Submitted:

22 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

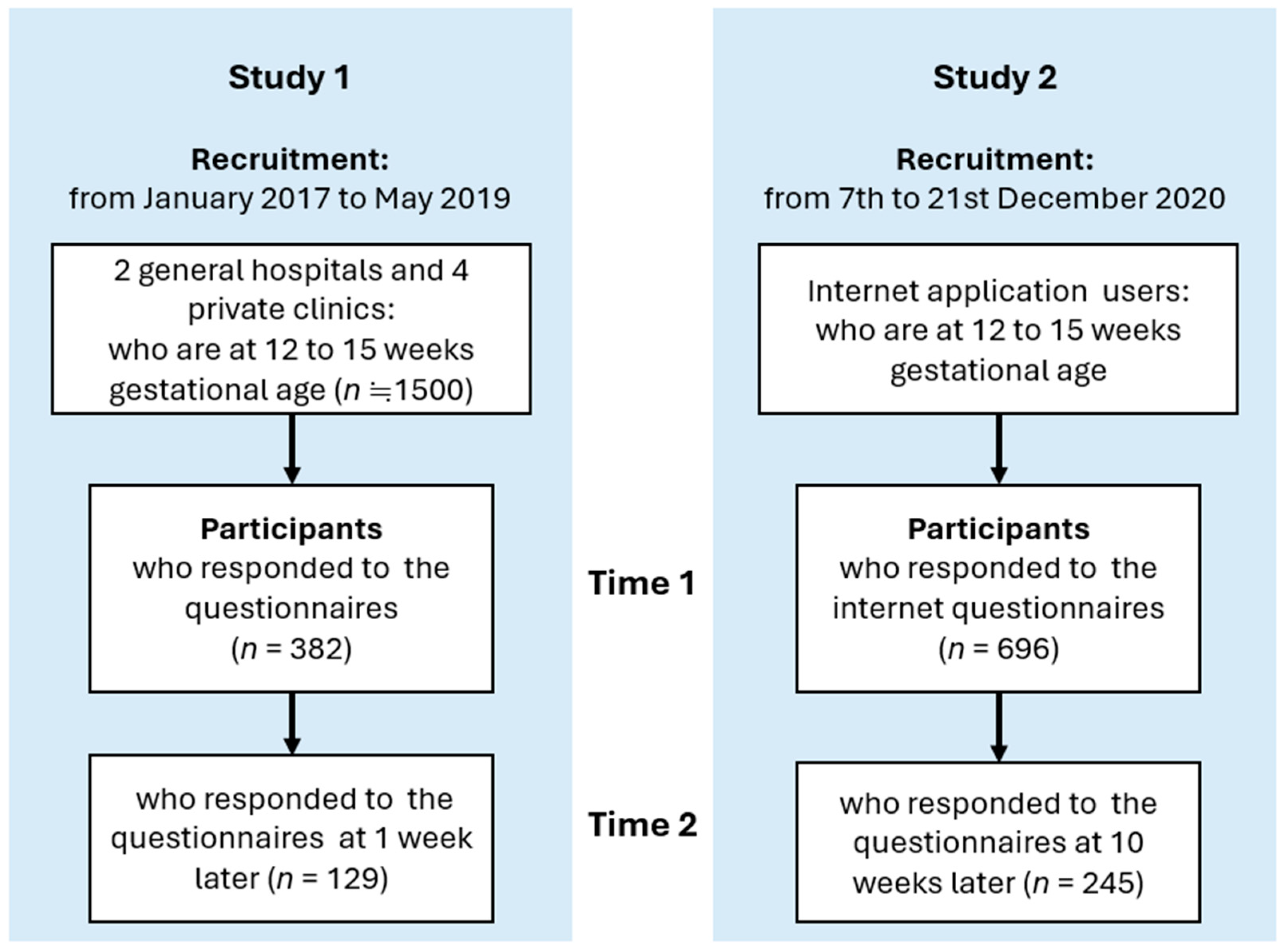

2.1. Study Procedures and Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interests

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Kitamura, T.; Yoshida, K.; Okano, T.; Kinoshita, K.; Hayashi, M.; Toyoda, N.; Ito, M.; Kudo, N.; Tada, K.; Kanazawa, K.; Sakumoto, K.; Satoh, S.; Furukawa, T.; Nakano, H. Multicentre prospective study of perinatal depression in Japan: Incidence and correlates. Arch. Women Ment. Health 2006, 9, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, T.; Sugawara, M.; Sugawara, K.; Toda, M. A.; Shima, S. Psychosocial study of depression in early pregnancy. Br. J. Psychiatry 1996, 168, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, T.; Shima, S. : Sugawara, M.; Toda, M. A. Clinical and psychosocial correlates of antenatal depression: A review. Psychother. Psychosom. 1996, 65, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gadsby, R.; Barnie-Adshead, M.; Jagger, C. A prospective study of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. BJGP 1993, 43, 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Seng, J. S.; Schrot, J. A.; van de Ven, C.; Liberzon, I. Service use data analysis or pre-pregnancy psychiatric and somatic diagnosis in women with hyperemesis gravidarum. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007, 28, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Koot, M. H.; Boelig, R. C.; van’t Hooft, J.; Limpens, J.; Rosebom, T. J.; Painter, R. C.; Grooten, I. J. Variation in hyperemesis gravidarum definition and outcome reporting in randomised clinical trials: A systematic review. BJOG 2018, 125, 1514–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Poursharif, B.; Korst, L. M.; Fejzo, M.; MacGibbon, K. W.; Romero, R.; Goodwin, T. M. The psychosocial burden of hyperemesis gravidarum. J. Neonatol. 2008, 28, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, H.; McKellar, L. V.; Lightbody, M. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: Blooming or bloomin’ awful? A review of the literature. Women Birth, 26.

- Aksoy, H.; Aksoy, U.; Karadağ, Ō. I.; Hacimusalar, Y.; Açmaz, G.; Aykut, G.; Çağli, F.; Yücel, B.; Aydin, T.; Babayiğit, A. Depression levels in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum: A prospective case-control study. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Fell, D. B.; Dodds, L.; Joseph, K. S.; Allen, V. M.; Butler, B. Risk factors for hyperemesis gravidarum requiring hospital admission during pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Hizli, D.; Kamalak, Z.; Kosus, A.; Kosus, N.; Akkurt, G. Hyperemesis gravidarum and depression in pregnancy: Is there an association? J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012, 33, 171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Jones, N.; Gallos, I.; Farren, J.; Tobias, A.; Bottomley, C.; Bourne, T. Psychological morbidity associated with hyperemesis gravidarum: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2016, 124, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pirimoglu, Z. M.; Guzelmeric, K.; Alpay, B.; Balcik, O.; Unal, O.; Turan, M. Psychological factors of hyperemesis gravidarum by using the SCL-90-R questionnaire. CEOG 2009, 37, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldgaard, H. K.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; Benth, J. Š.; Vikanes, V. Å. Hyperemesis gravidarum and the risk of emotional distress during and after pregnancy. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2017, 20, 747–756. [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldgaard, H. K.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; Benth, J. Š.; Nordeng, H.; Vikanes, V. Å. History of depression and risk of hyperemesis gravidarum: A population-based cohort study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2017, 20, 397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou-Smith, J.; Gold, J. I.; Romero, R.; Goodwin, T. M.; MacGibbon, K. W.; Mullin, P. M.; Fejzo, M. S. Posttraumatic stress symptoms following pregnancy complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011, 24, 1307–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldgaard, H. K.; Vikanes, Å.; Benth, J. Š.; Junge, C.; Garthus-Niegel, S.; Eberhard-Gran, M. The association between the degree of nausea in pregnancy and subsequent posttraumatic stress. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2019, 22, 493–501. [Google Scholar]

- Mullin, P. M.; Ching, C.-Y.; Schoenberg, F.; MacGibbon, Romero, R. ; Goodwin, T. M.; Fejzo, M. S. Risk factors, treatments, and outcome associated with prolonged hyperemesis gravidarum. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 632–636. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Jones, N.; Lawson, K.; Bobdiwala, S.; Farren, J. A.; Tobias, A.; Bourne, T. Bottomley, C. Association between hyperemesis gravidarum and psychological symptoms, psychological outcomes and infant bonding: A two-point prospective case-control multicentre survey study in an inner city setting. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039715. [Google Scholar]

- Muchanga, S. M. J.; Eitoku, M.; Mbelambela, E. P.; Ninomiya, H.; Iiyama, T.; Komori, K.; Yasumitsu-Lovell, K.; Mitsuda, N.; Tozin, R. R.; Maeda, N.; Fujieda, M.; Suganuma, N.; for the Japan Environment and Children’s Study Group. Association between nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and postpartum depression: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 43, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki, M.; Ohtsuki, T.; Yonemoto, N.; Kawashima, Y.; Saitoh, A.; Oikawa, Y.; Kurosawa, M.; Muramatsu, K.; Furukawa, T. A.; Yamada, M. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 and PHQ-2 in general internal medicine primary care at a Japanese rural hospital: A cross-sectional study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 592–597. [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu, K.; Kamijima, K. Puraimarikea shinnryou to utubyou sukuri-ningu tsuru: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 nihongoban ‘Kokoroto Karadano Shitsumonhyou’ (Primary care and depression screening tool: The Japanese version of the Patient health Questionnaire-9 ‘Questionnaire of Mind and Body’). Shindan to Chiryou 2009, 97, 1465–1473. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R. L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J. B. W. ; the Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA 1999, 282, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wakamatsu, M.; Minatani, M.; Hada, A.; Kitamura, T. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 among first-trimester pregnant women in Japan: Factor structure and measurement and structural invariance between nulliparas and multiparas and across perinatal measurement time points. Open J. Depress. 2021, 10, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Poursharif, B.; Korst, L. M.; MacGibbon, K. W.; Fejzo, M.; Romero, R.; Goodwin, T. M. Elective pregnancy termination in a large cohort of women with hyperemesis gravidarum. Contraception 2007, 76, 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Hada, A.; Minatani, M.; Wakamatsu, M.; Koren, G.; Kitamura, T. The pregnancy-unique quantification of emesia and nausea (PUQE-24): Configural, measurement, and structural invari-ance between nulliparas and multiparas and across two measurement time points. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1553. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, T.; Usui, Y.; Wakamatsu, M.; Minatani, M.; Hada, A. Core symptoms of antenatal depression: A study using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 among Japanese pregnant women in the first trimester. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. Just one question: If one question works, why ask several? J Epidemiol Community Health 2005, 59, 342–345. [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov, H. M.; Wilson, K. G.; Enns, M.; Lander, S. Are you depressed?”: Screening for depression in the terminally ill. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 674–676. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, C. B.; Legano, L. A.; Dreyer, B. P.; Fierman, A. H.; Berkule, S. B.; Lusskin, S. I.; Tomopoulos, S.; Roth, M.; Medelsohn, A. L. Screening for maternal depression in a low education population using a two-item questionnaire. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2007, 10, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, A. G. E. M.; van Lanschot, J. J. B.; Stalmeier, P. F. M.; van Sandick, J. W.; Hulscher, J. B. F.; de Haes, J. C. J. M.; Sprangers, M. A. G. Is a single-item visual analogue scale as valid, reliable and responsive as multi-item scales in measuring quality of life? QUAL LIFE RES 2004, 13, 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Mishina, H.; Hayashino, Y.; Fukuhara, S. Test performance of two-question screening for postpartum depressive symptoms. Pediatr Int. 2009, 51, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A. Are one or two simple questions sufficient to detect depression in cancer and palliative care? A Bayesian meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 98, 1934–1943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A. J.; Coyne, J. C. Do ultra-short screening instruments accurately detect depression in primary care? A pooled analysis and meta-analysis of 22 studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2007, 57, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Richardson, L. P.; Rockhill, C.; Russo, J. E. , et al. Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e1097–e11103. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, N.; Maltepe, C.; Bournissen, F. G.; Koren, G. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: Using the 24-Hour Pregnancy-Unique Quantification of Emesis (PUQE-24) Scale. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Canada 2009, 31, 803–807. [Google Scholar]

- Koot, M. H.; Grooten, I. J.; van der Post, J. A.; Bais, J. M.; Ris-Stalpers, C.; Leeflang, M. M. . Painter, R. C. Determinants of disease course and severity in hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020, 245, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, G.; Cohen, R. Measuring the severity of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy; a 20-year perspective on the use of the pregnancy-unique quantification of emesis (PUQE). J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021, 41, 335–339. [Google Scholar]

- Magee, L. A.; Chandra, K.; Mazzotta, P.; Stewart, D.; Koren, G.; Guyatt, G. H. Development of a health-related quality of life instrument for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, S232–S238. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, T.; Otsubo, T.; Tsuchida, H.; Wada, Y.; Kamijima, K.; Fukui, K. Sheehan Disability Scale (SDISS) nihongoban no sakusei to shinraisei oyobi datousei no kentou (The Japanese version of the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDISS): Development, reliability and validity). Japanese J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004, 7, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.V. The anxiety disease. Scribner 1983.

- Arbuckle, R.; Frye, M.; Brecher, M.; Paulsson, B.; Rajagopalam, K.; Palmer, S.; Innocenti, A. D. The psychometric validation of the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) in patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 165, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hada, A.; Imura, M.; Kitamura, T. Development of a scale for parent-to-baby emotions: Concepts, design, and factor structure Psychiatry Clin. Reports 2022, 1; e30.

- Hada, A.; Takeda, S.; Imura, M.; Kitmamura, T. Development and validation of a short version of the Scale for Parent to Baby Emotions (SPBE-20): Conceptual replication among pregnant women in Japan. Psychol 2023, 14, 1085–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. All emotions are basic. In P., Ekman, R., Davidson. (Eds.). The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. Oxford University Press 1994.

- Ekman, P.; Levenson, R. W.; Friesen, W. V. Autonomic nervous system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science 1983, 221, 1208–1210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tangney, J. P. Assessing individual differences in proneness to shame and guilt: Development of the Self-Conscious Affect and Attribution Inventory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990, 59, 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, H.; Tsuchiyagaito, A.; Hirano, Y.; Oshima, F.; Asano, K.; Sugiura, Y.; Kobori, O.; Ishikawa, R.; Nishinaka, H.; Shimizu, E.; Nakagawa, A. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R). Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B.; Huppert, J. D.; Leiberg, S.; Langner, R.; Kichic, R.; Hajcak, G.; Salkovskis, P. M. The obsessive-compulsive inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychol. Assess. 2020, 14, 485–496. [Google Scholar]

- Takegata, M.; Haruna, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Shiraishi, M.; Murayama, R.; Okano, T.; Severinsson, E. Translation and validation of the Japanese version of the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire version A. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijma, K.; Wijma, B.; Zar, M. Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ; A new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1998, 19, 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, F.; Kataoka, Y.; Kitamura, T. Development and validation of a short version of the primary scales of the Inventory of Personality Organization: A study among Japanese university students, Psychology 2022, 13, 872–890. 13.

- Kernberg, O. F.; Clarkin, J. F. IPO.1995, New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center.

- Burton, L. J.; Mazerolle, S. M. Survey instrument validity Part I: Principles of survey instrument development and validity in athletic training education research. Athl. Train. Educ. J. 2011, 6, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. SEM. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cliff, N. Some cautions concerning the application of causal modelling methods. Multivariate Behav Res. 1983, 18, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cudeck, R.; Browne, M. W. Cross-validation of covariance structure. Multivariate Behav Res. 1983, 18, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Romera, I.; Delgado-Cohen, H.; Prez, T.; Caballero, L.; Gilaberte, I. Factor analysis of the Zung self-rating depression scale in a large sample of patients with major depressive disorder in primary care. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Borgen, F. H.; Barnett, D. C. Applying cluster analysis in counselling psychology research. J. Couns. Psychol. 1987, 34, 456–468. [Google Scholar]

- Satish, S. M.; Bharadhwaj, S. Information search behaviour among new car buyers: A two-step cluster analysis. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2010, 22, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Mooi, E. A concise guide to market research: The process, data, and methods using IBM SPSS statistics. Springer 2014.

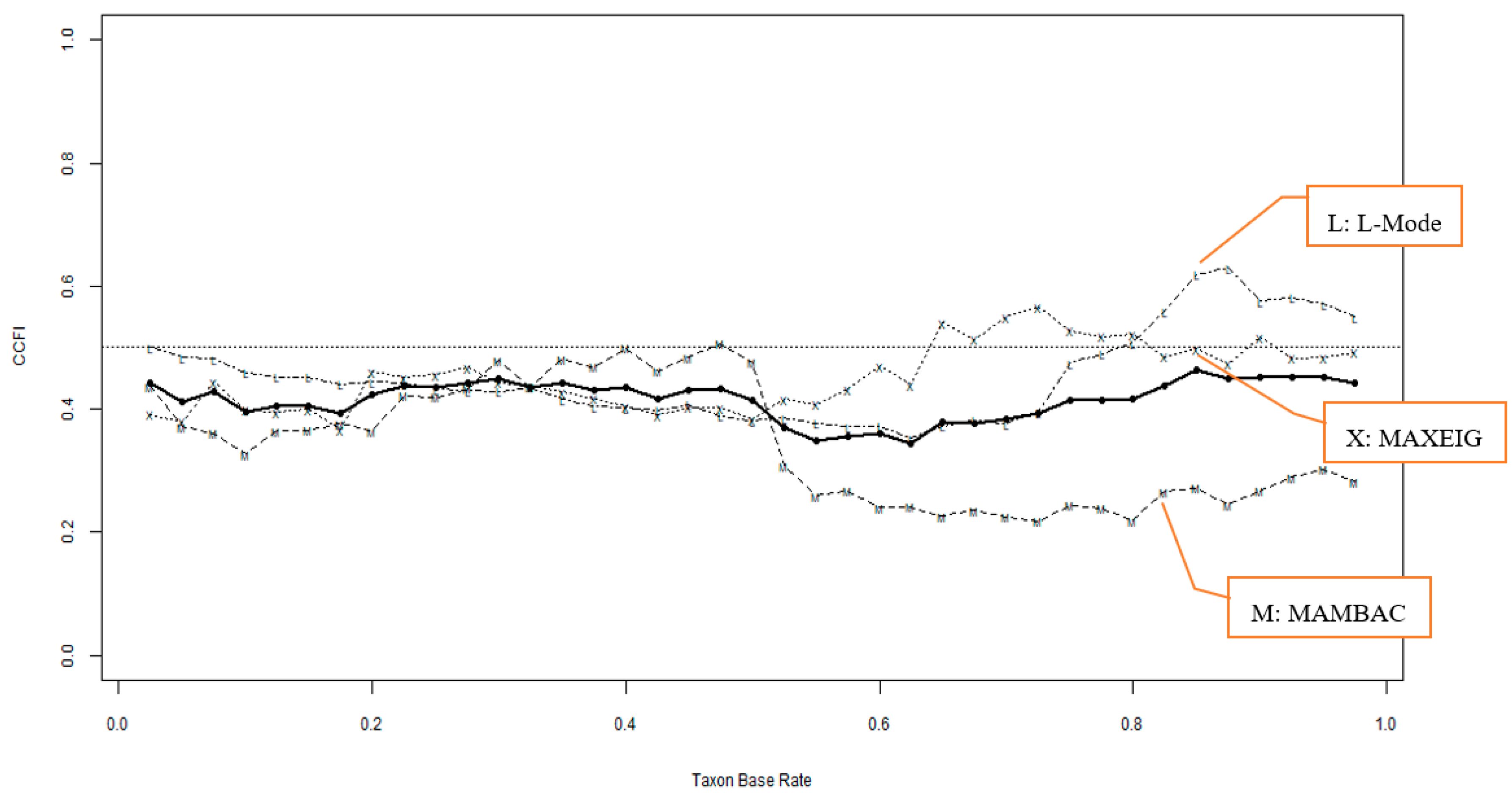

- Meehl, P. E.; Yonce, L. J. Taxometric analysis: I. Detecting taxonicity with two quantitative indicators using means above and below a sliding cut (MAMBAC procedure). Psychol. Rep. 1059; (3. [Google Scholar]

- Meehl, P. E.; Yonce, L. J. Taxometric analysis: II. Detecting taxonicity using covariance of two quantitative indicators in successive intervals of a third indicator (Maxcov procedure). Psychol. Rep. 1091; (3. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, N. G.; Meehl, P. E. Multivariate taxometric procedures: Distinguishing types from continua. Sage Publications. 1998.

- Ruscio, J.; Walters, G. D.; Marcus, D. K.; Kaczetow, W. Comparing the relative fit of categorical and dimensional latent variable models using consistency tests. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio, J.; Carney, L. M.; Dever, L.; Pliskin, M.; Wang, S. B. Using the Comparison Curve Fit Index (CCFI) in taxometric analyses: Averaging curves, standard errors, and CCFI profiles. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 744–754. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio, J.; Wang, S.B. RTaxometrics: Taxometric Analysis. R package version 3.2. 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/package=RTaxometrics.

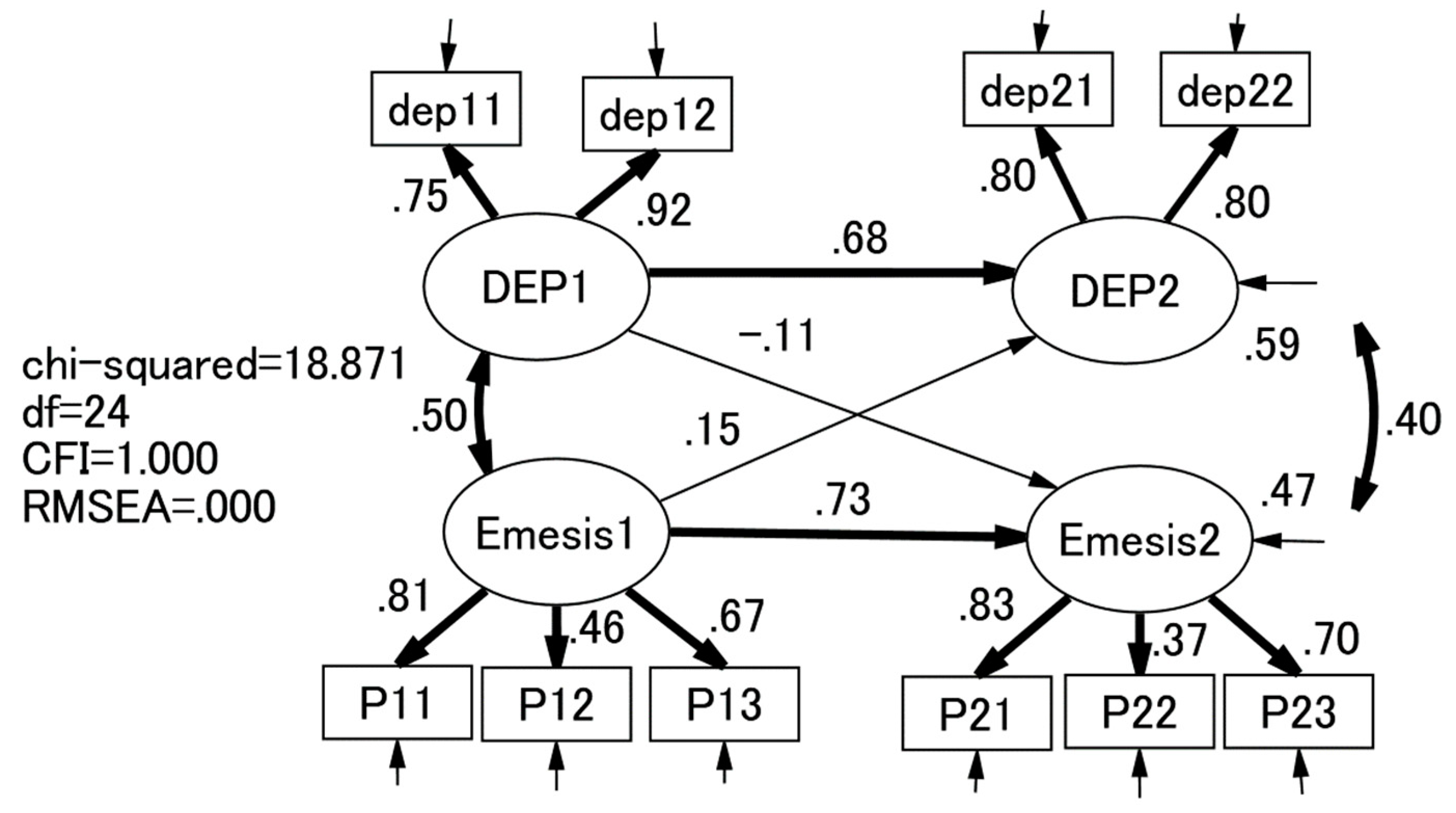

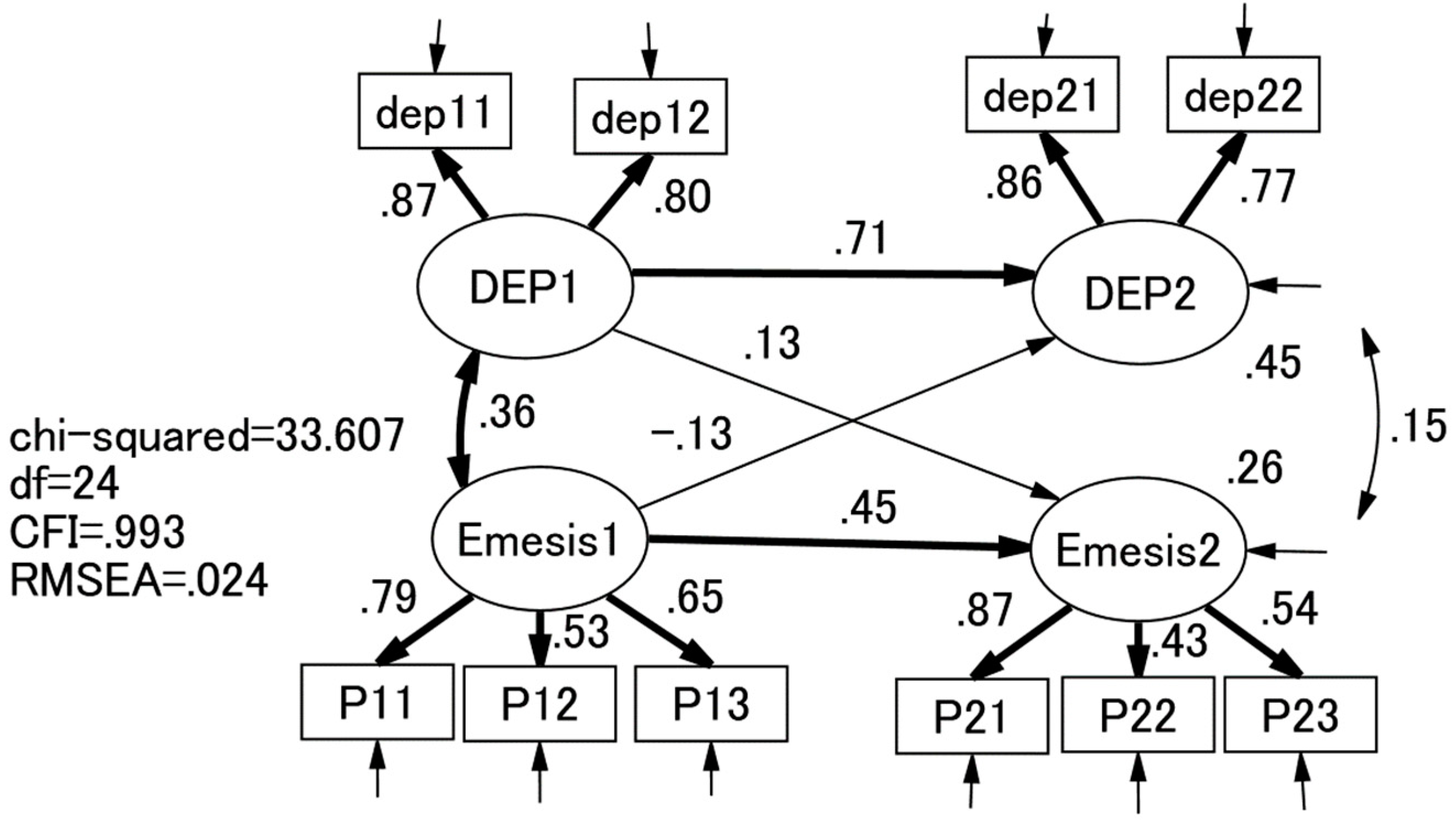

- Orth, U.; Clark, D. A.; Donnellan, M. B.; Robins, R. W. Testing prospective effects in longitudinal research: Comparing seven competing cross-lagged models. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2021, 120, 1013–1034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klein, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modelng (2nd ed.). Guilford, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M.; Freeman, E. M. Tests for stability in linear structural equation systems. Psychometrika 1983, 48, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J. Effect analysis in structural equation models. SMR 1980, 9, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio, J.; Ruscio, A.M.; Haslam, N. Introduction to the taxometric method: A practical guide (1st ed.). Routledge 2006. [CrossRef]

- Ruscio, J.; Ruscio, A. M.; Carney, L. M. Performing taxometric analysis to distinguish categorical and dimensional variables. J. Exp. Psychopathol. 2011, 2, 170196. [Google Scholar]

- Bustos, M.; Venkataramanan, R.; Caritis, S. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: What's new? Auton Neurosci. 2017, 202, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borner, T; Pataro A.M.; De Jonghe, B.C.; Central mechanisms of emesis: A role for GDF15. Neurogastroenterol Motil, e: 00, 1488. [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Jomeen, J.; Martin, C. R. Replicability and stability of the multidimensional model of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in late pregnancy. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007, 14, 319–324. [CrossRef]

- Soyemi, A. O.; Sowunmi, O. A.; Amosu, S. M.; Babalola, E. O. Depression and quality of life among pregnant women in first and third trimesters in Abeokuta: A comparative study. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2022, 28, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suenaga, H. Comparison of response options and actual symptom frequency in the Japanese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in women in early pregnancy and non-pregnant women. BMC pregnancy childbirth. 2022, 22, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinszky, Z.; Töreki, A.; Hompoth E., A.; Dudas, R. B.; Németh, G. A more rational, theory-driven approach to analysing the factor structure of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 250, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Otsuki, E. Factor structure and measurement invariance of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale during the perinatal period: a longitudinal study of Japanese women. Minerva Psychiatry. 2024, 65, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, C.; Inada, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Shiino, T.; Ando, M.; Aleksic, B.; Yamauchi, A.; Morikawa, M.; Okada, T.; Ohara, M.; Sato, M.; Murase, S.; Goto, S.; Kanai, A.; Ozaki, N. Stable factor structure of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale during the whole peripartum period: Results from a Japanese prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 17659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefana, A.; Langfus, J. A.; Palumbo, G.; Cena, L.; Trainini, A.; Gigantesco, A.; Mirabella, F. Comparing the factor structures and reliabilities of the EPDS and the PHQ-9 for screening antepartum and postpartum depression: A multigroup confirmatory factor analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2023, 26, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Oudenhove, L.; Jasper, F.; Walentynowicz, M.; Witthöft, M.; van den Bergh, O.; Tack, J. The latent structure of the functional dyspepsia symptom complex: A taxometric analysis. NEUROGASTROENT MOTIL 2016, 28, 985–993. [Google Scholar]

- Salomonsson, B. Psychodynamic interventions in pregnancy and infancy: Clinical and theoretical perspectives. Routledge 2018.

- Sartori, J.; Petersen, R.; Coall, D. A.; Quinlivan, J. The impact of maternal nausea and vomiting in pregnancy on expectant fathers: Findings from the Australian Fathers’ Study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 39, 252–258. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Mean | SD | skewness | kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: depressed mood | 1.52 1.62 |

0.73 0.80 |

1.53 1.33 |

2.37 1.39 |

--- | |||

| 2: loss of interest | 1.70 1.64 |

0.87 0.75 |

1.18 1.23 |

0.74 1.50 |

.63*** .73*** |

--- | ||

| 3: nausea | 3.10 2.70 |

1.50 1.45 |

-0.05 0.38 |

-1.36 0.13 |

.22*** .19*** |

.41*** .19*** |

--- | |

| 4: vomitting | 1.27 1.25 |

0.70 0.60 |

3.23 2.69 |

11.57 8.07 |

.26*** .23*** |

.31*** .26*** |

.37*** .40*** |

--- |

| 5: retching | 2.18 1.97 |

1.33 1.24 |

0.94 1.25 |

-0.31 0.13 |

.19** .21*** |

.35*** .25*** |

.54*** .50*** |

.45*** .33*** |

| Items | 1-factor | 2-factor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | I | II | |

| depressed mood |

.52 .83 |

-.03 .75 |

.68 .04 |

| loss of interest |

.66 .87 |

.05 .96 |

.92 -.01 |

| nausea |

.66 .27 |

.60 -.08 |

.11 .84 |

| vomitting |

.57 .33 |

.53 .12 |

.06 .47 |

| retching |

.66 .31 |

.89 -.05 |

-.10 .61 |

| Correlates | Study 1 (N = 382) | Study 2 (N = 696) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Emesis | Depression | Emesis | |

| SDS | .59*** | .39*** | ||

| Foetal bonding; happiness | -.37*** | -.05 | ||

| Foetal bonding; anger | .30*** | .14*** | ||

| Foetal bonding; fear | .32*** | .08* | ||

| Foetal bonding; sadness | .37*** | .17*** | ||

| Foetal bonding; disguat | .36*** | .23*** | ||

| Foetal bonding; surprise | .11** | -.03 | ||

| Foetal bonding; shame | .42*** | .26*** | ||

| Foetal bonding; guilt | .35*** | .11** | ||

| Foetal bonding; alpha pride | -.25*** | -.04* | ||

| Foetal bonding: beta pride | -.34*** | -.08* | ||

| Obsessive compulsive symptoms | .39*** | .14*** | ||

| Fear of child birth | .41*** | .15*** | ||

| IPO total score | .40*** | .10** | ||

| Age | .07 | .07 | -.09* | -.02 |

| Partner’s age | .14** | .06 | ||

| Study 1 (N = 382) | Study 2 (N = 696) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster I (n = 134) |

Cluster II (n = 240) |

t test (df)/χ2 | Cluster I (n = 215) |

Cluster II (n = 481) |

t test (df)/χ2 | |

| Criterion validity | ||||||

| Depression score (depressed mood + loss of interest) | 4.84 (1.64) | 2.60 (0.75) | 15.0 (164.250) *** | 4.38 (1.82) | 2.63 (0.79) | 13.5 (251.022) *** |

| Major Depressive Episose (MDE) | 44 (32.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | Fisher exact probability p < .001 | |||

| PUQE-24 total score | 8.96 (2.27) | 5.13 (1.79) | 16.9 (226.586) *** | 5.83 (2.28) | 1.65 (1.51) | 24.6 (301.843) *** |

| NVP QOL total score | 142.0 (29.1) | 84.4 (33.8) | 16.7 (300.849) *** | |||

| Construct validity | ||||||

| SDS | 12.99 (6.98) | 5.73 (5.69) | 10.3 (232.545) *** | |||

| Foetal bonding; happiness | 9.48 (2.17) | 10.30 (1.76) | 4.9 (345.350) *** | |||

| Foetal bonding; anger | 1.09 (1.99) | 0.43 (1.30) | 4.4 (298.705) *** | |||

| Foetal bonding; fear | 5.61 (2.89) | 4.44 (2.74) | 5.1 (694) *** | |||

| Foetal bonding; sadness | 2.22 (2.73) | 0.97 (1.87) | 6.1 (307.316) *** | |||

| Foetal bonding; disguat | 2.58 (3.06) | 1.06 (2.02) | 6.7 (300.546) *** | |||

| Foetal bonding; surprise | 4.04 (3.13) | 3.79 (3.23) | 1.0 (694) NS | |||

| Foetal bonding; shame | 2.88 (2.84) | 1.21 (1.91) | 7.9 (303.840) *** | |||

| Foetal bonding; guilt | 2.14 (2.86) | 1.03 (2.00) | 5.2 (310.810) *** | |||

| Foetal bonding; alpha pride | 3.91 (2.55) | 4.67 (2.54) | 3.7 (694) *** | |||

| Foetal bonding: beta pride | 8.27 (2.77) | 9.33 (2.56) | 4.8 (384.087) *** | |||

| Obsessive compulsive symptoms | 33.8 (17.1) | 25.2 (15.7) | 6.4 (694) *** | |||

| Fear of childbirth | 69.5 (22.9) | 57.9 (19.1) | 6.9 (694) *** | |||

| IPO total score | 17.3 (9.6) | 12.9 (9.3) | 5.7 (694) *** | |||

| Demographic features | ||||||

| Age | 32.6 (4.5) | 31.6 (5.0) | 1.9 (364) NS | 31.6 (4.5) | 31.8 (4.5) | 0.6 (694) NS |

| Husband’s age | 34.4 (5.0) | 33.0 (5.6) | 2.4 (304.393) * | |||

| Nulliparae | 55 (41.4%) | 111 (46.3%) | χ2 (df) = 0.64 (1) NS | |||

| rTax | rCom | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen’s d | 1: | 2: | 3: | 4: | 1: | 2: | 3: | 4: | |

| Study 1 (N = 382) | |||||||||

| intdicator 1: Depression |

1.70 | - | - | ||||||

| indicator 2: nausea |

1.59 | -0.20 | - | 0.20 | - | ||||

| indicator 3: vomitting |

1.39 | -0.14 | 0.18 | - | 0.07 | 0.22 | - | ||

| indicator 4: retching |

2.28 | -0.40 | 0.11 | 0.02 | - | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.13 | - |

| Study 2 (N = 696) | |||||||||

| intdicator 1: Depression |

1.26 | - | - | ||||||

| indicator 2: nausea |

1.95 | -0.14 | - | -0.06 | - | ||||

| indicator 3: vomitting |

1.35 | 0.08 | 0.13 | - | -0.10 | 0.21 | - | ||

| indicator 4: retching |

2.10 | -0.28 | -0.07 | 0.11 | - | -0.08 | 0.29 | 0.17 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).