Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Teacher Competence in Teacher Education

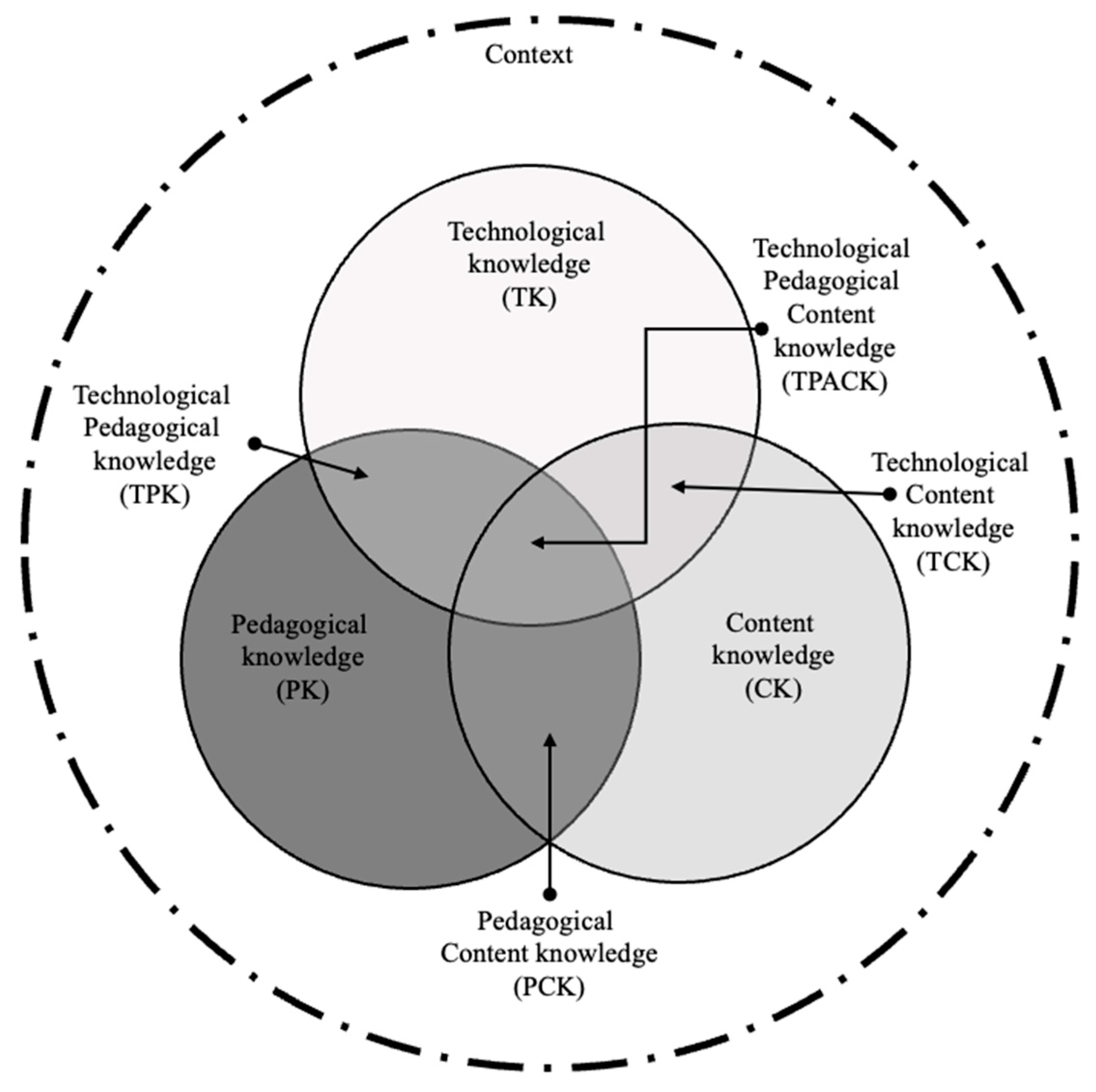

2.2. TPACK Framework

2.2.1. TCK-Related Reasons for Selecting Digital Resources

2.2.2. TPK-Related Reasons for Selecting Digital Resources

| TPACK Comp. | Description of code (#) | DigCompEdu [63], TPACK [23], teaching core practices Grossman [61] | Studies supporting the code |

| TCK-x | Different/real world representations (TCK-1/2) |

„newer technologies often afford newer and more varied representations” [23] (p. 1028) | [19,52] |

| Dynamic representation (TCK-3) | - | [18,64] | |

| In-/decrease, Modify extraneous cognitive load (TCK-4/5/6) | - | [48,54] | |

| TPK-x | Motivation (TPK-1) | „... Teachers design and sequence lessons [...] while keeping students engaged...” [61] (p. 167) | [56,59,60,65] |

| Self-directed learning (TPK-2) | „To use digital technologies to support learners’ self-regulated learning” [63] (p. 21) | [18,60,66] | |

| Try out, explore, discover (TPK-3) |

„...digital technologies can be used to facilitate learners” [...], e.g., when exploring a topic…” [63] (p. 22) | [18,21,61] | |

| Differentiation, inclusion (TPK-4) |

„...To ensure accessibility to learning resources and activities, for all learners, including those with special needs…” [63] (p. 22) | [4,19,21,42] | |

| Teacher efficiency (TPK-5) | „...composing and selecting assessments, teachers consider validity, fairness, and efficiency.” [61] (p.168) | [33,48,60] | |

| Distracting to learners (TPK-6) | - | [48,57] | |

| TPACK | Combination of TCK, TPK | „TPCK is the basis of good teaching with technology [...] pedagogical techniques that use technologies in constructive ways…” [23] (p. 1029) | [48,67] |

3. Materials and Methods

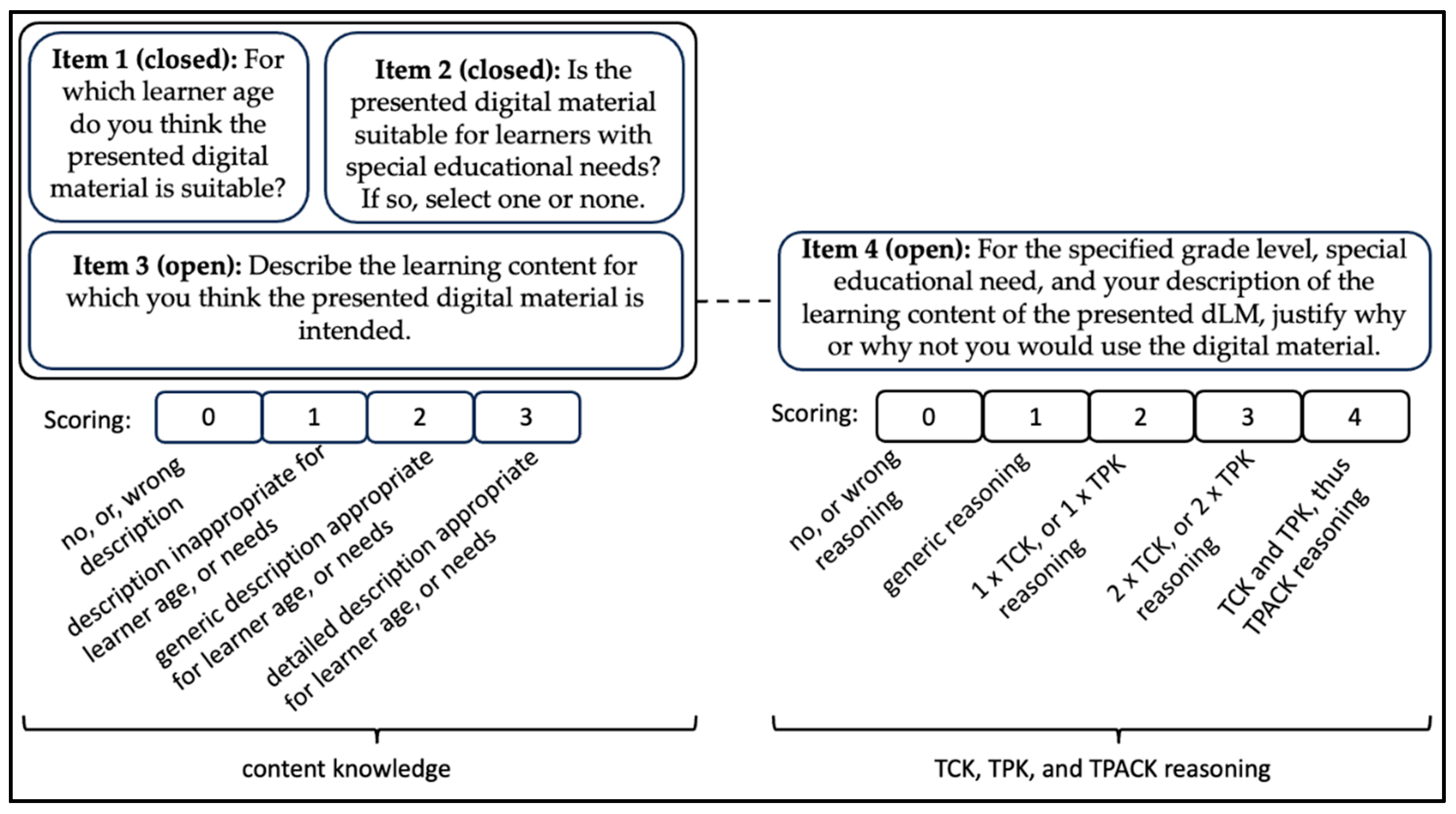

3.1. Genesis of Items for Assessing the Skill of „Selecting dLM”

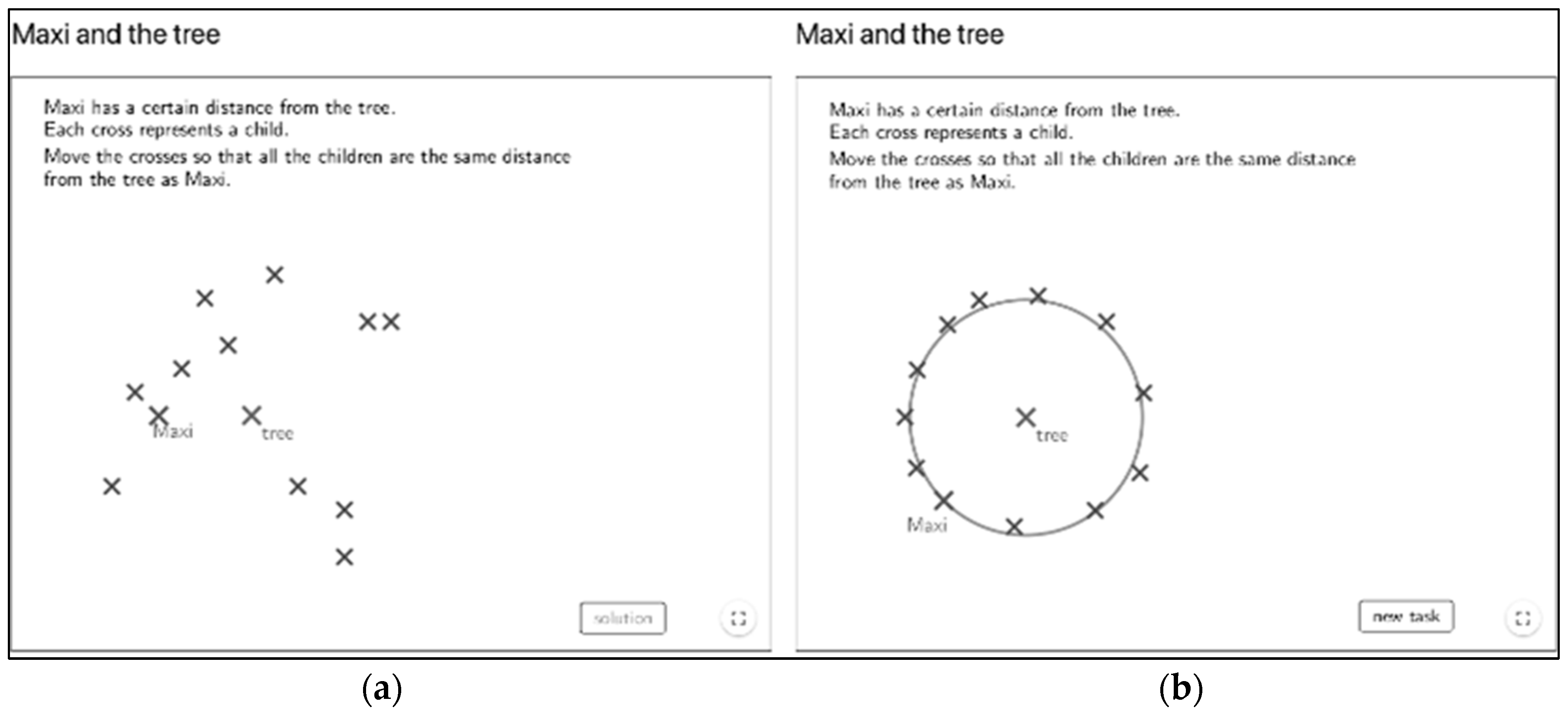

3.2. Specific dLMs Used in the Studies for Evaluating the Developed Items

3.3. Scoring of the Items Used for Assessing the Skill of „Selecting dLM”

3.4. Participants of Studies 1 and 2

4. Results

4.1. RQ1: How Can „Selecting dLM” Be Assessed Using Open-Text Items?

4.2. RQ2: What Insights Can Be Gained Using the Developed Items with a Larger Sample of Pre-Service Mathematics Teachers?

4.2.1. RQ 2.1: Can the Developed Items for „Selecting dLM” Assess Different Levels Regarding the Number of Semesters of Study, and Are the Results Distinguishable from TPACK Self-Report Results?

4.2.2. RQ2.2: What is the Relationship Between Learning Content Knowledge (Items 1-3) and the Rationale (item 4) for „Selecting a dLM”?

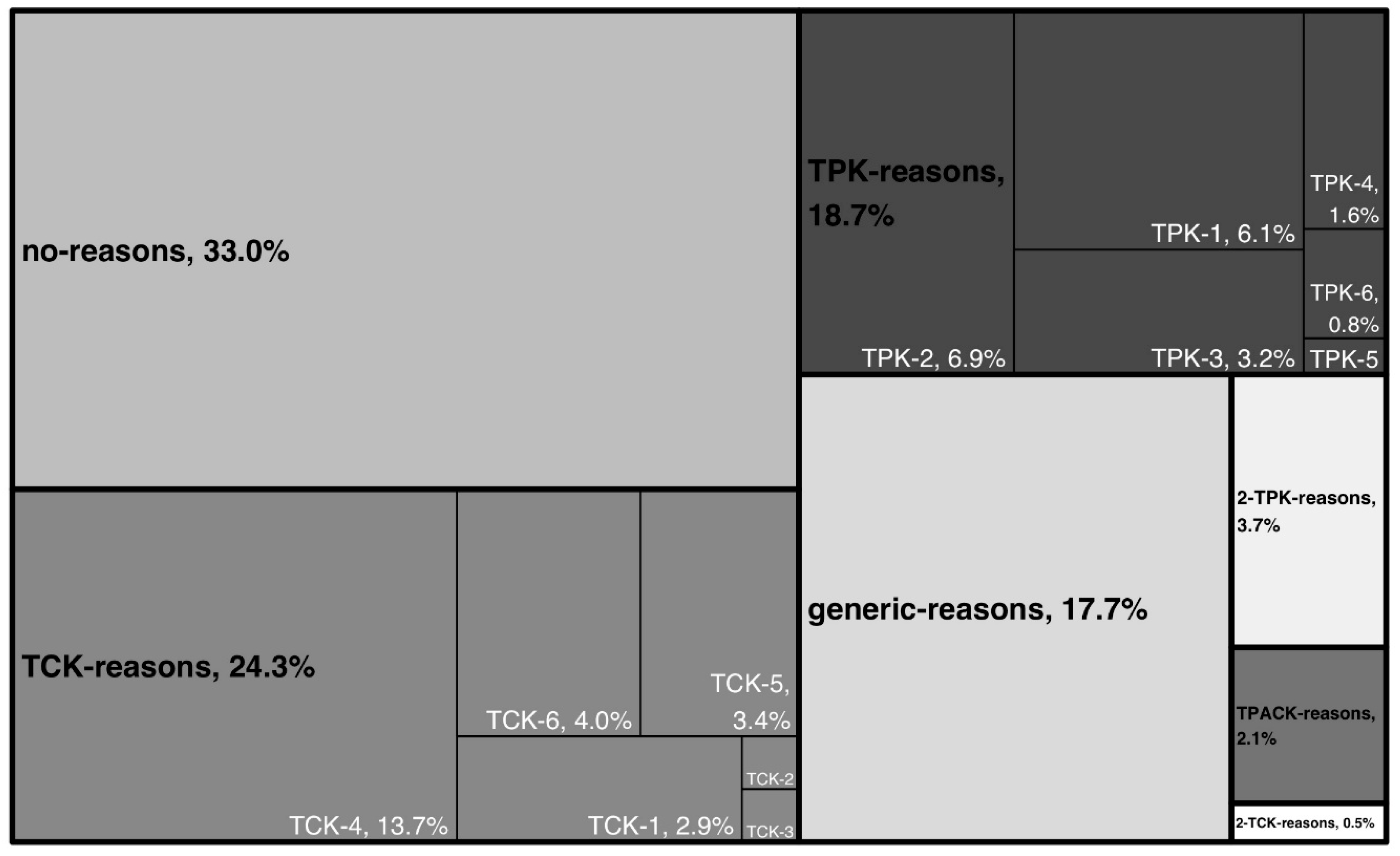

4.2.3. What Specific Reasoning Is Considered When Selecting a dLM?

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion RQ1: How Can „Selecting dLM” Be Assessed Using Open-Text Items?

5.2. Discussion RQ2.x: What Insights Can Be Gained Using the Developed Items with a Larger Sample of Pre-Service Mathematics Teachers?

5.3. Consequences for Teacher Education and the Development of Selecting dLM

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| score | dLM1 (circle, and property of radius) [76] | dLM2 (symmetry and axis of symmetry) [71] | dLM3 (generate bar charts) [72] | dLM4 (arithmetic mean) [73] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, or wrong description (score 0) | „geometry, shapes, figures” | „spatial thinking“ | „visualization, sizes and quantities “ | „probability“ |

| description inappropriate for learner age, or needs (score1) | 7-8’th grade and no special educational needs; „circles and the properties of circles (radius...)” | 7-8’th grade and no FSP„ symmetry “ | 1-2’nd grade and learning disabilities „bar charts“ | 7-8’th grade and hearing impairment „arithmetic mean“ |

| generic description appropriate for learner age, or needs (score 2) |

„the content is useful for introducing circles and their radius.” | „axis mirroring“ | „bar charts“ | „arithmetic mean“ |

| detailed description appropriate for learner age, or needs (score 3) |

„To introduce the circle. Pupils should be made aware that every point on the circle is exactly the same distance from the center.” | „the material presents that the dimensions of the mirrored object remain the same size when mirrored at a straight line.” | „It is about absolute frequencies and the creation of bar charts.“ | „The dLM evaluates students’ understanding of how to calculate the arithmetic mean, ... helping students to grasp the underlying principles of the calculation.“ |

Appendix A.2

| score | dLM1 (circle, and property of radius) [76] | dLM2 (symmetry and axis of symmetry) [71] | dLM3 (generate bar charts) [72] | dLM4 (arithmetic mean) [73] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no, or wrong reasoning (score 0) |

„ I don’t see much point in the dLM“ | „there are better visual examples “ | „would rather do it analogue.“ | „I don’t know“ |

| generic reasoning (score1) |

„a good concept that combines math with technology“ | „good representation of the principle of symmetry“ | „simpel und nice“ | „a good task for calculating“ |

| 1 x TCK, or 1 x TPK reasoning (score 2) |

„I wouldn’t use the learning environment in a setting where students need support. It requires a lot of cognitive skills to comprehend the task and be able to visualize it...“ | „It is fun and motivating for the children to watch how the butterfly can move its wings“ | „It is a good activity to check whether students understand the representation of the bar chart without having to draw a chart themselves (saves time).“ | „...learners can all work self-directed, there are solution hints...“ |

| 2 x TCK, or 2 x TPK reasoning (score 3) |

„ Learners self-directed how it is possible to solve the task and thus learn an important property of the circle (radius) in a playful way “ | „Students learn about symmetries through play, Students can learn about the properties of symmetries through experimentation, which would be more difficult without digital media“ | „...motivational, context accessible to learners...“ | „...as everyone can work on the tasks at their own pace and it can be a motivating factor for the children to work digitally and see results immediately...“ |

| TCK and TPK, thus TPACK reasoning (score 4) |

„ I would use this learning environment because it is enactive and visual learning that actively engages students in the learning process. Through the concrete task of positioning x in a circle around the tree, the children experience geometric concepts such as radius, center, and circle shape. This not only promotes an understanding of abstract mathematical concepts, but also spatial awareness and the ability to recognize connections“ | „ I wouldn’t use the learning environment... For example, the task is too abstract for learners or offer too few differentiated approaches to understand the core of axial symmetry. If there’s no way to adapt the task to different learning levels, some students might be overwhelmed or under-challenged.“ | „...without requiring learners to do a lot of drawing. Learners can easily experiment and check their solutions independently. Doing this on paper would waste lesson time and verification of results is time consuming for teachers...“ | „...It assesses students’ understanding of calculating the arithmetic mean. Students are forced to rethink their learned knowledge of calculation and can thus better reflect on the arithmetic mean calculation. However, I view this learning environment more as a test to determine the extent to which students have internalized the subject matter they have learned. “ |

References

- Drijvers, P.; Sinclair, N. The Role of Digital Technologies in Mathematics Education: Purposes and Perspectives. ZDM Mathematics Education 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roblyer, M.D.; Hughes, J.E. Integrating Educational Technology into Teaching: Transforming Learning across Disciplines; Eighth Edition.; Pearson Education, Inc: New York, 2019; ISBN 978-0-13-474641-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, M.; Marín, V.I.; Dolch, C.; Bedenlier, S.; Zawacki-Richter, O. Digital Transformation in German Higher Education: Student and Teacher Perceptions and Usage of Digital Media. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 2018, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhandl, R.; Houghton, T.; Lindenbauer, E.; Mayerhofer, M.; Lavicza, Z.; Hohenwarter, M. Integrating Technologies Into Teaching and Learning Mathematics at the Beginning of Secondary Education in Austria. EURASIA J Math Sci Tech Ed 2021, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, M.C. The Future of Mathematics Education since COVID-19: Humans-with-Media or Humans-with-Non-Living-Things. Educ Stud Math 2021, 108, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Qadri, M.A.; Suman, R. Understanding the Role of Digital Technologies in Education: A Review. Sustainable Operations and Computers 2022, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.G.; Helm, C. COVID-19 and Schooling: Evaluation, Assessment and Accountability in Times of Crises—Reacting Quickly to Explore Key Issues for Policy, Practice and Research with the School Barometer. Educ Asse Eval Acc 2020, 32, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, K.; Burtniak, K.; Rüth, M. Online Learning during the Covid-19 Pandemic: How University Students’ Perceptions, Engagement, and Performance Are Related to Their Personal Characteristics. Curr Psychol 2024, 43, 16711–16730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, J.; Llinares, S.; Borba, M.C. Transformation of the Mathematics Classroom with the Internet. ZDM Mathematics Education 2020, 52, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD The Future of Education and Skills Education 2030; OECD: Paris, France, 2018.

- Heine, S.; König, J.; Krepf, M. Digital Resources as an Aspect of Teacher Professional Digital Competence: One Term, Different Definitions – a Systematic Review. Education and Information Technologies 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigand, H.-G.; Trgalova, J.; Tabach, M. Mathematics Teaching, Learning, and Assessment in the Digital Age. ZDM Mathematics Education 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark-Wilson, A.; Robutti, O.; Thomas, M. Teaching with Digital Technology. ZDM Mathematics Education 2020, 52, 1223–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenbauer, E.; Infanger, E.-M.; Lavicza, Z. Enhancing Mathematics Education through Collaborative Digital Material Design: Lessons from a National Project. EUR J SCI MATH ED 2024, 12, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonscherowski, P.; Rott, B. A Systematic Review of the Literature on TPACK Instruments Used with Pre-Service Teachers from 2017 to 2023 Focused on Selecting Digital Resources. Journal of Computers in Education Accepted.

- König, J.; Heine, S.; Kramer, C.; Weyers, J.; Becker-Mrotzek, M.; Großschedl, J.; Hanisch, C.; Hanke, P.; Hennemann, T.; Jost, J.; et al. Teacher Education Effectiveness as an Emerging Research Paradigm: A Synthesis of Reviews of Empirical Studies Published over Three Decades (1993–2023). Journal of Curriculum Studies 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.H.; Xin, T.; Guo, S.; Wang, X. Achieving Excellence and Equality in Mathematics: Two Degrees of Freedom? Journal of Curriculum Studies 2022, 54, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, F.; Leuders, T.; Loibl, K.; Nückles, M.; Beege, M.; Boelmann, J.M. Learning Mechanisms Explaining Learning With Digital Tools in Educational Settings: A Cognitive Process Framework. Educ Psychol Rev 2024, 36, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Griffith, R.; Crawford, L. TPACK in Special Education: Preservice Teacher Decision Making While Integrating iPads into Instruction. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education (CITE Journal) 2017, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, S.-S.; Yeh, H.-C. Fostering EFL Teachers’ CALL Competencies through Project-Based Learning. Educational Technology & Society 2019, 22, 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Handal, B.; Campbell, C.; Cavanagh, M.; Petocz, P. Characterising the Perceived Value of Mathematics Educational Apps in Preservice Teachers. Mathematics Education Research Journal 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, T.; Leppänen, U.; Hyypiä, M.; Sointu, E.; Smits, A.; Tondeur, J. Fresh Perspectives on TPACK: Pre-Service Teachers’ Own Appraisal of Their Challenging and Confident TPACK Areas. Educ Inf Technol 2020, 25, 2823–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record 2005, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M.J.; Shin, T.S.; Mishra, P. How Do We Measure TPACK? Let Me Count the Ways. In A Research Handbook on Frameworks and Approaches; Ronau, R.N., Rakes, C.R., Niess, M.L., Eds.; IGI Global, 2011; pp. 16–31 ISBN 978-1-60960-750-0.

- Schmid, M.; Brianza, E.; Mok, S.Y.; Petko, D. Running in Circles: A Systematic Review of Reviews on Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK). Computers & Education 2024, 214, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya Cirit, D.; Canpolat, E. A Study on the Technological Pedagogical Contextual Knowledge of Science Teacher Candidates across Different Years of Study. Education and Information Technologies 2019, 24, 2283–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kotzebue, L. Beliefs, Self-Reported or Performance-Assessed TPACK: What Can Predict the Quality of Technology-Enhanced Biology Lesson Plans? Journal of Science Education and Technology 2022, 31, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachner, A.; Fabian, A.; Franke, U.; Preiß, J.; Jacob, L.; Führer, C.; Küchler, U.; Paravicini, W.; Randler, C.; Thomas, P. Fostering Pre-Service Teachers’ Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK): A Quasi-Experimental Field Study. Computers & Education 2021, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Harp, C. Examining Preservice Teachers’ TPACK, Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Perceptions of Teamwork in a Stand-Alone Educational Technology Course Using Flipped Classroom or Flipped Team-Based Learning Pedagogies. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 2020, 36, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouza, C.; Nandakumar, R.; Yilmaz Ozden, S.; Karchmer-Klein, R. A Longitudinal Examination of Preservice Teachers’ Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge in the Context of Undergraduate Teacher Education. Action in Teacher Education 2017, 39, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekkan, Z.T.; Ünal, G. Technology Use: Analysis of Lesson Plans on Fractions in an Online Laboratory School. In Proceedings of the 45th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education; Fernández, C., Llinares, S., Gutiérrez, A., Planas, N., Eds.; Alicante/Spain, 2022; Vol. 4; pp. 410–2. [Google Scholar]

- Gonscherowski, P.; Rott, B. Selecting Digital Technology: A Review of TPACK Instruments. In Proceedings of the 46th conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education; Vol. 2; Ayalon, M., Koichu, B., Leikin, R., Rubel, L., Tabach, M., Eds.; PME: Haifa, Israel, 2023; pp. 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, A.; Leatham, K.; Bailey, N.; Cayton, C.; Fye, K.; Lovett, J. Theoretically Framing the Pedagogy of Learning to Teach Mathematics with Technology. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education (CITE Journal) 2021, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Revuelta-Domínguez, F.-I.; Guerra-Antequera, J.; González-Pérez, A.; Pedrera-Rodríguez, M.-I.; González-Fernández, A. Digital Teaching Competence: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.; Hsu, Y.; Wu, H.; Hwang, F.; Lin, T. Developing and Validating Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge-practical TPACK through the Delphi Survey Technique. Brit J Educational Tech 2014, 45, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, P. Social Desirability Bias. In Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing; Sheth, J., Malhotra, N., Eds.; Wiley, 2010 ISBN 978-1-4051-6178-7.

- Safrudiannur Measuring Teachers’ Beliefs Quantitatively: Criticizing the Use of Likert Scale and Offering a New Approach, Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, 2020.

- Schmid, M.; Brianza, E.; Petko, D. Self-Reported Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) of Pre-Service Teachers in Relation to Digital Technology Use in Lesson Plans. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 115, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömeke, S.; Gustafsson, J.-E.; Shavelson, R.J. Beyond Dichotomies: Competence Viewed as a Continuum. Zeitschrift für Psychologie 2015, 223, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z. Powerful Knowledge, Educational Potential and Knowledge-Rich Curriculum: Pushing the Boundaries. Journal of Curriculum Studies 2022, 54, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Deng, J.; Sun, X.; Kaiser, G. The Relationship between Opportunities to Learn in Teacher Education and Chinese Preservice Teachers’ Professional Competence. Journal of Curriculum Studies 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, A. PISA 2022 Insights and Interpretations; OECD, 2023;

- Kaiser, G.; König, J. Competence Measurement in (Mathematics) Teacher Education and Beyond: Implications for Policy. High Educ Policy 2019, 32, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M.J.; Mishra, P.; Cain, W. What Is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)? Journal of Education 2013, 193, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educational Researcher 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Warr, M. Contextualizing TPACK within Systems and Cultures of Practice. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 117, 106673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabach, M.; Trgalová, J. Teaching Mathematics in the Digital Era: Standards and Beyond. In STEM Teachers and Teaching in the Digital Era; Ben-David Kolikant, Y., Martinovic, D., Milner-Bolotin, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-29395-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gonscherowski, P.; Rott, B. How Do Pre-/In-Service Mathematics Teachers Reason for or against the Use of Digital Technology in Teaching? Mathematics 2022, 10, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafini, F.C.; Lee, Y. Investigating Prospective Teachers’ TPACK and Their Use of Mathematical Action Technologies as They Create Screencast Video Lessons on iPads. TechTrends: Linking Research and Practice to Improve Learning 2021, 65, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmayr, D.; Ziernwald, L.; Reinhold, F.; Hofer, S.I.; Reiss, K.M. The Potential of Digital Tools to Enhance Mathematics and Science Learning in Secondary Schools: A Context-Specific Meta-Analysis. Computers & Education 2020, 153, 103897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.; Kynigos, C. Digital Artefacts as Representations: Forging Connections between a Constructionist and a Social Semiotic Perspective. Educ Stud Math 2014, 85, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solvang, L.; Haglund, J. How Can GeoGebra Support Physics Education in Upper-Secondary School -- A Review. Physics Education 2021, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Armella, L.; Hegedus, S.J.; Kaput, J.J. From Static to Dynamic Mathematics: Historical and Representational Perspectives. Educ Stud Math 2008, 68, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J.; van Merriënboer, J.J.G.; Paas, F. Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later. Educ Psychol Rev 2019, 31, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitasari, J.R.; Yamtinah, S.; Susilowati, E.; Kristyasari, M.L. Validation of TTMC Instrument of Pre-Service Chemistry Teacher’s TPACK Using Rasch Model Application. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2020, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.-S.; Yeh, H.-C. Fostering EFL Teachers’ CALL Competencies through Project-Based Learning. Educational Technology & Society 2019, 22, 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard, K.; Jäger-Biela, D.J.; König, J. Opportunities to Learn, Technological Pedagogical Knowledge, and Personal Factors of Pre-Service Teachers: Understanding the Link between Teacher Education Program Characteristics and Student Teacher Learning Outcomes in Times of Digitalization. Z Erziehungswiss 2023, 26, 653–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, I.; Boxtel, C.; Sleegers, P. Metacognitive Scaffolding in an Innovative Learning Arrangement. Instructional Science 2011, 39, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, Z.; Karabey, S.C. The Use of Immersive Technologies in Distance Education: A Systematic Review. Educ Inf Technol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüth, M.; Breuer, J.; Zimmermann, D.; Kaspar, K. The Effects of Different Feedback Types on Learning With Mobile Quiz Apps. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 665144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.L. Teaching Core Practices in Teacher Education; Core Practices in Education Series; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2018; ISBN 978-1-68253-187-7. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.; Putman, R. Special Education Teachers’ Experience, Confidence, Beliefs, and Knowledge about Integrating Technology. Journal of Special Education Technology 2020, 35, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redecker, C.; Punie, Y. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators – DigCompEdu. Publications Office of the European Union 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafini, F.C.; Lee, Y. Investigating Prospective Teachers’ TPACK and Their Use of Mathematical Action Technologies as They Create Screencast Video Lessons on iPads. TechTrends 2021, 65, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drijvers, P. Digital Technology in Mathematics Education: Why It Works (Or Doesn’t). In Selected Regular Lectures from the 12th International Congress on Mathematical Education; Cho, S.J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-17186-9. [Google Scholar]

- Drijvers, P.; Ball, L.; Barzel, B.; Heid, M.K.; Cao, Y.; Maschietto, M. Uses of Technology in Lower Secondary Mathematics Education: A Concise Topical Survey; Kaiser, G., Ed.; ICME-13 Topical Surveys; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-33665-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gonscherowski, P.; Rott, B. Measuring Digital Competencies of Pre-Service Teachers-a Pilot Study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 44th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education.

- Gonscherowski, P.; Rott, B. Digital Competencies of Pre-/in-Service Teachers-an Interview Study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twelfth Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education.

- Gonscherowski, P.; Rott, B. Instrument to Assess the Knowledge and the Skills of Mathematics Educators’ Regarding Digital Technology. In Proceedings of the Beiträge zum Mathematikunterricht 2022; Vol. 3; WTM: Frankfurt/Germany, 2022; p. 1424. [Google Scholar]

- GeoGebra Team Classroom Resources Available online:. Available online: https://www.geogebra.org/materials (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Schüngel, M. Bewege Den Schmetterling – GeoGebra Available online:. Available online: https://www.geogebra.org/m/zrj2zcam (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- FLINK Lieblingssport – GeoGebra Available online:. Available online: https://www.geogebra.org/m/v4xuvmhf (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- FLINK Welche Zahl Fehlt? – GeoGebra Available online:. Available online: https://www.geogebra.org/m/qqv3kxt6 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- BMBF Lehrplan der allgemeinen Sonderschule, Available online:. Available online: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2008_II_137/COO_2026_100_2_440355.html (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- MSB NRW Schulentwicklung NRW - Vorgaben Zieldifferente Bildungsgänge Available online:. Available online: https://www.schulentwicklung.nrw.de/lehrplaene/vorgaben-zieldifferente-bildungsgaenge/index.html (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Flink Maxi und der Baum – GeoGebra Available online:. Available online: https://www.geogebra.org/m/a4pppe7a (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Cohen, J. Quantitative Methods In Psychology: A Power Primer. Psychological Bulletin 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.V. Guidelines, Criteria, and Rules of Thumb for Evaluating Normed and Standardized Assessment Instruments in Psychology. Psychological Assessment 1994, 6, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Mayorga-Fernández, M.J.; Bravo-Agapito, J.; Escribano-Ortiz, D. Analysis of Teachers’ Pedagogical Digital Competence: Identification of Factors Predicting Their Acquisition. Tech Know Learn 2021, 26, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rott, B. Inductive and Deductive Justification of Knowledge: Epistemological Beliefs and Critical Thinking at the Beginning of Studying Mathematics. Educ Stud Math 2021, 106, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K. Univariate Normal Distribution. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2014; ISBN 978-94-007-0752-8. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res Sci Educ 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, N.; Knoef, M.; Lazonder, A.W. Technological and Pedagogical Support for Pre-Service Teachers’ Lesson Planning. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 2019, 28, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knievel, I.; Lindmeier, A.M.; Heinze, A. Beyond Knowledge: Measuring Primary Teachers’ Subject-Specific Competences in and for Teaching Mathematics with Items Based on Video Vignettes. Int J of Sci and Math Educ 2015, 13, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyers, J.; Kramer, C.; Kaspar, K.; König, J. Measuring Pre-Service Teachers’ Decision-Making in Classroom Management: A Video-Based Assessment Approach. Teaching and Teacher Education 2024, 138, 104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumanns, L.; Pohl, M. Leveraging ChatGPT for Problem Posing: An Exploratory Study of Pre-Service Teachers’ Professional Use of AI. 2024.

- Cai, J.; Rott, B. On Understanding Mathematical Problem-Posing Processes. ZDM Mathematics Education 2024, 56, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trixa, J.; Kaspar, K. Information Literacy in the Digital Age: Information Sources, Evaluation Strategies, and Perceived Teaching Competences of Pre-Service Teachers. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1336436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, H.; Kosiol, T.; Gonscherowski, P.; Rott, B.; Ufer, S.; Lindmeier, A. Using a Futures Study Methodology to Explore the Impact of New Technologies on Mathematics Teachers’ Core Practices and Professional Knowledge In Review.

- König, J.; Doll, J.; Buchholtz, N.; Förster, S.; Kaspar, K.; Rühl, A.-M.; Strauß, S.; Bremerich-Vos, A.; Fladung, I.; Kaiser, G. Pädagogisches Wissen versus fachdidaktisches Wissen?: Struktur des professionellen Wissens bei angehenden Deutsch-, Englisch- und Mathematiklehrkräften im Studium. Z Erziehungswiss 2018, 21, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J.; Heine, S.; Jäger-Biela, D.; Rothland, M. ICT Integration in Teachers’ Lesson Plans: A Scoping Review of Empirical Studies. European Journal of Teacher Education 2022, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurm, D.; Barzel, B. Teaching Mathematics with Technology: A Multidimensional Analysis of Teacher Beliefs. Educ Stud Math 2022, 109, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tan, J.S.H.; Pi, Z. The Spiral Model of Collaborative Knowledge Improvement: An Exploratory Study of a Networked Collaborative Classroom. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 2021, 16, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya Cirit, D.; Canpolat, E. A Study on the Technological Pedagogical Contextual Knowledge of Science Teacher Candidates across Different Years of Study. Education and Information Technologies 2019, 24, 2283–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwaningsih, E.; Nurhadi, D.; Masjkur, K. TPACK Development of Prospective Physics Teachers to Ease the Achievement of Learning Objectives: A Case Study at the State University of Malang, Indonesia. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2019, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.G. Methods for the Detection of Carelessly Invalid Responses in Survey Data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2016, 66, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Harp, C. Examining Preservice Teachers’ TPACK, Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and Perceptions of Teamwork in a Stand-Alone Educational Technology Course Using Flipped Classroom or Flipped Team-Based Learning Pedagogies. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 2020, 36, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouza, C.; Nandakumar, R.; Yilmaz Ozden, S.; Karchmer-Klein, R. A Longitudinal Examination of Preservice Teachers’ Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge in the Context of Undergraduate Teacher Education. Action in Teacher Education 2017, 39, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item no. | TPACK component |

Item wording | Type of item |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Content knowledge | For which learner age do you think the presented digital material is suitable? |

single-choice selection of a grade level1 |

| 2 | In your opinion, is the presented digital material suitable for learners with special educational needs? If so, select one or none. | single-choice selection of (no) special need2 | |

| 3 | Describe the learning content for which you think the presented digital material is intended. | open-text item | |

| 4 | TCK-x, TPK-x, and/or TPACK reasoning |

For the specified grade level, special educational needs, and your description of the learning content of the presented dLM, justify why or why not you would use the presented digital material. |

open-text item |

| Study | RQs | Size of initial sample |

Size of adjusted Sample1 |

Adjusted sample size per university of country: Austria / Germany | dLM used in study |

Mean processing time of task in minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RQ1 | 164 | 164 | 61 / 103 | dLM1-4 | 9.842 |

| 2 | RQ2.x | 395 | 379 | 55 / 324 | dLM1 | 4.293 |

| Type of assessment |

Sem. 1, 2 (n = 57) |

Sem. 3, 4 (n = 149) |

Sem. 5, 6 (n = 71) |

Sem. ≥ 7 (n = 102) |

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| external1 | 1.37a | 1.43 | 2.12b | 1.60 | 2.27b | 1.55 | 2.65b | 1.51 | F(3,375) 8.51 |

ηp 2 .06 |

| self-report2 | 3.12c | .86 | 3.27c | .73 | 3.44 | .72 | 3.55d | .76 | Chi2 (3) 11.99 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).