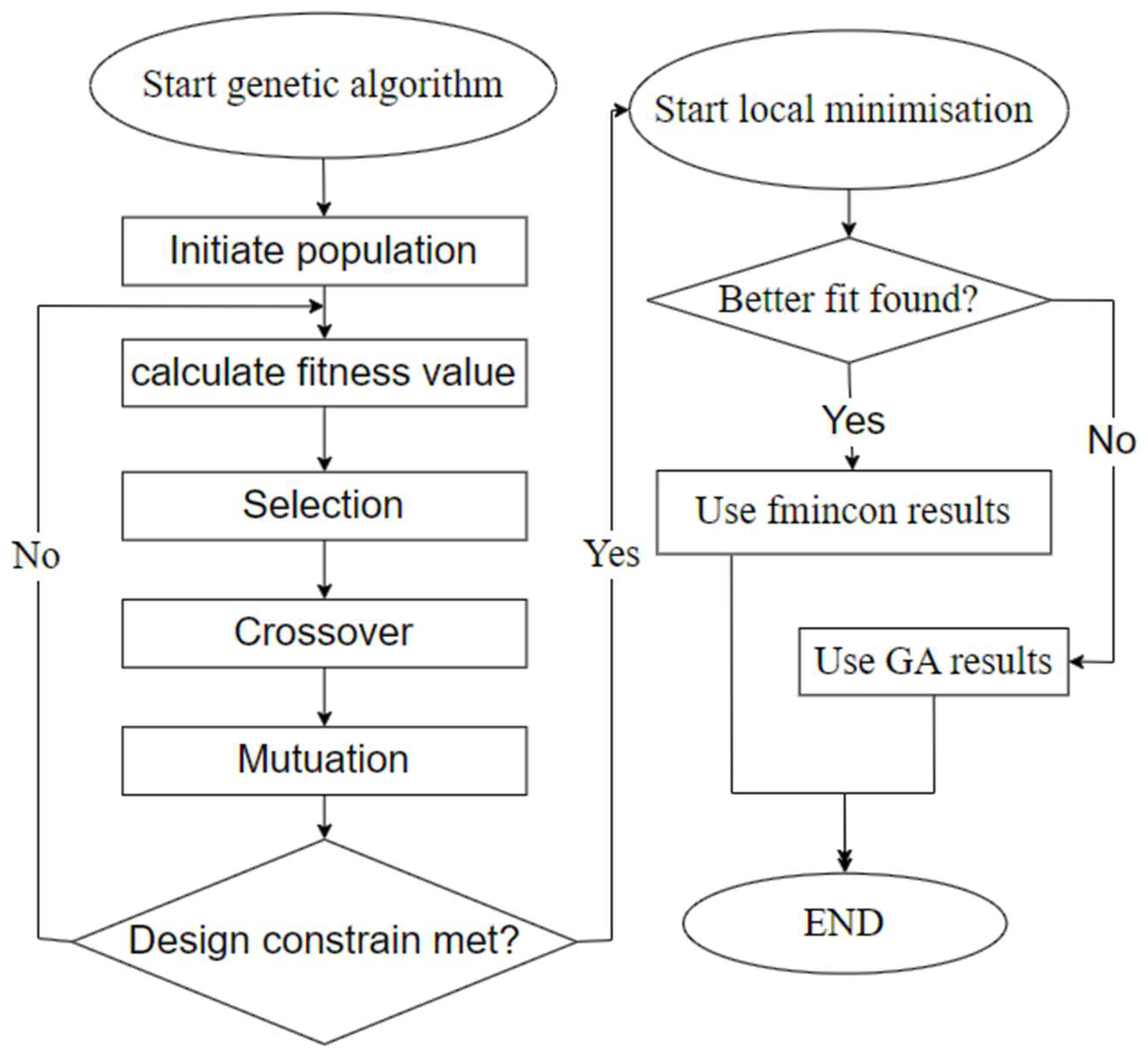

6.2.3.1. Algorithm Definition

6.2.3.2. Section Constraints

6.3. Results and Discussion

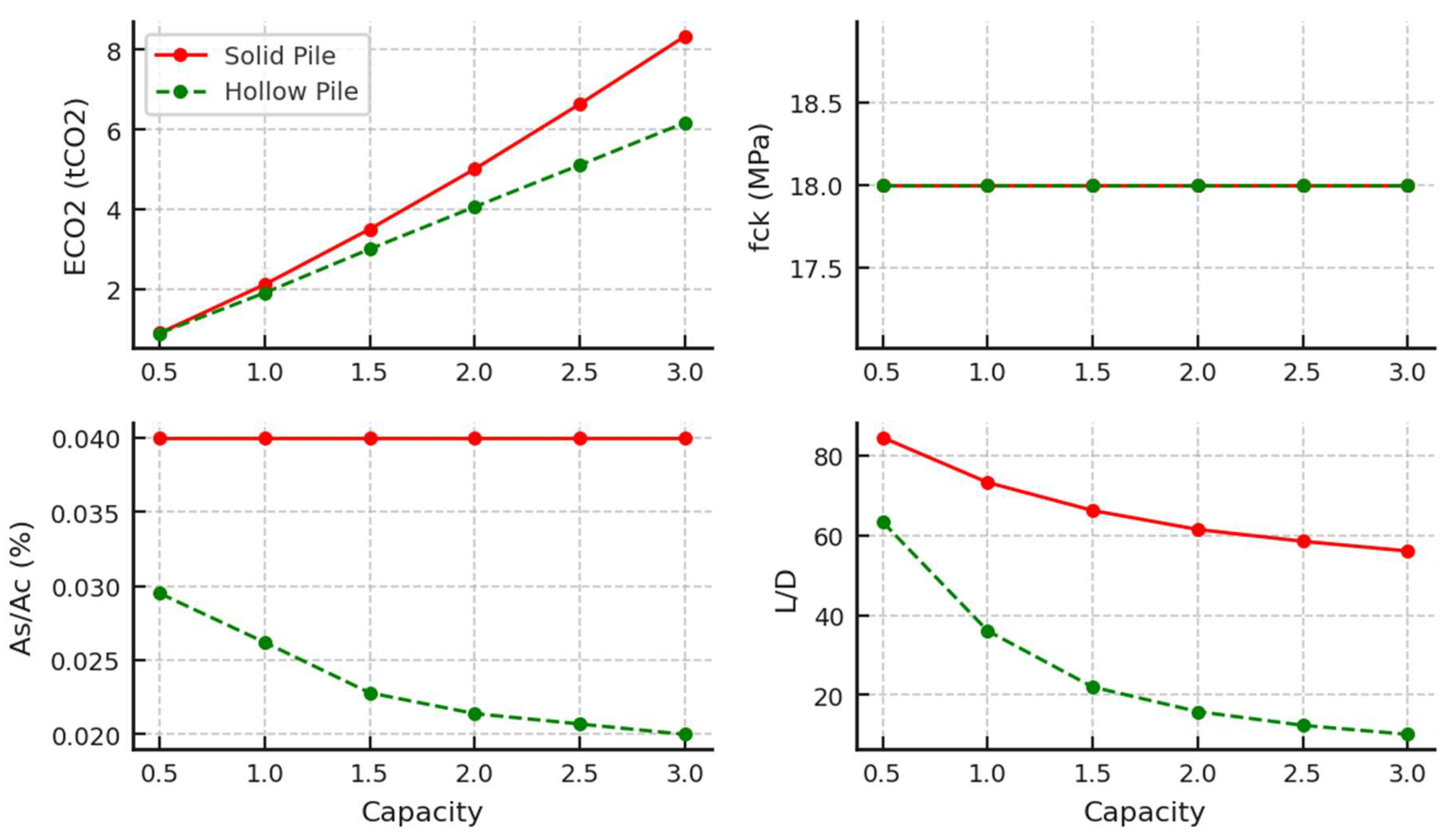

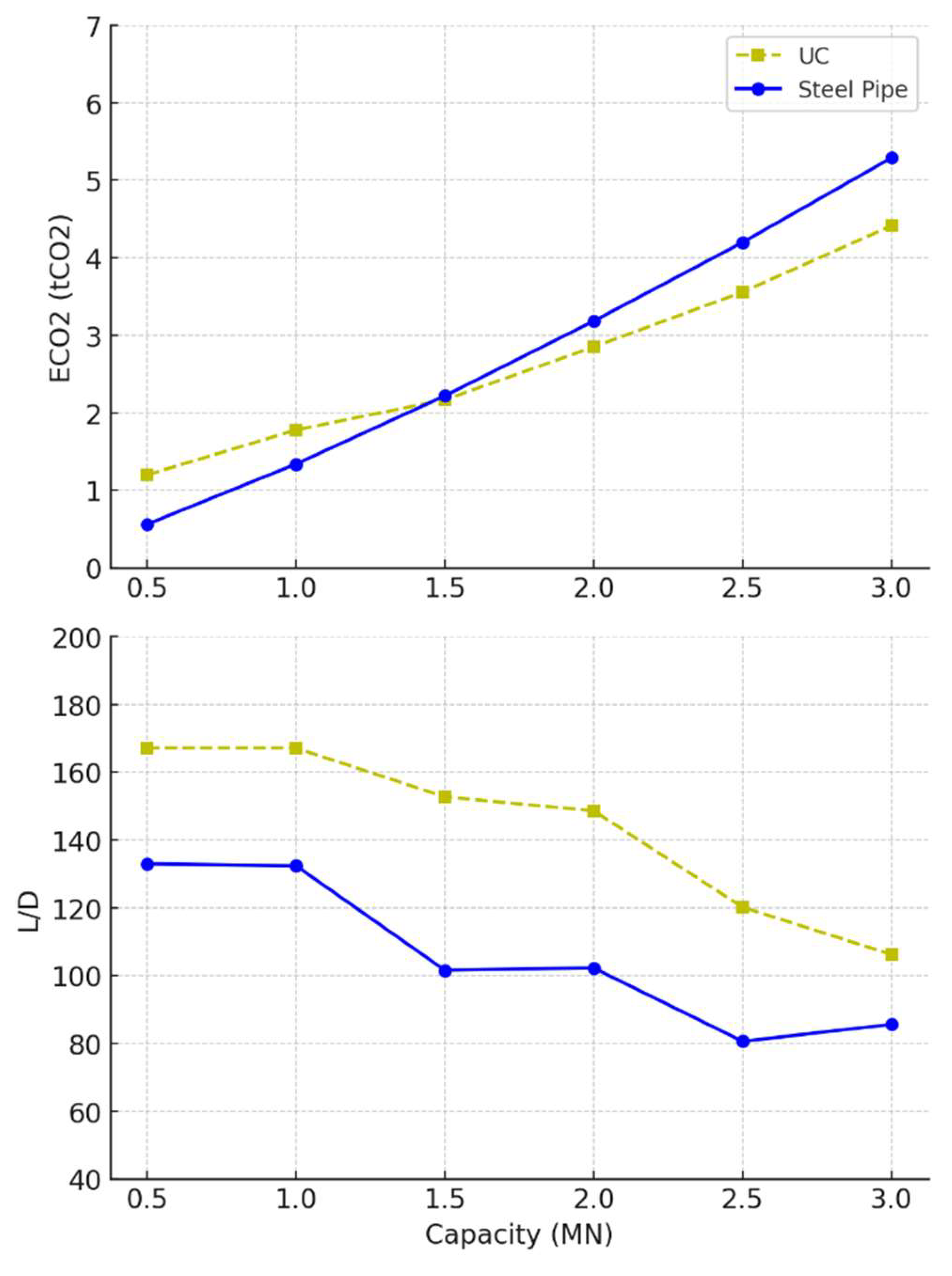

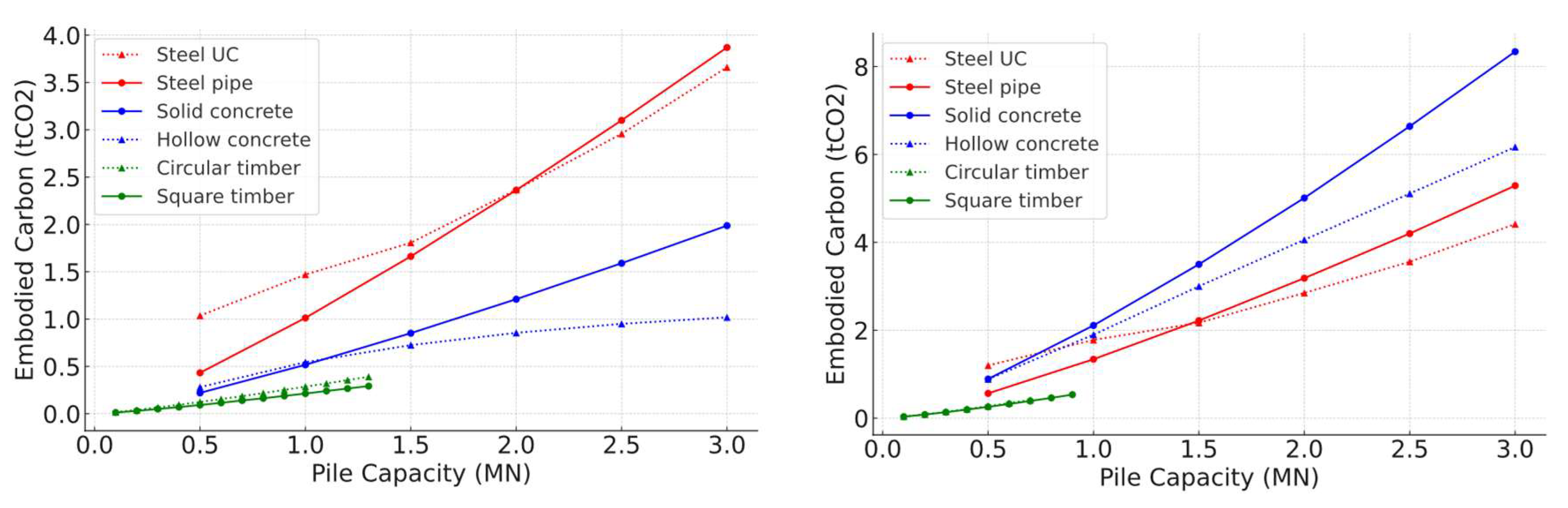

6.3.1. Undrained Clay Soil

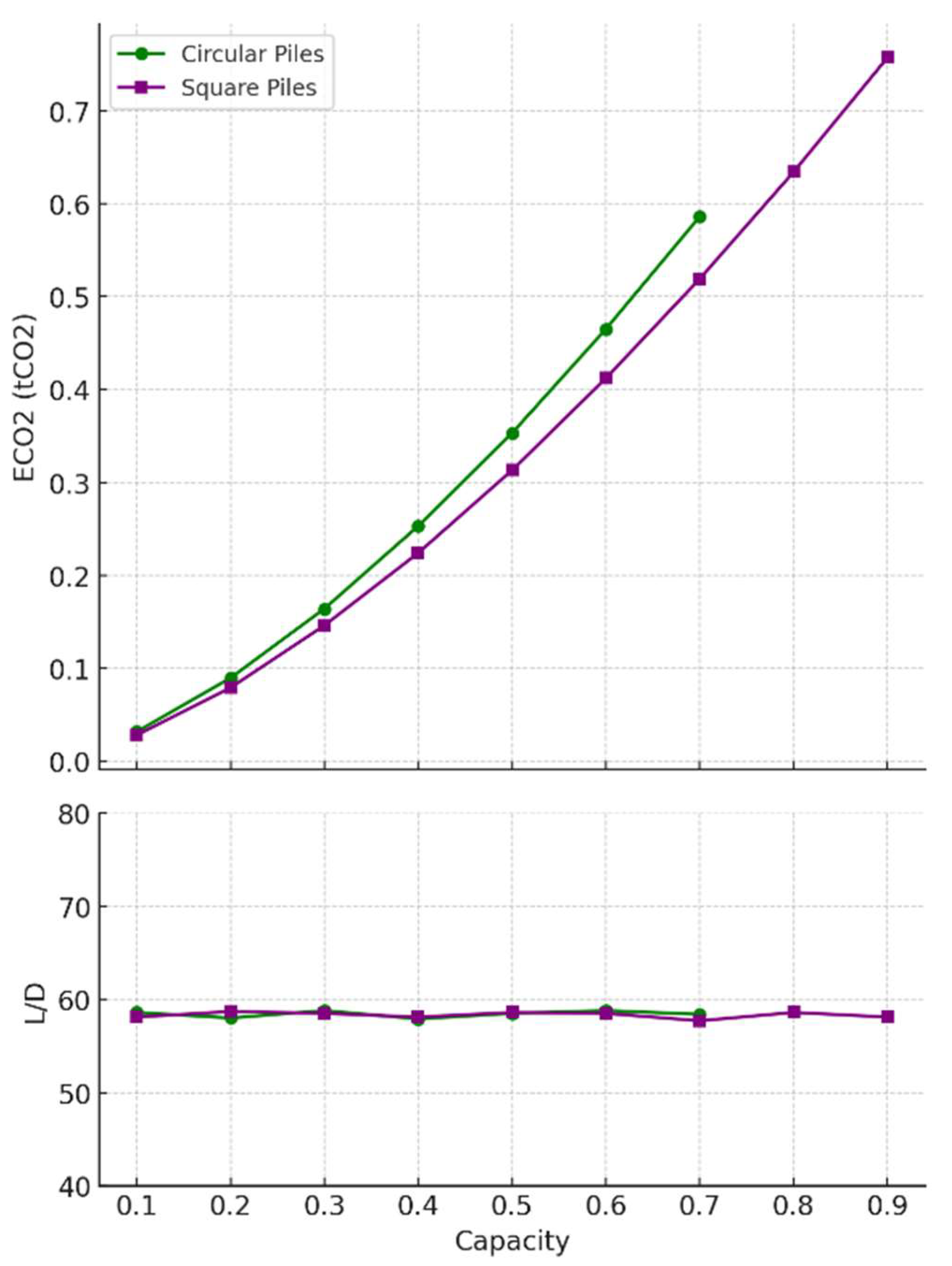

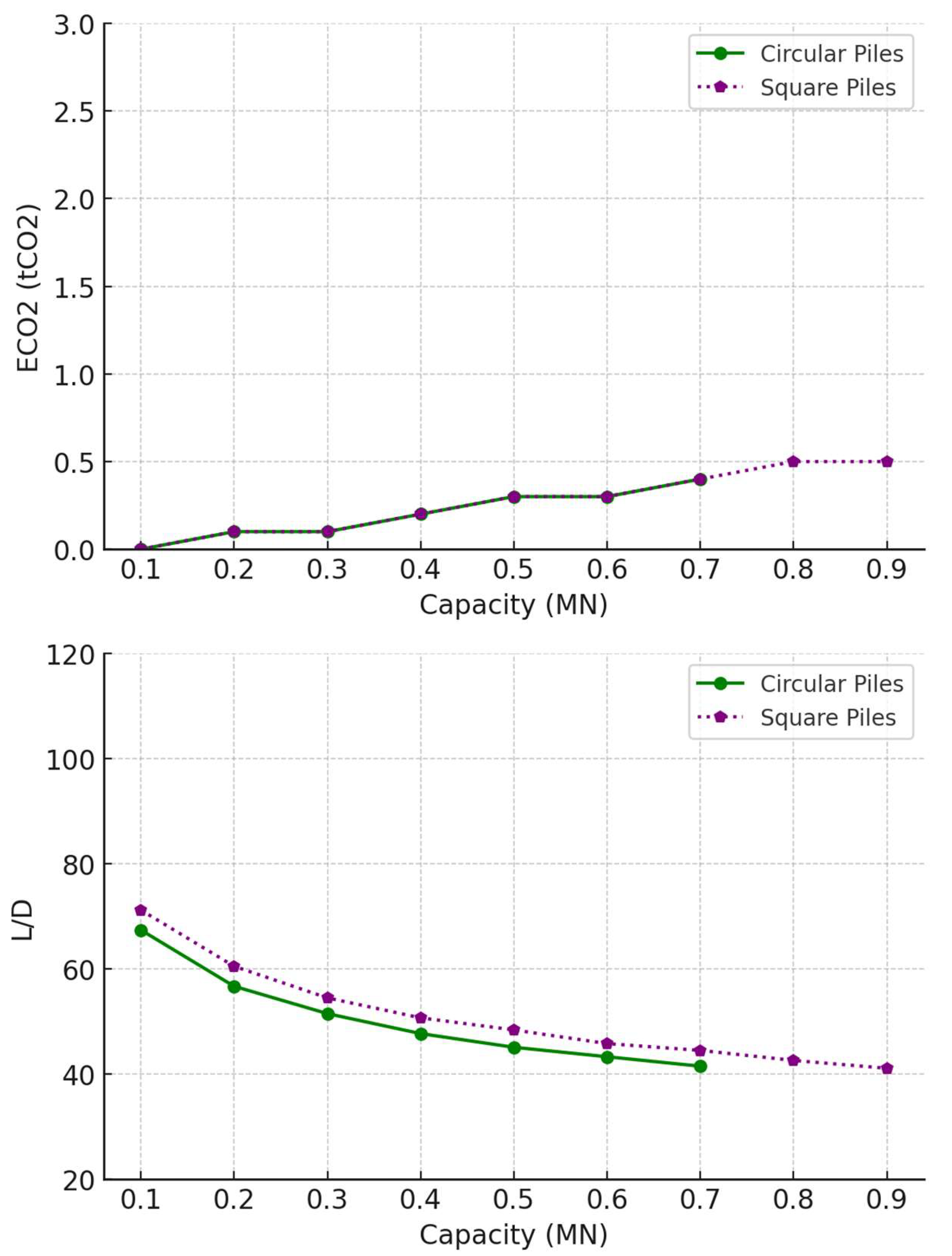

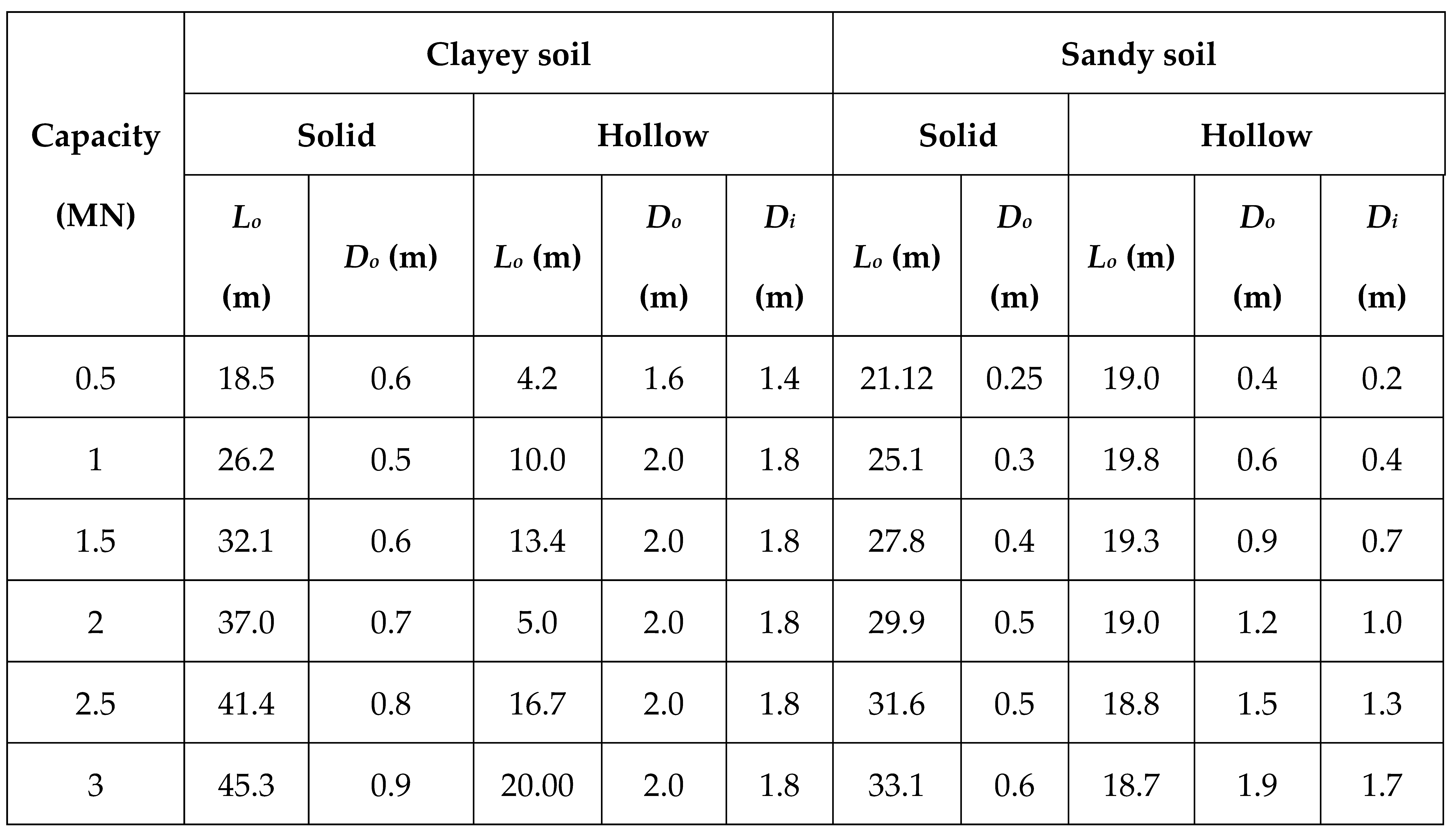

6.3.2. Sand Soil

| Capacity (MN) |

Clayey soil | Sandy soil | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round pile | Square pile | Round pile | Square pile | |||||

| Lo (m)* | Do (m) | Lo (m)* | Do (m) | Lo (m)* | Do (m) | Lo (m)* | Do (m) | |

| 0.1 | 9.8 | 0.17 | 8.7 | 0.15 | 11.6 | 0.17 | 10.7 | 0.15 |

| 0.2 | 13.9 | 0.24 | 12.3 | 0.21 | 13.5 | 0.24 | 12.7 | 0.21 |

| 0.3 | 17.1 | 0.29 | 15.1 | 0.26 | 14.9 | 0.29 | 14.1 | 0.26 |

| 0.4 | 19.7 | 0.34 | 17.4 | 0.30 | 16.1 | 0.34 | 15.1 | 0.30 |

| 0.5 | 22.0 | 0.38 | 19.5 | 0.33 | 17.0 | 0.38 | 16.0 | 0.33 |

| 0.6 | 24.1 | 0.41 | 21.4 | 0.37 | 17.8 | 0.41 | 1.7 | 0.37 |

| 0.7 | 26.0 | 0.45 | 23.1 | 0.40 | 18.9 | 0.45 | 17.4 | 0.39 |

| 0.8 | - | - | 24.7 | 0.42 | - | - | 18.0 | 0.42 |

| 0.9 | - | - | 26.2 | 0.45 | - | - | 18.0 | 0.45 |

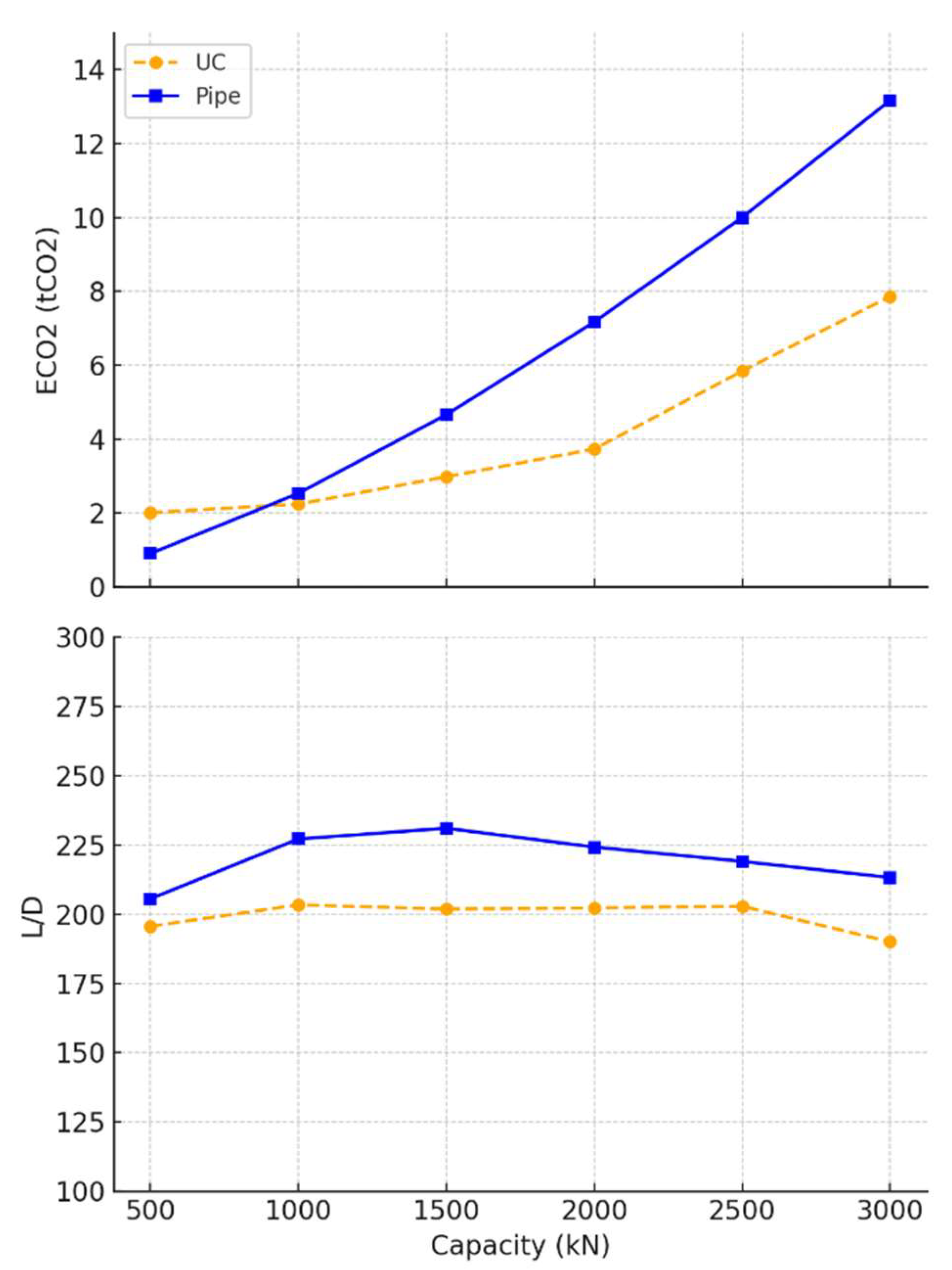

6.3.3. Tension vs Compression Piles

6.3.3.1. Tension vs Compression Piles in Undrained Clay

6.3.3.2. Tension vs Compression Piles in Loose Sand

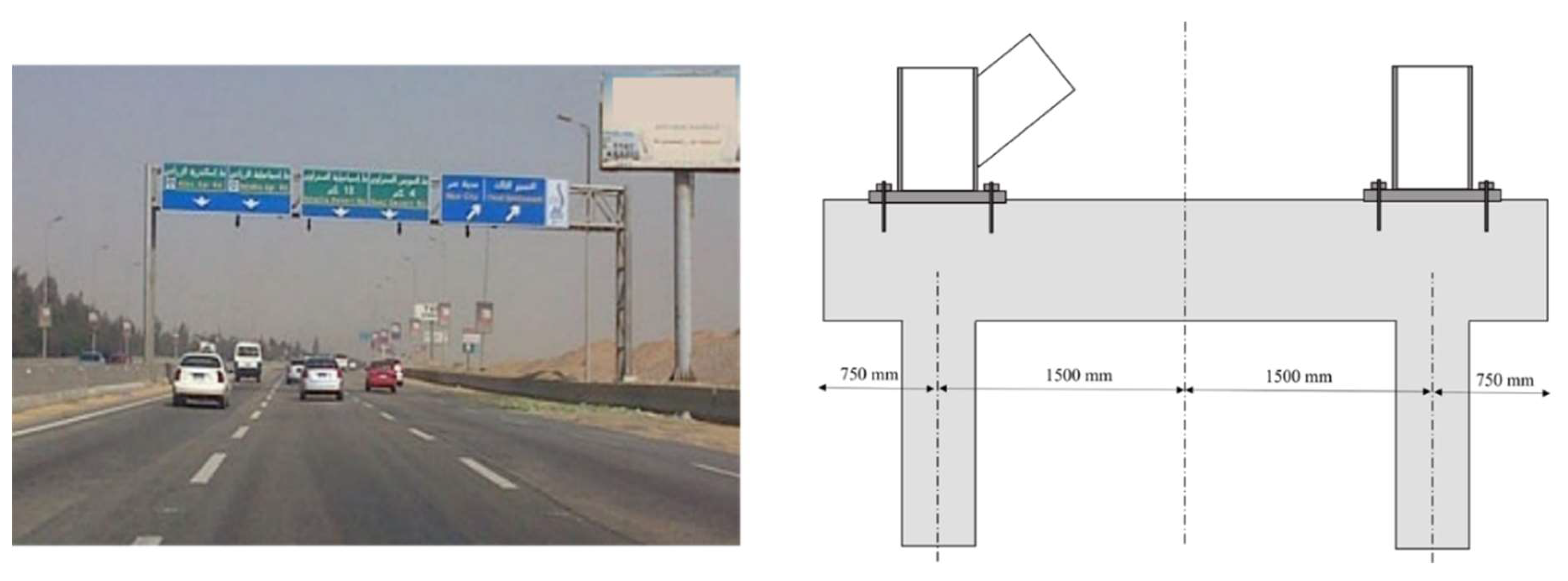

6.4. Case Study

6.4.1. Case Description

6.4.2. Soil Profile and Pile Design

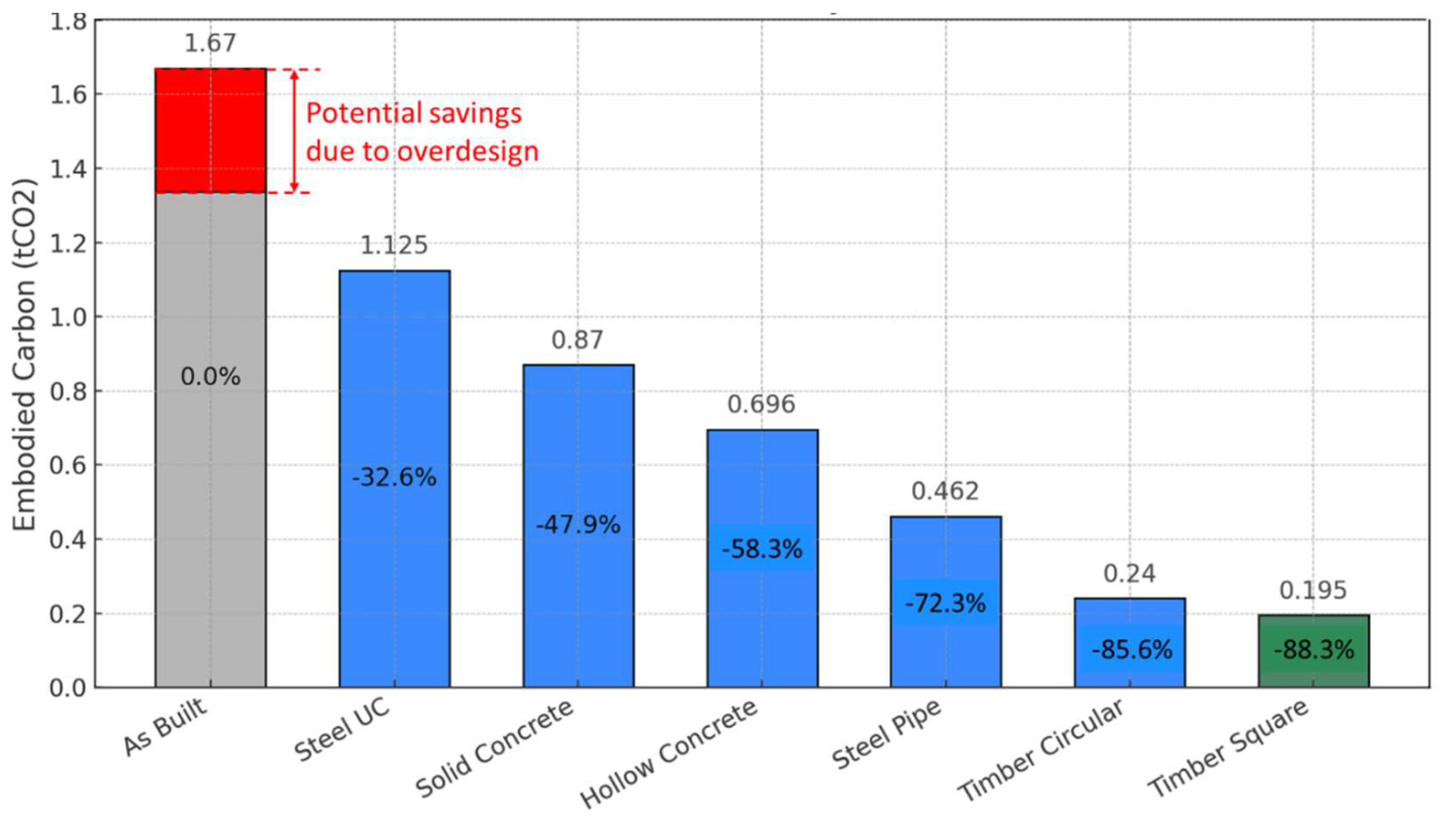

6.4.3. Pile Optimisation Results and Discussion

- Availability of timber piles: timber piles have shown to be the most sustainable option in this study, especially for lower-capacity pile designs. However, it is crucial to recognise that timber sections are not universally accessible across all regions. In countries with limited forest resources, especially those with arid climates, the availability of piling-grade timber can be a significant constraint (Drewniok et al., 2023). Furthermore, timber prices and logistical challenges associated with transportation and procurement may limit the feasibility of widespread adoption, especially in regions where alternative materials, such as concrete or steel, are more readily available and economically viable. Another issue remains the unsuitability of timber sections for soils with changing GWT levels as timber becomes more vulnerable to decomposition and losing strength.

- Industry practices: feedback from contractors revealed that many companies typically adopt off-the-shelf pile designs, with standardised section dimensions and reinforcement specifications. These designs are often conservative to account for the uncertainties associated with varying soil conditions and profiles across different locations. While this approach enhances the robustness of pile designs, it presents a challenge to the adoption of sustainability-focused designs during the early stages of project planning. The industry’s reliance on conservative designs may hinder the transition to more sustainable practices, particularly when optimising for embodied carbon reduction.

- Culture: social factors also play a critical role in the selection of piling solutions. However, social acceptance is difficult to quantify and can vary significantly between regions, clients, and contractors. What is deemed an acceptable or preferable solution in one geographical area or by one contractor may not be viewed similarly elsewhere. This subjectivity adds another layer of complexity when implementing sustainable design options, as local preferences and perceptions can significantly impact decision-making.

- Uncertainties: the embodied carbon of structures varies across different locations due to regional disparities in transportation logistics, material sourcing, and availability. In countries with longer supply chains or limited local resources, higher emissions may result from transporting materials over greater distances, while countries with abundant local materials can reduce embodied carbon significantly.

6.5. Conclusion

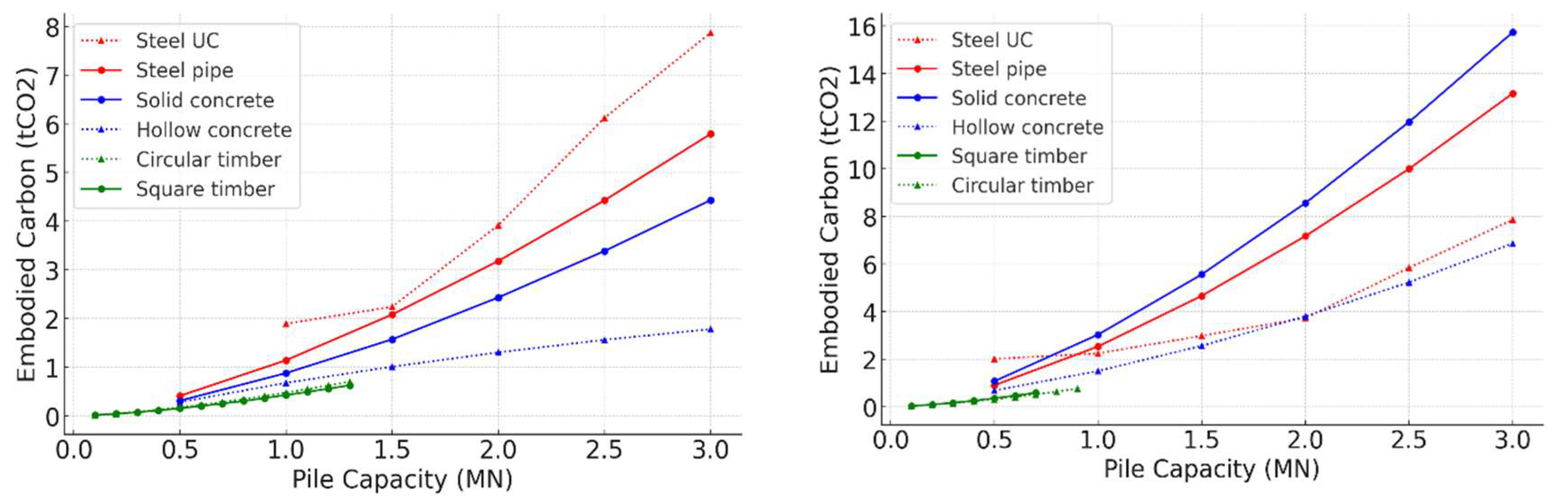

- Tension piles in undrained clay were shown to be more emitting than their alternates in loose sand. This is believed to be due to the nature of sandy soil that exhibits higher surface friction resistance than undrained clay, a main factor that influences the capacity of tension piles.

- For undrained clay, the optimisation results indicate that while timber piles are restricted to lower capacity applications, circular designs exhibit slightly superior environmental performance, though the difference between square and circular sections remains minimal. Hollow concrete piles and UC steel sections demonstrate greater material efficiency and sustainability compared to solid concrete and steel pipe piles, particularly in terms of reducing embodied carbon. The observed efficiency of hollow concrete piles aligns with findings reported in the literature (Lalicata et al., 2022).

- In loose sand, timber piles, though limited to lower capacities, are the most sustainable options for low pile capacities, with minimal differences in embodied carbon and L/D ratios between circular and square designs. Both concrete and steel piles exhibiting more compact, material-efficient designs due to steeper declines in their optimal L/D ratios compared to undrained clay designs. For high pile capacities, UC steel piles outperform other pile types in terms of embodied carbon.

- The optimisation tool was applied to an existing case study for a large cross-road signpost and demonstrated significant potential in reducing the embodied carbon of pile foundations, with timber, steel, and hollow concrete piles offering substantial carbon savings. However, practical challenges such as the limited availability of timber, conservative industry practices, and varying social acceptance across regions must be addressed to facilitate the widespread adoption of these sustainable designs in real-world construction.

- The findings of this study are specific to the selected input soil properties, and variations in soil types may yield different optimal pile designs, as demonstrated in the case study. Nonetheless, the conceptual optimisation technique employed remains applicable across diverse soil conditions, offering flexibility and adaptability for future design scenarios. Designers are therefore encouraged to adapt the proposed optimisation approach to their local contexts and material data rather than directly relying on the specific findings presented in this paper.

Acknowledgement

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector. Nairobi: UNEP; 2022.

- Hong, T.; Ji, C.; Jang, M.; Park, H. Assessment Model for Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions during Building Construction. J. Manag. Eng. 2014, 30, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regona, M.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Hon, C.; Teo, M. Artificial intelligence and sustainable development goals: Systematic literature review of the construction industry. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Brown, N.; De Wolf, C.; Mueller, C. Reducing embodied carbon in structural systems: A review of early-stage design strategies. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauch, H.; Dunant, C.; Hawkins, W.; Serrenho, A.C. What really matters in multi-storey building design? A simultaneous sensitivity study of embodied carbon, construction cost, and operational energy. Appl. Energy 2023, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faddoul, Y.; Sirivivatnanon, V. Sustainable concrete structures by optimising structural and concrete mix design. Aust. J. Struct. Eng. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahab, M.; Ashour, A.; Toropov, V. Cost optimisation of reinforced concrete flat slab buildings. Eng. Struct. 2004, 27, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhang X. Sustainable design of reinforced concrete structural members using embodied carbon emission and cost optimization. Journal of Building Engineering. 2021 Dec 1;44:102940.

- Jayasinghe A, Orr J, Ibell T, Boshoff WP. Minimising embodied carbon in reinforced concrete beams. Engineering Structures. 2021 Sep 1;242:112590.

- Kayabekir, A.E.; Arama, Z.A.; Bekdaş, G.; Nigdeli, S.M.; Geem, Z.W. Eco-Friendly Design of Reinforced Concrete Retaining Walls: Multi-objective Optimization with Harmony Search Applications. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasbaneh AT, Marsono AK. Applying multi-criteria decision-making on alternatives for earth-retaining walls: LCA, LCC, and S-LCA. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 2020 Nov;25:2140-53.

- Abushama, K.; Hawkins, W.; Pelecanos, L.; Ibell, T. Embodied carbon optimisation of concrete pile foundations and comparison of the performance of different pile geometries. Eng. Struct. 2024, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushama, K.; Hawkins, W.; Pelecanos, L.; Ibell, T. Minimising the embodied carbon of reinforced concrete piles using a multi-level modelling tool with a case study. Structures 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushama, K.; Hawkins, W.; Pelecanos, L.; Ibell, T. Optimising the embodied carbon of laterally loaded piles using a genetic algorithm and finite element simulation. Results Eng. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Jia, S. Embodied energy and carbon emissions analysis of geosynthetic reinforced soil structures. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, F.; AliPanahi, P.; Sadeghi, H. A comparative study of environmental and economic assessment of vegetation-based slope stabilization with conventional methods. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teodosio, B.; Wasantha, P.; Yaghoubi, E.; Guerrieri, M.; Fragomeni, S.; van Staden, R. Environmental, economic, and serviceability attributes of residential foundation slabs: A comparison between waffle and stiffened rafts using multi-output deep learning. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandanayake, M.; Zhang, G.; Setunge, S. Environmental emissions at foundation construction stage of buildings – Two case studies. Build. Environ. 2016, 95, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danziger, F.; Danziger, B.; Pacheco, M. The simultaneous use of piles and prestressed anchors in foundation design. Eng. Geol. 2006, 87, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-J.; Gong, X.-N.; Wang, K.-H.; Zhang, R.-H.; Yan, J.-J. Testing and modeling the behavior of pre-bored grouting planted piles under compression and tension. Acta Geotech. 2017, 12, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickin EA, Leung CF. Performance of piles with enlarged bases subject to uplift forces. Canadian Geotechnical Journal. 1990 Oct 1;27(5):546-56.

- Shanker, K.; Basudhar, P.K.; Patra, N.R. Uplift capacity of single piles: predictions and performance. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2006, 25, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsoy, S.; Duncan, J.M.; Barker, R.M. Performance of Piles Supporting Integral Bridges. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2002, 1808, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, H. On the pile tension capacity of scoured tripod foundation supporting offshore wind turbines. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G. Experimental investigations and analysis on different pile load testing procedures. Acta Geotech. 2012, 8, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Pile reinforcement mechanism of soil slopes. Acta Geotech. 2017, 12, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger RW, Kutter BL, Brandenberg SJ, Singh P, Chang D. Pile foundations in liquefied and laterally spreading ground during earthquakes: centrifuge experiments & analyses. Davis: University of California, Center for Geotechnical Modeling; 2003 Sep.

- Rainer J. Accuracy of pile capacity assessment on the basis of piling reports. E3S Web of Conferences. 2019;97:04029.

- Lacasse S, Nadim F, Langford T, Knudsen S, Yetginer GL, Guttormsen TR, Eide A. Model uncertainty in axial pile capacity design methods. In: Offshore Technology Conference; 2013 May 6; Houston, USA. OTC-24066.

- Bueno Aguado M, Escolano Sánchez F, Sanz Pérez E. Model uncertainty for settlement prediction on axially loaded piles in hydraulic fill built in marine environment. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2021 Jan 8;9(1):63.

- Levacher DR, Sieffert JG. Tests on model tension piles. J. Geotech. Engineering. 1984; 110, 1735–1748.

- Alawneh, A. Tension Piles in Sand: A Method Including Degradation of Shaft Friction During Pile Driving. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 1999, 1663, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeres-Ferradosa, T.; Chambel, J.; Taveira-Pinto, F.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Taveira-Pinto, F.V.C.; Giannini, G.; Haerens, P. Scour Protections for Offshore Foundations of Marine Energy Harvesting Technologies: A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikbarieh, A.; Izadifar, M.; Abu-Farsakh, M.Y.; Voyiadjis, G.Z. A parametric study of embankment supported by geosynthetic reinforced load transfer platform and timber piles tip on sand. Transp. Geotech. 2022, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawabdeh, A.M.A.; Vinod, J.S.; Liu, M.D.; McCarthy, T.J.; Redwood, S. Large-Scale Laboratory Testing of Helical Piles: Effect of the Shape. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2023, 42, 1675–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bushama K, Ibell T, Pelecanos L, Hawkins W. Concrete piles with lowest carbon emissions and optimised environmental impact. In: XVIII European Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering; 2024 Aug 26-30; United Kingdom. [CrossRef]

- British Standards Institution. Eurocode 2: design of concrete structures: British standard. London: BSi; 2008.

- British Standards Institution. Eurocode 3—Design of steel structures. BS EN 1993-1-1:2005.

- British Standards Institution. Eurocode 5. Design of timber structures: Part 1-1. General rules and rules for buildings. London: British Standards Institution.

- British Standards Institution. Eurocode 1: Actions on structures—Part 1: General actions. BS EN 1991-1-1:2002. London: British Standards Institution; 2002.

- Alawneh AS, Husein Malkawi AI, Al-Deeky H. Tension tests on smooth and rough model piles in dry sand. Canadian Geotechnical Journal. 1999;36(4):746-Here is the continuation and completion of your Vancouver-style reference list:.

- Alawneh AS, Husein Malkawi AI, Al-Deeky H. Tension tests on smooth and rough model piles in dry sand. Canadian Geotechnical Journal. 1999;36(4):746-53.

- Lehane BM, Jardine RJ, Bond AJ, Frank R. Mechanisms of shaft friction in sand from instrumented pile tests. Journal of Geotechnical Engineering. 1993 Jan;119(1):19-35.

- De Nicola A, Randolph MF. Tensile and compressive shaft capacity of piles in sand. Journal of Geotechnical Engineering. 1993 Dec;119(12):1952-73.

- Kulhawy FH, Phoon KK. Drilled shaft side resistance in clay soil to rock. In: Design and Performance of Deep Foundations: Piles and Piers in Soil and Soft Rock; 1993 Oct 24; ASCE. p. 172-83.

- Phoon KK, Kulhawy FH. Characterization of geotechnical variability. Canadian Geotechnical Journal. 1999;36(4):612-24.

- Knappett J, Craig RF. Craig’s Soil Mechanics. Florida: CRC Press LLC; 2012.

- Athena Sustainable Materials Institute. Athena Impact Estimator for Buildings [software]. Version 5.4. Ottawa: Athena Sustainable Materials Institute; 2020.

- Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS). Whole Life Carbon Assessment for the Built Environment. London: RICS; 2017.

- Gibbons OP, Orr JJ, Archer-Jones C, Arnold W, Green D. How to Calculate Embodied Carbon. London: Institution of Structural Engineers (ISTRUCTE); 2022.

- British Standards Institution (BSI). BS EN 15978:2011 - Sustainability of Construction Works. Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings. London: BSI; 2011.

- Hammond G, Jones C. Inventory of Carbon & Energy: ICE. Bath, UK: Sustainable Energy Research Team, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bath; 2008.

- Miles, J. Genetic algorithms for design. In: Advances of Soft Computing in Engineering. Vienna: Springer Vienna; 2010. p. 1-56.

- Kanyilmaz, A.; Tichell, P.R.N.; Loiacono, D. A genetic algorithm tool for conceptual structural design with cost and embodied carbon optimization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.-W.; Liu, L.; Burns, S.A. Using Genetic Algorithms to Solve Construction Time-Cost Trade-Off Problems. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 1997, 11, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidy, A.; Rady, M.; Mashhour, I.M.; Mahfouz, S.Y. Structural Design Optimization of Flat Slab Hospital Buildings Using Genetic Algorithms. Buildings 2022, 12, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang JH, Lyu YD, Chung MC. Optimizing pile group design using a real genetic approach. In: Proceedings of the International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference; 2011 Jun 19-24; Maui, Hawaii. ISOPE; 2011. p. 491-9.

- Kim, G.-H.; Yoon, J.-E.; An, S.-H.; Cho, H.-H.; Kang, K.-I. Neural network model incorporating a genetic algorithm in estimating construction costs. Build. Environ. 2004, 39, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.M.; Zhang, L.M.; Ng, J.T. Optimization of Pile Groups Using Hybrid Genetic Algorithms. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2009, 135, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viguier, J.; Bourreau, D.; Bocquet, J.-F.; Pot, G.; Bléron, L.; Lanvin, J.-D. Modelling mechanical properties of spruce and Douglas fir timber by means of X-ray and grain angle measurements for strength grading purpose. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2017, 75, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel Construction Institute, Tata Steel. Steel Building Design: Design Data in Accordance with Eurocodes and the UK National Annexes. Ascot: Steel Construction Institute; 2013.

- Leefers LA, Vasievich JM. Timber resources and factors affecting timber availability and sustainability for Kinross, Michigan. Kinross project. 2010 Dec;2.

- Orr, J.; Drewniok, M.P.; Walker, I.; Ibell, T.; Copping, A.; Emmitt, S. Minimising energy in construction: Practitioners’ views on material efficiency. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalicata LM, Stallebrass SE, McNamara A. An experimental study into the ultimate capacity of an ‘impression’pile in clay. Géotechnique. 2023 May;73(5):455-66.

- Abushama K, Hawkins W, Pelecanos L, Ibell T. Optimizing the embodied carbon of concrete, timber, and steel piles with a case study. The 1st International Conference on Net-Zero Built Environment: Innovations in Materials, Structures, and Management Practices. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering. 1st ed. Cham: Springer; 2025. [CrossRef]

| Soil type | Property | Symbol | Value (unit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Undrained clay | Unit weight | 18 (kN/m3) | |

| Undrained shear strength | cu | 80 + 1.5z* (kPa) | |

| Poisson’s ratio | v | 0.2 | |

| Shear modulus | G | 5000 + 500z* (kPa) | |

| Dry loose sand | Unit weight | 15 (kN/m3) | |

| Angle of internal friction | φ′ | 32o | |

| Pile-soil interface angle | δ′ | 24o | |

| *Depth from the top. | |||

|

| Material | A1-A3 (kgCO2e/kg) |

A4 (kgCO2e/kg) |

A5 (kgCO2e/kg) |

Assumptions |

| In-situ cast concrete | 0.082 + 0.002 fck | 0.005** | 0.053 | Linear regression of the ICE inventory (Abushama et al., 2023b) |

| Reinforcement steel bars | 1.99 | 0.032* | 0.053 | Worldwide steel of low recycled content |

| Construction steel | 1.55 | 0.032* | 0.01 | Worldwide open steel sections |

| Timber | 0.263 | 0.032* | 0.01 | Studwork, softwood |

| * Material considered nationally manufactured with a road travel distance of 300 km. ** Material considered locally manufactured with a road travel distance of 50 km (Gibbons et al., 2022) | ||||

|

| (MN) | Clayey soil | Sandy soil | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pipe section | UC section | Pipe section | UC section | |||||||

| Lo (m) | Do (m) | to (mm) | Lo (m) | section | Lo (m) | Do (m) | to (mm) | Lo (m) | section | |

| 0.5 | 39.8 | 0.19 | 4.0 | 30.2 | 152x152x37 | 25 | 0.19 | 4.0 | 21.8 | 152x152x23 |

| 1 | 50.3 | 0.22 | 5.0 | 32.0 | 152x152x51 | 29.7 | 0.22 | 5.0 | 25.4 | 152x152x23 |

| 1.5 | 68.9 | 0.32 | 6.0 | 41.0 | 203x203x46 | 32.9 | 0.32 | 6.0 | 31.0 | 203x203x46 |

| 2 | 79.6 | 0.36 | 8.0 | 41.3 | 203x203x52 | 36.4 | 0.36 | 8.0 | 31.7 | 203x203x100 |

| 2.5 | 89.0 | 0.41 | 8.0 | 51.6 | 254x254x73 | 37.4 | 0.46 | 8.0 | 31.9 | 257x254x167 |

| 3 | 97.4 | 0.46 | 8.0 | 58.0 | 305x305x79 | 39.1 | 0.46 | 10 | 32.7 | 305x305x18 |

| Soil parameter [symbol] (unit) | Layer 1 - Sand | Layer 2 - Silty clay |

| Layer depth [z] (m) | [0-25] | [25-42] |

| Unit Weight [γ] (kN/m3) | 19 | 20 |

| Young’s modulus [E] (MPa) | [25-50] | [25-30] |

| Effective cohesion [c] (kPa) | 0 | [20-30] |

| Effective friction angle [φ] (Degrees) | [32-36] | 20 |

| Pile type | Design | Embodied carbon |

| As-built design |

L = 18 m D = 0.5 m fck = 25 MPa As/Ac = 1.5% |

Reference value |

| Solid concrete |

L = 20m D = 0.25 m fck = 25 MPa As/Ac = 4% |

-47.9% |

| Hollow concrete |

L = 17m Do = 0.3 m, Di = 0.1 fck = 25 MPa As/Ac = 2.4% |

-58.3% |

| Steel pipe |

L = 23.62 D = 0.2 m t = 3 mm |

-72.3% |

| Steel UC |

L = 16 m Section = 203x203x46 |

-32.6% |

| Circular timber |

L = 16.5 D = 0.35 C24 |

-85.6% |

| Square timber |

L = 15.5 D = 0.3 C24 |

-88.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).