Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Environment

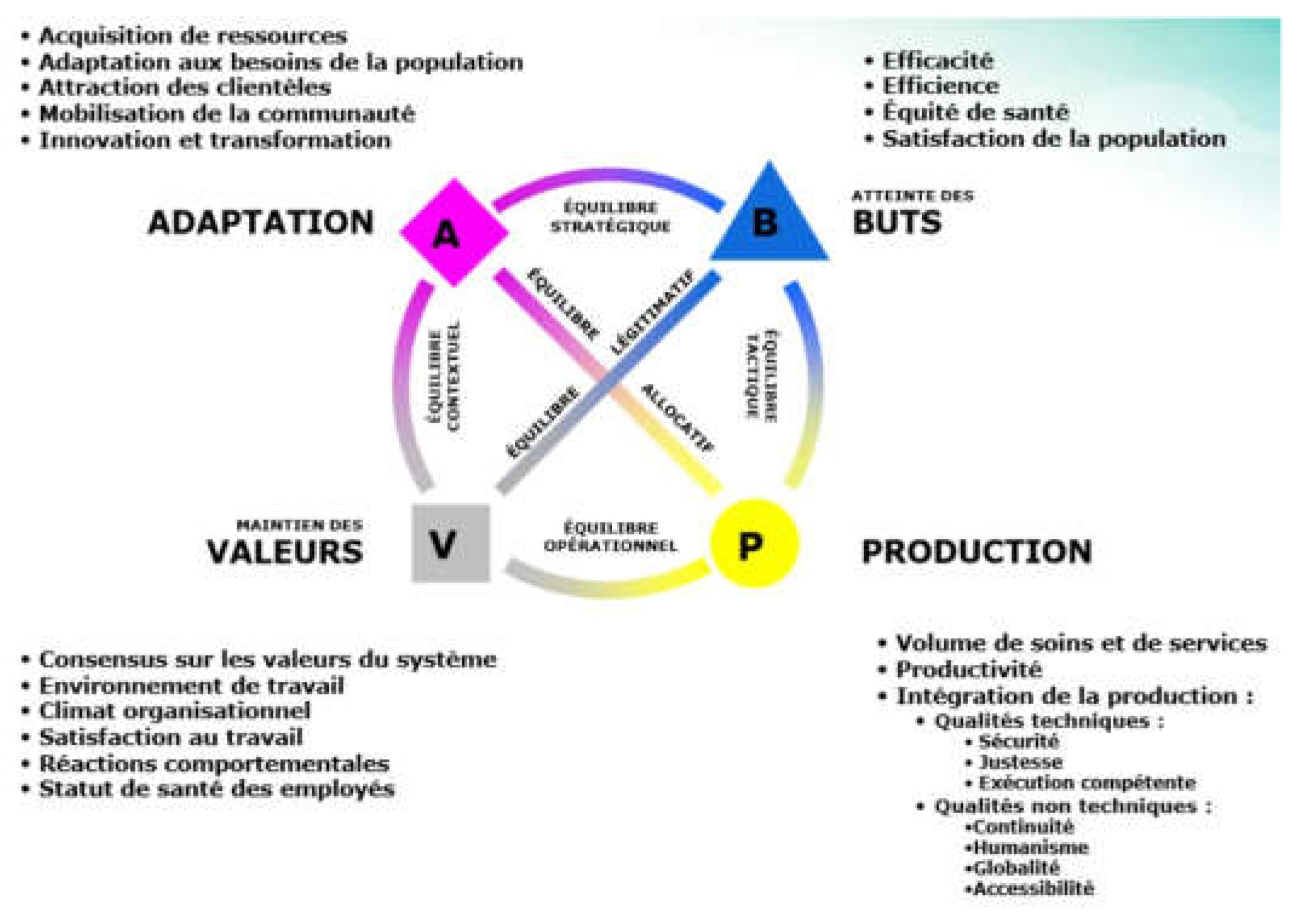

2.2. Operational Framework of the ÉGIPSS Model, Its Components and Their Relationship with the Hospital

2.3. Selection Criteria for Hospital Structures under Study

2.4. Type of Study

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

| Performance Level | Satisfying | Acceptable | Worrying | |||||||

| STRUCTURES | PGRHB | GRH CIRIRI | CLIN OUB | GRH KADUTU | HC NYAMUGO | POLY.RED CROSS | POLY BERNA | HC ISTM | HC SAINT VINCENT | MC FOND MAROY |

| ADAPTATION | 78 | 61 | 59 | 53 | 47 | 42 | 41 | 40 | 40 | 36 |

| Resource acquisition (%) | 60 | 43 | 45 | 32 | 28 | 27 | 30 | 28 | 22 | 18 |

| Local community support (%) | 78 | 66 | 68 | 56 | 48 | 42 | 36 | 40 | 46 | 40 |

| Consistency with social values (%) | 85 | 67 | 68 | 67 | 65 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 58 | 48 |

| Response to population needs (%) | 78 | 50 | 58 | 46 | 50 | 28 | 38 | 26 | 24 | 26 |

| Market presence (%) | 88 | 75 | 35 | 55 | 48 | 55 | 38 | 45 | 48 | 48 |

| Innovation and learning (%) | 80 | 64 | 82 | 62 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 34 |

| ACHIEVEMENT OF OBJECTIVES | 78 | 69 | 65 | 64 | 63 | 60 | 60 | 59 | 60 | 56 |

| Patient satisfaction (%) | 82 | 80 | 72 | 72 | 68 | 70 | 76 | 62 | 66 | 62 |

| Efficiency (%) | 74 | 68 | 58 | 66 | 60 | 62 | 56 | 70 | 60 | 52 |

| Efficiency (%) | 78 | 60 | 65 | 55 | 60 | 48 | 48 | 45 | 53 | 55 |

| PRODUCTION | 85 | 75 | 73 | 66 | 57 | 55 | 55 | 54 | 53 | 48 |

| Activity volume (%) | 86 | 76 | 70 | 76 | 54 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 50 | 42 |

| Quality (%) | 83 | 78 | 80 | 68 | 60 | 65 | 64 | 67 | 62 | 50 |

| Production coordination (%) | 86 | 72 | 70 | 54 | 58 | 54 | 54 | 48 | 48 | 52 |

| CULTURE/VALUES | 85 | 82 | 71 | 67 | 62 | 61 | 57 | 55 | 54 | 53 |

| Organizational values (%) | 86 | 82 | 76 | 74 | 64 | 60 | 62 | 62 | 56 | 56 |

| Organizational climate (%) | 84 | 82 | 66 | 60 | 60 | 62 | 52 | 48 | 52 | 50 |

| OVERALL AVERAGE | 82 | 72 | 67 | 63 | 57 | 55 | 53 | 52 | 52 | 48 |

3.1. Adaptation

3.2. Achieving Goals

3.3. Production

3.4. Culture / Values

4. Discussion

4.1. Combining Clinical Care with Research and Teaching Improves Hospital Performance

4.2. Adaptability Significantly Influences Other Dimensions of the EGIPSS Model and Along the Way the Overall Performance of the Hospital

4.3. To Adapt, Hospitals Need Resources and Good Management and Governance

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saulnier, D.D., et al., Re-evaluating our knowledge of health system resilience during COVID-19: lessons from the first two years of the pandemic. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 2023. 12. [CrossRef]

- Karemere Bimana, H., Gouvernance hospitalière adaptative en contexte changeant: étude des hôpitaux de Bunia, Logo et Katana en République démocratique du Congo. 2013, UCL-Université Catholique de Louvain.

- Karemere, H., et al., Gouvernance des hôpitaux de référence en République démocratique du Congo: synthèse critique interprétative de la littérature. Médecine et Santé Tropicales, 2013. 23(4): p. 397-402.

- Alvarez, F. Le contrôle de gestion en milieu hospitalier: une réponse à l'émergence de risques organisationnels. in XXIème congrès de l'Association Française de Comptabilité. 2000.

- Guisset, A.-L., et al., Définition de la performance hospitalière: une enquête auprès des divers acteurs stratégiques au sein des hôpitaux. Sciences sociales et santé, 2002. 20(2): p. 65-104.

- BERRADA, H. and A. MARGHICH, PERFORMANCE HOSPITALIERE: ETAT DE L’ART. Revue du contrôle, de la comptabilité et de l’audit, 2023. 7(1).

- Kaplan, R.S. and D.P. Norton, The balanced scorecard: measures that drive performance. Vol. 70. 2005: Harvard business review Boston, MA.

- Kruk, M.E. and L.P. Freedman, Assessing health system performance in developing countries: a review of the literature. Health policy, 2008. 85(3): p. 263-276. [CrossRef]

- LAHBIB, A. and A. SAID, La performance hospitalière: approches et modèles de définitions. Revue Internationale du Chercheur, 2022. 3(4).

- DIAKITE, O., et al., Proposition d’un modèle explicatif de la performance organisationnelle par les facteurs individuels dans les Centres Hospitaliers Universitaires du Mali. Revue Internationale des Sciences de Gestion, 2022. 5(1).

- Sicotte, C., et al., A conceptual framework for the analysis of health care organizations' performance. Health services management research, 1998. 11(1): p. 24-41. [CrossRef]

- Papanicolas, I., et al., Health system performance assessment: a framework for policy analysis. 2022.

- Contandriopoulos, A.-P., La gouvernance dans le domaine de la santé: une régulation orientée par la performance. Santé publique, 2008. 20(2): p. 191-199.

- Karemere, H., et al., Analysis of hospital performance from the point of view of sanitary standards: study of Bagira General Referral Hospital in DR Congo. Journal of Hospital Management and Health Policy, 2020. 4. [CrossRef]

- Sivyavugha, S.K., et al., Proliferation of hospital facilities in the Ibanda Health Zone in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Determinants and perceptions of health stakeholders. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 2024. 43(1): p. 28-38.

- Batumike, I., et al., Analysis of hospital care provision in the urban health zones of Bukavu, DR Congo. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 2024. 43(1): p. 70-81.

- HZ-Kadutu, Rapport annuel 2021. Ministère de la santé de la RD Congo, 2021.

- JANDARME, F. and P. BALUNGU, Vécu psychosocial au sein des familles victimes du confinement dû à la Covid-19 dans la ville de Bukavu, au Sud-Kivu en République Démocratique du Congo. Éducation et développement, 2020(24): p. 19-19.

- Kajiramugabi, F.M., et al., Impact de la COVID-19 sur les services de prévention du VIH et de prise en charge des personnes vivant avec le VIH dans la ville de Bukavu: une étude mixte séquentielle explicative. Science of Nursing and Health Practices, 2023. 6(2): p. 16-32. [CrossRef]

- Sciulli, D. and D. Gerstein, Social theory and Talcott Parsons in the 1980s. Annual Review of Sociology, 1985: p. 369-387. [CrossRef]

- Beaud, J.-P., L’échantillonnage. Recherche sociale: de la problématique à la collecte des données, 2009. 5: p. 169-198.

- De Roten, Y., Évaluation ou dévaluation? Quelques malentendus entre chercheurs et cliniciens sur la recherche empirique. Psychothérapies, 2021. 41(4): p. 209-217.

- Porro, B. and K. Lamore, Vers un décloisonnement de la recherche en psycho-oncologie: quid de la formation des jeunes chercheurs? 2022. [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.G.M., M.A. Musetti, and M.C.A. Mendonça, Multivariate analysis techniques applied for the performance measurement of Federal University Hospitals of Brazil. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 2018. 126: p. 16-29. [CrossRef]

- De Melo, G.A., et al., Performance measurement of Brazilian federal university hospitals: an overview of the public health care services through principal component analysis. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 2024. 38(3): p. 351-371.

- Li, H., et al., Tianjin Medical University General Hospital. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction, 2025. 18(6): p. 925—930. [CrossRef]

- Slama, L., et al., L'observance thérapeutique au cours de l'infection VIH, une approche multidisciplinaire. Médecine et maladies infectieuses, 2006. 36(1): p. 16-26.

- Levesque 1, J., et al., Barrières et éléments facilitant l’implantation de modèles intégrés de prévention et de gestion des maladies chroniques. Pratiques et organisation des soins, 2009(4): p. 251-265.

- Boeker, W. and J. Goodstein, Organizational performance and adaptation: Effects of environment and performance on changes in board composition. Academy of Management journal, 1991. 34(4): p. 805-826. [CrossRef]

- Tagne, A.G.F., et al., Appréciation de la performance hospitalière des hôpitaux publics au Cameroun: une perception du personnel de santé. Journal of Academic Finance, 2020. 11(2): p. 331-344.

- Kehili, H., et al., Le Dossier Électronique médical à l’EHUO: Une avancée cruciale pour les soins de santé. 2024.

- Collet, L., ParKourS 2024: intégration des innovations numériques dans le parcours de soins du patient et mise en place dans les établissements hospitaliers. Innovations & Thérapeutiques en Oncologie, 2024. 10(5): p. 342-344. [CrossRef]

- Dorier, E. and E. Morand, " Accessibilité aux services de soins en situation post conflit, République du Congo. Bulletin de l'Association de géographes français, 2012. 2012: p. pp 289-312.

- Tete, B., et al., Connaissances et attitudes des médecins sur le syndrome d’apnées-hypopnées obstructives du sommeil à Kinshasa-République Démocratique du Congo. Médecine du Sommeil, 2022. 19(3): p. 182-189.

- Mulinganya, V., et al., Temps d’attente prolongés aux services de consultation médicale: enjeux et perspectives pour des hôpitaux de Bukavu en République Démocratique du Congo. The Pan African Medical Journal, 2018. 29.

- Ghioua, K. and H.E. Tebbouche, Labellisation de la durabilité des équipements sanitaires en Algerie: Cas de l’hôpital Bachir Mentourie d’El-Milia-Jijel. 2020, Université de Jijel.

- De Witte, L. and L. Decaux, " Importance de la durabilité dans les hôpitaux belges à l'horizon 2030: comment améliorer la durabilité tout en maintenant la qualité des soins?

- Tchouaket, E., et al., An Analysis of the Social Impacts of a Health System Strengthening Program Based on Purchasing Health Services. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 2023. 13(4): p. 751-773. [CrossRef]

- Karemere, H., et al., Analyzing Katana referral hospital as a complex adaptive system: agents, interactions and adaptation to a changing environment. Conflict and health, 2015. 9: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Baganda, B.M., S.L. Makali, and H. Karemere, Analyse des coûts des soins de santé chez les enfants de moins de 5 ans dans la Zone de santé de Bagira et implications pour la couverture sanitaire universelle. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 2024. 43(1): p. 14-27.

- Dumez, H. and A. Jeunemaître, Combinaison harmonieuse des vertus du public et du privé, ou mélange des genres? Les partenariats public/privé, nouveaux venus du management public. Politiques et management public, 2003. 21(4): p. 1-14.

| No. | HA* | HA Population | Selected hospital structures |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BINAME | 32361 | |

| 2 | BUHOLO2 | 28197 | |

| 3 | CECA MWEZE | 29030 | |

| 4 | CIMPUNDA | 29904 | |

| 5 | CIRIRI 1 | 59628 | GRH CIRIRI |

| 6 | CIRIRI2 | 14786 | |

| 7 | UNEF | 23515 | GRH Kadutu |

| MC Red Cross | |||

| 8 | LURHUMA | 19068 | HC ISTM Bukavu |

| 9 | MARIA | 71543 | OUB Clinic |

| PGRHB | |||

| Maroy Foundation Medical Center | |||

| 10 | NEEMA | 20932 | HC Saint Vincent |

| 11 | NYAMUGO | 26059 | Nyamugo Hospital Center |

| 12 | NYAMULAGIRA | 22736 | Berna Polyclinic |

| 13 | UZIMA | 14537 | |

| TOTAL HZ | 392296 |

| Settings | Number of items | Data collection technique |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptation | ||

| Adaptation of resources | 6 | Documentary review, interviews, observation |

| Local Community Support | 5 | Interviews |

| Consistency with social values | 6 | Interviews |

| Responses to the needs of the population | 5 | Documentary review, interviews |

| Market presence | 4 | Documentary review, interviews |

| Innovation and learning | 5 | Documentary review, interviews, observation |

| Achieving goals | ||

| Patient satisfaction | 5 | Interviews |

| Efficiency | 5 | Documentary review, interviews |

| Efficiency | 4 | Documentary review, interviews |

| Culture (maintaining values) | ||

| Organizational values | 5 | Documentary review, interviews, observation |

| Organizational climate | 5 | Interviews |

| Production | ||

| Productivity | 3 | Documentary review, interviews |

| Volume of activity | 5 | Documentary review, interviews |

| Quality | 5 | Interviews, observation |

| Production coordination | 5 | Interviews, observation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).