Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

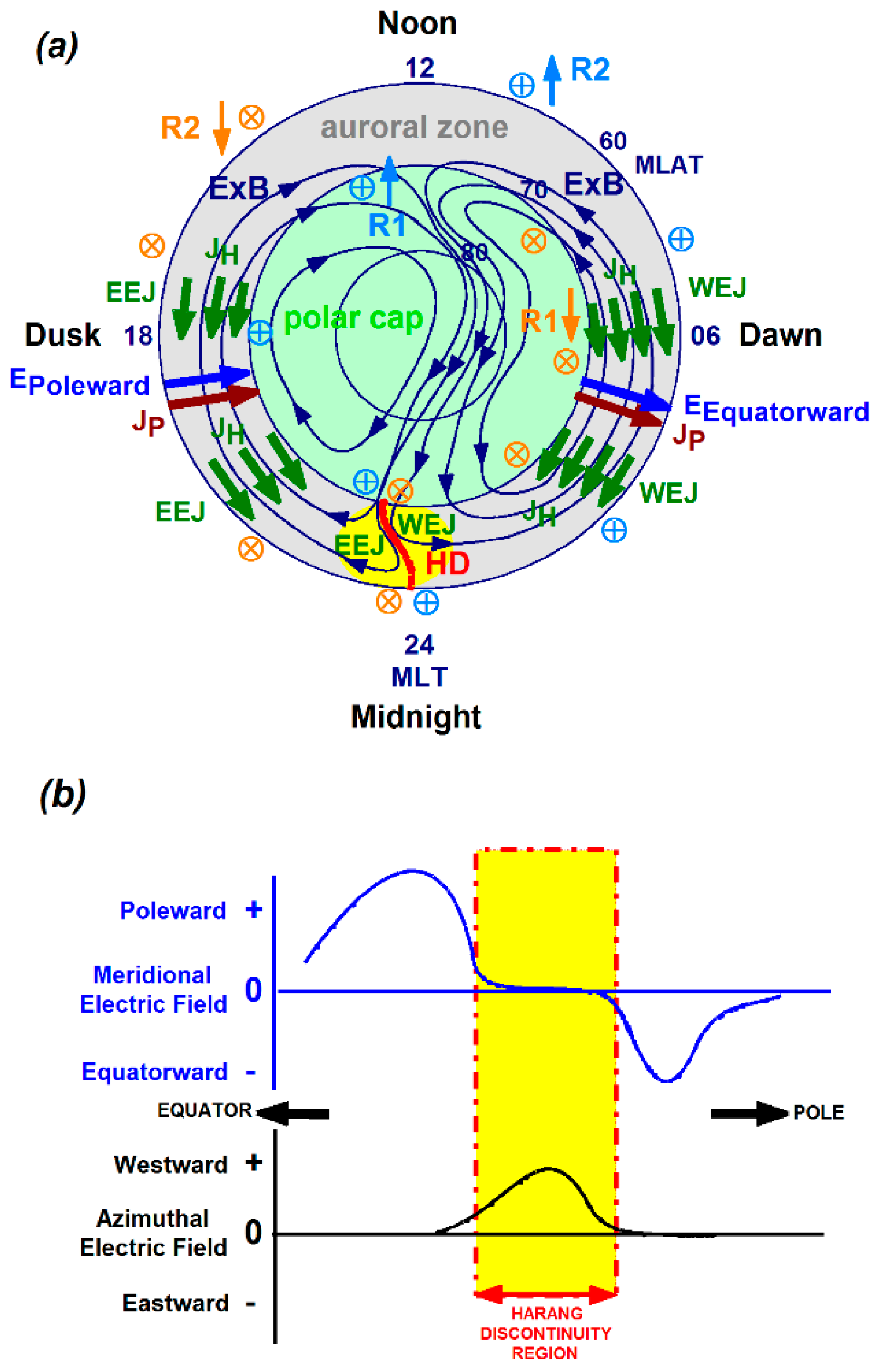

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

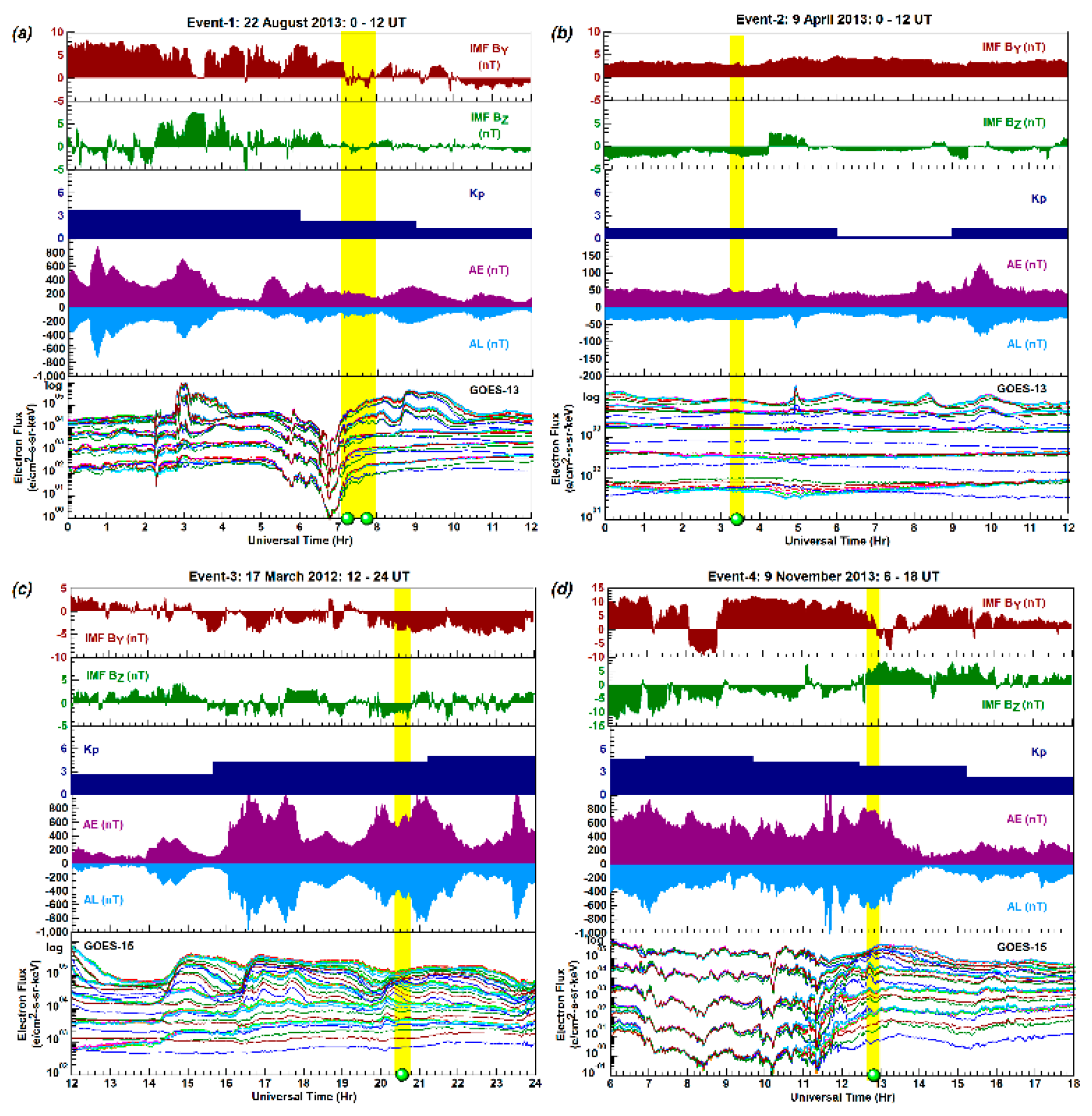

3. Results

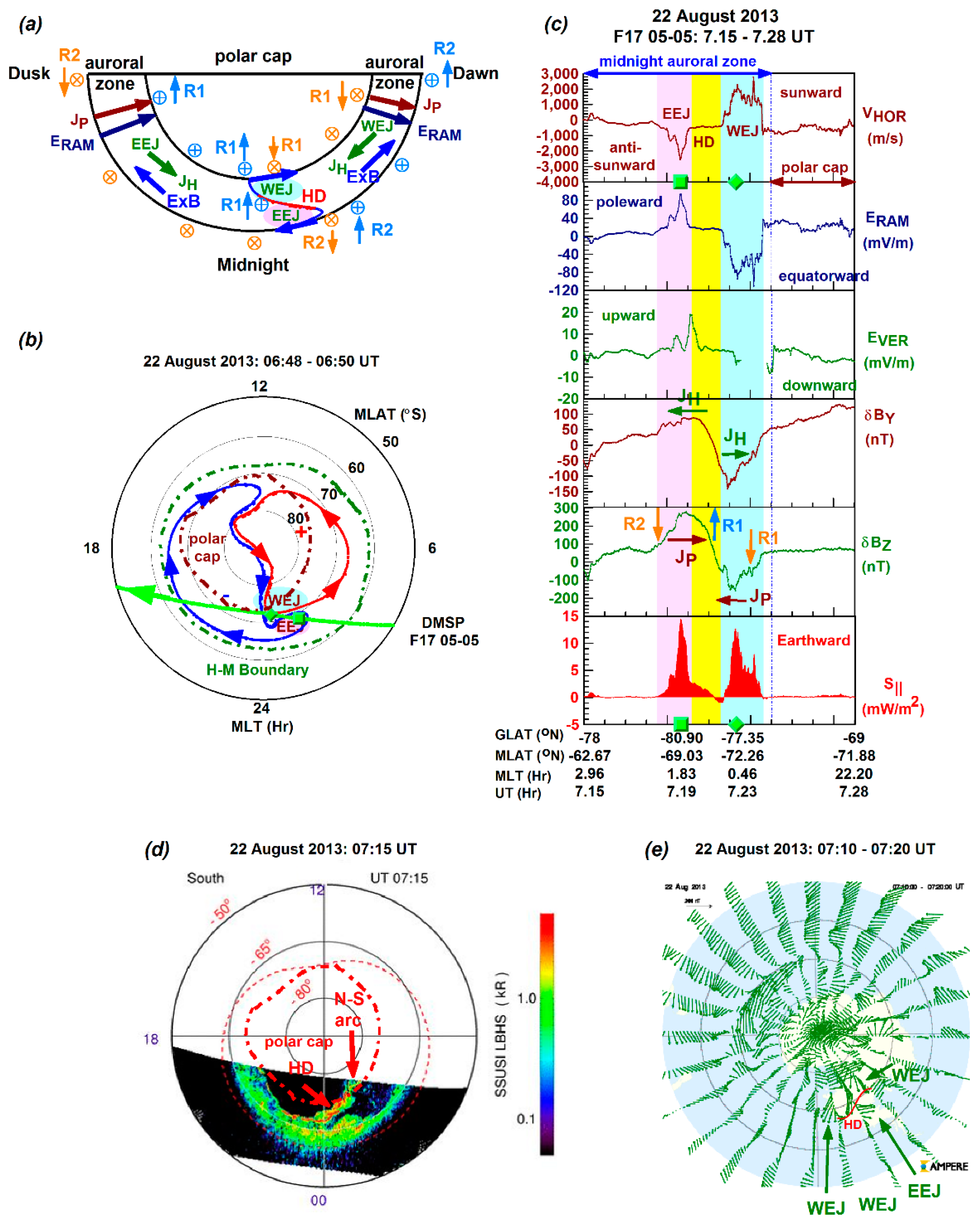

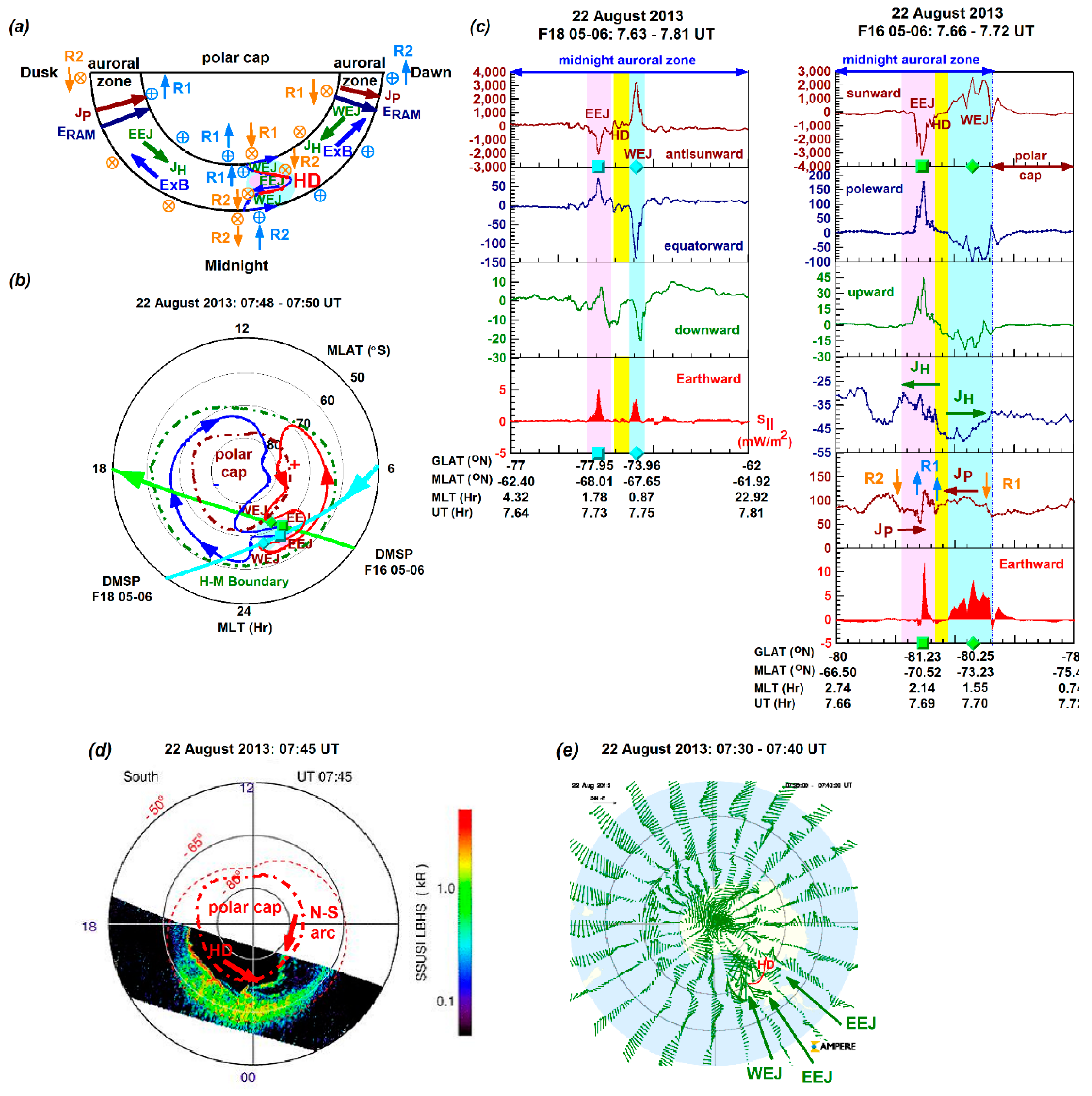

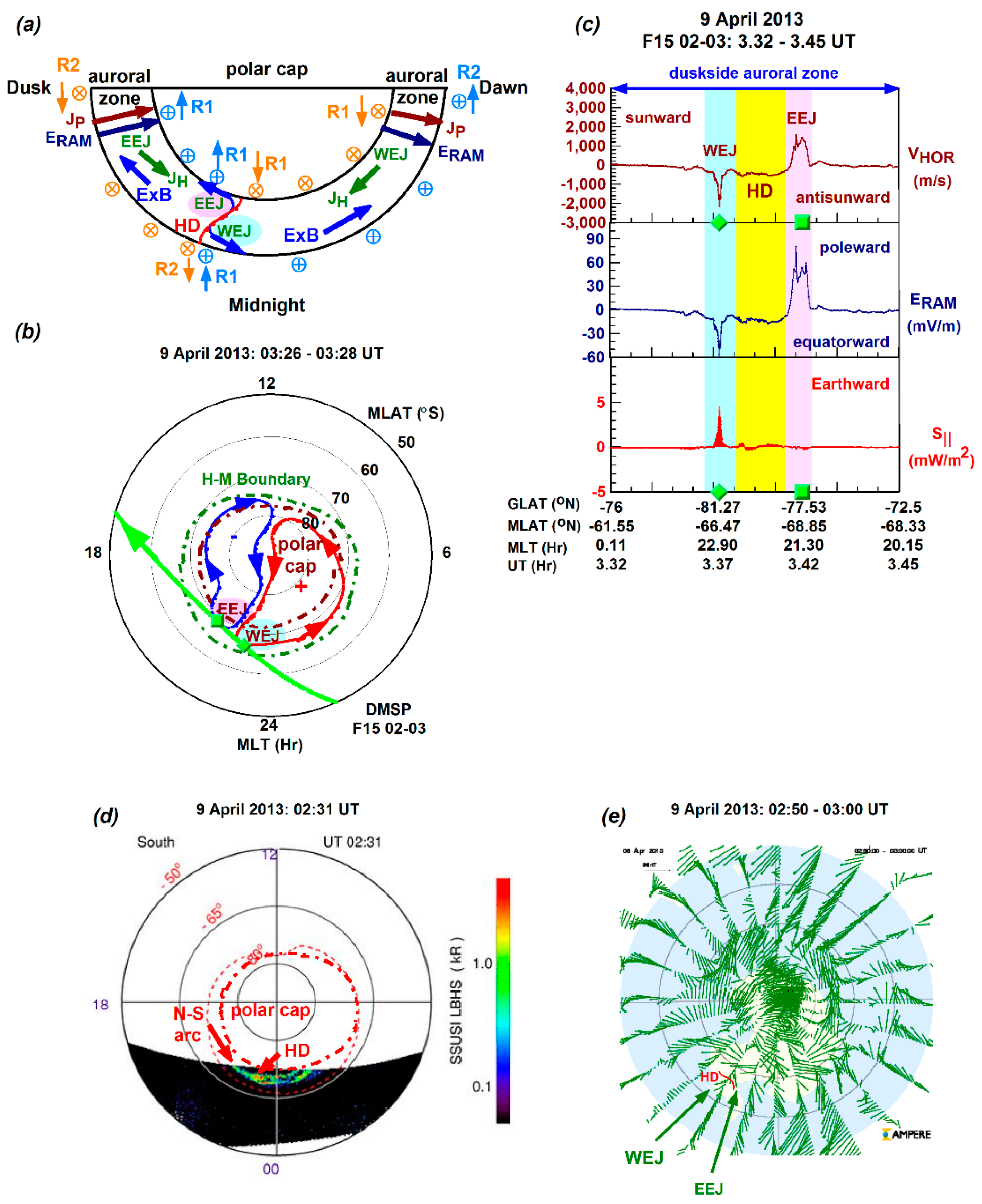

3.1. Dawnside Harang Discontinuity and Clockwise Rotations Observed in Event-1

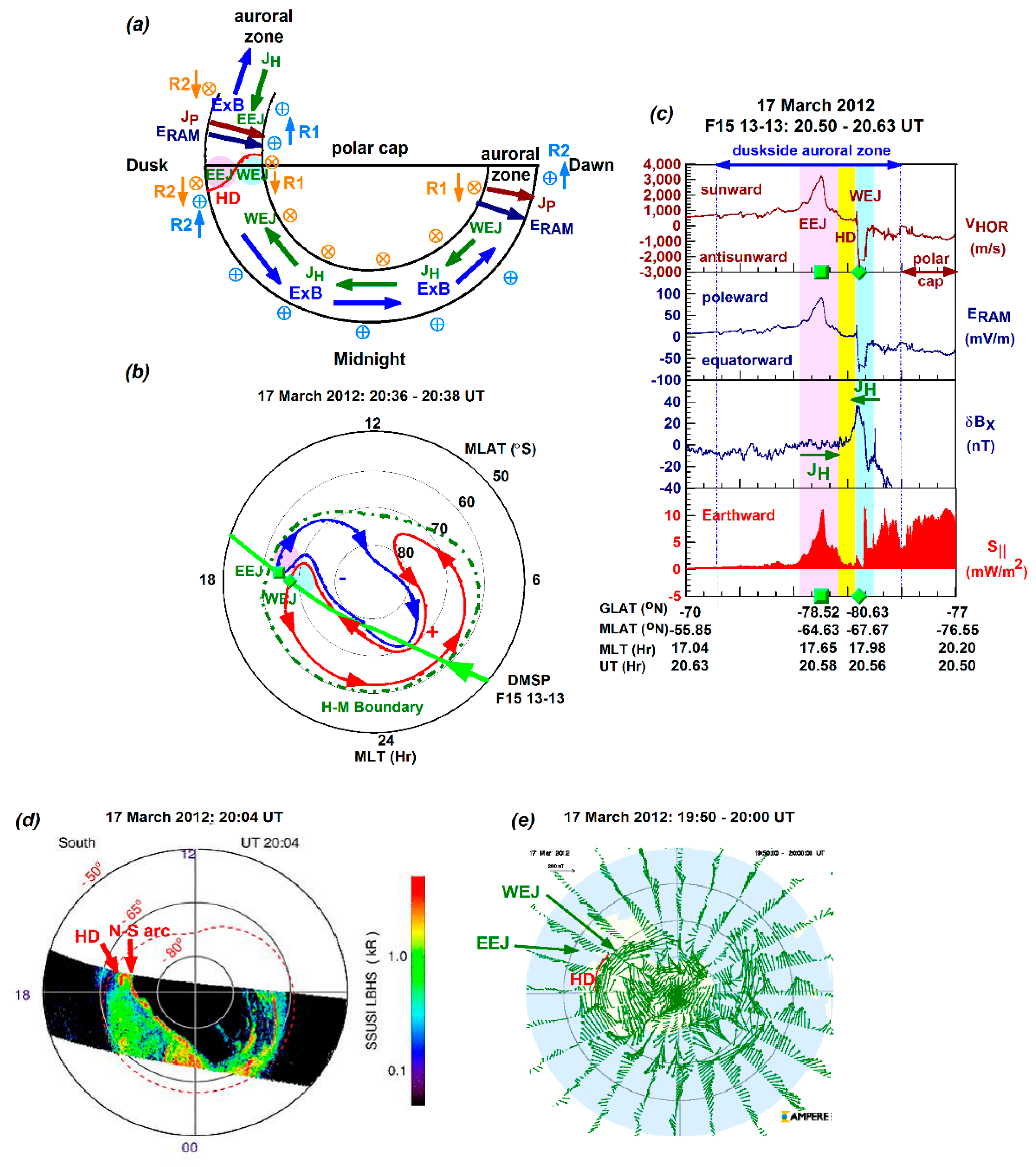

3.2. Duskside Harang Discontinuity and Anticlockwise Rotation Observed in Event-2

3.3. Duskside Harang Discontinuity and Clockwise Rotation Observed in Event-3

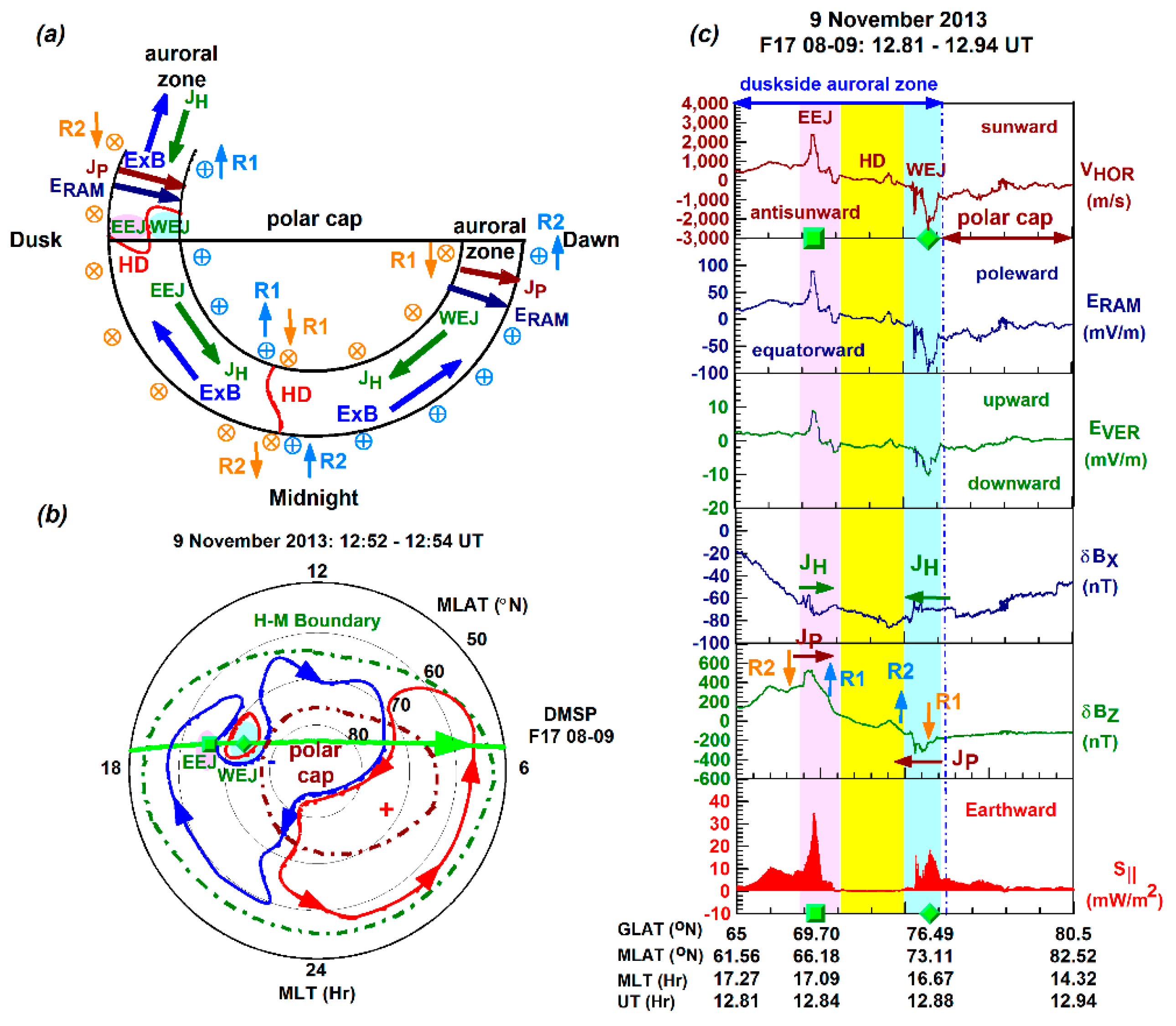

3.4. Harang Discontinuity and Clockwise Rotation Observed in Event-4

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMPERE | Active Magnetosphere and Planetary Electrodynamics Response Experiment |

| ASI | All Sky Imager |

| DMSP | Defense Meteorological Satellite Program |

| EEJ | Eastward Electrojet |

| E field | Electric field |

| ERAM | along-the-track ram Electric field |

| EVER | cross-track vertical or radial Electric field |

| E-W | East-West |

| FACs | Field-Aligned Currents |

| GOES | Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites |

| HD | Harang Discontinuity |

| H-M | Heppner-Maynard |

| JH | Hall currents |

| JP | Pedersen currents |

| M-I | Magnetosphere-Ionosphere |

| MLT | Magnetic Local Time |

| N-S | North-South |

| R1 | Region 1 |

| R2 | Region 2 |

| S|| | Poynting Flux |

| SAID | Sub-Auroral Ion Drifts |

| SSUSI | Special Sensor Ultraviolet Spectrographic Imager |

| STEVE | Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement |

| SuperDARN | Super Dual Auroral Radar Network |

| VHOR | cross-track horizontal drift velocity |

| WEJ | Westward Electrojet |

References

- Heppner, J.P. The Harang discontinuity in auroral belt; Ionospheric currents. Geofys. Publ. 1972, 29, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, N.C. Electric field measurements across the Harang discontinuity. Journal of Geophysical Research 1974, 79, 4620–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harang, L. The mean field of disturbance of polar geomagnetic storms. Terrestrial Magnetism and Atmospheric Electricity 1946, 51, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, A.S.; Cowley, S.W.H.; Brown, M.J.; Pinnock, M.; Simmons, D.A. Dawn-dusk (y) component of the interplanetary magnetic field and the local time of the Harang discontinuity. Planetary and Space Science 1984, 32, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauristie, K.; Syrjäsuo, M.; Amm, O.; Viljanen, A.; Pulkkinen, T.; Opgenoorth, H. A statistical study of evening sector arcs and electrojets. Advances in Space Research 2001, 28, 1605–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungey, J.W. Interplanetary magnetic field and the auroral zones. Physical Review Letters 1961, 6, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, J.P. Empirical models of high-latitude electric fields. Journal of Geophysical Research 1977, 82, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamide, Y. On current continuity at the Harang discontinuity. Planetary and Space Science 1978, 26, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, M.M.; Iversen, I.B.; D’Angelo, N. Measurements of high-latitude ionospheric electric fields by means of balloon-borne sensors. Journal of Geophysical Research 1976, 81, 3821–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, H.E.J.; Pulkkinen, T.I. Midnight velocity shear zone and the concept of Harang discontinuity. Journal of Geophysical Research 1995, 100, 9539–9547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, G.M.; Spiro, R.W.; Wolf, R.A. The physics of the Harang discontinuity. Journal of Geophysical Research 1991, 96, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezniak, T.; Winckler, J. Experimental study of magnetospheric motions and the acceleration of energetic electrons during substorms. Journal of Geophysical Research 1970, 75, 7075–7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasofu, S.-I. The development of the auroral substorm. Planetary and Space Science 1964, 12, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, L.R.; Zesta, E.; Samson, J.C.; Reeves, G.D. Auroral disturbances during the January 10, 1997 magnetic storm. Geophysical Research Letters 2000, 27, 3237–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, L.R.; Nagai, T.; Blanchard, G.T.; Samson, J.C.; Yamamoto, T.; Mukai, T.; Nishida, A.; Kokubun, S. Association between Geotail plasma flows and auroral poleward boundary intensifications observed by CANOPUS photometers. Journal of Geophysical Research 1999, 104, 4485–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeev, V.A.; Sauvaud, J.-A.; Popescu, D.; Kovrazhkin, R.A.; Liou, K.; Newell, P.T.; Brittnacher, M.; Parks, G.; Nakamura, R.; Mukai, T.; et al. Multiple-spacecraft observation of a narrow transient plasma jet in the Earth’s plasma sheet. Geophysical Research Letters 2000, 27, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, R.; Baumjohann, W.; Schödel, R.; Brittnacher, M.; Sergeev, V.A.; Kubyshkina, M.; Mukai, T.; Liou, K. Earthward flow bursts, auroral streamers, and small expansions. Journal of Geophysical Research 2001, 106, 10791–10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zesta, E.; Lyons, L.; Wang, C.-P.; Donovan, E.; Frey, H.; Nagai, T. Auroral poleward boundary intensifications (PBIS): Their two-dimensional structure and associated dynamics in the plasma sheet. Journal of Geophysical Research 2006, 111, A05201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weygand, J.M.; McPherron, R.L.; Frey, H.; Amm, O.; Kauristie, K.; Viljanen, A.T.; Koistinen, A. Relation of substorm onset to Harang discontinuity. Journal of Geophysical Research 2008, 113, A04213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Lyons, L.R.; Nicolls, M.J.; Heinselman, C.J.; Mende, S.B. Nightside ionospheric electrodynamics associated with substorms: PFISR and THEMIS ASI observations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2009, 114, A12301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Lyons, L.R.; Wang, C.-P.; Boudouridis, A.; Ruohoniemi, J.M.; Anderson, P.C.; Dyson, P.L.; Devlin, J.C. On the coupling between the Harang reversal evolution and substorm dynamics: A synthesis of SuperDARN, DMSP, and IMAGE observations. Journal of Geophysical Research 2009, 114, A01205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, Y.; Lyons, L.; Zou, S.; Angelopoulos, V.; Mende, S. Substorm triggering by new plasma intrusion: THEMIS all-sky imager observations. Journal of Geophysical Research 2010, 115, A07222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, I.; Lovell, B.C. Magnetosphere–Ionosphere Conjugate Harang Discontinuity and Sub-Auroral Polarization Streams (SAPS) Phenomena Observed by Multipoint Satellites. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, L.R.; Lee, D.-Y.; Wang, C.-P.; Mende, S.B. Relation of substorm disturbances triggered by abrupt solar-wind changes to physics of plasma sheet transport, in International Conference on Substorms-8, ed. by M. Syrjasuo and E. Donovan, p. 165, Institute for Space Research, University of Calgary, 2006.

- Gkioulidou, M.; Wang, C.-P.; Lyons, L.R.; Wolf, R.A. Formation of the Harang reversal and its dependence on plasma sheet conditions: Rice convection model simulations. Journal of Geophysical Research 2009, 114, A07204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, F.J.; Hairston, M. Large-scale convection patterns observed by DMSP. Journal of Geophysical Research 1994, 99, 3–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilcommons, L.M.; Knipp, D.J.; Hairston, M.; Coley, W.R. DMSP Poynting flux: Data processing and inter-spacecraft comparisons. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2022, 127, e2022JA030299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Burke, W.J. Transient sheets of field-aligned current observed by DMSP during the main phase of a magnetic superstorm. Journal of Geophysical Research 2004, 109, A06303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Su, Y.; Sutton, E.K.; Weimer, D.R.; Davidson, R.L. Energy coupling during the August 2011 magnetic storm. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2014, 119, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, L.J.; Meng, C.I.; Fountain, G.H.; Ogorzalek, B.S.; Darlington, E.H.; Goldsten, J.; Kusnierkiewicz, D.Y.; Lee, S.C.; Linstrom, L.A.; Maynard, J.J.; et al. Special Sensor UV Spectrographic Imager (SSUSI): An instrument description. Instrumentation for Planetary and Terrestrial Atmospheric Remote Sensing, SPIE, 1992, 1745, 2–16. [CrossRef]

- Paxton, L.J.; Morrison, D.; Zhang, Y.; Kil, H.; Wolven, B.; Ogorzalek, B.S.; Humm, D.C.; Meng, C.-I. Validation of remote sensing products produced by the Special Sensor Ultraviolet Scanning Imager (SSUSI): A far UV-imaging spectrograph on DMSP F-16. Proceedings 2002, 4485, Optical Spectroscopic Techniques, Remote Sensing, and Instrumentation for Atmospheric and Space Research IV, (30 January 2002). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.J.; Korth, H.; Waters, C.L.; Green, D.L.; Merkin, V.G.; Barnes, R.J.; Dyrud, L.P. Development of large-scale birkeland currents determined from the active magnetosphere and planetary electrodynamics response experiment. Geophysical Research Letters 2014, 41, 3017–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.J.; Olson, C.N.; Korth, H.; Barnes, R.J.; Waters, C.L.; Vines, S.K. Temporal and spatial development of global Birkeland currents. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2018, 123, 4785–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, R.A.; Bristow, W.A.; Sofko, G.J.; Senior, C.; Cerisier, J.C.; Szabo, A. Super dual auroral radar network radar imaging of dayside high-latitude convection under northward interplanetary magnetic field: Toward resolving the distorted two-cell versus multicell controversy. Journal of Geophysical Research 1995, 100, 19661–19674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisham, G.; Lester, M.; Milan, S.E.; Freeman, M.P.; Bristow, W.A.; Grocott, A.; McWilliams, K.A.; Ruohoniemi, J.M.; Yeoman, T.K.; Dyson, P.L.; et al. A decade of the Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN): Scientific achievements, new techniques and future directions. Surveys in Geophysics 2007, 28, 33–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, N.; Ruohoniemi, J.M.; Lester, M.; Baker, J.B.H.; Koustov, A.V.; Shepherd, S.G.; Chisham, G.; Hori, T.; Thomas, E.G.; Makarevich, R.A.; et al. Review of the accomplishments of mid-latitude Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN) HF radars. Progress in Earth and Planetary Science 2019, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, J.P.; Maynard, N.C. Empirical high-latitude electric field models. Journal of Geophysical Research 1987, 92, 4467–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walach, M.-T.; Grocott, A.; Thomas, E.G.; Staples, F. Dusk-Dawn Asymmetries in SuperDARN Convection Maps. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2022, 127, e2022JA030906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imber, S.M.; Milan, S.E.; Lester, M. The Heppner-Maynard Boundary measured by SuperDARN as a proxy for the latitude of the auroral oval. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2013, 118, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleimenova, N.G.; Gromova, L.I.; Gromov, S.V.; Malysheva, L.M.; Despirak, I.V. ‘Polar’ Substorms and the Harang Discontinuity. Geomagnetism and Aeronomy 2024, 64, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svaldi, V.; Matsuo, T.; Kilcommons, L.; Gallardo-Lacourt, B. (). High-latitude ionospheric electrodynamics during STEVE and non-STEVE substorm events. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2023, 128, e2022JA030277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, Y.; Yang, J.; Weygand, J.M.; Wang, W.; Kosar, B.; Donovan, E.F.; Angelopoulos, V.; Paxton, L.J.; Nishitani, N. Magnetospheric conditions for STEVE and SAID: Particle injection, substorm surge, and field-aligned currents. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2020, 125, e2020JA027782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasofu, S.-I. Where is the magnetic energy for the expansion phase of auroral substorms accumulated? 2. The main body, not the magnetotail. Journal of Geophysical Research Space Physics 2017, 122, 8479–8487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinevich, A.; Chernyshov, A.; Chugunin, D.; Clausen, L.B.N.; Miloch, W.J.; Mogilevsky, M.M. Stratified subauroral ion drift (SSAID). Stratified subauroral ion drift (SSAID). Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2023, 128, e2022JA031109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotova, D.S.; Sinevich, A.A.; Chernyshov, A.A.; Chugunin, D.V.; Jin, Y.; Miloch, W.J. Strong turbulent flow in the subauroral region in the Antarctic can deteriorate satellite-based navigation signals. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, E.A.; Donovan, E.; Nishimura, Y.; Case, N.A.; Gillies, D.M.; Gallardo-Lacourt, B.; Archer, W.E.; Spanswick, E.L.; Bourassa, N.; Connors, M.; et al. New science in plain sight: Citizen scientists lead to the discovery of optical structure in the upper atmosphere. Science Advances 2018, 4, eaaq0030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Lacourt, B.; Nishimura, Y.; Donovan, E.; Gillies, D.M.; Perry, G.W.; Archer, W.E.; Nava, O.A.; Spanswick, E.L. A Statistical analysis of STEVE. Journal of Geophysical Research Space Physics 2018, 123, 9893–9905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, D.M.; Liang, J.; Gallardo-Lacourt, B.; Donovan, E. New insight into the transition from a SAR arc to STEVE. Geophysical Research Letters 2023, 50, e2022GL101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.C.; Heelis, R.A.; Hanson, W.B. The ionospheric signatures of rapid subauroral ion drifts. Journal of Geophysical Research 1991, 96, 5–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, Y.L.; Ponomarev, V.N.; Zosimova, A.G. Plasma convection in the polar ionosphere. Annales de Geophysique 1974, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mishin, E.V. Interaction of substorm injections with the subauroral geospace: 1. Multispacecraft observations of SAID. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2013, 118, 5782–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, E.; Streltsov, A. On the kinetic theory of subauroral arcs. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2022, 127, e2022JA030667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, E.; Streltsov, A. The inner structure of STEVE-linked SAID. Geophysical Research Letters 2023, 50, e2023GL102956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, E.V.; Streltsov, A.V. Toward the unified theory of SAID-linked subauroral arcs. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2024, 129, e2023JA032196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinevich, A.A.; Chernyshov, A.A.; Chugunin, D.V.; Klimenko, M.V.; Panchenko, V.A.; Yakimova, G.A.; Timchenko, A.V.; Miloch, W.J.; Mogilevsky, M.M. Multi-instrument approach to study polarization jet/SAID and STEVE. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2024, 129, e2024JA033222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Lei, J.; Liu, H.-L.; Maute, A.; Hagan, M.E. Variations of the nighttime thermospheric mass density at low and middle latitudes. Journal of Geophysical Research 2010, 115, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).