Submitted:

20 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Datasets

2.2. Methylation Quality Control Data Preprocessing and Differential Methylation Analysis

2.3. Age Acceleration Analysis

2.4. Epigenetic Drift and Stochastic Epigenetic Mutations Analysis (SEMs)

2.5. Epigenetic Variation Analysis

2.6. Meta-Analysis

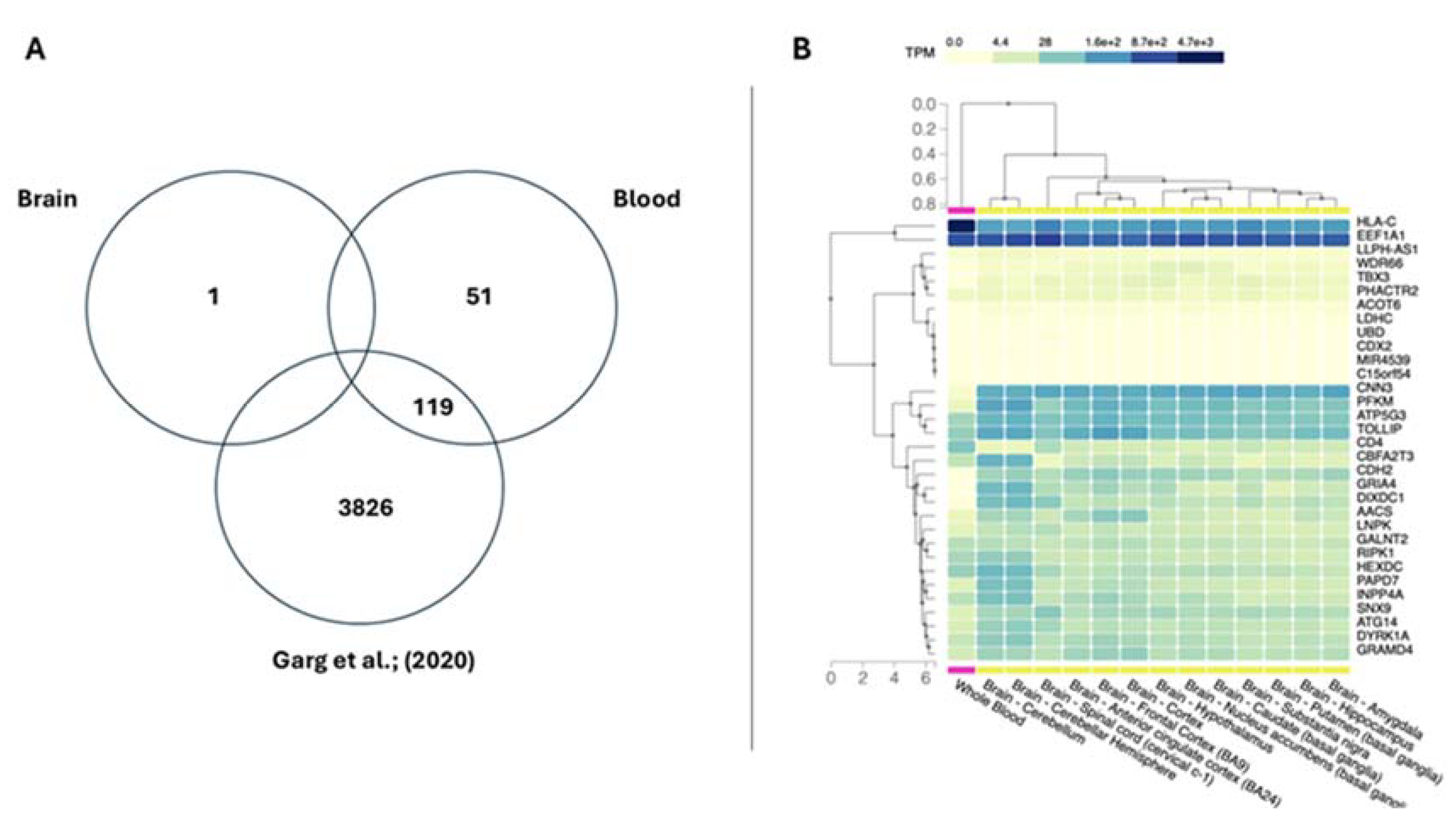

2.7. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis and Gene Prioritization Analysis

3. Results

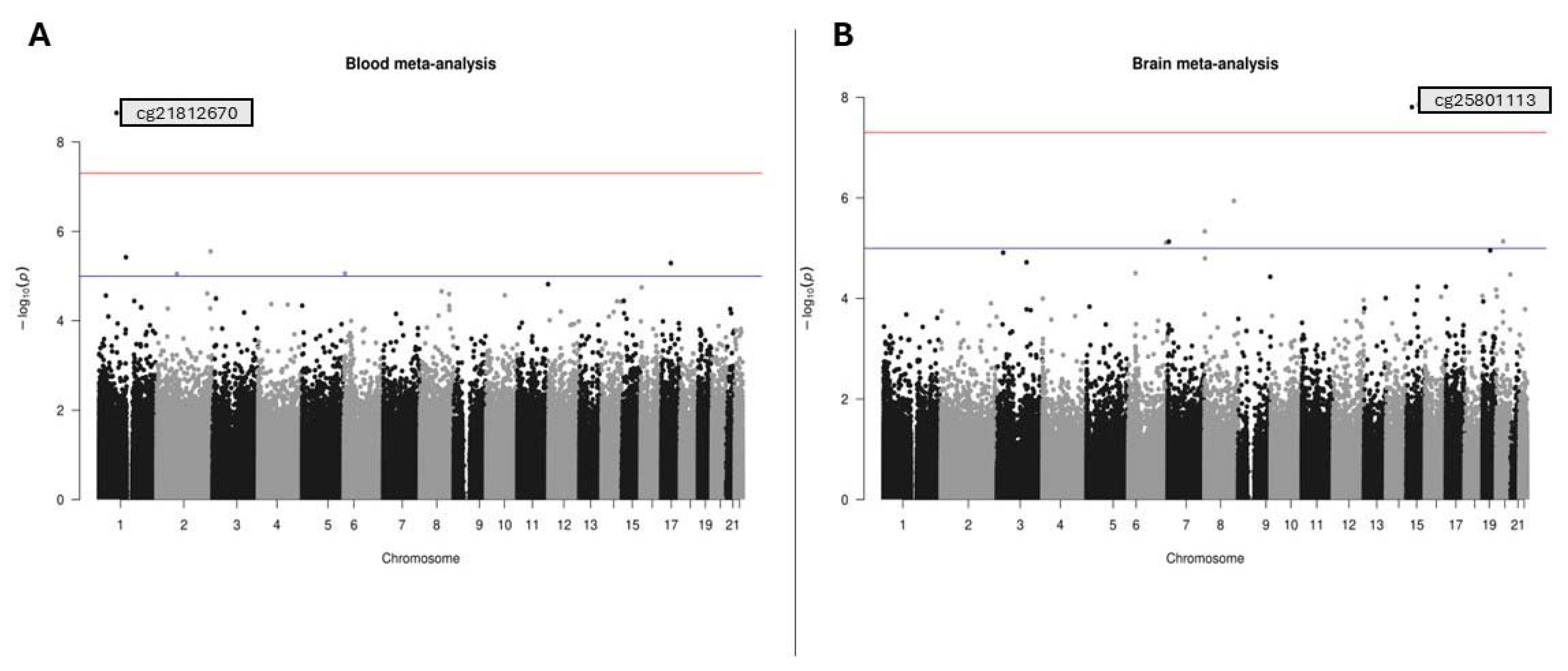

3.1. Datasets and Differential Methylation Meta-Analyses

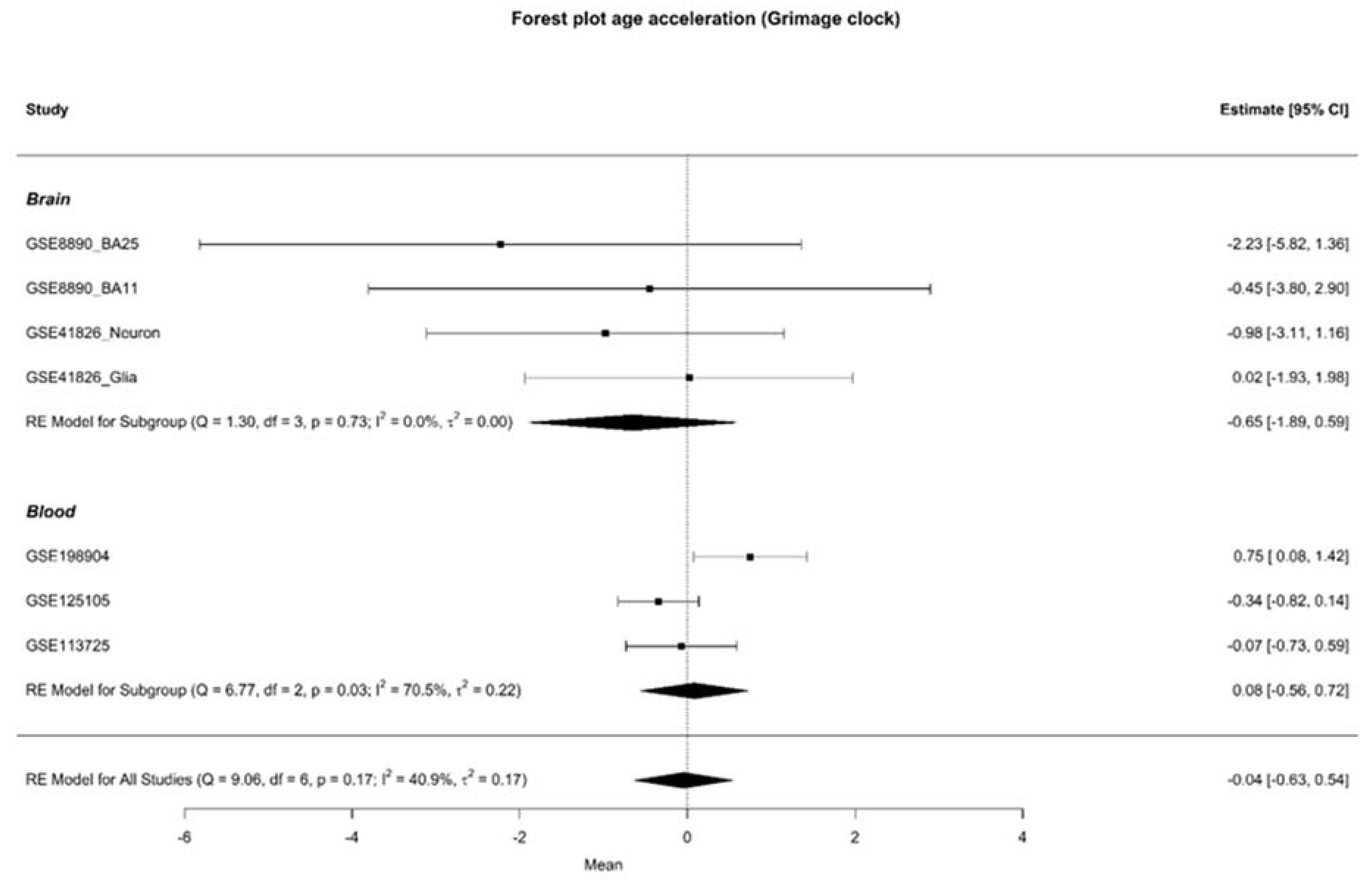

3.2. Age Acceleration

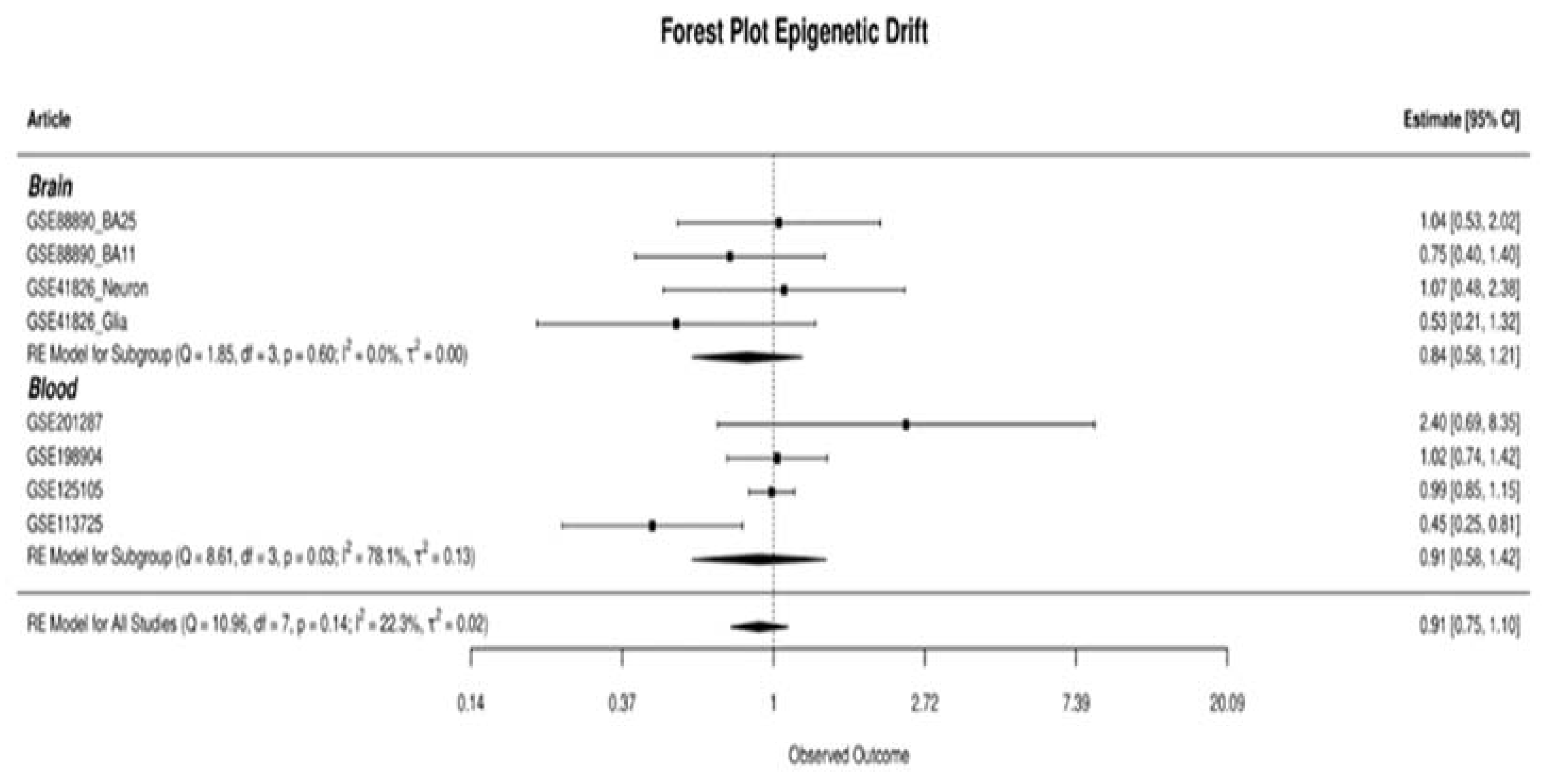

3.3. SEM Analysis and Epimutation Load

3.4. Epigenetic Variation Analysis Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Greenberg, J.; Tesfazion, A.A.; Col, M.;; Robinson, C.S. Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Depression; 2012; Vol. 177.

- Rybak, Y.E.; Lai, K.S.P.; Ramasubbu, R.; Vila-Rodriguez, F.; Blumberger, D.M.; Chan, P.; Delva, N.; Giacobbe, P.; Gosselin, C.; Kennedy, S.H.; et al. Treatment-Resistant Major Depressive Disorder: Canadian Expert Consensus on Definition and Assessment. Depress Anxiety 2021, 38, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, B.; Craig, Z.; Mansell, G.; White, I.; Smith, A.; Spaull, S.; Imm, J.; Hannon, E.; Wood, A.; Yaghootkar, H.; et al. DNA Methylation and Inflammation Marker Profiles Associated with a History of Depression. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27, 2840–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.S.; Morrison, R.L.; Turecki, G.; Drevets, W.C. Meta-Analysis of Epigenome-Wide Association Studies of Major Depressive Disorder. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, J.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Wei, H.; Zhu, C.; Han, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Shen, Y.; Xu, Q.; et al. Elevated BICD2 DNA Methylation in Blood of Major Depressive Disorder Patients and Reduction of Depressive-like Behaviors in Hippocampal Bicd2-Knockdown Mice. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.R.; Halldorsdottir, T.; Martins, J.; Lucae, S.; Müller-Myhsok, B.; Müller, N.S.; Piechaczek, C.; Feldmann, L.; Freisleder, F.J.; Greimel, E.; et al. Sex Differences in the Genetic Regulation of the Blood Transcriptome Response to Glucocorticoid Receptor Activation. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.M.; Crawford, B.; Dempster, E.L.; Hannon, E.; Burrage, J.; Turecki, G.; Kaminsky, Z.; Mill, J. Methylomic Profiling of Cortex Samples from Completed Suicide Cases Implicates a Role for PSORS1C3 in Major Depression and Suicide. Transl Psychiatry 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guintivano, J.; Aryee, M.J.; Kaminsky, Z.A. A Cell Epigenotype Specific Model for the Correction of Brain Cellular Heterogeneity Bias and Its Application to Age, Brain Region and Major Depression. Epigenetics 2013, 8, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.S.; Morrison, R.L.; Turecki, G.; Drevets, W.C. Meta-Analysis of Epigenome-Wide Association Studies of Major Depressive Disorder. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Strachan, E.; Fowler, E.; Bacus, T.; Roy-Byrne, P.; Zhao, J. Genome-Wide Profiling of DNA Methylome and Transcriptome in Peripheral Blood Monocytes for Major Depression: A Monozygotic Discordant Twin Study. Transl Psychiatry 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanova, O.S.; Nedeljkovic, I.; Spieler, D.; Walker, R.M.; Liu, C.; Luciano, M.; Bressler, J.; Brody, J.; Drake, A.J.; Evans, K.L.; et al. DNA Methylation Signatures of Depressive Symptoms in Middle-Aged and Elderly Persons: Meta-Analysis of Multiethnic Epigenome-Wide Studies. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Hossain, S.; Chitrala, K.N.; Tajuddin, S.M.; Beydoun, H.A.; Evans, M.K.; Zonderman, A.B. Association between Epigenetic Age Acceleration and Depressive Symptoms in a Prospective Cohort Study of Urban-Dwelling Adults. J Affect Disord 2019, 257, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, R.; Tanifuji, T.; Okazaki, S.; Otsuka, I.; Shirai, T.; Mouri, K.; Horai, T.; Hishimoto, A. Accelerated Epigenetic Aging and Decreased Natural Killer Cells Based on DNA Methylation in Patients with Untreated Major Depressive Disorder. npj Aging 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, J.L.; Garg, P.; Thin, T.H.; Yoo, S.; Dutta, R.; Trapp, B.D.; Haroutunian, V.; Zhu, J.; Donovan, M.J.; Sharp, A.J.; et al. Epigenome-Wide Differences in Pathology-Free Regions of Multiple Sclerosis-Affected Brains. Nat Neurosci 2014, 17, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.K.M.; Dinga, R.; Hahn, T.; Ching, C.R.K.; Eyler, L.T.; Aftanas, L.; Aghajani, M.; Aleman, A.; Baune, B.T.; Berger, K.; et al. Brain Aging in Major Depressive Disorder: Results from the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5124–5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, C.; Petronis, A. Epigenetic Approaches to Psychiatric Disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2010, 12, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davide, G.; Rebecca, C.; Irene, P.; Luciano, C.; Francesco, R.; Marta, N.; Miriam, O.; Natascia, B.; Pierluigi, P. Epigenetics of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Multi-Level Analysis Combining Epi-Signature, Age Acceleration, Epigenetic Drift and Rare Epivariations Using Public Datasets. Curr Neuropharmacol 2023, 21, 2362–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Morris, T.J.; Webster, A.P.; Yang, Z.; Beck, S.; Feber, A.; Teschendorff, A.E. ChAMP: Updated Methylation Analysis Pipeline for Illumina BeadChips. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3982–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-Sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.E.; Li, C.; Rabinovic, A. Adjusting Batch Effects in Microarray Expression Data Using Empirical Bayes Methods. Biostatistics 2007, 8, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.C.; Breeze, C.E.; Beck, S.; Dong, D.; Zhu, T.; Ma, L.; Ye, W.; Zhang, G.; Teschendorff, A.E. EpiDISH Web Server: Epigenetic Dissection of Intra-Sample-Heterogeneity with Online GUI. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1950–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, C.; Fiorito, G.; Hernandez, B.; Polidoro, S.; O’Halloran, A.M.; Hever, A.; Ni Cheallaigh, C.; Lu, A.T.; Horvath, S.; Vineis, P.; et al. GrimAge Outperforms Other Epigenetic Clocks in the Prediction of Age-Related Clinical Phenotypes and All-Cause Mortality. Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2021, 76, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, H.; Horvath, S. DNA Methylation Age of Human Tissues and Cell Types; 2013; Vol. 14.

- Aging-V7i8-100792.

- Aging-V12i18-103950.

- Chen, P.; Shi, W.; Liu, Y.; Cao, X. Slip Rate Deficit Partitioned by Fault-Fold System on the Active Haiyuan Fault Zone, Northeastern Tibetan Plateau. J Struct Geol 2022, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolaux, R.; Hardy, A.; Olsen, C.; Van Dooren, S.; Smits, G.; Defrance, M. Identification of Differentially Methylated Regions in Rare Diseases from a Single-Patient Perspective. Clin Epigenetics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentilini, D.; Somigliana, E.; Pagliardini, L.; Rabellotti, E.; Garagnani, P.; Bernardinelli, L.; Papaleo, E.; Candiani, M.; Di Blasio, A.M.; Viganò, P. Multifactorial Analysis of the Stochastic Epigenetic Variability in Cord Blood Confirmed an Impact of Common Behavioral and Environmental Factors but Not of in Vitro Conception. Clin Epigenetics 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, E.; Calzari, L.; Corsaro, L.; Fazia, T.; Mencarelli, M.; Di Blasio, A.M.; Bernardinelli, L.; Zangheri, G.; Vignali, M.; Gentilini, D. Epigenome Wide Association and Stochastic Epigenetic Mutation Analysis on Cord Blood of Preterm Birth. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Jadhav, B.; Rodriguez, O.L.; Patel, N.; Martin-Trujillo, A.; Jain, M.; Metsu, S.; Olsen, H.; Paten, B.; Ritz, B.; et al. A Survey of Rare Epigenetic Variation in 23,116 Human Genomes Identifies Disease-Relevant Epivariations and CGG Expansions. Am J Hum Genet 2020, 107, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, D.; Somigliana, E.; Pagliardini, L.; Rabellotti, E.; Garagnani, P.; Bernardinelli, L.; Papaleo, E.; Candiani, M.; Di Blasio, A.M.; Viganò, P. Multifactorial Analysis of the Stochastic Epigenetic Variability in Cord Blood Confirmed an Impact of Common Behavioral and Environmental Factors but Not of in Vitro Conception. Clin Epigenetics 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, C.J.; Li, Y.; Abecasis, G.R. METAL: Fast and Efficient Meta-Analysis of Genomewide Association Scans. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2190–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the Metafor Package; 2010; Vol. 36.

- Aguet, F.; Brown, A.A.; Castel, S.E.; Davis, J.R.; He, Y.; Jo, B.; Mohammadi, P.; Park, Y.S.; Parsana, P.; Segrè, A. V.; et al. Genetic Effects on Gene Expression across Human Tissues. Nature 2017, 550, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, G.; Plaschkes, I.; Oz-Levi, D.; Alkelai, A.; Olender, T.; Zimmerman, S.; Twik, M.; Belinky, F.; Fishilevich, S.; Nudel, R.; et al. VarElect: The Phenotype-Based Variation Prioritizer of the GeneCards Suite. BMC Genomics 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, G.R.; Saldana, V.A.; Finnstein, J.; Rein, T. Molecular Pathways of Major Depressive Disorder Converge on the Synapse. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, G.R.; Saldana, V.A.; Finnstein, J.; Rein, T. Molecular Pathways of Major Depressive Disorder Converge on the Synapse. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond RK, Pahl MC, Su C, Cousminer DL, Leonard ME, Lu S, Doege CA, Wagley Y, Hodge KM, Lasconi C, Johnson ME, Pippin JA, Hankenson KD, Leibel RL, Chesi A, Wells AD, Grant SF. Biological constraints on GWAS SNPs at suggestive significance thresholds reveal additional BMI loci. Elife. 2021 Jan 18;10:e62206. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi-Kabata, Y.; Morihara, T.; Ohara, T.; Ninomiya, T.; Takahashi, A.; Akatsu, H.; Hashizume, Y.; Hayashi, N.; Shigemizu, D.; Boroevich, K.A.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Human Genetic Association Study and Mouse Transcriptome Suggests LBH and SHF Genes as Novel Susceptible Genes for Amyloid-β Accumulation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Hum Genet 2018, 137, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, H.Y.; Zhu, J.; Niu, Y.M.; Zhang, C.; Guo, G.L. Identification of Hub Genes and Key Pathways Associated With Bipolar Disorder Based on Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis. Front Physiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Huang, G.; Liu, J.; Ge, J.; Zhang, W.; Mei, Z. An Update on the Role of Hippo Signaling Pathway in Ischemia-Associated Central Nervous System Diseases. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2023, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anacker, C.; Cattaneo, A.; Luoni, A.; Musaelyan, K.; Zunszain, P.A.; Milanesi, E.; Rybka, J.; Berry, A.; Cirulli, F.; Thuret, S.; et al. Glucocorticoid-Related Molecular Signaling Pathways Regulating Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipton, J.O.; Sahin, M. The Neurology of MTOR. Neuron 2014, 84, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iranpanah, A.; Kooshki, L.; Moradi, S.Z.; Saso, L.; Fakhri, S.; Khan, H. The Exosome-Mediated PI3K/Akt/MTOR Signaling Pathway in Neurological Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Voleti, B. Signaling Pathways Underlying the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Depression: Novel Mechanisms for Rapid-Acting Agents. Trends Neurosci 2012, 35, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varea, V.; Martín de Carpi, J.; Puig, C.; Angel Alda, J.; Camacho, E.; Ormazabal, A.; Artuch, R.; Gómez, L. Malabsorption of Carbohydrates and Depression in Children and Adolescents.

- Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Dong, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Gong, Q.; Kuang, W. The Digestion and Dietary Carbohydrate Pathway Contains 100% Gene Mutations Enrichment among 117 Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusati, A.; Peverelli, S.; Calzari, L.; Tiloca, C.; Casiraghi, V.; Sorce, M.N.; Invernizzi, S.; Carbone, E.; Cavagnola, R.; Verde, F.; et al. Exploring Epigenetic Drift and Rare Epivariations in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis by Epigenome-Wide Association Study. Front Aging Neurosci 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Cheng, Z.; Bass, N.; Krystal, J.H.; Farrer, L.A.; Kranzler, H.R.; Gelernter, J. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Glutamate Ionotropic Receptor GRIA4 as a Risk Gene for Comorbid Nicotine Dependence and Major Depression. Transl Psychiatry 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiesa, A.; Crisafulli, C.; Porcelli, S.; Han, C.; Patkar, A.A.; Lee, S.J.; Park, M.H.; Jun, T.Y.; Serretti, A.; Pae, C.U. Influence of GRIA1, GRIA2 and GRIA4 Polymorphisms on Diagnosis and Response to Treatment in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012, 262, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarny, P.; Białek, K.; Ziółkowska, S.; Strycharz, J.; Barszczewska, G.; Sliwinski, T. The Importance of Epigenetics in Diagnostics and Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J Pers Med 2021, 11, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Ma, H.; Gao, M.; Chen, A.; Zha, S.; Yan, J. Long Non-Coding RNA GAS5 Aggravates Myocardial Depression in Mice with Sepsis via the MicroRNA-449b/HMGB1 Axis and the NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway. Biosci Rep 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilmer, M.; Edmondson, A.C.; Khetarpal, S.A.; Alesi, V.; Zaki, M.S.; Rostasy, K.; Madsen, C.G.; Lepri, F.R.; Sinibaldi, L.; Cusmai, R.; et al. Novel Congenital Disorder of O-Linked Glycosylation Caused by GALNT2 Loss of Function. Brain 2020, 143, 1114–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GSE Accession |

Tissue | Number of cases | Number of controls | Array Type | Country | Publication Year | Study DOI |

| GSE113725 [3] | Blood | 48 | 48 | Illumina 450K | UK | 2018 | 10.1093/hmg/ddy199 |

| GSE198904 [4] | Blood | 548 | 100 | Illumina 850K | USA | 2022 | 10.1038/s41598-022-22744-6 |

| GSE201287 [5] | Blood | 40 | 40 | Illumina 450K | China | 2022 | 10.1073/pnas.2201967119 |

| GSE125105 [6] | Blood | 489 | 210 | Illumina 450K | Germany | 2019 | 10.1038/s41398-021-01756-2 |

| GSE88890(BA2) [7] | Brain | 17 | 18 | Illumina 450K | UK | 2017 | 10.1038/tp.2016.249 |

| GSE88890(BA11) [7] | Brain | 20 | 20 | Illumina 450K | UK | 2017 | 10.1038/tp.2016.249 |

| GSE41826(Glia) [8] | Brain | 29 | 29 | Illumina 450K | USA | 2013 | 10.4161/epi.23924 |

| GSE41826(Neuron) [8] | Brain | 29 | 29 | Illumina 450K | USA | 2013 | 10.4161/epi.23924 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).