Submitted:

21 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Epizootic Events and Mosquito Collection

2.3. YFV RNA Detection and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vasconcelos PFC, Monath TP. Yellow Fever Remains a Potential Threat to Public Health. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2016; 16: 566–567. [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo Fernandes NCC, Guerra JM, Díaz-Delgado J, et al. Differential Yellow Fever Susceptibility in New World Nonhuman Primates, Comparison with Humans, and Implications for Surveillance. Emerg Infect Dis 2021; 27: 47–56. [CrossRef]

- Monath TP, Vasconcelos PFC. Yellow fever. Journal of Clinical Virology 2015; 64: 160–173. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos PFC, Costa ZG, Travassos Da Rosa ES, et al. Epidemic of jungle yellow fever in Brazil, 2000: Implications of climatic alterations in disease spread. J Med Virol 2001; 65: 598–604. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio da Saúde. Brasília-DF 2017 GUIA DE VIGILÂNCIA DE EPIZOOTIAS EM PRIMATAS NÃO HUMANOS E ENTOMOLOGIA APLICADA À VIGILÂNCIA DA FEBRE AMARELA MINISTÉRIO DA SAÚDE 2 a edição atualizada. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br (2017).

- Li SL, Acosta AL, Hill SC, et al. Mapping environmental suitability of Haemagogus and Sabethes spp. mosquitoes to understand sylvatic transmission risk of yellow fever virus in Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022; 16: e0010019. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Inacio CL, Ximenes M de FF de M. Haemagogus spegazzinii Brèthes, 1912 (Diptera: Culicidae) in Brazilian semiarid: resistance in eggs and scale color variation in adults. Rev Bras Entomol; 65. Epub ahead of print 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cunha MS, da Costa AC, de Azevedo Fernandes NCC, et al. Epizootics due to Yellow Fever Virus in São Paulo State, Brazil: viral dissemination to new areas (2016–2017). Sci Rep 2019; 9: 5474. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes NCC de A, Cunha MS, Guerra JM, et al. Outbreak of Yellow Fever among Nonhuman Primates, Espirito Santo, Brazil, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23: 2038–2041. [CrossRef]

- Mello M De, Rezende D, Adelino R, et al. Persistence of Yellow fever virus outside the Amazon Basin , causing epidemics in Southeast Brazil , from 2016 to 2018. 2018; 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Soto A, Torres MC, Lima de Mendonça MC, et al. Evidence for multiple sylvatic transmission cycles during the 2016–2017 yellow fever virus outbreak, Brazil. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2018; 24: 1019.e1-1019.e4. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Sao Paulo, https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/sp/sao-paulo.html (2022, accessed 5 March 2025).

- Faria NR, Kraemer MUG, Hill SC, et al. Genomic and epidemiological monitoring of yellow fever virus transmission potential. Science (1979) 2018; 361: 894–899. [CrossRef]

- Hill SC, de Souza R, Thézé J, et al. Genomic Surveillance of Yellow Fever Virus Epizootic in São Paulo, Brazil, 2016 – 2018. PLoS Pathog 2020; 16: e1008699. [CrossRef]

- Cunha MS, Tubaki RM, de Menezes RMT, et al. Possible non-sylvatic transmission of yellow fever between non-human primates in São Paulo city, Brazil, 2017–2018. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 15751. [CrossRef]

- Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis.

- Figueiredo PDO, Gabriella A, Costa GB, et al. Re-Emergence of Yellow Fever in Brazil during 2016–2019: Challenges, Lessons Learned, and Perspectives. [CrossRef]

- Abreu FVS de, Ribeiro IP, Ferreira-de-Brito A, et al. Haemagogus leucocelaenus and Haemagogus janthinomys are the primary vectors in the major yellow fever outbreak in Brazil, 2016–2018. Emerg Microbes Infect 2019; 8: 218–231. [CrossRef]

- Souza RP de, Petrella S, Coimbra TLM, et al. Isolation of yellow fever virus (YFV) from naturally infectied Haemagogus (Conopostegus) leucocelaenus (diptera, cukicudae) in São Paulo State, Brazil, 2009. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2011; 53: 133–139. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos PFC, Sperb AF, Monteiro HAO, et al. Isolations of yellow fever virus from Haemagogus leucocelaenus in Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2003; 97: 60–62. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho GC, dos Santos Malafronte R, Miti Izumisawa C, et al. Blood meal sources of mosquitoes captured in municipal parks in São Paulo, Brazil. Journal of Vector Ecology 2014; 39: 146–152. [CrossRef]

- Forattini OP, Gomes A de C, Natal D, et al. Preferências alimentares e domiciliação de mosquitos Culicidae no Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo, Brasil, com especial referência a Aedes scapularis e a Culex (Melanoconion). Rev Saude Publica 1989; 23: 9–19. [CrossRef]

- Abreu FVS de, Ribeiro IP, Ferreira-de-Brito A, et al. Haemagogus leucocelaenus and Haemagogus janthinomys are the primary vectors in the major yellow fever outbreak in Brazil, 2016–2018. Emerg Microbes Infect 2019; 8: 218–231. [CrossRef]

- Goenaga S, Fabbri C, Dueñas JCR, et al. Isolation of Yellow Fever Virus from Mosquitoes in Misiones Province, Argentina. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2012; 12: 986–993. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira CH, Andrade MS, Campos FS, et al. Yellow Fever Virus Maintained by Sabethes Mosquitoes during the Dry Season in Cerrado, a Semiarid Region of Brazil, in 2021. Viruses 2023; 15: 757. [CrossRef]

- Stanzani LM de A, Motta M de A, Erbisti RS, et al. Back to Where It Was First Described: Vectors of Sylvatic Yellow Fever Transmission in the 2017 Outbreak in Espírito Santo, Brazil. Viruses 2022; 14: 2805. [CrossRef]

- Couto-lima D, Madec Y, Bersot MI, et al. Potential risk of re-emergence of urban transmission of Yellow Fever virus in Brazil facilitated by competent Aedes populations. 2017; 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes NCC de A, Cunha MS, Suarez PEN, et al. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a new introduction of Yellow Fever virus in São Paulo State, Brazil, 2023. Acta Trop 2024; 251: 107110.

- Lourenço-de-Oliveira R, Vazeille M, Filippis AMB de, et al. Oral Susceptibility to Yellow Fever Virus of Aedes aegypti from Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2002; 97: 437–439. [CrossRef]

- Laurindo Barbosa G, Sterlino Bergo E, Pereira M, et al. Presença de Aedes aegypti e Aedes albopictus em ambientes urbanos adjacentes às áreas silvestres que apresentam potencial para a circulação do vírus da febre amarela no estado de São Paulo. BEPA Boletim Epidemiológico Paulista 2022; 16: 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Damasceno-Caldeira R, Nunes-Neto JP, Aragão CF, et al. Vector Competence of Aedes albopictus for Yellow Fever Virus: Risk of Reemergence of Urban Yellow Fever in Brazil. Viruses 2023; 15: 1019. [CrossRef]

- Amraoui F, Pain A, Piorkowski G, et al. Experimental Adaptation of the Yellow Fever Virus to the Mosquito Aedes albopictus and Potential risk of urban epidemics in Brazil, South America. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 14337. [CrossRef]

- Hamlet A, Jean K, Perea W, et al. The seasonal influence of climate and environment on yellow fever transmission across Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12: e0006284. [CrossRef]

- Sacchetto L, Silva NIO, Rezende IM de, et al. Neighbor danger: Yellow fever virus epizootics in urban and urban-rural transition areas of Minas Gerais state, during 2017-2018 yellow fever outbreaks in Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020; 14: e0008658. [CrossRef]

| Species | N | % | Positive | %_Pos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aedes scapularis | 893 | 26.46 | 6 | 0.67 |

| Aedes albopictus | 731 | 21.66 | 3 | 0.41 |

| Psorophora ferox | 378 | 11.20 | 5 | 1.32 |

| Haemagogus leucocelaenus | 274 | 8.09 | 16 | 5.83 |

| Aedes serratus | 193 | 5.72 | 4 | 2.07 |

| Aedes aegypti | 148 | 4.39 | 0 | 0 |

| Haemagogus janthinomys/capricornii | 127 | 3.4 | 7 | 5.51 |

| Sabethes purpureus | 96 | 2.84 | 2 | 2.08 |

| Sabethes glaucodaemon | 94 | 2.79 | 0 | 0 |

| Aedes terrens | 72 | 2.13 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes identicus | 57 | 1.69 | 1 | 1.75 |

| Sabethes albiprivus | 47 | 1.39 | 2 | 4.26 |

| Sabethes imperfectus | 35 | 1.04 | 0 | 0 |

| Psorophora albigenu | 31 | 0.83 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes intermedius | 28 | 0.83 | 0 | 0 |

| Psorophora albipes | 27 | 0.80 | 0 | 0 |

| Psorophora (Jan.) sp | 17 | 0.50 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes belisarioi | 16 | 0.47 | 0 | 0 |

| Aedes argyrothorax | 13 | 0.39 | 0 | 0 |

| Psorophora sp | 11 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes chloropterus | 11 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes sp | 11 | 0.30 | 0 | 0 |

| Aedes sp | 9 | 0.27 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes undosus | 9 | 0.27 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes tridentatus | 8 | 0.24 | 0 | 0 |

| Psorophora lutzii | 6 | 0.18 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes soperi | 6 | 0.18 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes whitmani | 6 | 0.18 | 0 | 0 |

| Howardina fulvithorax | 6 | 0.18 | 0 | 0 |

| Culex sp. | 4 | 0.12 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes undosus aff. | 3 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 |

| Aedes fluviatilis | 2 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 |

| Culex quinquefaciatus | 2 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 |

| Limatus sp. | 1 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 |

| Psorophora lanei | 1 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes belisarioi aff. | 1 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes petrochiae | 1 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 |

| Sabethes shannoni | 1 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 |

| Pool number |

Species | Local | CT_value | Date | Season |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 443 | Aedes scapularis | Urupes | 25 | 26/11/2016 | Rainy |

| 465 | Psorophora ferox | Pontalinda | 38 | 21/08/2018 | Dry |

| 732 | Aedes albopictus | Jundiaí | 38 | 28/08/2018 | Dry |

| 1415 | Aedes scapularis | Araçatuba | 28 | 25/11/2016 | Rainy |

| 2152 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Caieras | 23 | 16/04/2019 | Dry |

| 2163 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Guarulhos | 21 | 14/12/2018 | Rainy |

| 2198 | Aedes serratus | Jarinu | 33 | 12/02/2019 | Rainy |

| 2322 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Jarinu | 37 | 03/05/2018 | Dry |

| 2348 | Aedes scapularis | Sao Paulo | 37 | 19/02/2018 | Rainy |

| 2377 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Jarinu | 20 | 30/01/2018 | Rainy |

| 2438 | Haemagogus janthinomys-capricornii | Mairipora | 33 | 23/01/2018 | Rainy |

| 2572 | Haemagogus janthinomys-capricornii | Valinhos | 31 | 04/09/2018 | Dry |

| 2577 | Haemagogus janthinomys-capricornii | Valinhos | 34 | 17/09/2018 | Dry |

| 3268 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Sao Paulo | 19 | 20/12/2017 | Rainy |

| 3269 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Sao Paulo | 18 | 20/12/2017 | Rainy |

| 3318 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Sao José dos Campos | 28 | 10/10/2018 | Dry |

| 3491 | Sabethes purpureus | Sao Miguel Arcanjo | 37 | 04/09/2018 | Dry |

| 3514 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Piedade | 31 | 10/10/2018 | Dry |

| 3521 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Jacarei | 20 | 04/09/2018 | Dry |

| 3530 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Jacarei | 18 | 28/05/2018 | Dry |

| 3541 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Igarata | 19 | 28/05/2018 | Dry |

| 3542 | Sabethes albiprivus | Igarata | 38 | 28/05/2018 | Dry |

| 3543 | Sabethes identicus | Igarata | 38 | 28/05/2018 | Dry |

| 3551 | Haemagogus janthinomys-capricornii | Igarata | 16 | 23/05/2018 | Dry |

| 3552 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Igarata | 20 | 23/05/2018 | Dry |

| 3687 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Sao José dos Campos | 23 | 04/07/2018 | Dry |

| 3689 | Haemagogus janthinomys-capricornii | Sao José dos Campos | 25 | 04/07/2018 | Dry |

| 3766 | Haemagogus janthinomys-capricornii | Caçapava | 22 | 25/06/2018 | Dry |

| 3769 | Sabethes albiprivus | Caçapava | 34 | 25/06/2018 | Dry |

| 3777 | Aedes albopictus | Itariri | 38 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4188 | Psorophora ferox | Jacupiranga | 31 | 10/12/2018 | Rainy |

| 4231 | Aedes albopictus | Pereira Barreto | 37 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4232 | Aedes scapularis | Pereira Barreto | 37 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4233 | Aedes serratus | Pereira Barreto | 38 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4234 | Aedes scapularis | Pereira Barreto | 38 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4238 | Aedes scapularis | Sao Paulo | 38 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4272 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Monteiro Lobato | 17 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4273 | Psorophora ferox | Monteiro Lobato | 37 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4275 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Monteiro Lobato | 17 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4276 | Aedes serratus | Monteiro Lobato | 35 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4279 | Sabethes purpureus | Monteiro Lobato | 38 | 16/01/2019 | Rainy |

| 4297 | Haemagogus leucocelaenus | Monteiro Lobato | 21 | 25/03/2019 | Rainy |

| 4298 | Haemagogus janthinomys-capricornii | Monteiro Lobato | 26 | 25/03/2019 | Rainy |

| 4449 | Aedes serratus | Iguape | 38 | 25/03/2019 | Rainy |

| 4568 | Psorophora ferox | Sarapui | 38 | 21/05/2018 | Dry |

| 5077 | Psorophora ferox | Iporanga | 35 | 25/04/2019 | Dry |

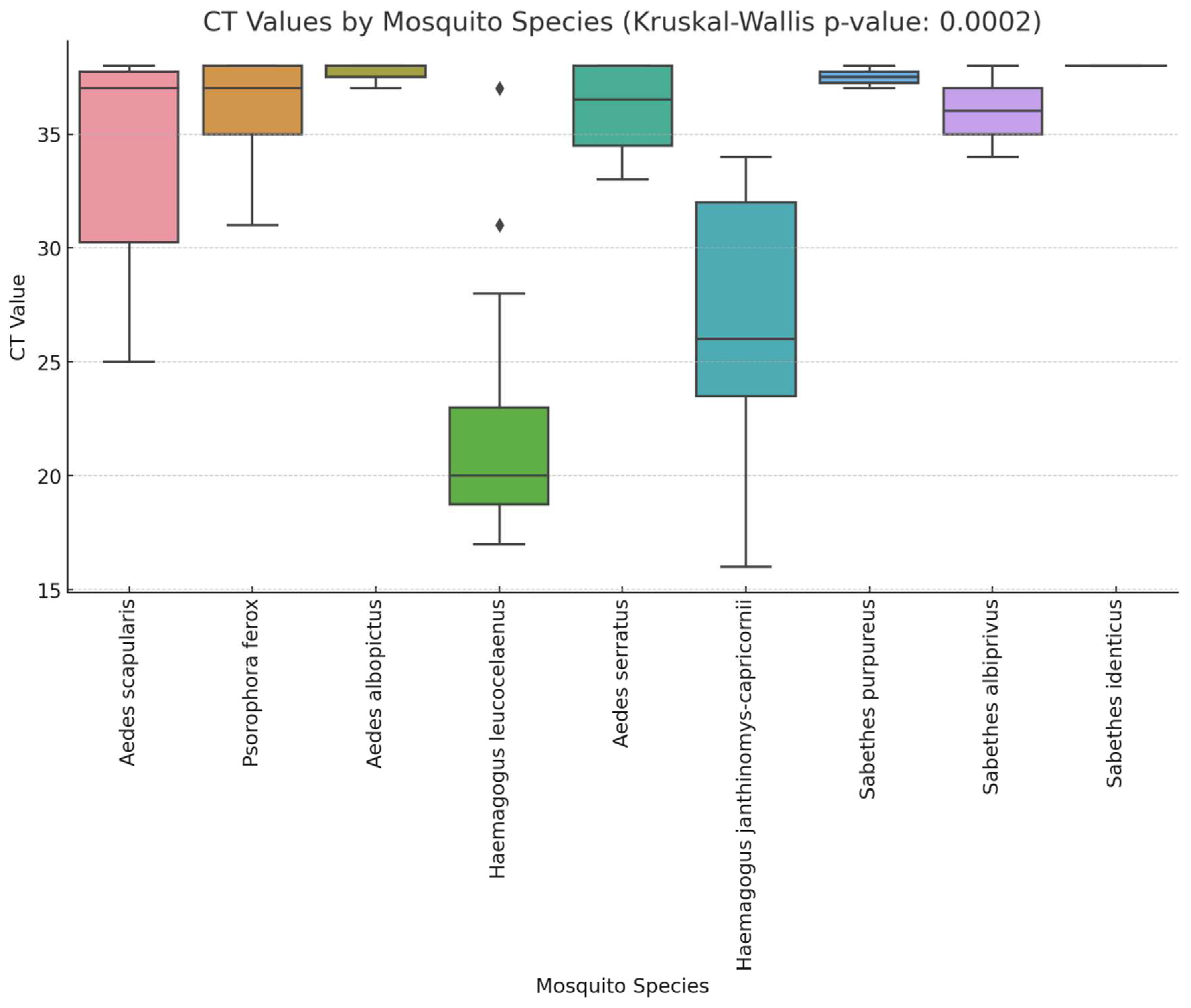

| Species | Estimate (β) | SE | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (Hg. leucocelaenus) | 22 | 1.26 | (19.53, 24.47) | <0.001 |

| Aedes scapularis | 11.83 | 2.41 | (7.11, 16.56) | <0.001 |

| Psorophora ferox | 13.8 | 2.58 | (8.74, 18.86) | <0.001 |

| Aedes albopictus | 15.67 | 3.17 | (9.46, 21.88) | <0.001 |

| Aedes serratus | 14 | 2.81 | (8.48, 19.52) | <0.001 |

| Haemagogusjanthinomys/capricornii | 4.71 | 2.28 | (0.24, 9.19) | 0.039 |

| Sabethes purpureus | 15.5 | 3.78 | (8.10, 22.90) | <0.001 |

| Sabethes albiprivus | 14 | 3.78 | (6.60, 21.40) | <0.001 |

| Sabethes identicus | 16 | 5.19 | (5.83, 26.17) | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).