1. Introduction

Kelp forests are suffering a global decline, with some regions facing almost complete local disappearances. This decline is not merely due to range shifts but rather the result of a complex set of factors that vary across different environments [

1,

2,

3] . These ecosystems are increasingly threatened by anthropogenic and climate-driven factors, including overfishing, eutrophication, pollution, ocean warming, and extreme events such as storms [

4,

5]. These stressors can have severe consequences for marine ecosystems, and projections indicate further kelp forest losses in the near future [

6,

7,

8].

Kelp forests provide a broad range of ecosystem goods and services that are ecological, economic, and social. These services include direct benefits, such as kelp harvesting, commercial and recreational fisheries, and ecotourism, as well as indirect benefits like coastal protection, nutrient cycling, carbon storage and sequestration, and mitigation of eutrophication and ocean acidification [

9,

10,

11]. Kelp forests also provide significant non-use values, including the maintenance of biodiversity, opportunities for scientific research, and cultural importance [

12]. As habitat-forming species, kelps act as ecosystem engineers, modifying their environment and creating complex three-dimensional structures that support diverse biological communities [

13]. These structures provide nursery grounds, feeding areas, and shelter for numerous marine organisms, including invertebrates, fish, and marine mammals [

10,

14,

15].

Beyond their ecological role, kelp forests play an important role in coastal defence. They can attenuate wave intensity and modify hydrodynamic flow, these effects vary with species and individuals’ morphological characteristics, such as height and robustness. By mitigating coastal erosion and stabilizing sediments, kelp forests contribute to maintaining coastal structural integrity [

16,

17]. Additionally, kelp forests enhance marine biodiversity by modifying local environmental conditions such as temperature, sedimentation, and hydrodynamics. They create complex habitats that support diverse biological communities and facilitate species recruitment [

9,

10,

18]. Given their ecological significance and growing role in coastal protection, safeguarding kelp forests is essential to ensuring the resilience of marine ecosystems [

11,

19].

As a response to ongoing declines, restoration efforts have been ongoing with various techniques, both resorting to transplantation and non-extractive approaches like green gravel. Seeding offers several advantages over transplantation: i) transplantation requires the removal of individuals from the donor population, which can negatively affect their ability to maintain population stability, ii) kelps are adapted to local environmental conditions, often growing slender stipes in areas with low hydrodynamics. When transplanted to a different location, they might not be suited to the new conditions, resulting in elevated mortality, iii) seeding, in contrast, allow producing recruits in controlled laboratory settings, enabling reforestation efforts to begin early. These individuals have also the opportunity to adapt to the local conditions from the outset. However, the seeding method is not without disadvantages. As adult kelps provide shelter and protection for juveniles, reforestation efforts based solely on recruits may experience higher mortalities due to the increased exposure to environmental conditions. Yet, summing up the pros and cons, seeding restoration methodologies are overall preferred to extractive approaches due to their almost neglectable effect on the donor populations.

Because kelps experience their highest mortality during early life stages (particularly at the microscopic phase), restoration projects relying on these stages are inherently high-risk [

20]. Cultivating kelp in a controlled laboratory setting before outplanting provides a more stable environment, reducing exposure to natural stressors such as grazing, competition, and hydrodynamic forces [

21]. This increases the survival rate of juveniles, improving the overall success of restoration efforts. Laboratory conditions enable fine-tuning the temperature, light, and nutrient levels, which are critical during early development [

22,

23]. These advantages help ensure that recruits reach a minimum size and physiological robustness necessary for higher chances of survival upon outplanting. Deploying recruits at an early developmental stage may enhance their ability to adapt to strong currents, decreasing the risk of developing fragile stipes that are more prone to breaking under natural hydrodynamic conditions. Therefore, balancing laboratory growth with timely outplanting is crucial to maximize the resilience and field performance of kelp recruits.

Among the seeding-based restoration techniques, the ‘green gravel’ method has been successfully used to restore kelp forests along the southern coast of Norway [

24], on the Portuguese coastline [

25], and in Danish waters [

26]. This method consists of sowing small rocks with kelp gametophytes and cultivating them in optimal conditions in the laboratory until they reach about 1 cm in length, after which they are outplanted at sea. While several studies have focused of the effectiveness of the method, particularly after outplanting, not many have looked into optimizing the green gravel production, improving its effectiveness and efficiency, reducing costs and creating the basis to allow scaling up the efforts [

27,

28,

29].

The golden kelp

L. ochroleuca serves as a model organism in our research. This species can be found along continental Portugal and in the seamounts of Azores, extending northward to the Northwest coasts of Spain, Brittany (France), the English and Bristol Channels, and more recently, Ireland. Further south, it has also been reported, in the Strait of Messina (Italy) and along the coast of Morocco, [

30,

31]. Ocean warming has been linked to shifts in its distribution range. At its equatorial limit,

L. ochroleuca is experiencing declines, while at its northern edge, it is expanding and increasingly outcompeting

Laminaria hyperborea [

32]. These shifts highlight the species’ ability to persist under warming conditions, particularly at its southern distribution limit, where its forests may be increasingly vulnerable to environmental change.

L. ochroleuca usually inhabits deep intertidal pools and the subtidal, down to 30m deep. Along the Portuguese coast, they are distributed between lower intertidal pools and 3-23 m deep, with an average depth of about 10 m [

33].

The main goal of this study was to optimize the green gravel method by examining how different substrates (granite, limestone, quartz, and schist) can affect kelp recruitment. While most studies testing the green gravel method have used granite, no prior research has explicitly evaluated whether it is the most efficient substrate for this technique. To address this gap, these substrates were selected as they are some of the most common in the intertidal and shallow subtidal areas and are easy to find at an accessible cost in hardware stores.

While the golden kelp Laminaria ochroleuca serves as the model organism in this study, the insights gained are likely transferable to other kelp species, given their comparable ecological functions and physiological traits.

2. Materials and Methods

Fertile tissue from 12 individuals of L. ochroleuca was collected in spring from intertidal pools in Carreço, Northern Portugal (41°44’30.3”N 8°52’38.3”W). On the day of collection, the tissue was rinsed with filtered seawater to remove epiphytes and protozoa. It was then pat-dried and stored wrapped in paper towel at 5ºC for 30 minutes to cause a slight osmotic stress. Sporulation was subsequently induced by submerging the tissue in autoclaved seawater for 2h at 5ºC. The resulting cultures were transferred to t-flasks with 0.2 µM Provasoli Enriched Seawater (PES; Provasoli, 1968) and maintained under white light (40 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) to stimulate spore germination. Once spores had developed into gametophytes, after 5 days, the stock cultures were transferred to low-intensity red light (12 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) to suppress gametogenesis while promoting vegetative growth. The culture was kept in these conditions, with weekly medium changes, for one month. This gametophyte solution was sprayed directly onto granite, limestone, quartz, and schist stones (5 cm length) covering the bottom of 50 L tanks. Three tanks were used for each gravel type (n=3). The tanks were filled one hour after spraying to allow them to better fix to the substrate. The system was kept at 15°C, the optimum temperature for this species. Recirculating water was sterilised with TitanUV Steriliser P2 110W. The tanks were illuminated with OSRAM L 58 W /965 Biolux fluorescent lights at 100 µmol m−2 s−1, with a 12:12 h light:dark photoperiod, to match the spring conditions in Portugal, when recruitment usually peaks. Environmental conditions, including dissolved oxygen, pH, salinity, and temperature, were monitored using a Hach HQ40D Portable Multi Meter. To ensure an adequate nutrient supply, Provasoli’s Enriched Seawater (PES) was used, and monitoring and water renewal were carried out on a weekly basis. Recruitment and size were monitored every week by randomly selecting 3 stones from each replicate and observed under a Leica EZ4W Stereomicroscope at a 35x magnification. Kelp length and density were measured using 15 pictures from randomly selected areas, from each of 3 stones per tank, and analysed with ImageJ (US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.4.2). To evaluate differences in kelp size in different substrates (limestone, granite, quartz, and schist) over time, non-parametric methods were employed due to violations of normality and homogeneity of variances, as determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene’s test, respectively. A Kruskal-Wallis test was performed separately for each week to detect significant differences among substrates. Post-hoc comparisons were conducted using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction to identify specific pairs of substrates with significant differences (with p < 0.05 considered significant).

3. Results

3.1. Sporophyte Length

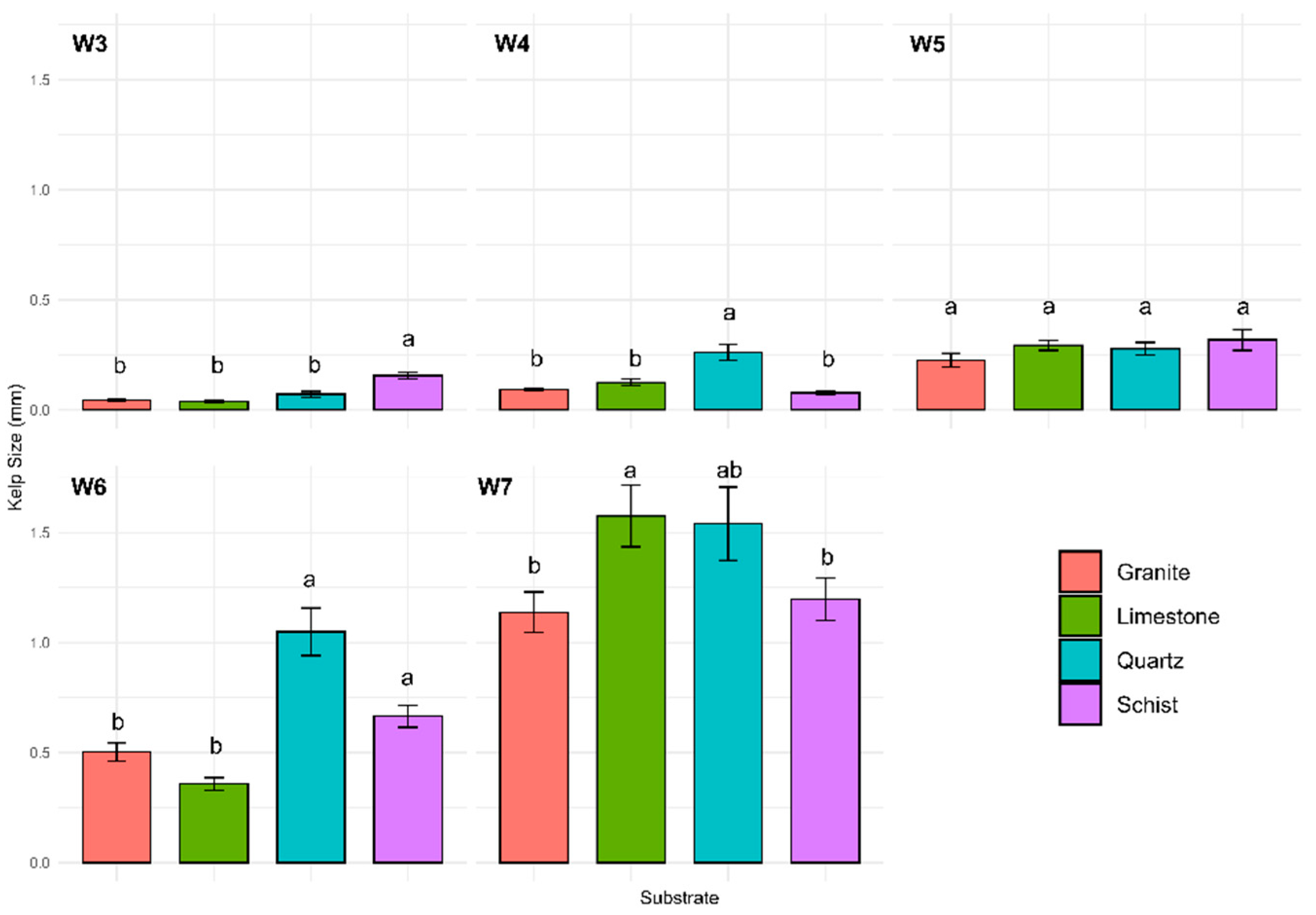

The trial started in mid-April and lasted a total of 8 weeks. The first kelp recruitment was observed in the 3rd week. The analysis revealed that time and substrate type are statistically significant factors influencing kelp size (p < 0.001) (

Figure 1). In week 3, the schist exhibited significantly higher kelp length (0.16 ± 0.01 mm) compared to the other substrates (p < 0.0001), while no significant differences were observed among the other three substrates during this period (mean values ranging from 0.04 to 0.07). In week 4, quartz demonstrated significantly higher kelp length (0.26 ± 0.04 mm) compared to granite (0.09 ± 0.01 mm), limestone (0.12 mm), and schist (0.08 ± 0.01 mm), while no significant differences were observed among the other three substrates (p < 0.0001). By week 5, no significant differences were observed among the substrates. In week 6, quartz and schist exhibited the highest kelp length (1.25 ± 0.16 and 0.67 ± 0.05 mm, respectively), with no significant differences between the two substrates, indicating comparable performance under the experimental conditions. Both performed significantly better than granite (0.50 ± 0.04 mm; p < 0.0004) and limestone (0.31 ± 0.02 mm; p < 0.0001), which had the lowest growth during this week. Finally, in week 7, limestone (1.58 ± 0.14 mm) outperformed schist (1.2 ± 0.1 mm; p = 0.0245) and granite (1.14 ± 0.09 mm; p = 0.0394) while showing no significant differences compared to quartz (1.54 ± 0.17 mm). Quartz, schist, and granite exhibited similar growth performance during this period.

3.2. Sporophyte Density

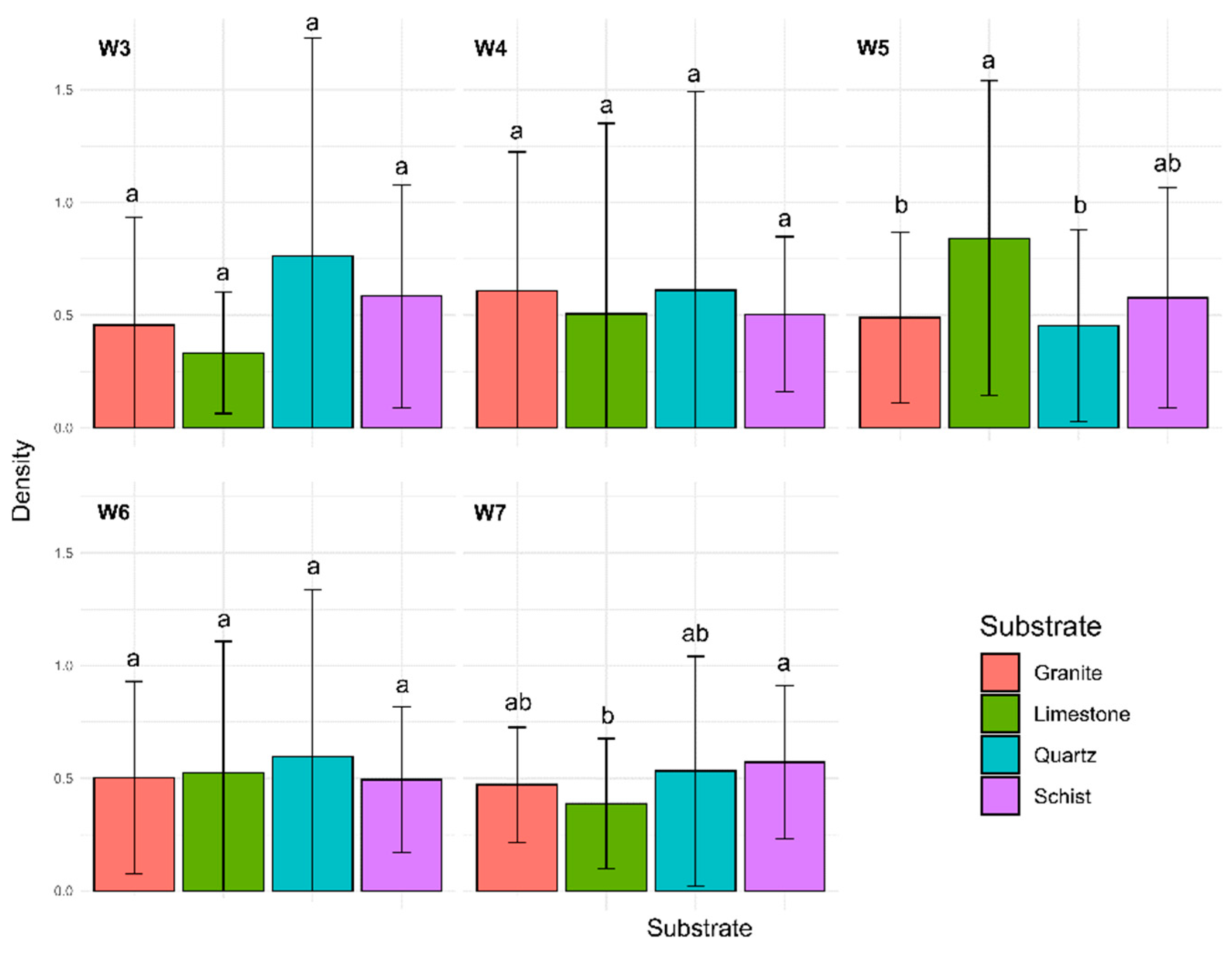

The analysis showed that the interaction between time and substrate type is a statistically significant factor influencing kelp density (

p < 0.001;

Figure 2). In weeks 3, 4, and 6, no significant difference was observed between the substrates. In week 5, significant differences were observed between granite and limestone (0.49 ± 0.38 individuals cm

-2 vs 0.84 ± 0.69 individuals cm

-2,

p = 0.0119) and between limestone and quartz (0.84 ± 0.69 individuals cm

-2 vs 0.45 ± 0.42 individuals cm

-2,

p = 0.0002). However, no significant differences were detected between the remaining substrates. The results indicate that limestone stood out as a substrate with significantly higher densities compared to granite and quartz during this experiment stage. By week 7, however, the only significant difference observed occurred between limestone and schist (0.39 ± 0.29 individuals cm

-2 vs 0.57 ± 0.34 individuals cm

-2,

p = 0.0006), with schist supporting higher densities compared to limestone during the later stage of the experiment.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to optimize the green gravel method, focusing on the kelp species L. ochroleuca, by investigating how different substrata (granite, limestone, quartz, and schist) affect recruitment success, particularly in terms of timing, recruit size, and adherence to the substrate.

In terms of recruit density, the overall assessment indicated that substrate type did not have an outstanding effect, suggesting that all tested materials can support L. ochroleuca recruitment. However, looking at kelp length, our results demonstrated that the type of substrate plays a significant role in early kelp growth. Among the tested substrates, quartz exhibited the overall highest sporophyte size. Schist initially supported significantly larger sporophytes but did not maintain this advantage over time. By week 6, both quartz and schist emerged as the most favourable substrates for recruitment, outperforming granite and limestone. However, by week 7, limestone demonstrated comparable efficiency, suggesting that multiple substrate types may be suitable for the green gravel technique.

Our findings align with previous research demonstrating that substrate characteristics, such as roughness and colour, play a crucial role in macroalgal recruitment and survival [

34]. Past studies on other kelp species have highlighted the importance of surface roughness in enhancing early-stage attachment and survival [

35]. Roughened surfaces are believed to strengthen juvenile attachment by increasing the available area for holdfast anchorage and allowing rhizoids to interlock within microscopic crevices, thereby improving stability [

36,

37]. Previous research also suggested that colour, through its influence on light absorption and temperature, may affect algal settlement and growth. Darker substrates have been associated with higher settlement rates, potentially due to localized temperature increases that enhance zoospore adhesion [

38,

39]. While no single substrate had the highest values for both recruit length and density, quartz exhibited the most consistent overall performance. This may be attributed to a combination of factors, such as surface texture, mineral composition, and chemical properties, which together could create more favourable conditions for attachment and early development. These findings emphasize the complex interactions between substrate properties and macroalgal recruitment, highlighting the need for further research to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

From both practical and economic perspectives, substrate selection is crucial for optimizing large-scale kelp restoration. The green gravel method is increasingly recognized as a cost-effective and scalable technique, reducing reliance on labour- and resource-intensive transplantation methods. Since quartz and schist showed promising results by week 6, their use could enable earlier deployment, thereby significantly reducing the duration and cost of laboratory cultivation. This supports the broader goal of making kelp restoration more economically viable and accessible for conservation initiatives.

Although quartz appears to be a durable and effective option, the friability of schist raises concerns regarding its suitability and performance in high-energy environments. However, this limitation is counterbalanced by its flatness, which may reduce movement and damage to recruits. Moreover, results from week 7 indicate that limestone may be an equally viable alternative. Both quartz and limestone are generally more readily available in hardware stores, although quartz tends to be more expensive. Given the nuanced differences in suitability among quartz, limestone, and schist, the final substrate selection will likely depend on multiple factors, including site-specific hydrodynamic conditions, material availability, and overall cost. Despite granite being the most commonly used substrate in reforestation efforts [

24], our findings do not support its use. These findings may encourage future studies to explore alternative materials that enhance the efficiency and success of green gravel technique. Ultimately, long-term monitoring following outplanting will be essential for refining substrate selection and improving restoration outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and T.R.P.; methodology, T.F.P., S.C., and T.R.P.; validation, S.C., T.R.P. and I.S.-P.; formal analysis, T.F.P.; investigation, S.C. and T.R.P.; resources, I.S.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, T.F.P.; writing—review and editing, S.C and T.R.P.; supervision, I.S.-P.; project administration, I.S.-P.; funding acquisition, I.S.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “Seaforests for blue carbon—natural capital from nature-based solutions” funded by EEA Grants (PT-INNOVATION-0081).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable. No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thibaut, T.; Pinedo, S.; Torras, X.; Ballesteros, E. Long-term decline of the populations of Fucales (Cystoseira spp. and Sargassum spp.) in the Albères coast (France, North-western Mediterranean). Marine pollution bulletin 2005, 50, 1472–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, D. Management of kelp ecosystem in Japan. Cahiers de Biologie Marine 2011, 52, 499–505. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers-Bennett, L.; Catton, C. Marine heat wave and multiple stressors tip bull kelp forest to sea urchin barrens. Scientific Reports 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, A.; Marzinelli, E.; Vergés, A.; Coleman, M.; Steinberg, P. Towards Restoration of Missing Underwater Forests. PloS one 2014, 9, e84106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.; Assis, J.; Aguillar, R.; Airoldi, L.; Bárbara, I.; Bartsch, I.; Bekkby, T.; Christie, H.; Davoult, D.; Derrien-Courtel, S.; et al. Status, trends and drivers of kelp forests in Europe: an expert assessment. Biodiversity and Conservation 2016, 25, 1319–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumhansl, K.A.; Okamoto, D.; Rassweiler, A.; Novak, M.; Bolton, J.; Cavanaugh, K.; Connell, S.; Johnson, C.R.; Konar, B.; Ling, S.; et al. Global patterns of kelp forest change over the past half-century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 13785–13790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbee-Dexter, K.; Wernberg, T. Rise of Turfs: A New Battlefront for Globally Declining Kelp Forests. BioScience 2018, 68, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, B.; Radford, B.; Thomsen, M.; Connell, S.; Carreño, F.; Bradshaw, C.; Fordham, D.; Russell, B.; Gurgel, C.; Wernberg, T. Distribution models predict large contractions of habitat-forming seaweeds in response to ocean warming. Diversity and Distributions 2018, 24, 1350–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, H.; Norderhaug, K.; Fredriksen, S. Macrophytes as habitat for fauna. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2009, 396, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teagle, H.; Hawkins, S.J.; Moore, P.; Smale, D. The role of kelp species as biogenic habitat formers in coastal marine ecosystems. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 2017, 492, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbee-Dexter, K.; Wernberg, T.; Barreiro, R.; Coleman, M.A.; Bettignies, T.d.; Feehan, C.J.; Franco, J.N.; Hasler, B.; Louro, I.; Norderhaug, K.M.; et al. Leveraging the blue economy to transform marine forest restoration. Journal of Phycology 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, S.; Wernberg, T.; Connell, S.; Hobday, A.J.; Johnson, C.R.; Poloczanska, E.S. The ‘Great Southern Reef’: social, ecological and economic value of Australia’s neglected kelp forests. Marine and Freshwater Research 2016, 67, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Lawton, J.; Shachak, M. Organisms as ecosystem engineers. Oikos 1994, 69, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M. Effects of Local Deforestation on the Diversity and Structure of Southern California Giant Kelp Forest Food Webs. Ecosystems 2003, 7, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocci, I.; Araújo, R.; Oliveira, P.J.; Sousa-Pinto, I. Review: Potential effects of kelp species on local fisheries. Journal of Applied Ecology 2015, 52, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løvås, S.M.; Tørum, A. Effect of the kelp Laminaria hyperborea upon sand dune erosion and water particle velocities. Coastal Engineering 2001, 44, 37–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mork, M. The effect of kelp in wave damping. Sarsia 1996, 80, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.; Wernberg, T.; Altieri, A.; Tuya, F.; Gulbransen, D.; McGlathery, K.; Holmer, M.; Silliman, B. Habitat cascades: the conceptual context and global relevance of facilitation cascades via habitat formation and modification. Integrative and comparative biology 2010, 50 2, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feehan, C.J.; Filbee-Dexter, K.; Wernberg, T. Embrace kelp forests in the coming decade. Science 2021, 373, 863–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiel, D.R.; Foster, M.S. The Population Biology of Large Brown Seaweeds: Ecological Consequences of Multiphase Life Histories in Dynamic Coastal. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2006, 37, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, A.M.; Layton, C.; McHugh, T.A.; Gleason, M.; Eddy, N. Kelp Restoration Guidebook: Lessons Learned From Kelp Projects Around the World; The Nature Conservancy: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, D.C. The Effects of Variable Settlement and Early Competition on Patterns of Kelp Recruitment. Ecology 1990, 71, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrow, M.R.; Davy, A.J. Handbook of Ecological Restoration; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen, S.; Filbe… Dexter, K.; Norderhaug, K.M.; Steen, H.; Bodvin, T.; Coleman, M.A.; Moy, F.E.; Wernberg, T. Green gravel: a novel restoration tool to combat kelp forest decline. Scientific Reports 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Sanchéz-Gallego, Á.; Correia, R.; Sousa Pinto, I.; Chemello, S.; Louro, I.; Lemos, M.; Franco, J. Assessing Atlantic Kelp Forest Restoration Efforts in Southern Europe. Sustainability 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enevoldsen, K. Green gravel—a novel kelp forest restoration method tested on an artificial boulder reef in Danish waters. Master’s thesis, Aarhus University, 2022.

- Alsuwaiyan, N.; Filbee-Dexter, K.; Vranken, S.; Burkholz, C.; Cambridge, M.; Coleman, M.; Wernberg, T. Green gravel as a vector of dispersal for kelp restoration. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 910417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemello, S.; Pinto, I.S.; Pereira, T.R. Optimising Kelp Cultivation to Scale up Habitat Restoration Efforts: Effect of Light Intensity on “Green Gravel” Production. Hydrobiology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemello, S.; Santos, I.; Sousa Pinto, I.; Pereira, T. Unlocking the Potential of Green Gravel Production for Efficient Kelp Restoration: How Seeding Density Affects the Development of the Golden Kelp Laminaria ochroleuca. Phycology 2024, 4, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkett, D.; Maggs, C.; Dring, M.; Boaden, P. An Overview of Dynamic and Sensitivity Characteristics for Conservation Management of Marine SACs. Scott. Assoc. Mar. Sci. (SAMS) 1998, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenrock, K.; O’Callaghan, T.; O’Callaghan, R.; Krueger-Hadfield, S. First record of Laminaria ochroleuca Bachelot de la Pylaie in Ireland in Béal an Mhuirthead, county Mayo. Marine Biodiversity Records 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, D.; Wernberg, T.; Yunnie, A.L.E.; Vance, T. The rise of Laminaria ochroleuca in the Western English Channel (UK) and comparisons with its competitor and assemblage dominant Laminaria hyperborea. Marine Ecology 2015, 36, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuya, F.; Cacabelos, E.; Duarte, P.; Jacinto, D.; Castro, J.J.; Silva, T.; Bertocci, I.; Franco, J.N.; Arenas, F.; Coca, J.; et al. Patterns of landscape and assemblage structure along a latitudinal gradient in ocean climate. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2012, 466, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrison, P.; Stanley, M.; Kelly, M.; MacLeod, A.; Black, K.; Hughes, A. Optimising the settlement and hatchery culture of Saccharina latissima (Phaeophyta) by manipulation of growth medium and substrate surface condition. Journal of Applied Phycology 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, A.F. Effects of Zoospore Aggregation and Substrate Rugosity on Kelp Recruitment Success. Journal of Phycology 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milligan, K.; DeWreede, R.E. Variations in holdfast attachment mechanics with developmental stage, substratum-type, season, and wave-exposure for the intertidal kelp species Hedophyllum sessile (C. Agardh) Setchell. Journal of experimental marine biology and ecology 2000, 254, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, L.; Feely, M.; Stengel, D.; Blamey, N.; Dockery, P.; Sherlock, A.; Timmins, E. Seaweed attachment to bedrock: Biophysical evidence for a new geophycology paradigm. Geobiology 2009, 7, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlem, C.; Moran, P.J.; Grant, T. Larval settlement of marine sessile invertebrates on surfaces of different colour and position. 1984.

- Swain, G.W.; Herpe, S.; Ralston, E.; Tribou, M. Short-term testing of antifouling surfaces: the importance of colour. Biofouling 2006, 22, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).