Submitted:

07 March 2023

Posted:

09 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quality in Health (Hospital) Care

2.1.1. Definition of Quality in Health (Hospital) Care

- Safety is the capacity to avoid harm to patients;

- Effectiveness is related to "making the right things," which in health care corresponds to using scientific knowledge to treat patients in the best possible way;

- Patient-centeredness corresponds to human and social skills, necessary in any health care treatment as patients' needs, beliefs, values, preferences, gender, sexual orientation, and ethnicity must be respected;

- Timeliness is the capacity to provide care whenever the patient needs it, without potentially harmful delays;

- Unlikely effectiveness, efficiency (and productivity) is related to "making things right" without wasting resources; and

- Equity regards the fairness of resource distribution, as two patients in the same condition should receive equal treatment.

2.1.2. Quality Variables

-

Efficiency and productivity:

- a)

- Occupancy rate. This variable stands for the average rate of beds occupied by an inpatient each day (e.g., on an average day, 75 beds out of 150 were occupied; thus, the occupancy rate was 75/150 = 0.5 or 50%). The optimal occupancy rate ranges from 80 to 90%, being 85% frequently deemed as the optimal occupancy rate [54]. Less than 80% indicates underutilization of beds or excessive resources (low efficiency). In comparison, an occupancy rate above 90% suggests overutilization of beds and a lack of this resource for peak events, like during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic outbreaks. Furthermore, high occupancy rates tend to directly influence the incidence of hospital-acquired infections [55].

- b)

- Standard patients per Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) doctor. This indicator reflects the productivity of hospitals by relating the standardized number of patients seen and a resource (doctors in this case). More patients per FTE doctor means larger hospital productivity (monetization of an asset).

- c)

- Standard patients per FTE nurse is another productivity indicator with a similar interpretation.

-

Access:

- a)

- Rate of first medical appointments within the legally fixed period. There are two main ways of getting a medical appointment in a Portuguese public hospital: either through the emergency room or via health care centers (primary care). For the latter scenario, Portuguese legislation defines the maximum time between the request and the first appointment. This indicator measures how many patients have seen their access to secondary care denied or delayed. The larger the indicator, the better the access to care and, consequently, the hospital performance. During the Covid-19 pandemic, many non-urgent medical appointments were canceled, decreasing this indicator (and the access). Accordingly, the patients' health status may have worsened, reducing their quality of life and increasing the costs of future health services (as the severity of illness is positively associated with health expenditures; see Thuong et al. [56]).

- b)

- Rate of enrolled patients on the waiting list for surgery within the legally prescribed time. As before, there is a maximum legal time for patients to enroll on the waiting list for surgery, either major (requiring hospitalization) or minor. A low rate means that patients face difficulties accessing the service they need, i.e., a barrier that may result from administrative processes, bureaucracy, or lack of resources. During the Covid-19 pandemic, most non-urgent surgeries were canceled, meaning that this indicator (and the access) decreased. For instance, Ciarleglio et al. [57] and the CovidSurg Collaborative [58] reported the harmful effects of Covid-19 and lockdown on emergency and elective surgery due to delayed access.

- c)

- Average time before surgery. This indicator measures the average number of days the patients stay in the hospital ward after admission until they are surgically operated in the operating room. More significant average times mean that patients unnecessarily occupy a bed (and other resources) that another patient elsewhere could use.

- d)

- Rate of hip surgeries within the first 48h. This indicator quantifies the percentage of geriatric hip surgery within the first 48h after fracture (in the total hip surgeries). Hip fracture has long been reported as an essential predictor of in-hospital mortality in patients aged 65 years or older [59]. Two days (48h) of patient presentation is the limit of time recommended by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons for hip surgery [60] to prevent complications. Thus, this indicator is a good proxy for hospital timeliness. Interestingly, Brent et al. [61] observed a 15% reduction in admissions for hip surgery as well as a reduction in compliance with many surgery standards following the Covid-19 pandemic in Ireland.

-

Safety and care appropriateness:

- a)

- Bedsore rate. Bedsores or pressure ulcers are skin or underlying tissue injuries commonly found in low-mobility patients' heels, ankles, and hips, spending most of the in-hospital time lying on their beds. High rates indicate a considerable probability of bedridden patients developing skin wounds, thus jeopardizing their safety. Challoner et al. [62] mentioned that prone positioning has been employed to treat severe hypoxia in Covid-19 patients, which may constitute a risk of developing pressure ulcers on the head, neck, and genitalia. Sleiwah et al. [63] report similar findings regarding the perioral pressure ulcers resulting from using devices to secure endotracheal tubes in Covid-19 patients admitted to the intensive care units. These results thus suggest that patients' safety in terms of bedsores may have been compromised during the pandemic.

- b)

- Rate of in-hospital developed septicemia (postoperative). The indicator is the percentage of septicemia cases developed in-hospital divided by the total inpatients. Septicemia or nosocomial infection is caused by bacteria, viruses, and fungi and is acquired during hospital ward stays. If developed within the hospital (often in the postoperative period), this event results from the lack of patient safety, primarily poor cleanliness of materials. Some authors have reported an increase in nosocomially acquired infections during the Covid-19 pandemic, mostly because of ventilator-associated pneumonia and bacteremia [64,65]. Therefore, the literature suggests that this indicator has probably increased, implying that patients' clinical safety is worsening.

- c)

- Rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection events. Catheter-related bloodstream infections result from bacteremia in intravenous, not adequately sterilized catheters, being a significant cause of nosocomial bacteremia. These costly events and complications may cause high morbidity and mortality [66]. Recently, Pérez-Granda et al. [67] noticed an increase in the frequency of catheter-related bloodstream infections during the Covid-19 pandemic, claiming the need to reinforce classic and new preventive measures to avoid these events. The authors associate the increase of infections with the harsh circumstances (increased workload and use of staff with a sub-optimal degree of training with intensive care patients). However, other authors reached the opposite conclusions, e.g., Heidempergher et al. [68]. That being said, the literature is not clear about the effect of the pandemic on this indicator and, consequently, the hospital's performance regarding the patients' safety.

- d)

- Rate of postoperative pulmonary embolism events and thromboembolisms. Thromboembolisms occur when blood clots form in deep veins and break loose, traveling through the bloodstream, often to the lungs (pulmonary embolism). This event is more likely to occur after major surgeries or injuries. The consequences include blood flow and oxygen restrictions, damaging organs and tissues, and ultimately causing death. Narayan et al. [69] mentioned that hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, and about one in ten cases is preventable. Meanwhile, this value increases for critically ill patients due to elevated risk of thrombosis, like coma or paralysis [70,71]. Schulman [72] mentions that the best estimates indicate that about half a million Americans each year suffer from pulmonary embolisms. At least a tenth of a million deaths may be directly or indirectly related to these diseases, which are too many as this in-hospital death cause is highly preventable. Additionally, Covid-19 can lead to systemic coagulation activation and thrombotic complications [73], resulting in pulmonary embolism events and thromboembolisms. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Porfidia et al. [74] show that the incidence of this disease in Covid-19 patients is unclear.

- e)

- Rate of performed minor surgeries in the potential minor surgeries. Minor surgeries, like dental restorations and cataract surgeries, are minimally invasive procedures that do not require an operating theatre or an inpatient service admission. In opposition, major surgeries like cesarean sections, organ or joint replacements, total hysterectomies, and heart or bariatric surgeries usually involve opening the body and, consequently, major tissue trauma and a more significant risk of infection (worsening the patients' safety). Recoveries in these cases are more extended than minor surgeries. In many cases, however, one can solve the same problem through minor or major surgery. The best alternative depends on each case, but the benefits are frequently similar. Therefore, the infection risks and recovery period must not be overlooked nor outweighed. Medical guidelines argue that should the patient's clinical issue be appropriately solved through minor surgery, one should adopt it instead of a major procedure to reduce the risk of infection and recovery. Thus, the performance indicator is such that the closer to 100%, the better the care appropriateness. Baboudjian et al. [75] concluded that minor surgery is still safe in the Covid-19 era if all appropriate protective measures are implemented. This result suggests that there was no significant decrease in the indicator. Although many surgeries were canceled or postponed, the ones that were not could have been minor procedures (whenever appropriate) to limit the patient exposition to SARS-CoV-2, hopefully increasing this indicator.

- f)

- Rate of readmissions within 30 days after discharging. Readmitting patients after releasing them for the same reasons of the first admission results, in many cases, from poor care appropriateness. For instance, the patient was not totally healed and was incorrectly discharged, searching for health care for a while. However, it is usual that the clinical condition has worsened, making the patient's illness more severe and complex. The literature suggests that the 60-day readmission of Covid-19 survivors is less likely than that of pneumonia or heart failure survivors, but the opposite conclusion concerning the 10-day readmissions was also reached [76]. However, recent studies are more concerned with the readmission of Covid-19 patients than other patients readmitted in the Covid-19 era. Therefore, there is no clear evidence that total readmissions have increased or decreased in this period.

- g)

- Rate of inpatients staying hospitalized for more than 30 days. Staying in the hospital ward for more time than required dramatically increases the risk of acquiring severe nosocomial infections [77], developing other comorbidities, or even dying. With the pandemic's development, the risks associated with lengthy stays in the hospital may have increased, jeopardizing the patients' safety. For instance, the longer the patient stays in the inpatient service, the higher the probability of being infected by SARS-CoV-2; thus, the higher the risk of developing an often-fatal bacteria-related hospital-acquired pneumonia [78].

2.2. Performance Assessment Methods

2.2.1. The Benefit-of-Doubt Approach

2.2.2. Performance Evolution

2.2.3. A Relational Model

- x1.

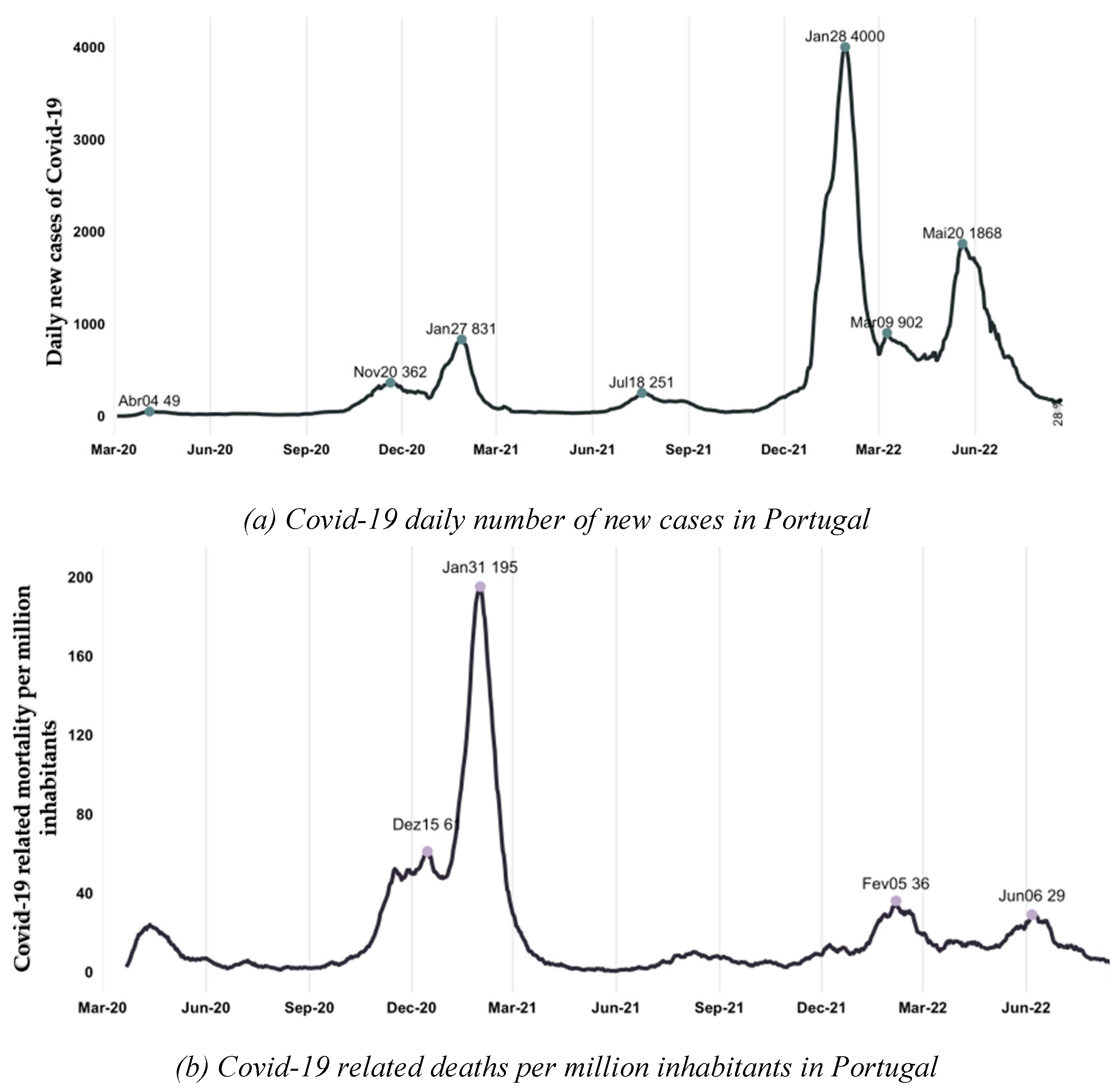

- Infected people per million inhabitants. The number of positive cases of SARS-CoV-2 multiplied by 1,000,000 and divided by the number of Portuguese inhabitants.

- x2.

- Covid-19-related deaths per million inhabitants. The number of deaths because of SARS-CoV-2 was multiplied by 1,000,000 and divided by the number of Portuguese inhabitants.

- x3.

- Reproduction rate. Usually represented by R, this rate is a standard transmissibility parameter that measures how many people can be infected by a positive case. For instance, R=2 means that one infected person can infect two people with the Covid-19 virus. Therefore, the reproduction rate must be below one to curb the spread of a pathogen.

- x4.

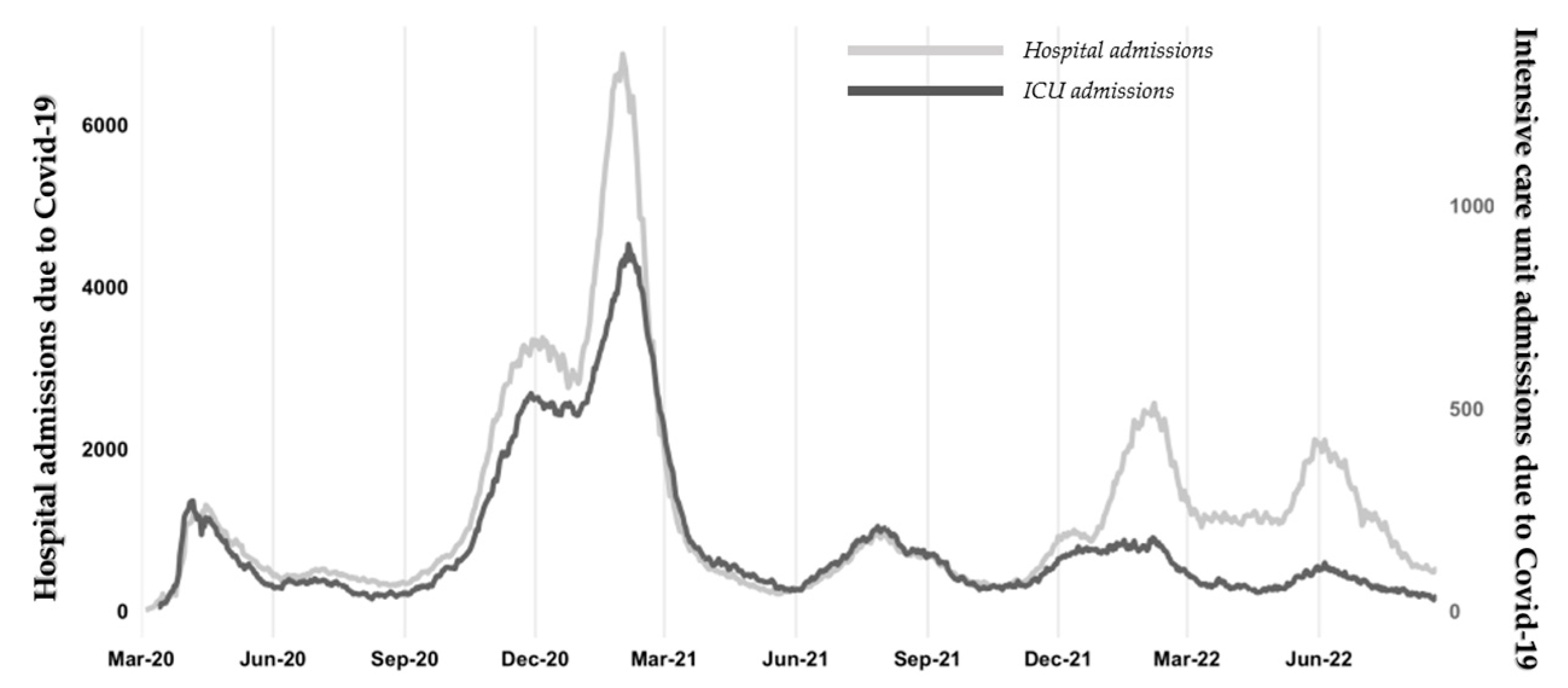

- Intensive care unit admissions (because of Covid-19) per million inhabitants. The number of Covid-19-related hospital entries requiring intensive care, multiplied by 1,000,000 and divided by the number of Portuguese inhabitants. The search for intensive care because of SARS-CoV-2 resulted from severe consequences of the disease like pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, multi-organ failure, septic shock, and, in many cases, death. Such a demand may have compromised the access to the same level of care by other patients as beds, and other resources (such as ventilators) are of limited availability.

- x5.

- Hospital admissions (because of Covid-19) per million inhabitants. The number of Covid-19-related hospital ward admissions not requiring intensive care, multiplied by 1,000,000 and divided by the number of Portuguese inhabitants. Although with less severe complications than those admitted to the intensive care unit, these inpatients also demand specialized nursery care. As in the previous case, this demand may constitute a barrier to access by other patients.

- x6.

- Vaccination (complete) rate. This indicator measures the percentage associated with the fully vaccinated population (BioNTech/Pfizer, Moderna, Novavax, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson). For instance, a citizen with a single shot of BioNTech/Pfizer is not considered as the minimum number of doses required is two. Evidence suggests that complete vaccination diminishes the severity of illness provoked by Covid-19, thus the need for hospitalizations and the burden on hospitals. This variable was zero until December 2020, when the first citizens got the shots.

- x7.

- Stringency index. According to the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker, the stringency index is a composite indicator based on nine response metrics related to the restrictions imposed by governments: school closures; workplace closures; cancellation of public events; restrictions on public gatherings; closures of public transport; stay-at-home requirements; public information campaigns; restrictions on internal movements; and international travel controls [94]. The index ranges from 0 to 100, the highest level associated with the strictest response. One of the major goals underlying the imposition of these restrictions is the reduction of infected people and, by extension, the hospital burden with patients requiring (often intensive) medical care.

2.3. The Case Study

2.3.1. The Portuguese National Health Service

2.3.2. Covid-19 in Portugal: Some Figures

3. Results

3.1. Efficiency and Productivity

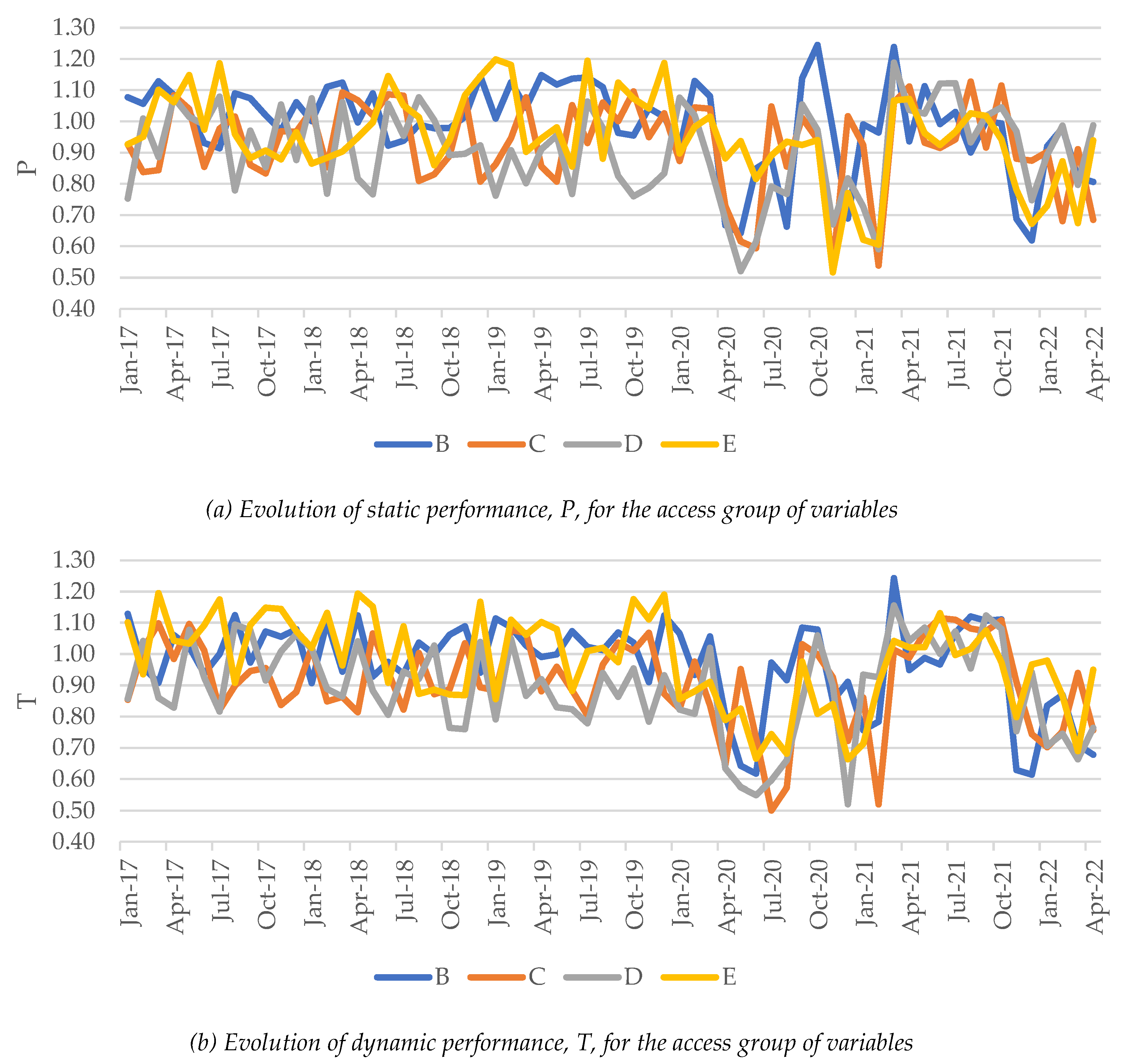

3.2. Access

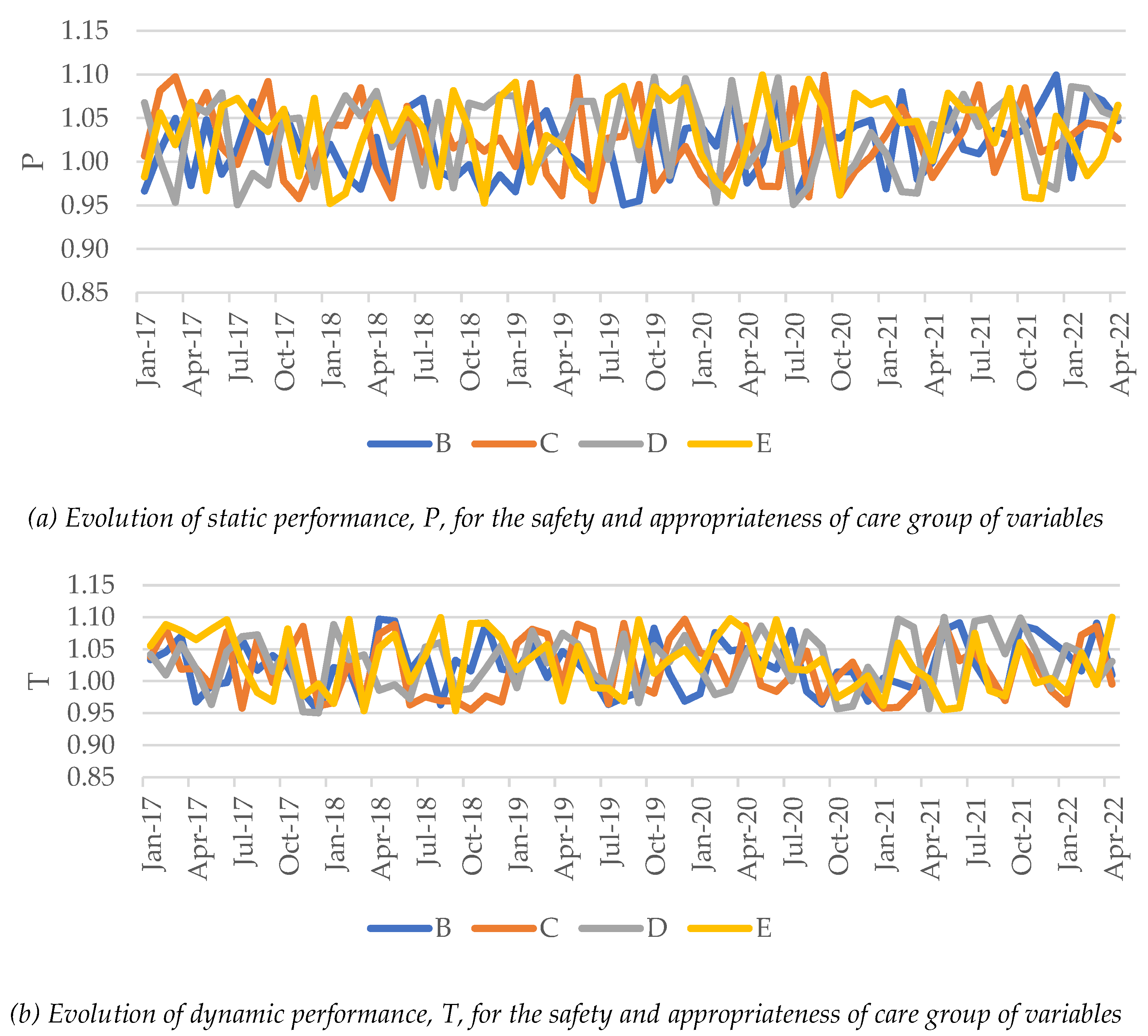

3.3. Safety and Care Appropriateness

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Data retrieved from the “Our World in Data” website, a project of the Global Change Data Lab founded by Max Roser and based at the University of Oxford. Website: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer [accessed December 10, 2022]. |

| 2 | The most recent hospital data regard May 2022. |

| 3 | In our study, the static performance concerns the efficiency and access to safe and appropriate hospital care at each moment. There is an empirical frontier (that should be close to a theoretical one) where benchmarks or best practices are placed in. The higher the distance to the frontier, the lower the performance level. The hospital performance is static should the frontier be constructed using data of just one moment (one year or month). When evaluating the performance evolution over time, one must account for two potential scenarios: the frontier and hospital shifts. The change in hospital position regarding the frontier (regardless of the frontier shift) constitutes the static performance evolution. However, benchmarks themselves may also change their positions with time, improving or worsening their performance. That way, the frontier will likely shift alongside the benchmarks. The relative position of two frontiers constructed using data from two instants constitutes the dynamic performance. |

| 4 | Data retrieved from https://www.pordata.pt/en/Subtheme/Portugal/Expenditure-37 (accessed: January 23, 2023). |

| 5 | Official website (in Portuguese): https://benchmarking-acss.min-saude.pt/ (accessed: January 23, 2023). |

| 6 | Our World in Data website: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus#explore-the-global-situation (accessed: December 23, 2022). |

| 7 | Until February 2021 only a very small share (6.3%) of the population had received one dose of the Covid-19 vaccine, thus inexpressive to significantly mitigate the impact of the disease in hospitals. |

References

- de Oliveira Toledo, S. L., Nogueira, L. S., das Graças Carvalho, M., Rios, D. R. A., & de Barros Pinheiro, M. (2020). Covid-19: Review and hematologic impact. Clinica Chimica Acta, 510, 170-176. [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, D., & Fielding, B. C. (2019). Coronavirus envelope protein: Current knowledge. Virology journal, 16(1), 1-22. (1). [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J. Ioannidis, J. (2021). Over-and under-estimation of Covid-19 deaths. European Journal of Epidemiology, 36(6), 581-588. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N., Zhang, D., Wang, W., Li, X., Yang, B., Song, J., ... & Tan, W. (2020). A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(8), 727-733. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. A., Dinis, D. C., Ferreira, D. C., Figueira, J. R., & Marques, R. C. (2022). A network Data Envelopment Analysis to estimate nations' efficiency in the fight against SARS-CoV-2. Expert Systems with Applications, 118362. [CrossRef]

- Ciotti, M., Ciccozzi, M., Terrinoni, A., Jiang, W. C., Wang, C. B., & Bernardini, S. (2020). The Covid-19 pandemic. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 57(6), 365-388. [CrossRef]

- Ndwandwe, D., & Wiysonge, C. S. (2021). Covid-19 vaccines. Current Opinion in Immunology, 71, 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C., Shao, W., Chen, X., Zhang, B., Wang, G., & Zhang, W. (2022). Real-world effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 114, 252-260. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D. A., & Meirinhos, V. (2021). Covid-19 lockdown in Portugal: Challenges, strategies and effects on mental health. Trends in Psychology, 29(2), 354-374. [CrossRef]

- Soares, P., Rocha, J. V., Moniz, M., Gama, A., Laires, P. A., Pedro, A. R., ... & Nunes, C. (2021). Factors associated with Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines, 9(3), 300. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A., Ricoca, V. P., Aguiar, P., Sousa, P., Nunes, C., & Abrantes, A. (2021). Years of life lost by Covid-19 in Portugal and comparison with other European countries in 2020. BMC public health, 21(1), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Pederneiras, Y. M., Pereira, M. A., & Figueira, J. R. (2023). Are the Portuguese public hospitals sustainable? A triple bottom line hybrid data envelopment analysis approach. International Transactions in Operational Research, 30(1), 453-475. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A. M., & Ferreira, D. C. (2022). Social Inequity and Health: From the Environment to the Access to Healthcare in Composite Indicators, the Portuguese Case. In Sustainable Policies and Practices in Energy, Environment and Health Research (pp. 371-389). Springer, Cham.

- Grossi, G., Kallio, K. M., Sargiacomo, M., & Skoog, M. (2019). Accounting, performance management systems and accountability changes in knowledge-intensive public organizations: A literature review and research agenda. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(1), 256-280. [CrossRef]

- Font, J. C., Levaggi, R., & Turati, G. (2022). Resilient managed competition during pandemics: Lessons from the Italian experience during Covid-19. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 17(2), 212-219. [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, F., Luzi, D., & Clemente, F. (2021a). Analysis of the different approaches adopted in the italian regions to care for patients affected by Covid-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 848. [CrossRef]

- Nepomuceno, T. C., Silva, W., Nepomuceno, K. T., & Barros, I. K. (2020). A DEA-based complexity of needs approach for hospital beds evacuation during the Covid-19 outbreak. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M. A., & Mousa, M. E. S. (2021). Measuring operational efficiency of isolation hospitals during Covid-19 pandemic using data envelopment analysis: A case of Egypt. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 28(7), 2178-2201. [CrossRef]

- Henriques, C. O., & Gouveia, M. C. (2022). Assessing the impact of Covid-19 on the efficiency of Portuguese state-owned enterprise hospitals. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 101387. [CrossRef]

- Aydin, N., & Yurdakul, G. (2020). Assessing countries' performances against Covid-19 via WSIDEA and machine learning algorithms. Applied Soft Computing, 97, 106792. [CrossRef]

- Taherinezhad, A., & Alinezhad, A. (2022). Nations performance evaluation during SARS-CoV-2 outbreak handling via data envelopment analysis and machine learning methods. International Journal of Systems Science: Operations & Logistics, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M. D., Binofai, F. A., & Mm Alshamsi, R. (2020). Pandemic response management framework based on efficiency of Covid-19 control and treatment. Future Virology, 15(12), 801-816. [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, D., Mariano, E. B., Manzine, P. R., Moralles, H. F., Morceiro, P. C., Torres, B. G., ... & Rebelatto, D. (2021). Covid health structure index: The vulnerability of Brazilian microregions. Social Indicators Research, 158(1), 197-215. [CrossRef]

- Mariano, E., Torres, B., Almeida, M., Ferraz, D., Rebelatto, D., & de Mello, J. C. S. (2021). Brazilian states in the context of Covid-19 pandemic: An index proposition using Network Data Envelopment Analysis. IEEE Latin America Transactions, 19(6), 917-924. [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, N., Yu, M. M., & See, K. F. (2021). Assessing the efficiency of Malaysia health system in Covid-19 prevention and treatment response. Health Care Management Science, 24(2), 273-285. [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, M., Loske, D., & Bicciato, S. (2022). Covid-19 health policy evaluation: Integrating health and economic perspectives with a data envelopment analysis approach. The European Journal of Health Economics, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, A., Romano, G., Campedelli, B., Moggi, S., & Leardini, C. (2018). Public vs. private in hospital efficiency: Exploring determinants in a competitive environment. International Journal of Public Administration, 41(3), 181-189. [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, F., Luzi, D., & Clemente, F. (2021b). The efficiency in the ordinary hospital bed management: A comparative analysis in four European countries before the Covid-19 outbreak. Plos One, 16(3), e0248867. [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, L., D’ambrosio, I., & Balsamo, M. (2020). Demographic and attitudinal factors of adherence to quarantine guidelines during Covid-19: The Italian model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 559288. [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, P., Taraghikhah, N., Jabbari, F., Ebrahimi, S., & Rezaei, N. (2022). Adherence of the general public to self-protection guidelines during the Covid-19 pandemic. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness, 16(3), 871-874. [CrossRef]

- Oyeyemi, O. T., Oladoyin, V. O., Okunlola, O. A., Mosobalaje, A., Oyeyemi, I. T., Adebimpe, W. O., ... & Ajiboye, A. A. (2022). Covid-19 pandemic: An online-based survey of knowledge, perception, and adherence to preventive measures among educated Nigerian adults. Journal of Public Health, 30(6), 1603-1612. [CrossRef]

- Rosko, M. D., & Chilingerian, J. A. (1999). Estimating hospital inefficiency: Does case mix matter? Journal of Medical Systems, 23(1), 57-71. [CrossRef]

- Adamuz, J., González-Samartino, M., Jiménez-Martínez, E., Tapia-Pérez, M., López-Jiménez, M. M., Rodríguez-Fernández, H., ... & Juvé-Udina, M. E. (2021). Risk of acute deterioration and care complexity individual factors associated with health outcomes in hospitalised patients with Covid-19: a multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open, 11(2), e041726. [CrossRef]

- Albitar, O., Ballouze, R., Ooi, J. P., & Ghadzi, S. M. S. (2020). Risk factors for mortality among Covid-19 patients. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 166, 108293. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., & Marques, R. C. (2019). Do quality and access to hospital services impact on their technical efficiency? Omega, 86, 218-236. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., Caldas, P., & Marques, R. C. (2021). Ageing as a determinant of local government performance: Myth or reality? The Portuguese experience. Local Government Studies, 47(3), 475-497. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., Marques, R. C., Nunes, A. M., & Figueira, J. R. (2018). Patients' satisfaction: The medical appointments valence in Portuguese public hospitals. Omega, 80, 58-76. [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. (1966). Evaluating the quality of medical care. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 44(3), 166-206. [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. (1988). The quality of care: How can it be assessed? JAMA, 260(12), 1743-1748. 1743. [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. (1990). The seven pillars of quality. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 114(11), 1115-1118. 1115.

- Ferreira, D. C., Marques, R. C., Nunes, A. M., & Figueira, J. R. (2021). Customers satisfaction in pediatric inpatient services: A multiple criteria satisfaction analysis. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 78, 101036. [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century (Vol. 323, No. 7322, p. 1192). British Medical Journal Publishing Group.

- Hibbard, J., & Pawlson, L. G. (2004). Why not give consumers a framework for understanding quality? The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety, 30(6), 347-351. [CrossRef]

- Ring, J. C., & Chao, S. M. (2006). Performance Measurement: Accelerating Improvement. Retrieved from Institute of Medicine (2006), https://www.ncvhs.hhs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/060222p1.pdf.

- Ferreira, D. C., Vieira, I., Pedro, M. I., Caldas, P., & Varela, M. (2023a). Patient Satisfaction with Healthcare Services and the Techniques Used for its Assessment: A Systematic Literature Review and a Bibliometric Analysis. In Healthcare (Vol. 11, No. 5, p. 639). MDPI.

- Amado, G. C., Ferreira, D. C., & Nunes, A. M. (2022). Vertical integration in healthcare: What does literature say about improvements on quality, access, efficiency, and costs containment? The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 37(3), 1252-1298. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., Marques, R. C., & Nunes, A. M. (2021). Pay for performance in health care: A new best practice tariff-based tool using a log-linear piecewise frontier function and a dual-primal approach for unique solutions. Operational Research, 21(3), 2101-2146. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., & Marques, R. C. (2020). A step forward on order-α robust nonparametric method: inclusion of weight restrictions, convexity and non-variable returns to scale. Operational Research, 20(2), 1011-1046. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., & Marques, R. C. (2021). Public-private partnerships in health care services: Do they outperform public hospitals regarding quality and access? Evidence from Portugal. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 73, 100798. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. A., Machete, I. F., Ferreira, D. C., & Marques, R. C. (2020). Using multi-criteria decision analysis to rank European health systems: The Beveridgian financing case. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 72, 100913. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., Nunes, A. M., & Marques, R. C. (2020a). Operational efficiency vs clinical safety, care appropriateness, timeliness, and access to health care. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 53(3), 355-375. 3. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., Nunes, A. M., & Marques, R. C. (2020b). Optimizing payments based on efficiency, quality, complexity, and heterogeneity: The case of hospital funding. International Transactions in Operational Research, 27(4), 1930-1961. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A., Costa, A. S., Figueira, J. R., Ferreira, D. C., & Marques, R. C. (2021). Quality assessment of the Portuguese public hospitals: A multiple criteria approach. Omega, 105, 102505. [CrossRef]

- Maaz, M., & Papanastasiou, A. (2020). Determining the optimal capacity and occupancy rate in a hospital: A theoretical model using queuing theory and marginal cost analysis. Managerial and Decision Economics, 41(7), 1305-1311. [CrossRef]

- Kaier, K., Mutters, N. T., & Frank, U. (2012). Bed occupancy rates and hospital-acquired infections – Should beds be kept empty? Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 18(10), 941–945. [CrossRef]

- Thuong, N. T., Van Den Berg, Y., Huy, T. Q., Tai, D. A., & Anh, B. N. H. (2021). Determinants of catastrophic health expenditure in Vietnam. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 36(2), 316-333. [CrossRef]

- Ciarleglio, F. A., Rigoni, M., Mereu, L., Tommaso, C., Carrara, A., Malossini, G., ... & Brolese, A. (2021). The negative effects of Covid-19 and national lockdown on emergency surgery morbidity due to delayed access. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 16(1), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- CovidSurg Collaborative (2021). Effect of Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns on planned cancer surgery for 15 tumour types in 61 countries: An international, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncology, 22, 1507-17. [CrossRef]

- Hjelholt, T. J., Johnsen, S. P., Brynningsen, P. K., Knudsen, J. S., Prieto-Alhambra, D., & Pedersen, A. B. (2022). Development and validation of a model for predicting mortality in patients with hip fracture. Age and Ageing, 51(1), afab233. [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S., Clapp, J. T., Burson, R. C., Fleisher, L. A., & Neuman, M. D. (2022). Physicians' perspectives of prognosis and goals of care discussions after hip fracture. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(5), 1487-1494. [CrossRef]

- Brent, L., Ferris, H., Sorensen, J., Valentelyte, G., Kelly, F., Hurson, C., & Ahern, E. (2022). Impact of Covid-19 on hip fracture care in Ireland: Findings from the Irish Hip Fracture Database. European Geriatric Medicine, 13(2), 425-431. [CrossRef]

- Challoner, T., Vesel, T., Dosanjh, A., & Kok, K. (2022). The risk of pressure ulcers in a proned Covid population. The Surgeon, 20(4), e144-e148. 4. [CrossRef]

- Sleiwah, A., Nair, G., Mughal, M., Lancaster, K., & Ahmad, I. (2020). Perioral pressure ulcers in patients with Covid-19 requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. European Journal of Plastic Surgery, 43(6), 727-732. [CrossRef]

- Bonazzetti, C., Morena, V., Giacomelli, A., Oreni, L., Casalini, G., Galimberti, L. R., Bolis, M., Rimoldi, M., Ballone, E., Colombo, R., Ridolfo, A. L., & Antinori, S. (2021). Unexpectedly high frequency of enterococcal bloodstream infections in Coronavirus disease 2019 patients admitted to an Italian ICU: An observational study. Critical Care Medicine, 49(1), e31–e40. [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, M. A., Tetaj, N., Selleri, M., Marchioni, L., Capone, A., Caraffa, E., Caro, A. D., Petrosillo, N., & INMICovid-19 Co-infection Group (2020). Incidence of bacterial and fungal bloodstream infections in Covid-19 patients in intensive care: An alarming "collateral effect". Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 23, 290–291. [CrossRef]

- Pitiriga, V., Kanellopoulos, P., Bakalis, I., Kampos, E., Sagris, I., Saroglou, G., & Tsakris, A. (2020). Central venous catheter-related bloodstream infection and colonization: The impact of insertion site and distribution of multidrug-resistant pathogens. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 9(1), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granda, M. J., Carrillo, C. S., Rabadán, P. M., Valerio, M., Olmedo, M., Muñoz, P., & Bouza, E. (2022). Increase in the frequency of catheter-related bloodstream infections during the Covid-19 pandemic: A plea for control. Journal of Hospital Infection, 119, 149-154. [CrossRef]

- Heidempergher, M., Sabiu, G., Orani, M. A., Tripepi, G., & Gallieni, M. (2021). Targeting Covid-19 prevention in hemodialysis facilities is associated with a drastic reduction in central venous catheter-related infections. Journal of Nephrology, 34(2), 345-353. [CrossRef]

- Narayan, S. W., Gad, F., Chong, J., Chen, V. M., & Patanwala, A. E. (2021). Preventability of venous thromboembolism in hospitalised patients. Internal Medicine Journal. [CrossRef]

- Nyquist, P., Bautista, C., Jichici, D., Burns, J., Chhangani, S., DeFilippis, M., ... & Meyer, K. (2016). Prophylaxis of venous thrombosis in neurocritical care patients: an evidence-based guideline: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society. Neurocritical Care, 24(1), 47-60. [CrossRef]

- Sauro, K. M., Soo, A., Kramer, A., Couillard, P., Kromm, J., Zygun, D., ... & Stelfox, H. T. (2019). Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in neurocritical care patients: Are current practices, best practices? Neurocritical Care, 30(2), 355-363. [CrossRef]

- Schulman, S. (2020). Is venous thromboembolism a preventable cause of death? The Lancet Haematology, 7(8), e555-e556. [CrossRef]

- Middeldorp, S., Coppens, M., van Haaps, T. F., Foppen, M., Vlaar, A. P., Müller, M. C., ... & van Es, N. (2020). Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 18(8), 1995-2002. [CrossRef]

- Porfidia, A., Valeriani, E., Pola, R., Porreca, E., Rutjes, A. W., & Di Nisio, M. (2020). Venous thromboembolism in patients with Covid-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thrombosis research, 196, 67-74. [CrossRef]

- Baboudjian, M., Mhatli, M., Bourouina, A., Gondran-Tellier, B., Anastay, V., Perez, L., ... & Lechevallier, E. (2021). Is minor surgery safe during the Covid-19 pandemic? A multi-disciplinary study. PloS One, 16(5), e0251122. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J. P., Wang, X. Q., Iwashyna, T. J., & Prescott, H. C. (2021). Readmission and death after initial hospital discharge among patients with Covid-19 in a large multihospital system. JAMA, 325(3), 304-306. [CrossRef]

- Wolkewitz, M., Zortel, M., Palomar-Martinez, M., Alvarez-Lerma, F., Olaechea-Astigarraga, P., & Schumacher, M. (2017). Landmark prediction of nosocomial infection risk to disentangle short-and long-stay patients. Journal of Hospital Infection, 96(1), 81-84. [CrossRef]

- Tellapragada, C., & Giske, C. G. (2021). The Unyvero Hospital-Acquired pneumonia panel for diagnosis of secondary bacterial pneumonia in Covid-19 patients. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 40(12), 2479-2485. [CrossRef]

- Sibert, N. T., Pfaff, H., Breidenbach, C., Wesselmann, S., & Kowalski, C. (2021). Different approaches for case-mix adjustment of patient-reported outcomes to compare healthcare providers – methodological results of a systematic review. Cancers, 13(16), 3964. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., & Marques, R. C. (2016a). Should inpatients be adjusted by their complexity and severity for efficiency assessment? Evidence from Portugal. Health Care Management Science, 19(1), 43-57. [CrossRef]

- Herr, A. (2008). Cost and technical efficiency of German hospitals: does ownership matter? Health Economics, 17(9), 1057-1071. [CrossRef]

- Cherchye, L., Moesen, W., Rogge, N., & Puyenbroeck, T. V. (2007). An introduction to 'benefit of the doubt' composite indicators. Social Indicators Research, 82(1), 111-145. [CrossRef]

- Cherchye, L., Moesen, W., Rogge, N., & Van Puyenbroeck, T. (2011). Constructing composite indicators with imprecise data: A proposal. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(9), 10940-10949. [CrossRef]

- Rogge, N. (2018). On aggregating benefit of the doubt composite indicators. European Journal of Operational Research, 264(1), 364-369. [CrossRef]

- Bernini, C., Guizzardi, A., & Angelini, G. (2013). DEA-like model and common weights approach for the construction of a subjective community well-being indicator. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 405-424. [CrossRef]

- Greco, S., Ishizaka, A., Tasiou, M., & Torrisi, G. (2019). On the methodological framework of composite indices: A review of the issues of weighting, aggregation, and robustness. Social Indicators Research, 141(1), 61-94. [CrossRef]

- Decancq, K., & Lugo, M. A. (2013). Weights in multidimensional indices of wellbeing: An overview. Econometric Reviews, 32(1), 7-34. [CrossRef]

- Tourinho, M., Santos, P. R., Pinto, F. T., & Camanho, A. S. (2021). Performance assessment of water services in Brazilian municipalities: An integrated view of efficiency and access. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 101139. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., Caldas, P., Varela, M., & Marques, R. C. (2023b). A geometric aggregation of performance indicators considering regulatory constraints: An application to the urban solid waste management. Expert Systems with Applications, 119540. [CrossRef]

- Matos, R., Ferreira, D., & Pedro, M. I. (2021). Economic analysis of Portuguese public hospitals through the construction of quality, efficiency, access, and financial related composite indicators. Social Indicators Research, 157(1), 361-392. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., & Marques, R. C. (2016b). Malmquist and Hicks–Moorsteen productivity indexes for clusters performance evaluation. International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making, 15(05), 1015-1053. [CrossRef]

- Portela, M. C. A. S., & Thanassoulis, E. (2006). Malmquist indexes using a geometric distance function (GDF). Application to a sample of Portuguese bank branches. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 25(1), 25-41. [CrossRef]

- Portela, M. C., & Thanassoulis, E. (2007). Developing a decomposable measure of profit efficiency using DEA. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 58(4), 481-490. [CrossRef]

- Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., ... & Tatlow, H. (2021). A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker). Nature Human Behaviour, 5(4), 529-538. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.M., Ferreira, D.C., & Campos Fernandes, A. (2019). Financial crisis in Portugal: Effects in the health care sector. International Journal of Health Services, 49(2), 237-259. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A. M., & Ferreira, D. C. (2019a). Reforms in the Portuguese health care sector: Challenges and proposals. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 34(1), e21-e33. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A. M., & Ferreira, D. C. (2019b). The health care reform in Portugal: Outcomes from both the New Public Management and the economic crisis. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 34(1), 196-215. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., & Nunes, A. M. (2019). Technical efficiency of Portuguese public hospitals: A comparative analysis across the five regions of Portugal. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 34(1), e411-e422. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., Nunes, A. M., & Marques, R. C. (2018). Doctors, nurses, and the optimal scale size in the Portuguese public hospitals. Health Policy, 122(10), 1093-1100. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D., & Marques, R. C. (2015). Did the corporatization of Portuguese hospitals significantly change their productivity? The European Journal of Health Economics, 16(3), 289-303. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. C., Marques, R. C., & Nunes, A. M. (2018). Economies of scope in the health sector: The case of Portuguese hospitals. European Journal of Operational Research, 266(2), 716-735. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D., & Marques, R. C. (2018). Identifying congestion levels, sources and determinants on intensive care units: The Portuguese case. Health Care Management Science, 21(3), 348-375. [CrossRef]

- Cook, W. D., Ramón, N., Ruiz, J. L., Sirvent, I., & Zhu, J. (2019). DEA-based benchmarking for performance evaluation in pay-for-performance incentive plans. Omega, 84, 45-54. [CrossRef]

| Institute of Medicine | Donabedian [38,39,40] | Ferreira & Marques [35], Ferreira, Marques, Nunes & Figueira [37,41] |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | Process | Safety |

| Effectiveness | Results | Patient satisfaction, quality of life improvement, care appropriateness |

| Patient-centeredness | Process | Care appropriateness |

| Timeliness | Attributes | Access |

| Efficiency (and productivity) | Attributes | Efficiency and productivity |

| Equity | Attributes | Access |

| Group | jan/2017-feb/2020 | mar/2020-may/2022 | mar/2020-feb/2021 | mar/2021-may/2022 | Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static performance | |||||

| B | 0.9995 | 1.0261 | 1.0205 | 1.0309 | 1.0102 |

| C | 0.9882 | 1.0033 | 1.0047 | 1.0021 | 0.9943 |

| D | 0.9559 | 1.0396 | 1.0421 | 1.0374 | 0.9890 |

| E | 0.9554 | 1.0252 | 1.0244 | 1.0259 | 0.9832 |

| Dynamic performance | |||||

| B | 0.9977 | 0.9674 | 0.9559 | 0.9774 | 0.9853 |

| C | 0.9835 | 0.9752 | 0.9594 | 0.9889 | 0.9801 |

| D | 0.9626 | 0.9676 | 0.9508 | 0.9823 | 0.9646 |

| E | 0.9591 | 0.9633 | 0.9573 | 0.9684 | 0.9608 |

| Total Factor Productivity | |||||

| B | 0.9972 | 0.9927 | 0.9755 | 1.0076 | 0.9954 |

| C | 0.9719 | 0.9784 | 0.9639 | 0.9910 | 0.9745 |

| D | 0.9201 | 1.0059 | 0.9908 | 1.0190 | 0.9540 |

| E | 0.9164 | 0.9876 | 0.9806 | 0.9935 | 0.9446 |

| Variables | P | T | TFP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.041 | 0.967 | 0.999 | |

| x1. | Infected people per million inhabitants | * | 0.300 | 0.159 |

| x2. | Covid-19-related deaths per million inhabitants | * | * | * |

| x3. | Reproduction rate | * | 0.689 | 0.314 |

| x4. | Intensive care unit admissions (because of Covid-19) per million inhabitants | * | 0.188 | 0.254 |

| x5. | Hospital admissions (because of Covid-19) per million inhabitants | * | 0.963 | 0.216 |

| x6. | Vaccination (complete) rate | * | * | * |

| x7. | Stringency index | * | -0.252 | -0.141 |

| Coefficient of determination, R2 | 0.039 | 0.561 | 0.211 | |

| Does the model violate the residuals' normality? (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) | No | No | No | |

| Does the model violate the residuals' homoskedasticity? | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Does the model violate the residuals' independence? (Durbin-Watson test) | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Group | jan/2017-feb/2020 | mar/2020-may/2022 | mar/2020-feb/2021 | mar/2021-may/2022 | Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static performance | |||||

| B | 1.0392 | 0.8990 | 0.8777 | 0.9176 | 0.9797 |

| C | 0.9543 | 0.8617 | 0.7957 | 0.9225 | 0.9155 |

| D | 0.9164 | 0.8638 | 0.7421 | 0.9838 | 0.8947 |

| E | 1.0001 | 0.8516 | 0.8054 | 0.8933 | 0.9368 |

| Dynamic performance | |||||

| B | 1.0195 | 0.8799 | 0.8588 | 0.8984 | 0.9603 |

| C | 0.9372 | 0.8494 | 0.7529 | 0.9420 | 0.9005 |

| D | 0.9069 | 0.8341 | 0.7450 | 0.9190 | 0.8766 |

| E | 1.0299 | 0.8757 | 0.7872 | 0.9595 | 0.9642 |

| Total Factor Productivity | |||||

| B | 1.0594 | 0.7910 | 0.7538 | 0.8244 | 0.9408 |

| C | 0.8943 | 0.7319 | 0.5991 | 0.8690 | 0.8244 |

| D | 0.8311 | 0.7205 | 0.5529 | 0.9040 | 0.7843 |

| E | 1.0299 | 0.7457 | 0.6340 | 0.8571 | 0.9033 |

| Variables | P | T | TFP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.875 | 0.859 | 0.755 | |

| x1. | Infected people per million inhabitants | * | * | * |

| x2. | Covid-19-related deaths per million inhabitants | * | * | * |

| x3. | Reproduction rate | * | * | * |

| x4. | Intensive care unit admissions (because of Covid-19) per million inhabitants | -0.567 | -0.828 | -0.549 |

| x5. | Hospital admissions (because of Covid-19) per million inhabitants | -0.440 | -0.323 | -0.624 |

| x6. | Vaccination (complete) rate | * | * | * |

| x7. | Stringency index | -0.927 | -0.840 | -0.757 |

| Coefficient of determination, R2 | 0.725 | 0.668 | 0.590 | |

| Does the model violate the residuals' normality? (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) | No | No | No | |

| Does the model violate the residuals' homoskedasticity? | No | No | No | |

| Does the model violate the residuals' independence? (Autocorrelation test) | No | No | No | |

| Group | jan/2017-feb/2020 | mar/2020-may/2022 | mar/2020-feb/2021 | mar/2021-may/2022 | Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static performance | |||||

| B | 1.0074 | 1.0292 | 1.0215 | 1.0359 | 1.0162 |

| C | 1.0223 | 1.0221 | 1.0133 | 1.0297 | 1.0222 |

| D | 1.0315 | 1.0262 | 1.0113 | 1.0392 | 1.0294 |

| E | 1.0294 | 1.0335 | 1.0403 | 1.0276 | 1.0310 |

| Dynamic performance | |||||

| B | 1.0192 | 1.0269 | 1.0141 | 1.0380 | 1.0223 |

| C | 1.0223 | 1.0140 | 1.0004 | 1.0257 | 1.0189 |

| D | 1.0244 | 1.0346 | 1.0252 | 1.0428 | 1.0286 |

| E | 1.0342 | 1.0185 | 1.0281 | 1.0104 | 1.0278 |

| Total Factor Productivity | |||||

| B | 1.0267 | 1.0569 | 1.0359 | 1.0753 | 1.0389 |

| C | 1.0452 | 1.0364 | 1.0138 | 1.0562 | 1.0416 |

| D | 1.0567 | 1.0618 | 1.0367 | 1.0837 | 1.0588 |

| E | 1.0646 | 1.0526 | 1.0696 | 1.0383 | 1.0597 |

| Variables | P | T | TFP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.001 | 1.015 | 1.056 | |

| x1. | Infected people per million inhabitants | * | * | * |

| x2. | Covid-19-related deaths per million inhabitants | * | * | * |

| x3. | Reproduction rate | * | * | * |

| x4. | Intensive care unit admissions (because of Covid-19) per million inhabitants | * | * | * |

| x5. | Hospital admissions (because of Covid-19) per million inhabitants | * | * | * |

| x6. | Vaccination (complete) rate | * | * | * |

| x7. | Stringency index | * | * | * |

| Coefficient of determination, R2 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Does the model violate the residuals' normality? (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) | No | No | No | |

| Does the model violate the residuals' homoskedasticity? | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Does the model violate the residuals' independence? (Autocorrelation test) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).