1. Introduction

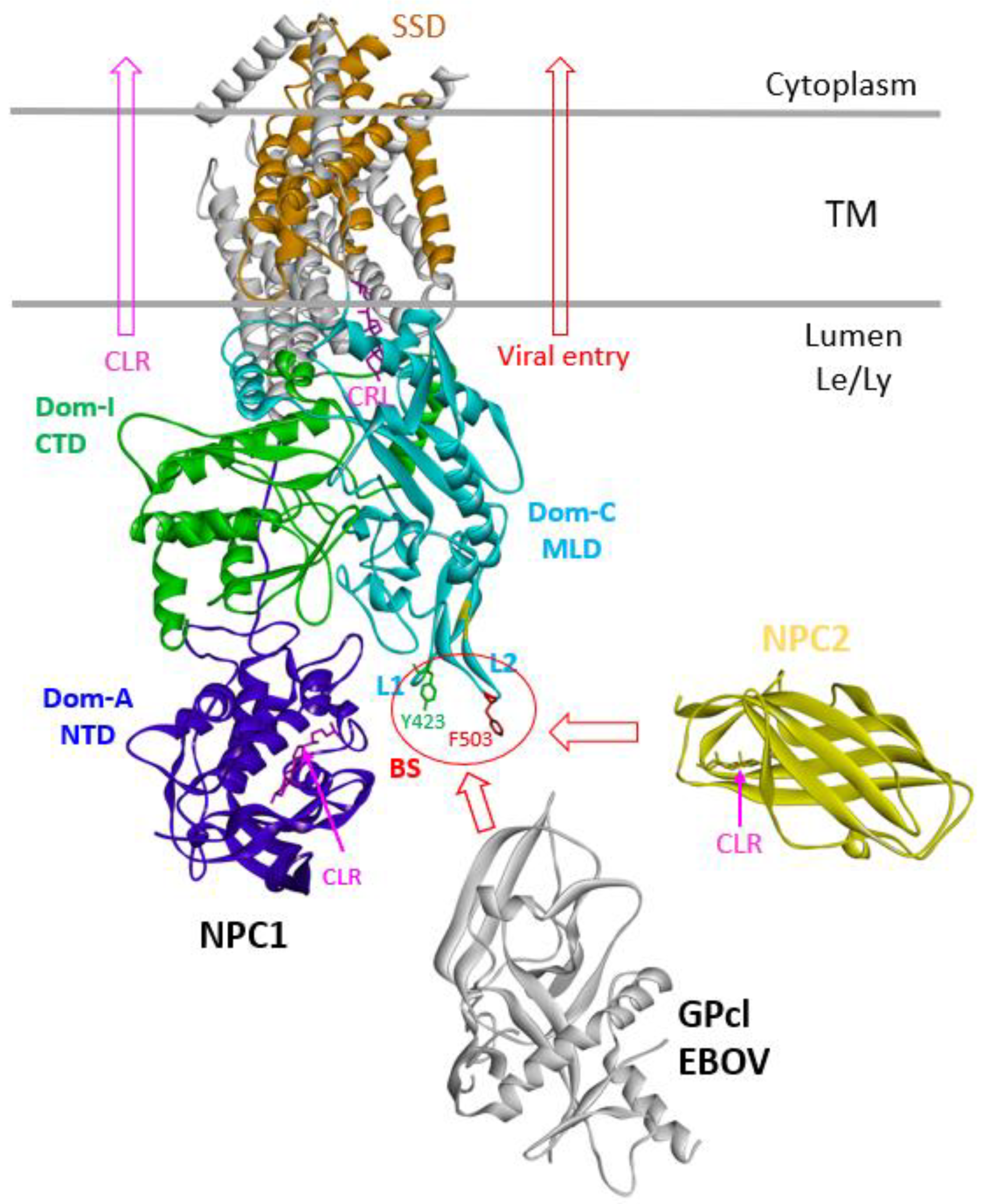

The human intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 and 2 (NPC1 and NPC2) proteins are responsible for cholesterol trafficking from late endosomes/lysosomes (Le/Ly) in the lumen to the cytoplasm[

1]. They have been named NPC1 and NPC2, respectively since they are involved in the serious cholesterol-derived diseases called Niemann-Pick type C (NPC) diseases. NPC1 is a large multi-transmembrane protein (~1278 residues) that contains 13 transmembrane helices (TM) and three luminal domains: A (N-terminal domain, NTD), C (middle luminal domain, MLD, 372-622, 250 residues) and I (C-terminal domain, CTD)[

2,

3]. NPC1 locates in the membranes of late endosomes and lysosomes and mediates intracellular cholesterol trafficking [

2]. NPC2 is a small soluble protein (~15 kd, 132 residues) in the late endosomes and lysosomes for transporting cholesterol molecules to NPC1[

4]. Then, the cholesterol can be further transported to the cytoplasm by NPC1 through the sterol-sensing domain(SSD)[

5]. Thus, NPC1 and NPC2 work together for transporting cholesterol from late endosomes and lysosomes to the cytoplasm[

5,

6]. The mutations from NPC1 or NPC2 genes will affect cholesterol trafficking and result in an accumulation of cholesterol in the Le/Ly that will cause serious NPC diseases.

Unfortunately, NPC1 is hijacked by deadly filoviruses such as Ebola virus (EBOV) or Marburg virus (MARV) and used as their receptors for infection of human cells [

7,

8]. EBOV and MARV are well-known members of the family

Filoviridae and have caused severe diseases called Ebola virus disease (EVD) [

9] and Marburg virus disease (MVD) [

10] with high mortality rates from 25% to 90% [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Although filovirus was first identified in the 1960s, but there are no effective drugs for treating the infections. Until 2020, two monoclonal antibody-based drugs for EBOV were approved for clinical use: one is a cocktail of three antibodies (REGN-EB3 or Inmazeb) and another is a single monoclonal antibody (mAb114 or Ebanga), which target the Ebola virus glycoprotein to block viral attachment and entry [

13,

15,

16]. It is required to develop more therapeutics for combating these deadly viral diseases.

Filoviruses are enveloped viruses with a single-stranded negative-sense RNA molecule genome and infect cells through macropinocytosis in the late endosomes or lysosomes[

17,

18,

19]. The glycoprotein (GP) is the sole viral protein on the surface of the virion which is essential for viral entry. The GP is initially synthesized as a single polypeptide (~676 residues), later cleaved by the cellular furin protease into disulfide-linked two subunits of GP1 and GP2. GP1 is exposed on the surface of the virion and GP2 is in the membrane containing the fusion loop. The glycoprotein spike is a trimer and consists of three GP molecules. While the virus through macropinocytosis and trafficking to the late endosomes and lysosomes, GP1 is further cleaved by endosomal cysteine proteases (cathepsins B&L) to remove the glycan cap and glycosylated mucin domain to expose the receptor binding site (RBS). The cleaved GP (GPcl, ~19kd) includes GP1 and GP2 portions to form a stable receptor binding domain (RBD) for interacting with receptor NPC1 Domain_C [

3,

20]. The GPcl binding to the cellular receptor NPC1_C will cause GP2 conformational change for membrane fusion of viral entry. Actually, the viral GPcl binding site on NPC1 for viral entry overlaps with NPC2 for cholesterol transporting, which is principally located in the loop 1 (L1) and loop 2 (L2) of NPC1_C domain [

3,

5,

21]. Therefore, It is evident that NPC2 compete with filovirus binding to NPC1 which will interfere with filovirus entry and block filovirus infection. Although these two cholesterol transporters were reported to be used as conjugates with antibodies for antiviral research[

22,

23], there are no reports investigating their activities directly against filovirus infection. This study has demonstrated that both cholesterol transporters (NPC1 and NPC2) can inhibit filovirus infection which are promising candidates for therapeutics development.

2. Results

2.1. Cholesterol Transporter 1 (NPC1) Inhibits Filovirus Infection

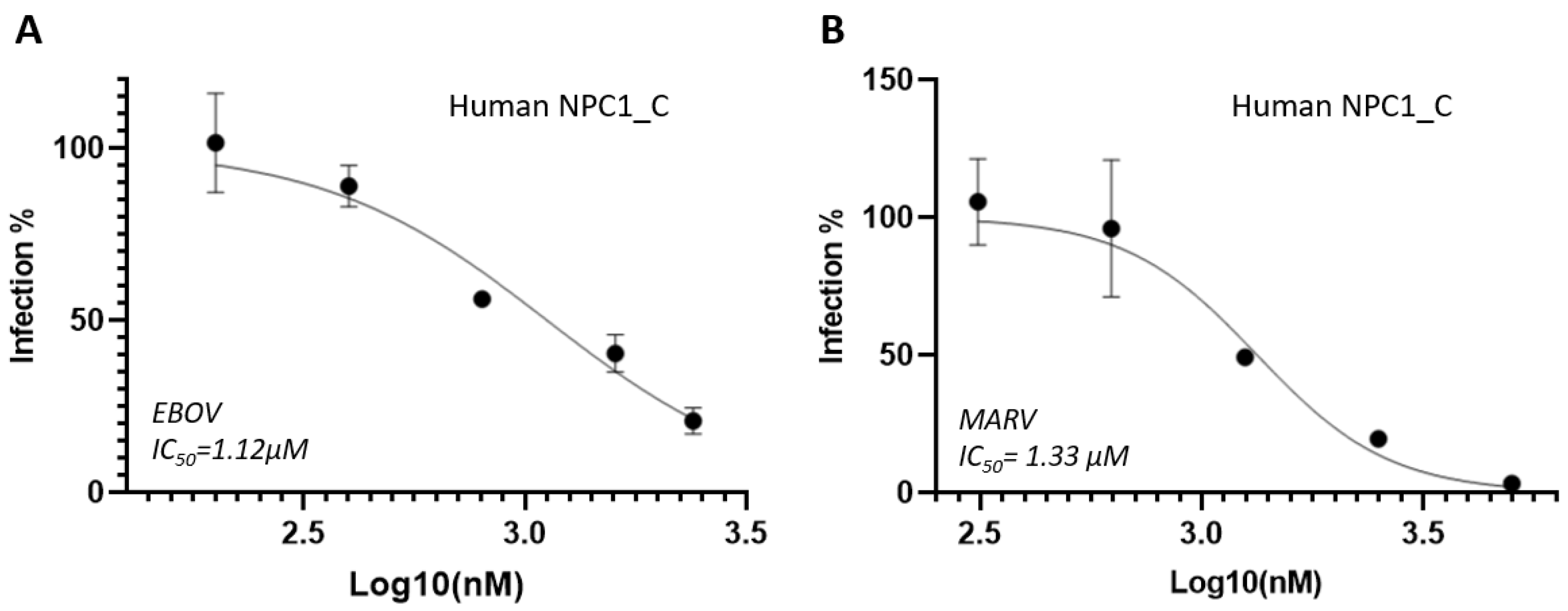

The Domain C of NPC1 is a middle luminal domain (MLD) which direct interact with viral GPcl for viral entry. Thus, NPC1_C domain (or called soluble NPC1) can be used as fake receptors to absorb viral particles for reducing infection because binding to the soluble NPC1 cannot get entry into the cells. In our tests, the soluble NPC1 significantly reduced EBOV and MARV infections, and the IC

50 values were 1.12 µM and 1.33 µM, respectively (

Figure 1). It is suggested that soluble NPC1 has the potential to be developed as a biological-based drug for filovirus infection.

2.2. Cholesterol Transporter 2 (NPC2) Inhibits Filovirus Infection

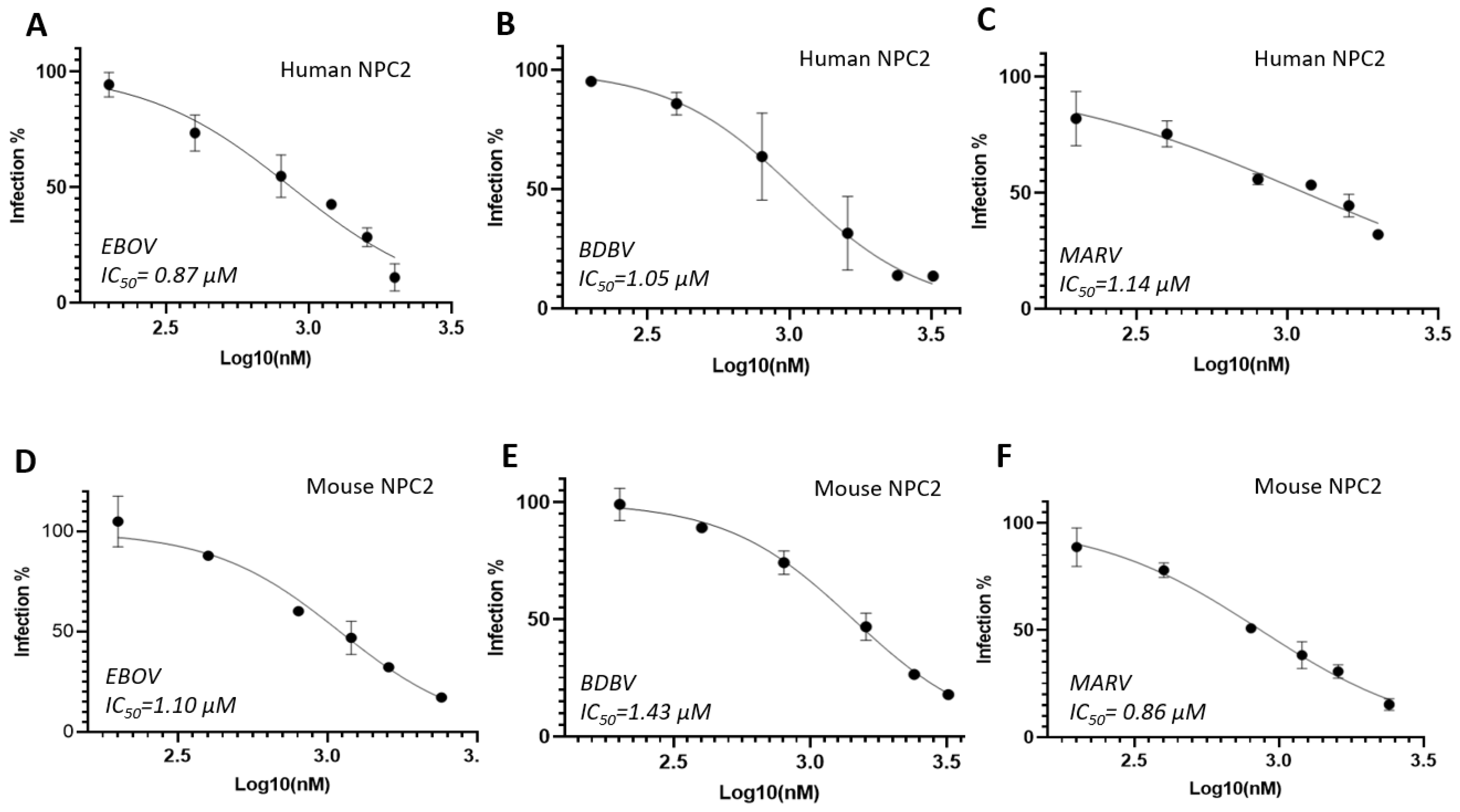

Cholesterol transporter 2 (NPC2) is a small soluble protein and responsible for transporting cholesterol molecules to Cholesterol transporter 1 (NPC1) and then to cytoplasm. Unfortunately, the binding site for NPC2 on NPC1 is overlapped with filovirus binding. In this case, NPC2 will compete with filovirus binding to NPC1 so that NPC2 binding can block filovirud entry. We then tested this hypothesis by using soluble NPC2 protein and the result turned out to be positive and the inhibition of EBOV is potent with IC

50 value of 0.87 µM. Another Ebola virus strain BDBV (Bundibugyo ebolavirus) was also tested with the IC

50 value is 1.05 µM which is similar to EBOV (

Figure 2A and 2B). Interestingly, we also tested mouse NPC2 which did show similar the inhibition with the IC

50 values of 1.10 µM and 1.43 µM for EBOV and BDBV, respecgtively (

Figure 2D and 2E). We tested NPC2 agasint MARV, both human and mouse NPC2 exhibited good activities with IC

50 values of 1.14 µM and 0.86 µM, respectivily (

Figure 2C and 2F). Comparing the sequences of human NPC2 and mouse NPC2, the identity is 80.1% (

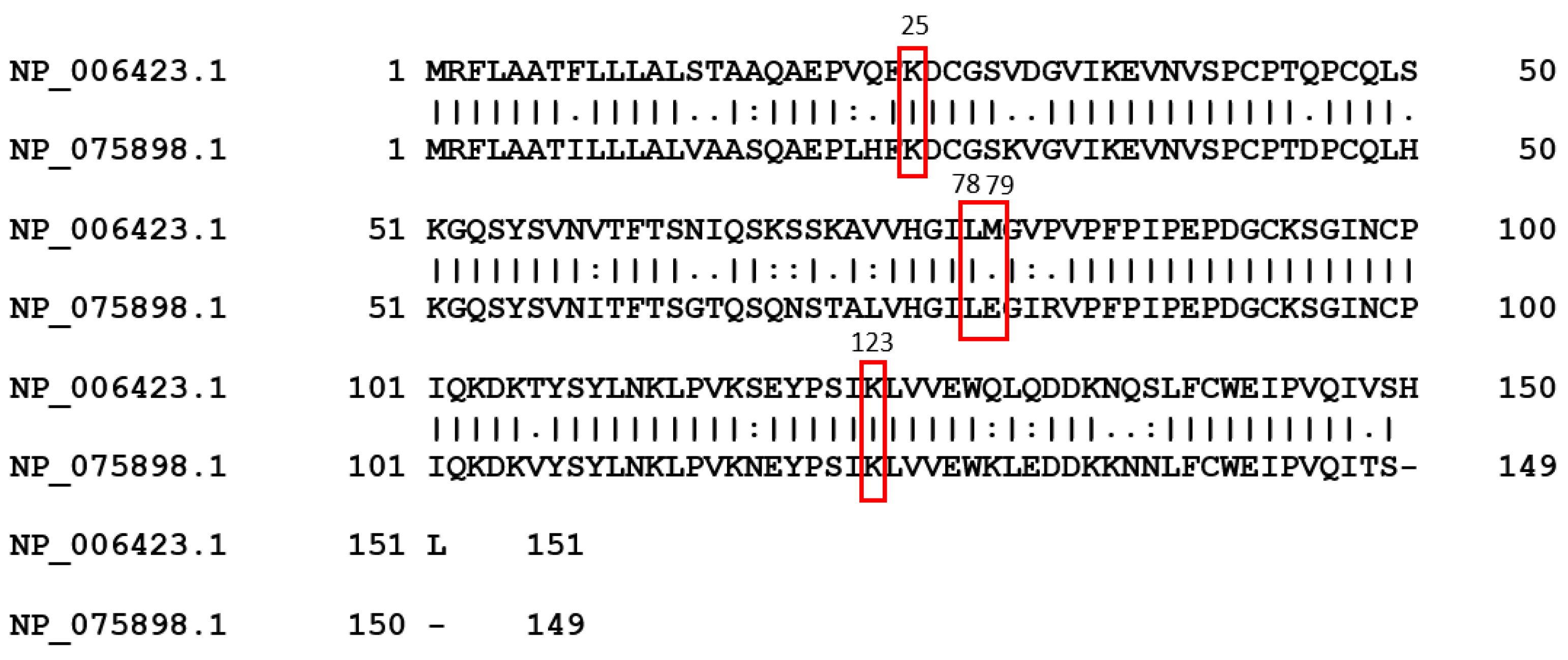

Figure 3). The results appear to be that human NPC2 is better than mouse NPC2 against EBOV, but surprisingly mouse NPC2 is better that human NPC2 against MARV. The sequence difference and especially some key residues such as residue 79 (Methionine for human , but Aspatic acid for mouse) interacting with NPC1 binding may have played a role in this inhibition difference (

Figure 3.) .

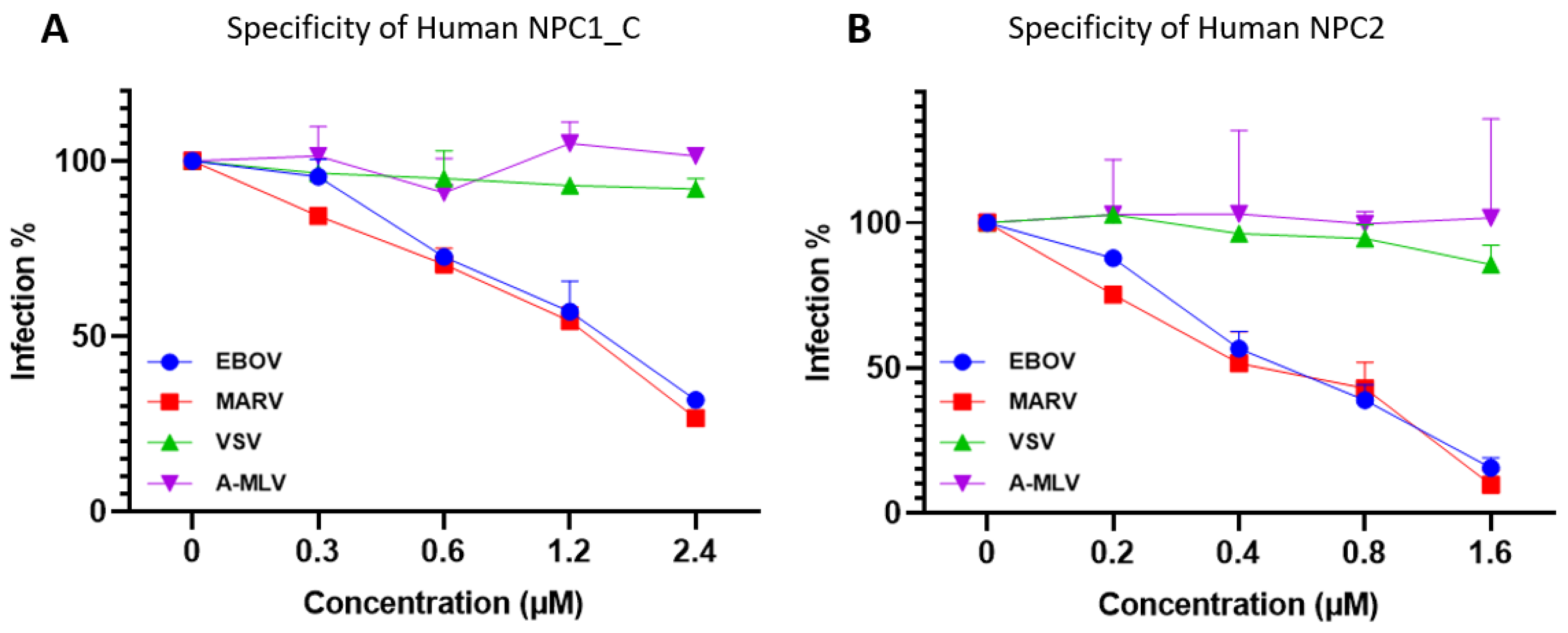

2.3. Specificity of the NPC1 and NPC2 Inhibition

To examine whether NPC1 and NPC2 are specific in the inhibitions of filoviruses infections, we have tested other viruses pseudotyped in the same manner such as Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) which is a well-known an enveloped, negative-sense RNA virus and able to infect a wide range of mammalian cells and Amphotropic-murine leukemia virus (A-MLV) which is a retrovirus. The data clearly showed that there were no activities against the pseudotyped VSV virus but having the activities against EBOV and MARV from the side-by-side assays (

Figure 4). It is suggested that these NPC1 and NPC2 as inhibitors are specific for the filoviruses EBOV and MARV.

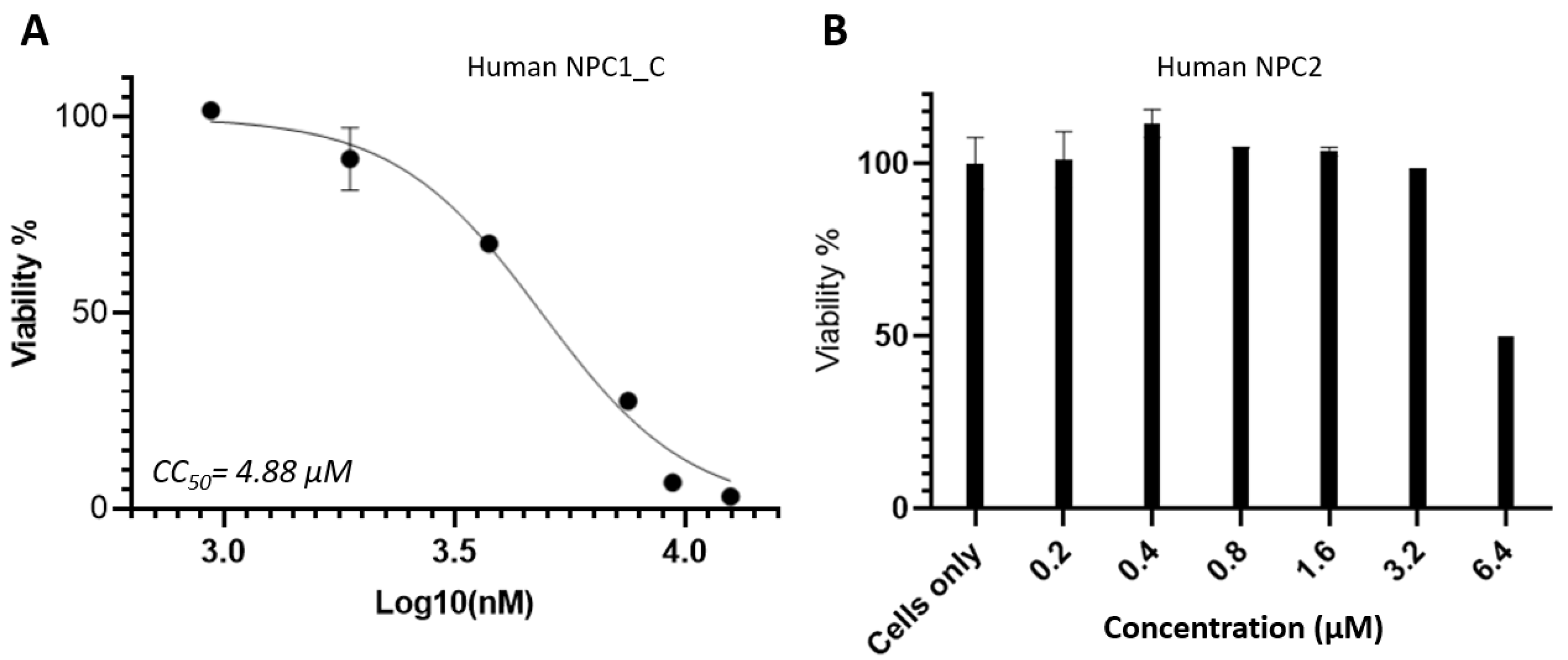

2.4. Cytotoxicity Analysis of NPC1 and NPC2

Cytotoxicity of NPC1_C domain and soluble NPC2 protein were evaluated using MTT based cell viability assay. TZM-bl cells which were used for the inhibition assay were used for cytotoxicity test. The CC

50 value (cytotoxic concentration 50%) for NPC1_C protein is 4.88 µM which is shown in

Figure 5A. For NPC2 protein, the data were shown in a bar graph in

Figure 5B, and the CC

50 was estimated at ~ 6.4 µM. The Selectivity index (

SI) values are around 5, which is not high. It is suggested that NPC1_C and NPC2 proteins have some cytotoxicity if the concentration goes higher.

3. Discussion

It is fascinating to find out that filovirus hijacked the cholesterol trafficking pathway of NPC1/NPC2 for entry, but we can use the pathway proteins to counteract filovirus entry. Unexpectedly, the inhibition potencies (IC

50s) look very similar between these two protein inhibitors even though the inhibiting mechanisms are quite different. As mentioned previously, NPC1_C domain is used as a fake soluble receptor for capturing viral particles, but NPC2 is competing with viral-GP binding to NPC1 for viral entry. However, all their interactions are based on their binding on a molecular basis. Further analysis of the interactions between NPC1_C and NPC2 or GPcl, the binding sites are similar and involved in the two loops (L1 and L2) of NPC1_C. The Y423 in L1 and F503 in L2 are the two key residues for NPC2 and GPcl binding, according to their binding structures (PDB 6W5V and 5JNX) (

Figure 6).

Soluble NPC1 (or NPC1_C domain) inhibition of filovirus is just like soluble CD4 inhibition of HIV, which uses their binding affinity for capturing viral particles to prevent infection. Unfortunately, soluble CD4 cannot be successfully developed as the drug for inhibiting HIV infection because soluble CD4 can also enhance HIV infection for low CD4 expression cells or CD4-negative cells

in vivo. The reason is that soluble CD4 could induce trans HIV infection since soluble CD4 binding to gp120 create the form for coreceptor CCR5/CXCR4 binding for viral entry[

24]. However, soluble NPC1 binding does not have this issue in filovirus entry, and it will block the infection indefinitely. Therefore, soluble NPC1 has advantages for drug development against filovirus infection.

NPC2 as a native soluble protein in the Le/Ly should have more advantages for therapeutic use against filovirus infection. NPC2 and NPC1_C domain were used as conjugates with bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) for filovirus inhibition by which the inhibition functions were thought of from antibodies [

22,

23]. In their finding, it was suggested that NPC2 role is through mediating the Le/Ly delivery but not direct interaction with NPC1 [

23]. However, from our studies, NPC2 protein was used alone as the inhibitors without antibody so that the data demonstrated its inhibition is through the binding to achieve excellent inhibition with the IC

50 values are around 1 µM, even using mouse NPC2. Interestingly, although mouse is not accessible to filovirus infection, mouse NPC2 can inhibit filovirus infection. It is implicated that mouse NPC2 is similar to human NPC2 which can bind to human NPC1.

It is not known whether filovirus infection has affected cholesterol trafficking. In theory, filovirus entry hijacks NPC1/NPC2 cholesterol trafficking pathway that will affect cholesterol transportation from Le/Ly to the cytoplasm. In fact, there are other pathways for cholesterol transportation, such as NPC1L1 [

25,

26], which has the sterol-sensing domain (SSD) and may have a role for compensating the loss from NPC1 pathway[

27]. The NPC1L1 pathway has not been well studied, and we do not know whether it needs NPC2-liked partner for transferring cholesterol, but one thing seems sure is that filovirus GP cannot bind to NPC1L1 for viral entry.

It is promising that developing soluble NPC1 (Domain-C) and NPC2 protein-based therapeutics for treating filovirus infections. Because they are small soluble proteins from the human body and exist in the Le/Ly so that they should have overcome the most clinical safety concerns. Another advantage for these biological agents is that their specificities for targeting which should have less side effects. Like the antibody-drugs, NPC1 or NPC2 protein-based drugs will be injectable for treating filovirus infected patients. Finally, we would like to point out here that although our neutralization results are from pseudotyped filoviruses, they would be comparable to infectious viruses, because our pseudotyped virus platforms have been well documented previously for testing entry inhibitors [

28,

29].

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that the intracellular cholesterol transporters NPC1 (Domain C) and NPC2 proteins have strong activities to inhibit filovirus infection. It is feasible to be developed as biological therapeutics for treating filovirus infection.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Proteins, Plasmids, Strains, and Cells

The protein samples of human NPC1 (catalog no. 16499-H32H), human NPC2 (catalog no. 13341-H08H and mouse NPC2 (catalog no. 2313-M08H) were purchased from Sino Biological US Inc (Chesterbrook, PA). The viral envelope glycoprotein genes used for pseudotyped viruses were as follows: EBOV (Zaire ebolavirus, GenBank accession no. AIO11753.1), BDBV (Bundibugyo ebolavirus, GenBank accession no. ACI28624) and MARV (Marburg marburgvirus Uganda 02Uga07, GenBank accession no. ACT79201.1). The VSV-G plasmid of Vesicular stomatitis virus and A-MLV envelope plasmid of Amphotropic murine leukemia virus, and HIV-1 plasmid pSG3ΔEnv, and the TZM-bl cells were obtained from NIH AIDS Reagent Program.

4.2. Pseudotyping Viruses

HIV-1 backbone plasmid pSG3ΔEnv was used for making pseudotyped viruses. The glycoprotein genes (GPs) of Ebola and Marburg viruses were synthesized and cloned into the pCDNA3.1+ expression vector. Both plasmids of pSG3ΔEnv and the GP envelope were co-transfected into 293T cells in a 10-cm plate using transfection reagent polyethyleneimine (PEI). The plates were cultured in a tissue incubator at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2 for two days, then the medium was harvested and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min to remove cell debris. The supernatants containing the pseudotyped were made aliquots and stored at -80℃.

4.3. Inhibition Assay Against Pseudotyped Filoviruses

Inhibition assay was performed in a 96-well plate using pseudotyped viruses and TZM-bl cells (6000/well) as this cell-line has a Luciferase report gene under the inducible promoter of Tat protein factor. The mixtures of viruses and protein samples were transferred onto the target cell wells for infection. One-day post infection, the media were removed, the cells were washed once with PBS and incubated in fresh media for one more day. Then the cells were lysed in 1X Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) and kept at room temperature for 20 minutes. The luciferase activity was measured using luciferin substrate (Promega) in a Veritas Luminometer. All the samples assessed in triplicates and the neutralization activities were calculated in comparison with controls of positive (virus only) and negative (cells only).

4.5. Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. The TZM-bl cells (3000/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h at 37 ℃. Media was removed and replaced with 100 μl of protein solution in triplicates for two days and then replace the protein solution with 100 μl complete DMEM for continuingly culturing for one more day. The cultured media were removed, and the cells were washed once with PBS for analysis. A 50 μl solution of 5 mg/ml MTT [3-4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 3 h at 37 ℃, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm and with 690 nm (background) wavelength.

4.6. Data Statistical Analysis

Graphpad Prism software was used for all statistical analyses for making the neutralization and cytotoxicity figures and determining average values, standard errors, values of IC50 or CC50.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SHX; methodology, LLW and SHX; formal analysis, LLW; investigation, LLW and SHX; writing—original draft preparation, SHX and LLW; writing—review and editing, SHX and LLW.; supervision, SHX; funding acquisition, SHX. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the NIH AIDS Reagent Program for providing vector plasmids and TZM-bl cells for pseudotyped filovirus assay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EBOV |

Zaire ebolavirus |

| BDBV |

Bundibugyo ebolavirus |

| MARV |

Marburg marburgvirus |

| NPC1 |

Niemann-Pick disease, type C1 |

| NPC2 |

Niemann-Pick disease, type C2 |

| M:LD |

Middle luminal domain, also called domain C |

| CLR |

Cholesterol |

| Le/Ly |

Late endosomes/Lysosomes |

| MTT |

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

References

- Deffieu, M.S.; Pfeffer, S.R. Niemann-Pick type C 1 function requires lumenal domain residues that mediate cholesterol-dependent NPC2 binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 18932–18936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Qian, H.; Zhou, X.; Wu, J.; Wan, T.; Cao, P.; Huang, W.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; et al. Structural Insights into the Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1)-Mediated Cholesterol Transfer and Ebola Infection. Cell 2016, 165, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Song, J.; Qi, J.; Lu, G.; Yan, J.; Gao, G.F. Ebola Viral Glycoprotein Bound to Its Endosomal Receptor Niemann-Pick C1. Cell 2016, 164, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanier, M.T.; Millat, G. Structure and function of the NPC2 protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004, 1685, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Wu, X.; Du, X.; Yao, X.; Zhao, X.; Lee, J.; Yang, H.; Yan, N. Structural Basis of Low-pH-Dependent Lysosomal Cholesterol Egress by NPC1 and NPC2. Cell 2020, 182, 98–111 e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Saha, P.; Li, J.; Blobel, G.; Pfeffer, S.R. Clues to the mechanism of cholesterol transfer from the structure of NPC1 middle lumenal domain bound to NPC2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 10079–10084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carette, J.E.; Raaben, M.; Wong, A.C.; Herbert, A.S.; Obernosterer, G.; Mulherkar, N.; Kuehne, A.I.; Kranzusch, P.J.; Griffin, A.M.; Ruthel, G.; et al. Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1. Nature 2011, 477, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, M.; Misasi, J.; Ren, T.; Bruchez, A.; Lee, K.; Filone, C.M.; Hensley, L.; Li, Q.; Ory, D.; Chandran, K.; Cunningham, J. Small molecule inhibitors reveal Niemann-Pick C1 is essential for Ebola virus infection. Nature 2011, 477, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.T.; Crozier, I.; Fischer, W.A.; 2nd Hewlett, A.; Kraft, C.S.; Vega, M.A.; Soka, M.J.; Wahl, V.; Griffiths, A.; Bollinger, L.; Kuhn, J.H. Ebola virus disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Salsabil, L.; Hossain, M.J.; Shahriar, M.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Islam, M.R. The recent outbreaks of Marburg virus disease in African countries are indicating potential threat to the global public health: Future prediction from historical data. Health Sci Rep 2023, 6, e1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohimain, E.I.; Chakraborty, C. Editorial overview: An initiative toward Ebolavirus disease (EVD) free world: An edited special anti-infective issue on Ebola virus disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2022, 62, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Dhasmana, A.; Bora, J.; Uniyal, P.; Slama, P.; Preetam, S.; Chopra, H.; Islam, M.A.; Dhama, K. Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak re-emergence regulation in East Africa: preparedness and vaccination perspective. Int J Surg 2023, 109, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. https://www.who.int/health-topics/ebola/.

- Feldmann, H.; Sprecher, A.; Geisbert, T.W. Ebola. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1832–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.M. Monoclonal Antibody Therapy for Ebola Virus Disease. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 2365–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, N.J.; Sanchez, A.; Rollin, P.E.; Yang, Z.Y.; Nabel, G.J. Development of a preventive vaccine for Ebola virus infection in primates. Nature 2000, 408, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G. Filovirus entry. Adv Exp Med Biol 2013, 790, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Davey, R.A.; Shtanko, O.; Anantpadma, M.; Sakurai, Y.; Chandran, K.; Maury, W. Mechanisms of Filovirus Entry. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2017, 411, 323–352. [Google Scholar]

- Salata, C.; Calistri, A.; Alvisi, G.; Celestino, M.; Parolin, C.; Palu, G. Ebola Virus Entry: From Molecular Characterization to Drug Discovery. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.H.; Obernosterer, G.; Raaben, M.; Herbert, A.S.; Deffieu, M.S.; Krishnan, A.; Ndungo, E.; Sandesara, R.G.; Carette, J.E.; Kuehne, A.I.; et al. Ebola virus entry requires the host-programmed recognition of an intracellular receptor. EMBO J 2012, 31, 1947–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cohen, A.A.; Galimidi, R.P.; Gristick, H.B.; Jensen, G.J.; Bjorkman, P.J. Cryo-EM structure of a CD4-bound open HIV-1 envelope trimer reveals structural rearrangements of the gp120 V1V2 loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E7151–E7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wec, A.Z.; Nyakatura, E.K.; Herbert, A.S.; Howell, K.A.; Holtsberg, F.W.; Bakken, R.R.; Mittler, E.; Christin, J.R.; Shulenin, S.; Jangra, R.K.; et al. A „Trojan horse” bispecific-antibody strategy for broad protection against ebolaviruses. Science 2016, 354, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirchnianski, A.S.; Wec, A.Z.; Nyakatura, E.K.; Herbert, A.S.; Slough, M.M.; Kuehne, A.I.; Mittler, E.; Jangra, R.K.; Teruya, J.; Dye, J.M.; et al. Two Distinct Lysosomal Targeting Strategies Afford Trojan Horse Antibodies With Pan-Filovirus Activity. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 729851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haim, H.; Si, Z.; Madani, N.; Wang, L.; Courter, J.R.; Princiotto, A.; Kassa, A.; DeGrace, M.; McGee-Estrada, K.; Mefford, M.; et al. Soluble CD4 and CD4-mimetic compounds inhibit HIV-1 infection by induction of a short-lived activated state. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5, e1000360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.S.; Yu, X.; Fordstrom, P.; Choi, K.; Chung, B.C.; Roh, S.H.; Chiu, W.; Zhou, M.; Min, X.; Wang, Z. Cryo-EM structures of NPC1L1 reveal mechanisms of cholesterol transport and ezetimibe inhibition. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eabb1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yang, F.; Huang, Y.; You, X.; Liu, D.; Sun, S.; Sui, S.F. Structural insights into the mechanism of human NPC1L1-mediated cholesterol uptake. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Yan, R.; Cao, P.; Qian, H.; Yan, N. Structural advances in sterol-sensing domain-containing proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 2022, 47, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Alfson, K.; Eaton, B.; Mattix, M.E.; Goez-Gazi, Y.; Holbrook, M.R.; Carrion, R.; Jr Xiang, S.H. Algal Lectin Griffithsin Inhibits Ebola Virus Infection. Molecules 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Palermo, N.; Estrada, L.; Thompson, C.; Patten, J.J.; Anantpadma, M.; Davey, R.A.; Xiang, S.H. Identification of filovirus entry inhibitors targeting the endosomal receptor NPC1 binding site. Antiviral Res 2021, 189, 105059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).