1. Introduction

Sustainability has become an important goal for many corporations, but operationalization and implementation may be difficult. A basic premise of business management is that clarity about organizational goals is essential for superior performance. Goals vary, affected by many dimensions--environmental context, risk elements, the availability of raw components, suppliers, employees, and other inputs, consumer or client preferences, capital resources, and many other factors. The primary objective for business has been performance for many decades, albeit defined and measured in many ways.

However, once in a century a new focus may emerge that transcends industries, companies, and nations. Sustainability has become this kind of transcending goal, a central element reflected in policies and practices of businesses, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and nations themselves. This paper considers how businesses can balance the demands of performance and sustainability. First, we discuss a particular set of organizations that have endured for decades, even centuries, maintaining a balance between conflicting goals that include sustainability. These are botanical gardens. First, we examine how botanical gardens balance environmental, social, and economic goals in ways that could provide a helpful model for businesses attempting to realize similarly discrepant goals. Second, we describe the methodology based on intentional sampling and content analysis. Third, we observe the extent of recognition of social, economic, and environmental aspects of sustainability in businesses from the US, Europe, and Asia and in botanical gardens. We evaluate the significance of differences demonstrated. Finally, we suggest limitations of the research, areas for future research, and implications for practitioners in both botanical gardens and businesses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Why Botanical Gardens?

Botanical gardens are particularly interesting because they typically have conflicting goals, much like businesses that attempt to fulfill both traditional performance and new sustainability goals. On the one hand, botanical gardens often have an ardent community following, a set of local volunteers who play important roles in educational programs, fundraising, and maintaining the more entertainment focused operations of the organization. On the other hand, they usually have a scientifically oriented staff with interests in collecting new species, preserving threatened species, developing germ seed banks, collaborating with other institutions on a national and international level to deal with issues like genetic diversity, and other environmentally oriented topics. The volunteers who run the gift shop may have little understanding of what is going on in the germ seed lab, and the scientists running the germ seed lab may have equally little interest in the gift shop operations.

Sustainability as an orientation can unite but can also disrupt. In the case of botanical gardens, resources going toward the scientific side may not do much to increase attendance of visitors and the revenue they generate. Ironically, increasing the focus on and resources devoted to festivals, restaurants, and souvenir items, increasingly important for revenue generation, may even distract administrative and managerial attention to the scientific mission and goals. However, advances in the science of botany and its applications toward maintaining vital ecological processes are essential elements of the mission of most botanical gardens, though they may be of little interest to the local community and recreational visitors.

2.2. Botanical Garden Stakeholders: Past, Present, and Future

There are about 296 major botanical gardens in the United States (US), and as many as 1359 botanical gardens including those of lesser prominence [

1]. Botanical gardens in the US evolved from multiple sources, including medicinal and herbal gardens of indigenous populations and kitchen gardens of early farms, explorers bringing back species representing the spirit of new discovery and exploration, and early industrialists looking for new products that had commercial potential. Other early US supporters came with the age of “Gilded Age” exhibitionism, the institutionalization of botany as a scientific endeavor, and more recently, public concern for environmentalism and sustainability. In Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America botanical gardens going back to prehistoric times served both practical purposes and demonstrated the power, aesthetic sensibilities, and resources of rulers and other privileged elites. The ancient gardens of Biblical and pre-Biblical times were celebrated sources of status for rulers and attraction for ruling elites. Indigenous societies and early empires also employed botanical knowledge in many ways that we have yet to fully appreciate. Herb gardens were a usual part of early agriculture and household management, and much of the exploration and development of early modern international trade was built on the spice trade as well as trade in tobacco, tea, coffee, and chocolate [

2].

Today, botanical gardens remain a source of national pride as well as a means for new ideas in sustainability and environmental adaptation in developing countries which face some of the most difficult challenges in maintaining viable agricultural as well as conserving species which may be unique or unusually suited to their environment [

3] Since many other countries and cultures have botanical gardens that go back to ancient times, this study includes an international set of prominent botanical gardens.

Formally designated botanical gardens in the US started as private collections at the beginning of the 1800s. Entrepreneurs and explorers searched distant lands and newly acquired territories at home and abroad for curiosities as well as products that might provide viable commercial opportunities. Private gardens provided an outlet for women to express their talents by creating beautiful gardens when they were excluded from the formal arenas of art and business. DeMaio [

4] argues that botanical gardens in the United States developed as a parallel process between two social forces—the institutionalization of science and the expansion of US state power. She says the collection and classification of species, especially those in the newly explored Western territories of the US, represent a democratization of science.

2.3. Sustainability in Botanical Gardens

Botanical gardens require financial support. In the US, private families and business leaders often provided support for early botanical exploration, sometimes with the intent to find resources that could be exploited for new industrial products and inventions. In the next phase government support became more important for botanical research. Modernizing agriculture was essential for the economic development of the nation from the Depression years of the 1930s when much botanical support came from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) which had been created by President Abraham Lincon in 1862. This development operated on a parallel track from the growth and popularization of botanical gardens, but both constituted elements of the institutionalization of science and its use for the common good. In modern times, community support and grass-roots attendance has become an important source of revenue, a considerable part of which goes to support scientific research and environmental endeavors. The typical botanical garden depends on a variety of income streams from local, state, and federal government, research grants, philanthropy, souvenir and gift shop sales, hospitality, entrance fees, memberships, and fees for special events.

In the 21st century the image and mission of US botanical gardens is still evolving. Social and environmental responsibility are key mission drivers [

5]. Yet the public perceives botanical gardens as a place for education in subjects such as plant cultivation, cooking, drawing, painting, and photography. Recreation and entertainment are emphasized more than in the past, with exhibitions such as Christmas lights, Halloween shows, and other activities designed to appeal to more of the public. Activities aimed for children are growing in popularity. Physical activities such as yoga classes appeal to another audience. Botanical gardens serve as a venue for flower show exhibitions and competitions, a site for weddings and other social activities, and a gathering place for the community of nature lovers and, in some communities, a social elite. Volunteers are heavily involved in these activities, while the scientists in the organization are more involved in behind-the-scenes work.

Yet most US botanical gardens retain a strong commitment to science. Important research continues to be conducted. Some botanical gardens have seed banks to ensure against species decline or extinction. Some do genetic analysis and manipulation. Species collection and categorization continue. New pharmaceutical and agricultural applications of traditional plants are explored. Novel approaches to conservation and preservation of species are proposed and promoted. Botanical garden scientists give advice to urban planners and environmentalists and provide data to support ecological projects. Climate change is a reality that heavily influences the direction of botanical garden science.

2.4. Sustainability in Business

From a management point of view, nothing is more important for organizational effectiveness than clarity of mission. For business there was a prolonged period when profit maximization (called “performance”) was the undisputed goal. However, in the past half-century, sustainability has become a transcendent goal for many businesses and other organizations such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and government entities. While many antecedents of the idea of sustainability could be mentioned, the seminal event usually considered to have defined the era was the work of the 1983 United Nations Commission on Environment and Development known as the Brundtland Commission. The commission's 1987 Brundtland Report provided a definition of sustainable development. The report,

Our Common Future [

6], defined it as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs". This United Nations report brought sustainability into the mainstream of policy discussions and popularized the concept of sustainable development. Sustainability includes at least three important dimensions—people, planet, and profits, or put another way, social, environmental, and economic. These three elements have been integral to botanical garden management for many decades. Profits obviously correspond to the performance aspect emphasized by business, and for some businesses the social element is given much attention. For consumer business and services, the social dimension is often recognized, but this happens to a lesser extent for industrial products. Asian, Latin American, and Middle Eastern cultures tend to emphasize the social aspect more than US culture. The environmental dimension is recognized globally, but government policies vary, and companies vary in their implementation of stated policies.

In the United States scholarly associations such as the Academy of Management and the Academy of International Business began to stress the importance of goals other than maximizing profits around the time a sensitivity to environmental issues was developing. The social upheavals of the 1960s—the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, consumer activism, the anti-apartheid movement, and the environmental movement all challenged conventional notions of effective management and how businesses should operate. Business ethics, socially responsible investing (SRI), and corporate social responsibility (CSR) came to be included in management texts. Freeman’s book

Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach [

7] articulated an original approach to goal definition, one admitting the legitimacy of pursuing business goals not necessarily directly aligned with profit maximization. This way of thinking came to be called “stakeholder management,” in contrast to the older orientation that centered on what was perceived as profit-making. Freeman did not object to profit-making but called attention to the interests of various stakeholders such as employees, consumers, communities, regulatory bodies, trade and professional associations, suppliers, and others. In the decades since then considerable research has been done on the extent to which consideration of which of these stakeholders have goals consistent with or opposed to profit-making, under what conditions they have legitimacy, how they change over time, and how to set goals and measure achievements in various realms of what came to be called corporate social responsibility (CSR).

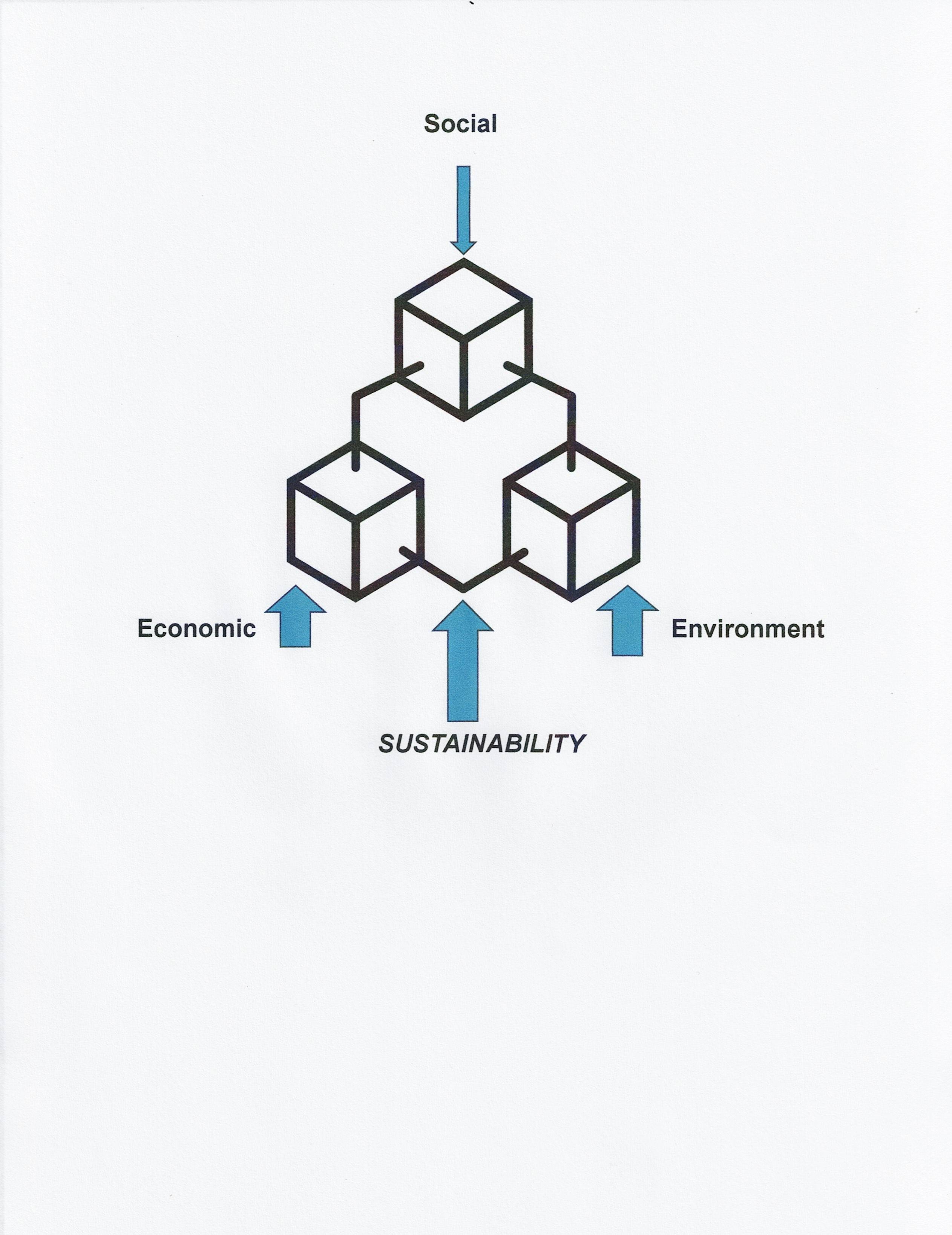

Three factors (economy, environment, and society) are dimensions of sustainable development that require attention. The term Triple Bottom Line (TBL) was coined [

8] and became widespread with the publication of the book

Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century [

9]. The Triple Bottom Line (TBL), sometimes called “the three Ps”—people, profits, planet—has become one of the most popular frameworks for organizations to measure sustainability. This framework has been widely used by NGOs and consulting companies as well as businesses.

2.5. Sustainability Issues for Botanical Gardens and Businesses

For botanical gardens, this new public consciousness of environmentalism and social responsibility required closer analysis of what their goals and measurable objectives should be, and how goals and objectives could be accomplished. For example, attendance metrics might be a traditional measure of success, but what if those attending represent only a small slice of the demography of the community who have the discretionary time to come and the discretionary money to pay entrance fees or membership dues? What if the attendance skews towards an age group like retirees, whose social impact will be limited in the future, rather than children and youth whose ideas about nature and the environment will influence decisions for generations to come? Botanical gardens provide a respite from the hustle and bustle of city life, but responsible environmentalism requires consideration of how urban areas incorporate nature, both to provide pleasure for ordinary urban life and to mitigate damage that occurs with the destruction of the natural environment. What about climate change? As territory becomes inhospitable to existing flora and fauna, what adaptations are required by communities? What kinds of pressures do policymakers face? How botanical gardens resolve the conflicting interests of disparate interest groups can provide a model for businesses facing divergent demands as sustainability goals challenge performance goals. For businesses, sustainability is not such an inherent responsibility as it is for botanical gardens. Yet, businesses have such an impact on society that their commitment or lack of commitment, or even resistance, drives the worldwide movement toward success or futility in maintaining a sustainable planet.

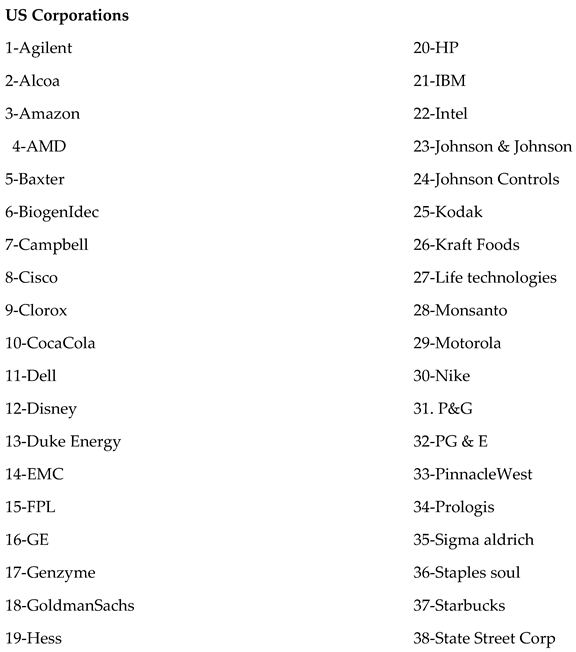

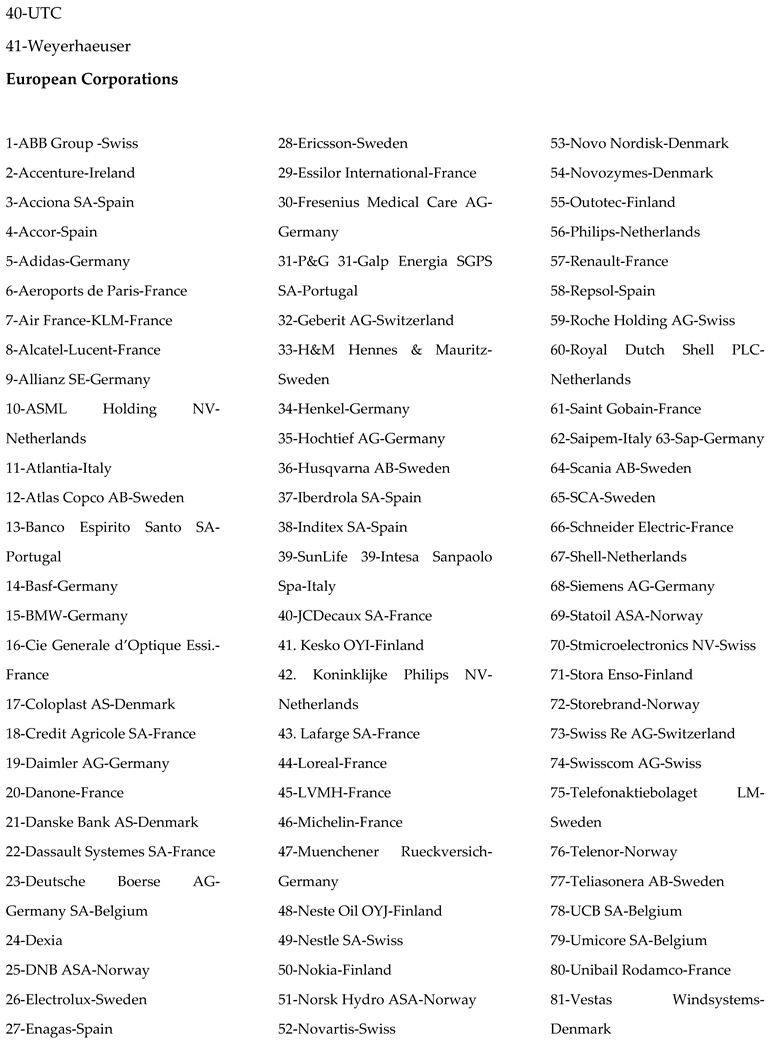

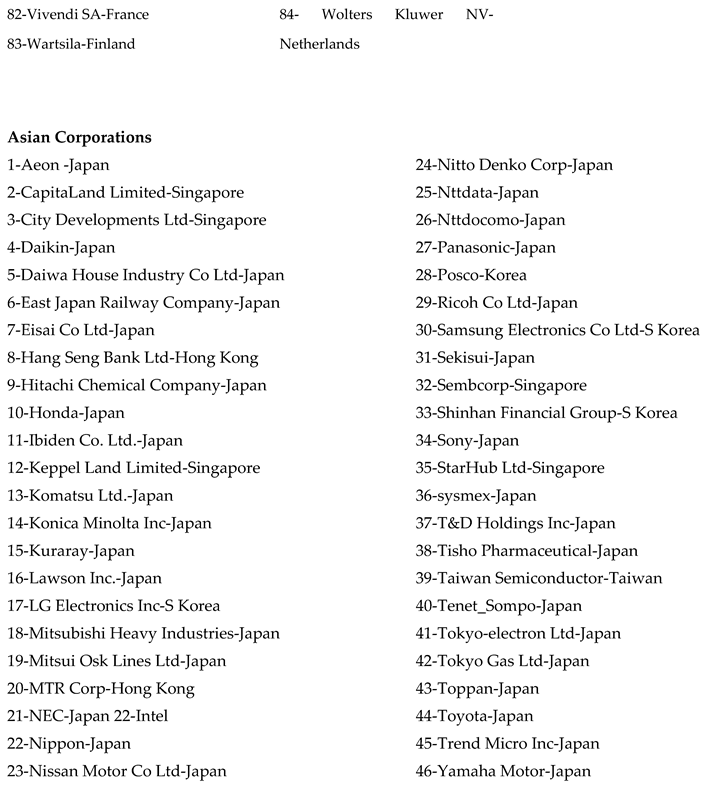

This paper uses content analysis to compare the inclusion of sustainability in annual reports of businesses in the US, Europe, and Asia with annual reports of botanical gardens, and then to compare the three dimensions of sustainability demonstrated by businesses and botanical gardens. The businesses included have been recognized for exemplary sustainability efforts by a consulting firm employed by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). The dimensions of sustainability measured include social, economic, and environmental dimensions. This sample is an intentional sample of businesses recognized for positive achievements in sustainability. Businesses not recognizing sustainability or doing poorly on their implementation are not included. Intentional sampling was chosen because it was possible to obtain a reasonable number of companies in the US, Europe, and Asia, enabling an international dimension to be obtained with a reasonable number for analysis. If many thousands of companies not exhibiting an interest in sustainability had been included, statistical significance would have had little meaning. The list of exemplary companies is shown in

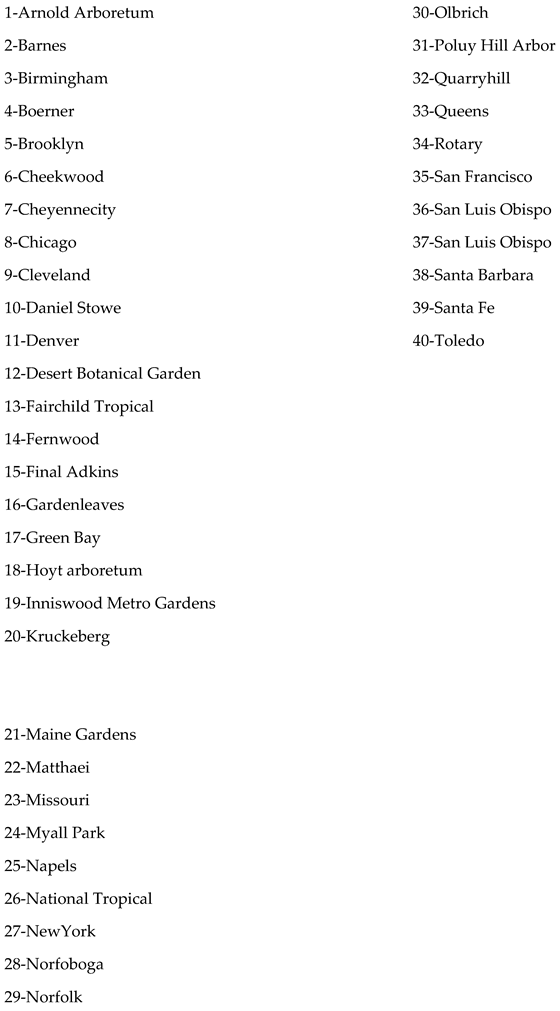

Appendix A. The selection of botanical gardens was also an intentional sampling of prominent botanical gardens internationally as defined by membership in associations of botanical gardens and categorization by governments or other organizations, obtainable only by an intentional sample. The list of botanical gardens is shown in

Appendix B.

2.5. Methods.

Annual reports were used to analyze the extent to which sustainability was recognized or measured in annual reports. Some previous studies have used sustainability reports or citizenship reports to assess the importance of sustainability, but annual reports were used in this study because the object of the study was to assess the different dimensions of sustainability in the total context of organizational priorities rather than in a report developed specifically for stakeholders looking for sustainability as a priority.

The technique used for analysis was content analysis, a method whereby the presence of specific words or themes in communications is analyzed. Researchers can investigate the meaning contained in a text or item through the lens provided by the text or item itself rather than some subjective or predetermined element. Words or themes used by different entities can be compared and examined for changes over time. Analysis can be of text, images, videos, interviews, blogs, webpages, and most forms of communication. Berelson describes content analysis as a research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the content of communication [

10]. Holsti describes content analysis as any technique for making inferences by objectively and systematically identifying specified characteristics of messages [

11]. Mayring defines content analysis as an approach of empirical, methodological controlled analysis of texts within their context of communication, following content analytical rules and step by step models, without rash quantification [

12]. Hsieh & Shannon assert that content analysis is a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns [

13]. Krippendorf says content analysis is a technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use [

14].

Content analysis provides flexibility to researchers. It can be applied in qualitative or quantitative research. It simplifies the data under analysis, providing a way of identifying themes and meanings that might not be apparent in raw text, giving systematic analysis to textual materials, reducing subjective bias and dependence on existing paradigms. Various computer programs have been developed that enable researchers to conduct content analysis, coding the texts and contents in even large samples and analyzing data with various quantitative methods. The unit of analysis can be words, terms, themes, characters, paragraphs, items, concepts, and semantics [

15].

The unit of analysis for this study was word since it makes the analysis simpler and more objective. A list of important and meaningful words was developed by Dickinson, Gill, Purushothaman, and 112 Scharl [

16] for the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), a well-recognized monitoring and reporting organization that receives data from thousands of participating corporations. The initial list contained about 550 terms. The size of the list was a problem, as the analysis might have become so detailed as to obscure the main themes. Also, some of the terms did not clearly link to a single sustainability dimension. For example, the word “asset” was linked to both economic and social dimensions. Another issue was that some of the terms in the list were phrases or compound words,

e.g., “human capital.” This is a problem with content analysis, especially when the unit of analysis is one-part to three-part words. The problem with this difference in the length of the terms was that it makes comparisons between the frequencies of terms with different numbers of words difficult. To solve this problem, the unit of analysis was limited to single words. This makes between-term comparisons possible and makes the analysis more objective and more accurate, since many computer software applications have difficulty conducting content analysis on multiple words.

Another issue was that some terms did not clearly express or explain a specific dimension of sustainability (environmental, economic, and social). Consequently, the list was reduced to 113 words that were unambiguous and clearly linked to one and only dimension of sustainability. Another problem in counting distinct words is that some of the words have different formats, therefore, the software considers them as different words and counts them separately. To solve this problem, a stemming process was implemented. In the stemming process the different formats of a word are converted to the most simple and basic form of the word. For example, the stem for the words “advertise,” “advertising,” “advertisement,” “advertiser,” and “advertised” is the term “advertis.” This enables all these words to be placed in the same category. To conduct this stemming process the stemming algorithm developed by Porter [

17] was used.

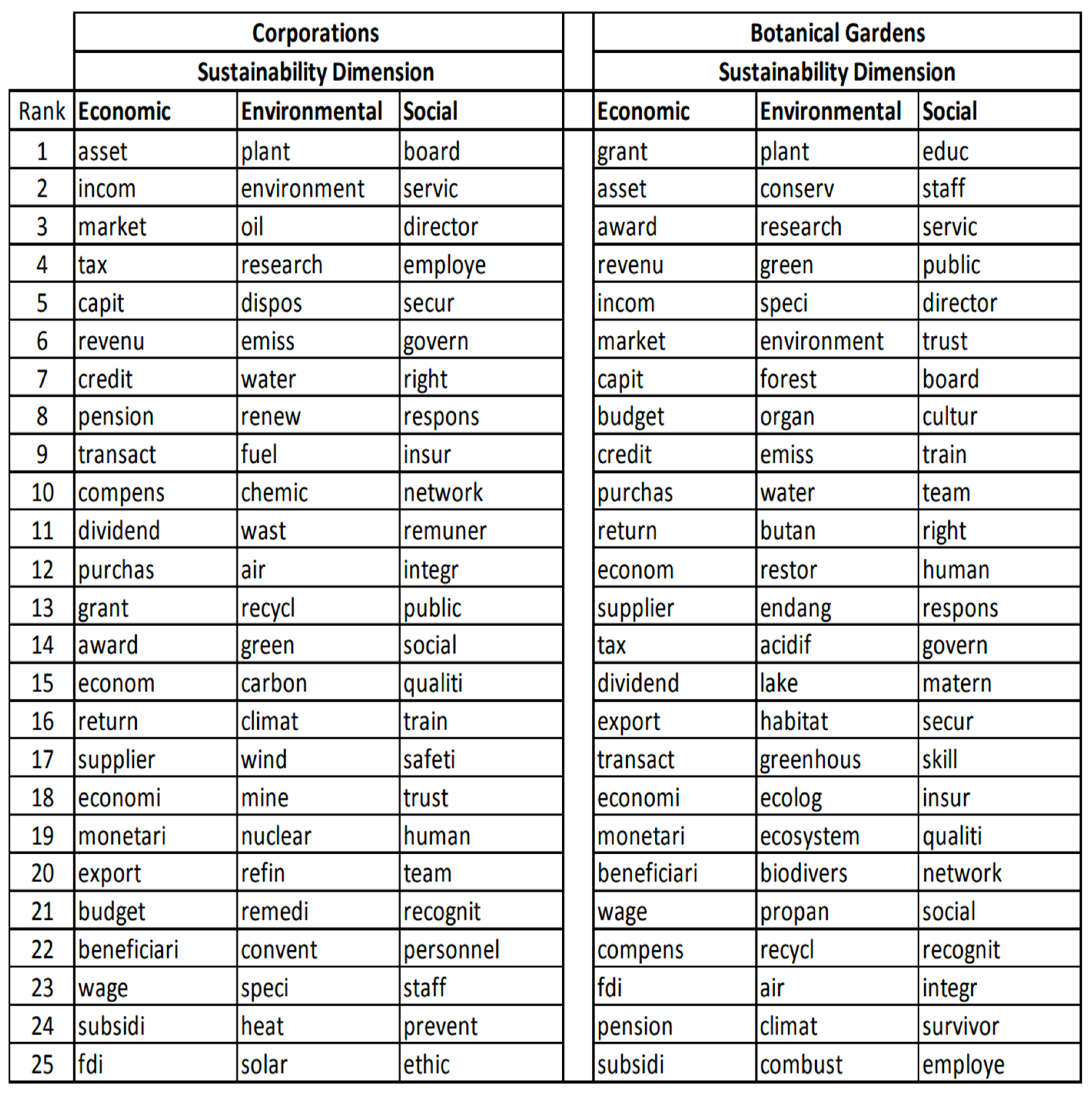

Table 1 shows the word stems resulting from these adaptations and used in this analysis.

Many online portals are based on this algorithm for word stemming. This analysis used the online portal (

http://www.textprocessing.com) which uses Python programing language, one of the advanced and very efficient programing languages. After identifying the stems of the words, the software (Atlas.ti) was used to count the frequency of the stems used in the annual reports. This process was performed for botanical gardens and the US, European, and Asian corporations separately. Afjei has previously used this method for a similar content analysis of annual reports [

18].

3. Results

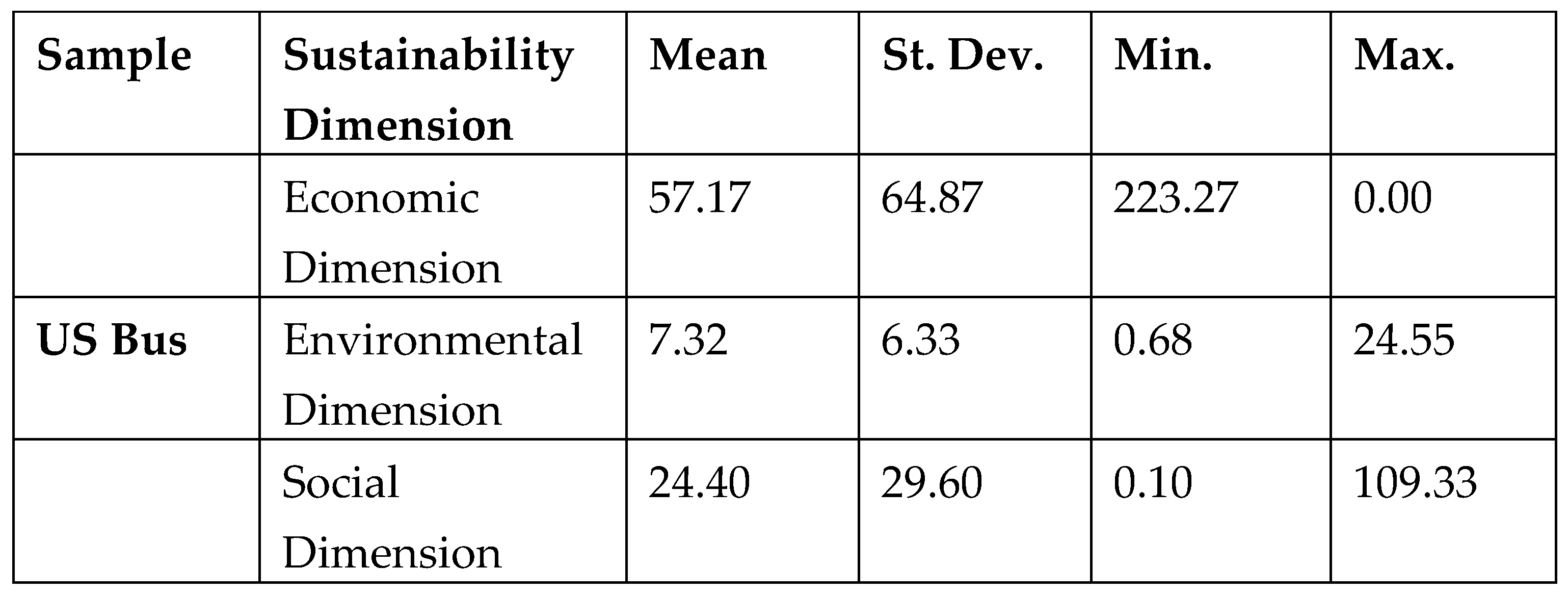

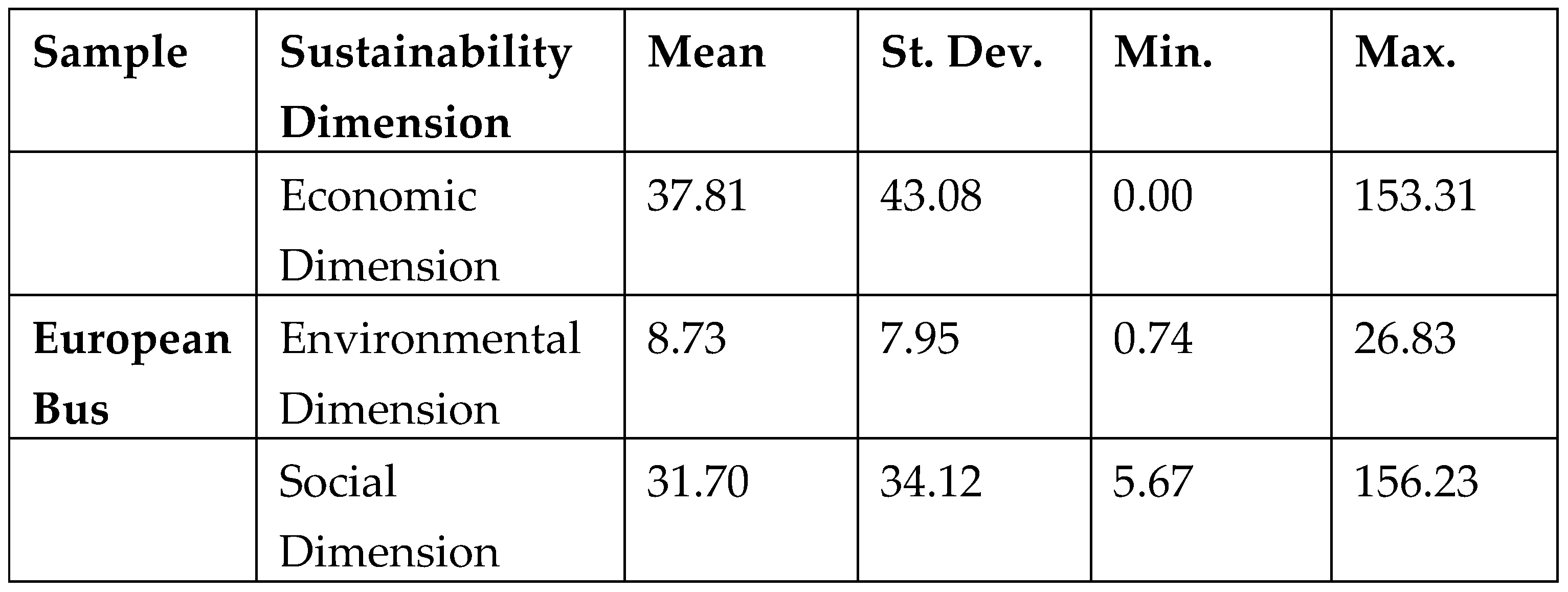

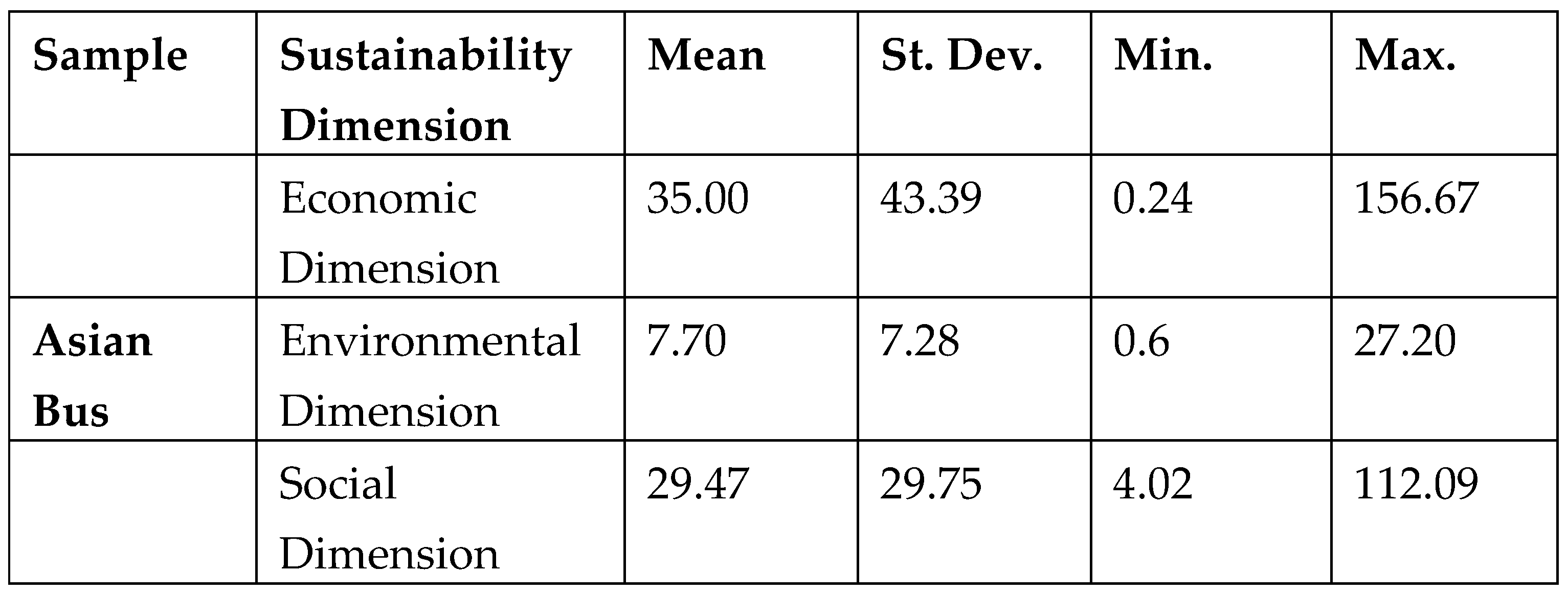

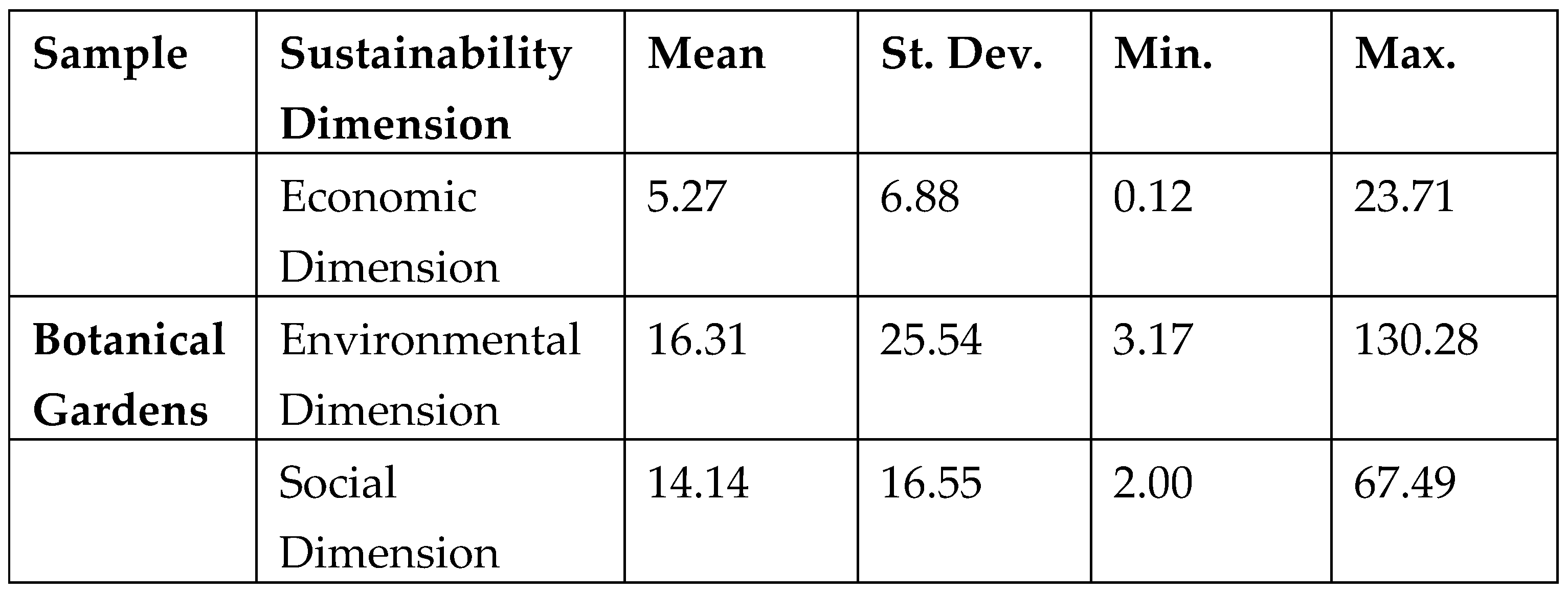

Descriptive statistics for the three dimensions of sustainability (economic, environmental, and social) for US, European, and Asian businesses and for botanical gardens are displayed in

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5. First,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 show that US, European, and Asian businesses all stress the economic dimension over the social and environmental dimensions, and botanical gardens stress the environmental dimension over the social and economic dimensions. This is not surprising.

However, US businesses stress the economic dimension far more than European and Asian businesses. The economic and social dimensions are given similar importance in European and Asian businesses and the environmental and social dimensions are given similar importance in botanical gardens. The overall impression is that US businesses are underemphasizing the social aspect of sustainability.

Table 5 shows that botanical gardens give nearly equal emphasis to the social and environmental aspects of sustainability, reflecting the priorities of their most internal stakeholders (scientists and community participants). Botanical gardens recognize their dual purpose and manage accordingly. Yet botanical gardens have demonstrated impressive performance over prolonged periods of time. In fact, it is hard to identify any botanical gardens that have failed due to shortcomings in any aspect of sustainability. Natural disasters and crises such as wars and revolutions affect all institutions of society, including botanical gardens, but the survival of botanical gardens through long periods of time is impressive. As a category, they have high institutional legitimacy despite, or perhaps because of, their divergent stakeholders.

These results begin to answer our basic question of what businesses can learn from botanical gardens. They demonstrate that it is possible to manage an organization with multiple goals including sustainability. In fact, it suggests that the long-term economic viability of business may depend on balancing stakeholder interests represented in the multiple dimensions of sustainability along with the traditional goal of performance. For US business, these results strongly suggest that the social dimension should receive more attention.

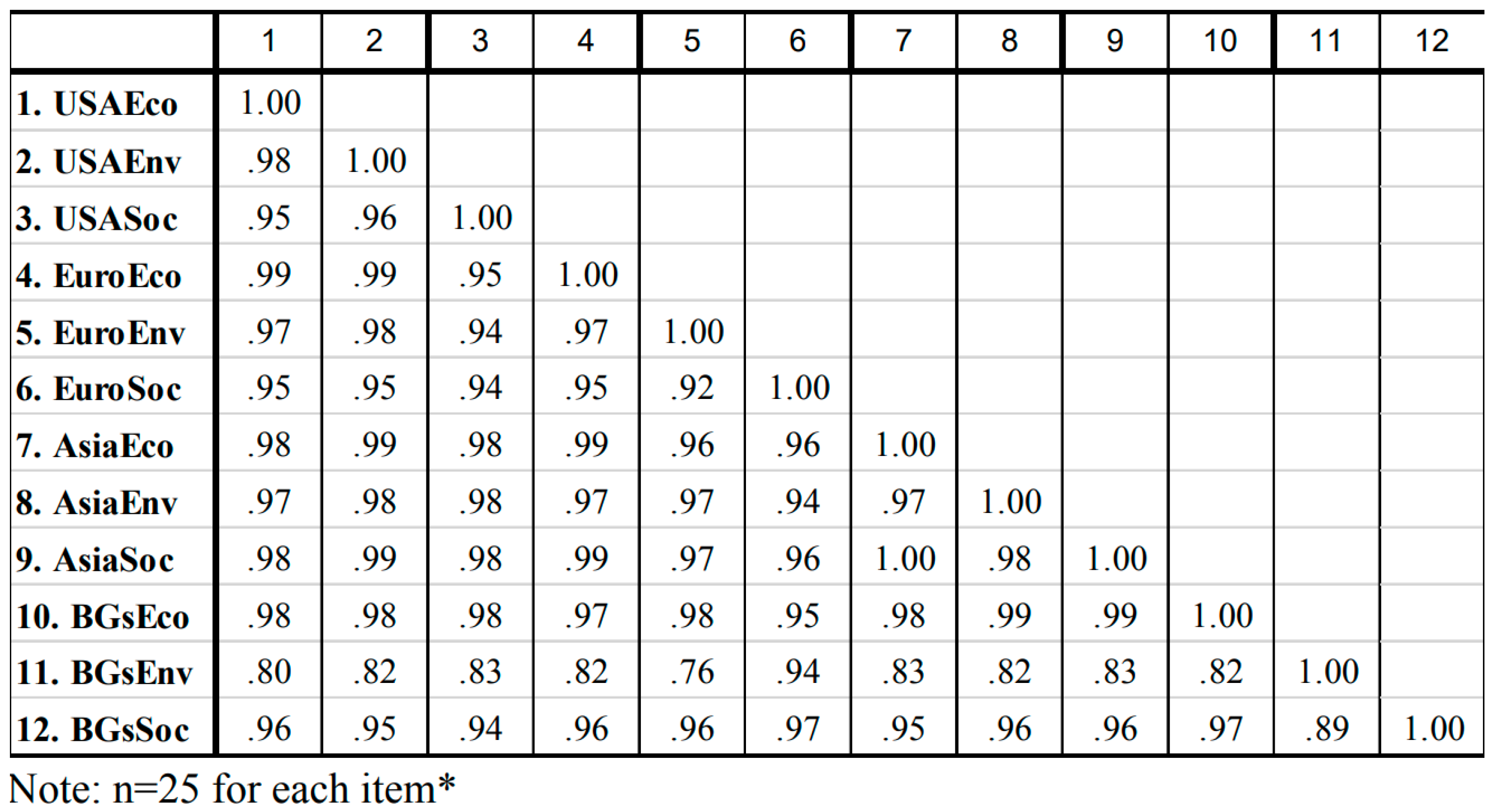

Table 6 reinforces the observations made in

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5. Botanical gardens differ from businesses in the emphasis they give the environmental aspects of sustainability. Businesses emphasize the economic dimension. However, closer examination of the data is required to show the significance of these findings.

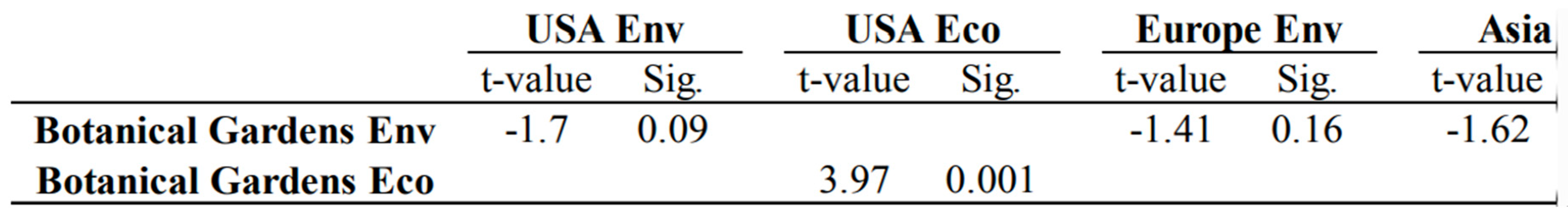

Application of the t-test in

Table 7 shows the significance of the differences between each set of businesses and botanical gardens in the economic dimension. US businesses emphasize the economic dimension of sustainability significantly more than the environmental dimension. However, this difference rises to the level of significance only with US businesses, not with European or Asian businesses.

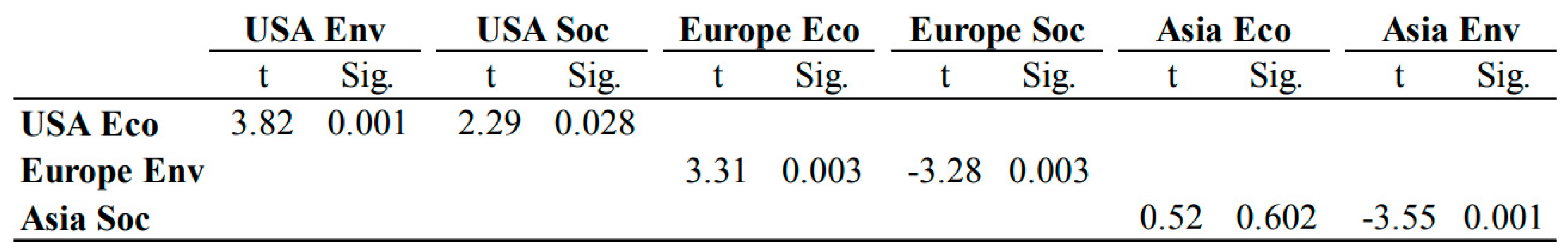

Table 8 tests the significance of differences observed between US, European, and Asian businesses and botanical gardens. US and European businesses emphasize the economic dimension significantly more than the social dimension and the environmental dimension.

In contrast, Asian businesses show a significant difference between the environmental dimension and the social dimension, but no significant difference between the social and the economic dimensions. European businesses follow a similar pattern. Both European and Asian businesses emphasize the environmental dimension and the social dimension of sustainability at a similar level significantly less than the economic dimension.

4. Discussion

4.1. What Can Business Learn from Botanical Gardens?

The object of this study was to see what business can learn from botanical gardens. First, balancing the different elements of sustainability may provide value to business in terms of legitimacy and public support that should be considered in addition to the traditional emphasis on performance. Second, US business might take note of the more balanced attention given to all three dimensions of sustainability by Asian and European businesses. Third, botanical gardens provide a good example of how sustainability can be implemented as a meaningful goal for business. This probably requires identifying specific goals and personnel responsible for achieving those goals. Finally, US business may need to focus more on the social aspects of sustainability, as do their counterparts in Europe and Asia.

4.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

One limitation is that this study focused on businesses already identified as performing well on sustainability. Much remains to be done to find out whether low-performing businesses are adopting sustainability practices in a way that emulates other businesses in their geographic area (Europe, Asia, or the US), or whether global norms are evolving, pushing forward a tendency toward isomorphism. If the more low-sustainability businesses in different areas of the world show differences diminishing over time, it could represent genuine efforts toward higher sustainability, or it could show the spread of greenwashing, whereby businesses are learning how to create an image of being oriented toward sustainability goals that does not correspond with actual commitment or achievement. Sometimes consulting firms enable companies to “game the system” of reporting on sustainability achievements.

Another limitation is that sustainability is undergoing challenges from political forces, so we could see a decline in its emphasis over time. There could be an increase in performance goals as compared to sustainability goals. In some places, even the terms “climate change” and “sustainability” are being eliminated from government policies and educational programs [

19].

One detail of this study that requires explanation is the restriction of European businesses to Continental Europe, thereby excluding some important European countries, e.g., Great Britain. This was done because the Anglo tradition and British business practices may resemble US businesses more than they resemble Continental European businesses. The reasons for this are historical and legal and would be an interesting topic for further research.

5. Conclusions

For practitioners in botanical gardens, this study demonstrates the efficacy of their traditionally balanced approach to the environmental and social aspects of sustainability. Economic performance follows the perceived legitimacy of both scientists and local communities. Botanical gardens have been successful in fulfilling expectations in these dimensions. Botanical gardens may come under more strain in the future. In urban areas large plots of land devoted to the environmental dimension may be threatened by the pressure to provide more housing and commercial space. Developers have already encroached upon many golf courses In the US and have attempted to turn some state parks into commercial entertainment centers, complete with hotels, retail space, and other ventures such as golf courses, pickleball courts, tennis courts, and similar spaces. The city of Miami, Florida has recently turned over its largest municipal park for the development of a soccer stadium [

20]. Botanical gardens might make a tempting target.

For businesses, developing the social and environmental aspects of sustainability requires more than just compliance with government requirements or following a pre-determined format for reporting such as a consulting firm might provide. The following actions are recommended:

Scientific and management personnel devoted to sustainability efforts should be identified and possibly insulated from stakeholders representing the economic dimension.

Budgeting, measurement, monitoring, and reporting sustainability goals should be integrated into regular decision-making of managers.

Awareness of emerging concerns of environmental stakeholders is essential. High-level personnel should be specifically charged to monitor and engage with external stakeholders whose importance may not have been of much interest to the business in the past or may even have been perceived as a nuisance.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest.

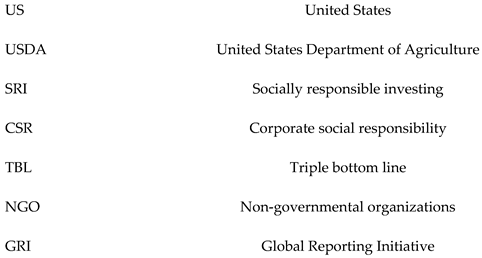

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Appendix A. List of US, European, and Asian Businesses

Appendix B. List of Botanical Gardens

References

- How Many Botanical Gardens are in United States? - Poidata.io Available online. (Accessed on 08 Mar 2025).

- Hill, A.W. The history and functions of botanic gardens. In ANN MO BOT GAR, 1915 2, 185-240. on (Accessed on 2 Feb 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fadelelseed, S.; Xu, D.; Li, L.; Tran, D.; Chen, X.; Alwah, A.; Bai, H.; Farah, Z. Regenerating and Developing a National Botanical Garden (NBG) in Khartoum, Sudan: Effect on Urban Landscape and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability-Basel 2024,16, 7863. [CrossRef]

- DeMaio, A. Planting the Seeds of Empire: Botanical Gardens in the United States, 1800-1860, Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA USA, 2020. https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37366001.

- Krishnan, S.; Novy, A. The role of botanic gardens in the twenty-first century. CABI Rev, 2017, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.1079/PAVSNNR201611023.

- Brundtland, G. H. Our common future—Call for action. Environmental conservation, 1987,14, pp. 291-294. doi: . [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England. 2015; [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J., & Rowlands, I. H. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Alternatives Journal, 25, 1999; p. 42. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/cannibals-with-forks-triple-bottom-line-21st/docview/218750101/se-2 (Accessed on 27 Feb, 2025).

- Elkington, John. “Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business” (New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada, 1997.

- Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1952.

- Holsti, O.R. Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, MA 1969.

- Mayring, P. Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical background and procedures. Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education: Examples of methodology and methods. Available at Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Background and Procedures | SpringerLink, 2015. Accessed Feb. 10, 2025.

- Hsieh, H.F; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. QUAL HEALTH RES, 15, 2005. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Krippendorf, K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, 2012. doi: . [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Allyn & Bacon: Needham Heights, MA: Berg, 1989. https://thuvienso.hoasen.edu.vn/handle/123456789/11108.

- Dickinson, S.J.; Gill, D.L.; Purushothaman, M.; Scharl, A. “A web analysis of sustainability reporting: an oil and gas perspective", Journal of Website Promotion, 3, 2008. doi.org/10.1080/15533610802077255.( Accessed on 27 Feb 2025.).

- Porter, M.F. (1980), "An algorithm for suffix stripping", Program: electronic library and information systems, 14, 1980. [CrossRef]

- Afjei, Sayed MR., "A Content Analysis of Sustainability Dimensions in Annual Reports" 2015. FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1926. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1926.

- Inskeep, S. & Green, A. Broadcast on “Morning Edition”, May 17, 2024. Viewed at https://www.npr.org/2024/05/17/1252012825 on Feb. 27, 2025.

- NBC News. “A Transformational Moment: Miami Commissioners Pass Inter Miami Stadium Deal.” Broadcast NBC Miami April 28, 2022. ‘A Transformational Moment’: Miami Commissioners Pass Inter Miami Stadium Deal – NBC 6 South Florida “. (Accessed 24 Feb 2025).

Table 1.

Word Stems for Analysis of Businesses and Botanical Gardens.

Table 1.

Word Stems for Analysis of Businesses and Botanical Gardens.

Table 2.

Sustainability Measures of US Businesses.

Table 2.

Sustainability Measures of US Businesses.

Table 3.

Sustainability Measures of European Businesses.

Table 3.

Sustainability Measures of European Businesses.

Table 4.

Sustainability Measures of Asian Businesses.

Table 4.

Sustainability Measures of Asian Businesses.

Table 5.

Sustainability Measures of Botanical Gardens.

Table 5.

Sustainability Measures of Botanical Gardens.

Table 6.

Intercorrelations Matrix*.

Table 6.

Intercorrelations Matrix*.

Table 7.

T-tests between environmental dimensions of botanical gardens and US, European, and Asian businesses.

Table 7.

T-tests between environmental dimensions of botanical gardens and US, European, and Asian businesses.

Table 8.

T-tests between social and economic dimensions of botanical gardens and US, European, and Asian businesses.

Table 8.

T-tests between social and economic dimensions of botanical gardens and US, European, and Asian businesses.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).