Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

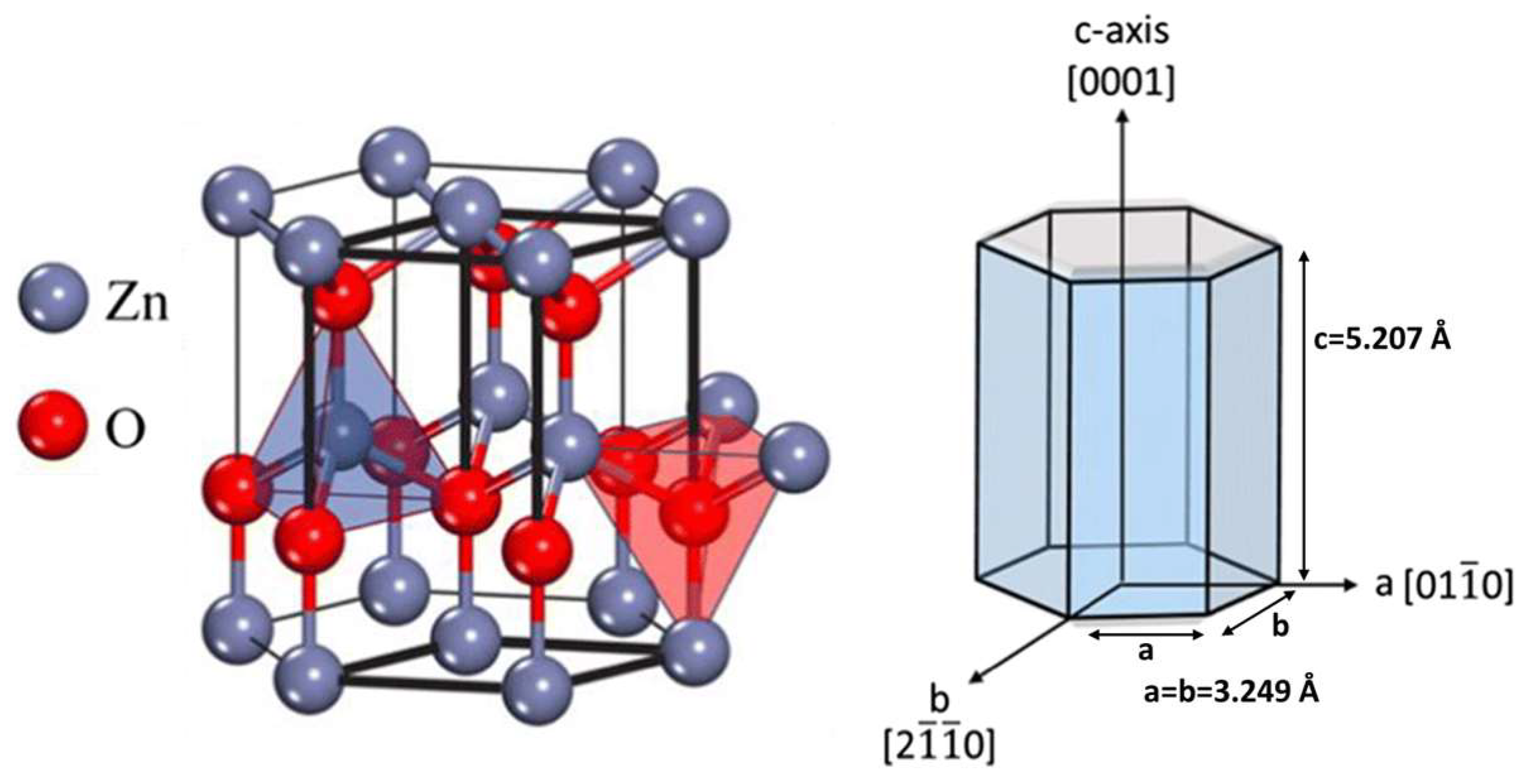

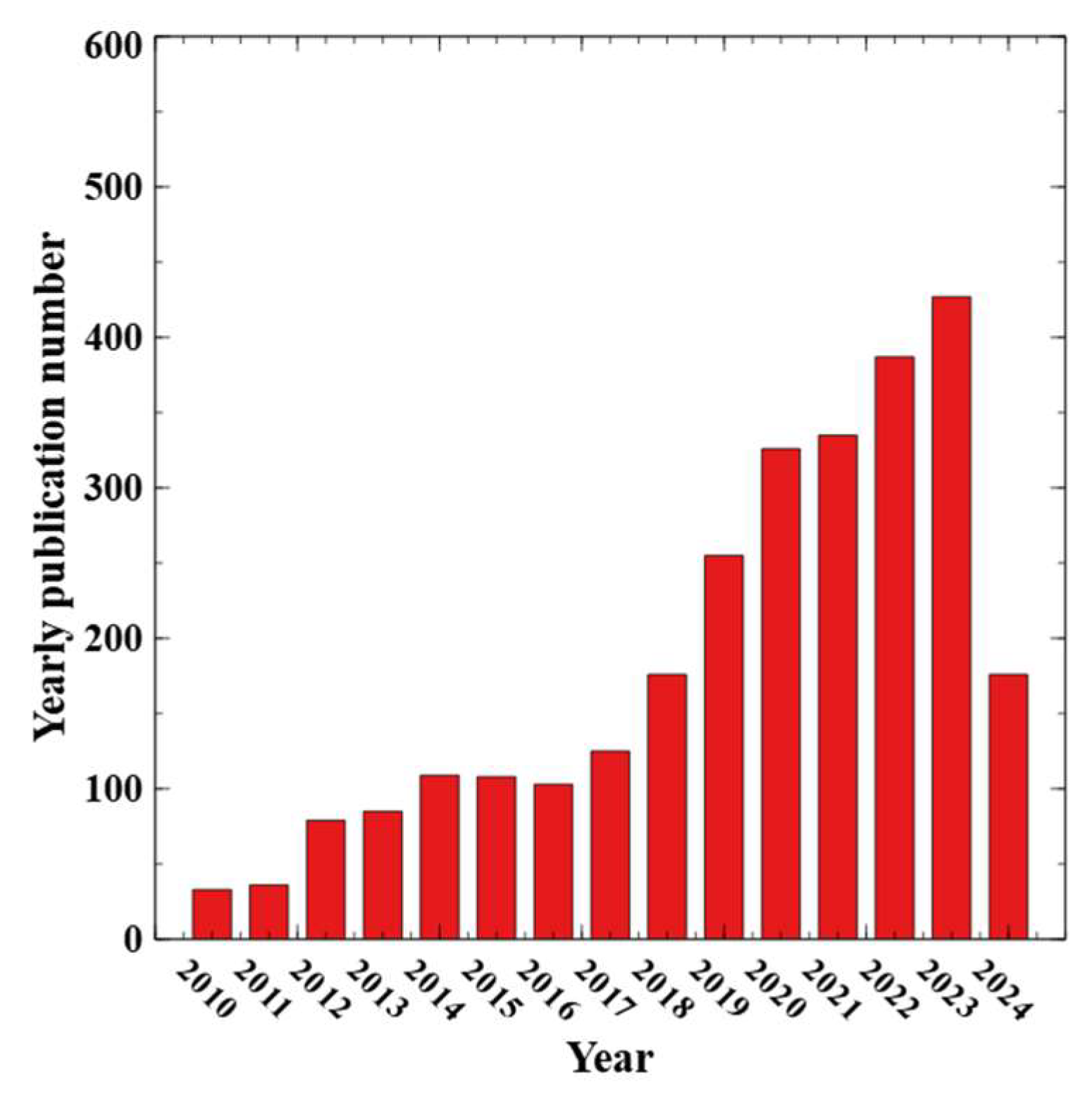

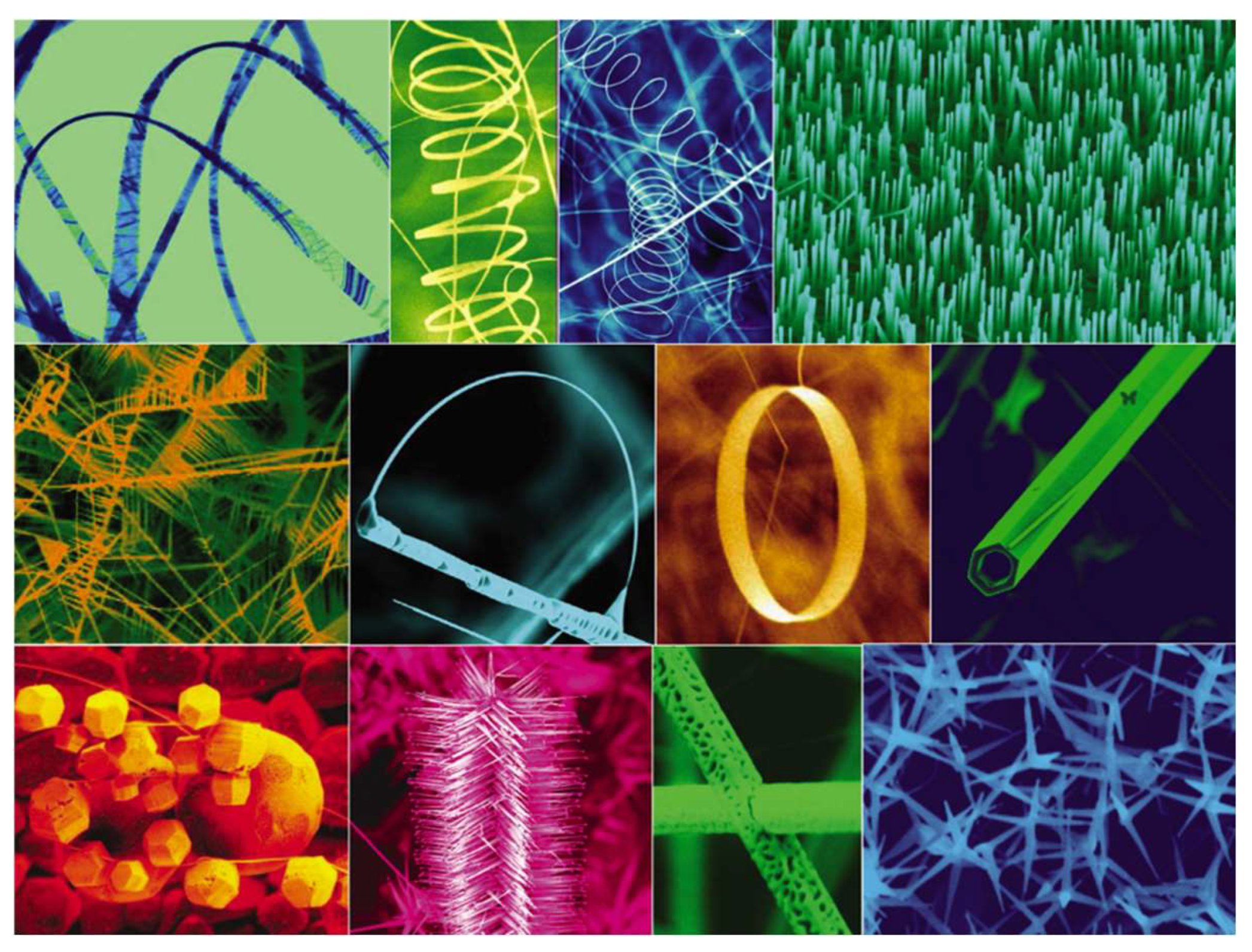

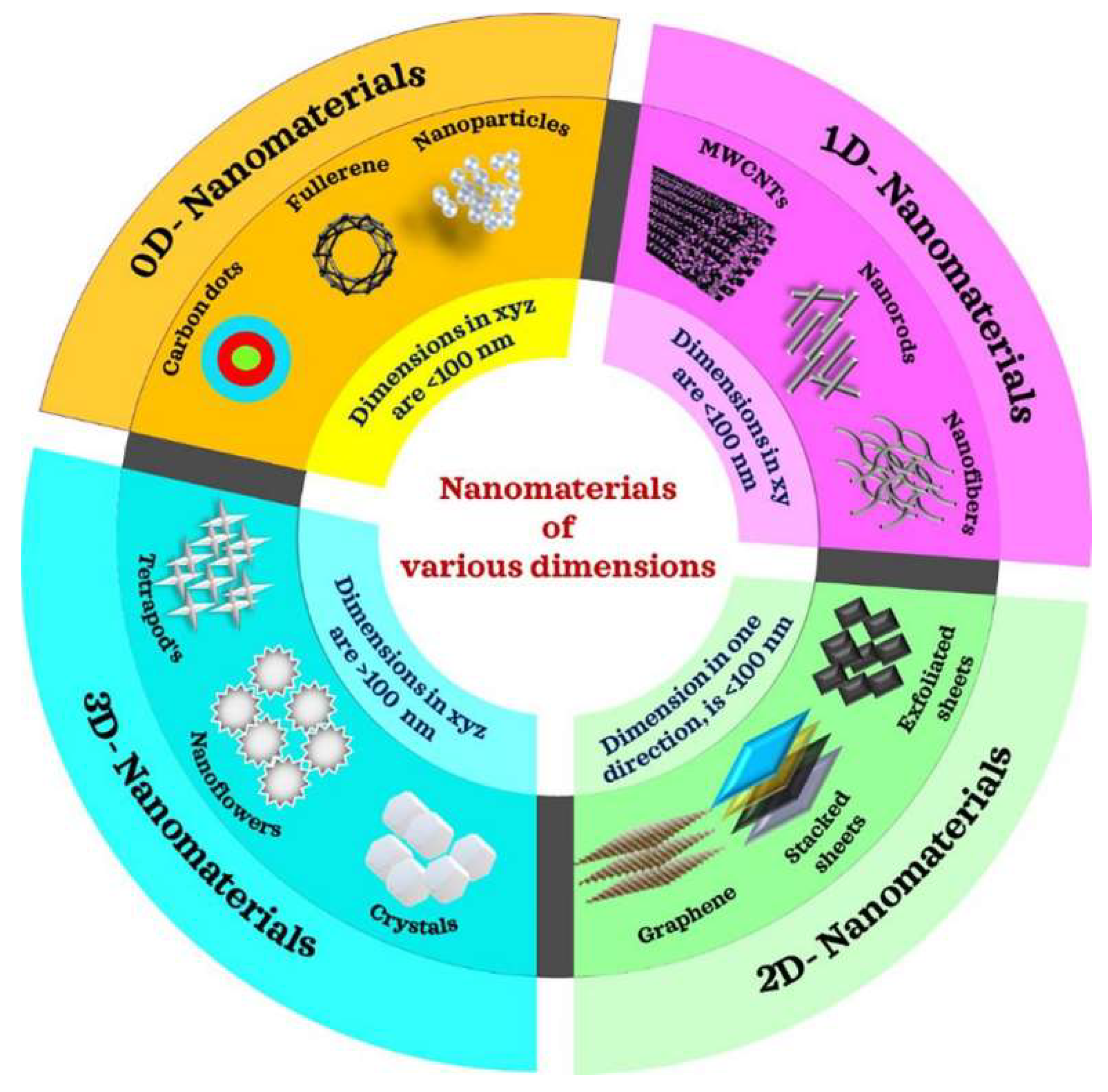

1. Introduction

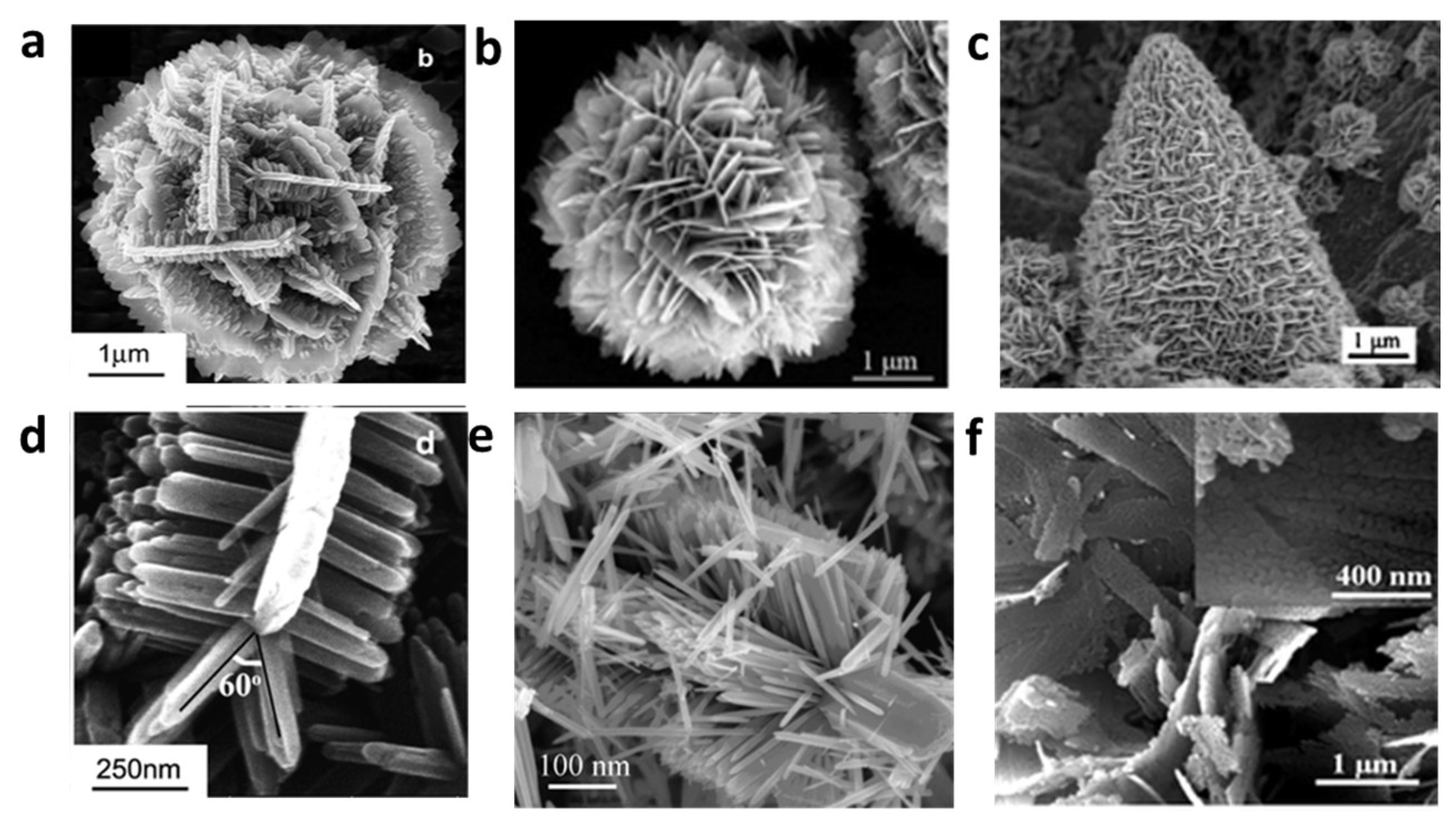

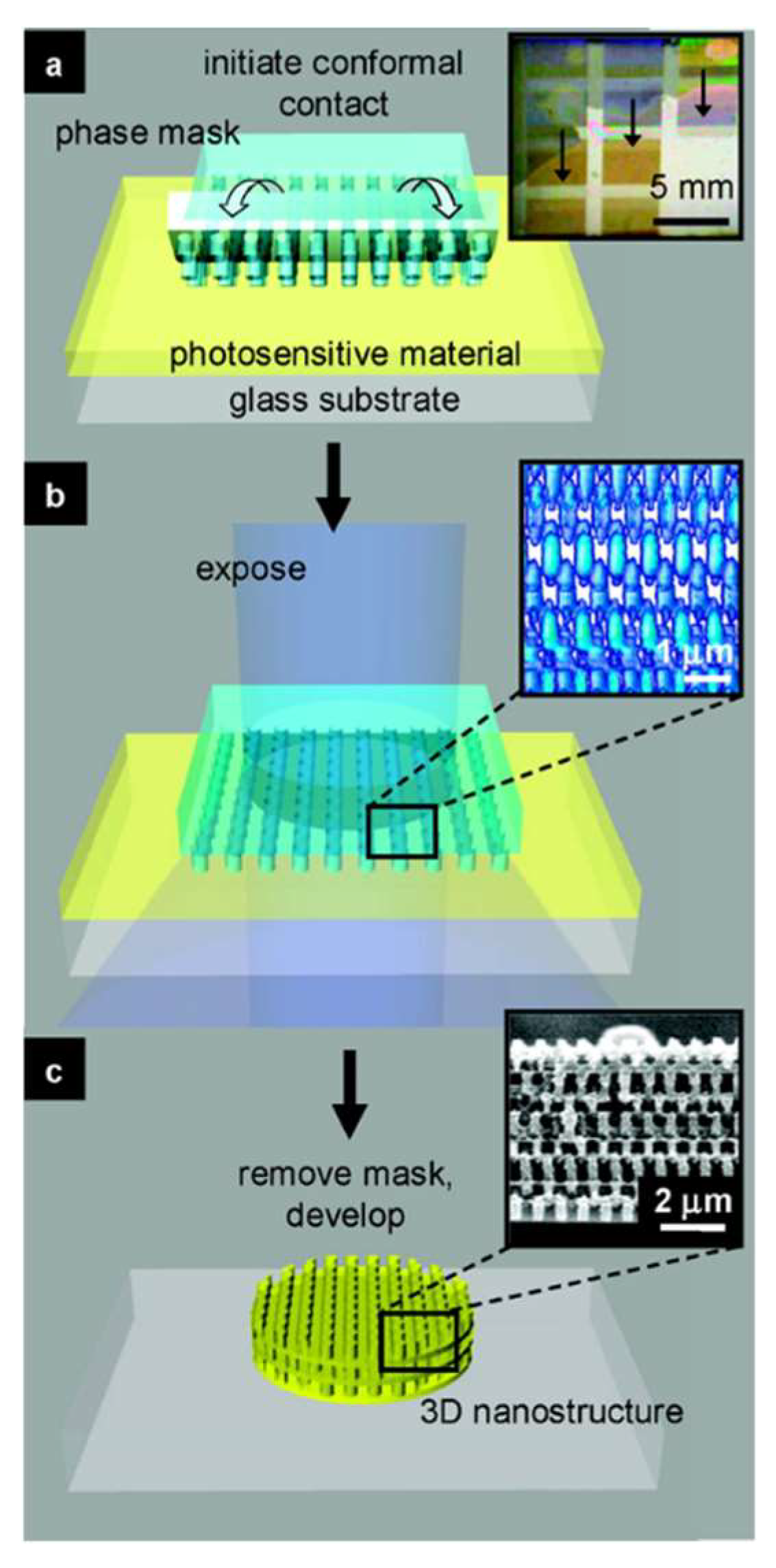

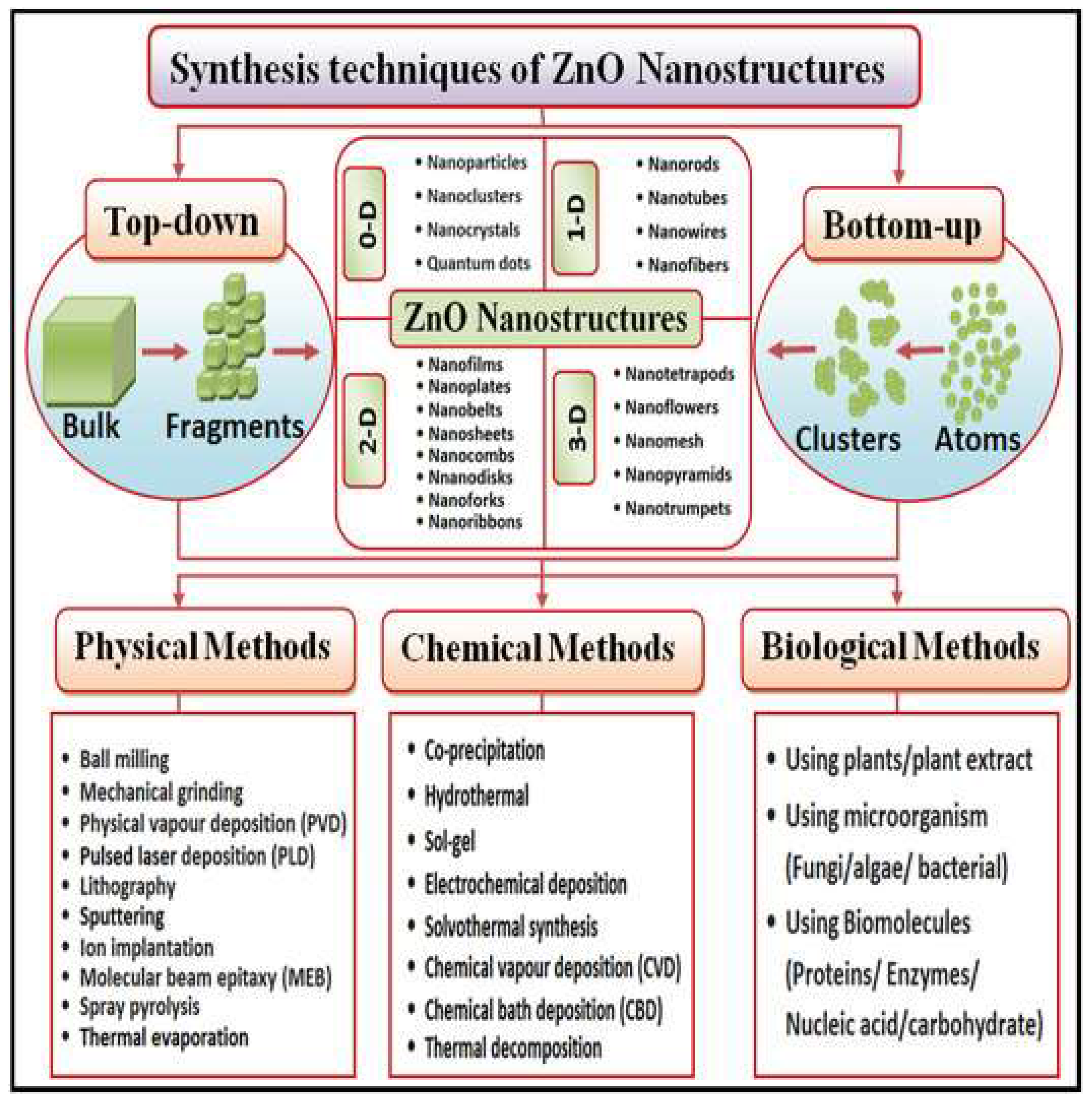

2. ZnO Nanostructure Synthesis

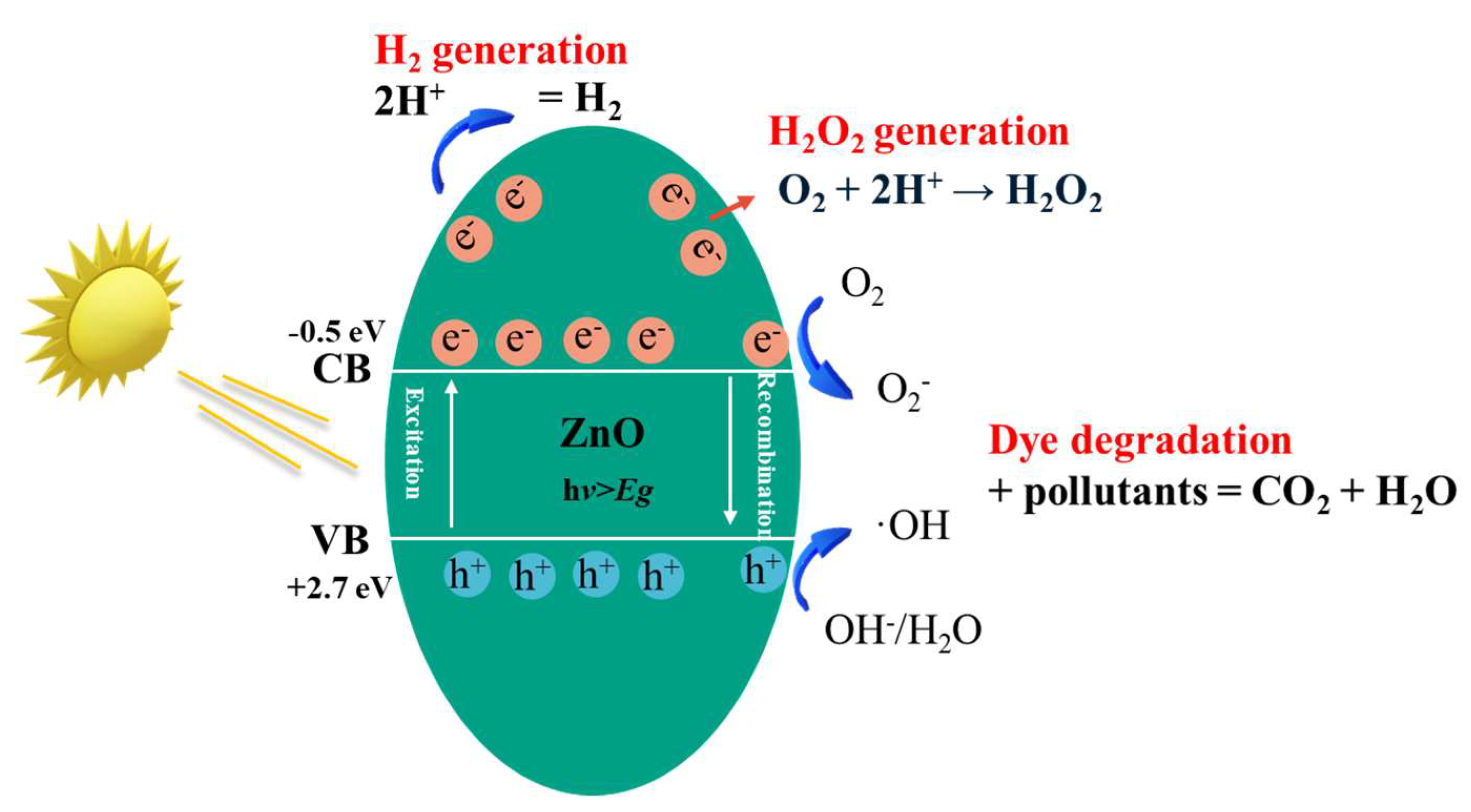

3. Mechanism of ZnO Photocatalysis

4. Photocatalytic Applications of ZnO

4.1. Wastewater Treatment

4.2. Air Purification

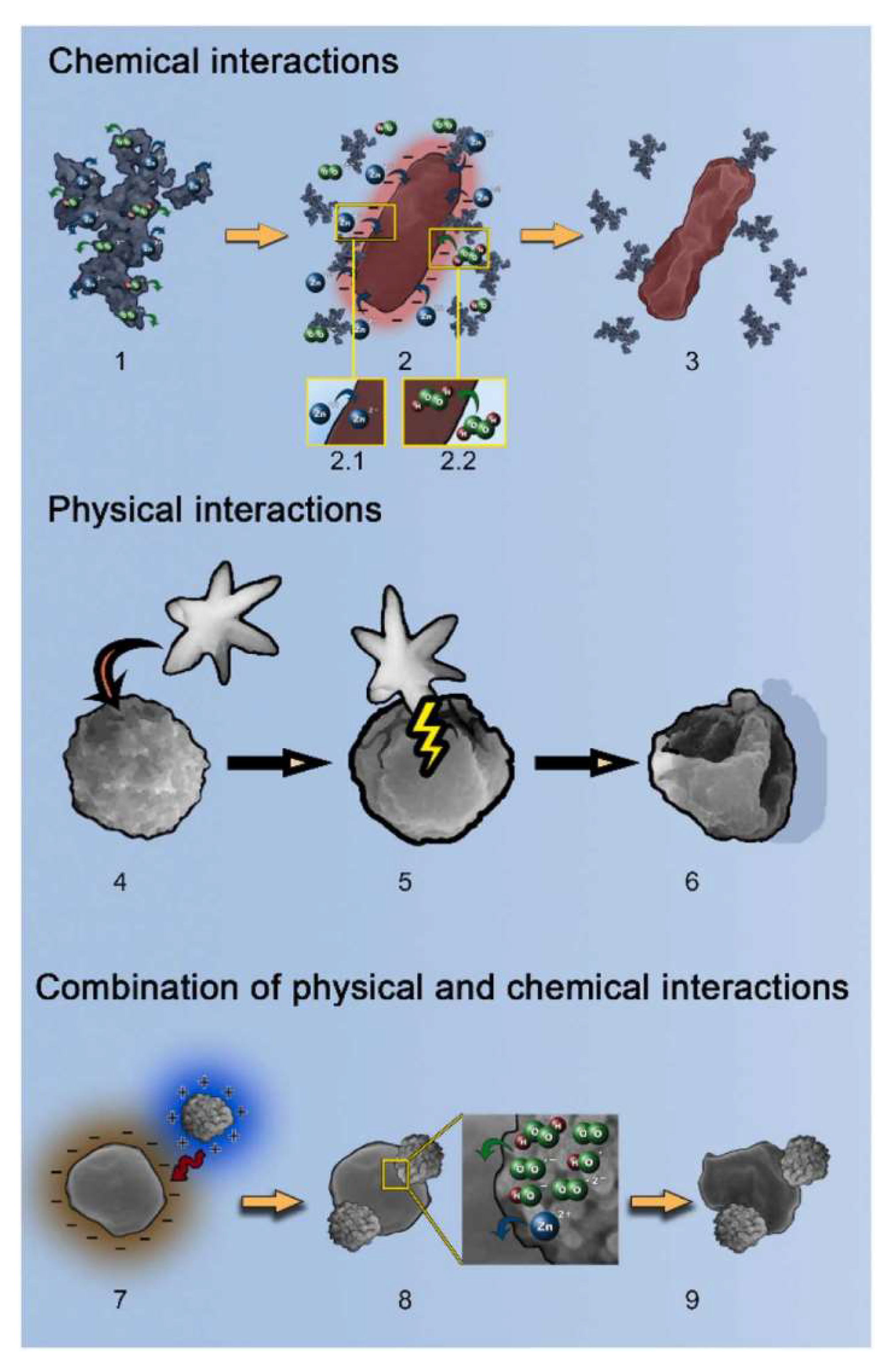

4.3. Antimicrobial Application

4.4. Other Applications

4.5. Strategies for ZnO Photocatalytic Performance Enhancement

5. Discussion of Current Challenges and Future Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, B.; Sun, J.; Salahuddin, U.; Gao, P.-X. Hierarchical and Scalable Integration of Nanostructures for Energy and Environmental Applications: A Review of Processing, Devices, and Economic Analyses. Nano Futures 2020, 4, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, P.-X. Metal Oxide Nanoarrays for Chemical Sensing: A Review of Fabrication Methods, Sensing Modes, and Their Inter-Correlations. Front Mater 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sun, J.; Gao, P. Single Bimodular Sensor for Differentiated Detection of Multiple Oxidative Gases. Adv Mater Technol 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sun, J.Y.; Gao, P.X. Low-Concentration NOx Gas Analysis Using Single Bimodular ZnO Nanorod Sensor. ACS Sens 2021, 6, 2979–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Marsudi, M.A.; Amal, M.I.; Ananda, M.B.; Stephanie, R.; Ardy, H.; Diguna, L.J. ZnO Nanostructured Materials for Emerging Solar Cell Applications. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 42838–42859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ti, J.; Li, J.; Fan, Q.; Ren, W.; Yu, Q.; Wang, C. Magnetron Sputtering of ZnO Thick Film for High Frequency Focused Ultrasonic Transducer. J Alloys Compd 2023, 933, 167764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Shan, L.; Lin, Z.; Wan, B.; Yang, B.; Zeng, X.; Yang, B.; Pelenovich, V. Dual-Wave ZnO Film Ultrasonic Transducers for Temperature and Stress Measurements. Sensors 2024, 24, 5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka Boruah, B. Zinc Oxide Ultraviolet Photodetectors: Rapid Progress from Conventional to Self-Powered Photodetectors. Nanoscale Adv 2019, 1, 2059–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Li, J.; Huang, K.; Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Z.; Mei, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, N.; et al. Low-Temperature and Solution-Processable Zinc Oxide Transistors for Transparent Electronics. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8990–8996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, F.; Salahuddin, U.; Wu, M.; Zhu, C.; Lu, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, B.; Xie, Z.; Ding, Y.; et al. Optimization and Understanding of ZnO Nanoarray Supported Cu-ZnO-Al2O3 Catalyst for Enhanced CO2 -Methanol Conversion at Low Temperature and Pressure. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Du, S.; Wang, S.; Lu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, B.; Liu, F.; Xiao, W.; Guo, Y.; Ding, J.; et al. PGM-Free Metal Oxide Nanoarray Forests for Water-Promoted Low-Temperature Soot Oxidation. Appl Catal B 2024, 341, 123336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.S. The Role of Zinc Oxide in Cu/ZnO Catalysts for Methanol Synthesis and the Water-Gas Shift Reaction. Top Catal 1999, 8, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raha, S.; Ahmaruzzaman, M. ZnO Nanostructured Materials and Their Potential Applications: Progress, Challenges and Perspectives. Nanoscale Adv 2022, 4, 1868–1925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Hasan, M.R.; Mehto, N.K. ; Deepak; Bishoyi, A.; Narang, J. 92 Years of Zinc Oxide: Has Been Studied by the Scientific Community since the 1930s- An Overview. Sensors International.

- Samadi, M.; Zirak, M.; Naseri, A.; Khorashadizade, E.; Moshfegh, A.Z. Recent Progress on Doped ZnO Nanostructures for Visible-Light Photocatalysis. Thin Solid Films 2016, 605, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Tang, W.; Du, S.; Wen, L.; Weng, J.; Ding, Y.; Willis, W.S.; Suib, S.L.; Gao, P.X. Ion-Exchange Loading Promoted Stability of Platinum Catalysts Supported on Layered Protonated Titanate-Derived Titania Nanoarrays. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Dang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhu, C.; Liu, F.; Tang, W.; Weng, J.; Ruan, M.; Suib, S.L.; Gao, P.X. Synergistic Promotion of Transition Metal Ion-Exchange in TiO2 Nanoarray-Based Monolithic Catalysts for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3. Catal Sci Technol 2022, 12, 5397–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkten, N.; Bekbolet, M. Photocatalytic Performance of Titanium Dioxide and Zinc Oxide Binary System on Degradation of Humic Matter. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem 2020, 401, 112748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Robertson, J.M.C.; Héquet, V.; Chazarenc, F.; Pang, X.; Ralphs, K.; Skillen, N.; Robertson, P.K.J. Comparison of Titanium Dioxide and Zinc Oxide Photocatalysts for the Inactivation of Escherichia Coli in Water Using Slurry and Rotating-Disk Photocatalytic Reactors. Ind Eng Chem Res 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbreders, V.; Krasovska, M.; Sledevskis, E.; Gerbreders, A.; Mihailova, I.; Tamanis, E.; Ogurcovs, A. Hydrothermal Synthesis of ZnO Nanostructures with Controllable Morphology Change. CrystEngComm 2020, 22, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysiewicz, M.A. ZnO as a Functional Material, a Review. Crystals (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Nanostructures of Zinc Oxide. Materials Today 2004, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.; Gupta, S.; Siddiqui, I.; Lin, W.-Z.; Sharma, D.; Ranjan, A.; Tai, N.-H.; Lu, M.-Y.; Jou, J.-H. 0, 1, 2, and 3-Dimensional Zinc Oxides Enabling High-Efficiency OLEDs. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 495, 153220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, T.; Liang, Y.; Huo, Z.; Yang, F. Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Applications in Enhancing Plant Stress Resistance: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Mohanty, D. lochan; Divya, N.; Bakshi, V.; Mohanty, A.; Rath, D.; Das, S.; Mondal, A.; Roy, S.; Sabui, R. A Critical Review on Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Properties and Biomedical Applications. Intelligent Pharmacy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirelkhatim, A.; Mahmud, S.; Seeni, A.; Kaus, N.H.M.; Ann, L.C.; Bakhori, S.K.M.; Hasan, H.; Mohamad, D. Review on Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Antibacterial Activity and Toxicity Mechanism. Nanomicro Lett 2015, 7, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udom, I.; Ram, M.K.; Stefanakos, E.K.; Hepp, A.F.; Goswami, D.Y. One Dimensional-ZnO Nanostructures: Synthesis, Properties and Environmental Applications. Mater Sci Semicond Process 2013, 16, 2070–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Yan, H.; Mao, S.; Russo, R.; Johnson, J.; Saykally, R.; Morris, N.; Pham, J.; He, R.; Choi, H.-J. Controlled Growth of ZnO Nanowires and Their Optical Properties. Adv Funct Mater 2002, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, Q.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, Z.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, Y. Interface Engineering in 1D ZnO-Based Heterostructures for Photoelectrical Devices. Adv Funct Mater 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, B.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Deng, Y. Solution Synthesis of One-Dimensional ZnO Nanomaterials and Their Applications. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumen, A.; Kaur, N.; Poli, N.; Zappa, D.; Comini, E. One Dimensional ZnO Nanostructures: Growth and Chemical Sensing Performances. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Katiyar, A. Zinc Oxide Nanostructures. In Ceramic Science and Engineering; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 235–262.

- Patil, S.A.; Jagdale, P.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, R.V.; Khan, Z.; Samal, A.K.; Saxena, M. 2D Zinc Oxide – Synthesis, Methodologies, Reaction Mechanism, and Applications. Small 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthi, V.; Ahmed, T.; Mohiuddin, M.; Zavabeti, A.; Pillai, N.; McConville, C.F.; Mahmood, N.; Walia, S. A Visible-Blind Photodetector and Artificial Optoelectronic Synapse Using Liquid-Metal Exfoliated ZnO Nanosheets. Adv Opt Mater 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, Z. The Preparation of Spiral ZnO Nanostructures by Top-down Wet-Chemical Etching and Their Related Properties. J Mater Chem 2012, 22, 10924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Ding, A.; Cheng, W.; Zheng, X.; Qiu, P. Two-Dimensional Zinc Oxide Nanostructure. Solid State Commun 2005, 134, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.J.; Scholz, R.; Kolb, F.M.; Zacharias, M. Two-Dimensional Dendritic ZnO Nanowires from Oxidation of Zn Microcrystals. Appl Phys Lett 2004, 85, 4142–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, L.; Ye, J. Preparation and Characterization of 2D ZnO Nanosheets/Regenerated Cellulose Photocatalytic Composite Thin Films by a Two-Step Synthesis Method. Mater Lett 2019, 234, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Cheng, X.; Gao, S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Huo, L. Highly Selective Detection of Saturated Vapors of Abused Drugs by ZnO Nanorod Bundles Gas Sensor. Appl Surf Sci 2019, 485, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cao, K.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, L. 3D Hierarchical Porous ZnO/ZnCo 2 O 4 Nanosheets as High-Rate Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J Mater Chem A Mater 2016, 4, 6042–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ahmad, M.; Sun, H. Three-Dimensional ZnO Hierarchical Nanostructures: Solution Phase Synthesis and Applications. Materials 2017, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Zhou, D.; Xiang, L. A Review on the Fabrication of Hierarchical ZnO Nanostructures for Photocatalysis Application. Crystals (Basel) 2016, 6, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, T.; Du, Z.; Chen, S.; He, H.; Shen, X.; Fu, Y. Preparation of Flower-like ZnO Photocatalyst with Oxygen Vacancy to Enhance the Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange. Appl Surf Sci 2023, 614, 156240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M.R.; Henley, S.J.; Emerson, N.G.; Silva, S.R.P. From 1D and 2D ZnO Nanostructures to 3D Hierarchical Structures with Enhanced Gas Sensing Properties. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, N.; Ahmad, H.; Yasin, M. Bottom-up Self-Assembly of Macroporous ZnO Nanostructures for Photovoltaic Applications. Ceram Int 2023, 49, 26994–27002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Cai, W.; Zhang, Y. ZnO Hierarchical Micro/Nanoarchitectures: Solvothermal Synthesis and Structurally Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. Adv Funct Mater 2008, 18, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.-F.; Sun, L.-D.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Z.-G.; Yan, C.-H. Hierarchical Construction of ZnO Architectures Promoted by Heterogeneous Nucleation. Cryst Growth Des 2008, 8, 3609–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H. Rapid and Simple Synthesis of 3D ZnO Microflowers at Room Temperature. Mater Lett 2015, 158, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Xiang, Q.; Li, H.; Pan, Q.; Xu, P. Brush-Like Hierarchical ZnO Nanostructures: Synthesis, Photoluminescence and Gas Sensor Properties. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2009, 113, 3430–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, H.; Jia, X. Multilayered ZnO Nanosheets with 3D Porous Architectures: Synthesis and Gas Sensing Application. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2010, 114, 14684–14691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakarndee, S.; Nanan, S. SDS Capped and PVA Capped ZnO Nanostructures with High Photocatalytic Performance toward Photodegradation of Reactive Red (RR141) Azo Dye. J Environ Chem Eng 2018, 6, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Bao, L.; Yin, Z.; Ji, X. Heparin-Mediated Growth of Self-Organized ZnO Quasi-Microspheres with Twinned Donut-Like Hierarchical Structures. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 7805–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shir, D.J.; Jeon, S.; Liao, H.; Highland, M.; Cahill, D.G.; Su, M.F.; El-Kady, I.F.; Christodoulou, C.G.; Bogart, G.R.; Hamza, A. V.; et al. Three-Dimensional Nanofabrication with Elastomeric Phase Masks. J Phys Chem B 2007, 111, 12945–12958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Bae, T.-H.; Cho, D.; Choi, M.; Bae, G.; Shim, Y.-S.; Jeon, S. 3D ZnO/ZIF-8 Hierarchical Nanostructure for Sensitive and Selective NO 2 Sensing at Room Temperature. Small Struct 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubío, C.R.; Guitián, F.; Gil, A. Fabrication of ZnO Periodic Structures by 3D Printing. J Eur Ceram Soc 2016, 36, 3409–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Hu, Y.-L.; Pelligra, C.; Chen, C.-H.; Jin, L.; Huang, H.; Sithambaram, S.; Aindow, M.; Joesten, R.; Suib, S.L. ZnO with Different Morphologies Synthesized by Solvothermal Methods for Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. Chemistry of Materials 2009, 21, 2875–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-K.; Chuang, M.-H.; Chen, Y.-C.; Wu, C.-H. Synthesis of 1D, 2D, and 3D ZnO Polycrystalline Nanostructures Using the Sol-Gel Method. J Nanotechnol 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Liu, F.; Dang, Y.; Li, M.; Ruan, M.; Wu, M.; Zhu, C.; Mani, T.; Suib, S.L.; Gao, P.-X. Transition-Metal Doped Titanate Nanowire Photocatalysts Boosted by Selective Ion-Exchange Induced Defect Engineering. Appl Surf Sci 2022, 591, 153116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamarpoor, R.; Fallah, A.; Jamshidi, M. A Review of Synthesis Methods, Modifications, and Mechanisms of ZnO/TiO2-Based Photocatalysts for Photodegradation of Contaminants. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25457–25492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzaee, N.A.; Betti, N.; Al-Amiery, A.; Roslam Wan Isahak, W.N. The Role of Tin Species in Doped Iron (III) Oxide for Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange Dye under UV Light. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ola, O.; Maroto-Valer, M.M. Review of Material Design and Reactor Engineering on TiO2 Photocatalysis for CO2 Reduction. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C: Photochemistry Reviews 2015, 24, 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaković, S.J.; Savanović, M.M.; Armaković, S. Titanium Dioxide as the Most Used Photocatalyst for Water Purification: An Overview. Catalysts 2022, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, A.; Roy, S. A Review of Photocatalysis, Basic Principles, Processes, and Materials. Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment 2024, 8, 100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.B.; Ng, L.Y.; Mohammad, A.W. A Review of ZnO Nanoparticles as Solar Photocatalysts: Synthesis, Mechanisms and Applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 81, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, K.M.; Benitto, J.J.; Vijaya, J.J.; Bououdina, M. Recent Advances in ZnO-Based Nanostructures for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Hazardous, Non-Biodegradable Medicines. Crystals (Basel) 2023, 13, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wageh, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Yu, J.; Wang, L. S-Scheme ZnO/WO3 Heterojunction Photocatalyst for Efficient H2O2 Production. J Mater Sci Technol 2022, 124, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagareh, M.I.; Hafeez, H.Y.; Mohammed, J.; Kafadi, A.D.G.; Suleiman, A.B.; Ndikilar, C.E. Current Trends and Future Perspectives on ZnO-Based Materials for Robust and Stable Solar Fuel (H2) Generation. Chemical Physics Impact 2024, 9, 100774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Preparations and Applications of Zinc Oxide Based Photocatalytic Materials. Advanced Sensor and Energy Materials 2023, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Height, M.J.; Pratsinis, S.E.; Mekasuwandumrong, O.; Praserthdam, P. Ag-ZnO Catalysts for UV-Photodegradation of Methylene Blue. Appl Catal B 2006, 63, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, S.; Choudhary, V.; Satpati, B.; Mohapatra, S. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Ag–ZnO Hybrid Plasmonic Nanostructures Prepared by a Facile Wet Chemical Method. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology 2014, 5, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, D.; Liu, J.; He, L.; Tang, M.; Feng, W.; Wu, X. Fabrication, Characterization and High Photocatalytic Activity of Ag–ZnO Heterojunctions under UV-Visible Light. RSC Adv 2021, 11, 27257–27266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, H.M.; Alenezi, J.F.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Yasin, A.S.; Hashem, A.-F.M.; Abdal-hay, A. Synthesis of TiO2@ZnO Heterojunction for Dye Photodegradation and Wastewater Treatment. J Alloys Compd 2021, 886, 161169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, H.M.; Aroosh, K.; Meng, D.; Ruan, X.; Akhter, M.; Cui, X. A Review on Modified ZnO to Address Environmental Challenges through Photocatalysis: Photodegradation of Organic Pollutants. Mater Today Energy 2025, 48, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Basnet, P.; Mukherjee, J. ZnO Based Nanomaterials for Photocatalytic Degradation of Aqueous Pharmaceutical Waste Solutions – A Contemporary Review. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag 2020, 14, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikanika; Chopra, L. Photocatalytic Activity of Zinc Oxide for Dye and Drug Degradation: A Review. Mater Today Proc 2022, 52, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.T.; Pung, S.-Y.; Sreekantan, S.; Matsuda, A.; Huynh, D.P. Mechanisms of Removal of Heavy Metal Ions by ZnO Particles. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.S.; Zhang, N.; Tang, Z.R.; Anpo, M.; Xu, Y.J. Tip-Grafted Ag-ZnO Nanorod Arrays Decorated with Au Clusters for Enhanced Photocatalysis. Catal Today 2020, 340, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, V.; Kondal, N. ZnO Nanoadsorbents: A Potent Material for Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Wastewater. Colloid Interface Sci Commun 2021, 41, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Yang, A.; Huang, G.; Zhou, X.; Zhai, Y.; Chen, X.; McBean, E. Treatment of Aquaculture Wastewater through Chitin/ZnO Composite Photocatalyst. Water (Basel) 2019, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavisi, Y.; Sharifnia, S.; Mohamadi, Z. Solar-Light-Harvesting Degradation of Aqueous Ammonia by CuO/ZnO Immobilized on Pottery Plate: Linear Kinetic Modeling for Adsorption and Photocatalysis Process. J Environ Chem Eng 2016, 4, 2736–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Hou, P.; Petropoulos, E.; Feng, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xue, L.; Yang, L. High Efficient Visible-Light Photocatalytic Performance of Cu/ZnO/RGO Nanocomposite for Decomposing of Aqueous Ammonia and Treatment of Domestic Wastewater. Front Chem 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjith, K.S.; Manivel, P.; Rajendrakumar, R.T.; Uyar, T. Multifunctional ZnO Nanorod-Reduced Graphene Oxide Hybrids Nanocomposites for Effective Water Remediation: Effective Sunlight Driven Degradation of Organic Dyes and Rapid Heavy Metal Adsorption. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 325, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Poddar, M.; Gupta, Y.; Nigam, S.; Avasthi, D.K.; Adelung, R.; Abolhassani, R.; Fiutowski, J.; Joshi, M.; Mishra, Y.K. Solar Light Assisted Degradation of Dyes and Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions from Water by CuO–ZnO Tetrapodal Hybrid Nanocomposite. Mater Today Chem 2020, 17, 100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H.; Klausen, L.H.; Moonhee, R.; Kang, S. Emerging High-Ammonia-nitrogen Wastewater Remediation by Biological Treatment and Photocatalysis Techniques. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 875, 162603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, S.N.; Truong, T.K.; You, S.-J.; Wang, Y.-F.; Cao, T.M.; Pham, V. Van Investigation on Photocatalytic Removal of NO under Visible Light over Cr-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 12853–12859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhostin Panahi, P.; Alimohammadi, S.; Norouzi, F. Gas-Phase Photocatalytic Degradation of a Mixture of VOCs on Ag NPs Decorated ZnO. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorenza, R.; Spitaleri, L.; Perricelli, F.; Nicotra, G.; Fragalà, M.E.; Scirè, S.; Gulino, A. Efficient Photocatalytic Oxidation of VOCs Using ZnO@Au Nanoparticles. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem 2023, 434, 114232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Z.; Lian, H.; Gan, L.; Pan, M. Hierarchically Nanostructured Ag/ZnO/NBC for VOC Photocatalytic Degradation: Dynamic Adsorption and Enhanced Charge Transfer. J Environ Chem Eng 2022, 10, 108690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, P.; Puttaiah, S.H.; Wantala, K.; Shahmoradi, B. Preparation of Modified ZnO Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Chlorobenzene. Appl Water Sci 2020, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Qu, W.; Li, H.; Shi, L.; Zhang, D. Nanodiamond-Decorated ZnO Catalysts with Enhanced Photocorrosion-Resistance for Photocatalytic Degradation of Gaseous Toluene. Appl Catal B 2019, 257, 117880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Lucero, J.O.; Arriaga, S. Study of ZnO-Photocatalyst Deactivation during Continuous Degradation of n-Hexane Vapors. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem 2015, 312, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaie, S.; Vatanpour, V.; Rasoulifard, M.H.; Koyuncu, I. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) Removal by Photocatalysts: A Review. Chemosphere 2022, 306, 135655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Gao, B.; Ok, Y.S.; Dong, L. Integrated Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) Using Carbon-Based Nanocomposites: A Critical Review. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, D.; Gao, Z. Preparation of ZnO Photocatalyst for the Efficient and Rapid Photocatalytic Degradation of Azo Dyes. Nanoscale Res Lett 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.Y.; Dong, S.Y.; Sun, J.H.; Feng, J.L.; Wu, Q.H.; Sun, S.P. Microwave-Assisted Preparation, Characterization and Photocatalytic Properties of a Dumbbell-Shaped ZnO Photocatalyst. J Hazard Mater 2010, 179, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-H.; Dong, S.-Y.; Wang, Y.-K.; Sun, S.-P. Preparation and Photocatalytic Property of a Novel Dumbbell-Shaped ZnO Microcrystal Photocatalyst. J Hazard Mater 2009, 172, 1520–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaeifard, Z.; Shariatinia, Z.; Jourshabani, M.; Rezaei Darvishi, S.M. ZnO Photocatalyst Revisited: Effective Photocatalytic Degradation of Emerging Contaminants Using S-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles under Visible Light Radiation. Ind Eng Chem Res 2020, 59, 15894–15911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrà, A.; Zhang, Y.; Sepúlveda, B.; Gómez, E.; Nogués, J.; Michler, J.; Philippe, L. Highly Active ZnO-Based Biomimetic Fern-like Microleaves for Photocatalytic Water Decontamination Using Sunlight. Appl Catal B 2019, 248, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarella, M.; Di Mauro, A.; Gulino, A.; Spitaleri, L.; Nicotra, G.; Privitera, V.; Impellizzeri, G. Selective Photodegradation of Paracetamol by Molecularly Imprinted ZnO Nanonuts. Appl Catal B 2018, 238, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajala, F.; Hamrouni, A.; Houas, A.; Lachheb, H.; Megna, B.; Palmisano, L.; Parrino, F. The Influence of Al Doping on the Photocatalytic Activity of Nanostructured ZnO: The Role of Adsorbed Water. Appl Surf Sci 2018, 445, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Ahmed, E.; Zhang, Y.; Khalid, N.R.; Xu, J.; Ullah, M.; Hong, Z. Preparation of Highly Efficient Al-Doped ZnO Photocatalyst by Combustion Synthesis. Current Applied Physics 2013, 13, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wang, L.; Zong, R.; Lv, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, Y. Performance Enhancement of ZnO Photocatalyst via Synergic Effect of Surface Oxygen Defect and Graphene Hybridization. Langmuir 2013, 29, 3097–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansenya, T.; Masri, N.; Chankhanittha, T.; Senasu, T.; Piriyanon, J.; Mukdasai, S.; Nanan, S. Hydrothermal Synthesis of ZnO Photocatalyst for Detoxification of Anionic Azo Dyes and Antibiotic. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2022, 160, 110353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, Md.T.; Hoque, Md.E.; Chandra Bhoumick, M. Facile One-Pot Synthesis of Heterostructure SnO 2 /ZnO Photocatalyst for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dye. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 23554–23565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Golli, A.; Fendrich, M.; Bazzanella, N.; Dridi, C.; Miotello, A.; Orlandi, M. Wastewater Remediation with ZnO Photocatalysts: Green Synthesis and Solar Concentration as an Economically and Environmentally Viable Route to Application. J Environ Manage 2021, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Rehman, W.; Khan, M.M.; Qureshi, M.T.; Gul, A.; Haq, S.; Ullah, R.; Rab, A.; Menaa, F. Phytogenic Fabrication of ZnO and Gold Decorated ZnO Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B. J Environ Chem Eng 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Shibata, H. Preparation and Photocatalytic Activity of Hexagonal Plate-like ZnO Particles Using Anionic Surfactants. J Oleo Sci 2022, 71, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiyandari, H.; Ketut Umiati, N.A.; Dwi Herdianti, R. Synthesis and Photocatalytic Property of Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Fine Particle Using Flame Spray Pyrolysis Method. J Phys Conf Ser 2018, 1025, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vipin; Rani, M. ; Shanker, U.; Sillanpää, M. Green Synthesis of N-Doped ZnO@Zeolite Nanocomposite for the Efficient Photo-Adsorptive Removal of Toxic Heavy Metal Ions Cr6+ and Cd2+. Inorg Chem Commun 2023, 157, 111401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Furukawa, M.; Katsumata, H.; Suzuki, T.; Kaneco, S. Photocatalytic Oxidation and Simultaneous Removal of Arsenite with CuO/ZnO Photocatalyst. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem 2016, 325, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; He, Q.; Wang, S.; Han, X.; Fu, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhao, X. Recent Progress in ZnO-Based Nanostructures for Photocatalytic Antimicrobial in Water Treatment: A Review. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 7910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klienchen de Maria, V.P.; Guedes de Paiva, F.F.; Tamashiro, J.R.; Silva, L.H.P.; da Silva Pinho, G.; Rubio-Marcos, F.; Kinoshita, A. Advances in ZnO Nanoparticles in Building Material: Antimicrobial and Photocatalytic Applications – Systematic Literature Review. Constr Build Mater 2024, 417, 135337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Nancy; Bhattu, M. ; Singh, G.; Mubarak, N.M.; Singh, J. Light-Absorption-Driven Photocatalysis and Antimicrobial Potential of PVP-Capped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 13886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayevska, N.; Przysiecka, Ł.; Iatsunskyi, I.; Nowaczyk, G.; Jarek, M.; Janiszewska, E.; Jurga, S. ZnO Size and Shape Effect on Antibacterial Activity and Cytotoxicity Profile. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 8148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Li, R.; Jing, H.; Xiao, J.; Xie, H.; Hong, F.; Ta, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, C. Blocking the Reverse Reactions of Overall Water Splitting on a Rh/GaN–ZnO Photocatalyst Modified with Al2O3. Nat Catal 2023, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, S.; Hidalgo, D.; Sacco, A.; Chiodoni, A.; Lamberti, A.; Cauda, V.; Tresso, E.; Saracco, G. Comparison of Photocatalytic and Transport Properties of TiO2 and ZnO Nanostructures for Solar-Driven Water Splitting. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2015, 17, 7775–7786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhang, B.; Lin, S. P-Type ZnO for Photocatalytic Water Splitting. APL Mater 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, S.; Osterloh, F.E.; Wang, X.; Mallouk, T.E.; Maeda, K. Photocatalytic Water Splitting. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2023, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Zhu, B.; Fedin, M.V.; Cheng, B.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L. ZnO/COF S-Scheme Heterojunction for Improved Photocatalytic H2O2 Production Performance. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 444, 136584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yao, D.; Chu, C.; Mao, S. Photocatalytic H2O2 Production Systems: Design Strategies and Environmental Applications. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 451, 138489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Lu, N.; Cong, D.; Li, Z.; Han, P.; Ren, G.; Sun, L.; Liu, C.; et al. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction to Syngas Using Metallosalen Covalent Organic Frameworks. Nat Commun 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, Y.-H.; Qi, M.-Y.; Tang, Z.-R.; Xu, Y.-J. Boosting the Activity and Stability of Ag-Cu2O/ZnO Nanorods for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Appl Catal B 2020, 268, 118380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Teng, B.; Fan, M. High-Efficiency Conversion of CO2 to Fuel over ZnO/g-C3N4 Photocatalyst. Appl Catal B 2015, 168–169, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, J. Two-Dimensional ZnO for the Selective Photoreduction of CO 2. J Mater Chem A Mater 2019, 7, 16294–16303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, K.A.; Iqbal, M.; Louis, H.; Jan, S.U.; Mateen, A.; Bello, O.S. Photocatalytic Conversion of Co2 Using Zno Semiconductor by Hydrothermal Method. Pakistan Journal of Analytical and Environmental Chemistry 2018, 19, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Yadav, S.; Mittal, A.; Kumari, K. Photocatalysis by Zinc Oxide-Based Nanomaterials. In Nanostructured Zinc Oxide; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 393–457.

- Chen, D.; Wang, Z.; Ren, T.; Ding, H.; Yao, W.; Zong, R.; Zhu, Y. Influence of Defects on the Photocatalytic Activity of ZnO. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2014, 118, 15300–15307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.G.; Rao, K.S.R.K. Zinc Oxide Based Photocatalysis: Tailoring Surface-Bulk Structure and Related Interfacial Charge Carrier Dynamics for Better Environmental Applications. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 3306–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingshirn, C.F. ZnO: Material, Physics and Applications. ChemPhysChem 2007, 8, 782–803. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, M.S.; Singh, S.; Batool, M.; Fahmy, H.M.; Seku, K.; Shalan, A.E.; Lanceros-Mendez, S.; Zafar, M.N. A Review on 2D-ZnO Nanostructure Based Biosensors: From Materials to Devices. Mater Adv 2022, 4, 320–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Raub, A.A.; Bahru, R.; Mohamed, M.A.; Latif, R.; Mohammad Haniff, M.A.S.; Simarani, K.; Yunas, J. Photocatalytic Activity Enhancement of Nanostructured Metal-Oxides Photocatalyst: A Review. Nanotechnology 2024, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, T.; Liu, M.; Lin, L.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, C. A Study on Doping and Compound of Zinc Oxide Photocatalysts. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.H.; Bakar, N.H.H.A.; Bakar, M.A. Current Advancements on the Fabrication, Modification, and Industrial Application of Zinc Oxide as Photocatalyst in the Removal of Organic and Inorganic Contaminants in Aquatic Systems. J Hazard Mater 2022, 424, 127416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Bandgap | Carrier mobility | Crystalline structure | UV adsorption | Growth mode | Surface activity | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | Direct, 3.37 eV | 100-300 cm2 V−1 · s | Single crystalline | UVA absorption. Broad spectrum adsorption | Anisotropic | Mediate surface area | Easy for water corrosion |

| TiO2 | Indirect 3.2 eV for anatase 3.0 eV for rutile |

< 1 cm2 V−1 · s | Mainly in polycrystalline |

UVB absorption | Isotropic | High surface area Ultra-high for anatase phase |

Stable |

| Year | Catalyst | Application | Synthesis method | Dye | Concentration | Light Source | Conversion | Time duration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | ZnO nanoparticles | Dye degradation | sol-gel, Zinc acetate as precursor | Methyl orange | 200 mg/L | UV light | 99.70% | 30 min | [94] |

| 2010 | Dumbbell ZnO | Dye degradation | Microwave assisted hydrothermal |

Methylene Blue | 15 mg/L | 365 nm light | 99.60% | 75 min | [95] |

| 2009 | Dumbbell ZnO | Dye degradation | Hydrothermal | Crystal Violet, Methyl Violet and Methylene Blue |

15 mg/L | 365 nm light | CV: 68.0% MV: 99.0% MB: 98.5% |

75 min | [96] |

| 2020 | S-doped ZnO | Dye degradation | Hydrothermal | Rhodamine B and phenol |

5 ppm | Visible light | Rhb: 100% Phenol: 53% |

Rhb: 60 min Phenol: 180 min |

[97] |

| 2019 | Fern ZnO | Dye degradation | Electrochemical deposition | Methylene blue, nitrophenol, and Rhodamine B |

MB: 10 ppm NP:10ppm Rh-B: 5 ppm |

UV light, natural UV-filtered sunlight | MB: 99.1% NP: 98.2% Rh-B: 97.1% |

120 min | [98] |

| 2018 | ZnO nanonuts | Photodegradation of paracetamol |

Co-precipitation molecular imprinting |

Paracetamol, methyl orange dye, and phenol |

5×10-5 M | UV light | Paracetamol: 100% Phenol: 61% |

180 min | [99] |

| 2018 | Al doped ZnO | Dye degradation | Sol-gel | Indigo Carmine | Hg lamp | 97% | 180 min | [100] | |

| 2013 | Al doped ZnO-AZO |

Dye degradation | Combustion | Methyl orange | 10 mg/L | Visible light and sunlight |

99.50% | 90 min | [101] |

| 2013 | ZnO1-x/graphene hybrid | Dye degradation | ZnO reduction and GO dispersion | Methylene Blue | 1×10-5 M | UV and visible light |

97% | 300 min | [102] |

| 2022 | ZnO nanoparticles |

Dye and antibiotic degradation |

Hydrothermal | RR141, CR, and OFL | 10 mg/L | Sunlight | RR141: 100% CR: 100% OFL: 97.1% |

RR141: 20 min CR: 60 min OFL: 180 min |

[103] |

| 2020 | SnO2/ZnO | Dye degradation | One step polyol method |

Methylene Blue | na | UV | 98% | 30 min | [104] |

| 2021 | Green synthesized ZnO nanorod and nano particle | Dye degradation | Precipitation | Methylene Blue | 10 ppm | Concentrated Sunlight | 94% | 120 min | [105] |

| 2021 | Ag-ZnO | Dye degradation | Sol-gel | Methylene Blue | 10 mg/L | UV | 97.10% | 15 min | [71] |

| 2020 | Green Au/ZnO | Dye degradation | Precipitation | Rhodamine B | 10 ppm | UV | 95% | 180 min | [106] |

| 2022 | Hexagonal Plate like ZnO Particles |

Dye degradation | Hydrothermal | Methylene Blue | 1×10-5 M | UV | 100% | 60 min | [107] |

| 2018 | Plat ZnO | Dye degradation | Chemical precipitation |

Azo dye | 10 mg/L | UV and solar light | UV: 95% Solar: 88% |

UV: 240 min Solar: 80 min |

[51] |

| 2019 | ZnO nanosheet/Cellulose composite | Dye degradation | Hydrothermal | methyl orange | 20 mg/L | UV | 100% | 50 min | [38] |

| 2018 | ZnO fine particle | Dye degradation | Flame spray pyrolysis | Amaranth Dye | 10 ppm | Solar light | 95.30% | 75 min | [108] |

| 2006 | Ag-ZnO | Dye degradation | Flame spray pyrolysis | Methylene Blue | 10 ppm | 8 W UV tube | 55% | 60 min | [69] |

| 2014 | Ag-ZnO | Dye degradation | Wet chemical | Methylene Blue | 10 μM | Sun light | 94% | 20 min | [70] |

| 2021 | TiO2@ZnO heterojunction | Dye degradation | Template | Methylene Blue Methylene red |

10 ppm | Sun light | MB: 25% MR: 13% |

120 min | [72] |

| 2019 | ZnO nanoparticle | Heavy metal removal | Solid precipitation | Cu(II), Ag(I), Pb(II),Cr(VI), Mn(II), Cd(II), Ni(II) | 50 ppm | UV and visible light | Cu(II), Ag(I), Pb(II) >85% Cr(VI), Mn(II), Cd(II) and Ni(II) <15% |

60 min | [76] |

| 2020 | CuO/ZnO-T | Dye degradation Heavy metal removal |

Hydrothermal | BV-3, RY-145 Cr (VI) and Pb(II) |

40 ppm- dye 10-60 mg/L- heavy metal ion |

Sun light | 80% RY-145 86% BV-3 99% Cr (VI) 97% Pb(II) |

30 min | [83] |

| 2023 | N-doped ZnO@Zeolite |

Heavy metal removal | Dip-coating | Cr (VI), Cd(II) | 10-100 mg/L | Sun light | 93% Cr (VI) 89% Cd(II) |

60 min | [109] |

| 2016 | CuO/ZnO | Photocatalytic oxidation | Mechnical mixing | As(III) solution | 30 mg/L | UV light | 94% | 240 min | [110] |

| 2018 | Ternary ZnO-Ag-Au nanorod array | Reduction of aqueous heavy metal ions |

Photodeposition method and electrostatic self-assembly |

Cr solution | 5 mg L–1 | 300 W Xe arc lamp | 60% | 120 min | [77] |

| 2016 | CuO/ZnO-Pottery plate | Ammonia degradation | Dip-coating | Ammonia | 85-510 mg/L | Visible/UV (280–390 nm) | 77.20% | 30 min | [80] |

| 2018 | Cu/ZnO/rGO | Ammonia degradation | Dip-coating | Ammonia | 50 mg/L | Visible light | 83.10% | 120 min | [81] |

| 2024 | Ag/ZnO | VOC abatement | Photoreduction method |

ethanol, ethyl acetate, and toluene | -- | Visible light | ethanol: 82% ethyl acetate: 78% toluene: 73% |

-- | [86] |

| 2023 | ZnO@Au core-shell | VOC abatement | -- | toluene, formaldehyde, ethanol | -- | Visible light | formaldehyde: 85% toluene: 95% |

-- | [87] |

| 2020 | Ag/ZnO, Cd/ZnO and Pb/ZnO |

VOC abatement | Solgel | Colorobenzene | 20 µg/L | Fluorescent light, UV light, tungsten light and LED light |

100% under visible light | 120 min | [89] |

| 2019 | Nanodiamand-ZnO | VOC abatement | Dehydration condensation | toluene | 50 ppm in air | xenon lamp | 100.00% | 120 min | [90] |

| Year | Title | Content | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 92 years of zinc oxide: has been studied by the scientific community since the 1930s- An overview | Brief introduction of ZnO history, properties, and benefits, fabrication methods of ZnO, and prospective implementations of ZnO in many fields of industry. | [14] |

| 2007 | ZnO: Material, Physics and Applications | Summary of material growth, fundamental properties of ZnO and ZnO-based nanostructures and doping as well as present and future applications with emphasis on the electronic and optical properties including stimulated emission. | [129] |

| 2022 | ZnO nanostructured materials and their potential applications: progress, challenges and perspectives | Chemical methods of preparation of ZnO NPs. Green method for the synthesis of ZnO NPs. Modifications of ZnO with organic and inorganic compounds and multitudinous applications of ZnO NPs. | [13] |

| 2019 | ZnO as a Functional Material, a Review | Review of current state of ZnO structures and synthesis technologies, with the main development directions underlined as epitaxial, thin film, thick film or nanostructure. | [21] |

| 2022 | Recent Advances in ZnO-Based Nanostructures for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Hazardous, Non-Biodegradable Medicines | Review of comprehensive understanding of the degradation of antibiotics using ZnO-based nanomaterials (bare, doped, and composites) for effective treatment of wastewater containing antibiotics. | [65] |

| 2023 | A review on 2D-ZnO nanostructure based biosensors: from materials to devices | The review reports on the main advances in2D-ZnO nanostructure-based biosensors, including syntheis method, biomolecule immobilization on ZnO nanostructure, and classification of ZnO biosensors. | [130] |

| 2024 | Photocatalytic activity enhancement of nanostructured metal-oxides photocatalyst: a review | The paper provides an in-depth analysis of the photocatalytic activity of nanostructured metal oxides, including the photocatalytic mechanism, factors affecting the photocatalytic efficiency, and approaches taken to boost the photocatalytic performance throughstructure or material modifications. THE paper also highlights an overview of the recent applications and discusses the recent advancement of ZnO-based nanocomposite as a promising photocatalytic material for environmental remediation, energy conversion, and biomedical applications. | [131] |

| 2023 | Recent Advances in ZnO-Based Nanostructures for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Hazardous, Non-Biodegradable Medicines | The paper presents and discusses recent advances in the photocatalytic degradation of widely used drugs by ZnO-based nanostructures, namely (i) antibiotics; (ii) antidepressants; (iii) contraceptives; and (iv) anti-inflammatories. The work endows a comprehensive understanding of the degradation of antibiotics using ZnO-based nanomaterials (bare, doped, and composites) for effective treatment of wastewater containing antibiotics. | [65] |

| 2022 | A Study on Doping and Compound of Zinc Oxide Photocatalysts | The paper summarizes the research on this aspect at home and abroad in recent years, introduces the doping of transition metal ions by zinc oxide, the compounding of zinc oxide with precious metals or other semiconductors | [132] |

| 2024 | Current trends and future perspectives on ZnO-based materials for robust and stable solar fuel (H2) generation | The review examines ZnO-based photocatalytic H2 generation via water splitting with different modification strategies and explores future outlooks for improving performance of ZnO. | |

| 2023 | Preparations and applications of zinc oxide based photocatalytic materials | The review summarizes the preparation and application of ZnO-based composites with high catalytic performance, including modification strateties, applications, and future challenges. | [68] |

| 2021 | Photocatalysis by zinc oxide-based nanomaterials | In the book chapter, the authors have focused on the various techniques to modify the characteristics of ZnO and recent advancements in the synthetic strategy to develop highly efficient materials. The alteration in the properties of ZnO can be done by the introduction of foreign elements in three ways, that is, metal doping, nonmetal doping, and formation of coupled materials with other semiconductor materials. | [126] |

| 2021 | ZnO Nanoadsorbents: A potent material for removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater | The authors systematically review the use of ZnO nanostructures for removing poisonous heavy metal ions from water. Various ZnO-based nanostorbents such as pristine ZnO NPs, doped ZnO nanostrutes, ZnO nanocomposites, and surface-modified ZnO NPs are reviewed thoroughly along with the comparisons of their maximum adsorption capacity for different heavy metal ions (Cd2+, Hg2+, As3+, Pb2+, Cr6+, Ni2+, Co2+, and Cu2+) in a tabular form. | [78] |

| 2025 | A review on modified ZnO to address environmental challenges through photocatalysis: Photodegradation of organic pollutants | This review aims to examine the current research progress on ZnO-based nanomaterials developed for the photocatalytic organic contaminant degradation. | [73] |

| 2022 | Photocatalytic activity of zinc oxide for dye and drug degradation: A review | In this review paper photocatalytic degradation of zinc oxide has been highlighted. Nanoparticles of ZnO have been investigated as photocatalysts that can be applied for degradation of dyes, drugs and other pollutants. | [75] |

| 2020 | ZnO based nanomaterials for photocatalytic degradation of aqueous pharmaceutical waste solutions – A contemporary review | The current review highlights the ongoing advancements being catered to modify conventional ZnO into its advanced NCs counterpart as photocatalyst for degradation of PDs. Further, based on Literature, the detailed mechanisms of common PDs degradation by ZnO based NCs have also been reviewed. | [74] |

| 2022 | Current advancements on the fabrication, modification, and industrial application of zinc oxide as photocatalyst in the removal of organic and inorganic contaminants in aquatic systems | The current review summarizes the recent advances in the fabrication, modification, and industrial application of ZnO photocatalyst based on the analysis of the latest studies from different aspects including ZnO overview, modifications, applicability, industries use, and bio-inspired ZnO. | [133] |

| 2022 | Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) removal by photocatalysts: A review | This review tries to investigate the state-of-art of recently published papers on this subject with a focus on the high-efficiency photocatalyst. | [92] |

| 2019 | Integrated adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using carbon-based nanocomposites: A critical review | This review provides a critical review of the related literature with focuses on: (1) the advantages and disadvantages of various carbon-based nanocomposites for the applications of VOC adsorption and photocatalytic degradation; (2) models and mechanisms of adsorptive-photocatalytic removal of VOCs according to the material properties; and (3) major factors controlling adsorption-photocatalysis processes of VOCs. | [93] |

| 2022 | Recent Progress in ZnO-Based Nanostructures for Photocatalytic Antimicrobial in Water Treatment: A Review | This review is a comprehensive overview of recent progress in the following: (i) preparation methods of ZnO-based nanomaterials and comparison between methods; (ii) types of nanomaterials for photocatalytic antibacterials in water treatment; (iii) methods for studying the antimicrobial activities and (iv) mechanisms of ZnO-based antibacterials. Subsequently, the use of different doping strategies to enhance the photocatalytic antibacterial properties of ZnO-based nanomaterials is also emphatically discussed. Finally, future research and practical applications of ZnO-based nanomaterials for antibacterial activity are proposed. | [111] |

| 2022 | p-type ZnO for photocatalytic water splitting | In the Perspective, the authos discuss recent advances in the fabrication of p-type ZnO by different dopants and describe the benefits of p-type ZnO compared to n-type ZnO for photocatalytic applications. Finally, we analyze the difficulties and challenges of p-type ZnO employed in photocatalytic water splitting and consider the future advancement of p-type ZnO in an emerging area. | [117] |

| 2023 | Photocatalytic H2O2 production Systems: Design strategies and environmental applications | This review article introduces the strategies for improving the H2O2 production efficiency based on the recombination of electron-hole pairs, low visible light utilization, and poor product selectivity. | [120] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).