Background

The current global female population standard at 3.9 billion, making up to 50% of the populous. Women generally have a longer life expectancy with the average life-span is 77 years (World Bank Group, 2023). The healthcare demands are complex and growing, with specific health needs throughout the various stages of their lifespan, as such gender-sensitive healthcare approaches are a necessity. This is further evident with increases to global burden of disease (GBD) for women which encompass a range of health challenges for communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs). NCDs such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and chronic respiratory diseases are leading causes of morbidity and mortality among women. Reproductive health issues, including maternal mortality, complications from pregnancy and childbirth, and reproductive cancers like cervical cancer, are also significant concerns. Additionally, mental health disorders, including depression and anxiety, are more prevalent among women compared to men. Infectious diseases, such as , continue to impact women, particularly in low-resource settings (World Health Organization, 2024).

Current evidence shows that many prevalent conditions, such as cardiovascular and endocrine disorders, are often under-researched in women, despite biological differences influencing disease manifestation and treatment. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in women often present differently, yet treatment strategies remain largely based on male-centric research. A study by Maas et al. (2010) stresses the need for sex-specific research in cardiovascular care (Maas et al, 2010). The World Health Organization’s GBD index also underscores the rising incidence of these conditions in women globally (Maas and Appelman, 2010, World Health Organization, 2022, World health Organization, 2021). The significance of incorporating both sex and gender into health research, highlighting their crucial roles in influencing health outcomes and disease risks. Sex refers to biological differences between males, females, and intersex individuals, while gender is a psychosocial construct shaped by societal expectations. Both factors affect the aetiology, manifestation, and treatment responses in diseases, underlining the necessity of studying them in tandem.

Artificial intelligence (AI) could be a potential solution to support the women’s health agenda globally, and can be a transformative tool, offering potential for improved diagnosis, treatment, and personalised care. In this review we define AI as a technology using machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing or predictive analytics to support health challenges specific to women.

In areas such as breast cancer and endometriosis. In the past five years, AI has rapidly advanced in healthcare, improving diagnostics, treatment, and data analysis. Machine learning, a subset of AI, aids in decision-making and understanding disease mechanisms. However, expert oversight is needed due to clinical complexity, and data privacy concerns remain critical when implementing AI in healthcare settings. AI algorithms have been shown to enhance the accuracy of mammography interpretation, often outperforming human radiologists in identifying tumours at early stages. Rodríguez-Ruiz et al. demonstrated AI can detect breast cancer with a higher degree of accuracy compared to radiologists using a clinical trial(Rodriguez-Ruiz et al., 2019). AI holds potential for improving endometriosis diagnosis by identifying patterns in medical imaging and symptom data.

This is an ideal time for a scoping review on AI in women's health because of the rising global emphasis on gender-specific health equity and the rapid advancements in AI technologies. By mapping current applications, challenges, and outcomes, a scoping review can guide future policy, inform procurement decisions for AI-driven tools, and shape clinical care pathways. Such a review will also highlight evidence gaps, enabling the development of more inclusive and effective AI solutions that are responsive to the unique healthcare needs of women, ultimately fostering better health outcomes and supporting equitable resource allocation

Thematic Content Analysis

Gynaecology

AI is continues to be investigated for its potential in personalised medicine within gynaecology. Researchers are exploring how machine learning can help in developing personalised treatment plans based on a patient's unique genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors.

A key area of ongoing research is in the use of AI to improve the management of menstrual disorders and endometriosis. These conditions, which are often underdiagnosed and misunderstood, and could benefit from AI-driven diagnostic tools that analyse patterns using symptom tracking data, genetic markers, and imaging results. Smith and colleagues (2023) explored how AI models could predict the risk of developing endometriosis based on patient data, improving early intervention and personalised treatment. Most endometriosis-AI research is exploring prediction outcomes, build diagnostic models, and enhance research efficiency. Approximately 44.4% of current studies focused on AI’s predictive capabilities, such as forecasting fertility therapy success, while 47.2% investigated diagnostic tools, including differentiation of endometriosis from other pelvic pain disorders. Only 8.33% explored AI’s role in understanding disease pathophysiology. AI techniques such as logistic regression, random forest, and support vector machines were common, with logistic regression most frequently used to develop predictive and diagnostic models (Somigliana et al., 2021). These studies demonstrate AI’s potential but highlight variation in approaches and outcomes still require validation, relevance to all races and ethnicities and availability across healthcare systems. For instance, in managing conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), AI models can recommend tailored treatment strategies by analysing hormonal profiles, insulin resistance levels, and lifestyle data (Zhao et al., 2022).

Robotic surgery is another area where AI is playing a crucial role. Systems like the da Vinci Surgical System have been used in gynaecological procedures such as hysterectomies and myomectomies, allowing for greater precision and reducing recovery times. Systems such as the da Vinci Surgical System assist surgeons by providing real-time, high-resolution 3D visualisations and robot-assisted movements, allowing for minimally invasive procedures in gynaecological surgeries like hysterectomies. It consists of a surgeon's console, robotic arms, and a high-definition 3D camera. The surgeon controls the system from the console, which translates hand movements into precise micro-movements of the robotic instruments. The system provides a magnified, high-resolution 3D view of the surgical site, allowing for enhanced visualisation. Its robotic arms offer a greater range of motion than human hands, enabling more precise manipulation of tissues and instruments. This results in less tissue damage, reduced blood loss, and quicker recovery times and shorter hospital stays for women. Additionally, AI-driven robotics provide consistent, reproducible outcomes, even in challenging cases. However, there are concerns about high costs and the need for extensive surgeon training (Alkatout et al., 2021). Despite these challenges, AI-enhanced robotic surgery continues to revolutionise women’s healthcare by improving patient outcomes and recovery experiences and, as a platform that enhances surgeons' precision during minimally invasive surgeries.

Reproductive Medicine

AI also holds promise in the field of reproductive health, particularly in in vitro fertilisation (IVF). By leveraging AI algorithms, clinics can assess the viability of embryos with greater precision, improving the chances of successful implantation. AI models are also being used to predict patient outcomes and customise treatment plans, reducing the need for repeated IVF cycles, which can be both financially and emotionally taxing (Liu et al., 2021). Another common theme is the use of AI to optimize embryo selection for transfer. AI models, such as decision-tree techniques and deep learning models, analyse embryo parameters to assess their viability and potential for successful implantation. Studies like Bori L et al (2020) and Celine Blank et al (2018) explored how AI systems could evaluate both conventional and novel embryo parameters, helping clinicians select the most viable embryos for transfer. These models reduce subjectivity and improve the consistency of embryo selection. AI is also used to personalize fertility treatments by tailoring approaches to individual patients. Predictive models help guide treatment decisions based on a patient's unique clinical profile, including their response to hormone treatments or previous IVF cycles. This personalization helps optimize treatment protocols, reducing the number of unsuccessful cycles and improving overall pregnancy rates.

A significant focus of AI in reproductive medicine is on improving the prediction of IVF outcomes. AI algorithms, particularly machine learning models and artificial neural networks (ANNs), are used to analyse multiple factors involved in IVF, such as hormone levels, patient medical history, and embryo characteristics. These models help predict the likelihood of successful embryo implantation and clinical pregnancy. Studies like those by Liu R et al (2021) and Wang CW et al (2022) applied machine learning algorithms to large datasets to improve prediction accuracy for embryo transfer outcomes. One of the most impactful uses of AI in IVF is the enhancement of embryo selection processes. Traditionally, embryologists assess embryo quality based on morphology and manual observations, which can introduce subjectivity. AI systems, particularly deep learning models, are now being trained to evaluate embryos more objectively and consistently by analysing features such as morphology, developmental patterns, and time-lapse imaging. AI can predict which embryos have the highest chance of implantation, thereby optimizing embryo selection and increasing the likelihood of a successful pregnancy. For example, AI models like those used in studies by Bori L et al (2020) and Celine Blank et al (2018) rank embryos based on viability and ploidy, providing a more reliable framework for choosing the best embryo. Another growing trend is the use of machine learning algorithms to predict the overall success of IVF cycles. These predictive models analyze vast amounts of data, including patient history, hormone levels, ovarian reserve, embryo development data, and clinical conditions, to estimate the likelihood of successful outcomes such as embryo implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth. AI can evaluate multiple variables simultaneously and provide personalized risk assessments for individual patients. This data-driven approach helps clinicians adjust protocols to increase the chances of success in each cycle. For instance, Liu R et al (2021) applied machine learning algorithms to predict the outcome of embryo transfer, taking into account a range of factors related to patient physiology and previous cycle data.

The integration of AI with time-lapse imaging is revolutionizing how embryologists monitor embryo development. Time-lapse incubators capture images of embryos at regular intervals, and AI algorithms analyse the developmental milestones and kinetic behaviour of the embryo throughout its growth. This approach helps identify the optimal time for transfer and detects subtle patterns in embryo development that may indicate higher implantation potential. AI-driven time-lapse systems reduce the need for manual assessments, improving precision while minimizing the disturbance of embryos during the monitoring process.

AI is also being used to optimize the timing of oocyte retrieval in IVF. Traditionally, clinicians decide on the best time for egg retrieval based on hormone levels and ultrasound imaging. AI can refine this process by predicting the exact timing for egg retrieval that maximizes the number of mature, high-quality eggs, reducing the chances of premature ovulation or suboptimal collection. Studies like those by Wang CW et al (2022) have shown that AI can improve the precision of such critical decisions, enhancing overall IVF success. A promising trend in AI-driven IVF is the development of non-invasive methods to assess embryo viability. Traditional methods like preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) involve biopsies that could potentially harm the embryo. AI models, however, can predict an embryo’s viability using non-invasive data sources such as time-lapse images or culture media metabolites, eliminating the need for invasive testing. This trend is making IVF safer and less stressful for both the embryos and the patients. AI is not only helping in embryo selection but also in assessing the quality of eggs and sperm. Machine learning algorithms can evaluate egg quality based on factors like ovarian reserve and oocyte morphology. Similarly, AI-driven sperm analysis can evaluate sperm motility, morphology, and DNA fragmentation to ensure only the best quality sperm are used in the IVF process. This contributes to higher fertilization rates and better overall outcomes in IVF treatments.

Neural networks have been used in reproductive medicine since the late 1990s, as seen in studies like S.J. Kaufmann et al (1997), which applied neural networks to predict IVF outcomes. While these early studies laid the groundwork for more sophisticated AI applications today, they highlight the long-standing interest in using AI to improve fertility treatments. In summary, AI applications in reproductive medicine primarily focus on enhancing the precision of IVF outcomes, optimizing embryo selection, and personalising fertility treatments, contributing to improved success rates and patient outcomes. AI is also playing a role in cryopreservation, which involves freezing and storing embryos, eggs, or sperm for future use. AI models help determine the best embryos for freezing by analysing their viability and likelihood of surviving the thawing process. AI can also assist in predicting the success rates of IVF using cryopreserved embryos, giving couples more confidence in the process and offering better long-term planning options for those undergoing fertility preservation.

Obstetrics

AI has made significant advancements in maternal health, offering innovative solutions to various pregnancy-related challenges, including early risk detection, personalized care, and continuous monitoring. One of the most impactful areas is the use of AI in predicting preeclampsia, a dangerous condition characterised by high blood pressure that can be life-threatening for both mother and baby. AI algorithms analyse clinical, demographic, and biomarker data to predict a woman’s risk of developing preeclampsia. This early detection allows for preventive interventions and closer monitoring throughout the pregnancy, reducing the likelihood of severe complications. Machine learning algorithms could be trained on data from previous pregnancies can identify subtle patterns that may indicate a woman is at risk for preeclampsia or postpartum haemorrhage—conditions that, if untreated, can lead to maternal death. Early detection enables healthcare providers to take preventive measures, administer appropriate treatments, and plan for delivery in well-equipped medical facilities. This early intervention is crucial for reducing maternal mortality, particularly in settings where access to emergency care is limited. Additionally, AI models are increasingly being used to manage gestational diabetes, another common pregnancy complication. Mobile health (mHealth) applications powered by AI can monitor blood glucose levels in real-time and offer personalised recommendations on diet and lifestyle, helping women manage their condition effectively and reduce the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

AI is also transforming foetal monitoring, particularly during labour. Foetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring is essential to detect distress in the baby, and AI models that analyse cardiotocography (CTG) data—measuring foetal heart rate and uterine contractions—are more accurate and faster than manual interpretation. This can lead to earlier interventions when abnormal patterns are detected, potentially improving birth outcomes. Beyond labour, AI is also used to predict other pregnancy risks, such as preterm birth, miscarriage, and postpartum haemorrhage. For example, AI has been integrated into ultrasound imaging to assess the risk of preterm labour by detecting subtle changes in the cervix that might not be visible to the human eye. The postpartum period is a vulnerable time for women, with a significant portion of maternal deaths occurring after childbirth. AI can be used to improve postpartum monitoring and care, ensuring that complications like postpartum haemorrhage, infections, or deep vein thrombosis are detected and treated early. Wearable devices or mobile apps equipped with AI can monitor a woman’s recovery in the days and weeks following delivery, sending alerts to healthcare providers if her condition deteriorates.

Another area where AI is making an impact is through personalised pregnancy support. AI-powered virtual assistants and chatbots are increasingly being used to provide pregnant women with tailored health advice, symptom tracking, and reminders for antenatal visits or medication. These platforms also monitor symptoms like high blood pressure or swelling and recommend when medical attention is necessary. This personalized, ongoing support is especially valuable in areas with limited access to healthcare providers. Similarly, AI-based imaging tools have been developed to monitor placental health, a key factor in preventing complications such as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preterm birth. AI models can analyse placental images, detecting abnormalities and allowing for early intervention to better manage high-risk pregnancies.

Wearable devices equipped with AI are another exciting development in maternal health. These devices, which include smartwatches and patches, monitor the vital signs of both mother and baby, tracking metrics such as blood pressure, heart rate, sleep patterns, and activity levels. AI analyses this data in real-time to detect potential issues like high blood pressure or irregular foetal heartbeats, enabling timely interventions even in remote areas. Additionally, AI models are being used to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections by providing obstetricians with real-time recommendations based on a woman's medical history, labour progress, and foetal conditions. This helps ensure that caesarean sections are only performed when absolutely necessary, reducing the risk of complications from unnecessary surgeries.

Radiology

Imaging data plays a critical role in gynaecological disease diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring, and AI-enabled image analysis is emerging as a transformative tool in this field. One of the most challenging aspects of imaging data analysis is object recognition. Computer science has made significant advancements in this area, evolving from early achievements in recognising handwritten digits in the 1990s (LeCun et al., 1998) to the development of advanced neural networks. A notable example is the ImageNet project, which provided a massive dataset for researchers to train their algorithms, leading to significant improvements in classification accuracy(Deng et al., 2009). By 2015, Microsoft's ResNet achieved a remarkable error rate of 3.5% on the ImageNet dataset, outperforming the human benchmark of 5.1%(He et al., 2016). Since then, many deep learning (DL) models have surpassed the 5% error rate, demonstrating the effectiveness of neural networks in image pattern recognition.

Computer-Aided Diagnosis (CAD) techniques have become a critical application of artificial intelligence (AI) in medical imaging, particularly in women's health. These systems are designed to assist radiologists and healthcare professionals by analysing medical images, such as ultrasounds, mammograms, MRI scans, and CT scans, to detect abnormalities more quickly and accurately. In women’s health, CAD systems are extensively used for diagnosing conditions such as breast cancer, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, and other gynaecological disorders. The role of CAD is becoming increasingly important as healthcare providers seek to improve early detection rates and provide more accurate diagnoses. One of the primary functions of CAD systems is to process and analyse images using AI algorithms, particularly machine learning and deep learning. These systems can highlight areas of concern in medical images, such as potential tumours, abnormal tissue growth, or structural changes that might not be immediately noticeable to the human eye. After processing the image, the CAD system provides diagnostic suggestions or risk assessments, offering an additional layer of decision support for radiologists or physicians. This makes CAD particularly valuable in conditions where early diagnosis is critical, such as cancer.

CAD plays a crucial role in breast cancer detection, one of the most common cancers affecting women worldwide. CAD systems used in mammography assist radiologists by detecting microcalcifications, masses, or distortions in breast tissue that could indicate cancer. These systems have proven to improve detection rates, providing a second opinion or confirming findings made during manual image review. AI models integrated into CAD systems are now able not only to detect potential cancers but also to predict the aggressiveness of tumours, aiding in personalized treatment planning.

Similarly, CAD is applied in ovarian cancer detection through imaging techniques such as ultrasound or MRI. For example, a specific CAD tool called GyneScan is used to analyse ultrasound images to differentiate between benign and malignant ovarian tumours. Early detection of ovarian cancer is particularly challenging due to its often subtle and non-specific symptoms, but CAD can help improve diagnostic accuracy by identifying tumours earlier in their development. Moreover, CAD tools for ovarian cancer also assist in tracking the progression of the disease, providing valuable insights for treatment and monitoring.

In the case of cervical cancer, CAD is employed to assist with colposcopy and Pap smear analysis. Machine learning models used in these systems classify cervical lesions based on colposcopy images, distinguishing between normal, pre-cancerous, and cancerous stages. CAD tools for cervical cancer screening are especially beneficial in low- and middle-income countries, where access to specialist healthcare workers is limited. Automated systems that analyse. Pap smear results are helping to increase early detection rates, ultimately improving outcomes in resource-poor settings.

CAD’s key advantages lie in its ability to enhance diagnostic accuracy, reduce the risk of human error, and improve time efficiency. By providing a second layer of analysis, CAD systems can catch abnormalities that may be missed during initial reviews. Additionally, CAD systems can assist radiologists in processing large volumes of data more quickly, which is particularly beneficial in busy hospitals or clinics. Another advantage is that CAD supports healthcare providers in low-resource settings, where access to trained specialists may be limited. In such cases, CAD systems can provide vital diagnostic assistance, improving healthcare accessibility. However, there are challenges associated with CAD systems. One of the main concerns is the potential for false positives (where the system incorrectly flags normal tissue as suspicious) or false negatives (where the system misses an abnormality). While continuous advancements in AI are helping to reduce these errors, they remain a consideration when implementing CAD systems in clinical practice. Additionally, data bias can affect the performance of CAD systems. If a CAD system is trained predominantly on data from specific population groups, it may not perform as well in other demographic groups, leading to inaccuracies in diagnosis.

In the context of gynaecological diseases, these advancements hold significant potential for improving diagnostic accuracy and facilitating precision medicine. AI-driven imaging can assist doctors in identifying subtle patterns that may be missed by human analysis, enhancing the quality of care. However, there are challenges related to the integration of these technologies, including data bias and the need for large, diverse datasets to ensure equitable outcomes across populations.

One of the most prominent applications of AI in gynaecology is in medical imaging. Machine learning algorithms have demonstrated proficiency in detecting abnormalities in ultrasound, MRI, and histopathological images. For instance, AI models have been used to enhance the early detection of ovarian and endometrial cancers, both of which often present with vague symptoms, leading to late diagnoses. AI-driven systems can analyse large datasets, identifying patterns that may be overlooked by human clinicians. For example, a study published in Nature Medicine showed that deep learning algorithms could improve the diagnostic accuracy of cervical cancer from Pap smears by reducing false negatives (Wang et al., 2020).

Neurology

Whilst representation of women for neurological conditions has improved in the last decade, there is still gender bias in trials and results for both sex are rarely ever discussed separately. Multiple sclerosis is twice as common in women and AI has shown great promise in using neuroimaging, genetic, and clinical data, Optical Coherence Tomography, serum and cerebrospinal fluid markers (six studies), movement function for diagnosis, prognosis and personalisation of treatment.

Migraine is up to three times more common in women than in men and diagnosis has been investigated by combining AI and ECG, NLP, MRI. Women are still very under-represented for stroke research and trial, despite being at higher risk. Diagnosis of stroke has been attempted using AI for MRI, and electromyography.

It is hard to check women representation in those papers, as most of them do not even report on the sex of participants. Women are also twice more likely to have Alzheimer’s. Although there is usually sex parity among participants in dementia trials, women’s representation remains lower than their representation in the dementia population. However, for rarer subtypes of dementia, men are four times more represented in Vascular dementia and LBD trials, even though prevalence is the same for both sex. For dementia, AI has been used with MRI, speech, gaze data. In the MRI ADNI dataset, female data represents 48.6%. In the speech Address dataset female data represents 55%.

Across all those conditions, sex-disaggregated analysis are often lacking and this flaw of clinical research is even more prominent in AI research, with papers, not even reporting on participant demographics. It is recognised that in clinical research, some drugs or interventions can be effective in a subgroup of population, e.g. women due to various factors and regulatory guidelines advise for subgroup analyses by sex. Doing subgroup analysis by sex in AI would allow for a better understanding of features leading to a diagnosis, which would also lead to a better understanding of the pathology. Moreover, for most datasets, women are underrepresented compared to their prevalence, which can also create a bias in AI models. especially if the dataset is imbalanced as well.

Geographical Impact

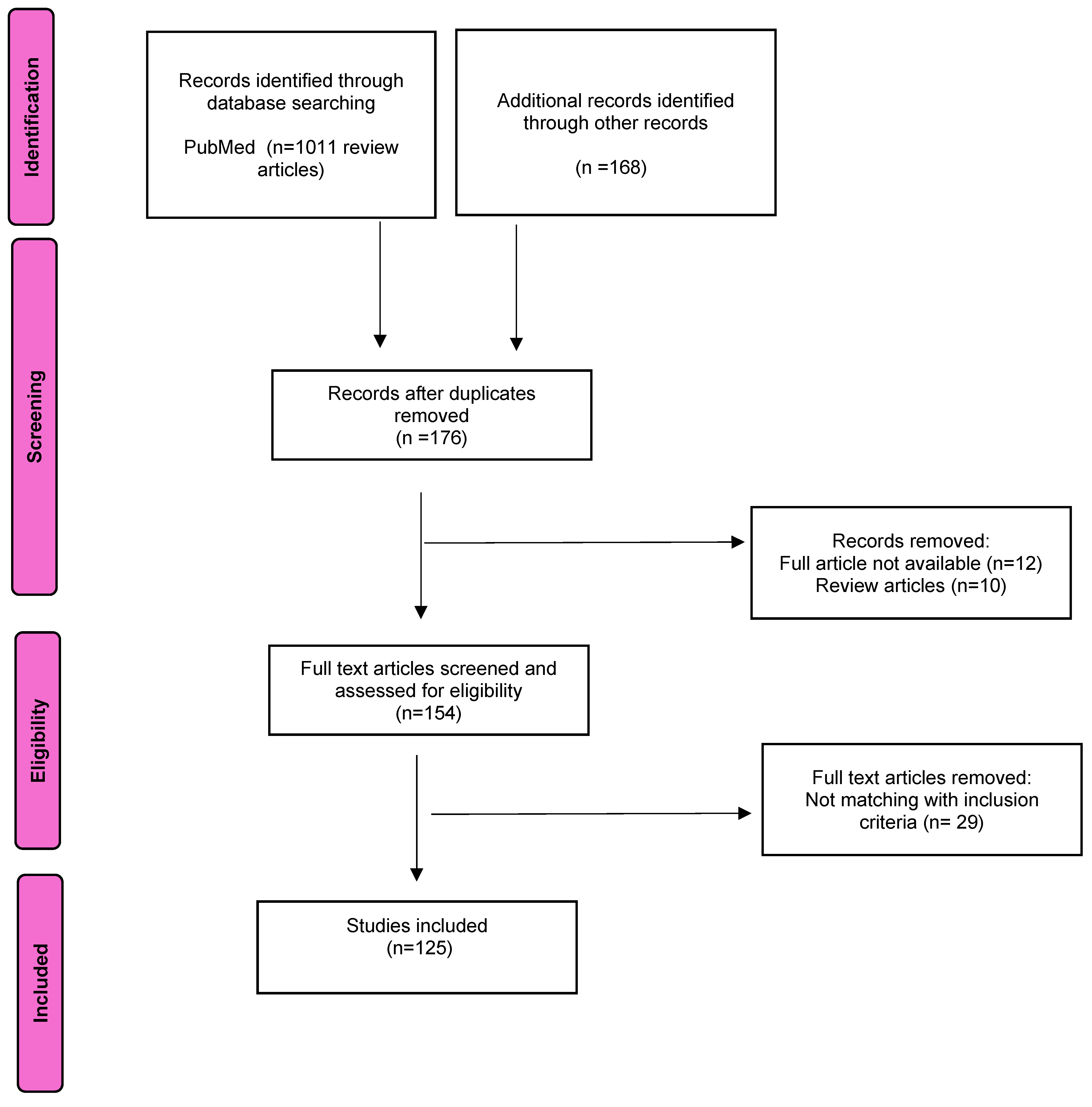

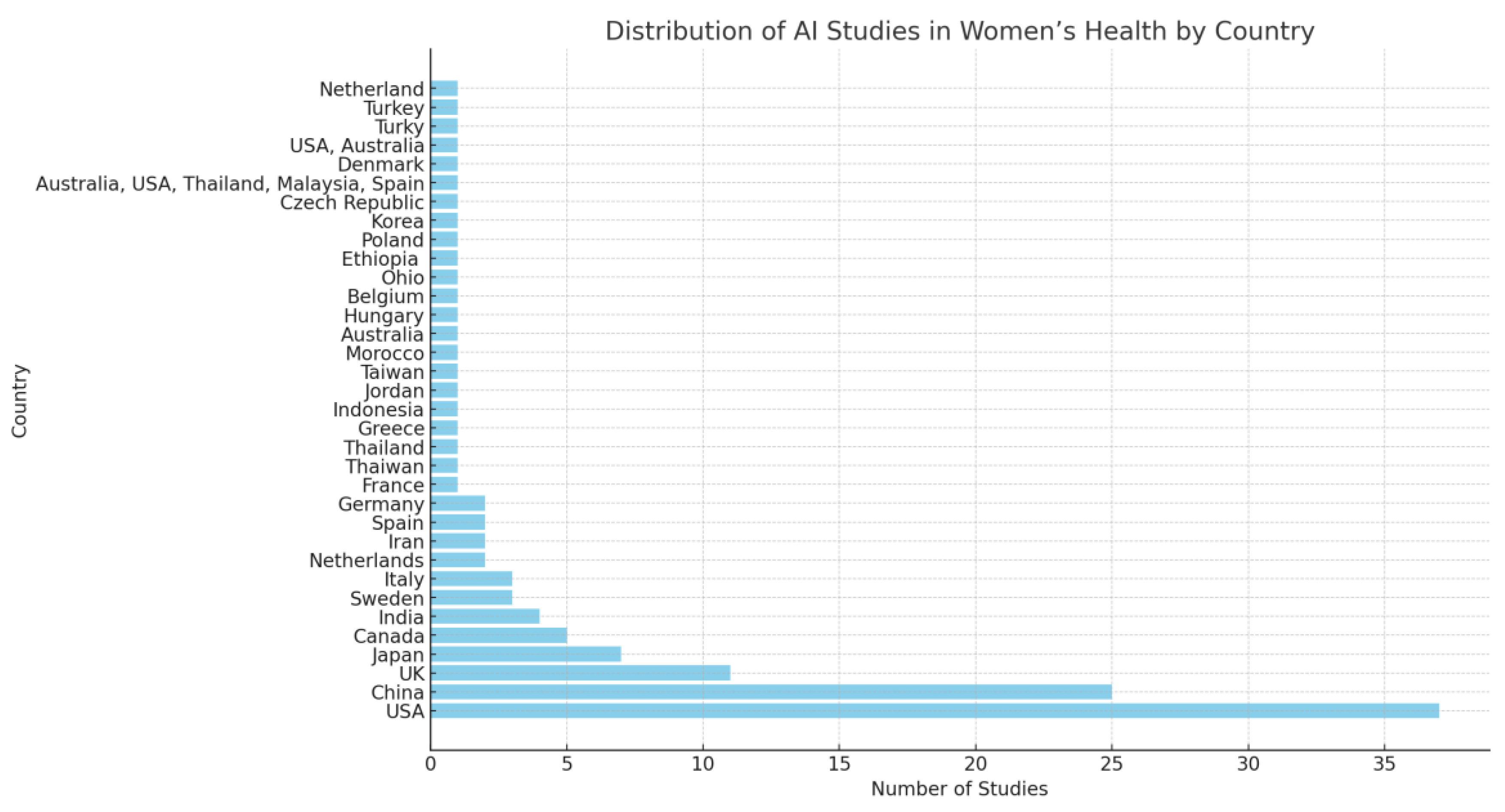

Most studies comprised of small sample sizes and geographically focused mostly within high-income-countries (HICs). Out of the 125 studies analysed, the majority—72 studies—were conducted in high-income countries such as the USA, the Netherlands, the UK, Japan, and Canada (

Figure 2). These countries have established robust healthcare systems, advanced technological infrastructure, and significant financial resources, which enable them to pioneer AI innovations in healthcare, including women’s health. In comparison, 37 studies were conducted in middle-income countries like China, India, and Turkey. Only one study took place in a low-income country, specifically Ethiopia. Furthermore, 15 studies were categorized as "unknown," where the geographical region of the study was either unclear or not specified. This distribution highlights a major disparity in the geographic focus of AI applications in women’s health research. High-income countries, with their access to abundant resources, advanced healthcare facilities, and comprehensive data, dominate the field of AI-driven healthcare research. This dominance allows them to develop and refine sophisticated AI tools for disease diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. However, this focus creates a significant gap, as women in low- and middle-income countries often face different healthcare challenges, lack access to advanced medical technologies, and have healthcare systems that are ill-equipped to implement cutting-edge AI applications. The underrepresentation of studies from these regions means that AI tools developed in high-income contexts may not fully address or account for the specific needs and conditions prevalent in low-resource settings.

Relying heavily on data and models developed in high-income countries can result in biases and limitations. AI systems trained on data from affluent regions may not perform as accurately or effectively in low- and middle-income countries, where factors like disease prevalence, healthcare infrastructure, and socioeconomic conditions vary significantly. Moreover, developing AI tools without considering these disparities risks widening the healthcare inequality gap. For AI to truly revolutionize women’s health globally, there must be a concerted effort to include diverse populations and settings in AI research, ensuring that AI models are representative, equitable, and adaptable across different healthcare environments.

Discussion

Although the use of AI in healthcare is far from universal in HICs, due to cost, procurement, provider buy-in, technology mistrust, adapting AI for use in low-income regions requires overcoming several unique challenges, but it also offers tremendous potential to improve women’s health in these settings. One of the major barriers is the lack of representative data from low-resource environments. AI models trained on data from high-income countries may not perform well in low-income areas due to differences in genetics, healthcare systems, and socio-economic conditions. To address this, efforts should focus on collecting healthcare data from local populations, which includes gathering information on different ethnic groups, local disease patterns, and specific healthcare needs. Collaborations between global AI developers and local healthcare providers are crucial for ensuring that AI models are tailored to the realities of low-income settings. Furthermore, AI tools should be adapted to work with the types of data that are readily available in these regions, such as mobile phone images or basic clinical indicators, which can still provide valuable insights without requiring high-tech equipment.

However, current AI models have limited by a lack of comprehensive, diverse datasets, which can hinder generalisation across populations. More robust, inclusive research is needed to enhance AI’s effectiveness (Priyanka et al 2022). Current literature highlights concern around bias in AI models, particularly those trained on datasets that inadequately represent women, especially those from diverse ethnic backgrounds. This lack of diversity can lead to skewed outcomes, with some AI systems performing less effectively for women of colour or those with atypical health profiles. A comprehensive review by Mehrabi et al. (2021) addresses the pervasive issue of bias in AI, noting that insufficient representation of minority groups can perpetuate inequities in healthcare(Mehrabi et al., 2021). Moreover, the absence of transparent reporting on AI decision-making processes poses ethical concerns, making it difficult for clinicians to fully trust or understand AI-generated recommendations(Topol, 2019).

Additionally, while AI could revolutionise reproductive health, particularly in areas such as fertility and menstrual health tracking, most AI tools remain limited by the quality and scope of existing research. Noyes and Havrilesky (2022) point out that many AI applications in reproductive medicine are built on datasets primarily derived from Western populations, which may not generalise well to low-resource settings or diverse populations. Overall, AI’s potential in women’s health is promising but must be approached with caution to ensure equitable and effective outcomes for all women.

Another critical adaptation is the need for low-cost, low-infrastructure solutions. In low-income regions, access to continuous internet or advanced medical infrastructure may be limited. AI systems can be designed to operate on mobile devices, which are becoming more common even in resource-poor areas. Mobile health (mHealth) platforms powered by AI can assist healthcare workers in remote regions with diagnostics, patient monitoring, and decision-making. These systems should also be able to function offline or with minimal connectivity to accommodate the realities of intermittent internet access. Simple, low-cost technologies like ultrasound machines or mobile cameras can be enhanced with AI to help detect and diagnose conditions such as cervical cancer or monitor maternal health without the need for sophisticated infrastructure.

AI can also support non-specialist healthcare workers in these regions. In areas where physicians or specialists are scarce, AI tools can provide decision support and guide frontline health workers through diagnosis and treatment protocols. This is particularly important for women’s health, where conditions like pregnancy complications or gynaecological cancers require timely and accurate interventions. AI-assisted systems can also enable telemedicine, allowing healthcare workers to share diagnostic data with specialists remotely, providing real-time feedback and guidance even in isolated areas. In deploying AI in low-income regions, it is important to consider ethical and cultural factors. AI solutions should be designed with inclusivity in mind, addressing the healthcare needs of underserved populations such as rural women, marginalized groups, and those with limited access to healthcare. Additionally, AI systems must be culturally sensitive, particularly when dealing with topics like reproductive health, which may be influenced by local customs and beliefs. Affordability and scalability are also key considerations. AI tools must be low-cost and sustainable, utilizing open-source algorithms or low-cost hardware to ensure that they can be widely adopted. Scalable solutions that work within existing infrastructures, such as mobile networks or basic health clinics, are more likely to have a broad impact.

Capacity building is another essential aspect of AI adaptation in low-income regions. Healthcare workers need to be trained to use AI tools effectively, even if they lack formal training in advanced medicine or AI. User-friendly interfaces and practical training programs can help ensure that local healthcare providers can benefit from AI’s capabilities. In addition to healthcare worker training, local capacity for managing and adapting AI technologies should be developed. Training local technologists and data scientists will help foster local ownership of AI systems and ensure their long-term sustainability.

Health Inequalities and Disparities

The importance of acknowledging biological sex in research would ensure effective and equitable healthcare interventions. The inclusion of gender analysis addresses how societal norms, power dynamics, and access to resources contribute to disparities in health outcomes, as highlighted in the European Gender Equality Index of 2021. Another possible solution to address disparities would be for funding agencies to prioritise sex and gender-based analysis (SGBA) in health research. Encouraging such analyses would help to reduce health disparities and enhance overall health outcomes by acknowledging the complex interplay between biological, psychosocial, and socio-economic factors. Moreover, in minority groups, cultural mistrust of healthcare is linked to a lack of commitment to treatment plans, negative health behaviors, and undesired health outcomes. Bridging that gap would also increase acceptability.

Funding Landscape

Smith (2023) provided an important critique of the misalignment between research funding and the burden of disease in women's health where underfunding was part of a much broader issue of gender disparity in health research funding globally (Smith, 2023).

Funding for women’s health research is not proportionate to the burden of diseases that predominantly affect women. Sarah Temkin, of the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, observes that the funding landscape fails to reflect the pressing health issues facing women. This is supported by findings from Mirin’s analysis, which indicate that women's health concerns, especially gynaecological cancers, are persistently undervalued in terms of research funding. This underinvestment contrasts with the significant disease burden these conditions place on women (Stranges et al., 2023). In assessing these claims, it is evident that such a misalignment has serious implications for health outcomes. Underfunded areas of research may result in slower medical advancements and delayed development of treatments, contributing to higher morbidity and mortality rates. Mirin's research, alongside similar studies, underscores the importance of adjusting research priorities to better align with the real-world burden of diseases. This critical gap in funding further reflects the historical marginalisation of women’s health issues in medical research, reinforcing gender inequities.

Research into the use of AI in women’s health suffers from the same disparities in funding as research into other elements of womens’ healthcare as seen in cancer (Jones et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2020).

Broader Implications and Global Perspective

Women’s health issues extend beyond gynaecological and obstetric concerns, as biological sex affects all organs and thus all aspects of health, yet research tends to isolate women’s health to reproductive issues. This narrow scope disregards how diseases such as Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular disease manifest differently in women, a gap that potentially limits the effectiveness of medical treatments. Galea’s stance is supported by numerous studies that show women’s health conditions are often overlooked or under-researched due to an entrenched bias in medical research (Holdcroft, 2007, Verdonk et al., 2009).

Moreover, the global analysis further demonstrates the systemic nature of the problem. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the UK’s Medical Research Council provide insight into the broader international context of health research funding. The data reveals that women’s health remains underfunded, even in high-income countries with relatively robust research infrastructures. While the UK’s £96 million investment in women’s health over five years is notable, Galea’s critique that women’s health research should transcend reproductive issues to include conditions like depression and heart disease is particularly compelling.

Funding Justifications and Public Health Urgencies

One potential counterargument presented by the NIH in the article is that funding is often diverted to address urgent public health issues, such as infectious disease outbreaks. While these justifications hold merit in specific contexts, they risk perpetuating long-standing inequalities by neglecting chronic health issues that disproportionately affect women. Prioritising emergent health threats is necessary, but it should not come at the expense of sustainable investment in areas like women’s health, where advancements have lagged.

The inadequacies in research funding for women’s health exposes a clear misalignment between financial investment and disease burden. Experts like Sarah Temkin and Liisa Galea offer critical perspectives on the implications of underfunding, particularly for gynaecological cancers and conditions that affect women beyond reproductive health. While international efforts have made strides in increasing awareness and funding, significant gaps remain. As more evidence accumulates, it is clear that a concerted effort is required to ensure that research funding equitably addresses the health needs of women, with a broader and more inclusive approach that recognises the full impact of sex on health.