Submitted:

22 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Fermented Plant-Based Foods

2.1. Soymilk and Soybeen Products

2.2. Cassava

2.3. Olive

3. Fermented Beverages

3.1. Alcoholic Beverages

3.1.1. Wine

3.1.2. Beer

3.2. Non-Alcoholic Fermented Fruit Products

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sengupta, S.; Datta, M.; Datta, S. β-Glucosidase: Structure, Function and Industrial Applications. In Glycoside Hydrolases; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 97–120.

- Henrissat, B. A Classification of Glycosyl Hydrolases Based on Amino Acid Sequence Similarities; 1991; Vol. 280.

- Henrissat, B.; Davies, G. Structural and Sequence-Based Classification of Glycoside Hydrolases. Curr Opin Struct Biol 1997, 7, 637–644. [CrossRef]

- Ketudat Cairns, J.R.; Esen, A. β-Glucosidases. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2010, 67, 3389–3405. [CrossRef]

- Cantarel, B.L.; Coutinho, P.M.; Rancurel, C.; Bernard, T.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes Database (CAZy): An Expert Resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, D233–D238. [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P.; Shafreen M, M.; Achudhan, A.B.; Gupta, A.; Saleena, L.M. A Review on Applications of β-Glucosidase in Food, Brewery, Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Industries. Carbohydr Res 2023, 530, 108855. [CrossRef]

- Magwaza, B.; Amobonye, A.; Pillai, S. Microbial β-Glucosidases: Recent Advances and Applications. Biochimie 2024, 225, 49–67. [CrossRef]

- Mól, P.C.G.; Júnior, J.C.Q.; Veríssimo, L.A.A.; Boscolo, M.; Gomes, E.; Minim, L.A.; Da Silva, R. β-Glucosidase: An Overview on Immobilization and Some Aspects of Structure, Function, Applications and Cost. Process Biochemistry 2023, 130, 26–39. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Verma, A.K.; Kumar, V. Catalytic Properties, Functional Attributes and Industrial Applications of β-Glucosidases. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 3. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; He, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Wei, L.; Chen, Y.; Du, M.; Liu, D.; Li, C.; et al. A Dual-subcellular Localized Β-glucosidase Confers Pathogen and Insect Resistance without a Yield Penalty in Maize. Plant Biotechnol J 2024, 22, 1017–1032. [CrossRef]

- Kotik, M.; Kulik, N.; Valentová, K. Flavonoids as Aglycones in Retaining Glycosidase-Catalyzed Reactions: Prospects for Green Chemistry. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 14890–14910. [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wu, T.; Ali, A.; Wang, J.; Fang, Y.; Qiang, R.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; et al. Rice β-Glucosidase 4 (Os1βGlu4) Regulates the Hull Pigmentation via Accumulation of Salicylic Acid. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 10646. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Piao, H.L.; Kim, H.-Y.; Choi, S.M.; Jiang, F.; Hartung, W.; Hwang, I.; Kwak, J.M.; Lee, I.-J.; Hwang, I. Activation of Glucosidase via Stress-Induced Polymerization Rapidly Increases Active Pools of Abscisic Acid. Cell 2006, 126, 1109–1120. [CrossRef]

- Sakr, S.; Wang, M.; Dédaldéchamp, F.; Perez-Garcia, M.-D.; Ogé, L.; Hamama, L.; Atanassova, R. The Sugar-Signaling Hub: Overview of Regulators and Interaction with the Hormonal and Metabolic Network. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 2506. [CrossRef]

- Boer, D.E.C.; van Smeden, J.; Bouwstra, J.A.; Aerts, J.M.F.G. Glucocerebrosidase: Functions in and Beyond the Lysosome. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 736. [CrossRef]

- Day, A.J.; Cañada, F.J.; Díaz, J.C.; Kroon, P.A.; Mclauchlan, R.; Faulds, C.B.; Plumb, G.W.; Morgan, M.R.A.; Williamson, G. Dietary Flavonoid and Isoflavone Glycosides Are Hydrolysed by the Lactase Site of Lactase Phlorizin Hydrolase. FEBS Lett 2000, 468, 166–170. [CrossRef]

- Elferink, H.; Bruekers, J.P.J.; Veeneman, G.H.; Boltje, T.J. A Comprehensive Overview of Substrate Specificity of Glycoside Hydrolases and Transporters in the Small Intestine. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2020, 77, 4799–4826. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Jiang, B.; Chakraborty, A.; Yu, G. The Evolution of Glycoside Hydrolase Family 1 in Insects Related to Their Adaptation to Plant Utilization. Insects 2022, 13, 786. [CrossRef]

- Friedrichs, J.; Schweiger, R.; Müller, C. Unique Metabolism of Different Glucosinolates in Larvae and Adults of a Leaf Beetle Specialised on Brassicaceae. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 10905. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Nasim, F.; Batool, K.; Bibi, A. Microbial β -Glucosidase: Sources, Production and Applications. J Appl Environ Microbiol 2017, 5, 31–46. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, Y.; Mishra, S.; Bisaria, V.S. Microbial β-Glucosidases: Cloning, Properties, and Applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2002, 22, 375–407. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yin, Z.; Wu, L.; Yin, C. Diversity of Cultivable β-Glycosidase-Producing Micro-Organisms Isolated from the Soil of a Ginseng Field and Their Ginsenosides-Hydrolysing Activity. Lett Appl Microbiol 2014, 58, 138–144. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Kumar, K.; Singh, S.; Nain, L.; Shukla, P. Molecular Detection and Environment-Specific Diversity of Glycosyl Hydrolase Family 1 β-Glucosidase in Different Habitats. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Xiao, Z.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, C.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Huang, W.; Huang, X.; et al. High Diversity of β-Glucosidase-Producing Bacteria and Their Genes Associated with Scleractinian Corals. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 3523. [CrossRef]

- Oladoja, E.; Oyewole, O.; Adamu, B.; Balogun, A.; Musa, O. Microbial β-Glucosidase: Source, Production and Applications. International Journal of Biology Sciences 2019, 1, 14–22. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhang, N.; Zuo, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, X. Recent Advances in β-Glucosidase Sequence and Structure Engineering: A Brief Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 4990. [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.; Liu, M.; Fan, Y.; Xu, J.; Xu, X.; Li, H. The Structural and Functional Contributions of β-Glucosidase-Producing Microbial Communities to Cellulose Degradation in Composting. Biotechnol Biofuels 2018, 11, 51. [CrossRef]

- Michlmayr, H.; Kneifel, W. β-Glucosidase Activities of Lactic Acid Bacteria: Mechanisms, Impact on Fermented Food and Human Health. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2014, 352, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Colautti, A.; Camprini, L.; Ginaldi, F.; Comi, G.; Reale, A.; Coppola, F.; Iacumin, L. Safety Traits, Genetic and Technological Characterization of Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus Strains. LWT 2024, 207, 116578. [CrossRef]

- Coppola, F.; Abdalrazeq, M.; Fratianni, F.; Ombra, M.N.; Testa, B.; Zengin, G.; Ayala Zavala, J.F.; Nazzaro, F. Rosaceae Honey: Antimicrobial Activity and Prebiotic Properties. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 298. [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, F.; Ombra, M.N.; Coppola, F.; De Giulio, B.; d’Acierno, A.; Coppola, R.; Fratianni, F. Antibacterial Activity and Prebiotic Properties of Six Types of Lamiaceae Honey. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 868. [CrossRef]

- Letizia, F.; Fusco, G.M.; Fratianni, A.; Gaeta, I.; Carillo, P.; Messia, M.C.; Iorizzo, M. Application of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum LP95 as a Functional Starter Culture in Fermented Tofu Production. Processes 2024, 12, 1093. [CrossRef]

- Berthiller, F.; Krska, R.; Domig, K.J.; Kneifel, W.; Juge, N.; Schuhmacher, R.; Adam, G. Hydrolytic Fate of Deoxynivalenol-3-Glucoside during Digestion. Toxicol Lett 2011, 206, 264–267. [CrossRef]

- Siezen, R.J.; Tzeneva, V.A.; Castioni, A.; Wels, M.; Phan, H.T.K.; Rademaker, J.L.W.; Starrenburg, M.J.C.; Kleerebezem, M.; Molenaar, D.; Van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Phenotypic and Genomic Diversity of Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains Isolated from Various Environmental Niches. Environ Microbiol 2010, 12, 758–773. [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.E.; Bayjanov, J.R.; Caffrey, B.E.; Wels, M.; Joncour, P.; Hughes, S.; Gillet, B.; Kleerebezem, M.; van Hijum, S.A.F.T.; Leulier, F. Nomadic Lifestyle of Lactobacillus Plantarum Revealed by Comparative Genomics of 54 Strains Isolated from Different Habitats. Environ Microbiol 2016, 18, 4974–4989. [CrossRef]

- Siezen, R.J.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T. Genomic Diversity and Versatility of Lactobacillus Plantarum, a Natural Metabolic Engineer. Microb Cell Fact 2011, 10. [CrossRef]

- Letizia, F.; Albanese, G.; Testa, B.; Vergalito, F.; Bagnoli, D.; Di Martino, C.; Carillo, P.; Verrillo, L.; Succi, M.; Sorrentino, E.; et al. In Vitro Assessment of Bio-Functional Properties from Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum Strains. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2022, 44, 2321–2334. [CrossRef]

- Filannino, P.; De Angelis, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Gozzi, G.; Riciputi, Y.; Gobbetti, M. How Lactobacillus Plantarum Shapes Its Transcriptome in Response to Contrasting Habitats. Environ Microbiol 2018, 20, 3700–3716. [CrossRef]

- Testa, B.; Lombardi, S.J.; Tremonte, P.; Succi, M.; Tipaldi, L.; Pannella, G.; Sorrentino, E.; Iorizzo, M.; Coppola, R. Biodiversity of Lactobacillus Plantarum from Traditional Italian Wines. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 30, 2299–2305. [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Lombardi, S.J.; Macciola, V.; Testa, B.; Lustrato, G.; Lopez, F.; De Leonardis, A. Technological Potential of Lactobacillus Strains Isolated from Fermented Green Olives: In Vitro Studies with Emphasis on Oleuropein-Degrading Capability. Scientific World Journal 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Testa, B.; Ganassi, S.; Lombardi, S.J.; Ianiro, M.; Letizia, F.; Succi, M.; Tremonte, P.; Vergalito, F.; Cozzolino, A.; et al. Probiotic Properties and Potentiality of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum Strains for the Biological Control of Chalkbrood Disease. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Chundakkattumalayil, H.C.; Raghavan, K.T. Health Endorsing Potential of Lactobacillus Plantarum MBTU-HK1 and MBTU-HT of Honey Bee Gut Origin. J Appl Biol Biotechnol 2021, 9, 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Pannella, G.; Lombardi, S.J.; Ganassi, S.; Testa, B.; Succi, M.; Sorrentino, E.; Petrarca, S.; De Cristofaro, A.; Coppola, R.; et al. Inter-and Intra-Species Diversity of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Apis Mellifera Ligustica Colonies. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Albanese, G.; Testa, B.; Ianiro, M.; Letizia, F.; Succi, M.; Tremonte, P.; D’andrea, M.; Iaffaldano, N.; Coppola, R. Presence of Lactic Acid Bacteria in the Intestinal Tract of the Mediterranean Trout (Salmo Macrostigma) in Its Natural Environment. Life 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Lim, S.-D. Probiotic Characteristics of Lactobacillus Plantarum FH185 Isolated from Human Feces. Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour 2015, 35, 615–621. [CrossRef]

- Salvetti, E.; O’Toole, P.W. When Regulation Challenges Innovation: The Case of the Genus Lactobacillus. Trends Food Sci Technol 2017, 66, 187–194. [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Hilbert, F.; Lindqvist, R.; et al. Update of the List of QPS-recommended Biological Agents Intentionally Added to Food or Feed as Notified to EFSA 12: Suitability of Taxonomic Units Notified to EFSA until March 2020. EFSA Journal 2020, 18. [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Paventi, G.; Di Martino, C. Biosynthesis of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) by Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum in Fermented Food Production. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2023, 46, 200–220. [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Di Martino, C.; Letizia, F.; Crawford, T.W.; Paventi, G. Production of Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA) by Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum: A Review with Emphasis on Fermented Foods. Foods 2024, 13, 975. [CrossRef]

- Paventi, G.; Di Martino, C.; Crawford Jr, T.W.; Iorizzo, M. Enzymatic Activities of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum: Technological and Functional Role in Food Processing and Human Nutrition. Food Biosci 2024, 61, 104944. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.S.; Ray, R.C.; Zdolec, N. Lactobacillus Plantarum with Functional Properties: An Approach to Increase Safety and Shelf-Life of Fermented Foods. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018.

- Caffrey, A.J.; Lerno, L.A.; Zweigenbaum, J.; Ebeler, S.E. Direct Analysis of Glycosidic Aroma Precursors Containing Multiple Aglycone Classes in Vitis Vinifera Berries. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68, 3817–3833. [CrossRef]

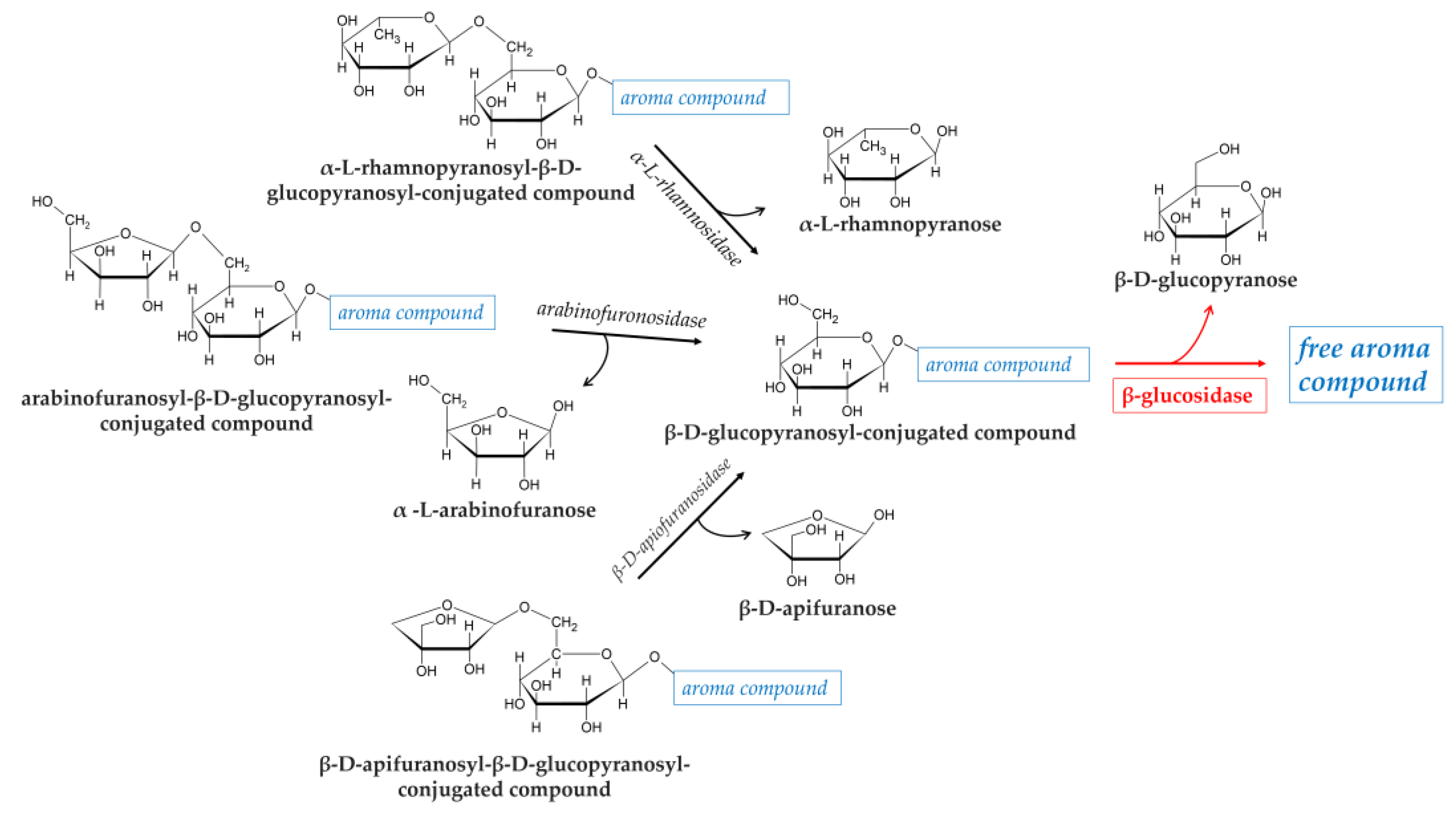

- Liang, Z.; Fang, Z.; Pai, A.; Luo, J.; Gan, R.; Gao, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, P. Glycosidically Bound Aroma Precursors in Fruits: A Comprehensive Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 215–243. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Wang, T.; Ge, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bao, H. γ -Amino Butyric Acid (GABA) Synthesis Enabled by Copper-Catalyzed Carboamination of Alkenes. Org Lett 2017, 19, 4718–4721. [CrossRef]

- González-Barreiro, C.; Rial-Otero, R.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Wine Aroma Compounds in Grapes: A Critical Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2015, 55, 202–218. [CrossRef]

- Maicas, S.; Mateo, J.J. Hydrolysis of Terpenyl Glycosides in Grape Juice and Other Fruit Juices: A Review. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2005, 67, 322–335. [CrossRef]

- Krammer, G.; Winterhalter, P.; Schwab, M.; Schreier, P. Glycosidically Bound Aroma Compounds in the Fruits of Prunus Species: Apricot (p. Armeniaca, l.), Peach (p. Persica, l.), Yellow Plum (p. Domestica, l. Ssp. Syriaca). J Agric Food Chem 1991, 39, 778–781. [CrossRef]

- de Morais Souto, B.; Florentino Barbosa, M.; Marinsek Sales, R.M.; Conessa Moura, S.; de Rezende Bastos Araújo, A.; Ferraz Quirino, B. The Potential of β-Glucosidases for Aroma and Flavor Improvement in the Food Industry. The Microbe 2023, 1, 100004. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pacheco, P.; García-Béjar, B.; Briones Pérez, A.; Arévalo-Villena, M. Free and Immobilised β-Glucosidases in Oenology: Biotechnological Characterisation and Its Effect on Enhancement of Wine Aroma. Front Microbiol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Sarry, J.; Gunata, Z. Plant and Microbial Glycoside Hydrolases: Volatile Release from Glycosidic Aroma Precursors. Food Chem 2004, 87, 509–521. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, K.; Liu, C.; Ma, L.; Li, J. Effects of Glycosidase on Glycoside-Bound Aroma Compounds in Grape and Cherry Juice. J Food Sci Technol 2023, 60, 761–771. [CrossRef]

- Dziadas, M.; Jeleń, H.H. Comparison of Enzymatic and Acid Hydrolysis of Bound Flavor Compounds in Model System and Grapes. Food Chem 2016, 190, 412–418. [CrossRef]

- Muradova, M.; Proskura, A.; Canon, F.; Aleksandrova, I.; Schwartz, M.; Heydel, J.-M.; Baranenko, D.; Nadtochii, L.; Neiers, F. Unlocking Flavor Potential Using Microbial β-Glucosidases in Food Processing. Foods 2023, 12, 4484. [CrossRef]

- Maicas, S.; Mateo, J. Microbial Glycosidases for Wine Production. Beverages 2016, 2, 20. [CrossRef]

- Hjelmeland, A.K.; Ebeler, S.E. Glycosidically Bound Volatile Aroma Compounds in Grapes and Wine: A Review. Am J Enol Vitic 2015, 66, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wilkowska, A.; Pogorzelski, E. Aroma Enhancement of Cherry Juice and Wine Using Exogenous Glycosidases from Mould, Yeast and Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food Chem 2017, 237, 282–289. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Sang, S.; McClements, D.J.; Chen, L.; Long, J.; Jiao, A.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, C. Polyphenols as Plant-Based Nutraceuticals: Health Effects, Encapsulation, Nano-Delivery, and Application. Foods 2022, 11, 2189. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xue, Y.; Lin, Y. Enhanced Catalytic Efficiency in Quercetin-4′-Glucoside Hydrolysis of Thermotoga Maritima β-Glucosidase A by Site-Directed Mutagenesis. J Agric Food Chem 2014, 62, 6763–6770. [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary (Poly)Phenolics in Human Health: Structures, Bioavailability, and Evidence of Protective Effects against Chronic Diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hong, J.; Wang, L.; Cai, C.; Mo, H.; Wang, J.; Fang, X.; Liao, Z. Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation on Plant-Based Products. Fermentation 2024, 10, 48. [CrossRef]

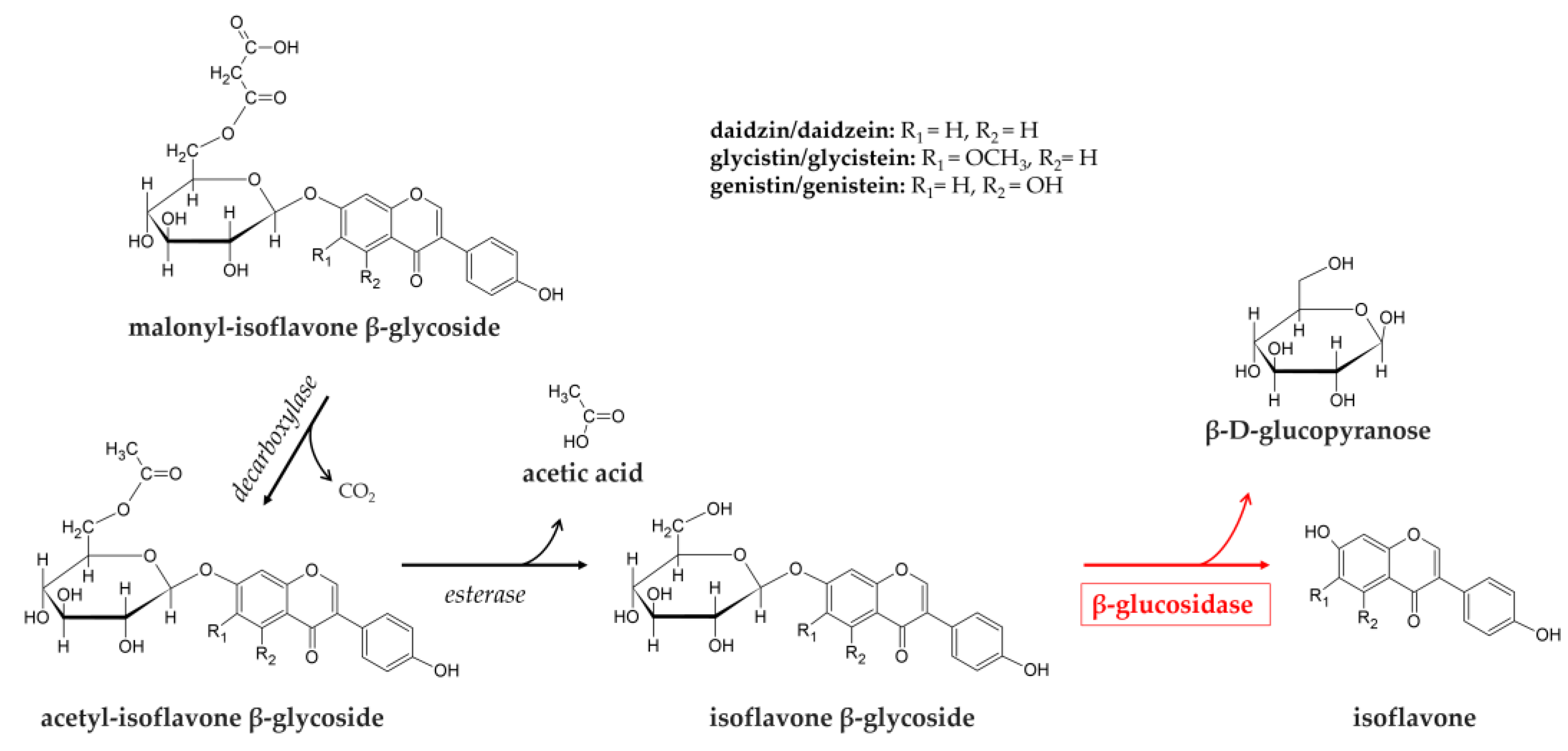

- Bustamante-Rangel, M.; Delgado-Zamarreño, M.M.; Pérez-Martín, L.; Rodríguez-Gonzalo, E.; Domínguez-Álvarez, J. Analysis of Isoflavones in Foods. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2018, 17, 391–411. [CrossRef]

- Atlante, A.; Bobba, A.; Paventi, G.; Pizzuto, R.; Passarella, S. Genistein and Daidzein Prevent Low Potassium-Dependent Apoptosis of Cerebellar Granule Cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2010, 79, 758–767.

- Sharma, D.; Singh, V.; Kumar, A.; Singh, T.G. Genistein: A Promising Ally in Combating Neurodegenerative Disorders. Eur J Pharmacol 2025, 991. [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, K.; Humayoun Akhtar, M. An Updated Review of Dietary Isoflavones: Nutrition, Processing, Bioavailability and Impacts on Human Health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017, 57, 1280–1293. [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, M.; Xu, B. An Insight into the Health Benefits of Fermented Soy Products. Food Chem 2019, 271, 362–371. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wong, W.T.; Wu, R.; Lai, W.F. Biochemistry and Use of Soybean Isoflavones in Functional Food Development. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2020, 60, 2098–2112. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.S.; Rha, C.-S.; Baik, M.-Y.; Baek, N.-I.; Kim, D.-O. A Brief History and Spectroscopic Analysis of Soy Isoflavones. Food Sci Biotechnol 2020, 29, 1605–1617. [CrossRef]

- Izumi, T.; Osawa, S.; Obata, A.; Tobe, K.; Saito, M.; Kataoka, S.; Kikuchi, M.; Piskula, M.K.; Kubota, Y. Soy Isoflavone Aglycones Are Absorbed Faster and in Higher Amounts than Their Glucosides in Humans. J Nutr 2000, 130, 1695–1699. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Xu, J.; Xu, X.; Liu, J. Bioaccessibility and Application of Soybean Isoflavones: A Review. Food Reviews International 2022, 39, 5948–5967. [CrossRef]

- Setchell, K.D.; Brown, N.M.; Zimmer-Nechemias, L.; Brashear, W.T.; Wolfe, B.E.; Kirschner, A.S.; Heubi, J.E. Evidence for Lack of Absorption of Soy Isoflavone Glycosides in Humans, Supporting the Crucial Role of Intestinal Metabolism for Bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr 2002, 76, 447–453. [CrossRef]

- Chien, H.-L.; Huang, H.-Y.; Chou, C.-C. Transformation of Isoflavone Phytoestrogens during the Fermentation of Soymilk with Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bifidobacteria. Food Microbiol 2006, 23, 772–778. [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Kim, G.M.; Lee, K.W.; Choi, I.D.; Kwon, G.; Park, J.; Jeong, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.H. Conversion of Isoflavone Glucosides to Aglycones in Soymilk by Fermentation with Lactic Acid Bacteria. J Food Sci 2007, 72. [CrossRef]

- Pyo, Y.-H.; Lee, T.-C.; Lee, Y.-C. Enrichment of Bioactive Isoflavones in Soymilk Fermented with β-Glucosidase-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food Research International 2005, 38, 551–559. [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J.; Lim, B.; Kim, H.Y.; Kwon, S.-J.; Eom, S.H. Deglycosylation Patterns of Isoflavones in Soybean Extracts Inoculated with Two Enzymatically Different Strains of Lactobacillus Species. Enzyme Microb Technol 2020, 132, 109394. [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.L.; Shah, N.P.; Wilcox, G.; Walker, K.Z.; Stojanovska, L. Fermentation of Calcium-Fortified Soymilk with Lactobacillus: Effects on Calcium Solubility, Isoflavone Conversion, and Production of Organic Acids. J Food Sci 2007, 72. [CrossRef]

- Letizia, F.; Fratianni, A.; Cofelice, M.; Testa, B.; Albanese, G.; Di Martino, C.; Panfili, G.; Lopez, F.; Iorizzo, M. Antioxidative Properties of Fermented Soymilk Using Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum LP95. Antioxidants 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Ro, K.-S.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.-J.; Li, W.; Xie, J.; Wei, D. Effects of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum X7021 on Physicochemical Properties, Purines, Isoflavones and Volatile Compounds of Fermented Soymilk. Process Biochemistry 2022, 113, 150–157. [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, D.; Soetjipto, S.; Catur Adi, A. Characteristic and Isoflavone Level of Soymilk Fermented by Single and Mixed Culture of Lactobacillus Plantarum and Yoghurt Starter. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2021, 9, 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, J.K.; Barañano, L.; Castañón, S.; Alkorta, I.; Quirós, L.M.; Garbisu, C. Optimization of the Bioactivation of Isoflavones in Soymilk by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Processes 2021, 9, 963. [CrossRef]

- Bock, H.-J.; Lee, H.-W.; Lee, N.-K.; Paik, H.-D. Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum KU210152 and Its Fermented Soy Milk Attenuates Oxidative Stress in Neuroblastoma Cells. Food Research International 2024, 177, 113868. [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.-H.; Bock, H.-J.; Lee, N.-K.; Paik, H.-D. Soy Yogurt Using Lactobacillus Plantarum 200655 and Fructooligosaccharides: Neuroprotective Effects against Oxidative Stress. J Food Sci Technol 2022, 59, 4870–4879. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Hou, K.; Mu, G.; Ma, C.; Tuo, Y. Antioxidative Effect of Soybean Milk Fermented by Lactobacillus Plantarum Y16 on 2, 2 –Azobis (2-Methylpropionamidine) Dihydrochloride (ABAP)-Damaged HepG2 Cells. Food Biosci 2021, 44. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.T.; Yang, C.Y.; Fang, T.J. Enhanced β-Glucosidase Activity of Lactobacillus Plantarum by a Strategic Ultrasound Treatment for Biotransformation of Isoflavones in Okara. Food Sci Technol Res 2018, 24, 777–784. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Thakur, K.; Feng, J.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, F.; Russo, P.; Spano, G.; Zhang, J.-G.; Wei, Z.-J. Functionalization of Soy Residue (Okara) by Enzymatic Hydrolysis and LAB Fermentation for B<inf>2</Inf> Bio-Enrichment and Improved in Vitro Digestion. Food Chem 2022, 387. [CrossRef]

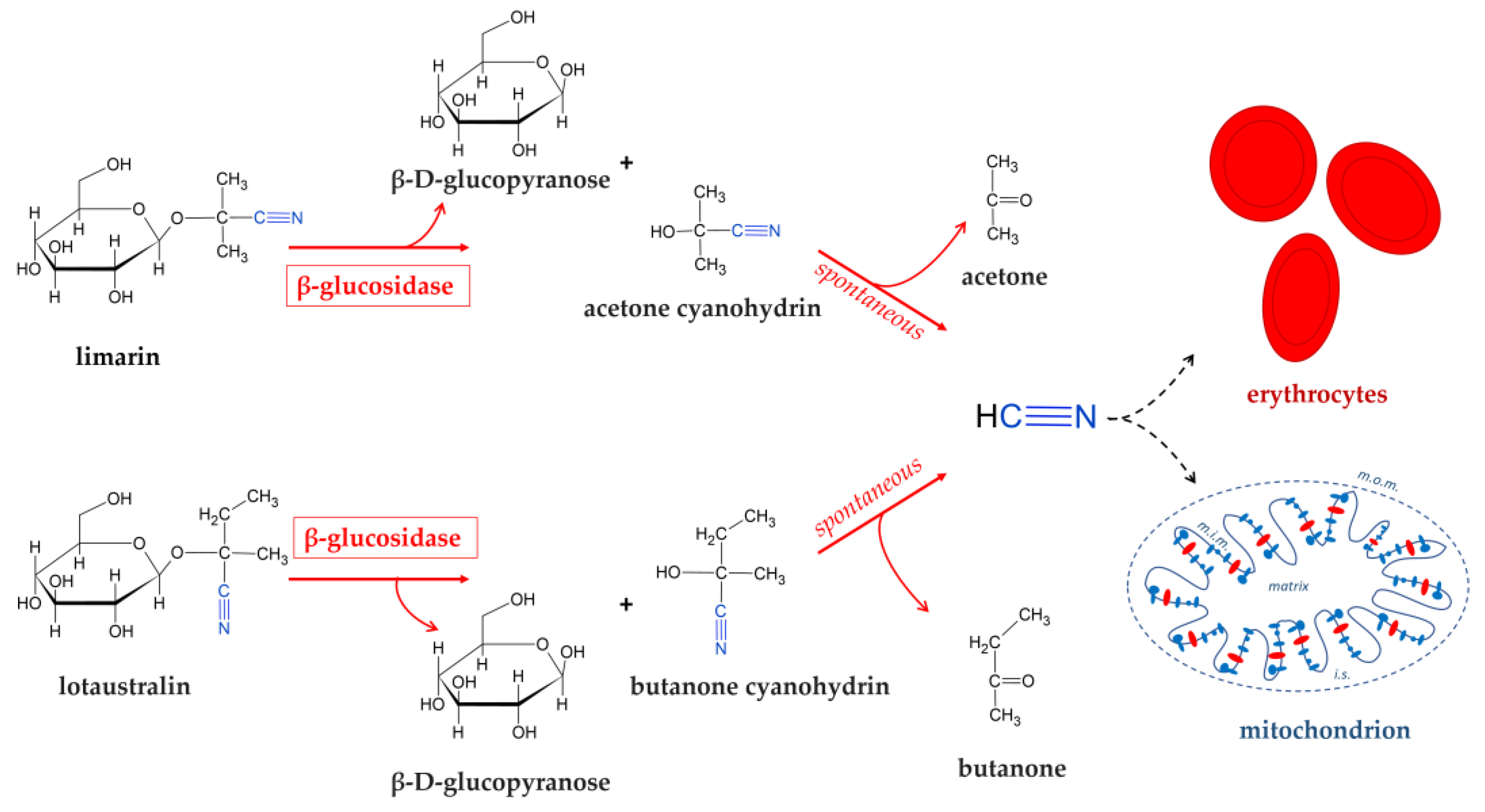

- Parmar, A.; Sturm, B.; Hensel, O. Crops That Feed the World: Production and Improvement of Cassava for Food, Feed, and Industrial Uses. Food Secur 2017, 9, 907–927. [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.I.; Kongsil, P.; Nguyễn, V.A.; Ou, W.; Sholihin; Srean, P.; Sheela, M.; Becerra López-Lavalle, L.A.; Utsumi, Y.; Lu, C.; et al. Cassava Breeding and Agronomy in Asia: 50 Years of History and Future Directions. Breed Sci 2020, 70, 145–166. [CrossRef]

- Halake, N.H.; Chinthapalli, B. Fermentation of Traditional African Cassava Based Foods: Microorganisms Role in Nutritional and Safety Value. Journal of Experimental Agriculture International 2020, 56–65. [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, I.; Miranda, R.; Borelli, B.; Nunes, A.; Nardi, R.; Lachance, M.; Rosa, C. Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeasts Associated with Spontaneous Fermentations during the Production of Sour Cassava Starch in Brazil. Int J Food Microbiol 2005, 105, 213–219. [CrossRef]

- Howeler, R.; Lutaladio, N.; Thomas, G. Save and Grow: Cassava: A Guide to Sustainable Production Intensification; 2013.

- Latif, S.; Müller, J. Potential of Cassava Leaves in Human Nutrition: A Review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2015, 44, 147–158. [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, W.G. Cassava Production in Africa: A Panel Analysis of the Drivers and Trends. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19939. [CrossRef]

- Kashala-Abotnes, E.; Okitundu, D.; Mumba, D.; Boivin, M.J.; Tylleskär, T.; Tshala-Katumbay, D. Konzo: A Distinct Neurological Disease Associated with Food (Cassava) Cyanogenic Poisoning. Brain Res Bull 2019, 145, 87–91. [CrossRef]

- Adamolekun, B. Neurological Disorders Associated with Cassava Diet: A Review of Putative Etiological Mechanisms. Metab Brain Dis 2011, 26, 79–85. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, A.R.; Nicoletti, M.A.; Rodrigues, A.J.; Pressutti, C.; Almeida, J.; Brandão, T.; Kinue Ito, R.; Bafille Leoni, L.A.; Souza Spinosa, H. De Cassava Flour: Quantification of Cyanide Content. Food Nutr Sci 2016, 07, 592–599. [CrossRef]

- Cressey, P.; Reeve, J. Metabolism of Cyanogenic Glycosides: A Review. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2019, 125, 225–232. [CrossRef]

- Renchinkhand, G.; Park, Y.W.; Cho, S.-H.; Song, G.-Y.; Bae, H.C.; Choi, S.-J.; Nam, M.S. Identification of β-Glucosidase Activity of L Actobacillus Plantarum CRNB22 in Kimchi and Its Potential to Convert Ginsenoside Rb 1 from P Anax Ginseng. J Food Biochem 2015, 39, 155–163. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Selected Airborne Chemicals; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2002; ISBN 978-0-309-08511-3.

- Oloya, B.; Adaku, C.; Andama, M. The Cyanogenic Potential of Certain Cassava Varieties in Uganda and Their Fermentation-Based Detoxification. In Cassava - Recent Updates on Food, Feed, and Industry; IntechOpen, 2024.

- Brimer, L. Cassava Production and Processing and Impact on Biological Compounds; 2015; ISBN 9780124047099.

- Bouatenin, K.M.J.-P.; Theodore, D.N.; Alfred, K.K.; Hermann, C.W.; Marcellin, D.K. Excretion of β-Glucosidase and Pectinase by Microorganisms Isolated from Cassava Traditional Ferments Used for Attieke Production in Côte d’Ivoire. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2019, 20, 101217. [CrossRef]

- Panghal, A.; Munezero, C.; Sharma, P.; Chhikara, N. Cassava Toxicity, Detoxification and Its Food Applications: A Review. Toxin Rev 2021, 40, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Penido, F.C.L.; Piló, F.B.; Sandes, S.H. de C.; Nunes, Á.C.; Colen, G.; Oliveira, E. de S.; Rosa, C.A.; Lacerda, I.C.A. Selection of Starter Cultures for the Production of Sour Cassava Starch in a Pilot-Scale Fermentation Process. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2018, 49, 823–831. [CrossRef]

- Omar, N. Ben; Ampe, F.; Raimbault, M.; Guyot, J.-P.; Tailliez, P. Molecular Diversity of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Cassava Sour Starch (Colombia). Syst Appl Microbiol 2000, 23, 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Bamigbade, G.B.; Sanusi, J.F.O.; Oyelami, O.I.; Daniel, O.M.; Alimi, B.O.; Ampofo, K.A.; Liu, S.-Q.; Shah, N.P.; Ayyash, M. Identification and Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Effluents Generated During Cassava Fermentation as Potential Candidates for Probiotics. Food Biotechnol 2023, 37, 413–433. [CrossRef]

- Oyedeji, O.; Ogunbanwo, S.T.; Onilude, A.A. Predominant Lactic Acid Bacteria Involved in the Traditional Fermentation of Fufu and Ogi, Two Nigerian Fermented Food Products. Food Nutr Sci 2013, 04, 40–46. [CrossRef]

- Putri, W.D.R.; Haryadi; Marseno, D.W.; Cahyanto, M.N. Role of Lactic Acid Bacteria on Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Sour Cassava Starch. APCBEE Procedia 2012, 2, 104–109. [CrossRef]

- Crispim, S.M.; Nascimento, A.M.A.; Costa, P.S.; Moreira, J.L.S.; Nunes, A.C.; Nicoli, J.R.; Lima, F.L.; Mota, V.T.; Nardi, R.M.D. Molecular Identification of Lactobacillus Spp. Associated with Puba, a Brazilian Fermented Cassava Food. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2013, 44, 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Wilfrid Padonou, S.; Nielsen, D.S.; Hounhouigan, J.D.; Thorsen, L.; Nago, M.C.; Jakobsen, M. The Microbiota of Lafun, an African Traditional Cassava Food Product. Int J Food Microbiol 2009, 133, 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.; Davila, A.M.; Pourquié, J. Lactic Acid Bacteria of the Sour Cassava Starch Fermentation. Lett Appl Microbiol 1995, 21, 126–130. [CrossRef]

- Kostinek, M.; Specht, I.; Edward, V.A.; Pinto, C.; Egounlety, M.; Sossa, C.; Mbugua, S.; Dortu, C.; Thonart, P.; Taljaard, L.; et al. Characterisation and Biochemical Properties of Predominant Lactic Acid Bacteria from Fermenting Cassava for Selection as Starter Cultures. Int J Food Microbiol 2007, 114, 342–351. [CrossRef]

- Lei, V.; Amoa-Awua, W.K.A.; Brimer, L. Degradation of Cyanogenic Glycosides by Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains from Spontaneous Cassava Fermentation and Other Microorganisms. Int J Food Microbiol 1999, 53, 169–184. [CrossRef]

- Wakil, S.M.; Benjamin, I.B. Starter Developed Pupuru, a Traditional Africa Fermented Food from Cassava (Manihot Esculenta). Int Food Res J 2015, 22, 2565–2570.

- Gunawan, S.; Widjaja, T.; Zullaikah, S.; Ernawati, L.; Istianah, N.; Aparamarta, H.W.; Prasetyoko, D. Effect of Fermenting Cassava with Lactobacillus Plantarum, Saccharomyces Cereviseae, and Rhizopus Oryzae on the Chemical Composition of Their Flour. Int Food Res J 2015, 22, 1280–1287.

- Kostinek, M.; Specht, I.; Edward, V.A.; Schillinger, U.; Hertel, C.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Franz, C.M.A.P. Diversity and Technological Properties of Predominant Lactic Acid Bacteria from Fermented Cassava Used for the Preparation of Gari, a Traditional African Food. Syst Appl Microbiol 2005, 28, 527–540. [CrossRef]

- Tefera, T.; Ameha, K.; Biruhtesfa, A. Cassava Based Foods: Microbial Fermentation by Single Starter Culture towards Cyanide Reduction, Protein Enhancement and Palatability. Int Food Res J 2014, 21, 1751–1756.

- Kimaryo, V.M.; Massawe, G.A.; Olasupo, N.A.; Holzapfel, W.H. The Use of a Starter Culture in the Fermentation of Cassava for the Production of “Kivunde”, a Traditional Tanzanian Food Product. Int J Food Microbiol 2000, 56, 179–190. [CrossRef]

- Damayanti, E.; Kurniadi, M.; Helmi, R.L.; Frediansyah, A. Single Starter Lactobacillus Plantarum for Modified Cassava Flour (Mocaf) Fermentation. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; 2020; Vol. 462.

- Charoenprasert, S.; Mitchell, A. Factors Influencing Phenolic Compounds in Table Olives (Olea Europaea). J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 7081–7095. [CrossRef]

- Guggenheim, K.G.; Crawford, L.M.; Paradisi, F.; Wang, S.C.; Siegel, J.B. β-Glucosidase Discovery and Design for the Degradation of Oleuropein. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 15754–15762. [CrossRef]

- Rokni, Y.; Abouloifa, H.; Bellaouchi, R.; Gaamouche, S.; Mchiouer, K.; Hasnaoui, I.; Lamzira, Z.; Ghabbour, N.; Asehraou, A. Technological Process of Fermented Olive. Arabian Journal of Chemical and Environmental Research 2017, 07, 63–91.

- Habibi, M.; Golmakani, M.-T.; Farahnaky, A.; Mesbahi, G.; Majzoobi, M. NaOH-Free Debittering of Table Olives Using Power Ultrasound. Food Chem 2016, 192, 775–781. [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, A.; Perpetuini, G.; Schirone, M.; Tofalo, R.; Suzzi, G. Application of Starter Cultures to Table Olive Fermentation: An Overview on the Experimental Studies. Front Microbiol 2012, 3. [CrossRef]

- Pino, A.; Vaccalluzzo, A.; Solieri, L.; Romeo, F. V.; Todaro, A.; Caggia, C.; Arroyo-López, F.N.; Bautista-Gallego, J.; Randazzo, C.L. Effect of Sequential Inoculum of Beta-Glucosidase Positive and Probiotic Strains on Brine Fermentation to Obtain Low Salt Sicilian Table Olives. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ciafardini, G.; Marsilio, V.; Lanza, B.; Pozzi, N. Hydrolysis of Oleuropein by Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains Associated with Olive Fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994, 60, 4142–4147. [CrossRef]

- Rokni, Y.; Abouloifa, H.; Bellaouchi, R.; Hasnaoui, I.; Gaamouche, S.; Lamzira, Z.; Salah, R.B.E.N.; Saalaoui, E.; Ghabbour, N.; Asehraou, A. Characterization of β-Glucosidase of Lactobacillus Plantarum FSO1 and Candida Pelliculosa L18 Isolated from Traditional Fermented Green Olive. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology 2021, 19, 117. [CrossRef]

- De Leonardis, A.; Testa, B.; Macciola, V.; Lombardi, S.J.; Iorizzo, M. Exploring Enzyme and Microbial Technology for the Preparation of Green Table Olives. European Food Research and Technology 2016, 242, 363–370. [CrossRef]

- Ghabbour, N.; Rokni, Y.; Abouloifa, H.; Bellaouchi, R.; Chihib, N.-E.; Ben Salah, R.; Lamzira, Z.; Saalaoui, E.; Asehraou, A. In Vitro Biodegradation of Oleuropein by Lactobacillus Plantarum FSO175 in Stress Conditions (PH, NaCl and Glucose). Journal of microbiology, biotechnology and food sciences 2020, 9, 769–773. [CrossRef]

- Ghabbour, N.; Rokni, Y.; Lamzira, Z.; Thonart, P.; Chihib, N.E.; Peres, C.; Asehraou, A. Controlled Fermentation of Moroccan Picholine Green Olives by Oleuropein-Degrading Lactobacilli Strains. Grasas y Aceites 2016, 67, e138. [CrossRef]

- Vaccalluzzo, A.; Pino, A.; De Angelis, M.; Bautista-Gallego, J.; Romeo, F.V.; Foti, P.; Caggia, C.; Randazzo, C.L. Effects of Different Stress Parameters on Growth and on Oleuropein-Degrading Abilities of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum Strains Selected as Tailored Starter Cultures for Naturally Table Olives. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1607. [CrossRef]

- Zago, M.; Lanza, B.; Rossetti, L.; Muzzalupo, I.; Carminati, D.; Giraffa, G. Selection of Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains to Use as Starters in Fermented Table Olives: Oleuropeinase Activity and Phage Sensitivity. Food Microbiol 2013, 34, 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Vaccalluzzo, A.; Solieri, L.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Cattivelli, A.; Martini, S.; Pino, A.; Caggia, C.; Randazzo, C.L. Metabolomic and Transcriptional Profiling of Oleuropein Bioconversion into Hydroxytyrosol during Table Olive Fermentation by Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum. Appl Environ Microbiol 2022, 88. [CrossRef]

- Romeo, F. V.; Granuzzo, G.; Foti, P.; Ballistreri, G.; Caggia, C.; Rapisarda, P. Microbial Application to Improve Olive Mill Wastewater Phenolic Extracts. Molecules 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Sciurba, L.; Indelicato, S.; Gaglio, R.; Barbera, M.; Marra, F.P.; Bongiorno, D.; Davino, S.; Piazzese, D.; Settanni, L.; Avellone, G. Analysis of Olive Oil Mill Wastewater from Conventionally Farmed Olives: Chemical and Microbiological Safety and Polyphenolic Profile for Possible Use in Food Product Functionalization. Foods 2025, 14, 449. [CrossRef]

- Cappello, M.S.; Zapparoli, G.; Logrieco, A.; Bartowsky, E.J. Linking Wine Lactic Acid Bacteria Diversity with Wine Aroma and Flavour. Int J Food Microbiol 2017, 243, 16–27. [CrossRef]

- Virdis, C.; Sumby, K.; Bartowsky, E.; Jiranek, V. Lactic Acid Bacteria in Wine: Technological Advances and Evaluation of Their Functional Role. Front Microbiol 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Boido, E.; Lloret, A.; Medina, K.; Carrau, F.; Dellacassa, E. Effect of β-Glycosidase Activity of Oenococcus Oeni on the Glycosylated Flavor Precursors of Tannat Wine during Malolactic Fermentation. J Agric Food Chem 2002, 50, 2344–2349. [CrossRef]

- Swiegers, J.H.; Bartowsky, E.J.; Henschke, P.A.; Pretorius, I.S. Yeast and Bacterial Modulation of Wine Aroma and Flavour. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2005, 11, 139–173. [CrossRef]

- Bartowsky, E.J.; Costello, P.J.; Chambers, P.J. Emerging Trends in the Application of Malolactic Fermentation. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2015, 21, 663–669. [CrossRef]

- du Toit, M.; Engelbrecht, L.; Lerm, E.; Krieger-Weber, S. Lactobacillus: The Next Generation of Malolactic Fermentation Starter Cultures—an Overview. Food Bioproc Tech 2011, 4, 876–906. [CrossRef]

- Krieger-Weber, S.; Heras, J.M.; Suarez, C. Lactobacillus Plantarum, a New Biological Tool to Control Malolactic Fermentation: A Review and an Outlook. Beverages 2020, 6, 23. [CrossRef]

- Berbegal, C.; Peña, N.; Russo, P.; Grieco, F.; Pardo, I.; Ferrer, S.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. Technological Properties of Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains Isolated from Grape Must Fermentation. Food Microbiol 2016, 57, 187–194. [CrossRef]

- Succi, M.; Pannella, G.; Tremonte, P.; Tipaldi, L.; Coppola, R.; Iorizzo, M.; Lombardi, S.J.; Sorrentino, E. Sub-Optimal PH Preadaptation Improves the Survival of Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains and the Malic Acid Consumption in Wine-like Medium. Front Microbiol 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Tufariello, M.; Capozzi, V.; Spano, G.; Cantele, G.; Venerito, P.; Mita, G.; Grieco, F. Effect of Co-Inoculation of Candida Zemplinina, Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and Lactobacillus Plantarum for the Industrial Production of Negroamaro Wine in Apulia (Southern Italy). Microorganisms 2020, Vol. 8, Page 726 2020, 8, 726. [CrossRef]

- Pannella, G.; Lombardi, S.J.; Coppola, F.; Vergalito, F.; Iorizzo, M.; Succi, M.; Tremonte, P.; Iannini, C.; Sorrentino, E.; Coppola, R. Effect of Biofilm Formation by Lactobacillus Plantarum on the Malolactic Fermentation in Model Wine. Foods 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Ferrada, B.M.; Hollmann, A.; Delfederico, L.; Valdés La Hens, D.; Caballero, A.; Semorile, L. Patagonian Red Wines: Selection of Lactobacillus Plantarum Isolates as Potential Starter Cultures for Malolactic Fermentation. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2013, 29, 1537–1549. [CrossRef]

- Balmaseda, A.; Rozès, N.; Bordons, A.; Reguant, C. Characterization of Malolactic Fermentation by Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum in Red Grape Must. LWT 2024, 199, 116070. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, S.J.; Pannella, G.; Iorizzo, M.; Testa, B.; Succi, M.; Tremonte, P.; Sorrentino, E.; Di Renzo, M.; Strollo, D.; Coppola, R. Inoculum Strategies and Performances of Malolactic Starter Lactobacillus Plantarum M10: Impact on Chemical and Sensorial Characteristics of Fiano Wine. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 516. [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Testa, B.; Lombardi, S.J.; García-Ruiz, A.; Muñoz-González, C.; Bartolomé, B.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Selection and Technological Potential of Lactobacillus Plantarum Bacteria Suitable for Wine Malolactic Fermentation and Grape Aroma Release. LWT 2016, 73, 557–566. [CrossRef]

- Devi, A.; Anu-Appaiah, K.A.; Lin, T.F. Timing of Inoculation of Oenococcus Oeni and Lactobacillus Plantarum in Mixed Malo-Lactic Culture along with Compatible Native Yeast Influences the Polyphenolic, Volatile and Sensory Profile of the Shiraz Wines. LWT 2022, 158, 113130. [CrossRef]

- Testa, B.; Coppola, F.; Iorizzo, M.; Di Renzo, M.; Coppola, R.; Succi, M. Preliminary Characterisation of Metschnikowia Pulcherrima to Be Used as a Starter Culture in Red Winemaking. Beverages 2024, 10, 88. [CrossRef]

- Brizuela, N.; Tymczyszyn, E.E.; Semorile, L.C.; Valdes La Hens, D.; Delfederico, L.; Hollmann, A.; Bravo-Ferrada, B. Lactobacillus Plantarum as a Malolactic Starter Culture in Winemaking: A New (Old) Player? Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 2019, 38, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Brizuela, N.S.; Franco-Luesma, E.; Bravo-Ferrada, B.M.; Pérez-Jiménez, M.; Semorile, L.; Tymczyszyn, E.E.; Pozo-Bayon, M.A. Influence of Patagonian Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum and Oenococcus Oeni Strains on Sensory Perception of Pinot Noir Wine after Malolactic Fermentation. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2021, 27, 118–127. [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, A.; Bartowsky, E.; Jiranek, V. Screening of Lactobacillus Spp. and Pediococcus Spp. for Glycosidase Activities That Are Important in Oenology. J Appl Microbiol 2005, 99, 1061–1069. [CrossRef]

- Gouripur, G.; Kaliwal, B. Screening and Optimization of β-Glucosidase Producing Newly Isolated Lactobacillus Plantarum Strain LSP-24 from Colostrum Milk. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2017, 11, 89–96. [CrossRef]

- Barbagallo, R.N.; Spagna, G.; Palmeri, R.; Restuccia, C.; Giudici, P. Selection, Characterization and Comparison of β-Glucosidase from Mould and Yeasts Employable for Enological Applications. Enzyme Microb Technol 2004, 35, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Olguín, N.; Alegret, J.O.; Bordons, A.; Reguant, C. β-Glucosidase Activity and Bgl Gene Expression of Oenococcus Oeni Strains in Model Media and Cabernet Sauvignon Wine. Am J Enol Vitic 2011, 62, 99–105. [CrossRef]

- Fia, G.; Millarini, V.; Granchi, L.; Bucalossi, G.; Guerrini, S.; Zanoni, B.; Rosi, I. Beta-Glucosidase and Esterase Activity from Oenococcus Oeni: Screening and Evaluation during Malolactic Fermentation in Harsh Conditions. LWT 2018, 89, 262–268. [CrossRef]

- Lorn, D.; Nguyen, T.-K.-C.; Ho, P.-H.; Tan, R.; Licandro, H.; Waché, Y. Screening of Lactic Acid Bacteria for Their Potential Use as Aromatic Starters in Fermented Vegetables. Int J Food Microbiol 2021, 350, 109242. [CrossRef]

- Landete, J.M.; Curiel, J.A.; Rodríguez, H.; de las Rivas, B.; Muñoz, R. Aryl Glycosidases from Lactobacillus Plantarum Increase Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic Compounds. J Funct Foods 2014, 7, 322–329. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Y.; Zhu, H.-Z.; Lan, Y.-B.; Liu, R.-J.; Liu, Y.-R.; Zhang, B.-L.; Zhu, B.-Q. Modifications of Phenolic Compounds, Biogenic Amines, and Volatile Compounds in Cabernet Gernishct Wine through Malolactic Fermentation by Lactobacillus Plantarum and Oenococcus Oeni. Fermentation 2020, 6, 15. [CrossRef]

- Sestelo, A.B.F.; Poza, M.; Villa, T.G. β-Glucosidase Activity in a Lactobacillus Plantarum Wine Strain. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2004, 20, 633–637. [CrossRef]

- Brizuela, N.S.; Arnez-Arancibia, M.; Semorile, L.; Pozo-Bayón, M.Á.; Bravo-Ferrada, B.M.; Elizabeth Tymczyszyn, E. β-Glucosidase Activity of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum UNQLp 11 in Different Malolactic Fermentations Conditions: Effect of PH and Ethanol Content. Fermentation 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Van Oevelen, D.; Spaepen, M.; Timmermans, P.; Verachtert, H. MICROBIOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SPONTANEOUS WORT FERMENTATION IN THE PRODUCTION OF LAMBIC AND GUEUZE. Journal of the Institute of Brewing 1977, 83, 356–360. [CrossRef]

- Dysvik, A.; La Rosa, S.L.; De Rouck, G.; Rukke, E.-O.; Westereng, B.; Wicklund, T. Microbial Dynamics in Traditional and Modern Sour Beer Production. Appl Environ Microbiol 2020, 86. [CrossRef]

- Testa, B.; Coppola, F.; Letizia, F.; Albanese, G.; Karaulli, J.; Ruci, M.; Pistillo, M.; Germinara, G.S.; Messia, M.C.; Succi, M.; et al. Versatility of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae 41CM in the Brewery Sector: Use as a Starter for “Ale” and “Lager” Craft Beer Production. Processes 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Karaulli, J.; Xhaferaj, N.; Coppola, F.; Testa, B.; Letizia, F.; Kyçyk, O.; Kongoli, R.; Ruci, M.; Lamçe, F.; Sulaj, K.; et al. Bioprospecting of Metschnikowia Pulcherrima Strains, Isolated from a Vineyard Ecosystem, as Novel Starter Cultures for Craft Beer Production. Fermentation 2024, 10, 513. [CrossRef]

- Iorizzo, M.; Letizia, F.; Albanese, G.; Coppola, F.; Gambuti, A.; Testa, B.; Aversano, R.; Forino, M.; Coppola, R. Potential for Lager Beer Production from Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Strains Isolated from the Vineyard Environment. Processes 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bossaert, S.; Crauwels, S.; Lievens, B.; De Rouck, G. The Power of Sour - A Review: Old Traditions, New Opportunities. BrewingScience 2019, 72, 78–88.

- Mahanta, S.; Sivakumar, P.S.; Parhi, P.; Mohapatra, R.K.; Dey, G.; Panda, S.H.; Sireswar, S.; Panda, S.K. Sour Beer Production in India Using a Coculture of Saccharomyces Pastorianus and Lactobacillus Plantarum: Optimization, Microbiological, and Biochemical Profiling. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2022, 53, 947–958. [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, J.; Sheng, G.; Lu, J. The Mechanisms of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum J6-6 against Iso-α-Acid Stress and Its Application in Sour Beer Production. Systems Microbiology and Biomanufacturing 2024, 4, 1018–1027. [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, L.; Sahin, A.W.; Arendt, E.K. Co-Fermentation of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts with Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum FST 1.7 for the Production of Non-Alcoholic Beer. European Food Research and Technology 2023, 249, 167–181. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Tornay, A.; Díaz, A.B.; Lasanta, C.; Durán-Guerrero, E.; Castro, R. Co-Fermentation of Lactic Acid Bacteria and S. Cerevisiae for the Production of a Probiotic Beer: Survival and Sensory and Analytical Characterization. Food Biosci 2024, 57. [CrossRef]

- Das, A.J.; Seth, D.; Miyaji, T.; Deka, S.C. Fermentation Optimization for a Probiotic Local Northeastern Indian Rice Beer and Application to Local Cassava and Plantain Beer Production. Journal of the Institute of Brewing 2015, 121, 273–282. [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Wei, B.; Qin, C.; Huang, L.; Xia, N.; Teng, J. Enhancing the Inhibitory Activities of Polyphenols in Passion Fruit Peel on α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase via β-Glucosidase-Producing Lactobacillus Fermentation. Food Biosci 2024, 62, 105005. [CrossRef]

- Aron, P.M.; Shellhammer, T.H. A Discussion of Polyphenols in Beer Physical and Flavour Stability. Journal of the Institute of Brewing 2010, 116, 369–380. [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, G.; Bravi, E.; Sanarica, E.; Marconi, O.; Cappelletti, F.; Perretti, G. Effect of Addition of Different Phenolic-Rich Extracts on Beer Flavour Stability. Foods 2020, 9, 1638. [CrossRef]

- Dasenaki, M.E.; Thomaidis, N.S. Quality and Authenticity Control of Fruit Juices-A Review. Molecules 2019, 24, 1014. [CrossRef]

- Plessas, S. Advancements in the Use of Fermented Fruit Juices by Lactic Acid Bacteria as Functional Foods: Prospects and Challenges of Lactiplantibacillus (Lpb.) Plantarum Subsp. Plantarum Application. Fermentation 2021, 8, 6. [CrossRef]

- Montet, D.; Ray, R.C.; Zakhia-Rozis, N. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Vegetables and Fruits; 2014; ISBN 9781482223095.

- Yuan, X.; Wang, T.; Sun, L.; Qiao, Z.; Pan, H.; Zhong, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Recent Advances of Fermented Fruits: A Review on Strains, Fermentation Strategies, and Functional Activities. Food Chem X 2024, 22, 101482. [CrossRef]

- Septembre-Malaterre, A.; Remize, F.; Poucheret, P. Fruits and Vegetables, as a Source of Nutritional Compounds and Phytochemicals: Changes in Bioactive Compounds during Lactic Fermentation. Food Research International 2018, 104, 86–99. [CrossRef]

- Gustaw, K.; Niedźwiedź, I.; Rachwał, K.; Polak-Berecka, M. New Insight into Bacterial Interaction with the Matrix of Plant-Based Fermented Foods. Foods 2021, Vol. 10, Page 1603 2021, 10, 1603. [CrossRef]

- Sevindik, O.; Guclu, G.; Agirman, B.; Selli, S.; Kadiroglu, P.; Bordiga, M.; Capanoglu, E.; Kelebek, H. Impacts of Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains on the Aroma and Bioactive Compositions of Fermented Gilaburu (Viburnum Opulus) Juices. Food Chem 2022, 378, 132079. [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, R.; Coda, R.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. Exploitation of Vegetables and Fruits through Lactic Acid Fermentation. Food Microbiol 2013, 33, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Filannino, P.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M. Metabolic and Functional Paths of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Plant Foods: Get out of the Labyrinth. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2018, 49, 64–72. [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, R.; Filannino, P.; Gobbetti, M. Lactic Acid Fermentation Drives the Optimal Volatile Flavor-Aroma Profile of Pomegranate Juice. Int J Food Microbiol 2017, 248, 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, J.; Chatterjee, S.; Gamre, S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Variyar, P.S.; Sharma, A. Analysis of Free and Bound Aroma Compounds of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.). LWT - Food Science and Technology 2014, 59, 461–466. [CrossRef]

- Cele, N.P.; Akinola, S.A.; Manhivi, V.E.; Shoko, T.; Remize, F.; Sivakumar, D. Influence of Lactic Acid Bacterium Strains on Changes in Quality, Functional Compounds and Volatile Compounds of Mango Juice from Different Cultivars during Fermentation. Foods 2022, 11, 682. [CrossRef]

- Surendran, S.; Qassadi, F.; Surendran, G.; Lilley, D.; Heinrich, M. Myrcene—What Are the Potential Health Benefits of This Flavouring and Aroma Agent? Front Nutr 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, C.; Pu, X.; Li, T.; Shi, X.; Wang, B.; Cheng, W. Flavor and Functional Analysis of Lactobacillus Plantarum Fermented Apricot Juice. Fermentation 2022, 8, 533. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wen, J.-J.; Hu, J.-L.; Nie, Q.-X.; Chen, H.-H.; Nie, S.-P.; Xiong, T.; Xie, M.-Y. Momordica Charantia Juice with Lactobacillus Plantarum Fermentation: Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Properties and Aroma Profile. Food Biosci 2019, 29, 62–72. [CrossRef]

- Mrabti, H.N.; Jaouadi, I.; Zeouk, I.; Ghchime, R.; El Menyiy, N.; Omari, N. El; Balahbib, A.; Al-Mijalli, S.H.; Abdallah, E.M.; El-Shazly, M.; et al. Biological and Pharmacological Properties of Myrtenol: A Review. Curr Pharm Des 2023, 29, 407–414. [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Cirlini, M.; Levante, A.; Dall’Asta, C.; Galaverna, G.; Lazzi, C. Volatile Profile of Elderberry Juice: Effect of Lactic Acid Fermentation Using L. Plantarum, L. Rhamnosus and L. Casei Strains. Food Research International 2018, 105, 412–422. [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, R.; Surico, R.F.; Paradiso, A.; De Angelis, M.; Salmon, J.-C.; Buchin, S.; De Gara, L.; Gobbetti, M. Effect of Autochthonous Lactic Acid Bacteria Starters on Health-Promoting and Sensory Properties of Tomato Juices. Int J Food Microbiol 2009, 128, 473–483. [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, R.; Surico, R.F.; Minervini, G.; Rizzello, C.G.; Lovino, R.; Servili, M.; Taticchi, A.; Urbani, S.; Gobbetti, M. Exploitation of Sweet Cherry (Prunus Avium L.) Puree Added of Stem Infusion through Fermentation by Selected Autochthonous Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food Microbiol 2011, 28, 900–909. [CrossRef]

- Filannino, P.; Cardinali, G.; Rizzello, C.G.; Buchin, S.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R. Metabolic Responses of Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains during Fermentation and Storage of Vegetable and Fruit Juices. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014, 80, 2206–2215. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.M.B.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Barba, F.J.; Nemati, Z.; Sohrabi Shokofti, S.; Alizadeh, F. Fermented Sweet Lemon Juice (Citrus Limetta) Using Lactobacillus Plantarum LS5: Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities. J Funct Foods 2017, 38, 409–414. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, X.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Jiang, S.; Xue, H.; Zhang, J.; Jha, R.; Wang, R. Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation Improves Physicochemical Properties, Bioactivity, and Metabolic Profiles of Opuntia Ficus-Indica Fruit Juice. Food Chem 2024, 453, 139646. [CrossRef]

- Mashitoa, F.M.; Manhivi, V.E.; Akinola, S.A.; Garcia, C.; Remize, F.; Shoko, T.; Sivakumar, D. Changes in Phenolics and Antioxidant Capacity during Fermentation and Simulated in Vitro Digestion of Mango Puree Fermented with Different Lactic Acid Bacteria. J Food Process Preserv 2021, 45. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Cao, H.; Huang, Q.; Xiao, J.; Teng, H. Absorption, Metabolism and Bioavailability of Flavonoids: A Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 7730–7742. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, T.; Hu, F.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Effect of Lactobacillus Plantarum-Fermented Mulberry Pomace on Antioxidant Properties and Fecal Microbial Community. LWT 2021, 147, 111651. [CrossRef]

- Hur, S.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-C.; Choi, I.; Kim, G.-B. Effect of Fermentation on the Antioxidant Activity in Plant-Based Foods. Food Chem 2014, 160, 346–356. [CrossRef]

- Slámová, K.; Kapešová, J.; Valentová, K. “Sweet Flavonoids”: Glycosidase-Catalyzed Modifications. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [CrossRef]

- Gaur, G.; Gänzle, M.G. Conversion of (Poly)Phenolic Compounds in Food Fermentations by Lactic Acid Bacteria: Novel Insights into Metabolic Pathways and Functional Metabolites. Curr Res Food Sci 2023, 6, 100448. [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.-B.; Lei, Y.-T.; Li, Q.-Z.; Li, Y.-C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, D.-Y. Effect of Lactobacillus Plantarum and Lactobacillus Acidophilus Fermentation on Antioxidant Activity and Metabolomic Profiles of Loquat Juice. LWT 2022, 171, 114104. [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, S.; Nagoor Meeran, M.F.; Azimullah, S.; Sharma, C.; Goyal, S.N.; Ojha, S. Nerolidol Attenuates Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis by Modulating Nrf2/MAPK Signaling Pathways in Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Cardiotoxicity in Rats. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Iqubal, A.; Syed, M.A.; Ali, J.; Najmi, A.K.; Haque, M.M.; Haque, S.E. Nerolidol Protects the Liver against Cyclophosphamide-Induced Hepatic Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Fibrosis via Modulation of Nrf2, NF-ΚB P65, and Caspase-3 Signaling Molecules in Swiss Albino Mice. Biofactors 2020, 46, 963–973. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Teng, J.; Lyu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, M. Enhanced Antioxidant Activity for Apple Juice Fermented with Lactobacillus Plantarum ATCC14917. Molecules 2018, 24, 51. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lu, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, Z.; Tian, H. Influence of 4 Lactic Acid Bacteria on the Flavor Profile of Fermented Apple Juice. Food Biosci 2019, 27, 30–36. [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Meng, D.; Yue, T.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Z. Effect of the Apple Cultivar on Cloudy Apple Juice Fermented by a Mixture of Lactobacillus Acidophilus, Lactobacillus Plantarum, and Lactobacillus Fermentum. Food Chem 2021, 340, 127922. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.M.B.; Jafarpour, D. Fermentation of Bergamot Juice with Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains in Pure and Mixed Fermentations: Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Activity and Sensorial Properties. LWT 2020, 131, 109803. [CrossRef]

- Tkacz, K.; Chmielewska, J.; Turkiewicz, I.P.; Nowicka, P.; Wojdyło, A. Dynamics of Changes in Organic Acids, Sugars and Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Sea Buckthorn and Sea Buckthorn-Apple Juices during Malolactic Fermentation. Food Chem 2020, 332, 127382. [CrossRef]

- Filannino, P.; Cavoski, I.; Thlien, N.; Vincentini, O.; De Angelis, M.; Silano, M.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Cactus Cladodes (Opuntia Ficus-Indica L.) Generates Flavonoid Derivatives with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0152575. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wei, B.-C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, Y.-J. Aroma Profiles of Sweet Cherry Juice Fermented by Different Lactic Acid Bacteria Determined through Integrated Analysis of Electronic Nose and Gas Chromatography–Ion Mobility Spectrometry. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kuerban, D.; Lu, J.; Huangfu, Z.; Wang, L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, M. Optimization of Fermentation Conditions and Metabolite Profiling of Grape Juice Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria for Improved Flavor and Bioactivity. Foods 2023, 12, 2407. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, C. Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation on Antioxidation and Bioactivity of Hawthorn Pulp. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2019, 267, 062056. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Lao, F.; Wu, J. Volatile and Non-Volatile Profiles in Jujube Pulp Co-Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria. LWT 2022, 154, 112772. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jiang, T.; Liu, N.; Wu, C.; Xu, H.; Lei, H. Biotransformation of Phenolic Profiles and Improvement of Antioxidant Capacities in Jujube Juice by Select Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food Chem 2021, 339, 127859. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, L.; Liu, B.; Meng, X. Mixed Fermentation of Jujube Juice ( Ziziphus Jujuba Mill.) with L. Rhamnosus <scp>GG</Scp> and L. Plantarum -1: Effects on the Quality and Stability. Int J Food Sci Technol 2019, 54, 2624–2631. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Deng, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Hu, Z. Elucidating the Effects of Lactobacillus Plantarum Fermentation on the Aroma Profiles of Pasteurized Litchi Juice Using Multi-Scale Molecular Sensory Science. Curr Res Food Sci 2023, 6, 100481. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Peng, Y.-J.; He, W.-W.; Song, X.-X.; He, Y.-X.; Hu, X.-Y.; Bian, S.-G.; Li, Y.-H.; Yin, J.-Y.; Nie, S.-P.; et al. Metabolomics-Based Mechanistic Insights into Antioxidant Enhancement in Mango Juice Fermented by Various Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food Chem 2025, 466, 142078. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.B.; Lim, S.H.; Sim, H.S.; Park, J.H.; Kwon, H.J.; Nam, H.S.; Kim, M.D.; Baek, H.H.; Ha, S.J. Changes in Antioxidant Activities and Volatile Compounds of Mixed Berry Juice through Fermentation by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food Sci Biotechnol 2017, 26, 441–446. [CrossRef]

- Kwaw, E.; Ma, Y.; Tchabo, W.; Apaliya, M.T.; Wu, M.; Sackey, A.S.; Xiao, L.; Tahir, H.E. Effect of Lactobacillus Strains on Phenolic Profile, Color Attributes and Antioxidant Activities of Lactic-Acid-Fermented Mulberry Juice. Food Chem 2018, 250, 148–154. [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, S.; Imtiaz, A.; Awan, K.A.; Murtaza, M.S.; Mubeen, B.; Yinka, A.A.; Boasiako, T.A.; Alsulami, T.; Rehman, A.; Khalifa, I.; et al. Impact of Fermentation through Synergistic Effect of Different Lactic Acid Bacteria (Mono and Co-Cultures) on Metabolic and Sensorial Profile of Mulberry Juice. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2024. [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, B.; Luz, C.; Puchol, C.; Meca, G.; Barba, F.J. Evaluation of Fermentation Assisted by Lactobacillus Brevis POM, and Lactobacillus Plantarum (TR-7, TR-71, TR-14) on Antioxidant Compounds and Organic Acids of an Orange Juice-Milk Based Beverage. Food Chem 2021, 343, 128414. [CrossRef]

- Dogan, K.; Akman, P.K.; Tornuk, F. Role of Non-thermal Treatments and Fermentation with Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum on in Vitro Bioaccessibility of Bioactives from Vegetable Juice. J Sci food Agric 2021, 101, 4779–4788. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, H.C.; Melo, D. de S.; Ramos, C.L.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum CCMA 0743 and Lacticaseibacillus Paracasei Subsp. Paracasei LBC-81 Metabolism during the Single and Mixed Fermentation of Tropical Fruit Juices. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2021, 52, 2307–2317. [CrossRef]

- Mantzourani, I.; Kazakos, S.; Terpou, A.; Alexopoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; Bekatorou, A.; Plessas, S. Potential of the Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum ATCC 14917 Strain to Produce Functional Fermented Pomegranate Juice. Foods 2019, Vol. 8, Page 4 2018, 8, 4. [CrossRef]

- Vivek, K.; Mishra, S.; Pradhan, R.C.; Jayabalan, R. Effect of Probiotification with Lactobacillus Plantarum MCC 2974 on Quality of Sohiong Juice. LWT 2019, 108, 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, Y.; He, W.; Song, X.; Peng, Y.; Hu, X.; Bian, S.; Li, Y.; Nie, S.; Yin, J.; et al. Exploring the Biogenic Transformation Mechanism of Polyphenols by Lactobacillus Plantarum NCU137 Fermentation and Its Enhancement of Antioxidant Properties in Wolfberry Juice. J Agric Food Chem 2024, 72, 12752–12761. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, J.; Xing, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Nan, B.; et al. Antioxidant Mechanism of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum KM1 Under H2O2 Stress by Proteomics Analysis. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Markkinen, N.; Laaksonen, O.; Nahku, R.; Kuldjärv, R.; Yang, B. Impact of Lactic Acid Fermentation on Acids, Sugars, and Phenolic Compounds in Black Chokeberry and Sea Buckthorn Juices. Food Chem 2019, 286, 204–215. [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Wang, S.; Gu, P.; Ouyang, X.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, B. Comparison of Physicochemical Indexes, Amino Acids, Phenolic Compounds and Volatile Compounds in Bog Bilberry Juice Fermented by Lactobacillus Plantarum under Different PH Conditions. J Food Sci Technol 2018, 55, 2240–2250. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Bangar, S.P.; Echegaray, N.; Suri, S.; Tomasevic, I.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Melekoglu, E.; Rocha, J.M.; Ozogul, F. The Impacts of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum on the Functional Properties of Fermented Foods: A Review of Current Knowledge. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

| Fruit processed | Product type | L. plantarum (Lp) strains | Main Positive Effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | Juice fermented at 37°C for 72 h. | Lp ATCC14917 | Increased antioxidant activity and decreased total phenolics and flavonoid content. | [218] |

| Apple | Juice fermented at 37°C for 80 h | Lp ST-III | Improved flavor profile | [219] |

| Apple | Single Juices from nine apple cultivars fermented at 37°C for 24 h | Lp CICC21805 | Increased terpenes D-limonene and eugenol in some apple cultivars | [220] |

| Apricot | Juice fermented at 37°C for 12 h | Lp LP56 | Increased antioxidant activity and total phenolics; improved flavor profile | [200] |

| Bergamot (Citrus Bergamia Risso) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 72 h | Single and mixed starter: Lp PTCC 1896 Lp AF1 Lp LP3 |

Increased antioxidant activity | [221] |

| Buckthorn berries (Hippophaë rhamnoides L.) |

Juice fermented at 30°C for 72 h |

Lp DSM 10492, Lp DSM 20174 Lp DSM 6872 |

Increased antioxidant activity and flavonoids | [222] |

| Cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) | Cladodes pulp fermented at 30°C for 24 h |

Single starters: Lp CIL6 Lp POM1 Lp 1MR20 |

Increased antioxidant activity and flavonoids (kaemferol and isorhamnetin) | [223] |

| Cherries (Prunus avium L.) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 48 h | Lp JYLP-375 | Improved flavor profile | [224] |

| Cranberrybush/Gilaburu (Viburnum opulus L.) | Juice fermented at 30°C for 12 days | Lp-23 | Increased antioxidant activity and terpenes | [193] |

| Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 48 h | Single starters: Lp POM1 Lp 1LE1 Lp C1 Lp 1486 Lp 285 |

Increase of terpenes and norisoprenoids (limonene, β-linalool, β-damascenone and eugenol) | [203] |

| Grapes | Juice fermented at 37°C for 32 h | Single and mixed starter: Lp 90 L. helveticus 76 L. casei |

Increased total phenolics and improved flavor profile | [225] |

| Hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida) | Pulp fermented at 37°C for 12 h | Mixed starter: Lp, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei. | Increased total phenolics and flavonoids | [226] |

| Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Milll.) | Pulp fermented at 37°C for 24 h | Lp CICC 20265 | Improved flavor profile | [227] |

| Jujube (Zizyphus jujuba Mill.) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 48 h | Lp 90 | Increased antioxidant activity and flavor profile | [228] |

| Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Milll.) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 28 h | Single and mixed starter: L. rhamnosus GG, Lp-1 Lp-2 L. paracasei 22709 L. mesenteroides 22264 |

Decreased total phenolics and increased total flavonoid content; improved flavor profile |

[229] |

| Lemon (Citrus limetta) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 48 h | Lp LS5 | Increased antioxidant activity | [207] |

| Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn. | Juice fermented at 37 °C for 40 h | Single starters: Lp LP28 Lp LP226 Lp LPC2W |

Increased terpenes citronellol, linalool, geraniol, prenol | [230] |

| Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) | Juice fermented at 36°C for 48 h | Lp LZ 2-2 | Increased antioxidant activity, total phenolics and total flavonoids | [215] |

| Mango (Mangifera indica L.) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 48 h | Lp NCU116 | Increased antioxidant activity and total phenolics | [231] |

| Mango (Mangifera indica L.) | Juice fermented at 30°C for 72 h | Single and mixed starter Lp L75, Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides L 56 |

Increased antioxidant activity and improved flavor profile | [198] |

| Mixed berry (acai berry, aronia, cranberry) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 36 h | Lp LP-115 | Increased antioxidant activity | [232] |

| Momordica charantia L. | Juice fermented at 37°C for 48 h | Lp NCU116 | Increased antioxidant activity, total phenolics and total flavonoids | [201] |

|

Mulberry (Morus nigra) |

Juice fermented at 37°C for 36 h | Lp ATCC SD5209 | Increased antioxidant activity and phenolics (phenolic acids, anthocyanins and flavonols) | [233] |

|

Mulberry (Morus nigra) |

Juice fermented at 37°C for 7 days | Lp CICC 20265 | Increased antioxidant activity | [211] |

|

Mulberry (Morus nigra) |

Juice fermented at 37°C for 48 h | Lp (single colture and/or in co-colture with other LAB) | Improvement of both nutritional and aromatic profile | [234] |

| Orange | Juice-milk fermented at 37 °C for 72 h | Single starters: Lp TR-7 Lp TR-71 Lp TR-14 |

Increased antioxidant activity and total phenolics | [235] |

| Orange, lemon, celery and carrot | Mixed vegetable juice fermented at 37°C for 24 h | Lp HFC8 | Increased antioxidant activity and phenolics (flavonoids, and anthocyanins) | [236] |

| Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis), acerola (Malpighia emarginata), and jelly palm (Butia capitata) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 24 h | Lp CCMA 0743 | Increased flavonoids | [237] |

| Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) | Juice fermented at 30°C for 24 h | Lp ATCC 14917 | Increased antioxidant activity and total phenolics | [238] |

| Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) | Juice fermented at 30°C for 120 h | Single starter: Lp C2 Lp POM1 |

Improved flavor profile | [196] |

| Sohiong (Prunus nepalensis) | Juice fermented at 37°C for 72 h | Lp MCC 297 | Increased antioxidant activity, total phenolics, and anthocyanins | [239] |

| Wolfberry | Juice fermented at 37°C for 48 h | Lp NCU137 | Increased antioxidant activity and free phenolics | [240] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).