1. Introduction

In contemporary usage, the term "stress" extends far beyond its linguistic origins, encompassing diverse contexts such as physics, biology, physiology, psychology, materials science, engineering, sociology, and other fields. In biology and medicine, stress typically refers to physiological or psychological responses to challenging stimuli. In physics and engineering, stress denotes the internal forces per unit area within a material that arise in response to external loads or deformations. In sociology and economics, stress captures societal pressures and financial strains that affect communities and individuals.

The term’s adaptability underscores its interdisciplinary importance, but its broad use across fields has led to conceptual divergence. However, the widespread use of the same term across different fields has led to a divergence in its meaning, often resulting in confusion and misunderstandings—especially in interdisciplinary communication, which is essential for integrating knowledge. This challenge is particularly evident in the life sciences, where the development and expansion of stress-related studies highlight the need for greater conceptual clarity and consistency.

Hans Selye, regarded as the father of stress research, introduced the term "stress" [

1] to explain the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) in human physiology in the context of disease [

2]. Since its inception, the concept of stress has been widely applied across various medical science disciplines, including cell biology [

3], physiology [

4], endocrinology [

5], neurology [

6], and psychology [

7,

8]. Selye defined stress as "

a nonspecific response of the body to a demand" [

9], and proposed that all mammals undergo a predictable sequence of reactions to stress: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion [

10]. However, Selye initially presumed that stress responses require a nervous system, excluding non-animals (e.g. plants and microorganisms) from his framework. This assumption led to the independent evolution of stress concepts in medical, plant, and microbial sciences.

Recent advances in molecular biology and biochemistry have challenged this view, revealing that stress responses are not exclusive to organisms with nervous systems. In plants, microbes, and even single celled microorganisms, stress responses involve dynamic biochemical processes, particularly those mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and reactive sulfur species (RSS) [

11]. The discovery of these reactive molecules has redefined oxidative stress [

12] as a critical concept of cellular adaptation, extending beyond mere damage to include essential regulatory functions in signaling pathways [

13].

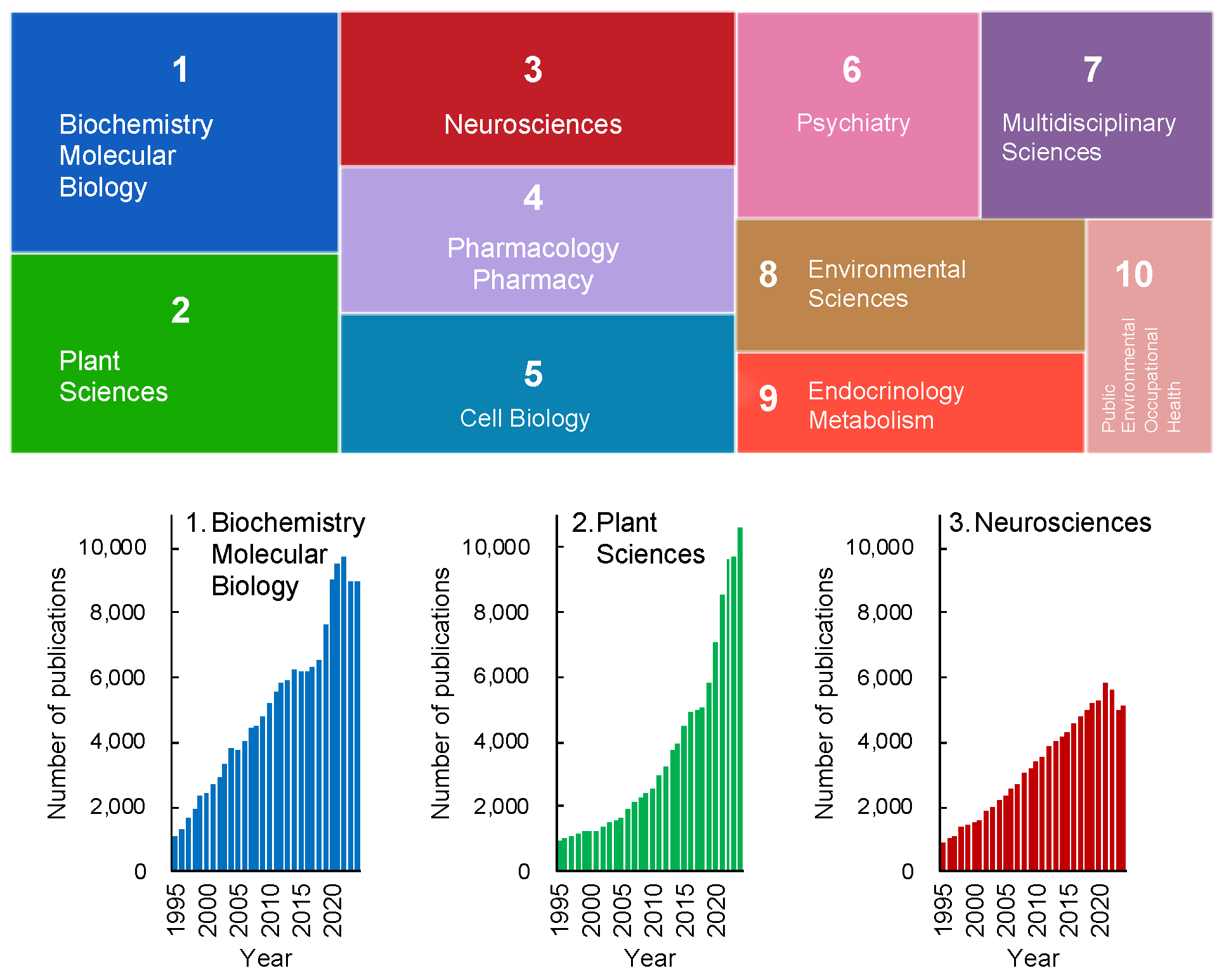

Figure 1 depicts the research trends in stress studies, excluding physics, engineering, and other fields irrelevant to life sciences, over the past 30 years. The analysis was conducted using the Web of Science database and is based on the number of publications. Articles addressing "stress" span a wide range of disciplines, even within the life sciences alone (

Figure 1). Among these fields, biochemistry and molecular biology, plant sciences, and neurosciences are the top three categories in the Web of Science database.

Notably, there has been a recent exponential increase in publications related to plant sciences, indicating that plant stress research is emerging as a significant trend in contemporary science (

Figure 1, lower panel). This growth is particularly striking given that Hans Selye, who introduced the concept of stress, initially excluded plants from his initial framework. Nevertheless, it is now evident that plant sciences have become a key focus in the study of stress.

It is evident that Selye’s concept of stress has undergone significant evolution, incorporating new findings and adapting much like living organisms. This evolution has led to its diversification and the development of varied definitions across academic disciplines. Since Selye’s initial introduction, numerous refinements have been made to the discussions surrounding the concept and definition of stress. Consequently, the definitions of "stress" and "stress response" have diverged across research fields. As of 2020, more than 200 hypotheses or models addressing "stress" have been published across various disciplines [

14].

Selye’s stress theory was originally developed within the context of medical science and mammalian physiology, with a primary focus on hormonal responses [

10]. Therefore, adapting this concept to non-mammals, plants, and microorganisms necessitates further modifications and updates.

By reviewing the key cornerstones and the many twists and turns in the history of stress biology and medicine, we identify two critical keywords for discussion in this review: "nonspecific response" and "balance and imbalance." The concept of a "nonspecific response" to any kind of stimulus lies at the core of Selye’s stress theory. However, to date, there is no generalized framework that fully updates his concept. The fundamental questions remain unresolved:

- (1)

What molecular mechanisms enable a nonspecific response to diverse stressors?

- (2)

How can the same stressor lead to two opposing outcomes—stress adaptation or stress-induced damage?

To achieve a holistic understanding of stress responses, here we propose that the multi-sensitivity of ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs)—including N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) in animals, glutamate receptor-like channels (GLRs) in plants, and the transient receptor potential (TRP) channel superfamily, which is conserved across biological kingdoms—may represent a minimal molecular framework underlying Selye’s GAS.

Beyond its physiological significance, stress embodies a fundamental principle of balance—a concept deeply embedded in Eastern philosophies, such as Yin-Yang in Traditional Chinese Medicine and Mitsudomoe in Japanese culture. These philosophical frameworks emphasize the coexistence of opposing forces, reflecting the dual role of stress in both adaptation (eustress) and dysfunction (distress).

To advance a comprehensive understanding of stress biology and medicine, we discuss that Selye’s GAS concept aligns with traditional Eastern philosophies culturally inherited in China, India, Korea, and Japan, offering valuable insights that may guide future research directions.

2. Stress and Strain in Physics and Engineering: A Foundational Perspective

Before delving into Selye’s concept of stress and the General Adaptation Syndrome, it is valuable to consider how the term "stress" is used in physics and engineering. The principles of stress and strain, which describe how materials respond to external forces, provide a useful analogy for understanding biological stress responses.

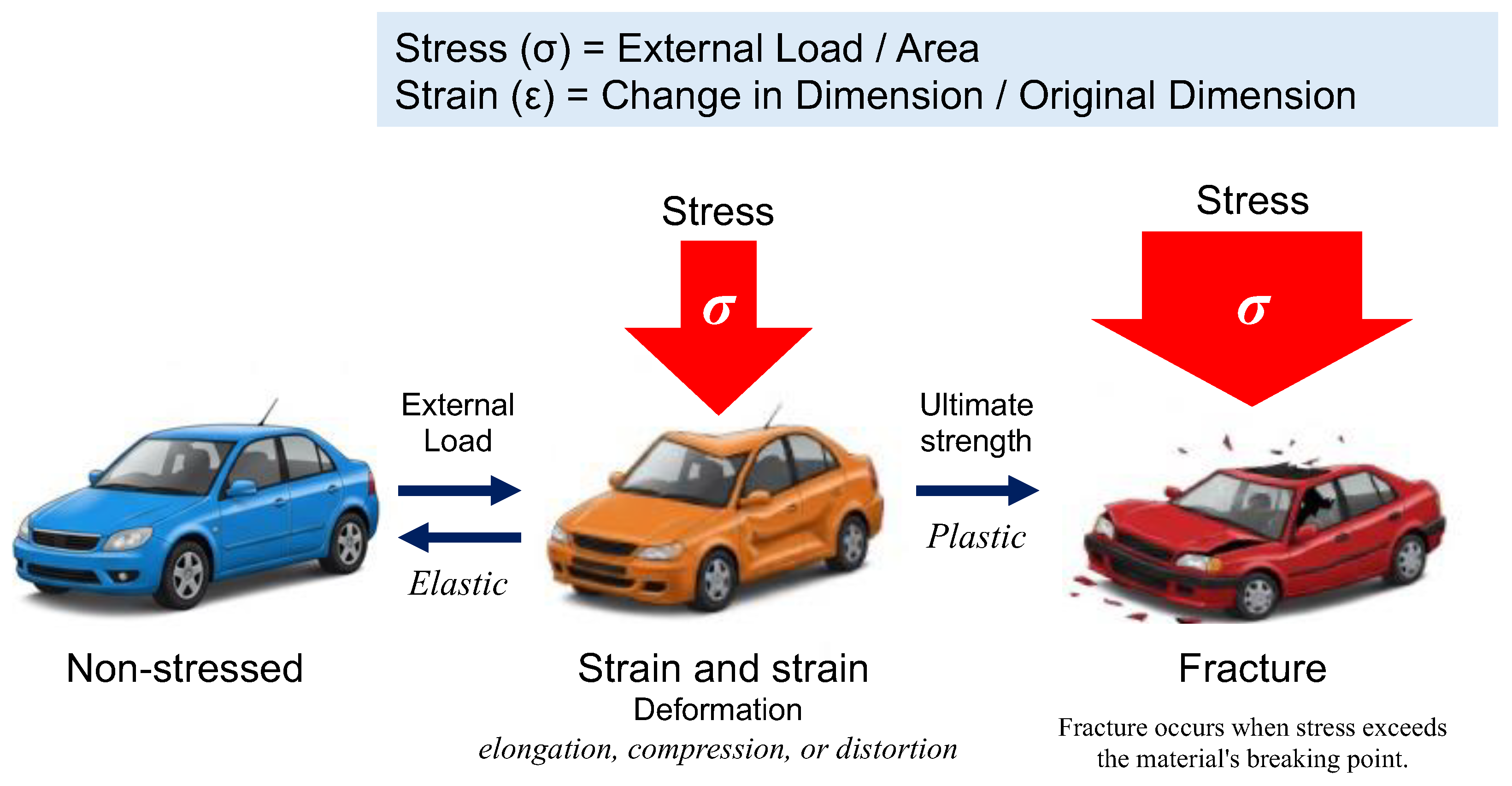

In physics and engineering, stress (σ) is defined as the internal force per unit area within a material subjected to an external load, whereas strain (ε) represents the relative deformation of the material in response to stress (

Figure 2). This relationship is commonly depicted using a stress-strain curve, illustrating key phases of material behavior, including elastic deformation, plastic deformation, and eventual failure.

This fundamental concept—in which external forces induce measurable changes in a system—has expanded beyond its origins in physics to inform our understanding of cellular and physiological adaptations. Recent advances in biomaterials and tissue engineering have revealed remarkable parallels between engineered materials and biological systems, particularly regarding their capacity to sense, respond, and adapt to environmental pressures. These discoveries have deepened our understanding of cellular mechanotransduction [

15,

16] and tissue remodeling processes [

17], significantly contributing to advancements in regenerative medicine and bioengineering applications [

18].

Although stress-strain relationships in physics offer useful analogies, biological stress includes biochemical, molecular, and systemic adaptations that extend beyond mechanical deformation. Nevertheless, the stress-strain framework remains a valuable model for exploring biological materials, including plant structures such as wood [

19], providing essential insights into the mechanical properties of living organisms.

Figure 2.

The fundamental relationship between stress and strain, first formalized through Hooke’s Law in 1660, remains a cornerstone of materials science and engineering. When materials are subjected to external forces, their deformation behavior provides critical insights into mechanical properties and structural integrity. Stress (σ) is defined as the force applied per unit area (σ = Load / Area), while strain (ε) represents the relative deformation, expressed as the ratio of the change in dimension to the original dimension (ϵ = Change in Dimension / Original Dimension). These fundamental parameters form the basis of the stress-strain curve, which characterizes a material’s mechanical response. If a material returns to its original shape upon removal of stress, the deformation is classified as elastic. In contrast, irreversible deformation or fracture indicates plastic behavior.

Figure 2.

The fundamental relationship between stress and strain, first formalized through Hooke’s Law in 1660, remains a cornerstone of materials science and engineering. When materials are subjected to external forces, their deformation behavior provides critical insights into mechanical properties and structural integrity. Stress (σ) is defined as the force applied per unit area (σ = Load / Area), while strain (ε) represents the relative deformation, expressed as the ratio of the change in dimension to the original dimension (ϵ = Change in Dimension / Original Dimension). These fundamental parameters form the basis of the stress-strain curve, which characterizes a material’s mechanical response. If a material returns to its original shape upon removal of stress, the deformation is classified as elastic. In contrast, irreversible deformation or fracture indicates plastic behavior.

3. Cannon’s Homeostasis: Introducing the Principle of Balance to Life Sciences

This review synthesizes a conceptual framework built upon two foundational concepts: Hans Selye’s notion of stress and Walter Bradford Cannon’s principle of homeostasis. Walter Bradford Cannon (1871–1945), a distinguished physiologist, is renowned for his groundbreaking contributions to understanding the autonomic nervous system and for establishing the principle of homeostasis [

20,

21]. His research demonstrated that organisms maintain internal stability through complex regulatory networks, emphasizing a holistic rather than a reductionist approach. Cannon also introduced the term "

fight or flight response," describing the physiological changes that prepare organisms to confront or escape perceived threats [

22].

In his seminal work

The Wisdom of the Body (1932) [

23], Cannon coined the term "homeostasis" to describe the coordinated physiological processes that sustain steady states within organisms, distinct from equilibrium in the physical sense. This concept built upon Claude Bernard’s earlier notion of the "

milieu intérieur" (internal environment) [

21].

Through extensive experimental research conducted at Harvard Medical School, Cannon demonstrated that survival depends on maintaining internal stability via intricate regulatory mechanisms [

20]. He showed that multiple physiological systems act in concert to regulate critical parameters—such as blood glucose levels, oxygen concentration, blood pressure, and body temperature—keeping them within narrow physiological ranges [

24].

Cannon’s work was revolutionary for the life sciences, providing a unifying principle that explains diverse physiological processes. His studies highlighted the interplay among the autonomic nervous system, endocrine glands, and various organ systems in maintaining homeostatic balance. Furthermore, Cannon bridged physiology and psychology by demonstrating the intimate connection between emotional states and physiological responses, laying the foundation for subsequent research in psychosomatic medicine and stress physiology [

20].

Importantly, Cannon’s insights profoundly influenced Selye’s development of the General Adaptation Syndrome and the concept of the stress response, as well as subsequent studies on stress responses in plants and at the cellular level, topics that will be explored in subsequent sections.

4. Hans Selye’s Original Concept

4.1. Selye’s Concept of Stress

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the term "stress" in physics refers to the interaction between an applied force and the resistance counteracting that force. Hans Selye (1907–1982) was the first to introduce this term into the medical lexicon, defining stress as the "

nonspecific response of the body to any demand" [

25]. Often referred to as the "

Einstein of medical research" and recognized as the "

father of stress research" [

25,

26], Selye departed from the traditional approach of studying specific signs and symptoms associated with particular diseases, instead focusing on universal physiological reactions to diverse stressors.

In 1926, as a second-year medical student, Selye posed a fundamental question: "Why do patients suffering from the most diverse diseases have so many signs and symptoms in common?" and "How could different agents produce the same physiological response?" [

27]. These inquiries evolved into a broader hypothesis: "Is there a nonspecific adaptive reaction to change?" Observing that patients with various illnesses often displayed common physiological symptoms, such as loss of appetite and weight loss, Selye termed these reactions "nonspecific responses" [

28]. His groundbreaking insights laid the foundation for modern diagnostic approaches, particularly through recognizing the "alarm reaction," exemplified by fever during infectious diseases.

Because living organisms must continuously adapt to environmental fluctuations, Selye’s work provided a unifying framework for understanding bodily responses to stress—whether physical, emotional, or environmental. Over time, this concept was refined, leading to the clear distinction between the "

stressor" (the triggering factor) and the "

stress response" (the body’s adaptive reaction) [

9,

29]. His theory emphasized that the body’s response follows a consistent pattern, irrespective of the type of stressor involved (

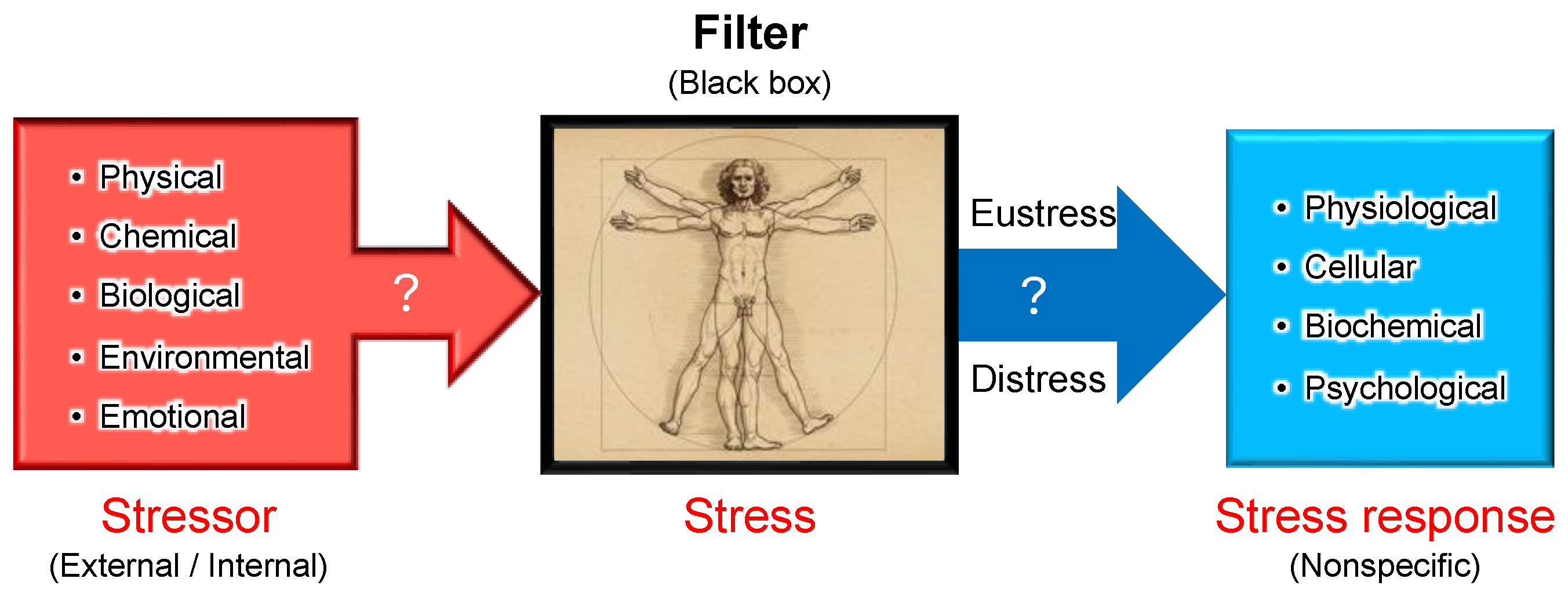

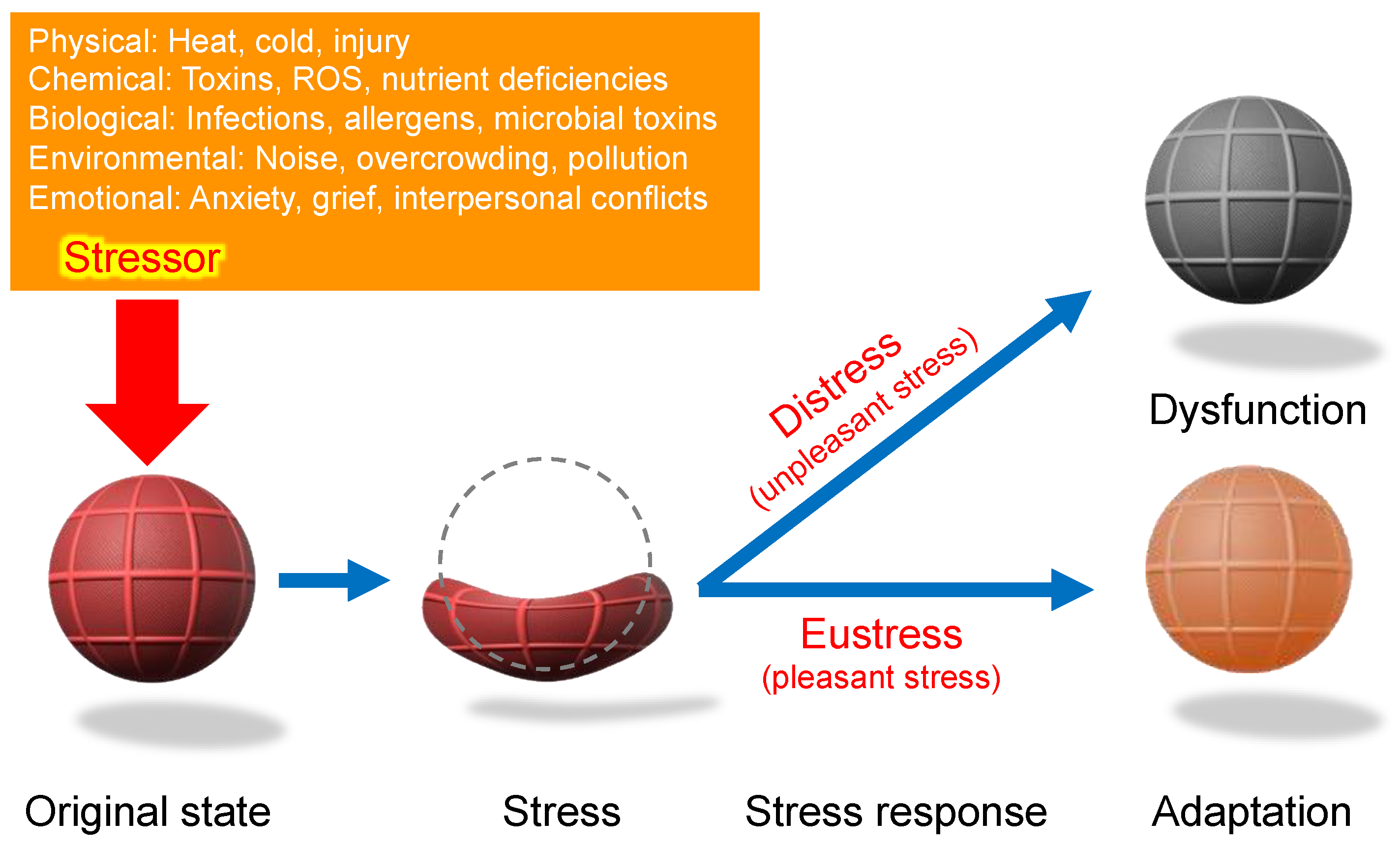

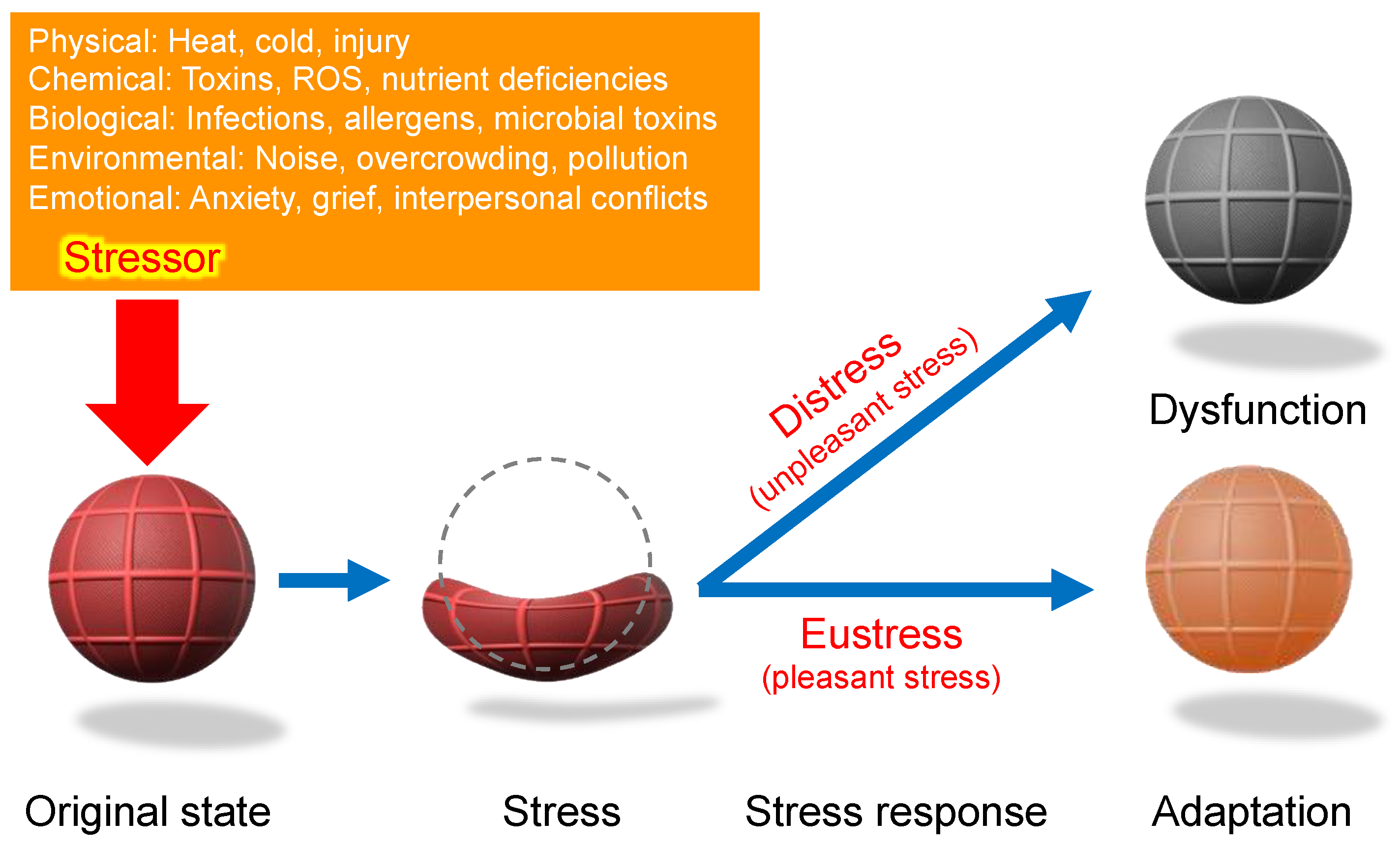

Figure 3).

According to Selye’s original concept [

27]:

- (1)

Stress is the nonspecific response of the body to any demand placed upon it.

- (2)

Stress is inevitable. To be entirely without stress is to be dead!

- (3)

Stress is not the nonspecific result of damage.

- (4)

Stress is not something to be avoided.

These fundamental principles illustrate that stress, as Selye conceptualized it, extends beyond pathological states. For example, astronauts experiencing microgravity often exhibit cardiovascular deconditioning, bone demineralization, muscle atrophy, and other physiological disruptions due to the absence of gravitational stress. This clearly demonstrates that gravitational stress is essential for maintaining physiological homeostasis, underscoring stress’s fundamental role in maintaining normal bodily function [

30].

4.2. Stress as a Biological State: Refinements

Selye emphasized the "nonspecific" nature of stress, highlighting that the body activates a similar set of general adaptive mechanisms regardless of the type of stressor—whether physical injury, emotional distress, or infection (

Figure 3). This adaptive process underpins the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS), described by Selye in three distinct stages [

1]:

- (1)

Alarm Stage, characterized by an initial acute response, often exemplified by symptoms like fever during infections.

- (2)

Resistance Stage, where adaptation mechanisms stabilize physiological functions.

- (3)

Exhaustion Stage, where prolonged or excessive stress exceeds the body’s adaptive capacity, potentially leading to dysfunction or disease.

Although Selye’s original research primarily addressed human physiology and medicine, his concept of stress reveals a broader biological phenomenon, intrinsic to all living organisms. Biological stress is defined by biochemical, molecular, and systemic adaptations rather than purely mechanical deformation. Unlike physical stress, which commonly implies deformation or damage, biological stress encompasses complex adaptive responses that support organismal survival.

Research advances have expanded the concept of stress beyond mammals to include plants, bacteria, and ecological interactions, demonstrating that stress responses are fundamental and evolutionarily conserved across biological kingdoms. For example, in butterflies, wing color patterns are influenced by pupal temperature stress, a phenomenon linked to a humoral factor [

31,

32]. In plants, drought stress activates hormonal signaling pathways, such as the abscisic acid (ABA) pathway [

33], which is functionally analogous to stress hormone regulation in animals. Similarly, bacteria exhibit adaptive responses to environmental stressors [

34,

35], further highlighting the universality of stress response mechanisms across diverse biological systems.

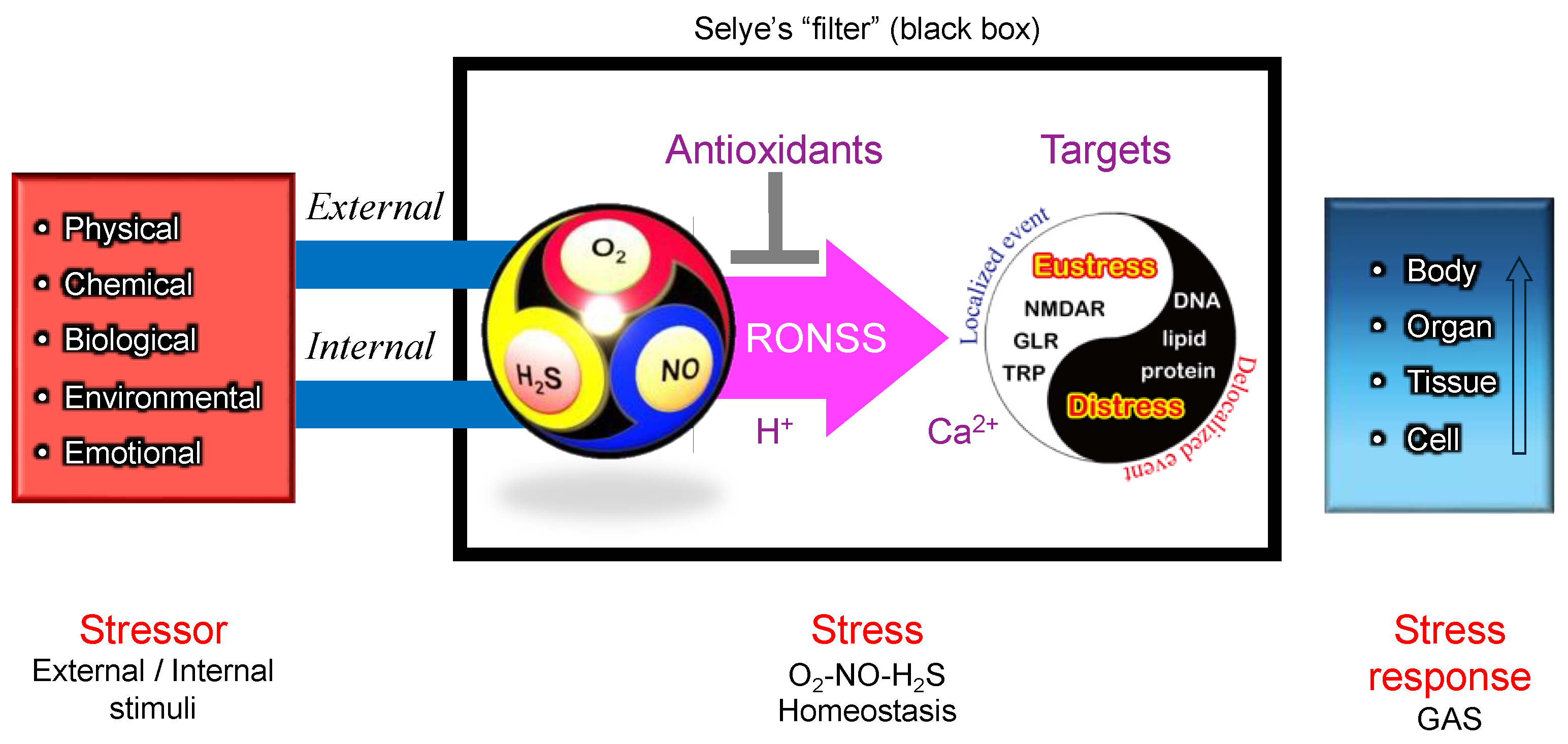

Figure 4.

Stressor-stress-stress response model. One of the unique aspects of Selye’s stress concept is his distinct definitions for the terms stressor, stress, and stress response. Unlike its usage in physics, Selye defined stress as a state of biological conditions. Regardless of the type of stressor (stimulus), the body exhibits a nonspecific and common stress response. Selye introduced the concept of a "filter" in the conversion of stressor signals into stress response mechanisms [

9]. However, the specific nature of this hypothesized "filter" remains unidentified to date.

Figure 4.

Stressor-stress-stress response model. One of the unique aspects of Selye’s stress concept is his distinct definitions for the terms stressor, stress, and stress response. Unlike its usage in physics, Selye defined stress as a state of biological conditions. Regardless of the type of stressor (stimulus), the body exhibits a nonspecific and common stress response. Selye introduced the concept of a "filter" in the conversion of stressor signals into stress response mechanisms [

9]. However, the specific nature of this hypothesized "filter" remains unidentified to date.

According to Selye’s original concept, stress is not inherently harmful; rather, it represents the body’s nonspecific response to any demand. Thus, stress responses can be adaptive (eustress) or maladaptive (distress), and distinguishing between these forms is crucial for a holistic understanding of stress in biological systems. This fundamental principle has profoundly influenced modern research, particularly in studies of oxidative stress, where the dynamic balance among reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and reactive sulfur species (RSS) is critical. Maintaining this redox balance is essential for optimal physiological functioning. Consequently, Selye’s foundational ideas continue to shape contemporary research, significantly influencing studies of oxidative stress and its impact across biological systems [

36], topics that will be explored in subsequent sections.

5. Levitt’s Concept of Stress and Strain in Plants

5.1. Plant Growth and Environment

Plants are fundamental to sustaining life on Earth, and their growth is strongly influenced by environmental factors. Historically, farmers recognized the intrinsic connection between environmental conditions and plant development, relying primarily on observational knowledge. Early agricultural practices identified key factors such as water availability, temperature, and nutrient levels as major determinants of plant growth patterns. While these early insights were largely observational, scientific research into the precise mechanisms governing plant-environment interactions gained momentum in subsequent centuries, leading to a deeper understanding of plant physiology and adaptation.

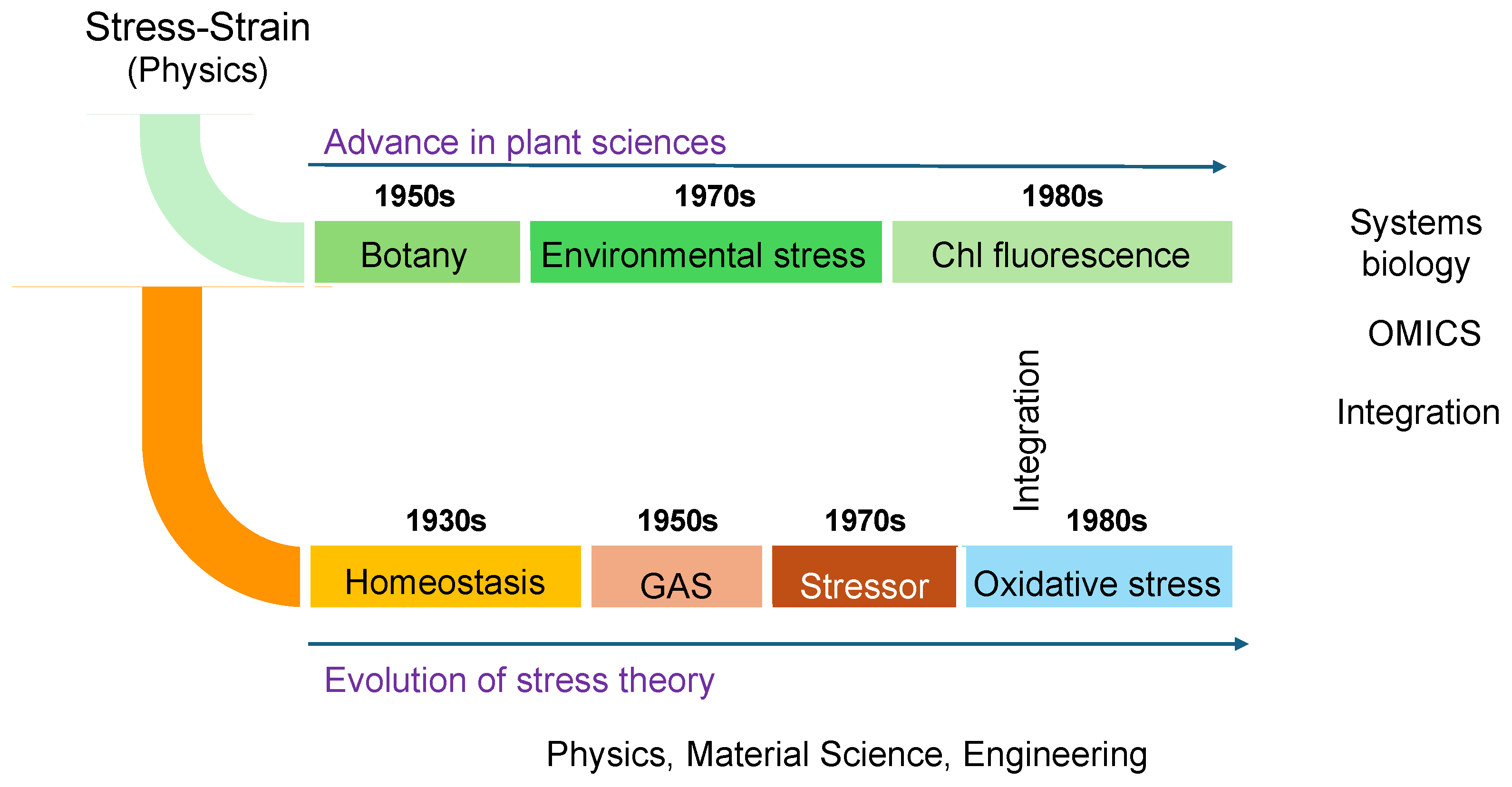

The concept of "stress" in plant science began gaining prominence only in the late 20th century (

Figure 5); however, systematic research into plant responses to environmental factors had already been underway. Early studies, primarily observational, evolved into comprehensive explorations of plant adaptation mechanisms. In this context, Jacob Levitt’s influential work provided a clear conceptualization of stress and strain in plants, laying foundational principles for contemporary plant stress physiology [

37].

5.2. Introduction of Stress and Strain to Plant Science

In his influential work published in 1972, Levitt introduced the concept of "stress" to plant science, defining two main categories: abiotic stress (e.g., drought, salinity, and extreme temperatures) and biotic stress (e.g., pathogens and herbivory) [

37]. Levitt also introduced the concept of "strain," describing it as the physical or chemical damage resulting from stress [

37]. Specifically, he defined strain as "

the physical or chemical damage produced by stress" [

37]. Furthermore, Levitt clearly differentiated stress from strain, defining strain explicitly as the measurable effects of stress on plants. He introduced critical terminology such as "environmental stress," "stress tolerance," and clarified strain as "the physical or chemical damage resulting from stress"

Levitt’s conceptual framework significantly contributed to the development of ecophysiology and environmental science, fields dedicated to understanding how plants perceive, respond to, and adapt to environmental stress within their natural habitats. However, while Selye’s theory of stress focuses on “dynamic” physiological responses, Levitt’s framework is more “static”, emphasizing mechanical perspectives similar to physics. Advances in molecular biology have shown that plant stress responses are dynamic, leading to a conceptual shift from Levitt’s mechanical framework to a physiological model akin to Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome. This shift reflects the growing understanding of oxidative stress and its role in plant adaptation, as discussed later.

While recent research has expanded our understanding of stress responses—especially regarding oxidative stress and its critical role in plant adaptation—Levitt’s terminology continues to be foundational. Terms such as "environmental stress," "abiotic and biotic stress," and "stress tolerance" remain central concepts in contemporary plant research, reflecting his enduring impact on the field.

6. Lichtenthaler’s Application of Chlorophyll Fluorescence as a Marker of Plant Stress

6.1. Four Stages of Plant Stress Responses

One advantage of adopting Levitt’s stress-strain theory in plant research is that "strain" can be quantitatively measured and easily compared in experiments. In contrast, Selye’s concept of stress lacked precise experimental tools for direct measurement in plants. Hartmut Lichtenthaler, a pioneer in plant stress research and an expert in photosynthesis, made a significant breakthrough by introducing chlorophyll fluorescence measurement as a method to detect plant stress.

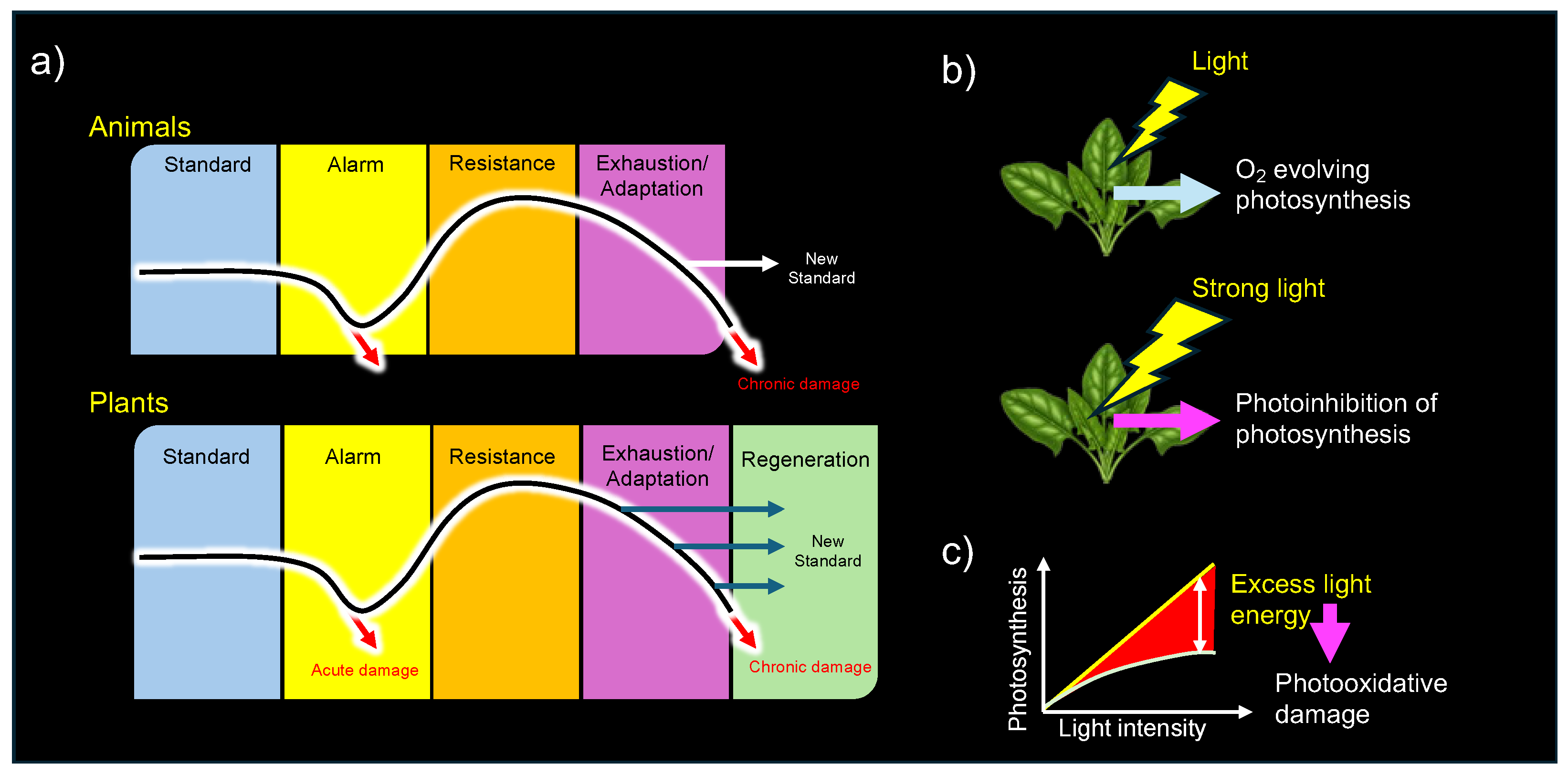

In his influential book,

The Stress Concept in Plants, Lichtenthaler revisited Selye’s foundational 1936 work and elaborated on its relevance to plant biology. He established a generalized stress framework specifically for plants, categorizing stressors and stress responses in alignment with Selye’s theory [

38,

39,

40]. Notably, Lichtenthaler expanded upon Selye’s three-stage model (alarm, resistance, and exhaustion) by introducing a plant-specific fourth stage, "regeneration" (

Figure 6a). He defined regeneration as the phase in which plants recover and establish new physiological baselines if stressors are removed at an appropriate time, before senescence becomes dominant [

38].

6.2. Chlorophyll Fluorescence as a Measure of Stress in Plants

In 1931, Kautsky and Hirsch discovered light-induced changes in red chlorophyll fluorescence from green leaves, which correlated with photosynthetic activity—a phenomenon now known as the “Kautsky effect” [

41]. In his seminal work, Murata (1969) demonstrated reversible, light-induced changes in chlorophyll fluorescence under physiological conditions [

42], thereby helping to establish a conceptual framework for photosynthetic regulation in response to light stress. This work served as an early example of the idea that the photosynthetic apparatus is not merely a passive energy collector but an actively regulated system optimized for dynamic light environments [

43].

Lichtenthaler demonstrated that changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters could effectively reveal physiological alterations induced by environmental stressors such as drought, salinity, and extreme temperatures [

38]. This technique provided a non-invasive, highly sensitive approach for studying photosynthetic efficiency and assessing plant stress status, significantly improving upon traditional destructive biochemical methods [

44]. Chlorophyll fluorescence thus became a groundbreaking tool for gaining insights into photosynthesis and assessing the functionality of the photosynthetic apparatus, particularly Photosystem II (PSII) [

45]. Environmental stressors, including drought [

46], salinity [

47], extreme temperatures [

48], and pollutants [

49] disrupt photosynthetic processes, and these disruptions can be sensitively detected by fluorescence measurements.

The impact of this method extends far beyond plant stress research. Satellite-based chlorophyll fluorescence measurements are now widely employed in remote sensing to monitor large-scale vegetation health and global carbon cycles [

50]. In ecology, chlorophyll fluorescence has become invaluable for studying plant responses to ecosystem changes driven by global climate change [

51]. In crop breeding programs, chlorophyll fluorescence facilitates the identification of stress-tolerant cultivars by efficiently evaluating photosynthetic performance under stress conditions [

46]. By offering a non-invasive and rapid screening method, this technique has accelerated the development of more resilient crop varieties.

6.3. Broad Applications and Its Limitations

The evaluation of stress using chlorophyll fluorescence has been applied not only to plants but also to symbiotic invertebrate animals. Technological advancements—such as the development of pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM) chlorophyll

a fluorometers—have enabled the monitoring of stress in reef-building corals, which rely on symbiotic photosynthetic dinoflagellates for energy production [

52]. This application is particularly important in coral research [

53], as fluorescence measurements allow researchers to assess stress levels and species-specific susceptibility to coral bleaching [

54]—a phenomenon increasingly exacerbated by global warming, climate change, and anthropogenic eutrophication [

55,

56,

57].

Despite its transformative impact, chlorophyll fluorescence measurement has notable limitations. Primarily, the method is effective at detecting distress but requires supplementary approaches to evaluate eustress adequately. Additionally, it specifically targets photosynthetic activity, potentially overlooking other stress responses unrelated to photosynthesis. This limitation also extends to non-photosynthetic organisms, such as animals and microbes, where understanding stress necessitates mechanistic insights at the cellular and molecular levels. Addressing these gaps is essential to achieving a more comprehensive understanding of stress responses across all biological systems.

7. Sies’ Concept of Oxidative Stress and Redox Biology

7.1. Discovery of Antioxidant Systems

Older textbooks often emphasized molecular oxygen (O

2) primarily for its essential role in aerobic respiration, enabling organisms to generate energy efficiently. However, in 1969, McCord and Fridovich [

58] made a groundbreaking discovery by identifying superoxide dismutase (SOD)—the first enzyme known to neutralize radical oxygen species—marking a major advance in redox biology [

59]. Another historical milestone in early redox biology research was provided by Sies and Chance in 1970 [

60], who were the first to describe that hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) as a normal physiological metabolite in eukaryotic cells and organs. This was detected as a steady-state level of catalase compound I [

61]. These findings laid the foundation for further investigations into "oxygen toxicity" [

62,

63] revealing the potentially harmful effects of oxygen at the molecular level [

63]. Subsequently, highly reactive oxygen-derived molecules, such as superoxide radicals (O

2•–) and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), were initially classified as "active oxygens" or "reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI)" and are now commonly referred to as reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

64]. It soon became evident that, without effective neutralization, ROS could induce substantial cellular damage [

65,

66].

7.2. Oxidative Stress as Imbalance Between Oxidants and Antioxidants

In 1985, Helmut Sies introduced the concept of "oxidative stress" in his influential book,

Oxidative Stress [

67], profoundly transforming our understanding of stress responses across biological kingdoms. Sies shaped the field of redox biology by elucidating the intricate balance between ROS generation and antioxidant defense mechanisms, fundamentally reshaping the understanding of stress responses at the molecular level [

61]. Importantly, his definition of oxidative stress highlighted not only its role in pathological processes but also its function as a regulatory mechanism within cellular signaling networks.

Sies’s most significant contribution was defining "oxidative stress" as "an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants in favor of the oxidants, leading to a disruption of redox signaling and control and/or molecular damage" [

67,

68]. This refined definition underscores oxidative stress as a double-edged sword—not merely a cause of molecular damage but also a key modulator of physiological signaling processes [

13].

Helmut Sies was among the first to identify H

2O

2 as a signaling molecule, demonstrating its function as a second messenger in cellular signal transduction pathways [

69]. His pioneering research laid the foundations of redox biology, emphasizing the dual role of ROS—harmful when excessive (oxidative distress) but essential at physiological levels for adaptive responses (oxidative eustress) [

13,

36]. For example, ROS generation is not inherently detrimental; it plays a crucial role in cellular signaling cascades, regulating transcription factors and enzymatic activities. However, sustained ROS overproduction can lead to oxidative damage, resulting in cellular dysfunction, aging, and disease pathogenesis. This dual concept has been validated in diverse biological systems, including plants [

70,

71] and bacteria [

72], reinforcing the evolutionary significance of oxidative stress adaptation.

Recent research has provided extensive insights into cellular defense mechanisms against ROS-induced damage, particularly through the characterization of antioxidant systems [

73]. However, Sies’s work clearly distinguishes the dual nature of ROS—damaging at high concentrations yet indispensable at physiological levels for cellular homeostasis, signaling, and adaptation [

36]. This perspective has driven advancements in antioxidant-based therapeutic strategies [

74], biomarker development for oxidative stress monitoring [

75], preventive approaches in medicine [

13,

36] and bridging a theoretical gap between psychosocial work stress and coronary heart disease (CHD) [

76].

Thus, Helmut Sies’s pioneering contributions established the foundations of modern redox biology, profoundly enhancing our understanding of oxidative stress, cellular homeostasis, and stress adaptation across diverse organisms.

8. Photooxidative Stress in Plants: The Origin of Oxygen Toxicity

8.1. Oxygenic Photosynthesis as the Origin of Oxygen Toxicity

The Great Oxygenation Event (GOE), approximately 2.4 billion years ago, is widely recognized as a pivotal moment in biological evolution [

77,

78]. This event dramatically transformed Earth’s atmosphere, facilitating the emergence of aerobic organisms dependent on molecular oxygen (O

2) for respiration. A critical biological innovation during this period was the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis in ancestral cyanobacteria, which utilized water (H

2O), instead of hydrogen sulfide (H

2S), as an electron donor for light-driven electron transport [

78]. This fundamental transition drastically changed Earth’s atmosphere by increasing O

2 concentration and simultaneously introduced oxidative stress, profoundly influencing the physiology of modern-day plants and animals.

Even oxygen-evolving plants themselves face significant challenges from photooxidative stress [

79], which occurs when the absorption of light energy exceeds the photosynthetic regulatory capacity (

Figure 6c). Such an imbalance between energy supply and metabolic demand leads to excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

80].In 1951, Mehler demonstrated that O

2 acts as an electron acceptor (Hill oxidant) in the photosynthetic electron transport chain of chloroplasts. This reaction, involving the one-electron reduction of O

2 to form O

2•–, was measured as light-induced O

2 uptake in isolated thylakoid membranes or disrupted chloroplasts [

81]—a process now known as the Mehler reaction [

82]. Since chlorophylls are known to undergo rapid photobleaching when extracted from thylakoid membranes using organic solvents, it is evident that thylakoid-embedded chlorophylls are protected by internal mechanisms that mitigate ROS generation during light exposure [

83].

In 1975, Takahama and Nishimura demonstrated that singlet oxygen (

1O

2) is formed within the photosystems, initiating lipid peroxidation [

84,

85]—a pioneering study in the field of photooxidative damage in chloroplasts. They further showed that photosynthetic pigments such as carotenoids act as internal quenchers of

1O

2, thereby protecting the photosystems from oxidative damage [

86].

In the 1970s, Kaiser elucidated that H

2O

2, the reaction product of SOD reaction of O

2•–, reversibly inhibits photosynthetic enzymes, particularly those containing thiol groups. He also showed that this inhibition could be reversed by the thiol-reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) [

87,

88].

These pioneering studies provided crucial insights into the photooxidative damage (photooxidative distress) and regulatory roles of ROS generated during photosynthesis (photooxidative eustress) in plants.

8.2. Plant Antioxidant Systems and Human Health

In 1976, Foyer and Halliwell proposed that ascorbate (vitamin C) functions as a ROS scavenger in conjunction with glutathione [

89]. Subsequently, Asada et al. identified ascorbate peroxidase (APX), an enzyme that removes H

2O

2 using ascorbate, functionally analogous to glutathione peroxidase (GuPX) in animals. They also characterized associated enzymes involved in regenerating ascorbate using NADPH [

90]. The chloroplast ROS detoxification pathway, originally termed the "Halliwell–Asada cycle" [

91], is now more commonly known as the ascorbate-glutathione cycle [

83,

92].

While it has long been recognized that consuming fruits and vegetables prevents scurvy—a disease caused by vitamin C deficiency [

63]—a fundamental question remained: Why do plants accumulate high levels of vitamin C in their tissues? The oxidative stress concept provides a compelling explanation, bridging plant biology and human health sciences. It offers scientific validation for the health benefits of a plant-based diet, highlighting the protective effects of abundant plant-derived antioxidants against oxidative distress and related diseases in humans [

93,

94].

In plants, these antioxidants are crucial for protecting the photosynthetic machinery from photooxidative damage, thereby enhancing survival in their natural habitats [

51]. According to the stress concept, plant species that evolved under high levels of photooxidative stress, including ultraviolet (UV) radiation [

95], are more likely to have enhanced nutritional and medicinal properties. However, this aspect has been largely overlooked in nutritional science and herbal medicine.

8.3. Unification of Plant and Animal Stress Responses by Oxidative Stress

Helmut Sies’s oxidative stress concept has had a profound impact on plant biology, particularly in understanding plant responses to environmental and physical stressors [

96]. His work demonstrated that oxidative stress is a universal principle applicable across biological kingdoms [

97], thus providing a unified framework for understanding cellular stress responses in both plants and animals. This concept has significantly advanced our understanding of ROS signaling networks in plants [

83,

98], particularly in response to environmental stresses [

96], and has deepened our comprehension of photooxidative stress in chloroplasts and its role in photosynthetic regulation.

9. Expanding Universe of Redox Biology

9.1. Updating Oxidative Stress: Integration of Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) and Reactive Sulfur Species (RSS)

The concept of oxidative stress has effectively bridged plant biology and human health sciences, particularly regarding disease prevention and stress adaptation, thereby unifying diverse biological systems within the framework of redox biology. Over time, this field has expanded significantly beyond its initial emphasis on ROS.

Historically, oxidative stress research primarily focused on ROS-mediated cellular responses. However, recent advancements have substantially broadened this perspective by recognizing the crucial roles of other reactive species, including reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and reactive sulfur species (RSS), in cellular redox homeostasis. These discoveries have fundamentally reshaped our understanding of redox regulation, revealing a more complex and interconnected network of reactive molecules that influence cellular functions.

This evolution has provided a nuanced understanding of how these diverse reactive species interact to regulate cellular physiology, underscoring the inherent complexity of redox biology.

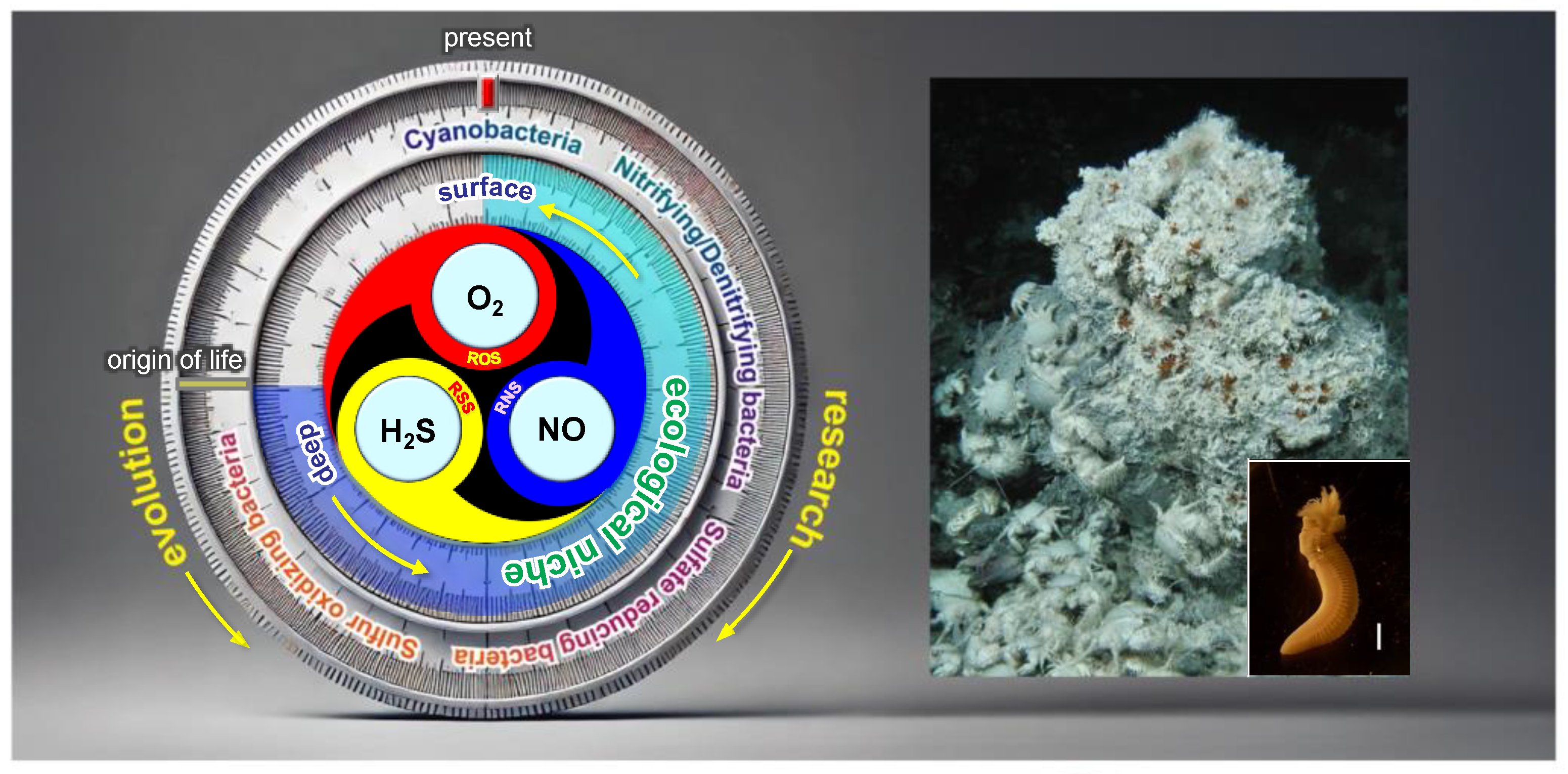

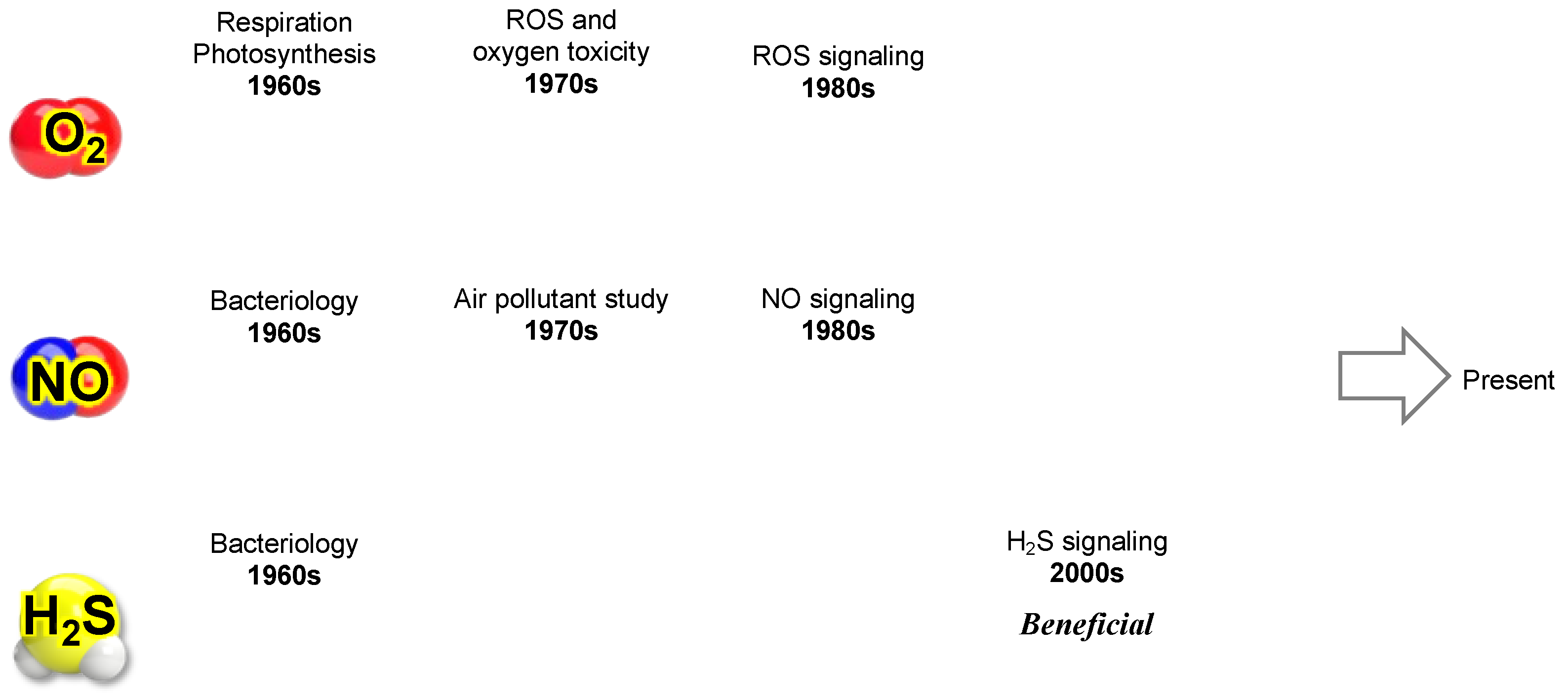

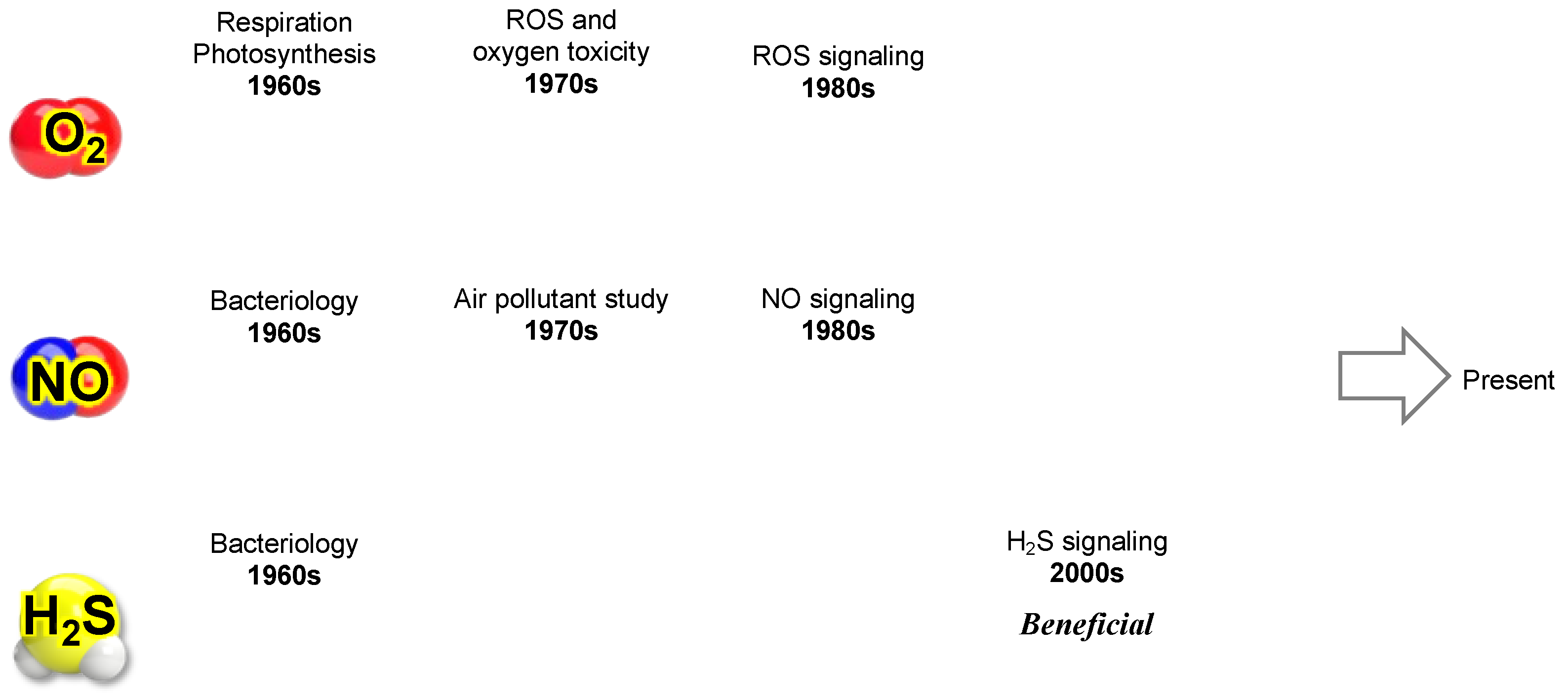

Figure 7 summarizes the evolving perception of three key gaseous molecules—molecular oxygen (O

2), nitric oxide (NO), and hydrogen sulfide (H

2S)—as our knowledge has advanced within redox biology.

9.2. Integration of Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS)

9.2.1. Nitric Oxide (NO) as a Signaling Molecule

Initially, nitric oxide (NO), along with nitrogen dioxide (NO₂), was recognized primarily as a harmful air pollutant (collectively referred to as NOx), anthropogenically produced from fossil fuel combustion by industries, automobiles, and cigarette smoke. Consequently, early NO research emphasized its cytotoxic effects on animals [

99] and plants [

100]. A major turning point occurred when Furchgott and Zawadzki (1980) discovered that endothelial cells produce an unknown factor responsible for vascular relaxation, termed "endothelium-derived relaxing factor" (EDRF) [

101]. It took several years before this unknown factor was identified as the previously known air pollutant, NO.

Pioneering research by Ignarro [

102], Furchgott [

103], Murad [

104] and Moncada [

105] ultimately revealed that EDRF was indeed NO. Their discoveries led to the identification of the L-arginine-dependent NO synthase (NOS) enzyme and its associated cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) signaling pathway, fundamentally altering the understanding of cellular signaling [

106]. This finding challenged prior assumptions and established NO as a key biological messenger. Recognized as one of the most significant biomedical discoveries of the 20th century, NO was named “Molecule of the Year” in 1992 [

107], and its role in biology was further celebrated with the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1998.

Since then, NO has transitioned from its early reputation as a toxic air pollutant to a crucial biological signaling molecule, profoundly influencing cellular communication and leading to diverse therapeutic applications. Examples include sildenafil (Viagra) for treating erectile dysfunction [

108], NO therapy for neonatal pulmonary hypertension [

109], and its therapeutic use in severe cases of coronavirus infectious disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection [

110,

111].

9.2.2. Alternative Mechanisms of NO Production

In plants, initial studies mirrored those in animals, primarily investigating the inhibitory effects of NOx on growth until the late 1990s [

100]. Although plant researchers initially presumed the existence of a mammalian-type NOS enzyme in plants [

112,

113] , extensive studies demonstrated that neither mammalian-like NOS [

112], the proposed plant-specific inducible NOS ("plant iNOS") [

114], nor the putative "AtNOS1" protein [

115] displayed true NOS enzymatic activity [

114,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120].

In 1999, we demonstrated an alternative enzymatic pathway by showing that plant nitrate reductase (NR) possesses nitrite reductase (NiR) activity, catalyzing the NADH-dependent reduction of nitrite (NO

2–) to produce NO [

121]. This mechanism was later confirmed in unicellular algae [

122]. Concurrently, Gladwin et al. identified a similar nitrite-dependent NO production mechanism in mammals, involving deoxyhemoglobin [

123,

124]. This nitrite-based pathway, termed the "nitrite-nitrate-nitric oxide pathway" [

125] or the "reductive pathway," contrasts with the "oxidative pathway" mediated by NOS in the presence of oxygen and L-arginine [

126].

In plants, the NR-dependent NO production pathway plays crucial roles in regulating physiological processes, including stomatal movement [

127,

128], root development [

129], and stress responses [

130] , especially under low-oxygen conditions such as flooding [

131,

132]. Similarly, in bacteria, NiR-mediated NO production is integral to denitrification [

133]. Mammalian enzymes such as xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR), a molybdenum-containing enzyme, also catalyze NO formation from nitrite under hypoxic conditions [

134]. Unlike oxygen-dependent NOS-mediated NO synthesis [

135], the nitrite-dependent pathway is particularly relevant under conditions of low oxygen availability [

124,

136].

As humans are incapable of synthesizing inorganic nitrite or nitrate (except as oxidation products of endogenous NO), these findings underscore the nutritional importance of consuming nitrate-rich vegetables as dietary sources of NO precursors. Such dietary intake is essential for maintaining vascular health and may also play a role in protecting against infectious diseases, including COVID-19 [

137].

9.3. Expanding Roles of Reactive Sulfur Species (RSS)

9.3.1. H2S as the Third Gasotransmitter

Alongside the paradigm shift in our understanding of NO and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), the biological significance of sulfur-containing molecules—particularly hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) and its derivatives—has undergone a dramatic transformation in recent decades [

138,

139]. Previously regarded primarily as a toxic gas and occupational hazard, the perception of H₂S has shifted profoundly with increasing recognition of its critical biological roles [

140].

Historically, research on H2S focused predominantly on its toxicity, especially in occupational settings, leading many countries to establish strict safety guidelines (e.g., limiting exposure to 10 ppm for up to 10 minutes). However, the biological significance of H2S changed dramatically following discoveries in recent decades.

A major breakthrough in the field came in 1996, when Abe and Kimura demonstrated that H

2S is endogenously produced from L-cysteine in mammalian brain homogenates [

141]. This finding marked a paradigm shift, establishing H

2S as the third recognized gasotransmitter, alongside NO and carbon monoxide (CO) [

142].

9.3.2. Endogenous H2S Production in Plants and Animals

Under physiological conditions, H

2S exists in multiple forms, including fully protonated hydrogen sulfide (H

2S), hydrosulfide anion (HS

–), and polysulfides (HS

n–). Endogenous production of H

2S in animals primarily involves enzymes such as cystathionine

β-synthase (CBS) [

141], cystathionine

γ-lyase (CSE) [

139], and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) [

143]. Research in RSS biology and medicine continues to expand, revealing numerous physiological roles in both plants [

144,

145] and animals [

36], highlighting significant therapeutic potential [

138,

146].

9.3.3. Plant-Derived Sulfur Compounds and Human Health

Recent research has highlighted that, in addition to plant-derived antioxidants such as ascorbate and polyphenols [

147], sulfur-containing compounds play a crucial role in mitigating oxidative stress-related disorders in humans. Sulfur-rich vegetables (e.g., garlic, onions, and cruciferous vegetables) contain organosulfur compounds such as allicin ((

2E)-prop-2-ene-1-sulfinothioic acid

S-2-propenyl ester) and sulforaphane (1-isothiocyanato-4-(methylsulfinyl) butane), which regulate redox balance and have been implicated in cancer prevention [

148,

149], cardiovascular health [

150], and neuroprotection [

151]. Understanding plant redox adaptations can thus provide valuable insights into dietary interventions and pharmacological strategies for combating oxidative stress-related diseases in humans [

144].

9.4. Interplay Among ROS, RNS and RSS

9.4.1. O₂-NO-H₂S (ONS)

Table 1 lists representative ROS, RNS, and RSS derived from O₂, NO, and H₂S. It is important to note that ROS, RNS, and RSS—collectively referred to as RONSS [

152]— exist as neutral radicals (e.g., •OH and NO), some as radical ions (e.g., O

2•– and ONOO

–), and others as non-radical species (e.g., H

2S and H

2O

2) [

67]. In principle, ionic forms of RONSS, such as O

2•– and other charged molecules, cannot diffuse across membranes without the assistance of ion transporters, the characteristic determining their roles and cellular impacts [

152]. We suggest that these abbreviations (ROS, RNS, RSS) serve primarily as a reference to their original molecular sources—O₂, NO, or H₂S (ONS)—rather than an indication of specific chemical properties or cellular functions.

9.4.2. Cysteine Thiol at the Crossroad of Redox Interactions

Integrating RNS and RSS into the oxidative stress paradigm has provided a more comprehensive understanding of cellular redox biology [

11]. Importantly, these reactive species do not function independently; rather, they engage in extensive chemical crosstalk, modulating signaling pathways and stress responses. The diverse array of reaction products arising from interactions among ROS, RNS, and RSS further complicates both in vivo chemical reactions and their physiological implications.

For example, the reaction between superoxide (O

2•–) and nitric oxide (NO) produces peroxynitrite (ONOO

–), one of the most cytotoxic RNS, implicated in both "nitrosative (R–NO) stress" [

153] and “nitrative (R–NO

2) stress” [

154]. Among critical redox modifications,

S-nitrosylation (Cys–SNO)—a post-translational modification involving the covalent addition of NO to cysteine thiol (–SH) groups—has emerged as a significant regulatory mechanism in redox biology, extensively studied in both plants [

155] and animals [

156,

157,

158,

159,

160]. This process underscores the intersection between ROS and RNS, demonstrating their interconnected roles in cellular regulation [

161,

162,

163].

Subsequent research identified RSS, specifically persulfides (RSSH) and polysulfides (RSS

n–), as endogenously produced molecules forming glutathione persulfide (GSSH) and cysteine persulfide (Cys–SSH) [

164], along with various polysulfide derivatives in mammalian cells [

146]. These RSS compounds interact readily with H

2O

2, further highlighting their biological significance [

164]. Moreover, hybrid reactive species arising from NO–H

2S interactions have been identified as pivotal regulatory molecules [

165], underscoring the intricate chemical interplay among multiple reactive species and their diverse physiological outcomes.

Table 2 shows representative thiol modifications mediated by ROS, RNS, and RSS. Cysteine thiols (–SH) within glutathione and proteins occupy a central position in redox biology, crucially influencing stress responses and cellular homeostasis. Increasing evidence indicates that cysteine thiol modulation serves as a molecular switch mechanism, dynamically regulating redox-sensitive cellular processes [

166]. Consequently, the diversity of cysteine thiol modifications represents a molecular signature or "snapshot" of dynamic redox interactions between RONSS and antioxidants.

9.4.3. The Three-Body Problem in Stress Biology: Dynamic Interplay of ONS

In classical mechanics, the three-body problem describes a system in which gravitational interactions among three celestial bodies lead to nonlinear, unpredictable motion [

167]. Unlike simpler two-body systems, three-body interactions often generate chaotic, emergent behaviors, making long-term predictions highly complex. A similar conceptual challenge arises in redox biology, where the interactions among ROS, RNS, and RSS create intricate and nonlinear biochemical dynamics.

Each reactive species—ROS as oxidants, RNS as nitrogen-based signaling intermediates, and RSS as redox-active sulfur compounds—has well-characterized individual functions. However, their interplay introduces an additional layer of complexity, often leading to highly variable physiological and pathological outcomes. Just as gravitational perturbations in three-body systems result in dynamically shifting equilibria, chemical cross-reactivity among ROS, RNS, and RSS continuously modulates cellular redox homeostasis.

We propose conceptualizing the redox interplay of O2, NO, and H2S—the primary molecular sources of ROS, RNS, and RSS—as a three-body problem in stress biology. Unlike conventional oxidant-antioxidant interactions, this triad introduces nonlinear, context-dependent dynamics, making stress adaptation highly variable across organisms and environmental conditions. While ROS, RNS, and RSS have distinct roles in oxidative signaling, their cross-reactivity produces emergent outcomes that vary across biological contexts.

For example, NO reacts with O2•– to form ONOO⁻, a reactive nitrogen species with distinct physiological and pathological effects from its parent molecules. Similarly, H2S modulates redox signaling through persulfidation of protein thiols, influencing downstream ROS and RNS pathways in a context-dependent manner. This intricate biochemical interplay results in stochastic, self-regulating dynamics, resembling the unpredictable yet interdependent nature of three-body interactions in physics.

Deciphering this complexity requires not only integrating systems biology approaches but also adopting holistic perspectives to fully grasp the emergent properties of these intricate biochemical networks. By applying this three-body problem analogy to stress biology, we can gain deeper insights into how cellular redox homeostasis dynamically adapts to environmental and physiological challenges.

10. Ecological Perspectives: Stress and Neurodegenerative Diseases

10.1. Environmental Stressors and Neurodegeneration

Chronic exposure to environmental stressors is implicated in various neurodegenerative diseases through mechanisms involving oxidative damage, inflammation, and protein aggregation [

168,

169,

170]. Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) provides a foundational framework in physiology and psychiatry; however, a significant gap remains in understanding how diverse stressors trigger generalized adaptive responses, particularly in psychiatric and neurodegenerative conditions. This unresolved question was one that Selye himself pondered, especially regarding how different stressors could lead to similar pathological outcomes.

A striking historical example is the unusually high incidence of the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/Parkinsonism-dementia complex (ALS/PDC), also known as Lytico-Bodig disease, among the Chamorro population in Guam during the mid-20th century [

171]. Epidemiological stuides from the 1950s and 1960s indicated that the incidence of ALS/PDC in Guam was up to 100 times higher than global averages [

172]. This unique geographical clustering prompted intensive scientific inquiry into environmental factors, eventually leading to the β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) hypothesis.

10.2. Natural Neurotoxin BMAA: Linking Disease and Environment

One of the most compelling hypotheses for the cause of Lytico-Bodig disease was chronic dietary exposure to β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), a neural toxin produced by cyanobacteria. The Chamorro people traditionally consumed the seeds of cycad plants (Cycas micronesica), which were later found to contain high levels of BMAA.

Additionally, the traditional Chamorro diet included flying foxes (Pteropus mariannus), which fed on cycad seeds, leading to even greater BMAA bioaccumulation in brain tissues [

173]. The BMAA hypothesis thus provided the first compelling biochemical mechanism linking environmental stress to neurodegeneration [

172].

10.3. BMAA and Cyanobacterial Blooms: Global Health Implications

Initially, BMAA was thought to be exclusively produced by certain cyanobacteria (Nostoc spp.) living symbiotically with cycads [

174] and the water-floating fern Azolla [

175,

176]. Subsequent research, however, revealed that various cyanobacteria can produce BMAA [

177], and its bioaccumulation has been detected in multiple organisms, including seafood [

178], vegetables [

179], and even drinking water [

180].

A recent study reported BMAA accumulation in the brains of wild dolphins exhibiting abnormal behavior before death. Postmortem analyses revealed an increased number of β-amyloid

+ plaques and dystrophic neurites in the auditory cortex, reinforcing a potential link between chronic environmental BMAA exposure and neurodegenerative pathology [

181]. These findings underscore the global health risks posed by cyanobacterial blooms, suggesting a potential impact of environmental BMAA exposure on human neurodegenerative diseases [

178].

Lytico-Bodig disease has highlighted the connection between environmental stress and human health. Cyanobacteria are primitive organisms with no direct evolutionary relationship to humans, the most highly evolved animals. Although the biological function of BMAA in cyanobacteria remains obscure [

182,

183,

184], a considerable number of studies have suggested that BMAA interacts with N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in neural cells of animals [

172,

185,

186].

11. Minimum Machinery for Nonspecific Stress Response

11.1. Multi-Sensitivity of NMDARs

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) are essential glutamate receptors (GluRs) that mediate the majority of excitatory neurotransmission in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS) [

187]. They play a pivotal role in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory formation, while also contributing to excitotoxic neuronal cell death in various acute and chronic neurological disorders [

188].

NMDARs belong to the ionotropic glutamate receptor (iGluR) family, which is further subdivided into α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA), kainate, and NMDA receptor channels [

187]. These iGluRs are widely distributed throughout the nervous system, with particularly high concentrations in human brain synapses.

A defining feature of NMDARs is their role in coincidence detection, requiring both glutamate binding and membrane depolarization to remove the Mg

2+ block, thereby permitting Ca

2+ influx [

189]. This dual gating mechanism enables NMDARs to integrate pre- and postsynaptic activity, making them essential for synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation (LTP) [

190,

191].

However, a well-documented paradox exists: NMDARs can either promote neuronal survival or trigger excitotoxic cell death, depending on their activation context [

192]. Dysfunction of NMDARs has been implicated in various neurological disorders, including epilepsy [

193], schizophrenia [

194], and neurodegenerative diseases [

192,

193].

Unlike traditional neurotransmitter receptors that respond solely to ligand binding, NMDARs exhibit high sensitivity to diverse external and internal factors. Their activity is tightly regulated by pH (protons) [

195], Mg

2+ [

196], Zn

2+ [

197], D-serine [

198], polyamines [

199], and histamine [

189]. Additionally, NMDAR function is influenced by redox states, particularly via oxidation of cysteine thiol (–SH) groups in receptor subunits. Consequently, NO [

200], H

2S [

201] and H

2O

2 [

202] regulate NMDAR activity via thiol modifications [

146].

Although further validation is necessary [

203], BMAA was identified as a partial agonist at the glycine-binding site of NMDARs [

204]. In the presence of bicarbonate ions (HCO

3–), BMAA enhances NMDAR activation, presumably leading to excessive Ca

2+ influx and subsequent excitotoxic neuronal damage [

205].

11.2. GLRs in Plants

Despite lacking a nervous system, plants have evolved systemic signaling mechanisms to coordinate whole-body responses to environmental challenges. These long-distance signaling pathways include electrical, Ca²⁺, ROS, and glutamate signals [

206]. Interestingly, plants possess glutamate receptor-like channels (GLRs), which are homologous to NMDARs [

207]. Similar to their neuronal counterparts, plant GLRs regulate Ca

2+ signaling in response to D-amino acids [

208], pH changes [

209], and redox modifications [

210,

211].

In plants, BMAA has been reported to induce hypocotyl elongation and inhibit cotyledon separation in light-grown seedlings [

212]. This evolutionary parallel implies that iGluRs, including their ancestral bacterial prototypes, function as sensors for environmental stressors across biological kingdoms [

207], potentially providing a universal mechanism for integrating diverse stress signals.

11.3. TRP Superfamily

The sophisticated signaling functions of NMDARs in animals and GLRs in plants suggest that they may have evolved from simpler ancestral prototypes. The transient receptor potential (TRP) superfamily represents a functional prototype of cation channels, comprising seven subfamilies: TRPC, TRPV, TRPM, TRPN, TRPA, TRPP, and TRPML [

213].

TRP channels function as "multiple signal integrators," responding to chemical, thermal, osmotic, mechanical, and oxidative stimuli [

213]. Although first discovered in

Drosophila (TRPC) as a photoreceptor-associated channel, TRP channels are conserved across biological kingdoms, including unicellular algae, fungi, and eukaryotes [

214].

The ability of TRP channels to integrate diverse environmental and intracellular signals highlights their essential role in cellular homeostasis and adaptation. In humans, TRP channels are involved not only in pain perception, vascular tone regulation, neuronal excitability, and inflammatory responses but also in various pathophysiological processes, making them critical pharmacological targets [

215,

216,

217,

218,

219].

Notably, plant-derived natural compounds, such as coumarin osthole from traditional medicinal herb

Cnidium monnieri [

220], cannabinoids from Cannabis (

Cannabis sativa) [

221], and the phytoestrogen genistein (4′,5,7-trihydroxyisoflavone) from soybeans (

Glycine max) [

222], have recently been shown to inhibit certain TRP channels [

219].These findings further support the link between plant adaptation mechanisms and human health, emphasizing the potential for plant-derived compounds to modulate TRP channel activity.

11.4. TRP Channels in Response to ONS

TRP channel activity has been reported to be regulated by O

2, NO, and H

2S. In Drosophila, TRP channel activity is enhanced by classical mitochondrial uncouplers (chemical H

+ transporter) or anoxic conditions [

223]. In the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, TRP channels are required for O

2 sensing and movement behavior [

224].

In in vitro studies, certain TRP families have been shown to induce Ca

2+ entry into cells in response to NO, through either direct S-nitrosylation of specific cysteine residues [

215,

216] or indirect mechanisms [

213]. Similarly, H

2S has been demonstrated to activate TRP channels in the brain via polysulfide formation [

146,

225]. Additionally, many TRP channel families exhibit redox sensitivity, with functional cysteine residues modulated by ROS, RNS, and RSS, further emphasizing their role as key molecular sensors of oxidative stress [

226].

11.5. The Minimum Machinery for Selye’s “Filter” Function

To maintain homeostasis, organisms must detect and respond to environmental changes. Early single-celled organisms likely encountered pH fluctuations, temperature shifts, and osmolarity stress as primary stressors. As multicellularity evolved, cell-cell communication mechanisms became essential for coordinating responses to biotic and abiotic stressors.

Since neural communication is a specialized form of cell-cell signaling [

227,

228], it is unsurprising that naturally occurring compounds from plants and algae—such as BMAA—act as neurotoxins. This suggests that neurodegenerative diseases may arise from dysfunctions in conserved cellular communication mechanisms shared across cyanobacteria, plants, and humans.

11.6. Updating Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) Model

To address the question posed in the introduction—“What molecular mechanisms enable a nonspecific response to diverse stressors?”—we propose that the multi-sensitivity of iGluRs, including NMDARs, GLRs, and TRP channels, constitutes a minimal essential system for translating diverse stress signals into Ca2+-mediated physiological responses.

In this context, these Ca

2+-permeable channels may serve as the molecular basis of Selye’s hypothesized "filter" (

Figure 4)—a mechanism that integrates various stress signals into a unified, nonspecific adaptation response.

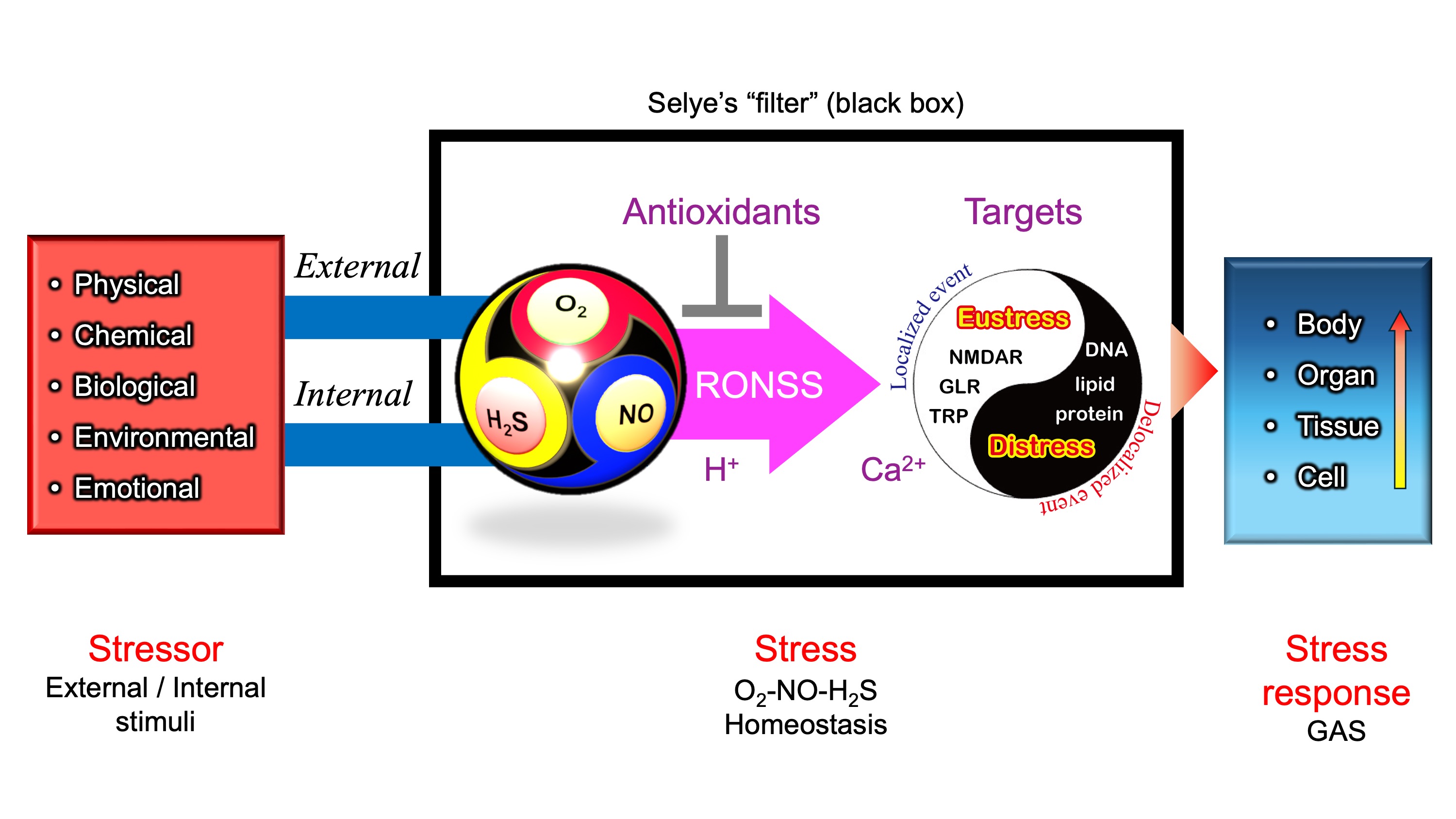

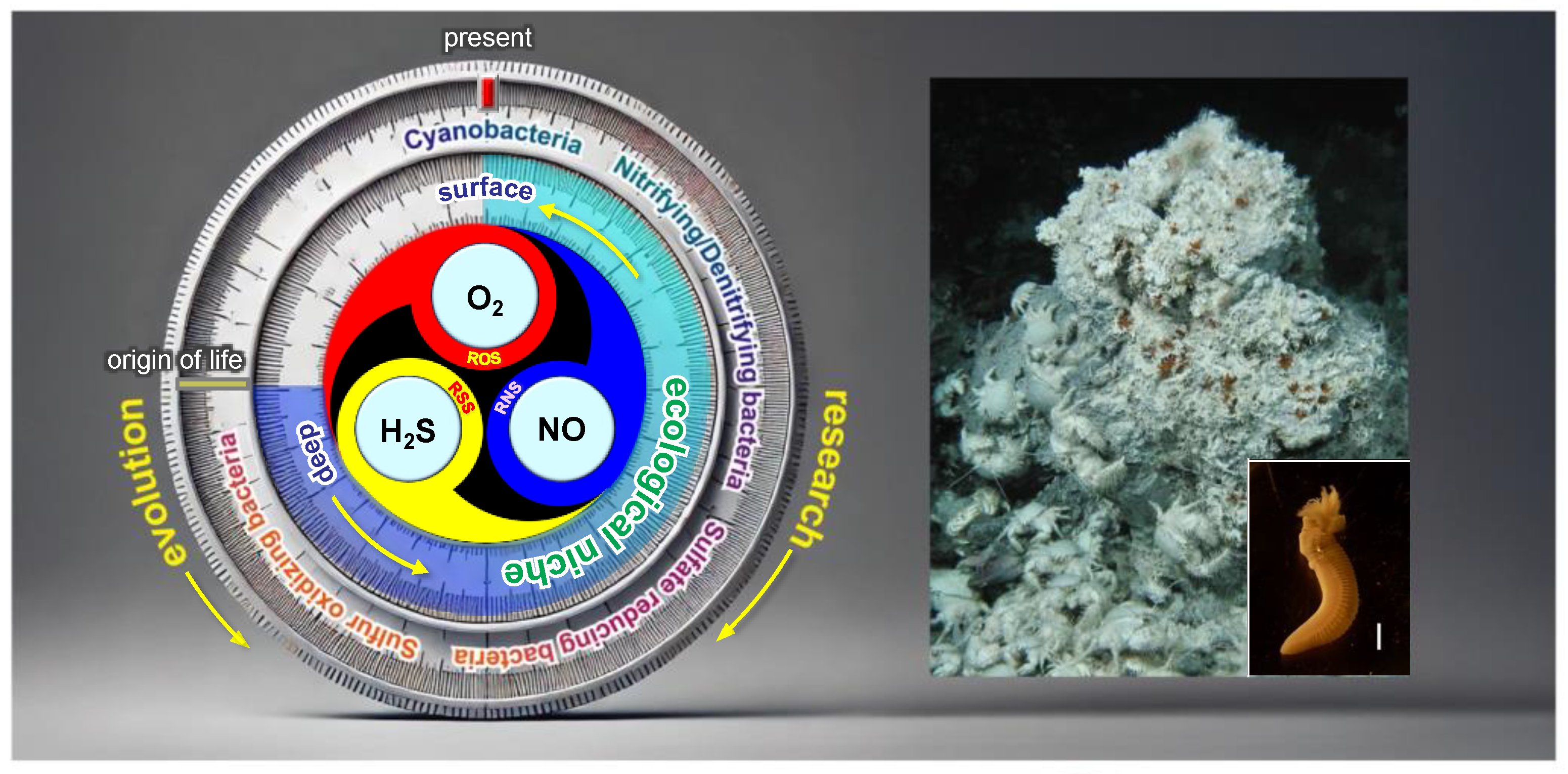

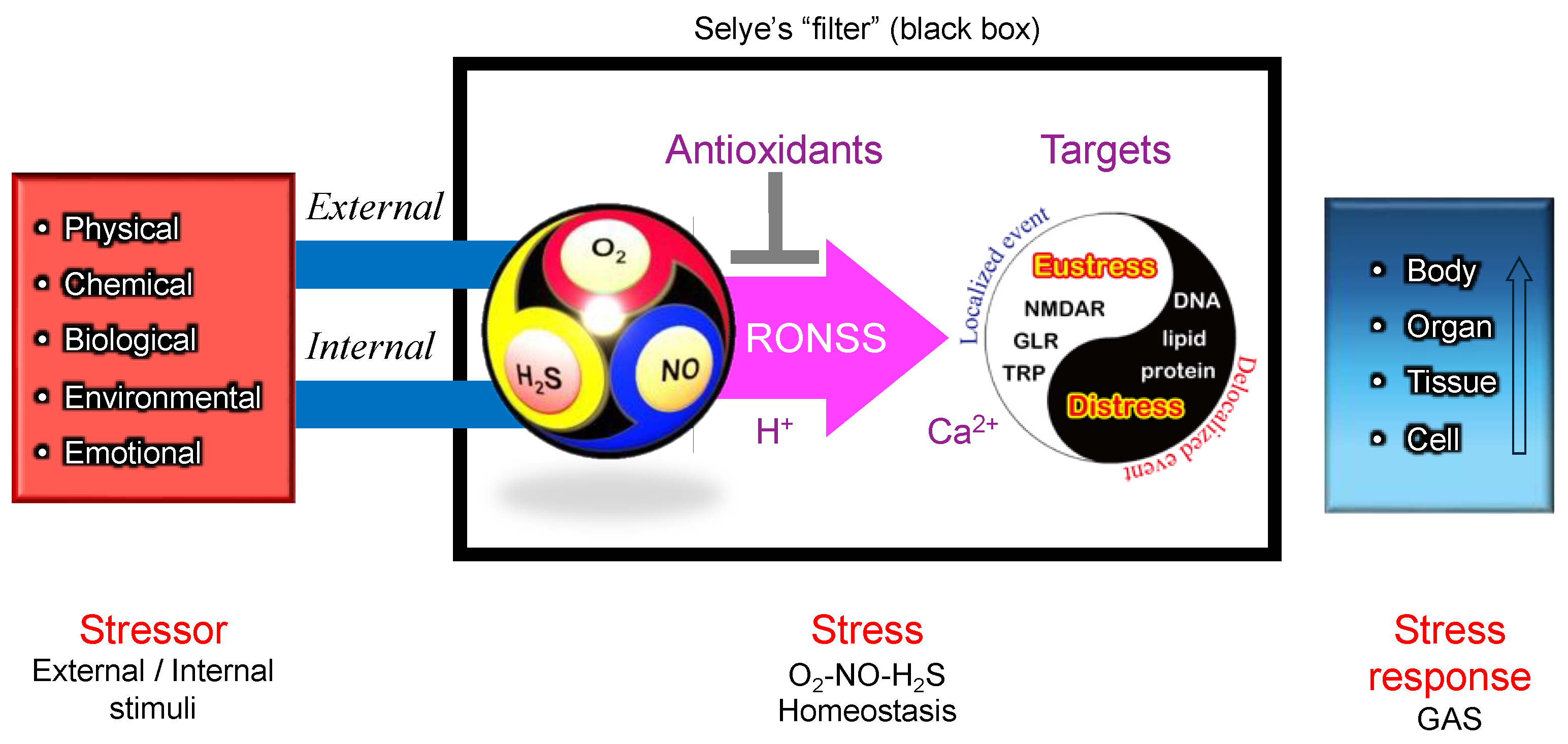

Figure 8 presents a hypothetical O

2–NO–H

2S (ONS) homeostasis model, refining Selye’s original stress "filter" concept (

Figure 4). To align with the core principles of Selye’s stress theory, a simple and universal mechanism applicable across biological kingdoms is needed. In natural environments, the relative ratios of O

2, NO, and H

2S fluctuate due to both internal metabolic activities and external environmental factors including light intensity (e.g., diurnal cycles of UV and visible light), water availability (e.g., rainfall events), temperature variations (e.g., daily and seasonal fluctuations). Additionally, biological interactions—including pathogenic, parasitic, and symbiotic relationships—further modulate the balance of these three gases.

Thiol (–SH) residues in cysteine react with ROS, RNS, and RSS (

Table 1), generating a diverse array of reaction products (

Table 2). These products function as molecular switches, transducing stimuli into physiological responses and contributing to the nonspecific stress response.

Changes in O2–NO–H2S balance, along with local pH or proton availability, should influence chemical interactions among ROS, RNS, and RSS (collectively RONSS). This leads to modifications of functional thiol groups in iGluRs, including TRP channels, NMDARs in animals, and GLRs in plants. These modifications could initiate Ca2+-dependent signaling pathways, triggering localized redox reactions (eustress).

In contrast, delocalized RONSS generation may lead to delocalized redox reactions, causing oxidative distress, physiological dysfunction, and pathological conditions [

152]. These processes are not independent but are interconnected within a delicate adaptive balance.

12. Concept of Balance Behind the Opposing Nature of Contributors to the Stress Response

12.1. Dynamic Harmony of Two Opposites

To address the second question posed in the introduction—“How can the same stressor lead to two opposing outcomes?”— here we introduce benefits to incorporate Asian philosophies into holistic persecptive underlying the principle of balance.

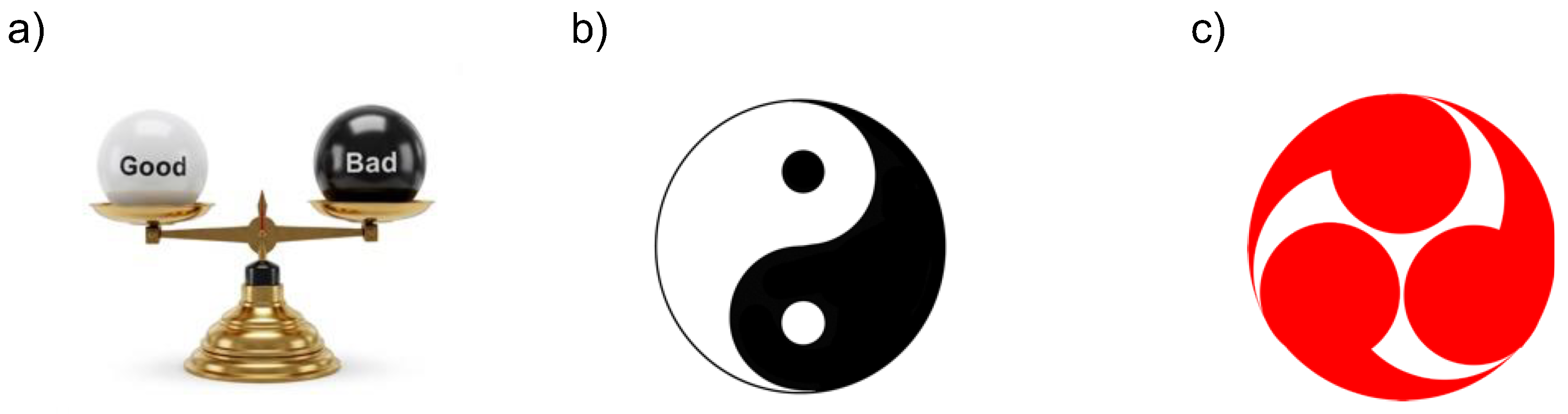

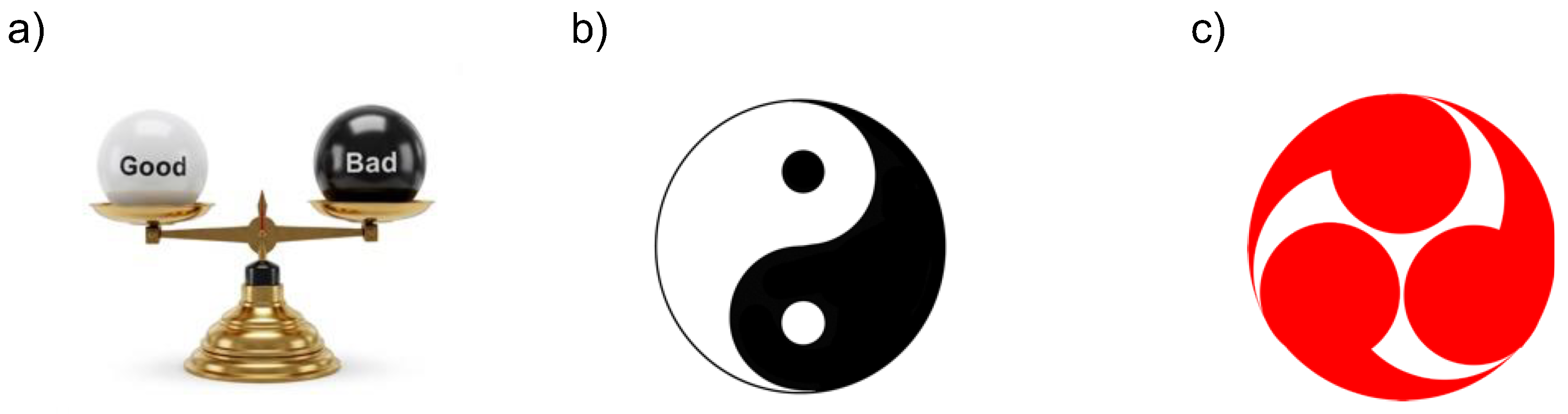

The coexistence of the opposing natures within a single entity is frequently described in scientific literature using metaphors such as "two sides of the same coin" or a "double-edged sword." Traditionally, this dual nature has been illustrated as a balance scale with two arms (

Figure 9a). Recently, however, many researchers in stress studies have adopted the Yin-Yang symbol (

Figure 9b), rather than a balance scale, to effectively represent the simultaneous presence and dynamic harmony of opposing extremes.

The Yin-Yang (light and shadow in its English translation) symbol, often associated with ancient Chinese philosophy, is a graphical representation of the concepts of dualism, balance, and interdependence in the natural world. It reflects the harmony of opposites and the idea that seemingly contradictory forces are interconnected and mutually dependent. The Yin-Yang symbol serves as a reminder of the harmony and interconnectivity of all aspects of life and the universe. It encourages the acceptance of duality and the pursuit of harmony within opposing forces, aligning well with the characteristics of key molecules in oxidative stress and the definitions of terminology in Selye’s stress concept.

12.2. Yin-Yang Principle in Modern Science

The concept of Yin-Yang has influenced numerous prominent figures in science and philosophy, leading to profound insights and applications across various disciplines. Following a visit to China in 1937, Niels Bohr, a theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to the understanding of atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922, evidently recognized the philosophical relevance of Yin and Yang to his theory of complementarity [

229]. Carl Jung’s analytical psychology incorporated Yin-Yang-like dualities, such as anima and animus, to explore the balance between the unconscious and conscious elements of the human psyche [

230]. Fritjof Capra explicitly linked modern physics with the Eastern philosophies underlying Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Shintoism, highlighting Yin-Yang as a bridge between science and Eastern thought in his book The Tao of Physics (1975) [

229].

In the 1990s, Barry Osmond, a specialist in photosynthesis, introduced the Yin-Yang symbol into photosynthetic research to represent the dynamic coexistence of two opposing forces [

231]. His philosophical influence is evident in the former logo of the Research School of Biological Sciences (RSBS) at the Australian National University, as well as in the logo of the Journal of Experimental Botany [

232]. Inspired by his philosophy, we have applied the Yin-Yang symbol to illustrate the dual nature of flavonoids (antioxidant/prooxidant) [

147], vitamin C (antioxidant/prooxidant) [

137] and NO (signaling function/cytotoxicity) [

137,

233], (nitrite/NO) [

234]. Lundberg, Weitzberg and Gladwin also apply the Yin-Yang symbol representation to account for the coexistence of oxidative and reductive mechanisms for NO synthesis [

125].

By framing their immunological observations within the Yin-Yang paradigm, Santambrogio and Franco provided a conceptual model to understand how self-tolerance and immune responses are interconnected, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a dynamic equilibrium to prevent diseases such as autoimmunity and chronic inflammation [

235]. More recently, Uvnäs-Moberg et al. discussed the interaction between the hormonal and neuronal arms of both the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the oxytocinergic system with the Yin-Yang framework [

236]. Collectively, these recent studies demonstrate the enduring relevance of Yin-Yang as a unifying principle across disciplines.

12.3. Balance of Threefold Elements: Evolution of the Yin-Yang Principle

As shown in

Figure 7, research on O

2 (ROS), NO (RNS), and H

2S (RSS) has historically progressed in parallel. It has become evident that each of these reactive molecules competes for the same targets, such as heme and cysteine thiols (–SH), in cellular regulation. At the same time, they can cause oxidative modifications to proteins, lipids, DNA, RNA, and polysaccharides, leading to metabolic dysfunction, mutations, and cell death. Each of these molecules exhibits a Yin-Yang-like continuous duality, namely, a signaling function (positive) and oxidative damage (negative).

The Yin-Yang symbol is also referred to as Taiji. As an advanced concept of the Yin-Yang principle, the threefold Taiji emphasizes the significance of dynamic interactions among three elements. Since 2005, we have advocated the need for balance between ROS, RNS, and RSS—an aspect not widely recognized at the time—for a deeper understanding of the physiological functions of these reactive molecules, adopting the Japanese Mitsudomoe [

135]. Mitsudomoe (

Figure 9c), a family crest that was once popular among samurai families, is frequently found on the roof tiles of Japanese shrines and temples. In Korea, Samtaegeuk, which evolved from Taiji philosophy, represents a triadic balance of heaven, earth, and humanity. In India, Tri-Dosha is a fundamental concept in Ayurveda (Indian traditional medicine) that explains human health and constitution through three vital energies (Doshas). The balance of these three dynamic elements remains central to both traditional Indian and Korean medicine even today. It appears that Asian countries have culturally shared a very similar philosophical concept regarding the balance of three dynamic forces.

13. Bridging Modern Science and Traditional Medicines Emphasizing Balance

13.1. Traditional Eastern Medicines

Traditional medicine in China, Korea, Japan, and India shares ancient roots but has evolved into distinct systems. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) emphasizes herbal medicine, acupuncture, and Yin-Yang theory, while Traditional Korean Medicine (TKM) incorporates Sasang Constitutional Medicine. Kampo (Japanese traditional medicine) focuses on simplified herbal formulas and integration with modern medical practices, whereas Ayurveda in India is based on the balance of three doshas (Vata, Pitta, and Kapha) and incorporates herbal treatments, diet, and yoga. These systems continue to coexist alongside modern Western medicine, with specialized professionals ensuring their continued practice.

A notable moment in the global recognition of TCM occurred in 1971, preceding President Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972. New York Times journalist James Reston, while in Beijing, underwent an emergency appendectomy and received acupuncture for post-operative pain management. His subsequent newspaper article describing the experience helped generate widespread interest in acupuncture in the United States, marking a significant moment of "East meets West" in medical history [

237].

13.2. Acupoints and Meridians

Acupuncture, acupressure, and moxibustion have been integral to TCM for thousands of years. Based on clinical trials evaluated by modern medical standards, the World Health Organization (WHO) has endorsed acupuncture for specific medical applications [

79].

Acupoints, which are central to acupuncture, acupressure, and moxibustion, are believed to possess distinct physiological properties that mediate their therapeutic effects. Surprisingly, Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine (TCVM) has documented the use of acupuncture in animals for over 3,000 years, not only in domesticated species such as horses, cattles, pigs, dogs, and cats, but also in exotic animals such as elephants and tigers [

238].

Recent research has demonstrated the presence of acupoints in frogs, lizards, birds, and even giant pandas [

238]. This suggests that animals share similar physiological responses to acupoint stimulation, further supporting the potential universality of acupuncture’s mechanisms across species.

TCM proposes that acupoints are connected through “meridians,” conceptual pathways through which the vital energy “qi” flows. Despite its demonstrated efficacy, the underlying mechanisms of acupuncture remain largely unknown, and no definitive anatomical evidence has been found to support the physical existence of acupoints or meridians. However, recent research suggests that NO may play a crucial role in these enigmatic points.

13.3. NO Generation at Acupoints

A number of studies have shown that acupoint stimulation via acupuncture enhances NO production [

239]. Su et al. investigated the role of acupuncture in modulating ROS and RNS in the context of oxidative stress and proposed that acupuncture functions as a multi-target antioxidant therapy in ischemic stroke [

240]. Ma et al. demonstrated NO generation at skin acupoints using a non-invasive device in humans [

241], while Tang et al. conducted real-time monitoring of NO release from acupoints

in vivo and observed L-arginine-dependent local NO generation [

242].

Collectively, these studies suggest that NO levels at acupoints are significantly higher than those in brain regions and blood vessels. It is intriguing to hypothesize that NO may represent the physiological basis of

qi (or “

ki” in Japanese pronunciation), generated at acupoints in response to external stimuli, including mechanical and thermal stress. Although further validation is required, the application of recent technologies, such as acupuncture needles equipped with NO microsensors [

243], may elucidate the dynamic NO response at acupoints, offering the first solid evidence to bridge modern science with traditional medicine and the philosophy of balance.

13.4. Stimulation to a Minimum Machiery

From a biophysical perspective, acupuncture, acupressure, and moxibustion exert mechanical and thermal stresses on tissues, potentially activating NMDARs and TRP channels to transmit Ca2+ signals that elicit whole-body responses. Recent advancement in lipid structural analysis has evaluated that compartmentalization of such signal tranduction systems is associated with the formation of special lipid domains.

The plasma membrane in eukaryotic cells contains microdomains enriched with sterols (such as cholesterol), forming membrane/lipid rafts (MLR) [

244,

245,

246,

247]. These regions may exist as caveolae, which appear morphologically as flask-like invaginations, or in a less observable planar form [

248,

249,

250]. MLR includes O

2•- generators such as NAD(P)H oxidase (Nox) in animals [

251] and respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs) in plants [

252], as well as NO generators such as eNOS [

251,

253,

254]. Additionally, signaling receptor [

255] and ion channels [

256]—including NMDARs [

257] and TRP channels [

258]—within MLR facilitate the communication of extracellular stimuli to the intracellular milieu [

248,

259]. One may hypothesize that cell membranes at acupoints are particularly rich in lipid rafts or lipid nano-environment [

260]—specialized membrane microdomains that serve as a "toolkit" for signal transduction [

152]. The dynamic response of these microdomains to mechanical and thermal stimuli may provide a compelling explanation for the physiological effects observed in acupuncture therapy.

14. Future Perspectives

14.1. O2–NO–H2S (ONS) Dynamics

Figure 10 presents a conceptual O

2–NO–H

2S (ONS) balance meter, inspired by the Mitsudome symbol (

Figure 9c), illustrating how living organisms on Earth have adapted to varying proportions of O

2, NO, and H

2S (ONS). This ONS gradient is observed across diverse natural environments, ranging from the surface to deeper layers of the atmosphere, soils, and oceans.