Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Sample Description

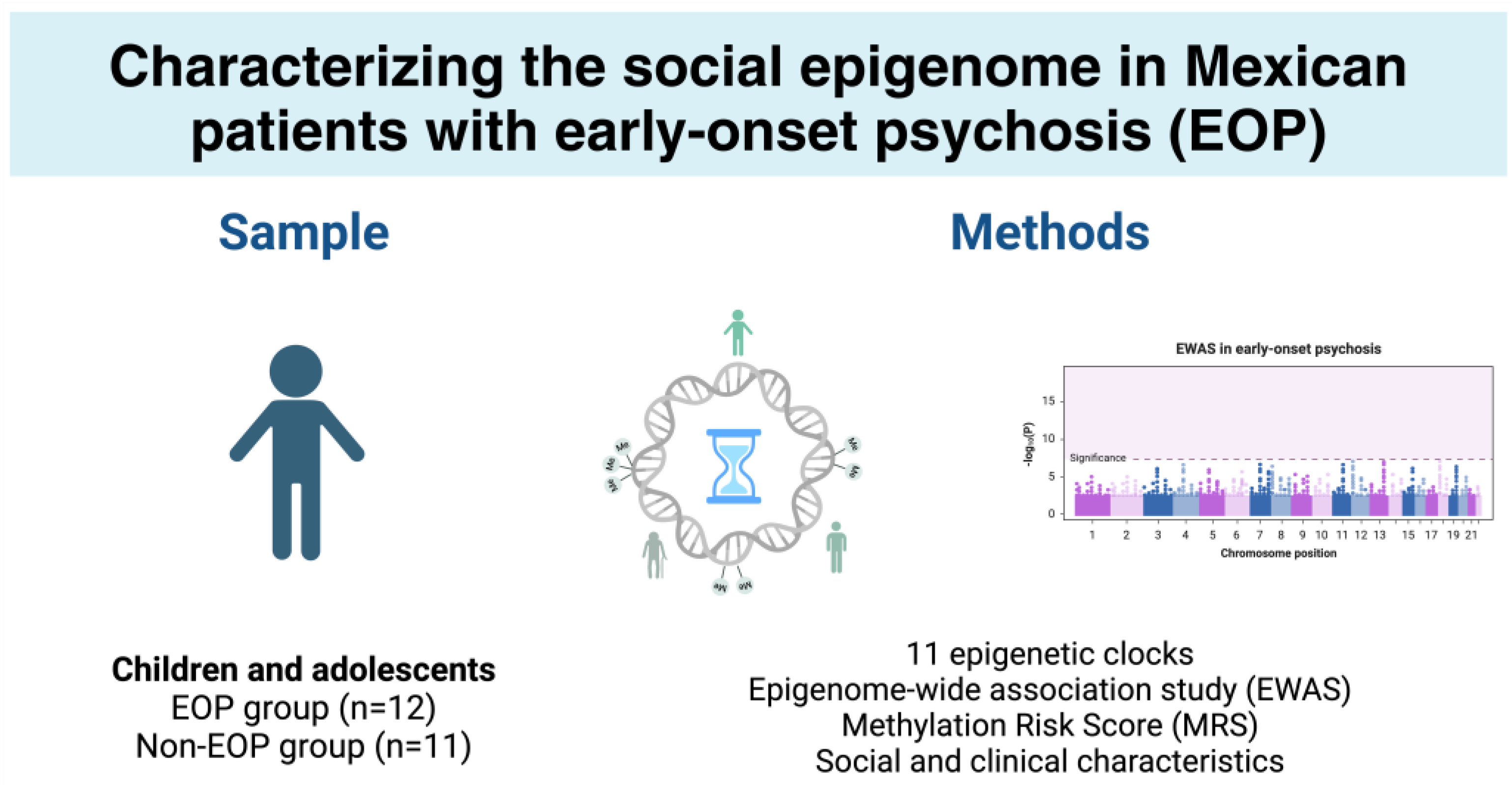

2.2. Epigenetic Age

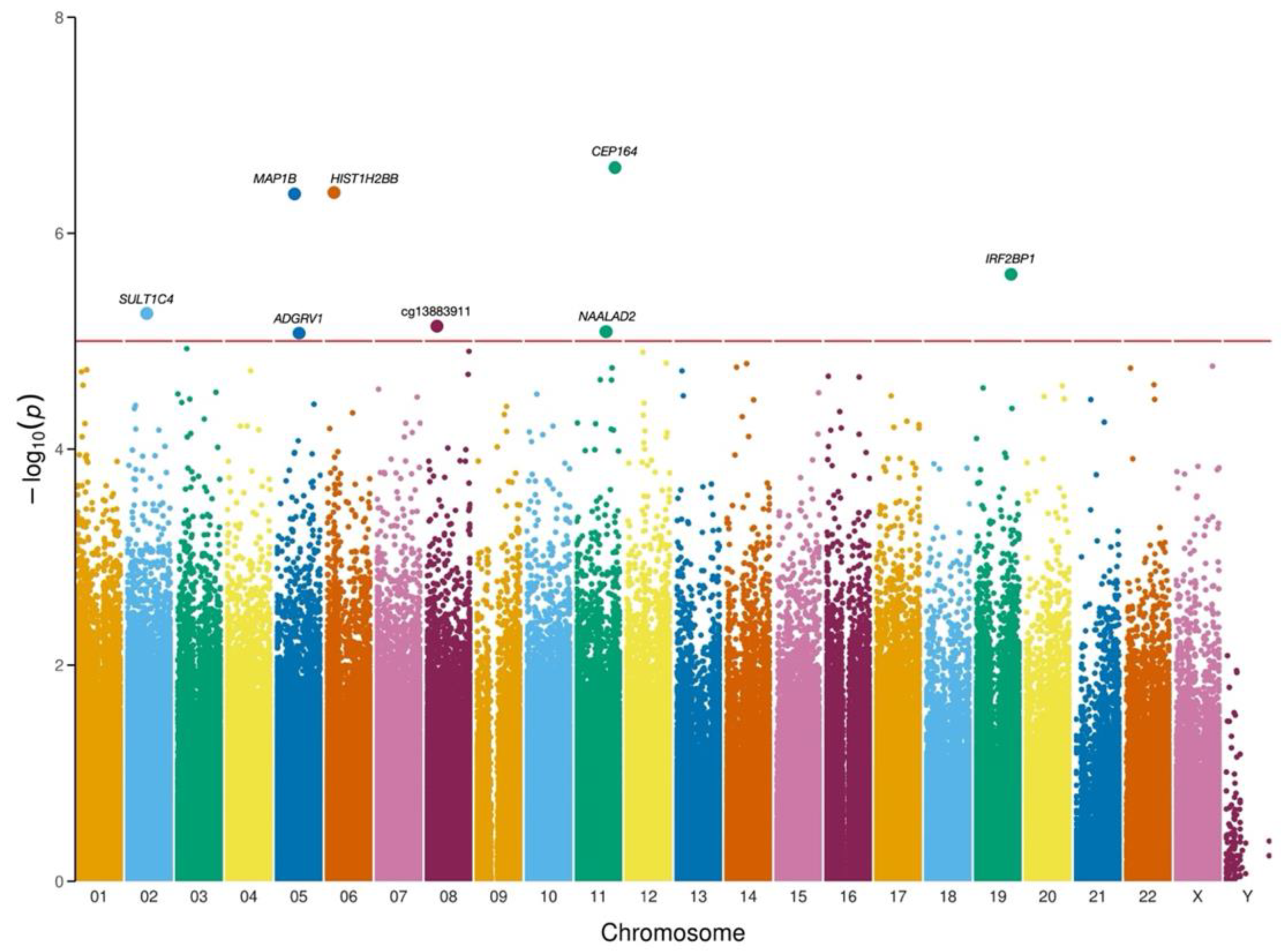

2.3. Epigenome-Wide Association Study

2.4. Methylation Risk Score

3. Discussion

3.1. Years of Schooling Was Associated with Epigenetic Age in EOP

3.2. EWAS Suggested Potential Novel Associations with EOP

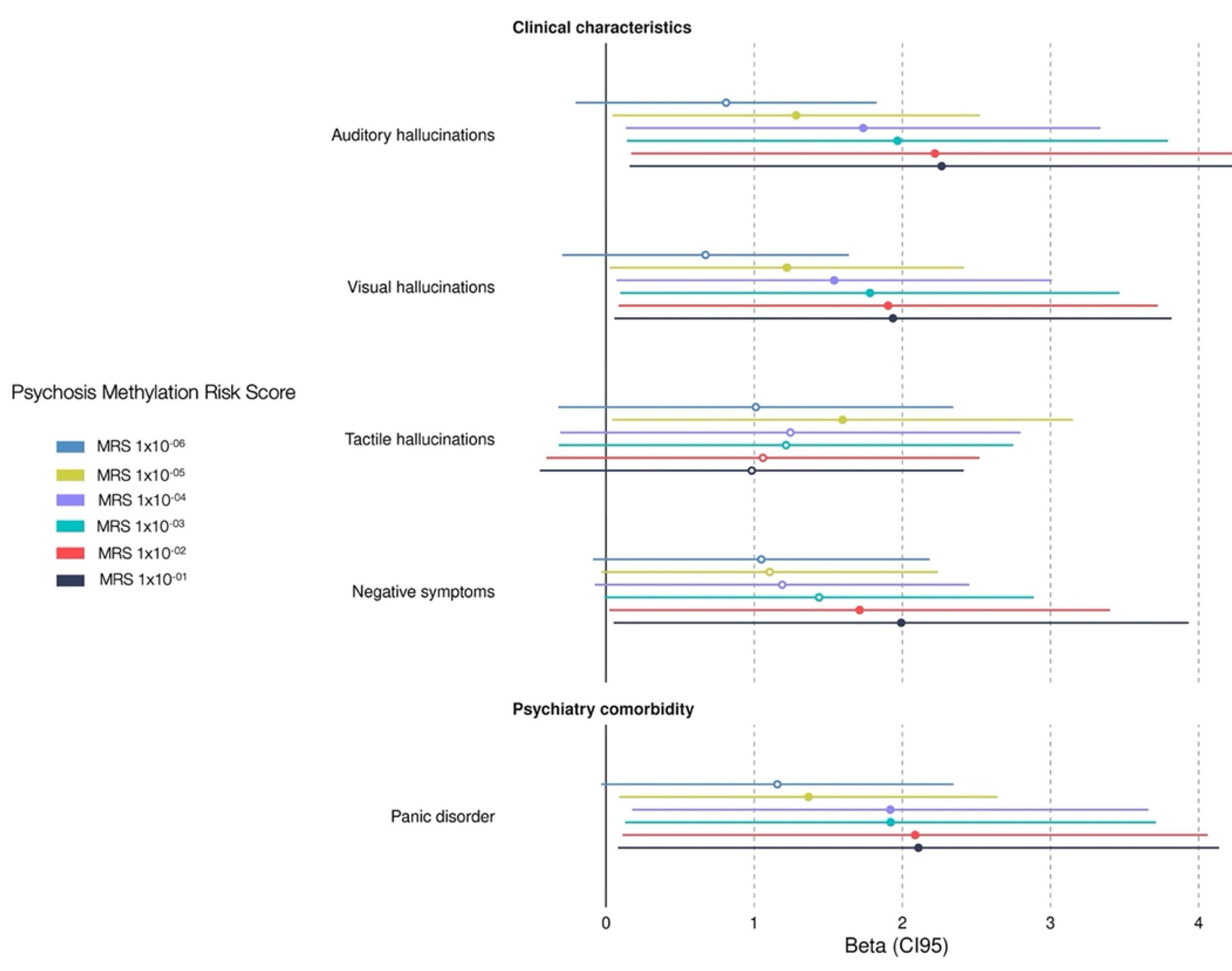

3.3. Association Between Clinical Charateristics Associated with Psychosis MRS

3.4. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Population

4.2. Study Design

4.3. DNA Extraction

4.4. Genomic-Wide Quantification of DNA Methylation

4.5. Epigenetic Clocks

4.6. Statistical Analysis

4.7. EWAS and Methylation Risk Score

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADGRV1 | Adhesion G Protein-coupled Receptor V1 gene |

| BLUP | Best Linear Unbiased Prediction |

| CEP164 | Centrosomal Protein 164 gene |

| CpG | Cytosine-Guanine site |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DNAm | Deoxyribonucleic Acid methylation |

| DNAmTL | DNA methylation-based telomere length |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition |

| DunedinPoAm38 | Dunedin Pace of Aging |

| EN | Elastic net |

| EOP | Early-onset psychosis |

| EOP-MRS | Psychosis-Methylation Risk Score |

| EWAS | Epigenome-wide association analysis |

| FEP | First episode of pychosis |

| GAF | Global Assessment of Functioning |

| HIST1H2BB | Histone Cluster 1 H2B Family Member B gene |

| IRF2BP1 | Interferon Regulatory Factor 2 Binding Protein 1 gene |

| K-SADS PL-5 | Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime version DSM-5 |

| MAP1B | Microtubule Associated Protein 1B gene |

| MRS | Methylation Risk Score |

| NAALAD2 | N-Acetylated Alpha-Linked Acidic Dipeptidase 2 gene |

| PC | Principal component |

| PedBE | Pediatric Buccal Epigenetic |

| SULT1C4 | Sulfotransferase Family 1C Member 4 gene |

| TSS | Transcription start site |

References

- Salazar de Pablo, G.; Rodriguez, V.; Besana, F.; Civardi, S.C.; Arienti, V.; Maraña Garceo, L.; Andrés-Camazón, P.; Catalan, A.; Rogdaki, M.; Abbott, C.; et al. Umbrella Review: Atlas of the Meta-Analytical Evidence of Early-Onset Psychosis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024, 63, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusar-Poli, P.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Correll, C.U.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Millan, M.J.; Borgwardt, S.; Galderisi, S.; Bechdolf, A.; Pfennig, A.; Kessing, L.V.; et al. Prevention of Psychosis: Advances in Detection, Prognosis, and Intervention. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, D.; Chesney, E.; Cullen, A.E.; Davies, C.; Englund, A.; Gifford, G.; Kerins, S.; Lalousis, P.A.; Logeswaran, Y.; Merritt, K.; et al. Exploring causal mechanisms of psychosis risk. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2024, 162, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, I.; Connor, D.; Clarke, M.C.; Devlin, N.; Harley, M.; Cannon, M. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Psychol Med 2012, 42, 1857–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, D.I.; Thomas, S.; Gogtay, N.; Rapoport, J.L. Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia and Early-onset Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: An Update. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2020, 29, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, S.; Kounali, D.; Cannon, M.; David, A.S.; Gunnell, D.; Heron, J.; Jones, P.B.; Lewis, S.; Sullivan, S.; Wolke, D.; et al. Psychotic experiences and psychotic disorders at age 18 in relation to psychotic experiences at age 12 in a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2013, 170, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftimovici, A.; Kebir, O.; Jiao, C.; He, Q.; Krebs, M.O.; Chaumette, B. Dysmaturational Longitudinal Epigenetic Aging During Transition to Psychosis. Schizophr Bull Open 2022, 3, sgac030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Walton, E.; Neumann, A.; Thio, C.H.L.; Felix, J.F.; van, I.M.H.; Pappa, I.; Cecil, C.A.M. DNA methylation at birth and lateral ventricular volume in childhood: a neuroimaging epigenetics study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2024, 65, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.K.; Leathem, L.D.; Currin, D.L.; Karlsgodt, K.H. Adolescent Neurodevelopment and Vulnerability to Psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 2021, 89, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasic, D.; Hajek, T.; Alda, M.; Uher, R. Risk of mental illness in offspring of parents with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of family high-risk studies. Schizophr Bull 2014, 40, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radua, J.; Ramella-Cravaro, V.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Reichenberg, A.; Phiphopthatsanee, N.; Amir, T.; Yenn Thoo, H.; Oliver, D.; Davies, C.; Morgan, C.; et al. What causes psychosis? An umbrella review of risk and protective factors. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.J.; Freeman, D.; Lundström, S.; Larsson, H.; Ronald, A. Heritability of Psychotic Experiences in Adolescents and Interaction With Environmental Risk. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouter, K.; Šalamon Arčan, I.; Videtič Paska, A. Epigenetics in psychiatry: Beyond DNA methylation. World J Psychiatry 2023, 13, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, E.; Dempster, E.L.; Mansell, G.; Burrage, J.; Bass, N.; Bohlken, M.M.; Corvin, A.; Curtis, C.J.; Dempster, D.; Di Forti, M.; et al. DNA methylation meta-analysis reveals cellular alterations in psychosis and markers of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Elife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameda, L.; Liu, Z.; Sham, P.C.; Aas, M.; Trotta, G.; Rodriguez, V.; Di Forti, M.; Stilo, S.A.; Kandaswamy, R.; Arango, C.; et al. Exploring the mediation of DNA methylation across the epigenome between childhood adversity and First Episode of Psychosis-findings from the EU-GEI study. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 2095–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Luo, T.; Yang, C.; Liu, M.; Shen, Y.; Hao, W. Psychotic symptoms associated increased CpG methylation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 8 gene in Chinese Han males with schizophrenia and methamphetamine induced psychotic disorder: a longitudinal study. Schizophrenia (Heidelb) 2024, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura, A.G.; Prohens, L.; Julià, L.; Amoretti, S.; M, R.I.; Pino-Camacho, L.; Cano-Escalera, G.; Mane, A.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R.; Roldan, A.; et al. Methylation profile scores of environmental exposures and risk of relapse after a first episode of schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2025, 94, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kular, L.; Kular, S. Epigenetics applied to psychiatry: Clinical opportunities and future challenges. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2018, 72, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, S.J.; Vazquez, A.Y.; Klump, K.L.; Hyde, L.W.; Burt, S.A.; Clark, S.L. Associations of depression and anxiety symptoms in childhood and adolescence with epigenetic aging. J Affect Disord 2024, 352, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smigielski, L.; Jagannath, V.; Rössler, W.; Walitza, S.; Grünblatt, E. Epigenetic mechanisms in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a systematic review of empirical human findings. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 25, 1718–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusupov, N.; Dieckmann, L.; Erhart, M.; Sauer, S.; Rex-Haffner, M.; Kopf-Beck, J.; Brückl, T.M.; Czamara, D.; Binder, E.B. Transdiagnostic evaluation of epigenetic age acceleration and burden of psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, J.P.Y.; Abram, S.V.; Loewy, R.L.; Stuart, B.; Fryer, S.L.; Vinogradov, S.; Mathalon, D.H. Brain Age Gap in Early Illness Schizophrenia and the Clinical High-Risk Syndrome: Associations With Experiential Negative Symptoms and Conversion to Psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2024, 50, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dada, O.; Adanty, C.; Dai, N.; Jeremian, R.; Alli, S.; Gerretsen, P.; Graff, A.; Strauss, J.; De Luca, V. Biological aging in schizophrenia and psychosis severity: DNA methylation analysis. Psychiatry Res 2021, 296, 113646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A.K.; Lin, J.J.; Tseng, H.H.; Wang, X.Y.; Jang, F.L.; Chen, P.S.; Huang, C.C.; Hsieh, S.; Lin, S.H. DNA methylation signature aberration as potential biomarkers in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Constructing a methylation risk score using a machine learning method. J Psychiatr Res 2023, 157, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohi, K.; Shimada, M.; Soda, M.; Nishizawa, D.; Fujikane, D.; Takai, K.; Kuramitsu, A.; Muto, Y.; Sugiyama, S.; Hasegawa, J.; et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation risk scores for schizophrenia derived from blood and brain tissues further explain the genetic risk in patients stratified by polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. BMJ Ment Health 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, C.E.; Wong, J.Y.Y.; Beck, S.; Berndt, S.I.; Franceschini, N. Diversity in EWAS: current state, challenges, and solutions. Genome Med 2022, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Caracteristicas educativas de la población. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/tabulados/interactivos/?pxq=Educacion_Educacion_05_2f6d2a08-babc-442f-b4e0-25f7d324dfe0&idrt=15&opc=t (accessed on 07 March 2025).

- Chrusciel, J.H.; Orso, R.; de Mattos, B.P.; Fries, G.R.; Kristensen, C.H.; Grassi-Oliveira, R.; Viola, T.W. A systematic review and meta-analysis of epigenetic clocks in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2022, 246, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.K.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Yu, H.; Lu, Z.; Li, W.Q.; Yang, Y.F.; Xiao, X.; Yan, H.; Lu, T.L.; et al. Prediction of treatment response to antipsychotic drugs for precision medicine approach to schizophrenia: randomized trials and multiomics analysis. Mil Med Res 2023, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engen, M.J.; Vaskinn, A.; Melle, I.; Færden, A.; Lyngstad, S.H.; Flaaten, C.B.; Widing, L.H.; Wold, K.F.; Åsbø, G.; Haatveit, B.; et al. Cognitive and Global Functioning in Patients With First-Episode Psychosis Stratified by Level of Negative Symptoms. A 10-Year Follow-Up Study. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 841057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhassan, N.M.; Elhusein, B.; Al Abdulla, M.; Saad, T.A.; Kumar, R. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with recurrent psychiatric readmissions in Qatar. J Int Med Res 2020, 48, 300060520977382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Karakatsoulis, G.N.; Abraham, S.; Adorjan, K.; Ahmed, H.U.; Alarcón, R.D.; Arai, K.; Auwal, S.S.; Berk, M.; Bjedov, S.; et al. Somatic multicomorbidity and disability in patients with psychiatric disorders in comparison to the general population: a quasi-epidemiological investigation in 54,826 subjects from 40 countries (COMET-G study). CNS Spectr 2024, 29, 126–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Magaña, J.J.; Genis-Mendoza, A.D.; Santana, D.; Tóvilla-Zárate, C.A.; Lanzagorta, N.; Nicolini, H. [The presence of a psychiatric diagnosis could alter the epigenetic clock in monozygotic twins]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2021, 56, 361–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Verjan, J.C.; Esparza-Aguilar, M.; Martín-Martín, V.; Salazar-Perez, C.; Cadena-Trejo, C.; Gutierrez-Robledo, L.M.; Martínez-Magaña, J.J.; Nicolini, H.; Arroyo, P. Years of Schooling Could Reduce Epigenetic Aging: A Study of a Mexican Cohort. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffington, L.; Belsky, D.W. Integrating DNA Methylation Measures of Biological Aging into Social Determinants of Health Research. Curr Environ Health Rep 2022, 9, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel-Campos, D.; Gonzalez-Billault, C. The MAP1B case: an old MAP that is new again. Dev Neurobiol 2014, 74, 953–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, M.M.; Reay, W.R.; Geaghan, M.P.; Kiltschewskij, D.J.; Green, M.J.; Weidenhofer, J.; Glatt, S.J.; Cairns, M.J. miRNA cargo in circulating vesicles from neurons is altered in individuals with schizophrenia and associated with severe disease. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadi4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle, B.L.; Rodriguez-Torres, S.; Kuhn, E.; Díaz-Montes, T.; Parrilla-Castellar, E.; Lawson, F.P.; Folawiyo, O.; Ili-Gangas, C.; Brebi-Mieville, P.; Eshleman, J.R.; et al. HIST1H2BB and MAGI2 Methylation and Somatic Mutations as Precision Medicine Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Prognosis of High-grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2020, 13, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świtońska, K.; Szlachcic, W.J.; Handschuh, L.; Wojciechowski, P.; Marczak, Ł.; Stelmaszczuk, M.; Figlerowicz, M.; Figiel, M. Identification of Altered Developmental Pathways in Human Juvenile HD iPSC With 71Q and 109Q Using Transcriptome Profiling. Front Cell Neurosci 2018, 12, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gana, S.; Serpieri, V.; Valente, E.M. Genotype-phenotype correlates in Joubert syndrome: A review. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2022, 190, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, A.; Cruz, S.A.; Qin, Z.; Couture, P.; Vilmundarson, R.O.; Huang, H.; Stewart, A.F.R.; Chen, H.-H. IRF2BP2-deficient microglia block the anxiolytic effect of enhanced postnatal care. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 9836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubaisi, S.; Fang, H.; Caruso, J.A.; Gaedigk, R.; Vyhlidal, C.A.; Kocarek, T.A.; Runge-Morris, M. Developmental Expression of SULT1C4 Transcript Variants in Human Liver: Implications for Discordance Between SULT1C4 mRNA and Protein Levels. Drug Metab Dispos 2020, 48, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.J. Schizophrenia susceptibility genes converge on interlinked pathways related to glutamatergic transmission and long-term potentiation, oxidative stress and oligodendrocyte viability. Schizophr Res 2006, 86, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güler, B.E.; Linnert, J.; Wolfrum, U. Monitoring paxillin in astrocytes reveals the significance of the adhesion G protein coupled receptor VLGR1/ADGRV1 for focal adhesion assembly. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2023, 133, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Meng, H.; Liang, X.; Lei, X.; Zhang, J.; Bian, W.; He, N.; Lin, Z.; Song, X.; Zhu, W.; et al. ADGRV1 Variants in Febrile Seizures/Epilepsy With Antecedent Febrile Seizures and Their Associations With Audio-Visual Abnormalities. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 864074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.A.; Goodman, S.J.; MacIsaac, J.L.; Obradović, J.; Barr, R.G.; Boyce, W.T.; Kobor, M.S. Integration of DNA methylation patterns and genetic variation in human pediatric tissues help inform EWAS design and interpretation. Epigenetics Chromatin 2019, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugué, P.A.; Wilson, R.; Lehne, B.; Jayasekara, H.; Wang, X.; Jung, C.H.; Joo, J.E.; Makalic, E.; Schmidt, D.F.; Baglietto, L.; et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with widespread changes in blood DNA methylation: Analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal data. Addict Biol 2021, 26, e12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.M.; Jaeger, P.A.; Kreisberg, J.F.; Licon, K.; Jepsen, K.L.; Khosroheidari, M.; Morsey, B.M.; Swindells, S.; Shen, H.; Ng, C.T.; et al. Methylome-wide Analysis of Chronic HIV Infection Reveals Five-Year Increase in Biological Age and Epigenetic Targeting of HLA. Mol Cell 2016, 62, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, R.H.; Neumann, A.; Cecil, C.A.M.; Walton, E.; Houtepen, L.C.; Simpkin, A.J.; Rijlaarsdam, J.; Heijmans, B.T.; Gaunt, T.R.; Felix, J.F.; et al. Epigenome-wide change and variation in DNA methylation in childhood: trajectories from birth to late adolescence. Hum Mol Genet 2021, 30, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Liang, C.; Kochunov, P.; Hutchison, K.E.; Sui, J.; Jiang, R.; Zhi, D.; Vergara, V.M.; Yang, X.; Zhang, D.; et al. Associations of alcohol and tobacco use with psychotic, depressive and developmental disorders revealed via multimodal neuroimaging. Transl Psychiatry 2024, 14, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richetto, J.; Meyer, U. Epigenetic Modifications in Schizophrenia and Related Disorders: Molecular Scars of Environmental Exposures and Source of Phenotypic Variability. Biol Psychiatry 2021, 89, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, A.K.; Weber, R.; Kamei, N.; Wilcox Thai, C.; Arora, H.; Mortazavi, A.; Stern, H.S.; Glynn, L.; Baram, T.Z. Individual longitudinal changes in DNA-methylome identify signatures of early-life adversity and correlate with later outcome. Neurobiol Stress 2024, 31, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, A.; Jones, E.J.H.; Wong, C.C.Y.; Meaburn, E.; Xia, B.; Pasco, G.; Lloyd-Fox, S.; Charman, T.; Bolton, P.; Johnson, M.H. Leveraging epigenetics to examine differences in developmental trajectories of social attention: A proof-of-principle study of DNA methylation in infants with older siblings with autism. Infant Behav Dev 2020, 60, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiltschewskij, D.J.; Reay, W.R.; Geaghan, M.P.; Atkins, J.R.; Xavier, A.; Zhang, X.; Watkeys, O.J.; Carr, V.J.; Scott, R.J.; Green, M.J.; et al. Alteration of DNA Methylation and Epigenetic Scores Associated With Features of Schizophrenia and Common Variant Genetic Risk. Biol Psychiatry 2024, 95, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Peña, F.R.; Villavicencio, L.R.; Palacio, J.D.; Félix, F.J.; Larraguibel, M.; Viola, L.; Ortiz, S.; Rosetti, M.; Abadi, A.; Montiel, C.; et al. Validity and reliability of the kiddie schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia present and lifetime version DSM-5 (K-SADS-PL-5) Spanish version. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić, B.; Jerotić, S.; Ristić, I.; Zebić, M.; Jovanović, N.; Russo, M.; Marić, N.P. Long-Term Benzodiazepine Prescription During Maintenance Therapy of Individuals With Psychosis Spectrum Disorders-Associations With Cognition and Global Functioning. Clin Neuropharmacol 2021, 44, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezelius, C.M.E.; Wahlund, B.A.; Wiberg, B.M. Relation between increasing attachment security and weight gain: a clinical study of adolescents and their parents at an outpatient ward. Eat Weight Disord 2023, 28, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegí-Sisó, D.; de Prado, P.; Ronkainen, J.; Bustamante, M.; González, J.R. methylclock: a Bioconductor package to estimate DNA methylation age. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 1759–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Chen, B.H.; Assimes, T.L.; Bandinelli, S.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Li, Y.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 2018, 10, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannum, G.; Guinney, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Hughes, G.; Sadda, S.; Klotzle, B.; Bibikova, M.; Fan, J.B.; Gao, Y.; et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol Cell 2013, 49, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Vallerga, C.L.; Walker, R.M.; Lin, T.; Henders, A.K.; Montgomery, G.W.; He, J.; Fan, D.; Fowdar, J.; Kennedy, M.; et al. Improved precision of epigenetic clock estimates across tissues and its implication for biological ageing. Genome Med 2019, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.T.; Seeboth, A.; Tsai, P.C.; Sun, D.; Quach, A.; Reiner, A.P.; Kooperberg, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; et al. DNA methylation-based estimator of telomere length. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 5895–5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, L.M.; O'Donnell, K.J.; McGill, M.G.; Edgar, R.D.; Jones, M.J.; MacIsaac, J.L.; Lin, D.T.S.; Ramadori, K.; Morin, A.; Gladish, N.; et al. The PedBE clock accurately estimates DNA methylation age in pediatric buccal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 23329–23335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsky, D.W.; Caspi, A.; Arseneault, L.; Baccarelli, A.; Corcoran, D.L.; Gao, X.; Hannon, E.; Harrington, H.L.; Rasmussen, L.J.; Houts, R.; et al. Quantification of the pace of biological aging in humans through a blood test, the DunedinPoAm DNA methylation algorithm. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol 2013, 14, R115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Oshima, J.; Martin, G.M.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Cohen, H.; Felton, S.; Matsuyama, M.; Lowe, D.; Kabacik, S.; et al. Epigenetic clock for skin and blood cells applied to Hutchinson Gilford Progeria Syndrome and ex vivo studies. Aging (Albany NY) 2018, 10, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanatharathorn, A.; Boks, M.P.; Maihofer, A.X.; Aiello, A.E.; Amstadter, A.B.; Ashley-Koch, A.E.; Baker, D.G.; Beckham, J.C.; Bromet, E.; Dennis, M.; et al. Epigenome-wide association of PTSD from heterogeneous cohorts with a common multi-site analysis pipeline. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2017, 174, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battram, T.; Yousefi, P.; Crawford, G.; Prince, C.; Sheikhali Babaei, M.; Sharp, G.; Hatcher, C.; Vega-Salas, M.J.; Khodabakhsh, S.; Whitehurst, O.; et al. The EWAS Catalog: a database of epigenome-wide association studies. Wellcome Open Res 2022, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | EOP (n=12) | Non-EOP (n=11) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | years ± SD | 15.5 ± 1.56 | 13.36 ± 2.57 | 0.030a |

| Gender | Male, n (%) | 6 (50) | 7 (64) | 0.680c |

| Female, n (%) | 6 (50) | 4 (36) | ||

| Education | years ± SD | 9.3 ± 1.96 | 7.2 ± 2.05 | 0.023a |

| Body Mass Index | z-score, mean ± SD | 1.08 ± 1.15 | 0.67 ± 1.50 | 0.368a |

| Psychiatric admissions | n (%) | 7 (58) | 1 (9) | 0.027c |

| Total, median (min-max) |

1 (0-4) | 0 (0-1) | 0.016b | |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | n (%) | 12(100) | 9 (81) | 0.370c |

| Mood disorders, n (%) | 11 (91) | 8 (72) | 0.316c | |

| Anxiety and stress disorders, n (%) | 10 (83) | 4 (36) | 0.036c | |

| Conduct disorders, n (%) | 5 (41) | 5 (45) | 1c | |

| Neurodevelopment disorders, n (%) | 1 (8) | 4 (36) | 0.155c | |

| Eating disorder, n (%) | 4 (33) | 0 | 0.093c | |

| GAF | Total score, mean ± SD | 43.33 ± 15.14 | 74 ± 6.41 | 0.00003a |

| Minimal, n (%) | 1 (8) | 3 (27) | 0.017c | |

| Mild, n (%) | 1 (8) | 2 (18) | ||

| Moderate, n (%) | 2 (16) | 0 | ||

| Severe, n (%) | 8 (66) | 0 | ||

| Epigenetic age | Wu`s clock, mean ± SD | 11.08 ± 0.89 | 10.29 ± 0.78 | 0.015 |

| Epigenetic calculator | Age r, p |

GAF r, p |

Admissions r, p |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLUP | 0.37, 0.079 | -0.40, 0.056 | 0.40, 0.056 |

| DNAmTL | -0.12, 0.555 | 0.27, 0.198 | -0.43, 0.038 |

| DunnedinPoAm38 | 0.26, 0.224 | -0.17, 0.434 | 0.19, 0.368 |

| EN | 0.26, 0.220 | -0.26, 0.217 | 0.40, 0.057 |

| Hannum | 0.25, 0.238 | -0.23, 0.274 | 0.29, 0.174 |

| Horvath-1 | 0.18, 0.398 | 0.13, 0.553 | -0.07, 0.742 |

| Horvath-2 | 0.03, 0.848 | -0.17, 0.427 | 0.34, 0.107 |

| Levine | 0.35, 0.100 | -0.05, 0.806 | 0.09, 0.672 |

| PedBE | 0.41, 0.046 | -0.53, 0.008 | 0.56, 0.005 |

| Wu | 0.30, 0.150 | -0.45, 0.027 | 0.49, 0.015 |

| Zhang | 0.24, 0.253 | -0.21, 0.324 | 0.35, 0.097 |

| Epiclock | Age (years) | Sex | Schooling (years) | Comorbidity | Admissions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | |

| BLUP | 1.786 (0.551) | 0.004 | - | - | -1.820 (0.544) | 0.003 | 0.496 (0.225) | 0.041 | - | - |

| DNAmTL | -0.071 (0.023) | 0.006 | - | - | 0.086 (0.022) | 0.001 | -0.134 (0.051) | 0.017 | -0.134 (0.051) | 0.017 |

| EN | 1.365 (0.589) | 0.032 | - | - | -1.475 (0.582) | 0.020 | - | - | - | - |

| Horvath-1 | 1.751 (0.706) | 0.023 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Horvath-2 | 0.604 (0.264) | 0.034 | - | - | -0.903 (0.261) | 0.002 | 0.310 (0.108) | 0.010 | - | - |

| Levine | 5.078 (1.109) | 0.001 | 8.413 (2.377) | 0.002 | -5.017 (1.205) | 0.001 | - | - | - | - |

| PedBE | 0.356 (0.107) | 0.003 | - | - | -0.314 (0.106) | 0.008 | - | - | - | - |

| Wu | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.816 (0.375) | 0.042 | |

| Zhang | 1.938 (0.660) | 0.008 | - | - | -1.810 (0.691) | 0.016 | - | - | - | - |

| CPG | Gene anotation | Chr | Position | Relation to Island | β | SE | T | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg24772138 | MAP1B (Body) | 5 | 71405539 | S Shore | -0.4483 | 0.0508 | -8.8233 | 4.30 x10-07 |

| cg26028573 | HIST1H2BB (Exon) | 6 | 26043587 | N Shore | 0.2340 | 0.0264 | 8.8374 | 4.22 x10-07 |

| cg05100917 | CEP164 (TSS200) | 11 | 117198460 | Island | -0.5790 | 0.0627 | -9.2343 | 2.48 x10-07 |

| cg20150189 | SULT1C4 (Body) | 2 | 108999219 | Open Sea | -0.3525 | 0.0498 | -7.0718 | 5.58 x10-06 |

| cg27181762 | ADGRV1 (Body) | 5 | 90195345 | Open Sea | -0.5829 | 0.0860 | -6.7701 | 9.02 x10-06 |

| cg13883911 | - | 8 | 33430120 | Open Sea | 0.3104 | 0.0449 | 6.9051 | 7.26 x10-06 |

| cg08523325 | NAALAD2 (Body) | 11 | 89901450 | Open Sea | -0.3064 | 0.0448 | -6.8337 | 8.14 x10-06 |

| cg06583549 | IRF2BP1 (Exon) | 19 | 46387962 | Island | -0.2669 | 0.0350 | -7.6212 | 2.40 x10-06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).