1. Introduction

The high morbidity and increasing frequency of degenerative diseases in humans and animals force the development of advanced and functional prostheses, dressings, or active intrabody structures [

1,

2]. On-going research aiming to develop novel biomaterials for tissue engineering includes synthetic and bio-inspired polymers, despite the various limitations of each. In the first case, an easy production process and its modifications are advantageous, while in the second one, it has higher cyto- and biocompatibility [

3,

4]. All mentioned features are combined in hybrid materials, simultaneously creating new properties for the resulting biomaterials [

5], supporting their directional action in saturation with various natural compounds [

6,

7,

8] or metal oxides [

9,

10,

11]. Nowadays, when creating new materials, attention is paid to not only that they should be indifferent to the recipient’s organism but also active and biodegradable during the treatment process [

12]. In recent years, the natural polymer silk fibroin (SF) has become a subject of interest in tissue engineering due to its good biocompatibility and relatively high bioactivity. Therefore, this material has been broadly used in musculoskeletal engineering for tissue regeneration [

13,

14,

15]. The first patent for a silk-based porous scaffold produced from a freeze-dried native silk solution (i.e., silk extracted directly from the silk gland of mulberry silkworm) was issued in 1987 [

16]. Biomaterials that are hybrids of silkworm fibroin with calcium phosphate, graphene oxide, titanium dioxide, silica, bioactive glass, silver, polycaprolactone, collagen and gelatin, chitosan, extracellular matrix, cellulose, or alginate have already been developed for sports medicine [

17]. Multicomponent hybrids are also possible, especially that biphasic and multiphase scaffolds can be more effective in repairing interface tissue in comparison with single-phase scaffolds [

18,

19,

20,

21]. The major disadvantages of SF scaffolds include the low cell-adhesive activity and difficulty in the independent tuning of mechanical and biodegradation properties [

22,

23]. Silk derived from the mulberry silkworm must also be modified for medical use, which may result in detrimental changes in the mechanical properties [

24]. In addition, moisture inside the human body constitutes a potential challenge since it softens and weakens silk produced by terrestrial arthropods.

Thousands of invertebrate species spin silk, and the amino acid composition and properties of silk fibroin from various taxa can differ from widely used silk produced by

Bombyx mori [

25,

26,

27]. Silk produced by caddisfly larvae seems to be an interesting and innovative modifier of biomaterials that can be used for medical purposes. As in closely related butterflies, silk is spun by spinnerets located near the mouth part [

28]. Silk secretion is the final product of paired silk glands, which are modified salivary glands. The proteins biosynthesized in the trichopteran silk glands are the silk thread's precursors as well as the underwater cement (depending on the taxonomic group of caddisflies). The formation of silk threads or filling mass is regulated in the silk glands by the presence of phosphate residues binding cations of divalent elements. Multivalent metal cations (mainly Ca

2+ and Mg

2+) are integrated into the silk fibres from the environment during the spinning process rather than being incorporated into the silk precursors in the silk gland. The silk fibroin produced by the Trichoptera is similar to Lepidoptera and consists of homologues of both H-fibroin and L-fibroin, however, but without glycoprotein P25, as well as without sericin encasement bonding the double strand [

29,

30]. From a commercial point of view, the use of trichopteran silk is advantageous due to its high charge density, which is acquired through the phosphorylation of serines and the accumulation of basic residues [

31]. Post-translational phosphorylation of serine provides a multitude of potential interfacial adhesion mechanisms [

30,

32]. Firm adhesion is likely due to covalent-cross linking and electrostatic interactions [

33,

34]. Phosphorylation of serines that are also found in their terrestrial cousins - butterflies and moths, may be primarily responsible for the adaptation of the ancestral dry silk to the underwater environment of caddisfly larvae [

31]. In trichopteran silk, phosphate groups are accompanied by a high proportion of basic residues, which are nearly absent in terrestrial silks [

35]. As a result, caddisfly H-fibroins are polyampholytic [

31]. Phosphates can form several types of water-resistant bonds, which makes them highly effective and versatile adhesion promoters in wet conditions [

30,

32].

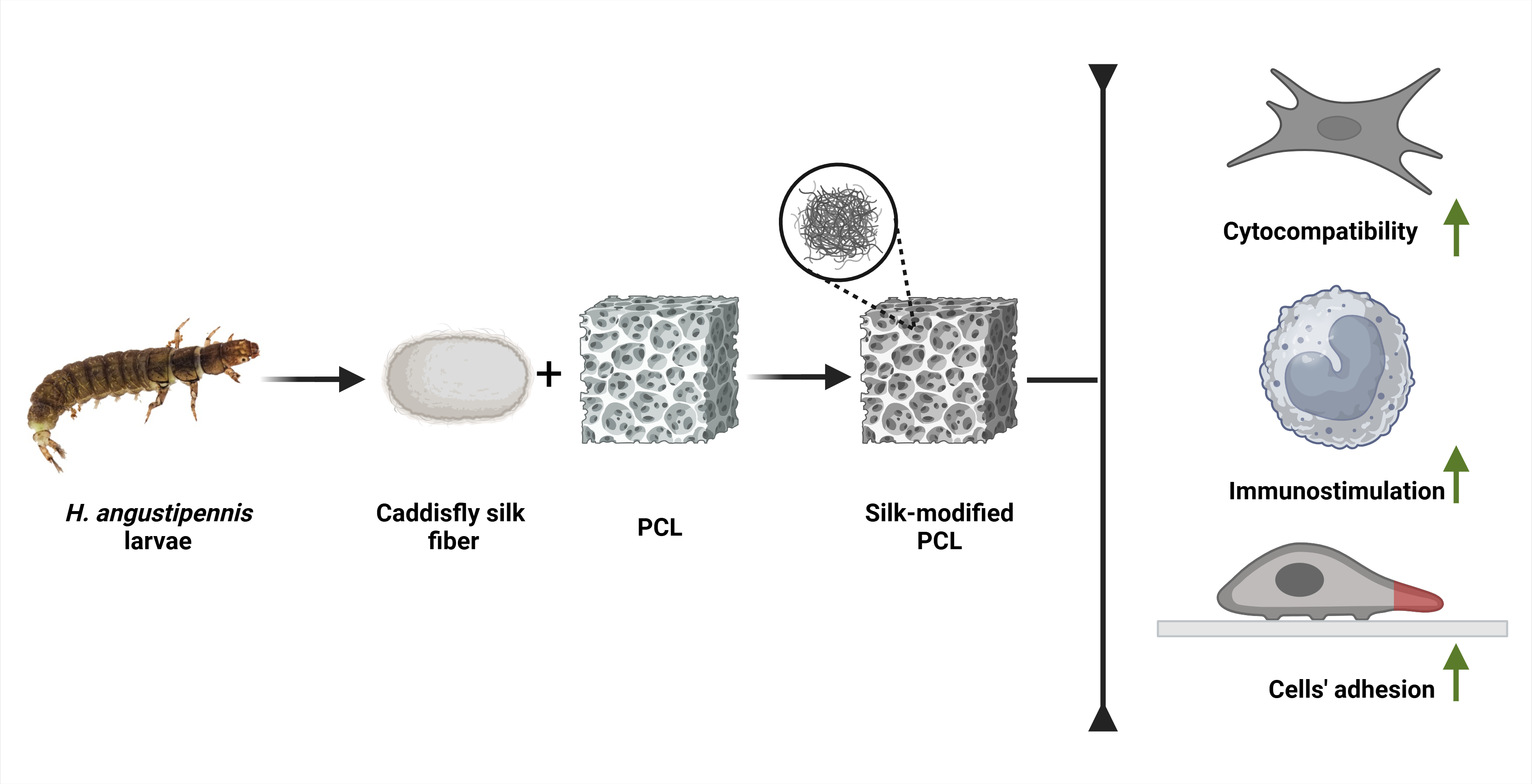

Currently, receiving silk from caddisfly larvae in industrial quantities is possible as receiving silk from spiders [

36]. Therefore, we tested the unique properties of the silk secretion from the

Hydropsyche angustipennis species as an extender for a synergistic combination with an artificial polymer. Following the suggestions of Cai et al. [

37], He et al. [

38], and Wang et al. [

39] a biocomposites were created as a scaffold for the following examinations. These studies aimed to determine the physicochemical and biological properties with an indication of a potential medical or dental application..

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Preparation of Trichopteran Silk

Caddisfly silk fiber produced by

H. angustipennis larvae was obtained from pupal cocoons and used as a short threads. Individuals collected from the natural environment were bred for 2 weeks under laboratory conditions (water temperature maintained at 14°C, oxygen saturation at 4.5 mg/dm

3) until they produced cocoons. Before they were placed in the laboratory setup, each larva was repeatedly rinsed with deionized water and deprived of food to empty their alimentary tracts. During the breeding process, water was exchanged every second day [

28]. The cocoons obtained were mechanically rinsed in deionized water and then homogenized in a water solution using an X-120 knife homogenizer (CAT Ingenieurbüro GmbH, Germany). Homogenization was performed at 3500 rpm for 4 min. Homogenates were steam sterilized by autoclaving at 121°C and pressure 115 kPa for 20 min [

28]. The silk prepared using this protocol was then freeze-dried.

2.2. Polycaprolactone (PCL) Foam Scaffolds Preparation

In the study, we used polycaprolactone (PCL) Capa 6800® (Perstorp, Sweden) and 1,4-dioxane (Chempur, Poland). PCL and PCL with 30 wt.% silk (PCL with caddisfly silk) were prepared using the Thermally Induced Phase Separation Technique (TIPS) according to the procedure described in our previous study [

40]. Briefly, 5 wt.% solution in 1,4-dioxane was prepared using magnetic stirrer (40°C, 24 h). Next, silk was added to the PCL solution and mixed overnight (hybridization). Then, the mixture was frozen (-40°C, 24 h) and freeze-dried (20 Pa, 24 h). More details on obtaining this biomaterial are included in Polish Patent No. PL.244676/2024.

2.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The DSC measurements were performed using a DSC1 Mettler Toledo (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) differential scanning calorimeter equipped with a Huber TC 100 intracooler as a cooling system. Measurements were recorded within the temperature range of -70–100°C with heating/cooling rates of 10°C/min, under a nitrogen flow of 60 mL/min. The weight of the measured samples was about 3 mg. The recorded DSC curves were normalized to the sample mass and evaluated using the generic STARe ver.16.2 software (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland).

The materials' initial degree of crystallinity Xc was determined using equation X based on the first DSC heating scan.

where:

ΔHm – melting enthalpy of PCL [J/g],

ΔHm100% - melting enthalpy of 100% crystalline PCL – 135 J/g [

41],

w - PCL weight fraction in composite.

2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric analysis was carried out using a TGA/DSC1 Mettler Toledo (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) thermobalance. The samples were measured with a heating rate of 10°C/min in the temperature range of 25-900°C under a constant nitrogen purge of 60 mL/min. The initial mass of the tested samples was about 3 mg.

2.5. Attenuated Total Reflectance - Fourier Transform Infrared Reflectance (ATR-FTIR)

The ATR-FTIR spectra were recorded in ATR mode using Nicolet iZ10 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) within 600-4000 cm-1. The spectra were recorded in 32 scans with a resolution of 4 cm-1.

2.6. Attenuated Total Reflectance - Fourier Transform Infrared Reflectance (ATR-FTIR)

The ATR-FTIR spectra were recorded in ATR mode using Nicolet iZ10 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) within 600-4000 cm-1. The spectra were recorded in 32 scans with a resolution of 4 cm-1.

2.7. Water Contact Angle Measurement

The water surface angle measurements were conducted with a PG-X contact angle goniometer (Testing Machines, New Castle, DE, USA). At least 5 measurements were made for each sample. The mean value and the standard deviation were calculated.

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

The morphology of the PCL foams and the PCL foams modified/hybridized with caddisfly silk was examined with an electron scanning microscope (Phenom ProX, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The samples were not coated with carbon and gold for microscope examination. Observations were carried out with an accelerating voltage of 10 kV at magnifications between 275× and 910×.

2.9. Sterilization and Sample Preparation

Prior to the biological evaluation, all composites were sterilized by gamma-irradiation (35 kGy gamma rays;

60Co source) at the Institute of Applied Radiation Chemistry, Technical University in Lodz (Lodz, Poland), as previously described [

42]. For cytotoxicity assay, composites were cut into pieces corresponding to one-tenth of the well surface area, as recommended by ISO 10993-5:2009 (Biological evaluation of medical devices-Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity). To evaluate the composites in regard cell expansion and adhesion by confocal microscopy imaging samples were cut into 7 mm diameter discs.

2.10. Cell Culture and Propagation

The L929 (CCL-1) mouse skin fibroblasts were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Prior to experiments, fibroblasts were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA), penicillin (100U/mL), and streptomycin (100 µg/mL) (Sigma Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) at a temperature of 37°C, in a humidified air atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The confluent cell monolayers were detached from the culture vessel with 0.5% trypsin-EDTA solution (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) and suspended in a culture medium. Cell viability and density were established using a Bruker chamber (Blaubrand, Wertheim, Germany) and trypan blue exclusion assay, respectively. Cell suspensions with viability exceeding 95% were used in cytocompatibility experiments. Cell culture morphology was monitored using an inverted microscope (Motic AE2000, Xiamen, China).

The THP1-Blue NF-κB human monocytes (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, and selective agents (100 μg/mL normocin and 10 μg /mL blasticidin) in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C.

2.11. Direct Contact Cytotoxicity Assay

The metabolic activity of cells exposed to tested biomaterials was evaluated by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction assay as described previously [

43]. 2×10

5 L929 cells/mL were transferred (100 µL/well) into 96-well culture plates (Nunclon Delta Surface, Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) and incubated overnight (37°C, 5% CO

2) to recreate cell monolayers. Next, composites were cut into pieces corresponding to one-tenth of the well surface area and were added to the cell monolayer in six replicates. After overnight incubation, 20 µL of MTT (Sigma Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to each well, and incubation was continued for the next 4 hrs. Next, the supernatants were removed and replaced with 200 µL of DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide). The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using the Multiskan EX reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cell cultures in a medium without the tested materials were used as a non-treated (NTC) control of viability, and cell cultures treated with 2% hydrogen peroxide served as a treated control (TC) of viability. The commercially available biomaterial—tubing samples from the Blood Collection Set (Vacutainer, BD Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used as a reference.

2.12. Cell Proliferation Assay

The proliferation of L929 fibroblasts was evaluated after 24, 48, 72 and 96 h of incubation with PCL foam scaffolds using CyQUANT Cell Proliferation Assay (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as described previously [

44]. At the selected time points, cells within the foam composites were washed with PBS and frozen at -80°C. Before DNA quantification, samples were thawed at room temperature, and the cells were lysed for 5 min in a buffer containing the CyQuant-GR dye, which stains cellular DNA. Fluorescence was measured at an emission wavelength of 520 nm and excitation wavelength of 480 nm using a SpectraMax® i3x Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Standard curves were also established using serial dilutions of known cell suspensions.

2.13. Visualisation of Cell Adhesion and Penetration

After 96 h of incubation with L929 fibroblasts, the caddisflies silk, PCL foams, and the PCL foams modified with caddisflies silk were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Control samples were cells cultured directly on microscope slides, which allowed for consistent imaging conditions and served as a reference for experimental groups. The cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, DNA was stained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 5 min (0.5 mg/mL) and Texas Red™ Phalloidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for F-actin staining (0.1 μg/mL). Then, images were taken with confocal laser scanning microscopy platform TCS SP8 (Leica Microsystems, Frankfurt, Germany) with the objective 63×/1.40 (HC PL APO CS2, Leica Microsystems, Frankfurt, Germany). For nuclei stained with DAPI, excitation and emission parameters were 405 nm and 460–480 nm, respectively. For visualization of F-actin stained with Texas Red™ Phalloidin supercontinuum laser with 595 nm excitation and emission wavelengths at 610–630 nm was applied. The Leica Application Suite X software (LAS X, Leica Microsystems, Frankfurt, Germany) was used for analyses and performing 3D images. The average sizes of cells were presented as an average SD from no less than ten cells from three independent fields of view.

2.14. Immunomodulatory Properties

The THP1-Blue™ NF-κB cells were used to determine the activation of NF-κB signal transduction pathway as described previously [

45]. Briefly, THP-1 Blue™ NF-κB Cells were plated at 1×10

5 cells/well. Then, composites cut into pieces corresponding to one-tenth of the well surface area, were added to selected wells (in six replicates) and stimulated overnight at 37°C in a humified 5% CO

2 atmosphere. The monocytes incubated in the medium served as the non-treated (NTC) control, whereas monocytes stimulated with LPS

Escherichia coli (100 ng/mL) were used as a treated (TC) control for NF-κB activation. Additionally, preincubation of composites with polymyxine B (PMB; 1 µg/mL; 30 min, 37°C) give additional information on the endotoxin/non-endotoxin related cell activation. The secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) was quantified by combining 20 μL of cell-free supernatant with 180 μL QUANTI-Blue™ buffer (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO

2 for 4 h. Optical density was measured at 650 nm on Multiskan EX reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.15. Resazurin Assay for Assessment of Antimicrobial Properties

The metabolic activity of bacterial cells exposed to tested biomaterials was evaluated by resazurin reduction, as described previously [

46]. A 100 µL of bacterial suspensions of

Escherichia coli ATTC 12287 (3.6×10

5 CFU/mL) or

Staphylococcus aureus (5.6×10

5 CFU/mL) were transferred into 96-well black culture plates (Nunclon Delta Surface Black, Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) and incubated for 30 min (37°C). Next, the composites were cut into pieces corresponding to one-tenth of the well surface area and added to the respective wells. (in six replicates). After overnight incubation, to quantify cell viability, 20 µL of 0,02% resazurin solution (sterilized through 0.22 nm filters) was added to each well, and incubation was continued for the next 4 h. Within this time, the non-fluorescent blue dye resazurin is able to penetrate the cell, where it is transformed into a pink fluorescent dye resorufin in response to the activity of reductases present in the cell. Therefore, such a process can only take place in living cells. After 4 h of incubation at 37°C, the level of fluorescence was measured using a SpectraMax® i3x Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) at wavelengths: λex= 530 nm, λem= 590 nm. Cell viability was calculated relative to an non-treated control with tested biomaterials, which was set to 100% viability.

2.16. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the data. Intra-group differences were assessed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. Some data were compared using a regular one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons. The differences were considered significant when a p-value < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biomaterials Properties

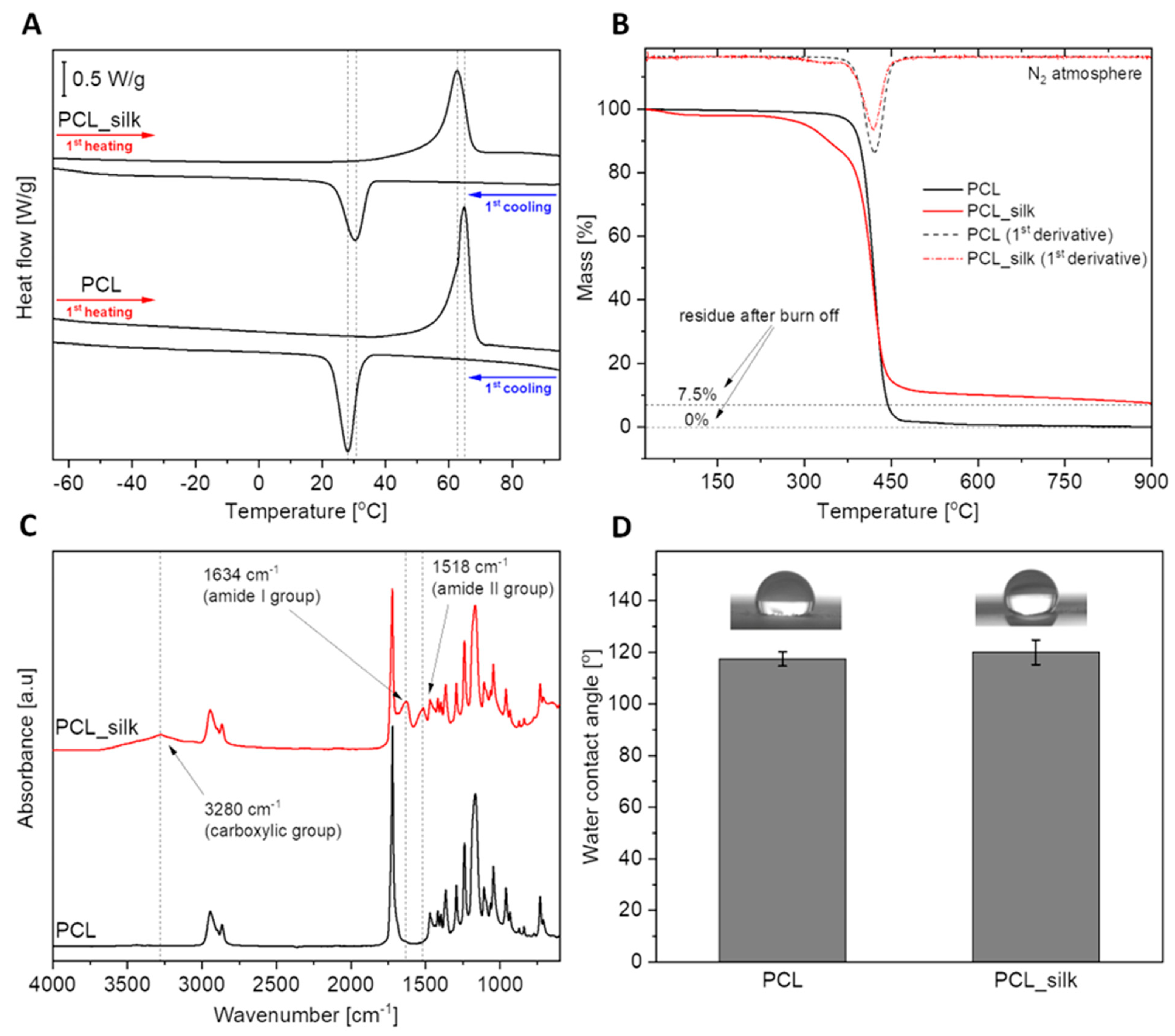

Figure 1A shows the curves from the first heating and first cooling scans for both pure polycaprolactone and composite material. The courses of the corresponding curves are very similar for each sample. A clear endothermic effect related to the polymer melting process can be observed during the heating of materials. The observed effect was characterized by two parameters: T

m – melting point and ΔH

m – melting enthalpy, the values of which are listed in

Table 1. Despite the significant addition of silk fibers (30% by weight), the melting point changed slightly from 64.9°C to 63.0°C. Based on the enthalpy of melting, the degree of crystallinity of the polymer was calculated for both materials. It turns out that the PCL foams with caddisfly silk material have a higher degree of crystallinity by about 9%. This proves the nucleating properties of silk fibers. The second effect, exothermic, visible on the cooling scans, proves the crystallization of the polymer from the melt during its cooling process. This effect was also characterized by two parameters: T

c – temperature of crystallization and ΔH

c – enthalpy of crystallization. The enthalpy values given in the table have been normalized to the weight of the sample. However, by normalizing to the weight of the polymer, a value of 57.2 J/g is obtained for the composite foam, which is higher than that of neat PCL (54.8 J/g). The increased value of ΔH

c, together with the increased crystallization temperature, again confirms the nucleation effect after introducing the filler into the system [

40].

Figure 1B presents the thermogravimetric curves of the materials, showing their thermal stability. To quantify them, three parameters were determined for both curves: T

(-5%), the temperature at a loss of 5% of the sample weight; T

(DTG), the temperature corresponding to the peak maximum of the first derivative of the TGA curve, indicating the most rapid loss of sample weight; and Residue, the amount of material remaining at 900°C. These parameters are listed in

Table 1. First, the material based on neat PCL is characterized by high thermal stability, showing rapid weight loss above 350°C. Only at over 370°C is a loss of 5% of the sample weight. The situation is different in the case of PCL foams with caddisfly silk material.

The composite is less stable, and mass loss occurs in several stages, which is also clearly visible during the first derivative curve. The first weight loss occurs already in the temperature range of 25°C-100°C. Silk fibers have a strong ability to absorb water or other polar solvents, and this weight loss is related to the evaporation of this fraction [

28]. Then, just above 300°C, the second stage of weight loss occurs, directly related to the degradation of caddisfly fibres. The highest rate of mass loss at this stage takes place at a temperature of approximately 325°C. The last, largest mass loss reaches its maximum rate at about 410°C and is directly related to the degradation of the PCL. After all, although PCL foam degrades completely at 900°C, approximately 7.5% residue is observable with composite foam. The recorded residue comes from the inorganic impurities present in caddisfly fibers, which would need much higher temperatures to evaporate [

28,

47].

It is worth emphasizing the low melting point of the developed composite materials (Tm=63°C), which results in attractive processing properties combined with high thermal stability. This creates the potential to process/manufacture such materials by thermal methods, free from organic solvents, such as extrusion, injection molding or various 3D printing techniques.

The FTIR analysis allowed for qualitative confirmation of the chemical composition of PCL and PCL-silk foams. The course of the black curve visible in

Figure 1C corresponds to the course for pure PCL described in the literature [

48]. On the other hand, in the spectrum recorded for the PCL foams with the caddisfly silk sample, additional distinct bands were observed, indicating the presence of caddisfly fibers in the system. These bands show the presence of carboxyl, amide I, and amide II groups in the fiber structure, confirming the protein-based structure of silk fibers [

49]. The presence of a significant number of polar groups and the ability to absorb water resulting from the TGA tests would indicate an improvement in the wettability of the composite material compared to the neat polymer. However, as can be seen in

Figure 1D, the wettability of the surface with water practically did not change. This is most likely not so much related to the surface's chemical composition as to its morphology itself [

50].

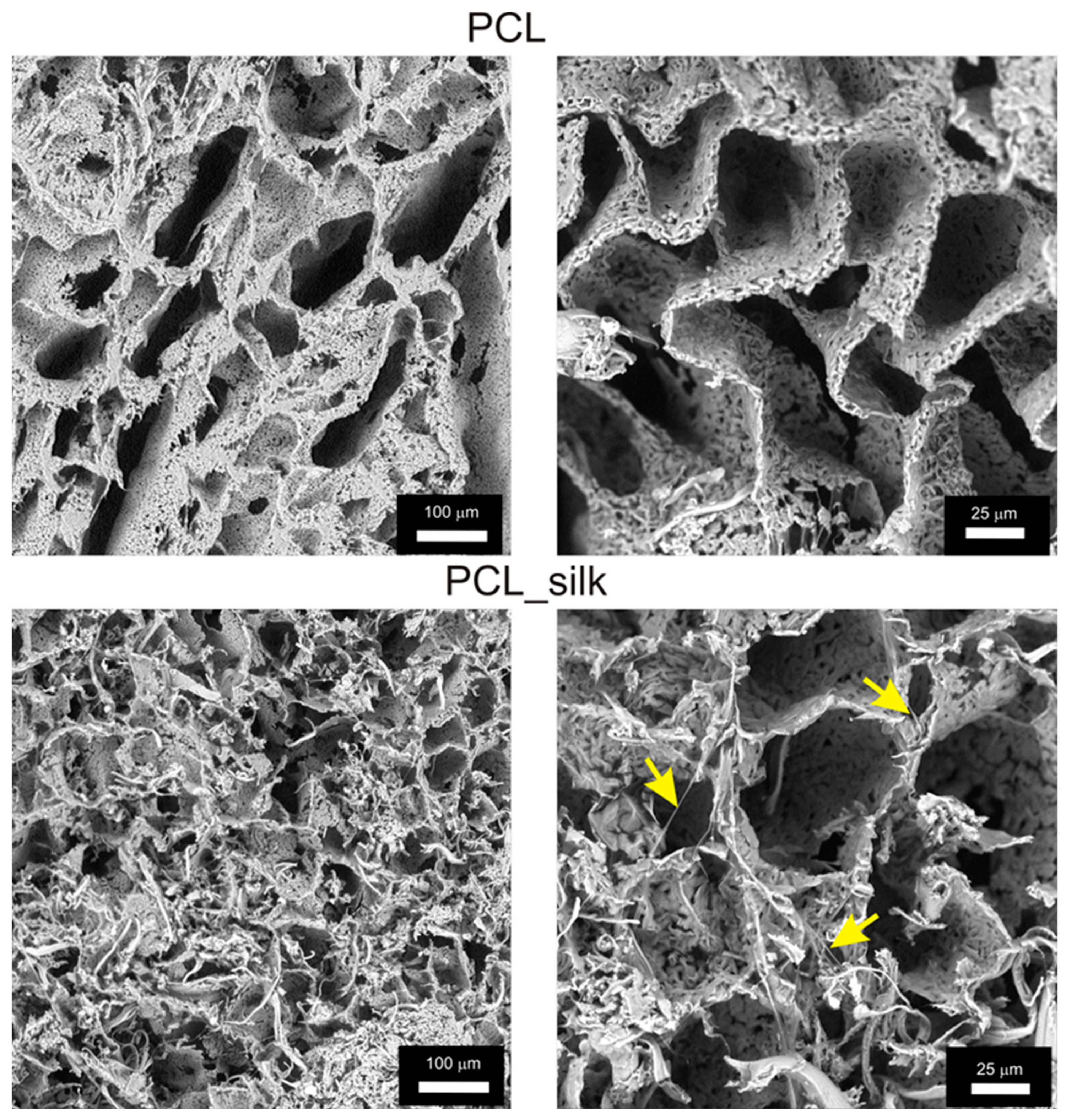

3.2. Microstructure of PCL Foams Modified with Silk

The PCL foams characterized a porous structure, while the introduction of caddisfly silk into the structure of the biomaterial resulted in the deposition of silk in the free spaces, where fragments of fibers were visible inside the pores (

Figure 2).

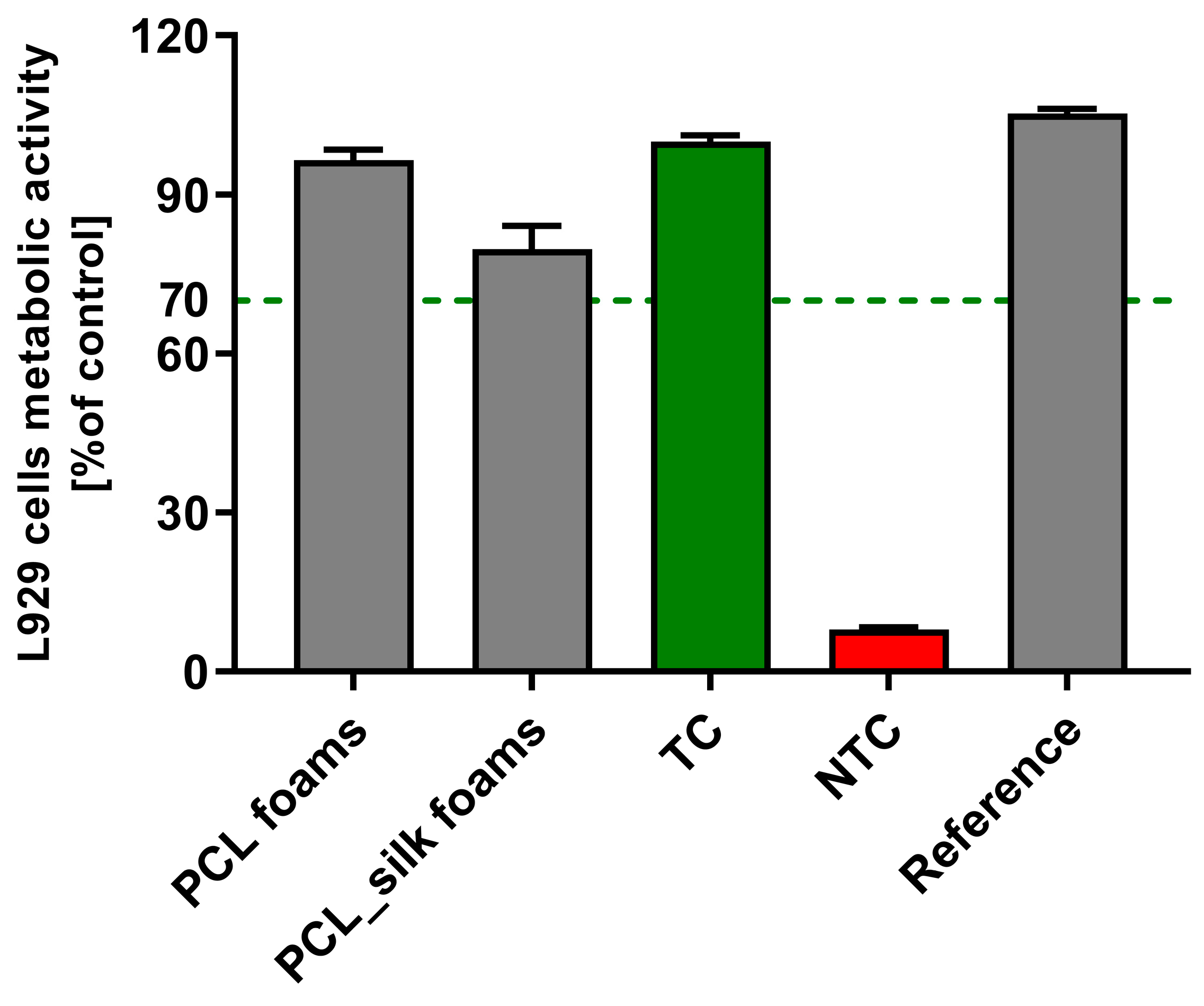

3.3. Cell Viability

Cytocompatibility is considered to be one of the most important requirements of materials used for biomedical applications. Thus, the viability of L929 fibroblasts incubated for 24 h with biocomposites was evaluated using MTT reduction assay according to ISO-10993-5:2009 recommendations. As shown in

Figure 3, the viability of murine fibroblasts exposed to PCL foams and PCL foams with caddisfly silk reached 96.6% ± 1.9% and 79.8% ± 4.3%, respectively. In this way, all the tested materials met the ISO criterion of maintaining the viability of at least 70% of cells after incubation in the biomaterial's milieu. Our results are in concordance with those of Farokhi et al. [

51]. They revealed the lack of cytotoxic properties of silk fibroin scaffold on rabbit osteoblasts up to 20 days of incubation of cells in the milieu of biomaterial. Moreover, they also observed the increase in ATP production by cells treated with SF throughout the experiment, which is particularly important in bone tissue regeneration. SF biosafety has also been demonstrated against breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-23 [

52]. The viability of these cells exposed to silk fibroin nanoparticles at various concentrations (25-400 µg/mL) for 72 h remained above 80%. Furthermore, these studies showed that SF nanoparticles may represent an attractive, non-toxic nanocarrier for the delivery of anti-cancer drugs.

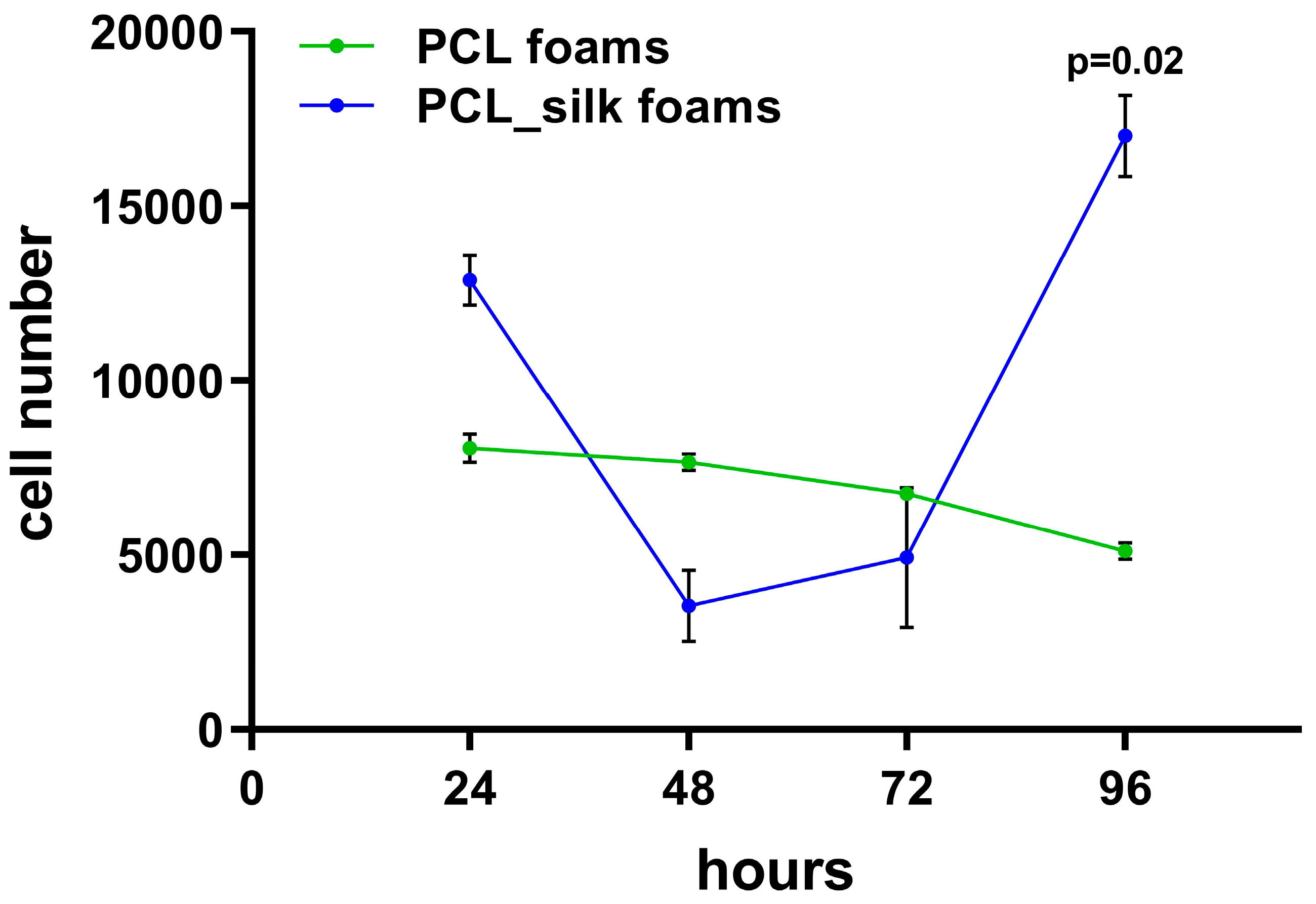

3.4. Cell Proliferation

Proliferation assay used in this study measure the relative DNA content, to evaluate the number of L929 cells within PCL and PCL foams with caddisfly silk followed for up to 96 h of culture (

Figure 4). The number of L929 fibroblasts colonizing the PCL foams decreased slowly with the duration of the experiment from 7.7×10

3 ± 0.1×10

3 cells in 48 h to 5.1×10

4 ± 0.1×10

4 cells in 96 h. Interestingly, the number of cells detected on the PCL foams with caddisfly silk decreased in the first stages of colonization (up to 48 h: 3.5×10

4 ± 1.0×10

4) and then increased rapidly reaching at 96 h 17.0×10

4 ± 1.2×10

4, which was statistically significant (p=0.02) as compared to the number of cells colonizing the PCL foams. Thus, we have shown that the PCL foams modified with caddisfly silk stimulated L929 fibroblast proliferation.

Silk proteins are known to support the growth and proliferation of fibroblasts and keratinocytes [

53]. Silk sericin has been reported to enhance the proliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes responsible for wound re-epithelialization, fibroblasts necessary to close the wound, and endothelial cells responsible for the formation of new blood vessels within the regenerated tissue [

54].

Our results are corroborated by the findings reported by Moisenovich et al. [

55]. They observed that silk fibroin scaffolds and composite scaffolds with gelatin and HA additives enhance mouse embryonic fibroblast adhesion and proliferation, which leads to wound healing and tissue regeneration. This makes them promising materials for regenerative medicine. On the contrary, silk fibroin peptide (SFP) inhibited the proliferation of lung cancer cells (A549 and H460) in a dose-dependent manner and suppressed the clonogenic activity [

56].

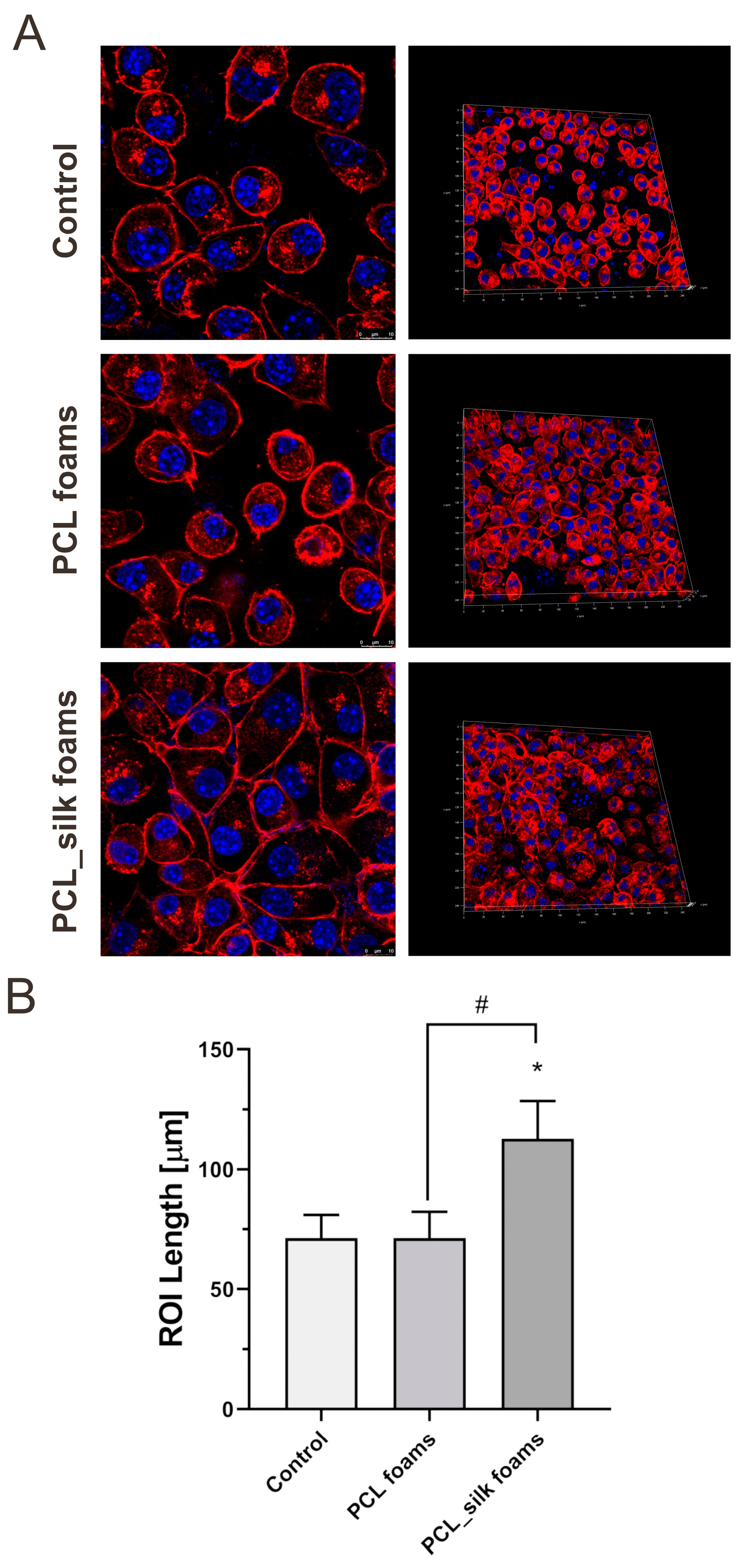

3.5. Cell Attachment and Penetration

To investigate the impact of PCL foams and PCL foams modified with caddisflies silk after 96 h of incubation on cell morphology confocal microscopy was applied. As shown on

Figure 5 the PCL_silk foams supported the adhesion of murine fibroblasts that formed compact monolayer compared to the control cells. While the cells seeded on PCL foams exhibit proper morphology with the regular shape of cell and physiological nucleus similar to control cells, modification with caddisflies silk influenced cell morphology by increasing the length of cells and their circumference. Previously, it was reported that silk optimization might increase adhesion properties to various surfaces in a water environment [

31,

32,

57]. The fibroblasts' attachment to silk is comparably high compared to their adhesion to collagen films [

3]. Additionally, our preliminary examination indicated increased growth of mouse fibroblasts (NIH/3T3) and human dermal fibroblasts (BJ) cells, enhanced attachment, and proliferation on the caddisfly silk surface [

28]. Zakeri Siavashani et al. reported that silk-based scaffolds supported fibroblasts (MG-63) attachment on the biomaterial surface, provided physiological morphology of the cells, and enabled well spread of fibroblasts with visible cell-to-cell contact [

58]. The authors suggested that this feature allows using caddisfly silk in medical applications [

28,

47].

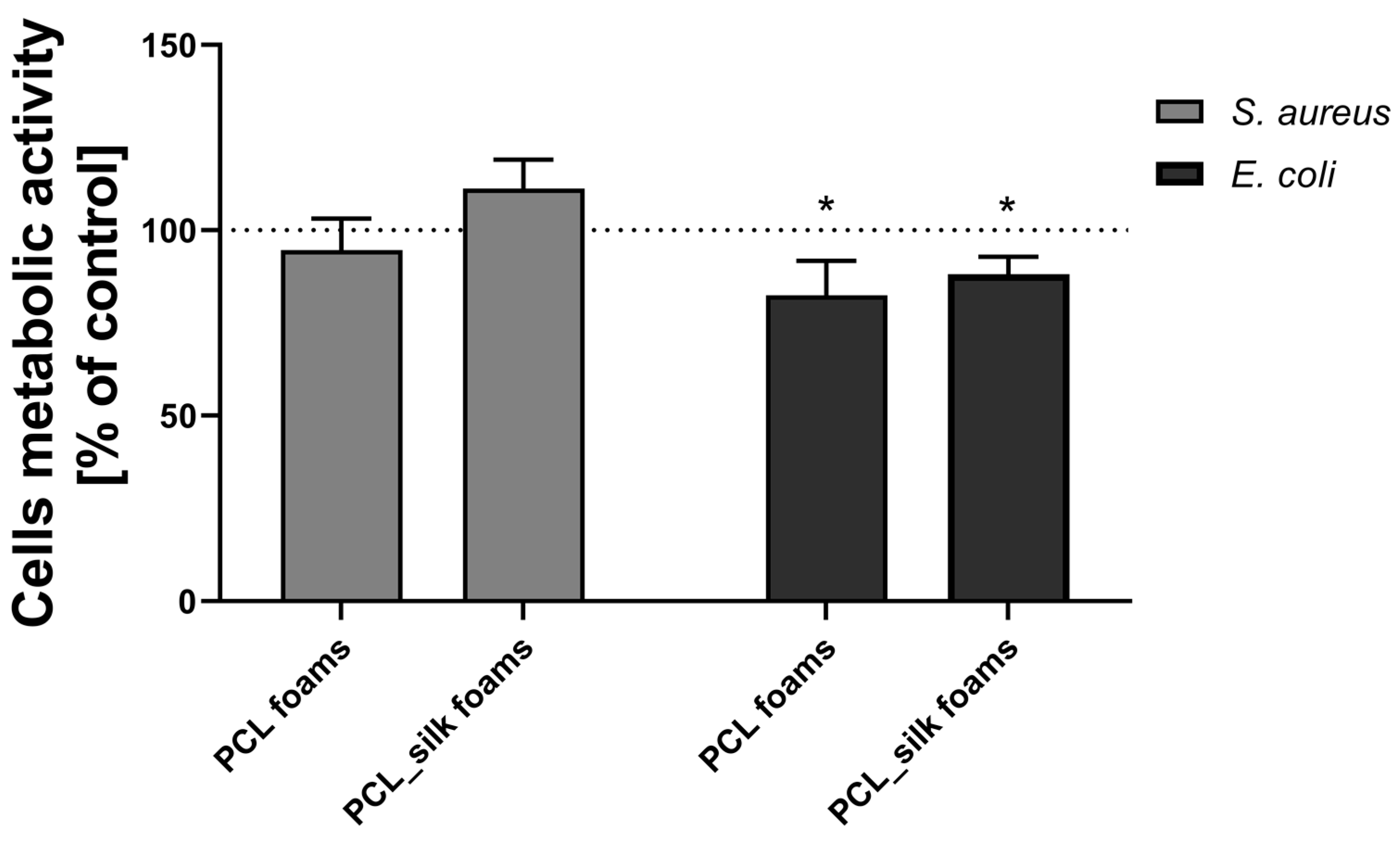

3.6. Antimicrobial Properties

The antimicrobial activity of PCL foams and PCL foams modified with caddisflies silk after 24 h of incubation with

S. aureus or

E. coli was determined by the resazurin reduction tests. The incubation of

S. aureus with PCL foams (94.7% ± 8.5%) and PCL foams (111.2% ± 7.8%) did not cause the statistically significant decrease in the number of bacteria compared to the bacteria incubated without foams (

Figure 6). Test samples incubated in the presence of

E. coli caused a statistically significant decrease in the metabolic activity of the cells after 24 h of incubation. Accordingly, PCL foams up to 82.5% ± 9.3%, p < 0.05 and PCL foams with caddisflies silk up to 88.1 % ± 4.7%, p < 0,05. Our results correspond with previously described data [

59,

60]. As we have demonstrated, the addition of caddisfly silk does not alter the antimicrobial activity of PCL.

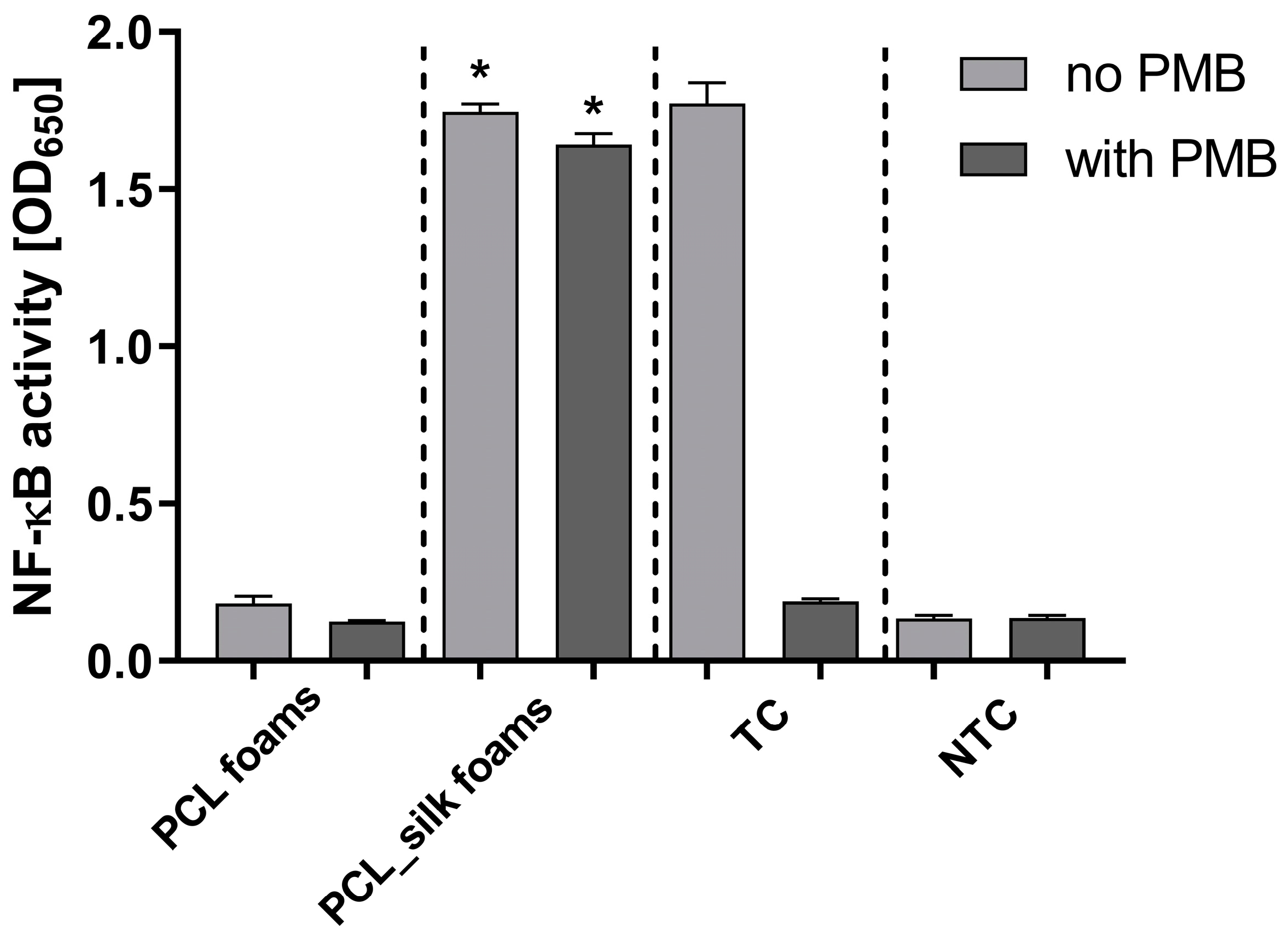

3.7. Immunostimulatory Activity

We used THP1-Blue NF-κB human monocytes, carrying NF-κB-inducible SEAP reporter construct, to determine the activation of the NF-κB signal transduction pathway via tested PCL materials. The PCL modification with caddisflies silk induced NF-κB activation up to the level induced with LPS

E. coli (treated control), and it was significantly higher (p<0.05) as compared to PCL foams (

Figure 7). However, the addition of polymyxin B (PMB), an inhibitor of LPS, had no effect on PCL-modified scaffolds-induced changes in the secretion of embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) but completely inhibited the LPS-induced increases in SEAP production.

Activation of the NF-κB is crucial to stimulate the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) that promote proliferation and migration of fibroblast and keratinocyte [

61,

62]. NF-κB activating biomaterials can enhance cell growth and migration to the lesion site and positively affect the remodelling of damaged tissue [

63,

64]. Hence, further studies on PCL foams with caddisfly silk regarding their pro-inflammatory properties for targeted tissue regeneration are required.

4. Conclusions

In this study, comparison between scaffolds based on pure PCL and PCL with the addition of 30% by weight of caddisfly silk fibers were examined. The materials are characterized by distinct macroporosity, which is disrupted by the presence of the fibrous filler. Composite foams exhibit greater water absorption and lower thermal stability compared to the pure polymeric ones. Nevertheless, in both cases, the thermal stability of the materials exceeds 290°C. This, combined with the low melting temperature (ranging from 63°C to 65°C), enables the potentially effective processing of materials using thermal methods, such as material extrusion 3D printing or injection molding. Moreover, the addition of fibers did not significantly affect the surface wettability, which remains around 120 degrees in both cases. The investigated PCL foams modified with caddisfly silk were found to be fully cytocompatible. Moreover, the caddisfly silk surface of foams promoted a more effective adhesion and proliferation of fibroblasts L929 compared to the PCL matrix. It is worth noting that the tested PCL foams with caddisfly silk demonstrated the induction of NF-κB while excluding bacterial LPS-mediated stimulation measured in monocyte/macrophage inflammation sensing system using human THP1-Blue NF-κB cells. Furthermore, foams modified with caddisfly silk, as well as PCL, showed antimicrobial activity only against E. coli. Overall, the biological assessment of the PCL foams modified with caddisfly silk makes them a promising candidate suitable for medical or dental applications.

5. Patents

The results of the work described in this article resulted in the receipt of a Polish Patent No. PL.244676/2024.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.T., A.S.-G., K.R. and M.M.U.; Data curation: A.S.-G. and M.W.; Formal analysis: K.S., A.S.-G., M.W., K.R., and M.M.U.; Funding acquisition: K.R., Investigation: B.K., M.W., A.S.-G., S.M., M.C., and M.M.U.; Methodology: B.K., M.W., and A.S.-G.; Project administration: K.R.; Resources: S.M., K.S., K.R., M.T., and M.M.U.; Supervision: K.R., M.T., K.S., and M.M.U.; Validation: M.W. and A.S.-G.; Visualization: B.K., M.W., A.S.-G., and S.M.; Writing – original draft: M.T., K.S., B.K., M.W., A.S.-G., T.I., and M.M.U.; Writing – review and editing: K.S., T.I, M.C, A.S.-G., K.R., and M.M.U.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during this study are available at the University of Lodz, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, Department of Immunology and Infectious Biology, Lodz, 90-237, Poland, and they are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

Bartłomiej Kryszak was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Szwed-Georgiou, A.; Płociński P.; Kupikowska-Stobba B.; Urbaniak; M.M., Rusek-Wala, P.; Szustakiewicz, K.; Piszko, P.; Krupa, A.; Biernat, M.; Gazińska, M.; Kasprzak, M.; Nawrotek, K.; Mira, N.P.; Rudnicka, K. Bioactive Materials for Bone Regeneration: Biomolecules and Delivery Systems. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2023, 9, 5222–5254.

- Langer, R.; Vacanti, J. Tissue engineering. Science 1993, 260, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vepari, C.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk as a Biomaterial. Progress in Polymer Science 2007, 32, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Cheng, R.; Neves, J.D.; Tang, J.; Xiao, J.; Ni, O.; Liu, X.; Pan, G.; Li, D.; Cui, W.; Sarmento, B. Advances in Biomaterials for Preventing Tissue Adhesion. Journal of Controlled Release 2017, 261, 318–336. [Google Scholar]

- Murugan, R.; Ziyad, H.; Seeram, R.; Hisatoshi, H.; Youssef, H. Ceramic scaffolds, current issues and future trends, Integrated biomaterials in tissue engineering, Scrivener Publishing, Beverly, 2012.

- Yang, G.; Lin, H.; Rothrauff, B.B.; Yu, S.; Tuan, R.S. Multilayered Polycaprolactone/Gelatin Fiber-Hydrogel Composite for Tendon Tissue Engineering. Acta Biomaterialia 2016, 35, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Miwa, E.; Asai, F.; Seki, T.; Urayama, K.; Nakatani, T.; Fujinami, S.; Hoshino, T.; Takata, M.; Liu, C.; Mayumi, K.; Ito, K.; Takeoka, Y. Highly Transparent and Tough Filler Composite Elastomer Inspired by the Cornea. ACS Materials Letters 2020, 2, 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, L.; Liao, Y.; Xu, B.; Bao, R.; Wang, R.; Liu, W. Nano-Silver in Situ Hybridized Collagen Scaffolds for Regeneration of Infected Full-Thickness Burn Skin. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2015, 20, 4231–4241. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Jung, R.; Kim, H.S.; Youk, J.H.; Jin, H.J. Silver Nanoparticles Incorporated Electrospun Silk Fibers. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2007, 7, 3888–3891. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.Y.; Lu, Y. Fabrication and Properties of Conductive Conjugated Polymers/Silk Fibroin Composite Fibers. Composites Science and Technology 2008, 68, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.R.; Chen, Y.Y.; Xu, G.H.; Ye, X.J.; He, D.N.; Zhong, J. Micropattern of Nanohydroxyapatite/ Silk Fibroin Composite onto Ti Alloy Surface via Template-Assisted Electrostatic Spray Deposition. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2012, 32, 390–394. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, S.; Gangwar, S. An Overview on Recent Progresses and Future Perspective of Biomaterials. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2018, 404, 012013. [Google Scholar]

- Manchineella, S.; Thrivikraman, G.; Khanum, K.; Ramamurthy, P.; Basu, B.; Govindaraju, T. Pigmented Silk Nanofibrous Composite for Skeletal Muscle Tissue Engineering. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2016, 5, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Luo, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W. Knitted Silk Mesh-Like Scaffold Incorporated with Sponge-Like Regenerated Silk Fibroin/Collagen I and Seeded with Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Repairing Achilles Tendon in Rabbits. Acta of Bioengineering and Biomechanics 2018, 20, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Cao, L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, A.; Jiao, D.; Zeng, D.; Wang, X.; Kaplan, D.L.; Jiang, X. Functionalization of Silk Fibroin Electrospun Scaffolds via BMSC Affinity Peptide Grafting through Oxidative Self-Polymerization of Dopamine for Bone Regeneration. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2019, 11, 8878–8895. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada, Y.; Minoura, N. National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology. Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Patent No. JPH01118544A, 1987.

- Wu, R.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Li, S.; Chen, Y. Bioactive Silk Fibroin-Based Hybrid Biomaterials for Musculoskeletal Engineering: Recent Progress and Perspectives. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2021, 4, 6630–6646. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, G.; He, J.; Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk-Based Biomaterials in Biomedical Textiles and Fiber-Based Implants. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2015, 4, 1134–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Luo, Y.; Wan, Y. Fabrication and Characterization of Layered Chitosan/Silk Fibroin/Nano-Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds with Designed Composition and Mechanical Properties. Biomedical Materials 2015, 10, 045013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Chu, Y.; He, J.; Shao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Qi, K.; Wang, L.; Cui, S. A Graded Graphene Oxide-Hydroxyapatite/Silk Fibroin Biomimetic Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017, 80, 232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, P.; Pramanik, K.; Biswas, A. Chondrogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Silk Fibroin:Chitosanglucosamine Scaffold in Dynamic Culture. Regenerative Medicine 2018, 13, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Egaña, A.; Scheibel, T. Interactions of Cells with Silk Surfaces. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2012, 22, 14330–14336. [Google Scholar]

- Kambe, Y. Functionalization of Silk Fibroin-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering. Polymer Journal 2021, 53, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rigueiro, J.; Elices, M.; Llorca, L.; Viney, C. Effect of Degumming on the Tensile Properties of Silkworm (Bombyx Mori) Silk Fiber. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2002, 84, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Li, C.; Mu, X.; Kaplan, D.L. Engineering Silk Materials: From Natural Spinning to Artificial Processing. Applied Physics Reviews 2020, 7, 011313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reddy, N.; Yang, Y. Structure and Properties of Cocoons and Silk Fibers Produced by Hyalophora Cecropia. Journal of Materials Science 2010, 45, 4414–4421. [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa, K.; Nomura, T.; Arai, R.; Abe, K.; Tsukada, M.; Hirabayashi, K. Characterization of Underwater Silk Proteins from Caddisfly Larva, Stenopsyche Marmorata, Biotechnology of silk, biologically inspired systems, Springer, Dordrecht, 2014.

- Tszydel, M.; Zabłotni, A.; Wojciechowska, D.; Michalak, M.; Krucińska, I.; Szustakiewicz, K.; Maj, M.; Jaruszewska, A.; Strzelecki, J. Research on Possible Medical Use of Silk Produced by Caddisfly Larvae of Hydropsyche angustipennis (Trichoptera. Insecta), Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2015, 45, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Yonemura, N.; Mita, K.; Tamura, T.; . Sehnal, F. Conservation of Silk Genes in Trichoptera and Lepidoptera. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2009, 68, 641–653. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, N.N.; Taggart, D.S.; Stewart, R.J. Silk Tape Nanostructure and Silk Gland Anatomy of Trichoptera. Biopolymers 2012, 97, 432–445. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.J.; Wang, C.D. Adaptation of Caddisfly Larval Silks to Aquatic Habitats by Phosphorylation of H-Fibroin Serines. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N.; Roe, D.; Weiss, R.; Cheatham, T.; Stewart, R. Self-Tensioning Aquatic Caddisfly Silk: Ca2+-Dependent Structure. Strength, and Load Cycle Hysteresis, Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 3668–3681. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.J.; Ransom, T.C.; Hlady, V. Natural Underwater Adhesives. Journal of Polymer Science, Part B: Polymer Physics 2011, 49, 757–771. [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa, K.; Miura, Y.; Nomura, T.; Arai, R.; Abe, K.; Tsukada, Hirabayashi, J. Long-Range Periodic Sequence of The Cement/Silk Protein of Stenopsyche marmorata: Purification and Biochemical Characterization. The Journal of Bioadhesion and Biofilm Research 2013, 29, 357–367. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engster, M.S. Studies on Silk Secretion in the Trichoptera (Family: Limnephilidae). Cell and Tissue Research 1976, 169, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, L.C. Spiderwebs and silk. Tracing evolution from molecules to genes to phenotypes, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003.

- Cai, Z.; Mo, X.; Zhang, K.; Fan, L.; Yin, A.; He, C.; Wang, H. Fabrication of Chitosan/Silk Fibroin Composite Nanofibers for Wound-dressing Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2010, 11, 3529–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, P.; Ng, K.; Chen, K.; Toh, S.; Goh, J. Enhanced Osteoinductivity and Osteoconductivity through Hydroxyapatite Coating of Silk-Based Tissue-Engineered Ligament Scaffold. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2013, 101, 555–566. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; Cheng, N.; Tao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Q. Collagen/Silk Fibroin Composite Scaffold Incorporated with PLGA Microsphere for Cartilage Repair. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2016, 61, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szustakiewicz, K.; Gazińska, M.; Kryszak, B.; Grzymajło, M.; Pigłowski, J.; Wiglusz, R.J.; Okamoto, M. The Influence of Hydroxyapatite Content on Properties of Poly(L-Lactide)/Hydroxyapatite Porous Scaffolds Obtained Using Thermal Induced Phase Separation Technique. European Polymer Journal 2019, 113, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Kadena, K.; Ishizone, K.; Nojima, S.; Shimizu, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Nakahama, S. Crystallization Behavior and Crystal Orientation of Poly(Ε-Caprolactone) Homopolymers Confined in Nanocylinders: Effects of Nanocylinder Dimension. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 1892–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słota, D.; Piętak, K.; Florkiewicz, W.; Jampílek, J.; Tomala, A.; Urbaniak, M.M.; Tomaszewska, A.; Rudnicka, K.; Sobczak-Kupiec, A. Clindamycin-Loaded Nanosized Calcium Phosphates Powders as a Carrier of Active Substances. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, M.M.; Gazińska, M.; Rudnicka, K.; Płociński, P.; Nowak, M.; Chmiela, M. In Vitro and In Vivo Biocompatibility of Natural and Synthetic Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pyomelanin for Potential Biomedical Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, M.; Szwed-Georgiou, A.; Rudnicka, K.; Płociński, P.; Pagacz, J.; Tymowicz-Grzyb, P.; Woźniak, A.; Włodarczyk, M.; Urbaniak, M.M.; Krupa, A.; Rusek-Wala, P.; Karska, N.; Rodziewicz-Motowidło, S. Dual Modification of Porous Ca-P/PLA Composites with APTES and Alendronate Improves Their Mechanical Strength and Cytobiocompatibility towards Human Osteoblasts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 14315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazińska, M.; Krokos, A.; Kobielarz, M.; Włodarczyk, M.; Skibińska, P.; Stępak, P.; Antończak, A.; Morawiak, M.; Płociński, P.; Rudnicka, K. Influence of Hydroxyapatite Surface Functionalization on Thermal and Biological Properties of Poly(L-Lactide) and Poly(L-Lactide-Co-Glycolide)-Based Composites. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 6711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Słota, D.; Urbaniak, M.M.; Tomaszewska, A.; Niziołek, K.; Włodarczyk, M.; Florkiewicz, W.; Szwed-Georgiou, A.; Krupa, A.; Sobczak-Kupiec, A. Crosslinked Hybrid Polymer/Ceramic Composite Coatings for the Controlled Release of Clindamycin. Biomaterials Science 2024, 12, 5253–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, N.; Pan, H.; Stewart, R.J. Connecting Caddisworm Silk Structure and Mechanical Properties: Combined Infrared Spectroscopy and Mechanical Analysis. Open Biology 2016, 6, 160067. [Google Scholar]

- Elzein, T.; Nasser-Eddine, M.; Delaite, C.; Bistac, S.; Dumas, P. FTIR Study of Polycaprolactone Chain Organization at Interfaces. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2004, 273, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tszydel, M.; Sztajnowski, S.; Michalak, M.; Wrzosek, H.; Krucińska, I. Structure and Physical and Chemical Properties of Fibres from the Fifth Larval Instar of Caddis-Flies of the Species Hydropsyche angustipennis. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe 2009, 17, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Udayakumar, K.; Gore, P.; Kandasubramanian, B. Foamed Materials For Oil-Water Separation. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2021, 5, 00076. [Google Scholar]

- Farokhi, M.; Mottaghitalab, F.; Hadjati, J.; Omidvar, R.; Majidi, M.; Amanzadeh, A.; Azami, M.; Tavangar, S.; Shokrgozar, M.; Ai, J. Structural and Functional Changes of Silk Fibroin Scaffold due to Hydrolytic Degradation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2014, 131, 39980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, A.; Wani, S.; Osmani, R.; Abu Lila, A.; Khafagy, E.; Arab, H.; Gangadharappa, H.; Allam, A. Formulation, Characterization, and Cellular Toxicity Assessment of Tamoxifen-Loaded Silk Fibroin Nanoparticles in Breast Cancer. Drug Delivery 2021, 28, 1626–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, B.; Kurland, N.; Bano, S.; Patra, C.; Engel, F.; Yadavalli, V.; Kundu, S. Silk Proteins for Biomedical Applications: Bioengineering Perspectives. Progress in Polymer Science 2014, 39, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode Boni, B.; Bakadia, B.; Osi, A.; Shi, Z.; Chen, H.; Gauthier, M.; Yang, Y. Immune Response to Silk Sericin-Fibroin Composites: Potential Immunogenic Elements and Alternatives for Immunomodulation. Macromolecular Bioscience 2022, 1, 2100292. [Google Scholar]

- Moisenovich, M.; Arkhipova, A.; Orlova, A.; Volkova, S.; Zacharov, S.; Agapov, I.; Kirpichnikov, A. Composite Scaffolds Containing Silk Fibroin, Gelatin, and Hydroxyapatite for Bone Tissue Regeneration and 3D Cell Culturing. Acta Naturae 2014, 6, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Du, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Du, S.; Chen, S.; Zhao, H.; Yan, Z. Silk Fibroin Peptide Suppresses Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest in Human Lung Cancer Cells. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2019, 40, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strzelecki, J.W.; Strzelecka, J.; Mikulska, K.; Tszydel, M.; Balter, A.; Nowak, W. Nanomechanics of New Materials – AFM and Computer Modeling Studies of Trichoptera Silk. Central European Journal of Physics 2011, 9, 482–491. [Google Scholar]

- Zakeri Siavashani, A.; Mohammadi, J.; Maniura-Weber, K. , Senturk, M.; Nourmohammadi, J.; Sadeghi, B.; Huber, L.; Rottmar, M. Silk Based Scaffolds with Immunomodulatory Capacity: Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Nicotinic Acid. Biomaterials Science 2020, 8, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, G.; Ko, S.; Je, J.; Kim, Y.; Oh, J.; Jung, W. Fabrication. Characterization and Determination of Biological Activities of Poly(Ε-Caprolactone)/Chitosan-Caffeic Acid Composite Fibrous Mat for Wound Dressing Application. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2016, 93, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar]

- Yahiaoui, F.; Benhacine, F.; Ferfera-Harrar, H.; Habi, A.; Hadj-Hamou, A.; Grohens, Y. Development of Antimicrobial PCL/Nanoclay Nanocomposite Films with Enhanced Mechanical and Water Vapor Barrier Properties for Packaging Applications. Polymer Bulletin 2015, 72, 235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Ghosh, S.; De, S.; Basak, P.; Maurye, P.; Jana, N.K.; Mandal, T.K. Immunomodulatory and Antimicrobial Non-Mulberry Antheraea Mylittasilk Fibroin Acceleratesin Vitrofibroblast Repair and Regeneration by Protecting Oxidative Stress. RSC Advances 2021, 11, 19265–19282. [Google Scholar]

- Best, K.; Nichols, A.; Knapp, E.; Hammert, W.; Ketonis, C.; Jonason, J.; Awad, H.; Loiselle, A. NF-kB Activation Persists into the Remodeling Phase of Tendon Healing and Promotes Myofibroblast Survival. Science Signaling 2020, 13, abb7209. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Kundu, S. Isolation. Purification and Characterization of Silk Protein Sericin from Cocoon Peduncles of Tropical Tasar Silkworm, Antheraea Mylitta. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2006, 38, 255–258. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).