Introduction

Microbes are present all around us, in the air, water, soil, and even as residents of our body. The. human body has trillions of microbes, outnumbering its own cells by 10 to 1. This includes a diverse array of organisms such as bacteria, fungi, viruses and other tiny organisms [

1]. All these microbes living in the body create a unique and dynamic habitat referred to as the “Human Micro-biome. Human micro-biome can be defined as the collection or groups of microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, viruses and protozoa that live in a living system and their genetic material. Each individual possesses a unique micro-biome which is influenced by a number of factors such as their lifestyle, genetics, disease history, etc.

Microorganisms are one of the earliest life forms on Earth and have always been a topic of interest since centuries in the field of science. The first evidence of a micro-biome in the human body emerged in the mid-1800s by an Austrian paediatrician, Theoder Escherich. He observed and compared the activity of

Escherichia coli in the intestines of healthy children and in children suffering from diarrhoea in the year 1886.Successive years witnessed more and more discoveries of microbes in human body.

Veillonella parvula was isolated from the oral cavity, the upper respiratory tract, the digestive tract, and the urinary tract in 1898.

Bifidobacter spp were also found in faeces of infants by Tissier. During the course of 20th century, many species of microbes were isolated from human body. In 2001, the term ‘micro-biome’ was coined by Lederberg and McCray [

2].

The characterization and classification of the residents of a micro-biome can be performed in several ways. When considering a kingdom-based classification, the microbiome can be divided into a bacteriome, archaeaome, virome, and mycobiome for bacteria, archaea, viruses and fungi respectively. Another classification based on their impact on human health classifies the microbiota into three broad categories:

Pathogenic Organisms (e.g., Escherichia coli, Corynebacterium diptheriae, Candida albicans)

Opportunistic Organisms (e.g., E.coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Staphyloccus aureus)

Benign Organisms (e.g., Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacter spp)

Benign organisms include those which possess a mutualistic relationship with humans, both of them benefit each other. The term also includes microbes that co-exist with the body without causing it harm, i.e., commensals. Some opportunistic microbes also exist in similar conditions in the body. These opportunistic microbes are usually a commensal but they can become pathogenic in certain conditions like immunosuppression due to diseases like AIDS (viral disease) autoimmune diseases like Type 1 diabetes and other factors. Bacterial opportunistic colonization is of serious concern as it contributes to antimicrobial resistance.

Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia are the most common opportunistic bacteria known. Other than these, fungi like

Candida albicans (causes oral thrush and other infections), protozoa like

Blastocystis and viruses like

Rhinovirus are opportunistic pathogens [

3]. They are usually non-pathogenic. However, when their population reaches certain thresholds, the metabolites they secrete such as trimethylamine, indole sulphate, trimethylamine-N-oxide, etc. can have detrimental effects on their human hosts.A healthy human body includes a balanced microbiome, where the pathogenic and opportunistic agents are supressed and beneficial agents thrive. This has several benefits to the body overall. For example, the competition for space and resources inhibits the colonization of pathogens [

4]. The microbiota also assists the body in the production and regulation of several metabolites such as vitamins, lipids and short chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Furthermore, it plays a crucial role in the regulation and maturation of host immunity [

5].

- ➢

HUMAN MICRO-BIOTA

The human body contains various organ systems and organs that function with a complex and interconnected physiology. Each of them provides microorganisms with a distinct physical, chemical and biological environment to inhabit, thus resulting in various regions of the body with unique micro-flora and -fauna. The major regions of the body with a vast and diverse micro-biota include the following:

The skin, the largest organ as well as the one most exposed to the outer environment carries the most diverse groups of microbes. Bacterial colonizers are Staphylococcus epidermidis and other coagulase negative species of Staphylococcus. Bacteria also protect the skin, Bacillus subtilis produce bacitracin which helps to eliminate other microbes, the reason being it is used in antibiotics. Other species are Propionibacterium, Brevibacterium and Corynebacterium. Fungal species of Malassezia are prevalent in sebaceous glands.

The nasal cavity is also home to a lot of microbial species but it is still an unexplored area of research. Different parts of the nasal cavity have different kinds of microbes. Studies suggest that gram negative bacteria are evidently absent in the nasal passages. Few of the species found in nasal cavities are Corynebacterium, Aureobacterium and Rhodococcus.

Oral micro flora comprises of over than 600 species. They colonize the oral cavity, the teeth, tongue, cheek, lip, gingival sulcus, hard palate and soft palate. A variety of species of microbes are found in the oral cavity namely Actinobacter, Bacteriodetes, Chlymadiae, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, Streptococcus and Tenericutes. Some of these The bacteria show antagonistic properties towards other groups of microbes, for example hydrogen peroxide produced by S.gordonii inhibits the growth of A.naeslundii.

Healthy micro-biota in the

human reproductive tract makes human reproduction successful. The female reproductive tract is inhabited by several microbes which at certain stages of reproduction cycles, gametogenesis and pregnancy and it is present in variable density and composition.

Lactobacillus spp constitute the vaginal tract and fluctuate during menses on the other hand,

Gardneralla vaginalis increases. In male genital tract, the upper genital tract immaculate (germ-free) while the lower genital tract does have microbiota.

Coryneform bacteria are common commensals in the male genital tract [

6].

Microorganisms residing in the digestive tract, collectively referred to as gut micro-biota, are the well-studied due to their strong influence on gut health. Different parts of the gut have unique physicochemical conditions. The stomach is highly acidic due to the secretion of hydrochloric acid. In contrast, the intestines have a higher alkaline pH due to bile juices secreted from the pancreas. The surfactant activity of bile salts also prevents inhibits microbial growth. Gut microbiota have specially adapted to these conditions along with coordinating with the immune system to co-exist with the host.

- ➢

GUT MICROBIOTA:

The gut micro-biota can be defined as the groups or collection of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes in the human gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) possessing mutualistic beneficial relationship with human host. They perform diverse functions in the body. There are 10~ more bacterial cell than the human cells and 100 times more micro genome than human genome [

7].

The gut is colonised by microbes after birth however some research shows a few microbes have been found in womb tissues. At the age of 3, the gut starts to resemble the gut micro-biota of an adult. In babies being breastfed, the first microbial species to appear are Bifidobacterium spp. These species are not found in babies who are fed with formulated milk. Different life events increase the diversification of gut micro-biota such as illness, administration of antibiotics, diet and others. With the course of time, microbes like Escherichia coli, lactobacillus spp., Clostridium spp., Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria.

The types of bacteria in infants vary depending upon the type of deliveries. Babies delivered through vaginal delivery have faecal micro-biota resembling to their mothers’. Babies delivered through C-section usually have a depleted micro-biota and the colonisation by

Bacteroides genus is delayed and colonised by

Clostridium species which is a facultative anaerobe. Breastfed infants have

Bifidobacterium spp infants fed with formulated milk lack this species [

8,

9].

The gut also consists of viruses. Mostly it is colonised by viruses like

Enterovirus, Cardiovirus, Rotavirus, Bocavirus and a number of other viruses. Bacteria eating viruses’ bacteriophages are found in abundance in the gut of a healthy human. They can have function in the regulation of immune response in the host. Future prospects discuss that bacteriophages can be used to tackle the emerging problem of antibiotic resistance [

10,

11].

Fungi also dominate the gut micro-biota.

Candida albicans is the most abundant fungi of the gut though it is an opportunistic pathogen; it serves potential functions in the gut. Other fungi of gut are

Candida glabrata, Candida parapsitosis, Saccharomyces spp. Rhodutorula mucilaginosa, etc. they are shown to influence immune response by manipulating inflammatory responses, they either reducing it or by encouraging it [

12].

Blastocystis spp is the most widespread protozoa present in the human gut which were primarily characterized as pathogenic protozoa but later on they were established as commensals.

Dientamoeba fragilis, Entamoeba spp (non-infectious) are common protozoa which can be referred to a component of gut micro-biota. However, it should be noted that only a few species of

Entamoeba like E. dispar are beneficial for the host while most of the other species are potent of causing serious GI tract infection like

E. hystolytica which causes amoebiasis [

13].

All these microbes have different roles in the gut of humans. They have a multiplicity of functions ranging from providing immunity to the host, producing metabolites that aid us in maintaining wellbeing of health, inhibition of colonisation by foreign microbes, and so much more.

- ➢

ROLE OF GUT MICROBIOTA-

A) IMMUNITY:

Gut micro-biota helps the human body in multiple ways including aiding in digestion, nutrient production like vitamins anti-microbial agents, inhibiting foreign pathogen invasion, detoxification and providing immunity to the host. Of all the important roles that are played by gut micro-biota,

providing immunity to the host and maintaining innate immune-homeostasis and also have a profound role in autoimmunity is one of the very major functions performed by human micro-biota [

14]. Innate immune-homeostasis is the regulation of innate immune response and helps the body to prevent over-expression and also the deficiency of immune responses.

They have immense contribution in developing innate immunity and adaptive immunity. In a recent research, colonization by

Escherichia coli in the gut of germ free models resulted into the recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs) to the intestine [

15]. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) produced by the micro-biota has been shown to stimulate DCs that express CD70 on their surface which in turn induce the differentiation and maturation of Th17 cells. This ATP activates a distinct class of immune cells which are present in the intestinal lamina propia and are called as CD70 (high) CD11c (low) cells which in turn leads to the differentiation of Th cells [

16].

The gut micro-biota also has functions in

immunomodulation, and has a systemic mechanism for doing so. They act as a source of peptidoglycan which is an important component of innate immunity and enhance killing of pathogenic bacteria like

Streptococcus pnuemoniae and

Staphylococcus aureus by concrete mechanisms [

17]. the gut micro-biota also helps in the development of CD4+T cells both inside and outside the intestine.

B) METABOLITES PRODUCTION:

The process of digestion is a very efficient and complex process but a few compounds such as fibres escape the action of strong digestive enzymes produced by the body. These compounds are fermented by the multitude of enzymes produced by the gut micro-biota and they also produce a variety of metabolites which have wide spectrum of bioactivities. These metabolites can be grouped in the following categories: [

18]

- ❖

Metabolites directly derived from diet such as indole and its derivatives and short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

- ❖

Metabolites produced by the host but are modified by the micro-biota including secondary bile acids

- ❖

Metabolites that are produced de novo (changes in DNA sequence that occur for the first time) such as polysaccharide A.

These metabolites serve regulate the composition and function of gut micro-biota. Diet-derived metabolites, especially SCFAs, modulate the functions and constitutions of microbes in the GI tract. For example, indole and its derivates regulate biofilm production, antibiotic resistance, virulence and sporulation of gut micro-biota [

19] these metabolites are also toxic to a restricted range of bacterial species [

20]. Some antibiotics are also produced including antibiotics synthesized by ribosomes, post-transnationally modified peptides like bacteriocins, lantibiotics and microcins [

21].

Bifidobacterium species synthesize nutrients like Vitamin K and B groups via de novo processes [

22]. Gut micro-biota produces essential amino acids like leucine, tryptophan and valine which support the process of protein synthesis and act as precursors for metabolites that affect mammalian physiology. They metabolise dietary supplements including mucins xenobiotic chemicals, carbohydrates, fats, lipids and proteins [

23].

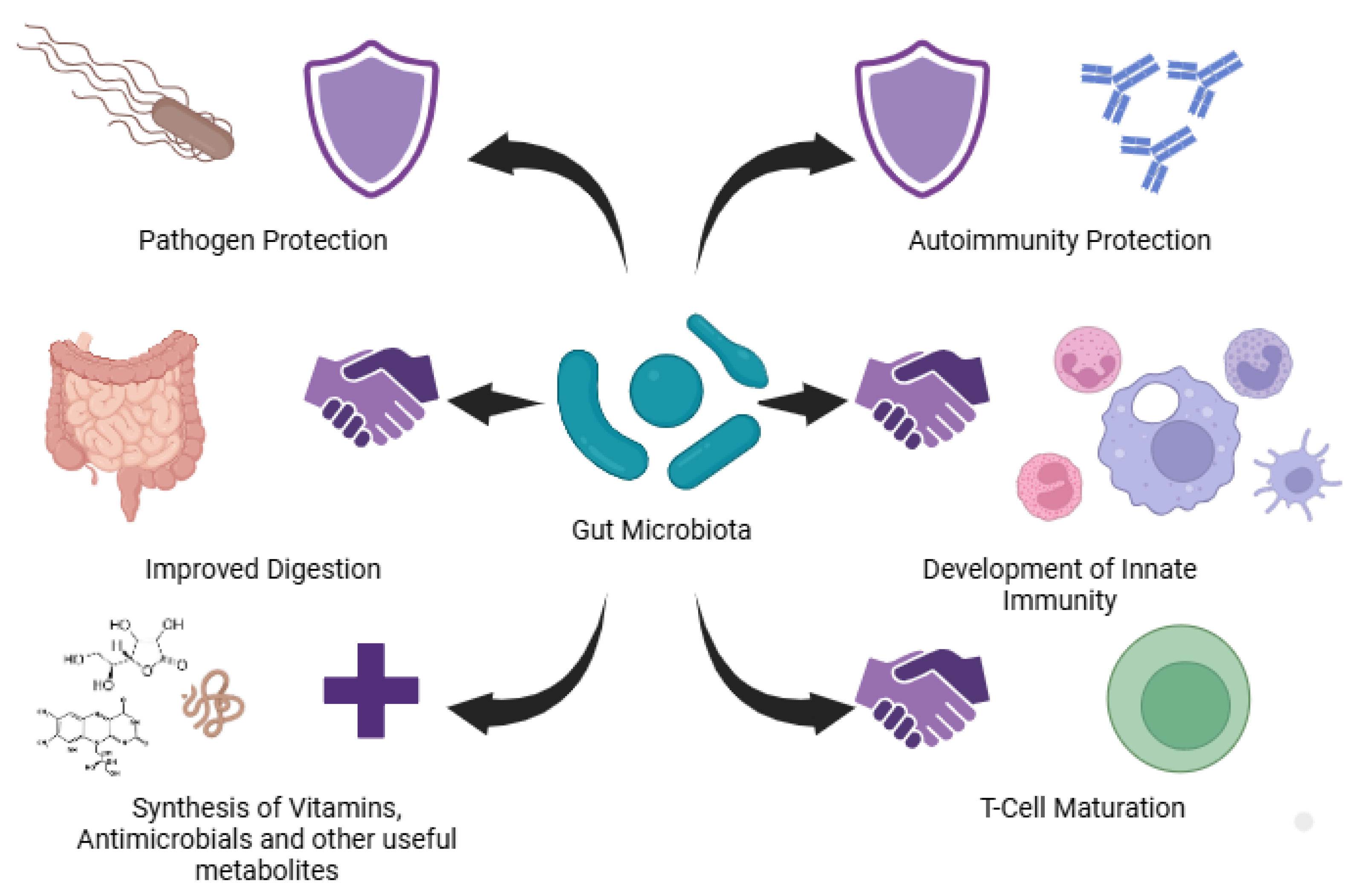

Figure 1.

Role of gut microbiota in providing immunity to the host, in pathogen proetction, in improving digestion, in development of innate immunity, synthesis of vitamins, antinmicrobials and metabolites.

Figure 1.

Role of gut microbiota in providing immunity to the host, in pathogen proetction, in improving digestion, in development of innate immunity, synthesis of vitamins, antinmicrobials and metabolites.

C) OTHER IMPORTANT FUNCTIONS:

SCFAs exhibit anti-inflammatory properties in the gut. They present many benefits to the host like antagonistic activity, mucus adherence, antibiotic susceptibility and toxin gene detection. Strains of

Escherichia coli have produce these SFAs without showing any haemolysis up to 70% [

24]. they produce propionic acid, butyric acid, acetic acid, caproic acid and valeric acids.

E.coli is a promising probiotic.

Lactobacilli improve the gut health and regulate host immune systems. They maintain a balance in the gut micro-biota and also enhance the gut metabolic capacity. They improve growth performance. They also protect the host by preventing gastrointestinal infections.

Lactobacilli collaborate with the Gut associated lymphoid tissues (GALT) which have an important function in immune response regulation and B-cell development. This interaction leads to the enhancement of mucosal immune response. It also influences the roles of dendritic cells, macrophages, B and T cells. The cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β are released with the stimulation of GALT and thus helps to reduce inflammation and ward off excessive immune response. This machinery helps the host to defend pathogen interference [

25,

26].

Species of

Bifidobacterium are dominant in the gut and are transmitted vertically to the host via breast milk. They exhibit promising health promoting benefits to the host. They act as fermentable substrates for the gut and modulate specific processes. They modulate the composition and metabolic activity of gut micro-biota. They also aid in providing protection against pathogenic invasions. They safeguard the integrity of intestinal barriers by reducing apoptotic epithelial cell shedding. They regulate cell apoptosis and cell cycle and ultimately reveal anti-tumour activities [

27].

Gut commensals protects the host in a multitude of ways. They act as metabolisers, as fermenters, provide immunity and maintain immune-homeostasis, and provide protection against many gastrointestinal infections like

Klebsiella pneumonia [

28].

- ➢

PROBIOTICS AND PREBIOTICS:

The GI tract is heavily colonised by microbes which share symbiotic and mutualistic relationships with the host. They benefit the host in numerous ways. Particularly, Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria are very beneficial to the host. To enhance the gut microbes and their health, Probiotics and prebiotics are new dietary products that enrich the gut micro-biota and ultimately provide benefits to the host such as enhanced immunity, controlled appetite, better nutrient absorption, blood sugar control, and mental health.

- ❖

Probiotics:

Probiotics are viable or feasible dietary products and supplements that contain microbes or microbial compounds which work in the intestinal tract of human and benefit them in number of ways. They are used in fermented dairy products like curd, vegetable products like pickles and kimchee as well as many other food items [

29]. A probiotic can also be defined as “a live microbial agent i.e., bacteria that is beneficial for health” [

30]. Probiotics are usually taken in the form of fermented dairy products, but can also be found in fermented vegetables like kimchee and pickles and meat like pepperoni, salami, etc. [

31]. Modulation by probiotics has been known to prevent disease for e.g., Celiac disease (gluten sensitivity), diarrhoea, irritable bowel, and other GI tract diseases and infections.

Bifidobacteria and

Lactobacilli are the main bacterial species used in the probiotics [

32]. Increased amount of these microbes induce a protection barrier against invasion by pathogens. Probiotics secrete important metabolites such as lactate, acetate, etc. via metabolic pathways. They also produce SCFAs that exhibit anti-microbial activity against food pathogens. When the gut is heavily colonised by probiotics there is an establishment of competition for nutrient and shelter between the commensals and invading pathogen which inhibits their colonisation. The probiotics establish themselves as the commensals. They produce anti-microbial compounds like bacteriocins, cationic peptides which kill the foreign pathogen by creating pores in their body which results into the leakage of cytosolic components inside the cell and results in the necrosis of bacterial species including

Salmonella, Listeria, Clostridium, etc. They also secrete hydrogen peroxide, siderophores and bio surfactants that inhibit foreign microbial colonization and growth [

33,

34].

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are the most commonly used probiotics. Of these, the species of Lactococcus are the most widely used members of LAB. These gram-positive cocci have been used as probiotics in the form of yoghurt, cheese, and pickles since centuries. They make an outstanding choice for probiotics due to the absence of lipopolysaccharides and lack of release of protease enzyme. They secrete recombinant proteins which do not get trapped in the periplasm as they are gram positive cocii which makes them an excellent vehicle for food-grade production of proteins and enzymes. Lactococcus lactis is the most widely used species of LAB that is used for cytokine delivery and is a transient colonizer in the gut.

The gram-negative bacterial probiotics include

Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN). This strain is administered to neonates to protect them from invasion by multi-drug-resistant pathogens. Mutaflor, used for treatment of infectious diarrheal diseases contains EcN. It is highly protective against

Listeria monocytogenes, Candida albicans, Salmonella enterica, and also known to attenuate (down-regulate) inflammation [

35].

- ❖

Prebiotics:

Prebiotics are non-viable and fermented products that serve as a feed for the gut micro-biota. They are selectively degraded by the microbes in the colon [

36,

37].

They function to enhance and stimulate the activity of gut micro flora. A key trait of a prebiotic is its selectivity in promoting the growth of specific probiotic species such as

Bifidobacteria and

Lactobacillus. Prebiotic feeds include carbohydrates such as fructans and galactans that are not degraded by human digestive enzymes but are fermented by anaerobic bacteria in the large intestine [

38]. Since prebiotics are indigestible by the body they selectively influence and enhance the growth of gut micro-biota.

Prebiotics are taken to suppress colonization by foreign pathogens. When prebiotics are fermented in the large intestine they yield SCFAs. Through selective enhancement of

Bifidobacteria and

Lactobacilli, they stimulate gas production too. They also show laxative effects (easier bowel movements by manipulation of digestive system). Prebiotics have therapeutic potential for treating inflammatory diseases including inflammatory bowel syndrome and even colon cancer [

39].

Prebiotics are taken to enhance the function of probiotics in supressing the colonization of foreign pathogens. When fermented, they degrade into antimicrobial SCFAs. They show anti-inflammatory effects, which has utility in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and colon cancer. Furthermore, they also aid in digestion by having laxative properties. Prebiotic use has also been shown to lead to bloating, caused by excess gas production by Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria.

TYPES OF PREBIOTICS:

Prebiotics are classified mainly on the selective carbon source provided to the prebiotic bacteria, which comprises complex poly- and oligosaccharides that are microbially degradable by probiotics but indigestible by humans. The three major prebiotic groups include:

1) Fructans-

These include oligo-fructose and inulin. They are of linear structure having β-linkage and have a terminal glucose unit. They majorly stimulate the growth of LAB. They can also directly or indirectly stimulate the growth of other bacterial species in the gut.

2) Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS)-

They promote Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli significantly. They also stimulate other bacteria such as Enterobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes, albeit in a lesser capacity as compared to Bifidobacteria. GOS are a product of lactose extension. Some are also derived from lactulose, an isomer of lactose. GOS are further classified into two categories

- a)

GOS with excessive galactose (found in milk of mammals like marsupials)

- b)

GOS manufactured through enzymatic trans-glycosylation from lactose.

3) Starch and glucose-derived oligosaccharides-

Resistant starch is a glucose polysaccharide that strongly resists upper gut digestion. Upon bacterial fermentation, it produces high amounts of butyrate which promotes healthy gut microbiota. Polydextrose is a similar glucose-derived oligosaccharide composed of glucan and glycosidic linkages. Both of these stimulate the growth of

Bifidobacteria. Resistant starch also shows high incorporation in

Firmicutes species [

40].

Table 1.

Major Prebiotics produced in the industries and their functions.

Table 1.

Major Prebiotics produced in the industries and their functions.

| INDUSTRIALLY PRODUCED PREBIOTICS |

FUNCTIONS |

| INULIN |

Enhances the growth of Bifidobacteria and aids in calcium absorption |

| FRUCTOOLIGOSACCHARIDES |

Promotes growth of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria

|

| GALACTOOLIGOSACCHARIDES |

Maintains immune homeostasis and improves the growth of Bifidobacteria

|

| POLYUNSATURATED FATS (PUFAs): OMEGA-3 FATTY ACIDS |

Influence the production of short chain fatty acids leading to growth of a healthy and beneficial gut micro-biota |

- ➢

CONCLUSION:

Human microbiota has significant benefits for the host. The GI tract is the most densely populated part of the body by the microbiota. The gut microbiota influences the human health in a positive way and provides a multitude of benefits. It had significant roles in immune homeostasis, induction of immune response. It helps in the production of important biomolecules like short chain fatty acids, vitamins and anti-microbial agents and serves multiple benefits.

Prebiotics and probiotics have a remarkable influence on human health which makes them a significant part of the decorum. They have alluring benefits and have become a popular dietary intervention due to their roles in providing immunity to human. They help in regulating growth of micro-biota. Administration of prebiotics and probiotics has shown to reduce a number of diseases and infections. The discriminate administration of prebiotics and probiotics could lead to improved gut health, immunity, and safety of populations.